Introduction

Syringomyelia is the development of a fluid-filled cavity located within the spinal cord (SC) that can increase over time and lead to irreversible neurological damage. Lesions are usually located between C2 and Th9 but can extend up to the brainstem (syringobulbia) or descend to the conus medullaris. The most common etiology of the syringomyelic cavity is a congenital deformity of the craniocervical junction, mainly Chiari malformation (CM). However, it can also be related to prior meningitis, arachnoiditis, spinal trauma, or SC tumors, among others. In addition, idiopathic cases have also been described (1).

In syringomyelia cases with a clear etiology that obstructs the normal flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), it has been demonstrated that restoring regular CSF flow by decompressing the SC is more effective and safer than other treatments. For the remaining patients presenting idiopathic syringomyelia or persistent neurological deterioration, apart from the first line of treatment, direct intervention to drain the syrinx via different techniques is accepted as second-line treatment (2). There are four main types of direct syringomyelia treatment including simple syringostomy and three classic types of shunting: syringo-subarachnoid, syringo-peritoneal, or syringo-pleural. However, these strategies are yet to be proven superior in efficacy (3).

Syringostomy, or placing a catheter into the syringomyelic cavity, requires myelotomy and poses a significant risk of iatrogenic SC injury. Different myelotomy approach techniques for shunt placement have been described, with the dorsal root entry zone (DREZ) and the dorsal median sulcus being the most used surgical entry points. Nevertheless, each method carries specific risks of iatrogenic damage to different SC neural structures.

Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring (IONM) of the functional integrity of SC pathways is crucial to detect and prevent surgically induced injury. The available methods can be divided into monitoring and mapping techniques. Monitoring modalities, such as motor evoked potentials (MEPs), D-wave, and somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs), are used to continuously assess the functional integrity of the tracts and are a well-established tool for spine and SC surgery (4–7). Mapping techniques allow the identification of neural structures and, therefore, guide the surgeon in establishing a selective and safer entry point into the SC. In addition to neural root mapping, which is widely established, different mapping methods for SC long tracts―dorsal column (DC) (8–10), and corticospinal tract (CST) (11–15) ―have been described in the last few years. Dorsal column mapping (DCM) has become a reliable technique for intraoperative midline localization during posterior myelotomy to minimize DC dysfunction syndrome (9,10,16). All these IONM techniques have been widely described in the literature for various pathologies. However, there are few reports regarding the specific role of IONM in syringomyelia surgery, a surgical procedure that poses a high risk of iatrogenic injury. Here, we evaluate the benefits of multimodal IONM in syringomyelia surgery, including monitoring and mapping techniques, in a cohort of patients with syringomyelia. We highlight the critical role of IONM in selecting a safe myelotomy entry zone, detecting impending damage, and avoiding permanent injuries via adapting the surgical approach according to the IONM data.

Methods

This retrospective single-center study includes nine patients who underwent surgery to treat syringomyelia of different etiologies (

Table 1) with IONM between April 2016 and June 2021. One patient underwent two surgical procedures. The intraoperative neurophysiological data, neurological examination, and pre and postoperative neurophysiological evaluation were reviewed and analyzed.

Surgical procedure

A laminectomy and durotomy adapted to the lesion level were performed in all cases. Subsequently, myelotomy was carried out following two approaches, either via DREZ with the methodology described by Sindou et al., (17) or the conventional midline approach between the posterior columns (Table 1). Next, shunt placement or subarachnoid space reconstruction was performed for syrinx drainage. To reconstruct the subarachnoid space, we carried out decompressive laminectomy-adhesiolysis with limited myelotomy, syringostomy, and introduction of a small synthetic dural graft GORE® (W. L. Gore & Associates, Inc., Arizona, USA) into the stoma that acted as a ‘stent’ to avoid myelotomy reclosure; the final step was an increase in spinal canal size with a wide duroplasty (GORE®).

Anesthesia

All patients underwent general anesthesia. Upon arrival in the operating room, patients were non-invasively monitored, including blood pressure, heart rate, electrocardiography, and pulse oximetry. For neuromonitoring of anesthetic depth, a Bispectral Index™ (BIS™) Monitoring System (Medtronic Covidein, UK) was placed on the forehead. Anesthetic induction was performed with fentanyl (2 mcg/kg), propofol (2 mg/kg), and a single dose of atracurium besylate (0.5 mg/kg) as a neuromuscular blocking agent only to allow orotracheal intubation. Following orotracheal intubation, end-tidal carbon dioxide (CO2), esophageal temperature, central venous pressure, diuresis, and continuous blood pressure through the radial artery were routinely monitored to maintain the mean blood pressure between 65 - 80 mmHg. Pulmonary volume-controlled ventilation was used with a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 0.5, tidal volume of 6 to 7 mg∕kg, respiration rate between 12 and 16 breaths per minute, and a positive end-expiratory pressure of 5 mmHg was used to achieve a partial arterial carbon dioxide pressure (PCO2) of around 35 – 45 mmHg. Anesthetic maintenance was performed under total intravenous anesthesia with propofol and remifentanil to maintain BIS values between 40-60, thus not interfering with the intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring.

Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring

All neurophysiological data were recorded with an Xltek® Protektor32 (Natus Neurology, Inc.; Middleton, WI, USA), following international guideline recommendations (4,18,19). Open MEPs, SEPs, and free running-electromyography (EMG) baselines were recorded after anesthesia induction and before the skin incision. In addition, prepositional baselines were taken when needed, in which case, prepositional signals in the supine position were recorded and compared with post-positioned signals in the prone position.

Somatosensory evoked potentials

Posterior tibial nerve (PTN) SEPs were elicited by electrical stimulation at the medial malleolus. The cortical potential was recorded via cork-screw electrodes (Natus Neurology, Inc.; Middleton, WI, USA) placed on the scalp using three different derivations: Cz’-Fz, Cz’-C3’, and C3’-C4’ after right stimulation and Cz’-Fz, Cz’-C4’, and C4’-C3’ after the left stimulus, according to the 10–20 international system. Ulnar or median nerve SEPs were elicited by stimulation at the wrist and recorded at the scalp using the following derivations: C3’-Fz for the right nerves and C4’-Fz for the left ones. For stimulation, either surface or subcutaneous electrodes were used. Proximal and distal electrodes were assigned as cathode and anode, respectively. A supramaximal stimulus was applied to activate myelinated sensory axons. All SEPs were collected bilaterally. SEP alert criteria included >50% amplitude reduction of the cortical potential after ruling out technical and anesthetic considerations (18,20).

Motor evoked potentials

Transcranial electrical stimulation of the motor area (via cork-screw electrodes placed at C1/C2 or C3/C4 according to the 10-20 international system) was performed by applying an anodal short train paradigm (5-7 pulses, 250 Hz, 500 µs per pulse and suprathreshold intensities). Recording was performed via paired subdermal needle electrodes inserted in the muscles of the upper and lower extremities. At least the distal muscles of the upper and lower extremities were used bilaterally. According to the level of the surgery, different muscles were targeted, such as the trapezius, deltoids, biceps brachii, extensor digitorum, abductor pollicis brevis (APB), adductor digiti minimi (ADM), quadriceps femoris, tibialis anterior (TA), and abductor hallucis (AH). The disappearance of response was considered a major criterion and a > 80% amplitude reduction was also reported as a minor criterion, according to McDonald et al., (21).

D-wave

In addition to MEPs, D-wave was used to monitor the motor pathway. D-wave was elicited by a single electrical pulse (0.5 ms duration) delivered transcranially at C1/C2 or C3/C4 and recorded via an epidural electrode placed caudally to the lesion. If possible, another D-wave recorded via another epidural electrode placed cranially to the lesion was used as a control. A 50% amplitude reduction criterion was applied (4,6).

Electromyography

Free-running EMG of the muscles of the upper and lower extremities described above was performed bilaterally. Trains of neurotonic EMG discharges were observed and reported (22).

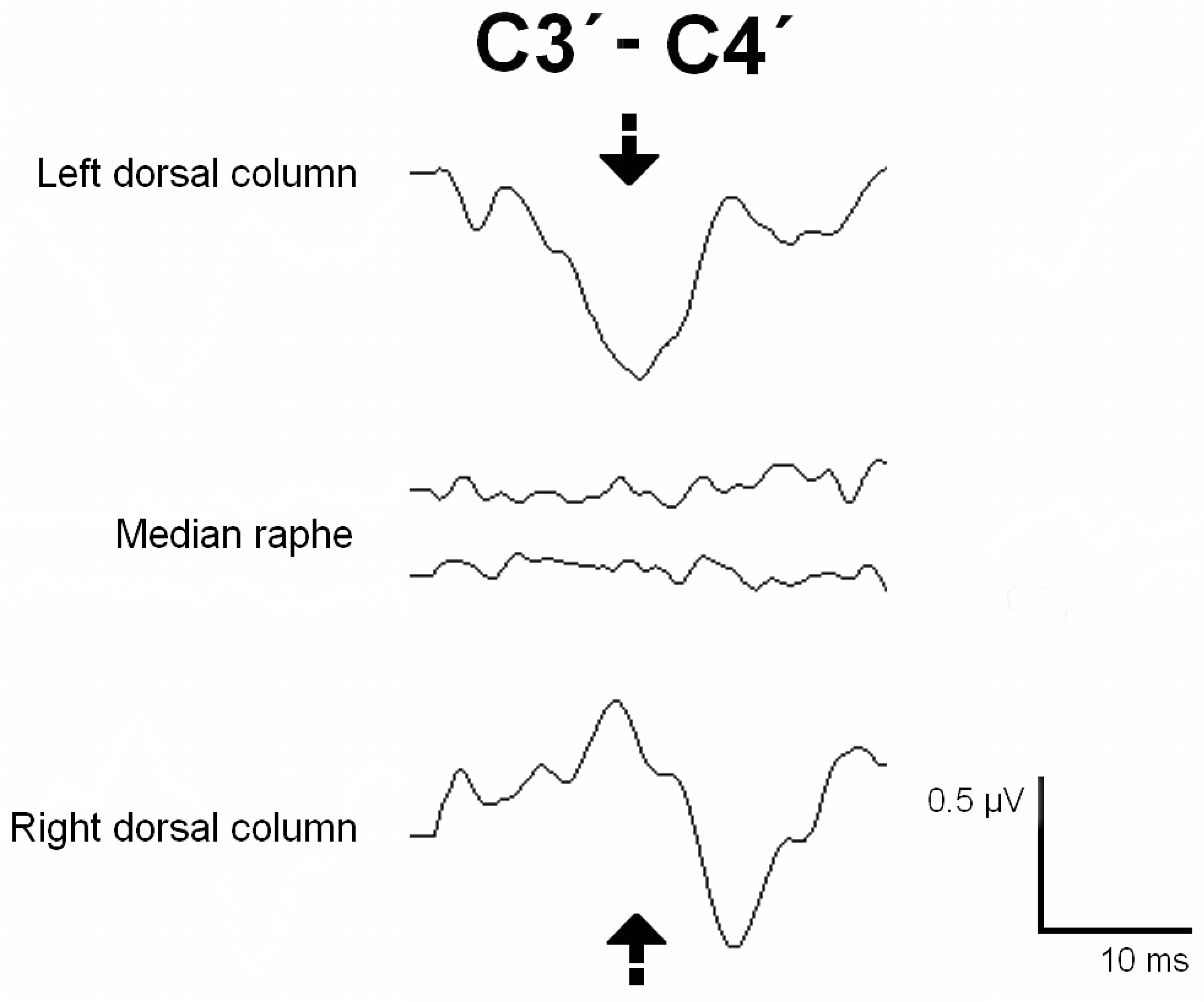

Dorsal column mapping

The DC was identified using the phase-reversal technique described by M. Simon et al., (8,9). After the SC was exposed, electrical stimulation was applied with a hand bipolar probe to the SC. Cortical recording was performed with cork-screw electrodes placed on the scalp at C3’-C4’ (10-20 international system). A positive cortical peak was recorded when the left DC was activated, and its specular image was observed when stimulating the right DC. However, no cortical response was obtained when the median raphe or DREZ was stimulated. Therefore, these areas could be marked as safe entry zones for the myelotomy.

Root mapping

After the nerve roots were exposed in the surgical field, these were electrically stimulated with a monopolar hand-held probe for identification and functional assessment of the root. The stimulated root elicited either a compound muscle action potential (CMAP) or an H response in the innervated muscles.

Other techniques

Additionally, control of the degree of peripheral relaxation was performed by train of four (TOF) neurography with PTN stimulation at the internal retro malleolar level and the CMAP recorded in the abductor hallucis muscle. Finally, the recording of three bipolar EEG channels was performed to control the depth of anesthesia.

Results

Ten surgical procedures were performed on nine patients with syringomyelia (two women and seven men, with a median age of 58 years, range: 31-76). Demographics, syringomyelia etiology and topography, preoperative examination, IONM events, and outcome for each patient are detailed in

Table 1. Four patients presented post-traumatic syringomyelia. One patient developed persistent syringomyelia secondary to Chiari malformation Type 1, despite posterior fossa reconstruction (23). In one patient, the syringomyelia was related to a spinal hemangioblastoma. In the remaining three patients, the syringomyelia etiology was a spinal arachnoid cyst, meningitis, and idiopathic. Cases 3 and 8 of

Table 1 correspond to two surgical procedures performed three years apart (2018 and 2021) on the same patient with post-traumatic syringomyelia due to a malfunction of the implanted shunt.

Mapping techniques were performed in all patients prior to the myelotomy incision for syrinx access. The dorsal nerve roots were stimulated and identified in the seven cases in which the myelotomy was performed through the DREZ. DCM was performed in four cases with DCs successfully identified in three. Negative mapping was obtained when the median sulcus was stimulated in Cases 5 and 10 and the DREZ in Case 6. In Case 9, no responses were obtained, correlating with the presurgical damage to the DC at that level. After DCM, SEPs were continuously monitored during myelotomy in all cases; no significant changes were observed.

A midline myelotomy was carried out in three cases, and a DREZ myelotomy in seven. A shunt for syrinx drainage was used in eight cases: five had a syringo-peritoneal shunt and the remaining three had a syringo-pleural shunt. Subarachnoid space reconstruction using a GORE® patch was performed in two patients.

MEP baselines were obtained before surgical positioning in five cases (Cases 5, 6, 8, 9, and 10). In one case, bilateral loss of MEP responses—affecting muscles of the upper and lower extremities—was observed when the patient was placed in the prone position, which was recovered after adjustment of the neck position. No changes between pre- and post-positional recordings were observed in four cases. MEPs from distal muscles to the surgical entry point were obtained in all cases. In Case 4, MEPs from the lower extremities were bilaterally absent at baseline. Therefore, distal upper extremity muscle MEPs were used as distal controls at the surgical level. Monitorable and bilateral SEP responses from the upper extremities were present in nine cases. SEPs were absent at baseline from the lower extremities in three cases bilaterally and three unilaterally, correlating with the findings of preoperative neurophysiological examinations (

Table 2). D-wave recordings distal to the surgical level were recorded in two patients (Cases 5 and 7) with no significant changes being observed throughout the surgical procedure.

All monitored modalities remained stable throughout the surgery in six cases, correlating with no new postoperative neurological deficits. In two cases, significant attenuation or loss of MEPs was observed and recovered after a corrective surgical maneuver was applied. MEPs were preserved at the end of the surgery and no new postoperative deficit was observed. In two cases, a significant MEP decrement was noted, which did not recover by the end of the surgery. Both patients developed new postoperative motor deficits. No significant intraoperative SEP decrement was observed. In one patient (Case 5), a transitory EMG alert was reported, consisting of a long train of neurotonic discharges observed in the free-running EMG of the muscles corresponding to the segmental level of the surgery. The surgical plan was adjusted and there was no postoperative deficit.

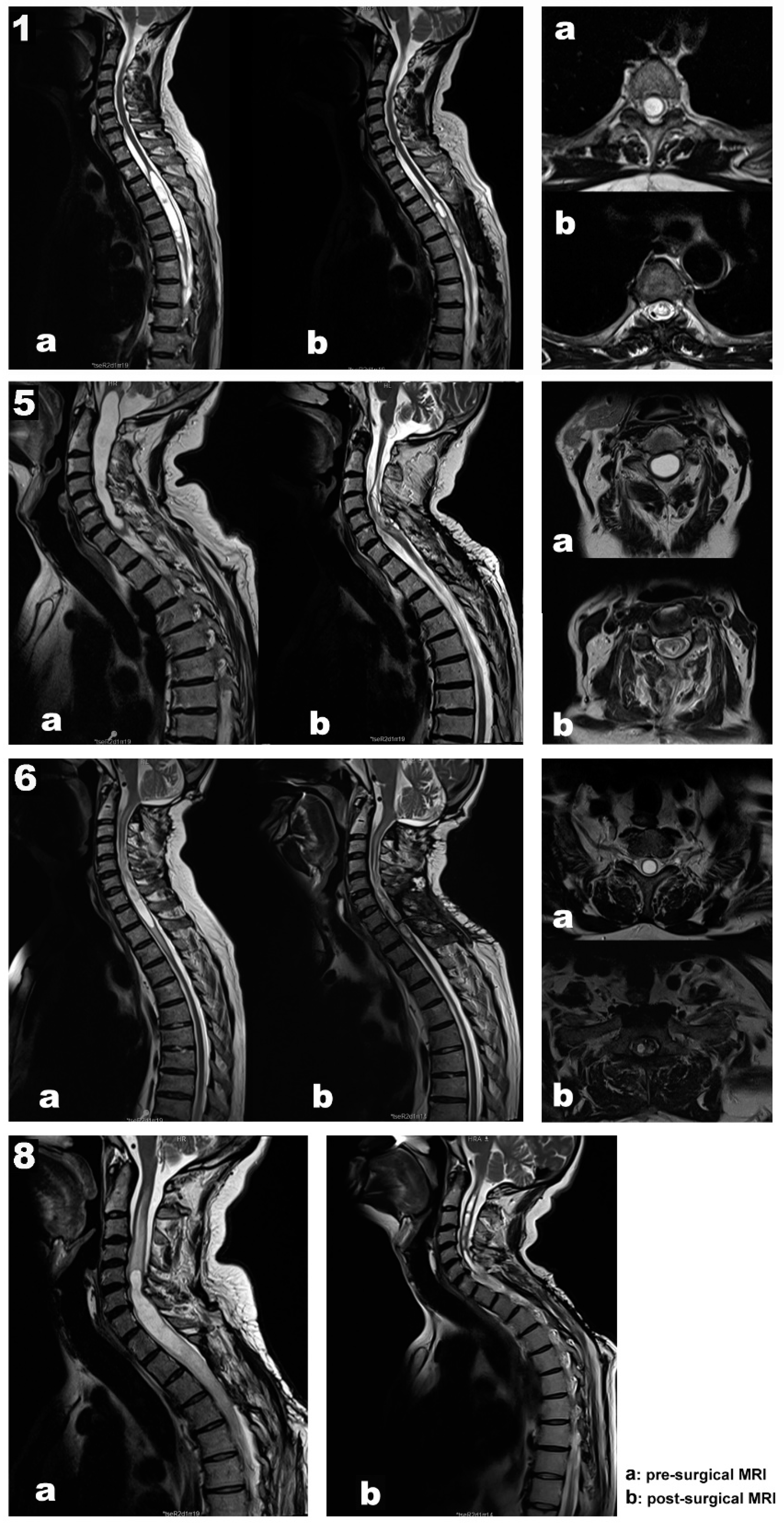

Our data support a positive and negative predictive value of 100 % for MEPs, SEPs, and EMG. In addition, in all patients, the length and diameter of the syringomyelic cavities were reduced in the follow-up MRI performed six months after surgery (

Figure 1, images b).

Illustrative cases

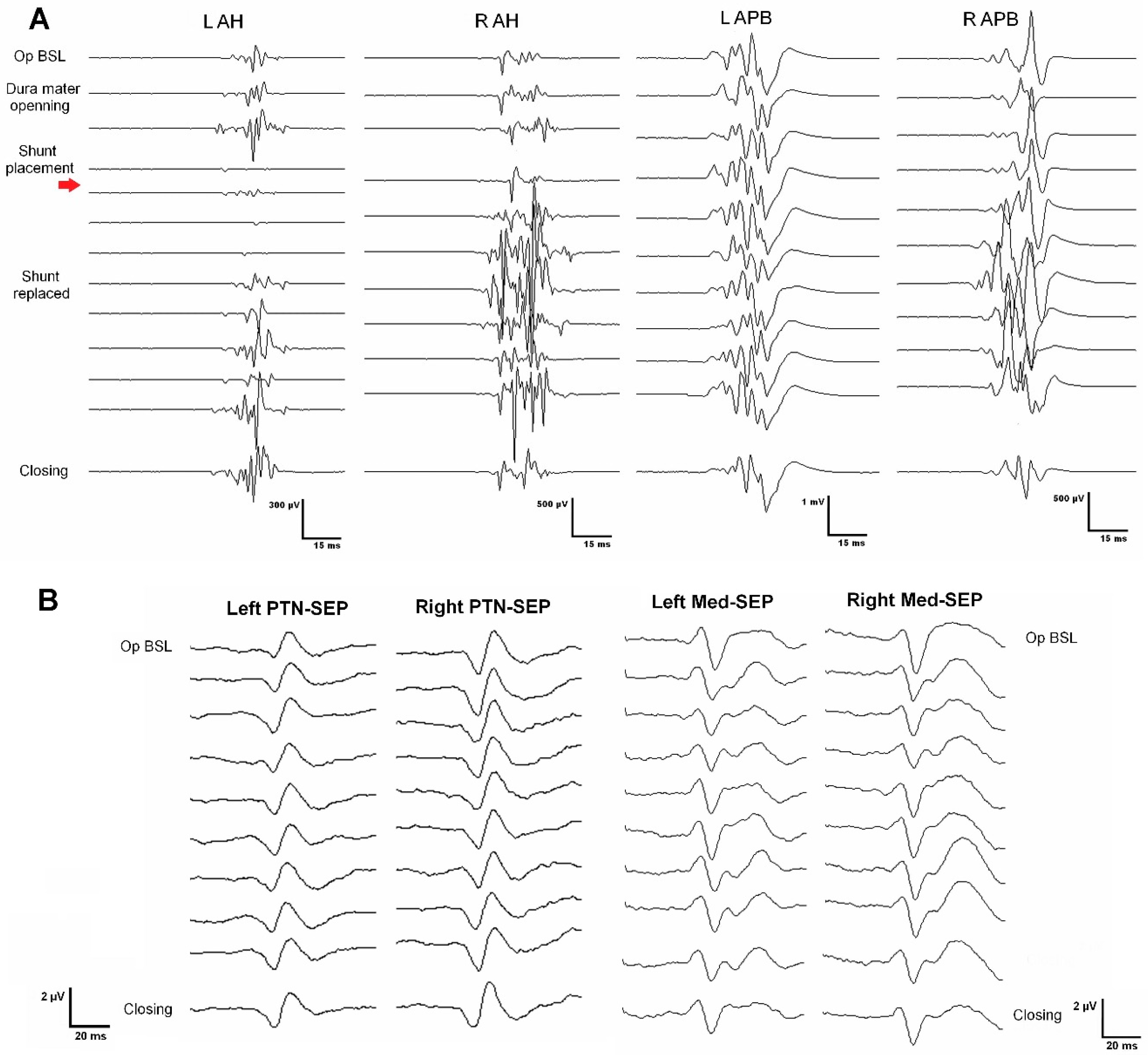

Case 1. A 67-year-old woman, independent for daily-life activities, presented with post-traumatic syringomyelia—falling from a horse when she was 30—at the Th2-Th6 segments (

Figure 1. Top panel, images a). She referred back pain of about seven years of evolution and associated loss of sensitivity and strength in the left lower extremity in the last year. At surgery, MEPs and SEPs from the four extremities were present at baseline. After laminectomy, a left DREZ myelotomy was performed at the Th4-Th5 segment. A syringo-peritoneal shunt was placed. During shunt placement, a significant reduction of more than 80% in amplitude and near-complete loss of left distal MEP (AH) was observed and reported. After slightly repositioning the shunt, the left AH MEP amplitude recovered. No changes were observed in the contralateral muscles. Bilateral PTN SEPs remained stable (

Figure 2). The patient showed symptoms of improvement postoperatively, and the neurophysiological test showed no damage to the CST (

Table 2).

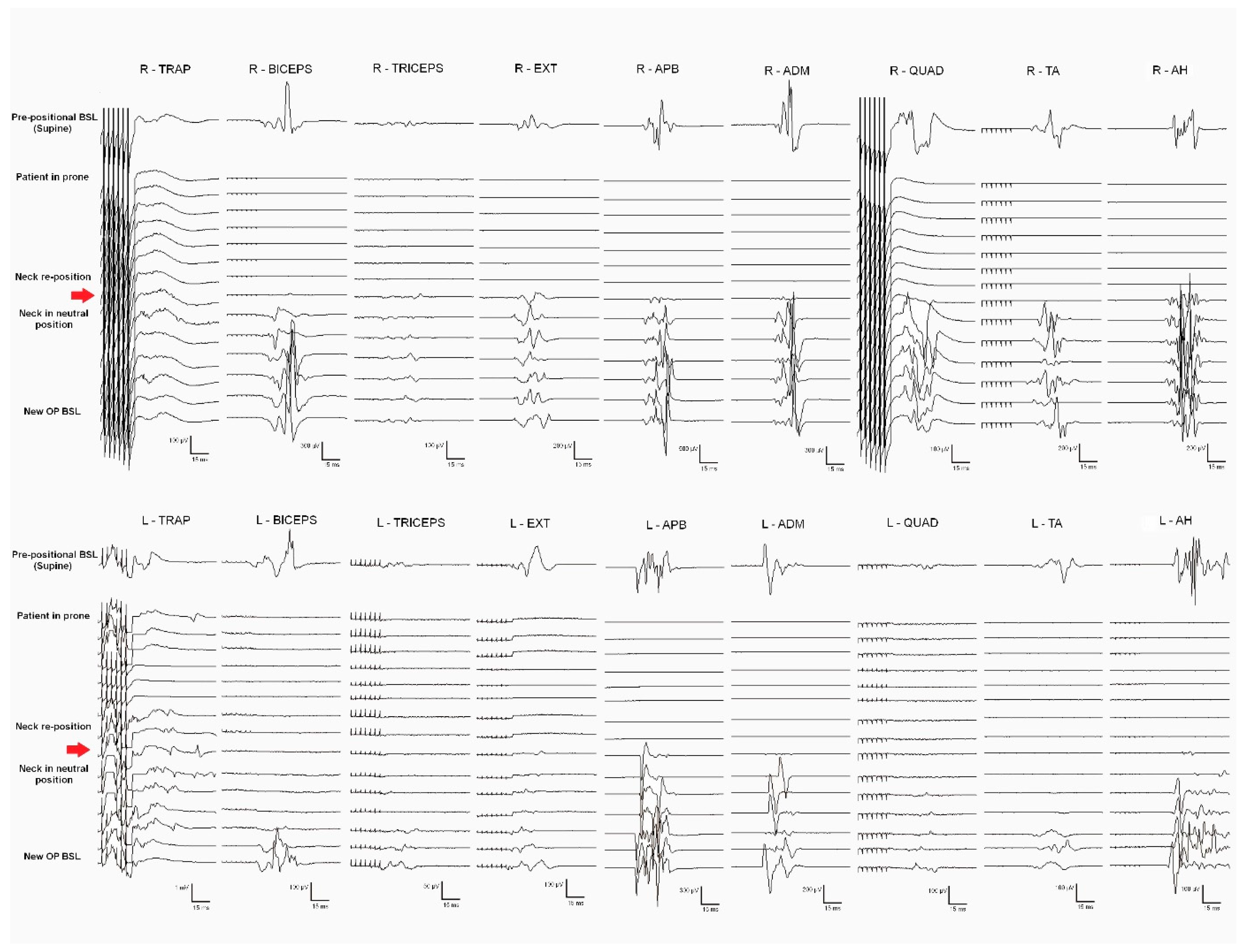

Case 5. A 70-year-old man presented with syringobulbia and central SC edema, which extended to Th1, associated with a spinal hemangioblastoma (Figure 1. Second panel, images a). Clinically, the patient presented with progressive proximal paresis in the four extremities, especially the right upper extremity. In addition to the neurological impairment, neurophysiological tests showed acute radicular/anterior horn affectation. A moderate-severe axonal loss was associated with the right C8-Th1 segments, with minimal repercussion on the left side at the same level. Also, we found mild involvement of the DC pathway for the upper limbs and right lower limb and mild impairment of the pyramidal tract for the left lower limb, with normality for the right lower limb and both upper limbs.

General anesthesia was induced and prepositional baselines were recorded while the patient was supine. Sensory and motor pathways of the SC, as well as segmental metameres, were intraoperatively monitored. Monitorable responses were observed in all muscles recorded (trapezius, biceps brachii, extensor digitorum, APB, ADM, quadriceps femoris, TA, and AH, bilaterally). After the patient was turned to the prone position, an immediate loss of MEPs from all muscles (except the bilateral trapezius) was observed. The surgical team modified the neck flexion, fixing the neck in a neutral position; MEP responses fully recovered after neck repositioning (

Figure 3). New baselines were taken before the skin incision.

A C5-Th1 laminectomy was performed, and after the dura mater was opened, an epidural catheter was placed caudally, obtaining a good-quality D-wave. DCM was performed to identify the DCs and the median raphe (

Figure 4). The entire myelotomy area was tested longitudinally to find a safe entry zone. During the myelotomy, the PTN SEPs remained stable. The cavity was explored and the possible hemangioblastoma was coagulated. A long train of EMG discharges was observed during catheter placement in the right extensor and triceps muscles. The catheter was removed, and a surgical break was given until the EMG discharges stopped. After shunt replacement, another train of EMG discharges was observed in the same muscles. The shunt was finally removed, and the surgical plan modified. The subarachnoid space was reconstructed with a GORE® patch. The SEPs, MEPs, and D-waves were stable during the whole procedure. The patient woke up with no new neurological deficits and showed proximal strength improvement in the upper and lower extremities. The postoperative neurophysiological test showed CST conduction stability and improvement in the degree of denervation at the right segmental level of the surgery (

Table 2).

Case 6. A 61-year-old man presented a Chiari malformation type 1 that required posterior fossa reconstruction 13 years ago. Even though a new pseudo cisterna magna was created, the MRI showed persistent cervical-dorsal syringomyelia (Figure 1. Third panel 3, images a). Two years before surgery, the patient presented clinical deterioration, with spastic paraparesis, hyperreflexia in both lower extremities, positive Babinski sign, and a dorsal column syndrome with positive Romberg. In the last few months, the patient used a wheelchair to move around both inside and outside the home, having difficulties to maintain standing balance. In the left upper limb, there was global paresis with a muscular strength of 3 out of 5, more accentuated in the extensor muscles of the hand and fingers with marked amyotrophy of the thenar and hypothenar eminences. MEPs and SEPs from the four extremities were present at baseline. The patient’s positioning was monitored, establishing prepositional MEP and SEP baselines while the patient was supine. No significant changes were observed in the prone position. A laminectomy at the C7-Th1 level was performed. After the dura mater was opened, the left DC was identified using the DCM technique and no response was obtained when the DREZ was stimulated. In addition, the left C8 dorsal root was stimulated and identified with monopolar hand probe. A 4 mm lateral myelotomy was performed in segments C7-Th1 at the level of the left DREZ, and a syringo-pleural shunt was placed. SEPs and MEPs were stable throughout the procedure and no EMG discharges were observed. In the postoperative period, the patient’s paresis of the left upper extremity improved, presenting better muscle balance in the extensors of the hand and fingers.

Case 8. A 48-year-old male presented with recurrent post-traumatic holo-cord syringomyelia (

Figure 1. Bottom panel, image a). The patient had a traffic accident in 2012, presenting incomplete acute SC injury with sensory level L3 right/Th11 left, motor level L4 right/L2 left, ASIA D. Initially, the patient underwent posterior fusion at Th11-L3 segments in 2012. However, he developed secondary syringomyelia that required several surgical treatments, with significant clinical deterioration since September 2014. Previous surgeries included a Th6-Th8 DREZ myelotomy for intramedullary stent placement in 2016, a DREZ myelotomy at C2-Th4 for a syringo-pleural shunt in 2017, and a left DREZ myelotomy at C7-Th1 for syringo-peritoneal derivation in 2018 (Case 3 in

Table 1). Over the last years, the patient reported neuropathic back pain, thermo-algesic sensory alteration in the left hemithorax and hemiabdomen, and progressive deterioration of strength and sensitivity in the extremities. Before surgery, the patient experienced progressive clinical worsening, with bilateral upper extremity weakness, more prominent in the distal muscles. The MRI showed progression of the syringomyelic cavity with greater extension at the cranial level, reaching the medullary obex. The patient also presented marked post-laminectomy cervical-thoracic kyphosis, so it was decided to correct the deformity and replace the syringomyelic shunt in the same surgery (Case 8 in

Table 1).

No changes in baseline recordings were observed when the patient was placed in the prone position. At skin opening, monitorable SEPs were recorded from both upper extremities and the right lower limb and were absent from the left lower extremity. MEPs were recorded in all monitored muscles except the left AH. MEPs and SEPs remained stable during instrumentation for the posterior arthrodesis at the C5-Th11 level. Laminectomy was performed at the C5-Th1 level. The previous syringo-peritoneal tube was located and sectioned without observing CSF flow. Dural opening was conducted with wide resection of the fibrotic layer above the previous pleural and peritoneal shunts. After identifying the left C7 and C8 nerve roots, a 5 mm myelotomy was performed in the left DREZ until the septated syrinx was entered. The dentate ligaments were sectioned bilaterally, observing CSF leakage through the dural ridges. After hemostasis, the dura mater was left open. Immediately after placement of the new catheter, an abrupt fall in left MEPs was observed, involving the ADM, APB, rectus femoris, and TA. Unfortunately, these potentials did not recover at the end of the surgery. The patient presented with immediate postoperative global weakness in the left extremities― predominantly affecting the lower extremity―and numbness of the left upper limb. The sensory and motor symptoms of the left upper extremity progressively improved in the following days, with the persistence of weakness in the left lower limb.

Discussion

Syringomyelia is a complex and diverse entity, with particularities in its pathophysiology and surgical approaches. Therefore, a specific IONM protocol is essential to prevent and minimize possible spinal cord damage associated with the surgical intervention. IONM plays a critical role in guiding the surgeon to locate a safe entry zone for myelotomy, minimizing DC damage, and detecting and avoiding sensory and corticospinal pathway injuries by adapting the surgical approach.

The concept of syringomyelia drainage was first described in 1892 by Abbe and Coley, however, it remains a controversial issue in neurosurgery today due to the high complication rates reported (about 50% in some series) and the frequent need for additional reoperations (20%) after shunt placement (24). Furthermore, any intervention over the syringomyelic cavity, such as shunt placement or syringostomy, requires myelotomy and poses a significant risk of additional iatrogenic SC injury. In addition, the SC of these patients is usually already compromised before surgery, and the anatomical references are severely disturbed by the presence of the syrinx, which displaces and distorts neural structures.

Despite the high risk of iatrogenic injury in syringomyelia surgery, there is little evidence to recommend a specific IONM protocol for this type of surgery. To our knowledge, only one article has been published about the benefits of IONM in this specific surgical field (25), and only MEPs and SEPs were included. In line with the findings of Pencovich et al., our data presented a good correlation between the neurophysiological tests conducted preoperatively and baselines established at the time of surgery, as well as good monitorability data for MEPs and SEPs. In the series presented by this group, the only patient who had a transient intraoperative decrease in MEPs had mild postoperative worsening of symptoms, even though the signals recovered to basal levels before the end of surgery. In our study, the two transient MEP events observed, which recovered after a corrective maneuver, did not correlate with any new postoperative deficit, neither clinically nor in postoperative neurophysiological exams. Despite the limitation of the number of cases, it validates the value of IONM with no false-positive or false-negative results.

We present ten cases of syringomyelia surgery with IONM associated with different underlying conditions. Despite the severe SC involvement that all patients presented preoperatively, we observed a high level of monitorability. MEPs from distal muscles to the surgical level were obtained in all cases. Monitorable SEP responses from the upper extremities were present in nine cases and from the lower extremities in seven cases. Most patients had damaged long fibers of the sensory system, as shown by pathological baseline responses with long latencies and low amplitudes. Therefore, it requires additional effort to achieve monitorable baseline recordings; however, distal responses at the surgical level were obtained in 80 % of cases. The three patients in whom no monitorable SEP responses were obtained from the lower limbs (Cases 4, 8, and 9) already presented an absence of cortical potential in the preoperative study (Table 2). These findings constitute an excellent correlation between the preoperative neurophysiological examination and the intraoperative baseline recording at the start of the surgery.

The three transient events observed intraoperatively were relevant (Case 5: global MEP deterioration related to neck flexion in the prone position and EMG neurotonic discharges associated with shunt placement; Case 1: transitory loss of left AHB MEPs during shunt placement through the left DREZ). In all of these, intraoperative signals recovered after a corrective maneuver, such as neck repositioning, catheter removal, or redirection of its trajectory, respectively. At the end of the surgery, no significant changes were observed compared to baseline recordings, and patients did not present any new postoperative deficits. Additionally, the postoperative neurophysiologic test showed CST conduction stability in both patients and even an improvement in the degree of denervation at the segmental level of surgery in Case 5 (Table 2). These observations show the potential reversibility of impending SC damage when an iatrogenic insult is detected in real time, before permanent injury is established. Similarly, the two patients with persistent intraoperative MEP loss presented a postoperative clinical decline that consistently correlated with the decline demonstrated in the postoperative tests (Table 2).

Prepositional baselines are critical to detect potential damage to corticospinal and posterior DC tracts in the prone position. Ensuring a safe neck position is essential when the cervical levels and the medulla are involved. The benefits of IONM in correct patient positioning have been previously reported in cervical and Chiari malformation spinal surgeries (26–29). In our series, Case 5 presented global MEP deterioration in the prone position, which fully recovered when the neck was adjusted to a more neutral position (Figure 3). The consequences of not immediately detecting such extensive damage to the corticospinal pathway would have been devastating.

IONM of the functional integrity of SC pathways is crucial to detect and prevent surgical injury, which monitoring techniques like MEPs and SEPs can achieve. However, some surgical steps require identifying the functional SC tracts, which is the role of the mapping methods (29). It has been proven that the accuracy of IONM increases when multiple modalities are simultaneously monitored (30–32). In our series, DCM with the gracilis SEP phase-reversal technique was used to identify a safe zone entry for the myelotomy, protecting the functional DCs in four cases. In Case 5, both DCs were identified, and negative mapping was obtained at the medium raphe over the entire myelotomy area. In Case 6, the left DC was stimulated and identified, and negative mapping was observed in the DREZ. Only left DC stimulation evoked a response in Case 10, whereas the right DC was silent, indicating dislocation or non-functioning. In Case 9, no responses were obtained despite ruling out technical issues. Negative mapping is also valuable, as it can guide the myelotomy toward the non-functioning area.

Our study supports multimodality IONM as the standard of care in syringomyelia surgery. In our opinion, the IONM protocol should include MEPs for monitoring the corticospinal pathway at the segmental level and long tracts, SEPs for somatosensory pathway monitoring, and free-running EMG for the identification of neurotonic discharges associated with mechanical irritation of CST fibers. D-wave monitoring, if possible, would be advocated as complementary to MEPs for long-term prognosis values in the case of MEP loss. Mapping techniques are highly recommended and should be adapted to the surgical procedure. For example, DCM is essential for identifying the posterior cords and a safe entry zone for the myelotomy. Similarly, CST mapping may be helpful before and during the myelotomy through the DREZ. These mapping techniques would afford the surgeons relevant information to identify functional fibers and, potentially, preserve them. Root mapping could be added for identification and functional assessment of the root. However, its protective role does not seem very relevant. Additionally, monitoring the patient’s positioning using prepositional baseline recordings can be critical when syringes involve the cervical SC and medulla.

Limitations

Our study is a retrospective review with a small number of cases. Also, CST mapping was not performed due to a technical limitation of our monitoring equipment, which did not allow stimulation with the double-train paradigm. Finally, the postoperative neurophysiological tests could not be performed immediately after surgery in all cases, and the period between surgery and testing varied between cases (especially delayed in Cases 6 and 7, where neurophysiological examinations were performed two years after surgery).

Conclusion

Multimodal intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring, including monitoring and mapping techniques, is feasible, reliable in its predictive value, and may help prevent iatrogenic SC damage during syringomyelia surgery. IONM is crucial to guide a safe entry zone for myelotomy, detect impending injuries, and avoid permanent damage by adapting surgical maneuvers.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the personnel of the neurophysiology department, especially nurse C. Sevillano, for her help and technical assistance in conducting EP recordings.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest. This research was partially supported by grant FIS PI22/01082, co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), awarded to MA Poca and by grant 2021SGR/00810 from the Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de 1086 Recerca (AGAUR), Departament de Recerca i Universitats de la Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain.

Author Contributions to the study

Sanchez Roldan had full access to all study data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Author contributions to the study and manuscript preparation include the following: conception and design: Sanchez Roldan, Moncho, Sahuquillo, Poca; data acquisition: Sanchez Roldan, Moncho, Rahnama, Santa-Cruz, Lainez, Baiget; data analysis and interpretation: Sanchez Roldan, Moncho; drafting the article: Sanchez Roldan, Moncho, Sahuquillo, Poca; critically revising the paper: all authors; reviewed submitted version of the manuscript: all authors; approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Sanchez Roldan, Sahuquillo and Poca; study supervision: Sahuquillo and Poca. Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, neither in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data nor in the review or approval of the manuscript.

References

- Vandertop, W.P. Syringomyelia. Neuropediatrics 2014, 45, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, N.; Cacciola, F. Adult syringomielia. Classification, pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 2005, 49, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cacciola, F.; Capozza, M.; Perrini, P.; Benedetto, N.; Di Lorenzo, N. Syringopleural shunt as a rescue procedure in patients with syringomyelia refractory to restoration of cerebrospinal fluid flow. Neurosurgery 2009, 65, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala, F.; Skrap, B.; Kothbauer, K.F.; Deletis, V. Intraoperative neurophysiology in intramedullary spinal cord tumor surgery. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2022, 186, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verla, T.; Fridley, J.S.; Khan, A.B.; Mayer, R.R.; Omeis, I. Neuromonitoring for Intramedullary Spinal Cord Tumor Surgery. World Neurosurg. 2016, 95, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala, F.; Palandri, G.; Basso, E.; Lanteri, P.; Deletis, V.; Faccioli, F.; Bricolo, A. Motor evoked potential monitoring improves outcome after surgery for intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a historical control study. Neurosurgery 2006, 58, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuwer, M.R.; Emerson, R.G.; Galloway, G.; Legatt, A.D.; Lopez, J.; Minahan, R.; Yamada, T.; Goodin, D.S.; Armon, C.; Chaudhry, V.; et al. Evidence-based guideline update: intraoperative spinal monitoring with somatosensory and transcranial electrical motor evoked potentials*. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. Publ. Am. Electroencephalogr. Soc. 2012, 29, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.V.; Chiappa, K.H.; Borges, L.F. Phase reversal of somatosensory evoked potentials triggered by gracilis tract stimulation: case report of a new technique for neurophysiologic dorsal column mapping. Neurosurgery 2012, 70, E783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, D.; Kumaraswamy, V.M.; Braver, D.; Kilbride, R.D.; Borges, L.F.; Simon, M.V. Dorsal column mapping via phase reversal method: the refined technique and clinical applications. Neurosurgery 2014, 74, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.I.; Mohrhaus, C.A.; Husain, A.M.; Karikari, I.O.; Hughes, B.; Hodges, T.; Gottfried, O.; Bagley, C.A. Dorsal column mapping for intramedullary spinal cord tumor resection decreases dorsal column dysfunction. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2012, 25, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deletis, V.; Seidel, K.; Sala, F.; Raabe, A.; Chudy, D.; Beck, J.; Kothbauer, K.F. Intraoperative identification of the corticospinal tract and dorsal column of the spinal cord by electrical stimulation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2018, 89, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scibilia, A.; Terranova, C.; Rizzo, V.; Raffa, G.; Morelli, A.; Esposito, F.; Mallamace, R.; Buda, G.; Conti, A.; Quartarone, A.; et al. Intraoperative neurophysiological mapping and monitoring in spinal tumor surgery: sirens or indispensable tools? Neurosurg. Focus 2016, 41, E18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzilai, O.; Lidar, Z.; Constantini, S.; Salame, K.; Bitan-Talmor, Y.; Korn, A. Continuous mapping of the corticospinal tracts in intramedullary spinal cord tumor surgery using an electrified ultrasonic aspirator. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2017, 27, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmsted, Z.T.; Ryu, B.; Phayal, G.; Green, R.; Lo, S.-F.L.; Sciubba, D.M.; Silverstein, J.W.; D’Amico, R.S. Direct Wave Intraoperative Neuromonitoring for Spinal Tumor Resection: A Focused Review. World Neurosurg. X 2023, 17, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deletis, V.; Sala, F. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring of the spinal cord during spinal cord and spine surgery: a review focus on the corticospinal tracts. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008, 119, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanni, D.S.; Ulkatan, S.; Deletis, V.; Barrenechea, I.J.; Sen, C.; Perin, N.I. Utility of neurophysiological monitoring using dorsal column mapping in intramedullary spinal cord surgery. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2010, 12, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindou, M.; Mertens, P.; Wael, M. Microsurgical DREZotomy for pain due to spinal cord and/or cauda equina injuries: long-term results in a series of 44 patients. Pain 2001, 92, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, D.B.; Dong, C.; Quatrale, R.; Sala, F.; Skinner, S.; Soto, F.; Szelényi, A. Recommendations of the International Society of Intraoperative Neurophysiology for intraoperative somatosensory evoked potentials. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2019, 130, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D.B.; Skinner, S.; Shils, J.; Yingling, C.; American Society of Neurophysiological Monitoring. Intraoperative motor evoked potential monitoring - a position statement by the American Society of Neurophysiological Monitoring. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2013, 124, 2291–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuwer, M.R. New alert criteria for intraoperative somatosensory evoked potential monitoring. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2019, 130, 155–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, D.B. Motor Evoked Potential Warning Criteria. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. Publ. Am. Electroencephalogr. Soc. 2017, 34, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, S.A.; Transfeldt, E.E.; Mehbod, A.A.; Mullan, J.C.; Perra, J.H. Electromyography detects mechanically-induced suprasegmental spinal motor tract injury: review of decompression at spinal cord level. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2009, 120, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahuquillo, J.; Rubio, E.; Poca, M.A.; Rovira, A.; Rodriguez-Baeza, A.; Cervera, C. Posterior fossa reconstruction: a surgical technique for the treatment of Chiari I malformation and Chiari I/syringomyelia complex--preliminary results and magnetic resonance imaging quantitative assessment of hindbrain migration. Neurosurgery 1994, 35, 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batzdorf, U.; Klekamp, J.; Johnson, J.P. A critical appraisal of syrinx cavity shunting procedures. J. Neurosurg. 1998, 89, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencovich, N.; Korn, A.; Constantini, S. Intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring during syringomyelia surgery: lessons from a series of 13 patients. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 2013, 155, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilai, O.; Roth, J.; Korn, A.; Constantini, S. The value of multimodality intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring in treating pediatric Chiari malformation type I. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 2016, 158, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.C.; Emerson, R.G.; Dowling, K.C.; Feldstein, N.A. Attenuation of somatosensory evoked potentials during positioning in a patient undergoing suboccipital craniectomy for Chiari I malformation with syringomyelia. J. Child Neurol. 2001, 16, 936–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, F.; Squintani, G.; Tramontano, V.; Coppola, A.; Gerosa, M. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring during surgery for Chiari malformations. Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2011, 32 Suppl 3, S317–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, B.; Sestokas, A.K.; Schwartz, D.M. Neurophysiological monitoring of spinal cord function during instrumented anterior cervical fusion. Spine J. Off. J. North Am. Spine Soc. 2004, 4, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scibilia, A.; Terranova, C.; Rizzo, V.; Raffa, G.; Morelli, A.; Esposito, F.; Mallamace, R.; Buda, G.; Conti, A.; Quartarone, A.; et al. Intraoperative neurophysiological mapping and monitoring in spinal tumor surgery: sirens or indispensable tools? Neurosurg. Focus 2016, 41, E18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, M.; Tamaki, T.; Yoshida, M.; Kawakami, M.; Kubota, S.; Nakagawa, Y.; Iwasaki, H.; Tsutsui, S.; Yamada, H. Intraoperative spinal cord monitoring using combined motor and sensory evoked potentials recorded from the spinal cord during surgery for intramedullary spinal cord tumor. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2015, 133, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutter, M.; Eggspuehler, A.; Grob, D.; Jeszenszky, D.; Benini, A.; Porchet, F.; Mueller, A.; Dvorak, J. The diagnostic value of multimodal intraoperative monitoring (MIOM) during spine surgery: a prospective study of 1,017 patients. Eur. Spine J. Off. Publ. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform. Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 2007, 16 Suppl 2, S162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).