Submitted:

29 June 2023

Posted:

30 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Only a minority of buildings provide an entire HVAC system: the majority can include only air-conditioning installations, or only heating system, or heating and air-conditioning distributions, or combined applications to provide ventilation, heating and cooling.

- Only a minority of buildings include IoT: it is becoming common to incorporate sensors that are used by Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems to control HVAC systems but integrate them into IoT ecosystem, as it is contributed with this paper, remains a challenge.

- The building stock is obsolete, so an intervention on energy efficiency must also ensure air quality conditions as key requirement by maintaining a healthy context and indoor comfortability with minimal energy and impact on the environment.

- Built environment is huge so transversal strategies need to be low cost and economically sustainable.

2. Building and IoT: reality and challenges

- For users, IoT enhances HVAC systems with low cost, time and impact.

- For architects, IoT improves knowledge for an architecture evidence-based design about real behavior of buildings and users (overcoming the gap between theoretical values and real data).

- For engineers, IoT eases to study the most suitable energy system for each building according to its ubication, orientation, design, typology of spaces, uses, etc.

- For urbanists, extrapolated to urban scale and combining con Geographical Information System (GIS), IoT provides general strategies by zones.

- For geographers, overcoming the urban scale, IoT learns social behaviors, patterns and trends, etc.

- For epidemiologists and doctors, IoT makes it possible to correlate the spread of certain diseases with IAQ and environmental parameters and trends.

- For local, national and international institutions, IoT shares data on behavior patterns to implement strategies of rehabilitation, energy, management, etc. for energy, electricity, CO2, etc.

3. Materials and Methods

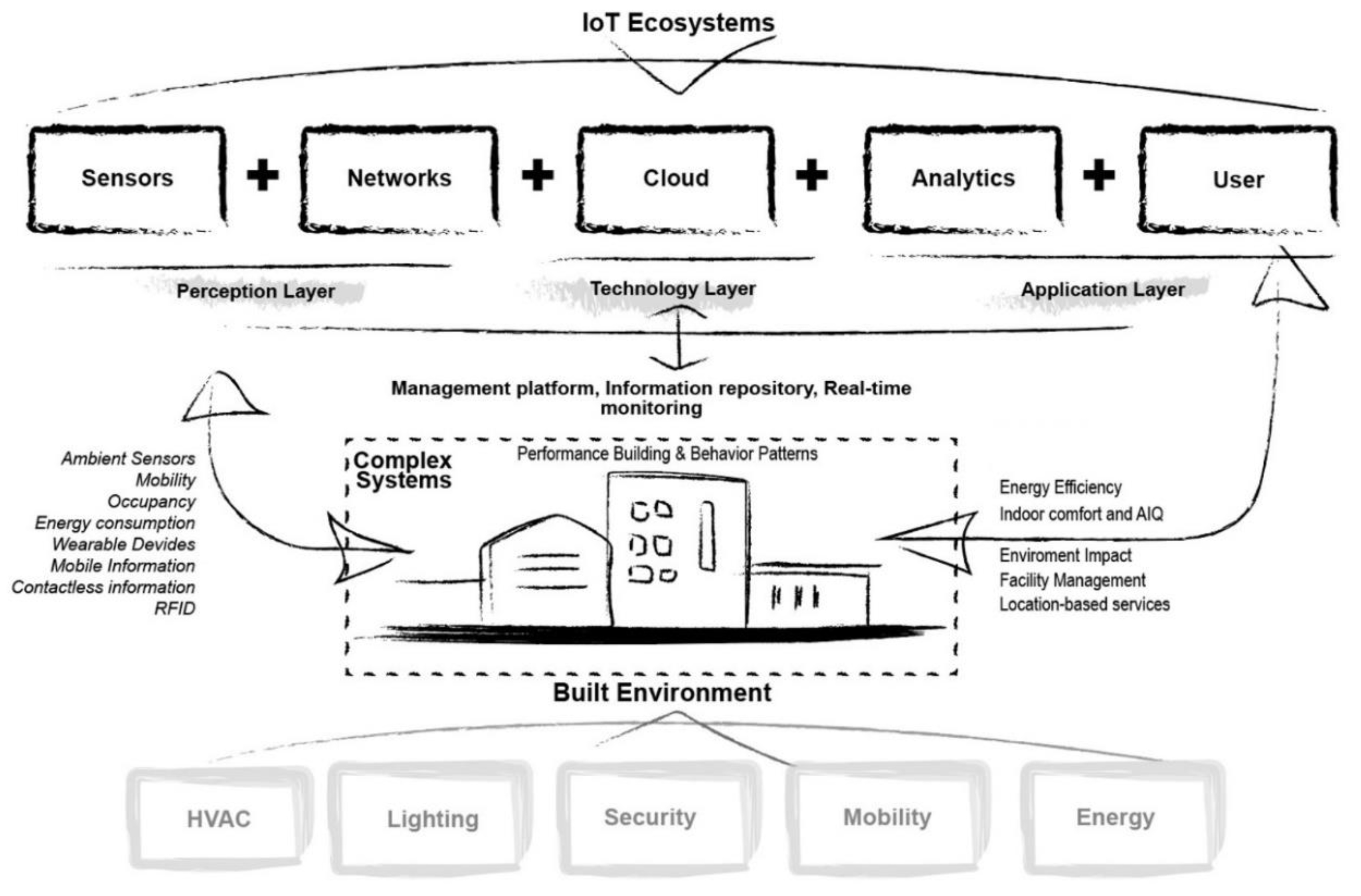

- Sensors. There is a huge variety of sensors to measure parameters of interest in buildings such as (see left area of Figure 1): ambient sensors (CO2, temperature, humidity), mobility, occupancy, energy consumption, wearable devices, mobile information, contactless information (as Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) tags), etc. This work, as it is focused in energy efficiency and IAQ, includes sensors to measure energy consumption (kWh), CO2 level (ppm), temperature (°C), humidity (%) and occupancy (pax). The monitoring spaces have been representatively selected and labelled according their key characteristics, such as: location (floor, building, campus), orientation (north, south, east, west), use (classroom, study room, office, laboratory, library, canteen, etc.), size (big, medium, small), occupancy (high, medium, low), etc. In the specific case of IAQ, although there is a wide range of compounds, factors and situations that affect the IAQ of a building, it is possible to control mechanical ventilation in a building through the use of carbon dioxide (CO2) sensors. These sensors are easy to install and cost-effective, facilitating the straightforward monitoring and detection of CO2 concentration to regulate air exchange and necessary airflow. Additionally, the concentration of CO2 is considered an indirect indicator of air quality as well as the presence of occupants in an enclosed space. When individuals exhale, the levels of CO2 in the environment increase in a manner similar to temperature and Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) increase. In other words, continuous monitoring of CO2 levels in a space enables the automatic adjustment of airflow based on the detected levels. Furthermore, monitoring indoor CO2 enables effective energy management by adjusting the supply of HVAC systems according to the actual occupancy of the space.

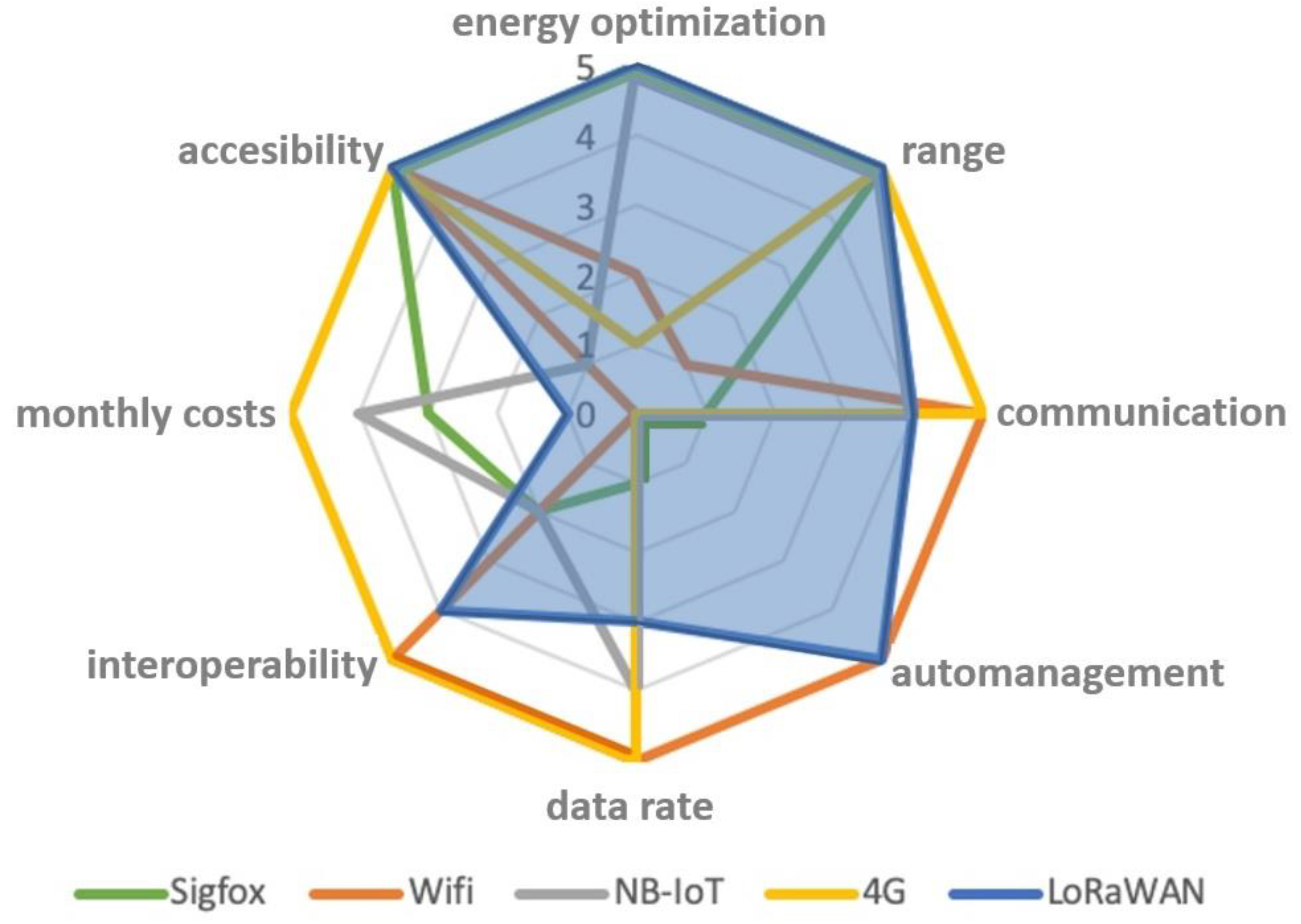

- Networks. Sensors collect data. These collected data are sent to the following communication levels by various interconnected devices through their associated connectivity technologies. There are two main strategies: rely on classical cabled infrastructure centralized in SCADA systems or to use wireless protocols routed to the cloud using specific gateways, such as Wireless Fidelity (WiFi), 4G and Low Power Wide Area Network (LPWAN) technological family such as SigFox, Narrow Band IoT (NB-IoT) and Low Range Wide Area Network (LoRaWAN). Figure 2 shows a performance comparative to determine the most appropriate technology in order to propose homogeneous infrastructures. This comparison shows, among other issues, the importance of battery life and ease of battery replacement. As consequence of minimum maintenance cost and highest energy optimization and coverage range, LoRaWAN technology was selected for this work from the rest of LPWAN technological family. LoRaWAN specification [58] is a networking protocol, designed to wirelessly connect battery operated sensors with bi-directional communication and localization services, that targets other key IoT requirements such as end-to-end security, high interoperability and low monthly costs due to provider network fees.

- Cloud. Cloud computing services use a network layer (to connect remote devices or industrial TCP-IP protocols such as MODBUS-TCP or OPCUA through SCADA systems) with centralized resources (data centers). Currently, there are different types of clouds (public, private, hybrid) and new service models called X as a Service (XaaS), where X can be Software (SaaS), Platform (PaaS), Infrastructure (IaaS), among others. With the popularization of cloud services, the number of devices has exponentially increased. Given that critical and large-scale processes require increasingly fast and effective computational power, a new concept emerges: edge computing. Thus, edge computing refers to how computational processes are performed on or near the peripheral devices (edge). Finally, a third concept arises: fog computing, to refer a decentralized structure in which resources, including data and applications, are located in a logical place between the cloud and the data source. Due to the wide variety of sensors and scenarios in smart buildings, this research has utilized both edge services (for energy measurements considered as big data) and cloud services (for IAQ measurements considered as small data). The IoT ecosystem developed in this work integrates three main functionalities (see middle area in Figure 1): a management platform (to homogenize and control acquired data), an information repository (following the design principles of scalability, flexibility and big data processing), and real-time monitoring (with geopositioned information). Furthermore, these functionalities interconnect with two key services (above detailed): analytics technics (artificial intelligence, machine learning, deep learning and neuronal networks) and applications and services for user experience to offer variability for visualization and interaction through mobile apps, web interfaces, data dashboard with KPIs and other added-value services.

- Analytics. From the information processed and stored in the cloud, many analytics technologies exist for extraction of key factors, real time data exchange, remote monitoring, etc. This is crucial as it provides ubiquitous access, either through platforms or online applications, to real-time levels of CO2, temperature, occupancy, and energy consumption in a specific place, thereby facilitating the monitoring and control of KPIs as well as the subsequent analysis of both user behavior and building performance. In addition, the connection of sensors to the IoT infrastructure of a building enables integration with other systems, such as: (see lower area in Figure 1): HVAC, lighting, security (alarm, fire, etc.), mobility, energy management, etc. This provides facilities for coordination and global optimization of building systems and improves their structure by enhancing their efficiency, safety, wellness and comfort.

- User. From all the data collected by the sensors and the information computed by the analytics, IoT systems visualize knowledge. Report generation or dashboard visualization helps to better understanding of environment behavior and supports the informed decision-making about the aforementioned building systems (HVAC, lighting, security, mobility, energy management, etc.). In this work, the combined analysis (from CO2, temperature, humidity, occupancy and energy consumption) enable the development of management models of energy efficiency and IAQ. With them, smart automation and control systems, both for ventilation and air conditioning systems, can be regulated based on occupancy levels, usage planning, and external environmental conditions. It even allows the development of models that incorporate parameters such as the economic cost of energy, on-site renewable energy production, human behavior, or the environmental impact of the building. Moreover, IoT systems can send real-time alerts or notifications when KPIs reach predefined threshold, and take actions to correct situations, ensure a healthy environment, etc.

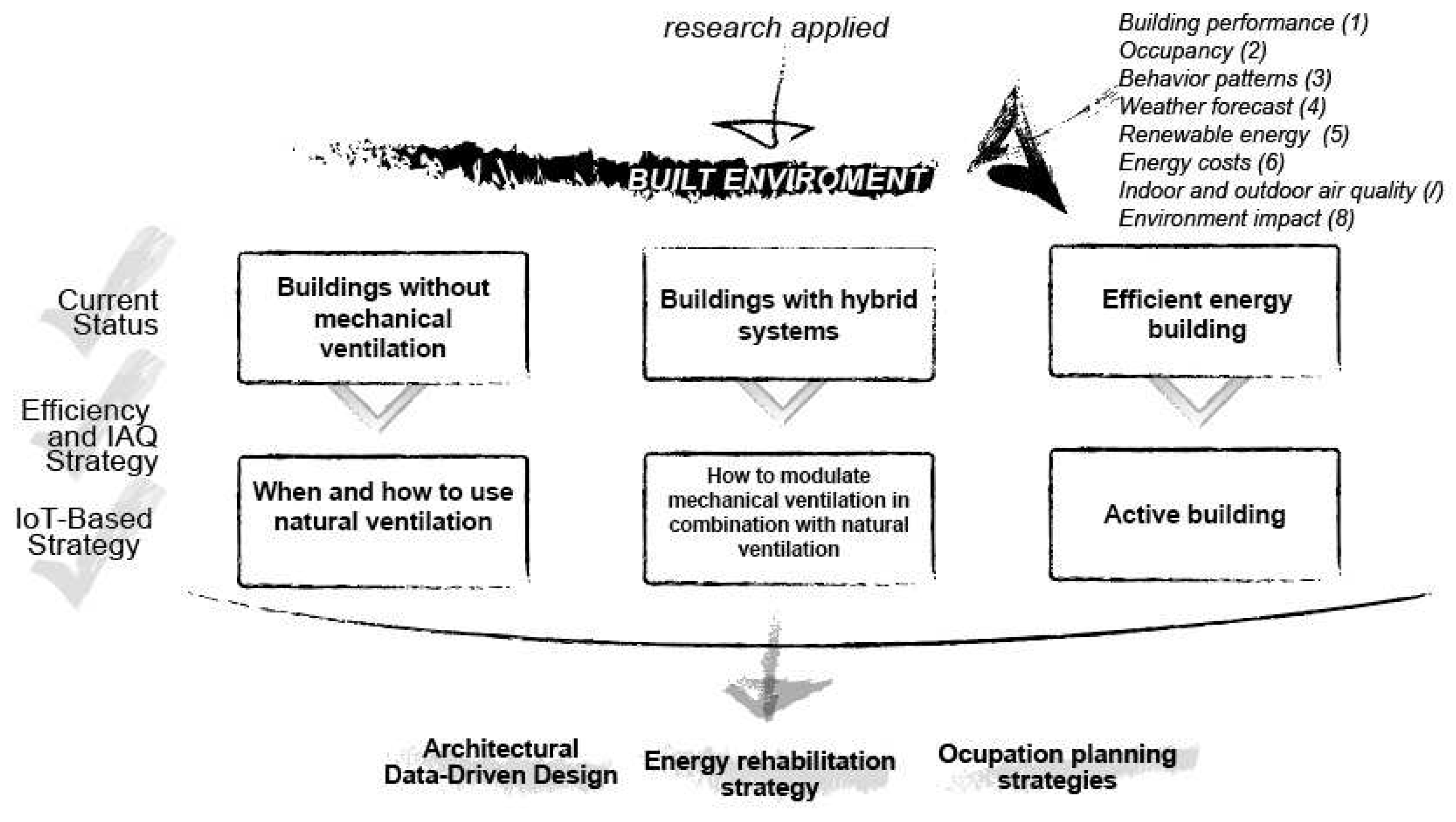

- Buildings without mechanical ventilation, with deficiencies in their insulation both in thermal transmittance of the building envelope and the air permeability.

- Buildings with hybrid systems, which incorporate ventilation and air conditioning systems, either mechanical or hybrid, without CO2 sensors, but with temperature controls in several indoor spaces and with large uncontrolled airflows (either through open windows, open doors, inefficient materials, etc.).

- Efficient energy buildings: a minority of buildings that integrates HVAC systems including high thermal insulation, high-performance windows, heat recovery ventilation equipment and very low-permeability materials.

- Replacement of the building envelope to reduce both energy transfer and air permeability.

- Replacement of the current HVAC systems with more efficient solution by designing a ventilation network, with dual flow and sectorization, to incorporate heat recovery systems.

- Integration of a smart management and control system through IoT ecosystems.

- In buildings without mechanical ventilation, IoT helps to improve IAQ by detecting potentially dangerous concentrations of CO2 (through alarms or visual indicators) and adjusting when and how to use natural ventilation, in combination with available HVAC systems, according to both indoor and outdoor conditions. It allows for manual minimization of energy losses while minimizing health risks.

- In buildings with hybrid systems, IoT enables smart control of the systems, whether centralized or specific to each space. Thus, IoT provides users knowledge about how to modulate mechanical ventilation and HVAC systems in combination with natural ventilation, according to both indoor and outdoor conditions, and regarding with the environmental context.

- In efficient energy buildings, IoT enables precise and smart adjustment of HVAC systems, moving towards the paradigm of active building. IoT informs users when to select natural ventilation, essential to connect people with the environment.

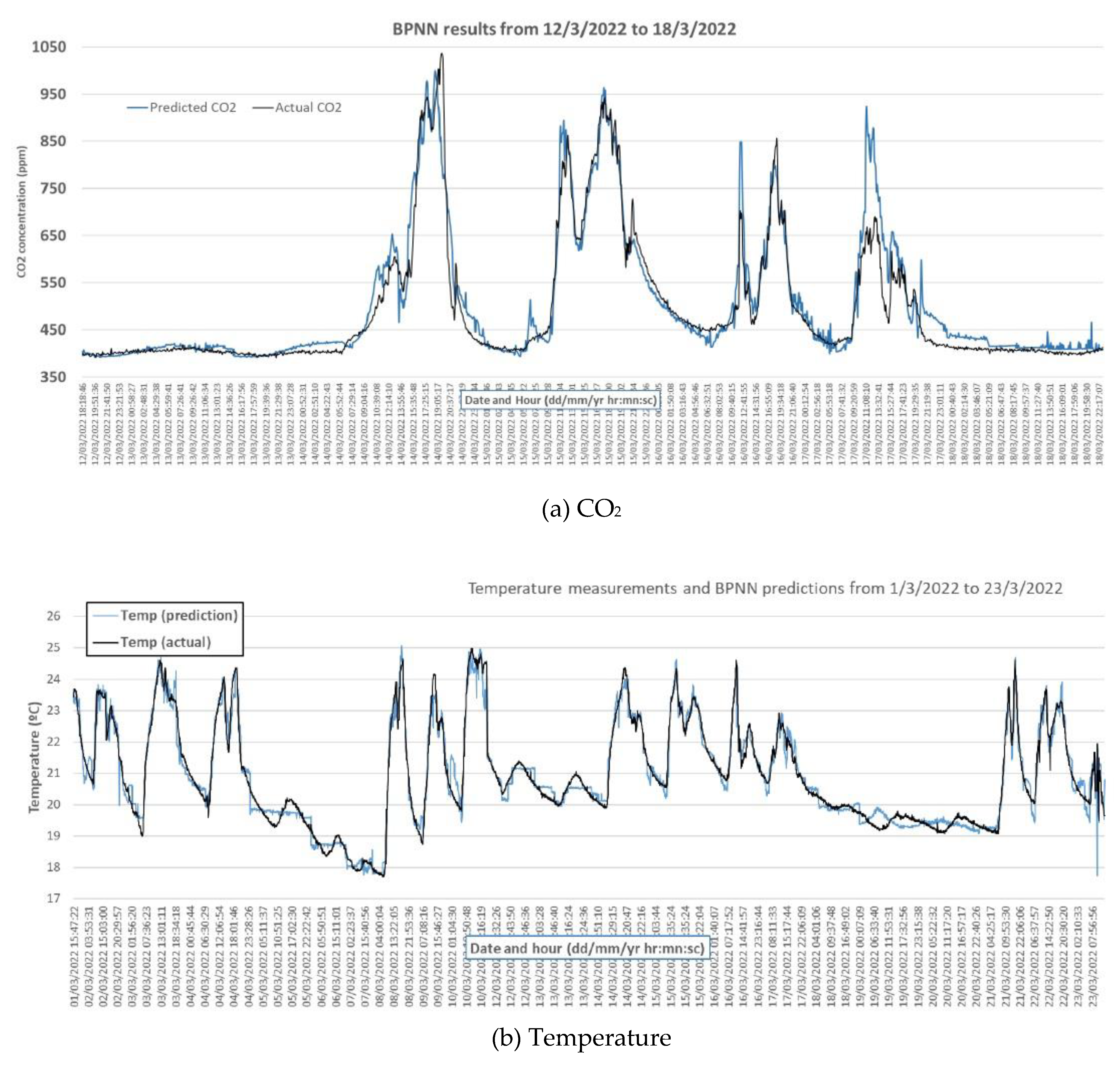

4. Results and Discussion

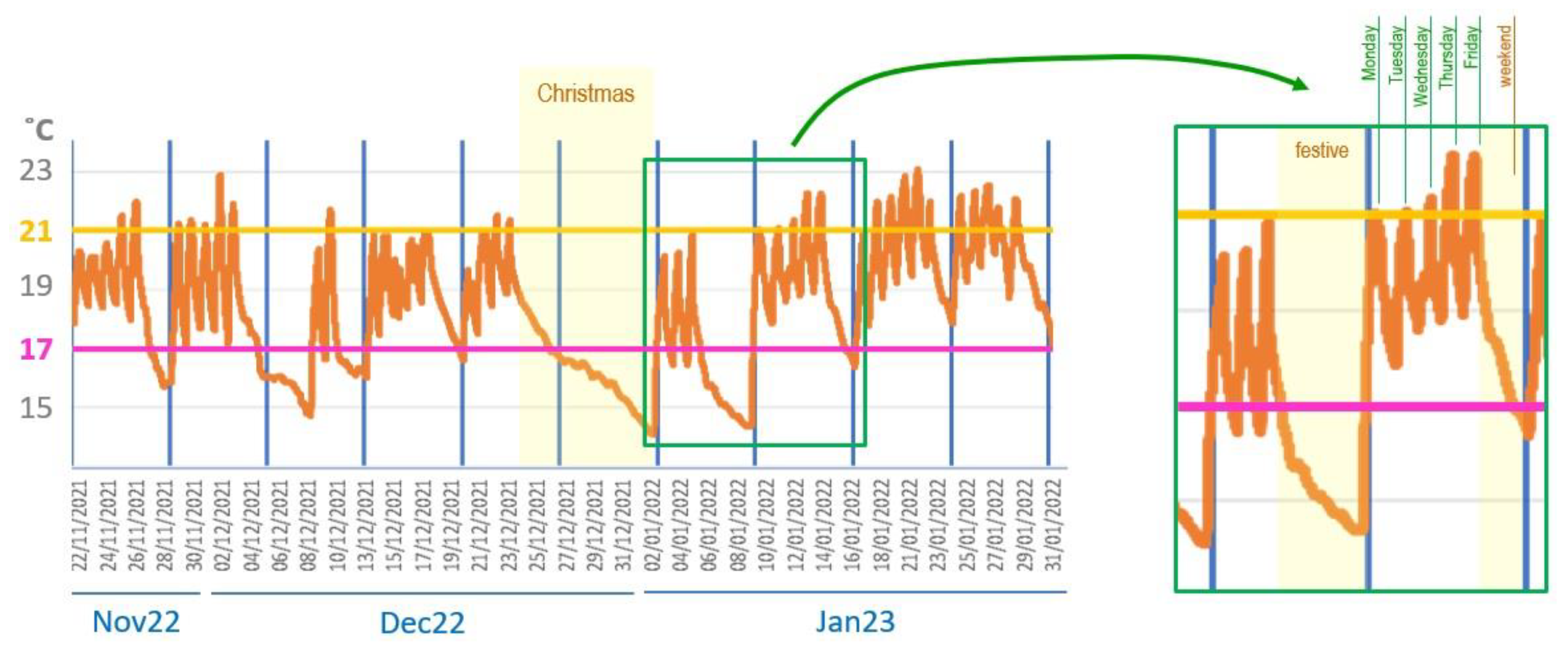

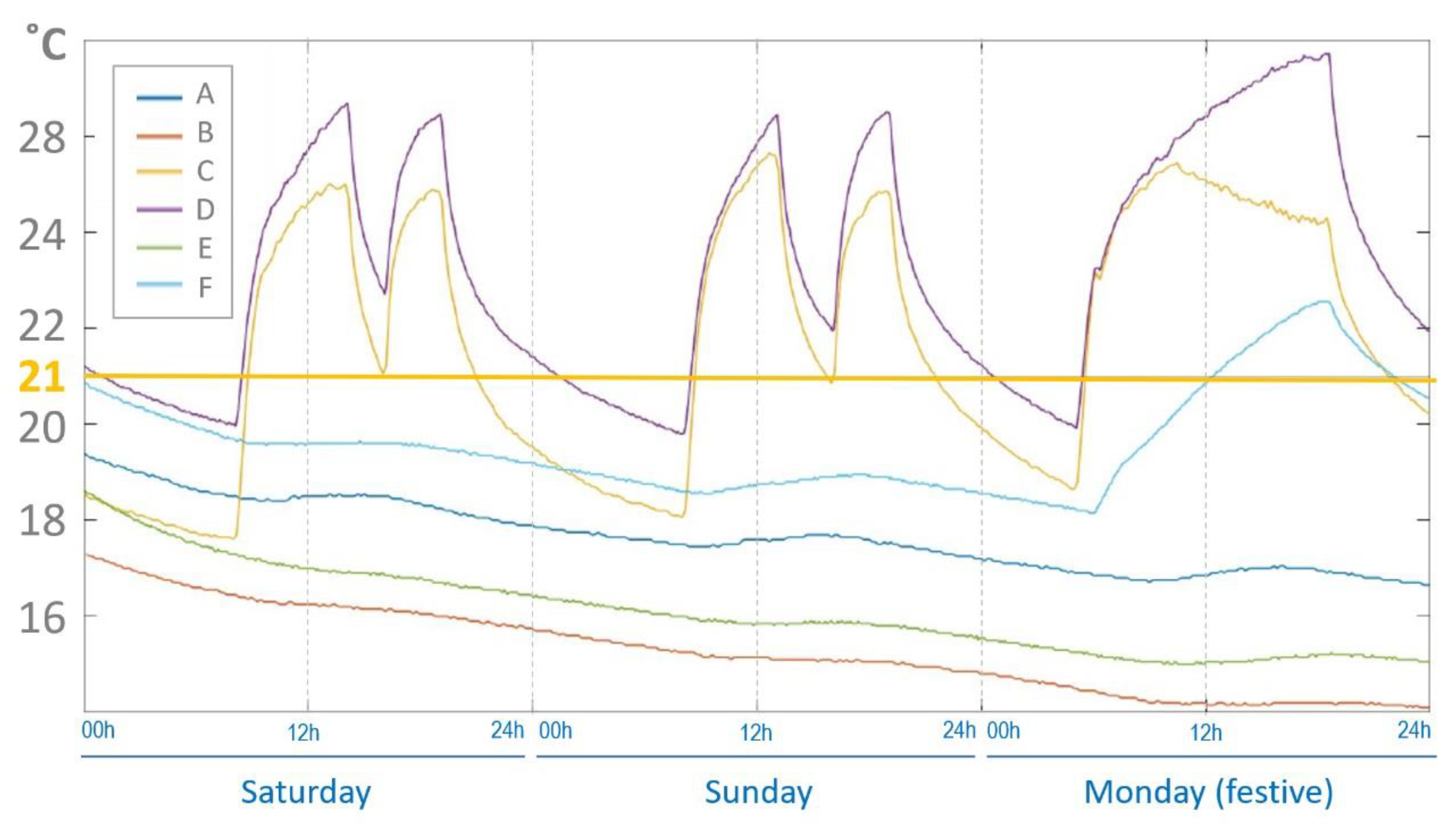

- Every week there is an increase in the average daily temperature (as a sawtooth) which helps to explain the thermal inertia of the building behavior. It is very interesting to know this behavior because, by measuring the daily maximums and minimums according to each day of the week and comparing the graph with the 21°C threshold, it is possible to estimate the savings potential. According to the measurements obtained, the implementation of an IoT-managed HVAC system should imply savings between 10 and 15% of total energy consumption.

- During weekends, festive days and holydays as Christmas (areas shaded in yellow color), average temperatures drop below the 17°C threshold. Thus, the start of each week on Monday implies a significant energy consumption to increase temperatures to thermal comfort zone (between 19 and 21°C according to [60]). It is very interesting to quantify this energy consumption in order to analyze diverse strategies that would avoid an excessive decrease of building temperature and thus it would not be necessary to overcome a very high slope at the beginning of each week.

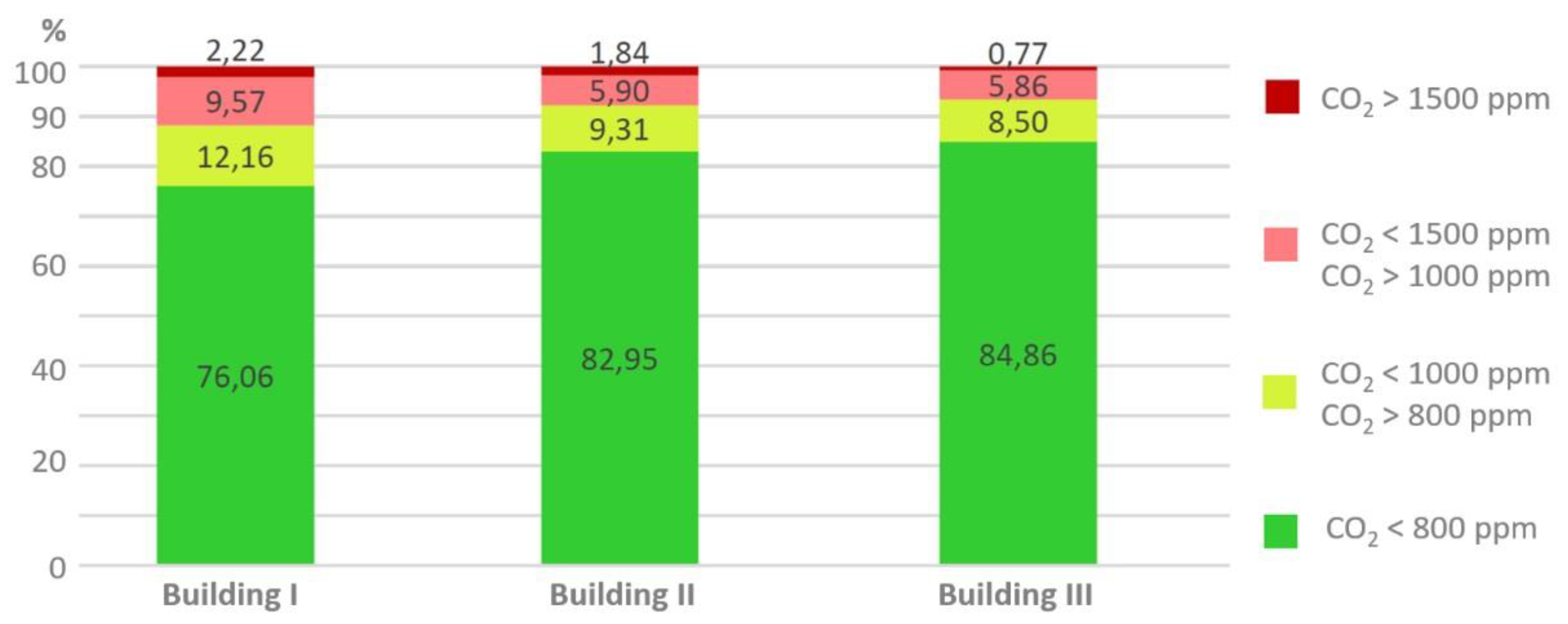

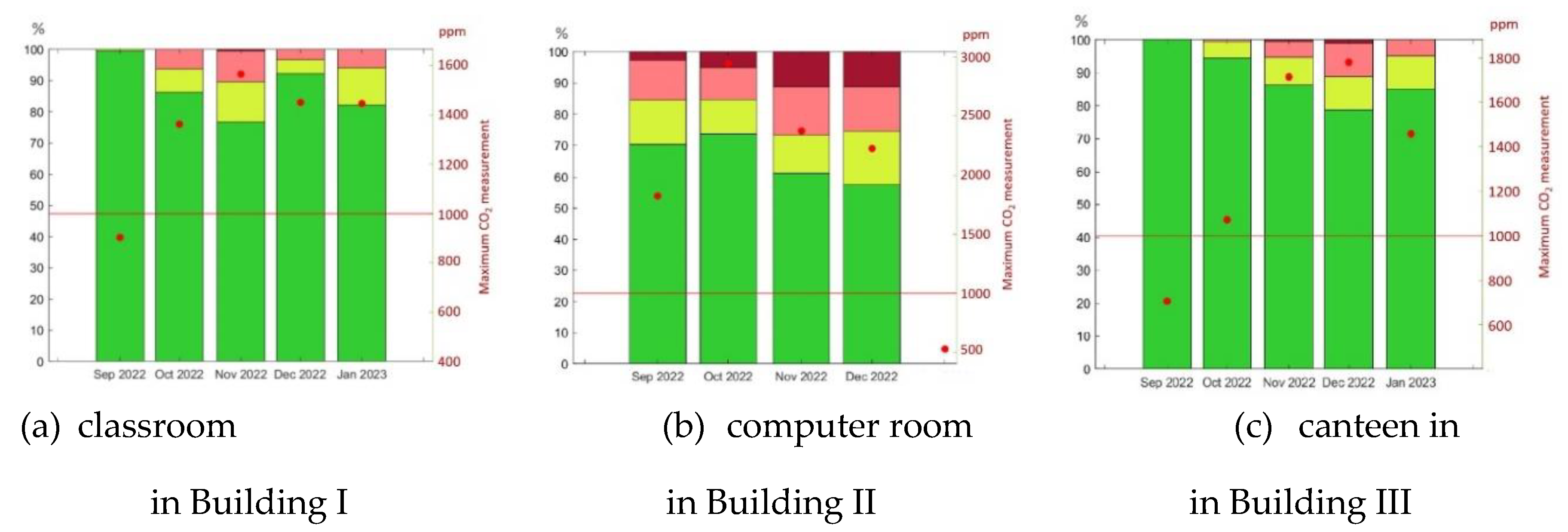

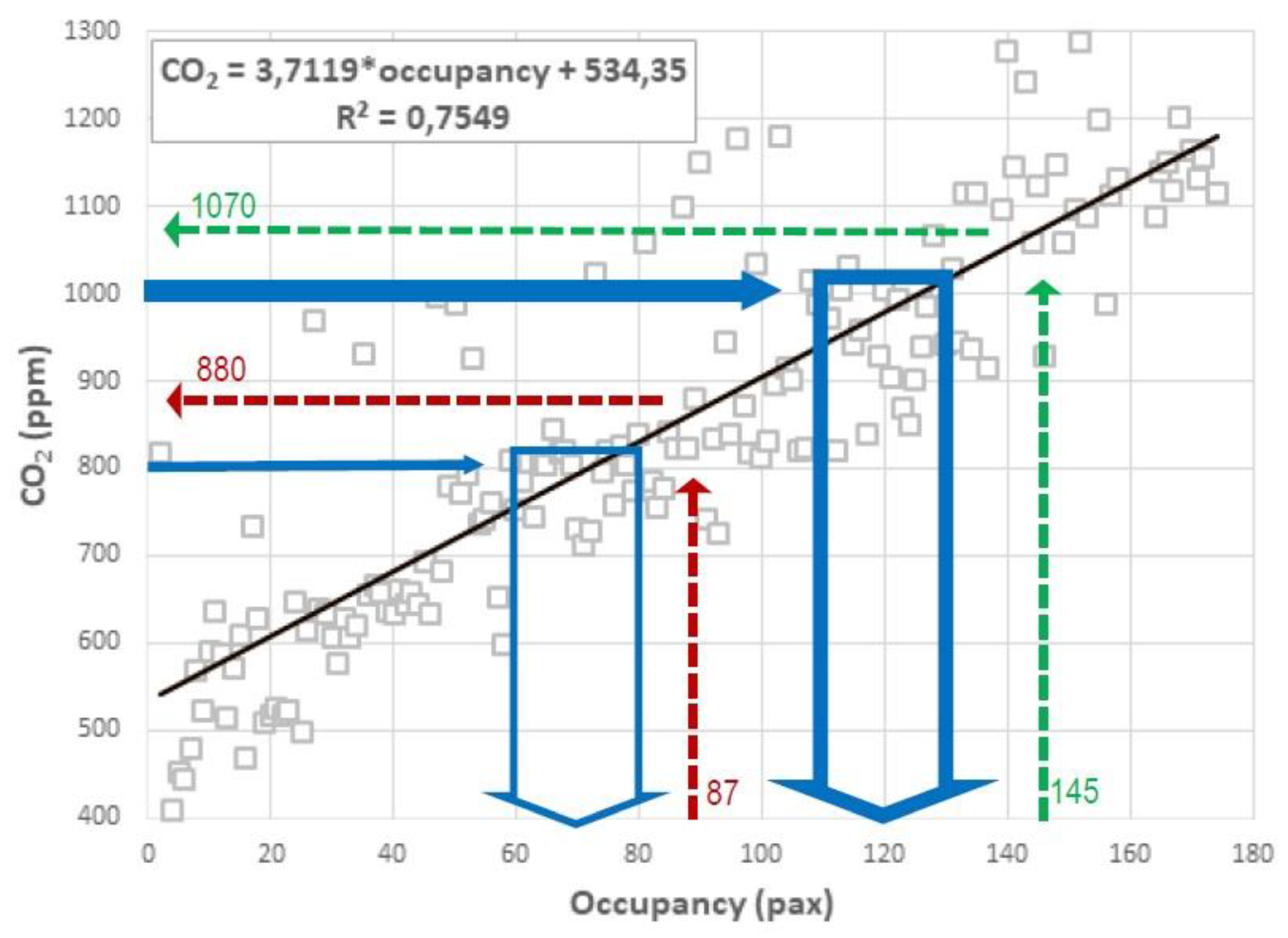

- To collect quantitative CO2 concentration and occupation for a representative period of time.

- To obtain a correlation between the maximum values of CO2 and occupancy.

- To establish the maximum acceptable for CO2 concentration and therefore the adequate air ventilation rate in order to establish the capacity for each room/classroom.

5. Conclusions

- IoT helps to understand user behavior patterns to adjust energy production to real demand; and vice versa, to understand how building processes energy, enabling changes in the behavior patterns of their managers and users.

- By combining real data from energy, CO2, temperature and occupancy, IoT helps to understand buildings as complex systems in a specific climatic location to perform models, simulations and predictions towards the paradigm of digital twins. Thus, IoT monitoring provides the knowledge to characterize the built environment (since information to create a digital model is not always available) avoiding difficult-to-access data, such as: construction materials, architectonic decisions, thermal bridges, uncontrolled infiltrations, windows efficiency, HVAC performance, among others.

- IoT provides detailed analysis for each specific case, use and space to define the best energy retrofit strategy. For each building, IoT quantifies which energy improvement strategy should better impact on reducing energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions.

- IoT easily detects anomalies, energy leaks, airflow, unused spaces, open windows, etc. as well as inefficiencies in HVAC systems or maintenance failures, among other potential malfunctions.

- IoT enables a smart management when it interoperates with the building systems: HVAC, SCADA, lighting, security, mobility, climate regulation, home automation, access control, etc.

- IoT ecosystems, when interconnected on a larger scale (city, region, country, etc.), provide sociodemographic studies and analysis of how buildings are used, enabling knowledge-driven decisions for global rehabilitation strategies. Mobility and communities are closely interconnected, providing insights into how users invest time and energy.

Funding

Acknowledgements

References

- European Court of Auditors, Energy efficiency in buildings: greater focus on cost-effectiveness still needed, Luxembourg, 2020. https://op.europa.eu/webpub/eca/special-reports/energy-efficiency-11-2020/en/index.html. (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Eurostat. Statistics Explained, Final energy consumption by sector, EU, 2021, Eurostat. (2023). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Final_energy_consumption_by_sector,_EU,_2021,_(%25_of_total,_based_on_terajoules).PNG. (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT, Climate Mainstreaming Architecture in the 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework, Brussels, 2022. https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2022-06/swd_2022_225_climate_mainstreaming_architecture_2021-2027.pdf. (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- General Secretariat of the Council, Building a sustainable Europe by 2030 – Progress thus far and next steps - Council conclusions (10 December 2019), Brussels, 2019. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/41693/se-st14835-en19.pdf. (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- United States Environment Protection Agency (EPA), Why Indoor Air Quality is Important to Schools, (2022). https://www.epa.gov/iaq-schools/why-indoor-air-quality-important-schools. (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Joint Research Centre, Indoor air pollution: new EU research reveals higher risks than previously thought, Brussels, 2003. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_03_1278. (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL, Consolidated text: Directive 2010/31/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 May 2010 on the energy performance of buildings (recast), 2021.

- D. Evans, The Internet of Things. How the Next Evolution of the Internet is Changing Everything, 2011. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.cisco.com/c/dam/en_us/about/ac79/docs/innov/IoT_IBSG_0411FINAL.pdf. (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- R. van der Meulen, Gartner Says 6.4 Billion Connected “Things” Will Be in Use in 2016, Up 30 Percent From 2015, Gartner. (2015). https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2015-11-10-gartner-says-6-billion-connected-things-will-be-in-use-in-2016-up-30-percent-from-2015. (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Q. Ashraf, M. Q. Ashraf, M. Yusoff, A. Azman, N. Nor, N. Fuzi, M. Saharedan, N. Omar, Energy monitoring prototype for Internet of Things: Preliminary results, 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Atzori, A. Iera, G. Morabito, The Internet of Things: A survey, Computer Networks. 54 (2010) 2787–2805. [CrossRef]

- S. Tang, D.R. S. Tang, D.R. Shelden, C.M. Eastman, P. Pishdad-Bozorgi, X. Gao, A review of building information modeling (BIM) and the internet of things (IoT) devices integration: Present status and future trends, Autom Constr. 101 (2019) 127–139. [CrossRef]

- K. Lawal, H.N. K. Lawal, H.N. Rafsanjani, Trends, benefits, risks, and challenges of IoT implementation in residential and commercial buildings, Energy and Built Environment. 3 (2022) 251–266. [CrossRef]

- M. Poongothai, P.M. M. Poongothai, P.M. Subramanian, A. Rajeswari, Design and implementation of IoT based smart laboratory, in: 2018 5th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Applications (ICIEA), IEEE, 2018: pp. 169–173. [CrossRef]

- T.I.P. on C.C. IPCC, Mitigation of Climate Change Climate Change 2022 Working Group III contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2022. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/05/uncertainty-guidance-note.pdf. (accessed on 17 July 2022).

- United Nations, Climate Change, United Nations. Global Issues. (n.d.). https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/climate-change (accessed on , 2023). 14 June.

- European Commission, Paris Agreement, European Commission. Climate Action. (2016). https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/international-action-climate-change/climate-negotiations/paris-agreement_en. (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- A.H. Oti, E. A.H. Oti, E. Kurul, F. Cheung, J.H.M. Tah, A framework for the utilization of Building Management System data in building information models for building design and operation, Autom Constr. 72 (2016) 195–210. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Sesana, G. M.M. Sesana, G. Salvalai, A review on Building Renovation Passport: Potentialities and barriers on current initiatives, Energy Build. 173 (2018) 195–205. [CrossRef]

- United Nations, United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, (n.d.). https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/. (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- A.P. Batista, M.E.A. A.P. Batista, M.E.A. Freitas, F.G. Jota, Evaluation and improvement of the energy performance of a building’s equipment and subsystems through continuous monitoring, Energy Build. 75 (2014) 368–381. [CrossRef]

- C. Piselli, A.L. C. Piselli, A.L. Pisello, Occupant behavior long-term continuous monitoring integrated to prediction models: Impact on office building energy performance, Energy. 176 (2019) 667–681. [CrossRef]

- P. Li, T. P. Li, T. Parkinson, S. Schiavon, T.M. Froese, R. de Dear, A. Rysanek, S. Staub-French, Improved long-term thermal comfort indices for continuous monitoring, Energy Build. 224 (2020) 110270. [CrossRef]

- P.A. Fokaides, C. P.A. Fokaides, C. Panteli, A. Panayidou, How Are the Smart Readiness Indicators Expected to Affect the Energy Performance of Buildings: First Evidence and Perspectives, Sustainability. 12 (2020) 9496. [CrossRef]

- C.A. Balaras, K.G. C.A. Balaras, K.G. Droutsa, E.G. Dascalaki, S. Kontoyiannidis, A. Moro, E. Bazzan, Urban Sustainability Audits and Ratings of the Built Environment, Energies (Basel). 12 (2019) 4243. [CrossRef]

- General Secretariat of the Council, Building a sustainable Europe by 2030 – Progress thus far and next steps - Council conclusions, Brussels, 2019. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/41693/se-st14835-en19.pdf. (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- ASHRAE, ASHRAE Position Document on Indoor Carbon Dioxide, Georgia, 2022. https://www.ashrae.org/file%20library/about/position%20documents/pd_indoorcarbondioxide_2022.pdf. (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Persily, A. Development and application of an indoor carbon dioxide metric, Indoor Air. 32 ( 2022. [CrossRef]

- Batterman, S. Review and Extension of CO2-Based Methods to Determine Ventilation Rates with Application to School Classrooms, Int J Environ Res Public Health. 14 (2017) 145. [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Leccese, F. Measurement of CO2 concentration for occupancy estimation in educational buildings with energy efficiency purposes, Journal of Building Engineering. 32 (2020) 101714. [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Schito, E. Definition of Optimal Ventilation Rates for Balancing Comfort and Energy Use in Indoor Spaces Using CO2 Concentration Data, Buildings. 10 (2020) 135. [CrossRef]

- Kabirikopaei, A.; Lau, J. Uncertainty analysis of various CO2-Based tracer-gas methods for estimating seasonal ventilation rates in classrooms with different mechanical systems, Build Environ. 179 (2020) 107003. [CrossRef]

- Kabirikopaei, A.; Lau, J. Uncertainty analysis of various CO2-Based tracer-gas methods for estimating seasonal ventilation rates in classrooms with different mechanical systems, Build Environ. 179 (2020) 107003. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, M.J.; Wolf, S.; Jørgensen, R.B.; Madsen, H.; Mathisen, H.M. A methodology for the selection of pollutants for ensuring good indoor air quality using the de-trended cross-correlation function, Build Environ. 209 (2022) 108668. [CrossRef]

- Morawska, L.; Allen, J.; Bahnfleth, W.; Bluyssen, P.M.; Boerstra, A.; Buonanno, G.; Cao, J.; Dancer, S.J.; Floto, A.; Franchimon, F.; et al. A paradigm shift to combat indoor respiratory infection, Science (1979). 372 (2021) 689–691. [CrossRef]

- Européenne, C.; de l’énergie, D.G.; Durier, F.; De Strycker, M.; Guyot, G.; Sherman, M.; Leprince, V.; Urbani, M.; De Blaere, B.; Mélois, A.; Selle-Marquis, P.; Janssens, A.; Decorte, Y.; Wouters, P. Technical study on the possible introduction of inspection of stand-alone ventilation systems in buildings : final report, Publications Office, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, T.-Y.; Zhao, G.; Guizani, M. Efficient Rule Engine for Smart Building Systems, IEEE Transactions on Computers. 64 (2015) 1658–1669. [CrossRef]

- Çıdık, M.S.; Phillips, S. Buildings as complex systems: the impact of organisational culture on building safety, Construction Management and Economics. 39 (2021) 972–987. [CrossRef]

- Uriarte, I.; Erkoreka, A.; Legorburu, A.; Martin-Escudero, K.; Giraldo-Soto, C.; Odriozola-Maritorena, M. Decoupling the heat loss coefficient of an in-use office building into its transmission and infiltration heat loss coefficients, Journal of Building Engineering. 43 (2021) 102591. [CrossRef]

- Herrando, M.; Cambra, D.; Navarro, M.; de la Cruz, L.; Millán, G.; Zabalza, I. Energy Performance Certification of Faculty Buildings in Spain: The gap between estimated and real energy consumption, Energy Convers Manag. 125 (2016) 141–153. [CrossRef]

- P.X.W. Zou, X. P.X.W. Zou, X. Xu, J. Sanjayan, J. Wang, Review of 10 years research on building energy performance gap: Life-cycle and stakeholder perspectives, Energy Build. 178 (2018) 165–181. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, A.; Kämpf, J.; Vicente, R.; Oliveira, R.; Silva, T. Comparison between monitored and simulated data using evolutionary algorithms: Reducing the performance gap in dynamic building simulation, Journal of Building Engineering. 17 (2018) 96–106. [CrossRef]

- Taheri, S.; Hosseini, P.; Razban, A. Model predictive control of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems: A state-of-the-art review, Journal of Building Engineering. 60 (2022) 105067. [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Cheng, Y.; Lin, Z. Modelling indoor environment indicators using artificial neural network in the stratified environments, Build Environ. 208 (2022) 108581. [CrossRef]

- Tagliabue, L.C.; Cecconi, F.R.; Rinaldi, S.; Ciribini, A.L.C. Data driven indoor air quality prediction in educational facilities based on IoT network, Energy Build. 236 (2021) 110782. [CrossRef]

- Afroz, Z.; Shafiullah, G.M.; Urmee, T.; Shoeb, M.A.; Higgins, G. Predictive modelling and optimization of HVAC systems using neural network and particle swarm optimization algorithm, Build Environ. 209 (2022) 108681. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Renovation wave. Renovating the EU building stock will improve energy efficiency while driving the clean energy transition, European Commission. (2020). https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-efficiency/energy-efficient-buildings/renovation-wave_en (accessed on , 2023). 14 June.

- Eurpean Commission, In focus: Energy efficiency in buildings, Eurpean Commission. (2020). https://commission.europa.eu/news/focus-energy-efficiency-buildings-2020-02-17_en. (accessed on 14 June 2023).

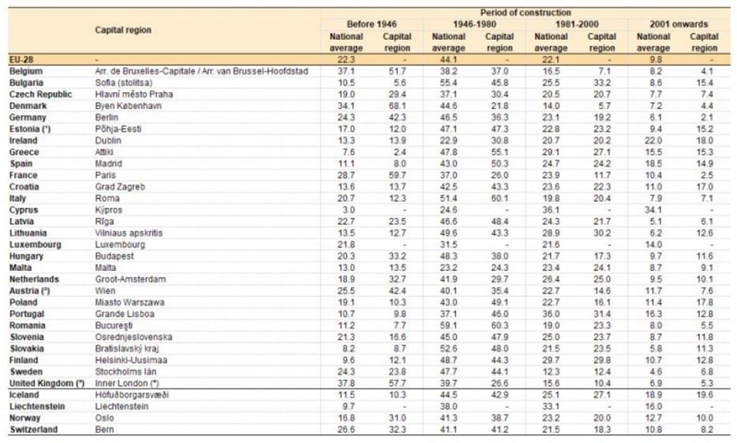

- Eurotstat Statistics Explained, Dwellings by period of construction, national averages and capital regions, 2011, Eurotstat. (2011). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Dwellings_by_period_of_construction,_national_averages_and_capital_regions,_2011_(%25_share_of_all_dwellings)_PITEU17.png. (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Korberg, A.D.; Thellufsen, J.Z.; Skov, I.R.; Chang, M.; Paardekooper, S.; Lund, H.; Mathiesen, B.V. On the feasibility of direct hydrogen utilisation in a fossil-free Europe, Int J Hydrogen Energy. 48 (2023) 2877–2891. [CrossRef]

- Rosenow, J. Is heating homes with hydrogen all but a pipe dream? 6 (2022) 2225–2228. [CrossRef]

- Commission, E.; Centre, J.R. Atlas of the human planet 2020 : open geoinformation for research, policy, and action, Publications Office, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Statistic Explained, Heating and cooling degree days - statistics, Eurostat. (2023). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Heating_and_cooling_degree_days_-_statistics. (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Quefelec, S. Cooling buildings sustainably in Europe: exploring the links between climate change mitigation and adaptation, and their social impacts, European Environment Agency. (2022). https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/cooling-buildings-sustainably-in-europe. (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- International Energy Agency, The Future of Cooling Opportunities for energyefficient air conditioning, 2018.

- European Commission, Smart Readiness Indicator (SRI) for Buildings, (2018). https://smartreadinessindicator.eu/. (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- European Commission, Outcomes of the first technical study about SRI, (2018). https://smartreadinessindicator.eu/1st-technical-study-outcome. (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- LoRa Alliance, What is LoRaWAN Specification, LoRa Alliance. (2023). https://lora-alliance.org/about-lorawan/. (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Martínez, I.; Zalba, B.; Trillo-Lado, R.; Blanco, T.; Cambra, D.; Casas, R. Internet of Things (IoT) as Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Enabling Technology towards Smart Readiness Indicators (SRI) for University Buildings, Sustainability. 13 (2021) 7647. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de la Presidencia, Real Decreto 1826/2009, de 27 de noviembre, por el que se modifica el Reglamento de instalaciones térmicas en los edificios, aprobado por Real Decreto 1027/2007, de 20 de julio, Documento BOE-A-2009-19915, Spain, 2009.

- MATLAB & Simulink - MathWorks, Fit Data with a Shallow Neural Network, (2023). https://es.mathworks.com/help/deeplearning/gs/fit-data-with-a-neural-network.html. (accessed on 28 June 2023).

| Scale (Level) | Stakeholders | Services for Users | IoT Functionalities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space (personal) |

User | Knowledge of the environmental parameters (IAQ, temperature, humidity, occupancy) of specific spaces based on their activities, habits and preferences. | Automation based on user behavior patterns. Adjustment of HVAC systems to certain environmental parameters, energy prices, renewable energy production, etc. |

| Building (community) |

Architect | Design based on buildings behavior patterns according to each specific feature. | Smart design based on real data obtained from IoT monitoring, integrating passive and active building systems. |

| Engineer | Design of the most appropriate energy solution based on the behavior parameters of building and users and available energy sources. Choice of the best combination between on-site renewable energy generation systems, air condition needs, and type of HVAC solution. |

Real-time adaptation to the multiple and diverse situations that can occur within a building. |

|

| Neighborhood (intra-local) |

Urbanist | Appropriate solutions, for each specific situation, to propose the best energy strategy and/or energy rehabilitation of new/existing neighborhoods. | Continuous monitoring of neighborhoods to obtain data and behavior patterns with which to characterize local policies and automatic systems customized to the neighborhood scale. |

| City (local) |

Local institutions |

Urban policies and plans to implement adequate and customized solutions for each city. | Smart infrastructures. Smart environments. Smart governance. Smart cities. |

| Region (intra-national) |

Epidemiologist Doctor | Correlation of IAQ and environmental parameters with the spread of certain diseases. | Simulation and evaluation of different data-driven public health policies. |

| Country (national) |

National institutions |

Data from behavior patterns to develop global strategies of energy rehabilitation, electric production and CO2 management. | Simulation of scenarios and evaluation of the national strategies about the built environment with social implications. |

| Zone (inter-national) |

International institutions |

Data to implement global strategies for energy consumption based on the energy availability, social equality and climate change. | Simulation of scenarios and evaluation of the international strategies about the built environment with social implications. |

| Time (gmt+2) | CO2 (ppm) |

Temperature (˚C) |

Humidity (%) |

Occupancy (pax) |

Accumulated occupancy (pax) |

CO2 prediction (ppm) |

Temperature prediction (˚C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18:25:02 | 776 | 23,00 | 45 | 104 | 614 | 819 | 22,73 |

| 18:30:03 | 735 | 22,86 | 44 | 101 | 620 | 800 | 23,01 |

| 18:35:04 | 719 | 22,78 | 44 | 99 | 620 | 785 | 23,00 |

| 18:40:03 | 711 | 22,76 | 44 | 101 | 621 | 786 | 22,95 |

| 18:45:03 | 718 | 22,78 | 44 | 98 | 614 | 781 | 22,98 |

| 18:50:02 | 738 | 22,78 | 44 | 94 | 597 | 771 | 23,01 |

| 18:55:04 | 756 | 22,81 | 44 | 83 | 576 | 759 | 23,17 |

| 19:00:03 | 757 | 22,74 | 44 | 76 | 551 | 739 | 23,16 |

| 19:05:03 | 752 | 22,72 | 44 | 80 | 532 | 738 | 22,93 |

| 19:10:03 | 756 | 22,72 | 44 | 80 | 511 | 739 | 22,80 |

| 19:15:03 | 783 | 22,64 | 44 | 74 | 487 | 714 | 22,86 |

| 19:20:03 | 797 | 22,64 | 44 | 74 | 467 | 713 | 22,77 |

| 19:25:03 | 784 | 22,58 | 45 | 82 | 466 | 709 | 22,29 |

| 19:30:04 | 775 | 22,56 | 45 | 85 | 475 | 714 | 22,25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).