Submitted:

10 July 2023

Posted:

11 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and subjects

2.2. Saliva sampling

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

2.3.2. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21)

2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study subjects

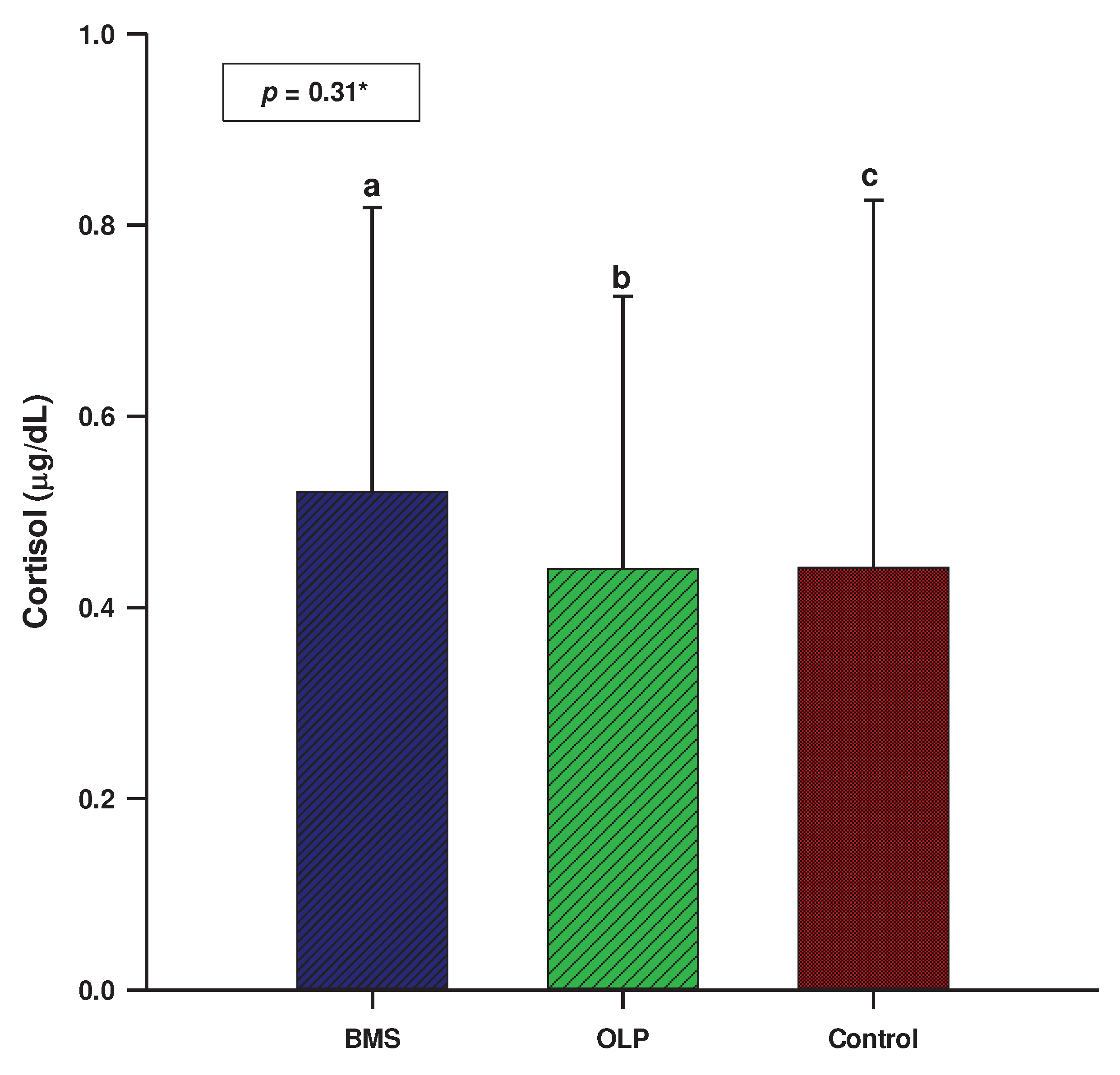

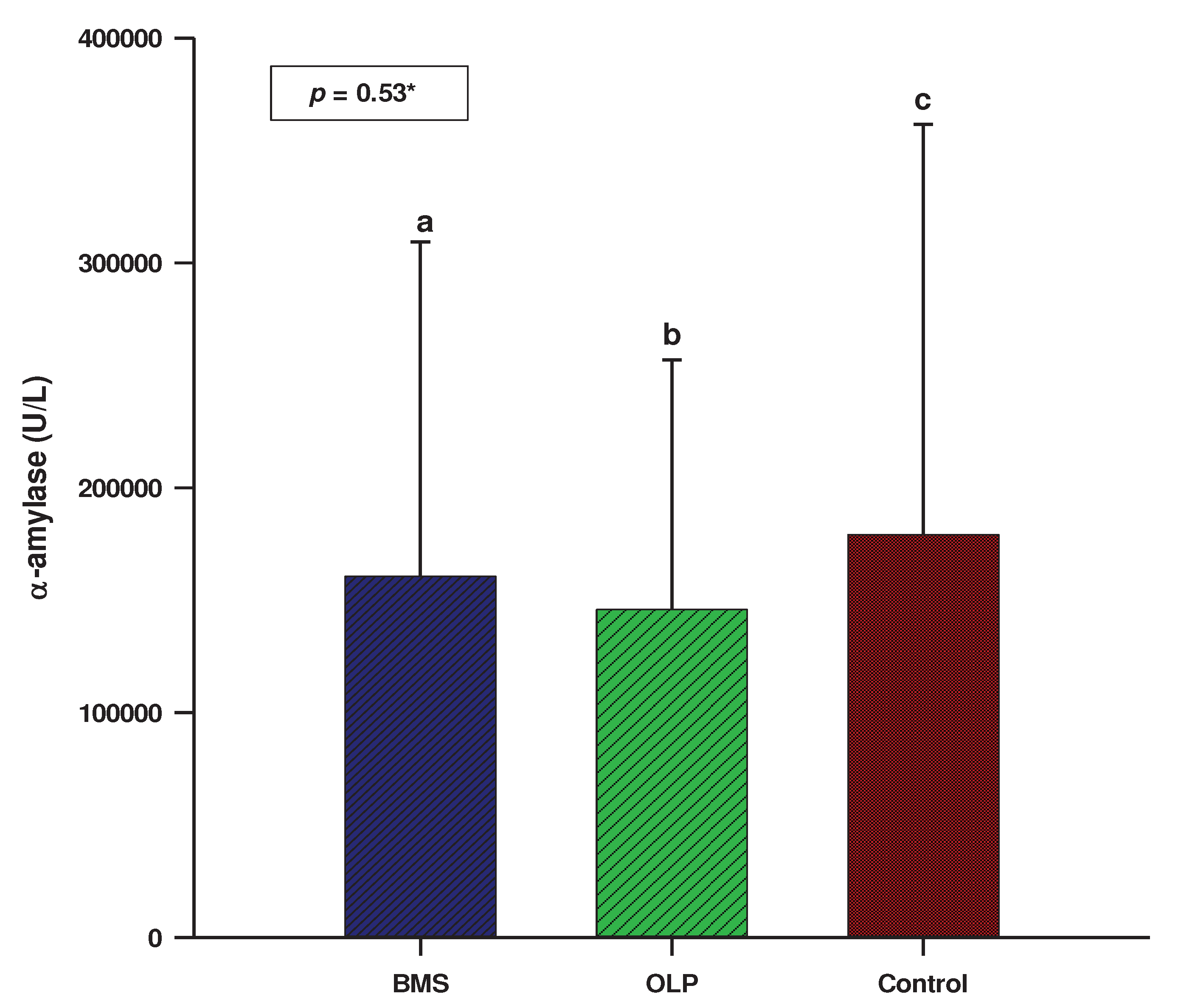

3.2. Salivary biomarkers

3.3. Psychological profile

3.4. Erosive and non-erosive form of OLP

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Lodi, G.; Scully, C.; Carrozzo, M.; Griffiths, M.; Sugerman, P.B.; Thongprasom, K. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: Report of an international consensus meeting. Part 2. Clinical management and malignant transformation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2005, 100, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo-Moreno, J.L.; Bagán, J.V.; Rojo-Moreno, J.; Donat, J.S.; Milián, M.A.; Jiménez, Y. Psychologic factors and oral lichen planus. A psychometric evaluation of 100 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1998, 86, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartan, B.E. Psychological factors associated with oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med 1995, 24, 273–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisen, D. The clinical features, malignant potential, and systemic associations of oral lichen planus: A study of 723 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002, 46, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grushka, M.; Epstein, J.B.; Gorsky, M. Burning mouth syndrome. Am Fam Physician 2002, 65, 615–620. [Google Scholar]

- Kamala, K.A.; Sankethguddad, S.; Sujith, S.G.; Tantradi, P. Burning Mouth Syndrome. Indian J Palliat Care 2016, 22, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogulj, A.A.; Richter, I.; Brailo, V.; Krstevski, I.; Boras, V.V. Catastrophizing in Patients with Burning Mouth Syndrome. Acta Stomatol Croat 2014, 48, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scala, A.; Checchi, L.; Montevecchi, M.; Marini, I.; Giamberardino, M.A. Update on burning mouth syndrome: overview nad patient management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2003, 14, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braud, A.; Boucher, Y. The relationship between the clinical features of idiopathic burning mouth syndrome and self-perceived quality of life. J Oral Sci 2016, 58, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.J.C.; Underhill, H.C.; Abdel-Karim, A.; Christmas, D.M.; Bolea-Alamanac, B.M.; Potokar, J.; Herrod, J.; Prime, S.S. Individual oral symptoms in burning mouth syndrome may be associated differentially with depression and anxiety. Acta Odontol Scand 2016, 74, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, P.; Clark, G.T. Burning mouth syndrome: an update on diagnosis and treatment methods. J Calif Dent Assoc 2006, 34, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, A.; Kumar, C.A.; Kumar, J.S.; Nair, G.K.R.; Agrawal, V.M. Estimation of Salivary Cortisol Level and Psychological Assessment in Patients with Oral Lichen Planus. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol 2018, 30, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Mood disorders and allostatic load. Biol Psychiatry 2003, 54, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratzehi, T.; Salimi, S.; Parvaee, A. Comparison of Salivary Cortisol and α-amylase Levels and Psychological Profiles in Patients with Burning Mouth Syndrome. Spec Care Dentist 2017, 37, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nater, U.M.; Rohleder, N. Salivary alpha-amylase as a non-invasive biomarker for the sympathetic nervous system: current state of research. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu-Wang, C.Y.; Patel, M.; Feng, J.; Milles, M.; Wang, S.L. Decreased levels of salivary prostaglandin E2 and epidermal growth factor in recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Arch Oral Biol 1995, 40, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Meij, E.H.; van der Waal, I. Lack of clinicopathologic correlation in the diagnosis of oral lichen planus based on the presently available diagnostic criteria and suggestions for modifications. J Oral Pathol Med 2003, 32, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, A.; Checchi, L.; Montevecchi, M.; Marini, I.; Giamberardino, M.A. Update on burning mouth syndrome: overview nad patient management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2003, 14, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Agra, M.; González-Serrano, J.; de Pedro, M.; Virto, L.; Caponio, V.C.A.; Ibáñez-Prieto, E.; Hernández, G.; López-Pintor, R.M. Salivary biomarkers in burning mouth syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis 2022. Oral Dis Online ahead of print]. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J-H. ; Kho, H-S. Blood contamination in salivary diagnostics: Current methods and their limitations. Clin Chem Lab Med 2019, 57, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamodyová, N.; Baňasová, L.; Janšáková, K.; Koborová, I.; Tóthová, Ľ.; Stanko, P.; Celec, P. Blood contamination in Saliva: Impact on the measurement of salivary oxidative stress markers. Dis Markers 2015, 2015, 479251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pačić-Turk, Lj.; Ćepulić, D-B.; Haramina, A.; Bošnjaković, J. The relationship of different psychological factors with the level of stress, anxiety and depression in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Republic of Croatia. Suvremena psihologija 2020, 23, 35–53. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Jornet, P.; Zavattaro, E.; Mozaffari, H.R.; Ramezani, M.; Sadeghi, M. Evaluation of the Salivary Level of Cortisol in Patients with Oral Lichen Planus: A Meta-Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019, 55, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humberto, J.S.M.; Pavanin, J.V.; da Rocha, M.J.A.; Motta, A.C.F. Cytokines, cortisol, and nitric oxide as salivary biomarkers in oral lichen planus: a systematic review. Braz Oral Res 2018, 32, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koray, M.; Dülger, O.; Ak, G.; Horasanli, S.; Uçok, A.; Tanyeri, H.; Badur, S. The evaluation of anxiety and salivary cortisol levels in patients with oral lichen planus. Oral Dis 2003, 9, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.; Ashok, L.; Sujatha, G.P. Evaluation of salivary cortisol and psychological factors in patients with oral lichen planus. Indian J Dent Res 2009, 20, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadendla, L.K.; Meduri, V.; Paramkusam, G.; Pachava, K.R. Association of salivary cortisol and anxiety levels in lichen planus patients. J Clin Diagn Res 2014, 8, ZC01–03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rödström, P.O.; Jontell, M.; Hakeberg, M.; Berggren, U.; Lindstedt, G. Erosive oral lichen planus and salivary cortisol. J Oral Pathol Med 2001, 30, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girardi, C.; Luz, C.; Cherubini, K.; de Figueiredo, M.A.Z.; Nunes, M.L.T.; Salum, F.G. Salivary cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels, psychological factors in patients with oral lichen planus. Arch Oral Biol 2011, 56, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratzehi, T.; Arbabi-Kalati, F.; Salimi, S.; Honarmand, E. The evaluation of psychological factor and salivary cortisol and IgA levels in patients with oral lichen planus. Zahedan J Res Med Sci 2014, 16, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pippi, R.; Romeo, U.; Santoro, M.; Del Vecchio, A.; Scully, C.; Petti, S. Psychological disorders and oral lichen planus: matched case-control study and literature review. J Oral Dis 2016, 22, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Jornet, P.; Cayuela, C.A.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Parra-Perez, F.; Escribano, D.; Ceron, J. Oral lichen planus: salival biomarkers cortisol, immunoglobulin A, adiponectin. J Oral Pathol Med 2016, 45, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansourian, A.; Najafi, S.; Nojoumi, N.; Parhami, P.; Moosavi, M-S. Salivary Cortisol and Salivary Flow Rate in Clinical Types of Oral Lichen Planus. Skinmed 2018, 16, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jääskeläinen, SK. Pathophysiology of primary burning mouth syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol 2012, 123, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken-Saavedra, J.; Tarquinio, S.B.; Kinalski, M.; Haubman, D.; Martins, M.W.; Vasconcelos, A.C. Salivary characteristics in burning mouth syndrome: a systematic review. Minerva Dent Oral Sci 2022, 71, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Jornet, P.; Camacho-Alonso, F.; Andujar-Mateos, M.P. Salivary cortisol, stress and quality of life in patients with burning mouth syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009, 23, 1212–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, A.; Yoshida, H.; Morita, S. Changes of salivary cortisol and chromogranin A levels in patients with burning mouth syndrome. J Osaka Dental Univ 2010, 44, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza, F.T.A.; Kummer, A.; Silva, M.L.V.; Amaral, T.M.P.; Abdo, E.N.; Abreu, M.H.N.G.; Silva, T.A.; Teixeira, A.L. The association of openness personality trait with stress-related salivary biomarkers in burning mouth syndrome. Neuroimmunomodulation 2015, 22, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyawardana, A.; Chmieliauskaite, M.; Farag, A.M.; Albuquerque, R.; Forssell, H.; Nasri-Heir, C.; Klasser, G.D.; Sardella, A.; Mignogna, M.D.; Ingram, M.; Carlson, C.R.; Miller, C.S. World Workshop on Oral Medicine VII: Burning mouth syndrome: A systematic review of disease definitions and diagnostic criteria utilized in randomized clinical trials. Oral Dis 2019, 25 Suppl 1, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoura, J.A.dS.; Pires, A.L.P.V.; Alves, L.D.B.; Arsati, F.; Lima-Arsati, Y.B.dO.; Dos Santos, J.N, Freitas, V.S. Psychological profile and α-amylase levels in oral lichen planus patients: A case-control preliminary study. Oral Dis 2023, 29, 1242–1249. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H-I.; Kim, Y-Y.; Chang, J-Y.; Ko, J-Y.; Kho, H-S. Salivary cortisol, 17β-estradiol, progesterone, dehydroepiandrosterone, and α-amylase in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Oral Dis 2012, 18, 613–620. [CrossRef]

- De Porras-Carrique, T.; González-Moles, M.A.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; Ramos-García, P. Depression, anxiety, and stress in oral lichen planus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig 2022, 26, 1391–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimi, H.; Pourshahidi, S.; Tadbir, A.A. Evaluation of the Relationship between Oral Lichen Planus and Stress. J Dent (Shiraz) 2011, 12, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Koike, K.; Shinozaki, T.; Hara, K.; Noma, N.; Okada-Ogawa, A.; Asano, M.; Shinoda, M.; Eliav, E.; Gracely, R.H.; Iwata, K.; Imamura, Y. Immune and endocrine function in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Clin J Pain 2014, 30, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Pedro, M.; López-Pintor, R.M.; Casañas, E.; Hernández, G. Effects of photobiomodulation with low-level laser therapy in burning mouth syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. Oral Dis 2020, 26, 1764–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample N=160 |

OLP group N=60 |

BMS group N=60 |

Control group N=40 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender (N, %) Men Women |

33 (20.6) 127 (79.4) |

15 (25.0) 45 (75.0) |

11 (18.3) 49 (81.7) |

7 (17.5) 33 (82.5) |

0.57* |

| Age (years) | 63.0 (52.0-70.0) |

63.0 (51.5-70.5) |

66.0 (57.0-72.0) |

61.0 (52.0-65.0) |

0.10# |

| OLP group N=60 |

BMS group N=60 |

Control group N=40 |

p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 1.0 (0.0-8.0) | 10.0 (4.0-18.0) | 2.0 (0.0-4.0) | <0.001ab |

| Anxiety | 4.0 (0.0-8.0) | 7.0 (4.0-16.0) | 2.0 (0.0-5.0) | <0.001ab |

| Stress | 8.0 (2.0-14.0) | 16.0 (8.0-28.0) | 4.0 (2.0-14.0) | <0.001ab |

| Depression | Anxiety | Stress | Cortisol | α-amylase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 1.0 | ||||

| Anxiety | 0.643* | 1.0 | |||

| Stress | 0.720* | 0.696* | 1.0 | ||

| Cortisol | -0.011 | -0.016 | -0.077 | 1.0 | |

| α-amylase | -0.037 | 0.050 | 0.053 | 0.039 | 1.0 |

| Depression | Anxiety | Stress | Cortisol | α-amylase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 1.0 | ||||

| Anxiety | 0.652* | 1.0 | |||

| Stress | 0.793* | 0.705* | 1.0 | ||

| Cortisol | 0.083 | 0.028 | 0.122 | 1.0 | |

| α-amylase | 0.048 | -0.218 | -0.024 | 0.008 | 1.0 |

| OLP | BMS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r* | p | r* | p | |

| Cortisol | 0.253 | 0.05 | -0.089 | 0.50 |

| α-amylase | 0.038 | 0.77 | 0.076 | 0.56 |

| Depression | -0.078 | 0.55 | -0.007 | 0.96 |

| Anxiety | -0.035 | 0.79 | -0.033 | 0.80 |

| Stress | -0.023 | 0.86 | -0.026 | 0.84 |

| OLP | BMS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r* | p | r* | p | |

| Cortisol | 0.006 | 0.96 | -0.230 | 0.08 |

| α-amylase | 0.079 | 0.55 | -0.004 | 1.10 |

| Depression | 0.109 | 0.41 | 0.373 | 0.003 |

| Anxiety | 0.081 | 0.54 | 0.515 | <0.001 |

| Stress | 0.089 | 0.50 | 0.365 | 0.004 |

| Erosive OLP | Non-erosive OLP | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N=40 | N=20 | p | |

| Cortisol | 0.45 ± 0.31 | 0.41 ± 0.23 | 0.69† |

| α-amylase | 100815 (67160-257030) | 101035 (74825-142870) | 0.55* |

| Depression | 1.0 (0.0-5.0) | 2.0 (0.0-10.0) | 0.51* |

| Anxiety | 3.0 (0.0-6.0) | 5.0 (0.0-13.0) | 0.54* |

| Stress | 8.0 (2.0-12.0) | 8.0 (1.0-16.0) | 0.76* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).