1. Introduction

Diamond circular saw blades are used for cutting natural stone and ceramics. The cutting segments of diamond tools consists of synthetic diamonds embedded in a metallic matrix. The segments are manufactured by powder metallurgy technology Several metals can be used as matrices in metallic-diamond composites: cobalt, copper, iron, tin, and nickel [

1,

2]. However, cobalt is the base metal for the production of metallic-diamond segments.

Recently, the use of inexpensive premixed and milled powders in ball mills, which may replace cobalt powders, has been observed [

3,

4]. Diamond blades based on metal matrices containing iron, copper, nickel and tin have appropriate mechanical properties, relatively low sintering temperature, and not expensive cost of materials [

5,

6].

Based on previous research [

2], the iron-based material was designed for the matrix of metallic diamond tools. The material was obtained from elemental powders subjected to milling for 30 h, 60 h and 120 h. The material selected for testing has the following composition: 60% Fe, 23.8% Cu, 4.2% Sn, and 12% Ni.

The proposed matrix material had a porosity not exceeding 3% and mechanical properties could replacement of cobalt-based sinters metallic-diamond segments. The important role of a matrix in metallic-diamond composites is to hold firmly diamond particles on the working surface.. So that the matrix material must have a thermal expansion coefficient significantly greater than that of the diamond. The property ensures a good retention of the diamond particles on the working surface. In addition, the matrix material should have appropriate elastic and plastic properties [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

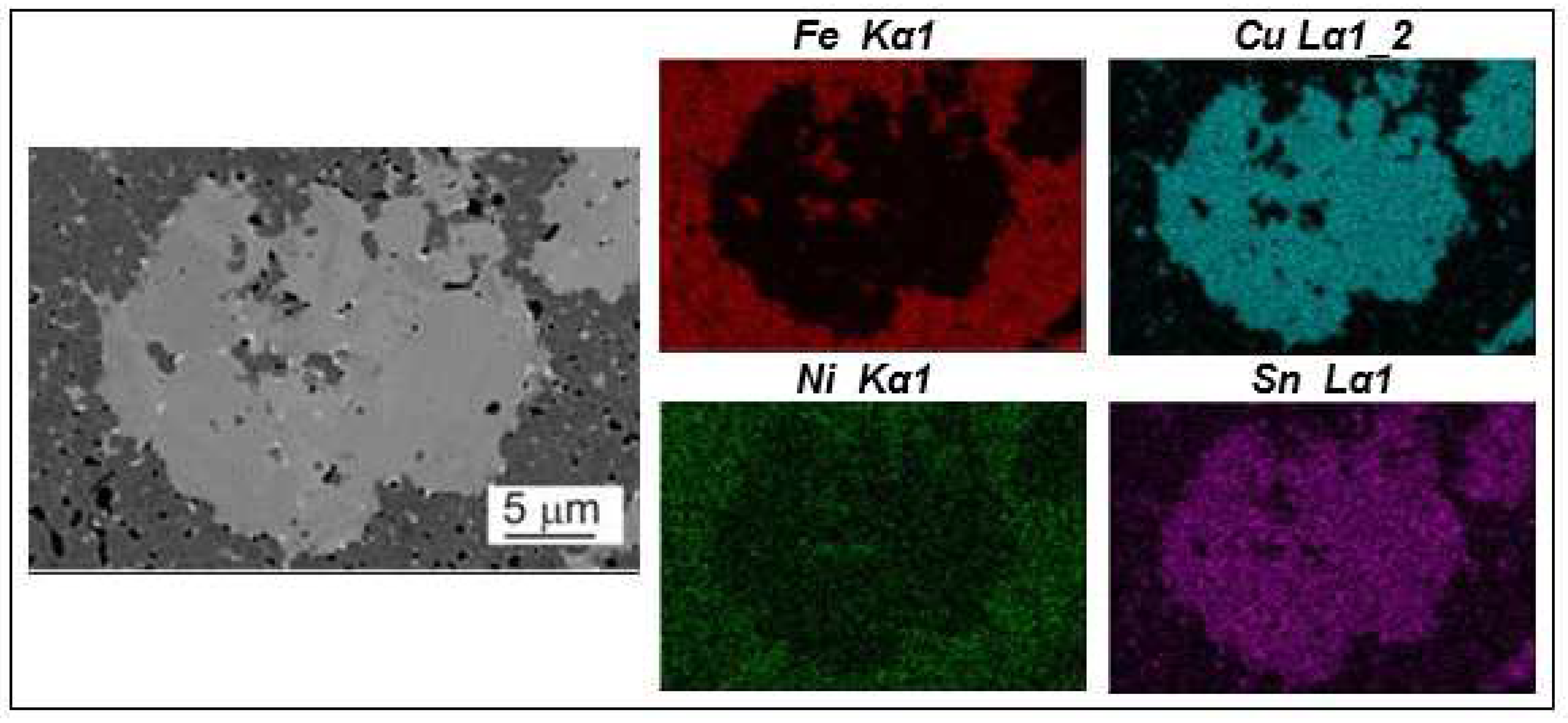

The FeCuSnNi sinter revealed a complex phase structure. Point chemical analysis showed the presence of Fe solution, Cu solution and iron oxides. The nickel atoms were distributed throughout the entire sinter volume. The oxides concentrated in the region of the iron solution Nickel atoms are similar in size to iron atoms, so they diffuse easily into the lattice of atoms in the iron-rich region. The microstructures of sinters obtained from powder mixtures after milling for 30 h show some characteristic features. There is a banding and lamellar shape which is due to the flake shape of the powder particles [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

The tin bronze (23.8% Cu, 4.2% Sn) addition to Fe and Ni powders resulted in obtaining a liquid phase during the hot pressing process which helped to consolidate the phase components. The obtained results indicate that the produced sinters are characterized by a sufficiently high hardness and appropriate mechanical parameters. The matrix material had mechanical properties that would allow to replace cobalt-based sinters [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and sintering

The powder mixtures for the sintering were made from the powders:

iron powder with a size in the range 20-180 μm,

bronze tin powder containing 15% (by mass.) tin, with a particle size below 45 μm,

nickel powder with average size = 2.4 μm.

The mass fractions of the powder mixture for obtaining the FeCuSnNi material were: 60% Fe, 28% bronze and 12% Ni. these proportions of powders meant the following chemical composition: 60% Fe, 23.8% Cu, 4.2% Sn, 12% Ni.

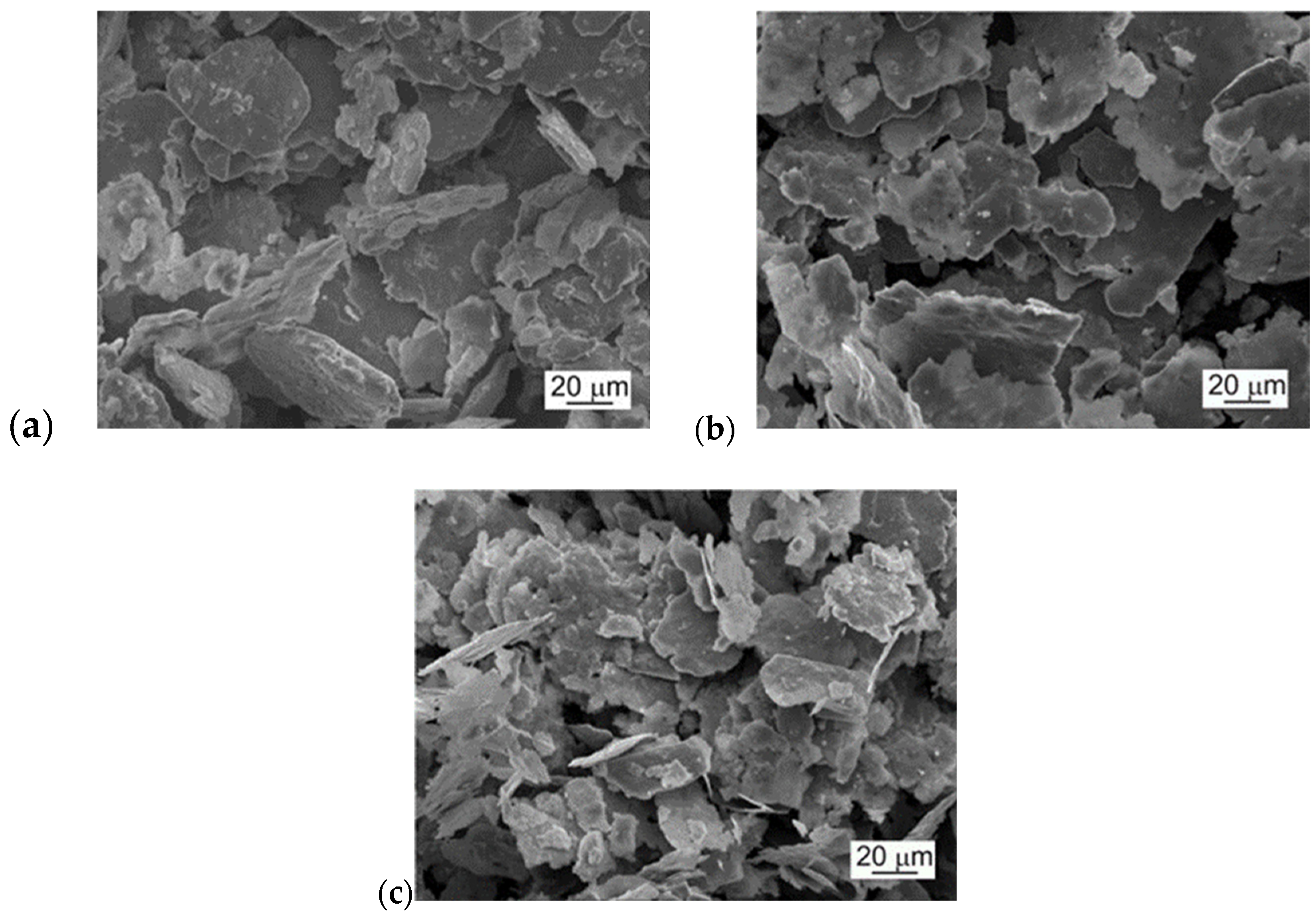

The powders were premixed in a Turbula mixer for 30 minutes. Then, the resulting powder mixture was milling in an EnviSense RJM-102 laboratory ball mill in ethyl alcohol with a small addition of glycerol. The milling vessel was filled with 100Cr6 steel balls which had a diameter of 12 mm. The vessel was half full. The milling time was 30 h, 60 h and 120 h. The shape and particle size of the powders after the milling process are shown in the

Figure 1.

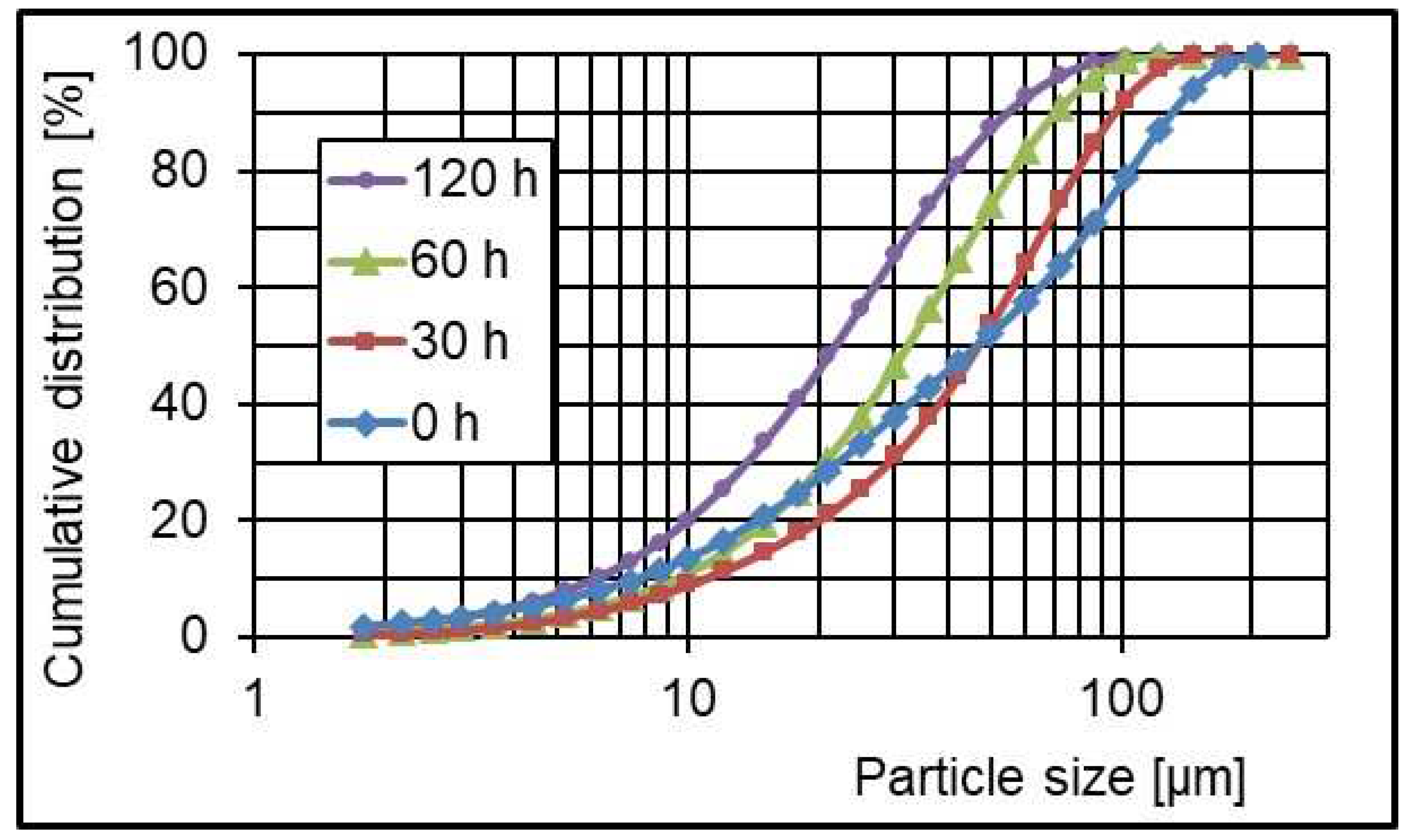

The granulometric analysis using the laser diffraction method was carried out. The particle size distribution of the powder was determined by the particle size which corresponds to the volume distribution of the particle [

7,

8,

25,

26]. The graphical representation of the particle size distribution for the FeCuSnNi material is presented in the form of a cumulative distribution (

Figure 2).

The granulometric analysis using the laser diffraction method was carried out on a HELOS (H2769) & RODOS laser analyzer with WINDOX 5 software, enabling the measurement of particle sizes in the range 0.1 μm-2000 μm. The test was carried out for powder mixtures for all milling times as well as for mixtures without milling (

Figure 2).

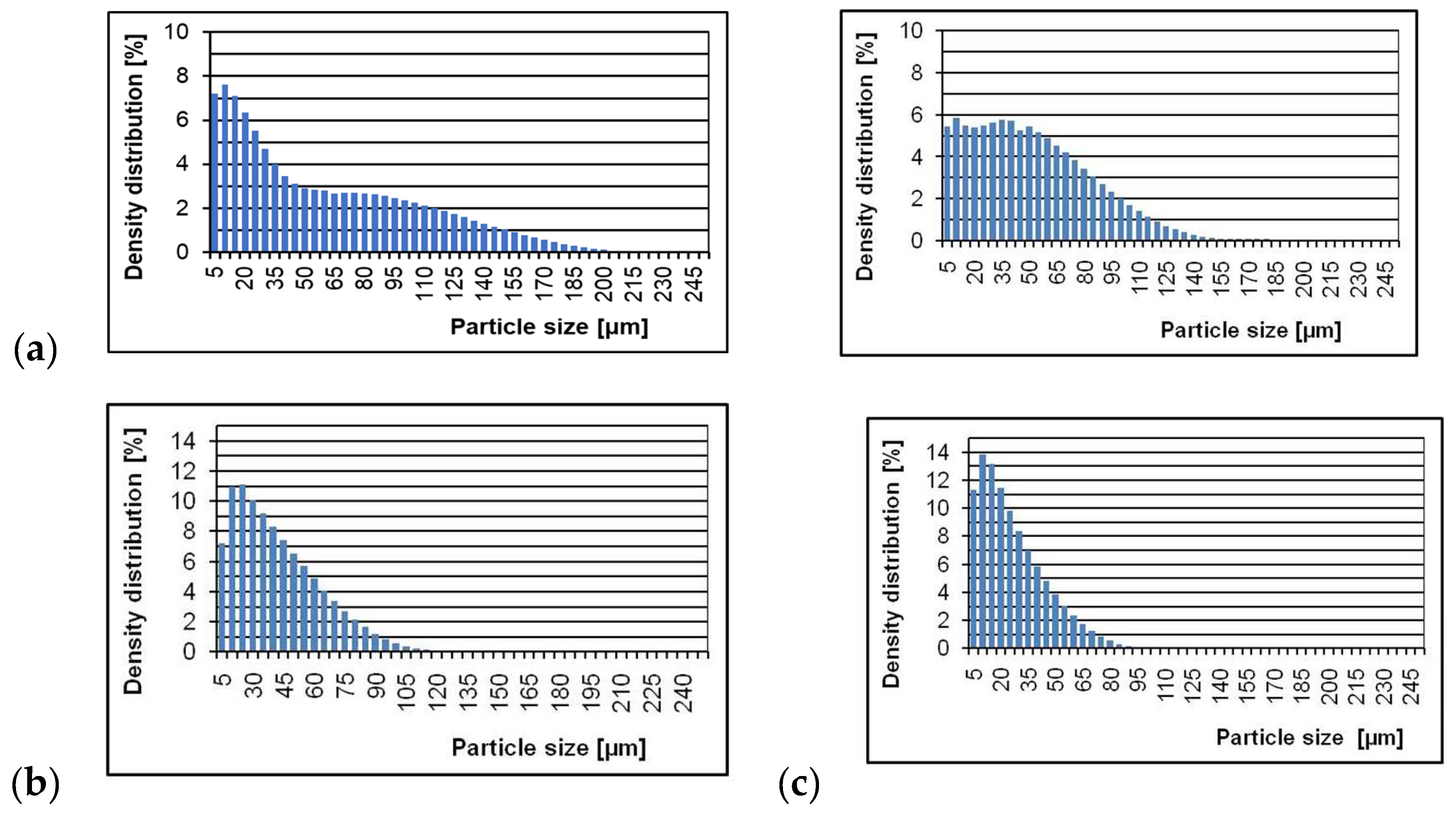

From the cumulative distributions, the particle size density distributions were determine in the form of histograms on a linear scale (

Figure 3). Subsequent graphs show a shift of the center of gravity towards smaller particle sizes. Figure a shows a poorly marked bimodal character on the graph for the 30h milling, revealing the basic composition of the powder mix: iron and bronze. The graphs are unimodal for longer milling times.

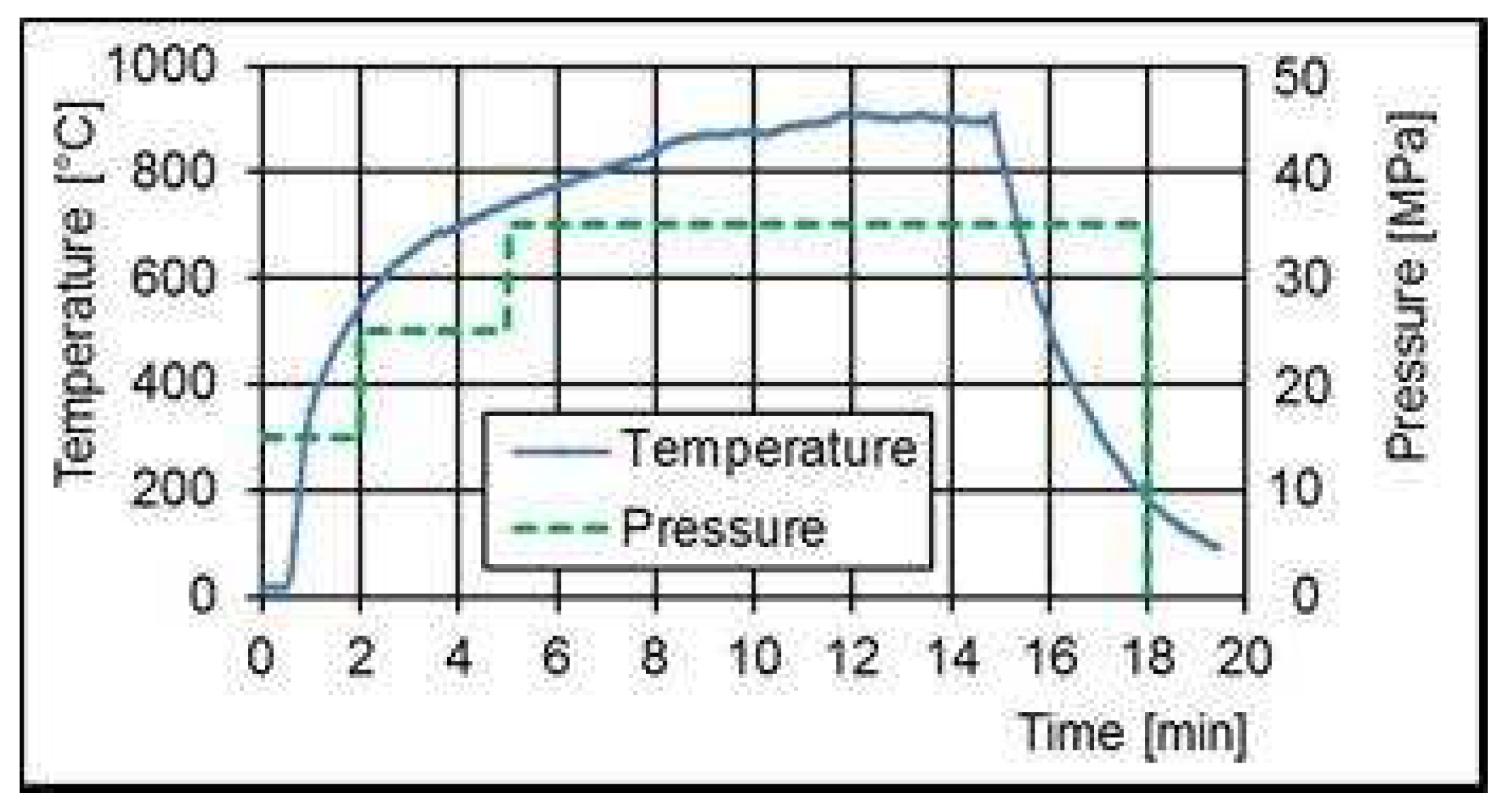

The powder consolidation process was carried out by hot pressing in nitrogen atmosphere using the Idea (Italy) Unidiamond press oven. The powder mixtures were pressed in a graphite mold, which enables formation of specimens with dimensions of 7 x 6 x 40 mm. The powder mixtures were kept at the temperature of 900 °C and the pressure of 25 MPa for 3 minutes. The diagram of the temperature changes and the pressure changes during the hot pressing process for the powder mixtures after the milling time 60 h is shown in

Figure 4. The hot pressing process was identical for the powder mixtures after 30 h and 120 h milling times.

2.2. Measurements of physical properties

Measurement of sinter density were carried out by weighing method using a WPA120 hydrostatic balance.The oxygen content was obtained by burning samples weighing ~ 2g using the LECO CS-125 device. The hardness of the sinters was measured by the Vickers method on the Innovatest Nexus 4000 hardness tester, using a 98.1 N load. For each sample, ten measurements of each physical quantity were made. The result was calculated as the arithmetic mean of 10 measurements.

2.3. Tensile test

The static tensile test was carried out with the use of a universal testing machine type UTS-100 with data recording system by Zwick. The Young's modulus and Poisson ratio were measured using the ultrasonic method using a Panametrics Epoch III flaw detector.

2.4. Dilatometric test

Dilatometric tests were carried out using a high-temperature Netzsch DIL-402-E dilatometer. The dimensions of the samples were 15 mm x 5 mm x 5 mm. Relative changes in the length of the samples were recorded during their heating to 950°C in an argon atmosphere. Measurements were carried out for samples made of FeCuSnNi powders after milling time of 60 h.

2.5. Microstructure studies

Observations of the microstructure of the produced sinters were carried out using the JSM-7100F scanning electron microscope, integrated with the EDS X-Max-AZtec X-ray microanalysis system by OXFORD INSTRUMENTS. The research was carried out using a backscattered electron detector.

3. Results

3.1. Measurement of density, porosity, hardness, and degree of oxidation

Density, porosity, hardness and oxygen content were measured for all tested sinters. All results were determined and are presented in

Table 1.

The theoretical density dT was determined assuming the following densities of the elements included in the sinters: Fe - 7.80 g / cm3, Cu - 8.92 g / cm3, Ni - 8.90 g / cm3, Sn - 6.52 g / cm3. The porosity of the sinters was estimated as the relative difference between the theoretical density dT and the actual density determined by d

Along with the increase in milling time, an increase in the degree of oxidation of the powders was observed, which contributed to the reduction of the sinter density for 120 h milling time. The sinters are characterized by a much higher hardness, which is probably due to the fine-grained microstructure and strengthening with the oxide phase. The hardness of FeCuSnNi sinters varies and has a maximum in hardness after milling 60 h (

Table 1).

3.2. Static Tensile Test

From the data of the static tensile test (

Figure 5), the following parameters were calculated: yield strength Rp0.2, tensile strength Rm and maximum relative elongation ε. The flat samples with a length of 40 mm and a thickness of 6.5 mm were used. The measurement zone was 20 mm long and 11.3 mm wide. The parameters of the static tensile test were calculated as the arithmetic mean of three tests.The elastic parameters were measured using the ultrasonic method. The modulus of elasticity and the Poisson number were determined for a single sinter (powders after milling 60 h). The mechanical properties are listed in

Table 2.

The strength properties given in

Table 2, for all milling timesi, have satisfactory values. The best properties are characterized by sinters made of powders after milling time of 60 h.

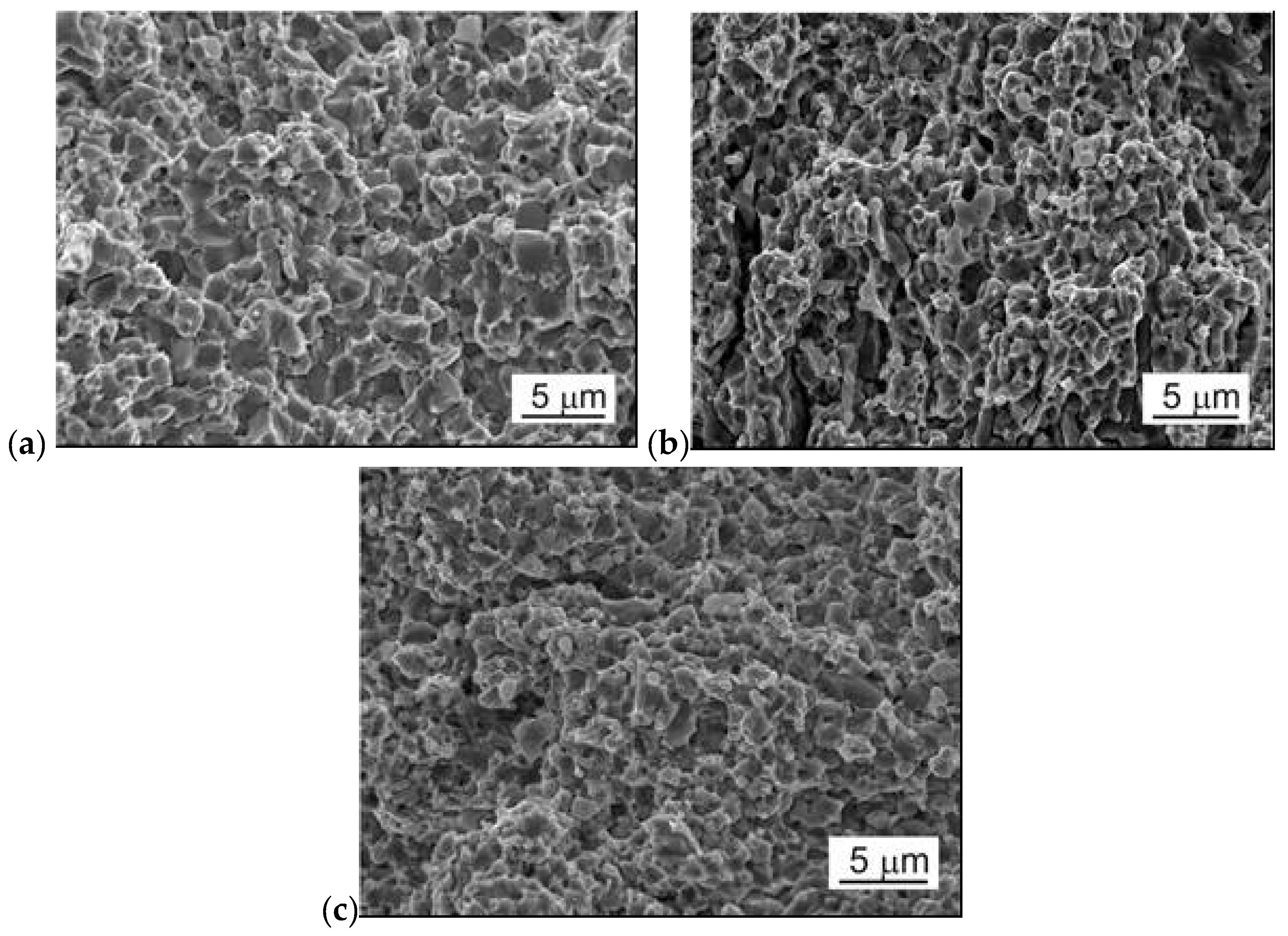

3.3. Fractographic studies of fractures

Fractographic tests were carried out on fractures obtained in the tensile test (

Figure 6). The fractography fractures is mixed. Fractures assume a ductile form almost over the entire surface, only in some places there are visible areas showing the characteristics of intercrystalline fracture. The topography of this surface consists of a collection of holes of various sizes and shapes. Inside the wells, fine precipitates of iron oxides can be observed.

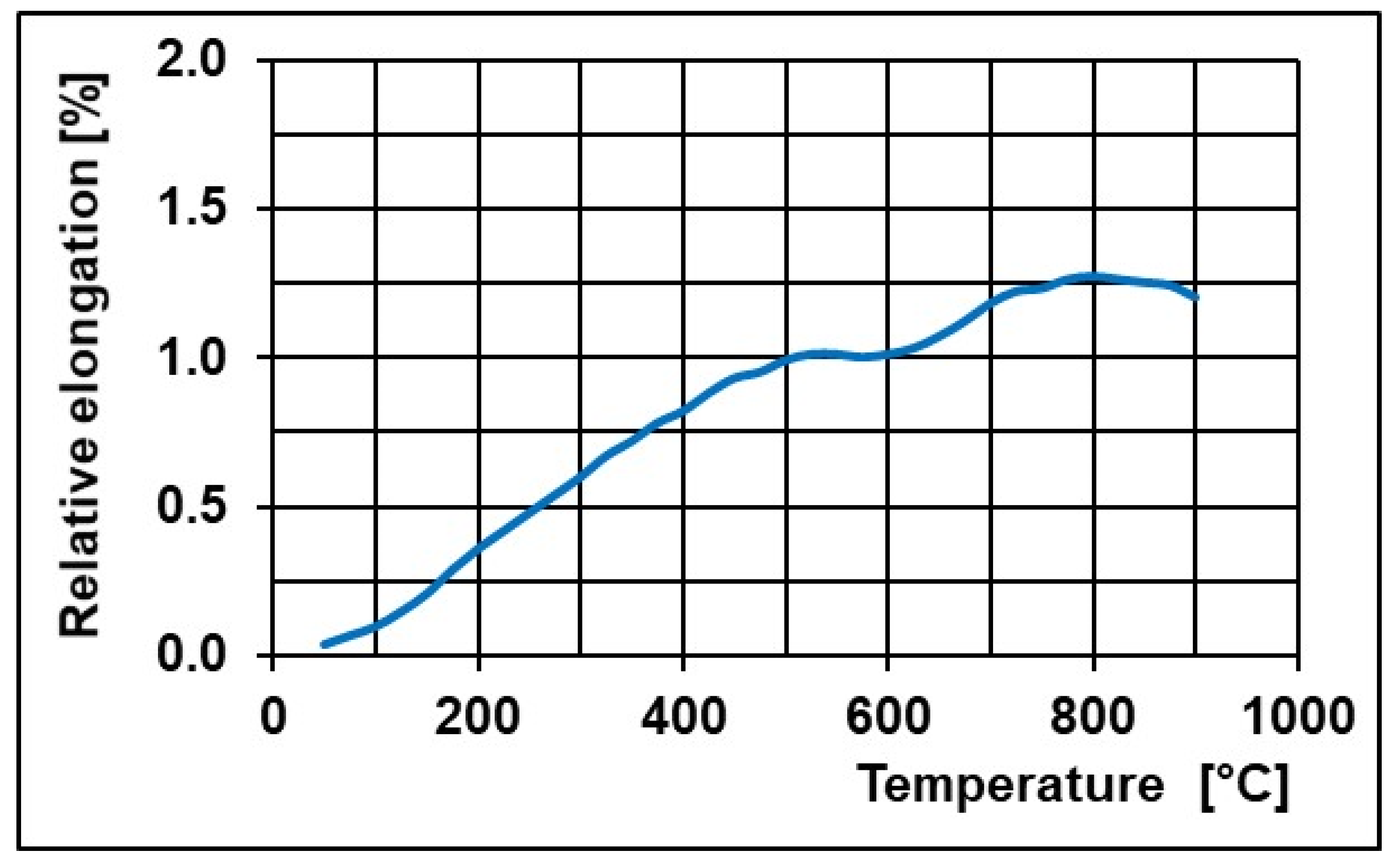

3.4. Dilatometric tests

The dilatometric tests was carried out for sample made of the FeCuSnNi sinter after a milling time of 60 h. The dilatometric curve recorded during their heating to 950 °C is shown in

Figure 7.

Above the temperature of 500 °C, the curve shows a clear deviation from linearity, which proves the phase changes taking place. Taking this into account, the average coefficient of thermal expansion in the range of 20 °C - 500 °C was determined. The average value is 2.05∙10-5 K-1 for the FeCuSnNi material. The value of the coefficient of thermal expansion ensures good retention of diamond particles at working surface of a metallic-diamond tool.

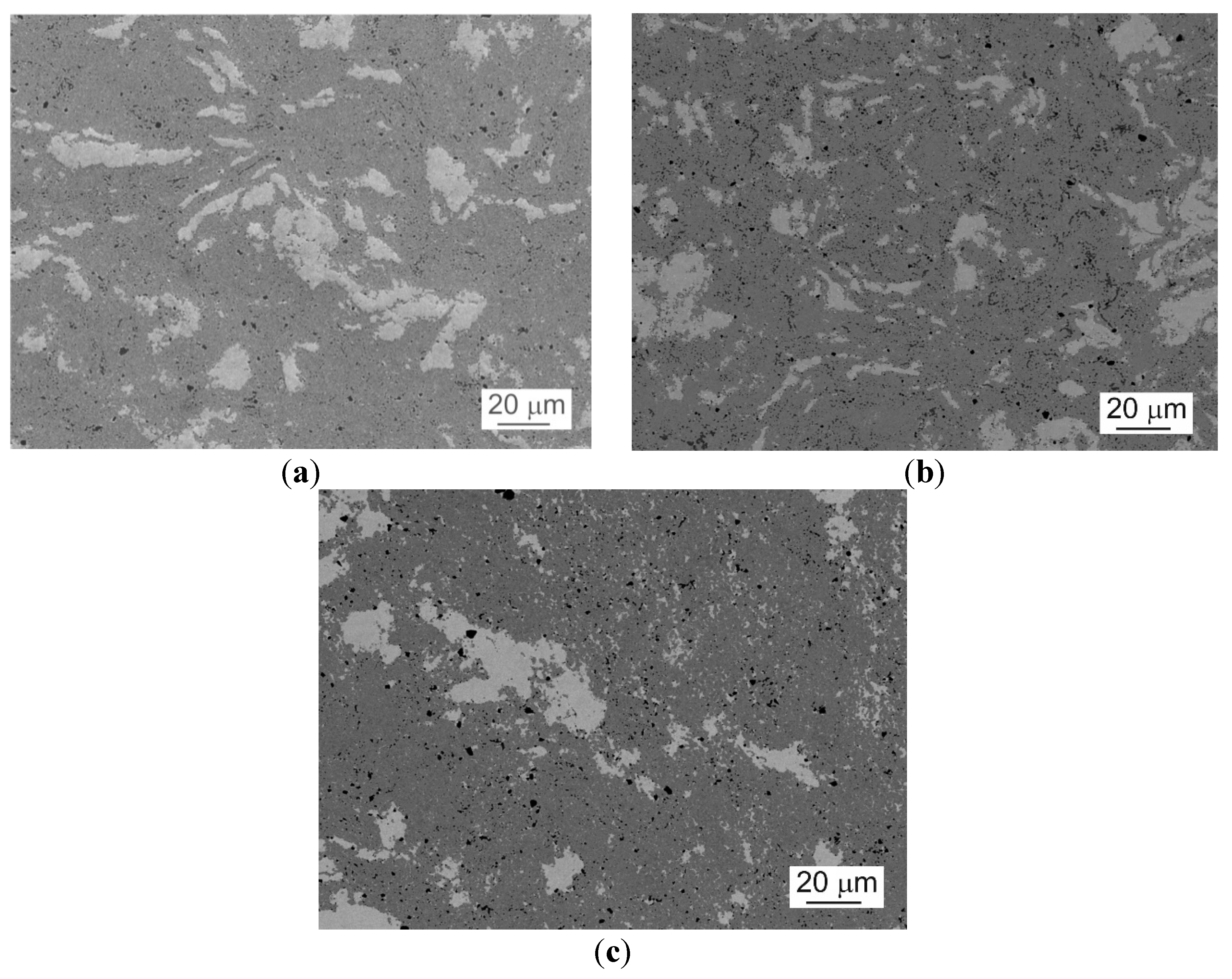

3.5. Microstructure studies

The microstructure of FeCuSnNi sinters after milling is shown at 500x magnification (

Figure 8).

The following figures (

Figure 9) show the microstructure and chemical compositions (expressed in mass %) tested FeCuSnNi sinters, produced from blends of powders subjected to the milling process for 60 h obtained during the EDS analysis. Each chemical composition was determined as the average of at least three points for a given phase.

The surface distribution of elements for the above-mentioned FeCuSnNi sinters is shown in

Figure 9. On the basis of the tests carried out, αFe, γFe, Cu solution and iron oxides were identified in the sinters structure. Nickel atoms are evenly distributed in solutions of iron and copper. Surface distribution of elements for the FeCuSnNi sinter obtained from powder mixtures after milling for 60 h is presented in

Table 3.

Grain refining and reducing the heterogeneity of the chemical composition contributed to the increase in the hardness of the tested sinters. However, the fine-grained microstructure of the sinters obtained from the powder ground for 120 h does not provide them with high tensile strength and plasticity (

Table 1 and

Table 2). This is mainly due to the higher content of oxides, which weaken the strength of grain boundaries, which facilitates brittle fracture of the material.

4. Conclusion

The microstructures of the sinters obtained from the mixtures obtained after milling of 30 and 60 hours show similarities. They are characterized by banding and lamellar character, which results from the flake shape of the powder particles. Extending the milling time of the powder mixture resulted in a decrease in the average particle size and better distribution of nickel.

As a result of the applied consolidation method with such parameters, FeCuNi sinters reached a density of 7.82-8.10 g/cm3, and FeCuSnNi sinters - 7.91-8.01 g/cm3. Density measurements of sinters showed that it is possible to compact the tested powder mixtures by using hot pressing technology to a relative density above 97%. This results from the porosity calculations, which for sinters obtained from powders after grinding for 30 and 60 h does not exceed 3%.

The share of bronze instead of pure copper in the FeCuSnNi sinter gives to a significant increase in tensile strength and had a smaller impact on the yield point (

Table 2). As in the case of hardness, the highest yield strength and tensile strength was achieved by the FeCuSnNi sinter made of powders after milling for 60 h, amounting to 330 MPa and 817 MPa, respectively.

The use of high-energy milling causes a clear milling of powder particles and homogenization of the microstructure, which is accompanied by an increase in hardness, yield point and strength of the sinter. Extending the milling time to 120 h contributed to a significant increase in the degree of oxidation of the material and the brittleness of the agglomerates. The sinters made of powders ground for 120 hours contain over 0.7% oxygen and do not show better strength properties compared to the sinters made of powders subjected to milling for 60 hours. The progressing process of oxidation of the powders could also contribute to the reduction of the sinter density. The material is characterized by a high coefficient of thermal expansion, which ensures good retention of diamond particles in the metallic-diamond composite [

1,

8,

9,

10,

27,

28,

29,

30]. The influence of the mechanical parameters and thermal expansion of the matrix on the retention of diamond particles is currently intensively studied, both experimentally and through computer and mathematical modeling [

11,

12,

13,

31,

32,

33].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.-J.J. and L.J.; methodology, B.-J.J. and L.J.; validation, L.J.;;formal analysis, L.J.; investigation, B.-J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, L.J.; writing—review and editing, L.J.; supervision, B.-J.J.; project administration, B.-J.J.; funding acquisition, B.-J.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Faculty of Mechatronics and Mechanical Engineering, Kielce University of Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Borowiecka-Jamrozek, J. Engineering Structure and Properties of Materials Used as a Matrix in Diamond Impregnated Tools. Archives of Metallurgy and Materials 2013, 58, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowiecka-Jamrozek, J.; Lachowski, J. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Fe-Cu-Ni Sinters Prepared by Ball Milling anf Hot Pressing. Defect and Diffusion Forum 2020, 405, 379–384. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, F.A.C.; Anjinho, C.A. PM materials selection: The Key for Improved Performance of Diamond Tools. Metal Powder Report 2017, 72, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.P.; Bobrovnitchii, G.S.; Skury, A.L.D.; Guimaraes, R.S.; Filgueira, M. Structure, microstructure and mechanical properties of PM Fe–Cu–Co alloys. Mater. Des. 2010, 31, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechnik, V.G.; Bondarenko, M.O.; Kolodnitskyi, V.M.; Zakiev, V.I.; Zakiev, I.M.; Kuzin, M.; Gevorkyan, E.S. Influence of diamond–matrix transition zone structure on mechanical properties and wear of sintered diamond-containing composites based on Fe–Cu–Ni–Sn matrix with varying CrB2 content. Int. J. Refract. Hard Met. 2021, 100, 105655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechnik, V.G.; Bondarenko, N.A.; Duba, S.N.; Kolodnitskyi, V.M.; Nesterenko, Y.V.; Kuzin, N.O.; Zakiev, I.M.; Gevorkyan, E.S. A study of the microstructure of Fe-Cu-Ni-Sn and Fe-Cu-Ni-Sn-VN metal matrix for diamond-containing composites. Mater. Charact. 2018, 146, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechnyk, V.A. Diamond–Fe–Cu–Ni–Sn composite materials with predictable stable characteristics. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorenko, D.A.; Zaitsev, A.A.; Kirichenko, A.N.; Levashov, E.A.; Kurbatkina, V.V.; Loginov, P.A.; Rupasov, S.I.; Andreev, V.A. Interaction of diamond grains with nanosized alloying agents in metal–matrix composites as studied by Raman spectroscopy. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2013, 38, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, A.A.; Sidorenko, D.A.; Levashov, E.A.; Kurbatkina, V.V.; Rupasov, S.I.; Andreev, V.A.; Sevast'yanov, P.V. Development and application of the Cu–Ni–Fe–Sn based dispersion-hardened bond for cutting tools of superhard materials. J. Superhard Mater. 2012, 34, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechnik, V.A. Production of diamond−(Fe−Cu−Ni−Sn) composites with high wear resistance. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 2014, 52, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkyan, E.; Mechnik, V.; Bondarenko, N.; Vovk, R.; Lytovchenko, S.; Chishkala, V.; Melnik, O. Peculiarities of obtaining diamond–(Fe–Cu–Ni–Sn) hot pressing. Funct. Mater. 2017, 24, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechnik, V.A. Effect of hot recompaction parameters on the structure and properties of diamond–(Fe–Cu–Ni–Sn–CrB2) composites. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 2014, 52, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maystrenko, A.L. Formirovanie Sructury Kompozitsionnykh Almasosoderzhaschikh Materialov V Tekhnologicheskikh Protsessakh [Formation of Structure of Diamond Containing Composites in Technological Processes]; Naukova Dumka: Kiev, Ukraine, 2014; 342p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Konstanty, J. Powder Metallurgy Diamond Tools, UK, Oxford, 2005.

- Goldstein, M.I.; Farber, V.M. Dispersionnoe Uprochnenie Stali [Dispersive Hardening of Steel]; Metallurgia, Moscou, 1979; 208p. (In Russian).

- Korataev, A.D.; Tyumentsev, A.N.; Sukhovarov, V.F. Dispersionnoe Uprochnenie Tugoplavkikh Metallov [Dispersive hardening of refractory metals], Nauka, Siberian Branch, Novosibirsk RF, 1989, 211p. (In Russian).

- Goldstein, M.I.; Grachev, S.V.; Wexler, Y.G. Spetsial'nye Stali [Special Steel], Metallurgia, Moscou, 1985, 408 pp.

- Shevchenko, S.V.; Stetsenk, N.N. Nanostrukturnoe Sostoyanie V Metallakh, Splavakh I Intermetallichskikh Soedineniyakh: Metody Polycheniya, Struktura, Svooystva [Nanostructural state in metals, alloys and intermetallic connections: Receiving methods, structure, properties]. Uspekhi Fisiki Metallov 2004, 5, 219–255. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, V.S.; Balankin, A.S.; Bunin, I.Z.; Oksogoev, A.A. Sinergetika I Fraktaly V Materialovedenii [Synergetrics and Fractals in Materials Science], Nauka, Moscou, 1994; 383p. (in Russian).

- Eissa, M.; El-Fawakhry, K.; Ahmed, M.H.; et al. Development of superior high strength low impact transition temperature steels microalloyed with vanadium and nitrogen. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 1997, 5, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Skoblo, T.S.; Sapozhnikov, V.S.; Sidashenko, V.I. Vliyanie Nevetallicheskikh, Vklyuchenioy Na Ekspluatatsionnuyu Stooykost' Rel'sov [influence of nonmetallic inclusions on operational firmness of rails], 183 Herald of Petro Vasylenko Kharkiv National Technical University of Agriculture (KhNTUA), 2017, pp. 104–115 (in Russian).

- Borowiecka-Jamrozek, J.; Lachowski, J. Modelling of retention of a diamond particle in matrices based on Fe and Cu. Procedia Engineering 2017, 177, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowiecka-Jamrozek, J.; Lachowski, J. A Thermomechanical Model of Retention of a Diamond Particle in Matrices Based on Fe. Defect and Diffusion Forum 2020, 405, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Duan, L. A review of the diamond retention capacity of metal bond matrices. Metals 2018, 8, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, G.; Tan, Y.; Huang, H.; Guo, H.; Xu, X. Model Establishment of a Co-Based Metal Matrix with Additives of WC and Ni by Discrete Element Method. Materials 2018, 11, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratov, B.T.; Mechnik, V.A.; et al. Influence of CrB2 additive of the morphology, structure, microhardness and fracture resistance of diamond composites based on WC-Co matrix. Materialia 2022, 25, 101546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelig, R.P. Fundamentals of pressing of metal powder. In The Physics of Powder Metallurgy; Kingston, W.E., Ed.; McGraw-Hill, Book Comp. Inc., 1951; pp. 344–371. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, L.J.; da Paranhos, R.P.R.; da Guimarães, R.S.; Bobrovnitchii, G.S.; Filgueira, M. Use of PM Fe–Cu–SiC composites as bonding matrix for diamond tools. J. Powder Metall. 2007, 50, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsir, M.; Öksüz, K.E. Effects of sintering temperature and addition of Fe and B4C on hardness and wear resistance of diamond reinforced metal matrix composites. J. Superhard Mater. 2013, 35, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.P.; Bobrovnitchii, G.S.; Skury, A.L.D.; Guimaraes, R.S.; Filgueira, M. Structure, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of PM Fe-Cu-Co Alloys. Materials & Design 2010, 31, 522–526. [Google Scholar]

- Romański, A. Sintered Co-Fe-Cu materials, Proceedings of Euro PM2004 Congress & Exhibition, Vienna, Austria, 2004, 3, pp. 691-696.

- Romański, A.; Konstanty, J. The effect of PM consolidation route on microstructure and properties of cobalt-iron-copper materials. In Proceedings of the 4th International Powder Metallurgy Conference, Sakarya, Turkey; 2005; pp. 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- del Villar, M.; Muro, P.; Sanchez, J.M.; Iturriza, I.; Castro, F. Consolidation of diamond tools using Cu-Co-Fe based alloys as metallic binders, Powder Metallurgy, 2001, 44(1), pp. 82–90. Konstanty J., Stephenson T. F., Tyrała D.: Novel Fe-Ni-Cu-Sn matrix materials for the manufacture of diamond-impregnated tools, Diamond Tooling Journal, 2011, 2, pp. 26–29.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).