1. Introduction

Airborne particles are a serious environmental health risk globally, contributing in excess of 7 million premature deaths each year [

1]. Fine particulate matter (PM

, particles with a diameter of less than 2.5 micrometers) has been causally linked to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [

2] and are therefore regulated under the provisions of the Clean Air Act [

3] to protect human health and wellbeing. As a result, the emissions of PM

from many antropogenic sources, such as transpiration and industry, have been on a steady decline [

4] and wildfires have become the single largest source [

5], potentially off setting reduction in emissions from other sources.

High concentrations of fine particles and gasses found in smoke have also produced alarming impacts on health [

6,

7]. During peak wildfire seasons, smoke exposure can exacerbate health problems, causing a spike in emergency department visits [

8]. In an epidemiological study of health impacts, [

9] estimated that 2.2 % of annual respiratory health burden, or 92 ED visits per 100,000 people, is attributed to ambient PM and that wildfire days account for over 15% of that burden. However, providing a definite answer as to how much of particle pollution can be attributed to wildfires remains a challenging problem because instruments measure a total ambient concentration which is composed of natural, anthropogenic, and wildfire sources.

Previous research has studied the contribution of wildfires on PM

concentrations by integrating remote sensing data on the location and extend of smoke plumes and PM

readings from Air Quality System (AQS) monitors deployed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). These studies revealed that wildfires contribute to 40% of unhealthy days and substantially increase PM

concentrations [

10,

11]. Wildfire smoke impacts are dynamic and often affect areas without a monitoring station, as AQS monitors have limited spatial coverage due to the high cost and difficulty in installation. It is important to make air quality information available to the public quickly during wildfires, therefore AQS alone provides insufficient data source for monitoring wildfire emissions.

The increased incidence of days with poor air quality due to wildfires has created a demand and public interest for monitoring particulate pollution. Perhaps the most prevalent sensors are PurpleAir (PA), which are installed by members of the public, providing a near real-time monitoring of PM

with extensive spatial coverage [

12]. However, it is known that PA sensors are less reliable compared to the AQS, and thus correction to the sensor readings is needed [

13,

14]. [

15] developed a correction equation using meteorological conditions including relative humidity and temperature, as both measurements affect the accuracy of the instrument; however, this calibration is developed for a US-wide correction and without smoke impacts. Another simple linear correction model under smoke impacted conditions was proposed in [

16]. As the sensor performance can be affected by geographic and environmental conditions, it is more reasonable to relax the assumption of a constant spatially varying bias, but rather capture the spatiotemporally varying bias.

Smoke impacts are dynamic and often affect areas without a monitoring station, as AQS monitors have limited spatial coverage. Previous studies have either separated anthropogenic PM from smoke emissions using chemical transport models or by subtracting out historically observed averages [

17]. However, neither approach provides a definite answer as to how much of particle pollution can be attributed to wildfires. Data fusion is a widely used method that integrates information from different types of sensors to provide a robust and complete description of a process of interest [

18,

19]. It has been used extensively to estimate spatially and temporally resolved air quality surfaces. For example, [

20,

21,

22,

23] use data fusion method to study the complex relationship between monitoring data and outputs from Community Multi-Scale Air Quality (CMAQ), a deterministic chemical transport model. [

24] combines observations from two noisy datasets to predict the true aerosol process. More recently, several researchers have exploited the usefulness of low-cost sensors such as Purple Air to map air quality and quantify the uncertainty of estimation [

25,

26,

27]. Most similar to our approach is Stein et al (2005), who also use a spectral transformation in time and spatial processes to capture dependence between stations for a single fixed monitoring network [

28]. We extend this approach to handle multiple data networks.

This study aims to provide an estimate of wildfire contribution on air quality by supplementing the remotely sensed smoke plume indicators with PurpleAir data. We propose a multi-resolution Bayesian approach fusing information from both AQS monitors and PA sensors to estimate the contribution to PM

caused by wildfires. We apply a Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) to account for temporal correlation, transforming the data from the time domain to the frequency domain, and model the spatial correlation in the frequency domain. To quantify the relative increase in PM

concentrations due to wildfires, we propose regression and matching estimators, as discussed in

Section 2.3. Our findings will not only enhance understanding of the relationship between wildfires and air pollution but also inform policy and decision-making related to wildfire management, public health, and climate change impacts.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: In

Section 2, we present an overview of the Hazard Mapping System (HMS) and its smoke plume data. We also delve into the specifics of the AQS and PurpleAir sensors, contrasting their features and functionality. The latter part of

Section 2 elucidates our use of the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) and the data fusion model, with detailed insights into our Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach.

Section 3 presents our findings, including the estimated smoke plume parameters and the calculated contribution of wildfires to PM

concentrations, as determined by both regression and matching estimators. We also offer a comparison of various models, illustrating the effectiveness of the PurpleAir sensors and the benefits of our proposed data fusion method. Finally, in

Section 4, we discuss the implications of our findings, the limitations of our study, and potential directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data sources and exploratory analysis

Our analysis incorporates data from three distinct sources: satellite-derived smoke plume indicators obtained through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hazard Mapping System (HMS), PM measurements from Air Quality System (AQS) monitoring stations, and PM readings from PurpleAir (PA) monitoring stations. We collect hourly data and average them to daily level from each source for 2020 and 2021 fire seasons, spanning July 1 to October 31. The original PM readings from both AQS and PA stations are right-skewed so we apply log-transformation to all PM readings.

2.1.1. Satellite-derived smoke plume indicators

Exposure to wildland fire smoke is assessed using smoke plume indicators supplied by the Hazard Mapping System (HMS) [

29]. This automated data product integrates observations from multiple polar and geostationary satellites to generate daily polygons representing smoke plume extents in near-real time. Distinct polygons are provided for low-, medium-, and high-density plumes.

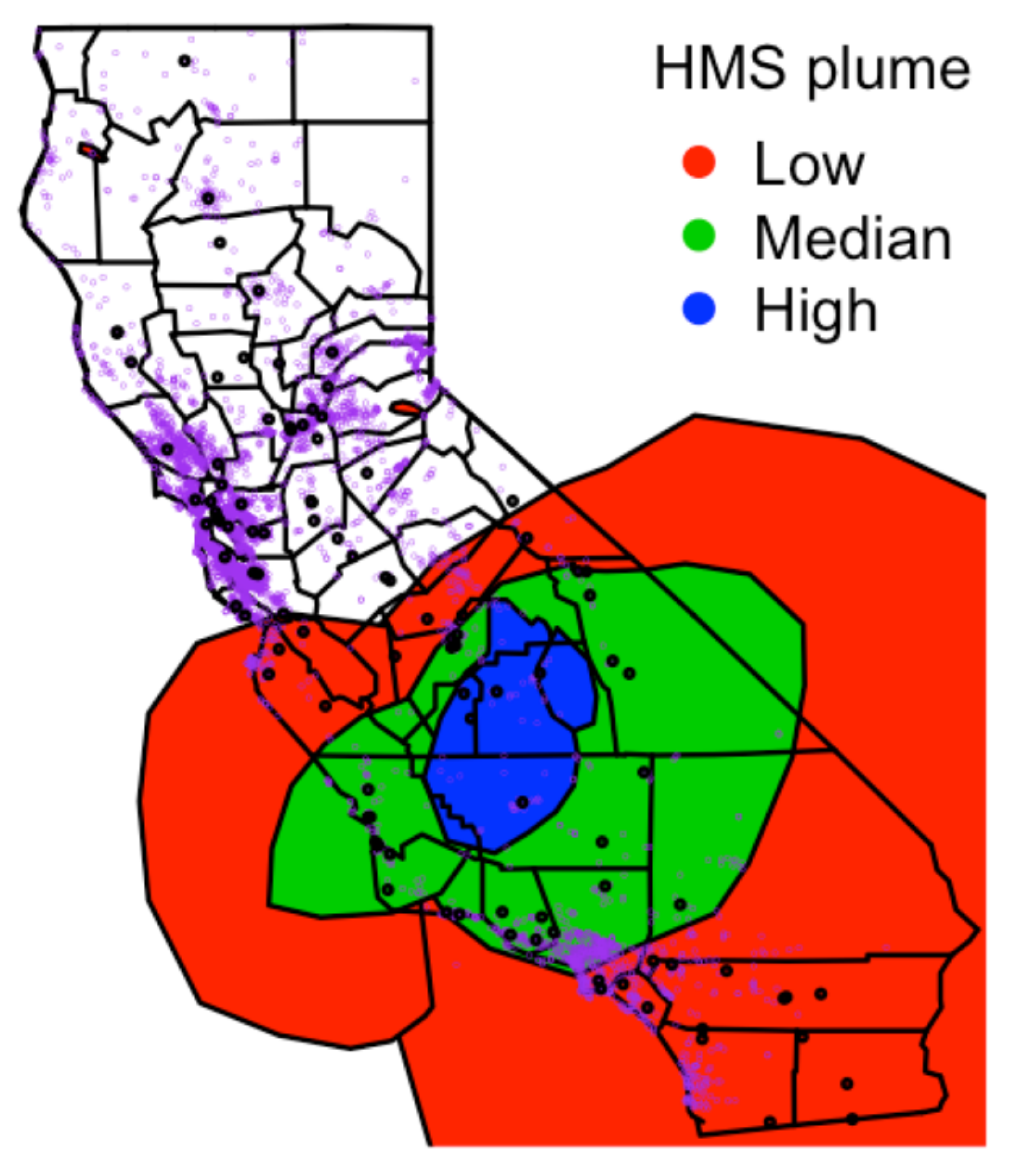

Figure 1 shows the HMS smoke plumes for September 20, 2021. These smoke plume indicators tend to underestimate the actual intensity of smoke, as they primarily rely on satellite imagery with an approximate spatial resolution spanning several miles [

30]. Additionally, smoke visibility is limited to daytime hours, resulting in a significant underestimation of smoke levels during the night.

2.1.2. AQS monitoring stations

The Air Quality System (AQS) monitoring stations, deployed by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and state, local, and tribal air pollution control agencies, provide precise PM

measurements. However, their distribution is spatially sparse due to the high cost and complexity associated with their installation and maintenance. The black dots in

Figure 1 depict the distribution of AQS monitoring sites across California in 2021.

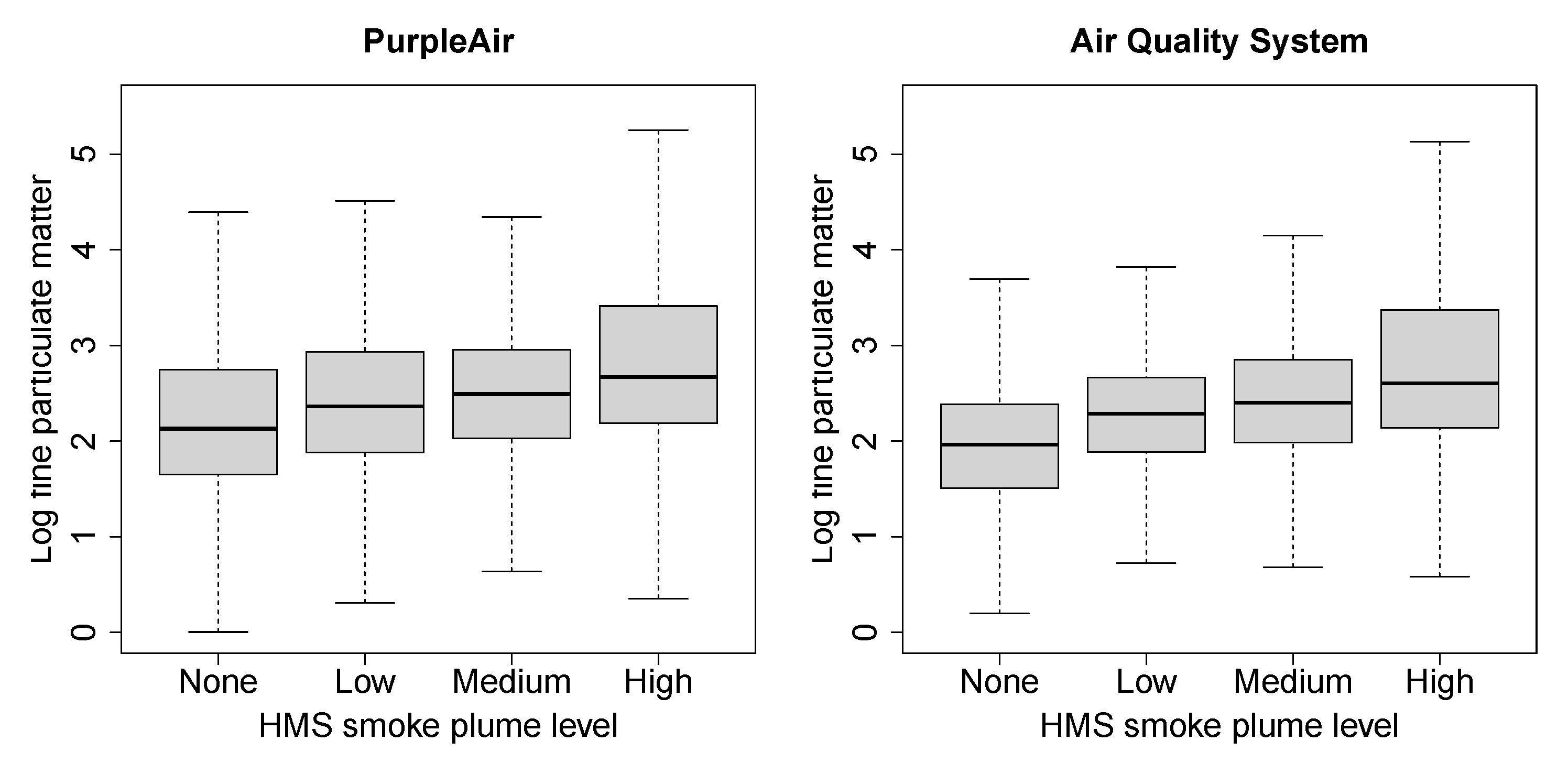

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of PM

levels, aggregated across stations, by smoke plume intensity.

2.1.3. PurpleAir sensors

PurpleAir (PA) sensors are low-cost monitoring devices deployed by individuals and organizations for continuous ambient air pollutant tracking. Despite their affordability and ease of installation, PA sensors offer less accurate PM

readings and are significantly influenced by environmental factors, such as temperature and humidity [

15]. We use bias corrected data for all analyses. However, this initial bias correction based on [

15] may be insufficient because it only depends on a linear trend in temperature and humidity and is constant across space and time. Therefore, our Bayesian data fusion model adds a more flexible spatiotemporal bias correction term.

In 2021, more than 7,800 outdoor PA sensors were operational in California. The purple dots in

Figure 1 represent the distribution of PA monitoring sites throughout the state. We have included only those PA stations that reported fewer than 18 missing days during the fire seasons, resulting in a total of 1,080 for 2020 and 712 PA stations for 2021.

Figure 2 displays the distribution of PM

, aggregated across stations for 2021, by smoke plume intensity. A similar pattern is observed in both PA stations and AQS stations where PM

measurements escalate in the presence of a smoke plume.

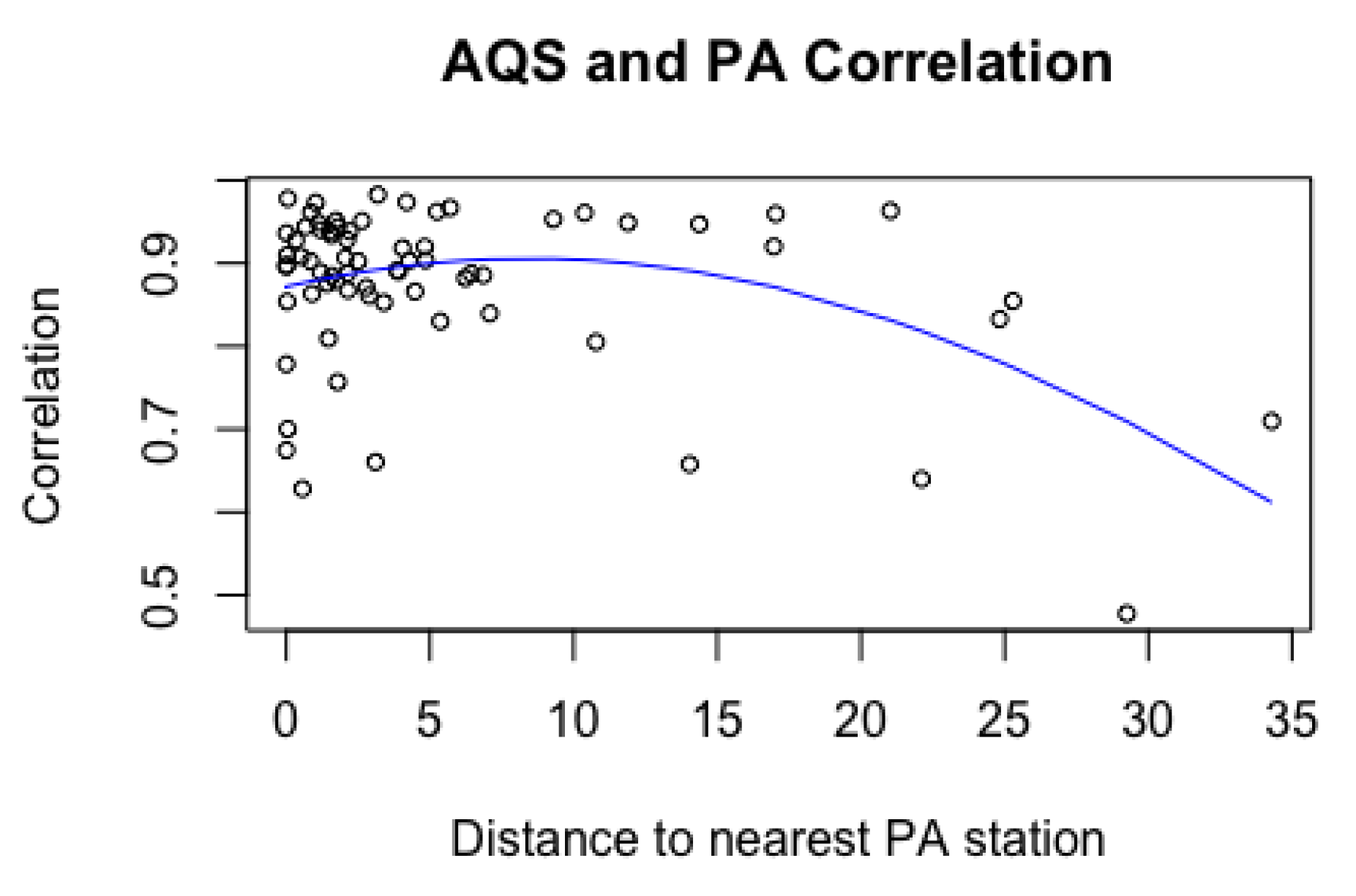

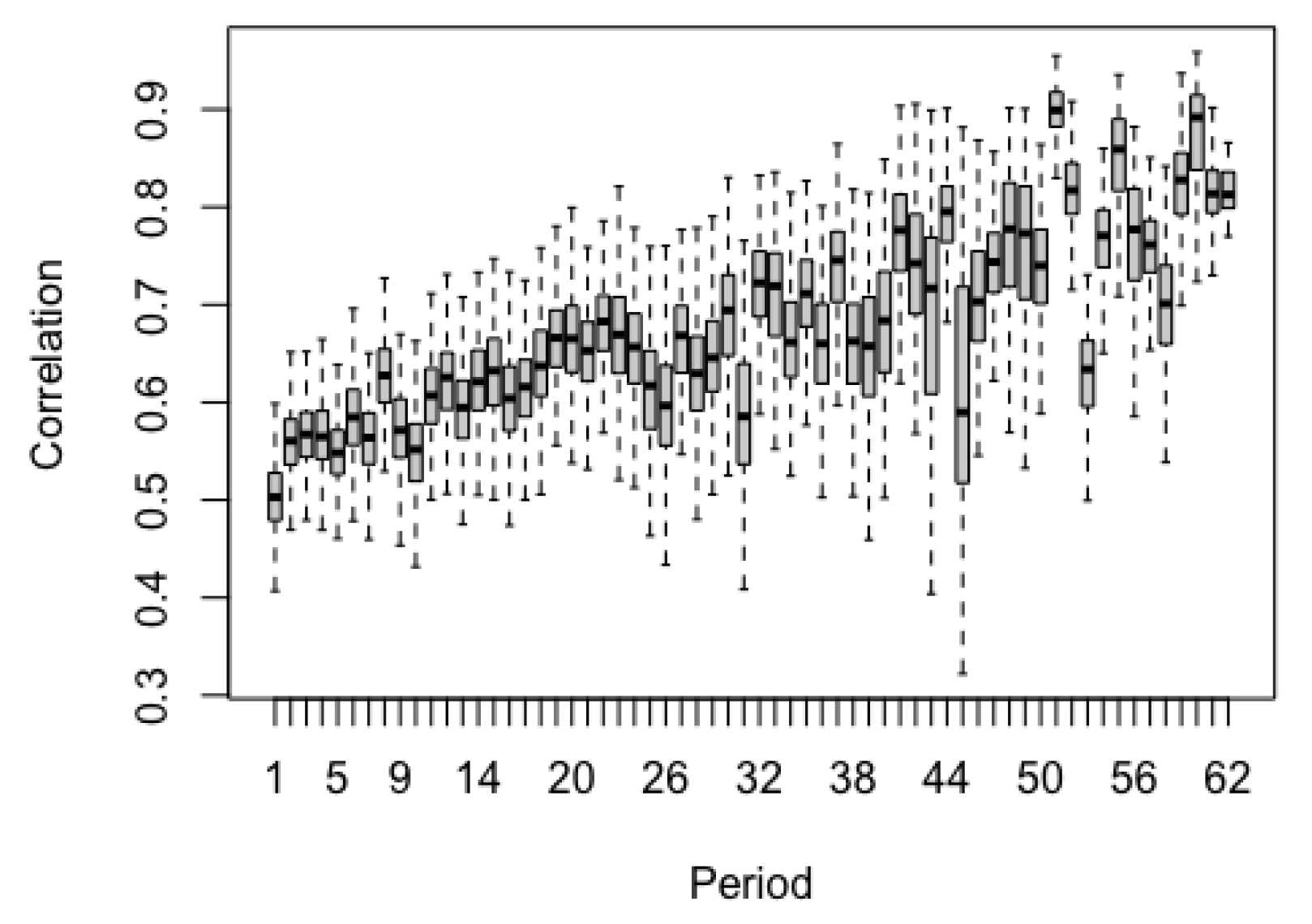

Figure 3 investigates the relationship between AQS stations and their corresponding nearby PA sites. Each point in

Figure 3 symbolizes one AQS station. For every AQS station, we pinpoint the closest PA station and calculate the sample correlation between the daily PM

measurement series for these two locations. We can see that the correlation is generally high for nearby stations and decreases with distance, suggesting that PA data will be a useful supplement to the spatial model.

2.2. Statistical model

We propose a multi-resolution Bayesian model for modeling AQS and PA measurements jointly in the spectral domain. Let and be AQS and PA measurements, respectively, for spatial location at time (day) , and be a corresponding vector of covariates with for the intercept. The covariates are temperature, relative humidity and indicators of low, medium and high density smoke plumes at site S and day t. We note that temperature and relative humidity are standardized to have mean zero and variance one and that the AQS and PA measurements are not taken at the same spatial locations.

The observations are decomposed as

for

, where

and

are spatiotemporal processes, and

is error. The time span of our data is relatively short, therefore, its reasonable to assume the spatiotemporal processes are stationary within the modeling period. We will apply Fourier transformation to the spatiotemporal processes

with respect to time to remove the temporal dependence. The resulting spectral processes

capture periodicity, are independent over frequency

and spatially correlated. For time series observed at equal time intervals, we can apply the discrete Fourier transformation (DFT). The spectral processes at frequency

is

and measures the variation in

at frequency

. Terms with small

(low frequency) represent long-term trends such as month-to-month averages and terms with large

(high frequency) represent short-term trends such as day-to-day variation. Let

be the unique real components of the DFT of

at frequencies

with

.

The spectral processes

are dependent across

, as they represent the two networks measuring the same underlying PM

process. They are also spatially dependent processes as locations nearby may exhibit similar periodicity. We model the cross network dependence and spatial dependence for each

as

where spatial process

is the true PM

concentration. The PA stations are assumed to be measuring a biased and noisy version of the true PM

with discrepancy

. The coefficient

controls the dependence across networks. Both the bias

and cross-dependence

vary by

to allow for a multi-resolution calibration of the two networks. We model

linearly as

, where

and

are unknown coefficients. This allows the correlation between the processes to vary stochastically with frequency. For example, if PA is more reliable for long-term trends than day-to-day variation, then we expect larger (smaller) correlation between networks for small (large)

.

The true process

and discrepancy term

are both regressed onto the covariates. Since we are developing a model in the spectral domain, we will also apply DFT to each covariate in

with respect to time and denote this as

Define the covariates for the true process

as

, containing all five covariates, and define

to include only temperature and relative humidity for bias correction [

15]. We model

and

as independent (with each other and over

l) Gaussian processes with means

and

, variances

and

, and spatial correlations

and

.

The regression coefficients

control the effects of the covariates on the true PM

process

U. Although we specify the model in the spectral domain, the DFT is a linear operator and thus the covariates can be interpreted as usual in the spatial domain since the mean AQS response is

Therefore,

is of primary interest. In particular, the components of

that correspond to the smoke plume indicators are used to summarize the wildland fire contribution to PM

.

The regression coefficients

control the effect of the covariates on the discrepancy term

V, and thus the contribution of the covariates to the PA bias. By allowing the covariance parameters

and

to vary by frequency (

l), we allow for a different degree of dependence between the networks at different temporal scales, with

The prior for the variance components is

where the hyperparameters are modelled as log-linear in frequency, e.g.,

the prior captures the intuition that the variance is higher in month-to-month variation than day-to-day variation, and the correlation between two sources vary over frequencies.

2.3. Quantifying the wildland fire contribution

To estimate the PM

contribution from wildfire, given the estimated parameters above, we consider two metrics based on either regression or matching. For the regression metric, let

be the covariate vector with three plume indicators fixed at zero. For the matching estimator, define

as the set of days for which site

s is in a smoke plume (any density) and

as the set of non-plume days. We match each plume day with a non-plume day with similar meteorology and time period. Let

be the set of non-plume days within 30 days of plume day

t. For each plume day, we selected the matching day

as

where

w above is a scaling factor adjusting the magnitude of humidity and temperature, we set

so that the best matching station has equal weights on temperature and humidity. Then at site

s the estimated contribution from wildland fires per day are

In the matching estimator,

is the true PM

, the transformed pairs of

in (

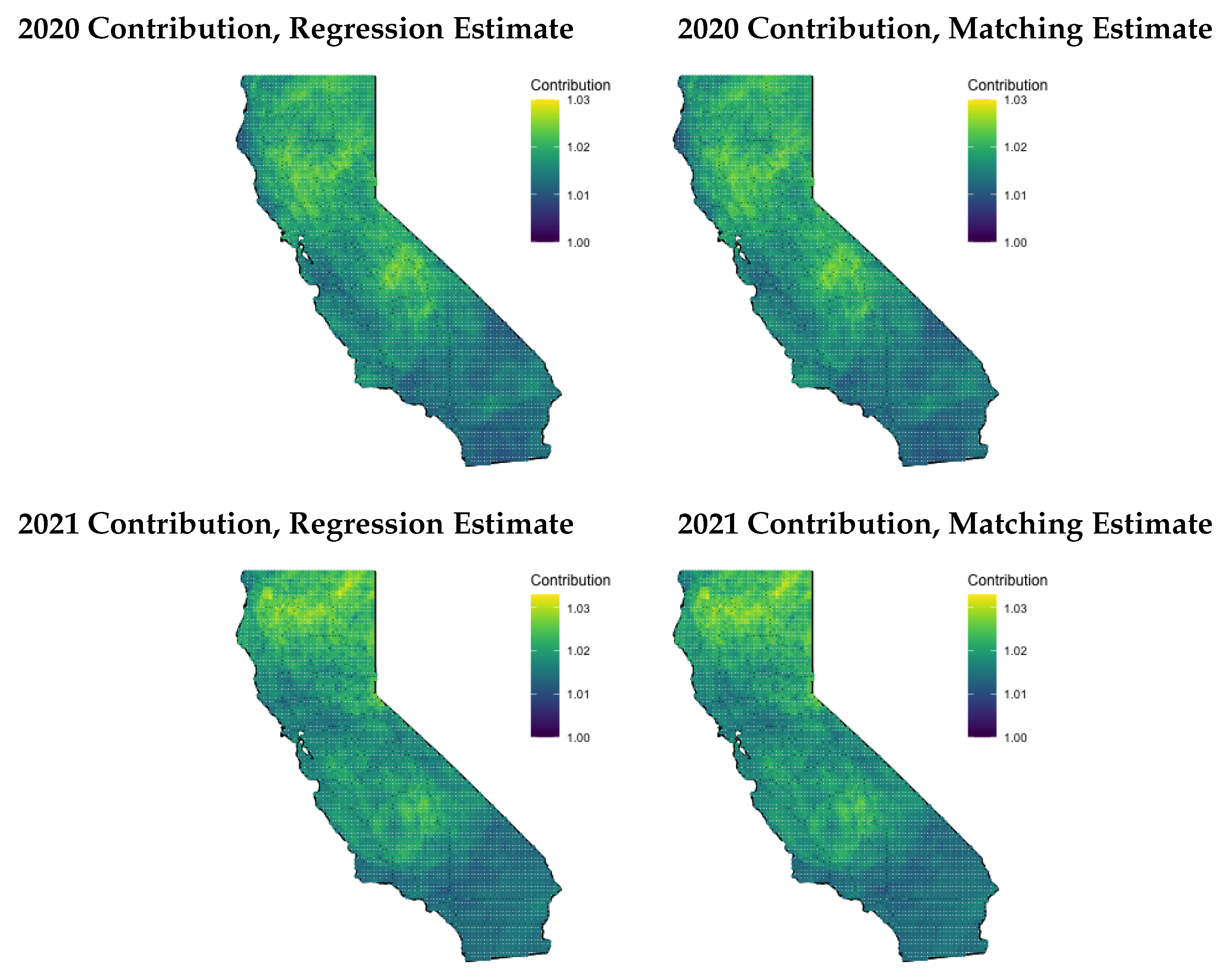

2) obtained by inverse DFT, and thus this estimator accounts for spatiotemporal bias and correlation. Since the analysis is on the log-scale, we plot

and

which estimate the multiplicative effect, i.e.,

corresponds to a 5% increase in PM

in the presence of a smoke plume.

2.4. Computational Algorithm

To complete the Bayesian model, we specify uninformative prior distributions for the model parameters. The regression coefficients have Gaussian priors . The variance parameters have conjugate priors . The hyperpameters have Gaussian priors . To give uninformative priors we set and . Due to poor convergence, the dependence parameters and were fixed based on cross-validation to minimize mean squared prediction error for AQS stations.

The main computational bottleneck of spatial modeling is manipulating spatial covariance matrices to estimate the range parameters and . Given the large size of the air pollution dataset, a reasonable simplification is to estimate the range parameters using variogram and then assume they are fixed for the purpose of fitting the final model. The estimated spatial range from variograms are and kilometers.

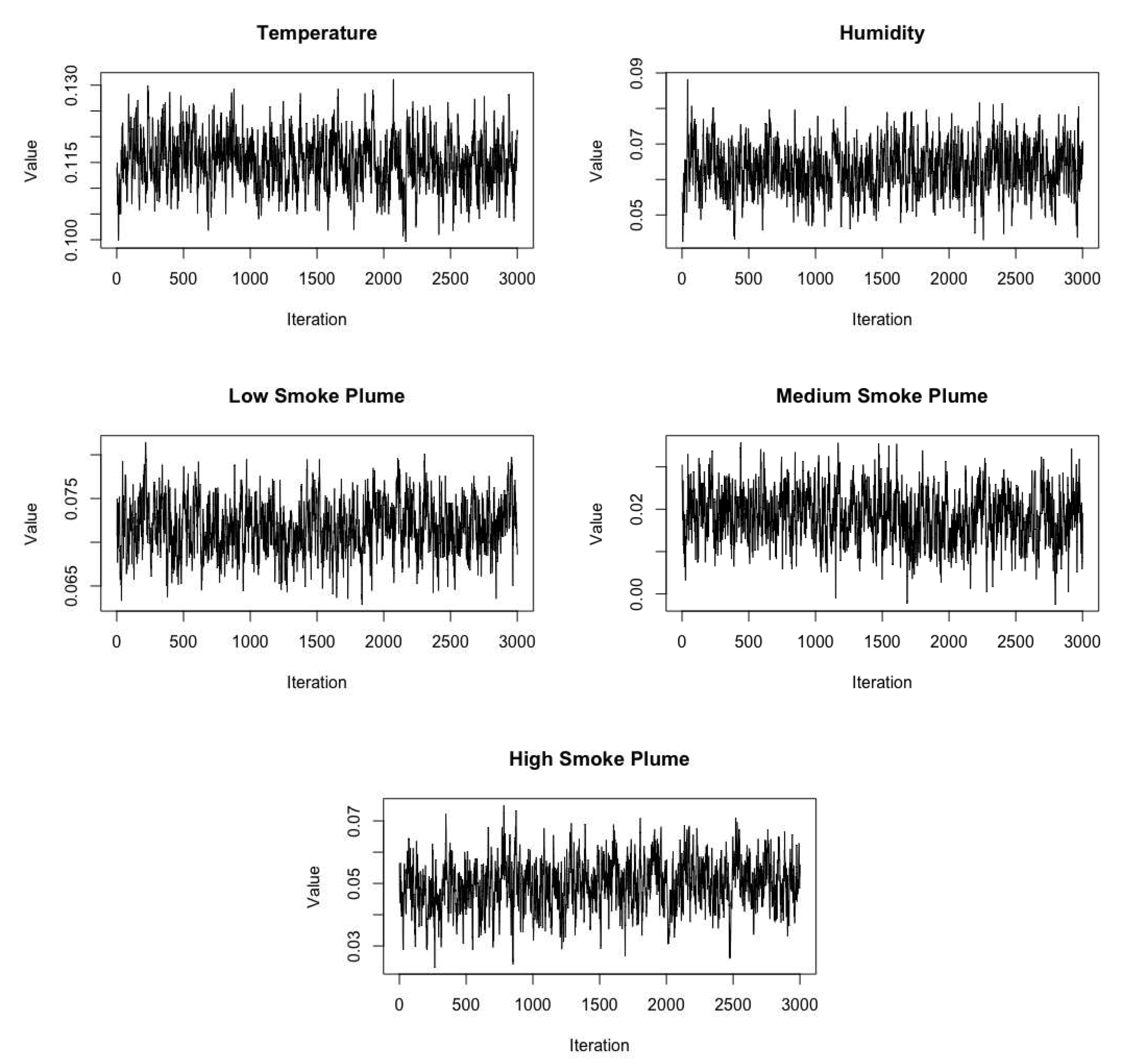

Given the range parameters are fixed, the remaining parameters are estimated using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods. In particular, we perform Gibbs sampling steps for most parameters and Metropolis sampling for some hyperparameters. Missing values are addressed using Bayesian multiple imputation (refer to Appendix A for more information). We generate 8,000 posterior samples and discard the first 5,000 as burn-in. Convergence is monitored using trace plots. A simulation study is included in the Appendix to verify the algorithm produces reliable parameter estimates. Convergence plots for several representative parameters are shown in

Figure A1 in the Appendix for the real data analysis.

4. Discussion

In this study, we examine the impact of wildland fires on PM concentrations in California during the fire seasons of 2020 and 2021. To do this efficiently, we combine remotely-sensed smoke-plume indicators with AQS and PA measurement networks. To model the spatiotemporal correlation of PM concentration and relationship between AQS and PA monitors, we first transform the data from spatial domain to frequency domain, and then use a data-fusion approach to model spatial correlations while accounting for biases in the PA data. Furthermore, we use a Bayesian approach to compute posterior distributions of the quantities of interest to fully characterize uncertainty.

We find that including PurpleAir monitors significantly increases the precision of the estimated contribution of wildland fire smoke to total PM. Using only AQS data we find that medium and high smoke plume levels significantly contribute to PM concentration with standard deviations as large as 0.017, and the data fusion approach that supplements AQS with PA data gives similar parameter estimation, with standard deviation as small as 0.004. Moreover, the data fusion model also estimates a significant low smoke plume level contribution. However, since PM concentration is relatively smooth across space and AQS stations are evenly distributed across the state, incorporating PurpleAir readings does not improve prediction performance even for the data-fusion approach. Comparing prediction performance does reveal that simple data fusion model such as the model that ignores bias in the PA data gives inferior prediction results. With our model, all three smoke plume levels demonstrate a significant contribution to PM concentration, and the impact varies across different regions depending on the year. This study highlights the value of utilizing both AQS and PurpleAir data in understanding the impact of wildfires on air quality and informs future monitoring and management efforts.

There are some limitations of our current work. First, as mentioned above, the satellite-derived smoke plume levels might underestimate the actual smoke level, which may lead to underestimation of wildfires’ contribution to PM

[

30]. Second, due to computational limitations and poor MCMC convergence, we fixed the spatial correlation range parameters for both AQS and PA monitors and parameters that control the relationships between AQS and PA data. The analysis would more fully quantify uncertainty if we are able to implement a fully Bayesian analysis.

We have taken a purely statistical approach to estimating the contribution of wildland fires on ambient air pollution. An area of future work is to incorporate numerical models to simulate the process. Dispersion models, e.g., HySPLIT [

32], combine the location and size of fires and meteorological conditions in a mathematical model to track particulate matter emanating from a fire. Of course, numerical models also have bias and other limitations [

33], but combining their output within our statistical framework would likely further refine our estimates. Further, instead of using one range parameter for all frequencies, it is possible to get variogram estimates of ranges over frequencies. Also, to extend the current work, we can estimate the contribution over the entire U.S. continent, and investigate how different areas suffer from wildfires, although more computational efficient models are required to analyze all US data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AR and BR; methodology, HY, YG, BR; validation, HY, SRS; formal analysis, HY; data curation, HY, SRS.; writing-original draft preparation, HY; writing—review and editing, SRS, BR, YG, AR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Appendix A. Data Cleaning

Before the data was subjected to a statistical model, we implemented several pre-processing steps on the PurpleAir data and standardized certain covariates to meet the assumption of normality. PurpleAir stations feature two independent channels, Channel A and Channel B, both of which measure ambient PM independently. To achieve a more accurate estimation of the actual ambient PM concentration, we discarded readings where the measurement difference exceeded 200 and constant high PM readings over 2000 . Subsequently, the mean reading from Channel A and Channel B was considered as the PurpleAir measurement.

Most PurpleAir stations measure temperature (in Fahrenheit) and humidity (as a percentage). Given the spatially smooth changes in temperature and humidity, we employed a 10-nearest-neighbor approach to impute stations with missing temperature and humidity values. Both temperature and humidity were standardized before fitting the model as specified in the analysis.

Appendix B. MCMC algorithm

Assume the

AQS monitors are at spatial locations

and the

PA monitors are located at

for

. The observations can be written as the vectors

,

and

. Similarly, for frequency

l let

,

and

be vectors of length

and

,

and

be vectors of length

, analogous to

. The covariate matrices of size

are denoted

and

is the

matrix that stacks

and

. Then the model in the spectral domain is

where

. Using this notation, the spatial models are defined by

,

,

and

. The full

spatial correlation matrices are denoted

and

.

Each MCMC iteration we impute missing data and update the error variance parameters in the spatial domain, and then update all remaining parameters in the spectral domain. The missing values are simply drawn from the univariate normal distribution

independently over

j and

t. The error variances are drawn from full conditional distribution

and

.

After imputation in the spatial domain, the data are complete and can be projected into the spectral domain where they are independent over time. The spatial processes are updated as

where

is diagonal with first

elements equal one and the remaining

elements equal

,

T is diagonal with first

elements equal

and the remaining

elements equal

,

is the vector with

zeros followed by

,

and

.

The regression coefficients and bias parameters are updated as

where

and

. The remaining hyperparameters are updated as

Finally,

,

,

and

are updated using a Metropolis step with Gaussian candidate distribution tuned to give acceptance rate around 0.4.

Appendix C. Simulation Results

We conduct a simulation study to demonstrate the reliability of the MCMC algorithm. The regression parameters,

and

, are fixed at the mean of the 2021 model output in

Table 1. We generate a total number of 80 AQS stations and 500 Purple Air stations with 60 time steps. The spatial locations are randomly sampled from the region

. The data was generated in the frequency domain using the following equations:

The variables

and

are drawn from Gaussian processes as described in (

2). The range parameters are set to

and

. The error variances of

and

are set to 1.6 and 3.6, respectively. The values of

are fixed at the best

selected from the real data which is

.

To simulate realistic smoke plume frequencies, we assigned percentages to represent the occurrence of low, medium, and high smoke plume levels. Specifically, 20% of the days corresponded to low smoke plume levels, 15% to medium levels, and 10% to high levels. Temperature and humidity values were randomly generated from standard normal distributions.

The covariates were initially generated in the time domain and then transformed to the frequency domain. The values of

form a decreasing sequence ranging from 50 to 10, with larger values assigned to lower frequencies. Similarly,

follows a decreasing sequence from 40 to 10. Finally, the values of

and

are the mean values from

Table 1.

We generate 50 datasets from this model. For each simulated dataset, we fit the model with

,

and

fixed at the true values and generate 8000 MCMC iterations and discard the first 5000 as burn-in. Since our main interest is in the covariate effects, for each dataset we record the effective sample size of the MCMC algorithm [

34] and the posterior mean estimator and 95% posterior interval.

For each dataset and each parameter, we compute the posterior mean, standard deviation and 95% interval and measure MCMC convergence using the effective sample size. The average of the posterior means, standard deviations and effective samples sizes, and the empirical coverage of 95% intervals are shown in

Table A1. The posterior means show small bias, the coverage is near the nominal level and the effective sample size coefficients indicate reasonable convergence.

Table A1.

True value used for the fixed effects for the true PM () and bias () to simulate data and the average (SD) over the 50 datasets of the posterior mean estimators (“Ave post mean”), coverage of 95% posterior intervals and average (SD) effective sample size based on 3000 MCMC iterations.

Table A1.

True value used for the fixed effects for the true PM () and bias () to simulate data and the average (SD) over the 50 datasets of the posterior mean estimators (“Ave post mean”), coverage of 95% posterior intervals and average (SD) effective sample size based on 3000 MCMC iterations.

| Type |

Covariate |

True value |

Average post mean |

Coverage |

ESS |

| PM

|

Temperature |

0.118 |

0.117 (0.013) |

100% |

420.23 (0.14) |

| |

Humidity |

0.064 |

0.069 (0.022) |

96% |

307.27 (0.10) |

| |

Plume - Low |

0.007 |

0.006 (0.132) |

100% |

875.99 (0.29) |

| |

Plume - Medium |

0.022 |

0.020 (0.037) |

98% |

376.91 (0.13) |

| |

Plume - High |

0.049 |

0.050 (0.176) |

100% |

480.22 (0.16) |

| Bias |

Temperature |

-0.002 |

0.003 (0.019) |

92% |

168.75 (0.06) |

| |

Humidity |

0.012 |

0.009 (0.041) |

96% |

176.97 (0.06) |

Appendix D. Cross-Validation Results

We compare methods using a 5-fold cross-validation using data from 2021. We randomly split the AQS stations into five folds. For each fold, we build predictive models based on the other AQS stations and all PA stations and make predictions at the test sites. We compare the proposed data-fusion model (“Data fusion”) with the AQS only and Naive models described in the main text. For all models, we fix the spatial range parameters ( and ) based on the variogram analysis of the full dataset. The cross-dependence parameter is fixed at 0.2.

The results in

Table A2 show that the performance of the AQS-only analysis is fairly similar to the proposed data-fusion approach, with slightly smaller prediction mean squared error and larger average prediction variance. Therefore, carefully including the additional PA data mainly reduces the prediction variance. However, naively including the PA data gives much higher prediction errors and low coverage.

Table A2.

Root mean squared error (“RMSE”), coverage of 95% prediction intervals (“Coverage”) and average prediction variance (“Ave Var”) for the cross-validation study comparing the proposed data fusion model to models that ignore PA data (“AQS only”) and includes PA data without bias correction (“Naive”).

Table A2.

Root mean squared error (“RMSE”), coverage of 95% prediction intervals (“Coverage”) and average prediction variance (“Ave Var”) for the cross-validation study comparing the proposed data fusion model to models that ignore PA data (“AQS only”) and includes PA data without bias correction (“Naive”).

| Model |

RMSE |

Coverage |

Ave Var |

| Data Fusion |

0.42 |

0.89 |

0.13 |

| AQS only |

0.40 |

0.91 |

0.16 |

| Naive |

0.66 |

0.73 |

0.18 |

Appendix E. Real Data Convergence

We display several representative trace plots of the data fusion model to verify the convergence of our MCMC algorithm for the 2021 CA analysis. After burn-in, the MCMC chains appear to have converged.

Figure A1.

Trace plots of parameters of interest () for the 2021 California data analysis.

Figure A1.

Trace plots of parameters of interest () for the 2021 California data analysis.