Submitted:

04 July 2023

Posted:

17 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesises of SiO2 Nanoparticles

- (i)

- Sol-gel Process

- (ii)

- Stober Process

2.3. Sulfonation Process

2.4. Fabrication of Composite Membranes (Casting Method)

3. Characterization Techniques

3.1. Water uptake

3.2. Ion Exchange Capacity (IEC)

3.3. Methanol Permeability

3.4. Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) measurements

3.5. X-ray Powder Diffraction Analysis (XRD)

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Fourier Transform Infrared for chitosan membranes

4.2. X-ray Diffraction of chitosan membranes

4.3. SEM of chitosan membranes

4.4. Water uptake of chitosan membranes

- (i)

- Effect of Silica Content on Water Uptake

- (ii)

- Effect of Temperature on Water Uptake

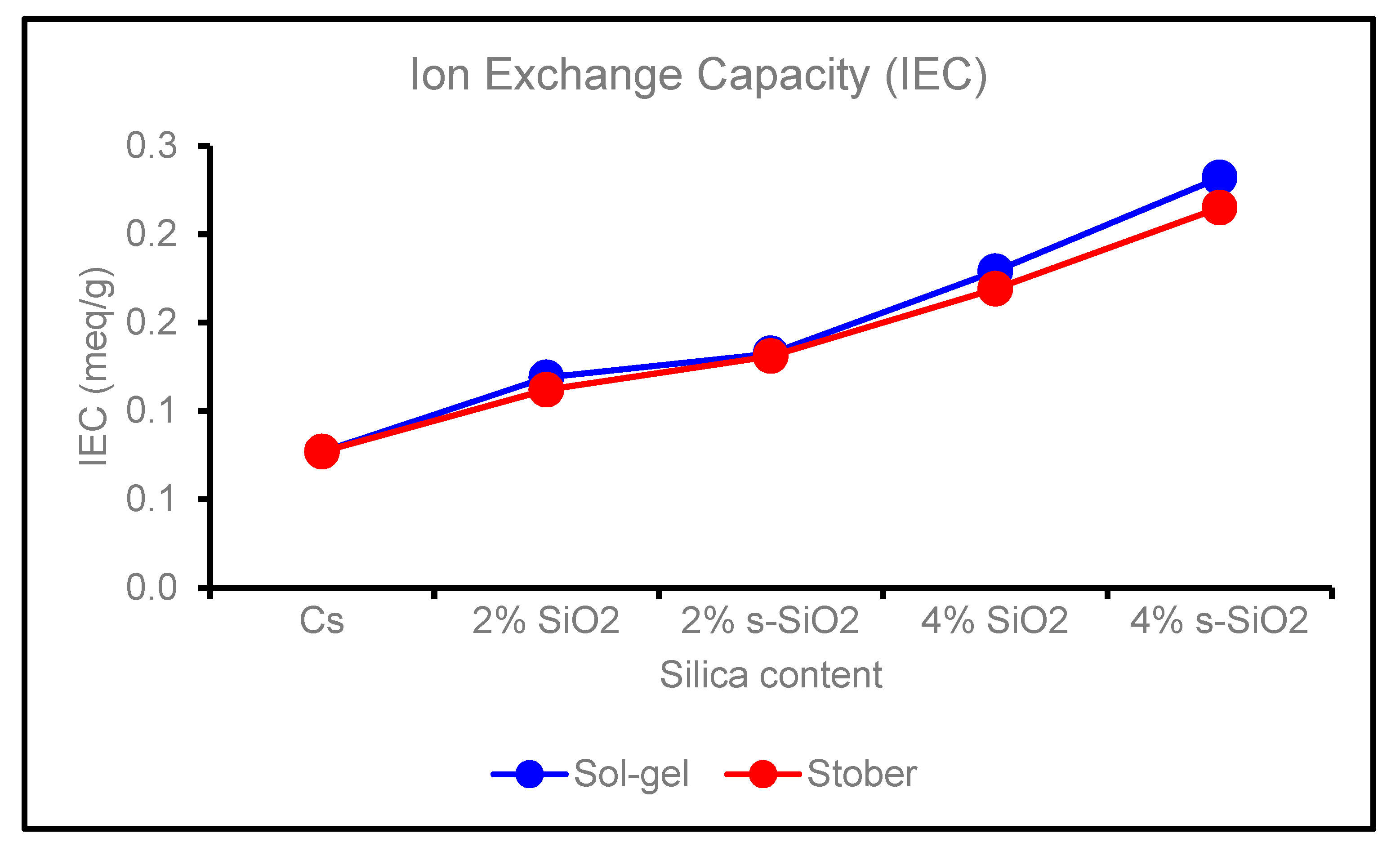

4.5. Ion Exchange Capacity of chitosan membranes

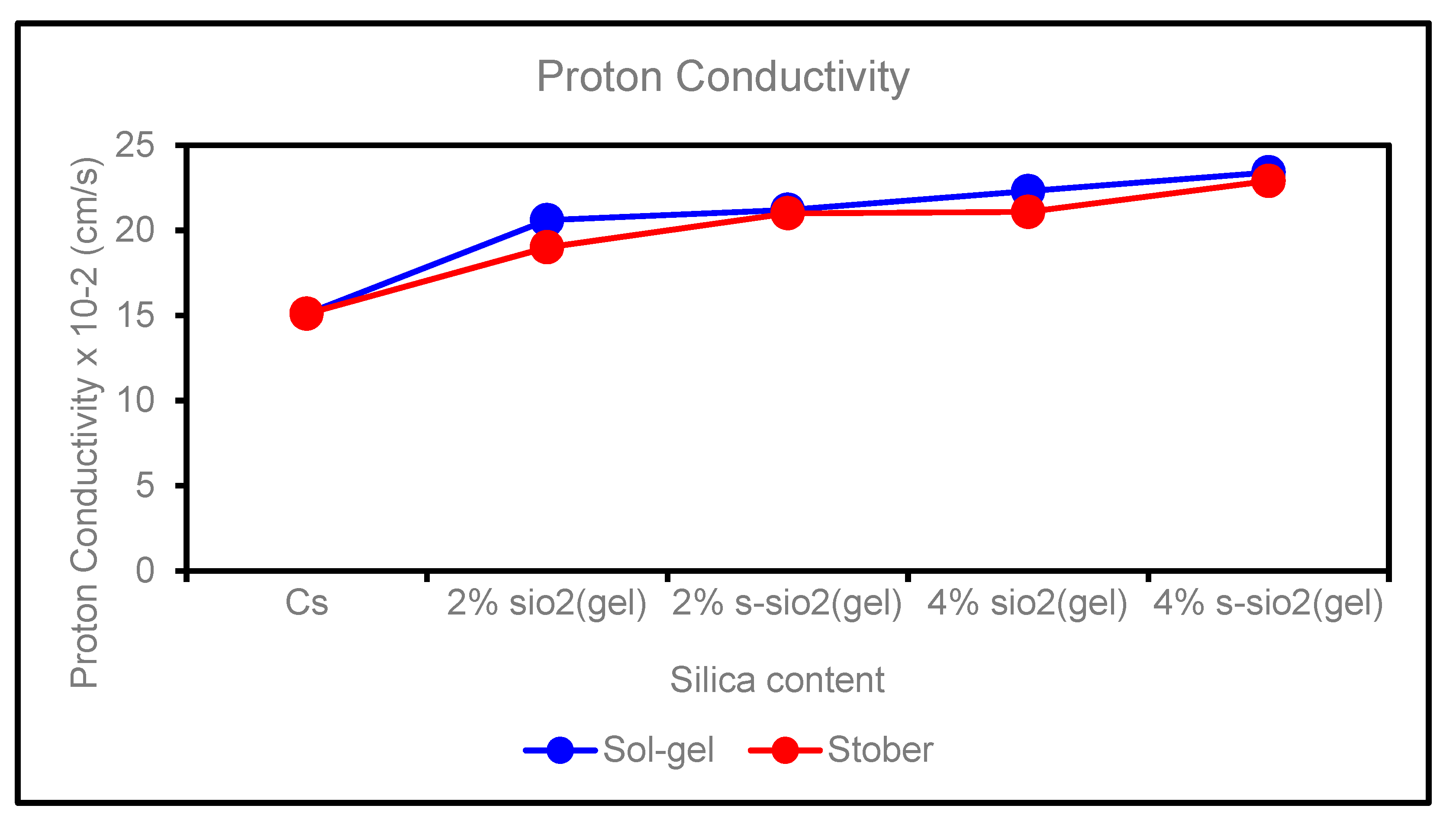

4.6. Proton Conductivity of chitosan membranes

4.7. Methanol Permeability of chitosan membranes

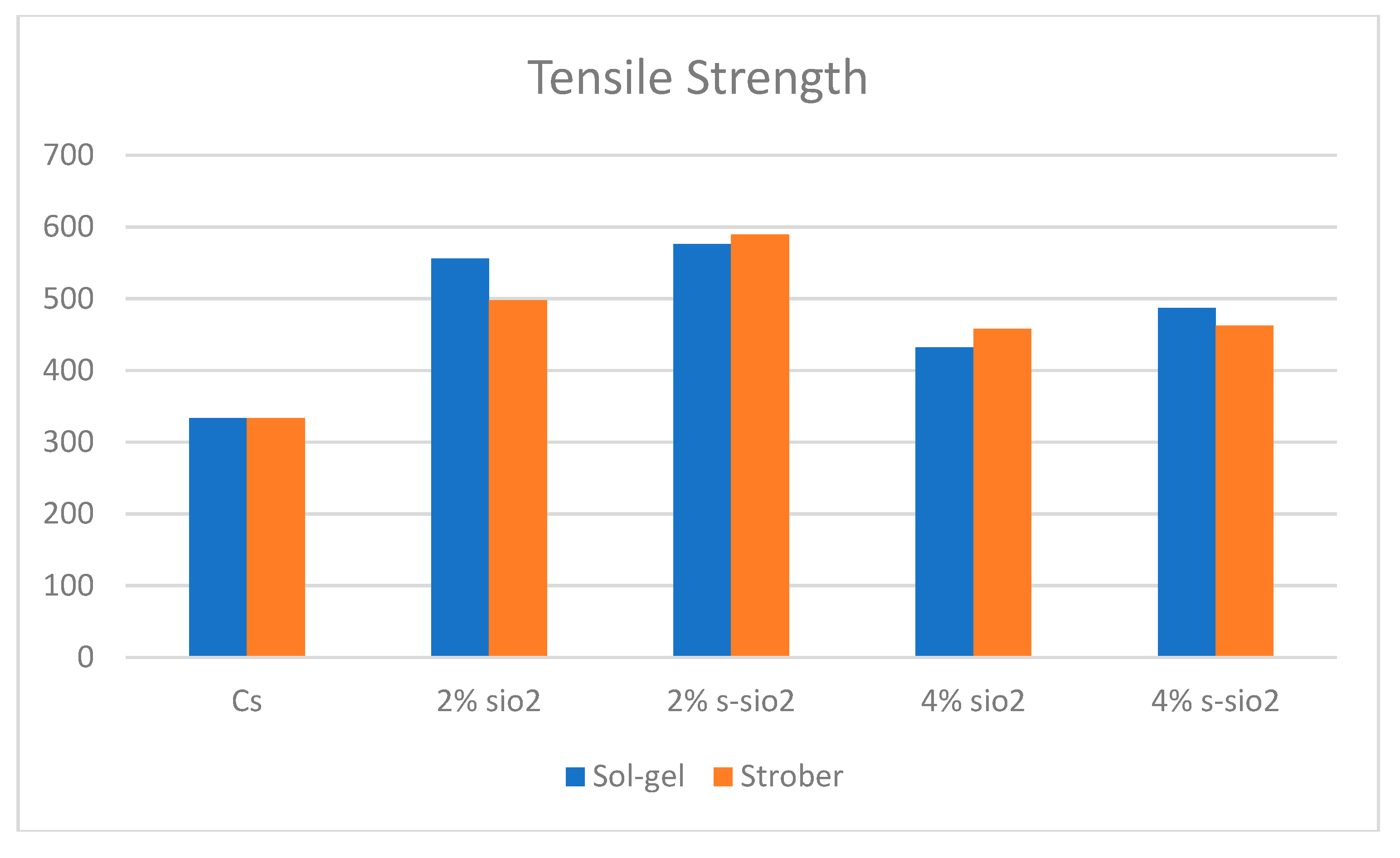

4.8. Tensile strength of chitosan membranes

5. Conclusion

References

- Bayrak ZU, Gencoglu MT. Application areas of fuel cells. In: Proceedings of 2013 International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications, ICRERA 2013. IEEE Computer Society; 2013:452-457. [CrossRef]

- Kasyanova A V., Zvonareva IA, Tarasova NA, Bi L, Medvedev DA, Shao Z. Electrolyte materials for protonic ceramic electrochemical cells: Main limitations and potential solutions. Mater Reports Energy. 2022;2(4):100158. [CrossRef]

- Halim FA, Hasran UA, Masdar MS, Kamarudin SK, Daud WRW. Overview on Vapor Feed Direct Methanol Fuel Cell. APCBEE Procedia. 2012;3:40-45. [CrossRef]

- Vaghari H, Jafarizadeh-Malmiri H, Berenjian A, Anarjan N. Recent advances in application of chitosan in fuel cells. Sustain Chem Process. 2013;1(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Qussay R, Mahmood M, Al-Zaidi MK, Al-Khafaji RQ, Al-Zubaidy DK, Salman MM. A Review: Fuel Cells Types and their Applications. Int J Sci Eng Appl Sci. 2021;(7):2395-3470. www.ijseas.com.

- Ebrahimi M, Kujawski W, Fatyeyeva K, Kujawa J. A review on ionic liquids-based membranes for middle and high temperature polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells (Pem fcs). Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(11). [CrossRef]

- Ramadhani F, Hussain MA, Mokhlis H. A comprehensive review and technical guideline for optimal design and operations of fuel cell-based cogeneration systems. Processes. 2019;7(12). [CrossRef]

- Tellez-Cruz MM, Escorihuela J, Solorza-Feria O, Compañ V. Proton exchange membrane fuel cells (Pemfcs): Advances and challenges. Polymers (Basel). 2021;13(18):1-54. [CrossRef]

- Olabi AG, Wilberforce T, Alanazi A, et al. Novel Trends in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Vol 15.; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ohashi M. Direct Methanol Fuel Cell as the next Generation Power Source.

- Baruah B, Deb P. Performance and application of carbon-based electrocatalysts in direct methanol fuel cell. Mater Adv. 2021;2(16):5344-5364. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed AA, Al Labadidi M, Hamada AT, Orhan MF. Design and Utilization of a Direct Methanol Fuel Cell. Membranes (Basel). 2022;12(12). [CrossRef]

- Off-grid Photovoltaic system with Battery Storage and Direct Methanol Fuel Cell as a. 2020;(January):0-10. [CrossRef]

- Chou CJ, Jiang SB, Yeh TL, Tsai LD, Kang KY, Liu CJ. A portable direct methanol fuel cell power station for long-term internet of things applications. Energies. 2020;13(14). [CrossRef]

- Goor M, Menkin S, Peled E. High power direct methanol fuel cell for mobility and portable applications. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2019;44(5):3138-3143. [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin SK, Achmad F, Daud WRW. Overview on the application of direct methanol fuel cell (DMFC) for portable electronic devices. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2009;34(16):6902-6916. [CrossRef]

- Ghouse M. Fuel Cells and Their Applications Prof . M . Ghouse King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology ( KACST ) Riyadh , Saudi Arabia 17 th June 2012. 2016;(June 2012). 20 June. [CrossRef]

- Kartika Sari A, Mohamad Yunus R, Majlan EH, et al. Nata de Cassava Type of Bacterial Cellulose Doped with Phosphoric Acid as a Proton Exchange Membrane. Membranes (Basel). 2023;13(1). [CrossRef]

- Selim A, Szijjártó GP, Tompos A. Insights into the Influence of Different Pre-Treatments on Physicochemical Properties of Nafion XL Membrane and Fuel Cell Performance. Polymers (Basel). 2022;14(16). [CrossRef]

- Sherazi TA, Guiver MD, Kingston D, Ahmad S, Kashmiri MA, Xue X. Radiation-grafted membranes based on polyethylene for direct methanol fuel cells. J Power Sources. 2010;195(1):21-29. [CrossRef]

- Hwang S, Lee HG, Jeong YG, et al. Polymer Electrolyte Membranes Containing Functionalized Organic/Inorganic Composite for Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cell Applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22). [CrossRef]

- Kabir Chowdury MS, Cho YJ, Park SB, Park Y il. Review—Functionalized Graphene Oxide Membranes as Electrolytes. J Electrochem Soc. Published online 2023. [CrossRef]

- Adiyar SR, Satriyatama A, Azjuba AN, Sari NKAK. An overview of synthetic polymer-based membrane modified with chitosan for direct methanol fuel cell application. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2021;1143(1):012002. [CrossRef]

- Fatullayeva S, Tagiyev D, Zeynalov N, Mammadova S, Aliyeva E. Recent advances of chitosan-based polymers in biomedical applications and environmental protection. J Polym Res. 2022;29(7). [CrossRef]

- Junoh H, Jaafar J, Nik Abdul NAH, et al. Performance of polymer electrolyte membrane for direct methanol fuel cell application: Perspective on morphological structure. Membranes (Basel). 2020;10(3). [CrossRef]

- 26. Peyrovi MH, Parizi MA. The Modification of the BET Surface Area by Considering the Excluded Area of Adsorbed Molecules. Phys Chem Res. 2022;10(2):173-177. [CrossRef]

- Brunauer_Emmett_Teller_BET_Theory.

- Bunaciu AA, Udriştioiu E gabriela, Aboul-Enein HY. X-Ray Diffraction: Instrumentation and Applications. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 2015;45(4):289-299. [CrossRef]

- Lee EJ, Shin DS, Kim HE, Kim HW, Koh YH, Jang JH. Membrane of hybrid chitosan-silica xerogel for guided bone regeneration. Biomaterials. 2009;30(5):743-750. [CrossRef]

- Nur Y, Rohaeti E, Darusman LK. Optical sensor for the determination of Pb2+ based on immobilization of dithizone onto Chitosan-Silica membrane. Indones J Chem. 2017;17(1):7-14. [CrossRef]

- Purwanto M, Widiastuti N, Saga BH, Gusmawan H. Synthesis of Composite Membrane Based Biopolymer Chitosan with Silica from Rice Husk Ash for Direct Methanol Fuel Cell Application. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2021;830(1). [CrossRef]

- Zuo Z, Fu Y, Manthiram A. Novel blend membranes based on acid-base interactions for fuel cells. Polymers (Basel). 2012;4(4):1627-1644. [CrossRef]

- Bai H, Zhang H, He Y, Liu J, Zhang B, Wang J. Enhanced proton conduction of chitosan membrane enabled by halloysite nanotubes bearing sulfonate polyelectrolyte brushes. J Memb Sci. 2014;454:220-232. [CrossRef]

- Kusumastuti E, Siniwi WT, Mahatmanti FW, Jumaeri J, Atmaja L, Widiastuti N. Modification of chitosan membranes with nanosilica particles as polymer electrolyte membranes. AIP Conf Proc. 2016;1725(April 2016). 20 April. [CrossRef]

- Lue SJ, Pai YL, Shih CM, Wu MC, Lai SM. Novel bilayer well-aligned Nafion/graphene oxide composite membranes prepared using spin coating method for direct liquid fuel cells. J Memb Sci. 2015;493:212-223. [CrossRef]

- Widhi Mahatmanti F, Nuryono, Narsito. Physical characteristics of chitosan based film modified with silica and polyethylene glycol. Indones J Chem. 2014;14(2):131-137. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).