Submitted:

10 July 2023

Posted:

11 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Wastewater Management

2.2. Matrix of Alliance, Conflicts, Tactics, Objective and Recomenndations (MACTOR) analysis

3. Materials and Methods

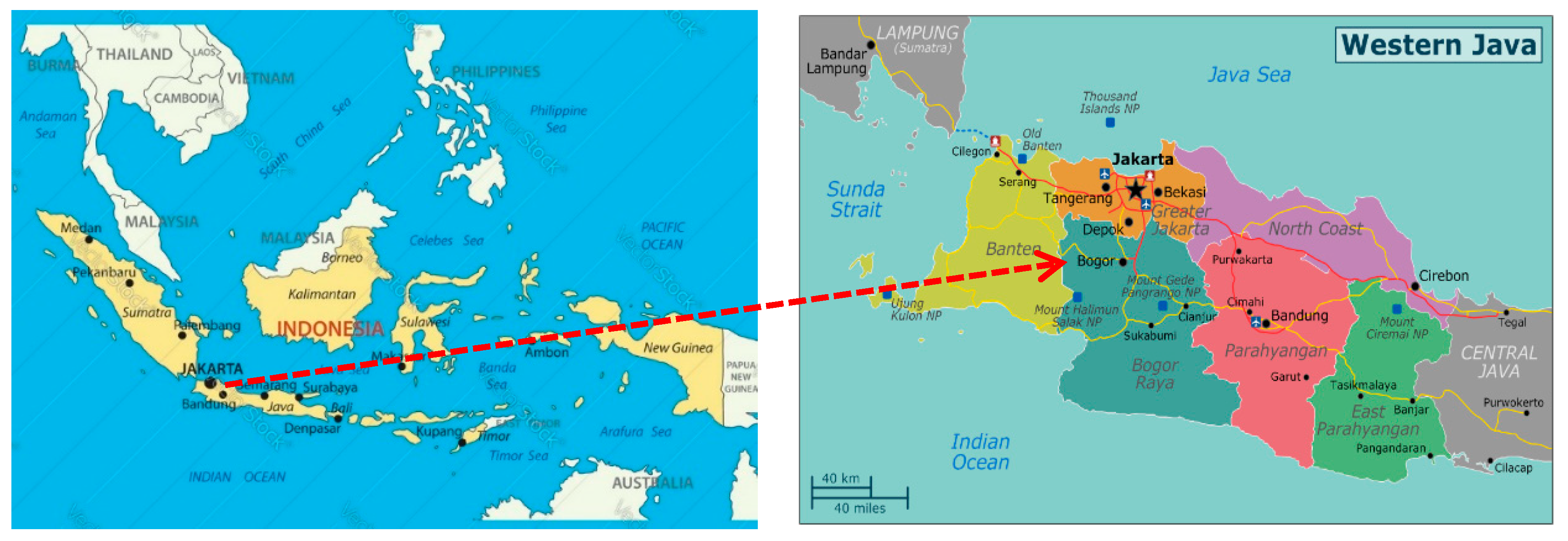

3.1. Study site

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

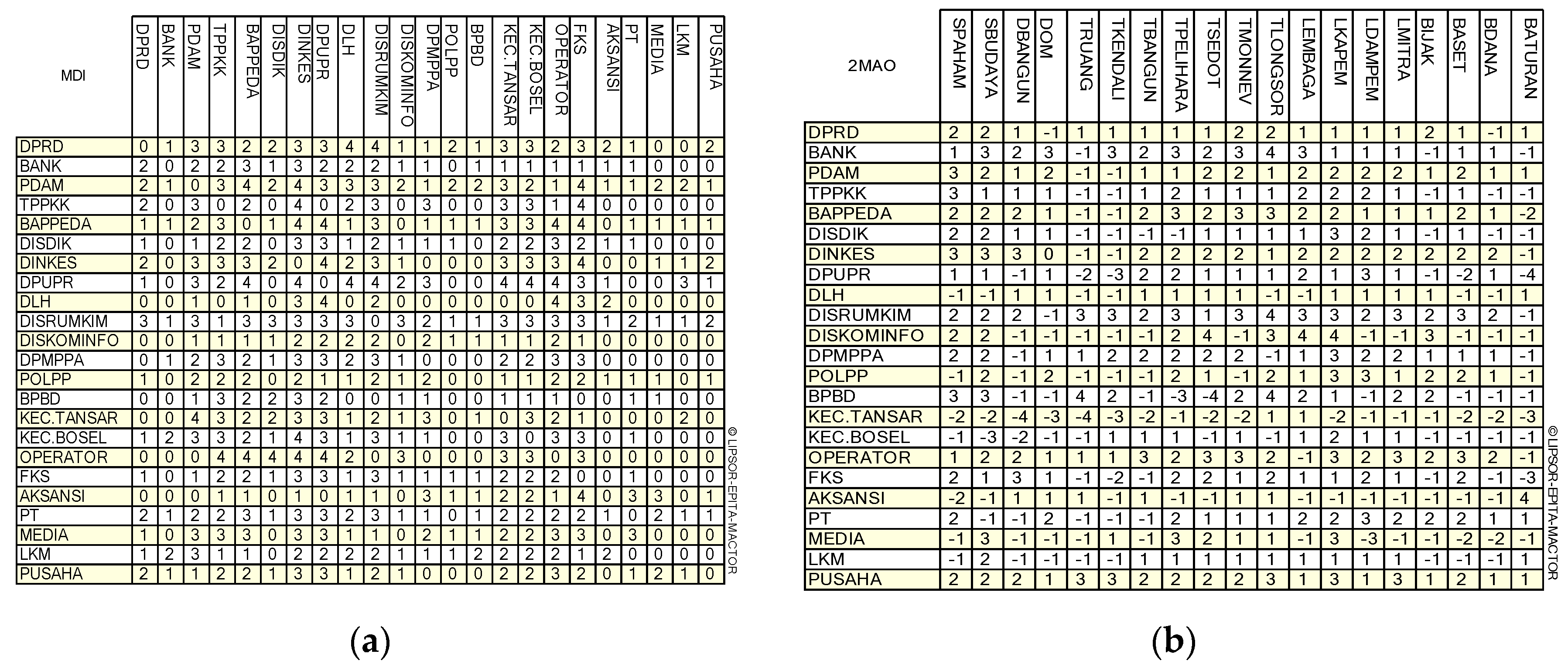

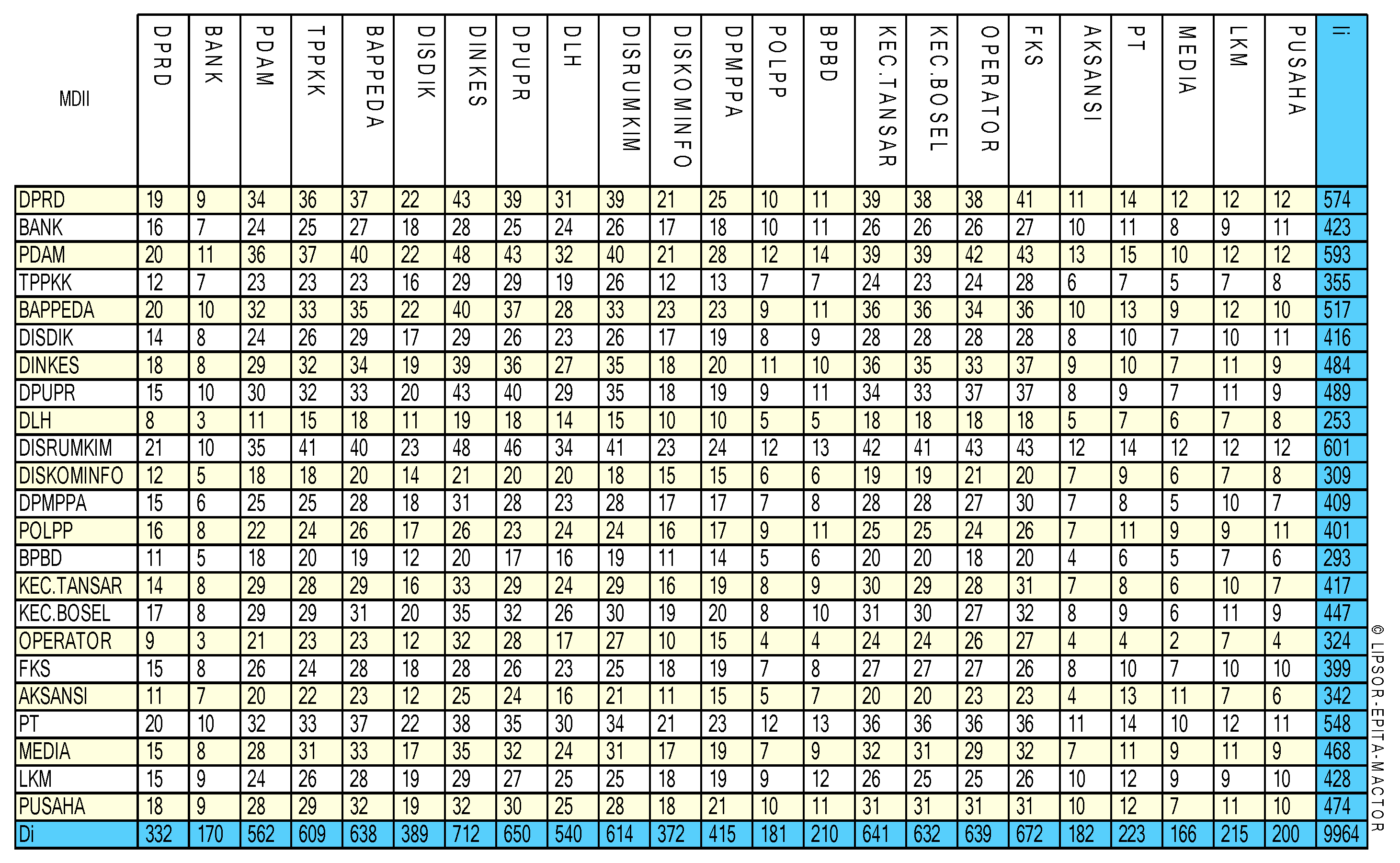

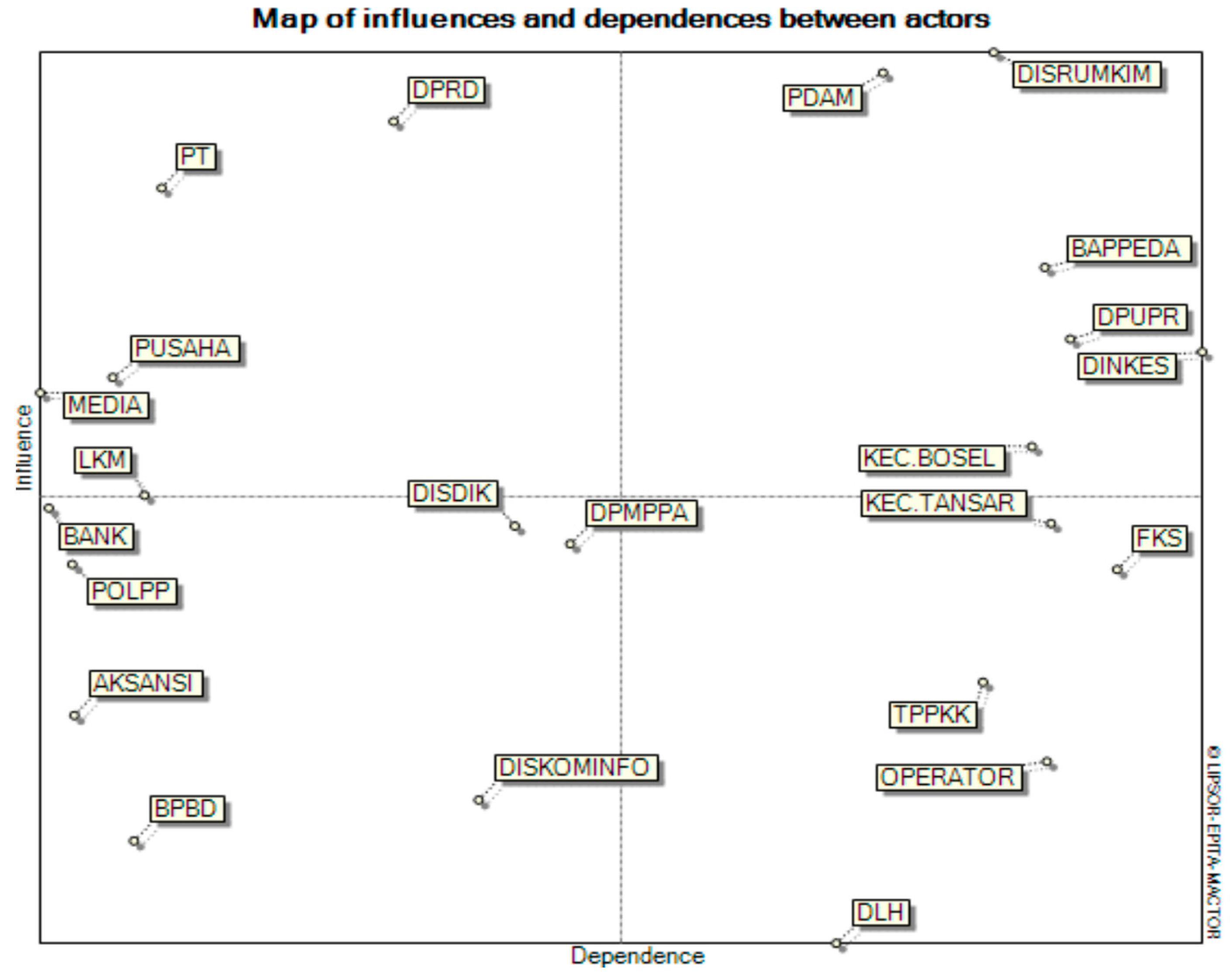

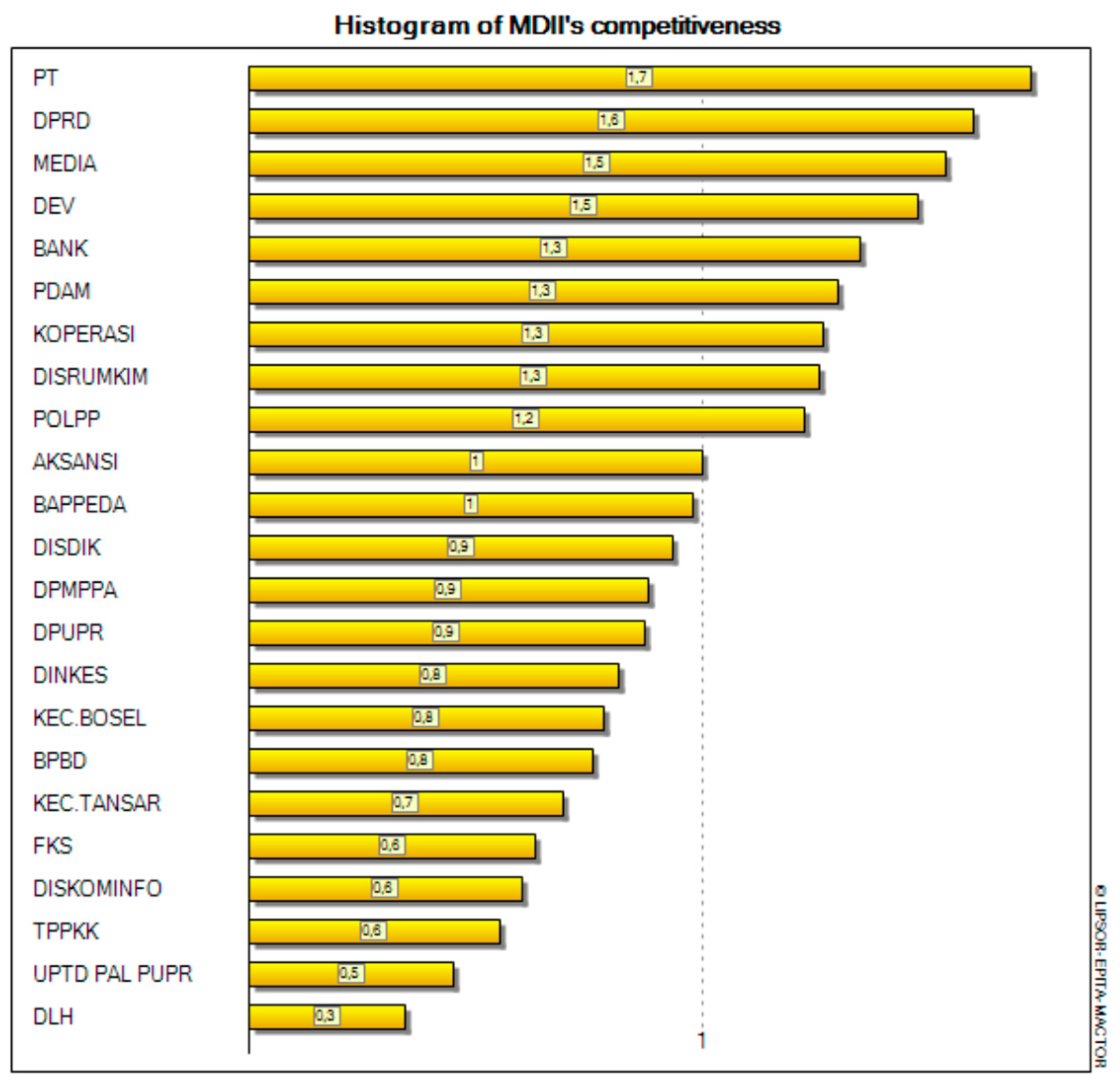

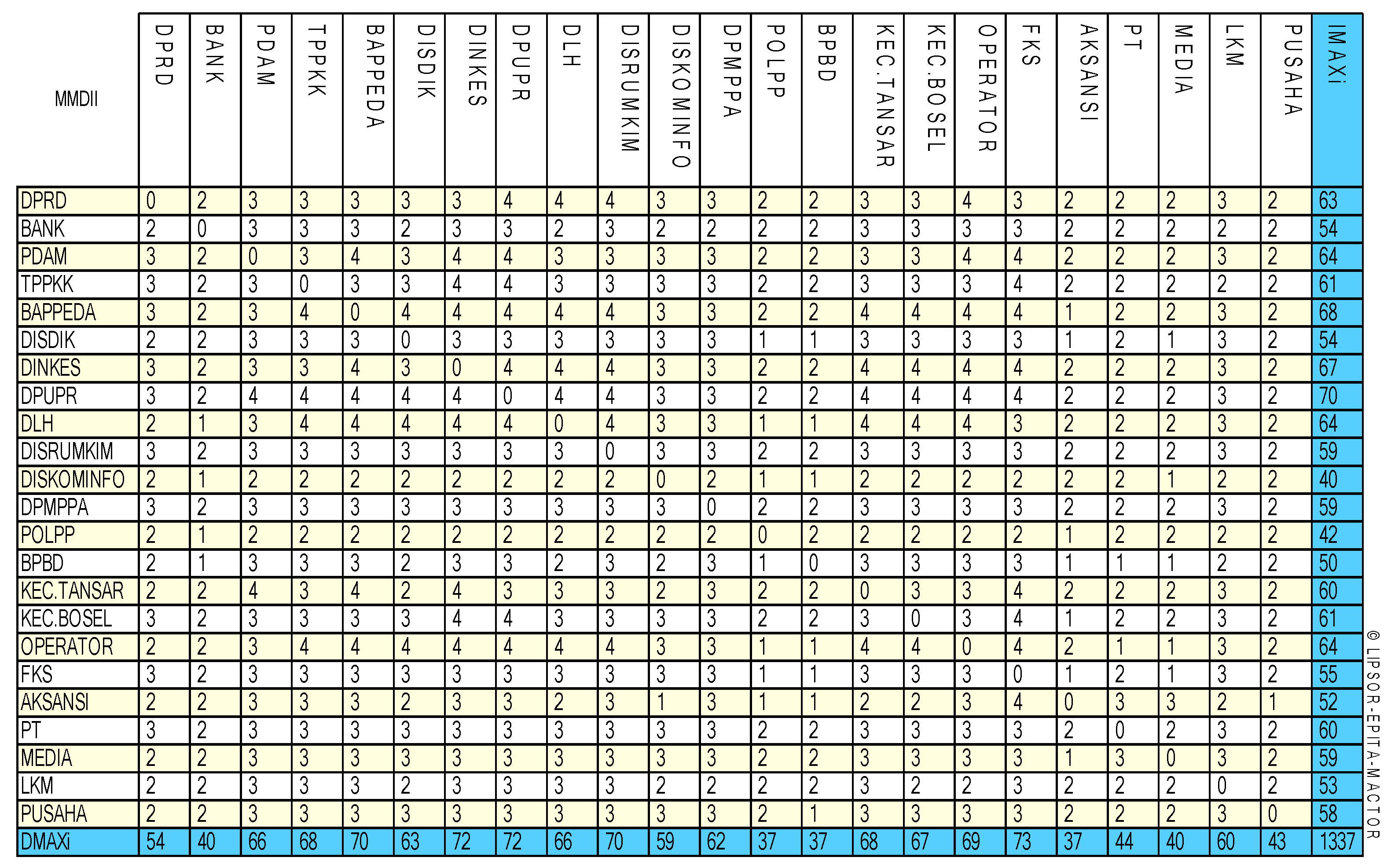

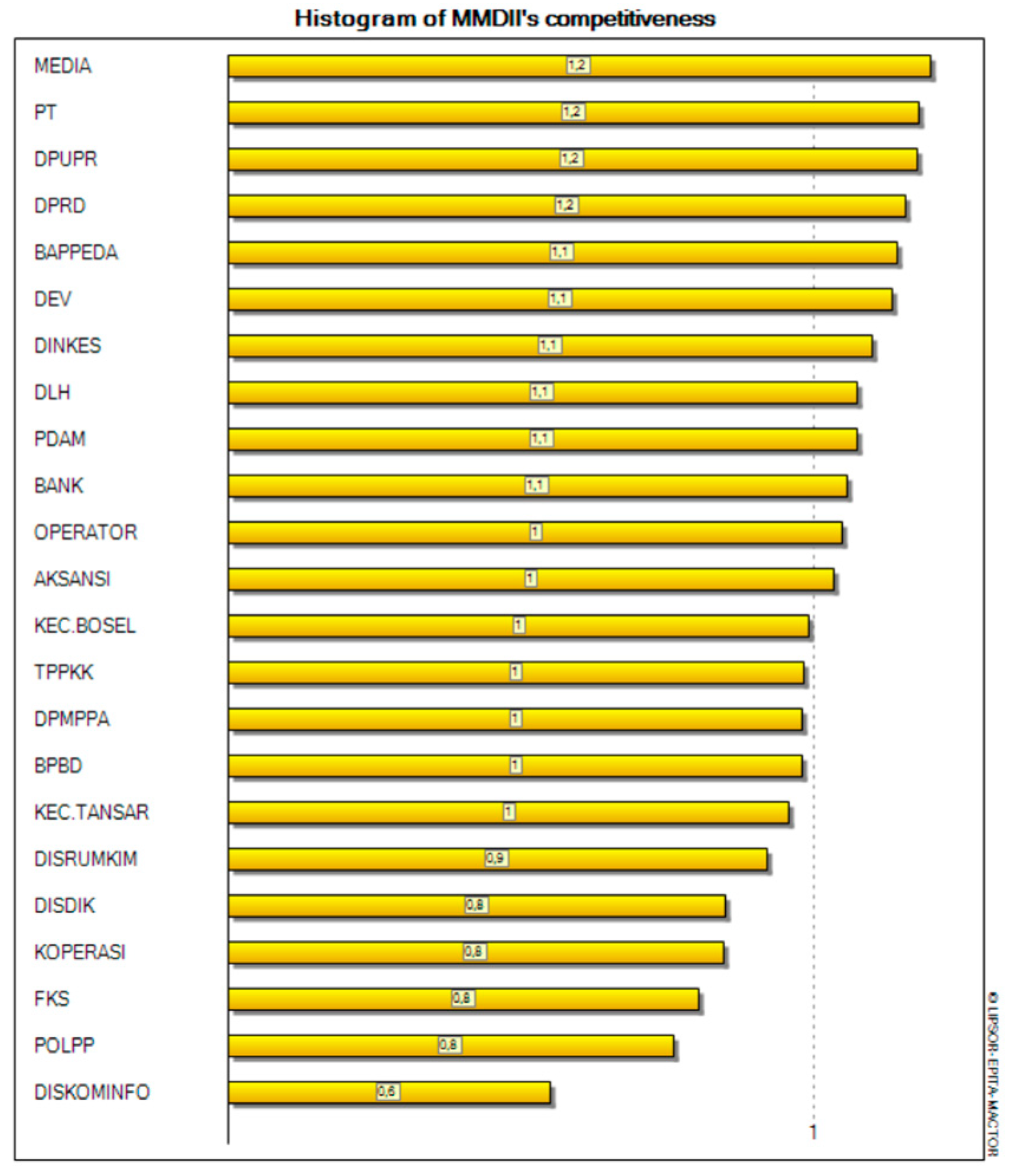

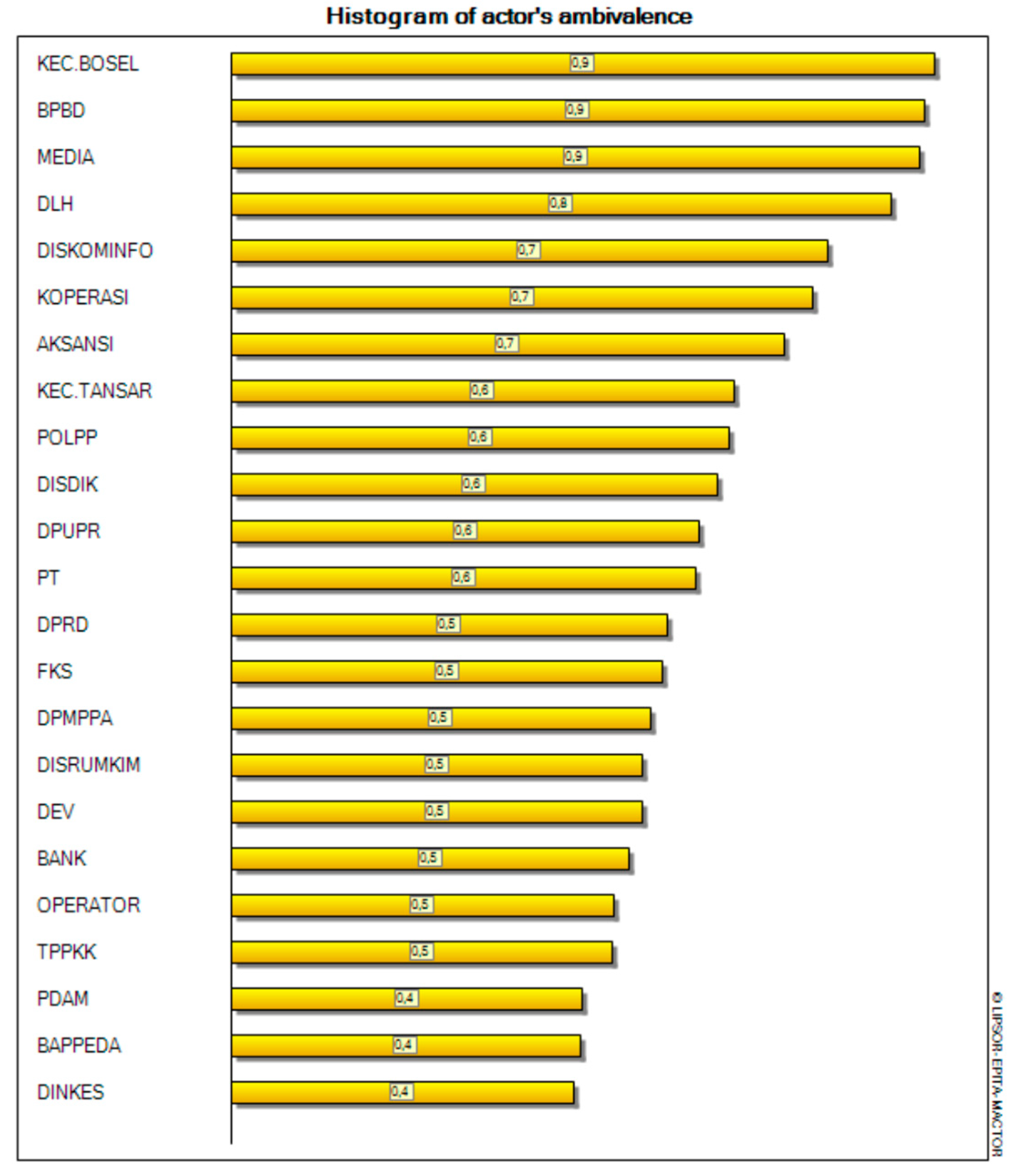

Direct and indirect influence between actors

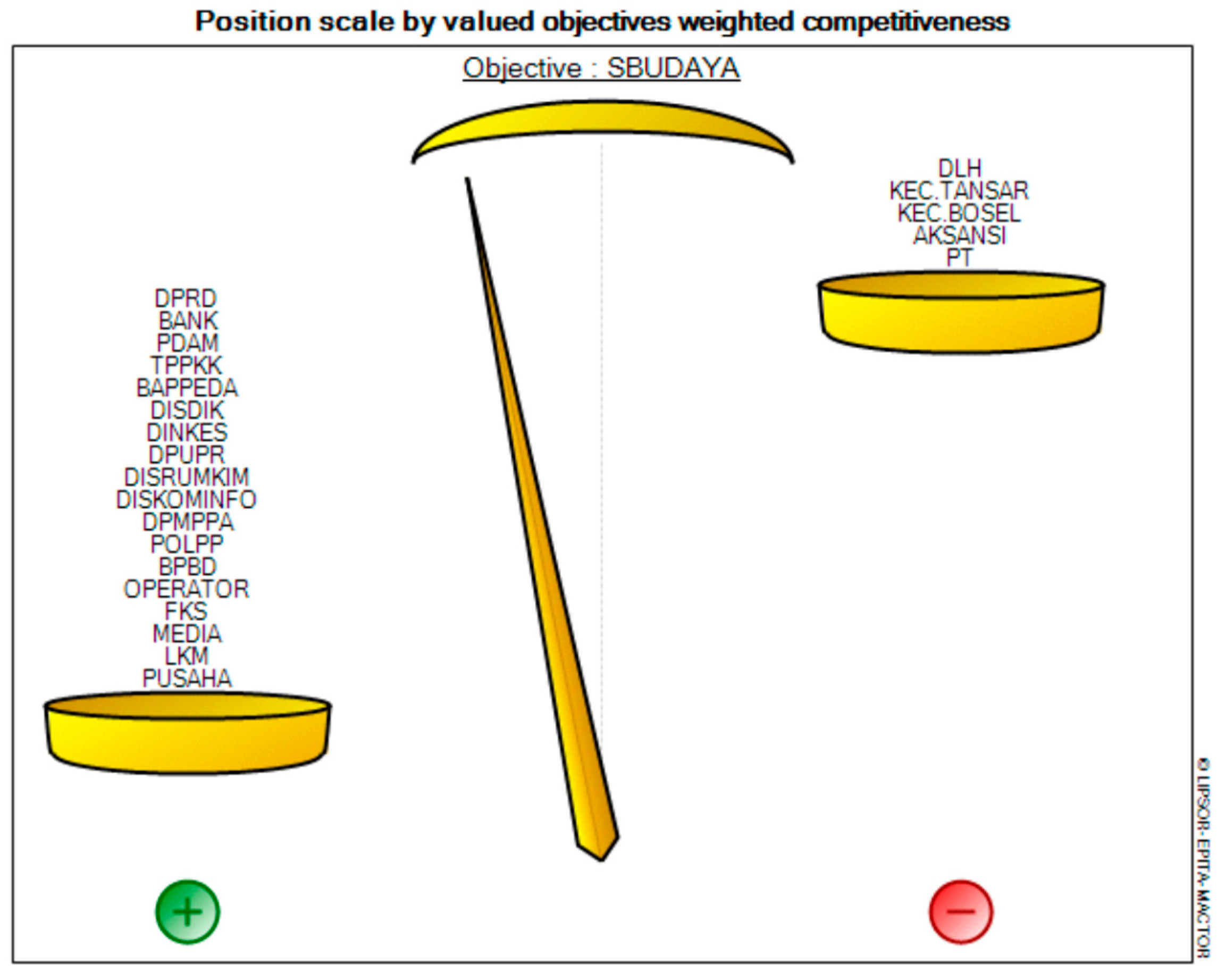

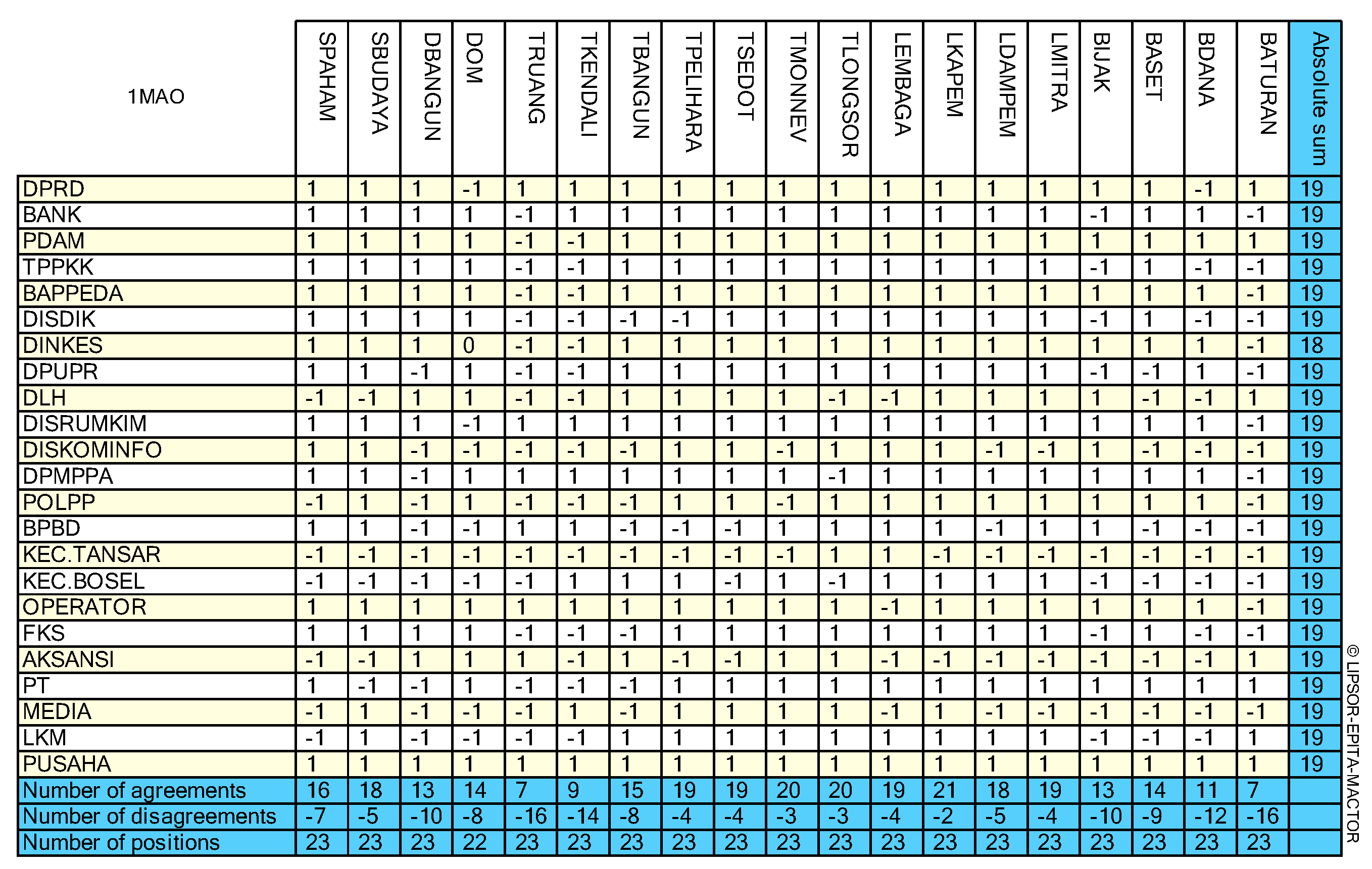

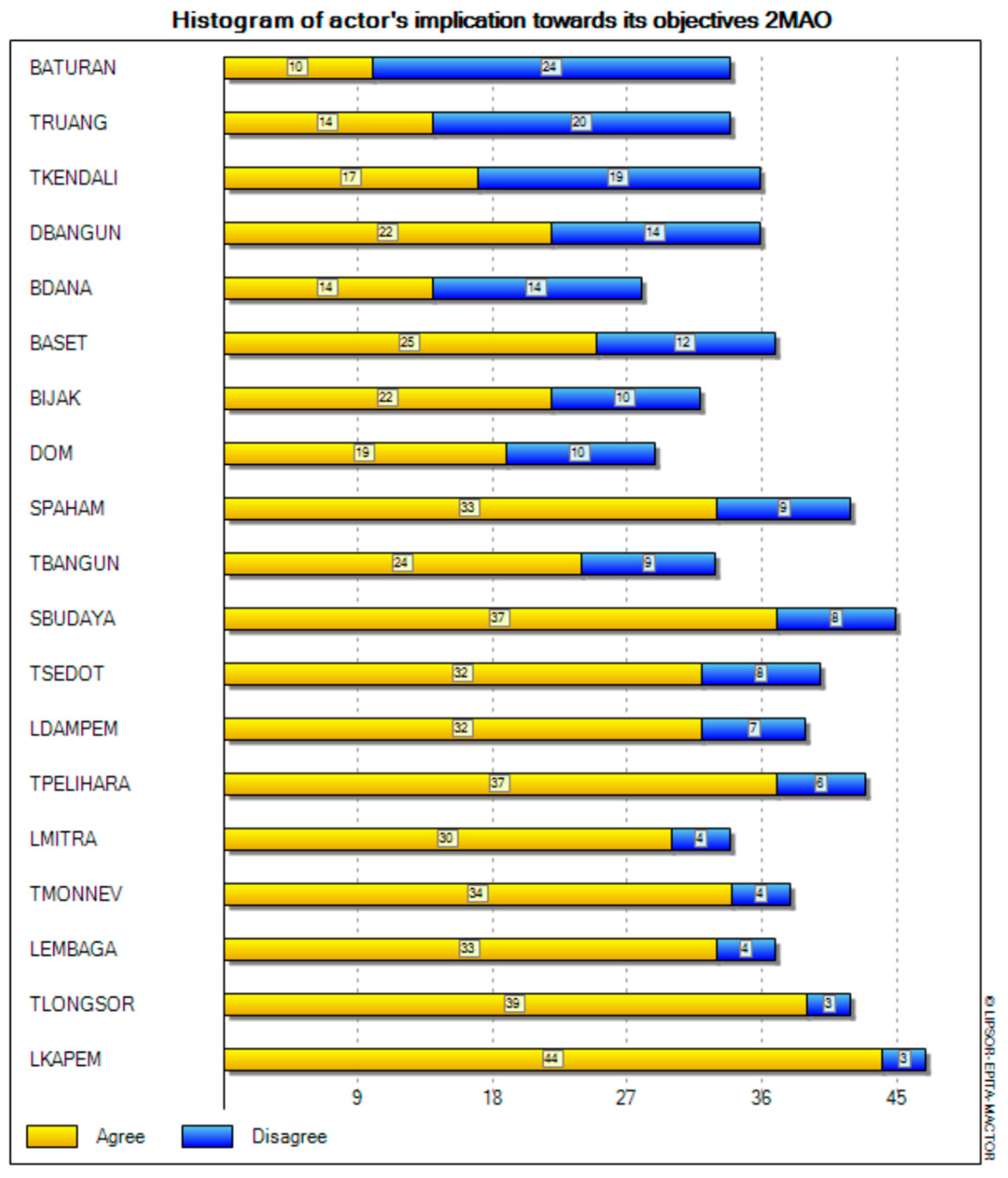

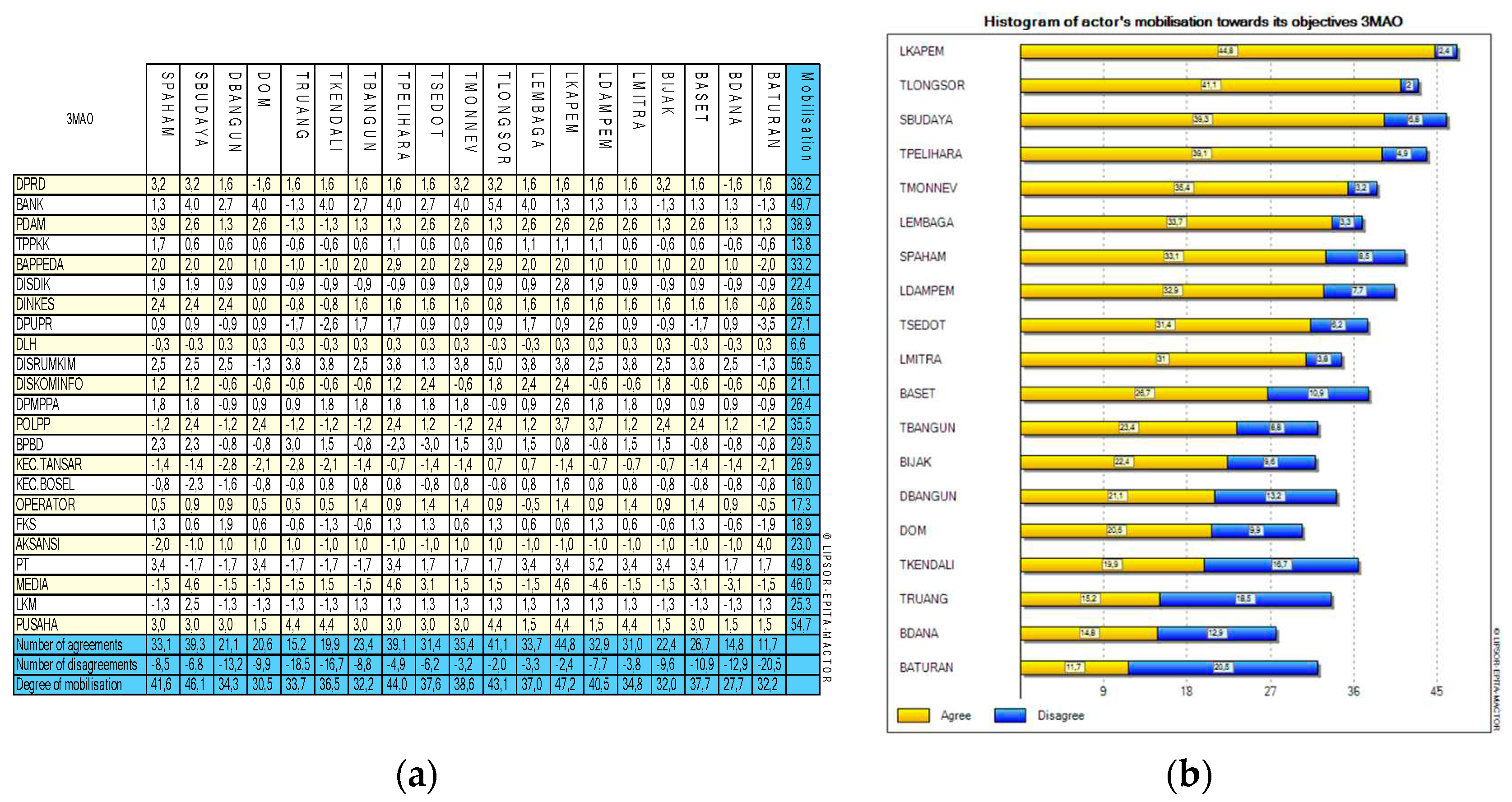

Actor relations and goals

- South Bogor Sub-District (KEC BOSEL): Increase the capacity of officials at the sub-district office both in theory and in practice to properly manage community-based domestic wastewater and provide a sufficient budget to carry out activities according to the scope of their duties and functions.

- Regional Disaster Management Agency (BPBD): Improving disaster studies caused by unmanaged domestic wastewater, especially ways to mitigate it.

- Media: Improving cooperation, campaigning, and massively disseminating the proper ways of managing domestic wastewater.

- Department of the Environment (DLH): Increasing the budget for inspection of water quality standards originating from domestic waste and increasing the budget for campaigns for proper domestic wastewater management and environmental law enforcement.

-

Social aspects

- o

- Intensive triggering, with improved triggering materials, expanded triggering targets, expanded triggering media,

- o

- Conduct awareness campaigns for the environment,

- o

- Using existing educational institutions (formal or informal) to promote proper management of domestic wastewater,

- o

- Dissemination of Regional Regulation No. 4 of 2018 Concerning Domestic Wastewater Management, in which the regional regulation contains sanctions for people who do not treat domestic wastewater,

- o

- Disseminate Law No. 32 of 2009 concerning Environmental Protection and Management, wherein the law requires everyone who generates waste to process it,

- o

- Increasing community participation in domestic wastewater management.

- b.

-

Financial aspects

- o

- Making a community-based domestic wastewater management plan in each kelurahan with government assistance, including planning sources of financing (from the community itself, CSR, government, loans, etc.) so that the community knows/understands the importance of financing, providing input on ways obtaining financing, facilitating the public to gain access to financing,

- o

- Bringing microfinance institutions closer to communities that need loans for the procurement of domestic wastewater infrastructure,

- o

- Dissemination of ways to get the Company's CSR.

- c.

-

Technical aspects

- o

- Dissemination of methods for treating fecal sludge properly, especially how to operate and maintain domestic wastewater infrastructure, including the disposal/absorption of fecal sludge

- o

- Making plans for the management of domestic wastewater in each sub-district based on the community with assistance from the government, so that the decision on the type of domestic wastewater treatment is carried out by the community itself by considering the advantages and disadvantages of each wastewater treatment system (looking for forms / ways of building that are agreed upon by the community), agreement on ways to mobilize materials, tools and labor,

- o

- Government assistance in construction, operation and maintenance

- o

- Dissemination of the need for building and environmental management in support of sustainable domestic wastewater management,

- o

- Socialization of the need for supervision of buildings that will be and are being built to support the arrangement of buildings and the environment based on domestic wastewater management,

- o

- Conducting training on the construction of proper pre-sanitation facilities for local residents,

- o

- Adding BPBD tasks and functions to create mitigation strategies for domestic wastewater infrastructure facilities that have the potential to cause landslides

- o

- Creating appropriate technology in locations with limited land

- d.

-

Institutional aspects

- o

- Disseminating/explaining to the public that managing domestic wastewater involves various aspects (social, technical, financial, institutional, policy) and various activities ((socialization, triggering, planning, development, operation, and maintenance), thus a combination of existing institutions is needed, and therefore the need to increase the role of existing institutions in the community to be able to manage domestic wastewater, strengthen the institutional capacity of managers and users,

- o

- Strengthening community institutional cooperation internally in the sub-district with government facilitation as a basis for cooperation with other institutions,

- o

- Increase the capacity of government officials both in the region, as well as in other Regional Apparatus Organizations regarding the management of domestic wastewater, and as parties who assist the community,

- o

- The recommendation to overcome this difficulty is to provide an understanding that domestic wastewater management includes various aspects.

- e.

-

Policy aspects

- o

- Provide sufficient funding for the Kelurahan

- o

- Positioning sanitation management as a development priority

- o

- Increase the portion of the government's budget for domestic wastewater management

- o

- Made clear rules on how sanctions can be implemented through a Mayor's Regulation as a derivative of No. 4 of 2018 concerning Domestic Wastewater Management

- o

- Planning for the construction of domestic wastewater infrastructure (especially communal WWTP) must include proper land administration planning and an explanation of the consequences of the function of the land used by the communal WWTP

- o

- Give awards to people who have managed domestic wastewater properly, for example, holding a competition for managing communal WWTPs, etc

- o

- Making rules in the form of guardianship and instructions for implementing control/supervision of buildings and the environment based on domestic wastewater management in community-based informal self-help housing.

- o

- Providing incentives to communal WWTP land owners, Making clear rules on communal WWTP land ownership.

- o

- Recommendations for overcoming this difficulty are establishing guardianships with an explanation of the conditions under which sanctions can be applied and creating implementing regulations as derivatives of regional regulations regarding granting incentives, disincentives, awards, and sanctions.

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sclar, G.D.; Garn, J.V.; Penakalapati, G.; Alexander, K.T.; Krauss, J.; Freeman, M.C.; Boisson, S.; Medlicott, K.O.; Clasen, T. Effects of sanitation on cognitive development and school absence: a systematic review. Intern. J. Hygiene Environ. Health 2017, 220(6), 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strunz, E.C.; Addiss, D.G.; Stocks, M.E.; Ogden, S.; Utzinger, J.; Freeman, M.C. Water, sanitation, hygiene, and soil-transmitted helminth infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014, 11(3), e1001620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO and UNICEF. Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines. Geneva (Switzerland). 2017, WHO and UNICEF.

- [UN] United Nations-Habitat. Issue Paper on Informal Settlements. Habitat III Issue Papers 22 – Informal Settlements. New York (USA): UNHabitat.

- Weber, B. Addressing informal settlement growth in Namibia. Namibian J. Environment, 2017, 1, 16-26.

- Arimurthy, A.; Manaf, A. Lembaga Lokal dan Masyarakat dalam Pemenuhan Kebutuhan Rumah bagi Masyarakat Berpenghasilan Rendah. J Pembangunan Wilayah & Kota, 2013, 9(3), 307-316. (abstract in English). [CrossRef]

- Dovey, K. Sustainable informal settlements. J Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2015, 179, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [Bappeda] Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Kota Bogor. Rencana Pembangunan Pengembangan Perumahan dan Kawasan Permukiman. 2015, Bogor (ID): Pemerintah Kota Bogor.

- Khomarudin. Menelusuri Pembangunan Perumahan dan Permukiman. 1997, Jakarta (ID): PT. Rakasindo.

- Annasa, A.; Aryani, R.A.; Santoso, E.B. Analisis penentuan infrastruktur prioritas pada kawasan kumuh lingkungan kerantil Kota Blitar. ITS J of Civil Engineering, 2018, 33(2), 56-67. (abstract in English). [CrossRef]

- Chipungu, J.; Tidwell, J.B.; Chilengi, R.; Curtis, V.; Aunger, R. The social dynamics around shared sanitation in an informal settlement of Lusaka, Zambia. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 2018, 9(4), 102-110. [CrossRef]

- Badriyah, L.; Syafiq, A. The association between sanitation, hygiene, and stunting in children under two-years (An analysis of Indonesia’s basic health research, 2013). Makara J. Health Res. 2017, 21(2), 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanthi, D.; Yanuar, M.; Suprihatin. Kinerja instalasi pengolahan air limbah (ipal) komunal di Kota Bogor. J Permukiman, 2018, 13(1), 21-30. (abstract in English). [CrossRef]

- Solo, T.M.; Perez, E.; Joyce, S. Wash Technical Report no 85: Constraints In Providing Water And Sanitation Services To The Urban Poor.1993. Washington DC : the Office of Health, Bureau for Research and Development U.S. Agency for International Development.

- Nilsson, M.; Olsson, L. Sanitation in an Informal Settlement [Tesis]. 2013. Goteborg (SE ): Clamer University of technology.

- Mukonoweshuro, T.F. Barriers to The Provision of Basic Sanitation in Two Selected Informal Settlements in Harare, Zimbabwe [Tesis]. 2014, Johanesburg (ZA): The Wits University School of Governance.

- [WB] The World Bank. Urban sanitation review: Indonesia Country Study. 2013, documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/764171468023379490/pdf/838770FA0WP0P10Box0382116B00PUBLIC0.pdf.

- Hafidh, R.; Kartika, F.; Farahdiba, U. 2016. Keberlanjutan instalasi pengolahan air limbah domestik (Ipal) berbasis masyarakat, Gunung Kidul, Yogyakarta. J Sains dan Teknologi Lingkungan, 2016, 8(1), 46-55. (abstract in English). [CrossRef]

- Afandi, Y.V.; Sunoko, H.R.; Kismartini. Status keberlanjutan sistem pengelolaan air limbah domestik komunal berbasis masyarakat di Kota Probolinggo. J Ilmu Lingkungan, 2013, 11(2), 100-109. (abstract in English). [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, B.; Setiawan, B.; Rahmi, D.H. Pengelolaan Sumberdaya dan Lingkungan. 2016, Yogyakarta(ID): UGM Pr.

- Mitchell, C.; Ross, K.; Puspowardoyo, P.; Rosenqvist, T.; Wedahuditama, F. Effective governance for the successful long-term operation of local scale wastewater systems. the Institute for Sustainable Futures. 2016, Australia (AU): University of Technology Sydney.

- Prihandrijanti, M.; Firdayati, M. Current situation and considerations of domestic wastewater treatment systems for big cities in Indonesia (case study: Surabaya and Bandung). J. Water Sustainability, 2011, 1(2), 97–104.

- [Bappeda] Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Kota Bogor. Masterplan Air Limbah Kota Bogor. 2011, Bogor (ID): Pemerintah Kota Bogor.

- Bendahan S, Camponovo G, Pigneur Y. Multi-issue actor analysis: tools and models for assessing technology environments. J. Decision systems, 2003, 12(4), 1-31. [CrossRef]

- Fetoui, M.; Frija, A.; Dhehibi, B.; Sghaier, M.; Sghaier, M. Prospects for stakeholder cooperation in effective implementation of enhanced rangeland restoration techniques in southern Tunisia. Rangeland Ecol. Manag. 2021, 74, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, G.H.; MacDonell, S. Data gathering for actor analyses: A research note on the collection and aggregation of individual respondent data for MACTOR. Future Studies Res. J. Trends Strategies, 2017, 9(1), 115–137.

- Fauzi, A. Teknik analisis kebijakan. 2019, Indonesia (ID): Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.M. Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: A multi-actor perspective. J. Environmental Policy Planning, 2016, 18(5), 628–649. [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.; Sancino, A.; Benington, J.; Sørensen, E. Towards a multi-actor theory of public value co-creation. Public Management Review, 2017, 19(5), 640–654. [CrossRef]

- Beyers, J.; Dür, A.; Marshall, D.; Wonka, A. Policy-centred sampling in interest group research: Lessons from the INTEREURO project. Interest Groups and Advocacy, 2014, 3(2), 160–173. [CrossRef]

- Elmsalmi, M.; Hachicha, W. Risk mitigation strategies according to the supply actors’ objectives through MACTOR method. 2014 International Conference on Advanced Logistics and Transport (ICALT), 2014, May, 362–367. [CrossRef]

- Benavides, L.; Avellán, T.; Caucci, S.; Hahn, A.; Kirschke, S.; Müller, A. Assessing sustainability ofwastewater anagement systems in a multi-scalar, transdisciplinary manner in Latin America. Water, 2019, 11, 249. [CrossRef]

- Gravitiani, E.,; Sasanti, I.A.; Sartika, R.C.; Cahyadin, M. The role of stakeholders in sustainable tourism using mactor analysis: evidence from kragilan's top selfie, Magelang, Indonesia. Ekuilibrium: Jurnal Ilmiah Bidang Ilmu Ekonomi. 2022, 17(2), 102-109. [CrossRef]

- Venegas, C.; Sánchez-Alfonso, A.C.; Vesga, F.J.; Martín, A.; Celis-Zambrano, C.; Mendez, M.G. Identification and evaluation of determining factors and actors in the management and use of biosolids through prospective analysis (MicMac and Mactor) and social networks. Sustainability, 2022, 14, 6840. 6840. [CrossRef]

- Lakner, Z.; Kiss, A.; Merlet, I.; Oláh, J.; Máté, D.; Grabara, J.; Popp, J. Building coalitions for a diversified and sustainable tourism: two case studies from Hungary. Sustainability. 2018, 10, 1090. [CrossRef]

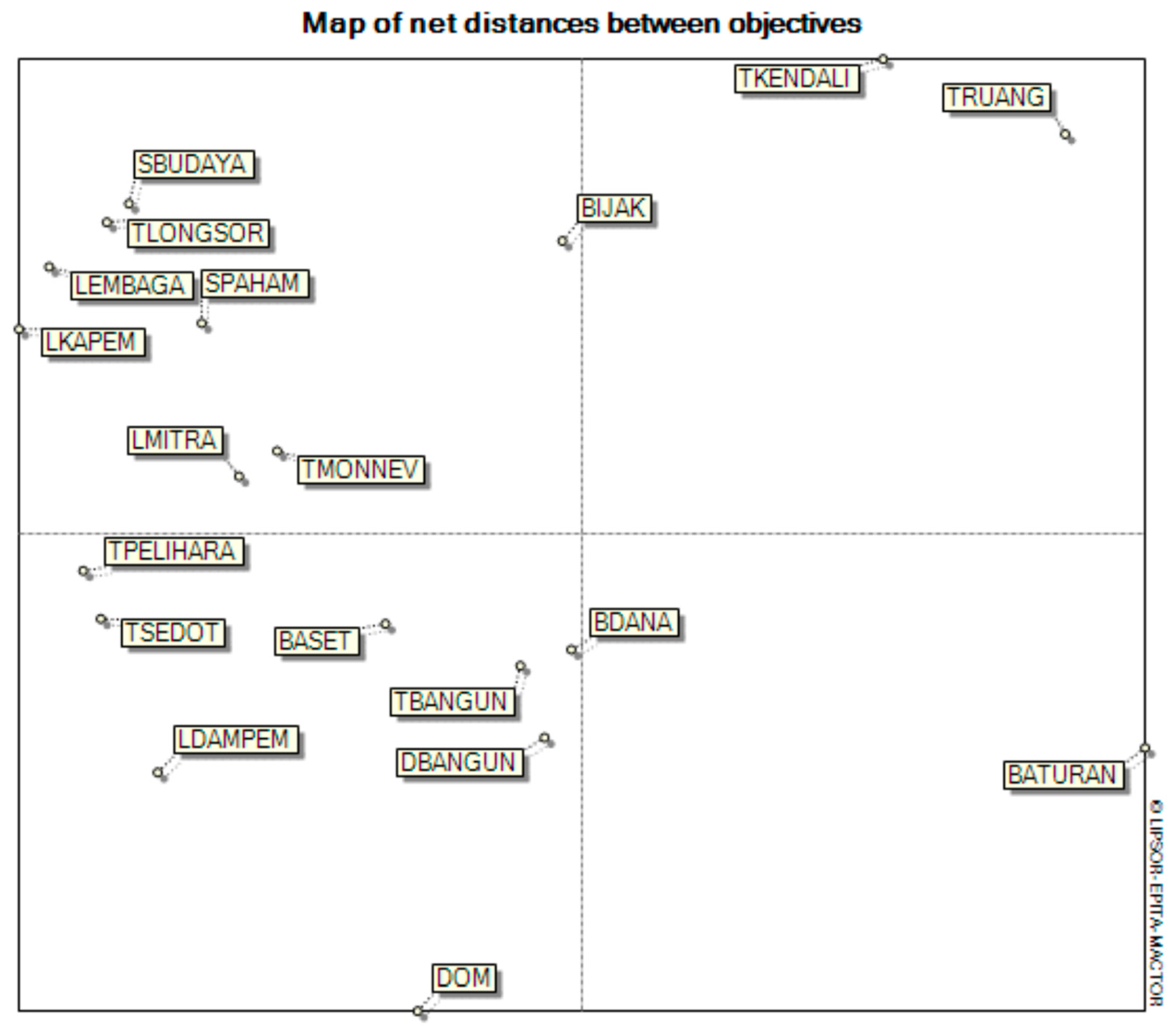

| Goals | Problems, obstacles, difficulties, and lack of activity towards achieving goals according to actors |

| Social aspects | |

| SPAHAM | Minimum information/don't understand about domestic wastewater management, one of the reasons is the absence of concrete examples of correct ways to manage domestic wastewater, whereas until now, many people still practice open defecation. |

| SBUDAYA | Open defecation has become a habit for several reasons, including no sanctions for the community and no land for laying septic tanks; the government's budget is limited and not yet a priority. |

| Financial aspects | |

| DBANGUN | There are still limited funding institutions that can serve the construction of domestic wastewater infrastructure facilities; the construction of domestic wastewater infrastructure facilities has not yet become a development priority/lack of funding from the government; the community has also not prioritized its development, limited CSR from private companies. |

| DOM | There are no incentives/rewards, and no assistance with tools for the operation and maintenance of domestic wastewater infrastructure facilities. |

| Technical aspects | |

| TRUANG | There are no specific rules for organizing informal self-help housing, and it is impossible to plan for informal self-help housing. |

| TKENDALI | There is no supervision and control of space in informal self-supporting housing, it is impossible to control the construction of informal self-help housing, and there are no planning documents as a guide in controlling. |

| TBANGUN | The cost of constructing domestic wastewater infrastructure is not affordable by the community, and due to limited land. |

| TPELIHARA | Topographical obstacles for draining fecal sludge (sharp slope, very narrow access), lots of community sanitation that is not maintained, because KSM/KPP is inactive/non-existent. |

| TSEDOT | KSM/KPP has never/rarely desorbed desludging, KSM/KPP is not active, there are several locations where desludging cannot/is very difficult, and the cost is expensive. |

| TMONEV | There has never been/rarely been monitoring of the performance of domestic wastewater management by the government. |

| TLONGSOR | There are no mitigation activities for locations that have the potential for landslides due to the flow of domestic wastewater into the ground, as a result of managed domestic wastewater, there is no construction control (domestic wastewater infrastructure) in landslide-prone locations. |

| Institutional aspects | |

| LEMBAGA | Social capital is lacking in several informal self-help housing locations, existing institutions still lack knowledge about proper domestic wastewater management. |

| LKAPEM | The government budget is limited and not a priority and the existing government capacity is still lacking in knowledge about domestic wastewater management, not the duties and functions of the OPD (because it is not written in the Mayor's of Bogor Regulation regarding the main tasks and functions), there are still many government officials who do not understand management methods domestic wastewater. |

| LDAMPEM | There is no/rarely any assistance from the government, many government officials themselves do not understand aspects of domestic wastewater management, not in the main duties and functions of OPD. |

| LMITRA | The existing partnerships are not continuous, there is a lack of determination from fellow partners to manage domestic wastewater better. |

| Policy aspects | |

| BIJAK | There are still policies that impede (indirectly) the management of domestic wastewater in informal self-help housing, and there is no planning for domestic wastewater management that is integrated between sectors. |

| BASET | The community is still not willing to relinquish their land even though a communal WWTP has been built. The ownership of land that has been built by an WWTP is unclear because it is handed over to KSM/KPP where KSM/KPP is not yet a legal entity, while Regional Government only has its assets listed, but not owned. |

| BDANA | The government's budget is very lacking, community suggestions are very lacking, and are not a priority (budget policies have not prioritized domestic wastewater management). |

| BATURAN | There are no implementing regulations, so it cannot be implemented regarding the provision of incentives, disincentives, sanctions and rewards. There is fear of social unrest because there are still many who practice open defecation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).