Submitted:

29 January 2024

Posted:

30 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

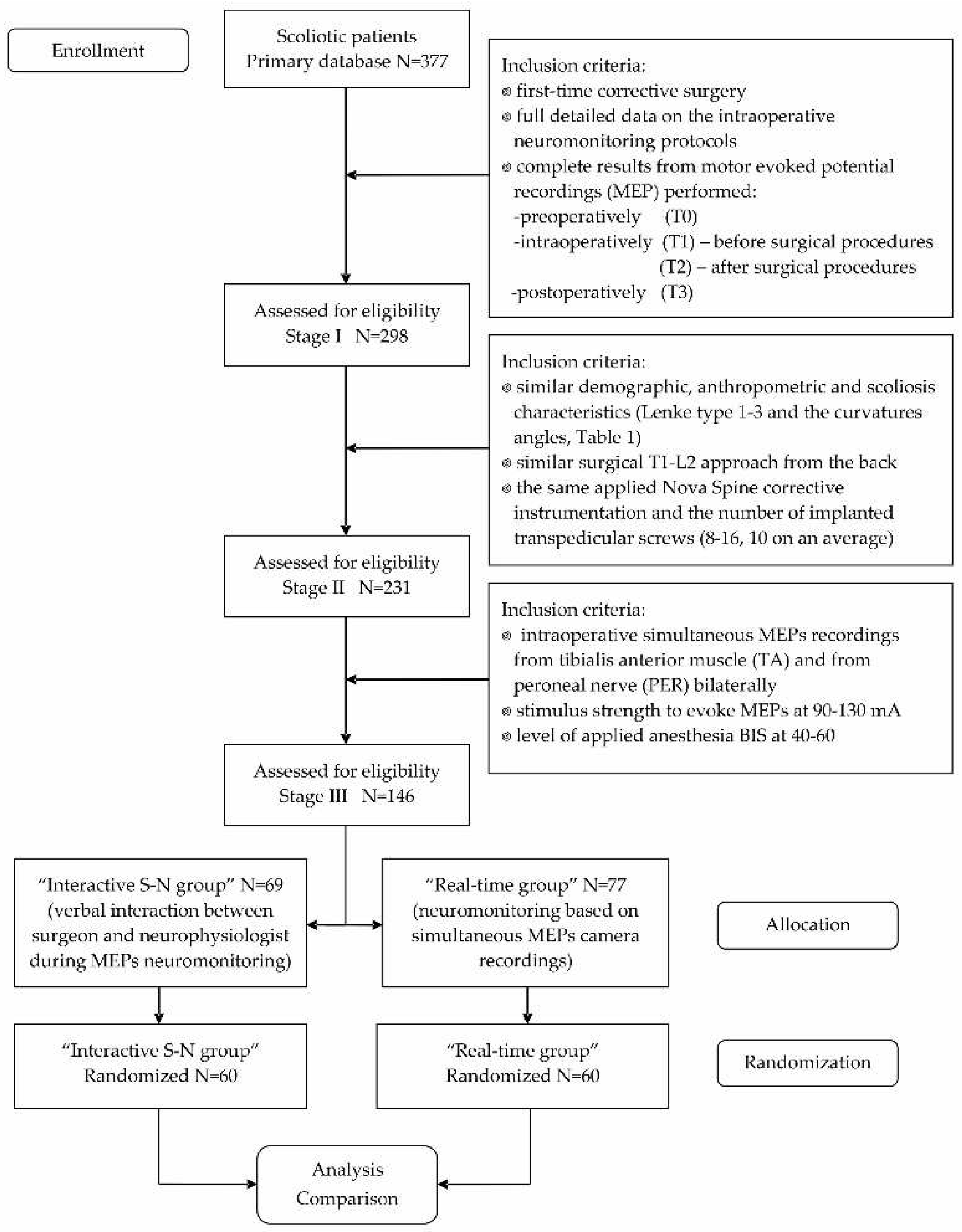

2.1. Participants and Study Design

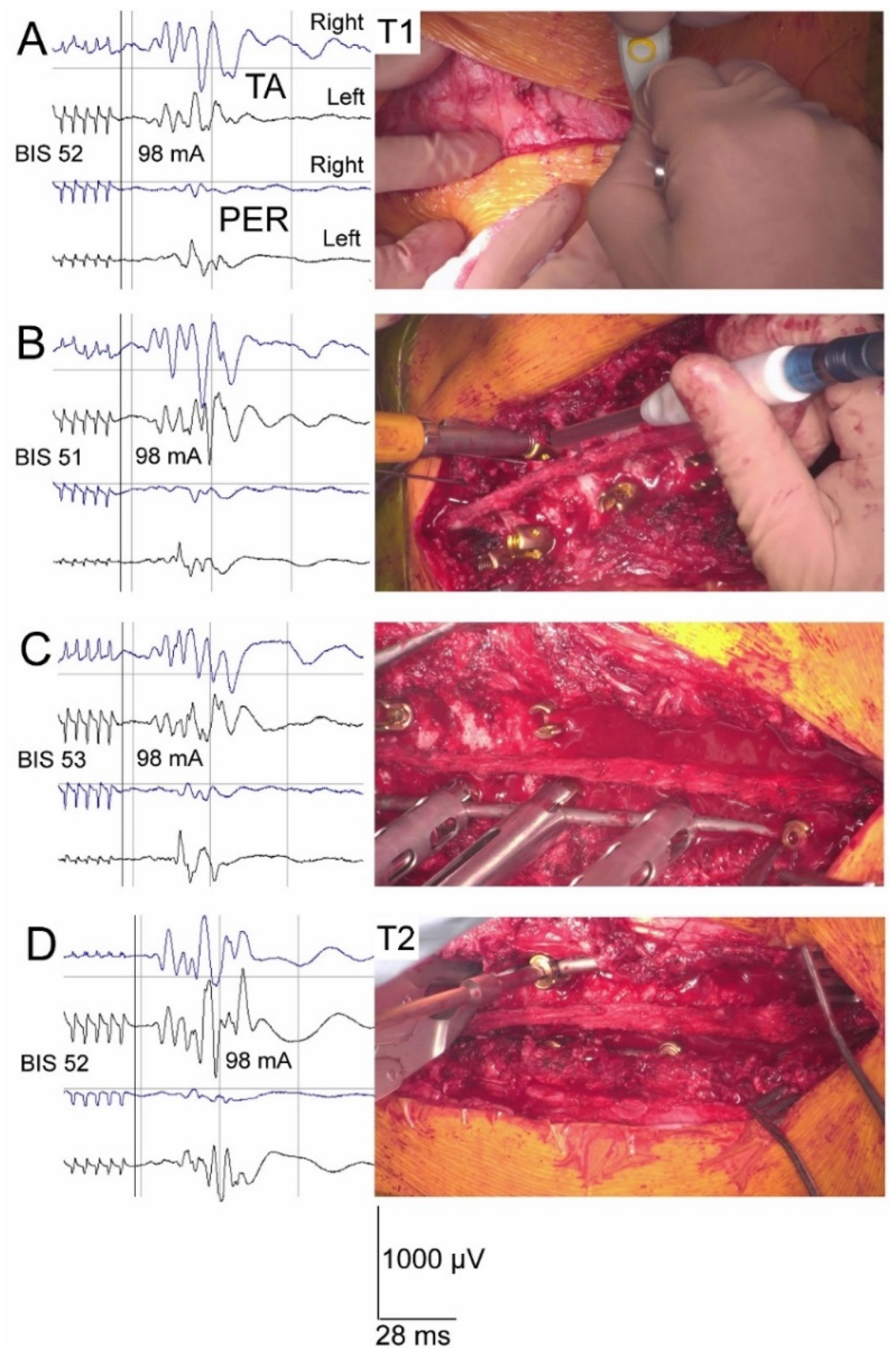

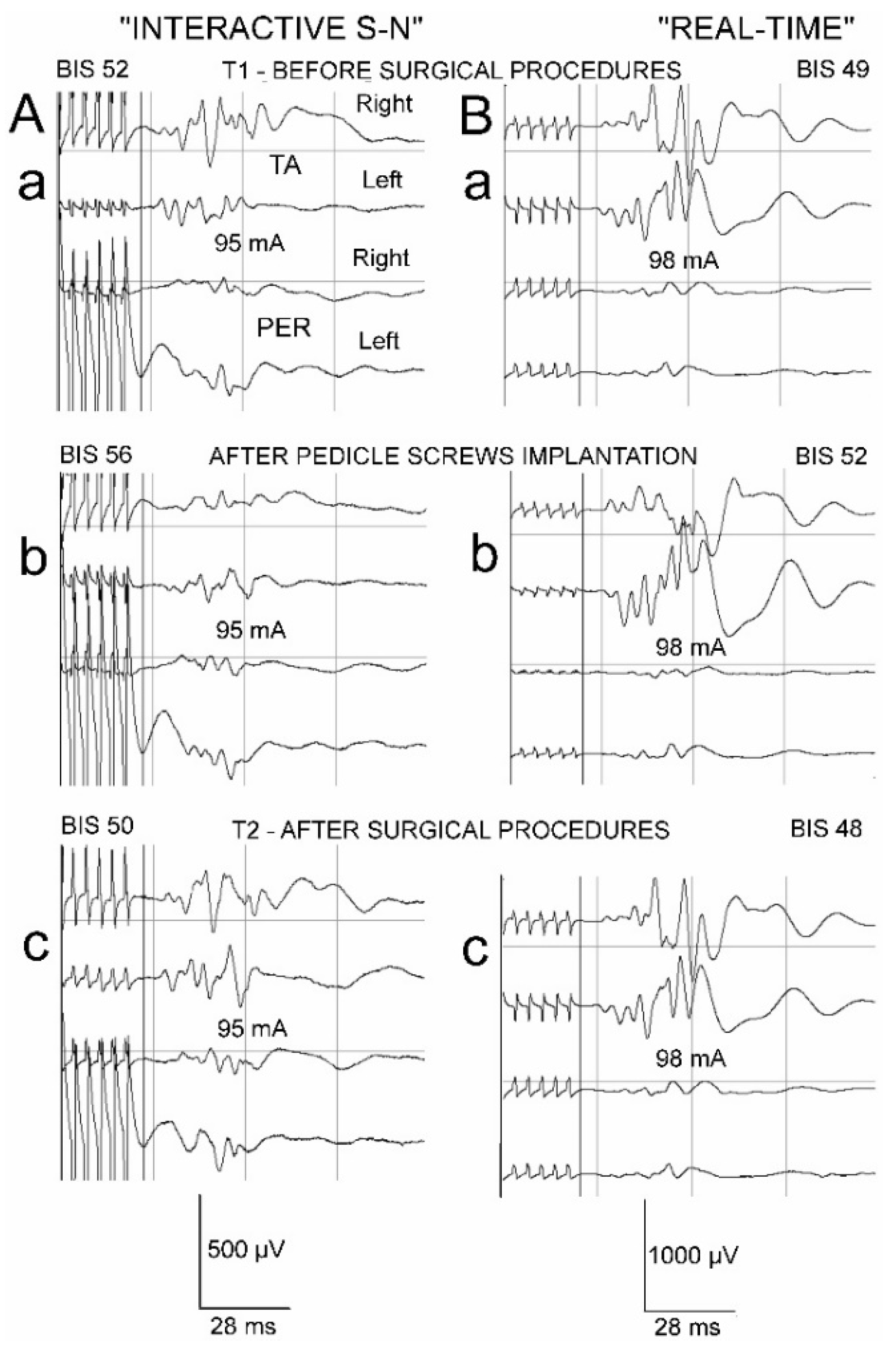

2.2. Anaesthesia, Spine Surgery, Neurophysiological Recordings and Neuromonitoring Principles

2.3. Statistical Analysis

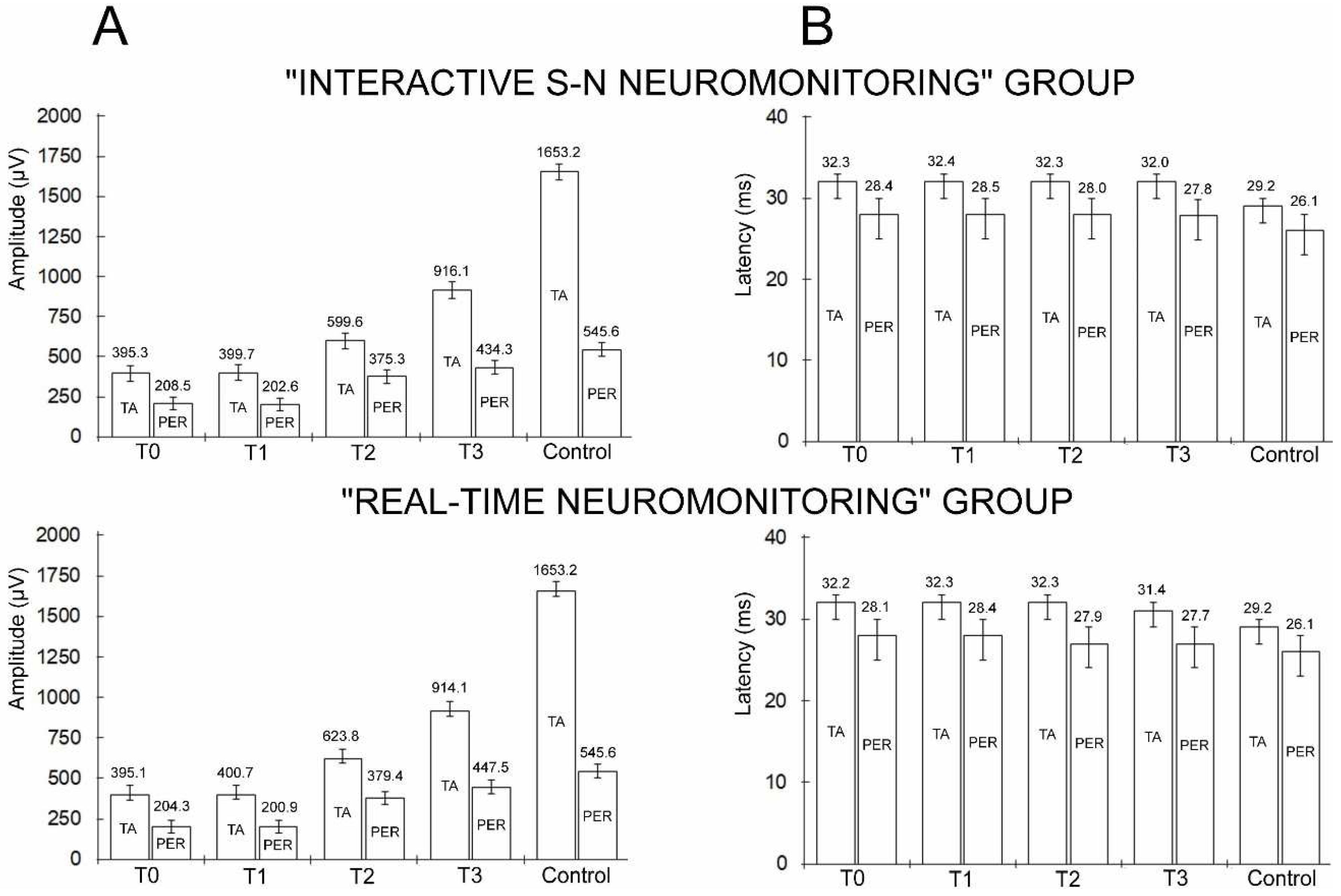

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dayer, R.; Haumont, T.; Belaieff, W.; Lascombes, P. Idiopathic scoliosis: etiological concepts and hypotheses. J. Childr. Orthop. 2013, 7, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konieczny, M.R.; Senyurt, H.; Krauspe, R. Epidemiology of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Child. Orthop. 2013, 7, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hresko, M.T. Idiopathic Scoliosis in Adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrini, S.; Antonini, G.; Carabalona, R.; Minozzi, S. Physical exercises as a treatment for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. A systematic review. Pediatr. Rehabil. 2003, 6, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrini, S.; Minozzi, S.; Bettany-Saltikov, J.; Zaina, F.; Chockalingam, N.; Grivas, T.B.; Kotwicki, T.; Maruyama, T.; Romano, M.; Vasiliadis, E.S. Braces for idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents. Spine 2010, 35, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, S.L.; Dolan, L.A.; Wright, J.G.; Dobbs, M.B. Effects of bracing in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. N Engl J Med. 2013, 369, 1512–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepke, W.; Morani, W.; Schiltenwolf, M.; Bruckner, T.; Renkawitz, T.; Hemmer, S.; Akbar, M. Outcome of Conservative Therapy of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis (AIS) with Chêneau-Brace. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daroszewski, P.; Huber, J.; Kaczmarek, K.; Janusz, P.; Główka, P.; Tomaszewski, M.; Domagalska, M.; Kotwicki, T. Comparison of Motor Evoked Potentials Neuromonitoring Following Pre- and Postoperative Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation and Intraoperative Electrical Stimulation in Patients Undergoing Surgical Correction of Idiopathic Scoliosis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, S.; Eun, L.Y.; Kim, N.K.; Jung, J.W.; Choi, J.Y.; Kim, H.S. Cardiopulmonary function and scoliosis severity in idiopathic scoliosis children. Kor. J. Ped. 2015, 58, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.; Shah, N.; Freetly, T.; Dekis, J.; Hariri, O.; Walker, S.; Borrelli, J.; Post, N.H.; Diebo, B.G.; Urban, W.P.; Paulino, C.B. Treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and evaluation of the adolescent patient. Curr. Orthop. Pract. 2018, 29, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Hwang, C.J.; Lee, D.H.; Cho, J.H.; Park, S. Risk Factors and Exit Strategy of Intraoperative Neurophysiological Monitoring Alert During Deformity Correction for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Global Spine J. Published online March 14. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, M.G.; Moore, D.W.; Matsumoto, H.; Emerson, R.G.; Booker, W.A.; Gomez, J.A.; Gallo, E.J.; Hyman, J.E.; Roye, D.P. Jr Risk factors for spinal cord injury during surgery for spinal deformity. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2010, 92, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridwell, K.H.; Lenke, L.G.; Baldus, C.; Blanke, K. Major intraoperative neurologic deficits in pediatric and adult spinal deformity patients. Incidence and etiology at one institution. Spine 1998, 23, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.M.; Auerbach, J.D.; Dormans, J.P.; Flynn, J.; Drummond, D.S.; Bowe, J.A.; Laufer, S.; Shah, S.A.; Bowen, J.R.; Pizzutillo, P.D.; Jones, K.J.; Drummond, D.S. Neurophysiological detection of impending spinal cord injury during scoliosis surgery. J. Bone J. Surg. 2007, 89, 2440–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorelli, F.; Di Silvestre, M.; Plasmati, R.; Michelucci, R.; Greggi, T.; Morigi, A.; Bacchin, M.R.; Bonarelli, S.; Cioni, A.; Vommaro, F.; et al. The prevention of neural complications in the surgical treatment of scoliosis: The role of the neurophysiological intraoperative monitoring. Eur. Spine J. 2011, 20, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.H.; Park, Y.G.; Kim, D.H.; Yoon, S.Y. Monitoring of Motor and Somatosensory Evoked Potentials During Spine Surgery: Intraoperative Changes and Postoperative Outcomes. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 40, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehlings, M.G.; Brodke, D.S.; Norvell, D.C.; Dettori, J.R. The evidence for intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring in spine surgery: does it make a difference? Spine 2010, 35 (9 Suppl),, S37–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.A.; Jeyanandarajan, D.; Hansen, C.; Zada, G.; Hsieh, P.C. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring during spine surgery: a review. Neurosurgical Focus 2009, 27, E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, R.R.; Hauptman, J.S.; Munoz, C.; et al. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring in spine surgery: indications, efficacy, and role of the preoperative checklist. Neurosurgical Focus 2012, 33, E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, M.G.; Skaggs, D.L.; Pace, G.I.; Wright, M.L.; Matsumoto, H.; Anderson, R.C.; Brockmeyer, D.L.; Dormans, J.P.; Emans, J.B.; Erickson, M.A.; Flynn, J.M.; Glotzbecker, M.P.; Ibrahim, K.N.; Lewis, S.J.; Luhmann, S.J.; Mendiratta, A.; et al. Best Practices in Intraoperative Neuromonitoring in Spine Deformity Surgery: Development of an Intraoperative Checklist to Optimize Response. Spine Deformity 2014, 2, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziewacz, J.E.; Berven, S.H.; Mummaneni, V.P.; Tu, T.H.; Akinbo, O.C.; Lyon, R.; Mummaneni, P.V. The design, development, and implementation of a checklist for intraoperative neuromonitoring changes. Neurosurgical Focus 2012, a33, E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daroszewski, P.; Garasz, A.; Huber, J.; Kaczmarek, K.; Janusz, P.; Główka, P.; Tomaszewski, M.; Kotwicki, T. Update on neuromonitoring procedures applied during surgery of the spine—Observational study. Reumatologia 2023, 61, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadella, M.C.; Dulfer, S.E.; Absalom, A.R.; Lange, F.; Scholtens-Henzen, C.H.; Groen, R.J.; Wapstra, F.H.; Faber, C.; Tamási, K.; Sahinovic, M.M.; et al. Comparing Motor-Evoked Potential Characteristics of Needle versus Surface Recording Electrodes during Spinal Cord Monitoring-The NERFACE Study Part I. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulfer, S.E.; Gadella, M.C.; Tamási, K.; Absalom, A.R.; Lange, F.; Scholtens-Henzen, C.H.; Faber, C.; Wapstra, F.H.; Groen, R.J.; Sahinovic, M.M.; et al. Use of Needle Versus Surface Recording Electrodes for Detection of Intraoperative Motor Warnings: A Non-Inferiority Trial. The NERFACE Study Part II. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuwer, M.R.; Dawson, E.G.; Carlson, L.G.; et al. Somatosensory evoked potential spinal cord monitoring reduces neurologic deficits after scoliosis surgery: results of a large multicenter survey. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1995, 96, 6.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, D.N.; Strantzas, S.; Steinberg, B.E. Intraoperative neuromonitoring in paediatric spinal surgery. BJA Education 2019, 19, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, S.; Palukuri, N.; Gupta, P.; Kohli, M. Transcranial Motor Evoked Potentials during Spinal Deformity Corrections-Safety, Efficacy, Limitations, and the Role of a Checklist. Front Surg. 2017, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, R. B. Neurologic safety in spinal deformity surgery. Spine 1997, 22, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Pan, W.; Chen, J.; Peng, X.; Ling, Z.; Zou, X. Application of electrophysiological measures in degenerative cervical myelopathy. Front. Cell. Devel. Biol. 2022, 10, 834668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, V.; Curt, A. Neurological aspects of spinal-cord repair: promises and challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczyńska, K.; Huber, J. Comparing Parameters of Motor Potentials Recordings Evoked Transcranially with Neuroimaging Results in Patients with Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury: Assessment and Diagnostic Capabilities. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.L.; Chan, L.L.; Lim, W.; Tan, S.B.; Tan, C.T.; Chen, J.L.; Fook-Chong, S.; Ratnagopal, P. Transcranial magnetic stimulation screening for cord compression in cervical spondylosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2006, 244, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscevic, M.; Sehic, A.; Krupic, F. Intraoperative neuromonitoring in spine deformity surgery: modalities, advantages, limitations, medicolegal issues - surgeons' views. EFORT Open Rev. 2020, 5, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, D.B. Intraoperative motor evoked potential monitoring: Overview and update. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2006, 20, 347–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deletis, V. Basic methodological principles of multimodal intraoperative monitoring during spine surgeries. Eur. Spine J. 2007, 16 (Suppl. S2), 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampidis, A.; Jiang, F.; Wilson, J.R.F.; Badhiwala, J.H.; Brodke, D.S.; Fehlings, M.G. Use of Intraoperative Neurophysiological Monitoring in Spine Surgery. Global Spine J. 2020, 10, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garasz, A.; Huber, J.; Grajek, M.; Daroszewski, P. Motor evoked potentials recorded from muscles versus nerves after lumbar stimulation in healthy subjects and patients with disc-root conflicts. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 2023, 46, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, J.W.; Sebel, P.S. Development and clinical application of electroencephalographic bispectrum monitoring. Anesthesiology 2000, 93, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medical Advisory Secretariat. Bispectral index monitor: An evidence-based analysis. Ont. Health Technol. Assess. Ser. 2004, 4, 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Viertiö-Oja, H.; Maja, V.; Särkelä, M.; Talja, P.; Tenkanen, N.; Tolvanen-Laakso, H.; Paloheimo, M.; Vakkuri, A.; Yli-Hankala, A.; Meriläinen, P. Description of the Entropy algorithm as applied in the Datex-Ohmeda S/5 Entropy Module. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2004, 48, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenke, L.G.; Betz, R.R.; Harms, J.; Bridwell, K.H.; Clements, D.H.; Lowe, T.G.; Blanke, K. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2001, 83, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovadia, D. Classification of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS). J. Child Orthop. 2013, 7, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soghomonyan, S.; Moran, K.R.; Sandhu, G.S.; Bergese, S.D. Anesthesia and evoked responses in neurosurgery. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 14, 5–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wincek, A.; Huber, J.; Leszczyńska, K.; Fortuna, W.; Okurowski, S.; Chmielak, K.; Tabakow, P. The Long-Term Effect of Treatment Using the Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation rTMS in Patients after Incomplete Cervical or Thoracic Spinal Cord Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legatt, A.D.; Emerson, R.G.; Epstein, C.M.; MacDonald, D.B.; Deletis, V.; Bravo, R.J.; López, J.R. ACNS Guideline: Transcranial Electrical Stimulation Motor Evoked Potential Monitoring. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2016, 33, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.A.; Jeyanandarajan, D.; Hansen, C.; Zada, G.; Hsieh, P.C. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring during spine surgery: a review. Neurosurg. Focus 2009, 27, E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, J.M.; Singla, A.; Shen, F.H.; Arlet, V. Complications of pedicle screw fixation in scoliosis surgery: A systematic review. Spine 2010, 35, E465–E470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, M.K.; Loh, K.W.; Chung, W.H.; Hasan, M.S.; Chan, C.Y.W. Perioperative outcome and complications following single-staged posterior spinal fusion using pedicle screw instrumentation in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis(AIS): A review of 1057 cases from a single centre. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, R.; Lieberman, J.A.; Grabovac, M.T.; Hu, S. Strategies for managing decreased motor evoked potential signals while distracting the spine during correction of scoliosis. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 2004, 16, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, G.; Imagama, S.; Kawabata, S.; Yamada, K.; Kanchiku, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Tadokoro, N.; Takahashi, M.; Wada, K.; Yamamoto, N.; et al. Adverse Events Related to Transcranial Electric Stimulation for Motor-evoked Potential Monitoring in High-risk Spinal Surgery. Spine 2019, 44, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, K.; Imagama, S.; Ito, Z.; Ando, K.; Hida, T.; Ito, K.; Tsushima, M.; Ishikawa, Y.; Matsumoto, A.; Nishida, Y.; et al. Transcranial motor evoked potential waveform changes in corrective fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2017, 19, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luc, F.; Mainard, N.; Payen, M.; Bernardini, I.; El-Ayoubi, M.; Friberg, A.; Piccoli, N.D.; Simon, A.L. Study of the latency of transcranial motor evoked potentials in spinal cord monitoring during surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2022, 52, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizkallah, M.; El Abiad, R.; Badr, E.; Ghanem, I. Positional disappearance of motor evoked potentials is much more likely to occur in non-idiopathic scoliosis. J. Child. Orthop. 2019, 13, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckwalter, J.A.; Yaszay, B.; Ilgenfritz, R.M.; Bastrom, T.P.; Newton, P.O. Harms Study Group Analysis of Intraoperative Neuromonitoring Events During Spinal Corrective Surgery for Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine Deformity 2013, 1, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasby, M.A.; Tsirikos, A.I.; Henderson, L.; Horsburgh, G.; Jordan, B.; Michaelson, C.; Adams, C.I.; Garrido, E. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in the semi-quantitative, pre-operative assessment of patients undergoing spinal deformity surgery. Eur. Spine J. 2017, 26, 2103–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virk, S.; Klamar, J.; Beebe, A.; Ghosh, D.; Samora, W. The Utility of Preoperative Neuromonitoring for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Int. J. Spine Surg. 2019, 13, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.L.; Tan, Y.E.; Raman, S.; Teo, A.; Dan, Y.F.; Guo, C.M. Systematic re-evaluation of intraoperative motor-evoked potential suppression in scoliosis surgery. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2018, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcey, T.M.; Kobylarz, E.J.; Pearl, M.A.; Krauss, P.J.; Ferri, S.A.; Roberts, D.W.; Bauer, D.F. Safe use of subdermal needles for intraoperative monitoring with MRI. Neurosurg. Focus 2016, 40, E19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, A.; Andras, L.; Lehman, A.; Bridges, N.; Skaggs, D.L. Dermal Discolorations and Burns at Neuromonitoring Electrodes in Pediatric Spine Surgery. Spine 2017, 42, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Group of subjects |

Age (years) | Height (cm) |

Weight (kg) | BMI | Scoliosis Type [41] |

Cobb’s angle [42] (Preoperatively) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Interactive S-N” neuromonitoring group N = 60 ♀ |

8 – 17 14.2 ± 1.6 |

135 – 181 164.4 ± 2.0 |

30 – 84 54.5 ± 2.9 |

17.6 – 29.9 23.1 ± 4.0 |

Lenke 1 = 10 Lenke 2 = 48 Lenke 3 = 2 |

Primary 41 – 86 57.4 ± 6.6 Secondary 24 – 50 37.1 ± 3.3 |

| “Real-time” neuromonitoring group N = 60 ♀ |

9 – 18 14.7 ± 1.5 |

137 – 179 165.6 ± 2.5 |

29 – 83 53.1 ± 3.1 |

17.4 – 30.1 22.9 ± 3.9 |

Lenke 1 = 11 Lenke 2 = 46 Lenke 3 = 3 |

Primary 40 – 89 56.3 ± 7.1 Secondary 25 – 50 37.3 ± 3.9 |

| Healthy volunteers “Control” group N = 60 ♀ |

8 – 18 14.3 ± 1.5 |

134 – 183 166.1 ± 2.6 |

30 – 84 54.9 ± 5.3 |

17.4 – 29.8 22.8 ± 3.7 |

NA | NA |

|

p – value (difference) “Interactive S-N” vs. “Real-time” “Interactive S-N” vs. “Control” “Real-time” vs. “Control” |

0.223 NS 0.177 NS 0.082 NS |

0.182 NS 0.192 NS 0.091 NS |

0.171 NS 0.122 NS 0.079 NS |

0.183 NS 0.089 NS 0.119 NS |

0.062 NS | Primary angle 0.199 NS Secondary angle 0.328 NS |

| Test Parameter |

Side | TMS Control N=60 |

Scoliosis side |

TMS Patients Preoperative T0 |

Control vs. Patients T0 |

TES Patients Intraoperative T1 (Before IS correction) |

TMS Patients T0 vs. TES Patients T1 |

TES Patients Intraoperative T2 (After IS correction) |

TES Patients T1 vs. T2 |

TMS Patients Postoperative T3 |

TMS Patients T0 vs. T3 |

Control vs. Patients T3 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min. – Max. Mean ± SD |

Min. – Max. Mean ± SD |

p - value | Min. – Max. Mean ± SD |

p - value | Min. – Max. Mean ± SD |

p - value | Min. – Max. Mean ± SD |

p - value | p - value | ||||

| MEP recorded from anterior tibial muscle - TA | |||||||||||||

| “INTERACTIVE S-N” NEUROMONITORING GROUP N=60 | Amplitude (µV) |

R | 1300 – 3600 1695.1 ± 92.8 |

Convex | 250 – 1400 412.1 ± 70.4 |

0.009 | 200 –1300 430.4 ±78.1 |

0.091 | 400 – 1850 688.2 ± 76.4 ↑ |

0.029 | 700 – 2400 977.1 ± 99.1 ↑ |

0.023 | 0.008 |

| L | 1000 – 3050 1611.9 ± 72.8 |

Concave | 200 – 1300 385.4 ± 49.8 |

0.009 | 150 –1050 369.9 ± 73.6 |

0.094 | 300 – 1650 511.1 ± 78.3 ↑ |

0.042 | 550 – 1900 855.3 ± 100.2 ↑ |

0.019 | 0.008 | ||

| p - value | R vs. L |

0.119 | Convex vs. Concave |

0.048 | NA | 0.047 | NA | 0.045 | NA | 0.048 | NA | NA | |

| Latency (ms) | R | 24.3 – 31.6 28.8 ± 1.4 |

Convex | 27.2 – 36.1 31.9 ± 3.1 |

0.036 | 28.9 – 38.1 31.7 ± 1.5 |

0.121 | 28.0 – 38.3 31.4 ± 1.4 |

0.299 | 28.5 – 39.1 30. 9 ± 2.0 |

0.058 | 0.031 | |

| L | 25.1 – 32.0 29.6 ± 1.5 |

Concave | 28.8 – 39.1 32.7 ± 2.6 |

0.037 | 29.4 – 39.6 32.9 ± 2.0 |

0.111 | 30.3 – 40.2 33.2 ± 2.6 |

0.298 | 30.5 – 40.0 33.2 ± 2.1 |

0.060 | 0.041 | ||

| p - value | R vs. L |

0.205 | Convex vs. Concave |

0.077 | NA | 0.052 | NA | 0.067 | NA | 0.058 | NA | NA | |

| MEP recorded from peroneal nerve - PER | |||||||||||||

| Amplitude (µV) |

R | 450 – 2050 565.7 ± 55.4 |

Convex | 100 – 800 213.2 ± 46.1 |

0.028 | 100 – 700 218.1 ±44.3 |

0.114 | 200 – 800 ↑ 388.3 ± 39.8 ↑ |

0.043 | 200 – 800 ↑ 443.6 ± 33.8 ↑ |

0.034 | 0.044 | |

| L | 400 – 2000 525.7 ± 58.2 |

Concave | 50 – 700 186.2 ± 36.3 |

0.029 | 50 – 600 187.2 ± 40.1 |

0.009 | 300 – 750 362.3 ± 38.1 |

0.041 | 350 – 800 425.1 ± 41.4 |

0.031 | 0.045 | ||

| p - value | R vs. L |

0.112 | Convex vs. Concave |

0.102 | NA | 0.052 | NA | 0.073 | NA | 0.072 | NA | NA | |

| Latency (ms) | R | 22.1 – 28.9 25.9 ± 1.6 |

Convex | 23.0 – 31.4 27.6 ± 3.4 |

0.042 | 22.9 – 31.1 27.8 ± 3.5 |

0.075 | 22.7 – 31.0 27.8 ± 3.3 |

0.321 | 22.5 – 31.3 27.6 ± 3.2 |

0.091 | 0.041 | |

| L | 22.9 – 30.0 26.3 ± 1.6 |

Concave | 23.6 – 33.5 29.2 ± 3.6 |

0.039 | 23.7 – 34.0 29.1 ± 3.3 |

0.111 | 23.4 – 32.1 28.4 ± 3.6 |

0.114 | 22.9 – 32.0 28.0 ± 3.1 |

0.061 | 0.046 | ||

| p - value | R vs. L |

0.095 | Convex vs. Concave |

0.048 | NA | 0.049 | NA | 0.051 | NA | 0.073 | NA | NA | |

| TA vs. PER cumulative (R+L) MEP amplitude difference (µV) |

1108.2 ↓ | 189.8 ↓ | 197.5 ↓ | 224.3 ↓ | 481.8 ↓ | ||||||||

| % of difference | 67.1 ↓ | 47.8 ↓ | 49.3 ↓ | 37.4 ↓ | 52.5 ↓ | ||||||||

| p - value | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.022 | 0.008 | ||||||||

| TA vs. PER cumulative (R+L) MEP latency difference (µV) |

3.1 ↓ | 3.9 ↓ | 3.9 ↓ | 4.3 ↓ | 4.2 ↓ | ||||||||

| % of difference | 10.6 ↓ | 12.0 ↓ | 12.0 ↓ | 13.3 ↓ | 13.1 ↓ | ||||||||

| p - value | 0.043 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.031 | 0.030 | ||||||||

| MEP recorded from anterior tibial muscle - TA | |||||||||||||

| “REAL-TIME” NEUROMONITORING GROUP N=60 | Amplitude (µV) |

R | 1300 – 3600 1695.1 ± 92.8 |

Convex | 300 – 1350 410.9 ± 62.1 |

0.008 | 250 –1400 425.7 ±71.2 |

0.084 | 450 – 1900 696.9 ± 69.3 ↑ |

0.027 | 750 – 2300 975.4 ± 65.3 ↑ |

0.021 | 0.018 |

| L | 1000 – 3050 1611.9 ± 72.8 |

Concave | 150 – 1250 380.1 ± 45.4 |

0.009 | 200 –1200 375.8 ± 73.6 |

0.085 | 350 – 1950 550.7 ± 59.8 ↑ |

0.038 | 600 – 1850 852.9 ± 88.1 ↑ |

0.018 | 0.019 | ||

| p - value | R vs. L |

0.119 | Convex vs. Concave |

0.047 | NA | 0.046 | NA | 0.040 | NA | 0.047 | NA | NA | |

| Latency (ms) | R | 24.3 – 31.6 28.8 ± 1.4 |

Convex | 27.7 – 37.3 31.6 ± 3.5 |

0.032 | 28.8– 38.6 31.8 ± 2.8 |

0.185 | 28.1 – 38.6 31.3 ± 2.5 |

0.119 | 28.2 – 39.0 31. 1 ± 2.5 |

0.059 | 0.034 | |

| L | 25.1 – 32.0 29.6 ± 1.5 |

Concave | 28.7 – 38.9 32.8 ± 3.1 |

0.034 | 29.6 – 39.2 32.8 ± 3.2 |

0.206 | 30.4 – 41.9 33.4 ± 2.9 |

0.194 | 30.1 – 39.8 31.8 ± 2.8 |

0.061 | 0.038 | ||

| p - value | R vs. L |

0.205 | Convex vs. Concave |

0.081 | NA | 0.055 | NA | 0.061 | NA | 0.251 | NA | NA | |

| MEP recorded from peroneal nerve - PER | |||||||||||||

| Amplitude (µV) |

R | 450 – 2050 565.7 ± 55.4 |

Convex | 150 – 900 218.4 ± 45.8 |

0.031 | 150 – 750 215.9 ±48.2 |

0.123 | 300 – 900 390.8 ± 35.2 ↑ |

0.040 | 250 – 900 448.9 ± 36.1 ↑ |

0.029 | 0.046 | |

| L | 400 – 2000 525.7 ± 58.2 |

Concave | 100 – 800 189.8 ± 48.1 |

0.030 | 100 – 650 185.9 ± 38.3 |

0.008 | 300 – 800 368.1 ± 38.9 ↑ |

0.043 | 300 – 805 446.1 ± 38.1 ↑ |

0.027 | 0.048 | ||

| p - value | R vs. L |

0.212 | Convex vs. Concave |

0.108 | NA | 0.055 | NA | 0.065 | NA | 0.080 | NA | NA | |

| Latency (ms) | R | 22.1 – 28.9 25.9 ± 1.6 |

Convex | 23.4 – 31.8 27.2 ± 2.8 |

0.043 | 23.2 – 31.4 27.8 ± 3.5 |

0.074 | 22.6 – 31.4 27.8 ± 3.3 |

0.325 | 22.8 – 31.1 27.5 ± 2.8 |

0.082 | 0.040 | |

| L | 22.9 – 30.0 26.3 ± 1.6 |

Concave | 23.8 – 33.3 29.1 ± 3.1 |

0.041 | 23.5 – 33.9 29.0 ± 3.1 |

0.129 | 23.5 – 32.0 28.1 ± 3.1 |

0.121 | 22.7 – 32.1 28.0 ± 3.2 |

0.073 | 0.044 | ||

| p - value | R vs. L |

0.224 | Convex vs. Concave |

0.047 | NA | 0.047 | NA | 0.055 | NA | 0.081 | NA | NA | |

| TA vs. PER cumulative (R+L) MEP amplitude difference (µV) |

1108.2 ↓ | 191.2 ↓ | 199.8 ↓ | 244.4 ↓ | 466.6 ↓ | ||||||||

| % of difference | 67.1 ↓ | 48.3 ↓ | 49.8 ↓ | 39.1 ↓ | 51.0 ↓ | ||||||||

| p - value | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.023 | 0.008 | ||||||||

| TA vs. PER cumulative (R+L) MEP latency difference (µV) |

3.1 ↓ | 4.1 ↓ | 3.9 ↓ | 4.4 ↓ | 3.7 ↓ | ||||||||

| % of difference | 10.6 ↓ | 12.7 ↓ | 12.0 ↓ | 13.6 ↓ | 11.7 ↓ | ||||||||

| p - value | 0.043 | 0.033 | 0.032 | 0.028 | 0.048 | ||||||||

| Variable Neurophysiological event Surgical event |

“Interactive S-N neuromonitoring” group N=60 |

“Real-time neuromonitoring” group N=60 |

Difference p |

|---|---|---|---|

| BIS level | 40-65 (52.4±4.1) | 40-60 (51.3±3.9) | 0.236 |

| TES strength (mA) during maximal amplitude MEP recordings |

80-124 (99.2±8.1) | 80-130 (97.3±7.3) | 0.194 |

| Number of neurophysiologist’s warnings associated with MEP parameters fluctuations: -During surgery field preparation (including effects of transient “warming” during cauterization and shocks caused by releasing the vertebral joints) -During pedicle screws implantation -During corrective rods implantation -During distraction, derotation, compression |

9/60 12/60 10/60 8/60 |

7/60 8/60 6/60 4/60 |

0.07 0.04 0.04 0.03 |

| Anaesthesia related events: -TA recorded bilaterally MEP -PER recorded bilaterally MEP |

5/60 1/60 |

4/60 2/60 |

0.135 0.163 |

| False alarms caused by technical malfunctions | 1/60 | 2/60 | 0.165 |

| False alarms caused by movement-related artifacts following TES |

1/60 | 0/60 | 0.239 |

| Averaged time of surgery | 5.5 | 4.5 | 0.04 |

| Number of bidirectional communications: -S vs. N -N vs. S |

587 396 |

292 191 |

0.008 0.008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).