1. Introduction

Heterocyclic compounds have a central place in medicinal chemistry, being used as therapeutic agents to treat most diseases [1–3]. Among these heterocycles, benzimidazole stands out, as a purine-analog pharmacophore, with a wide biological activity, such as antimicrobial [4–8], antiviral [9,10], antihistamine [11,12], anticonvulsant [3,13], antitumor [14–16], proton pump inhibitors [17], antiparasitic [16,18,19], anti-inflammatory [20–22], or antihypertensive [23,24]. Some benzimidazoles are efficient agents in Diabetes mellitus [25–27], while astemizole compounds possess anti-prion activity to treat Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease [5,28]. The literature also reports anti-Alzheimer [29,30], psychoactive, anxiolytic, analgesic [31,32], and anticoagulant properties [33,34] of benzimidazole derivatives. Also, for triazole compounds, the literature mentions a series of therapeutic activities, such as antimicrobial [35–38], antitubercular [39,40], potential inhibitors of SARS CoV-2 [41–43], antiviral [43,44] anti-inflammatory [45,46] antitumor [47–50], antihypertensive [50], antioxidant [47,51,52] and antiepileptic [53,54]. Pharmacological applications of triazoles refer to their activity as α-glucosidase inhibitors [55,56], analgesic [50,57], anticonvulsant [53,58], and antimalarial agents [57,59]. Triazole derivatives are efficient in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease [60,61] and are very effective neuroprotective agents [62,63].

The successive events happened from the spring of 2020 up to and including the present, regarding the emergence and development of the COVID-19 pandemic, have led the scientific world to investigate more closely the possibility of treating this infectious disease with various antiviral [64–66], antimicrobial [67], immunomodulatory [68] or anti-inflammatory drugs [69], therefore, the discovery of new molecules with simple or hybrid structures, with biological properties that satisfy the requirements of the treatment of this condition it is absolutely necessary and constitutes the engine of the development of new effective therapeutic agents.

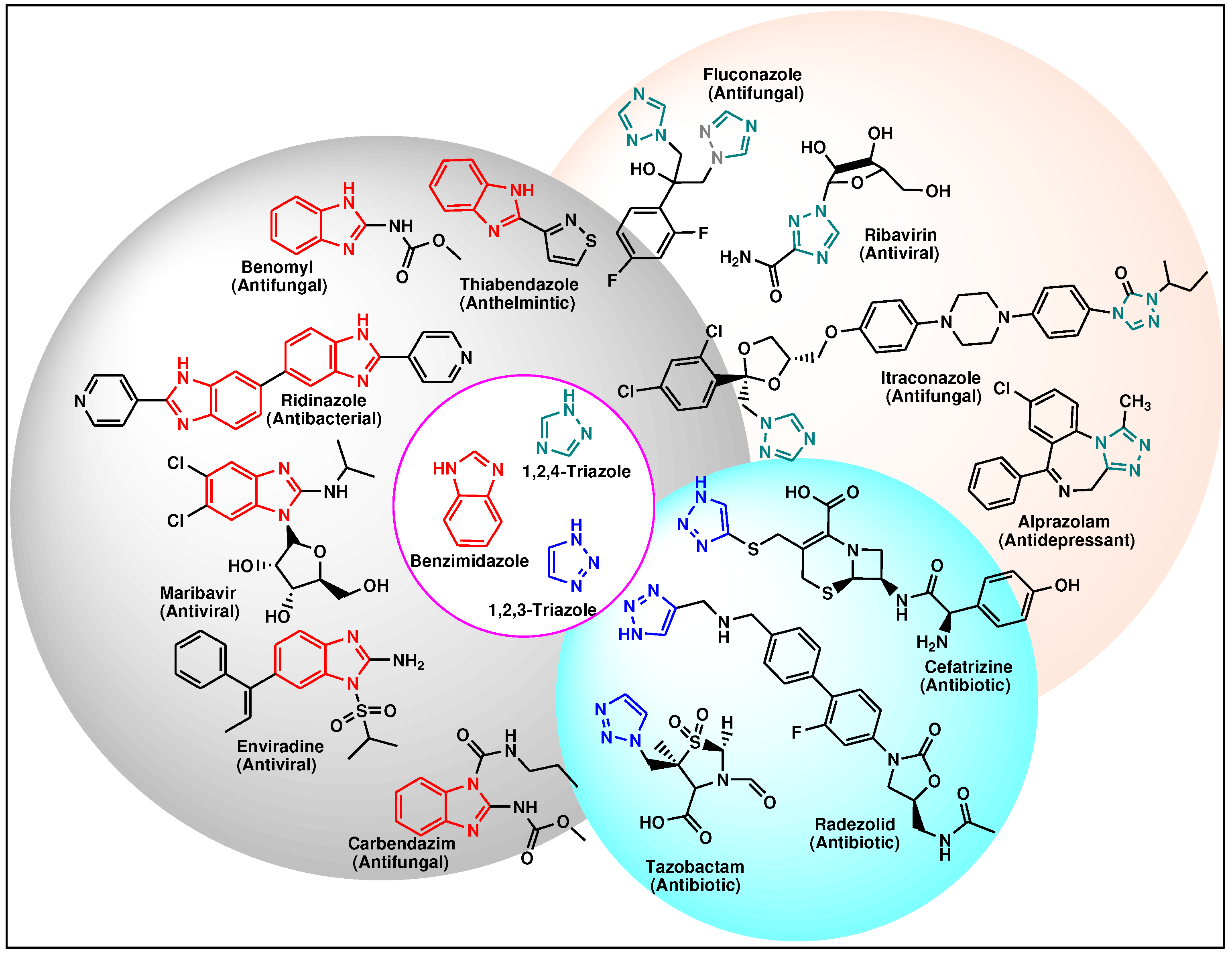

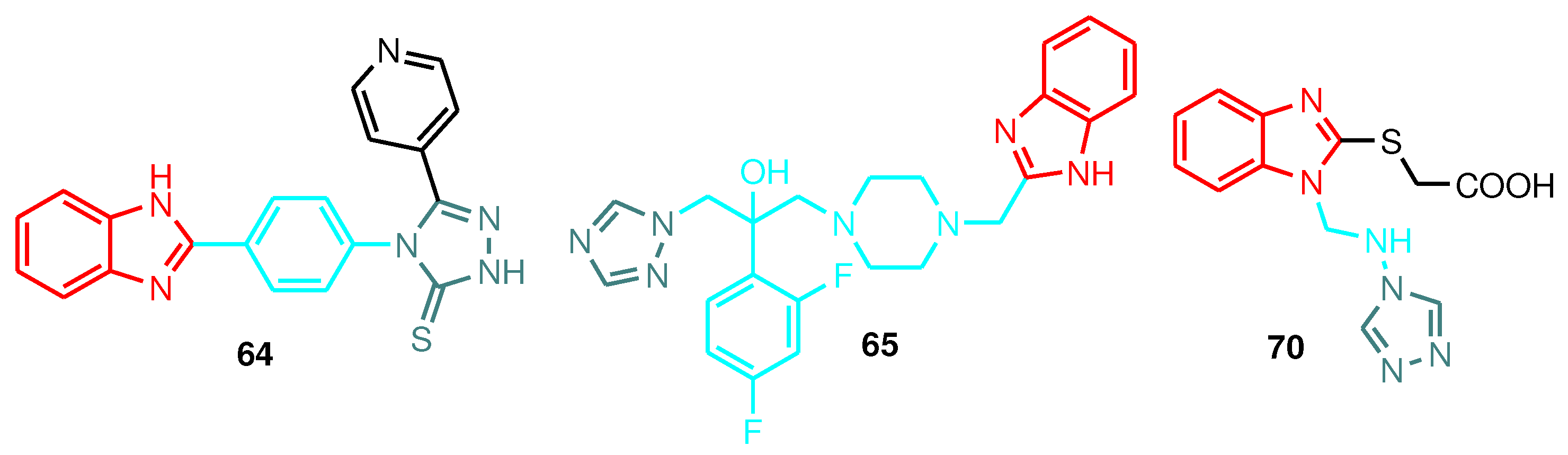

Classical drugs containing benzimidazole and triazole rings recommend these heterocycles as essential in building new target compounds with antimicrobial, antiviral, antiparasitic, etc. properties (Figure 1). In addition, the literature mentions a series of benzimidazole-triazole hybrids with remarkable antimicrobial properties, antiviral activities, including new anti-SARS-COV-2 agents [70–74], with particular importance in the context of the recent pandemic, which led to the study of synthesis methods, antimicrobial properties, structure-property relationships and their biological activities. As expected, the study refers to both 1,2,3-triazole-benzimidazole hybrids and 1,2,4-triazole-benzimidazole hybrids, even if it seems that the literature is richer in the second category, in terms of antimicrobial activity.

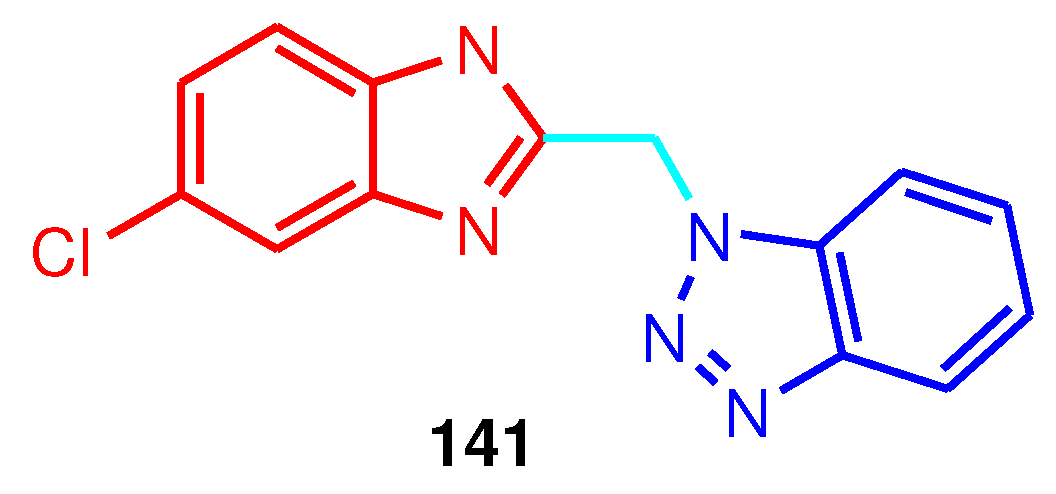

In order to highlight the structures of the heterocycles in the discussed compounds, we colored benzimidazole nucleus with red, 1,2,3-triazole with blue and 1,2,4-triazole with green.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Chemical structures of some benzimidazole, 1,2,3-triazole and 1,2,4-triazole-based marketed drugs

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Chemical structures of some benzimidazole, 1,2,3-triazole and 1,2,4-triazole-based marketed drugs

The recent literature marks several strategies for the synthesis of 1,2,3-triazoles, like click reaction [

75], Bouiton-Katritzky rearrangement [

76], oxidative cyclization of hydrazones [

77], post-cycloaddition functionalization [

78], alkylation or arylation of triazoles [

79]. Also, for benzimidazoles, the literature mentions several methods of synthesis, such as reaction of

o-phenenediamine with aldehydes or ketones (Phillips-Ladenburg reaction) [

3,

80,

81,

82], with acids or their derivatives (Weidenhagen reaction) [

81], or green methods of classic syntheses [80, 83–86].

In the following, we will present syntheses of benzimidazole-triazole hybrids with antimicrobial and antiviral properties.

4. Synthesis and antiviral activities of benzimidazole-triazoles

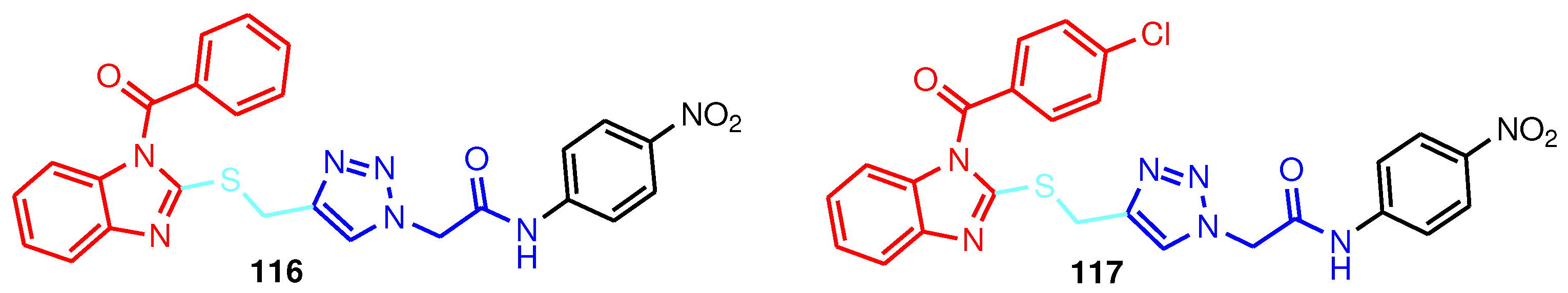

Youssif et

al. reported synyhesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 2-{4-[(1-benzoylbenzimidazol-2-ylthio)methyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl}-N-(p-nitro--phenyl)-acetamide

116 and 2-(4-{[1-(p-chlorobenzoyl)-benzimidazol-2-ylthio)methyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazol -1-yl}-N-(p-nitrophenyl)-acetamide

117 which showed significant activity against hepatitis C virus (HCV) (

Figure 13). Thus, fifty percent effective concentrations (EC

50) of HCV inhibition for compounds

116 and

117 were 7.8 and 7.6 μmol L

–1, respectively, and the 50 % cytotoxic concentrations (CC

50) were 16.9 and 21.1 μmol L

–1.The results gave an insight into the importance of the substituent at position 2 of benzimidazole for the inhibition of HCV [

73].

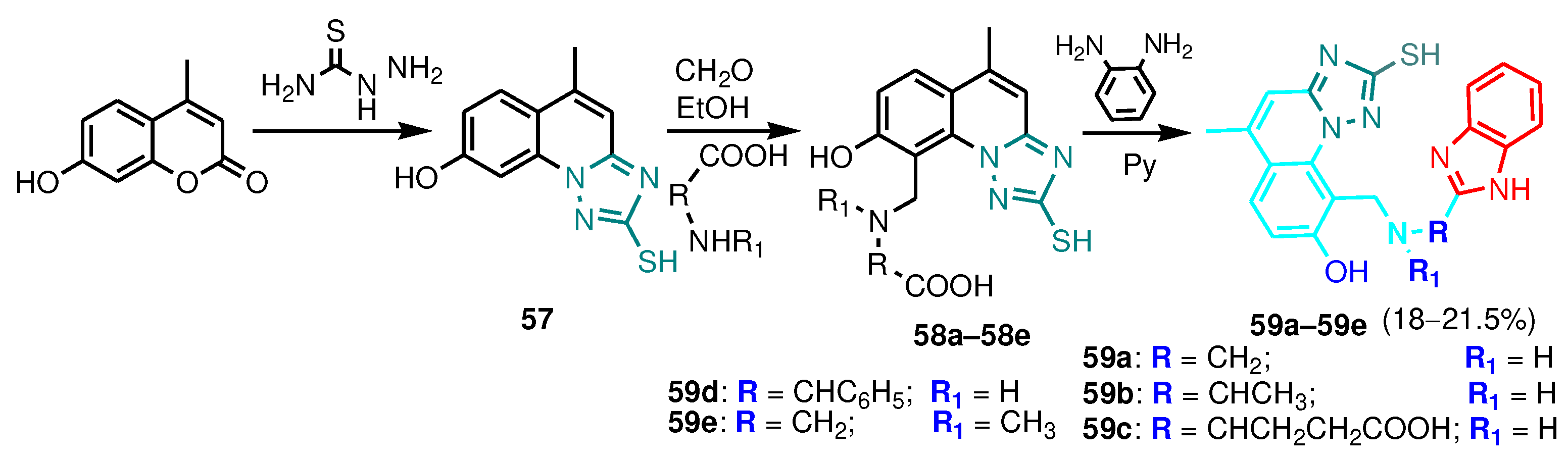

Antiviral activity of compounds

59a–

59e was tested against two viruses, viz.,

Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) (P20778), a RNA virus of higher pathogenicity, and

Herpes simplex virus type-I (HSV-I) (753166), the most common virus present in the environment. The antiviral activity of the compounds data are given in

Table 12. All but one of the five compounds were found active against JEV. Compound

59b displayed 90% CPE (cytopathic effect)

in vitro with an effective concentration of 8 µg mL

–1 while its

in vivo activity was less significant (16% protection with a MST of 4 days). The authors sugested that that these compounds are better anti-JEV agents than anti-HSV agents, since two such compounds, namely

59b and

59e, also displayed a measurable degree of anti-JEV activity

in vivo. Compound

59c was found antivirally inactive against both viruses. The anti HSV-I activity was found to be in the order of 33, 46, 53 and 64% for compounds

59a,

59b,

59d and

59e, respectively. Since among compounds

59a to

59e only compound

59e contains a methyl group instead of H as R

1, it follows that R

1 does not seem to be responsible for the biological activity [

87].

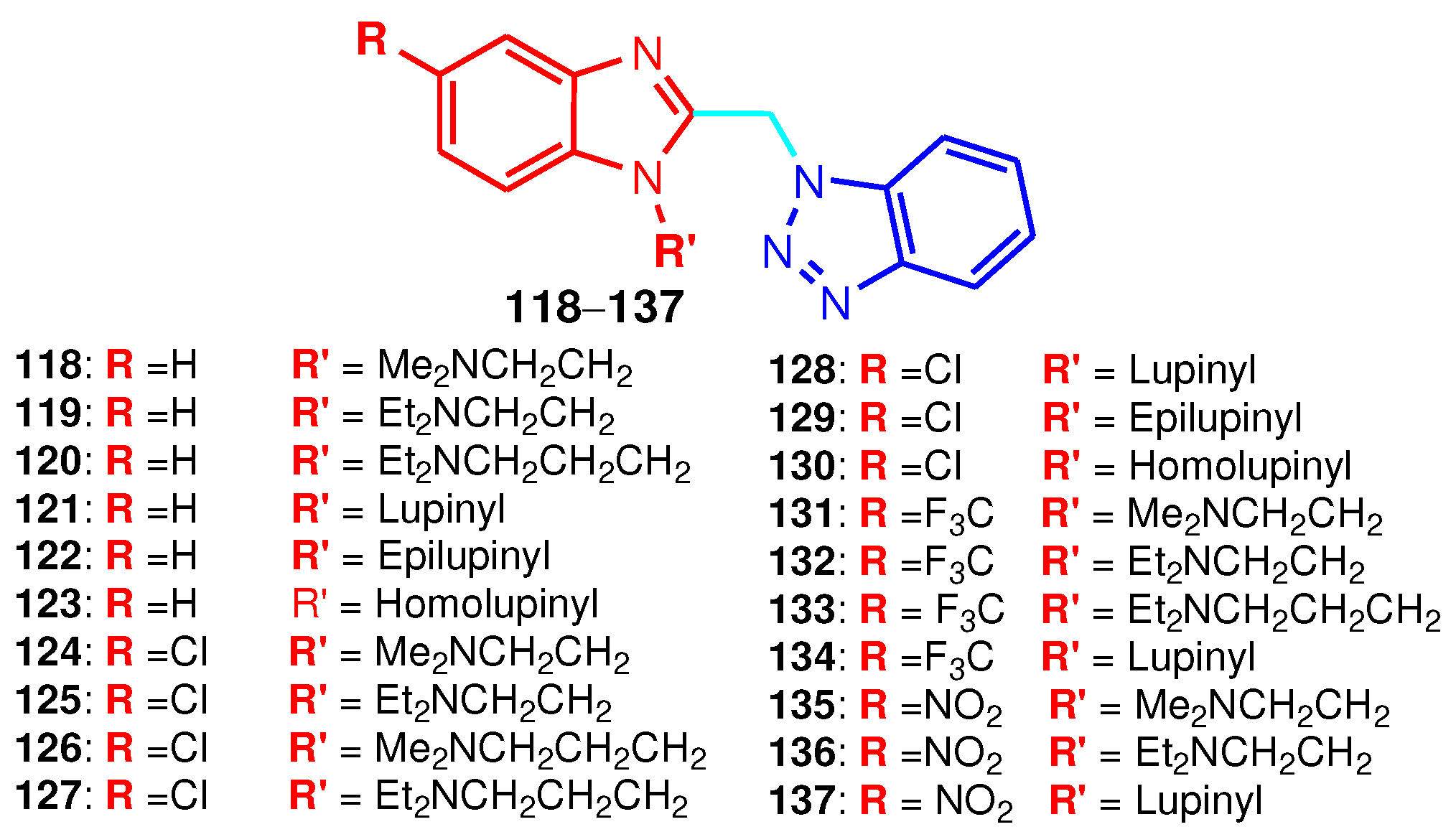

Tonelli et

al. synthesized a series of 1-substituted 2-[(benzotriazol-1/2-yl)methyl] benzimidazoles

118–137 and tested for antiviral activity against a large panel of RNA and DNA viruses (

Figure 14). Twelve compounds exhibited high activity against RSV (Respiratory Syncytial Virus), with EC

50 values in most cases below 1 µM, comparing favorably with the reference drug 6-azauridine, which, moreover, exhibited a high toxicity against both the MT-4 and Vero-76 cell lines (S.I. =16.7). The observed activity against BVDV, YFV, and CVB2 is moderate, with EC50 values in the range of 6 – 55 µM for the best compounds (

Table 13) [

127].

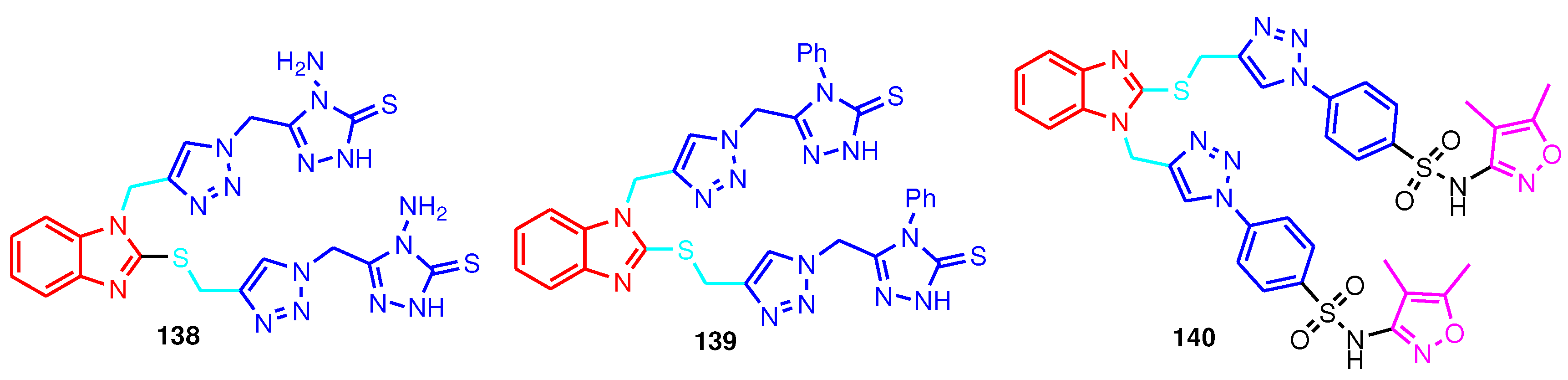

SARS-CoV-2 and its variants, especially the Omicron variant, remain a great threat to human health. Al-Humaidi et al. reported synthesis a series of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazoles

138–

140 (

Figure 15). Molecular docking studies and

in vitro enzyme activity revealed that most of the investigated compounds demonstrated promising binding scores against the SARS-CoV-2 and Omicron spike proteins, in comparison to the reference drugs (

Table 14).

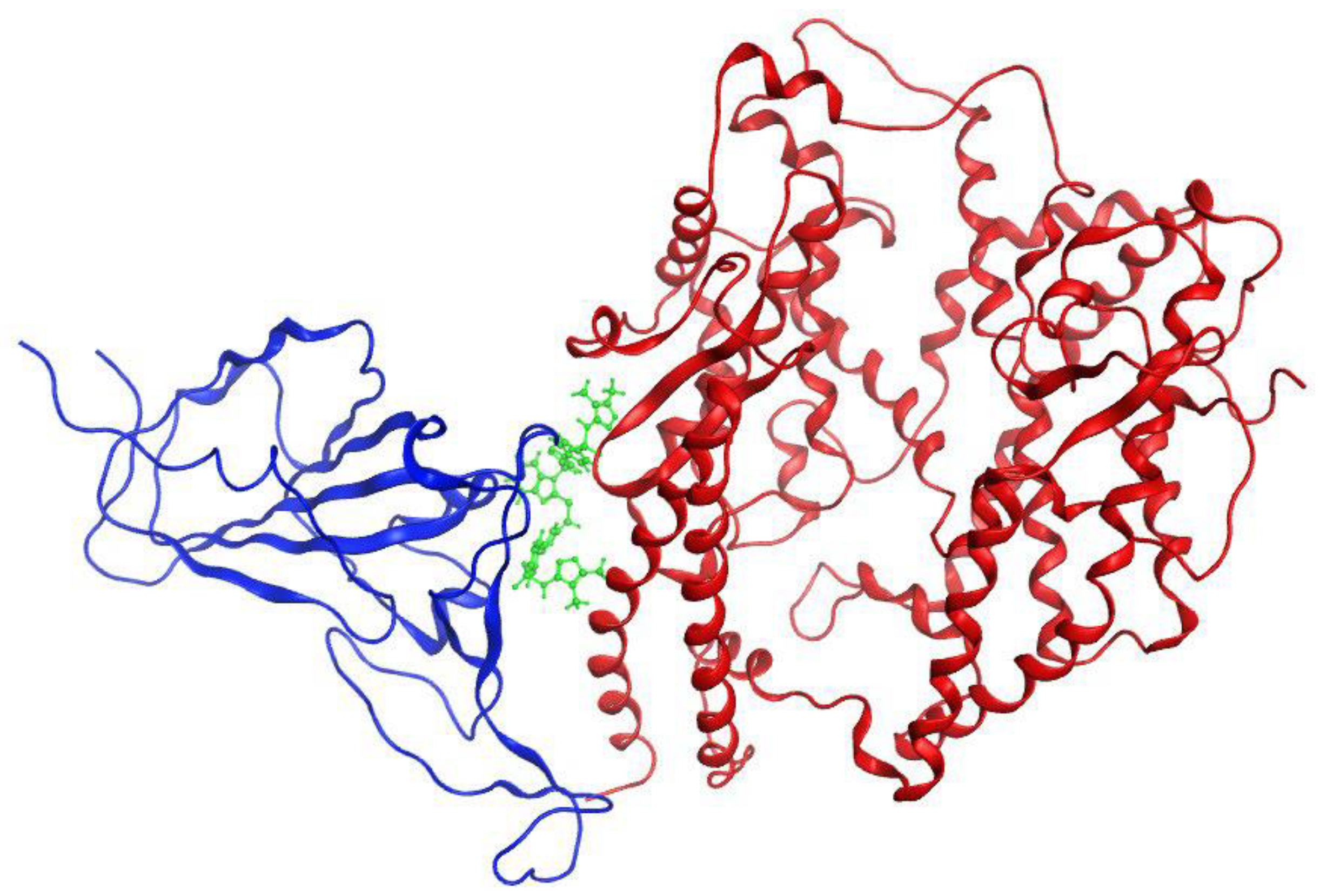

Three-dimensional binding mode of compound

140 is shown in

Figure 16 [

74]. Benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids can be potent anti-HSV (Herpes simplex virus) agents. These compounds were screened against flaviviruses and pestiviruses. Compound

141 showed excellent activity against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) with an EC

50 value of 0.02 mM (

Figure 17) [

128].

5. Conclusions

This review summarizes the syntheses of benzimidazole–triazole compounds with antimicrobial an antiviral properties mentioned in the literature. The presence of certain groups grafted on the benzimidazole and trizole nuclei, such as -F, -Cl, -Br, -CF

3, -NO

2, -CN, -NHCO, -CHO, -OH, OCH

3, -N(CH

3)

2, COOCH

3, as well as other heterocycles in the molecule (pyridine, pyrimidine, thiazole, indole, isoxazole, thiadiazole, coumarine), increases the antimicrobial activity of the compounds [

4,

5,

83,

84,

129,

130,

131]. From the presented literature data, we can highlight some aspects related to the correlation structure - antimicrobial properties.

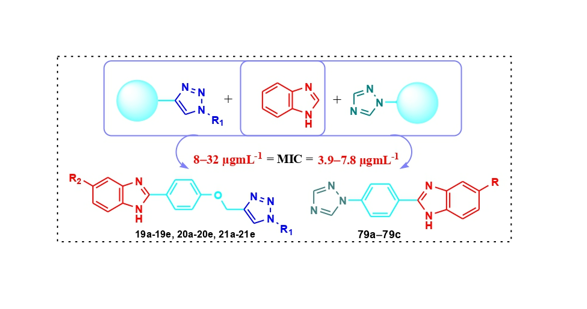

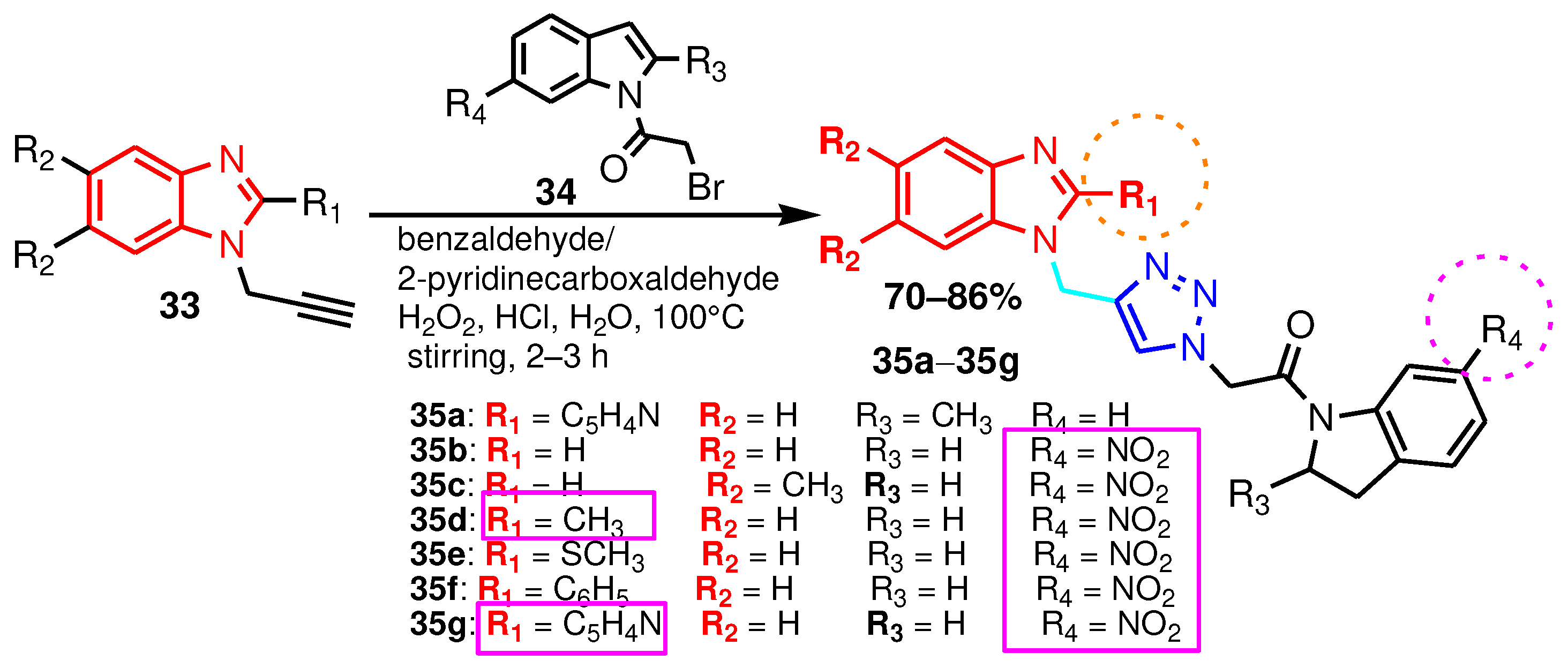

- The presence of substituents in the "4" or "5" positions of the benzimidazole nucleus can increase the antimicrobial activity of the benzimidazole-triazole hybrids (compounds 12, 13, 19, 20, 35).

- The presence of the ortho or para substituted phenyl substituent in the "1" position of 1,2,3-triazoles in benzimidazole-triazole hybrids can increase their antimicrobial activity.

- In the case of benzimidazoles substituted in the "1" position with triazoles, the presence of an aliphatic or aromatic radical substituent increases the antimicrobial activity of the hybrids.

- The presence of the oxygen atom in the bridge that connects the benzimidazole and triazole rings is favorable to the antimicrobial activity of the hybrids (compounds 19, 20, 21, 29, 30)

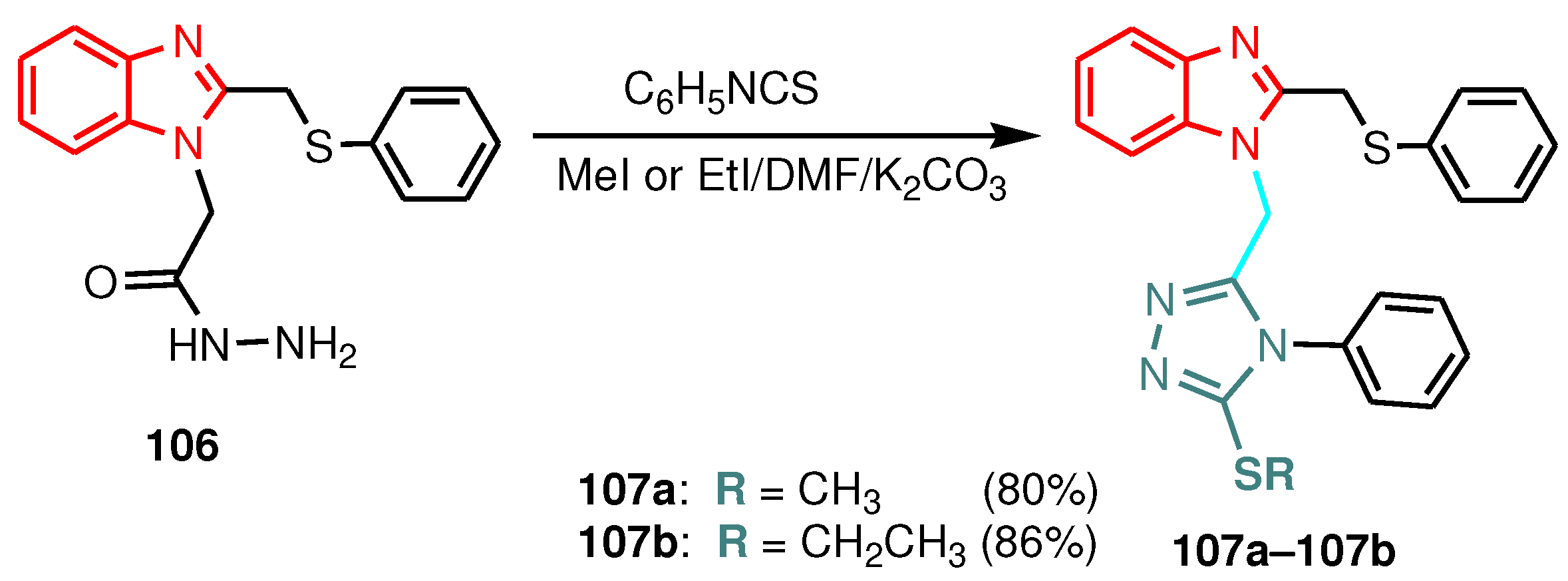

- The presence of the sulfur atom in the bridge that connects the benzimidazole and triazole rings is favorable to the antimicrobial activity of the hybrids, and even to the antitubercular activity (95–97, 105, 107).

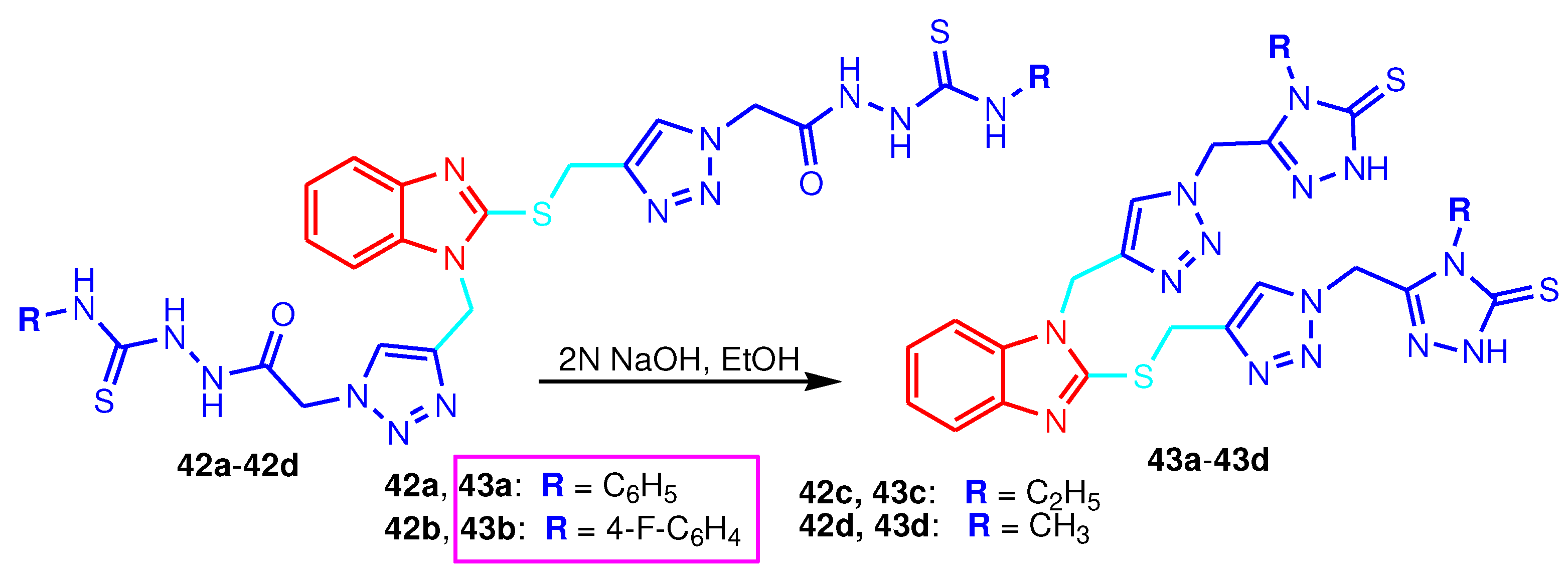

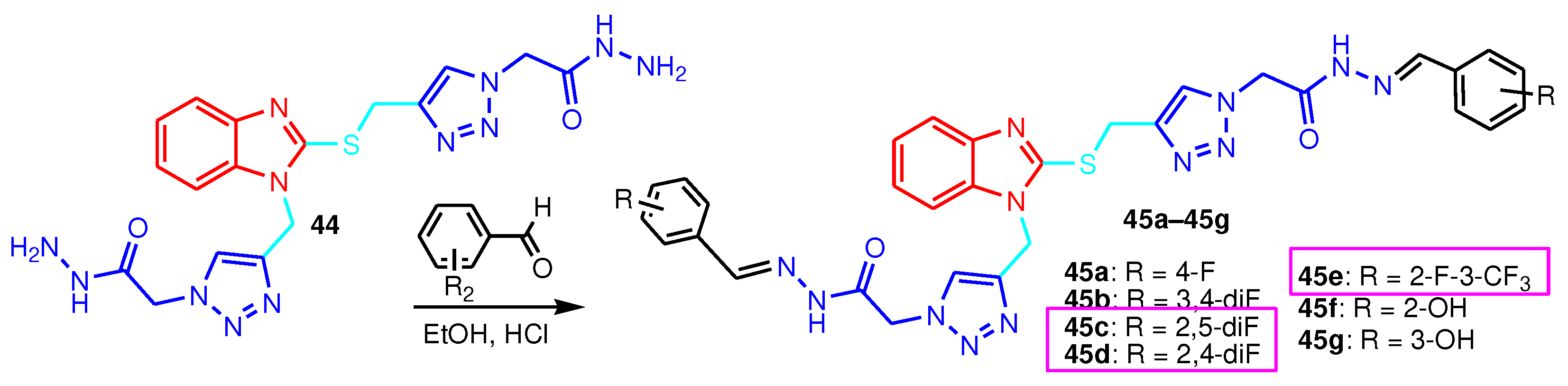

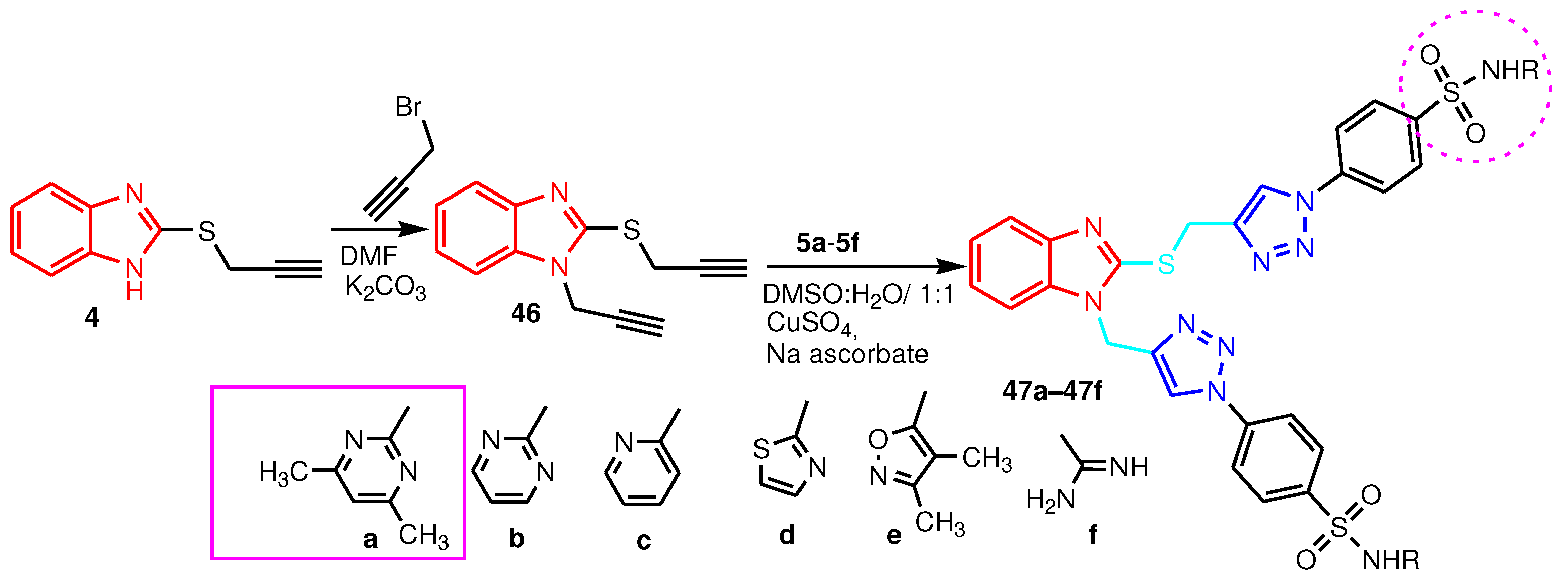

- The presence of a supplementary triazole ring in benzimidazole-triazole hybrids improves their antimicrobial activity (compounds 43, 45, 47).

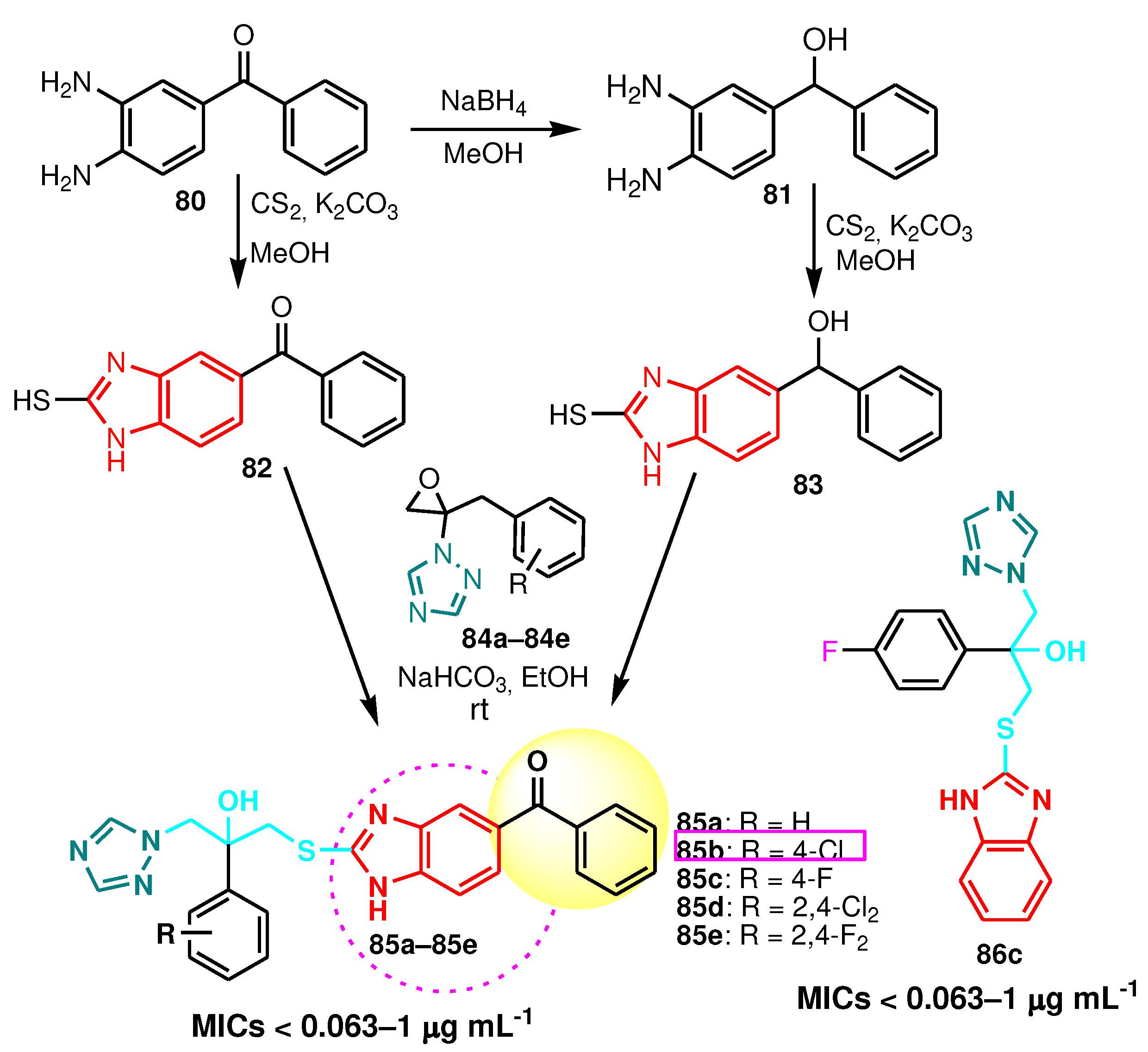

- The presence of the benzoyl substituent in the "5" position of the benzimidazole in the benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids clearly improves their antimicrobial activity (compounds 85a-85e).

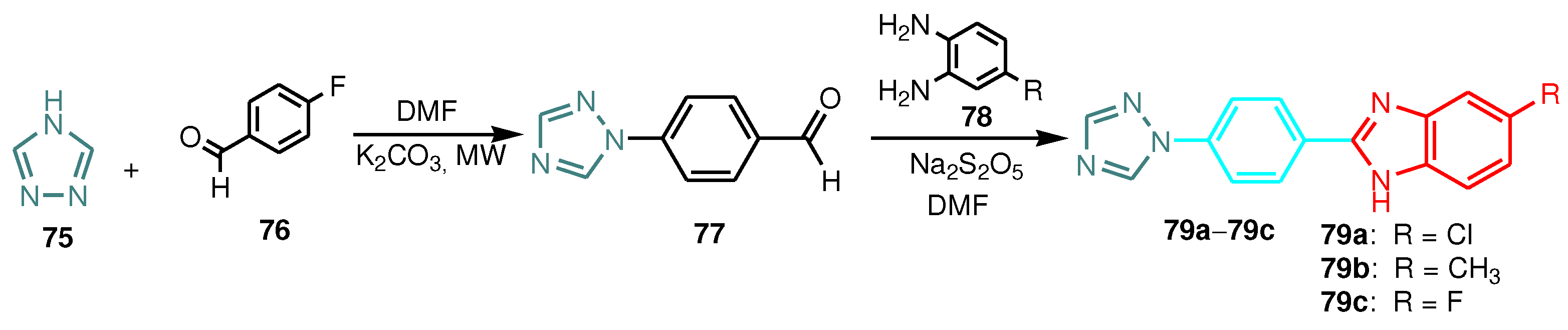

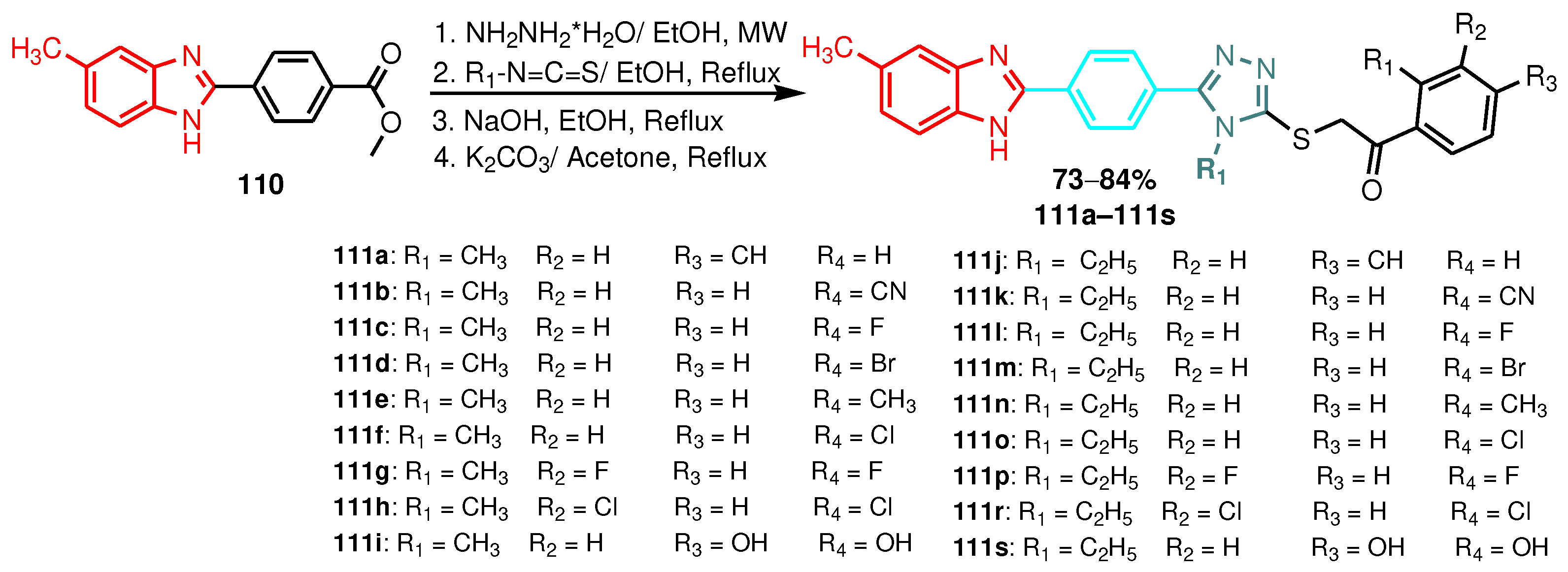

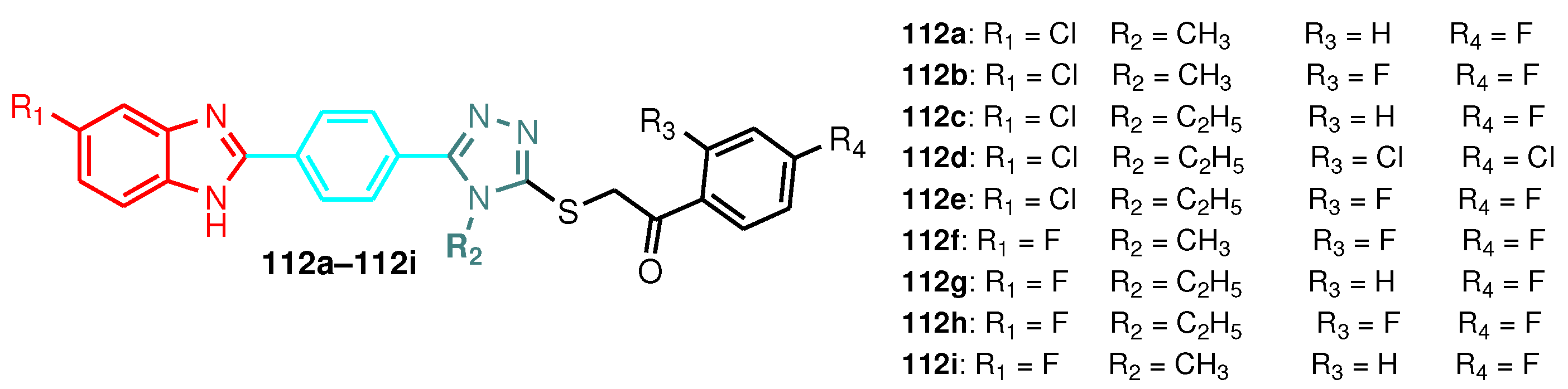

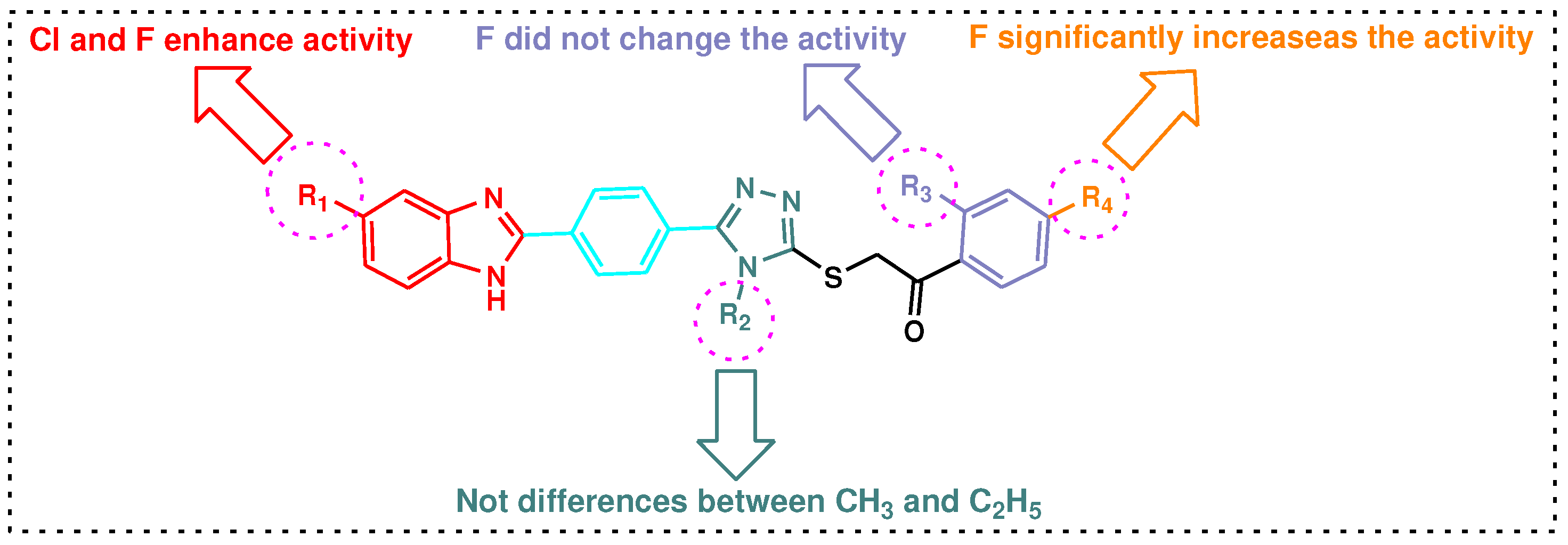

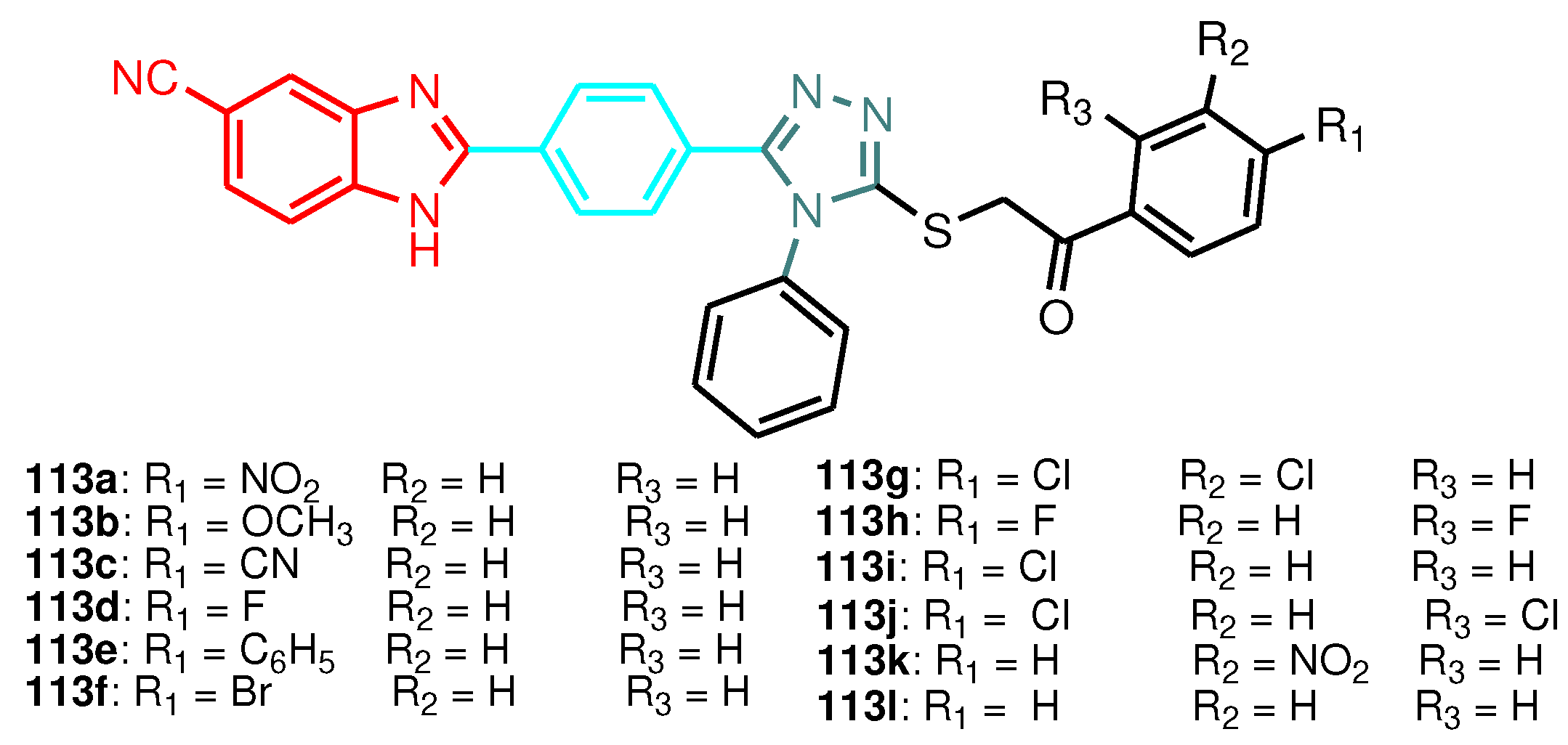

- The phenyl nucleus as a spacer between the "1" position of 1,2,4-triazole and the "2" position of benzimidazole favors the formation of antimicrobial compounds, and the substituents in the "5" position of the benzimidazole nucleus increase the antimicrobial activity (compounds 79, 111, 112, 113).

- Only benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids are mentioned in the literature as having antiviral properties.

- 2-Substituted or 1,2-disubstituted benzimidazoles with 1,2,3-triazoles are mentioned as antiviral compounds and the presence of an additional triazole ring improves the antiviral activity (compound 140).

We hope that this review will be useful for the design and synthesis of new benzimidazole-triazole hybrids with antimicrobial and antiviral properties in the context of exacerbation of microbial and viral infections and of resistance to treatments with drugs known on the market.

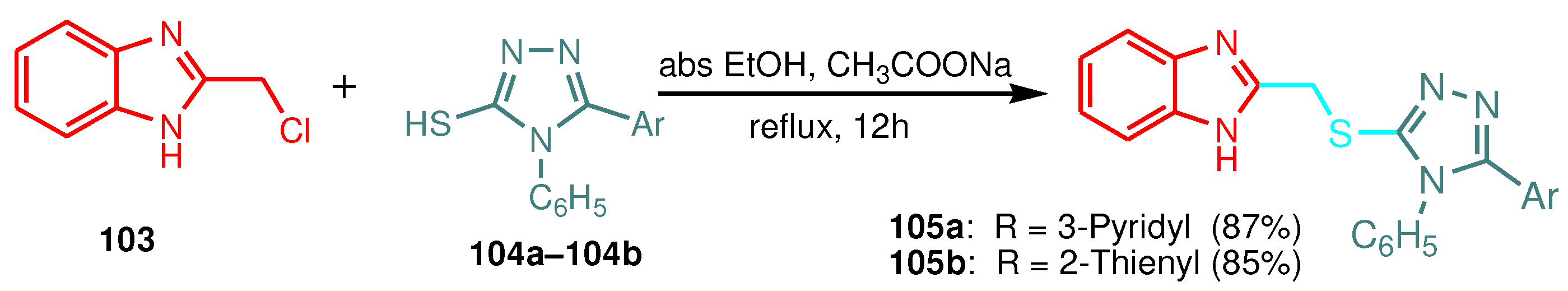

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 2a-2l and 3a-3f

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 2a-2l and 3a-3f

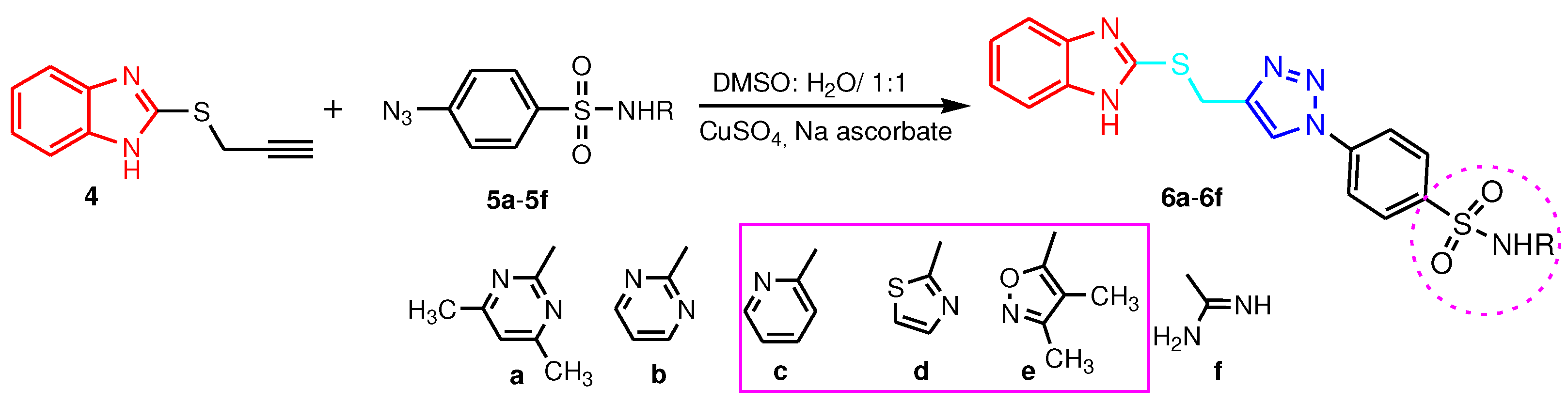

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 6a-6f

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 6a-6f

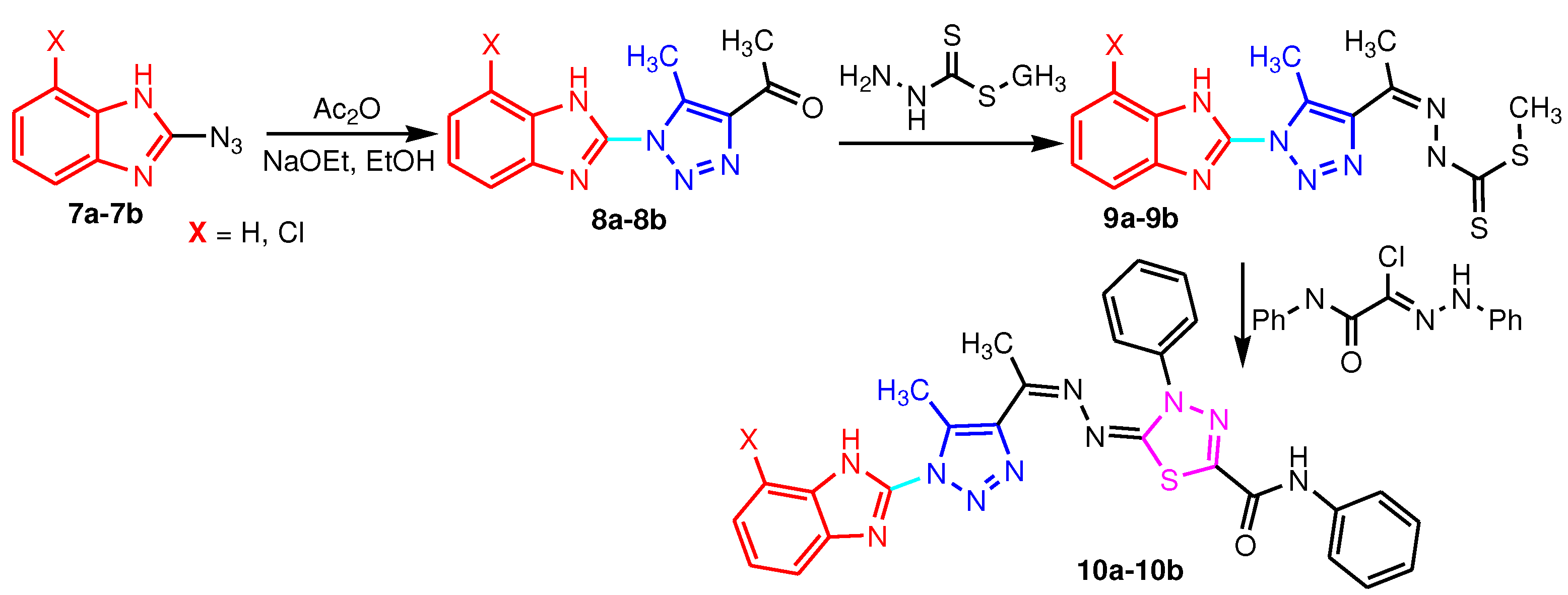

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 8a-8b, 9a-9b and 10a-10b

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 8a-8b, 9a-9b and 10a-10b

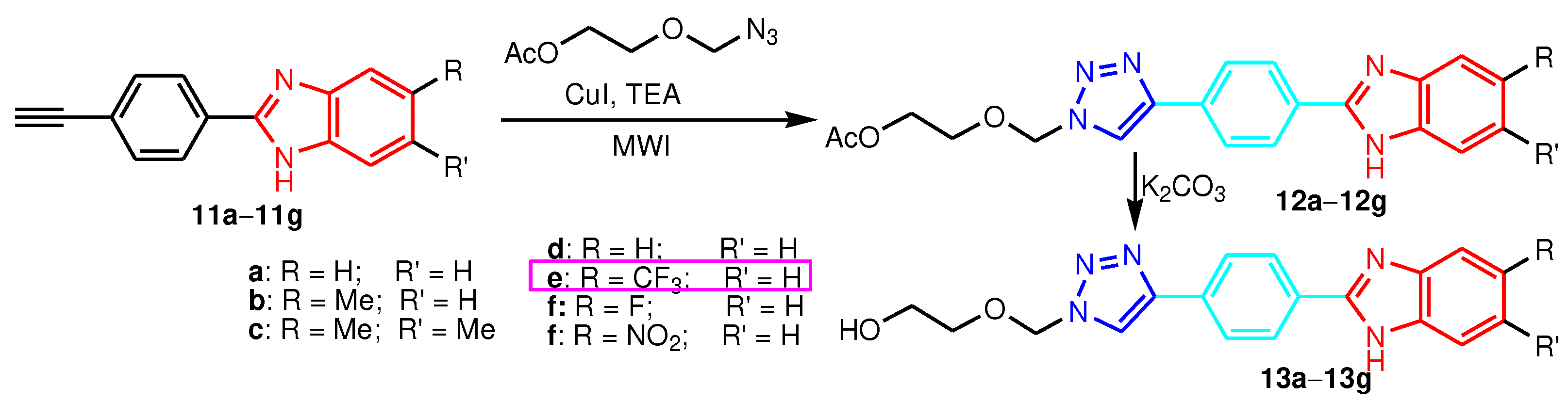

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 6a–6g

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 6a–6g

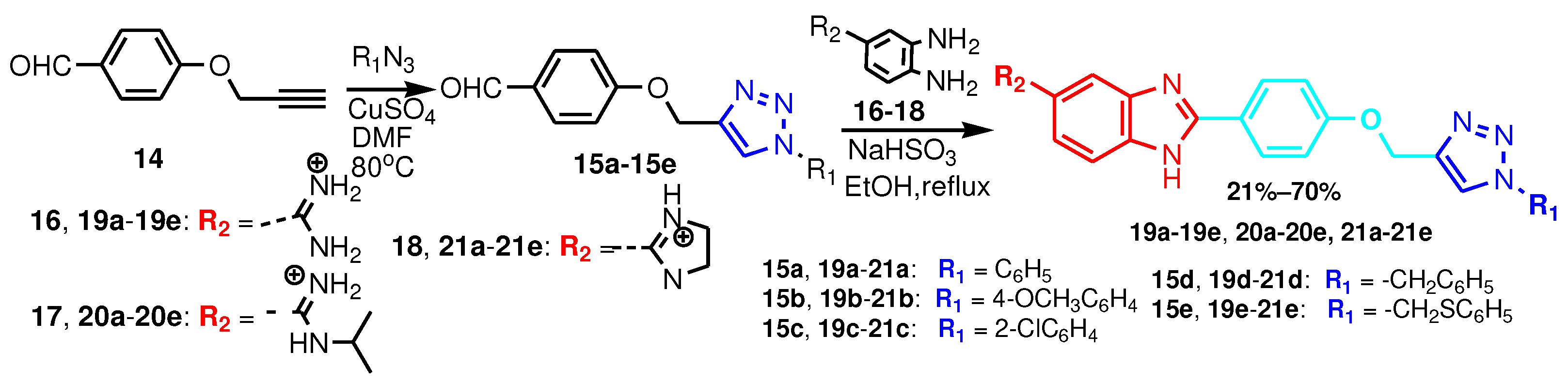

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 19a–19e, 20a–20e and 21a–21e

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 19a–19e, 20a–20e and 21a–21e

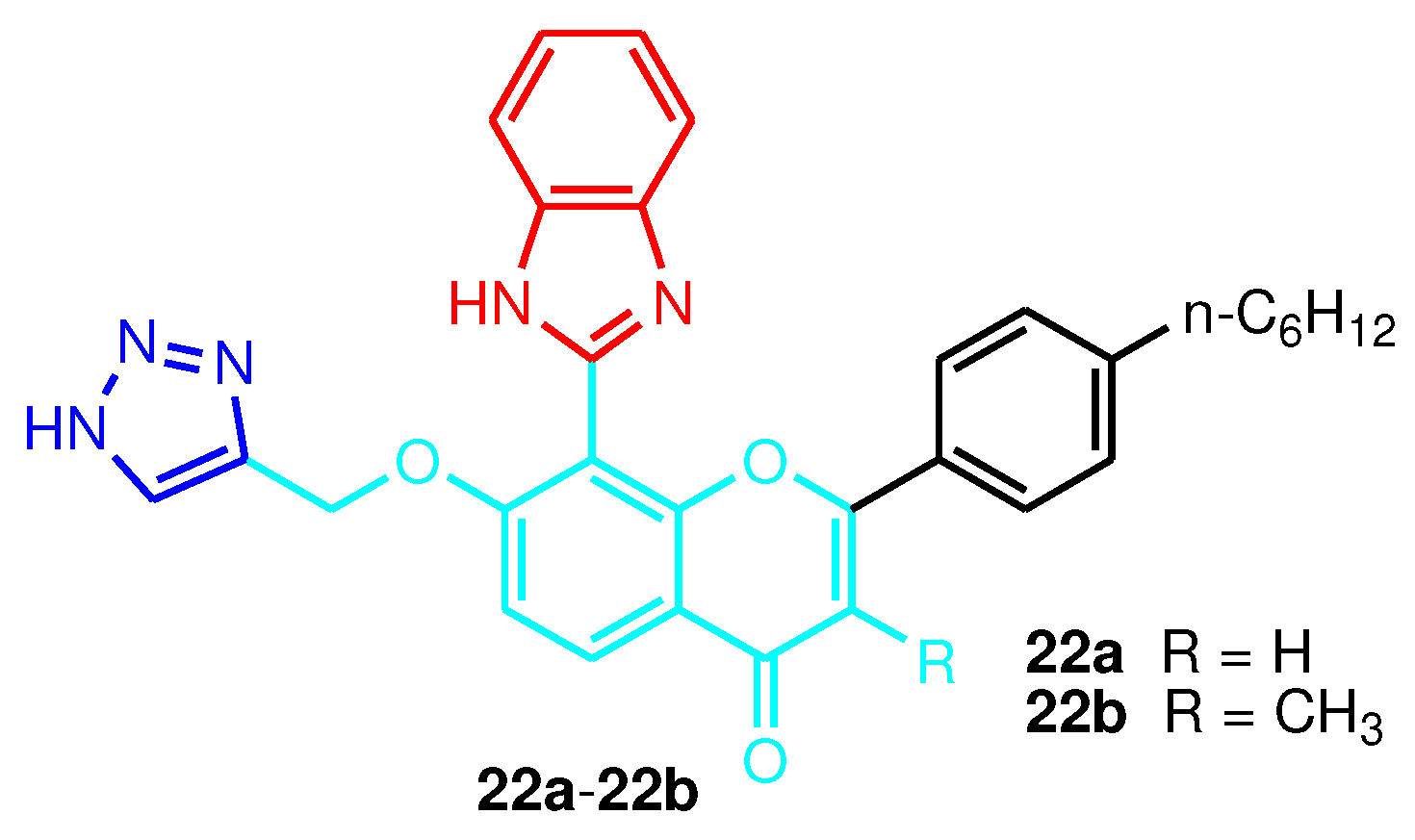

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 22a–22b

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 22a–22b

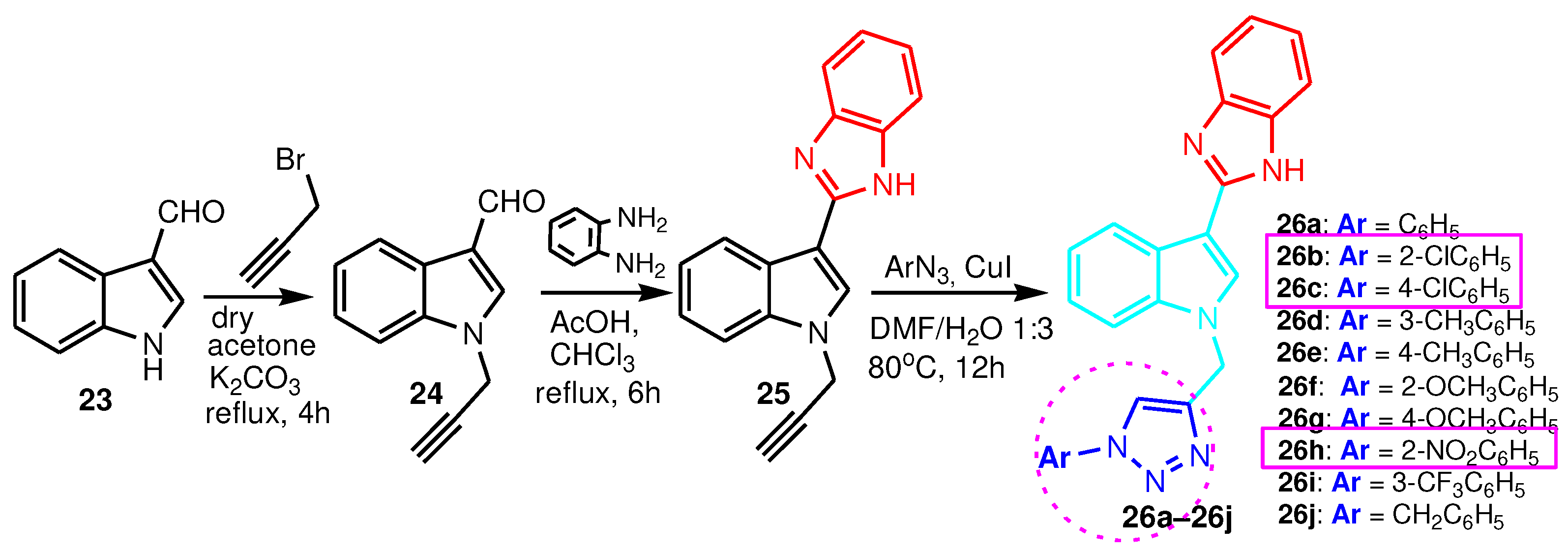

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 26a–26j

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 26a–26j

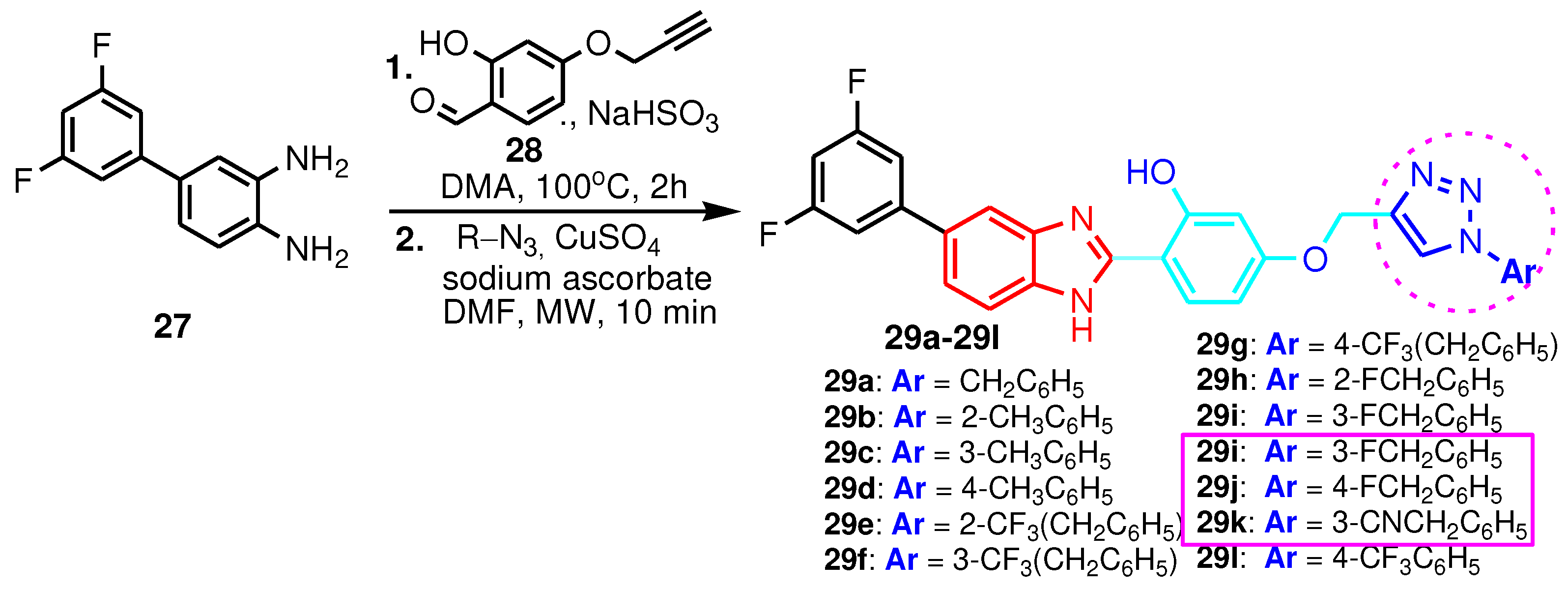

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 29a–29l

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 29a–29l

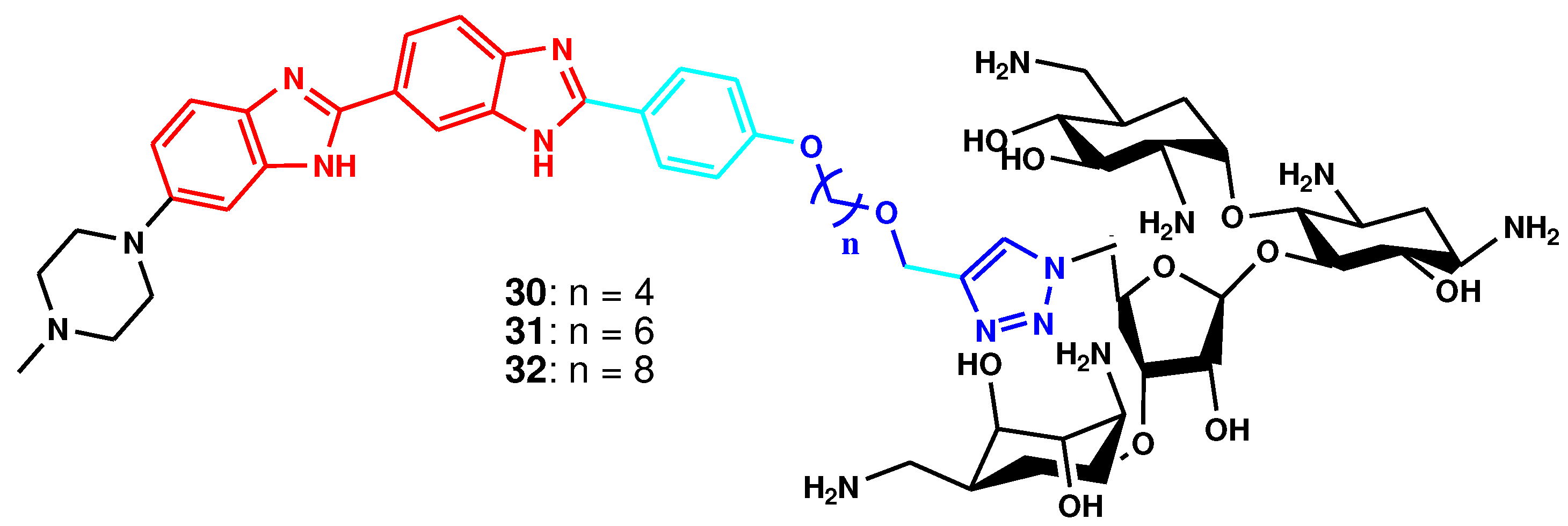

Figure 2.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,3- hybrids 30–32

Figure 2.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,3- hybrids 30–32

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 35a–35g

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 35a–35g

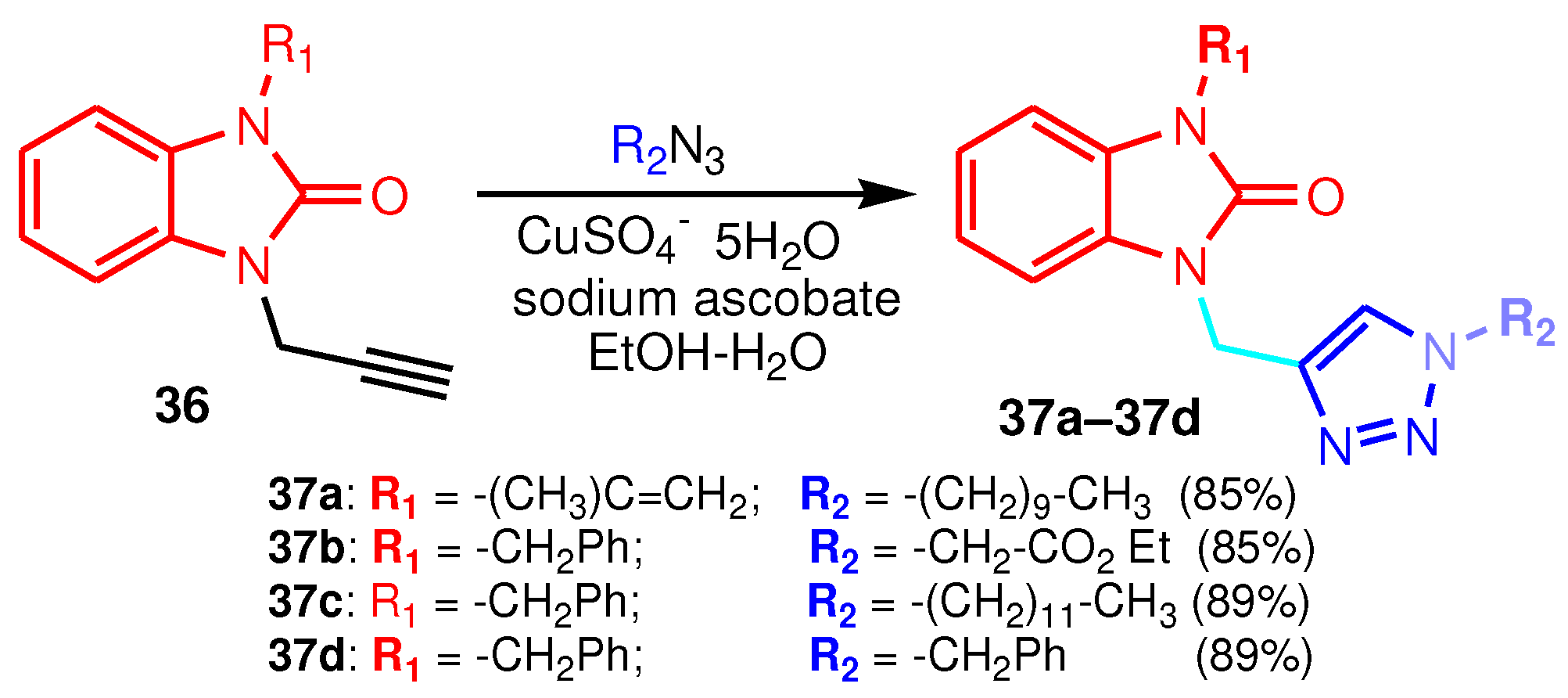

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 37a–37d

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 37a–37d

Scheme 10.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 41a–41e

Scheme 10.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 41a–41e

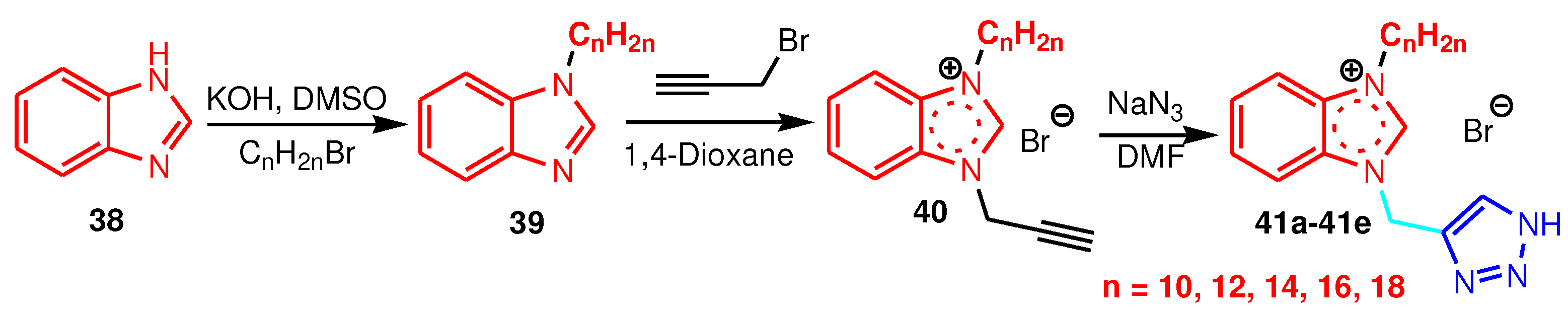

Scheme 11.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazoles 43a-43d

Scheme 11.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazoles 43a-43d

Scheme 12.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazoles 45a-45g

Scheme 12.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazoles 45a-45g

Scheme 13.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazoles 47a-47f

Scheme 13.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazoles 47a-47f

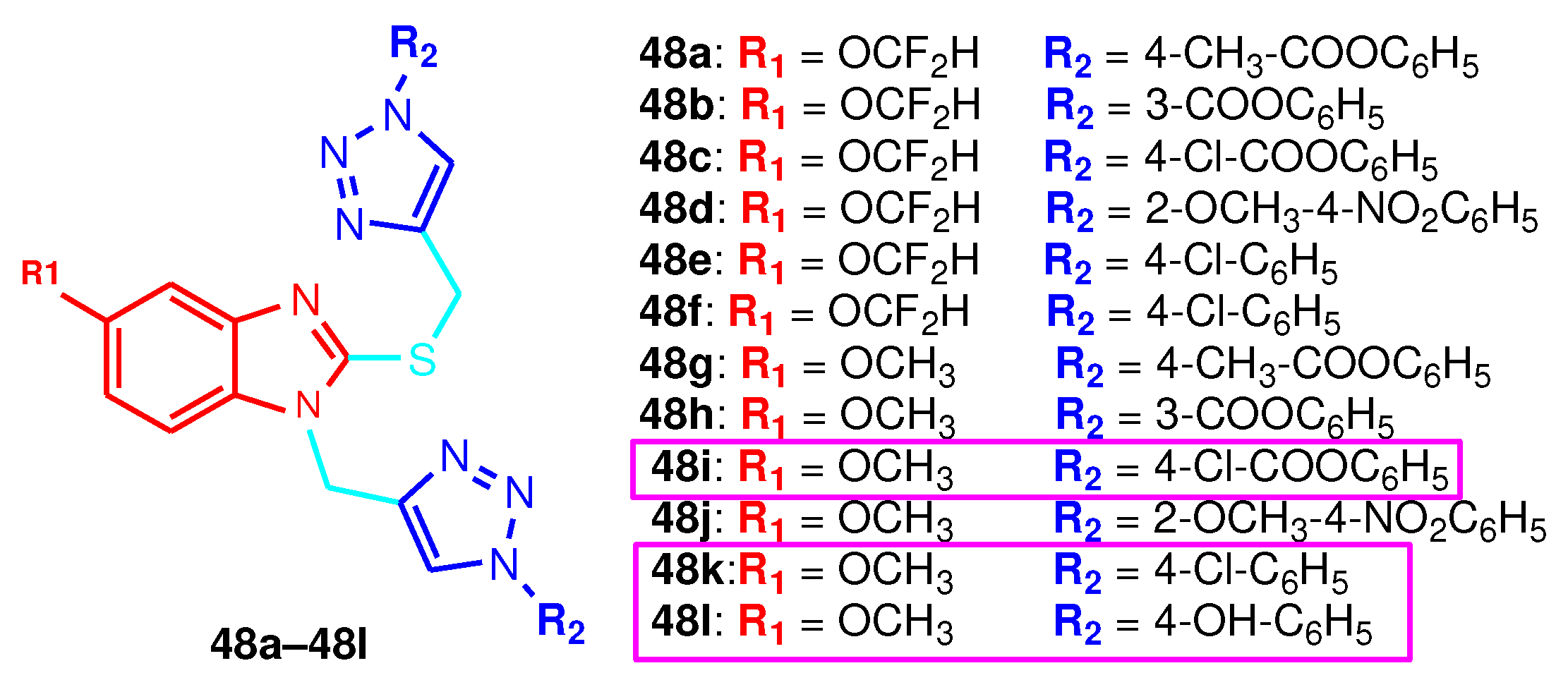

Figure 3.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 48a–48l

Figure 3.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 48a–48l

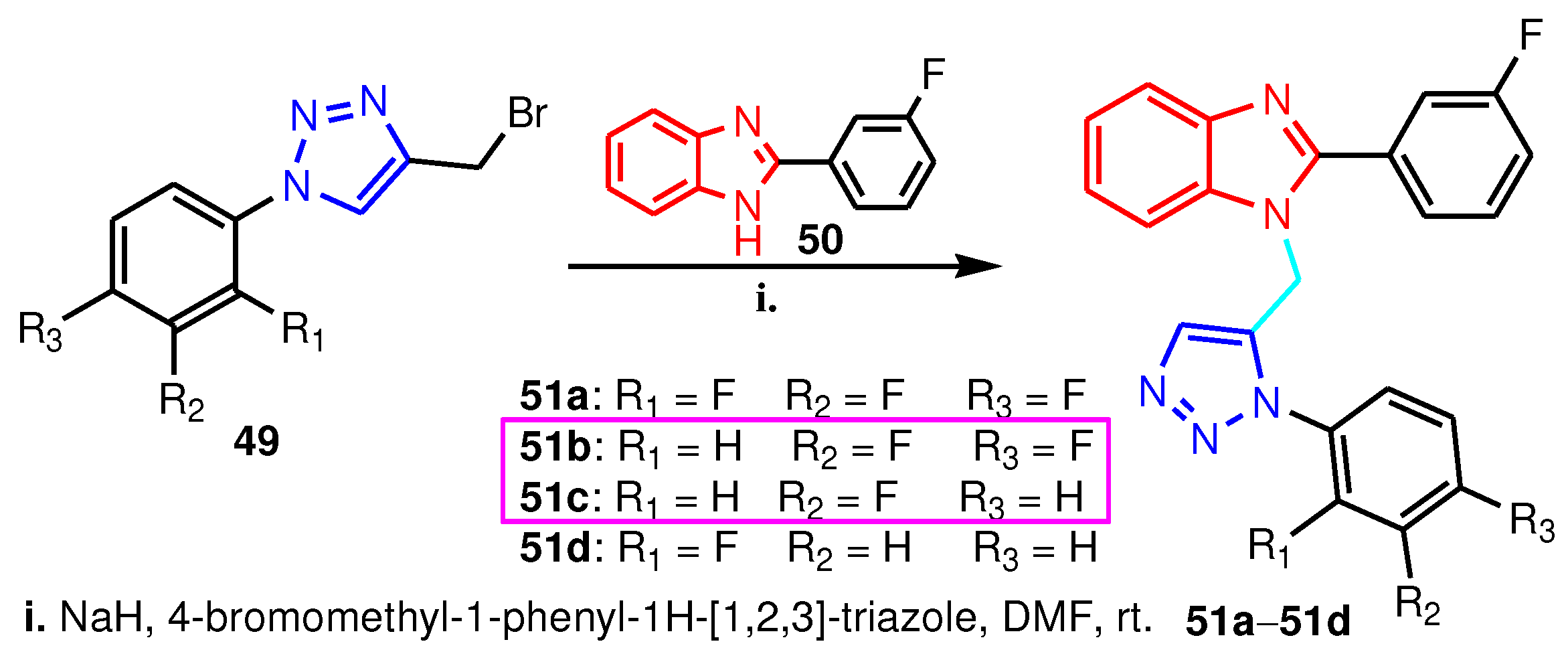

Scheme 14.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazoles 51a-51d

Scheme 14.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazoles 51a-51d

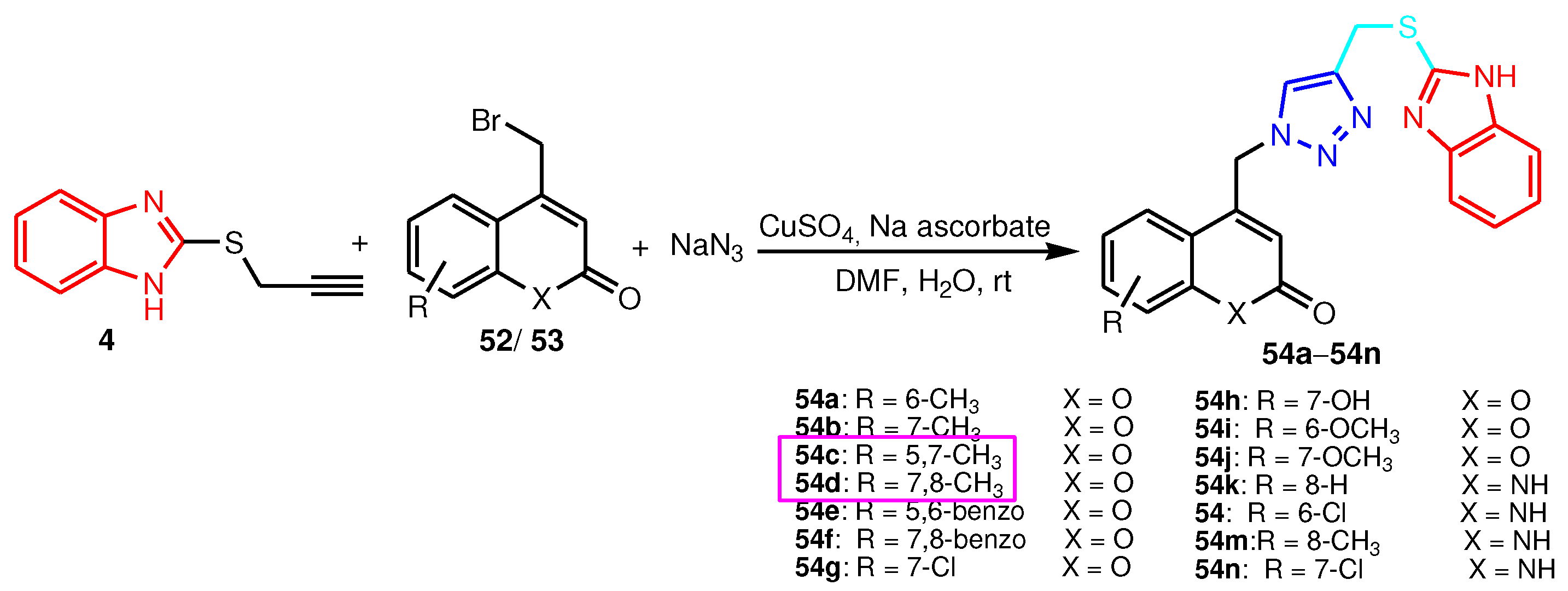

Scheme 15.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazoles 54a-54n

Scheme 15.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazoles 54a-54n

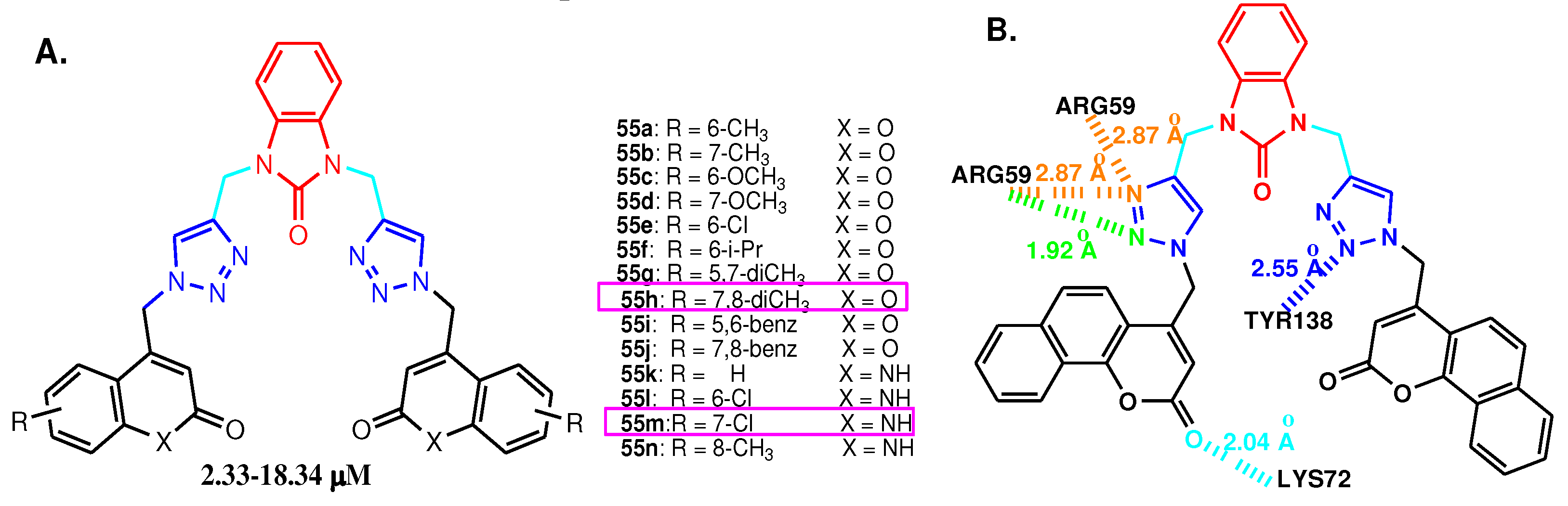

Figure 4.

A. Structure of benzimidazolone bis-1,2,3-triazoles 55a–55n. B. Representation of docked view of compound 55j at the active site of RmlC.

Figure 4.

A. Structure of benzimidazolone bis-1,2,3-triazoles 55a–55n. B. Representation of docked view of compound 55j at the active site of RmlC.

Scheme 16.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 59a-59e

Scheme 16.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 59a-59e

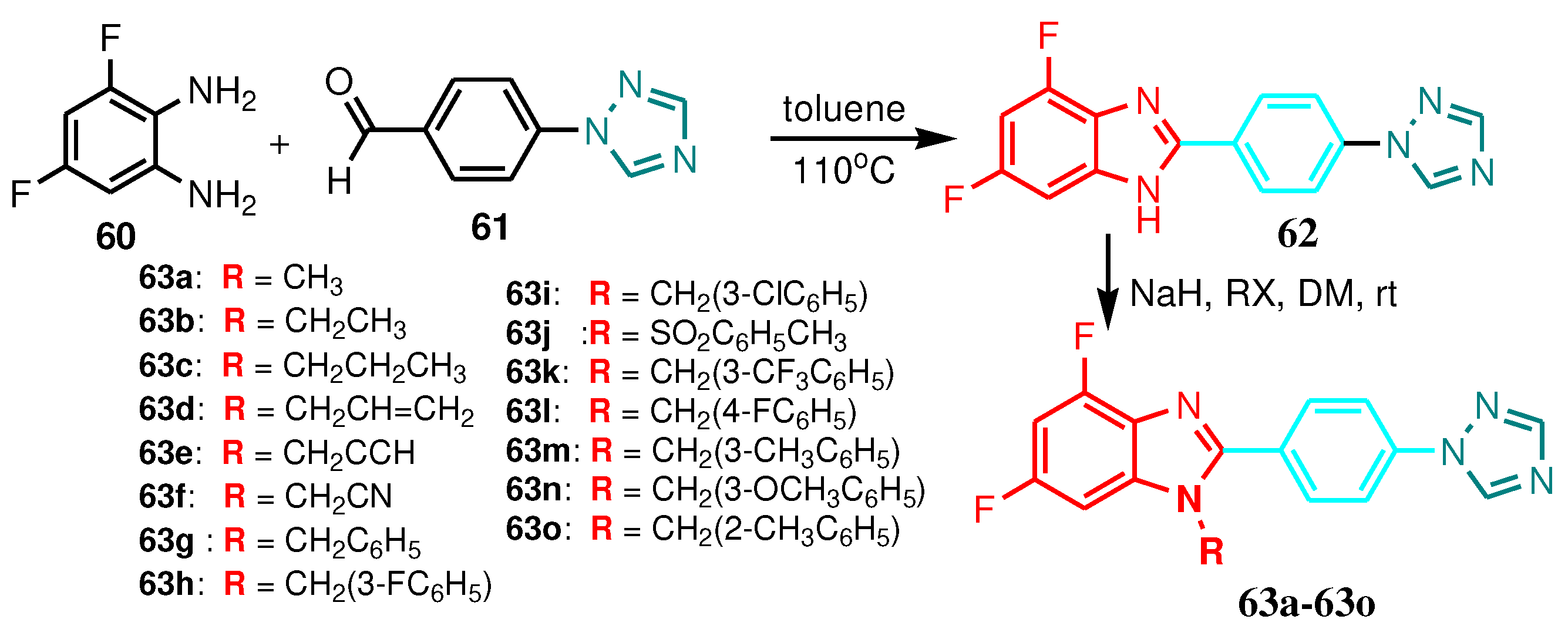

Scheme 17.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 63a-63e

Scheme 17.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 63a-63e

Figure 5.

Structure of benzimidazole hybrids 64, 65 and 70

Figure 5.

Structure of benzimidazole hybrids 64, 65 and 70

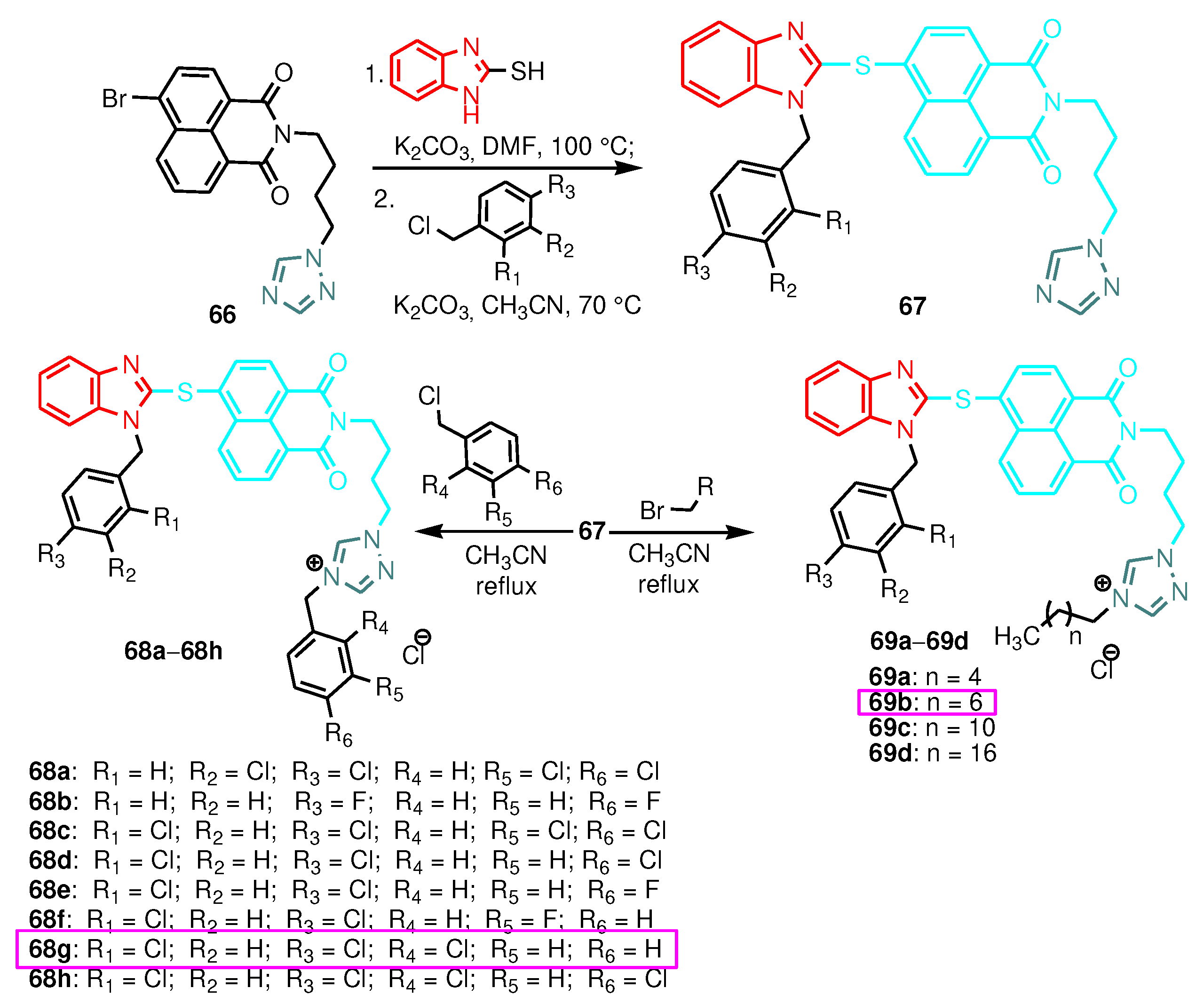

Scheme 18.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 68 and 69

Scheme 18.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 68 and 69

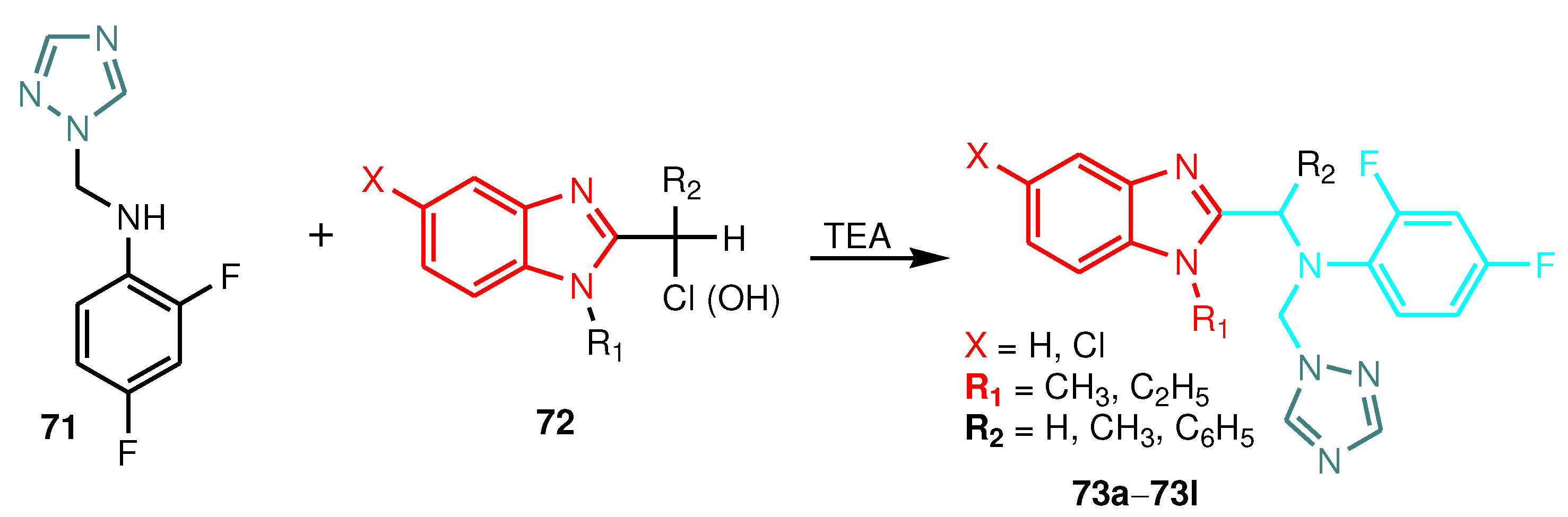

Scheme 19.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 73a–73l

Scheme 19.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 73a–73l

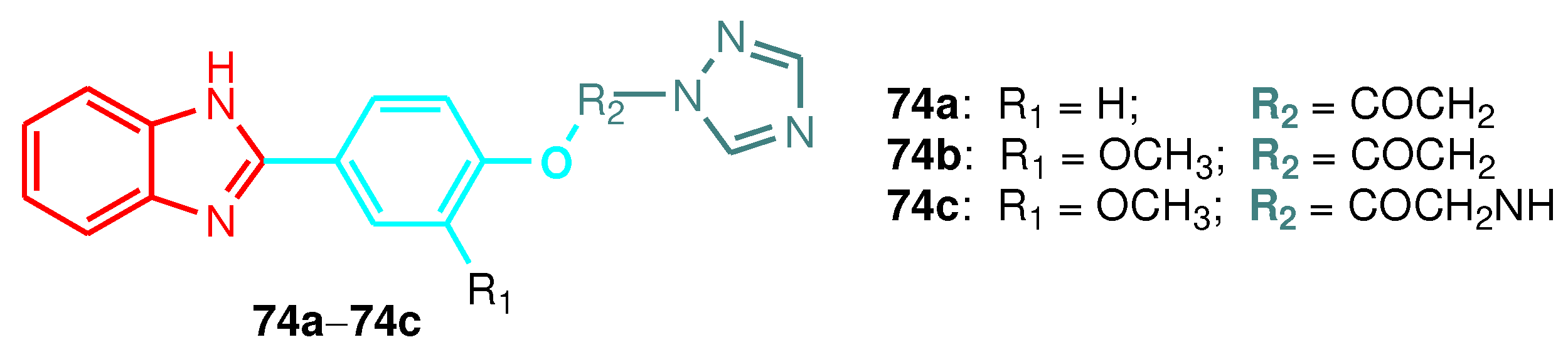

Figure 6.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 74a–74c

Figure 6.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 74a–74c

Scheme 20.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 79a–79c

Scheme 20.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 79a–79c

Scheme 21.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 85a–85e and compound 86c

Scheme 21.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 85a–85e and compound 86c

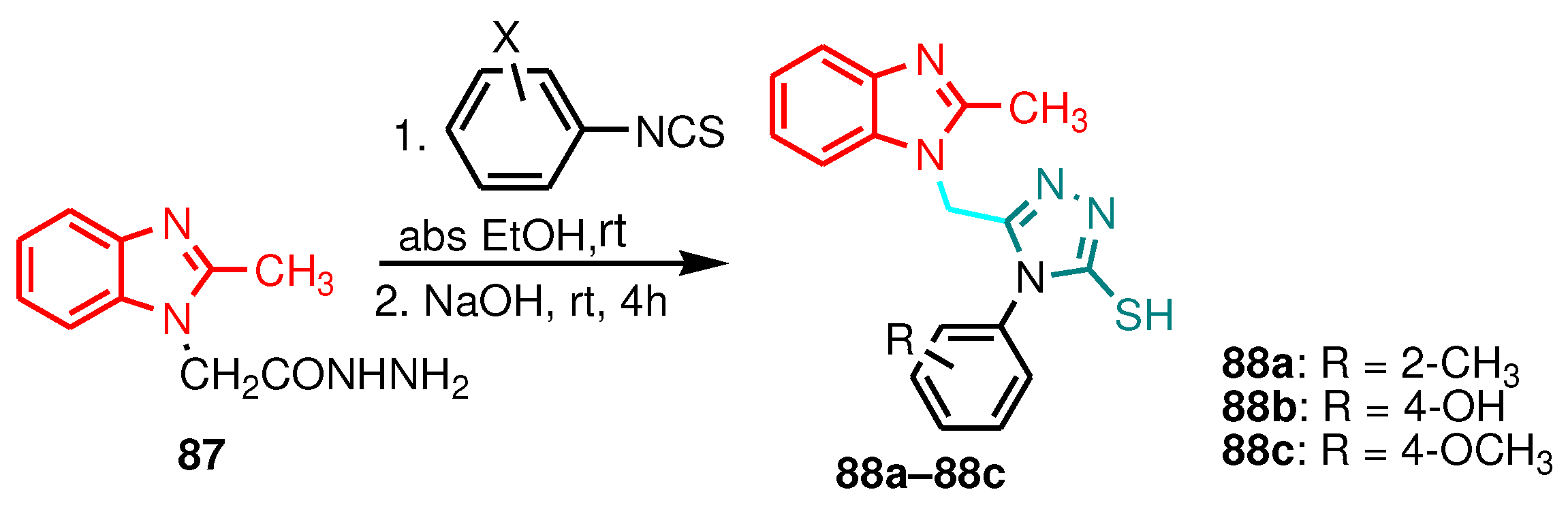

Scheme 22.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 88a–88c

Scheme 22.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 88a–88c

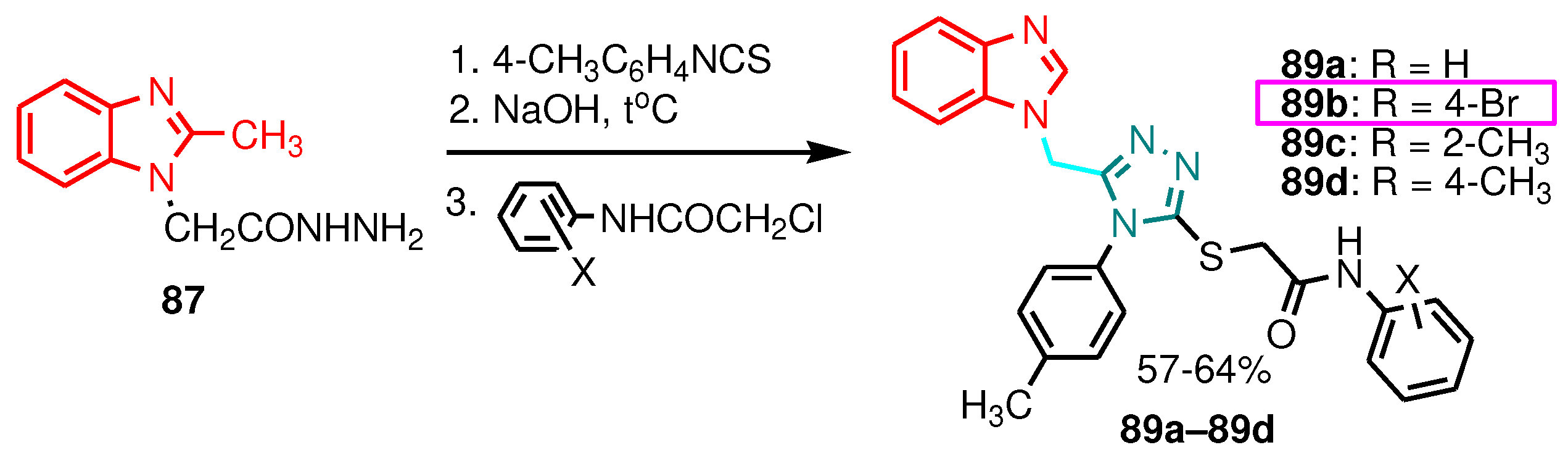

Scheme 23.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 89a–89c

Scheme 23.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 89a–89c

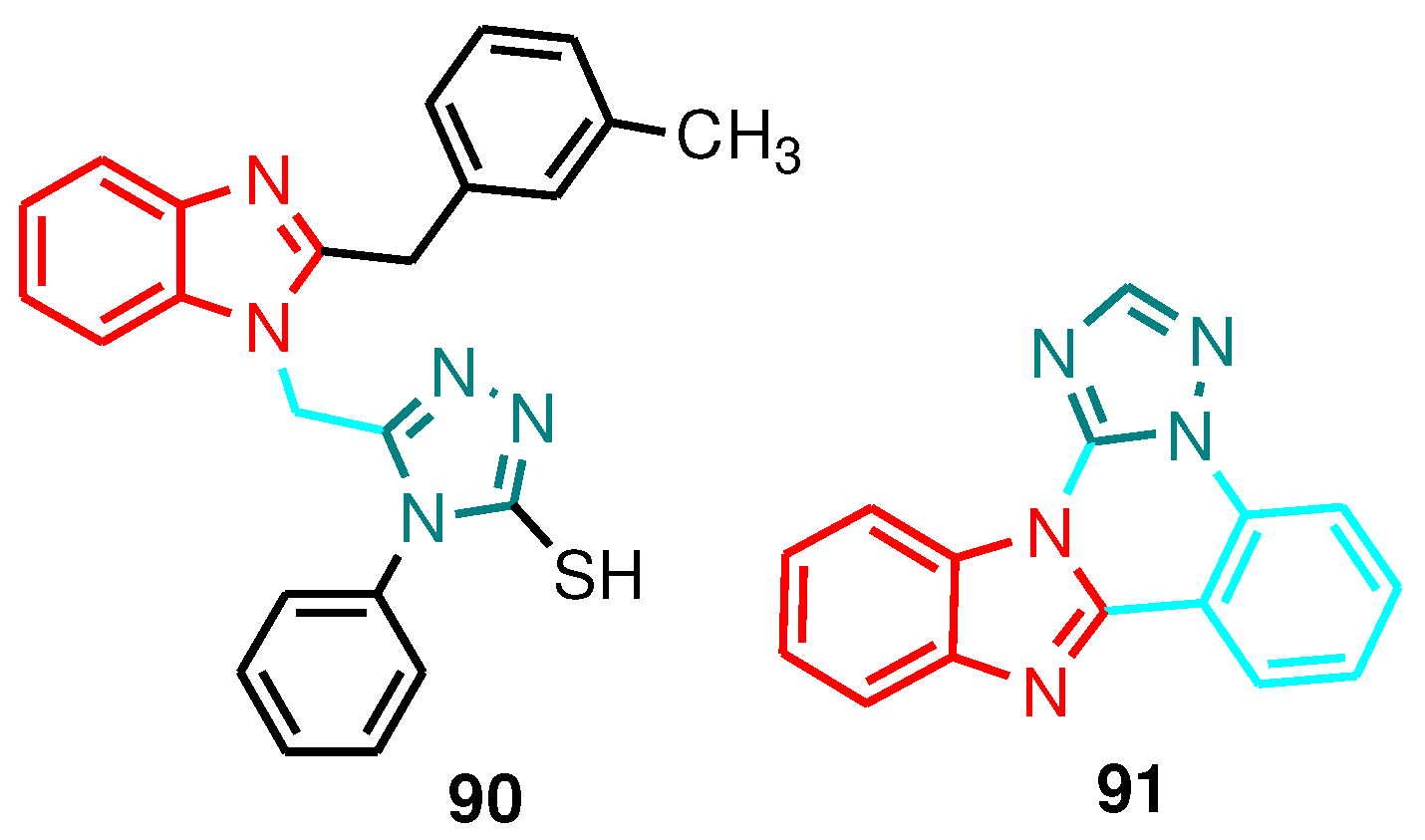

Figure 7.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 90 and 91

Figure 7.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 90 and 91

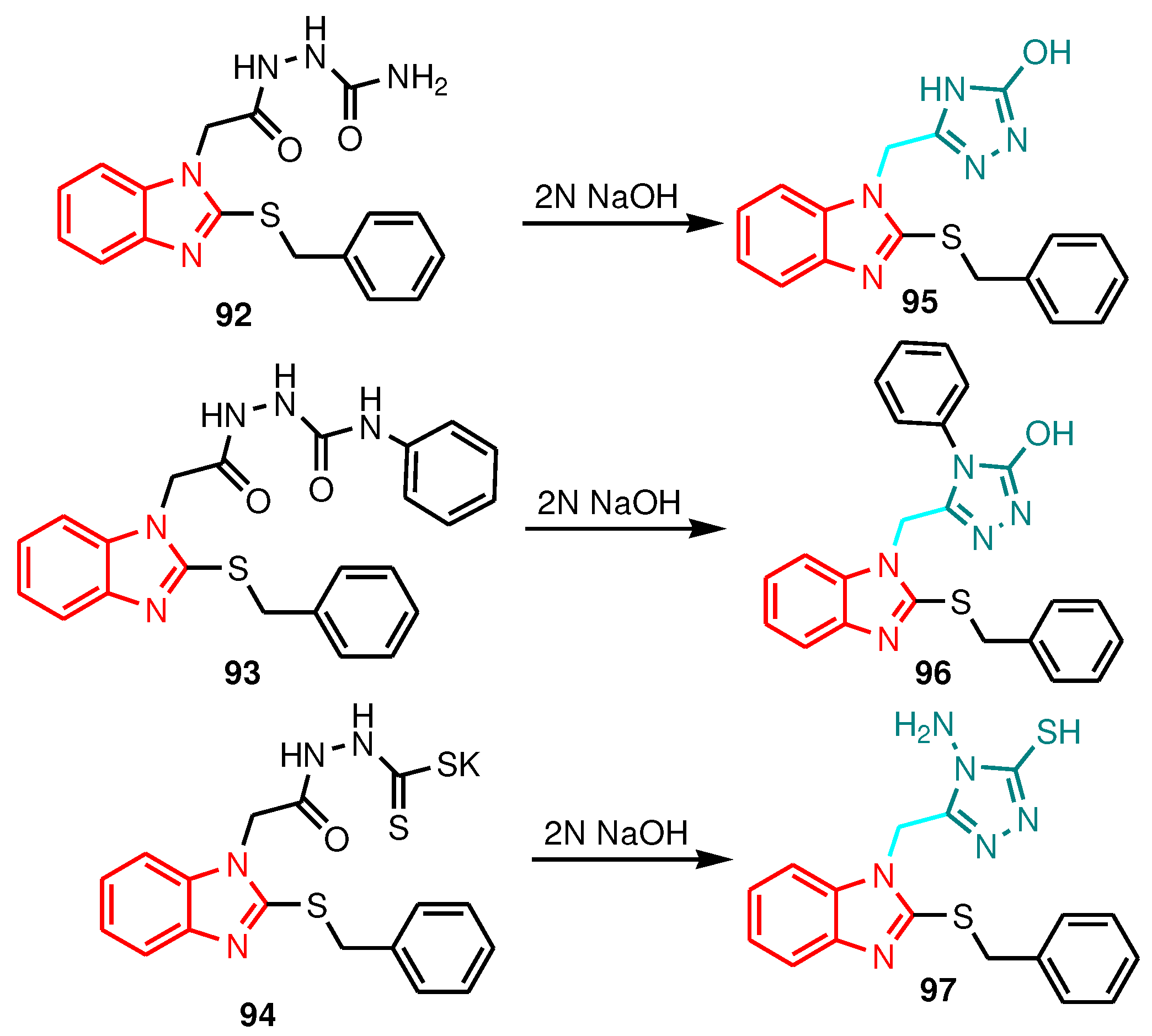

Scheme 24.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 95–97

Scheme 24.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 95–97

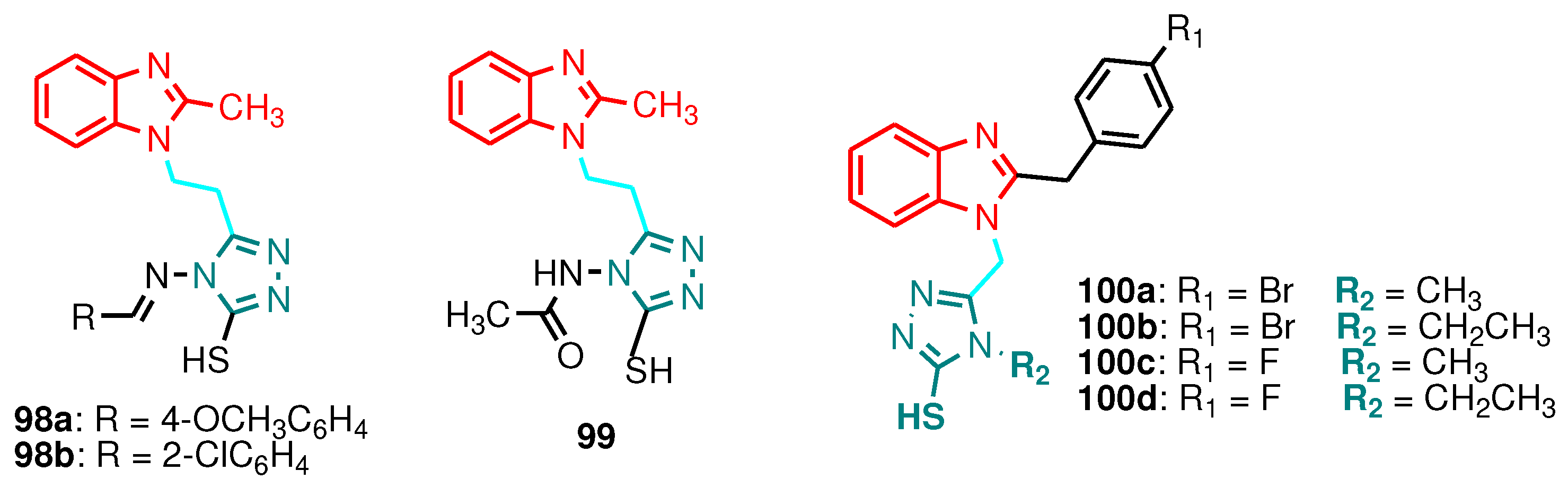

Figure 8.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 98–100

Figure 8.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 98–100

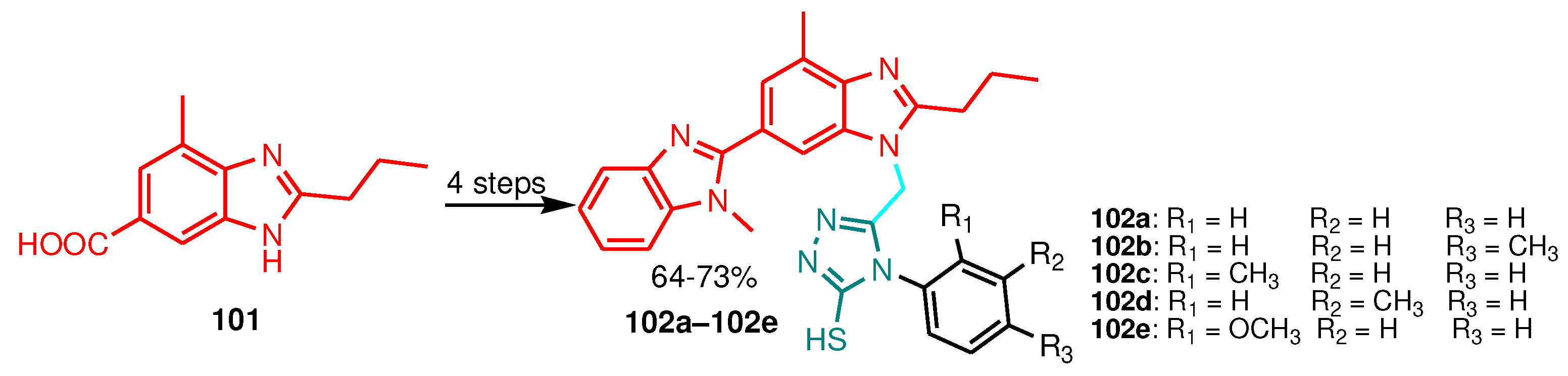

Scheme 25.

Synthesis of bis-benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 102a-102e

Scheme 25.

Synthesis of bis-benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 102a-102e

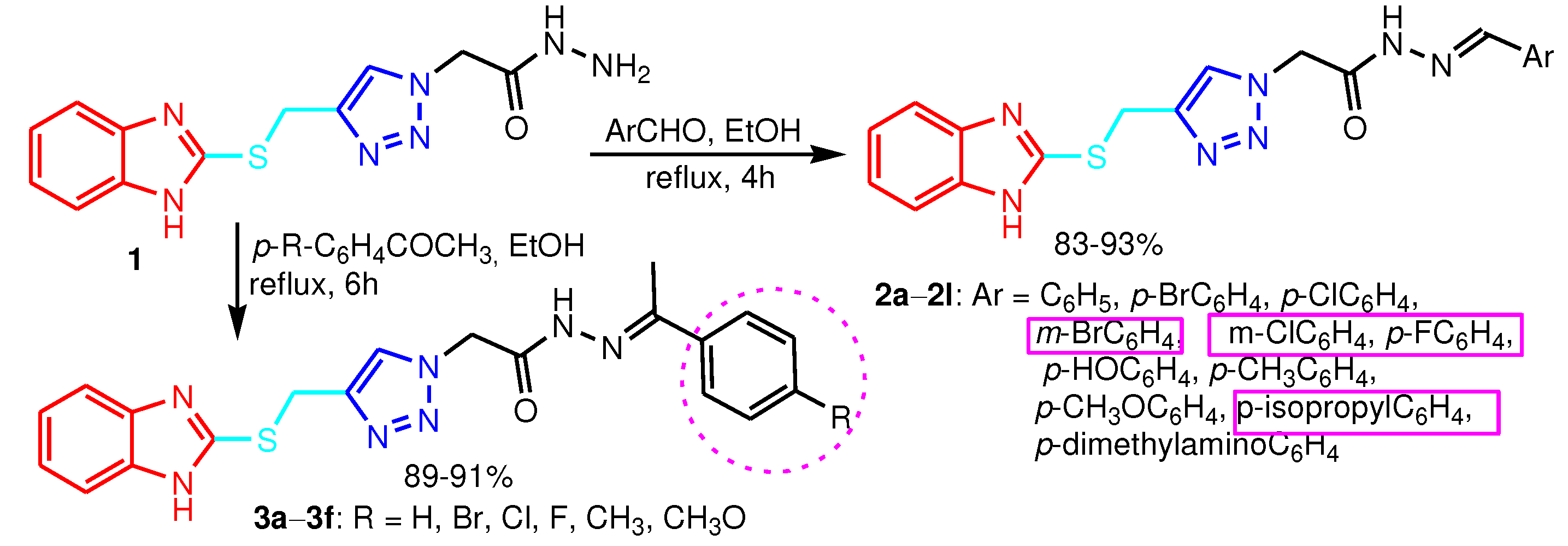

Scheme 27.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 107a-107b

Scheme 27.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 107a-107b

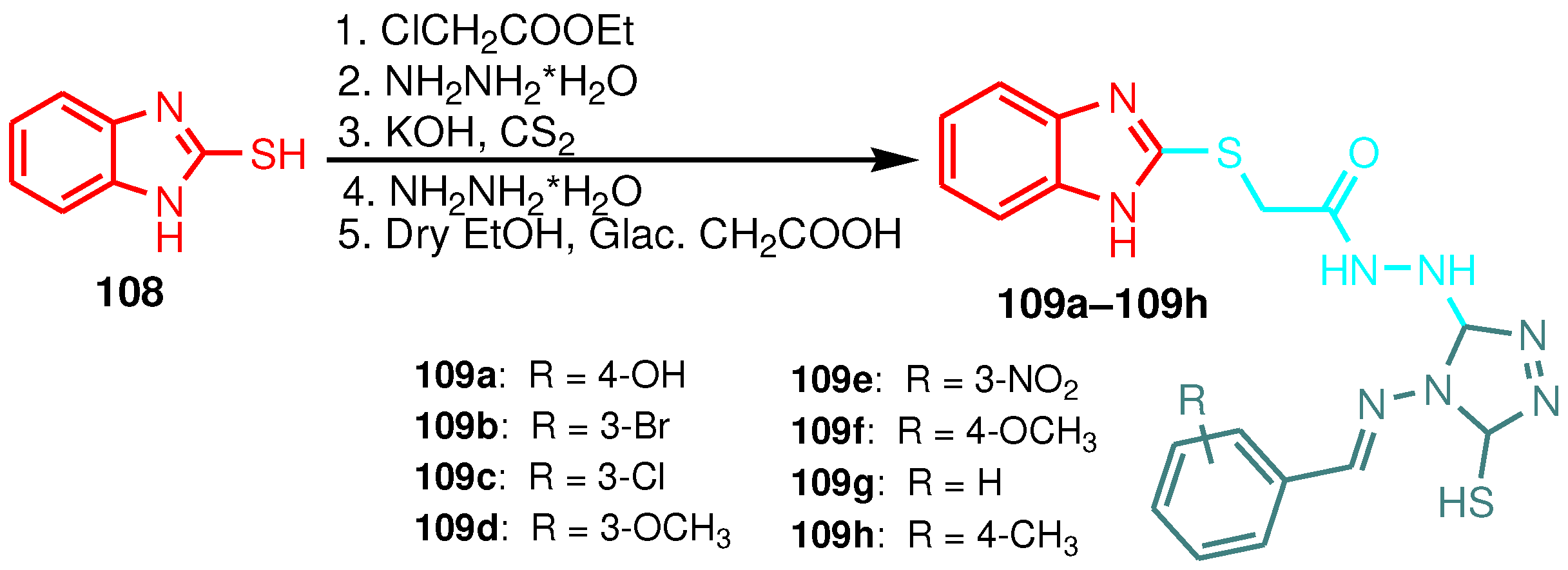

Scheme 28.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 109a-109h

Scheme 28.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 109a-109h

Scheme 29.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 111a-111s

Scheme 29.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazoles 111a-111s

Figure 9.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 112a–112i

Figure 9.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 112a–112i

Figure 10.

SAR outline of the benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 112a–112i

Figure 10.

SAR outline of the benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 112a–112i

Figure 11.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 113a–113l

Figure 11.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 113a–113l

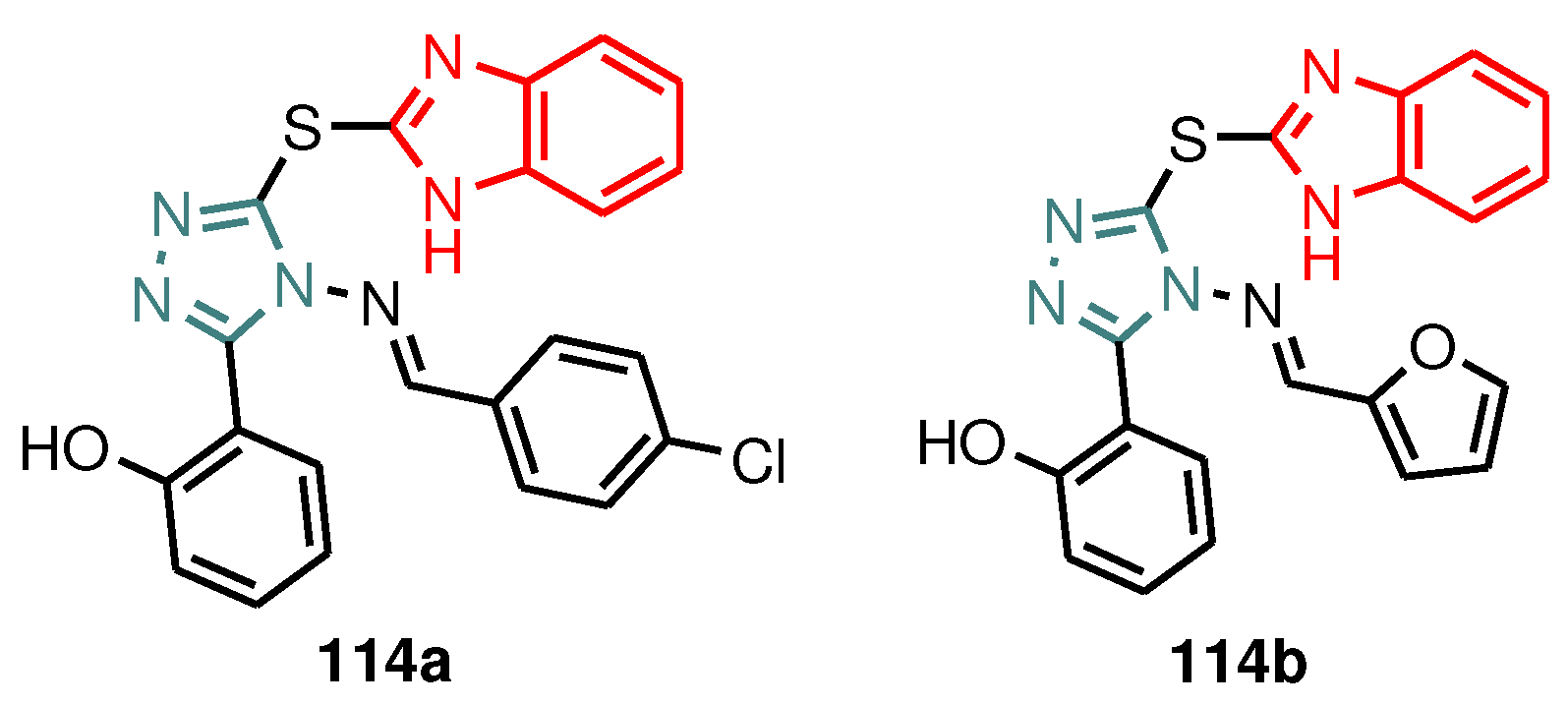

Figure 12.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 114a–114l

Figure 12.

Structure of benzimidazole-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 114a–114l

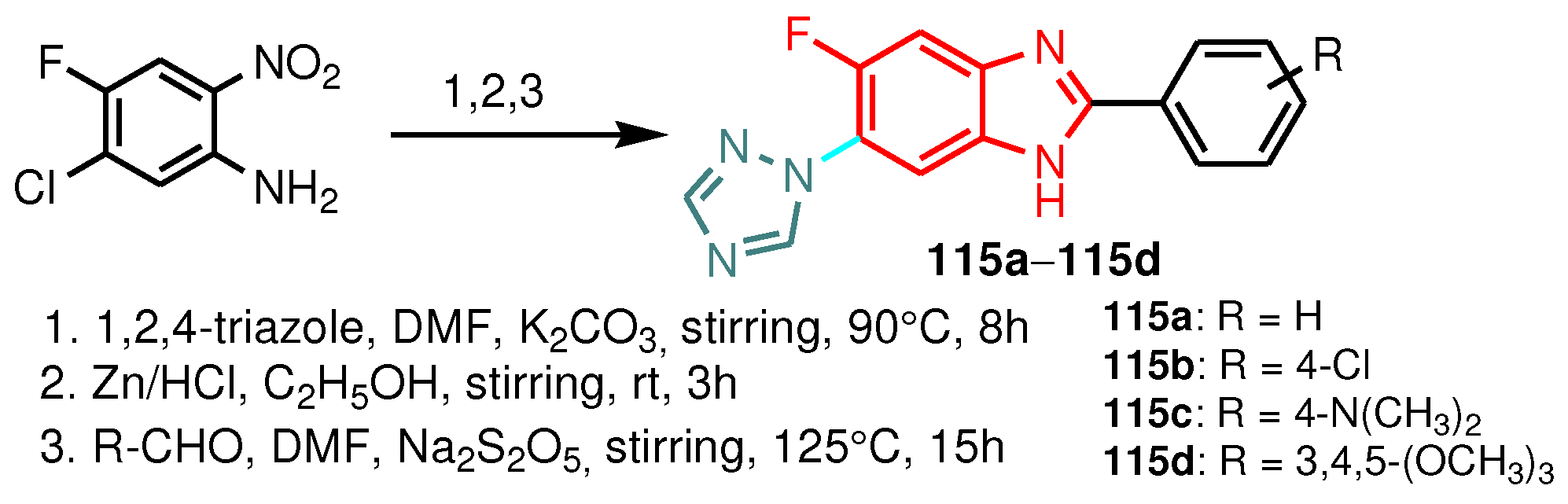

Scheme 30.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-triazoles 115a-115d

Scheme 30.

Synthesis of benzimidazole-triazoles 115a-115d

Figure 13.

Structure of antiviral benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 116 and 117

Figure 13.

Structure of antiviral benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 116 and 117

Figure 14.

Structure of antiviral benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 118–137

Figure 14.

Structure of antiviral benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 118–137

Figure 15.

Structure of antiviral benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 138–140

Figure 15.

Structure of antiviral benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 138–140

Figure 16.

Three-dimensional binding mode of compound 140 (green) at the binding interface between the Omicron S-RBD (red) and human ACE2 (blue)

Figure 16.

Three-dimensional binding mode of compound 140 (green) at the binding interface between the Omicron S-RBD (red) and human ACE2 (blue)

Figure 17.

Structure of antiviral benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrid 141

Figure 17.

Structure of antiviral benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrid 141

Table 1.

Antimicrobial screening results of compounds 6a–6f presented as MIC (μgmL-1).

Table 1.

Antimicrobial screening results of compounds 6a–6f presented as MIC (μgmL-1).

| Compound |

Gram-positive organisms |

Gram-negative organisms |

Fungi organisms |

| B.c. |

S.a. |

P.a. |

E.c. |

A.b. |

C.a. |

| 6a |

64 |

64 |

256 |

128 |

128 |

128 |

| 6b |

128 |

128 |

128 |

128 |

256 |

256 |

| 6c |

256 |

128 |

256 |

64 |

256 |

156 |

| 6d |

256 |

128 |

256 |

64 |

256 |

256 |

| 6e |

256 |

128 |

256 |

64 |

256 |

256 |

| 6f |

512 |

512 |

256 |

256 |

512 |

512 |

| Ciprofloxacin |

8 |

4 |

8 |

4 |

- |

- |

Table 3.

Antimicrobial activity of the compounds 35 in terms of MIC (µmol mL-1).

Table 3.

Antimicrobial activity of the compounds 35 in terms of MIC (µmol mL-1).

| Compound |

S. aureus |

E. coli |

B. subtilis |

S. epidermitis |

A. niger |

C. albicans |

| 35a |

0.028 |

0.056 |

0.056 |

0.056 |

0.056 |

0.056 |

| 35b |

0.031 |

0.062 |

0.062 |

0.062 |

0.062 |

0.062 |

| 35c |

0.029 |

0.058 |

0.058 |

0.058 |

0.058 |

0.058 |

| 35d |

0.060 |

0.030 |

0.060 |

0.030 |

0.060 |

0.060 |

| 35e |

0.029 |

0.056 |

0.056 |

0.056 |

0.056 |

0.056 |

| 35f |

0.026 |

0.052 |

0.052 |

0.052 |

0.052 |

0.052 |

| 35g |

0.031 |

0.026 |

0.052 |

0.026 |

0.026 |

0.026 |

| Norfloxacin |

0.020 |

0.039 |

0.039 |

0.039 |

- |

- |

| Fluconazole |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.04 |

0.020 |

Table 4.

Antimicrobial activity of the compounds 63a-63o using the agar diffusion method

Table 4.

Antimicrobial activity of the compounds 63a-63o using the agar diffusion method

| Compound |

Inhibition zone diameters using the agar diffusion method (mm) |

| S. aureus |

P. aeruginosa |

E. coli |

S. typhosa |

| 63a |

28 |

26 |

21 |

19 |

| 63b |

23 |

18 |

16 |

14 |

| 63c |

21 |

23 |

18 |

19 |

| 63d |

20 |

22 |

23 |

23 |

| 63e |

25 |

23 |

21 |

24 |

| 63f |

27 |

26 |

24 |

20 |

| 63g |

19 |

20 |

15 |

13 |

| 63h |

29 |

26 |

22 |

24 |

| 63i |

26 |

22 |

19 |

18 |

| 63j |

14 |

12 |

16 |

16 |

| 63k |

22 |

21 |

20 |

18 |

| 63l |

25 |

23 |

19 |

21 |

| 63m |

21 |

18 |

18 |

16 |

| 63n |

24 |

22 |

22 |

21 |

| 63o |

19 |

21 |

18 |

14 |

| Gentamycin |

34 |

35 |

31 |

30 |

Table 5.

ED50 values (µg mL-1) of compounds against test fungi.

Table 5.

ED50 values (µg mL-1) of compounds against test fungi.

| Compound |

F. verticillioides |

D. oryzae |

C. lunata |

F. fujikuroi |

| 74a |

35 |

50 |

28 |

45 |

| 74b |

30 |

25 |

18 |

30 |

| 74c |

16 |

12 |

10 |

15 |

| Carbendazim |

230 |

- |

- |

150 |

| Propiconazole |

20 |

25 |

22 |

21 |

Table 6.

Antimicrobial activity of compounds 88a–88c expressed as MIC in μg mL-1

Table 6.

Antimicrobial activity of compounds 88a–88c expressed as MIC in μg mL-1

| Compound |

S. aureus, |

B. subtilis |

S. mutans |

P. aeruginosa |

C. albicans |

| 88a |

NT |

NT |

16 |

16 |

32 |

| 88b |

8 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

NT |

| 88c |

8 |

16 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

| Ampicillin |

2 |

2 |

< 1 |

4 |

NT |

| Kanamycin |

2 |

< 1 |

4 |

2 |

NT |

Table 7.

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (µg mL-1)) of the compounds against fungi.

Table 7.

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (µg mL-1)) of the compounds against fungi.

| Compound |

Concentration (µg mL-1) |

Aspergillus niger |

Fusarium oxysporum |

| 89a |

50 |

50 |

- |

| 89b |

50 |

50 |

50 |

| 89c |

50 |

50 |

- |

| 89d |

50 |

50 |

- |

Table 8.

Antimicrobial activity of compounds 89a–89c

Table 8.

Antimicrobial activity of compounds 89a–89c

| Compound (800 µg mL-1) |

S. aureus |

P. aerugnosa |

B. subtilis |

A. baumannii |

C. albicans |

| 95 |

18 |

14 |

15 |

- |

10 |

| 96 |

19 |

11 |

12 |

- |

11 |

| 97 |

17 |

15 |

14 |

12 |

- |

| Amoxicillin |

33 |

32 |

33 |

- |

- |

| Fluconazole |

- |

- |

- |

- |

25 |

Table 9.

Antimicrobial activity of compounds 105a–105b and 107a–107b

Table 9.

Antimicrobial activity of compounds 105a–105b and 107a–107b

| Compound |

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (μgmL-1) |

| Gram-positive bacteria |

Gram-negative bacteria |

| B. subtilis |

S. aureus |

E. coli |

P. aeruginosa |

| 105a |

98 |

- |

52 |

- |

| 105b |

- |

- |

65 |

- |

| 107a |

75 |

105 |

62 |

- |

| 107b |

79 |

- |

72 |

- |

| Gentamycin*

|

64 |

56 |

72 |

48 |

Table 10.

Antibacterial activity of compounds s 109a-109h

Table 10.

Antibacterial activity of compounds s 109a-109h

| No |

Compound |

Zone of inhibition (mm) |

| E. coli |

S. aureus |

C. albicans |

| 1 |

109a |

15 |

13 |

18 |

| 2 |

109b |

13 |

11 |

12 |

| 3 |

109c |

17 |

16 |

14 |

| 4 |

109d |

12 |

13 |

16 |

| 5 |

109e |

13 |

17 |

9 |

| 6 |

109f |

10 |

8 |

11 |

| 7 |

109g |

8 |

11 |

12 |

| 8 |

109h |

12 |

7 |

10 |

| 9 |

Ampicilline |

24 |

25 |

- |

| 10 |

Ketokonazole |

- |

- |

20 |

Table 11.

MIC50 (𝜇g mL-1) values of compounds 111a–111s.

Table 11.

MIC50 (𝜇g mL-1) values of compounds 111a–111s.

| Compound |

C. albicans |

G. glabrata |

C. krusei |

C. parapsilosis |

| 111a |

12.5 |

6.25 |

6.25 |

12.5 |

| 111b |

6.25 |

3.12 |

6.25 |

6.25 |

| 111c |

12.5 |

6.25 |

6.25 |

12.5 |

| 111d |

6.25 |

12.5 |

6.25 |

6.25 |

| 111e |

12.5 |

6.25 |

12.5 |

12.5 |

| 111f |

6.25 |

3.12 |

3.12 |

6.25 |

| 111g |

3.12 |

6.25 |

6.25 |

6.25 |

| 111h |

12.5 |

6.25 |

12.5 |

6.25 |

| 111i |

0.78 |

1.56 |

1.56 |

0.78 |

| 111j |

12.5 |

6.25 |

12.5 |

12.5 |

| 111k |

12.5 |

6.25 |

12.5 |

12.5 |

| 111l |

6.25 |

12.5 |

6.25 |

12.5 |

| 111m |

3.12 |

3.12 |

3.12 |

6.25 |

| 111n |

3.12 |

3.12 |

1.56 |

3.12 |

| 111o |

3.12 |

3.12 |

6.25 |

6.25 |

| 111p |

12.5 |

12.52 |

6.25 |

6.25 |

| 111r |

6.25 |

3.12 |

3.12 |

3.12 |

| 111s |

0.78 |

1.56 |

1.56 |

0.78 |

| Ketokonazole |

0.78 |

1.56 |

1.56 |

1.56 |

| Floconazole |

0.78 |

1.56 |

1.56 |

0.78 |

Table 12.

Anti-JEV and anti-HSV activity of compounds 59a–59e.

Table 12.

Anti-JEV and anti-HSV activity of compounds 59a–59e.

| Compd. |

In vitro |

|

|

In vivo |

|

|

CT50

(µg mL–1) |

EC50

(µg mL–1) |

TI |

CPE

Inhibition (%) |

Dose (µg per mouse per day) |

MST

(days) |

Protection

(%) |

| Anti-JEV |

| 59a |

125 |

4 |

31 |

30 |

200 |

- |

- |

| 59b |

125 |

8 |

16 |

90 |

200 |

4 |

16 |

| 59c |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 59d |

125 |

4 |

31 |

30 |

200 |

- |

- |

| 59e |

250 |

62.5 |

4 |

50 |

200 |

2 |

10 |

| Anti-HSV |

| 59a |

125 |

62.5 |

2 |

33 |

- |

- |

- |

| 59b |

125 |

62.5 |

2 |

46 |

- |

- |

- |

| 59c |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 59d |

125 |

31.25 |

4 |

53 |

200 |

- |

- |

| 59e |

250 |

7.8 |

32 |

64 |

200 |

- |

- |

CT50 – 50% cytotoxic concentration, EC50 – 50% effective concentration, TI –therapeutic index (TI= CT50/ EC50)

CPE - cytopathic effect, MST – mean survival time |

Table 13.

RSV, BVDV, YFV, and CVB2 Inhibitory Activity of hybrids 118–137 expressed as EC50 (µM)

Table 13.

RSV, BVDV, YFV, and CVB2 Inhibitory Activity of hybrids 118–137 expressed as EC50 (µM)

| Compound |

Anti-RSV activity |

Anti-BVDV activity |

Anti-YFV activity |

Anti-CVB2 activity |

| 118 |

0.7 |

- |

- |

- |

| 119 |

2.3 |

- |

- |

- |

| 120 |

0.7 |

> 100 |

80 |

> 100 |

| 121 |

0.7 |

63 |

> 90 |

> 100 |

| 122 |

0.3 |

53 |

> 70 |

> 100 |

| 123 |

0.15 |

51 |

> 60 |

> 100 |

| 124 |

0.03 |

- |

- |

- |

| 125 |

0.7 |

- |

- |

- |

| 126 |

0.06 |

90 |

> 100 |

> 100 |

| 127 |

0.1 |

72 |

> 54 |

> 100 |

| 128 |

0.9 |

15 |

6 |

40 |

| 129 |

0.05 |

19 |

> 21 |

> 88 |

| 130 |

0.02 |

14 |

> 20 |

26 |

| 131 |

10.0 |

- |

- |

- |

| 132 |

7.0 |

- |

- |

- |

| 133 |

1.9 |

67 |

> 36 |

> 100 |

| 134 |

> 36 |

15 |

> 18 |

> 36 |

| 135 |

9 |

- |

- |

- |

| 136 |

11 |

80 |

> 45 |

> 100 |

| 137 |

23.0 |

80 |

27 |

> 83 |

| 6-Azaurine |

1.2 |

> 100 |

26 |

> 100 |

Table 14.

Antiviral activity of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 138–140

Table 14.

Antiviral activity of benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 138–140

| Compound |

CC50 (mg mL-1) |

EC50 (mg mL-1) |

Selectivity Index (SI) |

| Ceftazidime |

1045.53 |

85.07 |

12.29 |

| 138 |

1065.51 |

155.05 |

6.87 |

| 139 |

1530.5 |

306.1 |

5.0 |

| 140 |

1028.28 |

80.4 |

12.78 |