Submitted:

10 July 2023

Posted:

10 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

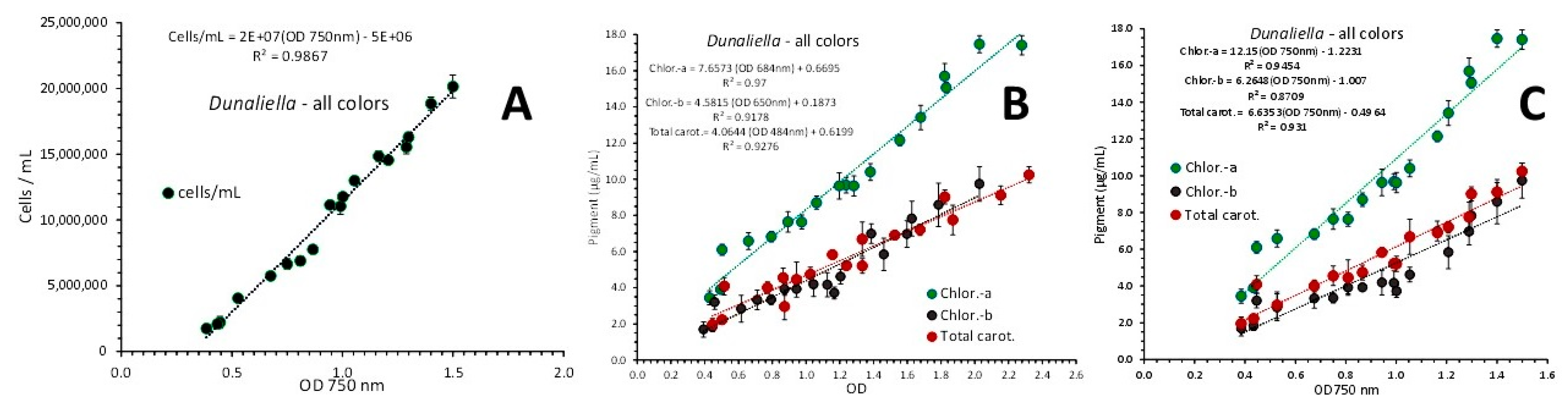

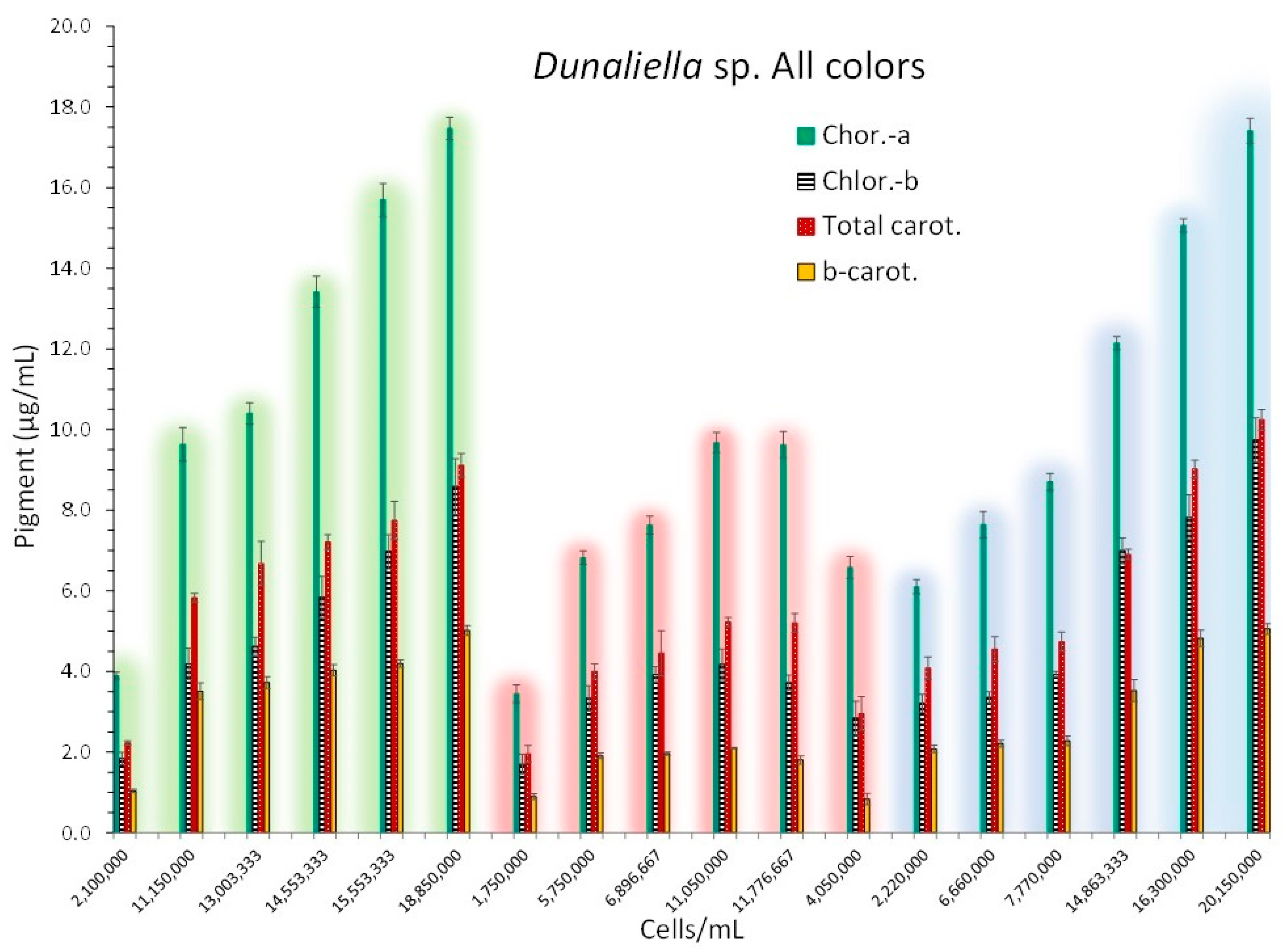

3.1. Dunaliella sp.

3.1.1. Effect of low (2000 lux) and high (8000 lux) white light illumination

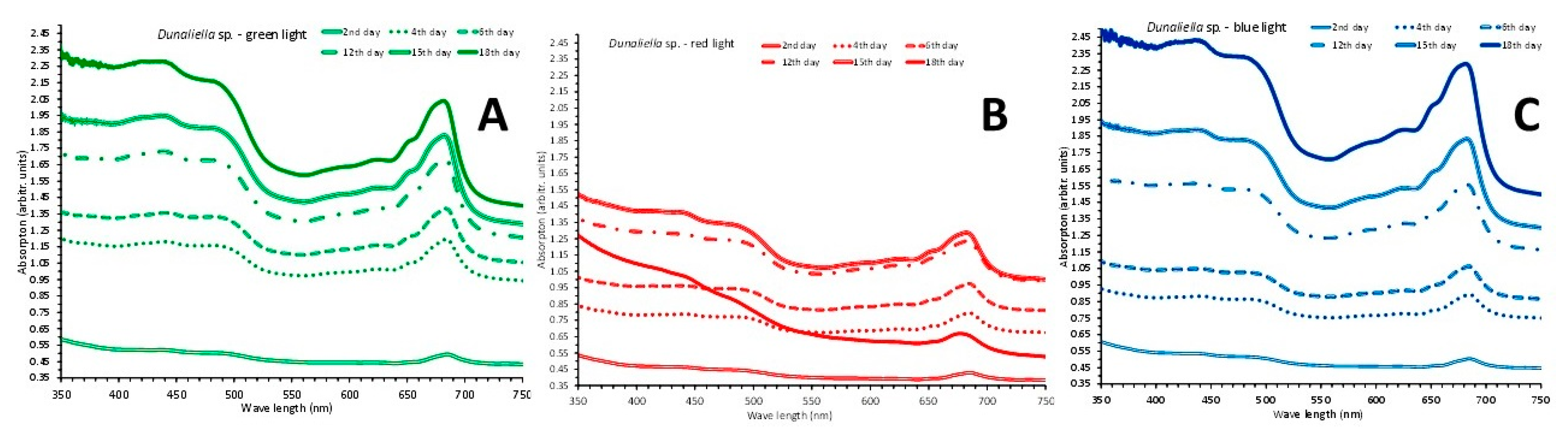

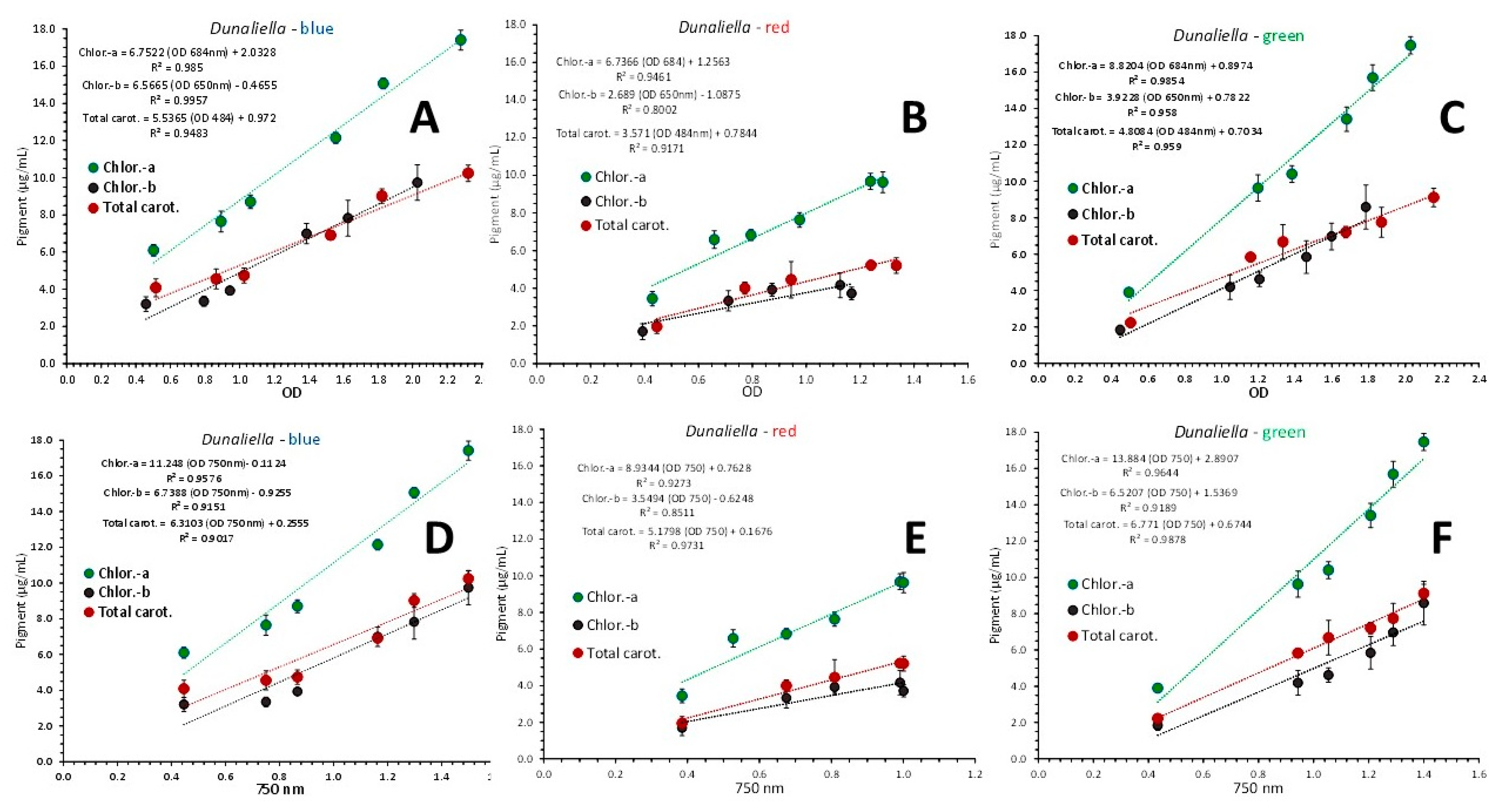

3.1.2. Effect of colored (green, blue and red) light illumination

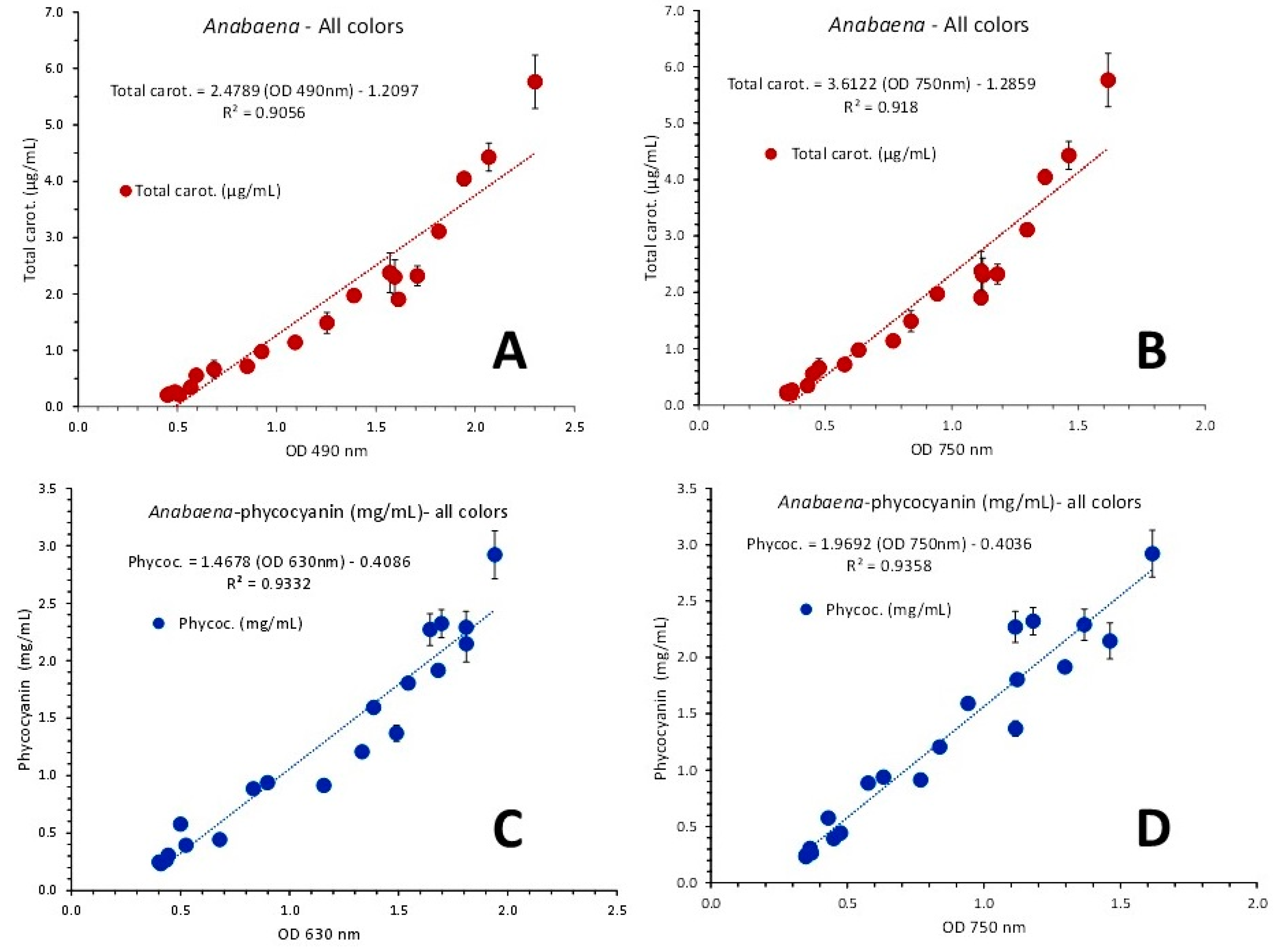

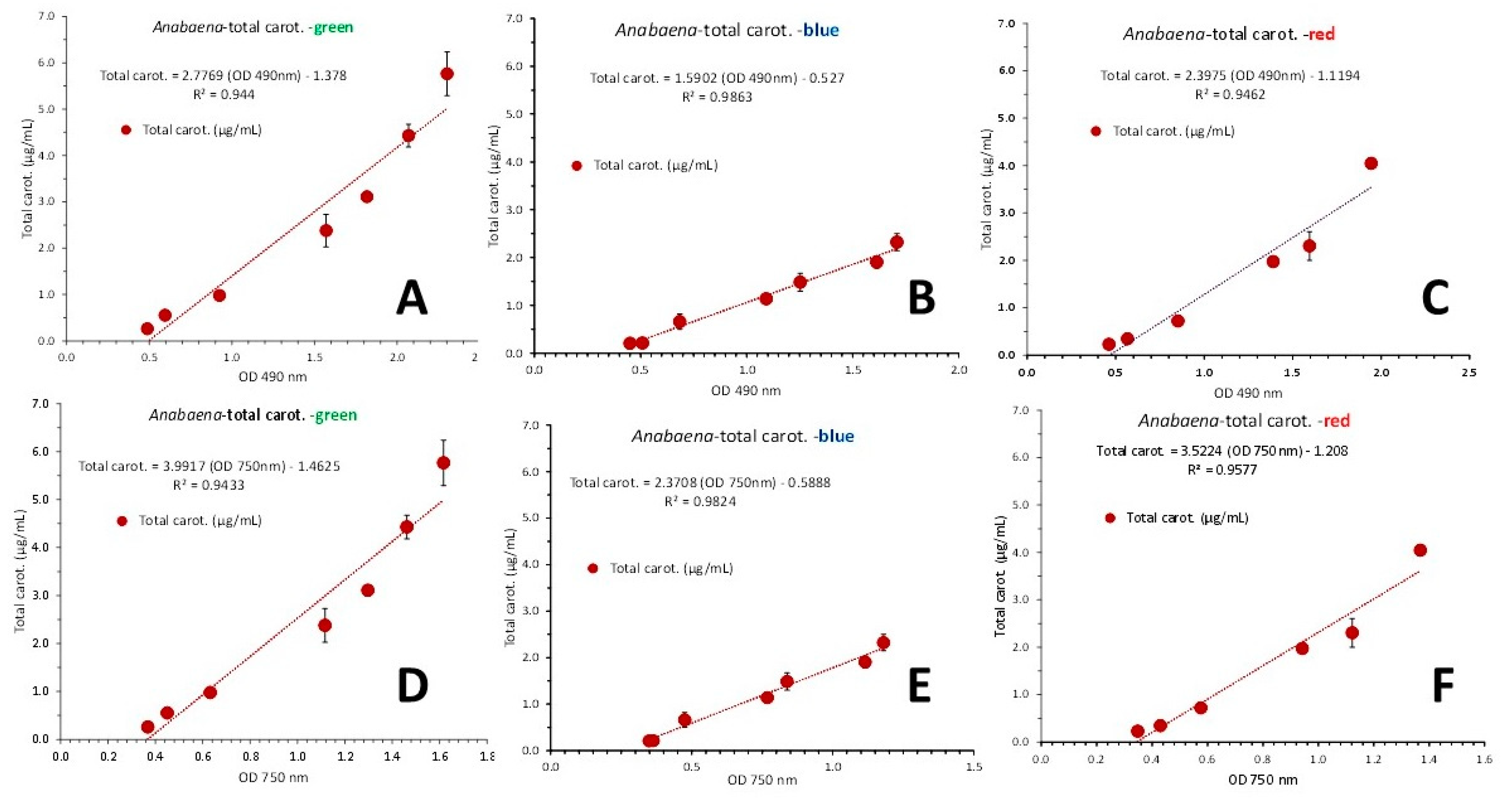

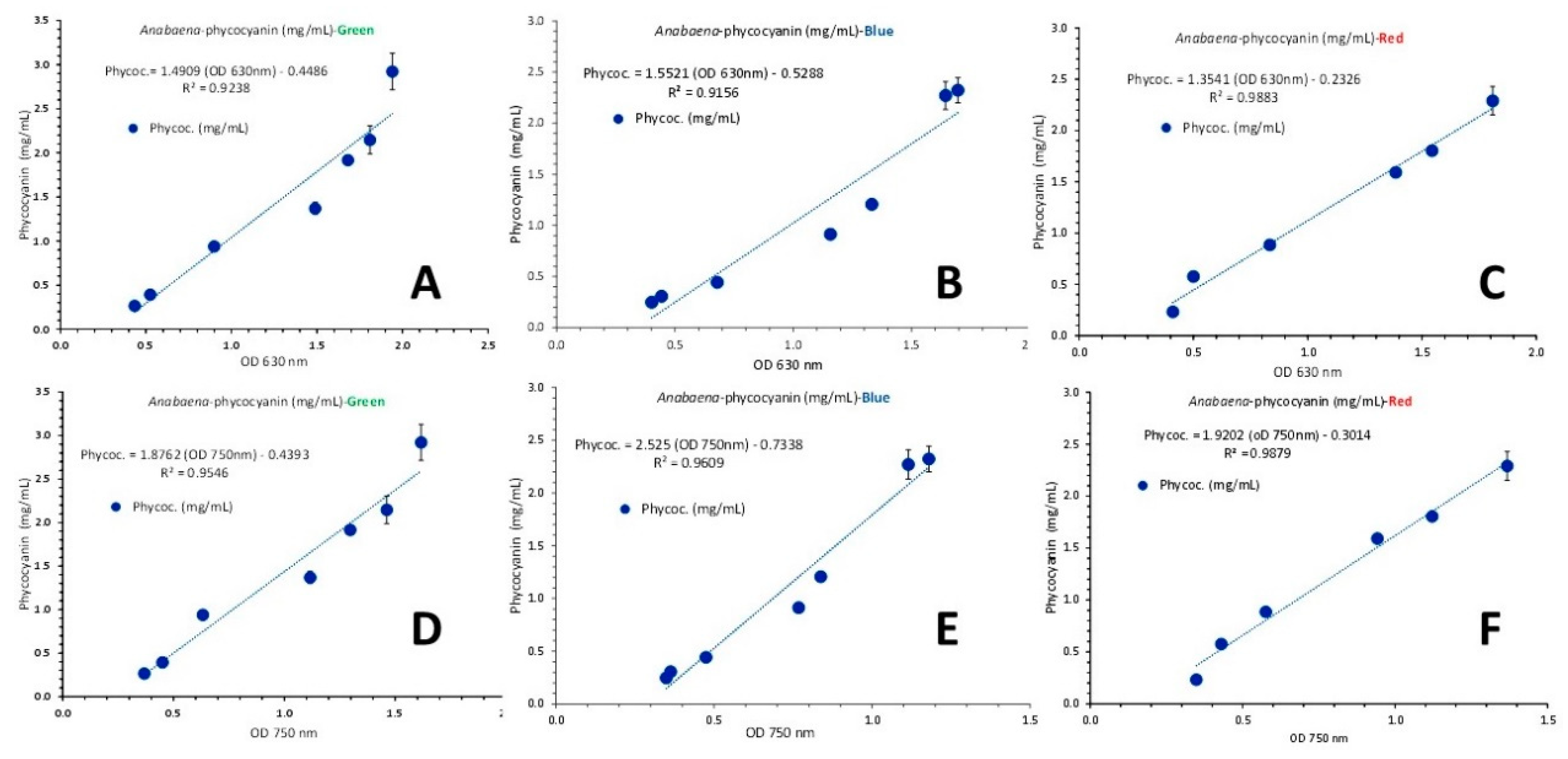

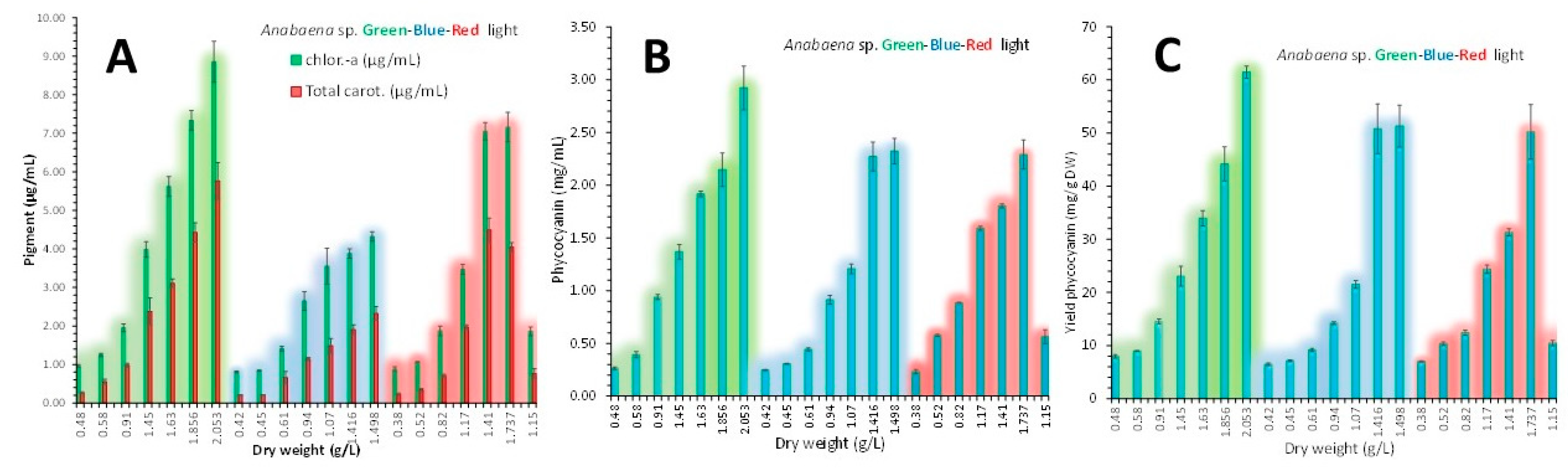

3.2. Anabaena sp.

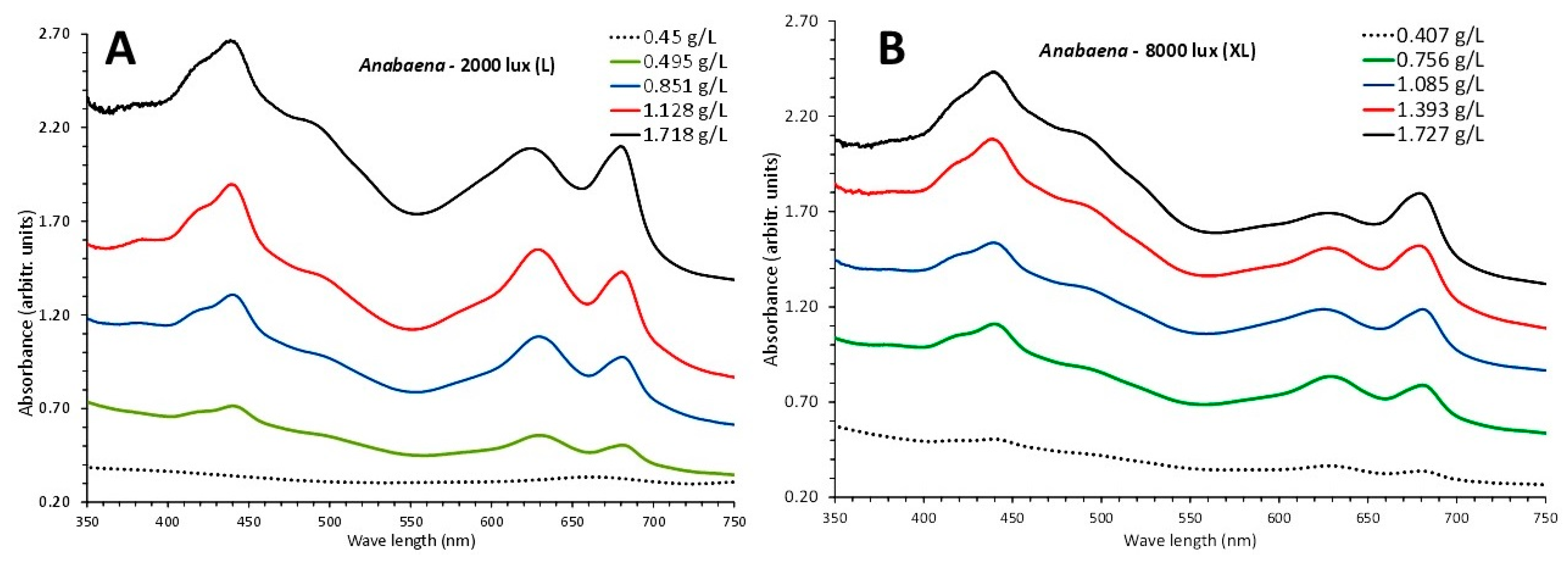

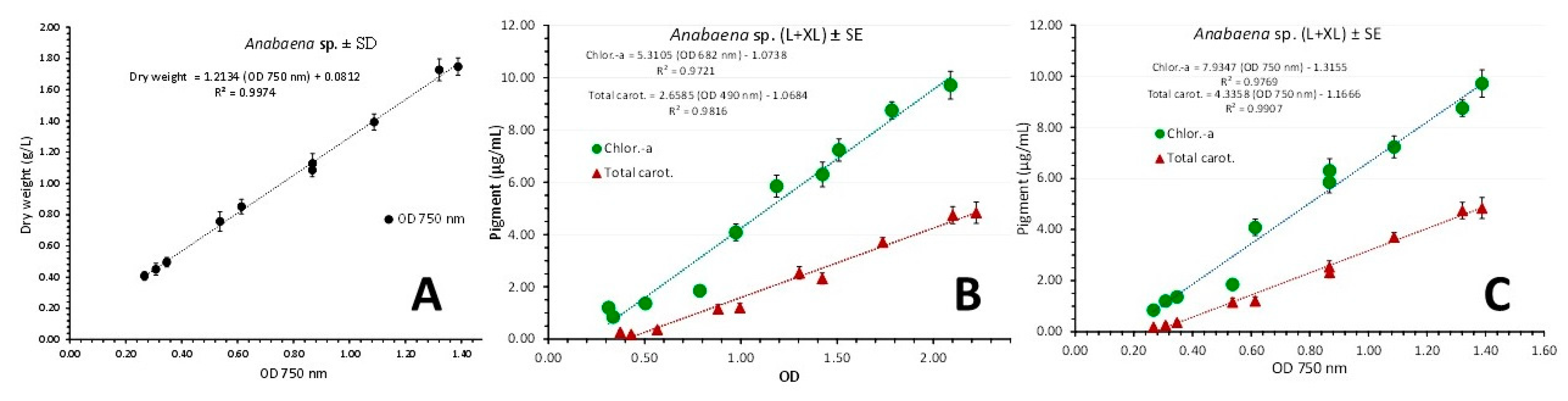

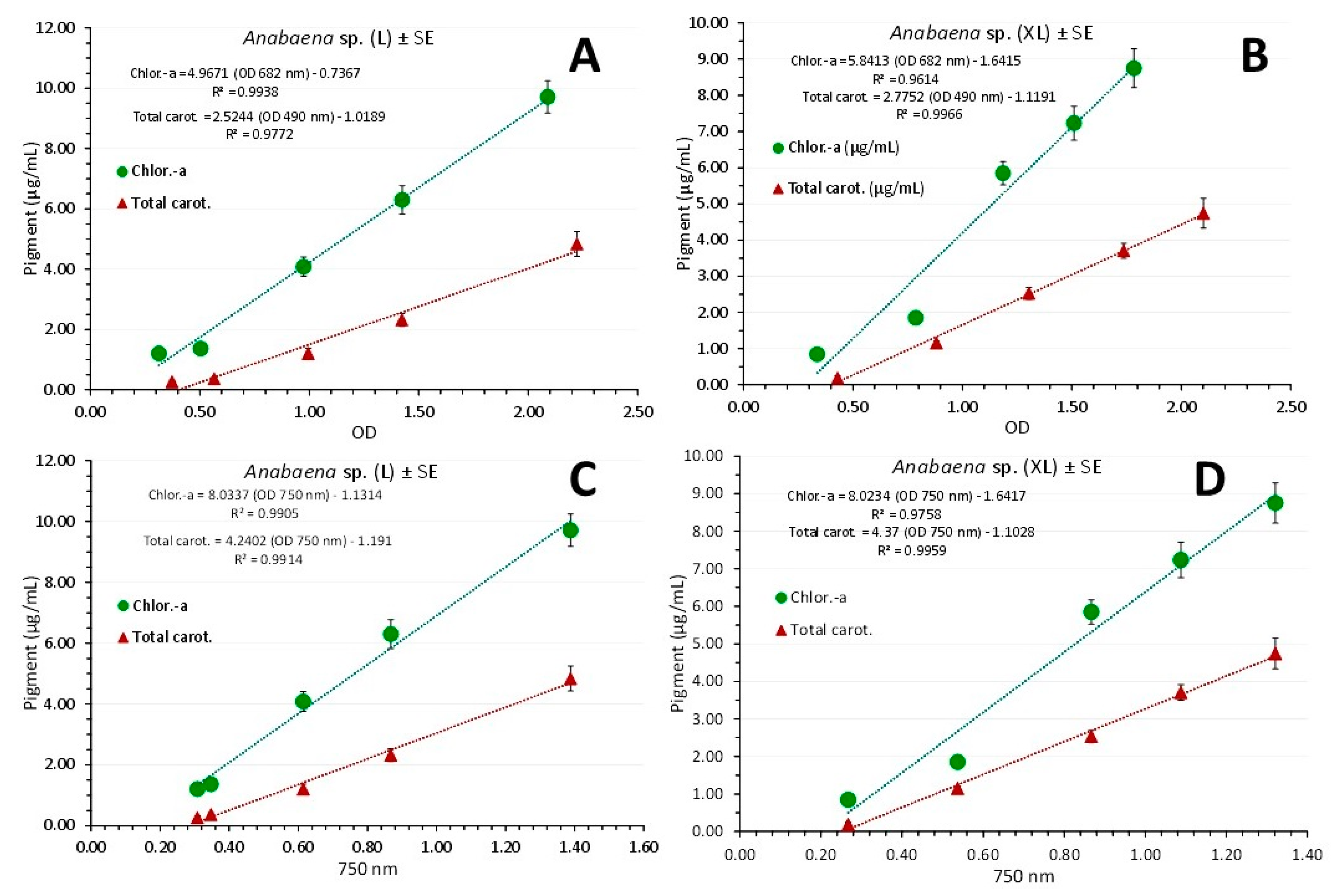

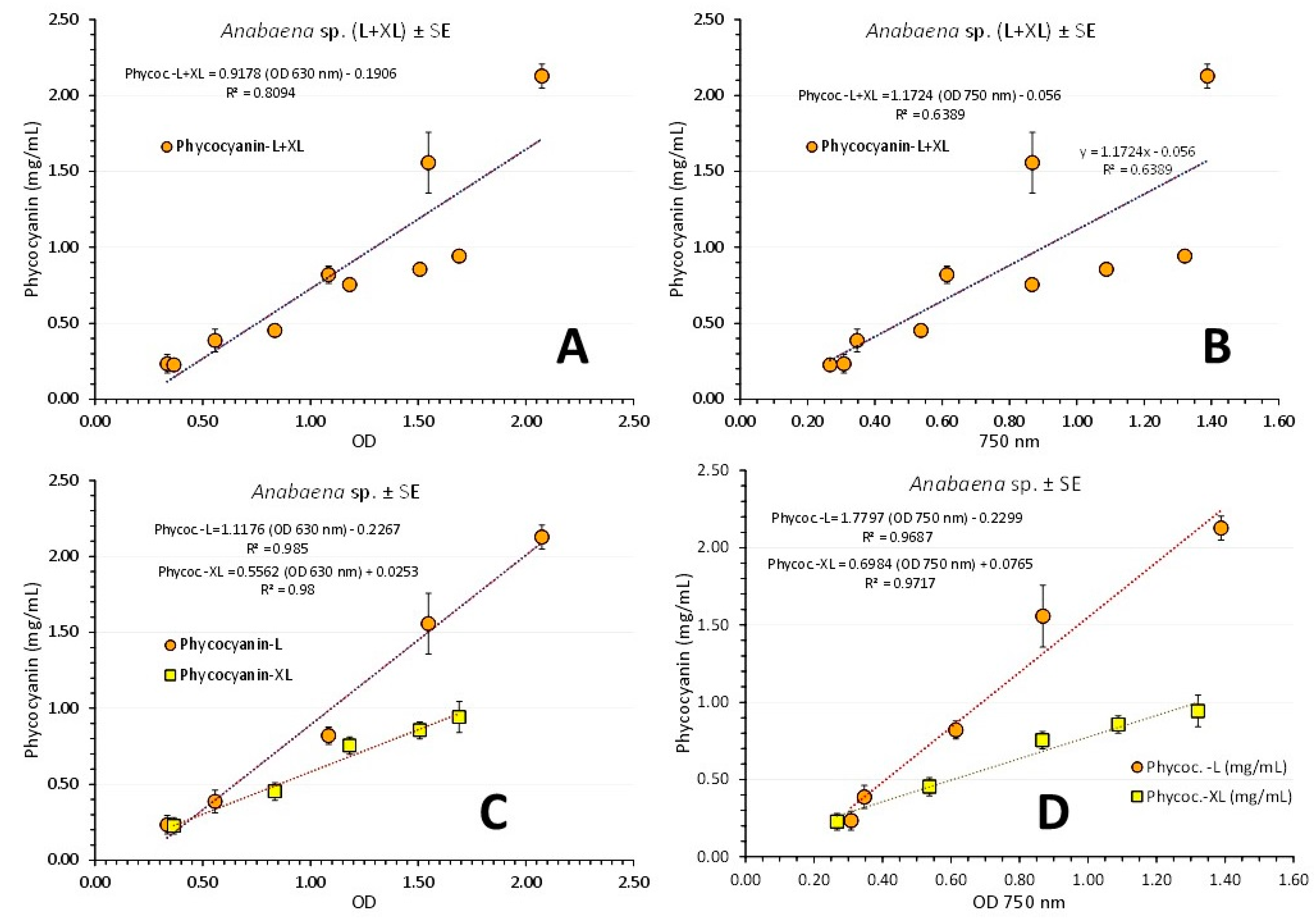

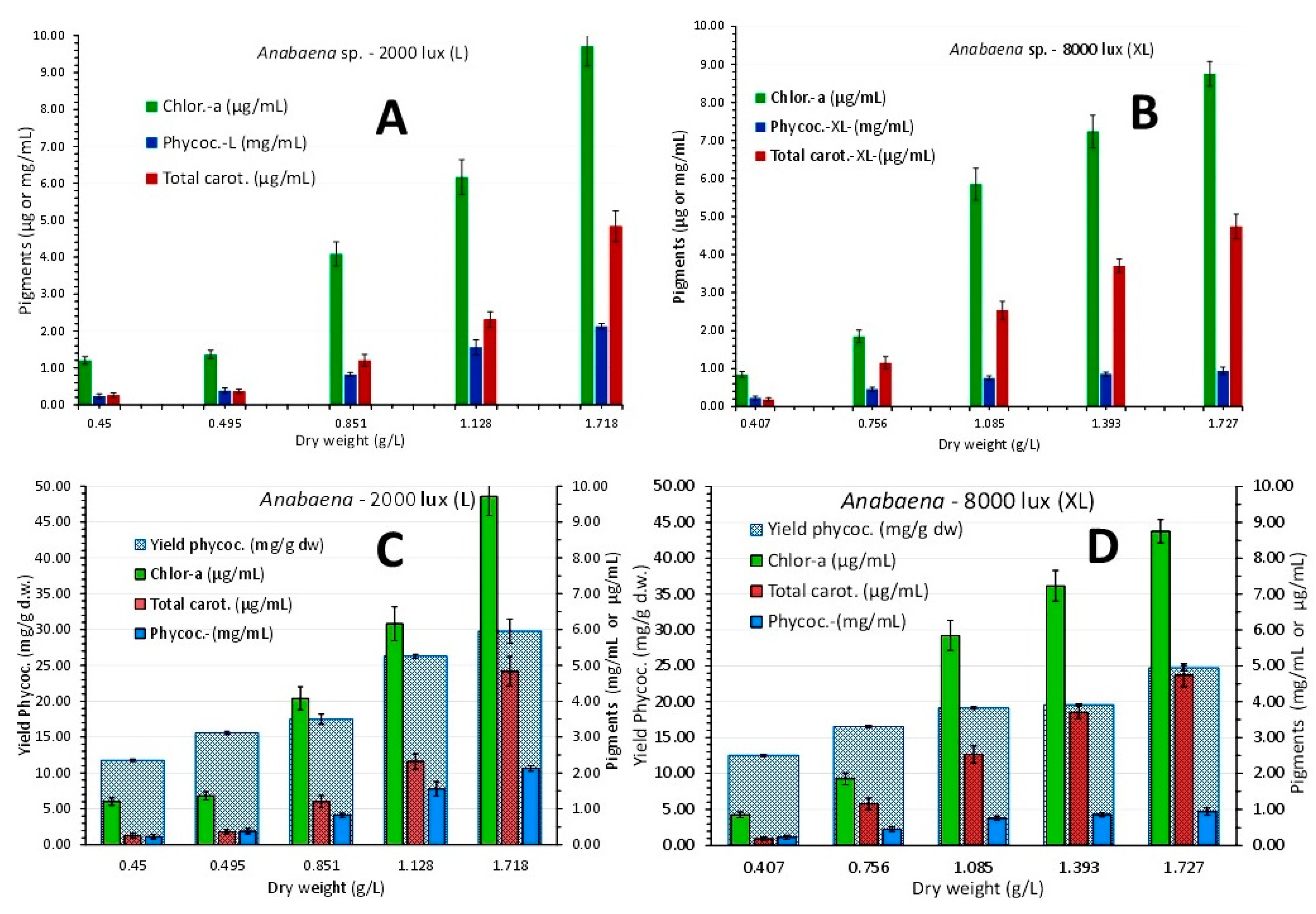

3.2.1. Effect of low (2000 lux) and high (8000 lux) white light illumination

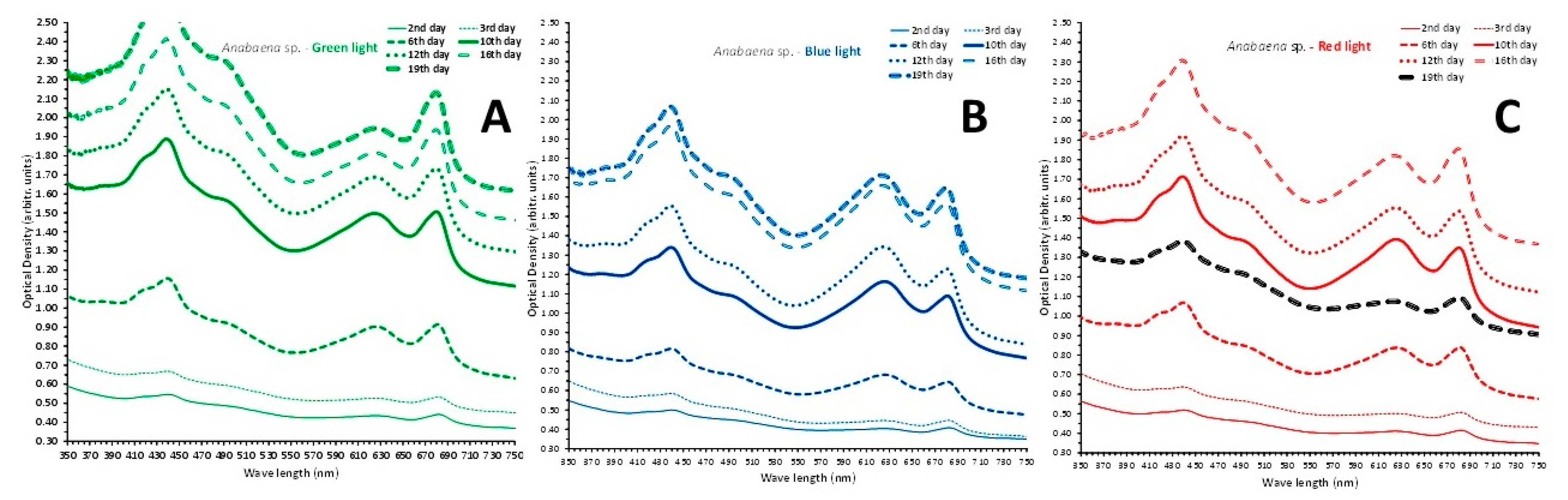

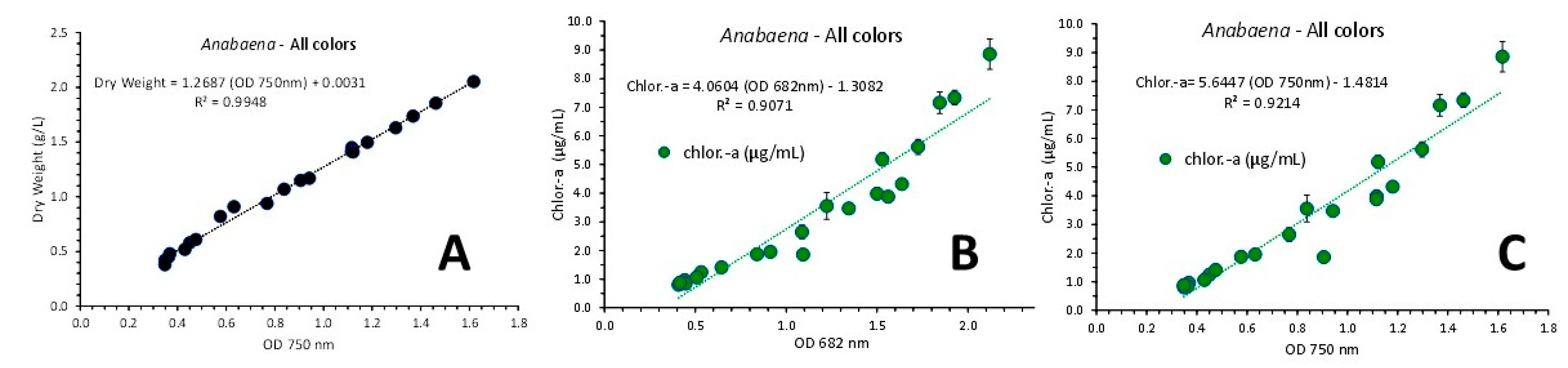

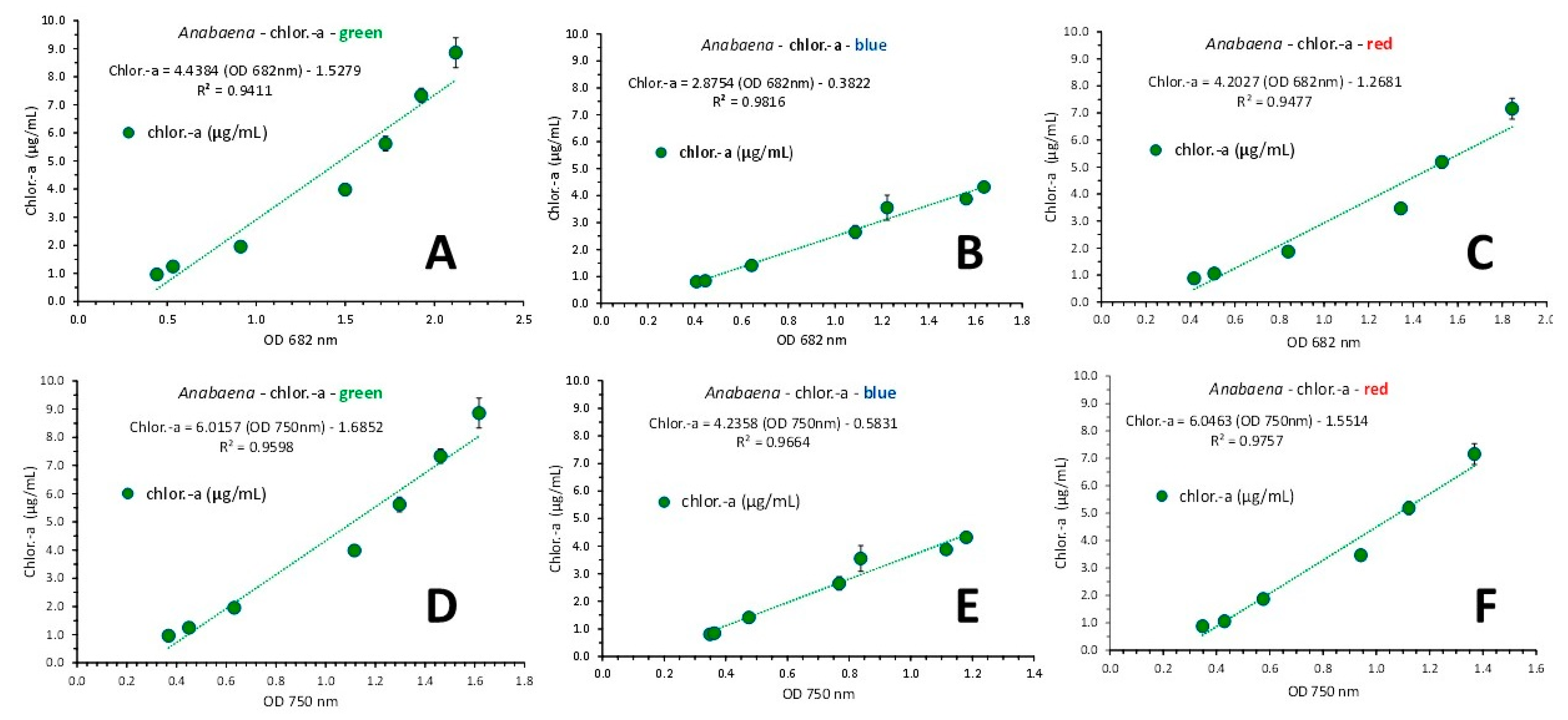

3.2.2. Effect of colored (green, blue and red) light illumination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moreno-Garcia, L.; Adjallé, K.; Barnabé, S.; Raghavan, G.S.V. Microalgae Biomass Production for a Biorefinery System: Recent Advances and the Way towards Sustainability. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 76, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, M.; Vecchi, V.; Barera, S.; Dall’Osto, L. Biomass from Microalgae: The Potential of Domestication towards Sustainable Biofactories. Microb Cell Fact 2018, 17, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhao, W.; Mao, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, T.; Chen, F. High-Value Biomass from Microalgae Production Platforms: Strategies and Progress Based on Carbon Metabolism and Energy Conversion. Biotechnol Biofuels 2018, 11, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S.; Sayre, R.T. The Right Stuff; Realizing the Potential for Enhanced Biomass Production in Microalgae. Front Energy Res 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Wu, N.; Lan, C.Q. CO2 Bio-Mitigation Using Microalgae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2008, 79, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, J.; Chen, P.; Ji, C.; Kang, Q.; Lu, B.; Li, K.; Liu, J.; Ruan, R. Bio-Mitigation of Carbon Dioxide Using Microalgal Systems: Advances and Perspectives. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 76, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awal, S.; Christie, A. Suitability of Inland Saline Ground Water for the Growth of Marine Microalgae for Industrial Purposes. Journal of Aquaculture & Marine Biology 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, G.; Alam, Md.A.; Xiong, W.; Lv, Y.; Xu, J.-L. Microalgae Biomass Production: An Overview of Dynamic Operational Methods. In Microalgae Biotechnology for Food, Health and High Value Products; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp. 415–432. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, W. Sustainable Production of Microalgae Biomass for Biofuel and Chemicals through Recycling of Water and Nutrient within the Biorefinery Context: A Review. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 914–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; W. Hassan, S.; Banat, F. An Overview of Microalgae Biomass as a Sustainable Aquaculture Feed Ingredient: Food Security and Circular Economy. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 9521–9547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ummalyma, S.B.; Sirohi, R.; Udayan, A.; Yadav, P.; Raj, A.; Sim, S.J.; Pandey, A. Sustainable Microalgal Biomass Production in Food Industry Wastewater for Low-Cost Biorefinery Products: A Review. Phytochemistry Reviews 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.L.; Ong, H.C.; Zaman, H.B. Microalgae Biomass as Biofuel and the Green Applications. Energies (Basel) 2022, 15, 7280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroneze, M.M.; Dias, R.R.; Severo, I.A.; Queiroz, M.I. Microalgae-Based Processes for Pigments Production. In Pigments from Microalgae Handbook; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 241–264. [Google Scholar]

- Jeevanandam, J.; Choudhary, V.; Selvam, J.D.; Danquah, M.K. The Bioeconomy of Production of Microalgal Pigments. In Pigments from Microalgae Handbook; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 325–362. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, S.C.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Dias, M.M.; Barreiro, M.F. Microalgae-Derived Pigments: A 10-Year Bibliometric Review and Industry and Market Trend Analysis. Molecules 2020, 25, 3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulombier, N.; Jauffrais, T.; Lebouvier, N. Antioxidant Compounds from Microalgae: A Review. Mar Drugs 2021, 19, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourkarimi, S.; Hallajisani, A.; Alizadehdakhel, A.; Nouralishahi, A.; Golzary, A. Factors Affecting Production of Beta-Carotene from Dunaliella Salina Microalgae. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2020, 29, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, L.; Cummings, T.; Müller, K.; Reppke, M.; Volkmar, M.; Weuster-Botz, D. Production of Β-carotene with Dunaliella Salina CCAP19/18 at Physically Simulated Outdoor Conditions. Eng Life Sci 2021, 21, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandual, S.; Sanchez, E.O.L.; Andrews, H.E.; de la Rosa, J.D.P. Phycocyanin Content and Nutritional Profile of Arthrospira Platensis from Mexico: Efficient Extraction Process and Stability Evaluation of Phycocyanin. BMC Chem 2021, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, T.; Huang, J.; Su, B.; Wei, L.; Zhang, A.-H.; Zhang, D.-F.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, G. Enhanced Phycocyanin Production of Arthrospira Maxima by Addition of Mineral Elements and Polypeptides Using Response Surface Methodology. Front Mar Sci 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C.; Louda, J. Microalgal Pigment Ratios in Relation to Light Intensity: Implications for Chemotaxonomy. Aquat Biol 2010, 11, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenpour, S.F.; Richards, B.; Willoughby, N. Spectral Conversion of Light for Enhanced Microalgae Growth Rates and Photosynthetic Pigment Production. Bioresour Technol 2012, 125, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotos, G.N. A Preliminary Survey on the Planktonic Biota in a Hypersaline Pond of Messolonghi Saltworks (W. Greece). Diversity (Basel) 2021, 13, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotos, G.; Avramidou, D.; Mastropetros, S.G.; Tsigkou, K.; Kouvara, K.; Makridis, P.; Kornaros, M. Isolation, Identification, and Chemical Composition Analysis of Nine Microalgal and Cyanobacterial Species Isolated in Lagoons of Western Greece. Algal Res 2023, 69, 102935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markou, G. Effect of Various Colors of Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs) on the Biomass Composition of Arthrospira Platensis Cultivated in Semi-Continuous Mode. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2014, 172, 2758–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morowvat, M.H.; Ghasemi, Y. Culture Medium Optimization for Enhanced β-Carotene and Biomass Production by Dunaliella Salina in Mixotrophic Culture. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2016, 7, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoveská, L.; Ross, M.E.; Stanley, M.S.; Pradelles, R.; Wasiolek, V.; Sassi, J.-F. Microalgal Carotenoids: A Review of Production, Current Markets, Regulations, and Future Direction. Mar Drugs 2019, 17, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.K.; Albarico, F.P.J.B.; Perumal, P.K.; Vadrale, A.P.; Nian, C.T.; Chau, H.T.B.; Anwar, C.; Wani, H.M. ud din; Pal, A.; Saini, R.; et al. Algae as an Emerging Source of Bioactive Pigments. Bioresour Technol 2022, 351, 126910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Zhou, X.-R.; Moncalian, G.; Su, L.; Chen, W.-C.; Zhu, H.-Z.; Chen, D.; Gong, Y.-M.; Huang, F.-H.; Deng, Q.-C. Reprogramming Microorganisms for the Biosynthesis of Astaxanthin via Metabolic Engineering. Prog Lipid Res 2021, 81, 101083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TOENNIES, G.; GALLANT, D.L. The Relation between Photometric Turbidity and Bacterial Concentration. Growth 1949, 13, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, M.J.; Garcin, C.; van Hille, R.P.; Harrison, S.T.L. Interference by Pigment in the Estimation of Microalgal Biomass Concentration by Optical Density. J Microbiol Methods 2011, 85, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clesceri, L.S.; Greenberg, A.E.; Eaton, A.D. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 20th ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, K.H.; Dillon, P.J. An Evaluation of Phosphorus-Chlorophyll-Phytoplankton Relationships for Lakes. Internationale Revue der gesamten Hydrobiologie und Hydrographie 1978, 63, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, H.; Yusoff, F.MD.; Banerjee, S.; Khatoon, H.; Shariff, M. Availability and Utilization of Pigments from Microalgae. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2016, 56, 2209–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagels, F.; Salvaterra, D.; Amaro, H.M.; Guedes, A.C. Pigments from Microalgae. In Handbook of Microalgae-Based Processes and Products; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 465–492. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.-Y.; Sim, S.-J.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, B.W. Hydrocarbon Production from Secondarily Treated Piggery Wastewater by the Green Alga Botryococcus Braunii. J Appl Phycol 2003, 15, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.-Y.; Kao, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Kuan, T.-C.; Ong, S.-C.; Lin, C.-S. Reduction of CO2 by a High-Density Culture of Chlorella Sp. in a Semicontinuous Photobioreactor. Bioresour Technol 2008, 99, 3389–3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, C.-H.; Wu, W.-T. Cultivation of Microalgae for Oil Production with a Cultivation Strategy of Urea Limitation. Bioresour Technol 2009, 100, 3921–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detweiler, A.M.; Mioni, C.E.; Hellier, K.L.; Allen, J.J.; Carter, S.A.; Bebout, B.M.; Fleming, E.E.; Corrado, C.; Prufert-Bebout, L.E. Evaluation of Wavelength Selective Photovoltaic Panels on Microalgae Growth and Photosynthetic Efficiency. Algal Res 2015, 9, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Sá, M.; Teles (Cabanelas, I.I.; Wijffels, R.H.; Barbosa, M.J. Production and Monitoring of Biomass and Fucoxanthin with Brown Microalgae under Outdoor Conditions. Biotechnol Bioeng 2021, 118, 1355–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirooka, S.; Tomita, R.; Fujiwara, T.; Ohnuma, M.; Kuroiwa, H.; Kuroiwa, T.; Miyagishima, S. Efficient Open Cultivation of Cyanidialean Red Algae in Acidified Seawater. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 13794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotos, G.N.; Avramidou, D.; Bekiari, V. Calibration Curves of Culture Density Assessed by Spectrophotometer for Three Microalgae (Nephroselmis Sp., Amphidinium Carterae and Phormidium Sp.). European Journal of Biology and Biotechnology 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plöhn, M.; Escudero-Oñate, C.; Funk, C. Biosorption of Cd(II) by Nordic Microalgae: Tolerance, Kinetics and Equilibrium Studies. Algal Res 2021, 59, 102471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitomi, T.; Karita, H.; Mori-Moriyama, N.; Sato, N.; Yoshimoto, K. Reduced Cytotoxicity of Polyethyleneimine by Covalent Modification of Antioxidant and Its Application to Microalgal Transformation. Sci Technol Adv Mater 2021, 22, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markina, Zh. V.; Maslennikov, S.I.; Botsun, L.A. Application of the Spectrophotometric Method for Determination of the Cell Numbers of Microalgae in the Genus Tetraselmis (Chlorophyta): Calibration Curves and Equations for Calculation. Russ J Mar Biol 2022, 48, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioccioli, M.; Hankamer, B.; Ross, I.L. Flow Cytometry Pulse Width Data Enables Rapid and Sensitive Estimation of Biomass Dry Weight in the Microalgae Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii and Chlorella Vulgaris. PLoS One 2014, 9, e97269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotos, G.N. Culture Growth of the Cyanobacterium Phormidium Sp. in Various Salinity and Light Regimes and Their Influence on Its Phycocyanin and Other Pigments Content. J Mar Sci Eng 2021, 9, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotos, G.N.; Avramidou, D. The Effect of Various Salinities and Light Intensities on the Growth Performance of Five Locally Isolated Microalgae [Amphidinium Carterae, Nephroselmis Sp., Tetraselmis Sp. (Var. Red Pappas), Asteromonas Gracilis and Dunaliella Sp.] in Laboratory Batch Cultures. J Mar Sci Eng 2021, 9, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotos, G.N.; Antoniadis, T.I. The Effect of Colored and White Light on Growth and Phycobiliproteins, Chlorophyll and Carotenoids Content of the Marine Cyanobacteria Phormidium Sp. and Cyanothece Sp. in Batch Cultures. Life 2022, 12, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotos, G.N.; Avramidou, D.; Samara, A. The Effect of Salinity and Light Intensity on the Batch Cultured Cyanobacteria Anabaena Sp. and Cyanothece Sp. Hydrobiology 2022, 1, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, I.; Steinweg, C.; Posten, C. Mono- and Dichromatic LED Illumination Leads to Enhanced Growth and Energy Conversion for High-Efficiency Cultivation of Microalgae for Application in Space. Biotechnol J 2016, 11, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, J. Analysis of Light Absorption and Photosynthetic Activity by Isochrysis Galbana under Different Light Qualities. Aquac Res 2020, 51, 2893–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltsev, Y.; Maltseva, K.; Kulikovskiy, M.; Maltseva, S. Influence of Light Conditions on Microalgae Growth and Content of Lipids, Carotenoids, and Fatty Acid Composition. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remias, D.; Lütz-Meindl, U.; Lütz, C. Photosynthesis, Pigments and Ultrastructure of the Alpine Snow Alga Chlamydomonas Nivalis. Eur J Phycol 2005, 40, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.; Dubinsky, Z.; Iluz, D. Light as a Limiting Factor for Epilithic Algae in the Supralittoral Zone of Littoral Caves. Front Mar Sci 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsoviti, M.N.; Papapolymerou, G.; Karapanagiotidis, I.T.; Katsoulas, N. Effect of Light Intensity and Quality on Growth Rate and Composition of Chlorella Vulgaris. Plants 2019, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, N.L.; Campbell, D.A.; Hughes, D.J.; Kuzhiumparambil, U.; Halsey, K.H.; Ralph, P.J.; Suggett, D.J. Divergence of Photosynthetic Strategies amongst Marine Diatoms. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0244252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiusi, F.; Sampietro, G.; Marturano, G.; Biondi, N.; Rodolfi, L.; D’Ottavio, M.; Tredici, M.R. Growth, Photosynthetic Efficiency, and Biochemical Composition of Tetraselmis Suecica F&M-M33 Grown with LEDs of Different Colors. Biotechnol Bioeng 2014, 111, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, C.L.; Atta, M.; Bukhari, A.; Taisir, M.; Yusuf, A.M.; Idris, A. Enhancing Growth and Lipid Production of Marine Microalgae for Biodiesel Production via the Use of Different LED Wavelengths. Bioresour Technol 2014, 162, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Fleurent, G.; Awwad, F.; Cheng, M.; Meddeb-Mouelhi, F.; Budge, S.M.; Germain, H.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Red Light Variation an Effective Alternative to Regulate Biomass and Lipid Profiles in Phaeodactylum Tricornutum. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulou, C.; Christoforou, E.; Dominoni, D.M.; Kaiserli, E.; Czyzewski, J.; Mirzai, N.; Spatharis, S. Wavelength-Dependent Effects of Artificial Light at Night on Phytoplankton Growth and Community Structure. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2021, 288, 20210525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubián, L.M.; Montero, O.; Moreno-Garrido, I.; Huertas, I.E.; Sobrino, C.; González-del Valle, M.; Parés, G. Nannochloropsis (Eustigmatophyceae) as Source of Commercially Valuable Pigments. J Appl Phycol 2000, 12, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J. ; Zheng, lvhong Acclimation to NaCl and Light Stress of Heterotrophic Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii for Lipid Accumulation. J Biosci Bioeng 2017, 124, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Zhu, R.; Lu, J.; Lei, A.; Zhu, H.; Hu, Z.; Wang, J. Effects of Different Abiotic Stresses on Carotenoid and Fatty Acid Metabolism in the Green Microalga Dunaliella Salina Y6. Ann Microbiol 2020, 70, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzayisenga, J.C.; Farge, X.; Groll, S.L.; Sellstedt, A. Effects of Light Intensity on Growth and Lipid Production in Microalgae Grown in Wastewater. Biotechnol Biofuels 2020, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cointet, E.; Wielgosz-Collin, G.; Bougaran, G.; Rabesaotra, V.; Gonçalves, O.; Méléder, V. Effects of Light and Nitrogen Availability on Photosynthetic Efficiency and Fatty Acid Content of Three Original Benthic Diatom Strains. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0224701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).