Submitted:

05 July 2023

Posted:

07 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. TMD Epidemiology: The OPPERA Study

2.1. Demographics

2.2. Role of Injury

2.3. Headache and chronic pain conditions

2.4. Phenotypical Clusters

3. Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint

3.1. Imaging and Diagnosis

3.2. Disease Course and Treatment

4. Technical Advances in TMJ Surgery

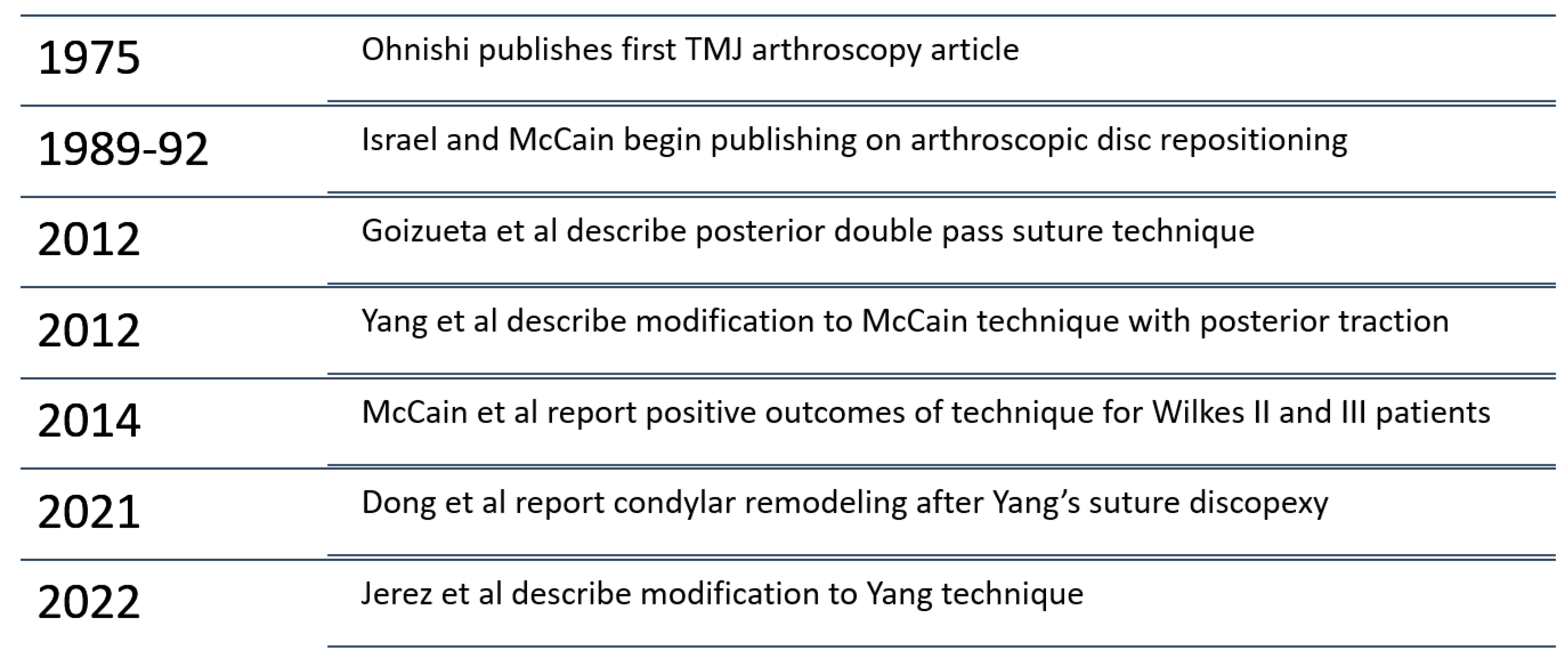

4.1. Advanced TMJ Arthroscopy

4.2. Treatment of TMJ Subluxation and Dislocation

4.3. Extended Total Temporomandibular Joint Reconstruction Prostheses (eTMJR)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valesan, L.F.; Da-Cas, C.D.; Réus, J.C.; Denardin, A.C.S.; Garanhani, R.R.; Bonotto, D.; Januzzi, E.; de Souza, B.D.M. Prevalence of temporomandibular joint disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercuri, L.; Neto, M.; Pourzal, R. Alloplastic temporomandibular joint replacement: present status and future perspectives of the elements of embodiment. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 51, 1573–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, G.D.; Bair, E.; By, K.; Mulkey, F.; Baraian, C.; Rothwell, R.; Reynolds, M.; Miller, V.; Gonzalez, Y.; Gordon, S.; et al. Study Methods, Recruitment, Sociodemographic Findings, and Demographic Representativeness in the OPPERA Study. J. Pain 2011, 12, T12–T26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, F.M.; Harkins, S.W.; Harrington, W.G.; Price, D.D. Analysis of gender effects on pain perception and symptom presentation in temporomandibular pain. Pain 1993, 53, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeResche, L. Epidemiology of Temporomandibular Disorders: Implications for the Investigation of Etiologic Factors. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1997, 8, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, G.D.; Fillingim, R.B.; Sanders, A.E.; Bair, E.; Greenspan, J.D.; Ohrbach, R.; Dubner, R.; Diatchenko, L.; Smith, S.B.; Knott, C.; et al. Summary of Findings From the OPPERA Prospective Cohort Study of Incidence of First-Onset Temporomandibular Disorder: Implications and Future Directions. J. Pain 2013, 14, T116–T124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Greenspan, J.D.; Ohrbach, R.; Fillingim, R.B.; Maixner, W.; Renn, C.L.; Johantgen, M.; Zhu, S.; Dorsey, S.G. Racial/ethnic differences in experimental pain sensitivity and associated factors – Cardiovascular responsiveness and psychological status. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0215534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willassen L, J.A., Kvinnsland S, Staniszewski K, Berge T, Rosén A, Catastrophizing Has a Better Prediction for TMD Than Other Psychometric and Experimental Pain Variable. Pain Res Manag 2020, 12.

- Sharma, S.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; LaMonte, M.J.; Zhao, J.; Slade, G.D.; Bair, E.; Greenspan, J.D.; Fillingim, R.B.; Maixner, W.; Ohrbach, R. Incident injury is strongly associated with subsequent incident temporomandibular disorder: results from the OPPERA study. Pain 2019, 160, 1551–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Ohrbach, R.; Fillingim, R.; Greenspan, J.; Slade, G. Pain Sensitivity Modifies Risk of Injury-Related Temporomandibular Disorder. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, E., et al., Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Groupdagger. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014, 28, 6–27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchivileva, I.E.; Ohrbach, R.; Fillingim, R.B.; Greenspan, J.D.; Maixner, W.; Slade, G.D. Temporal change in headache and its contribution to the risk of developing first-onset temporomandibular disorder in the Orofacial Pain: Prospective Evaluation and Risk Assessment (OPPERA) study. Pain 2016, 158, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chichorro, J.G.; Porreca, F.; Sessle, B. Mechanisms of craniofacial pain. Cephalalgia 2017, 37, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.B.; Slade, G.B.; Fillingim, R.B.; Ohrbach, R.D. A rose by another name? Characteristics that distinguish headache secondary to temporomandibular disorder from headache that is comorbid with temporomandibular disorder. Pain 2023, 164, 820–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bair, E., et al., Identification of clusters of individuals relevant to temporomandibular disorders and other chronic pain conditions: the OPPERA study. Pain 2016, 157, 1266–1278. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolf, C.J. Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011, 152, S2–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, G. Overlap of Five Chronic Pain Conditions: Temporomandibular Disorders, Headache, Back Pain, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, and Fibromyalgia. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2020, 34, s15–s28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaynor, S.M.; Bortsov, A.; Bair, E.; Fillingim, R.B.; Greenspan, J.D.; Ohrbach, R.; Diatchenko, L.; Nackley, A.; Tchivileva, I.E.; Whitehead, W.; et al. Phenotypic profile clustering pragmatically identifies diagnostically and mechanistically informative subgroups of chronic pain patients. Pain 2021, 162, 1528–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabshahi, B.; Cron, R.Q. Temporomandibular joint arthritis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the forgotten joint. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2006, 18, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.-K.; Thota, E.; Huang, J.-Y.; Wei, J.-C.; Resnick, C. Increased risk of temporomandibular joint disorders and craniofacial deformities in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 51, 1482–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnick, C.M.; Dang, R.; Henderson, L.A.; Zander, D.A.; Daniels, K.M.; Nigrovic, P.A.; Kaban, L.B. Frequency and Morbidity of Temporomandibular Joint Involvement in Adult Patients With a History of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel K, G.B., Bailey K, Saeed NR, Juvenile idiopathic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint - no longer the forgotten joint. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2022, 60, 247–256. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niibo, P.; Pruunsild, C.; Voog-Oras. ; Nikopensius, T.; Jagomägi, T.; Saag, M. Contemporary management of TMJ involvement in JIA patients and its orofacial consequences. EPMA J. 2016, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Southwood, T.R.; Manners, P.; Baum, J.; Glass, D.N.; Goldenberg, J.; He, X.; Maldonado-Cocco, J.; Orozco-Alcala, J.; Prieur, A.-M.; et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J. Rheumatol. 2004, 31, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kovalko I, S.P., Twilt M, Temporomandibular joint involvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: challenges in diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Curr Treat Options Rheumatol 2018, 4, 44–54. [CrossRef]

- Cannizzaro, E., et al., Temporomandibular joint involvement in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2011, 38, 510–515. [CrossRef]

- Stoll, M.L.; Sharpe, T.; Beukelman, T.; Good, J.; Young, D.; Cron, R.Q. Risk Factors for Temporomandibular Joint Arthritis in Children with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2012, 39, 1880–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, T.K.; Küseler, A.; Gelineck, J.; Herlin, T. A prospective study of magnetic resonance and radiographic imaging in relation to symptoms and clinical findings of the temporomandibular joint in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2008, 35, 1668–1675. [Google Scholar]

- Stoustrup, P.; Herlin, T.; Spiegel, L.; Rahimi, H.; Koos, B.; Pedersen, T.K.; Twilt, M. Standardizing the Clinical Orofacial Examination in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: An Interdisciplinary, Consensus-based, Short Screening Protocol. J. Rheumatol. 2020, 47, 1397–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C., et al., The Diagnosis and Treatment of Rheumatoid and Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2022, 119, 47–54. [CrossRef]

- Clemente, E.J.I.; Tolend, M.; Navallas, M.; Doria, A.S.; Meyers, A.B. MRI of the temporomandibular joint in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: protocol and findings. Pediatr. Radiol. 2023, 53, 1498–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, E.; Clemente, E.J.I.; Tzaribachev, N.; Guleria, S.; Tolend, M.; Meyers, A.B.; von Kalle, T.; Stimec, J.; Koos, B.; Appenzeller, S.; et al. Imaging of temporomandibular joint abnormalities in juvenile idiopathic arthritis with a focus on developing a magnetic resonance imaging protocol. Pediatr. Radiol. 2018, 48, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellenberger, C.J.; Abramowicz, S.; Arvidsson, L.Z.; Kirkhus, E.; Tzaribachev, N.; Larheim, T.A. Recommendations for a Standard Magnetic Resonance Imaging Protocol of Temporomandibular Joints in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 76, 2463–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaid, Y.N.; Dunnavant, F.D.; Royal, S.A.; Beukelman, T.; Stoll, M.L.; Cron, R.Q. Imaging of the Temporomandibular Joint in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2013, 66, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navallas, M.; Inarejos, E.J.; Iglesias, E.; Lee, G.Y.C.; Rodríguez, N.; Antón, J. MR Imaging of the Temporomandibular Joint in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Technique and Findings. RadioGraphics 2017, 37, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, L., et al., Early diagnosis of temporomandibular joint involvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a pilot study comparing clinical examination and ultrasound to magnetic resonance imaging. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009, 48, 680–685. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell LJ, B.D., Boers M The evolution of instrument selection for inclusion in core outcome sets at OMERACT: Filter 2.2. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2021, 51, 1320–1330. [CrossRef]

- Tolend, M.A.; Twilt, M.; Cron, R.Q.; Tzaribachev, N.; Guleria, S.; von Kalle, T.; Koos, B.; Miller, E.; Stimec, J.; Vaid, Y.; et al. Toward Establishing a Standardized Magnetic Resonance Imaging Scoring System for Temporomandibular Joints in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2018, 70, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch K, P.Z., Resnick CM Regional diferences in temporomandibular joint infammation in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a dynamic post-contrast magnetic resonance imaging study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020, 49, 1210–1216. [CrossRef]

- Kupka, M.J.; Aguet, J.; Wagner, M.M.; Callaghan, F.M.; Goudy, S.L.; Abramowicz, S.; Kellenberger, C.J. Preliminary experience with black bone magnetic resonance imaging for morphometry of the mandible and visualisation of the facial skeleton. Pediatr. Radiol. 2022, 52, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, C.; Reich, R.; Koos, B.; Ertel, T.; Ahlers, M.O.; Arbogast, M.; Feurer, I.; Habermann-Krebs, M.; Hilgenfeld, T.; Hirsch, C.; et al. Controversial Aspects of Diagnostics and Therapy of Arthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint in Rheumatoid and Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis—An Analysis of Evidence- and Consensus-Based Recommendations Based on an Interdisciplinary Guideline Project. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousquet, B. Bousquet, B., et al., Does Magnetic Resonance Imaging Distinguish Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis From Other Causes of Progressive Temporomandibular Joint Destruction? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bag, A.K. Imaging of the temporomandibular joint: An update. World J. Radiol. 2014, 6, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuente, S.E.A.d.l.; Angenete, O.; Jellestad, S.; Tzaribachev, N.; Koos, B.; Rosendahl, K. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis and the temporomandibular joint: A comprehensive review. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2016, 44, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoustrup, P.; Lerman, M.A.; Twilt, M. The Temporomandibular Joint in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2021, 47, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoustrup, P.; Twilt, M. Improving treatment of the temporomandibular joint in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: let’s face it. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2019, 15, 1119–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollhalder, A.; Patcas, R.; Eichenberger, M.; Müller, L.; Schroeder-Kohler, S.; Saurenmann, R.K.; Kellenberger, C.J. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Followup of Temporomandibular Joint Inflammation, Deformation, and Mandibular Growth in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Patients Receiving Systemic Treatment. J. Rheumatol. 2020, 47, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinard, B.; Goldberg, B.; Kau, C.; Abramowicz, S. Clinical trials of temporomandibular joint involvement of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Oral Surgery, Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2021, 131, 617–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, M.L.; Amin, D.; Powell, K.K.; Poholek, C.H.; Strait, R.H.; Aban, I.; Beukelman, T.; Young, D.W.; Cron, R.Q.; Waite, P.D. Risk Factors for Intraarticular Heterotopic Bone Formation in the Temporomandibular Joint in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2018, 45, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbuhler, N., et al., Magnetic Resonance Imaging Assessment of Temporomandibular Joint Involvement and Mandibular Growth Following Corticosteroid Injection in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. J Rheumatol 2015, 42, 1514–1522. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnick, C.M.; Pedersen, T.K.; Abramowicz, S.; Twilt, M.; Stoustrup, P.B. Time to Reconsider Management of the Temporomandibular Joint in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 76, 1145–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen-Bergem, H.; Bjørnland, T. A cohort study of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and arthritis of the temporomandibular joint: outcome of arthrocentesis with and without the use of steroids. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 43, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alstergren P, L.P., Kopp S, Successful treatment with multipleintra-articular injections of infliximab in a patient with psoriatic arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 2008, 37, 155–157. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoll, M.L.; Cron, R.Q.; Saurenmann, R.K. Systemic and intra-articular anti-inflammatory therapy of temporomandibular joint arthritis in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Semin. Orthod. 2015, 21, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, M.L.; Morlandt, A.B.P.; Teerawattanapong, S.; Young, D.; Waite, P.D.; Cron, R.Q. Safety and efficacy of intra-articular infliximab therapy for treatment-resistant temporomandibular joint arthritis in children: a retrospective study. Rheumatology 2012, 52, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frid, P.; Resnick, C.; Abramowicz, S.; Stoustrup, P.; Nørholt, S. Surgical correction of dentofacial deformities in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 48, 1032–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nørholt, S.; Pedersen, T.; Herlin, T. Functional changes following distraction osteogenesis treatment of asymmetric mandibular growth deviation in unilateral juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a prospective study with long-term follow-up. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 42, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, B.; Adell, R. Costochondral grafts to replace mandibular condyles in juvenile chronic arthritis patients: long-term effects on facial growth. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 1998, 26, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, N.; Hensher, R.; McLeod, N.; Kent, J. Reconstruction of the temporomandibular joint autogenous compared with alloplastic. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2002, 40, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechler, B.; Matthews, N. Role of alloplastic reconstruction of the temporomandibular joint in the juvenile idiopathic arthritis population. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 59, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoustrup, P.; Pedersen, T.K.; Nørholt, S.E.; Resnick, C.M.; Abramowicz, S. Interdisciplinary Management of Dentofacial Deformity in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. North Am. 2019, 32, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, B., et al., Does Combined Temporomandibular Joint Reconstruction With Patient Fitted Total Joint Prosthesis and Orthognathic Surgery Reduce Symptoms in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Patients? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2022, 80, 267–275. [CrossRef]

- Raffaini, M.; Arcuri, F. Orthognathic surgery for juvenile idiopathic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint: a critical reappraisal based on surgical experience. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 51, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øye, F.; Bjørnland, T.; Støre, G. Mandibular osteotomies in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritic disease. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2003, 32, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshem, D.; Tompson, B.; Britto, J.A.; Forrest, C.R.; Phillips, J.H. Orthognathic Surgery in Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006, 117, 1941–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnoni, M.; Amodeo, G.; Fadda, M.T.; Brauner, E.; Guarino, G.; Virciglio, P.; Iannetti, G. Juvenile Idiopathic/Rheumatoid Arthritis and Orthognatic Surgery Without Mandibular Osteotomies in the Remittent Phase. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2013, 24, 1940–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma KS, I.R.M., Veeravalli JJ, Wang LT, Thota E, Huang JY, Kao CT, Wei JC, Resnick CM, Patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis are at increased risk for obstructive sleep apnoea: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Orthod 2022, 44, 222–231.

- Ward, T.M.; Archbold, K.; Lentz, M.; Ringold, S.; Wallace, C.A.; Landis, C.A. Sleep Disturbance, Daytime Sleepiness, and Neurocognitive Performance in Children with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Sleep 2010, 33, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegelberg, A.; Kopp, S. Short-term effect of physical training on temporomandibular joint disorder in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1988, 46, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoustrup, P.; Kristensen, K.; Küseler, A.; Verna, C.; Herlin, T.; Pedersen, T. Management of temporomandibular joint arthritis-related orofacial symptoms in juvenile idiopathic arthritis by the use of a stabilization splint. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2014, 43, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Garcia, R. and R. Martin-Granizo, Arthroscopic Disc Repositioning Techniques of the Temporomandibular Joint: Part 1: Sutures. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2022, 30, 175–183. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Granizo, R.; González-García, R. Arthroscopic Disc Repositioning Techniques of the Temporomandibular Joint Part 2: Resorbable Pins. Atlas Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. 2022, 30, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, H.A. Technique for placement of a discal traction suture during temporomandibular joint arthroscopy. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1989, 47, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarro, A.W. Arthroscopic treatment of anterior disc displacement: A preliminary report. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1989, 47, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, M. Arthroscopic laser surgery and suturing for temporomandibular joint disorders: Technique and clinical results. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 1991, 7, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondoh, T., Arthroscopic traction suturing. Treatment of internal derangement by arthroscopic repositioning and suturing of the disk. Advances in diagnostic and surgical arthroscopy of the temporomandibular joint. Clark, GT, Sanders, B. and Bertolami, CN eds., WB Saunders Company, Philadelphia, 1993: p. 117-127.

- Tarro, A.W. A fully visualized arthroscopic disc suturing technique. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1994, 52, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adame, C.C.G.; Muñoz-Guerra, M.F. The posterior double pass suture in repositioning of the temporomandibular disc during arthroscopic surgery: A report of 16 cases. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2012, 40, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, J.P.; Podrasky, A.E.; Zabiegalski, N.A. Arthroscopic disc repositioning and suturing: A preliminary report. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1992, 50, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Cai, X.-Y.; Chen, M.-J.; Zhang, S.-Y. New arthroscopic disc repositioning and suturing technique for treating an anteriorly displaced disc of the temporomandibular joint: part I – technique introduction. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 41, 1058–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-Y.; Liu, X.-M.; Yang, C.; Cai, X.-Y.; Chen, M.-J.; Haddad, M.S.; Yun, B.; Chen, Z.-Z. New Arthroscopic Disc Repositioning and Suturing Technique for Treating Internal Derangement of the Temporomandibular Joint: Part II—Magnetic Resonance Imaging Evaluation. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 68, 1813–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerez, D., et al., Modification to Yang’s Arthroscopic Discopexy Technique for Temporomandibular Joint Disc Displacement: A Technical Note. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2022, 80, 989–995. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gimeno, C.; García-Hernández, A.; Martínez-Martínez, R. Single portal arthroscopic temporomandibular joint discopexy: Technique and results. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2021, 49, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millón-Cruz, A.; López, R.M.-G. Long-term clinical outcomes of arthroscopic discopexy with resorbable pins. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2020, 48, 1074–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Granizo, R.; Millón-Cruz, A. Discopexy using resorbable pins in temporomandibular joint arthroscopy: Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging medium-term results. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2016, 44, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goizueta-Adame, C.C., D. Pastor-Zuazaga, and J.E. Orts Banon, Arthroscopic disc fixation to the condylar head. Use of resorbable pins for internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint (stage II-IV). Preliminary report of 34 joints. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2014, 42, 340–346. [CrossRef]

- Sato, F.R.L.; Tralli, G. Arthroscopic discopexy technique with anchors for treatment of temporomandibular joint internal derangement: Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging evaluation. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2020, 48, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrehem, A.; Hu, Y.-K.; Yang, C.; Zheng, J.-S.; Shen, P.; Shen, Q.-C. Arthroscopic versus open disc repositioning and suturing techniques for the treatment of temporomandibular joint anterior disc displacement: 3-year follow-up study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 50, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askar, H.; Aronovich, S.; Christensen, B.J.; McCain, J.; Hakim, M. Is Arthroscopic Disk Repositioning Equally Efficacious to Open Disk Repositioning? A Systematic Review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 79, 2030–2041 e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.d.S.; Pagotto, L.E.C.; Nascimento, E.S.; da Cunha, L.R.; Cassano, D.S.; Gonçalves, J.R. Effectiveness of disk repositioning and suturing comparing open-joint versus arthroscopic techniques: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Surgery, Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2021, 132, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, J.P.; Hossameldin, R.H.; Srouji, S.; Maher, A. Arthroscopic Discopexy Is Effective in Managing Temporomandibular Joint Internal Derangement in Patients With Wilkes Stage II and III. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 73, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, K.-I.; Tsuboi, Y.; Bessho, K.; Yokoe, Y.; Nishida, M.; Iizuka, T. Outcome of arthroscopic surgery to the temporomandibular joint correlates with stage of internal derangement: five-year follow-up study. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1998, 36, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, M.K.; Abdelrehem, A.; Chen, S.; Shen, P.; Jiao, Z.; Hu, Y.K.; Nie, X.; Yang, C. Prognostic indicators of arthroscopic discopexy for management of temporomandibular joint closed lock. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.; Jiao, Z.; Sun, Q.; Tao, X.; Yang, C.; Qiu, W. The magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of condylar new bone remodeling after Yang’s TMJ arthroscopic surgery. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.M.; Hakim, M.; Choi, D.D.; Behrman, D.A.; Israel, H.; McCain, J.P. Early Clinical Outcomes of Arthroscopic Management of the Failing Alloplastic Temporomandibular Joint Prosthesis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 78, 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, A.; McLeod, N.; Spijkervet, F.; Riechmann, M.; Vieth, U.; Kolk, A.; Sidebottom, A.J.; Bonte, B.; Speculand, B.; Saridin, C.; et al. The ESTMJS (European Society of Temporomandibular Joint Surgeons) Consensus and Evidence-Based Recommendations on Management of Condylar Dislocation. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renapurkar, S.K.; Laskin, D.M. Injectable Agents Versus Surgery for Recurrent Temporomandibular Joint Dislocation. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. North Am. 2018, 30, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.-Y.; Chen, H.-M.; Sun, Z.-P.; Zhang, Z.-K.; Ma, X.-C. Long-term efficacy of botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of habitual dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 48, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghol, K.; Abdelrahman, A.; Pigadas, N. Guided botulinum toxin injection to the lateral pterygoid muscles for recurrent dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 59, 845–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocaciu, S.; McCullough, M.J.; Dimitroulis, G. Surgical management of recurrent TMJ dislocation—a systematic review. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 23, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machon, V.; Abramowicz, S.; Paska, J.; Dolwick, M.F. Autologous Blood Injection for the Treatment of Chronic Recurrent Temporomandibular Joint Dislocation. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coser, R.; da Silveira, H.; Medeiros, P.; Ritto, F. Autologous blood injection for the treatment of recurrent mandibular dislocation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 44, 1034–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegab, A.F. Treatment of chronic recurrent dislocation of the temporomandibular joint with injection of autologous blood alone, intermaxillary fixation alone, or both together: a prospective, randomised, controlled clinical trial. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 51, 813–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, H.; Nakatani, Y.-I.; Gamoh, S.; Shimizutani, K.; Morita, S. Clinical outcome after 36 months of treatment with injections of autologous blood for recurrent dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 56, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daif, E.T. Autologous blood injection as a new treatment modality for chronic recurrent temporomandibular joint dislocation. Oral Surgery, Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2010, 109, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machon, V.; Levorova, J.; Hirjak, D.; Wisniewski, M.; Drahos, M.; Sidebottom, A.; Foltan, R. A prospective assessment of outcomes following the use of autologous blood for the management of recurrent temporomandibular joint dislocation. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 22, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayoumi, A.; Al-Sebaei, M.; Mohamed, K.; Al-Yamani, A.; Makrami, A. Arthrocentesis followed by intra-articular autologous blood injection for the treatment of recurrent temporomandibular joint dislocation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 43, 1224–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Anchlia, S.; Sadhwani, B.S.; Bhatt, U.; Rajpoot, D. Arthrocentesis Followed by Autologous Blood Injection in the Treatment of Chronic Symptomatic Subluxation of Temporomandibular Joint. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2022, 21, 1218–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refai, H. Long-term therapeutic effects of dextrose prolotherapy in patients with hypermobility of the temporomandibular joint: a single-arm study with 1-4 years’ follow up. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 55, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagori, S.A.; Jose, A.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Roy, I.D.; Chattopadhyay, P.K.; Roychoudhury, A. The efficacy of dextrose prolotherapy over placebo for temporomandibular joint hypermobility: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oral Rehabilitation 2018, 45, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, R.W.-S.; Reeves, K.D.; Zhong, C.C.; Wong, C.H.L.; Wang, B.; Chung, V.C.-H.; Wong, S.Y.-S.; Rabago, D. Efficacy of hypertonic dextrose injection (prolotherapy) in temporomandibular joint dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Baidya, M.; Srivastava, A.; Garg, H. Comparison of autologous blood prolotherapy and 25% dextrose prolotherapy for the treatment of chronic recurrent temporomandibular joint dislocation on the basis of clinical parameters: A retrospective study. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 13, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoda, T.; Ogi, N.; Yoshitake, H.; Kawakami, T.; Takagi, R.; Murakami, K.; Yuasa, H.; Kondoh, T.; Tei, K.; Kurita, K. Clinical guidelines for total temporomandibular joint replacement. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2020, 56, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khattak, Y.R., et al., Extended total temporomandibular joint reconstruction prosthesis: A comprehensive analysis. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 2023, 124, 101404. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Qudsi, A.; Mittal, D.; Mercuri, L.; Shah, B.; Emmerling, M.; Murphy, J. Utilization of extended temporomandibular joint replacements in patients with hemifacial microsomia. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elledge, R.; Mercuri, L.; Speculand, B. Extended total temporomandibular joint replacements: a classification system. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 56, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elledge, R.O.; Higginson, J.; Mercuri, L.G.; Speculand, B. Validation of an extended total joint replacement (eTJR) classification system for the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 59, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginson, J.; Panayides, C.; Speculand, B.; Mercuri, L.G.; Elledge, R.O. Modification of an extended total temporomandibular joint replacement (eTMJR) classification system. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 60, 983–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mommaerts, M.Y.; Nicolescu, I.; Dorobantu, M.; De Meurechy, N. Extended total temporomandibular joint replacement with occlusal adjustments: Pitfalls, patient-reported outcomes, subclassification, and a new paradigm. Ann. Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 10, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).