Submitted:

12 July 2023

Posted:

13 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Historical Perspective

Diagnosis and Frequency of CNR

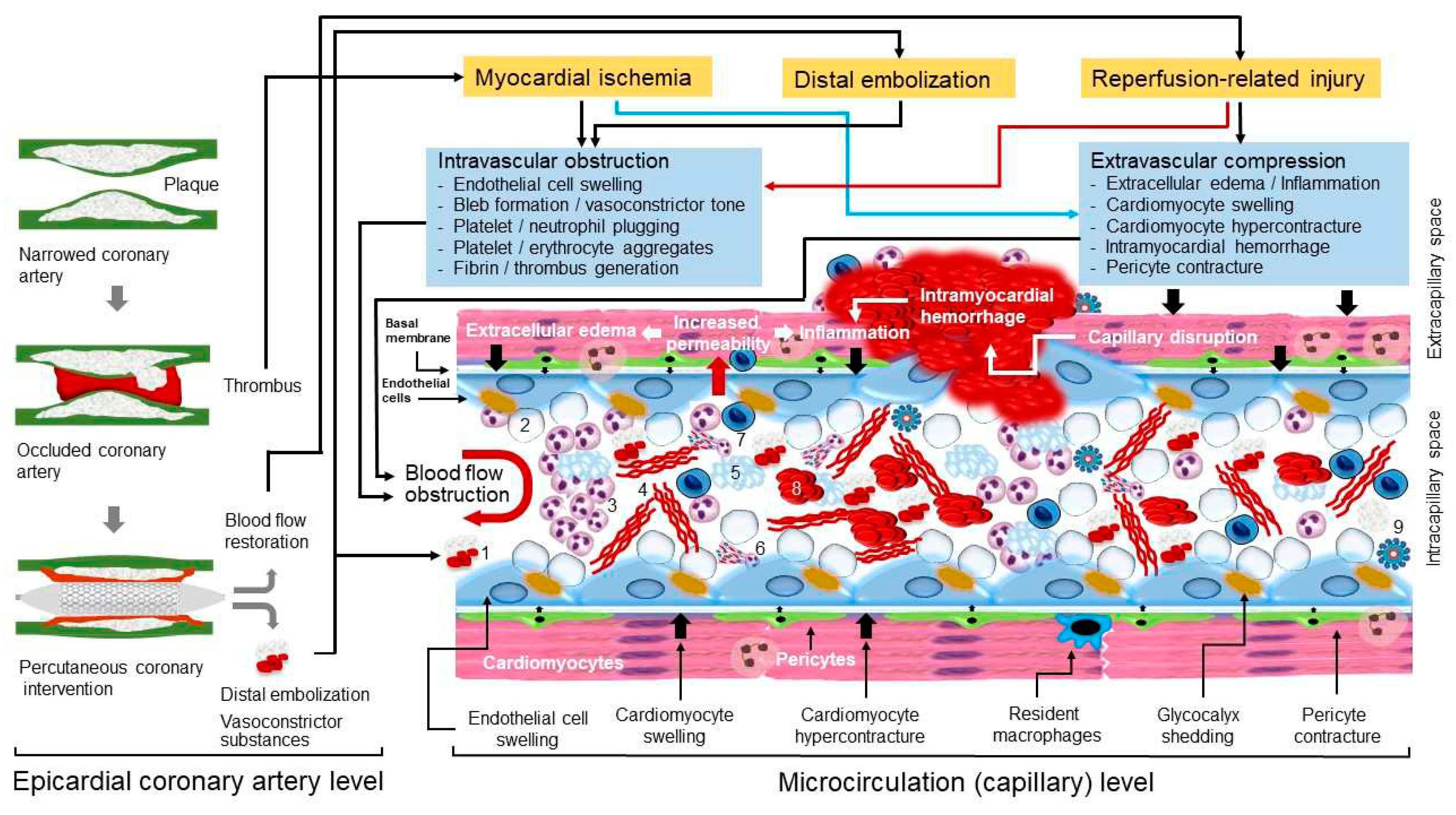

Pathophysiology of CNR

A Short Description of Myocardial Microcirculation

Myocardial Ischemia

Distal Embolization

Reperfusion-Related Injury

Individual Susceptibility (Predisposing Factors) to CNR

Impact of CNR on Clinical Outcome

Therapy of CNR

Therapy against Distal Embolization

Pharmacological Therapy

Concluding Remarks

Funding

Conflicts of interest

References

- Majno, G.; Ames, A.; Chiang, J.; Wright, R. L. No Reflow after Cerebral Ischaemia. Lancet 1967, 2(7515), 569–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, A., 3rd; Wright, R. L.; Kowada, M.; Thurston, J. M.; Majno, G. Cerebral ischemia. II. The no-reflow phenomenon. Am J Pathol 1968, 52(2), 437–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chiang, J.; Kowada, M.; Ames, A., 3rd; Wright, R. L.; Majno, G. Cerebral ischemia. III. Vascular changes. Am J Pathol 1968, 52(2), 455–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harman, J. W. The Significance of Local Vascular Phenomena in the Production of Ischemic Necrosis in Skeletal Muscle. American Journal of Pathology 1948, 24(3), 625–641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, H. L.; Davis, J. C. Renal Ischaemia with Failed Reflow. J Pathol Bacteriol 1959, 78(1), 105–&. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.; DiBona, D. R.; Beck, C. H.; Leaf, A. The role of cell swelling in ischemic renal damage and the protective effect of hypertonic solute. J Clin Invest 1972, 51(1), 118–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, K.; Carroll, R.; Tapp, E. Temporary Ischaemia of Rat Adrenal Gland. J Pathol Bacteriol 1966, 91(1), 235–&. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krug, A.; Du Mesnil de, R.; Korb, G. Blood supply of the myocardium after temporary coronary occlusion. Circ Res 1966, 19(1), 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willms-Kretschmer, K.; Majno, G. Ischemia of the skin. Electron microscopic study of vascular injury. Am J Pathol 1969, 54(3), 327–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kloner, R. A.; Ganote, C. E.; Jennings, R. B. The "no-reflow" phenomenon after temporary coronary occlusion in the dog. J Clin Invest 1974, 54(6), 1496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloner, R. A.; Ganote, C. E.; Whalen, D. A., Jr.; Jennings, R. B. Effect of a transient period of ischemia on myocardial cells. II. Fine structure during the first few minutes of reflow. Am J Pathol 1974, 74(3), 399–422. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, G. "Arterial Embolectomy". Br Med J 1934, 2(3858), 1090–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D. L. Volkmann's ischaemic contracture. Br. J. Surg. 1940, 28, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofer, J.; Montz, R.; Mathey, D. G. Scintigraphic evidence of the "no reflow" phenomenon in human beings after coronary thrombolysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985, 5(3), 593–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, E. R.; Krell, M. J.; Dean, E. N.; O'Neill, W. W.; Vogel, R. A. Demonstration of the "no-reflow" phenomenon by digital coronary arteriography. Am J Cardiol 1986, 57(1), 177–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomerantz, R. M.; Kuntz, R. E.; Diver, D. J.; Safian, R. D.; Baim, D. S. Intracoronary verapamil for the treatment of distal microvascular coronary artery spasm following PTCA. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1991, 24(4), 283–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, H.; Lichstein, E.; Schachter, J.; Shani, J. Early and late angiographic findings of the "no-reflow" phenomenon following direct angioplasty as primary treatment for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 1992, 123(3), 782–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R. F.; Laxson, D. D.; Lesser, J. R.; White, C. W. Intense microvascular constriction after angioplasty of acute thrombotic coronary arterial lesions. Lancet 1989, 1(8642), 807–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.; Tomooka, T.; Sakai, N.; Yu, H.; Higashino, Y.; Fujii, K.; Masuyama, T.; Kitabatake, A.; Minamino, T. Lack of myocardial perfusion immediately after successful thrombolysis. A predictor of poor recovery of left ventricular function in anterior myocardial infarction. Circulation 1992, 85(5), 1699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piana, R. N.; Paik, G. Y.; Moscucci, M.; Cohen, D. J.; Gibson, C. M.; Kugelmass, A. D.; Carrozza, J. P., Jr.; Kuntz, R. E.; Baim, D. S. Incidence and treatment of 'no-reflow' after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 1994, 89(6), 2514–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morishima, I.; Sone, T.; Mokuno, S.; Taga, S.; Shimauchi, A.; Oki, Y.; Kondo, J.; Tsuboi, H.; Sassa, H. Clinical significance of no-reflow phenomenon observed on angiography after successful treatment of acute myocardial infarction with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Am Heart J 1995, 130(2), 239–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morishima, I.; Sone, T.; Okumura, K.; Tsuboi, H.; Kondo, J.; Mukawa, H.; Matsui, H.; Toki, Y.; Ito, T.; Hayakawa, T. Angiographic no-reflow phenomenon as a predictor of adverse long-term outcome in patients treated with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty for first acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000, 36(4), 1202–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakusan, K.; Flanagan, M. F.; Geva, T.; Southern, J.; Van Praagh, R. Morphometry of human coronary capillaries during normal growth and the effect of age in left ventricular pressure-overload hypertrophy. Circulation 1992, 86(1), 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, S.; Jayaweera, A. R. Coronary and myocardial blood volumes: noninvasive tools to assess the coronary microcirculation? Circulation 1997, 96(3), 719–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kaul, S. Evaluating the 'no reflow' phenomenon with myocardial contrast echocardiography. Basic Res Cardiol 2006, 101(5), 391–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzer, P.; Leigh, R.; Berry, C.; van de Hoef, T.; Heiss, W. D.; Senior, R.; Schwartz, A.; Rischpler, C.; Liebeskind, D. Salutary reperfusion is the ultimate target of ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) and Acute Ischemic Stroke (AIS) interventions and should be routinely assessed in standard clinical and research protocols. Card Res Med 2017, 1, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Heusch, G. Coronary microvascular obstruction: the new frontier in cardioprotection. Basic Res Cardiol 2019, 114(6), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiuto, L.; Lombardo, A.; Maseri, A.; Santoro, L.; Porto, I.; Cianflone, D.; Rebuzzi, A. G.; Crea, F. Temporal evolution and functional outcome of no reflow: sustained and spontaneously reversible patterns following successful coronary recanalisation. Heart 2003, 89(7), 731–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Jayaweera, A. R.; Firoozan, S.; Linka, A.; Skyba, D. M.; Kaul, S. Basis for detection of stenosis using venous administration of microbubbles during myocardial contrast echocardiography: bolus or continuous infusion? J Am Coll Cardiol 1998, 32(1), 252–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, R.; Indermuhle, A.; Reinhardt, J.; Meier, P.; Siegrist, P. T.; Namdar, M.; Kaufmann, P. A.; Seiler, C. The quantification of absolute myocardial perfusion in humans by contrast echocardiography: algorithm and validation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005, 45(5), 754–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausenloy, D. J.; Chilian, W.; Crea, F.; Davidson, S. M.; Ferdinandy, P.; Garcia-Dorado, D.; van Royen, N.; Schulz, R.; Heusch, G.; Action, E.-C. C. The coronary circulation in acute myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury: a target for cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res 2019, 115(7), 1143–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B. N.; Chahal, N. S.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Li, W.; Roussin, I.; Khattar, R. S.; Senior, R. The feasibility and clinical utility of myocardial contrast echocardiography in clinical practice: results from the incorporation of myocardial perfusion assessment into clinical testing with stress echocardiography study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2014, 27(5), 520–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndrepepa, G.; Mehilli, J.; Schulz, S.; Iijima, R.; Keta, D.; Byrne, R. A.; Pache, J.; Seyfarth, M.; Schomig, A.; Kastrati, A. Prognostic significance of epicardial blood flow before and after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008, 52(7), 512–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, J. P.; Zijlstra, F.; van 't Hof, A. W.; de Boer, M. J.; Dambrink, J. H.; Gosselink, M.; Hoorntje, J. C.; Suryapranata, H. Angiographic assessment of reperfusion in acute myocardial infarction by myocardial blush grade. Circulation 2003, 107(16), 2115–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitel, I.; Wohrle, J.; Suenkel, H.; Meissner, J.; Kerber, S.; Lauer, B.; Pauschinger, M.; Birkemeyer, R.; Axthelm, C.; Zimmermann, R.; Neuhaus, P.; Brosteanu, O.; de Waha, S.; Desch, S.; Gutberlet, M.; Schuler, G.; Thiele, H. Intracoronary compared with intravenous bolus abciximab application during primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: cardiac magnetic resonance substudy of the AIDA STEMI trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013, 61(13), 1447–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndrepepa, G.; Alger, P.; Fusaro, M.; Kufner, S.; Seyfarth, M.; Keta, D.; Mehilli, J.; Schomig, A.; Kastrati, A. Impact of perfusion restoration at epicardial and tissue levels on markers of myocardial necrosis and clinical outcome of patients with acute myocardial infarction. EuroIntervention 2011, 7(1), 128–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C. M.; Cannon, C. P.; Daley, W. L.; Dodge, J. T., Jr.; Alexander, B., Jr.; Marble, S. J.; McCabe, C. H.; Raymond, L.; Fortin, T.; Poole, W. K.; Braunwald, E. TIMI frame count: a quantitative method of assessing coronary artery flow. Circulation 1996, 93(5), 879–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, C. M.; Murphy, S. A.; Rizzo, M. J.; Ryan, K. A.; Marble, S. J.; McCabe, C. H.; Cannon, C. P.; Van de Werf, F.; Braunwald, E. Relationship between TIMI frame count and clinical outcomes after thrombolytic administration. Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Study Group. Circulation 1999, 99(15), 1945–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, S.; Nishiue, T.; Nakamura, S.; Sugiura, T.; Kamihata, H.; Miyoshi, H.; Imuro, Y.; Iwasaka, T. TIMI frame count immediately after primary coronary angioplasty as a predictor of functional recovery in patients with TIMI 3 reperfused acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001, 38(3), 666–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohara, Y.; Hiasa, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Ogura, R.; Ogata, T.; Yuba, K.; Kusunoki, K.; Hosokawa, S.; Kishi, K.; Ohtani, R. Relation between the TIMI frame count and the degree of microvascular injury after primary coronary angioplasty in patients with acute anterior myocardial infarction. Heart 2005, 91(1), 64–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van 't Hof, A. W.; Liem, A.; Suryapranata, H.; Hoorntje, J. C.; de Boer, M. J.; Zijlstra, F. Angiographic assessment of myocardial reperfusion in patients treated with primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: myocardial blush grade. Zwolle Myocardial Infarction Study Group. Circulation 1998, 97(23), 2302–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouleti, C.; Mewton, N.; Germain, S. The no-reflow phenomenon: State of the art. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2015, 108(12), 661–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allencherril, J.; Jneid, H.; Atar, D.; Alam, M.; Levine, G.; Kloner, R. A.; Birnbaum, Y. Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management of the No-Reflow Phenomenon. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2019, 33(5), 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, J.; Mewton, N.; Croisille, P.; Staat, P.; Bonnefoy-Cudraz, E.; Ovize, M.; Revel, D. Comparison of the angiographic myocardial blush grade with delayed-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance for the assessment of microvascular obstruction in acute myocardial infarctions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2009, 74(7), 1000–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijveldt, R.; van der Vleuten, P. A.; Hirsch, A.; Beek, A. M.; Tio, R. A.; Tijssen, J. G.; Piek, J. J.; van Rossum, A. C.; Zijlstra, F. Early electrocardiographic findings and MR imaging-verified microvascular injury and myocardial infarct size. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2009, 2(10), 1187–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampinga, M. A.; Nijsten, M. W.; Gu, Y. L.; Dijk, W. A.; de Smet, B. J.; van den Heuvel, A. F.; Tan, E. S.; Zijlstra, F. Is the myocardial blush grade scored by the operator during primary percutaneous coronary intervention of prognostic value in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction in routine clinical practice? Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2010, 3(3), 216–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorajja, P.; Gersh, B. J.; Costantini, C.; McLaughlin, M. G.; Zimetbaum, P.; Cox, D. A.; Garcia, E.; Tcheng, J. E.; Mehran, R.; Lansky, A. J.; Kandzari, D. E.; Grines, C. L.; Stone, G. W. Combined prognostic utility of ST-segment recovery and myocardial blush after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2005, 26(7), 667–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijveldt, R.; Beek, A. M.; Hirsch, A.; Stoel, M. G.; Hofman, M. B.; Umans, V. A.; Algra, P. R.; Twisk, J. W.; van Rossum, A. C. Functional recovery after acute myocardial infarction: comparison between angiography, electrocardiography, and cardiovascular magnetic resonance measures of microvascular injury. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008, 52(3), 181–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndrepepa, G.; Tiroch, K.; Fusaro, M.; Keta, D.; Seyfarth, M.; Byrne, R. A.; Pache, J.; Alger, P.; Mehilli, J.; Schomig, A.; Kastrati, A. 5-year prognostic value of no-reflow phenomenon after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010, 55(21), 2383–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D. T.; Leung, M. C.; Richardson, J. D.; Puri, R.; Bertaso, A. G.; Williams, K.; Meredith, I. T.; Teo, K. S.; Worthley, M. I.; Worthley, S. G. Cardiac magnetic resonance derived late microvascular obstruction assessment post ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction is the best predictor of left ventricular function: a comparison of angiographic and cardiac magnetic resonance derived measurements. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2012, 28(8), 1971–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wong, D. T.; Leung, M. C.; Das, R.; Liew, G. Y.; Teo, K. S.; Chew, D. P.; Meredith, I. T.; Worthley, M. I.; Worthley, S. G. Intracoronary ECG during primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction predicts microvascular obstruction and infarct size. Int J Cardiol 2013, 165(1), 61–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, E.; Abraham, J. M.; Pride, Y. B.; Harrigan, C. J.; Peters, D. C.; Biller, L. H.; Manning, W. J.; Gibson, C. M. Association of Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Myocardial Perfusion Grade with cardiovascular magnetic resonance measures of infarct architecture after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2009, 158(1), 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, C. M.; Kirtane, A. J.; Morrow, D. A.; Palabrica, T. M.; Murphy, S. A.; Stone, P. H.; Scirica, B. M.; Jennings, L. K.; Herrmann, H. C.; Cohen, D. J.; McCabe, C. H.; Braunwald, E.; Group, T. S. Association between thrombolysis in myocardial infarction myocardial perfusion grade, biomarkers, and clinical outcomes among patients with moderate- to high-risk acute coronary syndromes: observations from the randomized trial to evaluate the relative PROTECTion against post-PCI microvascular dysfunction and post-PCI ischemia among antiplatelet and antithrombotic agents-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 30 (PROTECT-TIMI 30). Am Heart J 2006, 152(4), 756–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bulluck, H.; Dharmakumar, R.; Arai, A. E.; Berry, C.; Hausenloy, D. J. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Acute ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Recent Advances, Controversies, and Future Directions. Circulation 2018, 137(18), 1949–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mather, A. N.; Lockie, T.; Nagel, E.; Marber, M.; Perera, D.; Redwood, S.; Radjenovic, A.; Saha, A.; Greenwood, J. P.; Plein, S. Appearance of microvascular obstruction on high resolution first-pass perfusion, early and late gadolinium enhancement CMR in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2009, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijveldt, R.; Hofman, M. B.; Hirsch, A.; Beek, A. M.; Umans, V. A.; Algra, P. R.; Piek, J. J.; van Rossum, A. C. Assessment of microvascular obstruction and prediction of short-term remodeling after acute myocardial infarction: cardiac MR imaging study. Radiology 2009, 250(2), 363–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, R. A.; Murphy, C. A.; Petrie, C. J.; Martin, T. N.; Balmain, S.; Clements, S.; Steedman, T.; Wagner, G. S.; Dargie, H. J.; McMurray, J. J. Microvascular obstruction remains a portent of adverse remodeling in optimally treated patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction after acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2010, 3(4), 360–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A. J.; Al-Saadi, N.; Abdel-Aty, H.; Schulz-Menger, J.; Messroghli, D. R.; Friedrich, M. G. Detection of acutely impaired microvascular reperfusion after infarct angioplasty with magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation 2004, 109(17), 2080–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waha, S.; Patel, M. R.; Granger, C. B.; Ohman, E. M.; Maehara, A.; Eitel, I.; Ben-Yehuda, O.; Jenkins, P.; Thiele, H.; Stone, G. W. Relationship between microvascular obstruction and adverse events following primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: an individual patient data pooled analysis from seven randomized trials. Eur Heart J 2017, 38(47), 3502–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, E.; Hadamitzky, M.; Ndrepepa, G.; Bauer, C.; Ibrahim, T.; Ott, I.; Laugwitz, K. L.; Schunkert, H.; Kastrati, A. Microvascular obstruction in patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2014, 30(6), 1087–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrens, X. H.; Doevendans, P. A.; Ophuis, T. J.; Wellens, H. J. A comparison of electrocardiographic changes during reperfusion of acute myocardial infarction by thrombolysis or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Am Heart J 2000, 139(3), 430–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, G. M.; Valenti, R.; Buonamici, P.; Bolognese, L.; Cerisano, G.; Moschi, G.; Trapani, M.; Antoniucci, D.; Fazzini, P. F. Relation between ST-segment changes and myocardial perfusion evaluated by myocardial contrast echocardiography in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with direct angioplasty. Am J Cardiol 1998, 82(8), 932–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konijnenberg, L. S. F.; Damman, P.; Duncker, D. J.; Kloner, R. A.; Nijveldt, R.; van Geuns, R. M.; Berry, C.; Riksen, N. P.; Escaned, J.; van Royen, N. Pathophysiology and diagnosis of coronary microvascular dysfunction in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res 2020, 116(4), 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, S.; Ito, H. Microvasculature in acute myocardial ischemia: part I: evolving concepts in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Circulation 2004, 109(2), 146–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurose, I.; Anderson, D. C.; Miyasaka, M.; Tamatani, T.; Paulson, J. C.; Todd, R. F.; Rusche, J. R.; Granger, D. N. Molecular determinants of reperfusion-induced leukocyte adhesion and vascular protein leakage. Circ Res 1994, 74(2), 336–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heusch, G. The Coronary Circulation as a Target of Cardioprotection. Circ Res 2016, 118(10), 1643–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stempien-Otero, A.; Karsan, A.; Cornejo, C. J.; Xiang, H.; Eunson, T.; Morrison, R. S.; Kay, M.; Winn, R.; Harlan, J. Mechanisms of hypoxia-induced endothelial cell death. Role of p53 in apoptosis. J Biol Chem 1999, 274(12), 8039–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeris, T.; Baines, C. P.; Krenz, M.; Korthuis, R. J. Ischemia/Reperfusion. Compr Physiol 2016, 7(1), 113–170. [Google Scholar]

- Baldea, I.; Teacoe, I.; Olteanu, D. E.; Vaida-Voievod, C.; Clichici, A.; Sirbu, A.; Filip, G. A.; Clichici, S. Effects of different hypoxia degrees on endothelial cell cultures-Time course study. Mech Ageing Dev 2018, 172, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, R. B.; Reimer, K. A. The cell biology of acute myocardial ischemia. Annu Rev Med 1991, 42, 225–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbergen, C.; Hill, M. L.; Jennings, R. B. Volume regulation and plasma membrane injury in aerobic, anaerobic, and ischemic myocardium in vitro. Effects of osmotic cell swelling on plasma membrane integrity. Circ Res 1985, 57(6), 864–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasseckert, S. A.; Schafer, C.; Kluger, A.; Gligorievski, D.; Tillmann, J.; Schluter, K. D.; Noll, T.; Sauer, H.; Piper, H. M.; Abdallah, Y. Stimulation of cGMP signalling protects coronary endothelium against reperfusion-induced intercellular gap formation. Cardiovasc Res 2009, 83(2), 381–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndrepepa, G.; Colleran, R.; Kastrati, A. Reperfusion injury in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the final frontier. Coron Artery Dis 2017, 28(3), 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, C. E.; Lum, H. Update on pulmonary edema: the role and regulation of endothelial barrier function. Endothelium 2001, 8(2), 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waschke, J.; Curry, F. E.; Adamson, R. H.; Drenckhahn, D. Regulation of actin dynamics is critical for endothelial barrier functions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005, 288(3), H1296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, L.; Gavin, J. B. The role of post-ischaemic reperfusion in the development of microvascular incompetence and ultrastructural damage in the myocardium. Basic Res Cardiol 1991, 86(6), 544–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, H. F. Discovery of vascular permeability factor (VPF). Exp Cell Res 2006, 312(5), 522–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, S. M.; Cheresh, D. A. Pathophysiological consequences of VEGF-induced vascular permeability. Nature 2005, 437(7058), 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsenigo, F.; Giampietro, C.; Ferrari, A.; Corada, M.; Galaup, A.; Sigismund, S.; Ristagno, G.; Maddaluno, L.; Koh, G. Y.; Franco, D.; Kurtcuoglu, V.; Poulikakos, D.; Baluk, P.; McDonald, D.; Grazia Lampugnani, M.; Dejana, E. Phosphorylation of VE-cadherin is modulated by haemodynamic forces and contributes to the regulation of vascular permeability in vivo. Nat Commun 2012, 3, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Venema, V. J.; Venema, R. C.; Tsai, N.; Behzadian, M. A.; Caldwell, R. B. VEGF-induced permeability increase is mediated by caveolae. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999, 40(1), 157–67. [Google Scholar]

- Scotland, R. S.; Cohen, M.; Foster, P.; Lovell, M.; Mathur, A.; Ahluwalia, A.; Hobbs, A. J. C-type natriuretic peptide inhibits leukocyte recruitment and platelet-leukocyte interactions via suppression of P-selectin expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102(40), 14452–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerner, T.; Ahlers, O.; Reschreiter, H.; Buhrer, C.; Mockel, M.; Gerlach, H. Adhesion molecules in different treatments of acute myocardial infarction. Crit Care 2001, 5(3), 145–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, H.; Duling, B. R. Identification of distinct luminal domains for macromolecules, erythrocytes, and leukocytes within mammalian capillaries. Circulation Research 1996, 79(3), 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarova, H.; Ambruzova, B.; Sindlerova, L. S.; Klinke, A.; Kubala, L. Modulation of Endothelial Glycocalyx Structure under Inflammatory Conditions. Mediat Inflamm 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ostergaard, L.; Kristiansen, S. B.; Angleys, H.; Frokiaer, J.; Hasenkam, J. M.; Jespersen, S. N.; Botker, H. E. The role of capillary transit time heterogeneity in myocardial oxygenation and ischemic heart disease. Basic Research in Cardiology 2014, 109(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiharajima, S.; Aida, T.; Nakagawa, R.; Kameyama, K.; Sugano, K.; Oguro, T.; Asano, G. Early membrane damage during ischemia in rat heart. Exp Mol Pathol 1986, 44(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarnowska, E.; Karwatowskaprokopczuk, E. Ultrastructural Demonstration of Endothelial Glycocalyx Disruption in the Reperfused Rat-Heart - Involvement of Oxygen-Free Radicals. Basic Research in Cardiology 1995, 90(5), 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Gayosso, I.; Platts, S. H.; Duling, B. R. Reactive oxygen species mediate modification of glycocalyx during ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006, 290(6), H2247–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, H.; Constantinescu, A. A.; Spaan, J. A. Oxidized lipoproteins degrade the endothelial surface layer : implications for platelet-endothelial cell adhesion. Circulation 2000, 101(13), 1500–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwdorp, M.; Mooij, H. L.; Kroon, J.; Atasever, B.; Spaan, J. A.; Ince, C.; Holleman, F.; Diamant, M.; Heine, R. J.; Hoekstra, J. B.; Kastelein, J. J.; Stroes, E. S.; Vink, H. Endothelial glycocalyx damage coincides with microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2006, 55(4), 1127–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, D.; Hofmann-Kiefer, K.; Jacob, M.; Rehm, M.; Briegel, J.; Welsch, U.; Conzen, P.; Becker, B. F. TNF-alpha induced shedding of the endothelial glycocalyx is prevented by hydrocortisone and antithrombin. Basic Res Cardiol 2009, 104(1), 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granger, D. N.; Kvietys, P. R. Reperfusion therapy-What's with the obstructed, leaky and broken capillaries? Pathophysiology 2017, 24(4), 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R. G.; Patel, V.; Dull, R. O. Human glycocalyx shedding: Systematic review and critical appraisal. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2021, 65(5), 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruegger, D.; Rehm, M.; Jacob, M.; Chappell, D.; Stoeckelhuber, M.; Welsch, U.; Conzen, P.; Becker, B. F. Exogenous nitric oxide requires an endothelial glycocalyx to prevent postischemic coronary vascular leak in guinea pig hearts. Crit Care 2008, 12(3), R73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, B. M.; Vink, H.; Spaan, J. A. The endothelial glycocalyx protects against myocardial edema. Circ Res 2003, 92(6), 592–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, D.; Dorfler, N.; Jacob, M.; Rehm, M.; Welsch, U.; Conzen, P.; Becker, B. F. Glycocalyx protection reduces leukocyte adhesion after ischemia/reperfusion. Shock 2010, 34(2), 133–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappell, D.; Brettner, F.; Doerfler, N.; Jacob, M.; Rehm, M.; Bruegger, D.; Conzen, P.; Jacob, B.; Becker, B. F. Protection of glycocalyx decreases platelet adhesion after ischaemia/reperfusion: an animal study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2014, 31(9), 474–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaventura, A.; Montecucco, F.; Dallegri, F. Cellular recruitment in myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Eur J Clin Invest 2016, 46(6), 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, T.; Jaffe, R.; Segev, A.; Bang, K. W.; Qiang, B.; Sparkes, J. D.; Butany, J.; Dick, A. J.; Freedman, J.; Strauss, B. H. Effects of distal embolization on the timing of platelet and inflammatory cell activation in interventional coronary no-reflow. Thromb Res 2010, 126(1), 50–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battinelli, E. M.; Markens, B. A.; Italiano, J. E., Jr. Release of angiogenesis regulatory proteins from platelet alpha granules: modulation of physiologic and pathologic angiogenesis. Blood 2011, 118(5), 1359–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, M.; Wang, X.; Peter, K. Platelets in cardiac ischaemia/reperfusion injury: a promising therapeutic target. Cardiovasc Res 2019, 115(7), 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanze, N.; Bode, C.; Duerschmied, D. Platelet Contributions to Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B. C.; Virmani, R.; Nichols, W. W.; Mehta, J. L. Platelets protect against myocardial dysfunction and injury induced by ischemia and reperfusion in isolated rat hearts. Circ Res 1993, 72(6), 1181–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heindl, B.; Zahler, S.; Welsch, U.; Becker, B. F. Disparate effects of adhesion and degranulation of platelets on myocardial and coronary function in postischaemic hearts. Cardiovasc Res 1998, 38(2), 383–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhri, T. F.; Hoh, B. L.; Zerwes, H. G.; Prestigiacomo, C. J.; Kim, S. C.; Connolly, E. S., Jr.; Kottirsch, G.; Pinsky, D. J. Reduced microvascular thrombosis and improved outcome in acute murine stroke by inhibiting GP IIb/IIIa receptor-mediated platelet aggregation. J Clin Invest 1998, 102(7), 1301–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golino, P.; Maroko, P. R.; Carew, T. E. Efficacy of platelet depletion in counteracting the detrimental effect of acute hypercholesterolemia on infarct size and the no-reflow phenomenon in rabbits undergoing coronary artery occlusion-reperfusion. Circulation 1987, 76(1), 173–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, F. J.; Blasini, R.; Schmitt, C.; Alt, E.; Dirschinger, J.; Gawaz, M.; Kastrati, A.; Schomig, A. Effect of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade on recovery of coronary flow and left ventricular function after the placement of coronary-artery stents in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1998, 98(24), 2695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, S. B.; Hernandez-Resendiz, S.; Crespo-Avilan, G. E.; Mukhametshina, R. T.; Kwek, X. Y.; Cabrera-Fuentes, H. A.; Hausenloy, D. J. Inflammation following acute myocardial infarction: Multiple players, dynamic roles, and novel therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol Ther 2018, 186, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotz, A. K.; Zahler, S.; Stumpf, P.; Welsch, U.; Becker, B. F. Intracoronary formation and retention of micro aggregates of leukocytes and platelets contribute to postischemic myocardial dysfunction. Basic Res Cardiol 2005, 100(5), 413–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, L.; Zhou, X.; Ji, W. J.; Lu, R. Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. D.; Ma, Y. Q.; Zhao, J. H.; Li, Y. M. Neutrophil extracellular traps in ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced myocardial no-reflow: therapeutic potential of DNase-based reperfusion strategy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2015, 308(5), H500–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeschke, H.; Smith, C. W. Mechanisms of neutrophil-induced parenchymal cell injury. J Leukoc Biol 1997, 61(6), 647–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndrepepa, G. Myeloperoxidase - A bridge linking inflammation and oxidative stress with cardiovascular disease. Clin Chim Acta 2019, 493, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanic, A. M.; Harrison, S. M.; Bao, W.; Burns-Kurtis, C. L.; Pickering, S.; Gu, J.; Grau, E.; Mao, J.; Sathe, G. M.; Ohlstein, E. H.; Yue, T. L. Myocardial protection from ischemia/reperfusion injury by targeted deletion of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Cardiovasc Res 2002, 54(3), 549–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsey, M.; Wedin, K.; Brown, M. D.; Keller, C.; Evans, A. J.; Smolen, J.; Burns, A. R.; Rossen, R. D.; Michael, L.; Entman, M. Matrix-dependent mechanism of neutrophil-mediated release and activation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation 2001, 103(17), 2181–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nees, S.; Weiss, D. R.; Senftl, A.; Knott, M.; Forch, S.; Schnurr, M.; Weyrich, P.; Juchem, G. Isolation, bulk cultivation, and characterization of coronary microvascular pericytes: the second most frequent myocardial cell type in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2012, 302(1), H69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Farrell, F. M.; Mastitskaya, S.; Hammond-Haley, M.; Freitas, F.; Wah, W. R.; Attwell, D. Capillary pericytes mediate coronary no-reflow after myocardial ischaemia. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. N.; Reynell, C.; Gesslein, B.; Hamilton, N. B.; Mishra, A.; Sutherland, B. A.; O'Farrell, F. M.; Buchan, A. M.; Lauritzen, M.; Attwell, D. Capillary pericytes regulate cerebral blood flow in health and disease. Nature 2014, 508(7494), 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemisci, M.; Gursoy-Ozdemir, Y.; Vural, A.; Can, A.; Topalkara, K.; Dalkara, T. Pericyte contraction induced by oxidative-nitrative stress impairs capillary reflow despite successful opening of an occluded cerebral artery. Nat Med 2009, 15(9), 1031–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M. A.; Paiva, A. E.; Andreotti, J. P.; Cardoso, M. V.; Cardoso, C. D.; Mintz, A.; Birbrair, A. Pericytes constrict blood vessels after myocardial ischemia. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2018, 116, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methner, C.; Cao, Z.; Mishra, A.; Kaul, S. Mechanism and potential treatment of the "no reflow" phenomenon after acute myocardial infarction: role of pericytes and GPR39. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2021, 321(6), H1030–H1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Guo, Z.; Wu, C.; Tu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xie, E.; Yu, C.; Sun, W.; Li, X.; Zheng, J.; Gao, Y. Ischemia preconditioning alleviates ischemia/reperfusion injury-induced coronary no-reflow and contraction of microvascular pericytes in rats. Microvasc Res 2022, 142, 104349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canty, J. M., Jr.; Klocke, F. J. Reduced regional myocardial perfusion in the presence of pharmacologic vasodilator reserve. Circulation 1985, 71(2), 370–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanBenthuysen, K. M.; McMurtry, I. F.; Horwitz, L. D. Reperfusion after acute coronary occlusion in dogs impairs endothelium-dependent relaxation to acetylcholine and augments contractile reactivity in vitro. J Clin Invest 1987, 79(1), 265–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillen, J. E.; Sellke, F. W.; Brooks, L. A.; Harrison, D. G. Ischemia-reperfusion impairs endothelium-dependent relaxation of coronary microvessels but does not affect large arteries. Circulation 1990, 82(2), 586–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malliani, A.; Schwartz, P. J.; Zanchetti, A. A sympathetic reflex elicited by experimental coronary occlusion. Am J Physiol 1969, 217(3), 703–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorini, L.; Marco, J.; Kozakova, M.; Palombo, C.; Anguissola, G. B.; Marco, I.; Bernies, M.; Cassagneau, B.; Distante, A.; Bossi, I. M.; Fajadet, J.; Heusch, G. Alpha-adrenergic blockade improves recovery of myocardial perfusion and function after coronary stenting in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1999, 99(4), 482–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.; Wang, Q. D.; Sjoquist, P. O.; Ryden, L. The angiotensin II AT1-receptor antagonist candesartan improves functional recovery and reduces the no-reflow area in reperfused ischemic rat hearts. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1999, 34(1), 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryckwaert, F.; Colson, P.; Guillon, G.; Foex, P. Cumulative effects of AT1 and AT2 receptor blockade on ischaemia-reperfusion recovery in rat hearts. Pharmacol Res 2005, 51(6), 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhang, H.; Belmadani, S.; Wu, J.; Xu, X.; Elford, H.; Potter, B. J.; Zhang, C. Role of TNF-alpha-induced reactive oxygen species in endothelial dysfunction during reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2008, 295(6), H2242–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinbongard, P.; Bose, D.; Baars, T.; Mohlenkamp, S.; Konorza, T.; Schoner, S.; Elter-Schulz, M.; Eggebrecht, H.; Degen, H.; Haude, M.; Levkau, B.; Schulz, R.; Erbel, R.; Heusch, G. Vasoconstrictor potential of coronary aspirate from patients undergoing stenting of saphenous vein aortocoronary bypass grafts and its pharmacological attenuation. Circ Res 2011, 108(3), 344–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinbongard, P.; Baars, T.; Mohlenkamp, S.; Kahlert, P.; Erbel, R.; Heusch, G. Aspirate from human stented native coronary arteries vs. saphenous vein grafts: more endothelin but less particulate debris. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013, 305(8), H1222-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herring, N.; Tapoulal, N.; Kalla, M.; Ye, X.; Borysova, L.; Lee, R.; Dall'Armellina, E.; Stanley, C.; Ascione, R.; Lu, C. J.; Banning, A. P.; Choudhury, R. P.; Neubauer, S.; Dora, K.; Kharbanda, R. K.; Channon, K. M.; Oxford Acute Myocardial Infarction, S. Neuropeptide-Y causes coronary microvascular constriction and is associated with reduced ejection fraction following ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2019, 40(24), 1920–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H. M.; He, G. W.; Huang, J. H.; Yang, Q. New strategy of endothelial protection in cardiac surgery: use of enhancer of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. World J Surg 2010, 34(7), 1461–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, D. N.; Kvietys, P. R. Reperfusion injury and reactive oxygen species: The evolution of a concept. Redox Biol 2015, 6, 524–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hein, T. W.; Zhang, C.; Wang, W.; Chang, C. I.; Thengchaisri, N.; Kuo, L. Ischemia-reperfusion selectively impairs nitric oxide-mediated dilation in coronary arterioles: counteracting role of arginase. FASEB J 2003, 17(15), 2328–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreckenberg, R.; Weber, P.; Cabrera-Fuentes, H. A.; Steinert, I.; Preissner, K. T.; Bencsik, P.; Sarkozy, M.; Csonka, C.; Ferdinandy, P.; Schulz, R.; Schluter, K. D. Mechanism and consequences of the shift in cardiac arginine metabolism following ischaemia and reperfusion in rats. Thromb Haemost 2015, 113(3), 482–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Chuang, C. C.; Zuo, L. Molecular Characterization of Reactive Oxygen Species in Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 864946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viehman, G. E.; Ma, X. L.; Lefer, D. J.; Lefer, A. M. Time course of endothelial dysfunction and myocardial injury during coronary arterial occlusion. Am J Physiol 1991, 261 (3 Pt 2), H874–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, M. R.; de Waard, G. A.; Konijnenberg, L. S.; Meijer-van Putten, R. M.; van den Brom, C. E.; Paauw, N.; de Vries, H. E.; van de Ven, P. M.; Aman, J.; Van Nieuw-Amerongen, G. P.; Hordijk, P. L.; Niessen, H. W.; Horrevoets, A. J.; Van Royen, N. Dissecting the Effects of Ischemia and Reperfusion on the Coronary Microcirculation in a Rat Model of Acute Myocardial Infarction. PLoS One 2016, 11(7), e0157233. [Google Scholar]

- Gavin, J. B.; Seelye, R. N.; Nevalainen, T. J.; Armiger, L. C. The effect of ischaemia on the function and fine structure of the microvasculature of myocardium. Pathology 1978, 10(2), 103–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonborg, J.; Kelbaek, H.; Helqvist, S.; Holmvang, L.; Jorgensen, E.; Saunamaki, K.; Klovgaard, L.; Kaltoft, A.; Botker, H. E.; Lassen, J. F.; Thuesen, L.; Terkelsen, C. J.; Kofoed, K. F.; Clemmensen, P.; Kober, L.; Engstrom, T. The impact of distal embolization and distal protection on long-term outcome in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction randomized to primary percutaneous coronary intervention--results from a randomized study. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2015, 4(2), 180–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napodano, M.; Peluso, D.; Marra, M. P.; Frigo, A. C.; Tarantini, G.; Buja, P.; Gasparetto, V.; Fraccaro, C.; Isabella, G.; Razzolini, R.; Iliceto, S. Time-dependent detrimental effects of distal embolization on myocardium and microvasculature during primary percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2012, 5(11), 1170–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriques, J. P.; Zijlstra, F.; Ottervanger, J. P.; de Boer, M. J.; van 't Hof, A. W.; Hoorntje, J. C.; Suryapranata, H. Incidence and clinical significance of distal embolization during primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2002, 23(14), 1112–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yameogo, N. V.; Guenancia, C.; Porot, G.; Stamboul, K.; Richard, C.; Gudjoncik, A.; Hamblin, J.; Buffet, P.; Lorgis, L.; Cottin, Y. Predictors of angiographically visible distal embolization in STEMI. Herz 2020, 45(3), 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G. W.; Webb, J.; Cox, D. A.; Brodie, B. R.; Qureshi, M.; Kalynych, A.; Turco, M.; Schultheiss, H. P.; Dulas, D.; Rutherford, B. D.; Antoniucci, D.; Krucoff, M. W.; Gibbons, R. J.; Jones, D.; Lansky, A. J.; Mehran, R.; Enhanced Myocardial, E.; Recovery by Aspiration of Liberated Debris, I. Distal microcirculatory protection during percutaneous coronary intervention in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005, 293(9), 1063–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinbongard, P.; Heusch, G. A fresh look at coronary microembolization. Nat Rev Cardiol 2022, 19(4), 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunoki, K.; Naruko, T.; Inoue, T.; Sugioka, K.; Inaba, M.; Iwasa, Y.; Komatsu, R.; Itoh, A.; Haze, K.; Yoshiyama, M.; Becker, A. E.; Ueda, M. Relationship of thrombus characteristics to the incidence of angiographically visible distal embolization in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with thrombus aspiration. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2013, 6(4), 377–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abela, G. S.; Kalavakunta, J. K.; Janoudi, A.; Leffler, D.; Dhar, G.; Salehi, N.; Cohn, J.; Shah, I.; Karve, M.; Kotaru, V. P. K.; Gupta, V.; David, S.; Narisetty, K. K.; Rich, M.; Vanderberg, A.; Pathak, D. R.; Shamoun, F. E. Frequency of Cholesterol Crystals in Culprit Coronary Artery Aspirate During Acute Myocardial Infarction and Their Relation to Inflammation and Myocardial Injury. Am J Cardiol 2017, 120(10), 1699–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, Y.; Taruya, A.; Kashiwagi, M.; Ozaki, Y.; Shiono, Y.; Tanimoto, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Kondo, T.; Tanaka, A. No-reflow phenomenon and in vivo cholesterol crystals combined with lipid core in acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2022, 38, 100953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, R.; Oshima, S.; Jingu, M.; Tsurugaya, H.; Toyama, T.; Hoshizaki, H.; Taniguchi, K. Usefulness of virtual histology intravascular ultrasound to predict distal embolization for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007, 50(17), 1641–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napodano, M.; Ramondo, A.; Tarantini, G.; Peluso, D.; Compagno, S.; Fraccaro, C.; Frigo, A. C.; Razzolini, R.; Iliceto, S. Predictors and time-related impact of distal embolization during primary angioplasty. Eur Heart J 2009, 30(3), 305–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokkema, M. L.; Vlaar, P. J.; Svilaas, T.; Vogelzang, M.; Amo, D.; Diercks, G. F.; Suurmeijer, A. J.; Zijlstra, F. Incidence and clinical consequences of distal embolization on the coronary angiogram after percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2009, 30(8), 908–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, E.; Thuesen, L. Pathology of coronary microembolisation and no reflow. Heart 2003, 89(9), 983–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skyschally, A.; Walter, B.; Heusch, G. Coronary microembolization during early reperfusion: infarct extension, but protection by ischaemic postconditioning. Eur Heart J 2013, 34(42), 3314–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, M.; Martin, A. J.; Ursell, P. C.; Saloner, D.; Saeed, M. Magnetic resonance imaging quantification of left ventricular dysfunction following coronary microembolization. Magn Reson Med 2009, 61(3), 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, B.; Vaidya, K.; Cochran, B. J.; Patel, S. Inflammation during Percutaneous Coronary Intervention-Prognostic Value, Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Cells 2021, 10(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinones, A.; Saric, M. The cholesterol emboli syndrome in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2013, 15(4), 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R. M.; Lim, S. Y.; Qiang, B.; Osherov, A. B.; Ghugre, N. R.; Noyan, H.; Qi, X.; Wolff, R.; Ladouceur-Wodzak, M.; Berk, T. A.; Butany, J.; Husain, M.; Wright, G. A.; Strauss, B. H. Distal coronary embolization following acute myocardial infarction increases early infarct size and late left ventricular wall thinning in a porcine model. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2015, 17, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, R. B.; Sommers, H. M.; Smyth, G. A.; Flack, H. A.; Linn, H. Myocardial necrosis induced by temporary occlusion of a coronary artery in the dog. Arch Pathol 1960, 70, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hausenloy, D. J.; Yellon, D. M. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: a neglected therapeutic target. J Clin Invest 2013, 123(1), 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohlich, G. M.; Meier, P.; White, S. K.; Yellon, D. M.; Hausenloy, D. J. Myocardial reperfusion injury: looking beyond primary PCI. Eur Heart J 2013, 34(23), 1714–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloner, R. A.; Alker, K. J. The Effect of Streptokinase on Intramyocardial Hemorrhage, Infarct Size, and the No-Reflow Phenomenon during Coronary Reperfusion. Circulation 1984, 70(3), 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndrepepa, G.; Tiroch, K.; Keta, D.; Fusaro, M.; Seyfarth, M.; Pache, J.; Mehilli, J.; Schoemig, A.; Kastrati, A. Predictive Factors and Impact of No Reflow After Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circ-Cardiovasc Inte 2010, 3(1), 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloner, R. A.; Rude, R. E.; Carlson, N.; Maroko, P. R.; DeBoer, L. W.; Braunwald, E. Ultrastructural evidence of microvascular damage and myocardial cell injury after coronary artery occlusion: which comes first? Circulation 1980, 62(5), 945–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloner, R. A.; King, K. S.; Harrington, M. G. No-reflow phenomenon in the heart and brain. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2018, 315(3), H550–H562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosio, G.; Weisman, H. F.; Mannisi, J. A.; Becker, L. C. Progressive impairment of regional myocardial perfusion after initial restoration of postischemic blood flow. Circulation 1989, 80(6), 1846–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochitte, C. E.; Lima, J. A.; Bluemke, D. A.; Reeder, S. B.; McVeigh, E. R.; Furuta, T.; Becker, L. C.; Melin, J. A. Magnitude and time course of microvascular obstruction and tissue injury after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1998, 98(10), 1006–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reffelmann, T.; Kloner, R. A. Microvascular reperfusion injury: rapid expansion of anatomic no reflow during reperfusion in the rabbit. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2002, 283(3), H1099–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turschner, O.; D'Hooge, J.; Dommke, C.; Claus, P.; Verbeken, E.; De Scheerder, I.; Bijnens, B.; Sutherland, G. R. The sequential changes in myocardial thickness and thickening which occur during acute transmural infarction, infarct reperfusion and the resultant expression of reperfusion injury. Eur Heart J 2004, 25(9), 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Jimenez, R.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, J.; Aguero, J.; Garcia-Prieto, J.; Lopez-Martin, G. J.; Garcia-Ruiz, J. M.; Molina-Iracheta, A.; Rossello, X.; Fernandez-Friera, L.; Pizarro, G.; Garcia-Alvarez, A.; Dall'Armellina, E.; Macaya, C.; Choudhury, R. P.; Fuster, V.; Ibanez, B. Myocardial edema after ischemia/reperfusion is not stable and follows a bimodal pattern: imaging and histological tissue characterization. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015, 65(4), 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalil, M.; Borlotti, A.; De Maria, G. L.; Gaughran, L.; Langrish, J.; Lucking, A.; Ferreira, V.; Kharbanda, R. K.; Banning, A. P.; Channon, K. M.; Dall'Armellina, E.; Choudhury, R. P. Dynamic changes in injured myocardium, very early after acute myocardial infarction, quantified using T1 mapping cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2018, 20(1), 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Jimenez, R.; Barreiro-Perez, M.; Martin-Garcia, A.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, J.; Aguero, J.; Galan-Arriola, C.; Garcia-Prieto, J.; Diaz-Pelaez, E.; Vara, P.; Martinez, I.; Zamarro, I.; Garde, B.; Sanz, J.; Fuster, V.; Sanchez, P. L.; Ibanez, B. Dynamic Edematous Response of the Human Heart to Myocardial Infarction: Implications for Assessing Myocardial Area at Risk and Salvage. Circulation 2017, 136(14), 1288–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veinot, J. P.; Gattinger, D. A.; Fliss, H. Early apoptosis in human myocardial infarcts. Hum Pathol 1997, 28(4), 485–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausenloy, D. J.; Candilio, L.; Evans, R.; Ariti, C.; Jenkins, D. P.; Kolvekar, S.; Knight, R.; Kunst, G.; Laing, C.; Nicholas, J.; Pepper, J.; Robertson, S.; Xenou, M.; Clayton, T.; Yellon, D. M.; Investigators, E. T. Remote Ischemic Preconditioning and Outcomes of Cardiac Surgery. N Engl J Med 2015, 373(15), 1408–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbate, A.; Bussani, R.; Biondi-Zoccai, G. G.; Rossiello, R.; Silvestri, F.; Baldi, F.; Biasucci, L. M.; Baldi, A. Persistent infarct-related artery occlusion is associated with an increased myocardial apoptosis at postmortem examination in humans late after an acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2002, 106(9), 1051–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidambi, A.; Mather, A. N.; Motwani, M.; Swoboda, P.; Uddin, A.; Greenwood, J. P.; Plein, S. The effect of microvascular obstruction and intramyocardial hemorrhage on contractile recovery in reperfused myocardial infarction: insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2013, 15(1), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandler, D.; Lucke, C.; Grothoff, M.; Andres, C.; Lehmkuhl, L.; Nitzsche, S.; Riese, F.; Mende, M.; de Waha, S.; Desch, S.; Lurz, P.; Eitel, I.; Gutberlet, M. The relation between hypointense core, microvascular obstruction and intramyocardial haemorrhage in acute reperfused myocardial infarction assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Radiol 2014, 24(12), 3277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginson, L. A.; White, F.; Heggtveit, H. A.; Sanders, T. M.; Bloor, C. M.; Covell, J. W. Determinants of myocardial hemorrhage after coronary reperfusion in the anesthetized dog. Circulation 1982, 65(1), 62–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathey, D. G.; Schofer, J.; Kuck, K. H.; Beil, U.; Kloppel, G. Transmural, haemorrhagic myocardial infarction after intracoronary streptokinase. Clinical, angiographic, and necropsy findings. Br Heart J 1982, 48(6), 546–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, J. J.; Lacro, R. V.; Yee, M.; Smith, G. T. Hemorrhagic infarction and coronary reperfusion. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1981, 81(4), 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotan, C. S.; Bouchard, A.; Cranney, G. B.; Bishop, S. P.; Pohost, G. M. Assessment of postreperfusion myocardial hemorrhage using proton NMR imaging at 1.5 T. Circulation 1992, 86(3), 1018–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, R. H.; Zeng, M.; Adamson, G. N.; Lenz, J. F.; Curry, F. E. PAF- and bradykinin-induced hyperpermeability of rat venules is independent of actin-myosin contraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2003, 285(1), H406–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inauen, W.; Granger, D. N.; Meininger, C. J.; Schelling, M. E.; Granger, H. J.; Kvietys, P. R. Anoxia-reoxygenation-induced, neutrophil-mediated endothelial cell injury: role of elastase. Am J Physiol 1990, 259 (3 Pt 2), H925–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A. K.; Joshi, M. B.; Philippova, M.; Erne, P.; Hasler, P.; Hahn, S.; Resink, T. J. Activated endothelial cells induce neutrophil extracellular traps and are susceptible to NETosis-mediated cell death. FEBS Lett 2010, 584(14), 3193–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarikuz Zaman, A. K.; Spees, J. L.; Sobel, B. E. Attenuation of cardiac vascular rhexis: a promising therapeutic target. Coron Artery Dis 2013, 24(3), 245–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeman, A. K. M. T.; French, C. J.; Spees, J. L.; Binbrek, A. S.; Sobel, B. E. Vascular rhexis in mice subjected to non-sustained myocardial ischemia and its therapeutic implications. Exp Biol Med 2011, 236(5), 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbers, L. F.; Eerenberg, E. S.; Teunissen, P. F.; Jansen, M. F.; Hollander, M. R.; Horrevoets, A. J.; Knaapen, P.; Nijveldt, R.; Heymans, M. W.; Levi, M. M.; van Rossum, A. C.; Niessen, H. W.; Marcu, C. B.; Beek, A. M.; van Royen, N. Magnetic resonance imaging-defined areas of microvascular obstruction after acute myocardial infarction represent microvascular destruction and haemorrhage. Eur Heart J 2013, 34(30), 2346–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrick, D.; Haig, C.; Ahmed, N.; McEntegart, M.; Petrie, M. C.; Eteiba, H.; Hood, S.; Watkins, S.; Lindsay, M. M.; Davie, A.; Mahrous, A.; Mordi, I.; Rauhalammi, S.; Sattar, N.; Welsh, P.; Radjenovic, A.; Ford, I.; Oldroyd, K. G.; Berry, C. Myocardial Hemorrhage After Acute Reperfused ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Relation to Microvascular Obstruction and Prognostic Significance. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2016, 9(1), e004148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulluck, H.; Rosmini, S.; Abdel-Gadir, A.; White, S. K.; Bhuva, A. N.; Treibel, T. A.; Fontana, M.; Ramlall, M.; Hamarneh, A.; Sirker, A.; Herrey, A. S.; Manisty, C.; Yellon, D. M.; Kellman, P.; Moon, J. C.; Hausenloy, D. J. Residual Myocardial Iron Following Intramyocardial Hemorrhage During the Convalescent Phase of Reperfused ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Adverse Left Ventricular Remodeling. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2016, 9(10), e004940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kali, A.; Kumar, A.; Cokic, I.; Tang, R. L.; Tsaftaris, S. A.; Friedrich, M. G.; Dharmakumar, R. Chronic manifestation of postreperfusion intramyocardial hemorrhage as regional iron deposition: a cardiovascular magnetic resonance study with ex vivo validation. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2013, 6(2), 218–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, B. F.; Rothbaum, D. A.; Pinkerton, C. A.; Cowley, M. J.; Linnemeier, T. J.; Orr, C.; Irons, M.; Helmuth, R. A.; Wills, E. R.; Aust, C. Status of the myocardium and infarct-related coronary artery in 19 necropsy patients with acute recanalization using pharmacologic (streptokinase, r-tissue plasminogen activator), mechanical (percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty) or combined types of reperfusion therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1987, 9(4), 785–801. [Google Scholar]

- Amier, R. P.; Tijssen, R. Y. G.; Teunissen, P. F. A.; Fernandez-Jimenez, R.; Pizarro, G.; Garcia-Lunar, I.; Bastante, T.; van de Ven, P. M.; Beek, A. M.; Smulders, M. W.; Bekkers, S.; van Royen, N.; Ibanez, B.; Nijveldt, R. Predictors of Intramyocardial Hemorrhage After Reperfused ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J Am Heart Assoc 2017, 6(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Howarth, A. G.; Chen, Y.; Nair, A. R.; Yang, H. J.; Ren, D.; Tang, R.; Sykes, J.; Kovacs, M. S.; Dey, D.; Slomka, P.; Wood, J. C.; Finney, R.; Zeng, M.; Prato, F. S.; Francis, J.; Berman, D. S.; Shah, P. K.; Kumar, A.; Dharmakumar, R. Intramyocardial Hemorrhage and the "Wave Front" of Reperfusion Injury Compromising Myocardial Salvage. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022, 79(1), 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K. C.; Zerhouni, E. A.; Judd, R. M.; Lugo-Olivieri, C. H.; Barouch, L. A.; Schulman, S. P.; Blumenthal, R. S.; Lima, J. A. Prognostic significance of microvascular obstruction by magnetic resonance imaging in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1998, 97(8), 765–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloner, R. A.; Giacomelli, F.; Alker, K. J.; Hale, S. L.; Matthews, R.; Bellows, S. Influx of neutrophils into the walls of large epicardial coronary arteries in response to ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation 1991, 84(4), 1758–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, P. R. Role of neutrophils in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Circulation 1995, 91(6), 1872–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toldo, S.; Abbate, A. The NLRP3 inflammasome in acute myocardial infarction. Nat Rev Cardiol 2018, 15(4), 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montone, R. A.; La Vecchia, G. Interplay between inflammation and microvascular obstruction in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: The importance of velocity. Int J Cardiol 2021, 339, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, A.; Klug, G.; Schocke, M.; Trieb, T.; Mair, J.; Pedarnig, K.; Pachinger, O.; Jaschke, W.; Metzler, B. Late microvascular obstruction after acute myocardial infarction: relation with cardiac and inflammatory markers. Int J Cardiol 2012, 157(3), 391–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reindl, M.; Reinstadler, S. J.; Feistritzer, H. J.; Klug, G.; Tiller, C.; Mair, J.; Mayr, A.; Jaschke, W.; Metzler, B. Relation of inflammatory markers with myocardial and microvascular injury in patients with reperfused ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2017, 6(7), 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Dong, M.; Ren, F.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Tao, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, G. Association between local interleukin-6 levels and slow flow/microvascular dysfunction. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2014, 37(4), 475–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetelig, C.; Limalanathan, S.; Hoffmann, P.; Seljeflot, I.; Gran, J. M.; Eritsland, J.; Andersen, G. O. Association of IL-8 With Infarct Size and Clinical Outcomes in Patients With STEMI. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018, 72(2), 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funayama, H.; Ishikawa, S. E.; Sugawara, Y.; Kubo, N.; Momomura, S.; Kawakami, M. Myeloperoxidase may contribute to the no-reflow phenomenon in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2010, 139(2), 187–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamboul, K.; Zeller, M.; Rochette, L.; Cottin, Y.; Cochet, A.; Leclercq, T.; Porot, G.; Guenancia, C.; Fichot, M.; Maillot, N.; Vergely, C.; Lorgis, L. Relation between high levels of myeloperoxidase in the culprit artery and microvascular obstruction, infarct size and reverse remodeling in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Plos One 2017, 12(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reffelmann, T.; Hale, S. L.; Li, G.; Kloner, R. A. Relationship between no reflow and infarct size as influenced by the duration of ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2002, 282(2), H766–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouleti, C.; Mathivet, T.; Serfaty, J. M.; Vignolles, N.; Berland, E.; Monnot, C.; Cluzel, P.; Steg, P. G.; Montalescot, G.; Germain, S. Angiopoietin-like 4 serum levels on admission for acute myocardial infarction are associated with no-reflow. International Journal of Cardiology 2015, 187, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niccoli, G.; Lanza, G. A.; Shaw, S.; Romagnoli, E.; Gioia, D.; Burzotta, F.; Trani, C.; Mazzari, M. A.; Mongiardo, R.; De Vita, M.; Rebuzzi, A. G.; Luscher, T. F.; Crea, F. Endothelin-1 and acute myocardial infarction: a no-reflow mediator after successful percutaneous myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J 2006, 27(15), 1793–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nallamothu, B. K.; Bradley, E. H.; Krumholz, H. M. Time to treatment in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med 2007, 357(16), 1631–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, A.; Camici, P. G. Novel insights into an "old" phenomenon: the no reflow. Int J Cardiol 2015, 187, 273–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niccoli, G.; Scalone, G.; Lerman, A.; Crea, F. Coronary microvascular obstruction in acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2016, 37(13), 1024–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorop, O.; Merkus, D.; de Beer, V. J.; Houweling, B.; Pistea, A.; McFalls, E. O.; Boomsma, F.; van Beusekom, H. M.; van der Giessen, W. J.; VanBavel, E.; Duncker, D. J. Functional and structural adaptations of coronary microvessels distal to a chronic coronary artery stenosis. Circ Res 2008, 102(7), 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, K.; Tucker, B.; Patel, S.; Ng, M. K. C. Acute Coronary Syndromes (ACS)-Unravelling Biology to Identify New Therapies-The Microcirculation as a Frontier for New Therapies in ACS. Cells 2021, 10(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, A.; Holmes, D. R.; Herrmann, J.; Gersh, B. J. Microcirculatory dysfunction in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: cause, consequence, or both? Eur Heart J 2007, 28(7), 788–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, M. K.; Yong, A. S.; Ho, M.; Shah, M. G.; Chawantanpipat, C.; O'Connell, R.; Keech, A.; Kritharides, L.; Fearon, W. F. The index of microcirculatory resistance predicts myocardial infarction related to percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2012, 5(4), 515–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeda, T.; Higuma, T.; Abe, N.; Yamada, M.; Yokoyama, H.; Shibutani, S.; Ong, D. S.; Vergallo, R.; Minami, Y.; Lee, H.; Okumura, K.; Jang, I. K. Morphological predictors for no reflow phenomenon after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction caused by plaque rupture. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2017, 18(1), 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, P.; Rekwal, L.; Sinha, S. K.; Nath, R. K.; Khanra, D.; Singh, A. P. Predictors of no-reflow phenomenon following percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris) 2021, 70(3), 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Kawarabayashi, T.; Nishibori, Y.; Sano, T.; Nishida, Y.; Fukuda, D.; Shimada, K.; Yoshikawa, J. No-reflow phenomenon and lesion morphology in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2002, 105(18), 2148–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, H. K.; Chen, M. C.; Chang, H. W.; Hang, C. L.; Hsieh, Y. K.; Fang, C. Y.; Wu, C. J. Angiographic morphologic features of infarct-related arteries and timely reperfusion in acute myocardial infarction: predictors of slow-flow and no-reflow phenomenon. Chest 2002, 122(4), 1322–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehran, R.; Dangas, G.; Mintz, G. S.; Lansky, A. J.; Pichard, A. D.; Satler, L. F.; Kent, K. M.; Stone, G. W.; Leon, M. B. Atherosclerotic plaque burden and CK-MB enzyme elevation after coronary interventions : intravascular ultrasound study of 2256 patients. Circulation 2000, 101(6), 604–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magro, M.; Nauta, S. T.; Simsek, C.; Boersma, E.; van der Heide, E.; Regar, E.; van Domburg, R. T.; Zijlstra, F.; Serruys, P. W.; van Geuns, R. J. Usefulness of the SYNTAX score to predict "no reflow" in patients treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2012, 109(5), 601–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Baghdasaryan, P.; Natarajan, B.; Sethi, P.; Mukherjee, A.; Varadarajan, P.; Pai, R. G. Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Coronary No-Reflow Phenomenon. Int J Angiol 2021, 30(1), 15–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harrison, R. W.; Aggarwal, A.; Ou, F. S.; Klein, L. W.; Rumsfeld, J. S.; Roe, M. T.; Wang, T. Y. ; American College of Cardiology National Cardiovascular Data, R., Incidence and outcomes of no-reflow phenomenon during percutaneous coronary intervention among patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2013, 111(2), 178–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galiuto, L.; Paraggio, L.; Liuzzo, G.; de Caterina, A. R.; Crea, F. Predicting the no-reflow phenomenon following successful percutaneous coronary intervention. Biomark Med 2010, 4(3), 403–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Li, G.; Zhou, Y.; Dong, H. Elevated uric acid is related to the no-/slow-reflow phenomenon in STEMI undergoing primary PCI. Eur J Clin Invest 2022, 52(4), e13719. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kai, T.; Oka, S.; Hoshino, K.; Watanabe, K.; Nakamura, J.; Abe, M.; Watanabe, A. Renal Dysfunction as a Predictor of Slow-Flow/No-Reflow Phenomenon and Impaired ST Segment Resolution After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction With Initial Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Grade 0. Circ J 2021, 85(10), 1770–1778. [Google Scholar]

- Savic, L.; Mrdovic, I.; Asanin, M.; Stankovic, S.; Lasica, R.; Krljanac, G.; Rajic, D.; Simic, D. The Impact of Kidney Function on the Slow-Flow/No-Reflow Phenomenon in Patients Treated with Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Registry Analysis. J Interv Cardiol 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Esenboga, K.; Kurtul, A.; Yamanturk, Y. Y.; Tan, T. S.; Tutar, D. E. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts no-reflow phenomenon after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Acta Cardiol 2022, 77(1), 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Selcuk, M.; Cinar, T.; Saylik, F.; Demiroz, O.; Yildirim, E. The Association of a PRECISE-DAPT Score With No-Reflow in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Angiology 2022, 73(1), 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, O.; Sen, S. B.; Topuz, A. N.; Topuz, M. Vitamin D level predicts angiographic no-reflow phenomenon after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Biomark Med 2021, 15(15), 1357–1366. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Ren, J.; Li, L.; Wang, C. S.; Yao, H. C. RDW as A Predictor for No-Reflow Phenomenon in DM Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J Clin Med, 2023; 12, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sondergaard, F. T.; Beske, R. P.; Frydland, M.; Moller, J. E.; Helgestad, O. K. L.; Jensen, L. O.; Holmvang, L.; Goetze, J. P.; Engstrom, T.; Hassager, C. Soluble ST2 in plasma is associated with post-procedural no-or-slow reflow after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2023, 12(1), 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, H. A.; Suwaidi, J. A. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2007, 3(6), 853–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murthy, V. L.; Naya, M.; Foster, C. R.; Gaber, M.; Hainer, J.; Klein, J.; Dorbala, S.; Blankstein, R.; Di Carli, M. F. Association between coronary vascular dysfunction and cardiac mortality in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2012, 126(15), 1858–68. [Google Scholar]

- Di Carli, M. F.; Janisse, J.; Grunberger, G.; Ager, J. Role of chronic hyperglycemia in the pathogenesis of coronary microvascular dysfunction in diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003, 41(8), 1387–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rawshani, A.; Rawshani, A.; Gudbjornsdottir, S. Mortality and Cardiovascular Disease in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017, 377(3), 300–301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eitel, I.; Hintze, S.; de Waha, S.; Fuernau, G.; Lurz, P.; Desch, S.; Schuler, G.; Thiele, H. Prognostic Impact of Hyperglycemia in Nondiabetic and Diabetic Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Insights From Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Circ-Cardiovasc Imag 2012, 5(6), 708–718. [Google Scholar]

- Reinstadler, S. J.; Stiermaier, T.; Eitel, C.; Metzler, B.; de Waha, S.; Fuernau, G.; Desch, S.; Thiele, H.; Eitel, I. Relationship between diabetes and ischaemic injury among patients with revascularized ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017, 19(12), 1706–1713. [Google Scholar]

- Iwakura, K.; Ito, H.; Ikushima, M.; Kawano, S.; Okamura, A.; Asano, K.; Kuroda, T.; Tanaka, K.; Masuyama, T.; Hori, M.; Fujii, K. Association between hyperglycemia and the no-reflow phenomenon in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003, 41(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ota, S.; Tanimoto, T.; Orii, M.; Hirata, K.; Shiono, Y.; Shimamura, K.; Matsuo, Y.; Yamano, T.; Ino, Y.; Kitabata, H.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kubo, T.; Tanaka, A.; Imanishi, T.; Akasaka, T. Association between hyperglycemia at admission and microvascular obstruction in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Cardiol 2015, 65(3-4), 272–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jensen, C. J.; Eberle, H. C.; Nassenstein, K.; Schlosser, T.; Farazandeh, M.; Naber, C. K.; Sabin, G. V.; Bruder, O. Impact of hyperglycemia at admission in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction as assessed by contrast-enhanced MRI. Clin Res Cardiol 2011, 100(8), 649–659. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, E. J.; Liu, Z. Q.; Khamaisi, M.; King, G. L.; Klein, R.; Klein, B. E. K.; Hughes, T. M.; Craft, S.; Freedman, B. I.; Bowden, D. W.; Vinik, A. I.; Casellini, C. M. Diabetic Microvascular Disease: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. J Clin Endocr Metab 2017, 102(12), 4343–4410. [Google Scholar]

- Panza, J. A.; Casino, P. R.; Kilcoyne, C. M.; Quyyumi, A. A. Role of Endothelium-Derived Nitric-Oxide in the Abnormal Endothelium-Dependent Vascular Relaxation of Patients with Essential-Hypertension. Circulation 1993, 87(5), 1468–1474. [Google Scholar]

- Carrick, D.; Haig, C.; Maznyczka, A. M.; Carberry, J.; Mangion, K.; Ahmed, N.; May, V. T. Y.; McEntegart, M.; Petrie, M. C.; Eteiba, H.; Lindsay, M.; Hood, S.; Watkins, S.; Davie, A.; Mahrous, A.; Mordi, I.; Ford, I.; Radjenovic, A.; Welsh, P.; Sattar, N.; Wetherall, K.; Oldroyd, K. G.; Berry, C. Hypertension, Microvascular Pathology, and Prognosis After an Acute Myocardial Infarction. Hypertension 2018, 72(3), 720–730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reinstadler, S. J.; Stiermaier, T.; Eitel, C.; Saad, M.; Metzler, B.; de Waha, S.; Fuernau, G.; Desch, S.; Thiele, H.; Eitel, I. Antecedent hypertension and myocardial injury in patients with reperfused ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Magn R 2016, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Quyyumi, A. A.; Mulcahy, D.; Andrews, N. P.; Husain, S.; Panza, J. A.; Cannon, R. O. 3rd, Coronary vascular nitric oxide activity in hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. Comparison of acetylcholine and substance P. Circulation 1997, 95(1), 104–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Golino, P.; Maroko, P. R.; Carew, T. E. The effect of acute hypercholesterolemia on myocardial infarct size and the no-reflow phenomenon during coronary occlusion-reperfusion. Circulation 1987, 75(1), 292–8. [Google Scholar]

- Iwakura, K.; Ito, H.; Kawano, S.; Okamura, A.; Kurotobi, T.; Date, M.; Inoue, K.; Fujii, K. Chronic pre-treatment of statins is associated with the reduction of the no-reflow phenomenon in the patients with reperfused acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2006, 27(5), 534–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reindl, M.; Reinstadler, S. J.; Feistritzer, H. J.; Theurl, M.; Basic, D.; Eigler, C.; Holzknecht, M.; Mair, J.; Mayr, A.; Klug, G.; Metzler, B. Relation of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol With Microvascular Injury and Clinical Outcome in Revascularized ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J Am Heart Assoc 2017, 6(10). [Google Scholar]

- Surendran, A.; Ismail, U.; Atefi, N.; Bagchi, A. K.; Singal, P. K.; Shah, A.; Aliani, M.; Ravandi, A. Lipidomic Predictors of Coronary No-Reflow. Metabolites 2023, 13(1). [Google Scholar]

- Messner, B.; Bernhard, D. Smoking and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction and early atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014, 34(3), 509–15. [Google Scholar]

- Symons, R.; Masci, P. G.; Francone, M.; Claus, P.; Barison, A.; Carbone, I.; Agati, L.; Galea, N.; Janssens, S.; Bogaert, J. Impact of active smoking on myocardial infarction severity in reperfused ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients: the smoker's paradox revisited. Eur Heart J 2016, 37(36), 2756–2764. [Google Scholar]

- Reinstadler, S. J.; Eitel, C.; Fuernau, G.; de Waha, S.; Desch, S.; Mende, M.; Metzler, B.; Schuler, G.; Thiele, H.; Eitel, I. Association of smoking with myocardial injury and clinical outcome in patients undergoing mechanical reperfusion for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2017, 18(1), 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haig, C.; Carrick, D.; Carberry, J.; Mangion, K.; Maznyczka, A.; Wetherall, K.; McEntegart, M.; Petrie, M. C.; Eteiba, H.; Lindsay, M.; Hood, S.; Watkins, S.; Davie, A.; Mahrous, A.; Mordi, I.; Ahmed, N.; Teng Yue May, V.; Ford, I.; Radjenovic, A.; Welsh, P.; Sattar, N.; Oldroyd, K. G.; Berry, C. Current Smoking and Prognosis After Acute ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: New Pathophysiological Insights. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2019, 12(6), 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipek, G.; Onuk, T.; Karatas, M. B.; Gungor, B.; Osken, A.; Keskin, M.; Oz, A.; Tanik, O.; Hayiroglu, M. I.; Yaka, H. Y.; Ozturk, R.; Bolca, O. CHA2DS2-VASc Score is a Predictor of No-Reflow in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Who Underwent Primary Percutaneous Intervention. Angiology 2016, 67(9), 840–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, M.; Ma, S.; Niu, T. New R(2)-CHA(2)DS(2)-VASc score predicts no-reflow phenomenon and long-term prognosis in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 899739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karila-Cohen, D.; Czitrom, D.; Brochet, E.; Faraggi, M.; Seknadji, P.; Himbert, D.; Juliard, J. M.; Assayag, P.; Steg, P. G. Decreased no-reflow in patients with anterior myocardial infarction and pre-infarction angina. Eur Heart J 1999, 20(23), 1724–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, T.; Anzai, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Asakura, Y.; Ishikawa, S.; Mitamura, H.; Ogawa, S. Absence of preinfarction angina is associated with a risk of no-reflow phenomenon after primary coronary angioplasty for a first anterior wall acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2000, 75(2-3), 253–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewski, J.; Undas, A.; Godlewski, J.; Stepien, E.; Zmudka, K. No-reflow phenomenon after acute myocardial infarction is associated with reduced clot permeability and susceptibility to lysis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007, 27(10), 2258–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolayir, H. A.; Gunes, H.; Kivrak, T.; Sahin, O.; Akaslan, D.; Kurt, R.; Bolayir, A.; Imadoglu, O. The role of SCUBE1 in the pathogenesis of no-reflow phenomenon presenting with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Anatol J Cardiol 2017, 18(2), 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, S.; Cilluffo, R.; Best, P. J.; Atkinson, E. J.; Aoki, T.; Cunningham, J. M.; de Andrade, M.; Choi, B. J.; Lerman, L. O.; Lerman, A. Single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with abnormal coronary microvascular function. Coron Artery Dis 2014, 25(4), 281–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niccoli, G.; Celestini, A.; Calvieri, C.; Cosentino, N.; Falcioni, E.; Carnevale, R.; Nocella, C.; Fracassi, F.; Roberto, M.; Antonazzo, R. P.; Pignatelli, P.; Crea, F.; Violi, F. Patients with microvascular obstruction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention show a gp91phox (NOX2) mediated persistent oxidative stress after reperfusion. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2013, 2(4), 379–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, G.; Schiekofer, S.; D'Anna, C.; Gioia, G. D.; Piccolo, R.; Niglio, T.; Rosa, R. D.; Strisciuglio, T.; Cirillo, P.; Piscione, F.; Trimarco, B. No-reflow phenomenon: pathophysiology, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. A review of the current literature and future perspectives. Angiology 2014, 65(3), 180–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, H.; Maruyama, A.; Iwakura, K.; Takiuchi, S.; Masuyama, T.; Hori, M.; Higashino, Y.; Fujii, K.; Minamino, T. Clinical implications of the 'no reflow' phenomenon. A predictor of complications and left ventricular remodeling in reperfused anterior wall myocardial infarction. Circulation 1996, 93(2), 223–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnic, F. S.; Wainstein, M.; Lee, M. K.; Behrendt, D.; Wainstein, R. V.; Ohno-Machado, L.; Kirshenbaum, J. M.; Rogers, C. D.; Popma, J. J.; Piana, R. No-reflow is an independent predictor of death and myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J 2003, 145(1), 42–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosh, D.; Assali, A. R.; Mager, A.; Porter, A.; Hasdai, D.; Teplitsky, I.; Rechavia, E.; Fuchs, S.; Battler, A.; Kornowski, R. Effect of no-reflow during primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction on six-month mortality. Am J Cardiol 2007, 99(4), 442–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognese, L.; Carrabba, N.; Parodi, G.; Santoro, G. M.; Buonamici, P.; Cerisano, G.; Antoniucci, D. Impact of microvascular dysfunction on left ventricular remodeling and long-term clinical outcome after primary coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2004, 109(9), 1121–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, R. H.; Harjai, K. J.; Boura, J.; Cox, D.; Stone, G. W.; O'Neill, W.; Grines, C. L.; Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction, I. Prognostic significance of transient no-reflow during primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2003, 92(12), 1445–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinnouchi, H.; Sakakura, K.; Wada, H.; Arao, K.; Kubo, N.; Sugawara, Y.; Funayama, H.; Momomura, S.; Ako, J. Transient no reflow following primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart Vessels 2014, 29(4), 429–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T.; Masuda, N.; Nakano, M.; Nakazawa, G.; Shinozaki, N.; Matsukage, T.; Ogata, N.; Yoshimachi, F.; Ikari, Y. Impact of transient or persistent slow flow and adjunctive distal protection on mortality in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Interv Ther 2015, 30(2), 121–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. C.; Cho, J. Y.; Jeong, H. C.; Lee, K. H.; Park, K. H.; Sim, D. S.; Yoon, N. S.; Youn, H. J.; Kim, K. H.; Hong, Y. J.; Park, H. W.; Kim, J. H.; Jeong, M. H.; Cho, J. G.; Park, J. C.; Seung, K. B.; Chang, K.; Ahn, Y. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes of Transient and Persistent No Reflow Phenomena following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Korean Circ J 2016, 46(4), 490–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]