Submitted:

12 July 2023

Posted:

14 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study protocol

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

- -

- Studies published in English language;

- -

- In vivo and in vitro studies;

- -

- Studies examining the effects of mandibular flexion on fixed rehabilitations and the factors influencing it;

- -

- Studies highlighting suitable clinical techniques to be adopted to minimise the negative effects of mandibular flexion.

- -

- Studies not published in English language;

- -

- Reviews, systematic reviews and case reports;

- -

- Studies about the mandibular flexure along with any other physiological or pathological problems;

- -

- Articles that review removable prosthodontic treatments.

2.4. Data Extraction and Collection

- -

- Author(s), year and journal of publication, and kind of the study;

- -

- Type of rehabilitation, and sample size;

- -

- Factors that can increase mandibular flexure;

- -

- Preventive measures and suitable techniques to be adopted to minimise the negative effects of this phenomenon on oral rehabilitations.

2.5. Data Synthesis

2.6. Quality Assessment

- -

- Low risk of bias: the study is judged to be at low risk of bias for all domains.

- -

- Moderate risk of bias: the study is judged to be at low or moderate risk of bias for all domains.

- -

- Serious risk of bias: the study is judged to be at serious risk of bias in at least one domain, but not at critical risk of bias in any domain.

- -

- Critical risk of bias: the study is judged to be at critical risk of bias in at least one domain.

3. Results

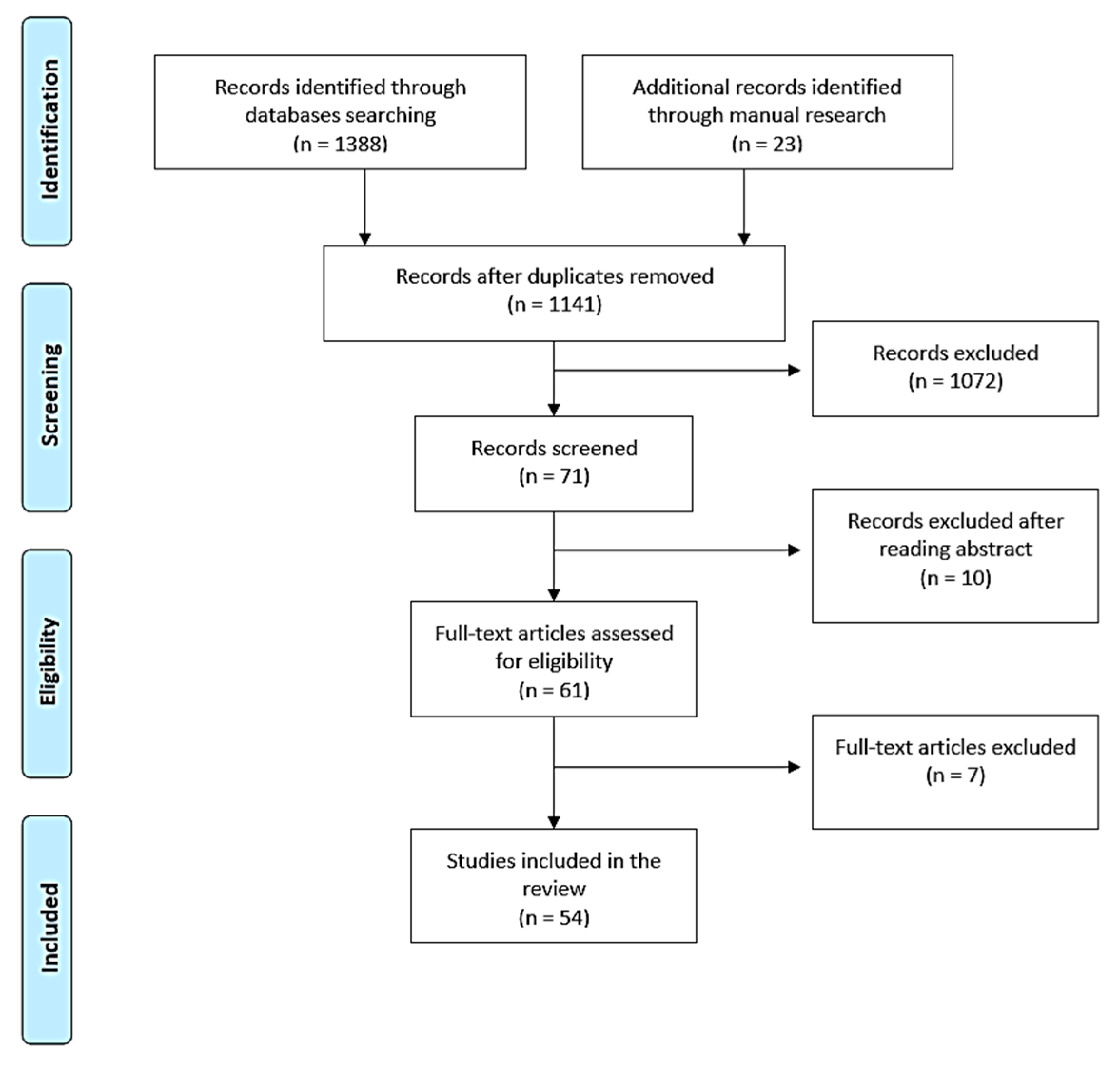

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study characteristics

3.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3.4. Quality Assessment of the Included Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Measurement of mandibular flexion

- -

- Individual factors: facial type, mandibular structure, gonial angle and symphysis characteristics (density, length, and bone surface). Some authors have also proposed age, gender, maximum occlusal force (MOF), height, weight, BMI, muscle pain, bruxism and tooth wear as parameters that may influence mandibular flexion values.

- -

- Measurement techniques: in vivo or in vitro.

- -

- Type of movement performed during measurement: protrusion, mouth opening, laterality and retrusion.

- -

- Area of the mandible where the measurement is performed: incisor-canine, premolar and molar area.

- -

- Clinical condition of the mandible: jaw with teeth or edentulous.

4.1.1. Individual factors

- -

- Brachifacial: is characterised by a reduced angle of the mandibular plane, reduced vertical facial height and a horizontal growth pattern, with maximum muscle anchorage. Brachifacial patients present a short and wide face, a square jaw and strong muscle chains.

- -

- Mesofacial: is characterised by a medium mandibular plane angle, medium vertical facial height, and a mixed growth pattern, with medium muscle anchorage. Mesofacial patients are referred to as “neutral subjects” because no skeletal or muscular features prevail in them, showing a harmonious balance of the vertical and horizontal components of the face.

- -

- Dolichofacial: is characterised by a high mandibular plane angle, high vertical facial height and a vertical growth pattern, with minimal muscle anchorage. Dolichofacial patients have a long, narrow face with a convex profile [78].

4.1.2. Measurement techniques

4.1.3. Type of movement performed during measurement

4.1.4. Area of the mandible where the measurement is performed

4.1.5. Clinical condition of the mandible

4.2. Clinical effects of MMF

4.2.1. MMF and impression-taking

4.2.2. MMF and fixed teeth-supported rehabilitation

4.2.3. MMF and implant-supported full-arch fixed rehabilitations

- -

- Type of prosthesis: single or segmented structure

- -

- Material of the superstructure

- -

- Number and position of implants

Type of prosthesis: single or segmented structure

Material of the superstructure

Number and position of implants

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burch, J.G. Patterns of Change in Human Mandibular Arch Width during Jaw Excursions. Arch Oral Biol 1972, 17, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, J.C.; Chatterji, S.K.; Jeffery, J.W. The Influence That Bone Density and the Orientation and Particle Size of the Mineral Phase Have on the Mechanical Properties of Bone. J Bioeng 1978, 2, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bonfield, W. Elasticity and Viscoelasticity of Cortical Bone. In Natural and Living Biomaterials; CRC Press, 1984 ISBN 978-1-351-07490-2.

- Ashman, R.B.; Van Buskirk, W.C. The Elastic Properties of a Human Mandible. Adv Dent Res 1987, 1, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, J.L.; Meunier, A. The Elastic Anisotropy of Bone. J Biomech 1987, 20, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, G.N.; Nicholls, J.I. Evaluation of Mandibular Arch Width Change. J Prosthet Dent 1981, 46, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hylander, W.L. Stress and Strain in the Mandibular Symphysis of Primates: A Test of Competing Hypotheses. Am J Phys Anthropol 1984, 64, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eijden, T.M. Biomechanics of the Mandible. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2000, 11, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodkind, R.J.; Heringlake, C.B. Mandibular Flexure in Opening and Closing Movements. J Prosthet Dent 1973, 30, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regli, C.P.; Kelly, E.K. The Phenomenon of Decreased Mandibular Arch Width in Opening Movements. J Prosthet Dent 1967, 17, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, R.; Wise, M.D. Mandibular Flexure Associated with Muscle Force Applied in the Retruded Axis Position. J Oral Rehabil 1981, 8, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canabarro, S. de A.; Shinkai, R.S.A. Medial Mandibular Flexure and Maximum Occlusal Force in Dentate Adults. Int J Prosthodont 2006, 19, 177–182.

- Röhrle, O.; Pullan, A.J. Three-Dimensional Finite Element Modelling of Muscle Forces during Mastication. J Biomech 2007, 40, 3363–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Marco, T.J.; Paine, S. Mandibular Dimensional Change. J Prosthet Dent 1974, 31, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischman, B. The Rotational Aspect of Mandibular Flexure. J Prosthet Dent 1990, 64, 483–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linkow, L.I.; Ghalili, R. Ramus Hinges for Excessive Movements of the Condyles: A New Dimension in Mandibular Tripodal Subperiosteal Implants. J Oral Implantol 1999, 25, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinkai, R.S.A.; Canabarro, S. de A.; Schmidt, C.B.; Sartori, E.A. Reliability of a Digital Image Method for Measuring Medial Mandibular Flexure in Dentate Subjects. J Appl Oral Sci 2004, 12, 358–362. [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, A.; Gröndahl, H.G. Direct Digital Radiography in the Dental Office. Int Dent J 1995, 45, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, E.; Gröndahl, H.G. On the Dynamic Range of Different X-Ray Photon Detectors in Intra-Oral Radiography. A Comparison of Image Quality in Film, Charge-Coupled Device and Storage Phosphor Systems. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 1996, 25, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, H.M. Bone “Mass” and the “Mechanostat”: A Proposal. Anat Rec 1987, 219, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, H.M. A 2003 Update of Bone Physiology and Wolff’s Law for Clinicians. Angle Orthod 2004, 74, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantaleo, G.; Acerra, A.; Giordano, F.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Langone, M.; Caggiano, M. Immediate Loading of Fixed Prostheses in Fully Edentulous Jaws: A 7-Year Follow-Up from a Single-Cohort Retrospective Study. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 12427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobkirk, J.A.; Havthoulas, T.K. The Influence of Mandibular Deformation, Implant Numbers, and Loading Position on Detected Forces in Abutments Supporting Fixed Implant Superstructures. J Prosthet Dent 1998, 80, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korioth, T.W.; Hannam, A.G. Deformation of the Human Mandible during Simulated Tooth Clenching. J Dent Res 1994, 73, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Fujisawa, K.; Takechi, M.; Momota, Y.; Yuasa, T.; Tatehara, S.; Nagayama, M.; Yamauchi, E. Effect of the Additional Installation of Implants in the Posterior Region on the Prognosis of Treatment in the Edentulous Mandibular Jaw. Clin Oral Implants Res 2003, 14, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobkirk, J.A.; Schwab, J. Mandibular Deformation in Subjects with Osseointegrated Implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1991, 6, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Horiuchi, M.; Ichikawa, T.; Noda, M.; Matsumoto, N. Use of Interimplant Displacement to Measure Mandibular Distortion during Jaw Movements in Humans. Arch Oral Biol 1997, 42, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paez, C.Y.; Barco, T.; Roushdy, S.; Andres, C. Split-Frame Implant Prosthesis Designed to Compensate for Mandibular Flexure: A Clinical Report. J Prosthet Dent 2003, 89, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodio, W.; Gomes, S.G.F.; Faot, F.; Garcia, R.C.M.R.; Del Bel Cury, A.A. Occlusal Force, Electromyographic Activity of Masticatory Muscles and Mandibular Flexure of Subjects with Different Facial Types. J Appl Oral Sci 2011, 19, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.C.; Lai, Y.L.; Chi, L.Y.; Lee, S.Y. Contributing Factors of Mandibular Deformation during Mouth Opening. J Dent 2000, 28, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favot, L.-M.; Berry-Kromer, V.; Haboussi, M.; Thiebaud, F.; Ben Zineb, T. Numerical Study of the Influence of Material Parameters on the Mechanical Behaviour of a Rehabilitated Edentulous Mandible. Journal of Dentistry 2014, 42, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Arenal, A.; Lasheras, F.S.; Fernández, E.M.; González, I. A Jaw Model for the Study of the Mandibular Flexure Taking into Account the Anisotropy of the Bone. Mathematical and Computer Modelling 2009, 50, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinkai, R.S.; Lazzari, F.L.; Canabarro, S.A.; Gomes, M.; Grossi, M.L.; Hirakata, L.M.; Mota, E.G. Maximum Occlusal Force and Medial Mandibular Flexure in Relation to Vertical Facial Pattern: A Cross-Sectional Study. Head Face Med 2007, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.; Hussain, M.Z.; Shetty, S.K.; Kumar, T.A.; Khaur, M.; George, S.A.; Dalwai, S. Median Mandibular Flexure at Different Mouth Opening and Its Relation to Different Facial Types: A Prospective Clinical Study. J Nat Sci Biol Med 2013, 4, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, C.; Gasparro, R.; Dolce, P.; Bochicchio, V.; Muzii, B.; Sammartino, G.; Marenzi, G.; Maldonato, N.M. The Role of Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Factors in Dental Anxiety: A Mediation Model. Eur J Oral Sci 2021, 129, e12793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, R.M.; Emtiaz, S. Mandibular Flexure and Dental Implants: A Case Report. Implant Dent 2000, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, C.; Bennani, V.; Lyons, K.; Swain, M. Mandibular Flexure and Its Significance on Implant Fixed Prostheses: A Review. J Prosthodont 2012, 21, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, D.O.M.; Dias, K. de C.; Paleari, A.G.; Pero, A.C.; Arioli Filho, J.N.; Compagnoni, M.A. Split-Framework in Mandibular Implant-Supported Prosthesis. Case Rep Dent 2015, 2015, 502394. [CrossRef]

- Sivaraman, K.; Chopra, A.; Venkatesh, S.B. Clinical Importance of Median Mandibular Flexure in Oral Rehabilitation: A Review. J Oral Rehabil 2016, 43, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijiritsky, E.; Shacham, M.; Meilik, Y.; Dekel-Steinkeller, M. Clinical Influence of Mandibular Flexure on Oral Rehabilitation: Narrative Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 16748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Quantitative Analysis of the Decrease in Width of the Mandibular Arch during Forced Movements of the Mandible - James A. McDowell, Carl P. Regli, 1961. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/00220345610400061201 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Osborne, J. Tomlin Medial Convergence of the Mandible. Br. Dental J. 1964, 117, 112–114. [Google Scholar]

- Burch, J.G.; Borchers, G. Method for Study of Mandibular Arch Width Change. J Dent Res 1970, 49, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, C.A. Mandibular Dimensional Change in the Various Jaw Positions and Its Effect upon Prosthetic Appliances. Dent Stud 1972, 50, 19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fischman, B.M. The Influence of Fixed Splints on Mandibular Flexure. J Prosthet Dent 1976, 35, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrario, V.; Sforza, C. Biomechanical Model of the Human Mandible: A Hypothesis Involving Stabilizing Activity of the Superior Belly of Lateral Pterygoid Muscle. J Prosthet Dent 1992, 68, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, R.T.; Hennebel, V.V.; Thongpreda, N.; Van Buskirk, W.C.; Anderson, R.C. Modeling the Biomechanics of the Mandible: A Three-Dimensional Finite Element Study. J Biomech 1992, 25, 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korioth, T.W.P.; Romilly, D.P.; Hannam, A.G. Three-Dimensional Finite Element Stress Analysis of the Dentate Human Mandible. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 1992, 88, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koolstra, J.H.; van Eijden, T.M. Biomechanical Analysis of Jaw-Closing Movements. J Dent Res 1995, 74, 1564–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Latif, H.H.; Hobkirk, J.A.; Kelleway, J.P. Functional Mandibular Deformation in Edentulous Subjects Treated with Dental Implants. Int J Prosthodont 2000, 13, 513–519. [Google Scholar]

- Kemkes-Grottenthaler, A.; Löbig, F.; Stock, F. Mandibular Ramus Flexure and Gonial Eversion as Morphologic Indicators of Sex. Homo 2002, 53, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Ai, M. In Vivo Mandibular Elastic Deformation during Clenching on Pivots. J Oral Rehabil 2002, 29, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarone, F.; Apicella, A.; Nicolais, L.; Aversa, R.; Sorrentino, R. Mandibular Flexure and Stress Build-up in Mandibular Full-Arch Fixed Prostheses Supported by Osseointegrated Implants. Clin Oral Implants Res 2003, 14, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.H.; Ben-Nissan, B.; Conway, R.C. Three-Dimensional Modelling and Finite Element Analysis of the Human Mandible during Clenching. Aust Dent J 2005, 50, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balci, Y.; Yavuz, M.F.; Cağdir, S. Predictive Accuracy of Sexing the Mandible by Ramus Flexure. Homo 2005, 55, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, S.; Wakabayashi, N.; Shiota, M.; Ohyama, T. Stress Analysis in Edentulous Mandibular Bone Supporting Implant-Retained 1-Piece or Multiple Superstructures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2005, 20, 578–583. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sukhun, J.; Helenius, M.; Lindqvist, C.; Kelleway, J. Biomechanics of the Mandible Part I: Measurement of Mandibular Functional Deformation Using Custom-Fabricated Displacement Transducers. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006, 64, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sukhun, J.; Kelleway, J. Biomechanics of the Mandible: Part II. Development of a 3-Dimensional Finite Element Model to Study Mandibular Functional Deformation in Subjects Treated with Dental Implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2007, 22, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El-Sheikh, A.M.; Abdel-Latif, H.H.; Howell, P.G.; Hobkirk, J.A. Midline Mandibular Deformation during Nonmasticatory Functional Movements in Edentulous Subjects with Dental Implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2007, 22, 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Gulsahi, A.; Yüzügüllü, B.; Imirzalioglu, P.; Genç, Y. Assessment of Panoramic Radiomorphometric Indices in Turkish Patients of Different Age Groups, Gender and Dental Status. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2008, 37, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naini, R.B.; Nokar, S. Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis of the Effect of 1-Piece Superstructure on Mandibular Flexure. Implant Dent 2009, 18, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, C.M.; Romeo, D.; Galbusera, F.; Taschieri, S.; Raimondi, M.T.; Zampelis, A.; Francetti, L. Comparison of Tilted versus Nontilted Implant-Supported Prosthetic Designs for the Restoration of the Edentuous Mandible: A Biomechanical Study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2009, 24, 511–517. [Google Scholar]

- Nokar, S.; Baghai Naini, R. The Effect of Superstructure Design on Stress Distribution in Peri-Implant Bone during Mandibular Flexure. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2010, 25, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zaugg, B.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Palla, S.; Gallo, L.M. Implant-Supported Mandibular Splinting Affects Temporomandibular Joint Biomechanics. Clin Oral Implants Res 2012, 23, 897–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madani, A.S.; Asadzadeh, N.; Hosseini, S.H. Mandibular Flexure in Anterior-Posterior and Transverse Plane on Edentulous Patients in Mashhad Faculty of Dentistry. Journal of Dental Materials and Techniques 2012, 1, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, C.; Bennani, V.; Lyons, K.; Swain, M. Influence of Implant Framework and Mandibular Flexure on the Strain Distribution on a Kennedy Class II Mandible Restored with a Long-Span Implant Fixed Restoration: A Pilot Study. J Prosthet Dent 2014, 112, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Jiao, B.; Liu, S.; Guan, F.; Chung, N.-E.; Han, S.-H.; Lee, U.-Y. Sex Determination from the Mandibular Ramus Flexure of Koreans by Discrimination Function Analysis Using Three-Dimensional Mandible Models. Forensic Sci Int 2014, 236, 191.e1-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fernandez, E.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, I.; deLlanos-Lanchares, H.; Mauvezin-Quevedo, M.A.; Brizuela-Velasco, A.; Alvarez-Arenal, A. Mandibular Flexure and Peri-Implant Bone Stress Distribution on an Implant-Supported Fixed Full-Arch Mandibular Prosthesis: 3D Finite Element Analysis. Biomed Res Int 2018, 2018, 8241313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, S.; Parandakh, A.; Khani, M.-M.; Azadikhah, N.; Naraghi, P.; Aeinevand, M.; Nikkhoo, M.; Khojasteh, A. The Effect of Mandibular Flexure on Stress Distribution in the All-on-4 Treated Edentulous Mandible: A Comparative Finite-Element Study Based on Mechanostat Theory. J Long Term Eff Med Implants 2019, 29, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, L.; Bergauer, B.; Adler, W.; Wichmann, M.; Matta, R.E. Three-Dimensional Evaluation of Mandibular Deformation during Mouth Opening. Int J Comput Dent 2019, 22, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tulsani, M.; Maiti, S.; Rupawat, D. Evaluation of Change In Mandibular Width During Maximum Mouth Opening and Protrusion. International Journal of Dentistry and Oral Science 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadian, B.; Abolhasani, M.; Heidarpour, A.; Ziaei, M.; Jowkar, M. Assessment of the Relationship between Maximum Occlusal Force and Median Mandibular Flexure in Adults: A Clinical Trial Study. J Indian Prosthodont Soc 2020, 20, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Klussmann, L.; Schlenz, M.A.; Wöstmann, B. Elastic Deformation of the Mandibular Jaw Revisited-a Clinical Comparison between Digital and Conventional Impressions Using a Reference. Clin Oral Investig 2021, 25, 4635–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülsoy, M.; Tuna, S.H.; Pekkan, G. Evaluation of Median Mandibular Flexure Values in Dentulous and Edentulous Subjects by Using an Intraoral Digital Scanner. J Adv Prosthodont 2022, 14, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, X.; He, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, B. The Effect of Mandibular Flexure on the Design of Implant-Supported Fixed Restorations of Different Facial Types under Two Loading Conditions by Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10, 928656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh, N.; Madani, A.S.; Mirmortazavi, A.; Sabooni, M.R.; Shibani, V. Mandibular Width and Length Deformation during Mouth Opening in Female Dental Students. Journal of Applied Sciences 2012, 12, 1865–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.H.; Conway, R.C.; Taraschi, V.; Ben-Nissan, B. Biomechanics and Functional Distortion of the Human Mandible. J Investig Clin Dent 2015, 6, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Alhaija, E.S.J.; Al Zo’ubi, I.A.; Al Rousan, M.E.; Hammad, M.M. Maximum Occlusal Bite Forces in Jordanian Individuals with Different Dentofacial Vertical Skeletal Patterns. Eur J Orthod 2010, 32, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sella Tunis, T.; May, H.; Sarig, R.; Vardimon, A.D.; Hershkovitz, I.; Shpack, N. Are Chin and Symphysis Morphology Facial Type-Dependent? A Computed Tomography-Based Study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2021, 160, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, D.C. Bone and Bones. Fundamentals of Bone Biology. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 1956, 26, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picton, D.C. Distortion of the Jaws during Biting. Arch Oral Biol 1962, 7, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standlee, J.P.; Caputo, A.A.; Ralph, J.P. Stress Trajectories within the Mandible under Occlusal Loads. J Dent Res 1977, 56, 1297–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongini, F.; Calderale, P.M.; Barberi, G. Relationship between Structure and the Stress Pattern in the Human Mandible. J Dent Res 1979, 58, 2334–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, J.P.; Caputo, A.A. Analysis of Stress Patterns in the Human Mandible. J Dent Res 1975, 54, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clelland, N.L.; Lee, J.K.; Bimbenet, O.C.; Brantley, W.A. A Three-Dimensional Finite Element Stress Analysis of Angled Abutments for an Implant Placed in the Anterior Maxilla. J Prosthodont 1995, 4, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunski, J.B. Biomechanical Factors Affecting the Bone-Dental Implant Interface. Clin Mater 1992, 10, 153–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, D.L. The Scientific Basis for and Clinical Experiences with Straumann Implants Including the ITI Dental Implant System: A Consensus Report. Clin Oral Implants Res 2000, 11 (Suppl. S1), 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaas, S.; Rudolph, H.; Luthardt, R.G. Direct Mechanical Data Acquisition of Dental Impressions for the Manufacturing of CAD/CAM Restorations. J Dent 2007, 35, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flügge, T.V.; Schlager, S.; Nelson, K.; Nahles, S.; Metzger, M.C. Precision of Intraoral Digital Dental Impressions with ITero and Extraoral Digitization with the ITero and a Model Scanner. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2013, 144, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anh, J.-W.; Park, J.-M.; Chun, Y.-S.; Kim, M.; Kim, M. A Comparison of the Precision of Three-Dimensional Images Acquired by 2 Digital Intraoral Scanners: Effects of Tooth Irregularity and Scanning Direction. Korean J Orthod 2016, 46, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallgren, A. The Continuing Reduction of the Residual Alveolar Ridges in Complete Denture Wearers: A Mixed-Longitudinal Study Covering 25 Years. J Prosthet Dent 1972, 27, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, P.J.; Woodhead, C. Changes in Human Mandibular Structure with Age. Arch Oral Biol 1968, 13, 1453–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D Ambrosio, F.; Caggiano, M.; Acerra, A.; Pisano, M.; Giordano, F. Is Ozone a Valid Adjuvant Therapy for Periodontitis and Peri-Implantitis? A Systematic Review. J Pers Med 2023, 13, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.S.; Lang, L.A.; Felton, D.A. Finite Element Stress Analysis on the Effect of Splinting in Fixed Partial Dentures. J Prosthet Dent 1999, 81, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, F.; Uno, I.; Hata, Y.; Neuendorff, G.; Kirsch, A. Analysis of Stress Distribution in a Screw-Retained Implant Prosthesis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2000, 15, 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Torsello, F.; di Torresanto, V.M.; Ercoli, C.; Cordaro, L. Evaluation of the Marginal Precision of One-Piece Complete Arch Titanium Frameworks Fabricated Using Five Different Methods for Implant-Supported Restorations. Clin Oral Implants Res 2008, 19, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindquist, L.W.; Rockler, B.; Carlsson, G.E. Bone Resorption around Fixtures in Edentulous Patients Treated with Mandibular Fixed Tissue-Integrated Prostheses. J Prosthet Dent 1988, 59, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korioth, T.W.; Johann, A.R. Influence of Mandibular Superstructure Shape on Implant Stresses during Simulated Posterior Biting. J Prosthet Dent 1999, 82, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suedam, V.; Souza, E.A.C.; Moura, M.S.; Jacques, L.B.; Rubo, J.H. Effect of Abutment’s Height and Framework Alloy on the Load Distribution of Mandibular Cantilevered Implant-Supported Prosthesis. Clin Oral Implants Res 2009, 20, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalak, R. Biomechanical Considerations in Osseointegrated Prostheses. J Prosthet Dent 1983, 49, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, H.; Caputo, A.A.; Kuroe, T.; Nakahara, H. Biomechanical Comparison of Straight and Staggered Implant Placement Configurations. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2004, 24, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, J.W. Cantilever Rests: An Alternative to the Unsupported Distal Cantilever of Osseointegrated Implant-Supported Prostheses for the Edentulous Mandible. J Prosthet Dent 1992, 68, 817–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemt, T. In Vivo Measurements of Precision of Fit Involving Implant-Supported Prostheses in the Edentulous Jaw. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1996, 11, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.; Wöstmann, B.; Schlenz, M.A. Accuracy of Digital Implant Impressions in Clinical Studies: A Systematic Review. Clin Oral Implants Res 2022, 33, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bra-nemark, P.-I.; Zarb, G.A.; Albrektsson, T.; Rosen, H.M. Tissue-Integrated Prostheses. Osseointegration in Clinical Dentistry. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 1986, 77, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maló, P.; Rangert, B.; Nobre, M. “All-on-Four” Immediate-Function Concept with Brånemark System Implants for Completely Edentulous Mandibles: A Retrospective Clinical Study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2003, 5 (Suppl. S1), 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apicella, A.; Masi, E.; Nicolais, L.; Zarone, F.; de Rosa, N.; Valletta, G. A Finite-Element Model Study of Occlusal Schemes in Full-Arch Implant Restoration. J Mater Sci Mater Med 1998, 9, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashkandi, E.A.; Lang, B.R.; Edge, M.J. Analysis of Strain at Selected Bone Sites of a Cantilevered Implant-Supported Prosthesis. J Prosthet Dent 1996, 76, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zyl, P.P.; Grundling, N.L.; Jooste, C.H.; Terblanche, E. Three-Dimensional Finite Element Model of a Human Mandible Incorporating Six Osseointegrated Implants for Stress Analysis of Mandibular Cantilever Prostheses. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1995, 10, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton, J.L.; Carr, L.; Slabbert, J.C.; Becker, P.J. Survival of Fixed Implant-Supported Prostheses Related to Cantilever Lengths. J Prosthet Dent 1994, 71, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.N.; Caputo, A.A.; Anderkvist, T. Effect of Cantilever Length on Stress Transfer by Implant-Supported Prostheses. J Prosthet Dent 1994, 71, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naert, I.; Quirynen, M.; van Steenberghe, D.; Darius, P. A Study of 589 Consecutive Implants Supporting Complete Fixed Prostheses. Part II: Prosthetic Aspects. J Prosthet Dent 1992, 68, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, A.H.; Zarb, G.A. Research Status of Prosthodontic Procedures. Int J Prosthodont 1993, 6, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Agliardi, E.L.; Francetti, L.; Romeo, D.; Del Fabbro, M. Immediate Rehabilitation of the Edentulous Maxilla: Preliminary Results of a Single-Cohort Prospective Study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2009, 24, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Author, year of publication and reference | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Van Eijden TM, 2000 [8] | It’s a review |

| de Oliveira RM, 2000 [36] | It’s a case report |

| Paez CY, 2003 [28] | It’s a case report |

| Law C, 2012 [37] | It’s a review |

| Marin DO, 2015 [38] | It’s a case report |

| Sivaraman K, 2016 [39] | It’s a review |

| Mijiritsky E, 2022 [40] | It’s a narrative review |

| Author, year of publication and reference | Journal of publication | Study design | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| McDowell JA, 1961 [41] | Journal of Dental Research | Clinical trial | Influence of mandibular movements on MF values |

| Osborne J, 1964 [42] | Br Dent J | Clinical trial | MF measurement |

| Regli CP, 1967 [10] | J Prosthet Dent. | Clinical trial | MF measurement |

| Burch JG, 1970 [43] | J Dent Res. | Clinical trial | Influence of mandibular movements and individual factors on MF values |

| Novak CA, 1972 [44] | Dent Stud. | Clinical trial | MF measurement |

| Burch JG, 1972 [1] | Arch Oral Biol. | Clinical trial | Influence of mandibular movements on MF values |

| Goodkind RJ, 1973 [9] | J Prosthet Dent. | Clinical trial | MF measurement |

| De Marco TJ, 1974 [14] | J Prosthet Dent. | Clinical trial | MF measurement |

| Fischman BM, 1976 [45] | J Prosthet Dent. | Clinical trial | MF reduces when fixed splints are present in natural dentition |

| Gates GN, 1981 [6] | J Prosthet Dent. | Clinical trial | Influence of mandibular movements on MF values |

| Omar R, 1981 [11] | J Oral Rehabil. | Clinical trial | Influence of MF on impression-taking |

| Hylander WL, 1984 [7] | Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Fischman B, 1990 [15] | J Prosthet Dent. | Clinical trial | MF measurement |

| Hobkirk JA, 1991 [26] | Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Ferrario V, 1992 [46] | J Prosthet Dent. | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Hart RT, 1992 [47] | Journal of Biomechanics | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Korioth TW, 1992 [48] | Am J Phys Anthropol | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Koolstra JH, 1995 [49] | J Dent Res. | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Horiuchi M, 1997 [27] | Arch Oral Biol. | Clinical trial | Influence of mandibular movements on MF values |

| Hobkirk JA, 1998 [23] | The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Chen DC, 2000 [30] | J Dent. | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Abdel-Latif HH, 2000 [50] | Int J Prosthodont. | Clinical trial | MF measurement |

| Kemkes-Grottenthaler A, 2002 [51] | Homo | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Jiang T, 2002 [52] | J Oral Rehabil. | Clinical trial | Influence of MF on connected prosthesis supported by natural tooth and implants |

| Zarone F, 2003 [53] | Clin Oral Implants Res. | Clinical trial | Influence of MF on implants and superstructures in different fixed full-arch rehabilitations |

| Shinkai R, 2004 [17] | Journal of Applied Oral Science | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Choi AH, 2005 [54] | Aust Dent J. | Clinical trial | Influence of mandibular movements on MF values |

| Balci Y, 2005 [55] | Homo | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Yokoyama S, 2005 [56] | Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants | Clinical trial | Influence of MF on different superstructures in fixed full-arch rehabilitations |

| Canabarro Sde A, 2006 [12] | Int J Prosthodont. | Clinical trial | Influence of mandibular movements and individual factors on MF values |

| Al-Sukhun J, 2006 [57] | J Oral Maxillofac Surg. | Clinical trial | Influence of mandibular movements on MF values |

| Al-Sukhun J, 2007 [58] | Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. | Clinical trial | Influence of mandibular movements on MF values |

| Shinkai RS, 2007 [33] | Head Face Med. | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| El-Sheikh AM, 2007 [59] | Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants | Clinical trial | Influence of mandibular movements on MF values |

| Gulsahi A, 2008 [60] | Dentomaxillofac Radiol. | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Alvarez-Arenal A, 2009 [32] | Mathematical and Computer Modelling | Clinical trial | Influence of mandibular movements and individual factors on MF values |

| Naini RB, 2009 [61] | Implant Dent | Clinical trial | Influence of MF on different superstructures in fixed full-arch rehabilitations |

| Bellini CM, 2009 [62] | Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants | Clinical trial | Influence of MF on tilted and nontilted implant |

| Nokar S, 2010 [63] | Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants | Clinical trial | Influence of MF on different superstructures in fixed full-arch rehabilitations |

| Custodio W, 2011 [29] | J Appl Oral Sci. | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Zaugg B, 2012 [64] | Clinical Oral Implants Research | Clinical trial | MF values in oral rehabilitation with posterior implants and natural teeth in anterior mandible |

| Madani AS, 2012 [65] | Journal of Dental Materials and Techniques | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Prasad M, 2013 [34] | J Nat Sci Biol Med. | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Law C, 2014 [66] | J Prosthet Dent. | Clinical trial | Influence of MF on the strain distribution in unilateral distal edentulisms |

| Lin C, 2014 [67] | Forensic Sci Int. | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Favot LM, 2014 [31] | J Dent. | Clinical trial | MF values with different superstructure’s material and cortical bone thickness |

| Martin-Fernandez E, 2018 [68] | Biomed Res Int. | Clinical trial | Influence of superstructure type and different mandibular movements on MF in fixed implant rehabilitations |

| Shahriari S, 2019 [69] | J Long Term Eff Med Implants | Clinical trial | Influence of MF on tilted and nontilted implant |

| Wolf L, 2019 [70] | Int J Comput Dent. | Clinical trial | Influence of mandibular movements and individual factors on MF values |

| Tulsani M, 2020 [71] | International Journal of Dentistry and Oral Science | Clinical trial | Influence of mandibular movements on MF values |

| Ebadian B, 2020 [72] | J Indian Prosthodont Soc. | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Schmidt A, 2021 [73] | Clin Oral Investig. | Clinical trial | Influence of MF on different techniques of impression-taking |

| Gülsoy M, 2022 [74] | J Adv Prosthodont. | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Gao J, 2022 [75] | Front Bioeng Biotechnol. | Clinical trial | Influence of individual factors on MF values |

| Author, year of publication and reference | Type of rehabilitation | Sample size | Correlation between MF and individual factors* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burch JG, 1970 [43] | Natural dentition | 10 | Age + |

| Hylander WL, 1984 [7] | Natural dentition | 6 macaca fascicularis | Symphysis characteristics + |

| Hobkirk JA, 1991 [26] | Natural dentition | 3 | Facial type + Symphysis characteristics + |

| Ferrario V, 1992 [46] | Natural dentition | 3D FEM | Age + |

| Hart RT, 1992 [47] | Natural dentition | 3D FEM | Age + |

| Korioth TW, 1992 [48] | Natural dentition | 3D FEM | Age + |

| Koolstra JH, 1995 [49] | Natural dentition | 3D FEM | Age + |

| Hobkirk JA, 1998 [23] | Natural dentition | 3 | Facial type + |

| Chen DC, 2000 [30] | Natural dentition | 62 | Facial type + Gonial angle + Symphysis characteristics + Sex – MOF and parameters that modify it - |

| Kemkes-Grottenthaler A, 2002 [51] | Forensic mandibles and archaeological mandibles | 153 forensic mandibles and 80 archaeological mandibles | Sex + |

| Shinkai R, 2004 [17] | Natural dentition | 7 | Symphysis characteristics + |

| Balci Y, 2005 [55] | Forensic mandibles | 120 mandibles from forensic cases | Sex + |

| Canabarro Sde A, 2006 [12] | Natural dentition | 80 | Gonial angle + Length of the mandibular structure + Sex – Age - MOF and parameters that modify it - |

| Shinkai RS, 2007 [33] | Natural dentition | 51 | Facial type – Sex + MOF and parameters that modify it - |

| Gulsahi A, 2008 [60] | Edentulous, partially and full dentate patients | 1.863 | Sex + |

| Custodio W, 2011 [29] | Natural dentition | 78 | Facial type + |

| Madani AS, 2012 [65] | Natural dentition and edentulous | 50 and 70 | Age - |

| Prasad M, 2013 [34] | Natural dentition | 60 | Facial type + Sex - |

| Lin C, 2014 [67] | Natural dentition | 3D FEM | Sex + |

| Wolf L, 2019 [70] | Natural dentition | 40 | Sex - |

| Ebadian B, 2020 [72] | Natural dentition | 90 | Age + Sex – MOF and parameters that modify it - |

| Gülsoy M, 2022 [74] | Natural dentition and edentulous | 56 and 35 | Age - Sex - |

| Gao J, 2022 [75] | Implant-supported fixed restorations | 3D FEM | Facial type + |

| Author, year of publication and reference | Type of rehabilitation | Sample size | Type of movement* and values of MMF |

|---|---|---|---|

| McDowell JA, 1961 [41] | Natural dentition | 20 | Mouth opening 0.4 mm Protrusion 0.5 mm |

| Osborne J, 1964 [42] | Natural dentition | 18 | Mouth opening 0.07 mm |

| Regli CP, 1967 [10] | Natural dentition | 62 | Mouth opening 0.03-0.09 mm |

| Burch JG, 1970 [43] | Natural dentition | 10 | Mouth opening 0.438 mm Protrusion 0.61 mm Lateral movements 0.243/0.257 mm |

| Novak CA, 1972 [44] | Natural dentition | 50 | Mouth opening 1.00 mm |

| Burch JG, 1972 [1] | Natural dentition | 25 | Mouth opening 0.224 mm Protrusion 0.432 mm Lateral movements 0.112/0.105 mm |

| Goodkind RJ, 1973 [9] | Natural dentition | 40 | Mouth opening 0.031-0.076 mm |

| De Marco TJ, 1974 [14] | Natural dentition | 25 | Mouth opening 0.78 mm |

| Gates GN, 1981 [6] | Natural dentition | 10 | Mouth opening 0-0.3 mm Protrusion 0.1-0.5 mm |

| Omar R, 1981 [11] | Natural dentition | 10 | Mouth opening 0.012-0.164 mm |

| Fischman B, 1990 [15] | Natural dentition | 10 | Mouth opening 0.0711 mm |

| Horiuchi M, 1997 [27] | Natural dentition | 4 | Mouth opening 0.016 mm Protrusion 0.010-0.037 mm |

| Chen DC, 2000 [30] | Natural dentition | 62 | Mouth opening 0.145 mm |

| Shinkai R, 2004 [17] | Natural dentition | 7 |

Mouth opening 0.21-0.44 mm |

| Choi AH, 2005 [54] | Edentulous mandible with implants | 3D FEM | Mouth opening 0.168 mm in the first molar region and 0.256 mm in the second molar region |

| Canabarro Sde A, 2006 [12] | Natural dentition | 80 | Mouth opening 0.146 mm Protrusion 0.15 mm |

| Al-Sukhun J, 2006 [57] | Edentulous patients with implants | 12 | Mouth opening 0.011–0.052 mm Protrusion 0.025-0.057 mm |

| Al-Sukhun J, 2007 [58] | Edentulous patients with implants | 12 | Mouth opening 0.8 mm Protrusion 1.07 mm Lateral movements 1.1/0.9 mm |

| El-Sheikh AM, 2007 [59] | Edentulous patients with implants | 5 | Mouth opening 0.025-0.042 mm Protrusion 0.018-0.053 mm Lateral movements 0.010-0.021 mm |

| Madani AS, 2012 [65] | Natural dentition and edentulous | 50 and 70 | Mouth opening 0.078-0.751 mm |

| Wolf L, 2019 [70] | Natural dentition | 40 | Mouth opening 0.011-0.232 mm |

| Tulsani M, 2020 [71] | Natural dentition | 140 | Mouth opening 0.363 mm Protrusion 0.973 mm |

| Author, year of publication and reference | Type of rehabilitation | Sample size | Results in favour of D/U1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zarone F, 2003 [53] | Full-arch 6-implants-supported rehabilitation | 1 | D |

| Naini RB, 2009 [61] | Full-arch 5-implants-supported rehabilitation | 3D FEM | D |

| Nokar S, 2010 [63] | Full-arch 6-implants-supported rehabilitation | 3D FEM | D |

| Yokoyama S, 2005 [56] | Full-arch 8-implants-supported rehabilitation | 3D FEM | U |

| Martin-Fernandez E, 2018 [68] | Full-arch 6-implants-supported rehabilitation | 3D FEM | U |

| Gao J, 2022 [75] | Full-arch implants-supported rehabilitation | 3D FEM | U |

| Studies | Bias due to confounding |

Bias in selection of participants | Bias in measurement classification of interventions | Bias due to deviations from intended interventions |

Bias due to missing data | Bias in measurement of outcomes | Bias due to selection of the reported result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McDowell JA, 1961 [41] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Osborne J, 1964 [42] | Y/ PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Regli CP, 1967 [10] | Y / PY / PN /N |

Y / PY / PN /N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Burch JG, 1970 [43] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN/N/NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Novak CA, 1972 [44] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Burch JG, 1972 [1] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Goodkind RJ, 1973 [9] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| De Marco TJ, 1974 [14] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Fischman BM, 1976 [45] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Gates GN, 1981 [6] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Omar R, 1981 [11] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Hylander WL, 1984 [7] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Fischman B, 1990 [15] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Hobkirk JA, 1991 [26] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Ferrario V, 1992 [46] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Hart RT, 1992 [47] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Korioth TW, 1992 [48] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Koolstra JH, 1995 [49] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Horiuchi M, 1997 [27] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Hobkirk JA, 1998 [23] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Chen DC, 2000 [30] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Abdel-Latif HH, 2000 [50] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Kemkes-Grottenthaler A, 2002 [51] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Jiang T, 2002 [52] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Zarone F, 2003 [53] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Shinkai R, 2004 [17] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Choi AH, 2005 [54] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Balci Y, 2005 [55] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Yokoyama S, 2005 [56] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Canabarro Sde A, 2006 [12] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Al-Sukhun J, 2006 [57] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Al-Sukhun J, 2007 [58] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Shinkai RS, 2007 [33] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| El-Sheikh AM, 2007 [59] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Gulsahi A, 2008 [60] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Alvarez-Arenal A, 2009 [32] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Naini RB, 2009 [61] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Bellini CM, 2009 [62] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Nokar S, 2010 [63] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Custodio W, 2011 [29] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Zaugg B, 2012 [64] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Madani AS, 2012 [65] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Prasad M, 2013 [34] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Law C, 2014 [66] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Lin C, 2014 [67] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Favot LM, 2014 [31] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Martin-Fernandez E, 2018 [68] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Shahriari S, 2019 [69] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Wolf L, 2019 [70] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Tulsani M, 2020 [71] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Ebadian B, 2020 [72] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Schmidt A, 2021 [73] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Gülsoy M, 2022 [74] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Gao J, 2022 [75] | Y / PY / PN / N |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

Y / PY / PN / N/ NI |

| Risk of bias judgements | MODERATE | SERIOUS | MODERATE | LOW | MODERATE | MODERATE | MODERATE |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).