1. Introduction

COVID-19 is the disease caused by the novel coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2. The World Health Organization (WHO) first became aware of its existence on December 31, 2019, when informed of a group of cases of "viral pneumonia" reported in Wuhan, People’s Republic of China [

1]. On March 11, 2020, as the virus progressively spread worldwide, the WHO declared it a pandemic [

2], which on May 05, 2023, was declared over. Until June 14, 2023, a total of 767,984,989 cases and 6,943,390 deaths had been reported worldwide [

3], with Spain ranking 13th in the world in reported cases (13,890,555) and 15th in the number of deaths (121,416) [

3]. Out of the total cases in our country, the Community of Madrid accounted for 14.4% according to the latest report from the Spanish Ministry of Health [

4].

However, the incidence during this period has not been uniform, with up to seven epidemic waves declared by the Spanish Ministry of Health based on variations in the 14-day cumulative incidence [

5]. Several factors have influenced the emergence of these waves. For example, on March 14, 2020, a state of alarm and strict lockdown measures were decreed nationwide, which were not lifted until June 21, 2020. Since then, isolation measures have varied depending on each Autonomous Community, with no new mobility restrictions reimposed in the Community of Madrid. On the other hand, the level of immunity to the virus, whether natural or through vaccination, has varied throughout this period. In Spain, the vaccination program began on December 27, 2020 [

6], during the peak of the third wave. According to official data from the Spanish Ministry of Health as of January 5, 2023, 95.5% of the population in the Community of Madrid had completed vaccination [

8]. Finally, three variants of concern (VOC), according to the WHO’s definition [

7], have been dominant in our country since the beginning of the pandemic. In early 2021, B.1.1.7 (alpha, UK variant) displaced the original strain until approximately week 21 of that year, when it was quickly replaced by B.1.617.2 (delta, Indian variant), which remained the most common one until the final weeks of the same year, when it was replaced by B.1.1.529 (omicron), whose various lineags are still predominant [

8].

Our hypothesis is that each wave exhibited a series of peculiarities, some measurable and others not, that could explain clinical and outcome differences between them, thus justifying the separate analysis of the waves. These peculiarities included the total number of available beds in the hospital and in the intensive care unit (ICU), circulating variants, vaccination status, use of masks and other isolation measures, seasonality, evidence regarding different treatments, and availability of diagnostic tests. This aspect was already observed in the first two waves [

9,

10] and has been corroborated in other countries that have evaluated multiple waves [

11] with a different dynamic than our own environment. Our main objective was to determine the overall mortality and severity of COVID-19 in each wave, and identify factors associated with both parameters of COVID-19 during the period.

3. Results

3.1. Duration of the epidemic waves

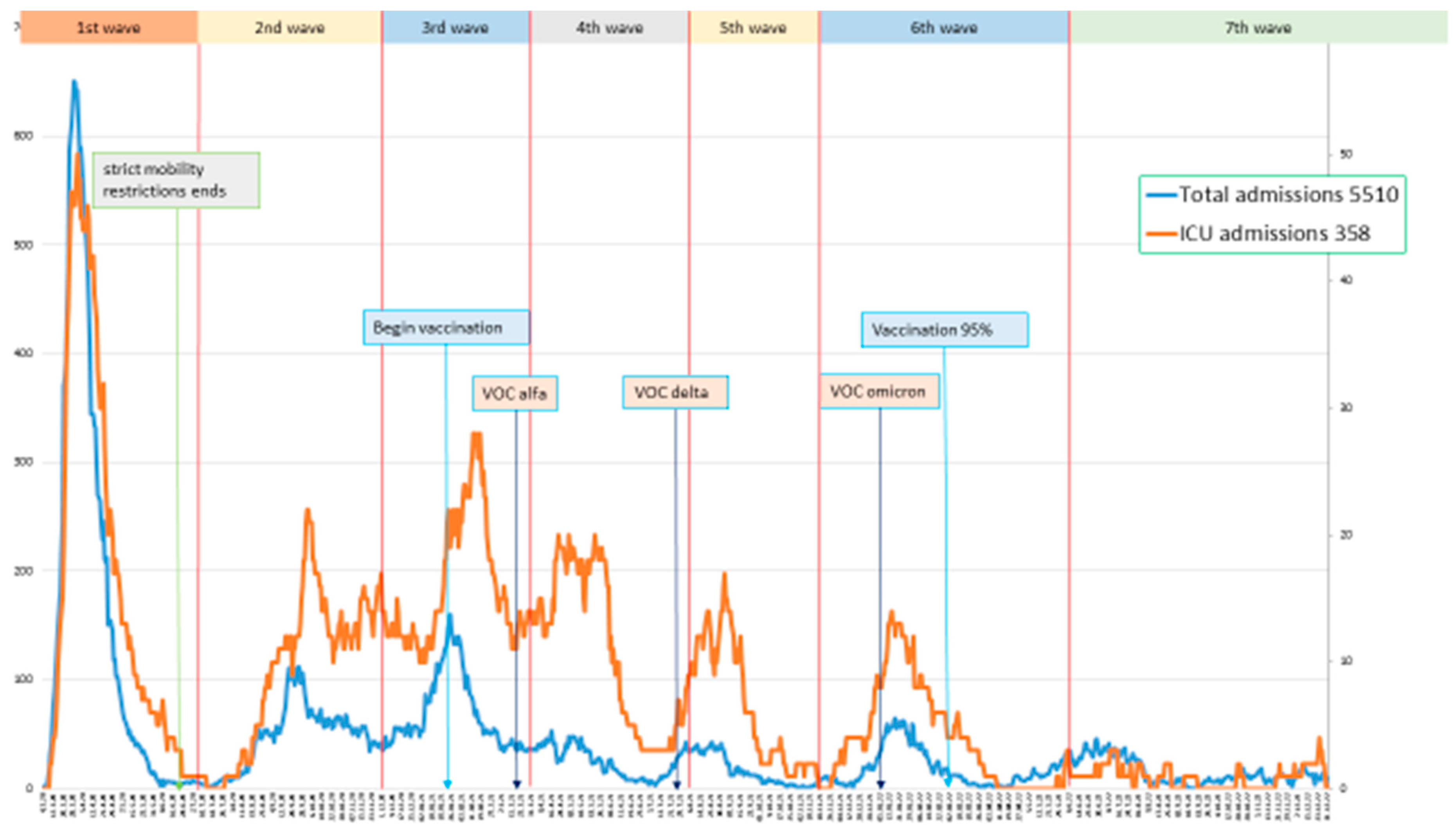

Based on the increase in the number of weekly admissions, the following dates were defined for each epidemic wave (

Figure 1).

First wave: March 4, 2020, to July 2, 2020, with a peak on March 31, 2020. Second wave: July 15, 2020, to November 25, 2020, with a peak on September 25, 2020. Third wave: November 26, 2020, to February 28, 2021, with a peak on January 25, 2021. Fourth wave: March 1, 2021, to June 30, 2021, with a peak on April 16, 2021. Fifth wave: July 1, 2021, to September 30, 2021, with a peak on August 23, 2021. Sixth wave: October 1, 2021, to April 4, 2022, with a peak on January 17, 2022. Seventh wave: April 5, 2022, to December 31, 2022, with a peak on June 28, 2022. t waves.

3.2. Description:

There were a total of 5,510 COVID admissions, corresponding to 5,001 patients with 509 readmissions (9%), regardless of the reason for readmission (

Table 1). Nearly 50% of the total admissions occurred in the first two waves, while hospitalizations decreased in subsequent waves.

3.2.1. Descriptive analysis of patient characteristics by waves (excluding re-admissions) (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5)

Mean age was significantly higher in the last two waves (

Table 2). Highest proportion of immigrant patients occurred in the second and fifth waves. Mean age of non-immigrants was higher: 66.6 years, compared to 50.4 for Latin Americans, and 52.3 for North Africans.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics by epidemic wave.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics by epidemic wave.

| Wave |

First |

Second |

Third |

Fourth |

Fifth |

Sixth |

Seventh |

Total |

p |

| Patients1

|

1735 (35%) |

900 (18%) |

823 (17%) |

414 (8%) |

291 (6%) |

441 (8%) |

397 (8%) |

5001 |

|

| Male sex1

|

957 (55%) |

464 (52%) |

472 (57%) |

232 (56%) |

163 (52%) |

228 (52%) |

200 (50%) |

2743 (54%) |

0.073 |

| Age2

|

63.3 (0.36) |

60.3 (0.57) |

64.5 (0.57) |

60.2 (0.74) |

55.3 (1.2) |

67.1 (0.82) |

76.5 (0.74) |

63.6 (0.24) |

<0.001 |

| Place of birth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Spain1

|

1435 (84%) |

600 (68%) |

700 (87%) |

330 (80%) |

188 (66%) |

368 (85%) |

382 (96%) |

4003 (81%) |

| Latin America1

|

168 (10%) |

156 (17%) |

63 (8%) |

49 (12%) |

30 (11%) |

24 (6%) |

6 (2%) |

495 (10%) |

| North Africa1 |

26 (2%) |

66 (7%) |

16 (2%) |

14 (3%) |

25 (8%) |

12 (3%) |

3 (1%) |

162 (3%) |

Table 3.

Clinical indicators by waves.

Table 3.

Clinical indicators by waves.

| Wave |

First |

Second |

Third |

Fourth |

Fifth |

Sixth |

Seventh |

Total |

p |

| Patients |

1735 (35%) |

900 (18%) |

823 (17%) |

414 (8%) |

291 (6%) |

441 (8%) |

397 (8%) |

5001 |

|

| Length of total stay1

|

10.8 (0.28) |

10.7 (0.46) |

11.5 (0.50) |

12.0 (0.79) |

10.6 (0.70) |

9.8 (0.61) |

7.4 (0.66) |

10.7 (0.19) |

<0.001 |

| Length of ICU stay1

|

19.4 (1.99) |

21.6 (2.23) |

22.6 (2.52) |

24.2 (3.12) |

16.8 (2.54) |

19.4 (3.16) |

18.1 (4.91) |

20.8 (1.02) |

0.611 |

| Delay until ICU admission1

|

4.70 (0.61) |

2.79 (0.38) |

3.91 (0.53) |

2.72 (0.44) |

2.20 (0.54) |

2.92 (0.72) |

1.02 (0.61) |

3.40 (0.23) |

0.009 |

Table 4.

Comorbidities by waves.

Table 4.

Comorbidities by waves.

| Wave |

First |

Second |

Third |

Fourth |

Fifth |

Sixth |

Seventh |

Total |

p |

| Patients |

1735 (35%) |

900 (18%) |

823 (17%) |

414 (8%) |

291 (6%) |

441 (8%) |

397 (8%) |

5001 |

|

| Charlson index1

|

1.23 (0.05) |

1.21 (0.07) |

1.35 (0.08) |

1.12 (0.10) |

1.24 (0.13) |

2.02 (0.13) |

2.31 (0.16) |

1.36 (0.03) |

<0.001 |

| Hypertension2

|

816 (47%) |

371 (41%) |

425 (52%) |

185 (45%) |

114 (39%) |

253 (57%) |

150 (68%) |

2314 (48%) |

<0.001 |

| Diabetes2

|

221 (13%) |

96 (11%) |

113 (14%) |

33 (8%) |

26 (9%) |

58 (13%) |

48 (22%) |

595 (12%) |

<0.001 |

| Cardiopathy2

|

77 (4%) |

42 (5%) |

42 (5%) |

13 (3%) |

19 (7%) |

21 (5%) |

24 (11%) |

238 (5%) |

0.002 |

| COPD2,3

|

171 (10%) |

72 (8%) |

75 (9%) |

32 (8%) |

23 (7%) |

62 (14%) |

88 (35%) |

523 (11%) |

<0.001 |

| Asthma2

|

158 (9%) |

66 (7%) |

78 (10%) |

31 (8%) |

24 (8%) |

44 (10%) |

30 (13%) |

431 (9%) |

0.148 |

| Cancer2

|

323 (19%) |

155 (17%) |

149 (18%) |

57 (14%) |

40 (14%) |

119 (27%) |

109 (45%) |

952 (20%) |

<0.001 |

| Dementia2

|

51 (3%) |

30 (3%) |

27 (3%) |

12 (3%) |

10 (3%) |

34 (8%) |

52 (21%) |

216 (5%) |

<0.001 |

| PLHIV4

|

5 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

14 (0.3%) |

0.228 |

Table 5.

Clinical variables by waves.

Table 5.

Clinical variables by waves.

| Wave |

First |

Second |

Third |

Fourth |

Fifth |

Sixth |

Seventh |

Total |

p |

| Patients |

1735 (35%) |

900 (18%) |

823 (17%) |

414 (8%) |

291 (6%) |

441 (8%) |

397 (8%) |

5001 |

|

| Oxygen saturation on admission1

|

92.7 (0.15) |

93.9 (0.14) |

92.8 (0.21) |

93.2 (0.21) |

93.3 (0.36) |

93.3 (0.31) |

93.7 (0.23) |

93.1 (0.08) |

<0.001 |

| Worst oxygen saturation1

|

88.2 (0.19) |

89.7 (0.21) |

88.5 (0.28) |

89.9 (0.26) |

90.3 (0.37) |

89.8 (0.33) |

90.7 (0.37) |

89.1 (0.11) |

<0.001 |

| O2 requirements: None2

|

415 (24%) |

266 (30%) |

165 (20%) |

86 (21%) |

50 (18%) |

114 (26%) |

56 (30%) |

1152 (25%) |

<0.001 |

| Low O2 flow2

|

869 (51%) |

434 (50%) |

430 (53%) |

214 (53%) |

156 (55%) |

234 (53%) |

118 (64%) |

2455 (52%) |

| High O2 flow2

|

321 (19%) |

107 (12%) |

151 (19%) |

53 (13%) |

42 (15%) |

64 (15%) |

6 (3%) |

744 (16%) |

| Mechanical ventilation2

|

93 (6%) |

67 (8%) |

64 (8%) |

48 (12%) |

34 (12%) |

28 (6%) |

5 (3%) |

339 (7%) |

| CRP1,3

|

12.7 (0.24) |

10.5 (0.31) |

10.8 (0.30) |

11.1 (0.43) |

10.6 (0.53) |

9.6 (0.41) |

7.7 (0.57) |

11.2 (0.13) |

<0.001 |

| IL-61,4

|

378 (55) |

258 (31) |

248 (22) |

270 (39) |

313 (52) |

185 (30) |

32 (8) |

268 (15) |

0.005 |

| DD1,5

|

3764 (265) |

2524 (199) |

3471 (385) |

3370 (559) |

2637 (372) |

3132 (327) |

2097 (719) |

3276 (141) |

<0.001 |

| Ferritin1,6

|

964 (74) |

920 (55) |

913 (41) |

961 (51) |

886 (81) |

752 (46) |

375 (55) |

887 (23) |

0.039 |

| Remdesivir2

|

0 |

15 (2%) |

9 (1%) |

2 |

0 |

1 |

9 (5%) |

36 (1%) |

<0.001 |

| Corticosteroids2

|

715 (41%) |

609 (68%) |

679 (83%) |

324 (78%) |

236 (81%) |

337 (76%) |

123 (69%) |

3023 (63%) |

<0.001 |

| Tocilizumab2

|

257 (15%) |

261 (29%) |

347 (42%) |

163 (39%) |

102 (35%) |

100 (23%) |

9 (5%) |

1239 (26%) |

<0.001 |

| Baricitinib2

|

17 (1%) |

5 (15%) |

6 (1%) |

10 (2%) |

46 (16%) |

57 (13%) |

3 (2%) |

144 (3%) |

<0.001 |

| pLMWH2,7

|

1450 (84%) |

801 (89%) |

750 (91%) |

398 (87%) |

284 (89%) |

365 (83%) |

121 (68%) |

4103 (86%) |

<0.001 |

| Vaccinated2

|

0 |

0 |

1 (0.1%) |

20 (5%) |

112 (39%) |

328 (74%) |

159 (88%) |

620 (13%) |

<0.001 |

Regarding some clinical indicators (

Table 3), overall mean length of stay for patients was 10.7 days, being higher in the third and fourth waves and lower in the last two waves. Mean length of stay in the ICU showed no differences between waves. Patients took more days to be admitted to the ICU in the first wave (4.7 days).

The burden of comorbidity was higher in the sixth and seventh waves (

Table 4). Only 14 people living with HIV (PLHIV) required admission, and only 2 needed mechanical ventilation; 1 of them deceased, who was diagnosed during the hospitalization with less than 50 CD4 count.

Patients in the first and third waves had worst mean oxygen saturations at admission and during the entire length of their hospital stay (

Table 5). This was associated with a higher need of high-flow oxygen in these two waves, but not mechanical ventilation. Inflammatory parameters were higher in the first wave (

Table 5), but corticosteroids and tocilizumab were less used in this wave; both drugs were administered to a higher proportion of patients during the third. The use of remdesivir was very low until the seventh wave (

Table 5). Regarding patients with a maximum CRP greater than 7.5 mg/dl, 73% received steroids and 36% received tocilizumab. Regarding patients with IL-6 levels greater than 40 pg/ml before treatment, 95% received steroids and 100% received tocilizumab.

3.3. Rates of mortality and mechanical ventilation

Out of the 5,510 admissions, 358 required mechanical ventilation (6.5% of the total admissions), and 514 patients (10.3%) died within 3 months of admission (

Table 6). The lowest proportions of intubated patients were observed in the first (only 5%, presumably due to a lack of ICU beds) and seventh waves (only 1%, probably due to the lower severity of the disease). The fourth and fifth waves were the only ones in which the proportion of intubated patients was higher than the proportion of deaths. The highest mortality occurred in the first wave and in the two winter waves (third and sixth), although the first one accounted for 39% of the total of deaths.

3.4. Factors associated with COVID-19 mortality

A total of 5,001 patients were analyzed, although the final model included 4,532 patients (469 lost to follow-up).

Table 7 shows the results of the multivariate analysis excluding the maximum IL-6 value. When including it, the model consisted of 2,328 patients (IL-6 was not assessed in 2,673 subject), and the same variables were maintained except for the exclusion of CRP and the inclusion of IL-6, both as continuous variables (HR 1.001, CI 95% 1.000-1.001, per 1.0 pg/ml).

The following variables were not included in the final model due to lack of statistical significance in the univariate analysis (p>0.1): COVID-19 wave, birthplace, hypertension, diabetes, cardiopathy, COPD, asthma, chest X-ray at admission, oxygen saturation below 94% during hospitalization, D-dimer values, remdesivir, tocilizumab, corticosteroids, baricitinib, and full vaccination.

Mean age of deceased patients was higher, 77.3 years compared to 61.0 for non-deceased patients (p<0.001). Tocilizumab associated to survival only in those patients with overall oxygen saturation below 94% (p=0.008, HR 0.20, CI 0.06-0.66).

3.5. Factors associated with COVID-19 mechanical ventilation

A total of 5,001 patients were analyzed, although the final model included 4,782 patients (219 lost).

Table 8 shows the results of the multivariate analysis excluding the IL-6 value. When including it, the model consisted of 2,328 patients (IL-6 was not assessed in 2,673 subject, the same variables were retained, along with the IL-6 level (continuous) (HR 1.001, CI 95% 1.000-1.001 per 1.0 pg/ml).

The variable "dementia" nearly reached statistical significance: HR 0.14 (CI 95% 0.02-1.14). The rest of the variables mentioned in the previous section were not included in the final model as they did not reach statistical significance

4. Discussion

The analysis of the characteristics of patients hospitalized with COVID -19 in a single institution according to the timing (waves) gives a global view of the pandemic which is worth considering. The number of patients gradually decreased in each wave until the fifth, mainly due to to progressive immunization. In the first wave, hospitals and ICUs were overwhelmed, and the entire hospital focused on COVID-19, suspending any other activities [

5]. Our center, which normally has an average of 100 internal medicine patients and 12 ICU beds, reached over 600 COVID-19 patients and 50 ICU beds. This wave accounted for 35% of the total patients, 39% of all deaths and 27% of intubated patients, and oxygen saturations were the worst. Nevertheless, intubation rate was only 5%, less than half compared to the fifth wave, probably due to the fact that many patients, who in the next waves would have been intubated, did not receive mechanical ventilation given the lack of ICU beds. This could explain why this wave had the longest delay in ICU admission. Although the highest levels of inflammatory parameters were observed during the first wave, the administration of corticosteroids and tocilizumab were the lowest, because of the absence of robust evidence about their effectiveness and the low availability of tocilizumab. Despite that, the proportions of corticosteroid, tocilizumab, and prophylactic LMWH use were higher than those reported in the same period in our country [

15], and the overall mortality among our patients was lower, with similar proportions of patients over 80 and 65 years in both series.

Second wave stood out by reopening measures, taken before summer 2020, and hospital trying to resume its regular activities with flexible COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 areas. Like the fifth wave, which occurred after the following summer ("summer waves"), patients were younger, with lower Charlson score, a higher proportion of immigrant patients, and the highest average oxygen saturation in the emergency department. Undoubtedly, there was a greater availability of hospital resources then, compared to the beginning of the pandemic. The main difference between the two “summer waves” was the mortality rate, much higher in the second than in the fifth wave, when a significant portion of the population was already vaccinated.

The fourth wave was associated to the emergence of the alpha variant, with ICUs still at full capacity after the third wave. A few months later, in June, the delta variant arrived and triggered the fifth wave (in summer) [

8]. These waves had a higher progression to respiratory failure, reflected in the increased use of corticosteroids, tocilizumab, and baricitinib, as well as a higher percentage of ICU admissions with the lowest average delay indicating the increased availability of ICU beds. All these factors may have contributed to the lower mortality during these waves.

The third and sixth waves happened during Christmas. The usual winter flu peak was transformed into a COVID-19 peak at the end of December and throughout January. However, while in the sixth wave the population had almost completed vaccination, during the third only few people over 80 years old had received the vaccine in January, and none before Christmas [

6]. Average age and Charlson score were higher in these waves . The proportion of patients over 80 years old in these two "Christmas waves" was the highest, exceeding 20%. During the third wave, despite the highest proportion of patients with high oxygen requirements, the low ratio of intubated patients and the delay in admission to ICU suggest that the healthcare system became strained again, due to the coexistence of COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients. Lack of evidence regarding the use of remdesivir in hospitalized patients resulted in its marginal use in our center. However, in the third wave, a higher proportion of patients received corticosteroids and tocilizumab, which may partially explain why the inflammatory parameters did not reach the levels of the first wave. It is intriguing that the sixth wave had the highest mortality rate (12%), even higher than during the first wave, although the absolute number was much lower. This wave was marked by almost universal vaccination [

6], Omicron variant [

8] and difficulties to distinguish COVID-19 from SARS-CoV-2 infection, due to universal screening at admission. The proportion of patients with cancer and severe dementia significantly increased compared to previous waves, making it difficult to attribute the fundamental cause of death to the coronavirus in all cases. All severity parameters (oxygen saturation at admission, worst oxygen saturation, need for high-flow oxygen, acute-phase reactants, use of tocilizumab) were better than average, and the number of patients requiring mechanical ventilation decreased compared to the previous two waves. Undoubtedly, mortality in the sixth wave was mostly associated to comorbidities.

Finally, the seventh wave (which could also be named the plateau wave) represented normality. Vaccination was almost universal, no new relevant VOC appeared, and last restrictions were gradually lifted. This wave was different from all previous ones. Its patients had the highest mean age, Charlson score index and readmission rate, but the lowest length of stay and acute-phase reactants levels, and a drastically decrease in the need for intubation was observed (only 6 [1%] patients) . The use of tocilizumab was anecdotal. In short, these were patients with significant comorbidities with a mild COVID-19, who developed a non-severe respiratory disease and whose mortality, like in the sixth wave, was mostly related to their underlying comorbidities than to COVID-19 itself.

Despite these differences, neither mortality nor intubation were associated to any specific wave in multivariant analyses. Regarding the first wave, the clustering of more severe patients, with both desaturation and higher inflammatory markers, accounted for the higher mortality during this period. Furthermore, it was offset by the less number of deaths related to poor performance status than in subsequent waves. On the other hand, anti-inflammatory treatments were used more frequently than reported in other series from the beginning of the pandemic, resulting in slightly lower mortality [

15].

The variables associated with mortality were, as expected: age, cancer, dementia, Charlson score, need for high-flow oxygen, including mechanical ventilation, and inflammatory markers (PCR, IL-6). These factors had been described in previous similar studies [11,15-19]. The use of prophylactic LMWH was associated with lower mortality and this treatment is now strongly recommended in all COVID-19 hospitalized patients [

20], but, as a limiting factor, we could not distinguish patients without prophylactic LMWH from those who received anticoagulated doses before or during admission, variables that are likely associated with different preexisting comorbidities and COVID-19 severity. Need for high-flow oxygen and age appeared as the most powerful predictors of mortality. Age also influences mortality outcomes by waves as well as the impact of tocilizumab and corticosteroids, which lose their association with higher mortality when age is controlled. In other words, the apparent increase in mortality among individuals who used tocilizumab and corticosteroids was due to their higher administration to older people. In fact, the use of tocilizumab seemed to decrease mortality in this group of patients with desaturation, as shown in various studies [

21], and has been recommended by FDA and other panels for the treatment of subjects with COVID-19 that require supplemental oxygen [

22].

It is also noteworthy that we did not find an association between vaccination and overall mortality. In this regard, whe have already assessed the impact of fourth and fifth waves in our center [

23]. In summary, although the mortality rate was higher in the vaccinated group in terms of percentage, this is due to a higher accumulation of comorbidity in this group, and we can ascertain that it would have been even higher without the vaccine [

24].

Regarding the variables associated with mechanical ventilation, patients with cancer (and probably dementia) had a lower probability of being intubated, while the most powerful variables associated with intubation include worse oxygen saturation at admission and those with bilateral pneumonia on chest X-ray upon admission. Once again, the association with tocilizumab and corticosteroids is lost when controlled for age or saturation variables, although the analysis does not suggest that tocilizumab prevented intubation.

Main limitations of our study include the retrospective design and being carried out at a single. We have tried to overcome these limitations with rigorous methods, with the inclusion of all patients admitted to the hospital, accounting for a large number of patients, and the quality of the variables that were prospectively collected in an electronic database for further analysis.