Submitted:

05 July 2023

Posted:

07 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and reagents

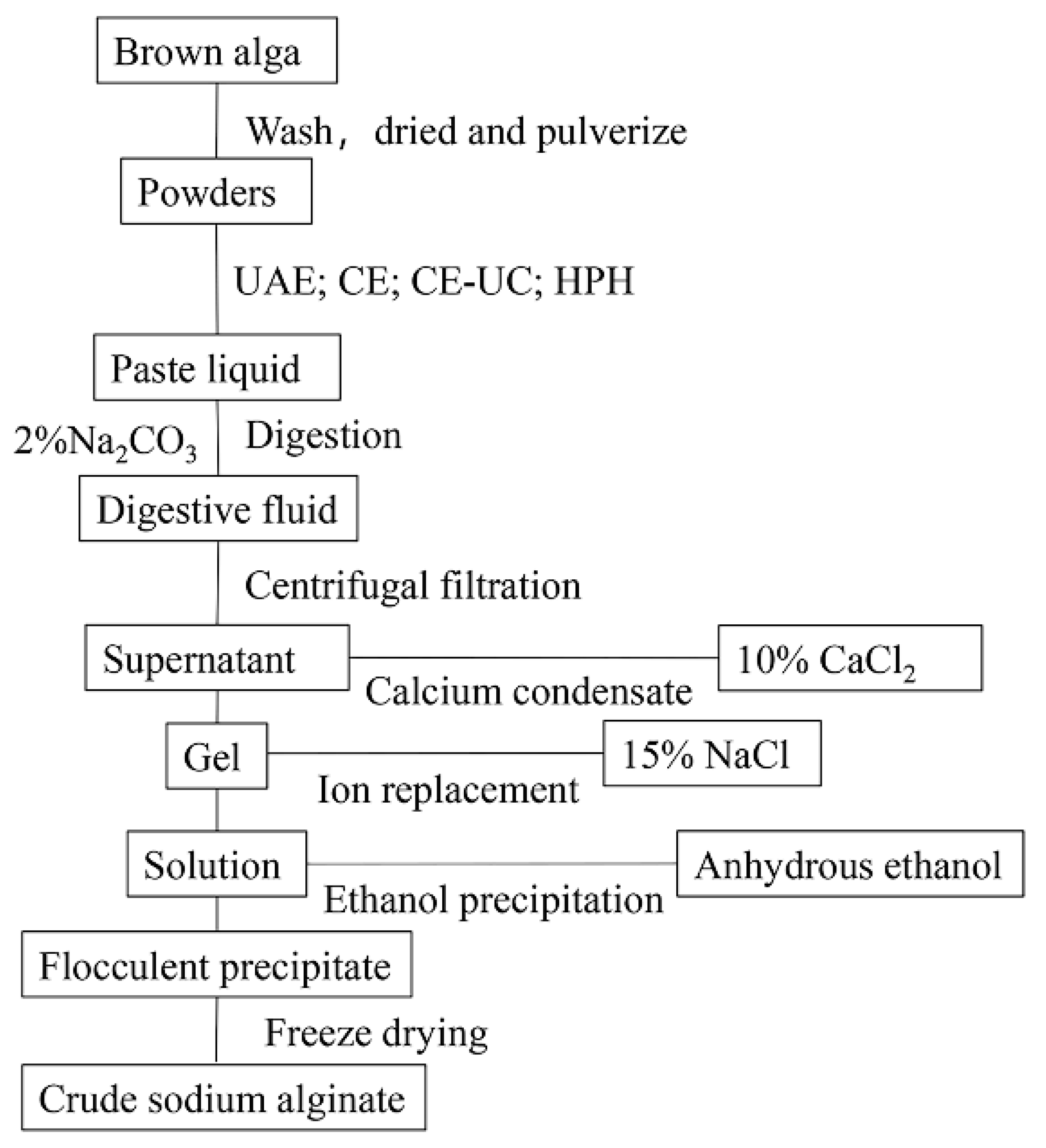

2.1. Extraction process

- L. japonica was soaked in fresh water for 4 hours and washed three times with distilled water to remove impurities. The plant material was then dried and ground into powder.

- A solution of L. japonica was prepared by soaking 2.0 g of the plant material in 200 mL of pure water for 1 hour. The L. japonica solution was then subjected to different pretreatment methods, including HPH, UAE, CE, and CE-UC.

- After adding 30 mL of a 2% Na2CO3 and EDTA (with or without) solution, the homogenate was incubated at 50°C for 3 hours. The mixture was then centrifuged, and the supernatant was adjusted to the desired pH using 1 M HCl.

- Following this, 20 mL of 10% calcium chloride was added and the mixture was allowed to stand. The resulting precipitate was then filtered and washed twice with distilled water to obtain a yellow-white gelatinous precipitate.

- The precipitate was dissolved in 20 mL 15% sodium chloride solution for ion exchange. The solution was then filtrated using medical gauze. Subsequently, 100 mL of anhydrous ethanol was added to induce precipitation. The resulting white flocculent precipitates were obtained through filtration.

- The precipitates were collected and frozen at -80°C for 12 hours, followed by freeze-dried for 8 hours using a vacuum freeze dryer. The dried precipitates were then crushed to obtain crude sodium alginate.

2.1.1. Extraction process of the CE method

- Take 2.00 g of L. japonica powder with a 100-mesh size and add tap water in a 1:50 ratio to obtain a total volume of 100 mL.

- Adjust the pH value to 6 and add 3% cellulase of L. japonica powder, 3% pectinase, and 1% papain. Stir the mixture well and transfer it to a 50℃ water bath for 3 hours. After the reaction, inactivate the enzyme solution by boiling it in water for 15 minutes.

- Add 24 mL of a 2% sodium carbonate solution and digest the mixture in a 50℃ water bath for 3 hours. Centrifuge the digested enzyme solution at 8500 r/min for 10 minutes and remove the supernatant. Adjust the pH of the supernatant to 6. Proceed with the subsequent operations as described in section 2.2 from step (4) to step (6).

2.1.1. Extraction process of the UAE method

- Take 2.00g of L. japonica powder with a 100-mesh size and stir it into tap water at a material-to-liquid ratio of 1:50.

- Use an ultrasonic cell crusher to break the samples for 10 minutes with the following conditions: 350 W of output power, a temperature of 30℃, and a working time and interval of 2 seconds.

- Add 24 mL of a 2% sodium carbonate and digest it in a water bath at 50℃ for 3 hours. After digestion, centrifuge the enzymolysis solution at 8500 r/min for 10 min. Collect the supernatant and adjust its pH to 6. The subsequent operations are the same as section 2.2, from (4) - (6).

2.1.1. Extraction process of the CE-UC method

- Take 2.00g of 100-mesh L. japonica powder and stir it into tap water at a material to liquid ratio of 1:50. The samples were then subjected to ultrasonic cell crushing for 10 minutes using a 350 W power, 30℃ temperature, and 2 s working time and intervals.

- Adjust the pH value to 6 and add L. japonica powder with 3% cellulase, 3% pectinase, and 1% papain. Stir the mixture well and place it in a 50℃ constant temperature water bath for enzymolysis for 3 hours. After the enzymolysis reaction, the enzyme solution was inactivated by boiling and heating for 15 minutes.

- Add 24 mL of L. japonica powder in a 2% sodium carbonate solution and digest it in a 50℃ water bath for 3 hours. After digestion, the enzymolysis solution was centrifuged at 8500 r/min for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was collected and adjusted to pH 6. Subsequent operations are the same as section 2.2, steps (4) - (6).

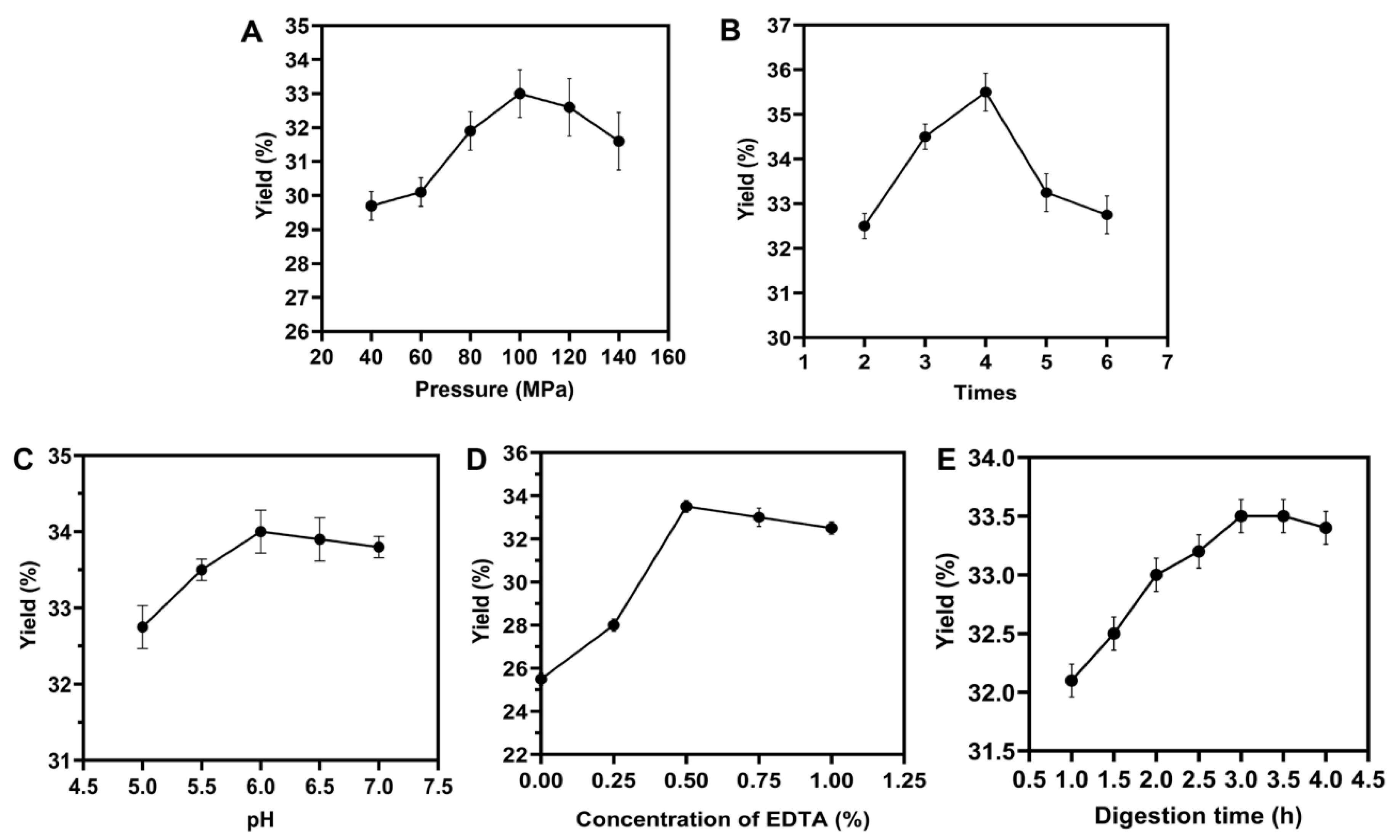

2.1.1. Single factor experiment of the HPH method

2.1. Characterization of sodium alginate

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimization for the single factor extraction condition for the HPH extraction

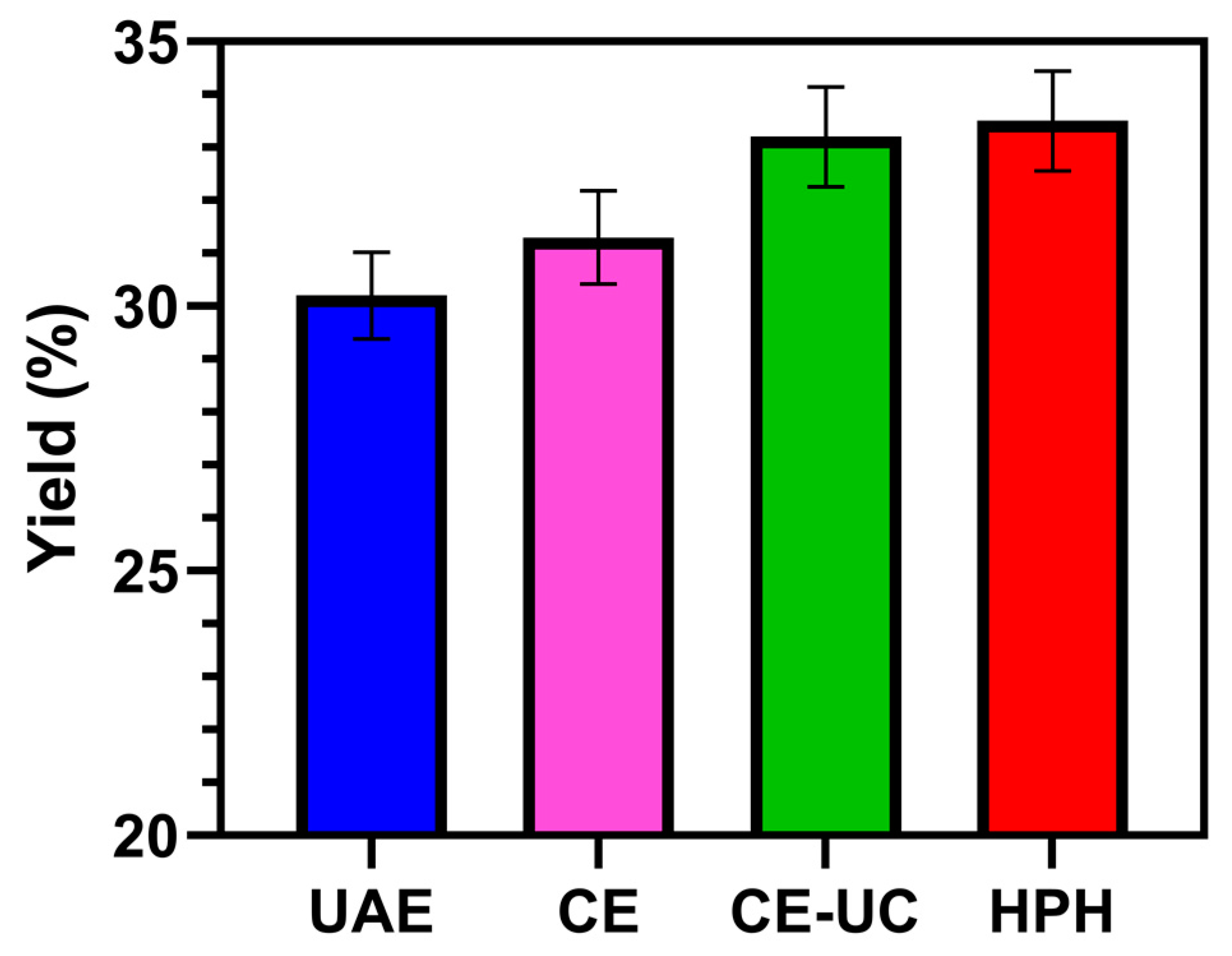

3.2. Compared with yield with other extraction methods

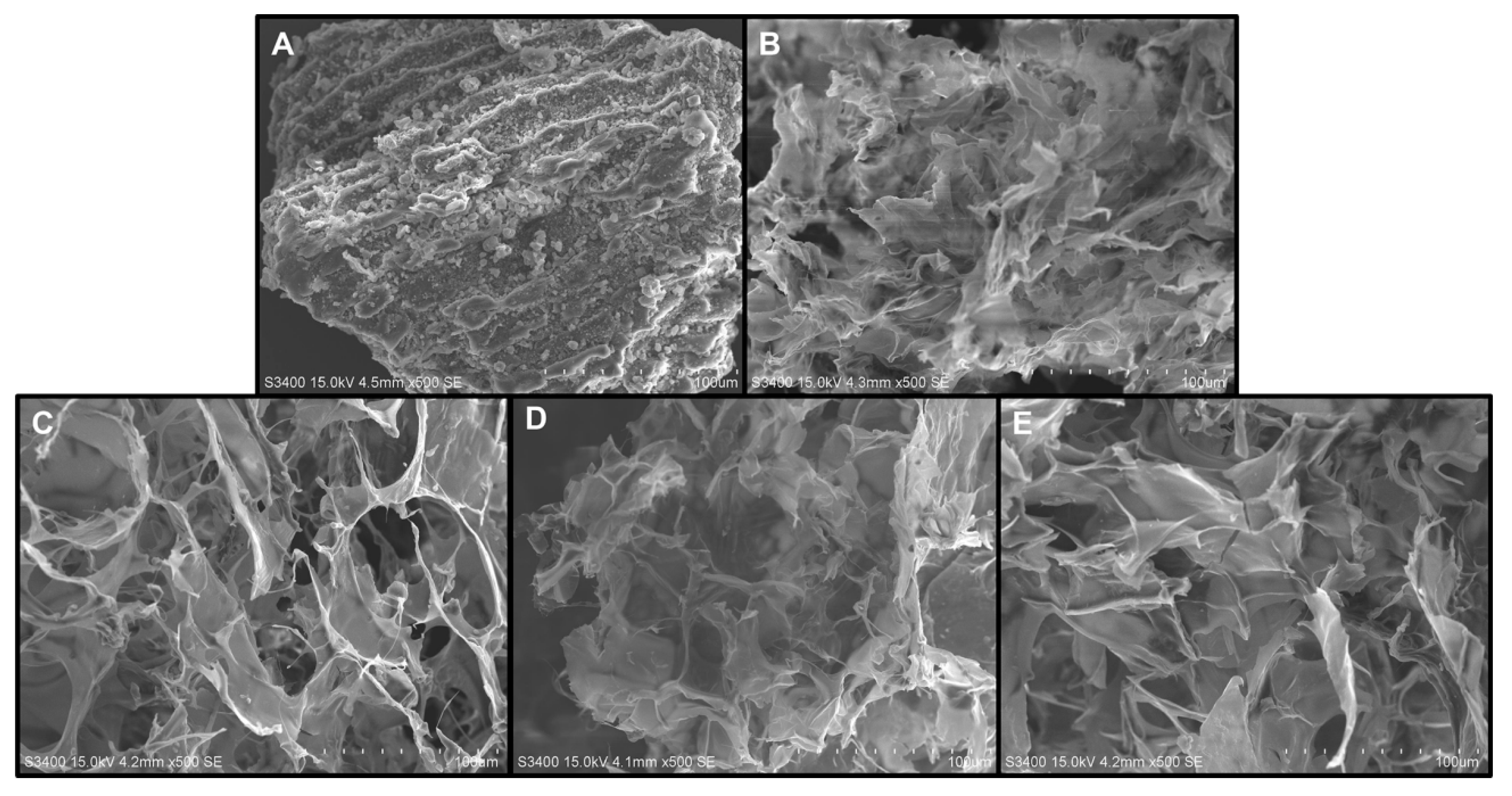

3.3. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

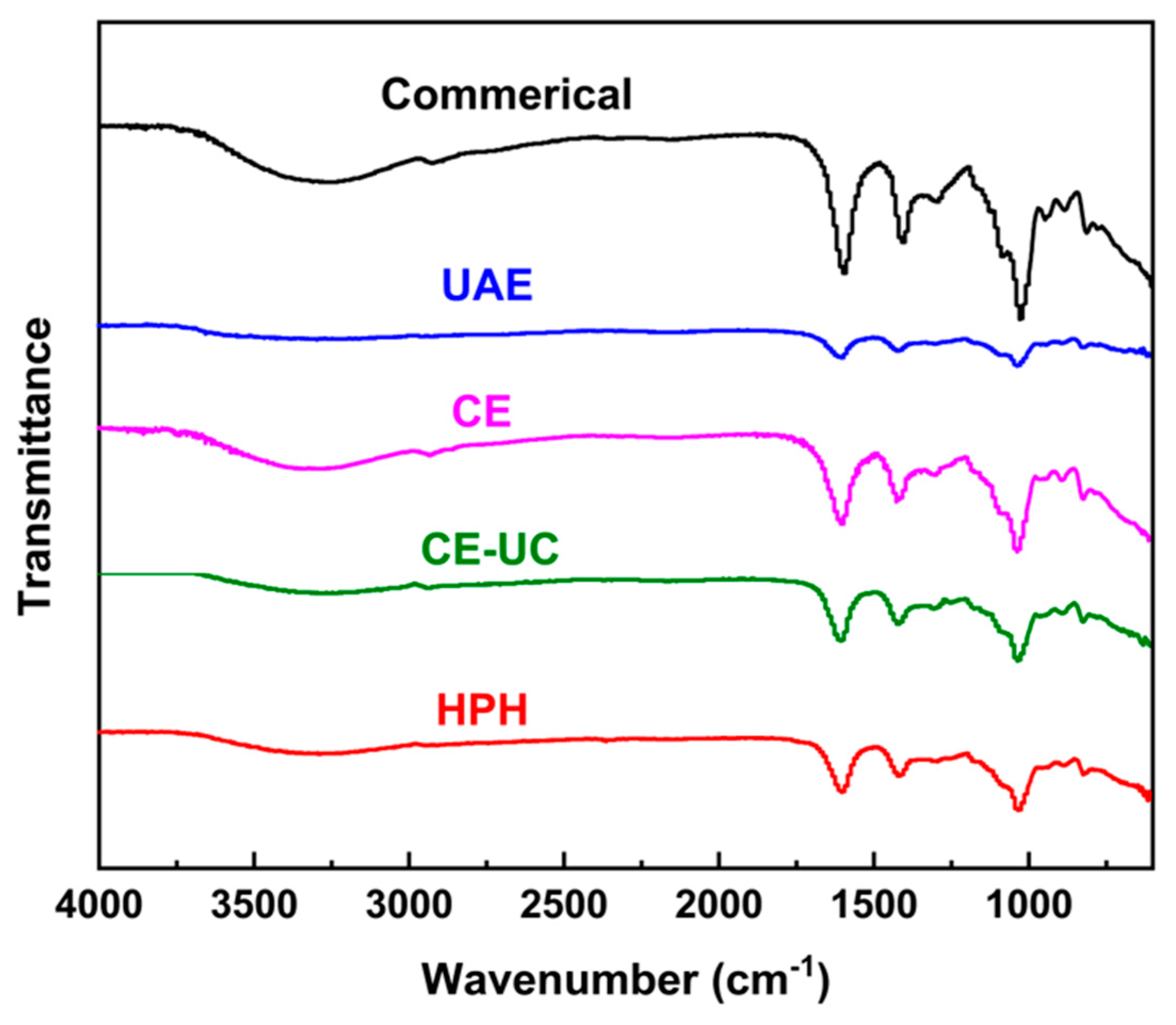

3.4. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum analysis

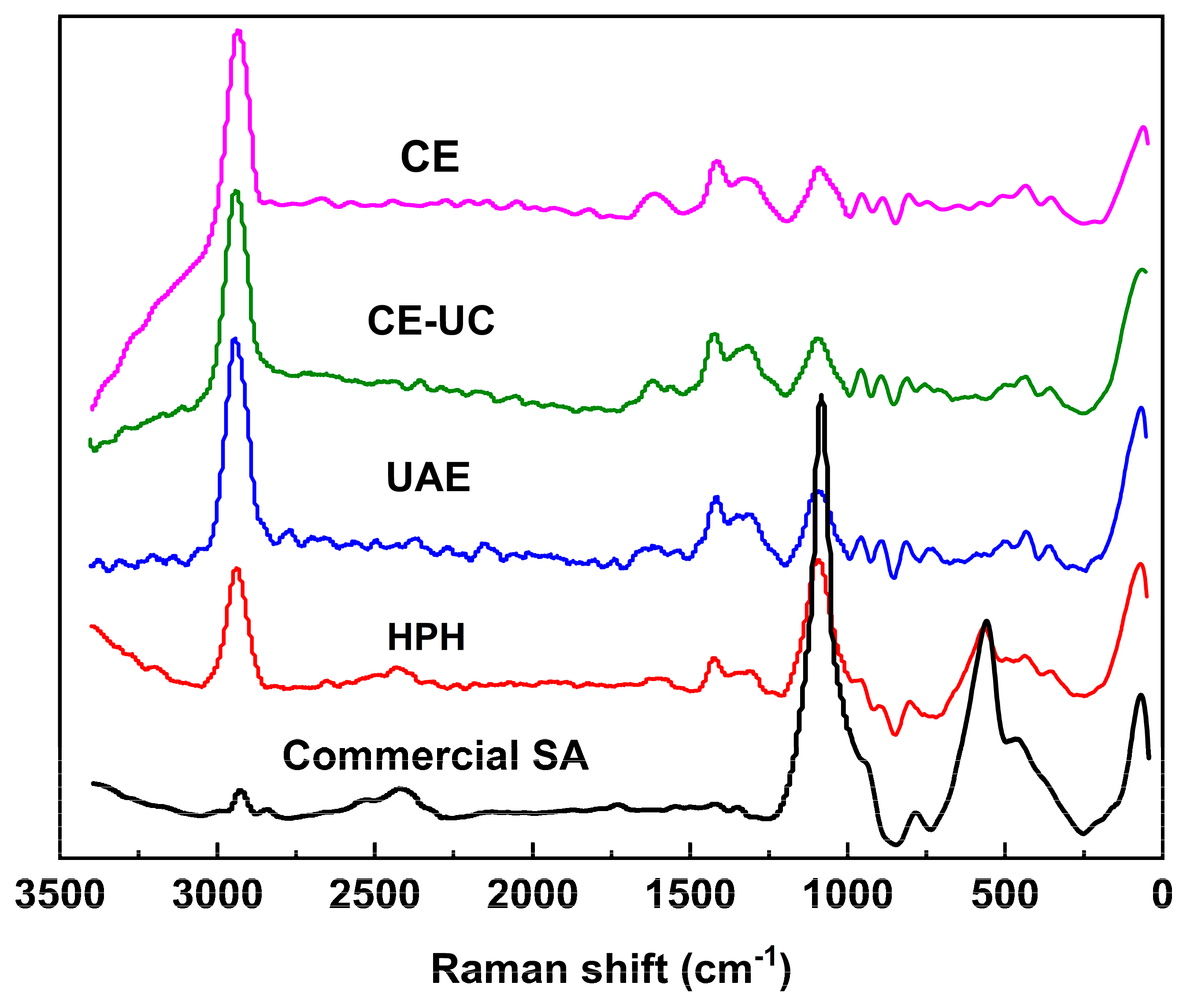

3.5. Microscope raman spectrometer (MRS) analysis

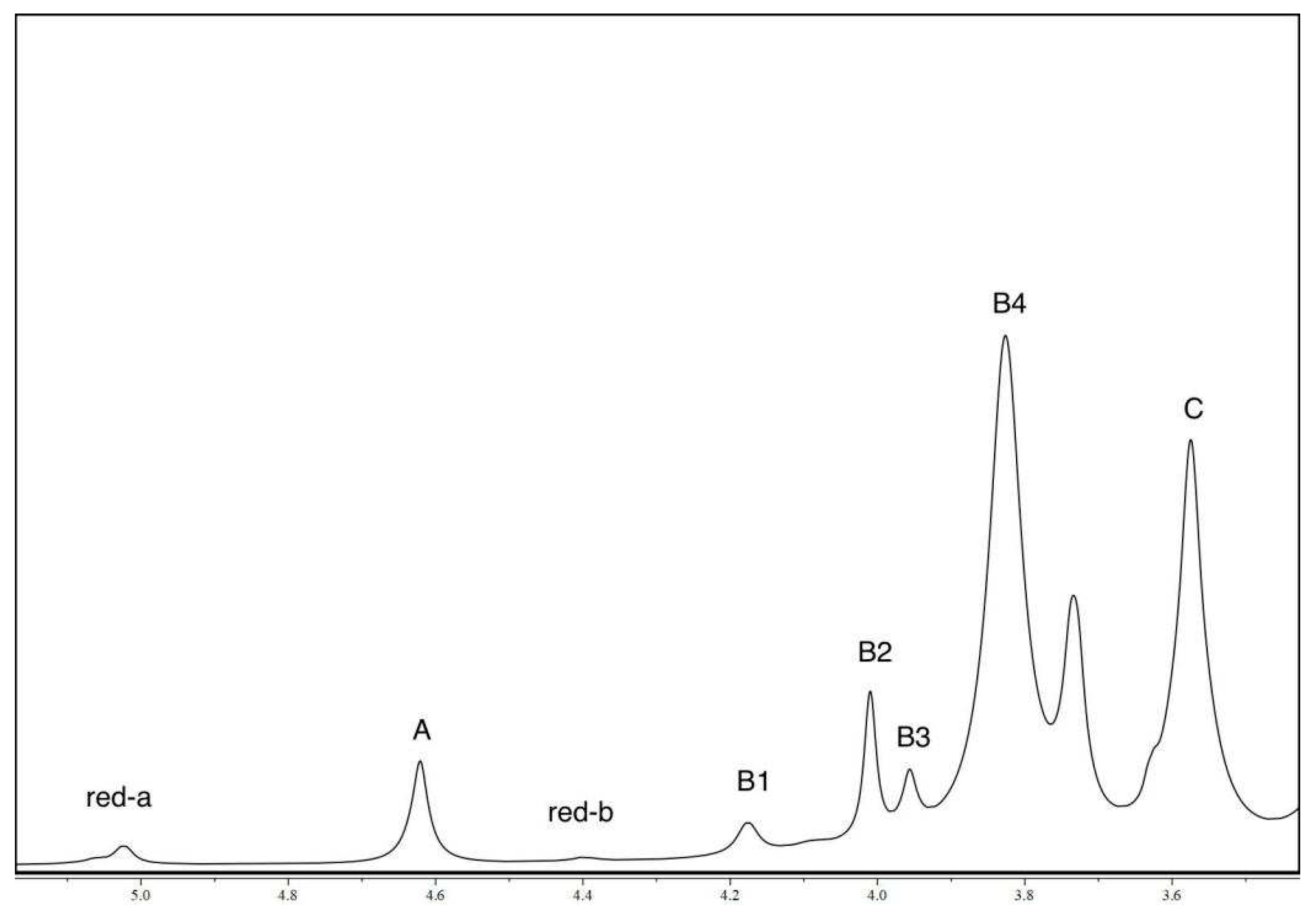

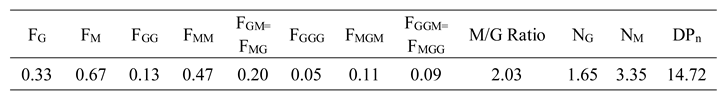

3.6. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis

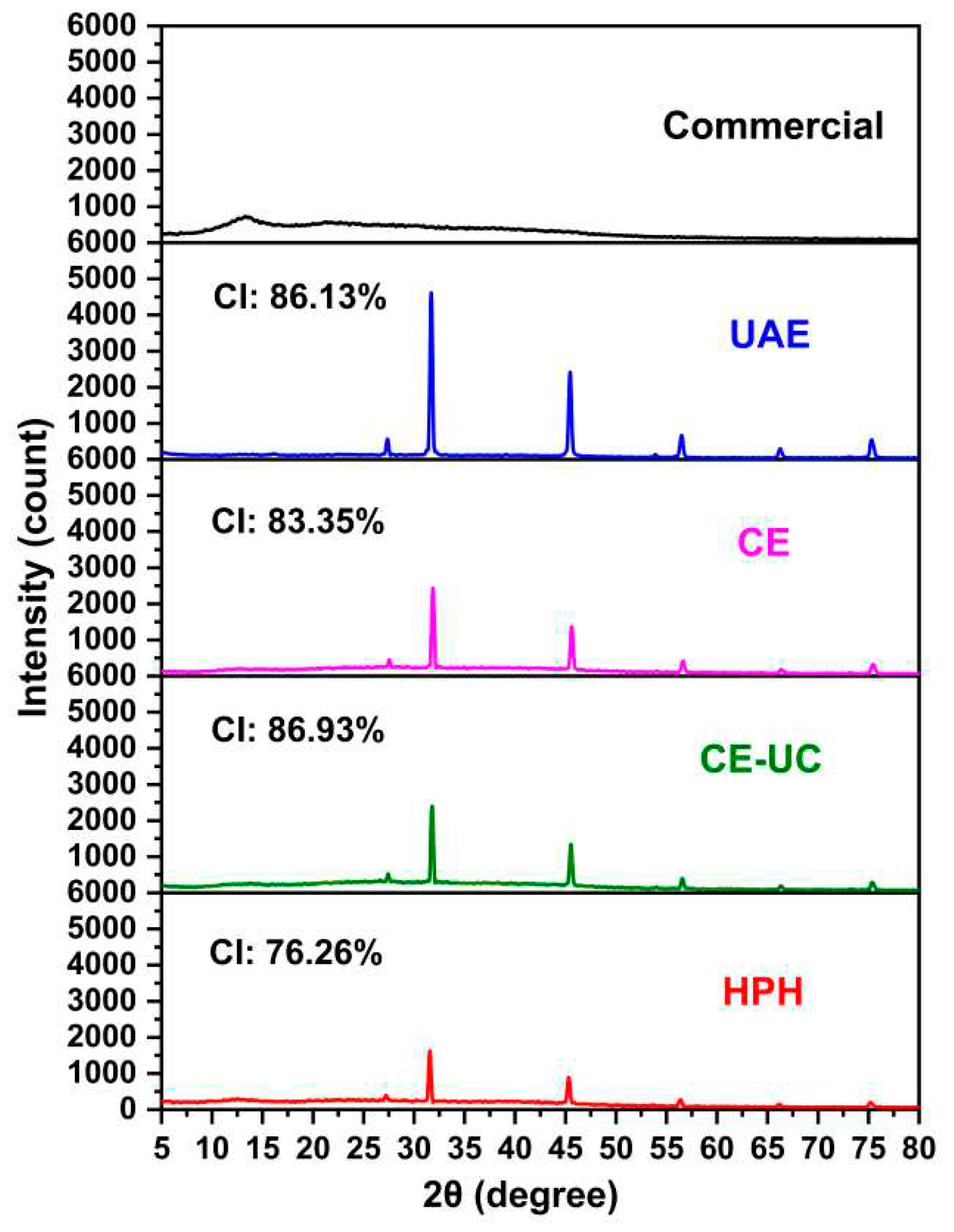

3.7. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis

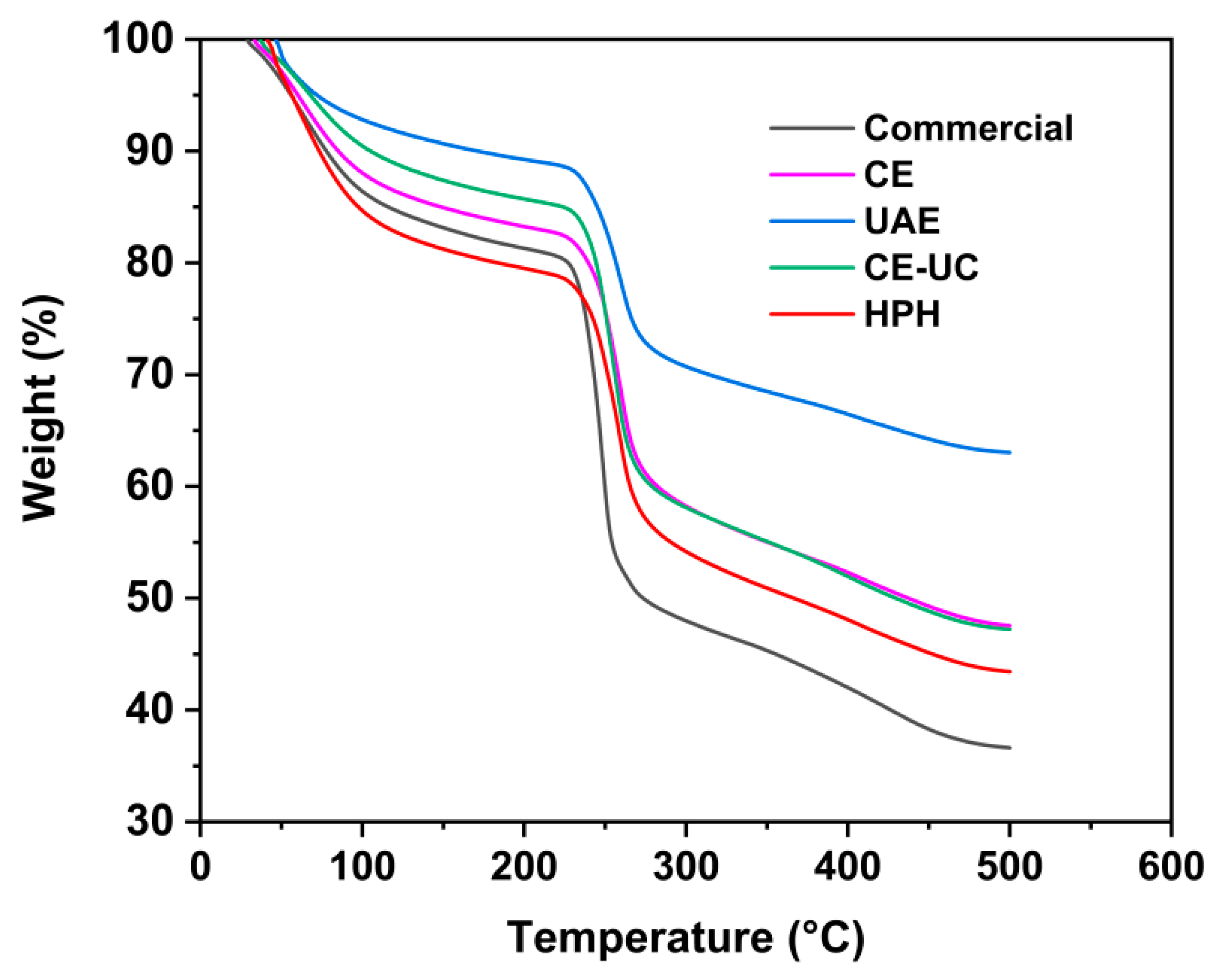

3.8. Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) analysis

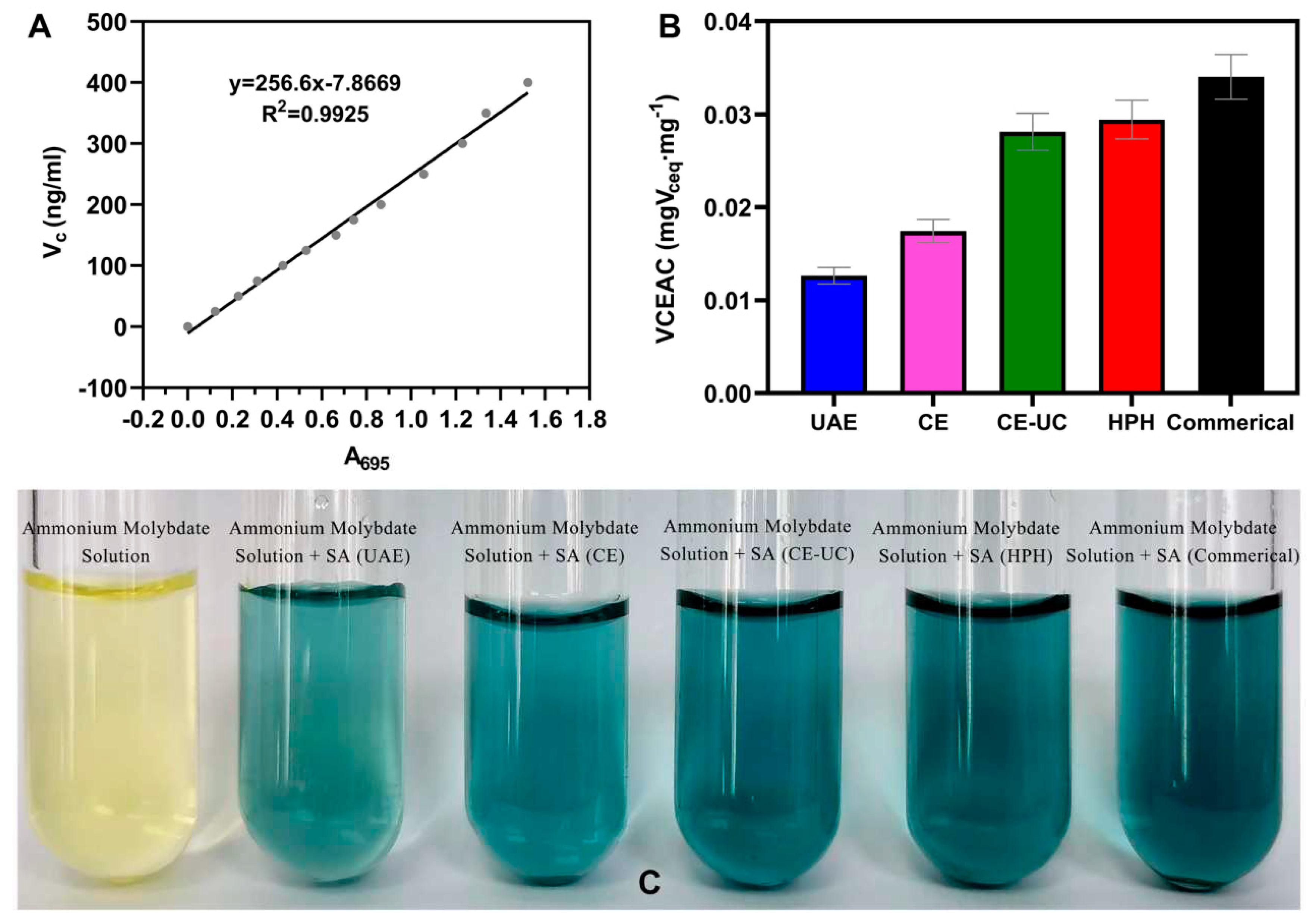

3.8. Total antioxidant capacity assay (T-AOC)

4. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interests

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

References

- C. Sun, J. Zhou, G. Duan, and X. Yu, “Hydrolyzing Laminaria japonica with a combination of microbial alginate lyase and cellulase,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 311, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Roesijadi, S. B. Jones, L. J. Snowden-Swan, and Y. Zhu, “Macroalgae as a Biomass Feedstock: A Preliminary Analysis (PNNL-19944),” 2010.

- X. Yang, H. Sui, H. Liang, J. Li, and B. Li, “Effects of M/G Ratios of Sodium Alginate on Physicochemical Stability and Calcium Release Behavior of Pickering Emulsion Stabilized by Calcium Carbonate,” Front Nutr, vol. 8, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. G. Gómez-Mascaraque, M. Martínez-Sanz, S. A. Hogan, A. López-Rubio, and A. Brodkorb, “Nano- and microstructural evolution of alginate beads in simulated gastrointestinal fluids. Impact of M/G ratio, molecular weight and pH,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 223, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Fourest and B. Volesky, “Alginate Properties and Heavy Metal Biosorption by Marine Algae,” 1997.

- D. J. McHugh, Production and utilization of products from commercial seaweeds, vol. 288. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1987.

- Inc. Grand View Research, “Alginate Market Size Worth $923.8 Million by 2025 | CAGR: 4.5%: Grand View Research, Inc.,” Dec. 11, 2017. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/alginate-market-size-worth-9238-million-by-2025--cagr-45-grand-view-research-inc-663335343.html (accessed Sep. 25, 2022).

- S. A. Ghumman et al., “Formulation and evaluation of quince seeds mucilage – sodium alginate microspheres for sustained delivery of cefixime and its toxicological studies,” Arabian Journal of Chemistry, vol. 15, no. 6, p. 103811, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Song et al., “Preparation and characterization of multi-network hydrogels based on sodium alginate/krill protein/polyacrylamide—Strength, shape memory, conductivity and biocompatibility,” Int J Biol Macromol, vol. 207, pp. 140–151, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Gong, G. T. Han, Y. M. Zhang, J. F. Zhang, W. Jiang, and Y. Pan, “Research on the degradation performance of the lotus nanofibers-alginate porous materials,” Polym Degrad Stab, vol. 118, pp. 104–110, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhong et al., “Fabrication and characterization of oil-in-water emulsions stabilized by macadamia protein isolate/chitosan hydrochloride composite polymers,” Food Hydrocoll, vol. 103, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Luo, A. Guo, Y. Zhao, and X. Sun, “A high strength, low friction, and biocompatible hydrogel from PVA, chitosan and sodium alginate for articular cartilage,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 286, p. 119268, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Alzarea et al., “Development and Characterization of Gentamicin-Loaded Arabinoxylan-Sodium Alginate Films as Antibacterial Wound Dressing,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 23, no. 5, p. 2899, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang et al., “The promoting effects of alginate oligosaccharides on root development in Oryza sativa L. mediated by auxin signaling,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 113, pp. 446–454, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Papageorgiou, E. P. Kouvelos, and F. K. Katsaros, “Calcium alginate beads from Laminaria digitata for the removal of Cu+2 and Cd+2 from dilute aqueous metal solutions,” Desalination, vol. 224, no. 1–3, pp. 293–306, Apr. 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Kirdponpattara and M. Phisalaphong, “Bacterial cellulose-alginate composite sponge as a yeast cell carrier for ethanol production,” Biochem Eng J, vol. 77, pp. 103–109, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sasaki, T. Takagi, K. Motone, T. Shibata, K. Kuroda, and M. Ueda, “Direct bioethanol production from brown macroalgae by co-culture of two engineered saccharomyces cerevisiae strains,” Biosci Biotechnol Biochem, vol. 82, no. 8, pp. 1459–1462, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. J. McHugh, “A guide to the seaweed industry.,” FAO Fisheries Technical Paper , vol. 441, 2003.

- T. A. Fenoradosoa et al., “Extraction and characterization of an alginate from the brown seaweed Sargassum turbinarioides Grunow,” J Appl Phycol, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 131–137, Apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Chee, P. K. Wong, and C. L. Wong, “Extraction and characterisation of alginate from brown seaweeds (Fucales, Phaeophyceae) collected from Port Dickson, Peninsular Malaysia,” J Appl Phycol, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 191–196, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Fertah, A. Belfkira, E. montassir Dahmane, M. Taourirte, and F. Brouillette, “Extraction and characterization of sodium alginate from Moroccan Laminaria digitata brown seaweed,” Arabian Journal of Chemistry, vol. 10, pp. S3707–S3714, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. G. Gomez, M. v. Pérez Lambrecht, J. E. Lozano, M. Rinaudo, and M. A. Villar, “Influence of the extraction-purification conditions on final properties of alginates obtained from brown algae (Macrocystis pyrifera),” Int J Biol Macromol, vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 365–371, May 2009. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Khajouei et al., “Extraction and characterization of an alginate from the Iranian brown seaweed Nizimuddinia zanardini,” Int J Biol Macromol, vol. 118, pp. 1073–1081, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, X. Zhou, and J. Zhang, “Optimization of enzyme assisted extraction of polysaccharides from Astragalus membranaceus,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 111, pp. 567–575, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu et al., “Optimization of enzyme-assisted extraction and characterization of polysaccharides from Hericium erinaceus,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 101, no. 1, pp. 606–613, 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. Ren, C. Chen, C. Li, X. Fu, L. You, and R. H. Liu, “Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction of Sargassum thunbergii polysaccharides and its antioxidant and hypoglycemic activities,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 173, pp. 192–201, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Montes, M. Gisbert, I. Hinojosa, J. Sineiro, and R. Moreira, “Impact of drying on the sodium alginate obtained after polyphenols ultrasound-assisted extraction from Ascophyllum nodosum seaweeds,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 272, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Du, L. J. Zheng, and Q. Wei, “Screening and identification of Providencia rettgeri for brown alga degradation and anion sodium alginate/poly (vinyl alcohol)/tourmaline fiber preparation,” Journal of the Textile Institute, vol. 106, no. 7, pp. 787–791, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jin, L. Li, Q. Liu, and N. AI, “Optimization of Extraction Process of Sodium Alginate from Laminaria japonica by Ultrasonic-Complex Enzymatic Hydrolysis,” Science and Technology of Food Idustry, vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 132–137, 2021.

- Y. Lei, B. Du, Y. Qian, F. Ye, and L. Zheng, “Sodium alginate extraction by enzyme-ultrasonic combined method,” in Advanced Materials Research, 2012, pp. 2326–2329. [CrossRef]

- Q. Li, Y. Zeng, L. Wang, H. Guan, C. Li, and L. Zhang, “The heparin-like activities of negatively charged derivatives of low-molecular-weight polymannuronate and polyguluronate,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 155, pp. 313–320, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu, L. Wu, Y. Chen, H. Ni, A. Xiao, and H. Cai, “Characterization of an extracellular biofunctional alginate lyase from marine Microbulbifer sp. ALW1 and antioxidant activity of enzymatic hydrolysates,” Microbiol Res, vol. 182, pp. 49–58, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen et al., “Alginate oligosaccharide DP5 exhibits antitumor effects in osteosarcoma patients following surgery,” Front Pharmacol, vol. 8, no. SEP, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. Fang et al., “Identification and activation of TLR4-mediated signalling pathways by alginate-derived guluronate oligosaccharide in RAW264.7 macrophages,” Sci Rep, vol. 7, no. 1, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Zhu and H. Yin, “Alginate lyase: Review of major sources and classification, properties, structure-function analysis and applications,” Bioengineered, vol. 6, no. 3. Taylor and Francis Inc., pp. 125–131, 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. Levy, Z. Okun, M. Davidovich-Pinhas, and A. Shpigelman, “Utilization of high-pressure homogenization of potato protein isolate for the production of dairy-free yogurt-like fermented product,” Food Hydrocoll, vol. 113, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Lenhart, J. Quodbach, and P. Kleinebudde, “Fibrillated Cellulose via High Pressure Homogenization: Analysis and Application for Orodispersible Films,” AAPS PharmSciTech, vol. 21, no. 1, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Wu et al., “Preparation and characterization of okara nanocellulose fabricated using sonication or high-pressure homogenization treatments,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 255, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Magpusao, S. Giteru, I. Oey, and B. Kebede, “Effect of high pressure homogenization on microstructural and rheological properties of A. platensis, Isochrysis, Nannochloropsis and Tetraselmis species,” Algal Res, vol. 56, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Hahn, S. Kelly, K. Muffl, N. Tippk, and R. Ulber, Extraction of Lignocellulose and Algae for the Production of Bulk and Fine Chemicals. 2011.

- P. Prieto, M. Pineda, and M. Aguilar, “Spectrophotometric Quantitation of Antioxidant Capacity through the Formation of a Phosphomolybdenum Complex: Specific Application to the Determination of Vitamin E 1,” 1999. [Online]. Available: http://www.idealibrary.comon.

- M. P. Rahelivao, H. Andriamanantoanina, A. Heyraud, and M. Rinaudo, “Structure and properties of three alginates from madagascar seacoast algae,” Food Hydrocoll, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 143–146, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Mohammed et al., “Multistage extraction and purification of waste Sargassum natans to produce sodium alginate: An optimization approach,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 198, pp. 109–118, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Costa, A. M. Marques, L. M. Pastrana, J. A. Teixeira, S. M. Sillankorva, and M. A. Cerqueira, “Physicochemical properties of alginate-based films: Effect of ionic crosslinking and mannuronic and guluronic acid ratio,” Food Hydrocoll, vol. 81, pp. 442–448, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Campos-Vallette et al., “Characterization of sodium alginate and its block fractions by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy,” Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, vol. 41, no. 7, pp. 758–763, Jul. 2010. [CrossRef]

- H. Grasdalen, “Note High-field, ’H-n.m.r. spectroscopy of alginate: sequential structure and linkage conformations,” 1983.

- C. H. Goh, P. W. S. Heng, and L. W. Chan, “Alginates as a useful natural polymer for microencapsulation and therapeutic applications,” Carbohydrate Polymers, vol. 88, no. 1. pp. 1–12, Mar. 17, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Penman and G. R. Sanderson, “A method for the determination of uronic acid sequence in alginates,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 273–282, 1972. [CrossRef]

- Z. Guo et al., “Fabrication of efficient alginate composite beads embedded with N-doped carbon dots and their application for enhanced rare earth elements adsorption from aqueous solutions,” J Colloid Interface Sci, vol. 562, pp. 224–234, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y.-X. Feng and B.-G. Li, “Preparation and adsorption properties of novel Fe 3 O 4 @SA/La gel composite microspheres”. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, H. Zhang, X. Wang, J. Ma, L. Lian, and D. Lou, “Preparation and Flocculation Performance of Polysilicate Aluminum-Cationic Starch Composite Flocculant,” Water Air Soil Pollut, vol. 231, no. 7, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).