Submitted:

07 July 2023

Posted:

10 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

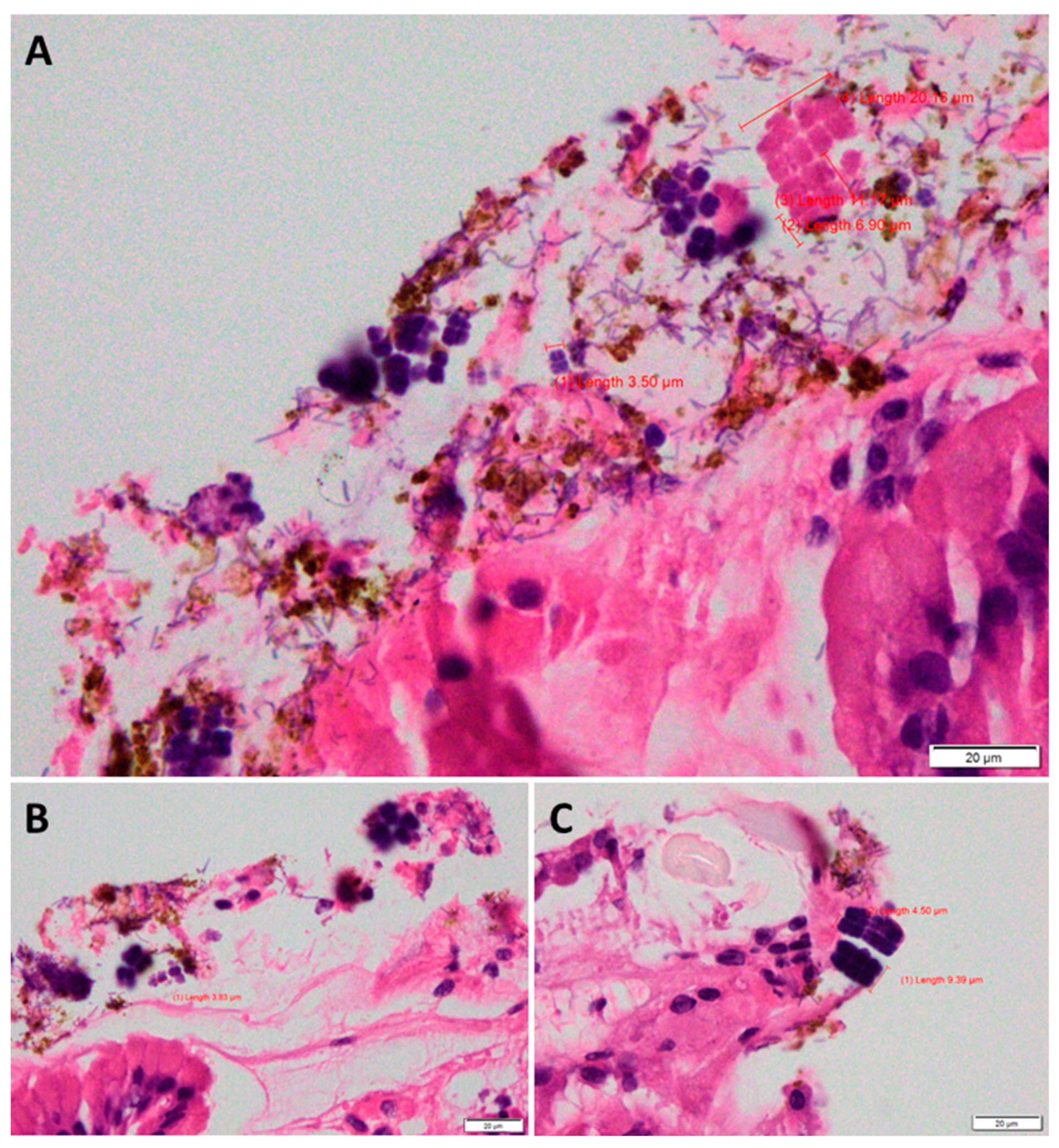

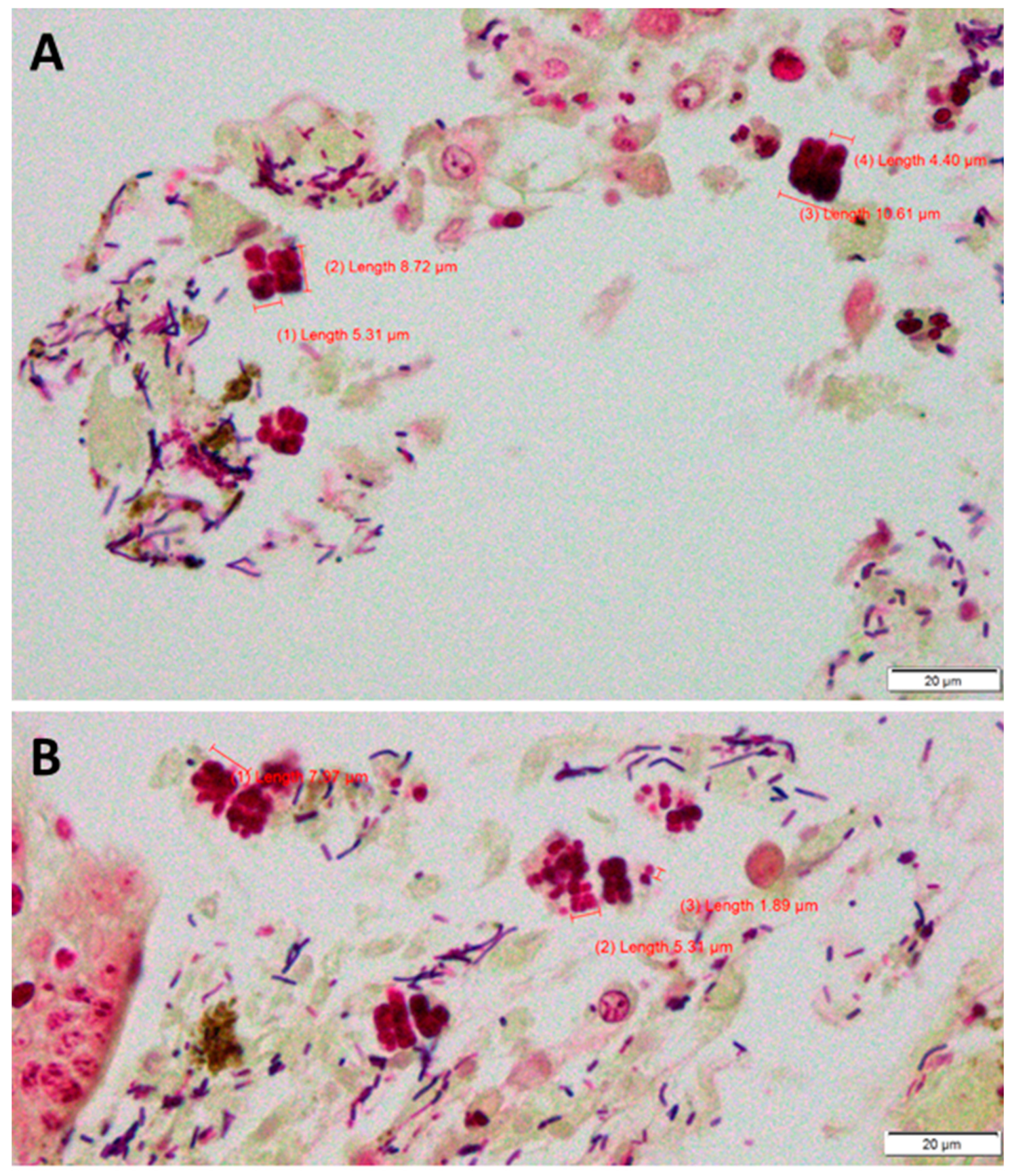

Case Description

Case Analysis

Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elvert, J.L.; El Atrouni, W.; Schuetz, A.N. Photo Quiz: A Bacterium Better Known by Surgical Pathologists than by Clinical Microbiologists. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e01335–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elvert, J.L.; El Atrouni, W.; Schuetz, A.N. Answer to Photo Quiz: Sarcina ventriculi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e01335–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodsir, J.; Wilson, G. History of a Case in Which a Fluid Periodically Ejected from the Stomach Contained Vegetable Organisms of an Undescribed Form. Edinb. Med Surg. J. 1842, 57, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam-Himlin D, Tsiatis AC, Montgomery E; et al. Sarcina organisms in the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011, 35, 1700–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcelino, L.P.; Valentini, D.F.; Machado, S.M.d.S.; Schaefer, P.G.; Rivero, R.C.; Osvaldt, A.B. Sarcina ventriculi a rare pathogen. Autops. Case Rep. 2021, 11, e2021337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tartaglia, D.; Coccolini, F.; Mazzoni, A.; Strambi, S.; Cicuttin, E.; Cremonini, C.; Taddei, G.; Puglisi, A.G.; Ugolini, C.; Di Stefano, I.; et al. Sarcina Ventriculi infection: a rare but fearsome event. A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 115, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debey, B.M.; Blanchard, P.C.; Durfee, P.T. Abomasal bloat associated with Sarcina-like bacteria in goat kids. J. Am. Veter- Med Assoc. 1996, 209, 1468–1469. [Google Scholar]

- Vatn, S.; Gunnes, G.; Nybø, K.; Juul, H.M. Possible Involvement of Sarcina ventriculi in Canine and Equine Acute Gastric Dilatation. Acta Veter- Scand. 2000, 41, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, L.A.; Colitti, B.; Hirji, I.; Pizarro, A.; Jaffe, J.E.; Moittié, S.; Bishop-Lilly, K.A.; Estrella, L.A.; Voegtly, L.J.; Kuhn, J.H.; et al. A Sarcina bacterium linked to lethal disease in sanctuary chimpanzees in Sierra Leone. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 07 June. Available online: https://bacdive.dsmz.de/strain/164000#ref69479(retrieved on 07 June 2023).

- Al Rasheed, M.R.H.; Senseng, C.G. Sarcina ventriculi: Review of the Literature. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2016, 140, 1441–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Lowe, S.; Pankratz, H.S.; Zeikus, J.G. Influence of pH extremes on sporulation and ultrastructure of Sarcina ventriculi. J. Bacteriol. 1989, 171, 3775–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, J. Die Gärungssarcinen. Eine Monographie. Pflanzenforschung 1930, 14, 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Willems, A.; Collins, M.D. Phylogenetic Placement of Sarcina ventriculi and Sarcina maxima within Group I Clostridium, a Possible Problem for Future Revision of the Genus Clostridium: Request for an Opinion. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1994, 44, 591–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, P.A.; Rainey, F.A. Proposal to restrict the genus Clostridium Prazmowski to Clostridium butyricum and related species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tindall, B.J. Priority of the genus name Clostridium Prazmowski 1880 (Approved Lists 1980) vs Sarcina Goodsir 1842 (Approved Lists 1980) and the creation of the illegitimate combinations Clostridium maximum (Lindner 1888) Lawson and Rainey 2016 and Clostridium ventriculi (Goodsir 1842) Lawson and Rainey 2016 that may not be used. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 4890–4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegel J, Family I. 2009. Clostridiaceae Pribram 1933, 90 AL. In: De Vos P, Garrity GM, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Rainey FA, K.-H. S, Whitman WB (eds), Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, volume 3, The Firmicutes, Springer, New York, p. 738-848.

- 07 June. Available online: https://lpsn.dsmz.de/species/sarcina-ventriculi(retrieved on 07 June 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).