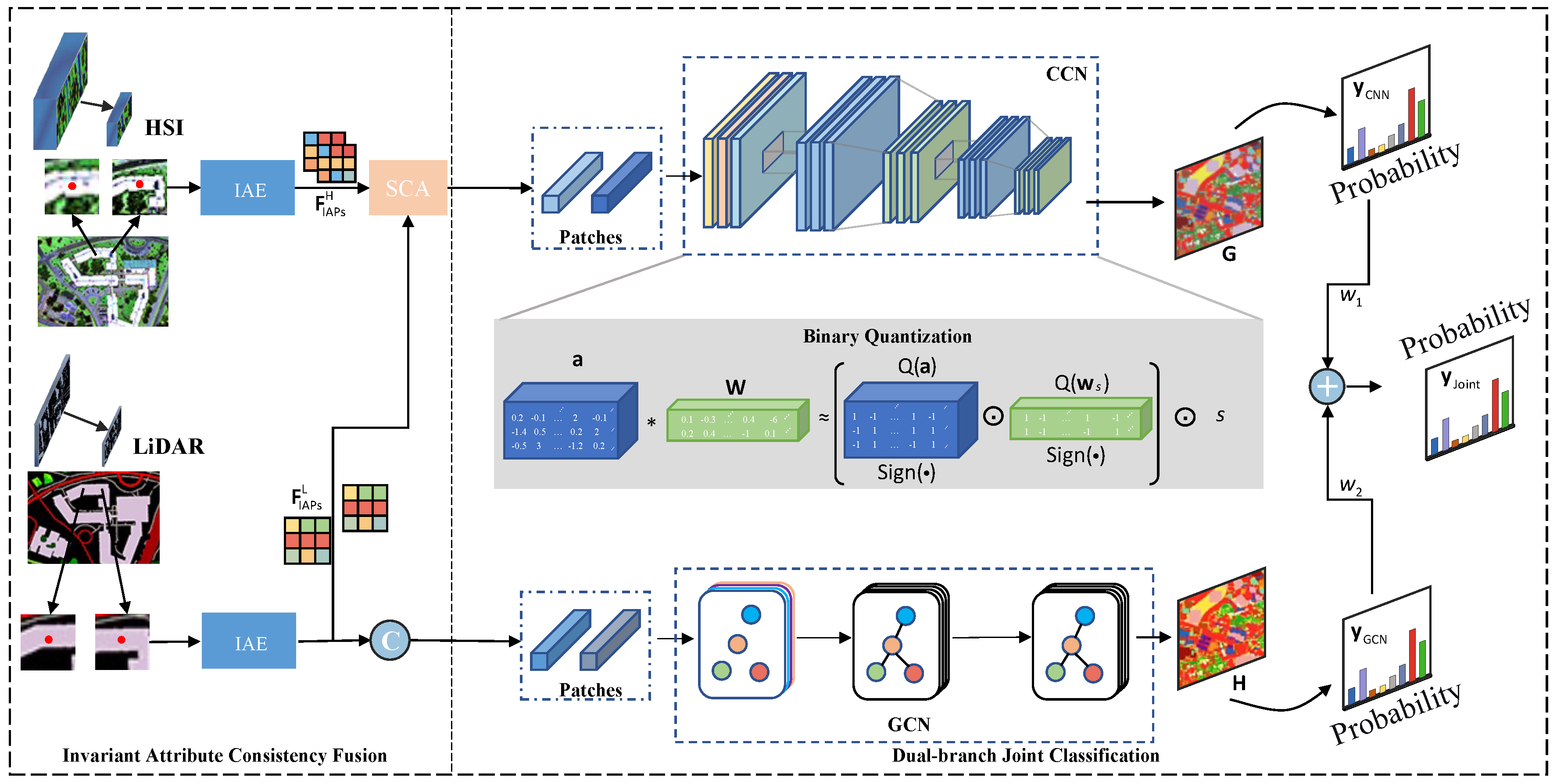

3.1. Invariant Attribute Consistency Fusion

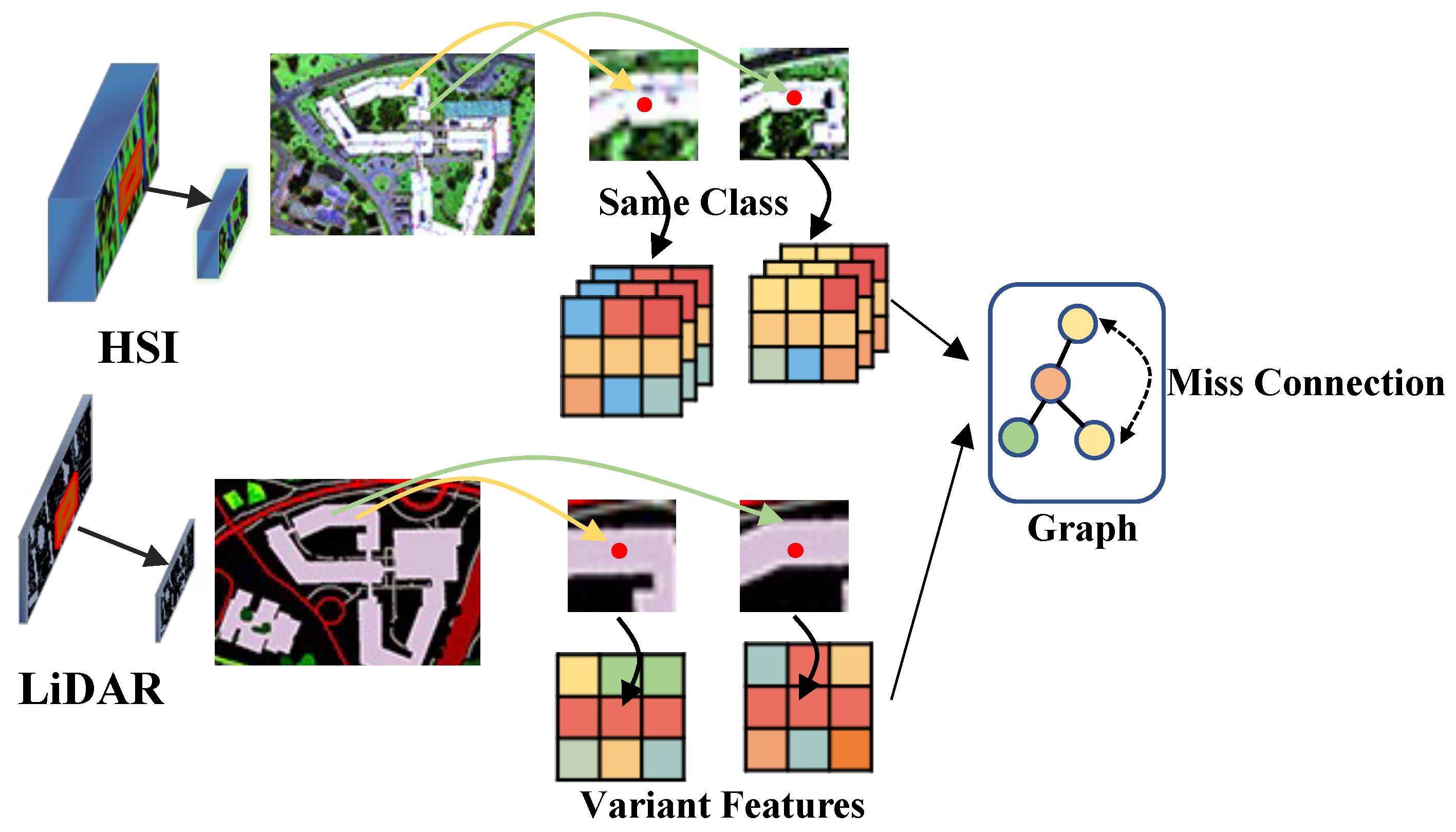

As shown in

Figure 2, the Invariant Attribute Consistency Fusion includes two parts: Invariant Attribute Extraction (IAE) and Spatial-Consistency Fusion (SCF). Extracting invariant attribute features can counteract local semantic changes caused by Pixel rotation and movement or local regional composition changes. We utilize the Invariant Attribute Profiles (IAPs) [

25] for feature extraction to enhance the diversity of features and model the invariant behaviors in multimodal data. This approach generates robust feature extraction for various semantic changes in multimodal remote sensing data. Firstly, the multimodal remote sensing images are filtered using isotropic filters to obtain more robust convolutional features, referred to as Robustness Convolutional Features (RCFs). The RCFs are expressed as:

where,

H represents the HSI,

L represents the LiDAR image,

denotes the RCF extracted from the

k-th band of the multimodal remote sensing image.

is the input remote sensing image,

represents isotropic filtering, achieved by convolving

with

, thereby extracting spatially invariant features from local space. Additionally, robustness is enhanced by utilizing superpixel segmentation methods to enhance the spatial invariance of the features based on object semantics, such as edges, shapes, and their invariance.

where

represents the segmentation of superpixels. Additionally,

and

represent the representations of spatially invariant attribute features for the HSI and LiDAR images, respectively. To achieve invariance to translation and rotation in the frequency domain, we construct a continuous histogram of oriented gradients in Fourier polar coordinates. By utilizing the Fourier-based continuous Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG), we ensure invariant feature extraction in polar coordinates. This approach accurately captures rotation behaviors at any angle. Therefore, by mapping the translation or rotation of image blocks in Fourier polar coordinates, discrete attribute features are transformed into continuous contours. Consequently, we obtain Frequency Invariant Features (FIF) in the frequency domain.

By utilizing the extracted spatially invariant features,

and

, along with the frequency invariant features,

and

, we obtain the joint invariant attribute features, denoted as

:

Spatial-Consistency Fusion is designed to enhance the consistency of similar features in the observed area’s terrain feature information. We employ the Generalized Graph-Based Fusion (GGF) method [

26] to jointly extract consistent feature information of different modalities’ invariant attributes.

where

,

,

and

represent HSI, invariant features of HSI, and invariant features of LiDAR, respectively. The HSI is specifically used to capture the consistency information in the spectral dimension.

is the fusion result.

W denotes the transformation matrix used to reduce the dimensionality of the feature maps, fuse the feature information, preserve local neighborhood information, and detect manifolds embedded in a high-dimensional feature space.

Initially, a graph structure is constructed to describe the correlation between spatial sample points and obtain the edge consistency information of the graph structure for different modalities:

where

,

, and

are defined as the edges of the graph structures

,

and

, respectively. They are obtained through the

k-nearest neighbors (

k-NN) method. When two sample points

i and

j are close in distance (strong correlation),

. When the distance between two sample points is large (weak correlation),

. The likelihood of a data point having similar features to its nearest neighbor is greater than with those points that are far away. Therefore, it is necessary to add a distance constraint when calculating graph edges. This can be defined as:

where

is the pairwise distance matrix between the individual data points in

. In

, the final graph structure

is determined by applying the

k-nearest neighbor approach to identify the edge

. Then,

, the diagonal matrix, is computed based on

. Subsequently, the Laplacian matrix

is obtained through this process:

By combining the known feature information

, the Laplacian matrix

, and the diagonal matrix

, we can use the following generalized eigenvalue calculation formula to obtain different eigenvalues

and their corresponding eigenvectors

:

where,

denotes the transpose matrix of

,

represents the eigenvalue,

with

indicating the number of eigenvalues. Since each eigenvector has its own unique eigenvalue, we can obtain

. Finally, based on all the eigenvectors, we can obtain the desired transformation matrix

:

where,

represents an eigenvector corresponding to the

i-th eigenvalue.

3.2. Bi-Branch Joint Classification

The GCN and CNN are architectural designs used to extract distinct representations of salient information from multimodal remote-sensing images. The CNN specializes in capturing intricate spatial features, while the GCN excels at extracting abundant spectral feature information from multimodal remote sensing images by utilizing spectral vectors as input. Additionally, the GCN can simulate the topological relationships between samples in graph-structured data. We design a bi-branch joint classification combining the advantages of the GCN and CCN to offer various feature diversity.

Traditional GCNs effectively model the relationships between samples to simulate long-range spatial relationships in remote sensing images. However, inputting all samples into the network at once leads to significant memory overhead. To address these issues, the Mini Graph Convolutional Network (MiniGCN) [

27] is introduced to find robust locally optimal feature information by utilizing a sampler for small-sample sampling, dividing the original input graph-structured data into multiple subgraphs. The graph-structured multimodal fused image data is input into the MiniGCN in a matrix form for training. During the training process, the input data is processed and features are extracted and outputted in mini-batches. The classification output can be represented by the following equation:

where,

can be translated as follows:

is the adjacency matrix of spatial-frequency invariant attribute features

,

and

is the modified adjacency matrix.

represents the weight of the

l-th layer in the graph convolutional network.

denotes the diagonal matrix of

.

represents the ReLU non-linear activation function.

represents the feature output of the

l-th layer in the graph convolutional network during the feature extraction process. When

,

corresponds to the original input features.

represents the feature output of the

-th layer in the graph convolutional network, which serves as the final output spectral features.

In addition, we utilize a simple CNN structure [

28] which can be defined as:

Here, the base structure

includes the convolutional layer, batch normalization layer, max-pooling layer, and ReLU layer. Therefore, we use adaptive coefficients to combine the detection results of the two networks, which can be represented as:

where,

represents the classification head function, while

and

refer to the features extracted by the GCN and the CNN, respectively. The

and

are learnable parameters of the network to balance the weight of the bi-branch results.

3.3. Binary Quantization

To ensure the retention of information and minimize information loss during forward propagation, we propose the utilization of Libra Parameter Binarization (Libra-PB) [

29], which incorporates both quantization error and information loss. During forward propagation, the full-precision weights are initially adjusted by subtracting the mean of the weights. This adjustment aims to distribute the quantized values uniformly and normalize the weight, thereby enhancing training stability and mitigating any negative effects caused by weight magnitude. The resultant standardized balanced weight, denoted as

, can be obtained through the following operations:

In the above equation,

represents the standard deviation, while

is the mean of the full-precision weights. The objective of network binarization is to represent the floating-point weights and/or activations using only 1-bit. Generally, the quantization of weights and activations can be defined as:

Here,

and

a represent the floating-point parameters of weights and activations. The

function is commonly employed to obtain binary values, and it can be computed as:

s is an integer parameter used for expanding the representation ability of binary weights. It can be calculated as:

Here,

n represents the dimension of the vector and

denotes its L1-norm. The main operations in the forward propagation of binary CNN, involving quantized weights

and activations

, can be expressed as:

During backward propagation, due to the discontinuity introduced by binarization, gradient approximation becomes necessary. The approximation can be formulated as:

where,

represents the loss function,

denotes the approximation of the sign function, and

is its derivative. In our paper, we use the following approximation function:

3.5. Experimental Setup

Data Description: (1) Houston2013 Data: Experiments were carried out using hyperspectral imaging (HSI) and digital surface model (DSM) data that were obtained in June 2012 over the University of Houston campus and the adjacent urban area. The HSI data consisted of 144 spectral bands and covered a wavelength range from 380 to 1050 nm, with a spatial resolution of 2.5 m that was consistent with the DSM data. The entire dataset covered an area of

pixels and included 15 classes of natural and artificial objects, which were determined through photo interpretation by the DFTC. The LiDAR data was collected at an average sensor height of 2000 feet, while the HSI was collected at an average height of 5500 feet. The scene contained various natural objects such as water, soil, trees, and grass, as well as artificial objects such as parking lots, railways, highways, and roads.

Table 1 reports the land cover classes and the corresponding number of training and testing samples.

(2) Trento Data: It comprises one HSI with 63 spectral bands and one LiDAR data, captured in a rural area located in southern Trento, Italy. The HSI was obtained through the AISA Eagle sensor, while the corresponding LiDAR data was collected using the Optech Airborne Laser Terrain Mapper (ALTM) 3100EA sensor. Both datasets are of size

pixels with a spatial resolution of 1 m, while the wavelength range of HSI is from 0.42 to 0.99

m. This particular data set consists of a total of 30,214 ground-truth samples, with research conducted on 6 distinguishable category labels.

Table 1 reports the land cover classes and the corresponding number of training and testing samples.

Evaluation Metrics: To comprehensively evaluate the performance of multimodal remote sensing image classification algorithms, this article analyzes and compares various algorithms based on their classification prediction maps and accuracy. While the classification prediction map is subject to a certain degree of subjectivity and may not accurately measure the impact of an algorithm on classification performance, this study employs quantitative evaluation metrics such as overall accuracy (OA), average accuracy (AA), and Kappa coefficient to better measure and compare the performance of different algorithms. A higher value of any of these three indicators represents higher classification accuracy and overall better performance of the algorithm. Among these three evaluation metrics, overall accuracy (OA) refers to the ratio of correctly classified test samples to the total number of test samples. Average accuracy (AA) refers to the ratio of correctly classified test samples to the total number of test samples in a specific category. The kappa coefficient is expressed as:

where

N represents the total number of sample points,

represents the values in the diagonal of the confusion matrix obtained after classification, and

and

represent the total number of samples in a certain category as well as the number of samples that have been correctly classified in this category, respectively. Furthermore, we employ Bit-Operations (BOPs) count [

30] and parameters as metrics to evaluate the compression performance. The BOPs for convolution can be determined using the following equation:

Here,

,

, and

represent the height, width, and number of channels of the output feature map of the

layer, respectively.

and

indicate the weight and activation bit-widths of the

layer.

and

correspond to the size of the convolution kernel. The parameters (params) are defined as:

Implementation Details: Our proposed approach is implemented in Python with TensorFlow and trained on 1 RTX 3090 card. All the networks considered in this paper are implemented using the TensorFlow platform. During this process, we set the batch size to 32, utilize Adam with an initial learning rate of 0.005, and perform a total of 200 epochs. The current learning rate is adjusted using an exponential learning rate strategy, where the learning rate is multiplied by every 50 epochs. Additionally, weight regularization is applied using the L2 norm to stabilize network training and reduce overfitting.

3.6. Ablation Study

An ablation study is conducted to demonstrate the validity of the proposed components by evaluating several variants of the IABC on HSI and LiDAR datasets.

Invariant Attribute Consistency Fusion:Table 2 discusses the impact of using IACF (IAE structure and SCA Fusion) on CNN and GNN networks in remote sensing image classification tasks, as well as the comparison between multi-modal and single-modal HSI and LiDAR data. The Houston2013 dataset is used for evaluation, and metrics such as OA, AA, and Kappa coefficient are used to measure classification performance. Firstly, the experimental results for HSI data show that both GCN and CNN networks achieve a certain level of accuracy in classification but differ in precision. The introduction of the IAE structure improves classification performance, increasing OA and AA from 79.04% and 81.16% to 91.15% and 91.78% respectively. This indicates the effectiveness of the IAE structure in improving the accuracy of remote sensing image classification. Secondly, the experimental results for LiDAR data demonstrate a lower classification accuracy when using GCN or CNN networks alone. However, the introduction of the IAE structure significantly improves classification performance. For example, OA increases from 22.74% to 41.81%. This confirms the effectiveness of the IAE structure in processing LiDAR data. Lastly, fusion experiments are conducted with HSI and LiDAR data. The results show that fusing HSI and LiDAR data further improves classification performance. When combining the CNN network, IAE structure, and SCA fusion, the OA performance reaches 91.88%, an increase of 2.43%.

Similarly, on the Trento dataset, as shown in

Table 3, the same conclusions were obtained. In the case of HSI data, when only GCN or CNN was used, the overall accuracy (OA) was 83.96% and 96.06%, respectively. However, when the IAE structure was introduced for invariant feature extraction, the OA accuracy improved to 95.34% (an increase of 11.38%) and 96.93% (an increase of 0.87%) for GCN and CNN, respectively. This indicates that the extraction of spatially invariant attributes can reduce the heterogeneity in extracting pixel features of the same class by CNN and GNN networks, enhancing the discriminative ability for the same class. Moreover, the extraction of invariant attributes has a more significant effect on improving the classification accuracy of the GCN network. When classifying LiDAR data, due to the characteristics of LiDAR data, the performance is relatively low, with only the GCN network achieving an OA of 48.31%. Introducing IAE can improve the GCN network OA by 11.94%. However, introducing IAE to the CNN network instead results in a decrease in classification performance from 90.81% to 68.81%. This might be due to the large size of areas with the same class in the Trento dataset, resulting in minimal elevation changes in the LiDAR images over a considerable area, leading to similar invariant attributes for different classes and interfering with the CNN network’s ability to extract and discriminate local information. This situation can be alleviated when using multimodal data (HSI+LiDAR) for classification. Considering the information from both the HSI and LiDAR, better performance can be observed. Particularly, the best classification performance (OA 98.05%) was achieved when CNN introduced the IAE structure and SCA fusion.

This further demonstrates that SCA fusion can enhance the classification accuracy of the CNN network. In conclusion, this experiment proves that the introduction of the IAE structure significantly improves the classification performance of CNN and GNN networks in remote sensing image classification tasks. Additionally, SCA enhances the classification performance of the CNN network. Furthermore, the fusion of multi-modal data can further improve classification accuracy.

Bi-branch Joint Classification: To analyze the performance of the bi-branch joint network for classification, we compare the different networks in the two datasets in Figure 5. Regarding the Houston2013 dataset, the results showed that CNN achieved an OA of 91.88%, an AA of 92.60%, and a of 91.97%. GCN achieved an OA of 92.60%, an AA of 93.20%, and a of 91.97%. On the other hand, the Joint method achieved an OA of 92.78%, an AA of 93.29%, and a of 92.15%. For the Trento dataset, similar classification experiments were conducted using CNN, GCN, and the Joint method. The results showed that CNN achieved high OA (98.05%) and AA (95.18%), as well as a high (97.73%). GCN obtained lower OA (97.66%) and AA (96.38%), as well as a lower (96.87%). In contrast, the Joint method achieved the best classification results on the Trento dataset, with an OA of 98.14%, an AA of 97.03%, and a of 97.50%. The experimental results demonstrate that using the bi-branch joint network can combine the advantages of CNN and GCN networks, resulting in excellent classification performance in remote sensing image land classification tasks.

Binary Quantization: With the application of binary quantization, we can effectively address resource limitations and enable real-time decision-making capabilities in the context of processing large-scale data in remote sensing applications. To analyze the performance differences, we conducted a comparative study on classification accuracy and computational resources using different quantization strategies on the IABC network. The results are presented in

Table 4, where 32w and 32a denote the full precision of the weight and activation while 1w and 1a represent the binary quantization of the weight and activation. The binary quantization module achieved OA accuracies of 98.14%, 98.16%, 85.33%, and 83.44% at different computational levels. Notably, the difference in OA accuracy between the 1w32a quantization level and the full precision network is relatively small. Additionally, for the CNN network at the 1w32a quantization level, the parameter count is 32.675KB, which accounts for only 3% of the parameter count of the full precision network. Likewise, the BOPs are approximately 3% of the BOPs in the full precision network. It is observed that the accuracy of the classification model decreases as the number of quantization bits decreases. This decrease may be attributed to the reduced number of model parameters, leading to the loss of certain important layer information and consequently resulting in a decline in accuracy. It is observed that the binary quantization of the activations has a significantly bad impact on the classification accuracy, and the OA decreases by 12.81% compared with the full-precision network and 12.53% compared with the quantization weight only (1w32a). Particularly, when using the 1w1a network exclusively, the impact is notably significant, with the resulting 14.7% accuracy reduction compared to a full-precision network. Hence, we only consider the binary quantization of the weights 1w32a in our experiment.

3.7. Quantitative Comparison with the State-of-the-art Classification Network

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed IABC, we compare the experimental results of the IABC on both HSI and LiDAR datasets with those of other competitive classifiers MDL_RS_FC [

28], EndNet [

31], RNN [

18], CALC [

32], ViT [

33] and MFT [

21]. We optimize the parameters of all the compared methods on the same server as described in the original article. Additionally, for a fair comparison, we use identical training and testing samples. Data augmentation techniques are commonly employed to prevent model overfitting and enhance classification accuracy. However, conventional image processing-based methods, such as flipping and rotation, can be easily learned by the model. To ensure a fair comparison with other approaches, our proposed IABC network abstains from utilizing any data augmentation operations.

Table 6 and

Table 7 showcase the objective classification outcomes of various methods on two experimental datasets. The most favorable results in each row are highlighted in red. It can be seen that the proposed IABC is superior to other methods. Taking the Houston2013 as an example, IABC provides approximately 7.67%, 7.6%, 20.32% 2.84%, 7.58% 3.03% OA improvements for MDL_RS_FC, Endnet, RNN, CALC, ViT, and MFT, respectively, and achieve the highest classification accuracy for seven of the 15 categories. RNN performs the worst with only 72.31% OA. Due to its designed cross-fusion strategy, the MDL_RS_FC method achieves better performance which is 84.96% OA because there is more sufficient information interaction in the feature fusion process. Conventional classifier EndNet by leveraging deep neural networks to enhance the ability of feature extraction for spectral and spatial features. Multiple types of feature extraction outperform single-type feature extraction. CALC method achieves the 89.79% OA ranking three which not only fully exploits and mines high-level semantic information and complementary information, but also increases adversarial training, which can effectively preserve detailed information in HSI and LiDAR data. Transformer-based methods ViT and MFT with their strong feature expression ability in high-level sequential abstract representation achieve higher accuracy than the traditional deep learning network (such as Endnet and MDL_RS_FC). In contrast, our IABC method achieves the best performance on OA, AA, and

due to the joint use of spatial–spectral CNN and relation-augmented GCN features with invariant attributes enhancement. For the Trento dataset with higher spatial resolution and fewer feature categories, IABC provides approximately 10.40%, 7.58%, 2.24%, 0.56%, 2.2%, 0.35% improvements for MDL_RS_FC, Endnet, RNN, CALC, ViT, and MFT, respectively, and achieve the highest classification accuracy for three of the 6 categories. The performance of the RNN network on the Trento dataset is noticeably better compared with the result on the Houston2013 dataset while the MDL_RS_FC method performance is worse on the Trento dataset. It is proven that the generalization performance of these two methods is comparatively poor. The performance of other algorithms is consistent with the performance on the Houston2013 dataset.

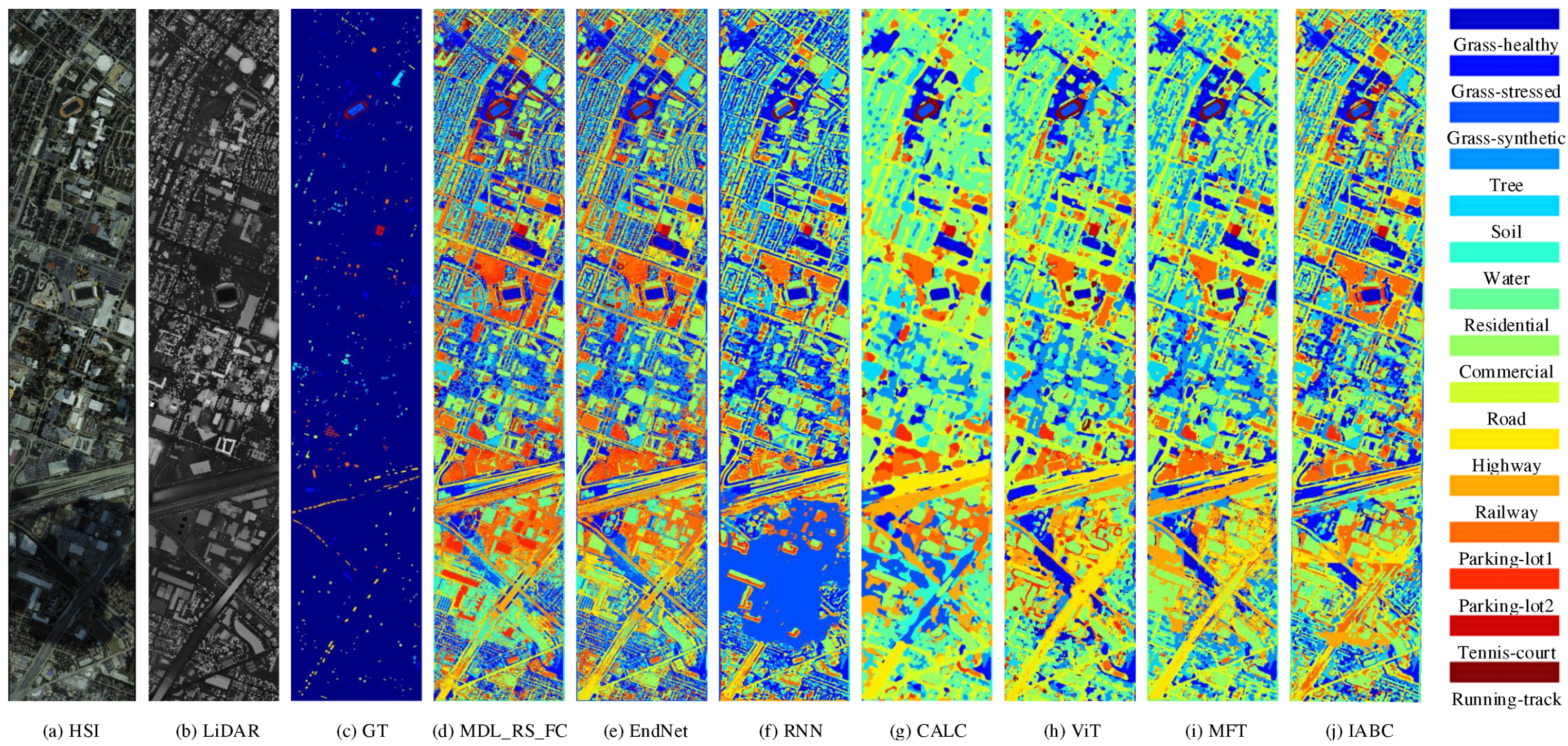

The

Figure 3 illustrates a range of visual data, including hyperspectral false-color images, LiDAR images, ground-truth plots, and classification maps, acquired using various methods on the two datasets. Each category is accompanied by its respective color scheme. Upon thorough evaluation and comparison, it is clear that the proposed methods yield superior results with significantly reduced noise compared to alternative approaches. Deep learning models excel in capturing the nonlinear relationship between input and output features, thanks to their remarkable ability to extract learnable features. Hence, all the methods generate relatively smooth classification maps, effectively distinguishing between different land-use and land-cover classes. Notably, Vit and MFT demonstrate their efficacy in classification by extracting high-level sequential abstract representations from images. Consequently, the classification maps exhibit better visual quality compared to fully connecting, CNN, and RNN networks. By enhancing neighboring spatial-spectral information and facilitating the effective transmission of relation-augmented information across layers, the proposed IABC method achieves highly desirable classification maps, particularly in terms of texture and edge details, surpassing CALC, ViT, and MFT.