1. Introduction

New materials with enhanced optical properties have been developed to address the energy crisis for future technology. The first transparent conducting oxide (TCO) is SnO2, which is used as the front surface electrode in all types of solar cell materials 1–3. This is particularly true when making solar cells using thin film technology such as amorphous silicon, cadmium telluride or copper indium gallium diselenide (CIGS). These TCO materials are used as one coating, two coatings sometimes as three coatings as well 4–6. The peculiar electronic structure and dynamical properties of SnO2 polymorphs increase the intention to study their other optical properties. In recent years, wide bandgap semiconductors have attracted the attention of researchers due to their applications in the fields of optoelectronic device fabrication, photonics, the electron transport layer (ETL) in perovskite solar cells (PSCs) and photo-chemistry 7–10. More recently, SnO2 has found its most significant use in supercapacitors, where it has been shown to enhance both capacitance and energy density 11. The optical properties of the material are of fundamental interest for the abovementioned application. SnO2 needs better optoelectronic characteristics to work well in all the above devices. Hence, this study mainly concerns the optical properties of the stable SnO2 polymorphs.

Several methods are reported in the literature to address the issue of SnO2 optical properties; hence, an overview of related works is provided here. It has been previously reported in the literature by Rabilah Gilani et al. that the structural and optical properties of rutile-type SnO2 for various pseudopotentials. And also shows that the band gap and optical characteristics calculated from HSE06 are quite close to the experimental values 12. Similar research has been carried out by shao ting ting et al. which coincides with Rabilah Gilani et al. 13. The optical characteristics of prospective semiconducting materials such as TiO2, SnO2, ZrO2 and HfO2 have been investigated using the meta-GGA functional and it has been demonstrated that SnO2 and TiO2 are effective photovoltaic (PV) materials 14. Generally, a material's adjustable electronic characteristics make it efficient through doping. Sc-doped SnO2 has been reported by Julaiba Tahsina Mazumder et al. Sc-doped SnO2 exhibits a blue-shifted optical transmittance, low absorption and reflectivity due to a wider band gap, these properties suggest the material may find utility in transparent conducting applications 15. The optical properties of Ti-doped SnO2 have been studied and the absorption edge varies according to the doping concentration 16. Several authors have recognized rutile SnO2 as a potential candidate for many applications 17–22, however, there are many polymorphs other than rutile available. Thus, we study the optical properties of seven structurally, dynamically and mechanically stable polymorphs 23.

The effective mass, transition dipole moment (TDM), SLME and XANES of SnO2 polymorphs have not been theoretically addressed in the literature. To determine the material's feasibility for use in PV applications, we planned to investigate the abovementioned polymorphic features in detail. There are some kinds of literature available on XANES of rutile-SnO2 and doped rutile SnO2. Jae-Yoon Bae et al. reported Sn k-edge spectra of tetragonal and orthogonal phases of SnO2 thin film. The transition between the core level and the unoccupied electronic state above the fermi level is addressed. Also, the deviations between the XANES spectra of the tetragonal and orthorhombic phases were examined 24. The lithiation and delithiation processes in metal-doped SnO2 are being investigated using XANES to provide structural insight 25. The photovoltaic device efficiency can be calculated from the SLME. Aleksandar Zivkovi et al. computed the photovoltaic efficiency of ZnP2 polymorphs from SLME 26. As predicted by SLME, lead-free double perovskite materials like Cs2AgBiCl6 have proven useful as solar cell absorber layers 27. No theoretical studies exist on the solar cell efficiency and TMD of the SnO2 polymorphs; therefore, we tried to figure out which polymorph of SnO2 is the most essential member of perovskite solar cell material.

By applying the high-end computational code using VASP, we can calculate the optical parameters using the first-principles method. Only a few studies were available on the theoretical approach to the optical properties of SnO2 polymorphs on HSE06 function with rutile and CaCl2 polymorphs. This is the first time we employed the HSE06 functional to elucidate the optical properties as well as the effective mass of the seven structurally, mechanically and dynamically stable polymorphs (Pa - Pyrite, P42/mnm - rutile, Pnnm-CaCl2, Pbcn-PbO2, Pbca-ZrO2, Pnma-contunnite, I4/m). It is well known that the PBE functional underestimates the electronic and optical properties of semiconductors. The hybrid functionals such as HSE06 and B3LYP may yields results comparable to the experimental results.

2. Computational methodology

The optical properties of seven stable SnO2 polymorphs were computed through the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP) 28, 29. The part of valence states of stannic (Sn) and oxygen (O) are 5s2, 5p2 and 2s2, 2p4. The HSE06 functional has been used to calculate the optical properties of the polymorphs. As the electronic bandgap of the semiconductors can have obtained better accuracy in this functional, hence we used HSE06 for calculating the dynamic dielectric functions. This gives better accuracy compared to other functional 30. The k-point sampling used for optical properties is three times greater than a k mesh for static calculations. The optimized crystal structure of the SnO2 polymorphs was used to calculate the optical and other related properties. The computed dynamic dielectric functions were used to assess the optical properties of these compounds, including the optical spectra and absorption. Density functional perturbation theory along with local field effect approaches was used to determine static dielectric constants in HSE06 31. The VASPKIT tool is used to calculate the effective mass, optical properties, TDM, SLME and XANES of the SnO2 polymorphs 32. The optical properties were obtained from the imaginary part of the complex dielectric function.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The effective mass of hole and electron (m*)

The effective mass provides precise information on the transfer rate of charge carriers (electrons or holes) assessed by the effective mass of electrons and holes. In addition, this is an important physical parameter that predicts the efficiency of solar cells. The photo-generated charge carrier is typically inversely proportional to their effective masses

33–35. Consequently, the transfer rate of carriers decreases as effective mass increases and vice versa. To illustrate the various recombination rates of charge carriers among the polymorphs, the effective mass of charge carriers along specified directions was computed by fitting parabolic functions around the CBM or the VBM using the following formula:

The effective masses of the SnO

2 polymorphs were given in

Table 1. The effective mass of carriers can be calculated using the band structure of the material. The band structure of the SnO

2 polymorphs was reported in the previous literature

23. The effective mass of carriers is related to the curvature of the energy bands in the polymorphs. The curvature is defined as the second derivative of the energy with respect to the wave vector and can be calculated using finite differences between neighboring points on the band structure. The negative sign of the effective mass indicates that the band curves away from the maximum, also the electrons are responsible for conductivity. When we computed the effective masses, m

e* and m

h* of polymorphs of SnO

2 we observed the positive m* for most of the polymorphs, which shows its semiconducting nature. Though

P42/mnm and

Pnnm have similar structures, there is a variation observed in their mobility. The average effective mass of the charge carriers was given and it is infrared that the charge transfer rate in the

Pbca polymorph is highest among them. The effective mass of

P42/mnm is compared with the experimental results and has deviated 10 % from the experimental results

36. In addition, the effective mass of the

Pnma is lower compared to seven stable polymorphs; hence, its mobility is higher. For

PaP42/mnm, Pnnm and

I4/m polymorphs the effective mass of electrons lower than the effective mass of holes. Which has higher mobility and is suitable for photovoltaic devices.

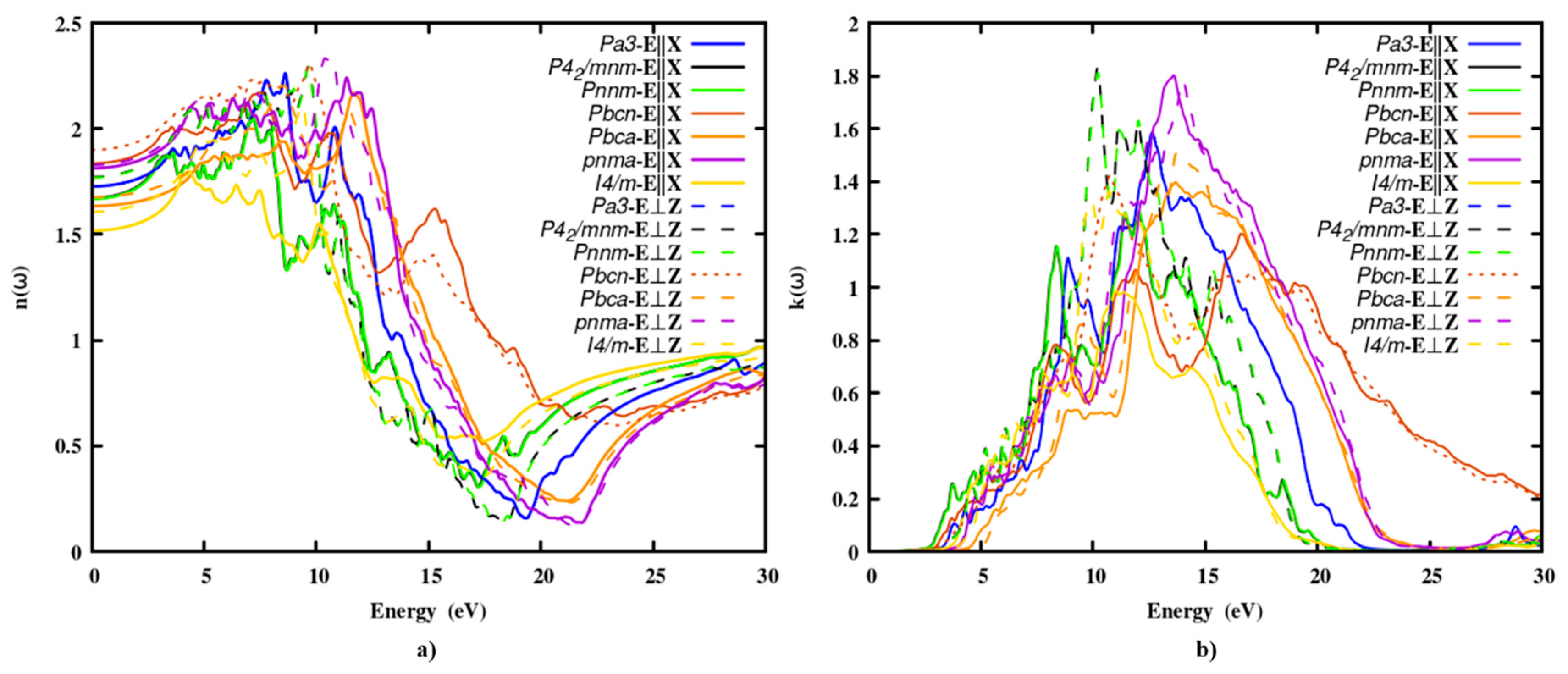

3.2. Optical properties

Optical properties of solids can be used to investigate the electronic band structure, lattice vibrations, lattice defects, impurity levels and magnetic excitations in detail. In general, the two most important optical constants of a material are its refractive index n(𝜔) and extinction coefficient k(𝜔), both of which are wavelength dependent and are referred to as dispersion. These two depend on the complex dielectric function 𝜖(𝜔), once we calculated the imaginary part of the dielectric function (i.e. absorption) it can be used to find the real part (i.e., dispersion) or vice versa. The index of refraction and the other optical parameters are the same along the two transverse directions for an isotropic system, while in the other case, they are different along the two directions 37. The dielectric function 𝜖(𝜔), refractive index n(ω), extinction coefficient k(ω), absorption coefficient α(ω), reflectivity R(ω), energy loss function L(ω) and optical conductivity σ(ω) were calculated using the HSE06 functional 31, 38.

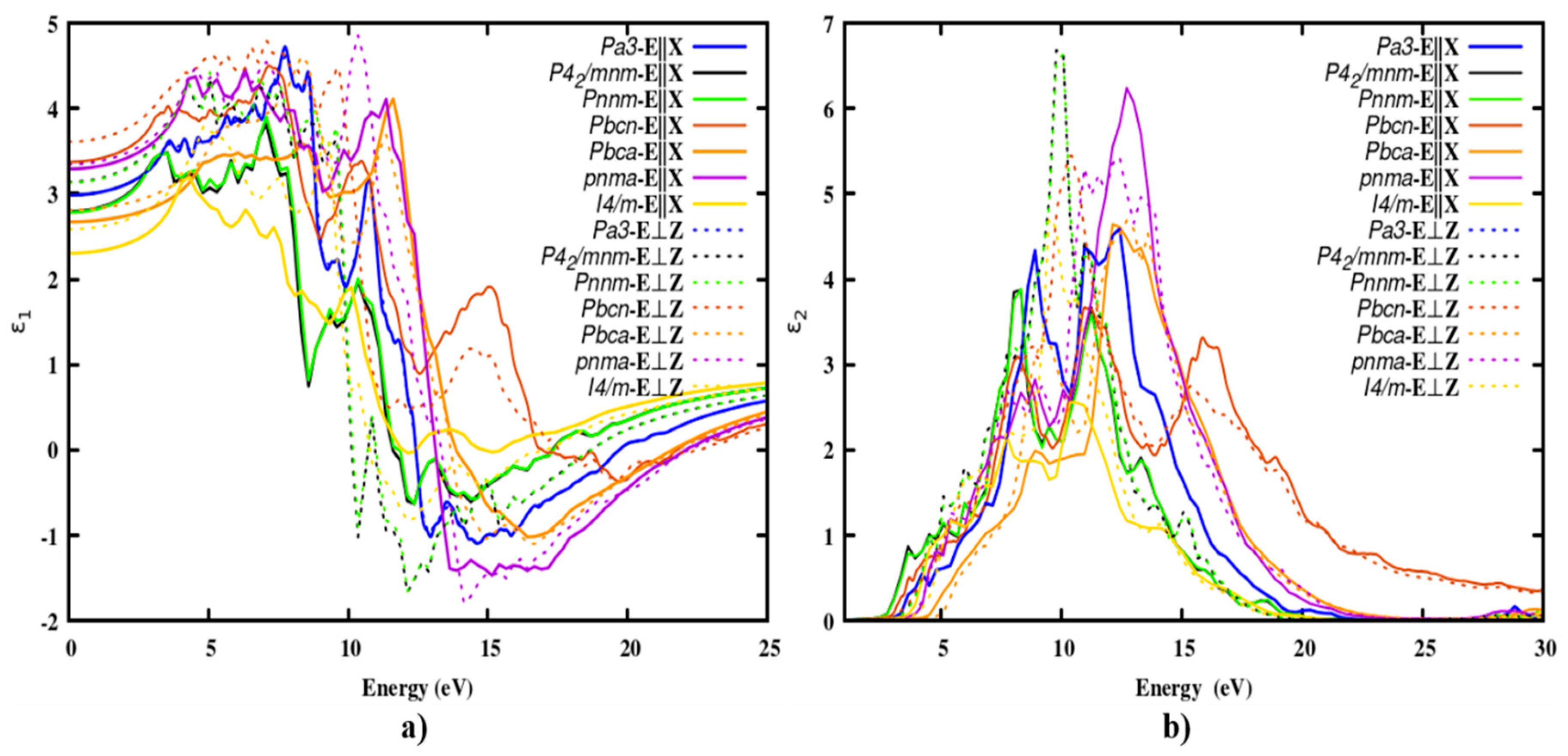

3.2.1. Dielectric function

The optical parameters along all three components of polarization were studied. When light interacts with a material, the complex dielectric function offers information about the type of interaction that occurs. The real component of the complex dielectric function 𝜖

1(𝜔) was used to identify the electronic polarizability of polymorphs along different directions. The static dielectric constant at zero frequency (ω = 0) along the crystallographic axis was calculated and given in

Table 2. The cubic polymorph is isotropic, as can be seen from the similar dielectric constant along in-plane and out-of-plane polarization. However, it is anisotropic for the tetragonal and orthorhombic phases, which arise due to the tetragonal distortion. The intermediate band solar cells and their anisotropic optical properties were examined by

Murugesan Rasukkannu et al.

39, 40 Figure 1 (a) and (b), show the complex dielectric functions of polymorphs of SnO

2 along in-plane (E||X) and out-of-plane (E⊥Z) of polarization. The static dielectric constant of

P42/mnm polymorph is 2.79 which is consistent with other reported values

12, 30, 41. Which is a 4 % variation from the calculated HSE06 functional value and a 9 % difference from the experimental value. The dielectric functions of

P42/mnm and

Pnnm lie one over the other due to their structure similarity and they are coming under the same space group. While the

Pbcn polymorph is the biggest among the seven and the newly identified polymorph

I4/m has the smallest static dielectric constant. Hence the polymorphs

P42/mnm and

I4/m were suitable for ETL in solar cells. Moreover, the real part of the dielectric function has peaks at lower energy levels revealing that the higher polarizability at the lower energy levels were shown in

Figure 1(a). Two prominent peaks were appearing nearly at 7 and 10 eV along the

E||X direction but for the E⊥

Z direction we observed a broad peak scattered from 4 to 9.5 eV for all the polymorphs. For all SnO

2 polymorphs, the peaks arise due to the transition that occurs between the Sn-5

p and O-2

p states. In addition, the corresponding resonance peak appearing in the range of 9.5 to 13.6 eV.

In particular, negative values of the real component were observed in the energy range from 12.5 eV to 21.5 eV. This is because electromagnetic radiation is reflected by the materials due to the phenomenon of anomalous dispersion, this specific range of energy indicates that the material has behaved like a metal.

Also, the imaginary part of the dielectric function is directly related to the absorption of light. An inter-band transition between the valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM) led to the resonance peaks of the polymorphs. The spectral distribution of the imaginary part of the function is given in

Figure 1 (b). For all polymorphs, the main peak of the imaginary part was scattered over a wide range of energies from 6 to 17 eV for both parallel and perpendicular polarization. All the reported polymorphs were effective in the UV region. In addition, the optical absorption edge was observed from 1.3 to 2.3 eV. This is due to the fundamental band gap, as already reported. The findings are consistent with the reported values. While the rutile polymorph had previously been studied with HSE06 by

Sagadevan et al. the remaining polymorphs were reported for the first time with HSE06

30.

3.2.2. The refractive index and extinction coefficient

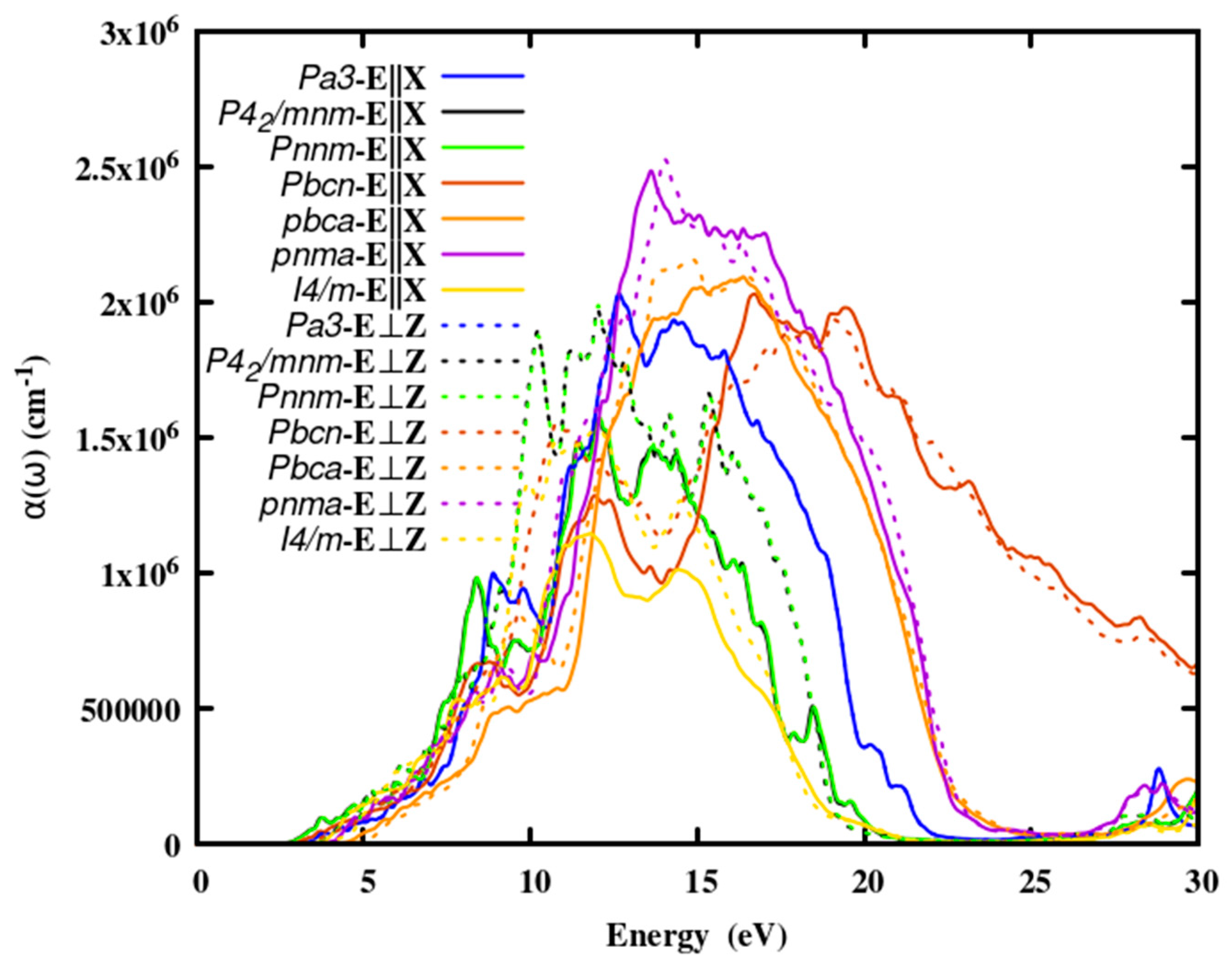

3.2.3. The absorption coefficient

Optical absorption spectra are significant in any optical material because they are a measure of the intensity of electromagnetic energy that passes through it.

Figure 3, depicts the spectrum distribution of the absorption coefficient of SnO

2 polymorphs. The absorption edge energies of the polymorphs were given in Table 3. The absorption spectra increased sharply at about 10 eV after producing a broad absorption peak, it tailed off. Since the absorption spectra are insignificant below the absorption edge, photon energy is transmitted in this energy range. Energy absorption is low in the visible region but strong in the UV zone. Furthermore, as compared to other binary oxides such as TiO

2, ZrO

2, SiO

2 and HfO

2, the absorption of SnO

2 is lower, making it a good candidate for ELT.

Table 1.

The absorption and the conductive intense peak of the SnO2 polymorphs along in-plane (E||X) and out-of-plane (E⊥Z) of polarization.

Table 1.

The absorption and the conductive intense peak of the SnO2 polymorphs along in-plane (E||X) and out-of-plane (E⊥Z) of polarization.

| Polymorphs |

α(ω) (E||X) |

α(ω) (E⊥Z) |

σ(ω) (E||X) |

σ(ω) (E⊥Z) |

|

Pa-697

|

8.8 eV(3.4)

12.1 to 15.8 |

-- |

8.8,

10.7 to 12.8 |

-- |

| P42/mnm-rutile |

8.1

11.3 to 14.8 |

10.8, 11.9 to 16.8 |

7.9, 11.01 |

9.3, 11.1 |

| Pnnm (58) -CaCl2 |

9.2

13.1 to 17.5 |

9.2

13.1 to 17.5 |

8.2,

11.1, 13.4 |

10.7, 10.8, 15.0 |

| Pbcn (60) -PbO2 |

9.9 to 13.3, 14.4 |

11.77, 14.5 |

11.4, 16.1 |

10.3, 15.5 to 17.8 |

| Pbca (61)-ZrO2 |

9.9, 14.2 to 19.3 |

10.3, 14.2 to 19.3 |

9.1, 11.8 to 13.8 |

9.1, 11.8 to 13.8 |

| Pnma |

7.7, 13.2 to 19.1 |

7.7, 13.1 to 19.1 |

7.8, 10.8 to 13.4 |

7.8, 10.8 to 13.4 |

| I4/m (87) |

11.4, 14.4 |

10.07 to 12.5, 14.4 |

10.5 |

9.4 |

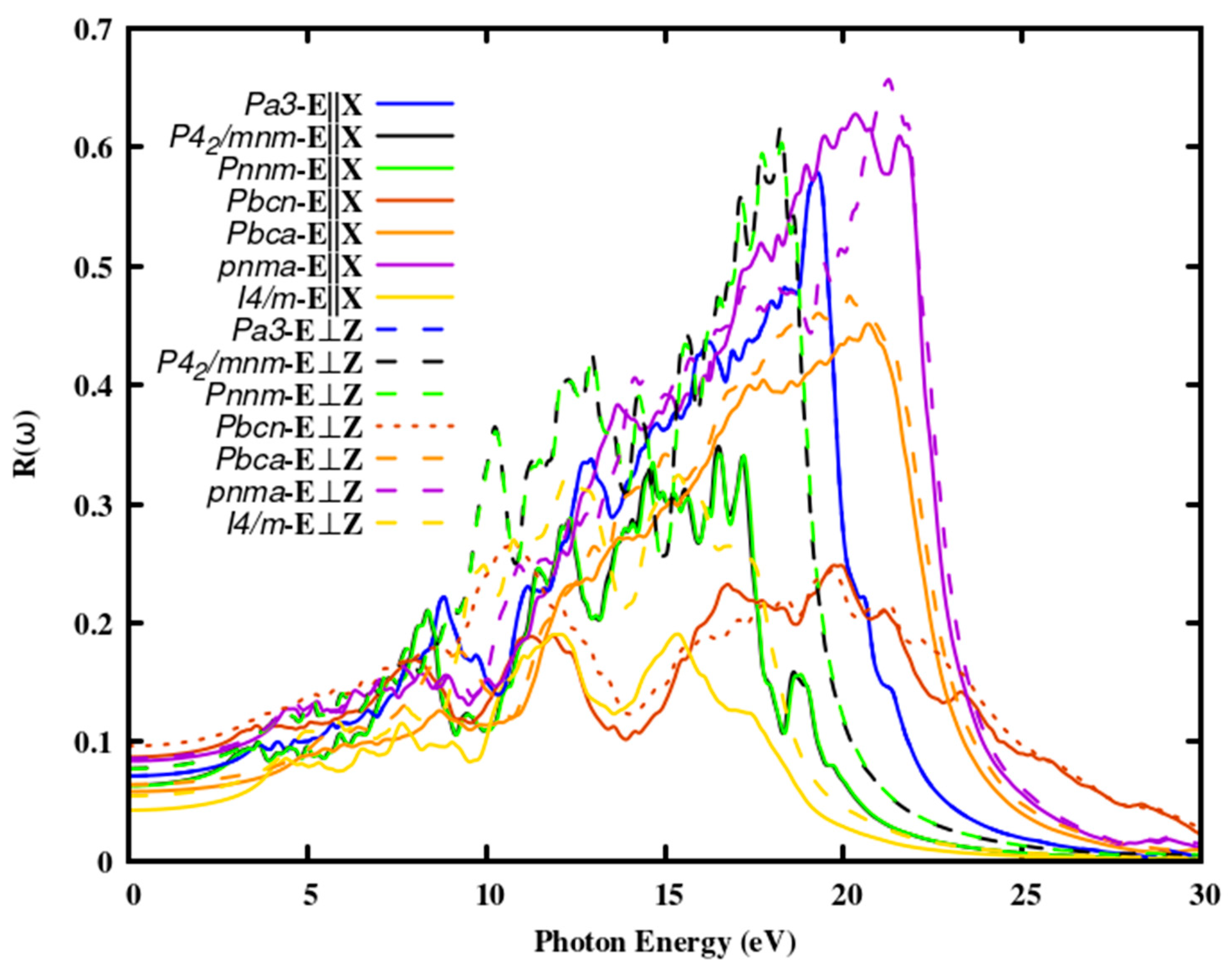

3.2.4. Reflectivity spectra

The selection of effective photovoltaic materials highly depends on their optical reflectance. The limit for the percentage of reflectivity in photovoltaic (PV) cells depends on the specific application and the technology used to manufacture the PV cells. Generally, a lower reflectivity is desirable to maximize the absorption of sunlight and improve the efficiency of the PV cell. For silicon-based PV cells, the industry standard is to aim for a reflectivity of less than 10 % in the visible spectrum (400-700 nm). This is achieved through the use of anti-reflective coatings or textures on the surface of the cell. In

Figure 4, the reflectivity of the SnO

2 polymorphs is illustrated. In the visible and UV regions, the reflectance of SnO

2 polymorphs was detected to be high and lower in the near IR region.

The fact that the reflectivity of polymorph I4/m is the lowest among the six polymorphs suggests that the polymorph's transmittance or absorption is high and that it may be more transparent than the experimental polymorph P42/mnm. The reflectivity of the rutile polymorph is 11.12 % and the newly identified I4/m polymorph is 4.13 % at ω = 0. Which reveals that I4/m SnO2 has the least reflectivity among all the oxides at zero photon energy. The reflectivity reaches about 20 % to 60 % towards the higher energy region of about 20 eV thus these polymorphs are a potential candidate as coating materials. Consequently, all polymorphs have a similar reflectivity pattern, although the intensity might vary between 3 and 25 eV. In this range, oscillations in reflectance up to 25 eV were detected. In the infrared and visible spectral ranges, SnO2 polymorphs exhibit less than 15 % reflectivity; hence, they could be employed as an effective anti-reflective coating.

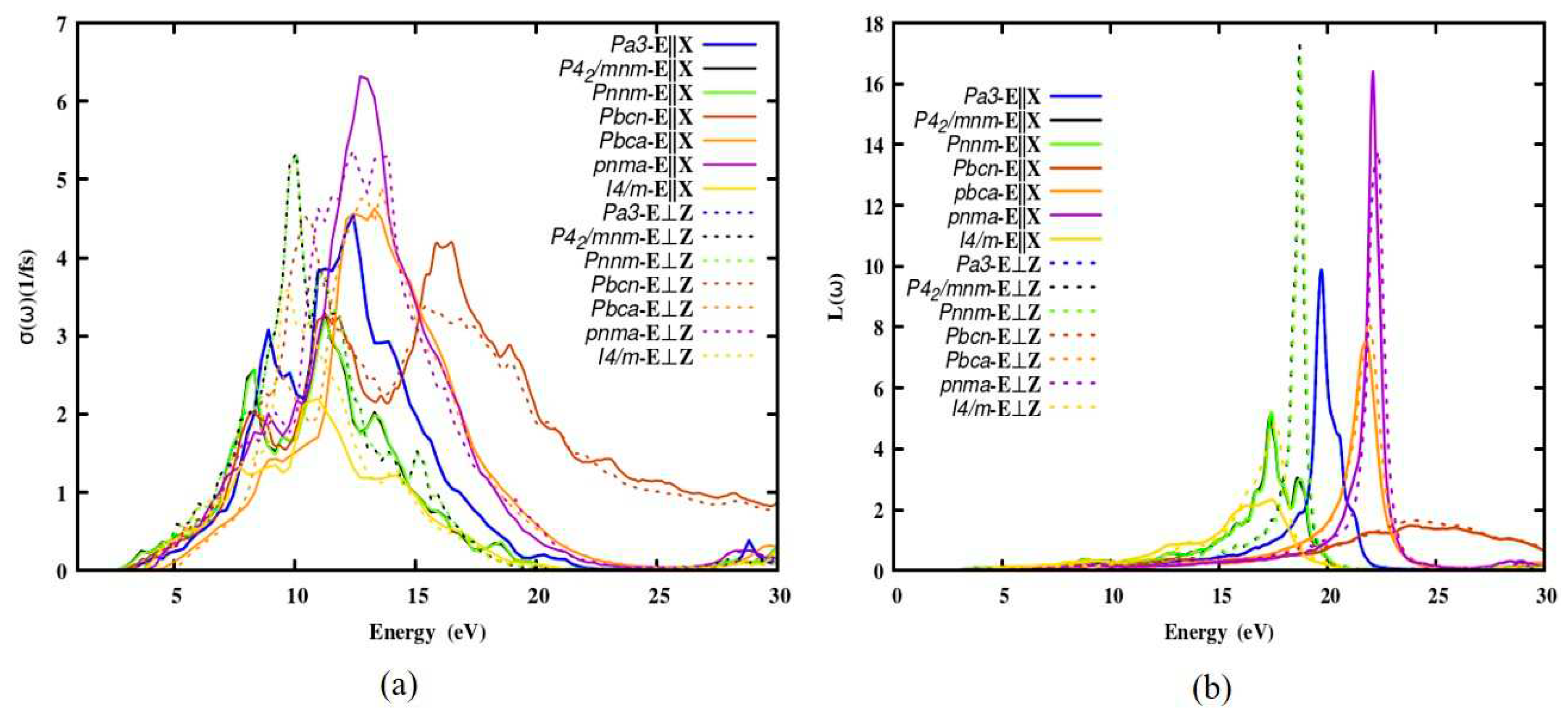

3.2.5. The optical conductivity and energy loss function

The optical conductivity and the energy loss spectra of the polymorphs were computed which are given in

Figure 5. The first peak was observed near 8.6 eV, and the second peak was observed at 12.4 eV. For all the polymorphs no deviation in the optical conductivity along parallel and perpendicular polarization. Interband, intraband and plasma interactions are all defined by the electron energy-loss function (ELF). The energy is lost by a fast-moving electron through the medium. Also, the electron’s inelastic scattering is related to the energy-loss function. No loss has been observed below the optical bandgap of the polymorphs. The loss appears where there is a transition between the valence and conduction band, keeps on increasing, reaches its maximum and then comes down. The loss L (ω) of the polymorphs approaches maximum at 17.3(17 eV), 16.5(22 eV) for

Pnnm and

Pnma polymorphs. The polymorph

Pbcn has the lowest loss function among the seven polymorphs. The change in the reflectivity arrives due to a sharp peak in the loss spectra.

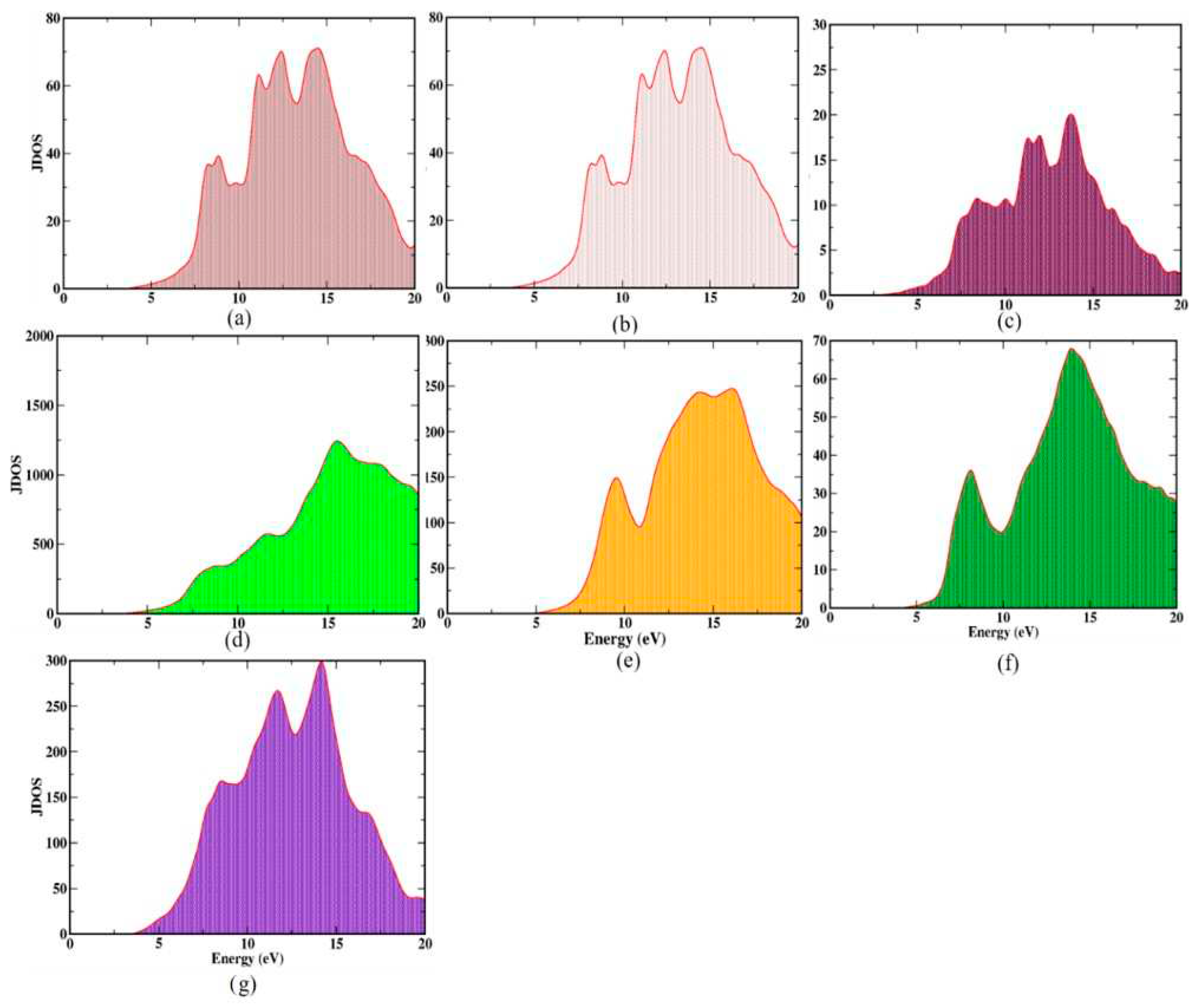

3.3. Optical joint density of states

The optical joint density of states (OJDOS) represents the number of states with which photons can interact; it simultaneously accounts for states in the VBM and CBM that are separated by energy hυ. Hence, the JDOS of SnO

2 polymorphs provides information on the number of absorption and emission states of the crystals

Figure 6, shows shows the OJDOS of SnO

2 polymorphs which gives the information on both interband and intraband contribution. It possesses one broad peak from approximately 3.6 to 20 eV for all the polymorphs.

A closer examination of the broad peak reveals multiple overlapping 7-15 eV, indicating more closely spaced optical states in this region for Pa , P42/mnm and Pnnm polymorphs. Pnnm polymorph has more available optical states. Pbcn, Pbca, Pnma and I4/m polymorphs possess comparably lower optical states. In addition, among the seven polymorphs, due to its indirect bandgap, Pbcn has a stronger intraband transition contribution. In general, the electronic energy levels include both vibrational and rotational states, which results in the fine structural splitting of spectra. Consequently, these overlapping states may consist of a combination of several vibrational and rotational modes. In addition, these states are all present in the ultraviolet spectral region.

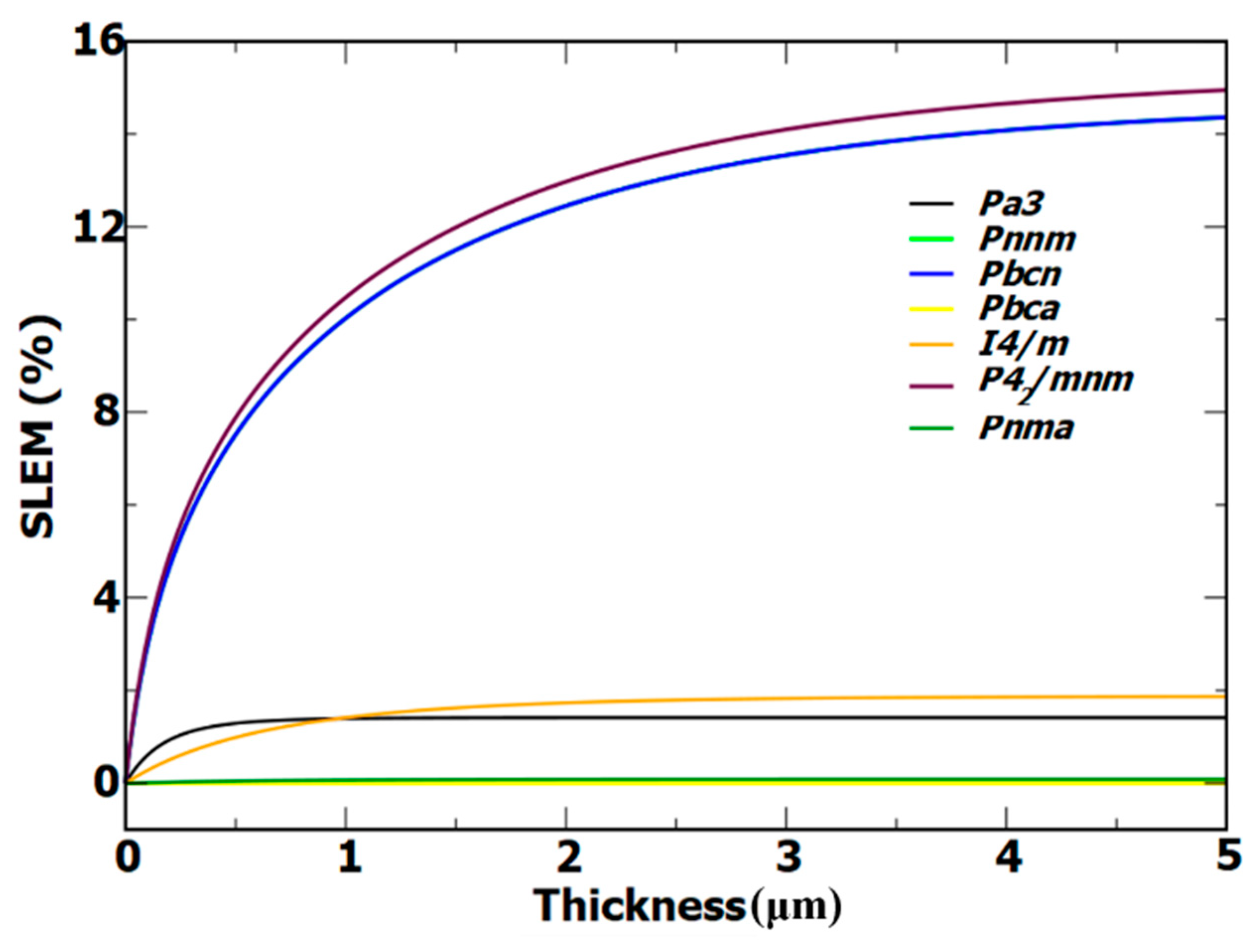

3.4. SLEM

We computed the SLME of the SnO

2 polymorphs as a function of film thickness, as shown in

Figure 7. Which gives the ratio between the maximum output power density and the total incident solar energy density. In the area of photovoltaics, the Shockley-Queisser (SQ) limit can be used to calculate absorber energy efficiency; this is essential. SQ limit offered for p-n junction PV absorbers efficiency limit by numerical calculation

42. SLME is also an important measure for evaluating the photovoltaic absorber capabilities of materials. The SLME incorporates the leading mechanics of absorption, emission and recombination characteristics, resolving a range of efficiencies for materials with the same gap. SLME of SnO

2 polymorphs can depend on the film thickness. However, there is no specific thickness at which the SLME is optimized, as it can vary depending on the specific polymorph and other factors such as the dopants used and the deposition method.

Chen et al. synthesized the SnO

2 thin films using a low-temperature solution processing method and evaluated their performance in terms of the SLME and overall photovoltaic performance. The authors found that the SnO

2 thin films had an SLME of 4.6 %, which was comparable to the SLME of TiO

2 and higher than that of ZnO. However, at a reference film thickness of 2 μm,

P42/mnm approaches 13 % efficiency and

Pnnm,

Pbcn approach 12.4 % efficiency. The efficiencies of the two polymorphs,

Pnnm and

Pbcn are comparable, to the efficiency of the experimental polymorph

P42/mnm. The polymorphs

I4/m,

Pa has 2 % and 1.4 % efficiency respectively hence these polymorphs were not suitable for the absorber layer. SLME efficiency of the polymorphs was listed in Table 5. The efficiency of SnO

2 polymorphs is comparable to that of organic solar cells.

P42/mnm, Pnnm and

Pbcn are excellent absorber layer materials for solar cells. These polymorphs efficiencies were comparable with chalcopyrite structures

43. Also, the perovskite solar cells Cs

8Ag

2Cu

2Bi

4Cl

24 efficiency differs from our calculated efficiency by 20 %

27.

Table 2.

Comparison of SLEM of SnO2 polymorphs at 2 μm thickness.

Table 2.

Comparison of SLEM of SnO2 polymorphs at 2 μm thickness.

| Polymorphs |

SLME (%) |

|

Pa

|

1.3 |

| P42/mnm |

13.3 |

| Pnnm (58) |

12.2 |

| Pbcn (60) |

0.1 |

| Pbca (61) |

12.2 |

| Pnma (62) |

0.1 |

| I4/m (87) |

1.8 |

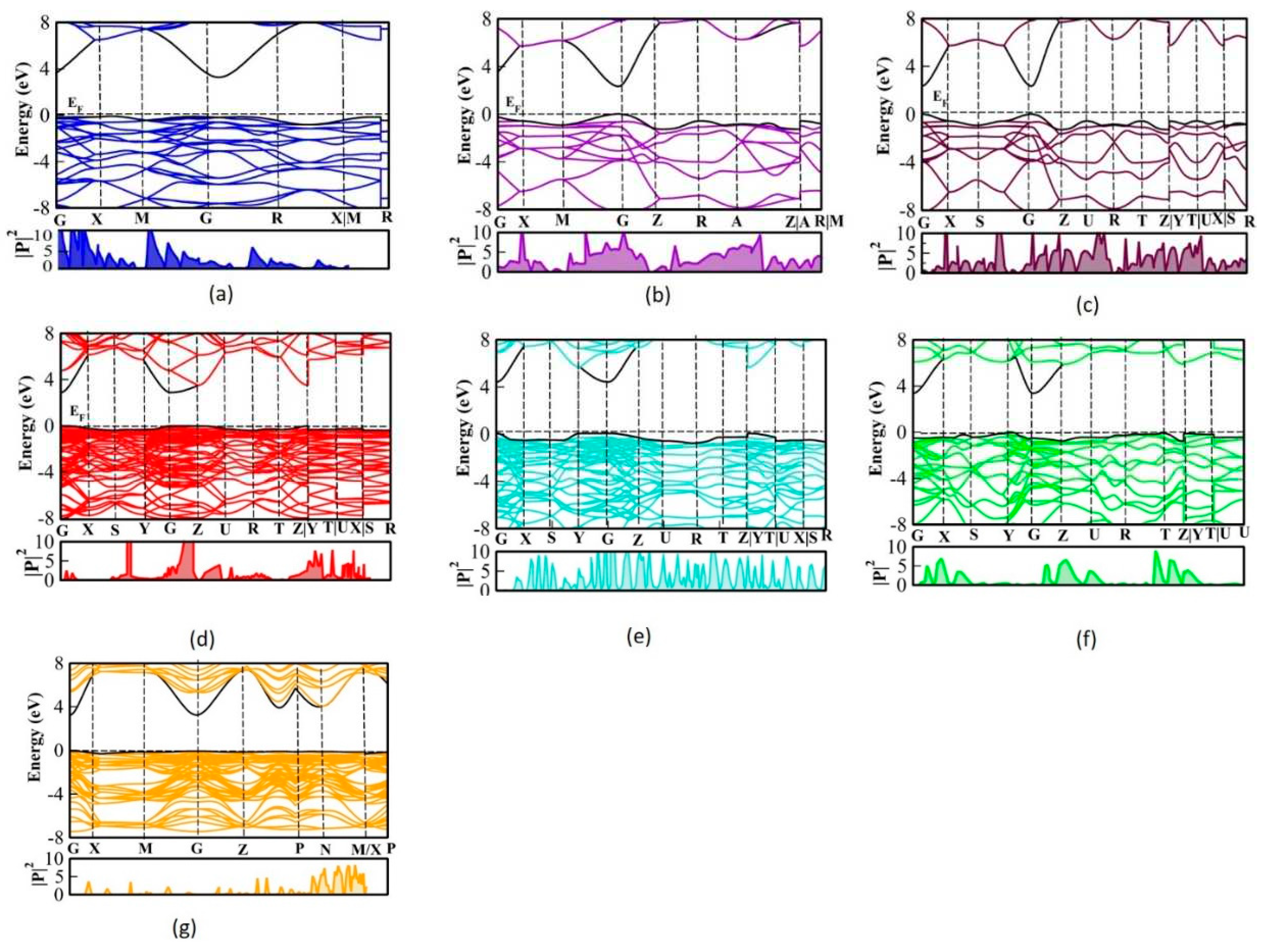

3.5. Transition dipole moment of SnO2 polymorphs

TDM anticipates the probability of transition from valence band states to conduction band states.

Figure 8, demonstrates the TDM of the SnO

2 polymorphs. The TDM of the polymorph Pa

shows the indirect transition from G-X and G-M hence the probability is dominant in this region. The polymorph

P42/mnm and

Pnnm have occurred direct transition at G so the probability at this point is predominant compared to other high symmetric points.

Pbcn and

Pbca have more number of atom in a unit cell hence the bands are dense, but TDM is different for these two polymorphs

Pbcn is indirect and

Pbca has a direct transition. In addition, at G-Z the TDM of

Pbcn has a strong transition probability. The plot reveals that the polymorph

Pnma is extremely directional dependent; hence, if this polymorph is formed as a crystal on a particular stable plane, it will become a photovoltaic material with high efficiency. But for

Pbca in all the planes the crystal will grow well it is directional independent. Also, the band is very narrow in these polymorphs so there are many peaks arises. From the

k-points Z-T, the conduction band is flat and the valance band is parabolic hence the peaks are sharp.

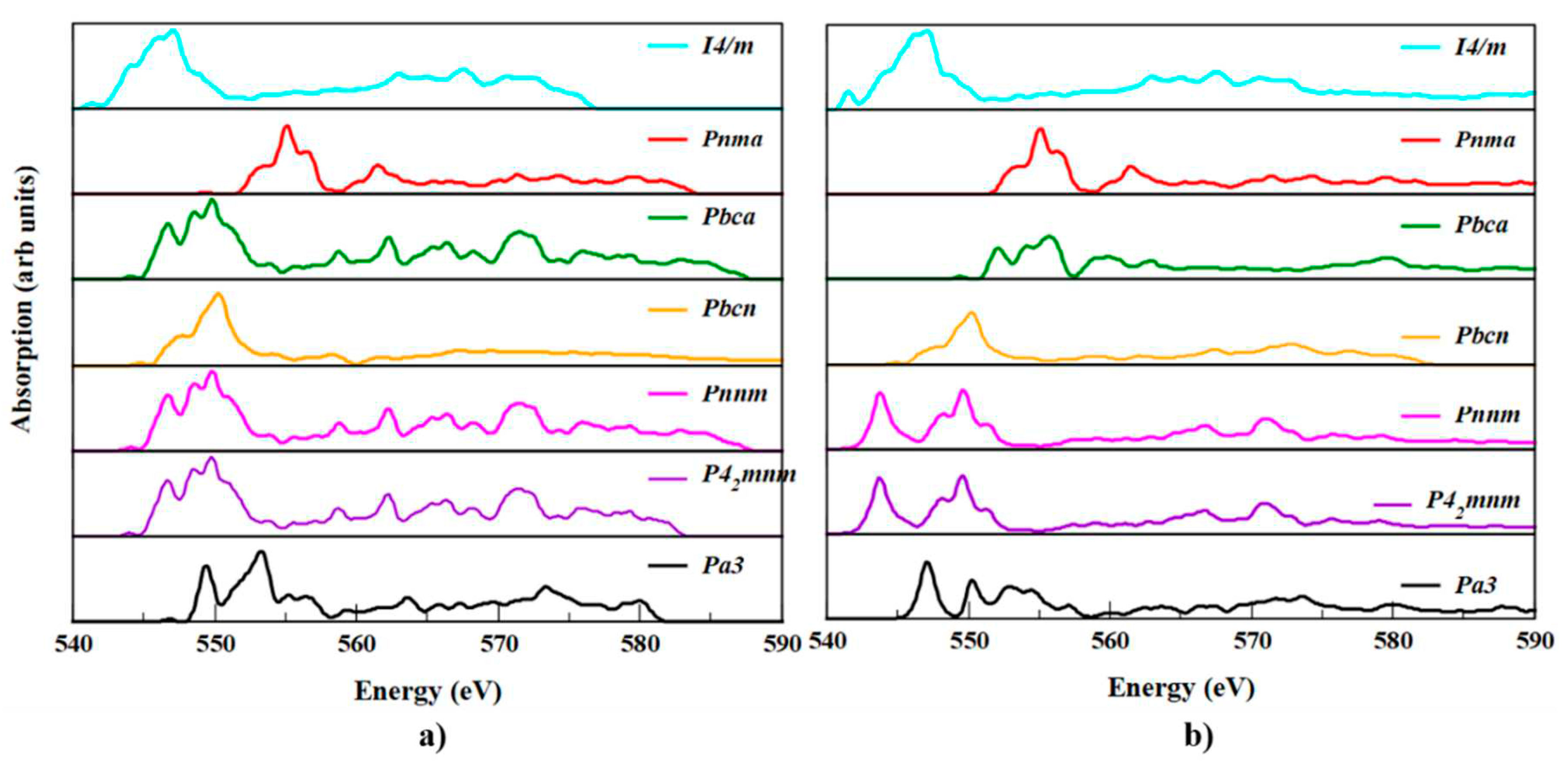

3.6. XANES spectra of SnO2 polymorphs

XANES is a powerful experimental technique used to study the local electronic and atomic structure of materials. However, the interpretation of XANES spectra can be complex and challenging due to the complex nature of the physical processes that occur during X-ray absorption. Therefore, computational methods such as DFT are often used to help interpret and analyze XANES spectra. XANES can be used to guide the design of new materials with specific electronic and atomic structures. Computational methods can help predict XANES spectra for hypothetical materials, which can then be used to guide the synthesis and characterization of new materials with desired properties. In the present work, we reported XANES for SnO

2 polymorphs for the first time.

Figure 9, shows a comparison between the calculated Sn-K edge and O-K edge spectra for SnO

2 polymorphs. From the XANES spectra, a comprehensive analysis of the electronic structure and geometry of the polymorphs was accomplished. The peaks at the k-edge of the metal in

Figure 9 (a), shows show an electronic transition from the Sn 3

d-core level to the 2

p state and the f state in the conduction band. Each polymorph has a unique bonding type, which may be deduced from the subtle but observable shift in the peaks.

Different types of local environments for Sn can be seen in the pre-edge XANES of SnO

2 polymorphs due to the separation of the peaks. Though

P42/mnm and

Pnnm polymorphs have similar spectra, the energy difference in the prominent peak was 0.01 eV. Except for

Pa and

Pnma polymorphs remaining, the polymorphs has three peak in the lower energy pre-edge region near 546, 548 and 548 eV due to increasing distortion of the octahedral environment of Sn with O. But for the

Pnma case it appears at 553, 554, 557 eV. The absorption edge of the

I4/m polymorph is 545 eV and we noticed from the spectra that the absorption edges of the seven SnO

2 polymorphs were not much deviated. The absorption edge of

Pmna is deviated from

P42/mnm by 0.9 %, which is the maximum deviated polymorph. Because of this, the Sn

4+ oxidation state predominates in all of the different polymorphs. Furthermore, distinct occupancy of tetrahedral and octahedral sites is possible in such phases during doping in the core polymorphs. Likewise,

Figure 9 (b), depicts the oxygen geometry of polymorphs.

4. Conclusion

This study is the first to investigate the optical characteristics of seven SnO2 polymorphs for their potential use as an energy material. The results obtained for the optical properties were summarized as follows.

The effective mass of electrons and holes in SnO2 polymorphs is affected by the crystal structure and orientation of the material. As a result, the effective mass can differ when measured along different axes. For instance, the P42/mnm and Pnnm polymorphs have lower effective mass compared to other polymorphs, making them more electronically conductive.

HSE06 is the best functional to describe the optical properties of these materials based on the findings.

The dielectric functions of the SnO2 polymorphs were analyzed and different polarization due to the anisotropy of the polymorphs was discovered, varying from 3 % to 11 % in the lower energy range, but it will not affect device fabrication.

The dielectric constants of the polymorphs I4/m and P42/mnm were found to be lower than TiO2, HfO2 and ZrO2, making them the best ETL material compared to other oxides.

The refractive index of the polymorphs was scattered from 1.5 to 1.8, making it a TCO in solar cells.

SnO2 polymorphs can be used as antireflective coatings due to their reflectance of less than 15 % in the infrared and visible spectral regions, especially the newly identified I4/m polymorph with more transparency than rutile.

The SLME efficiency of P42/mnm, Pnnm and Pbca polymorphs is comparable to AgGaSe2 and CuGaS2.

The XANES spectrum revealed structural differences between polymorphs, which can aid in their synthesis. The research on XANES is anticipated to help in the synthesis of many SnO2 polymorphs.

Author Contributions

Kanimozhi Balakrishnan: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Vasu Veerapandy: Supervision, Validation, Visualization. Vajeeston Ponniah: Data curation, Visualization, Investigation, Resources, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Research Council of Norway for providing the computer time (under the project number NN2875k and NS2875k) at the Norwegian supercomputer facility.

Conflicts of interest: The authors state that they have no known competing financial interests or personal ties that could appear to have influenced the work described in this article.

References

- Li, X.; Gessert, T.; DeHart, C.; Barnes, T.; Moutinho, H.; Yan, Y.; Young, D.; Young, M.; Perkins, J.; Coutts, T. Comparison of Composite Transparent Conducting Oxides Based on the Binary Compounds CdO and SnO2. NCPV Progr. Rev. Meet. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, B. G.; Paine, D. C. Applications and Processing of Transparent Conducting Oxides. MRS bulletin 2000, 25, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Nikiel, M.; Thomas, A. G.; Missous, M.; Lewis, D. J. A Novel and Potentially Scalable CVD-based Route Towards SnO2:Mo Thin Films as Transparent Conducting Oxides. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 15921–15936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biplab, S. R. I.; Ali, M.; Moon, M.; Alam, M.; Pervez, M.; Rahman, M.; Hossain, J. Performance Enhancement of CIGS-based Solar Cells by Incorporating an Ultrathin BaSi2 BSF layer. J. Comput. Electron. 2020, 19, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, L. R.; Braga, M.; Campos, R. A.; Naspolini, H. F.; Ruther, R. Performance Assessment of Solar Photovoltaic Technologies Under Different Climatic Conditions in Brazil. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 1070–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vats, K.; Tomar, V.; Tiwari, G. N. ; Effect of Packing Factor on the Performance of a Building Integrated Semitransparent Photovoltaic Thermal (BISPVT) System with Air Duct. Energy Build. 2012, 53, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Mende, L.; Dyakonov, V.; Olthof, S.; Unlu, F.; Le, K. M. T.; Mathur, S.; Karabanov, A. D.; Lupascu, D. C.; Herz, L. M.; Hinderhofer, A.; Schreiber, F. Roadmap on Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Perovskite Semiconductors and Devices. APL Mater. 2021, 9, 109202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riente, P.; Noel, T. Application of Metal Oxide Semiconductors in Light-driven Organic Transformations. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 5186-5232.Mak, K. F.; Shan, J. Photonics and Optoelectronics of 2D Semiconductor Transition Metal Dichalcogenides. Nat. Photonics 2016, 10, 216-226.

- Lee, J. Y.; Shin, J. H.; Lee, G. H.; Lee, C. H. Two-Dimensional Semiconductor Optoelectronics Based on Van der Waals Heterostructures. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonu, V.; Gupta, B.; Chandra, S.; Das, A.; Dhara, S.; Tyagi, A. K. Electrochemical Supercapacitor Performance of SnO2 Quantum Dots. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 203, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, R.; Rehman, S. U.; Butt, F. K.; Ul Haq, B.; Aleem, F. Elucidating the First-Principles Calculations of SnO2 within DFT Framework and Beyond: A Library for Optimization of Various Pseudopotentials. Silicon 2018, 10, 2317–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, W. Density Functional Theory Study on the Electronic Structure and Optical Properties of SnO2. Xiyou Jinshu Cailiao Yu Gongcheng/Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2015, 44, 2409–2414. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, J. T.; Mayengbam, R.; Tripathy, S. K. Theoretical Investigation on Structural, Electronic, Optical and Elastic Properties of TiO2, SnO2, ZrO2 and HfO2 using SCAN meta-GGA Functional: A DFT Study. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 254, 123474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloufa, N.; Cherchab, Y.; Louhibi-Fasla, S.; Daoud, S.; Rekab-Djabri, H.; Chahed, A. Theoretical Investigation of Structural, Electronic and Optical Properties of Sc-Doped SnO2. Comput. Condens. Matter 2022, 30, e00642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, A.; Afaq, A.; Latif, S.; Iftikhar, A.; Asif, M. A Comprehensive Study of Titanium-doped Tin Oxide Rutile for Structural and Optical Properties. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2021, 619, 413210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetri, P.; Basyach, P.; Choudhury, A. Structural, Optical and Photocatalytic Properties of TiO2/SnO2 and SnO2/TiO2 Core-Shell Nanocomposites: An Experimental and DFT Investigation. Chem. Phys. 2014, 434, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Liu, S.; Zhang, F. Electronic Structure and Optical Properties of Cu-doped SnO2. Ferroelectrics 2019, 547, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, B. M.; Chandra, D. B.; Jiban, P.; Nurul, I.; Abdullah, Z. Influence of Fe2+/Fe3+ Ions in Tuning the Optical Band Gap of SnO2 Nanoparticles Synthesized by TSP Method: Surface Morphology, Structural and Optical Studies. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2019, 89, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Hou, Q.; Liu, Q. First-Principle Study on the Magnetic and Optical Properties of SnO2 Doped with Fe2+/Fe3+ and Oxygen Vacancies at Different Ratios. Chem. Phys. 2021, 542, 111072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching-Prado, E.; Watson, A.; Miranda, H. Optical and Electrical Properties of Fluorine Doped Tin Oxide Thin Film. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 15299–15306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M. Ab Initio Calculations of the Effect of N, Nb and Ta Doping on the Electronic Structure and Optical Properties of SnO2. J. Comput. Electron. 2020, 19, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, K.; Veerapandy, V.; Fjellvag, H.; Vajeeston, P. First-Principles Exploration into the Physical and Chemical Properties of Certain Newly Identified SnO2 Polymorphs. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 10382–10393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J. Y.; Park, J.; Kim, H. Y.; Kim, H. S.; Park, J. S. Facile Route to the Controlled Synthesis of Tetragonal and Orthorhombic SnO2 Films by Mist Chemical Vapor Deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 12074–12079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birrozzi, A.; Mullaliu, A.; Eisenmann, T.; Asenbauer, T.; DCiemant, T.; Geiger, D. Kaiser, U.; Oliveira de Souza, D.; Ashton, T. E.; Groves, A. R.; Darr. J. A.Synergistic Effect of Co and Mn Co-Doping on SnO2 Lithium-Ion Anodes. Inorganics 2022, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivkovic, A.; Farkas, B.; Uahengo, V.; De Leeuw, N. H.; Dzade, N. Y. First-Principles DFT Insights into the Structural, Elastic and Optoelectronic Properties of α and β-ZnP2: Implications for Photovoltaic Applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2019, 31, 265501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, D.; Bhumla, P.; Kumar, M.; Bhattacharya, S. High-throughput Screening to Modulate Electronic and Optical Properties of Alloyed Cs2AgBiCl6 for Enhanced Solar Cell Efficiency. J. Phys Mater. 2021, 4, 025005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C. H.; Leung, C. W. The Convolution Equation of Choquet and Deny on [IN]-Groups. Integr. Equations Oper. Theory 2001, 40, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Kurti, J.; Rajczy, P.; Kertesz, M.; Hafner, J.; Kreese, G. Performance of the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP). J. Mol. Struct. 2003, 624, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagadevan, S.; Podder, J. Optical and Electrical Properties of Nanocrystalline SnO2 thin Films Synthesized by Chemical Bath Deposition Method. Soft Nanosci. Lett. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paier, J.; Marsman, M.; Kresse, G. Dielectric Properties and Excitons for Extended Systems from Hybrid Functionals. Phys. Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2008, 78, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, V.; Xu, N.; Liu, J. C.; Tang, G.; Geng, W. T. VASPKIT: A User-Friendly Interface Facilitating High-throughput Computing and Analysis Using VASP code. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2021, 267, 108033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Zeng, W.; Tang, H.; Wang, L. X.; Liu, F. S.; Tang, B.; Liu, Q. J. Band Structures, Effective Masses and Exciton Binding Energies of Perovskite polymorphs of CH3NH3PbI3. Sol. Energy 2019, 190, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmale, N.; Chaudhury, S.; Mahamune, R.; Dash, D. Comparative Study on Structural, Electronic, Optical and Mechanical Properties of Normal and High-Pressure Phases Titanium Dioxide Using DFT. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 054004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, P.; Liu, J.; Yu, J. New Understanding of the Difference of Photocatalytic Activity Among Anatase, Rutile and Brookite TiO2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 20382–20386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonsad-SnO2 mass-PRB1971.

- Asuda, S.; Hosokawa, S.; Tochizawa, I.; Akutsu, K.; Kuwano, K.; Iwata, A. Surface Treatment of Plastic Material by Pulse Corona Induced Plasma Chemical Process-PPCP. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1994, 30, 377–380. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gajdos, M.; Hummer, K.; Kresse, G.; Furthmuller, J.; Bechstedt, F. Linear Optical Properties in the Projector-Augmented Wave Methodology. Phys. Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2006, 73, 1-9.

- Rasukkannu, M.; Velauthapillai, D.; Vajeeston, P. Hybrid Density Functional Study of Au2Cs2I6, Ag2GeBaS4, Ag2ZnSnS4 and AgCuPO4 for the Intermediate Band Solar Cells. Energies 2018, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasukkannu, M.; Velauthapillai, D.; Vajeeston, P. A First-Principle Study of the Electronic, Mechanical and Optical Properties of Inorganic Perovskite Cs2SnI6 for Intermediate-Band Solar Cells. Mater. Lett. 2018, 218, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaibi, K.; Benhaliliba, M.; Ayeshamariam, A. Computational Assessment and Experimental Study of Optical and Thermoelectric Properties of Rutile SnO2 Semiconductor. Superlattices Microstruct. 2021, 155, 106923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, W.; Queisser, H. J. Detailed Balance Limit of Efficiency of p-n Junction Solar Cells. J. Appl. Phys. 1961, 32, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, W.; Queisser, H. J. Detailed Balance Limit of Efficiency of p-n Junction Solar Cells. J. Appl. Phys. 1961, 32, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anne Knorr, Koichi Fumino, Anne-Marie Bonsa and Ralf Ludwig Spectroscopic evidence of cholinium ‘jumping and pecking’ and H-bond enhanced cation-cation interaction in ionic liquids. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).