1. Introduction

The human microbiota refers to all the microbial cells present in an individual whereas the microbiome consists of their genetic inheritage [

1]. In general, the microbiota is environment-specific. This is why most studies focus on a single microbiota: the gastrointestinal microbiota, the skin microbiota or others. These microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi, yeast and archaea) are necessary for the physiological state of the organism just as they shape our evolution and phenotype [

2]. Indeed, they have a major influence on the immune system. One individual’s ability to prevail against diseases, infections, environmental changes or maintain homeostasis depends in part on these components [

2]. However, it is only in recent years that the scientific community has deconstructed the dogma advocating that the endometrium is a sterile environment. It has been suggested that, like the digestive system, the uterine cavity contains a microbiome necessary to its physiological state [

3].

Previously focused on the lower female genital tract, research has shown that

Lactobacilli species predominate in the healthy vaginal microbiota of women in reproductive age [

4,

5]. However, it remains unclear whether microbial populations in the vagina persist in the endometrium. Recent studies aim to describe the endometrial microbiota (EM) in order to compare it to the vaginal microbiota and to draw out any specificities [

6]. Sola-Leyva et al. (2021) described the presence in the endometrium of multiple active microorganisms in addition to bacteria such as fungi, viruses and archaea, at 10%, 5% and 0,3% respectively [

7]. Furthermore, several groups have attempted to establish a correlation between the endometrium environment and physiological or pathological conditions, particularly in the field of female infertility [

6,

8]. To name just a few affections, endometriosis and chronic endometritis (CE) are likely to have an impact on pregnancy outcome. In fact, repeated implantation failure (RIF) and recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) seem to be more prevalent amongst women suffering from CE [

9]. These facts enhance the crucial role of immune and microbial health in woman fertility.

However, there is no consensus yet on the sampling or analysis methods used to study or treat microbial cells of the uterine cavity, leading to diverse results and hypotheses [

5,

10]. Future objectives would be, firstly, to validate a compliant protocol for the analysis and sampling of endometrial microbiota before considering it as a therapeutic option for infertile women.

In this review, we aim to present the current hypotheses on the different aspects of the EM and draw possible future applications.

2. Composition of the endometrial microbiota

Population profiles of the female genital tract (FGT) fluctuate over the course of a woman's life, depending on age, ethnicity, sexual activity, health status and other factors [

4,

11,

12]. The development of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has enabled more exhaustive analyses of its composition. A key feature of the EM is its diversity. Numerous studies have shown that the uterus contains fewer bacteria but more various species than the vagina, resulting in high alpha-diversity (a measure of the diversity of a single sample, usually based on the number of different species observed) and a low-biomass microbiome [

13,

14,

15].

Firstly, it has been proved that the phyla present in EM are affected by inflammation [

16]. CE, for example, is mostly caused by common microorganisms such as

Staphylococcus species,

Escherichia coli (E. coli), or even

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which in some developing countries is responsible for a particular phenotype of CE [

9]. Furthermore, the bacteria responsible for acute endometritis are rarely found in chronic endometritis [

9].

Secondly, the microbiome is influenced by the hormonal environment in different ways. The peak of estradiol and the increase in progesterone during the mid-luteal phase are associated with greater microbiota stability in the vagina [

11]. Exogenous progesterone, which can be administered for example as luteal support after a controlled ovarian stimulation (COS), decreases the diversity of

Lactobacillus spp phylotypes and thus modifies the EM [

10,

17]. Moreover, as the menstrual cycle is characterized by hormonal variations, we can assume that it also shapes the EM where an increased microbial population has been observed during the proliferative phase with a high alpha-diversity that decreases amid the menstrual cycle [

7,

18,

19]. Nevertheless, it appears stable during the few days corresponding to the acquisition of endometrial receptivity [

10].

The vaginal microbiome, which does not fluctuate as much as the EM during pregnancy, undergoes changes during delivery [

20,

21]. Indeed, there is a decrease in the abundance of

Lactobacillus whereas a stable or higher proportion of this genus in the vaginal microbiota (VM) has been associated with risks of preterm labor [

20,

21]. McMillan et al. (2015) have even proposed a standard VM composition in pregnant women [

22]. These examples illustrate the dynamic profile of the FGT microbiota and the difficulty of establishing a benchmark regarding its composition.

3. Sampling methods

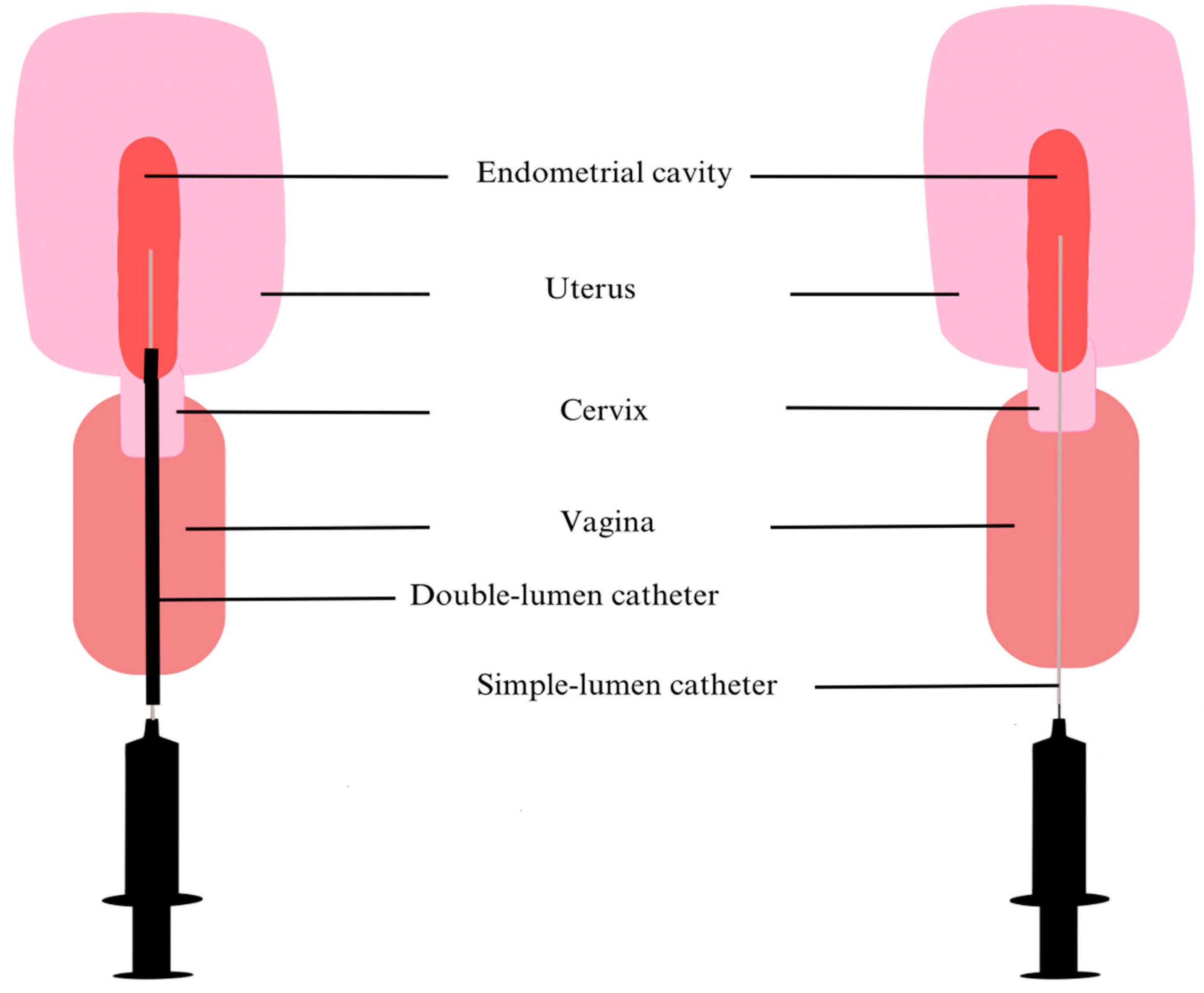

Recognition of an upper genital tract microbiome is relatively recent, and as previously mentioned, there is no consensus yet about sampling and analysis methodologies. Therefore, contamination of samples often risks distorting the clinical results of such research. At the beginning, many endometrial samples were collected as fluids, with a catheter [

23] or a Pipelle [

24] introduced through the cervicovaginal canal and up to 80

µL of endometrial fluid (EF) was aspirated. Some teams first inject 1mL of collection medium to ensure that the sample correctly reflects the uterine environment [

25]. Even if the vagina is cleaned prior to EF collection and the instrument is carefully inserted to avoid contact with the vagina walls, vaginal or cervical contamination is always possible (

Figure 1). This depends mainly on the operator and is therefore not always reproducible.

Consequently, recent researches tend to use double-lumen catheters to prevent any contamination. For instance, Reschini et al. (2022) used a double-lumen catheter (

Figure 1) with a sampling method requiring 3 healthcare professionals (a physician, a biologist and a nurse) [

5]. Before inserting the outer sheath catheter under ultrasound guidance by a nurse, the physician thoroughly cleaned the cervix and vagina with sterile saline solution. The second internal catheter was then inserted into the first. Next, the biologist performed aspiration with a 20mL syringe while the catheter was gradually withdrawn from the cavity, ensuring a more sterile approach [

5]. However, Liu et al. (2018) who compared endometrial biopsy (EB) with EF samples suggest that the latter does not fully illustrate endometrial communities [

26]. Indeed, they highlighted the low number of taxa identified per 1000 sequencing reads in EF, the low assortment and regularity of taxa compared to EB samples and the notable differences in predominant species between the 2 types of samples. However, they recognized that EF bacteria are positively correlated with EB bacteria and suggested that these discrepancies could be related to the attachment or depth of some bacteria to endometrial walls. All things considered, they recommend using EF as complementary information to the EB study [

26]. Moreno et al. (2022) also noted divergences between the constitution of EB and EF [

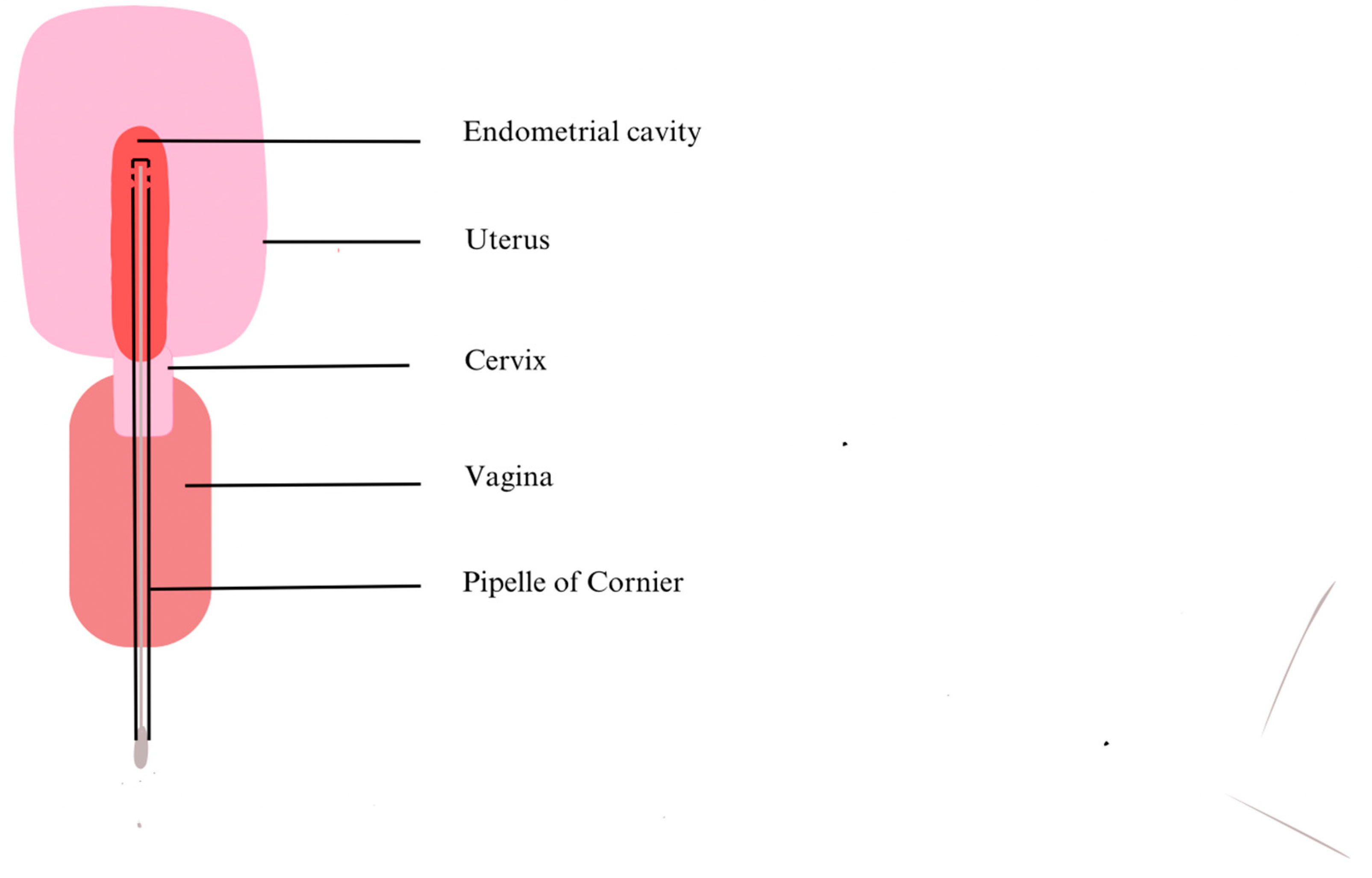

27]. Kitaya et al. (2019) collected EB using a curette so there was nothing to prevent contamination through the vagina or cervix other than the operator’s abilities [

24]. In contrast, Liu et al. (2018) and Moreno et al. (2022) have modified their procedures. They used a Cornier Pipelle which possesses an outer sheath that preserves better sample sterility (

Figure 2) [

26,

27].

The results obtained might also differ according to the DNA extraction kit and the NGS sequencing techniques used. Depending on the hypervariable regions of the bacterial gene encoding the 16S ribosomal subunit chosen to be amplified, or depending on the DNA extraction kits, the liability of the results is at stake. All these circumstances play a major role in the difficulty to assess the EM [

5,

10,

15].

4. Infertility

Already in 1995, Møller et al. attempted to hypothesize the role of microbes within the uterus [

28]. Given that women with distinct EM seem to obtain diverse reproductive outcomes, it is highly expected that the microbial environment of the endometrium influences the pregnancy process [

6]. Recently, scientists have become increasingly interested in investigating whether women with RIF, RPL or clinical miscarriages (CM) may have hostile uterine microbiomes, mostly colonized by pathogens [

27]. Indeed, Moreno et

al. suggest that a

Lactobacillus-dominated (LD) EM increases rates of successful pregnancies in contrast to a non-

Lactobacillus-dominated (NLD) EM [

6,

23]. For example, in this study, patients with a LD-microbiota had higher rates of implantation (60.7% vs 23.1%,

P = .02), pregnancy (70.6% vs 33.3%,

P = .03), ongoing pregnancy (58.8% vs 13.3%,

P = .02), and live birth (58.8% vs 6.7%,

P = .002) [

23]. However, as this genus is mainly found in the vagina where it is responsible for its pH and robustness [

14,

15,

29], some studies associate its abundance in the endometrium with contamination of sampling from the vagina or even pathological conditions. Other findings advocate for specific endometrial bacteria, absent in the vagina, hence representing “biomarkers'' such as

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia or

Kocuria dechangensis [

13,

30]. Although no bacteria have been systematically associated with uterine dysbiosis, there is evidence that treating uterine pathologies of all types increases the chance of pregnancy [

31,

32,

33]. In the future, it would be useful to identify and treat women undergoing IVF treatments who present symptoms or clinical signs of colonization by pathogens.

5. Immunology and Chronic Endometritis

Contrary to popular belief in the medical community, the presence of inflammation in the endometrium is not analogous to pathology. Nevertheless, some recent studies suggest that pregnancy should be considered as a global process in which immunological variations are necessary to ensure successful gestation [

34,

35]. On the one hand, the crucial stages of implantation and placentation require inflammation to allow the trophectoderm to penetrate the endometrial lining [

36,

37]. Indeed Gnainsky et al. (2014) demonstrated that endometrial biopsy enhances its receptivity by attracting inflammatory agents such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, IL-15, CXC-chemokine ligand 1 or osteopontin and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) [

38]. On the other hand, implantation, placentation and subsequent stages also necessitate immunomodulation and tolerance with great involvement of T-regulatory cells. In particular, a lack of tolerance can lead to preeclampsia due to insufficient blood supply to the fetus [

39]. During fetal growth, the environment evolves towards a T-helper type 2 (Th2)/anti-inflammatory milieu for the longest period of pregnancy, with an increased population of macrophages and natural killer (NK) decidual cells. Finally, to activate labor, a pro-inflammatory environment is once again necessary [

36].

However, certain pathologies such as chronic endometritis, have been identified as inflammatory factors that interfere in this process. Firstly, chronic endometritis is defined as a prolonged state of inflammation of the endometrium characterized by the presence of edema, increased stromal cell density and dissociated maturation of the stroma and epithelium throughout the menstrual cycle [

40]. These alterations are capable of causing dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain or even abnormal uterine bleeding, to name a few [

41], and are generally correlated with plasma cell infiltration in the endometrial stroma area (ESPC). Here again, neither the diagnostic criteria nor the methods are clearly established but, as mentioned above, most studies associate this pathology with ESPC which is detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining. This technique searches for the transmembrane heparan sulfate proteoglycan syndecan 1 (CD138) which is a well-known marker of the ESPC. Bouet et al. (2016) conducted a study in which they combined office hysteroscopy with IHC to improve the diagnosis of CE and found that office hysteroscopy is an interesting tool but cannot be used exclusively for this indication [

41]. Like other studies, they identified a higher prevalence of CE in women suffering from RPL and RIF or encountering obstacles to achieve a successful pregnancy, demonstrating that excessive inflammation leads to infertility [

9,

41,

42]. There is no single bacterium attributed to the genesis of CE; those detected may be common or pathological bacteria, which therefore cause dysbiosis of the EM and lesions. For example,

E. coli, Mycoplasma/Ureaplasma species

, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Gardnerella vaginalis or

Corynebacterium have already been involved [

36]. The reported microbiota cannot be assimilated to non-CE EM or to any other suggested healthy composition (LD or NLD) [

34] and above all show significant signs of inflammation. Although there is no international recommendation for treatment yet, oral antibiotic therapy is commonly used and has been shown to be effective in eliminating ESPC [

36]. It is therefore essential to take into account the immunological and inflammatory aspects of the endometrium and its microbiota during infertility assessments.

6. Endometriosis

In recent years, there has been growing evidence that microbial colonization of the endometrium has an impact on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Indeed, a pro-inflammatory climate created by bacterial endotoxin or lipopolysaccharide is thought to induce secondary inflammatory mediators (like nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)) via Toll-like receptors in the peritoneal cavity, creating an environment conducive to the development of endometriosis [

43,

44]. The abundance of Gram-negative bacteria in the microbiota of patients with endometriosis would support this theory [

43]. In addition,

E. coli has been found more frequently in the menstrual blood and endometrial smears of women with endometriosis than in control, reinforcing the hypothesis of bacterial contamination [

45,

46]. A study by Tai et al. in 2018 showed an increased risk (HR 3.02) of endometriosis in patients with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) adding to the idea of an intricate relationship between inflammation, dysbiosis and endometriosis [

47].

Moreover, bacteria inside the uterus are more diverse in people with endometriosis [

48,

49]. They contain fewer

Lactobacillus species than controls [

43]. Whether this diversity is more prone to a pathological state is not yet known but it could be a hallmark of endometriosis and a diagnostic tool. A recent study found that there are significant differences in the cervical microbiota of patients with endometriosis [

48]. These differences could be a diagnostic indicator of endometriosis. Furthermore, a recent study by Perrotta et al. found that certain profiles of the vaginal microbiome could be specifically linked to certain stages of endometriosis [

50].

This relationship between microbiota and endometriosis could also lead to specific treatments for this disease. In a recent study by Chadchan et al, endometriotic lesions were significantly smaller in mice treated by broad-spectrum antibiotics than controls with fewer proliferating cells [

51]. Similarly, probiotics, which are live organisms that can positively modify the microbiota when ingested, might be a way of treating the disease [

52].

7. Oncology

Oncology is another medical field in which the endometrial microbiota could play an important role. Infectious diseases and their involvement in the development of certain types of cancer are well known through various pathways: genetic mechanisms, chronic inflammation, and epithelial injury.

H. pylori, for instance, promotes gastric cancer by inducing chronic inflammation, thus creating bacterial proliferation, and, subsequently, the conversion of nitrates by bacteria into carcinogens [

53]. Although mice infected only with

H. Pylori do not develop more tumors, or even fewer, than their pathogen-free counterparts, this bacterium acts as a promoting agent of a more complex microbiota, leading thus to the previously mentioned carcinogenic effect [

53].

The microbiota, via its altered state called dysbiosis, is suspected to promote carcinogenesis by altering the host immune defense responses [

54], shifting the balance between cell proliferation and death, and influencing the metabolism of self-produced factors, ingested molecules and drugs [

55,

56]. As an example, NF-κB, a key regulator of inflammation in cancer, has been shown to be activated by certain bacteria (such as

F. nucleatum in colorectal cancer) through the activation of Toll-like receptors and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors [

57].

Walther-António et al. described that a high vaginal pH, a hallmark of dysbiosis, is associated with endometrial cancer (EC) [

58]. In their study, specific bacteria such as

Firmicutes,

Spirochaetes,

Actinobacteria and

Proteobacteria were identified in women with EC suggesting that a different microbiota may be associated with a carcinologic condition of the uterus. In a study by Lu et al.,

Micrococcus was associated with endometrial microbiota dysbiosis and inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-⍺, IL-6 or IL-8) in EC patients [

59]. These findings could be helpful for future research exploring the relationship between endometrial microbiota, inflammatory responses and cancer [

59].

The efficacy of cancer treatment is also impacted by the microbiome, as shown by various types of malignancies, such as melanoma [

60].

8. Conclusion

Research into the importance of the endometrial microbiota in gynecology is increasing exponentially. However, many aspects still need to be elucidated before a consensus can be reached. The characterization of a normal microbiota is not yet established, as is the case for Lactobacilli. Only certain types of bacteria have been identified as being associated with a pathological or healthy state. The sampling method also needs to be standardized and improved to avoid potential contamination. New technical approaches have been developed to overcome this obstacle. Moreover, analysis of the microbiota using NGS rather than culture-based methods should be the norm in order to detect all taxa within a sample. Finally, one of the limitations of recent studies concerns the size of population samples, which are still relatively small.

Prospective studies on larger populations, with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, are needed to investigate the different fields of applications with a strong clinical perspective. A thorough understanding of the interactions between the microbiota and the host will potentially open up new avenues for prevention, diagnosis and future therapies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ursell LK, Metcalf JL, Parfrey LW, Knight R. Defining the human microbiome. Nutr Rev. 2012, 70(Suppl 1), S38–S44. [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Bello MG, Godoy-Vitorino F, Knight R, Blaser MJ. Role of the microbiome in human development. Gut 2019, 68, 1108–1114. [CrossRef]

- Baker JM, Chase DM, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Uterine Microbiota: Residents, Tourists, or Invaders? Front Immunol. 2018, 9, 208. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen C, Song X, Wei W, et al. The microbiota continuum along the female reproductive tract and its relation to uterine-related diseases. Nat Commun. 2017, 8(1), 875. [CrossRef]

- Reschini M, Benaglia L, Ceriotti F, et al. Endometrial microbiome: sampling, assessment, and possible impact on embryo implantation. Sci Rep. 2022, 12(1), 8467. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 6. Moreno I, Simon C. Relevance of assessing the uterine microbiota in infertility. Fertility and Sterility. 2018, 110(3), 337–343. [CrossRef]

- Sola-Leyva, A. , Andrés-León, E., Molina, N. M., Terron-Camero, L. C., Plaza-Díaz, J., Sáez-Lara, M. J., Gonzalvo, M. C., Sánchez, R., Ruíz, S., Martínez, L., & Altmäe, S.. Mapping the entire functionally active endometrial microbiota. Human Reproduction 2021, 36(4), 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 8. Mor A, Driggers PH, Segars JH. Molecular characterization of the human microbiome from a reproductive perspective. Fertility and Sterility. 2015, 104(6), 1344–1350. [CrossRef]

- 9. Kitaya K, Takeuchi T, Mizuta S, Matsubayashi H, Ishikawa T. Endometritis: new time, new concepts. Fertility and Sterility. 2018, 110(3), 344–350. [CrossRef]

- Toson B, Simon C, Moreno I. The Endometrial Microbiome and Its Impact on Human Conception. IJMS. 2022, 23(1), 485. [CrossRef]

- Gajer, P., Brotman, R. M., Bai, G., Sakamoto, J. M., Schütte, U. M. E., Zhong, X., Koenig, S. N., Fu, L., Sam, Z., MA, Zhou, X., Abdo, Z., Forney, L. J., & Ravel, J.. Temporal Dynamics of the Human Vaginal Microbiota. Science Translational Medicine, 2012, 4(132). [CrossRef]

- Walsh, D. M., Hokenstad, A. N., Chen, J., Sung, J., Jenkins, G. D., Chia, N., Nelson, H., Mariani, A., & Walther-Antonio, M.. Postmenopause as a key factor in the composition of the Endometrial Cancer Microbiome (ECbiome). Scientific Reports 2019, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Riganelli, L., Iebba, V., Piccioni, M. G., Illuminati, I., Bonfiglio, G., Neroni, B., Calvo, L., Gagliardi, A., Levrero, M., Merlino, L., Mariani, M., O, C., Pietrangeli, D., Schippa, S., & Guerrieri, F.. Structural Variations of Vaginal and Endometrial Microbiota : Hints on Female Infertility. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X. S., Laven, J. S., Louwers, Y. V., Budding, A. E., & Schoenmakers, S.. Microbiome as a predictor of implantation. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2022, 34(3), 122–132. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Bastidas, D., Camacho-Arroyo, I., & García-Gómez, E.. Current findings in endometrial microbiome : impact on uterine diseases. Reproduction 2022, 163(5), R81–R96. [CrossRef]

- D’Ippolito, S., Di Nicuolo, F., Pontecorvi, A., Gratta, M., Scambia, G., & Di Simone, N.. Endometrial microbes and microbiome: Recent insights on the inflammatory and immune “players” of the human endometrium. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2018, 80(6), e13065. [CrossRef]

- Pelzer, E., Willner, D., Buttini, M., & Huygens, F.. A role for the endometrial microbiome in dysfunctional menstrual bleeding. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek International Journal of General and Molecular Microbiology, 2018, 111(6), 933–943. 2018, 111(6), 933–943. [CrossRef]

- Critchley, H. O. D., Babayev, E., Bulun, S. E., Clark, S., Garcia-Grau, I., Gregersen, P. K., Kilcoyne, A., Kim, J.-Y. J., Lavender, M., Marsh, E. E., Matteson, K. A., Maybin, J. A., Metz, C. N., Moreno, I., Silk, K., Sommer, M., Simon, C., Tariyal, R., Taylor, H. S., Griffith, L. G.. Menstruation: Science and society. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2020, 223(5), 624–664. [CrossRef]

- Vomstein, K., Reider, S., Böttcher, B., Watschinger, C., Kyvelidou, C., Tilg, H., Moschen, A. R., & Toth, B.. Uterine microbiota plasticity during the menstrual cycle : Differences between healthy controls and patients with recurrent miscarriage or implantation failure. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2022, 151, 103634. [CrossRef]

- Mor, G. , Aldo, P., & Alvero, A. B.. The unique immunological and microbial aspects of pregnancy. Nature Reviews Immunology 2017, 17(8), 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, G., Van Calsteren, K., Bellen, G., Reybrouck, R., Van den Bosch, T., Riphagen, I. and Van Lierde, S.. Predictive value for preterm birth of abnormal vaginal flora, bacterial vaginosis and aerobic vaginitis during the first trimester of pregnancy. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2009, 116, 1315–1324. [CrossRef]

- McMillan, A., Rulisa, S., Sumarah, M. et al. A multi-platform metabolomics approach identifies highly specific biomarkers of bacterial diversity in the vagina of pregnant and non-pregnant women. Sci Rep 5 2015, 14174. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, I. M., Codoñer, F. M., Vilella, F., Valbuena, D., Martinez-Blanch, J. F., Jimenez-Almazán, J., Alonso, R., Alamá, P., Remohí, J., Pellicer, A., Ramon, D., & Simón, C.. Evidence that the endometrial microbiota has an effect on implantation success or failure. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2016, 215(6), 684–703. [CrossRef]

- Kitaya, K., Nagai, Y., Arai, W., Sakuraba, Y., & Ishikawa, T. (2019). Characterization of Microbiota in Endometrial Fluid and Vaginal Secretions in Infertile Women with Repeated Implantation Failure. Mediators of Inflammation 2019, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Ko, E. Y., Wong, K., Chen, X., Cheung, W., Law, T. S. M., Chung, J. P. W., Lau, C. B., Li, T., & Chim, S. S.. Endometrial microbiota in infertile women with and without chronic endometritis as diagnosed using a quantitative and reference range-based method. Fertility and Sterility 2019, 112(4), 707–717.e1. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Wong, K., Ko, E. Y., Chen, X., Huang, J., Lau, C. B., Li, T., & Chim, S. S.. Systematic Comparison of Bacterial Colonization of Endometrial Tissue and Fluid Samples in Recurrent Miscarriage Patients : Implications for Future Endometrial Microbiome Studies. Clinical Chemistry 2018, 64(12), 1743–1752. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, I. M., Garcia-Grau, I., Perez-Villaroya, D., Gonzalez-Monfort, M., Bahceci, M., Barrionuevo, M. J., Taguchi, S., Puente, E. V., DiMattina, M., Lim, M. Y., Meneghini, G., Aubuchon, M., Leondires, M., Izquierdo, A., Perez-Olgiati, M., Chavez, A., Seethram, K., Baù, D., Gomez, C. A., Simón, C.. Endometrial microbiota composition is associated with reproductive outcome in infertile patients. Microbiome 2022, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Møller, B. R., Kristiansen, F. V., Thorsen, P., Frost, L., & Mogensen, S. C.. Sterility of the uterine cavity. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1995, 74(3), 216–219. [CrossRef]

- Pruski, P., Van Arem, B., Lewis, H. V., Capuccini, K., Inglese, P., Chan, D. P., Brown, R. J. C., Kindinger, L., Lee, D. Y., Smith, A., Marchesi, J. R., McDonald, J. A. K., Cameron, S. J. S., Alexander-Hardiman, K., David, A. L., Stock, S. J., Norman, J. E., Terzidou, V., Teoh, T. G.,... MacIntyre, D. A.. Direct on-swab metabolic profiling of vaginal microbiome host interactions during pregnancy and preterm birth. Nature Communications 2021, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Tewari, R., Dudeja, M., Das, A. K., & Nandy, S.. Kocuria Kristinae in Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infection : A Case Report. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 2013. [CrossRef]

- Riganelli, L., Iebba, V., Piccioni, M. G., Illuminati, I., Bonfiglio, G., Neroni, B., Calvo, L., Gagliardi, A., Levrero, M., Merlino, L., Mariani, M., O, C., Pietrangeli, D., Schippa, S., & Guerrieri, F.. Structural Variations of Vaginal and Endometrial Microbiota: Hints on Female Infertility. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Cicinelli, E., Matteo, M., Tinelli, R., Pinto, V., Marinaccio, M., Indraccolo, U., De Ziegler, D., & Resta, L.. Chronic Endometritis Due to Common Bacteria Is Prevalent in Women With Recurrent Miscarriage as Confirmed by Improved Pregnancy Outcome After Antibiotic Treatment. Reproductive Sciences 2014, 21(5), 640–647. [CrossRef]

- De Ziegler, D., Pirtea, P., Galliano, D., Cicinelli, E., & Meldrum, D. R.. Optimal uterine anatomy and physiology necessary for normal implantation and placentation. Fertility and Sterility 2016, 105(4), 844–854. [CrossRef]

- Mor, G., Aldo, P., & Alvero, A. B.. The unique immunological and microbial aspects of pregnancy. Nature Reviews Immunology 2017, 17(8), 469–482. [CrossRef]

- Laškarin, G., Kämmerer, U., Rukavina, D., Thomson, A. W., Fernandez, N., & Blois, S. M.. Antigen-Presenting Cells and Materno-Fetal Tolerance : An Emerging Role for Dendritic Cells. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2007, 58(3), 255–267. [CrossRef]

- Mor G, Aldo P, Alvero AB. The unique immunological and microbial aspects of pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol 2017, 17(8), 469–482. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, C. A.. Immunology of pregnancy. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2010, 69(3), 357–365. [CrossRef]

- Gnainsky, Y. , Granot, I., Aldo, P., Barash, A., Or, Y., Mor, G., & Dekel, N.. Biopsy-induced inflammatory conditions improve endometrial receptivity : the mechanism of action. Reproduction 2014, 149(1), 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardos, J. D., Fiorentino, D. G., Longman, R. E., & Paidas, M. J.. Immunological Role of the Maternal Uterine Microbiome in Pregnancy : Pregnancies Pathologies and Alterated Microbiota. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Espinós, J. P., Fábregues, F., Fontes, J. T., Garcia-Velasco, J. A., Llácer, J., Requena, A. T., Checa, M. A., & Bellver, J.. Impact of chronic endometritis in infertility : a SWOT analysis. Reproductive Biomedicine Online 2021, 42(5), 939–951. [CrossRef]

- Bouet, P., Hachem, H. E., Monceau, E., Gariépy, G., Kadoch, I., & Sylvestre, C.. Chronic endometritis in women with recurrent pregnancy loss and recurrent implantation failure : prevalence and role of office hysteroscopy and immunohistochemistry in diagnosis. Fertility and Sterility 2016, 105(1), 106–110. [CrossRef]

- Cicinelli, E., Matteo, M., Tinelli, R., Lepera, A., Alfonso, R., Indraccolo, U., Marrocchella, S., Greco, P., & Resta, L.. Prevalence of chronic endometritis in repeated unexplained implantation failure and the IVF success rate after antibiotic therapy. Human Reproduction 2015, 30(2), 323–330. [CrossRef]

- Khan, K. N., Fujishita, A., Hiraki, K., Kitajima, M., Nakashima, M., Fushiki, S., & Kitawaki, J.. Bacterial contamination hypothesis : a new concept in endometriosis. Reproductive Medicine and Biology 2018. [CrossRef]

- Boucher, A., Brichant, G., Gridelet, V., Nisolle, M., Ravet, S., Timmermans, M., & Henry, L.. Implantation Failure in Endometriosis Patients: Etiopathogenesis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11(18), 5366. [CrossRef]

- Khan, K. N., Fujishita, A., Kitajima, M., Hiraki, K., Nakashima, M., & Masuzaki, H.. Intra-uterine microbial colonization and occurrence of endometritis in women with endometriosis†. Human Reproduction 2014, 29(11), 2446–2456. [CrossRef]

- Khan, K. N., Kitajima, M., Hiraki, K., Yamaguchi, N., Katamine, S., Matsuyama, T., Nakashima, M., Fujishita, A., Ishimaru, T., & Masuzaki, H.. Escherichia coli contamination of menstrual blood and effect of bacterial endotoxin on endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility 2010, 94(7), 2860–2863.e3. [CrossRef]

- Tai, F., Chang, C. Y., Chiang, J., Lin, W. C., & Wan, L.. Association of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease with Risk of Endometriosis: A Nationwide Cohort Study Involving 141,460 Individuals. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2018, 7(11), 379. [CrossRef]

- Endometrial microbiota is more diverse in people with endometriosis than symptomatic controls. Scientific Reports 2021, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Wei, W., Xu, J., Tang, H., Zeng, L., & Wu, R.. Microbiota composition and distribution along the female reproductive tract of women with endometriosis. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials 2020, 19(1). [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, A., Borrelli, G. M., De Oliveira Martins, C., Kallas, E. G., Sanabani, S. S., Griffith, L. G., Alm, E. J., & Abrão, M. S.. The Vaginal Microbiome as a Tool to Predict rASRM Stage of Disease in Endometriosis: a Pilot Study. Reproductive Sciences 2020, 27(4), 1064–1073. [CrossRef]

- Chadchan, S. B., Cheng, M., Parnell, L. A., Yin, Y., Schriefer, A. E., Mysorekar, I. U., & Kommagani, R.. Antibiotic therapy with metronidazole reduces endometriosis disease progression in mice: a potential role for gut microbiota. Human Reproduction 2019, 34(6), 1106–1116. [CrossRef]

- Molina, N. M., Sola-Leyva, A., Sáez-Lara, M. J., Plaza-Díaz, J., Tubic-Pavlovic, A., Romero, B., Clavero, A., Mozas-Moreno, J., Fontes, J. T., & Altmäe, S.. New Opportunities for Endometrial Health by Modifying Uterine Microbial Composition: Present or Future? Biomolecules 2020, 10(4), 593. [CrossRef]

- Lofgren, J. L., Whary, M. T., Ge, Z., Muthupalani, S., Taylor, N. S., Mobley, M. W., Potter, A., Varro, A., Eibach, D., Suerbaum, S., Wang, T. C., & Fox, J. G.. Lack of Commensal Flora in Helicobacter pylori–Infected INS-GAS Mice Reduces Gastritis and Delays Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Gastroenterology 2011, 140(1), 210–220.e4. [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, R. F., & Jobin, C.. The microbiome and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2013, 13(11), 800–812. [CrossRef]

- Garrett, W. S.. Cancer and the microbiota. Science 2015, 348, 80–86. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łaniewski, P., Ilhan, Z. E., & Herbst-Kralovetz, M. M.. The microbiome and gynaecological cancer development, prevention and therapy. Nature Reviews Urology 2020, 17(4), 232–250. [CrossRef]

- Fulbright, L., Ellermann, M., & Arthur, J. C.. The microbiome and the hallmarks of cancer. PLOS Pathogens 2017, 13(9), e1006480. [CrossRef]

- Walther-Antonio, M., Chen, J., Multinu, F., Hokenstad, A. N., Distad, T. J., Cheek, E., Keeney, G. L., Creedon, D. J., Nelson, H., Mariani, A., & Chia, N.. Potential contribution of the uterine microbiome in the development of endometrial cancer. Genome Medicine 2016, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Lu, W., He, F., Lin, Z., Liu, S., Tang, L., Huang, Y., & Hu, Z.. Dysbiosis of the endometrial microbiota and its association with inflammatory cytokines in endometrial cancer. International Journal of Cancer 2021, 148(7), 1708–1716. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, V., Spencer, C. N., Nezi, L., Reuben, J. M., Andrews, M., Karpinets, T., Prieto, P., Vicente, D., Hoffman, K. D., Wei, S., Cogdill, A. P., Zhao, L., Hudgens, C., Hutchinson, D. P., Manzo, T., De Macedo, M. P., Cotechini, T., Kumar, T. K. S.

- Chen, W., Wargo, J. A.. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti–PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359(6371), 97–103. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).