Submitted:

17 January 2024

Posted:

17 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Adjustment of the HR to exercise in vertebrates

| Vertebrate | Resting HR (bpm) | Exercise HRmax (bpm) |

|---|---|---|

| Human | 80 | 190 |

| Rat (mammals) | 320 | 600 |

| Dog (mammals) | 100 | 300 |

| Horse (mammals) | 38 | 207 |

| Golden-collared manakins (birds) | 250 | 1300 |

| Tuna (fishes) | 100 | 205 |

| Salmon (fishes) | 20 | 85 |

| Frog (amphibians) | 25 | 100 |

| Rhinella marina (amphibians) | 20 | 105 |

| Ophisaurus (lizard) (reptiles) | 20 | 60 |

| Iguana (reptiles) | 30 | 100 |

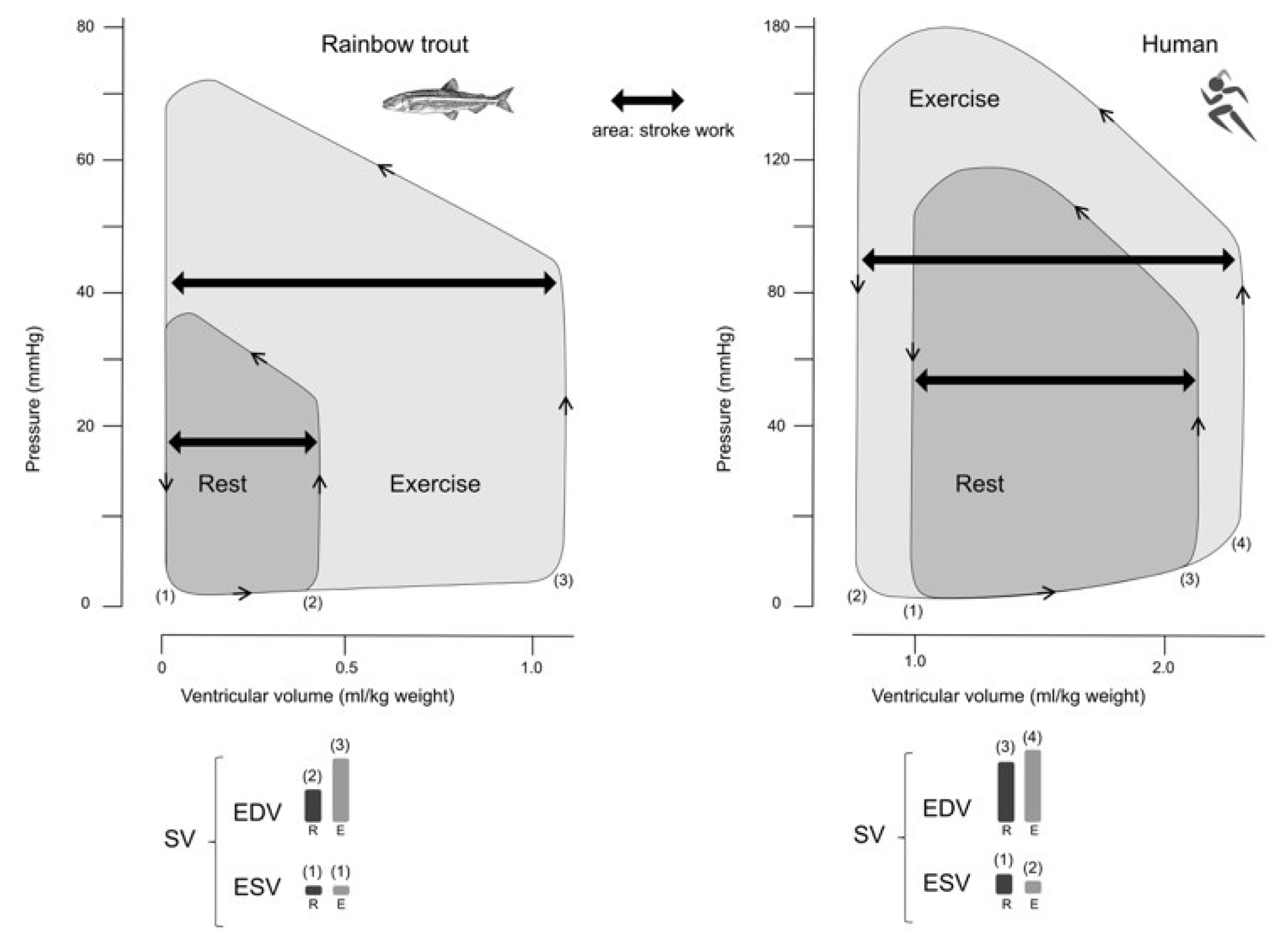

4. Adjustment of the SV to exercise in vertebrates

5. Adjustment of mean arterial pressure (MAP) to exercise in vertebrates

6. Integrated response to exercise in vertebrates

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hunter, P. The evolution of human endurance: Research on the biology of extreme endurance gives insights into its evolution in humans and animals. EMBO Rep 2019, 20, e49396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavin, K.M.; Coen, P.M.; Baptista, L.C.; Bell, M.B.; Drummer, D.; Harper, S.A.; Lixandrao, M.E.; McAdam, J.S.; O'Bryan, S.M.; Ramos, S.; et al. State of Knowledge on Molecular Adaptations to Exercise in Humans: Historical Perspectives and Future Directions. Compr Physiol 2022, 12, 3193–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, D.C.; Erickson, H.H. Highly athletic terrestrial mammals: horses and dogs. Compr Physiol 2011, 1, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavie, C.J.; Arena, R.; Swift, D.L.; Johannsen, N.M.; Sui, X.; Lee, D.C.; Earnest, C.P.; Church, T.S.; O'Keefe, J.H.; Milani, R.V.; et al. Exercise and the cardiovascular system: clinical science and cardiovascular outcomes. Circ Res 2015, 117, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, C.J.; Ozemek, C.; Carbone, S.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Blair, S.N. Sedentary Behavior, Exercise, and Cardiovascular Health. Circ Res 2019, 124, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedrick, M.S.; Hancock, T.V.; Hillman, S.S. Metabolism at the Max: How Vertebrate Organisms Respond to Physical Activity. Compr Physiol 2015, 5, 1677–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Joyce, W.; Hicks, J.W. Similitude in the cardiorespiratory responses to exercise across vertebrates. Curr Opin Physiol 2019, 10, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlin, M.S.; Bisson, I.A.; Shamoun-Baranes, J.; Reichard, J.D.; Sapir, N.; Marra, P.P.; Kunz, T.H.; Wilcove, D.S.; Hedenstrom, A.; Guglielmo, C.G.; et al. Grand challenges in migration biology. Integr Comp Biol 2010, 50, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piersma, T. Why marathon migrants get away with high metabolic ceilings: towards an ecology of physiological restraint. J Exp Biol 2011, 214, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morash, A.J.; Vanderveken, M.; McClelland, G.B. Muscle metabolic remodeling in response to endurance exercise in salmonids. Front Physiol 2014, 5, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, S.; Pierce, B.; Wittenzellner, A.; Langlois, L.; Engel, S.; Speakman, J.R.; Fatica, O.; DeMoranville, K.; Goymann, W.; Trost, L.; et al. The energy savings-oxidative cost trade-off for migratory birds during endurance flight. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burggren, W.W.; Farrell, A.P.; Lillywhite, H.B. Vertebrate cardiovascular systems. In Handbook of Physiology. Comparative physiology; Am. Physiol.Soc.: Bethesda MD, 1997; Volume 1, pp. 215–308. [Google Scholar]

- Katano, W.; Moriyama, Y.; Takeuchi, J.K.; Koshiba-Takeuchi, K. Cardiac septation in heart development and evolution. Dev Growth Differ 2019, 61, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crystal, G.J.; Pagel, P.S. The Physiology of Oxygen Transport by the Cardiovascular System: Evolution of Knowledge. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2020, 34, 1142–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monahan-Earley, R.; Dvorak, A.M.; Aird, W.C. Evolutionary origins of the blood vascular system and endothelium. J Thromb Haemost 2013, 11 Suppl 1, 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowburn, A.S.; Macias, D.; Summers, C.; Chilvers, E.R.; Johnson, R.S. Cardiovascular adaptation to hypoxia and the role of peripheral resistance. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, W.; Wang, T. What determines systemic blood flow in vertebrates? J Exp Biol 2020, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslanger, E. The Evolution of the Cardiovascular System: A Hemodynamic Perspective. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars 2022, 50, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsook, A.H.; Dominelli, P.B.; Angus, S.A.; Senefeld, J.W.; Wiggins, C.C.; Joyner, M.J. The oxygen transport cascade and exercise: Lessons from comparative physiology. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2023, 282, 111442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, J.W.; Wang, T. Arterial blood gases during maximum metabolic demands: Patterns across the vertebrate spectrum. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2021, 254, 110888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, D.; Nourizadeh, S.; De Tomaso, A.W. The biology of the extracorporeal vasculature of Botryllus schlosseri. Dev Biol 2019, 448, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, D.; Taketa, D.A.; Madhu, R.; Kassmer, S.; Loerke, D.; Valentine, M.T.; Tomaso, A.W. Vascular Aging in the Invertebrate Chordate, Botryllus schlosseri. Front Mol Biosci 2021, 8, 626827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefevre, S.; Damsgaard, C.; Pascale, D.R.; Nilsson, G.E.; Stecyk, J.A. Air breathing in the Arctic: influence of temperature, hypoxia, activity and restricted air access on respiratory physiology of the Alaska blackfish Dallia pectoralis. J Exp Biol 2014, 217, 4387–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damsgaard, C.; Baliga, V.B.; Bates, E.; Burggren, W.; McKenzie, D.J.; Taylor, E.; Wright, P.A. Evolutionary and cardio-respiratory physiology of air-breathing and amphibious fishes. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2020, 228, e13406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turko, A.J.; Rossi, G.S.; Wright, P.A. More than Breathing Air: Evolutionary Drivers and Physiological Implications of an Amphibious Lifestyle in Fishes. Physiology (Bethesda) 2021, 36, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, S.S. Cardiac scope in amphibians: transition to terrestrial life. Canadian journal of zoology 1991, 69, 2010–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.; Lauridsen, H.; Pedersen, K.; Andersson, S.A.; van Ooij, P.; Willems, T.; Berger, R.M.F.; Ebels, T.; Jensen, B. Opportunities and short-comings of the axolotl salamander heart as a model system of human single ventricle and excessive trabeculation. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 20491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Ukaj, S.; Gumpenberger, M.; Posautz, A.; Strauss, V. The Amphibian Heart. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract 2022, 25, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Z.R.; Hanken, J. Convergent evolutionary reduction of atrial septation in lungless salamanders. J Anat 2017, 230, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guangming, G.; Zhe, Y.; Mei, Z.; Chenchen, Z.; Jiawei, D.; Dongyu, Z. Comparative Morphology of the Lungs and Skin of two Anura, Pelophylax nigromaculatus and Bufo gargarizans. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 11420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, J.W. The physiological and evolutionary significance of cardiovascular shunting patterns in reptiles. News Physiol Sci 2002, 17, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.; Christoffels, V.M. Reptiles as a Model System to Study Heart Development. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2020, 12, a037226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, B.; Lauridsen, H.; Webb, G.J.W.; Wang, T. Anatomy of the heart of the leatherback turtle. J Anat 2022, 241, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.; Moorman, A.F.; Wang, T. Structure and function of the hearts of lizards and snakes. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2014, 89, 302–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, B.; Joyce, W.; Gregorovicova, M.; Sedmera, D.; Wang, T.; Christoffels, V.M. Low incidence of atrial septal defects in nonmammalian vertebrates. Evol Dev 2020, 22, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitova, E.; Wittnich, C. Cardiac structures in marine animals provide insight on potential directions for interventions for pediatric congenital heart defects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2022, 322, H1–h7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, L.I.Q.; Oliveira, M.; Dias, L.C.; Franco de Oliveira, M.; de Moura, C.E.B.; Magalhães, M.D.S. Heart morphology during the embryonic development of Podocnemis unifilis Trosquel 1948 (Testudines: Podocnemididae). Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2023, 306, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burggren, W.; Filogonio, R.; Wang, T. Cardiovascular shunting in vertebrates: a practical integration of competing hypotheses. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2020, 95, 449–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregorovicova, M.; Bartos, M.; Jensen, B.; Janacek, J.; Minne, B.; Moravec, J.; Sedmera, D. Anguimorpha as a model group for studying the comparative heart morphology among Lepidosauria: Evolutionary window on the ventricular septation. Ecol Evol 2022, 12, e9476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.; Van Den Berg, G.; Van Den Doel, R.; Oostra, R.-J.; Wang, T.; Moorman, A.F.M. Development of the Hearts of Lizards and Snakes and Perspectives to Cardiac Evolution. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, T.T.; Mitchell, G.S.; Bennett, A.F. Cardiovascular responses to graded activity in the lizards Varanus and Iguana. Am J Physiol 1980, 239, R174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, C.A.C.; Taylor, E.W.; Wang, T.; Abe, A.S.; De Andrade, D.O.V. Ablation of the ability to control the right-to-left cardiac shunt does not affect oxygen consumption, specific dynamic action or growth in rattlesnakes,<i>Crotalus durissus</i>. Journal of Experimental Biology 2013, 216, 1881–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishimatsu, A.; Hicks, J.W.; Heisler, N. Analysis of Cardiac Shunting in the Turtle <i>Trachemys</i> (<i>Pseudemys</i>) <i>Scripta</i>: Application of the Three Outflow Vessel Model. Journal of Experimental Biology 1996, 199, 2667–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutilier, R.G.; Shelton, G. Gas exchange, storage and transport in voluntarily diving Xenopus laevis. J Exp Biol 1986, 126, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Hedrick, M.S.; Ihmied, Y.M.; Taylor, E.W. Control and interaction of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems in anuran amphibians. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 1999, 124, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burggren, W.W.; Johansen, K. Circulation and Respiration in Lungfishes (Dipnoi). J Morphol 1986, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.B.; Lee, H.J. Breathing air in air: In what ways might extant amphibious fish biology relate to prevailing concepts about early tetrapods, the evolution of vertebrate air breathing, and the vertebrate land transition? Physiol Biochem Zool 2004, 77, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, D.J. Cardio-respiratory modeling in fishes and the consequences of the evolution of airbreathing. Cardioscience 1994, 5, 167–171. [Google Scholar]

- Filogonio, R.; Wang, T.; Taylor, E.W.; Abe, A.S.; Leite, C.A. Vagal tone regulates cardiac shunts during activity and at low temperatures in the South American rattlesnake, Crotalus durissus. J Comp Physiol B 2016, 186, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, A.R.; Smith, B.; Crossley, D.A. Regulation of blood flow in the pulmonary and systemic circuits during submerged swimming in common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). J Exp Biol 2019, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corno, A.F.; Zhou, Z.; Uppu, S.C.; Huang, S.; Marino, B.; Milewicz, D.M.; Salazar, J.D. The Secrets of the Frogs Heart. Pediatr Cardiol 2022, 43, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S. Use of Frogs as a Model to Study the Etiology of HLHS. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, W.; White, D.W.; Raven, P.B.; Wang, T. Weighing the evidence for using vascular conductance, not resistance, in comparative cardiovascular physiology. J Exp Biol 2019, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, A.C.; Tran, V.H.; Spicer, D.E.; Rob, J.M.H.; Sridharan, S.; Taylor, A.; Anderson, R.H.; Jensen, B. Sequential segmental analysis of the crocodilian heart. J Anat 2017, 231, 484–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poelmann, R.E.; Gittenberger-de Groot, A.C.; Goerdajal, C.; Grewal, N.; De Bakker, M.A.G.; Richardson, M.K. Ventricular Septation and Outflow Tract Development in Crocodilians Result in Two Aortas with Bicuspid Semilunar Valves. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barske, J.; Eghbali, M.; Kosarussavadi, S.; Choi, E.; Schlinger, B.A. The heart of an acrobatic bird. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2019, 228, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.H.; Sheftel, B.I.; Jensen, B. Anatomy of the heart with the highest heart rate. J Anat 2022, 241, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, B.; Wang, T.; Moorman, A.F.M. Evolution and Development of the Atrial Septum. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2019, 302, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, S.; Tretter, J.T.; Spicer, D.E.; Bolender, D.L.; Anderson, R.H. What is the real cardiac anatomy? Clin Anat 2019, 32, 288–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlatt, U. Comparative anatomy of the heart of mammals. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 1990, 98, 73–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franziska Hein, R.; Kiefer, I.; Pees, M. A Spectral Computed Tomography Contrast Study: Demonstration of the Avian Cardiovascular Anatomy and Function. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract 2022, 25, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, A.; Adams, J.W.; Vaccarezza, M. The vertebrate heart: an evolutionary perspective. J Anat 2017, 231, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansford, R.; Rugonyi, S. Follow Me! A Tale of Avian Heart Development with Comparisons to Mammal Heart Development. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 2020, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, R.; Wheen, P.; Brandon, L.; Maree, A.; Kenny, R.A. Heart rate: control mechanisms, pathophysiology and assessment of the neurocardiac system in health and disease. Qjm 2022, 115, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, W.; Pan, Y.K.; Garvey, K.; Saxena, V.; Perry, S.F. Regulation of heart rate following genetic deletion of the ß1 adrenergic receptor in larval zebrafish. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2022, 235, e13849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, W.; Wang, T. Regulation of heart rate in vertebrates during hypoxia: A comparative overview. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2022, 234, e13779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoyek, M.R.; MacDonald, E.A.; Mantifel, M.; Baillie, J.S.; Selig, B.M.; Croll, R.P.; Smith, F.M.; Quinn, T.A. Drivers of Sinoatrial Node Automaticity in Zebrafish: Comparison With Mechanisms of Mammalian Pacemaker Function. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 818122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E.W.; Wang, T.; Leite, C.A.C. An overview of the phylogeny of cardiorespiratory control in vertebrates with some reflections on the 'Polyvagal Theory'. Biol Psychol 2022, 172, 108382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, W.; Wang, T. How cardiac output is regulated: August Krogh's proto-Guytonian understanding of the importance of venous return. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2021, 253, 110861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh, A. The Progress of Physiology. Science 1929, 70, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A.P. From Hagfish to Tuna: A Perspective on Cardiac Function in Fish. Physiological Zoology 1991, 64, 1137–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukens, B.J.D.; Kristensen, D.L.; Filogonio, R.; Carreira, L.B.T.; Sartori, M.R.; Abe, A.S.; Currie, S.; Joyce, W.; Conner, J.; Opthof, T.; et al. The electrocardiogram of vertebrates: Evolutionary changes from ectothermy to endothermy. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2019, 144, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhard, S.; van Eif, V.; Garric, L.; Christoffels, V.M.; Bakkers, J. On the Evolution of the Cardiac Pacemaker. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillywhite, H.B.; Zippel, K.C.; Farrell, A.P. Resting and maximal heart rates in ectothermic vertebrates. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 1999, 124, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parlin, A.F.; Schaeffer, P.J. Cardiovascular contributions and energetic costs of thermoregulation in ectothermic vertebrates. J Exp Biol 2022, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuyama, J.; Shiozawa, M.; Shiode, D. Heart rate and cardiac response to exercise during voluntary dives in captive sea turtles (Cheloniidae). Biol Open 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A.P. Cardiac scope in lower vertebrates. Canadian Journal of Zoology 1991, 69, 1981–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, A.; Esser, M.; López, R.; Boffi, F. Relationship between Resting and Recovery Heart Rate in Horses. Animals 2020, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, T.; van Mourik, R.A.; Martin, K.J.; Eijsvogels, T.M.H.; Longoria, K.A. 100 Long-Distance Triathlons in 100 Days: A Case Study on Ultraendurance, Biomarkers, and Physiological Outcomes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2023, 18, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, T.I.; Jeon, J.Y.; Lindsay, T.; Westgate, K.; Perez-Pozuelo, I.; Hollidge, S.; Wijndaele, K.; Rennie, K.; Forouhi, N.; Griffin, S.; et al. Resting heart rate is a population-level biomarker of cardiorespiratory fitness: The Fenland Study. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0285272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burggren, W.; Farrell, A.; Lillywhite, H. Vertebrate cardiovascular systems. Handbook of Physiology. Comprehensive physiology 2010, 215–308. [Google Scholar]

- Filogonio, R.; Dubansky, B.D.; Dubansky, B.H.; Leite, C.A.C.; Crossley, D.A. , 2nd. Prenatal hypoxia affects scaling of blood pressure and arterial wall mechanics in the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2021, 260, 111023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filogonio, R.; Dubansky, B.D.; Dubansky, B.H.; Wang, T.; Elsey, R.M.; Leite, C.A.C.; Crossley, D.A. , 2nd. Arterial wall thickening normalizes arterial wall tension with growth in American alligators, Alligator mississippiensis. J Comp Physiol B 2021, 191, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyerges-Bohák, Z.; Nagy, K.; Rózsa, L.; Póti, P.; Kovács, L. Heart rate variability before and after 14 weeks of training in Thoroughbred horses and Standardbred trotters with different training experience. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0259933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.; Stieglitz, J.D.; Cox, G.K.; Heuer, R.M.; Benetti, D.D.; Grosell, M.; Crossley, D.A. , 2nd. Cardio-respiratory function during exercise in the cobia, Rachycentron canadum: The impact of crude oil exposure. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 2017, 201, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, W.; Miller, T.E.; Elsey, R.M.; Wang, T.; Crossley, D.A. , 2nd. The effects of embryonic hypoxic programming on cardiovascular function and autonomic regulation in the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) at rest and during swimming. J Comp Physiol B 2018, 188, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, W.; Egginton, S.; Farrell, A.P.; Crockett, E.L.; O'Brien, K.M.; Axelsson, M. Exploring nature's natural knockouts: in vivo cardiorespiratory performance of Antarctic fishes during acute warming. J Exp Biol 2018, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.C.; Santos, A.M.; Jorge, P.I.; Lafuente, P. A protocol for the determination of the maximal lactate steady state in working dogs. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2020, 60, 942–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farinatti, P.; Monteiro, W.; Oliveira, R.; Crisafulli, A. Cardiorespiratory responses and myocardial function within incremental exercise in healthy unmedicated older vs. young men and women. Aging Clin Exp Res 2018, 30, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagberg, J.M.; Allen, W.K.; Seals, D.R.; Hurley, B.F.; Ehsani, A.A.; Holloszy, J.O. A hemodynamic comparison of young and older endurance athletes during exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1985, 58, 2041–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A.P.; Davie, P.S.; Franklin, C.E.; Johansen, J.A.; Brill, R.W. Cardiac physiology in tunas. I. In vitro perfused heart preparations from yellowfin and skipjack tunas. Canadian Journal of Zoology 1992, 70, 1200–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Taylor, E.W.; Andrade, D.; Abe, A.S. Autonomic control of heart rate during forced activity and digestion in the snake Boa constrictor. J Exp Biol 2001, 204, 3553–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornicke, H.; von Engelhardt, W.; Ehrlein, H.J. Effect of exercise on systemic blood pressure and heart rate in horses. Pflugers Arch 1977, 372, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, A.P. A review of cardiac performance in the teleost heart: intrinsic and humoral regulation. Canadian Journal of Zoology 1984, 62, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barske, J.; Fusani, L.; Wikelski, M.; Feng, N.Y.; Santos, M.; Schlinger, B.A. Energetics of the acrobatic courtship in male golden-collared manakins (Manacus vitellinus). Proc Biol Sci 2014, 281, 20132482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grubb, B.; Jorgensen, D.D.; Conner, M. Cardiovascular changes in the exercising emu. J Exp Biol 1983, 104, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noakes, T.D. Lord of running; Oxford University Press: Cape Town, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Physick-Sheard, P.W. Cardiovascular response to exercise and training in the horse. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 1985, 1, 383–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navas de Solis, C. Cardiovascular Response to Exercise and Training, Exercise Testing in Horses. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 2019, 35, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco-Otto, P.; Bond, S.; Sides, R.; Bayly, W.; Leguillette, R. Conditioning equine athletes on water treadmills significantly improves peak oxygen consumption. Vet Rec 2020, 186, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, D.C.; Erickson, H.H. 31- Heart and vessels: Function during exercise and training adaptations. In Equine Sports Medicine and Surgery (Second Edition), Hinchcliff, K.W., Kaneps, A.J., Geor, R.J., Eds.; W.B. Saunders: 2014; pp. 667-694.

- Hillman, S.S.; Hancock, T.V.; Hedrick, M.S. A comparative meta-analysis of maximal aerobic metabolism of vertebrates: implications for respiratory and cardiovascular limits to gas exchange. J Comp Physiol B 2013, 183, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ask, J.A. Comparative aspects of adrenergic receptors in the hearts of lower vertebrates. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol 1983, 76, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.W.; Leite, C.A.; Sartori, M.R.; Wang, T.; Abe, A.S.; Crossley, D.A. , 2nd. The phylogeny and ontogeny of autonomic control of the heart and cardiorespiratory interactions in vertebrates. J Exp Biol 2014, 217, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, P.J.; Clifford, P.S.; Crandall, C.G.; Smith, S.A.; Fadel, P.J. Integration of Central and Peripheral Regulation of the Circulation during Exercise: Acute and Chronic Adaptations. Compr Physiol 2017, 8, 103–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, P.S.; Hadaya, J.; Khalsa, S.S.; Yu, C.; Chang, R.; Shivkumar, K. The vagus nerve in cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology: From evolutionary insights to clinical medicine. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2024, 156, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Filogonio, R.; Joyce, W. Chapter 1 - Evolution of the cardiovascular autonomic nervous system in vertebrates. In Primer on the Autonomic Nervous System (Fourth Edition), Biaggioni, I., Browning, K., Fink, G., Jordan, J., Low, P.A., Paton, J.F.R., Eds.; Academic Press: 2023; pp. 3-9.

- de Marneffe, M.; Jacobs, P.; Haardt, R.; Englert, M. Variations of normal sinus node function in relation to age: role of autonomic influence. Eur Heart J 1986, 7, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, K.; Sugano, S. Relation of intrinsic heart rate and autonomic nervous tone to resting heart rate in the young and the adult of various domestic animals. Nihon Juigaku Zasshi 1989, 51, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeifer, M.A.; Weinberg, C.R.; Cook, D.; Best, J.D.; Reenan, A.; Halter, J.B. Differential changes of autonomic nervous system function with age in man. Am J Med 1983, 75, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavorsky, G.S. Evidence and possible mechanisms of altered maximum heart rate with endurance training and tapering. Sports Med 2000, 29, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porges, S.W. The vagal paradox: A polyvagal solution. Compr Psychoneuroendocrinol 2023, 16, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.C.; Taberner, A.J.; Loiselle, D.S.; Tran, K. Cardiac efficiency and Starling's Law of the Heart. J Physiol 2022, 600, 4265–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, V.; van der Velden, J. Historical perspective on heart function: the Frank-Starling Law. Biophys Rev 2015, 7, 421–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiels, H.A.; White, E. The Frank-Starling mechanism in vertebrate cardiac myocytes. J Exp Biol 2008, 211, 2005–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A.P. Circulation of body fluids. In Environmental and metabolic animal physiology, Prosser, C.L., Ed.; Wiley/Liss: New York, 1991; pp. 509–558. [Google Scholar]

- Tello, K.; Naeije, R.; de Man, F.; Guazzi, M. Pathophysiology of the right ventricle in health and disease: an update. Cardiovasc Res 2023, 119, 1891–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furrer, R.; Hawley, J.A.; Handschin, C. The molecular athlete: exercise physiology from mechanisms to medals. Physiol Rev 2023, 103, 1693–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, R.B. Cardiovascular physiology. In Textbook of veterinary physiology, 4th ed.; Saunders/Elsevier St. Louis, Mo.: St. Louis, Mo, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.P.; Fregin, G.F. Cardiorespiratory and metabolic responses to treadmill exercise in the horse. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 1981, 50, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derman, K.D.; Noakes, T.D. Comparative Aspects of Exercise Physiology. In The athletic horse, Hodgson, D.R., Rose, R.J., Eds.; WB Saunders: Philadelphia, 1984; pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mazan, M. Equine exercise physiology-challenges to the respiratory system. Anim Front 2022, 12, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, W.; Elsey, R.M.; Wang, T.; Crossley, D.A. , 2nd. Maximum heart rate does not limit cardiac output at rest or during exercise in the American alligator ( Alligator mississippiensis). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2018, 315, R296–r302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A.P.; Jones, D.R. The Heart. In The Cardiovascular System, Hoar, W.S., Randall, D.J., Farrell, A.P., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 1992; pp. 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Mazza, R.; Pasqua, T.; Gattuso, A. Cardiac heterometric response: the interplay between Catestatin and nitric oxide deciphered by the frog heart. Nitric Oxide 2012, 27, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reil, J.C.; Reil, G.H.; Kovács, Á.; Sequeira, V.; Waddingham, M.T.; Lodi, M.; Herwig, M.; Ghaderi, S.; Kreusser, M.M.; Papp, Z.; et al. CaMKII activity contributes to homeometric autoregulation of the heart: A novel mechanism for the Anrep effect. J Physiol 2020, 598, 3129–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, M.; Williams, A.M.; Mannozzi, J.; Konecny, F.; Hoiland, R.L.; Wainman, L.; Erskine, E.; Duffy, J.; Manouchehri, N.; So, K.; et al. A cross-species validation of single-beat metrics of cardiac contractility. J Physiol 2022, 600, 4779–4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir, W.W.; Hamlin, R.L. Myocardial Contractility: Historical and Contemporary Considerations. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vornanen, M. Regulation of contractility of the fish (Carassius carassius L.) heart ventricle. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Comparative Pharmacology 1989, 94, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driedzic, W.R.; Gesser, H. Ca2+ protection from the negative inotropic effect of contraction frequency on teleost hearts. Journal of Comparative Physiology B 1985, 156, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driedzic, W.R.; Gesser, H. Differences in force-frequency relationships and calcium dependency between elasmobranch and teleost hearts. Journal of Experimental Biology 1988, 140, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesser, H.; Poupa, O. Acidosis and cardiac muscle contractility: comparative aspects. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol 1983, 76, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, M.; Shahriari, A.; Roa, J.N.; Tresguerres, M.; Farrell, A.P. Differential effects of bicarbonate on severe hypoxia- and hypercapnia-induced cardiac malfunctions in diverse fish species. J Comp Physiol B 2021, 191, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Sanchez, Y.; Rodriguez de Yurre, A.; Argenziano, M.; Escobar, A.L.; Ramos-Franco, J. Transmural Autonomic Regulation of Cardiac Contractility at the Intact Heart Level. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López Alarcón, M.M.; Rodríguez de Yurre, A.; Felice, J.I.; Medei, E.; Escobar, A.L. Phase 1 repolarization rate defines Ca(2+) dynamics and contractility on intact mouse hearts. J Gen Physiol 2019, 151, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazmi, M.; Escobar, A.L. Autonomic Regulation of the Goldfish Intact Heart. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 793305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharin, S.; Shmakov, D. A comparative study of contractility of the heart ventricle in some ectothermic vertebrates. Acta Herpetologica, 2009, 4, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, C.E.; Davie, P.S. Myocardial power output of an isolated eel (Anguilla dieffenbachii) heart preparation in response to adrenaline. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Comparative Pharmacology 1992, 101, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.G.L.; Gamperl, A.K.; Syme, D.A.; Weber, L.P.; Rodnick, K.J. Echocardiography and electrocardiography reveal differences in cardiac hemodynamics, electrical characteristics, and thermal sensitivity between northern pike, rainbow trout, and white sturgeon. J Exp Zool A Ecol Integr Physiol 2019, 331, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, N.C.; Shabetai, R.; Graham, J.B.; Hoit, B.D.; Sunnerhagen, K.S.; Bhargava, V. Cardiac function of the leopard shark, Triakis semifasciata. Journal of Comparative Physiology B 1990, 160, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.; Burggren, W.W. Venous return and cardiac filling in varanid lizards. J. Exp. Biol 1984, 113, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brijs, J.; Sandblom, E.; Axelsson, M.; Sundell, K.; Sundh, H.; Kiessling, A.; Berg, C.; Grans, A. Remote physiological monitoring provides unique insights on the cardiovascular performance and stress responses of freely swimming rainbow trout in aquaculture. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 9090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.R.; Fennell, W.H.; Young, J.B.; Palomo, A.R.; Quinones, M.A. Differential systemic arterial and venous actions and consequent cardiac effects of vasodilator drugs. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1982, 24, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tota, B.; Acierno, R.; Agnisola, C. Mechanical Performance of the Isolated and Perfused Heart of the Haemoglobinless Antarctic Icefish Chionodraco hamatus (Lonnberg): Effects of Loading Conditions and Temperature. 1991. [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, A.; Kitada, K.; Suzuki, M. Blood pressure adaptation in vertebrates: comparative biology. Kidney Int 2022, 102, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burggren, W.W. Central Cardiovascular Function in Amphibians: Qualitative Influences of Phylogeny, Ontogeny, and Season. In Mechanisms of Systemic Regulation. Advances in Comparative and Environmental Physiology, Heisler, N., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin Heidelberg, 1995; Volume vol 21, pp. 175-197. [Google Scholar]

- Enok, S.; Slay, C.; Abe, A.S.; Hicks, J.W.; Wang, T. Intraspecific scaling of arterial blood pressure in the Burmese python. J Exp Biol 2014, 217, 2232–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, R.H.; Warren, J.V.; Gauer, O.H.; Patterson, J.L., Jr.; Doyle, J.T.; Keen, E.N.; Mc, G.M. Circulation of the giraffe. Circ Res 1960, 8, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, C.B.; Wang, T.; Assersen, K.; Iversen, N.K.; Damkjaer, M. Does mean arterial blood pressure scale with body mass in mammals? Effects of measurement of blood pressure. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2018, 222, e13010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Heart mass and the maximum cardiac output of birds and mammals: implications for estimating the maximum aerobic power input of flying animals. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1997, 29, 3447–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.L. The cardiovascular system: anatomy, physiology, and adaptations to exercise and training. In The athletic horse, Hodgson, D.R., Rose, R.J., Eds.; WB Saunders: Philadelphia, 1994; pp. 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, E.F. The innervation of the human heart. IV. (1) The fiber connections of the nerves with the perimysial plexus (Gerlach-Hofmann); (2) The role of nerve tissues in the repair of infarcts. Arch Pathol 1963, 75, 378–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturkie, P.D.; Poorvin, D.; Ossorio, N. Levels of epinephrine and norepinephrine in blood and tissues of duck, pigeon, turkey, and chicken. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1970, 135, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, S.S. Integration of blood flow control to skeletal muscle: key role of feed arteries. Acta Physiol Scand 2000, 168, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantzler, W.H. Comparative Physiology of the Vertebrate Kidney; Springer-Verlag: New York, 2016; p. 292. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, P.K.; Furspan, P.B.; Sawyer, W.H. Evolution of neurohypophyseal hormone actions in vertebrates. American Zoologist 1983, 23, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, D.; Luft, F.C.; Bader, M.; Ganten, D.; Andrade-Navarro, M.A. Emergence and evolution of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. J Mol Med (Berl) 2012, 90, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, H. Renin-angiotensin system in vertebrates: phylogenetic view of structure and function. Anat Sci Int 2017, 92, 215–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerra, M.C. Cardiac distribution of the binding sites for natriuretic peptides in vertebrates. Cardioscience 1994, 5, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kipryushina, Y.O.; Yakovlev, K.V.; Odintsova, N.A. Vascular endothelial growth factors: A comparison between invertebrates and vertebrates. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2015, 26, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, J.A.; Forgan, L.G.; Cameron, M.S. The evolution of nitric oxide signalling in vertebrate blood vessels. J Comp Physiol B 2015, 185, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, D.W.; Olson, K.R. Response of rainbow trout to constant-pressure and constant-volume hemorrhage. Am J Physiol 1989, 257, R1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, S.S.; Withers, P.C. The hemodynamic consequences of hemorrhage and hypernatremia in two amphibians. J Comp Physiol B 1988, 157, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, A.W.; Kozubowski, M.M. Partitioning of body fluids and cardiovascular responses to circulatory hypovolaemia in the turtle, Pseudemys scripta elegans. Journal of experimental biology 1985, 116, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, A.W.; Lillywhite, H.B. Maintenance of blood volume in snakes: transcapillary shifts of extravascular fluids during acute hemorrhage. Journal of Comparative Physiology B 1985, 155, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djojosugito, A.M.; Folkow, B.; Kovach, A.G. The mechanisms behind the rapid blood volume restoration after hemorrhage in birds. Acta Physiol Scand 1968, 74, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, S.L.; Gildersleeve, R.P. Comparison of recovery from hemorrhage in birds and mammals. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol 1987, 87, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Prampero, P.E. Metabolic and circulatory limitations to VO2 max at the whole animal level. Journal of Experimental Biology 1985, 115, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, P.J.; West, N.H.; Jones, D.R. Respiratory and cardiovascular responses of the pigeon to sustained, level flight in a wind-tunnel. Journal of Experimental Biology 1977, 71, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korner, P.I. Integrative neural cardiovascular control. Physiol Rev 1971, 51, 312–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, M.; Davison, W.; Forster, M.E.; Farrell, A.P. Cardiovascular responses of the red-blooded Antarctic fishes Pagothenia bernacchii and P. borchgrevinki. Journal of Experimental Biology 1992, 167, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.H.; Longworth, K.E.; Lindholm, A.; Conley, K.E.; Karas, R.H.; Kayar, S.R.; Taylor, C.R. Oxygen transport during exercise in large mammals. I. Adaptive variation in oxygen demand. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1989, 67, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, R.W.; Bushnell, P.G. Metabolic and cardiac scope of high energy demand teleosts, the tunas. Canadian Journal of Zoology 1991, 69, 2002–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolok, A.S.; Spooner, M.R.; Farrell, A.P. The effect of exercise on the cardiac output and blood flow distribution of the largescale sucker Catostomus macrocheilus. Journal of Experimental Biology 1993, 183, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, D.J.; Daxboeck, C. Cardiovascular changes in the rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri Richardson) during exercise. Canadian Journal of Zoology 1982, 60, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorarensen, H.; McLean, E.; Donaldson, E.M.; Farrell, A.P. The blood vasculature of the gastrointestinal tract in chinook, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Walbaum), and coho, O. kisutch (Walbaum), salmon. Journal of fish biology 1991, 38, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, M.; Fritsche, R. Effects of exercise, hypoxia and feeding on the gastrointestinal blood flow in the Atlantic cod Gadus morhua. Journal of Experimental Biology 1991, 158, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canty, A.A.; Farrell, A.P. Intrinsic regulation of flow in an isolated tail preparation of the ocean pout (Macrozoarces americanus). Canadian journal of zoology, 1985, 63, 2013–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, P.B. Adrenergic receptors and the regulation of vascular resistance in bullfrog tadpoles (Rana catesbeiana). J Comp Physiol B 1992, 162, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, P.J.; Milsom, W.K.; Woakes, A.J. Respiratory, cardiovascular and metabolic adjustments during steady state swimming in the green turtle,Chelonia mydas. Journal of Comparative Physiology B 1984, 154, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, S.S.; Withers, P.C.; Palioca, W.B.; Ruben, J.A. Cardiovascular consequences of hypercalcemia during activity in two species of amphibian. Journal of Experimental Zoology 1987, 242, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, P.C.; Hillman, S.S.; Simmons, L.A.; Zygmunt, A.C. Cardiovascular adjustments to enforced activity in the anuran amphibian, Bufo marinus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology 1988, 89, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, N.H.; Butler, P.J.; Bevan, R.M. Pulmonary blood flow at rest and during swimming in the green turtle, Chelonia mydas. Physiological zoology 1992, 65, 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatova, T.S.; Abramochkin, D.V.; Shiels, H.A. Thermal acclimation and seasonal acclimatization: a comparative study of cardiac response to prolonged temperature change in shorthorn sculpin. J Exp Biol 2019, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).