Submitted:

10 July 2023

Posted:

12 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

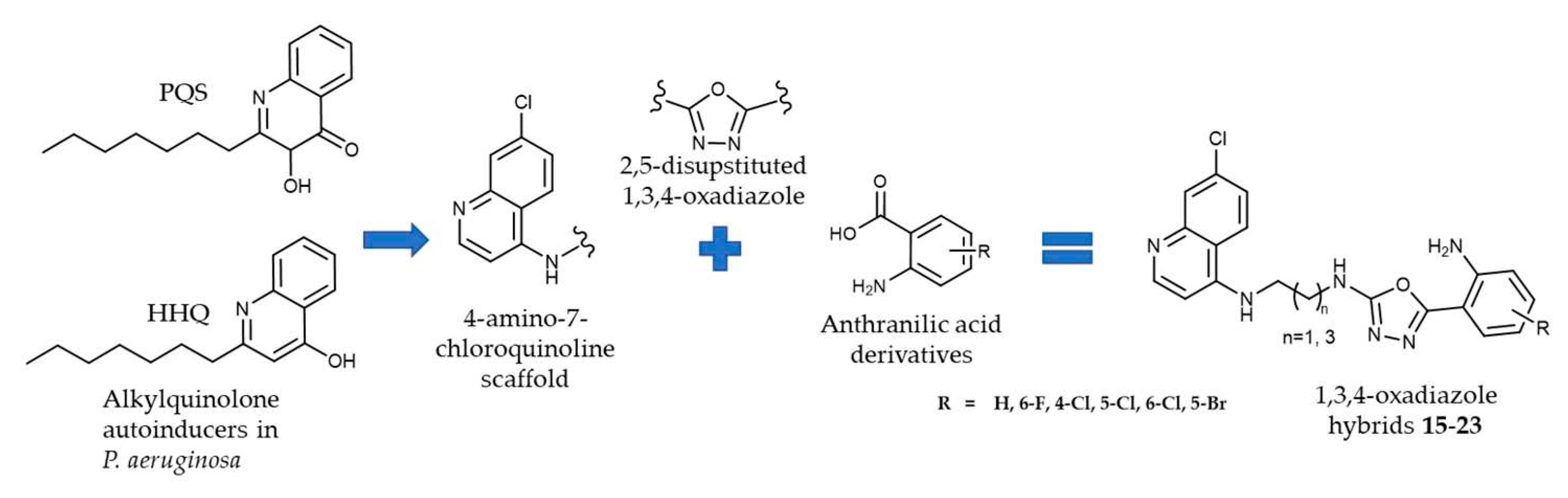

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

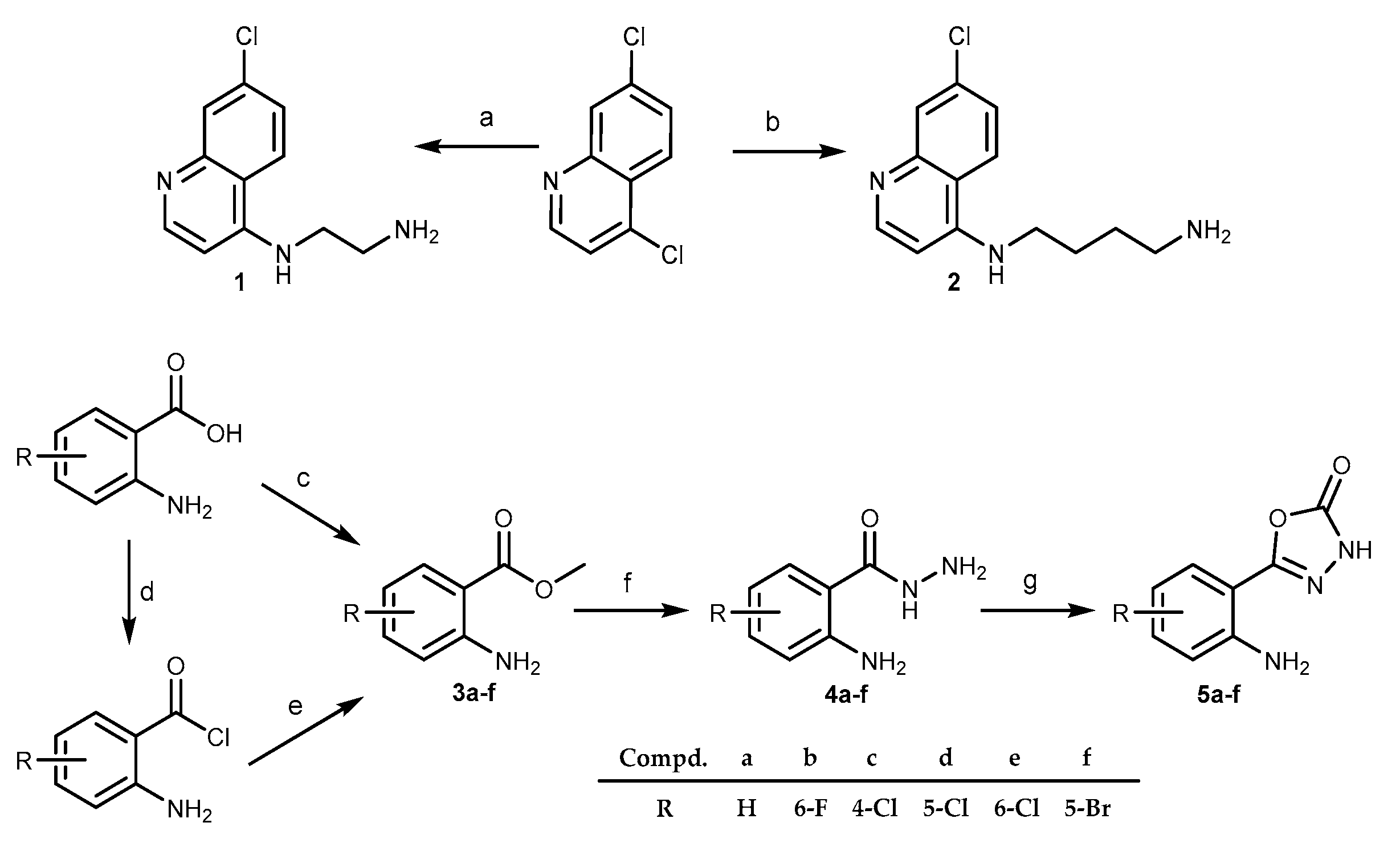

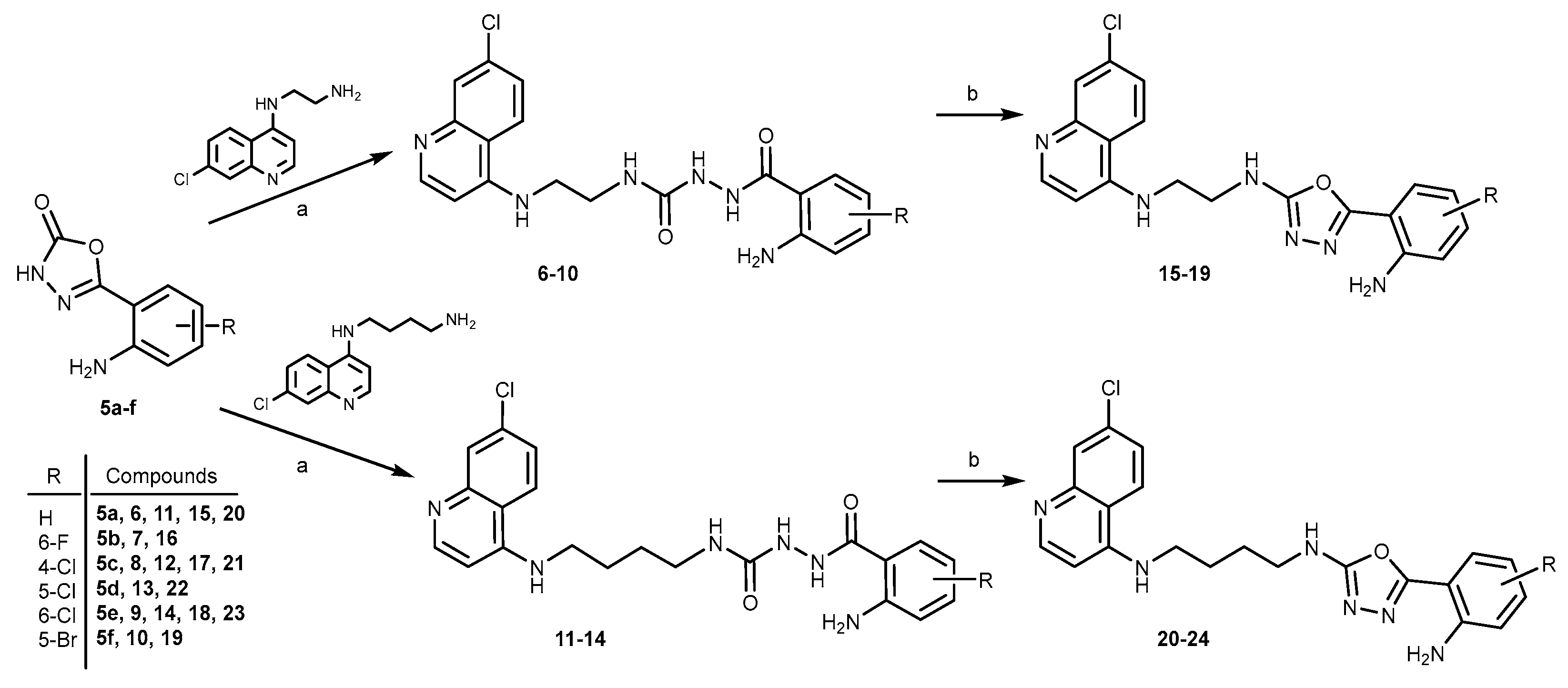

2.1. Chemistry

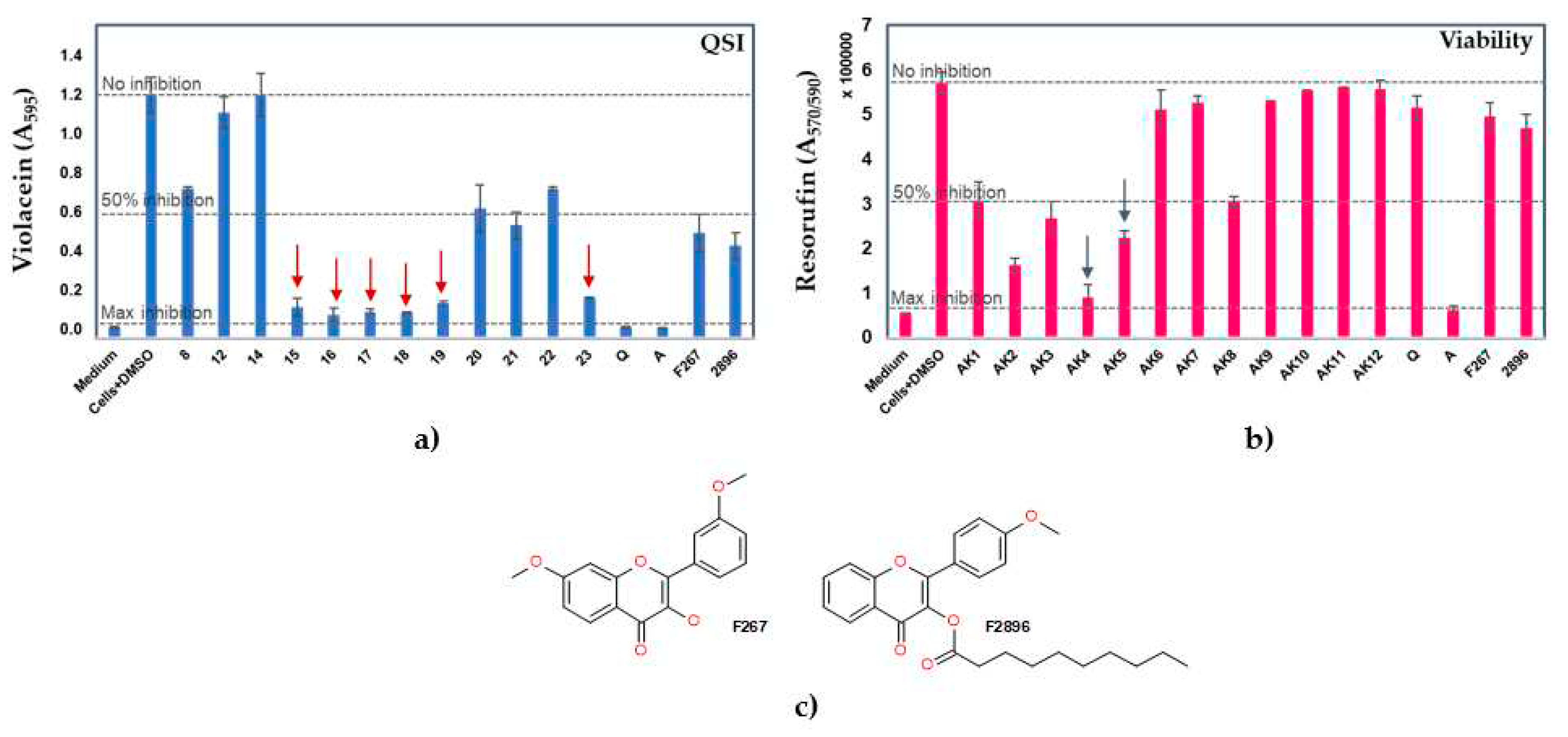

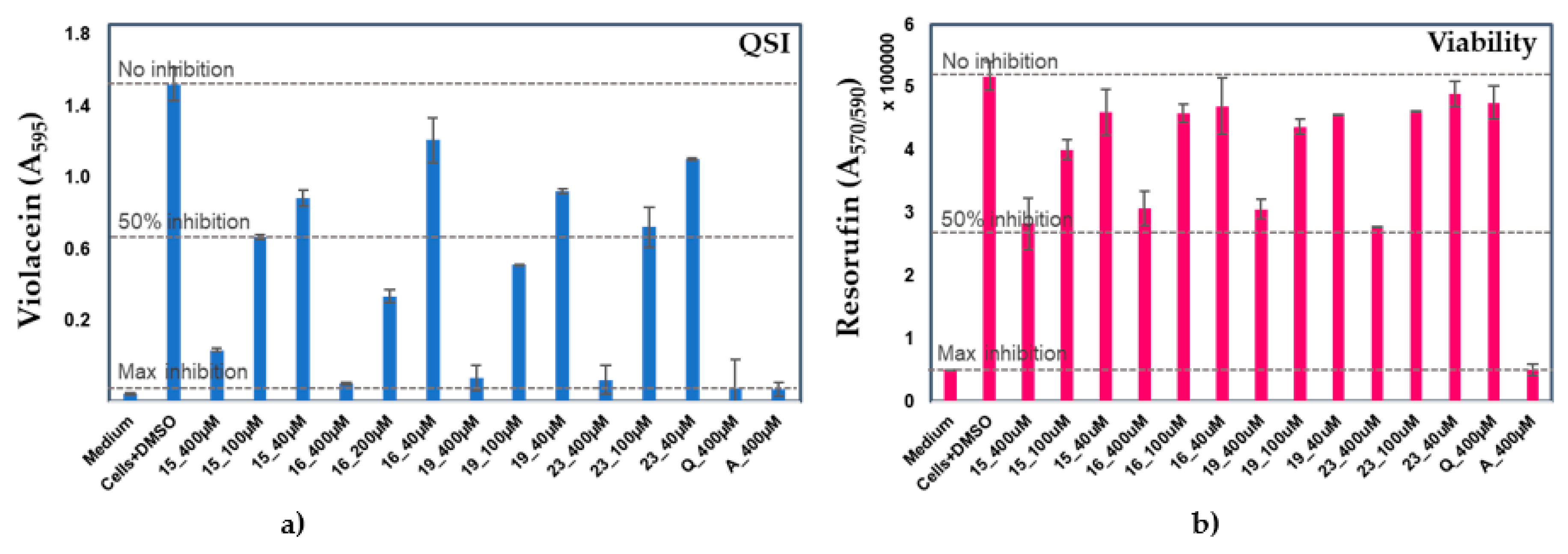

2.2. Anti-QS and bactericidal activity against the QS-reporter strain

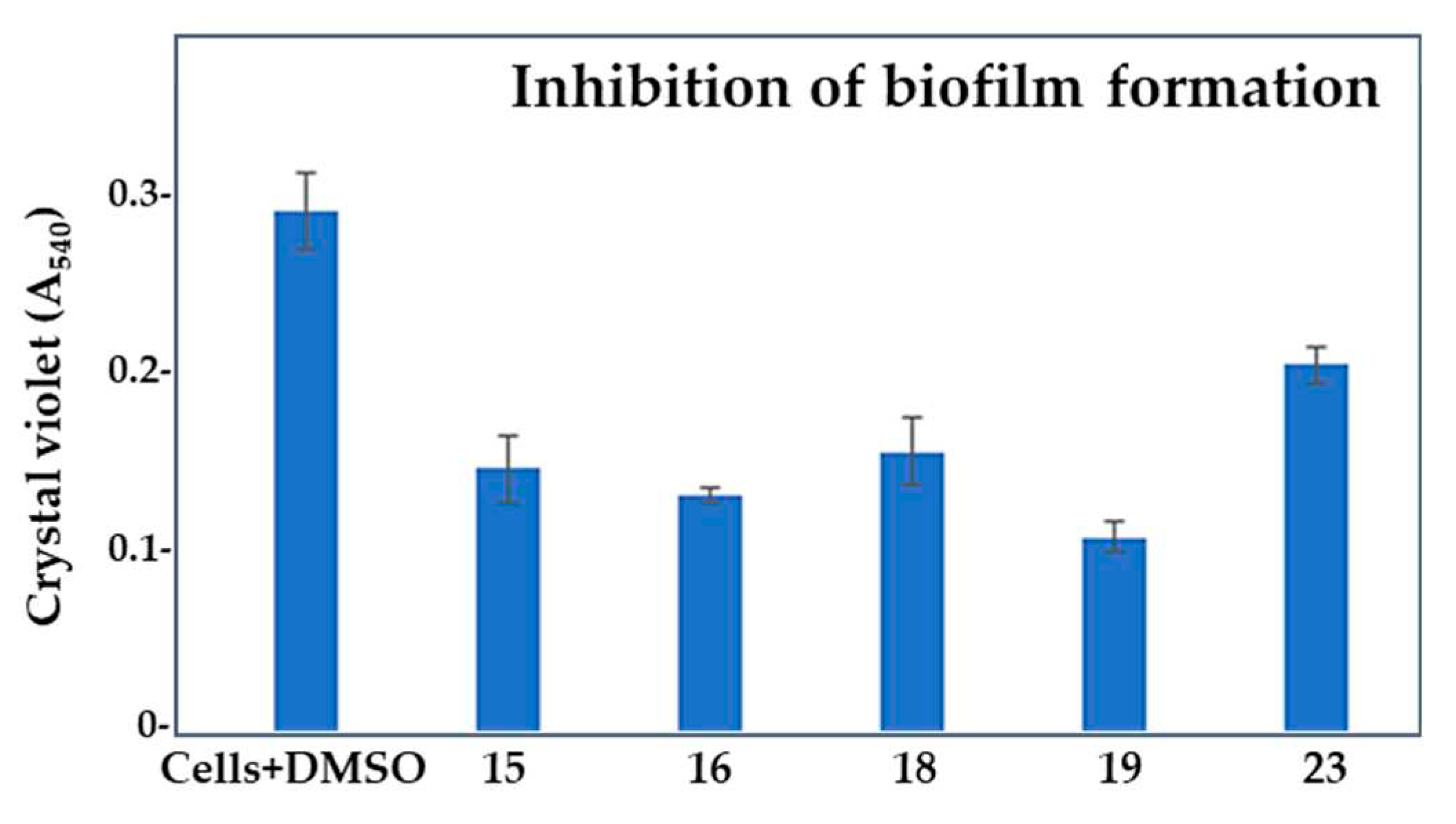

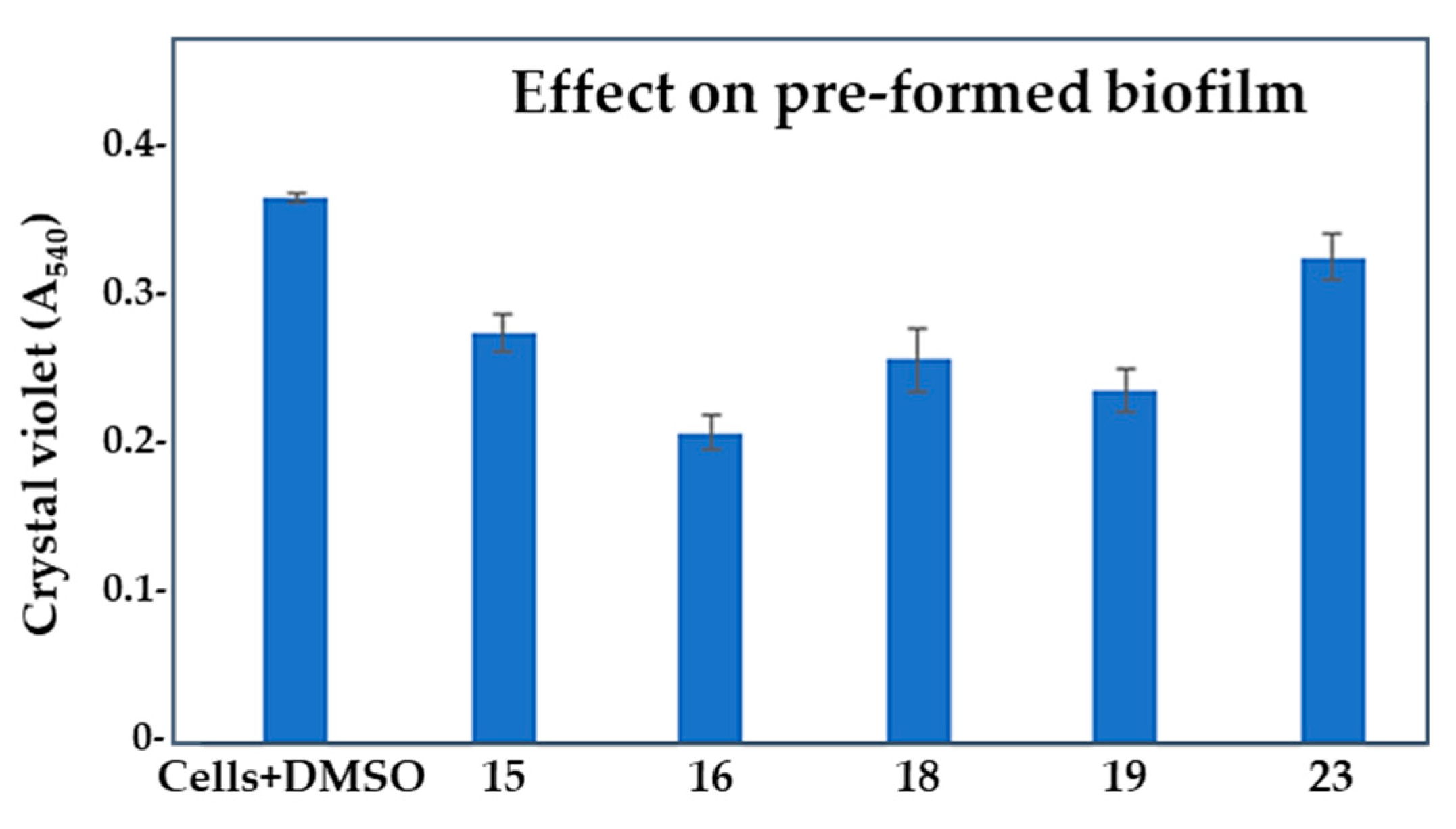

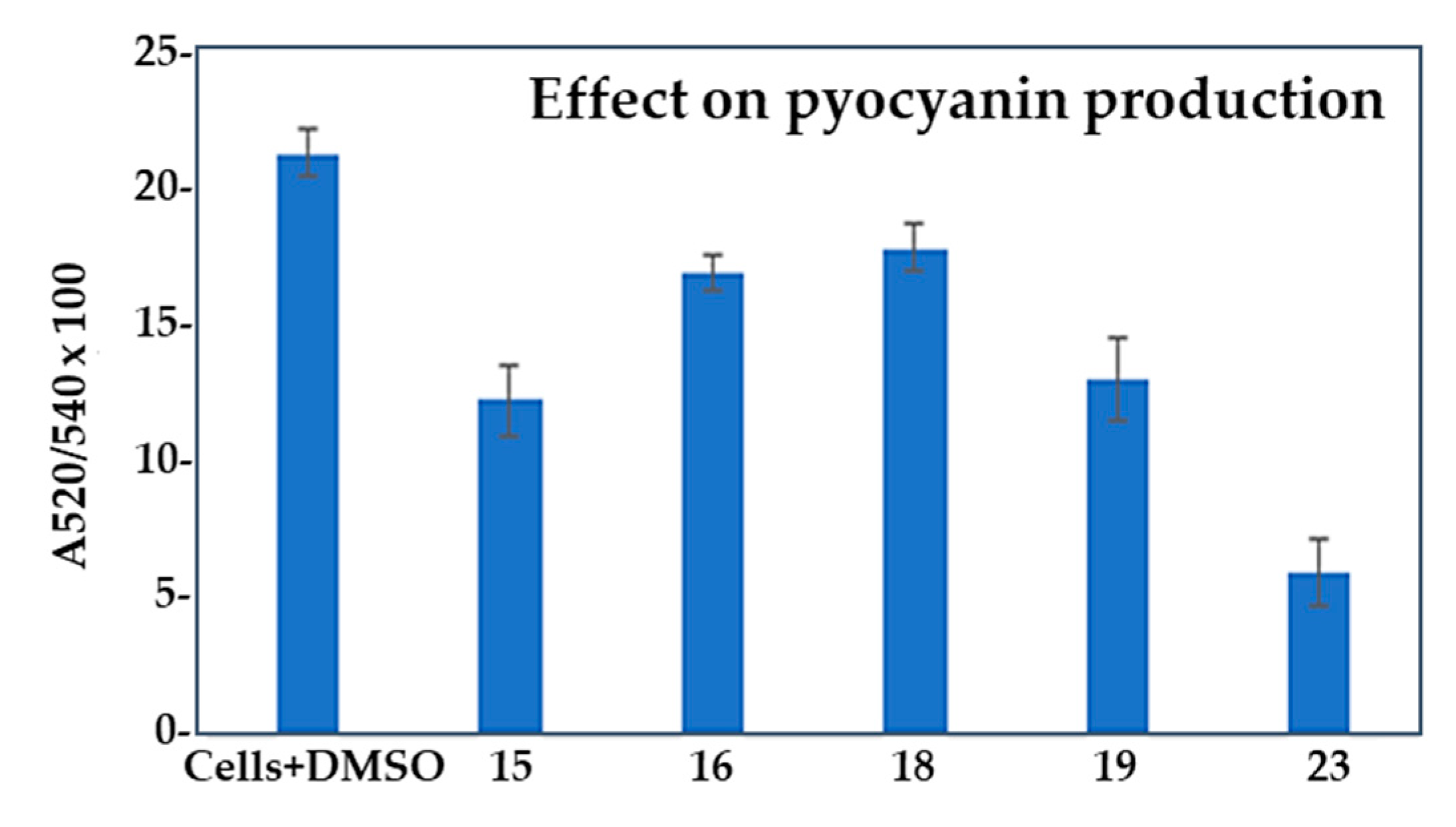

2.3. Effect of selected compounds on biofilm and pyocyanin production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. General information

3.1.1. Synthesis of 4-amino-7-chloroquinoline intermediates 1 and 2

3.1.2. Synthesis of methyl anthranilates 3 and hydrazides 4.

3.1.3. General procedure for the synthesis of 5-(2-aminophenyl)-l,3,4-oxadiazole-2(3H)-ones 5a–f

3.1.4. General procedure for the synthesis of acylsemicarbazides (6–10)

3.1.5. General procedure for the synthesis of acylsemicarbazides (11-14)

3.1.6. General procedure for the synthesis of oxadiazoles (15-19)

3.1.7. General procedure for the synthesis of oxadiazoles (20–23)

3.2. Anti-QS and bactericidal activity screening

3.3. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

3.4. Anti-biofilm assay

3.5. Effect on pyocyanin production

3.6. Statistical analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rasko, D.; Sperandio, V. Anti-virulence strategies to combat bacteria-mediated disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010, 9, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 625–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, N.K.; Teng, C.; Frei, C.R. Brief Overview of Approaches and Challenges in New Antibiotic Development: A Focus On Drug Repurposing. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 684515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilangovan, A.; Fletcher, M.; Rampioni, G.; Pustelny, C.; Rumbaugh, K.; Heeb, S.; Cámara, M.; Truman, A.; Chhabra, S.R.; Emsley, J.; Williams, P. Structural Basis for Native Agonist and Synthetic Inhibitor Recognition by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Quorum Sensing Regulator PqsR (MvfR). PLOS Pathogens 2013, 9, e1003508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickey, S.; Cheung, G.; Otto, M. Different drugs for bad bugs: antivirulence strategies in the age of antibiotic resistance. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017, 16, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perković, I.; Raić-Malić, S.; Fontinha, D.; Prudêncio, M.; Pessanha de Carvalho, L.; Held, J.; Tandarić, T.; Vianello, R.; Zorc, B.; Rajić, Z. Harmicines − harmine and cinnamic acid hybrids as novel antiplasmodial hits. Eur J Med Chem 2019, 187, 111927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinović, M.; Perković, I.; Fontinha, D.; Prudêncio, M.; Held, J.; de Carvalho, L.P.; Tandarić, T.; Vianello, R.; Zorc, B.; Rajić, Z. Novel Harmicines with Improved Potency against Plasmodium. Molecules 2020, 25, 4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinović, M.; Poje, G.; Perković, I.; Fontinha, D.; Prudêncio, M.; Held, J.; de Carvalho, L.P.; Tandarić, T.; Vianello, R.; Rajić, Z. Further investigation of harmicines as novel antiplasmodial agents: Synthesis, structure-activity relationship and insight into the mechanism of action. Eur J Med Chem 2021, 224, 113687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poje, G.; de Carvalho, L.P.; Held, J.; Moita, D.; Prudêncio, M.; Perković, I.; Tandarić, T.; Vianello, R.; Rajić, Z. Design and synthesis of harmiquins, harmine and chloroquine hybrids as potent antiplasmodial agents. Eur J Med Chem 2022, 238, 114408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poje, G.; Marinović, M.; Pavić, K.; Mioč, M.; Kralj, M.; de Carvalho, L.P.; Held, J.; Perković, I.; Rajić, Z. Harmicens, Novel Harmine and Ferrocene Hybrids: Design, Synthesis and Biological Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 9315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavić, K.; Beus, M.; Poje, G.; Uzelac, L.; Kralj, M.; Rajić, Z. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Harmirins, Novel Harmine–Coumarin Hybrids as Potential Anticancer Agents. Molecules 2021, 26, 6490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutty, S.K.; Barraud, N.; Ho, K.K.K.; Iskander, G.M.; Griffith, R.; Rice, S.A.; Bhadbhade, M.; Willcox, M.D.P.; Black, D.S.; Kumar, N. Hybrids of acylated homoserine lactone and nitric oxide donors as inhibitors of quorum sensing and virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Org Biomol Chem 2015, 13, 9850–9861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, S.A.; Lindsey, E.A.; Whitehead, D.C.; Mullikin, T.; Melander, C. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 2-aminoimidazole/carbamate hybrid anti-biofilm and anti-microbial agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2011, 21, 1257–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minvielle, M.J.; Bunders, C.A.; Melander, C. Indole/triazole conjugates are selective inhibitors and inducers of bacterial biofilms. MedChemComm 2013, 4, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksić, I.; Šegan, S.; Andrić, F.; Zlatović, M.; Moric, I.; Opsenica, D.M.; Senerovic, L. Long-Chain 4-Aminoquinolines as Quorum Sensing Inhibitors in Serratia marcescens and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ACS Chem Biol 2017, 12, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Kirsch, B.; Zimmer, C.; de Jong, J.C.; Henn, C.; Maurer, C.K.; Müsken, M.; Häussler, S.; Steinbach, A.; Hartmann, R.W. Discovery of antagonists of PqsR, a key player in 2-alkyl-4-quinolone-dependent quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chem Biol 2012, 19, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Kirsch, B.; Maurer, C.K.; de Jong, J.C.; Braunshausen, A.; Steinbach, A.; Hartmann, R.W. Optimization of anti-virulence PqsR antagonists regarding aqueous solubility and biological properties resulting in new insights in structure–activity relationships. Eur J Med Chem 2014, 79, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.H.; She, M.T.; Zhang, Y.H.; Liu, Y.F.; Zhong, D.X.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zheng, J.X.; Sun, N.; Wong, W.L.; Lu, Y.J. Novel quinoline-based derivatives as the PqsR inhibitor against Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Appl Microbiol. 2022, 133, 2167–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beus, M.; Savijoki, K.; Patel, J.Z.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J.; Fallarero, A.; Zorc, B. Chloroquine fumardiamides as novel quorum sensing inhibitors. Biorg Med Chem Lett 2020, 30, 127336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzgall, F.; Ewert, W.; Blankenfeldt, W. Structures of the N-Terminal Domain of PqsA in Complex with Anthraniloyl- and 6-Fluoroanthraniloyl-AMP: Substrate Activation in Pseudomonas Quinolone Signal (PQS) Biosynthesis. ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 2045–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Sharma, I.; Pratihar, D.; Hudson, L.L.; Maura, D.; Guney, T.; Rahme, L.G.; Pesci, E.C.; Coleman, J.P.; Tan, D.S. Designed Small-Molecule Inhibitors of the Anthranilyl-CoA Synthetase PqsA Block Quinolone Biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ACS Chem Biol 2016, 11, 3061–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesic, B.; Lépine, F.; Déziel, E.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Padfield, K.; Castonguay, M.H.; Milot, S.; Stachel, S.; Tzika, A.A.; Tompkins, R.G.; Rahme, L.G. Inhibitors of pathogen intercellular signals as selective anti-infective compounds. PLoS Pathog 2007, 3, 1229–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütz, C.; Empting, M. Targeting the Pseudomonas quinolone signal quorum sensing system for the discovery of novel anti-infective pathoblockers. Beilstein J Org Chem 2018, 15, 2627–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalia, V.C. Quorum sensing inhibitors: an overview. Biotechnol Adv 2013, 31, 224–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calfee, M.W.; Coleman, J.P.; Pesci, E.C. Interference with Pseudomonas quinolone signal synthesis inhibits virulence factor expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 11633–11637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beus, M.; Persoons, L.; Daelemans, D.; Schols, D.; Savijoki, K.; Varmanen, P.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J.; Pavić, K.; Zorc, B. Anthranilamides with quinoline and β-carboline scaffolds: design, synthesis, and biological activity. Mol Divers 2022, 26, 2595–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, S.W.; Asfahl, K.L.; Dandekar, A.A.; Greenberg, E.P. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Quorum Sensing. Adv Exp Med Biol 2022, 1386, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, K.H.; Winson, M.K.; Fish, L.; Taylor, A.; Chhabra, S.R.; Camara, M.; Daykin, M.; Lamb, J.H.; Swift, S.; Bycroft, B.W.; Stewart, G.S.A.B.; Williams, P. Quorum sensing and Chromobacterium violaceum: expression of violacein production and inhibition for the detection of N-acyl homoserine lactones. Microbiology 1997, 143, 3703–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauff, D.L.; Bassler, B.L. Quorum sensing in Chromobacterium violaceum: DNA recognition and gene regulation by the CviR receptor. J Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 3871–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Monapara, J.; Jethawa, A.; Khedkar, V.; Shingate, B. Oxadiazole: A highly versatile scaffold in drug discovery. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2022, 355, e2200123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, J.; Hogner, A.; Llinàs, A.; Wellner, E.; Plowright, A.T. Oxadiazoles in medicinal chemistry. J Med Chem 2012, 55, 1817–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, Z. Applications of amide isosteres in medicinal chemistry. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2019, 29, 2535–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavić, K.; Rajić, Z.; Mlinarić, Z.; Uzelac, L.; Kralj, M.; Zorc, B. Chloroquine Urea Derivatives: Synthesis and Antitumor Activity in Vitro. Acta Pharm 2018, 68, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meunier, B.; Robert, A.; Dechy-Cabaret, O.; Benoit-Vical, F. Dual Molecules Containing a Peroxide Derivative, Synthesis and Therapeutic Applications thereof. U. S. Pat. 20040038957A1, 26 Feb 2004. U. S. Pat 20040038957A1, 26 Feb 2004. [Google Scholar]

- El-Azzounyl, A.A.; Maklad, Y.A.; Bartsch, H.; Zaghary, W.A.; Ibrahim, W.M.; Mohamed, M.S. Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of Fenamate Analogues: 1,3,4-Oxadiazol-2-ones and 1,3,4-Oxadiazole-2-thiones. Sci Pharm 2003, 71, 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.S. The preparation of 5-(2-aminophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole-2(3H)-one and its rearrangement to 3-amino-2,4(1H,3H)-quinazolinedione. Monatsh Chem 1984, 115, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, R. Tertiary Phosphane/Tetrachloromethane, a Versatile Reagent for Chlorination, Dehydration, and P-N Linkage. Angew Chem int Ed Engl 1975, 14, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumčiūtė, J.; Martynaitis, V.; Holzer, W.; Mangelinckx, S.; De Kimpe, N.; Šačkus, A. Synthesis and ring transformations of 1-amino-1,2,3,9a-tetrahydroimidazo[1,2-a]indol-2(9H)-ones. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 3309–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilangovan, A.; Saravanakumar, S.; Umesh, S. T3P as an efficient cyclodehydration reagent for the one-pot synthesis of 2-amino-1,3,4-oxadiazoles. J Chem Sci 2015, 127, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogman, M.E.; Kanerva, S.; Manner, S.; Vuorela, P.M.; Fallarero, A. Flavones as quorum sensing inhibitors identified by a newly optimized screening platform using Chromobacterium violaceum as reporter bacteria. Molecules 2016, 21, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manner, S.; Fallarero, A. Screening of natural product derivatives identifies two structurally related flavonoids as potent quorum sensing inhibitors against Gram-negative bacteria. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, J.; Wilson, I.; Orton, T.; Pognan, F. Investigation of the Alamar Blue (resazurin) fluorescent dye for the assessment of mammalian cell cytotoxicity. Eur J Biochem. 2000, 267, 5421–5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluyombo, O.; Penfold, C.N.; Diggle, S.P. Competition in Biofilms between Cystic Fibrosis Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Is Shaped by R-Pyocins. mBio 2019, 10, e01828–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Zhang, L. The hierarchy quorum sensing network in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Protein Cell 2015, 6, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.V.; Mah, T.-F. Molecular mechanisms of biofilm-based antibiotic resistance and tolerance in pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol 2017, 41, 276–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, H.; Allan, R.N.; Howlin, R.P.; Stoodley, P.; Hall-Stoodley, L. Targeting microbial biofilms: current and prospective therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol 2017, 15, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciofu, O.; Moser, C.; Jensen, P.Ø. Tolerance and resistance of microbial biofilms. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022, 20, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, K.H.; Winson, M.K.; Fish, L.; Taylor, A.; Chhabra, S.R.; Camara, M.; Daykin, M.; Lamb, J.H.; Swift, S.; Bycroft, B.W.; Stewart, G.S.; Williams, P. Quorum sensing and Chromobacterium violaceum: exploitation of violacein production and inhibition for the detection of N-acylhomoserine lactones. Microbiology 1997, 143, 3703–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopu, V.; Meena, C.K.; Shetty, P.H. Quercetin Influences Quorum Sensing in Food Borne Bacteria: In-Vitro and In-Silico Evidence. PLoS One 2015, 6, e0134684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg, M.E.; Schellmann, D.; Brunhofer, G.; Erker, T.; Busygin, I.; Leino, R.; Vuorela, P.M.; Fallarero, A. Pros and cons of using resazurin staining for quantification of viable Staphylococcus aureus biofilms in a screening assay. J Microbiol Methods 2009, 78, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerin, T.F.; Mondido, M.; McClenn, B.; Peasley, B. Application of resazurin for estimating abundance of contaminant-degrading micro-organisms. Lett Appl Microbiol 2001, 32, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Chung, T.D.; Oldenburg, K.R. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J Biomol Screen 1999, 4, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollini, S.; Herbst, J.J.; Gaughan, G.T.; Verdoorn, T.A.; Ditta, J.; Dubowchik, G.M.; Vinitsky, A.J. High-throughput fluorescence polarization method for identification of FKBP12 ligands. Biomol Screen 2002, 7, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegand, I.; Hilpert, K.; Hancock, R.E. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat Protoc 2008, 3, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Toole, G.A. Microtiter Dish Biofilm Formation Assay. J Vis Exp 2011, 47, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essar, D.W.; Eberly, L.; Hadero, A.; Crawford, I.P. Identification and characterization of genes for a second anthranilate synthase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: interchangeability of the two anthranilate synthases and evolutionary implications. J Bacteriol 1990, 172, 884–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compd. | QSI (%) | Bactericidal effect (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | 38.6 ± 0.9 | 7.2 ± 0.0 |

| 12 | ne | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| 14 | ne | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| 15 | 87.4 ± 3.6 | 52.9 ± 6.3 |

| 16 | 90.5 ± 2.8 | 60.6 ± 2.5 |

| 17 | 89.6 ± 0.4 | 84.0 ± 4.8 |

| 18 | 89.3 ± 0.8 | 71.4 ± 2.8 |

| 19 | 85.8 ± 0.9 | 46.0 ± 7.1 |

| 20 | 46.5 ± 9.7 | 10.6 ± 7.8 |

| 21 | 53.7 ± 5.5 | 7.6 ± 2.7 |

| 22 | 38.6 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 3.6 |

| 23 | 83.5 ± 0.03 | 46.9 ± 2.1 |

| Q | 95.8 ± 0.4 | 9.8 ± 4.7 |

| AZ | 95.9 ± 0.2 | 89.1 ± 1.5 |

| F267 | 56.8 ± 7.7 | 13.1 ± 5.3 |

| F2896 | 62.1 ± 5.6 | 17.8 ± 5.6 |

| Compd. | GI (%) | BFI (%) | Biofilm index | BE (%) | PI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ø | 60.25 | ||||

| 15 | 8.13 ± 2.76 | 48.6 ± 1.81 | 33.72 | 24.86± 1.13 | 42.34 ± 1.37 |

| 16 | 31.85 ± 1.64 | 53.72 ± 0.43 | 40.9 | 43.08 ± 2.15 | 20.45 ± 0.69 |

| 18 | 28.34 ± 2.57 | 45.26 ± 1.88 | 46.02 | 29.74 ± 1.47 | 16.02 ± 0.87 |

| 19 | 43.7 ± 2.24 | 61.57 ± 0.84 | 41.13 | 35.36 ± 1.62 | 38.87 ± 1.57 |

| 23 | 23.38 ± 3.03 | 29.08 ± 1.03 | 55.75 | 10.89 ± 1.29 | 72.02 ± 1.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).