1. Introduction

Leachate is a liquid from the decomposition of solid waste that is generally found in landfills where precipitation in the area has an impact, producing an infiltration that affects the soil and bodies of water [

1]; it is necessary that the leachate is purified before dumping to avoid environmental problems and achieve a better operation of the landfill taking advantage of the use of biogas [

2]. Within the characterization of landfill leachate, organic, inorganic, and heavy metal compounds can be found; according to the age of the landfill, the leachate becomes more alkaline and present a high concentration of dissolved solids product of inorganic compounds, anions such as chloride, nitrate and phosphates and cations such as sodium, magnesium, calcium, and iron [

3], these pollutants upon reaching water bodies are a clear tracer of landfill leachate, for such reason processes are proposed to eliminate them in their generation.

Leachate discharges to water bodies is a problem that has been considered for some years, several treatment alternatives have been proposed, often using techniques for wastewater treatment [

4], such as biological processes, but these have their limitations due to the low concentration of biodegradable compounds, the BOD5/DQO ratio as the lifetime of the landfill passes is increasingly lower, and if to this is added the presence of toxic compounds that inhibit the treatment biological processes do not give good results in individual, so composite processes that integrate aeration, coagulation-flocculation and membrane treatments such as reverse osmosis have been tested [

5,

6]. The coagulation-flocculation process has been widely accepted because of the characteristics possessed by the leachates and because of its relative simplicity in both application and evaluation by measuring turbidity as a result of the process [

7]. Perhaps the initial complexity of a jar test is the biggest problem for the application of this method since the characteristics of the leachate evolve with the passage of time and external characteristics, which is why the jar test must be recurrent and periodic.

Primary treatment is a chemical treatment used in leachate treatment to enhance the removal of suspended solids, organic matter and nutrients. In the process, chemical coagulants are usually added to primary sedimentation. This process can help reduce the loading rate of solids and organic matter in biological treatment, treatment infrastructure requirements and total cost [

8]. Efficiency in a primary treatment facility depends on the type and dosage of coagulant, pH level, temperature and alkalinity [

9]. For these reasons, it is essential to know the age of the leachate depending on the sampling location within the landfill and the initial characteristics before applying the treatments. Coagulation-flocculation as a primary treatment can be effective removing COD, color, turbidity and metals depending on the type of coagulant/flocculants and on the contaminants to remove [

10]–[

12]

Environmental processes are commonly represented by non-linear behavior which leads to applying non-linear complex models, due to analytical solutions are not capable to solve them. Mathematical models in wastewater treatments allow processes to become predictable and at the same time these can be optimized saving money and time. Recently, studies have been conducted to model water and wastewater treatment processes using machine learning (ML) data-driven models, such as decision tree (DT), artificial neural network (ANN), support vector machine (SVM), and Random Forest (RF) methods [

13]–[

21] This highlights the great use that can be made of these techniques to optimize processes focused on water treatment.

Machine learning models mostly used to model wastewater treatments are ANN. ANN has been widely used in environmental disciplines, this technique is an effective data drive tool that helps to model different environmental processes [

22,

23]. ANN is trained to be capable to simulate non-linear relations between input and output variables based on experimental data [

24] to give results close to the output target variable [

25]. On the other hand, SVM is categorized as a new neural network algorithm used for forecasting, it is applied for classification and regression problems as a nonlinear and kernel-based modeling approach [

26]. Also, SVM can simultaneously minimize estimation residuals, minimizing the upper limit of generalization error by improving the generalizability of traditional models [

26]. Likewise, KNN is one of the easiest and simplest learning algorithms, it works with regression and classification as supervised learning approaches, the classification process is done using the highest vote of the

k closest training points [

27].

This research experimental proposes an alternative to optimize the jar test and decrease the test application time through the use of machine learning techniques such as: Artificial Neural Networks, Support Vector Machine and K-nearest neighbor. For this purpose, the leachate treatment process is simulated by adding coagulant in various concentrations. To then apply statistical methods in the validation of the models applied, with the purpose of simplifying the subsequent treatment process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The leachate sample was taken at the "Pichacay" landfill. The Pichacay Landfill is located in the Santa Ana parish, in the town of Pichacay, 21 km from the city of Cuenca, in the province of Azuay, since 2001.

Figure 1 shows the location of the landfill where the samples were collected.

This landfill operates under public administration and serves seven of the 15 cantons of the province of Azuay: El Pan, Sevilla de Oro, Guachapala, Sigsig, Chordeleg, Gualaceo and Cuenca, burying approximately 92.7% of the total solid waste [

28].

2.2. Leachate sample

The samples were collected directly in the North 2 phase, the leachate generated in the cells reaches a pipe, which is easily accessible. About 10 gallons of leachate sample was collected to provide sufficient quantity for multiple tests. They were then taken to the HYDROLAB water quality laboratory at the Catholic University of Cuenca, stored at 4 ◦C prior to further testing and analysis.

Table 1 shows the raw leachate characterization values. The parameters analyzed indicate an alkaline leachate, with pH values above neutral (>7). The values for COD, BOD and nutrients are not as high as those reported by other studies such as Patel [

29], in this context it is necessary to analyze the age of the leachate, which is a fundamental parameter in the composition of the liquid.

For the process of coagulation and flocculation of the leachate we work with hexahydrated ferric chloride (100.3%) and as a control parameter of the efficiency we have measured the turbidity in NTU. This coagulant was chosen because it is industrially accepted and widely applied in water and wastewater treatment in primary treatment. Stock solutions of the coagulants were prepared and stored at 4 ◦C for experimental use. The concentration of prepared stock solutions of ferric chloride was 8.5 g/L. Application of stock solution is preferred compared to adding solid coagulant for testing since the dissolved coagulants can mix rapidly compared to the solid coagulant [

30].

In addition to working with ferric chloride, the use of a biopolymer obtained from cassava starch is also being tested.

2.3. Experimental setup

The objective is to perform a Jar Test that mimics the treatment conditions, obtain the best dosing parameter, and run the machine learning turbidity as the control parameter because of its ease of implementation in the laboratory and low cost.

The rapid mixing is carried out at 70 rpm for one minute. After the time required for the quick mixing, the agitation speed was decreased to 30 rpm for 20 minutes. The coagulant and the biopolymer were added to guarantee the union of the small flocs formed in the coagulation. After this, a sedimentation test was carried out for 30 minutes.

2.4. Application of artificial neural network (ANN)

Linear and nonlinear algorithms have been used to analyze the best prediction method. Within the linear algorithms, linear regression models (LM), generalized linear models (GLM), and penalized linear models (GLMnet) have been tested. For the nonlinear algorithms we have worked with support vector machines (SVM), classification and regression trees (CART), k nearest neighbors (KNN).

The laboratory test data are organized for use and processed in the R Studio program. R Studio is used to validate the data set to confirm the final model's accuracy; a percentage is allocated for training data (80%) and validation data (20%). For a better evaluation of the data set, we will use the 10-fold function for cross-validation, which will allow us to evaluate the linear and non-linear regression algorithms that will work for this case; the algorithms will be evaluated using the MAE, RMSE, and R2 metrics.

The set of algorithms (linear and nonlinear) used details the interactions that must be fulfilled for the ANN process so that the best process will be presented and thus replicate the neural network to predict the estimated data. Finally, laboratory tests will be repeated to validate the predicted results.

3. Results

3.1. Relation of water quality parameters

Turbidity, pH, and suspended solids parameters were measured in the initial tests and related to the dosage of ferric chloride and organic polymer.

The control parameter for treatment efficiency has been turbidity, which is related to the suspended solids in the leachate. This has made it possible to evaluate the removal efficiency according to the dosage applied to have a basis for analysis to test the neural networks.

The initial and final turbidity measurements show non-linear changes, meaning they do not offer a consistent behavior since the initial turbidity values were 1000 NTU, the highest value read by the turbidity meter, and the lowest turbidity value obtained was 2.39 NTU. The removal percentages give an idea of how effective the process was, as follows are some examples of the removal percentages in the leachate experiment (

Table 2). The equipment used for the determination is HACH model 2100Q.

According to the table above, it is evident that the lowest efficiency is achieved at the lowest coagulant dosage (0.5 mL), the best removal percentage (99.01%) is performed with 9 mL, and then the removal begins to decrease, indicating a non-linear relationship, if not with an adequate dosage zone.

3.2. Relationship of the parameters with the dose of coagulant.

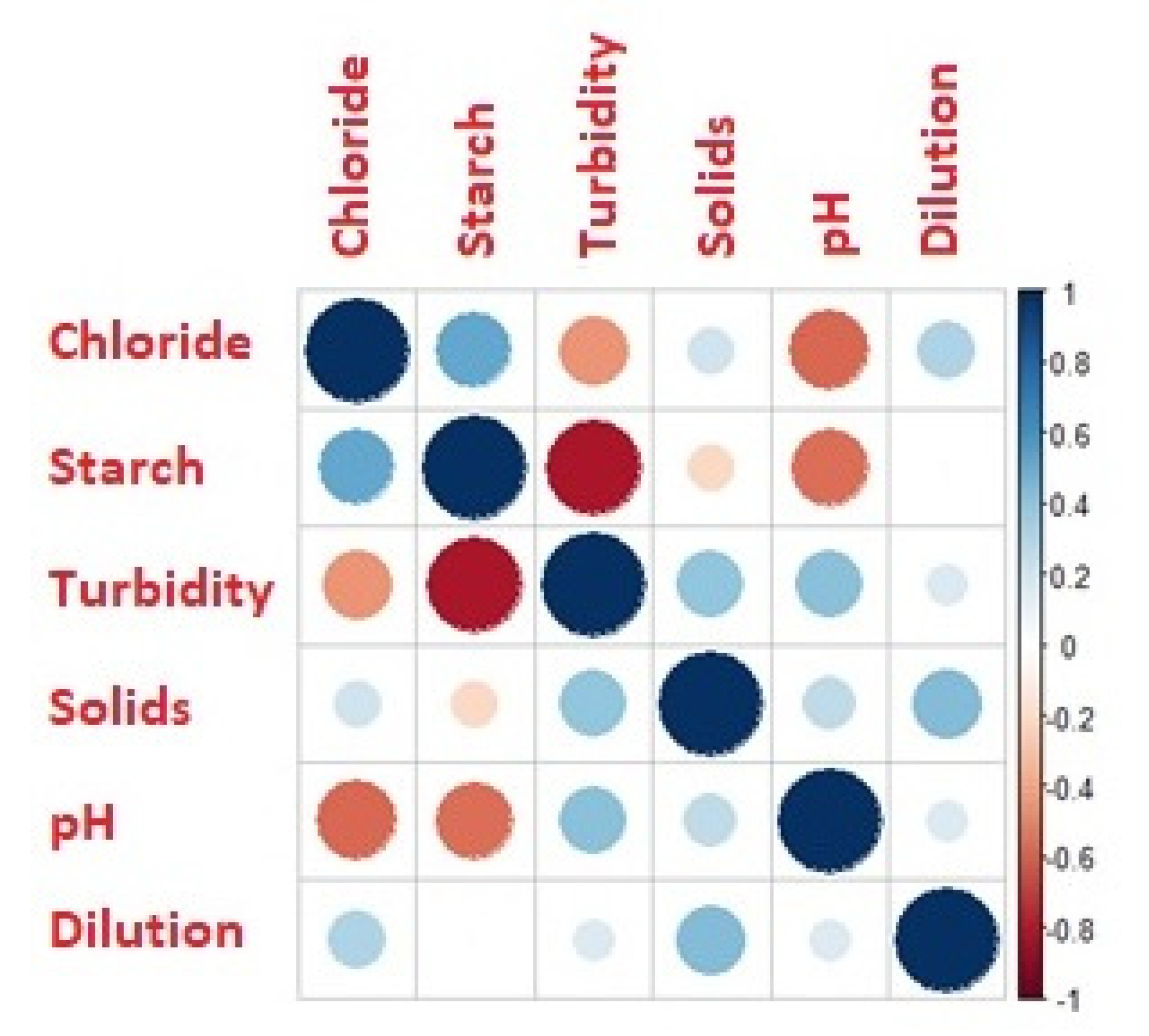

A matrix of correlations between the variables considered for the Jar Test trials is presented below (

Figure 2). This matrix is calculated to use the input or output variables for the ANN subsequently.

One of the highest correlations observed is between turbidity and coagulant dosage, which is why this parameter is used to test the neural network. All the relationships are in numerical form; for a better analysis, they are detailed in the

Table 3.

According to the table above, the parameters that in their intersection have a number closer to a positive or negative one are the ones that have the best relationship between them, both directly proportional (+) and indirectly (-). It can be seen that the best correlation is the turbidity with the dosage of organic polymer (-0.814), which indicates that the higher the dosage of the polymer, the lower the turbidity in the leachate.

The relationship between turbidity and dosage of the coagulant is relatively high compared with the other parameters and, like the previous one, is negative (-0.444), indicating a decrease in turbidity according to the dosage of ferric chloride.

3.3. Results related to observed data, simulated data and ANN algorithms

As mentioned in the methodology section, linear and nonlinear algorithms have been tested to train a neural network to obtain optimal dosing of the coagulants to obtain the best turbidity parameter, optimizing the leachate treatment jar test. Simulations have been run for each proposed network to verify the best fit.

Table 4 presents the metrics used to validate the best-fit algorithm. Mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE) and root mean square error (Rsquared) were tested.

The nonlinear CART and KNN algorithms appear to be in similar results and show slightly bad errors, and these algorithms have the best fit to the data in their R2 measures.

SVM has the lowest MAE and RMSE metrics and a higher Rsquared, indicating that it is the best-fitting algorithm, so it will be used to predict data.

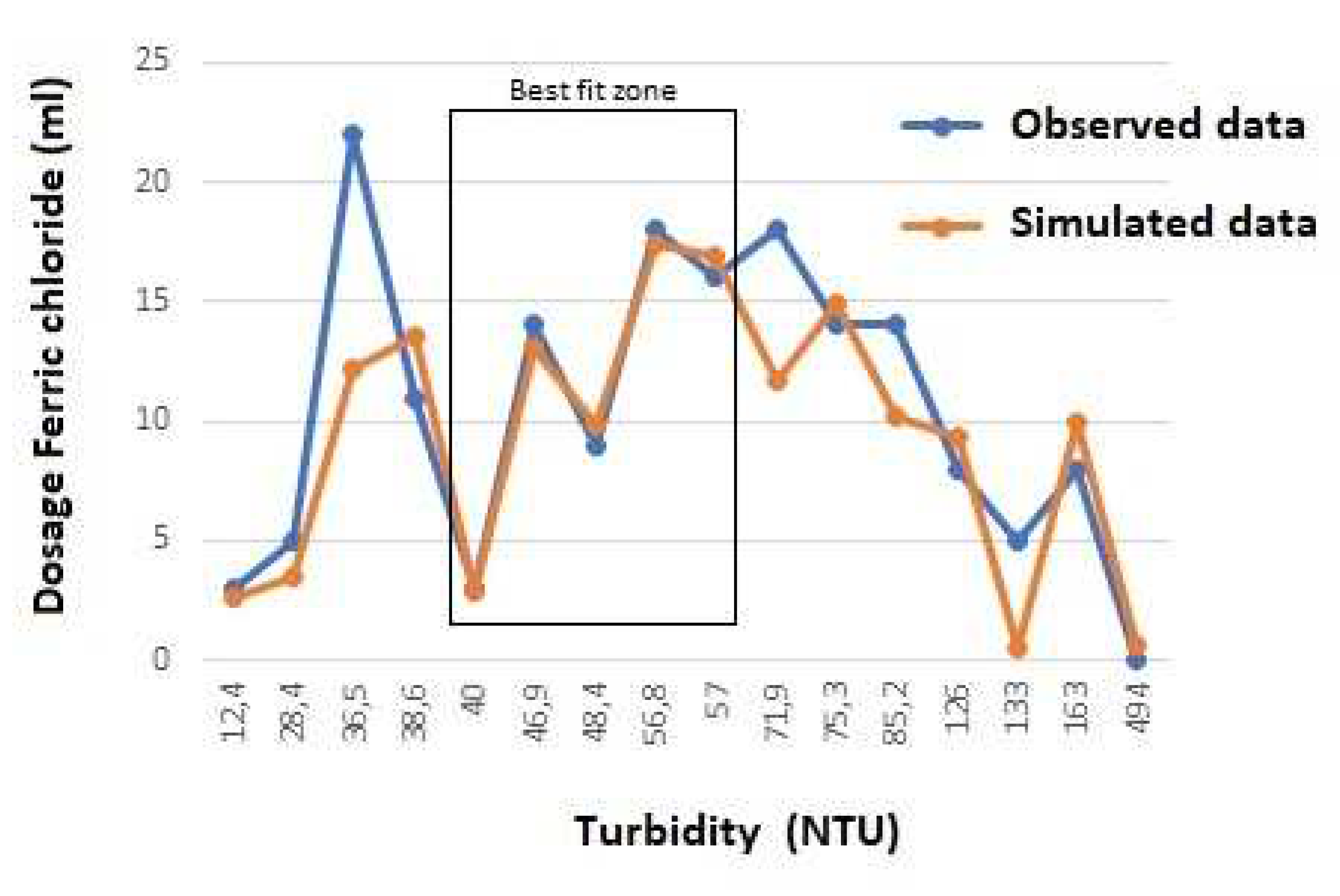

Figure 3 shows the observed and simulated data using the SVM application.

As already indicated by the previous metrics analyzed, the best fit is for the SVM algorithm; it can be seen in the figure above that there is also a specific zone in the dosing of the coagulants where the fit is the best. This gives a fundamental criterion to optimize the test since it allows us to know in which dosages the turbidity (and associated contaminants) will be the lowest.

A new experiment is proposed to validate the use of the artificial neural network, working with dosages that gave the best adjustments, according to

Figure 3. A working range from a dosage of 0.1 mL to 22 mL is presented, classified in three experiments with several proposed trials. The fields of the experiments are 0.5 - 13 mL, 3 - 17 mL, and 8 to 22 mL.

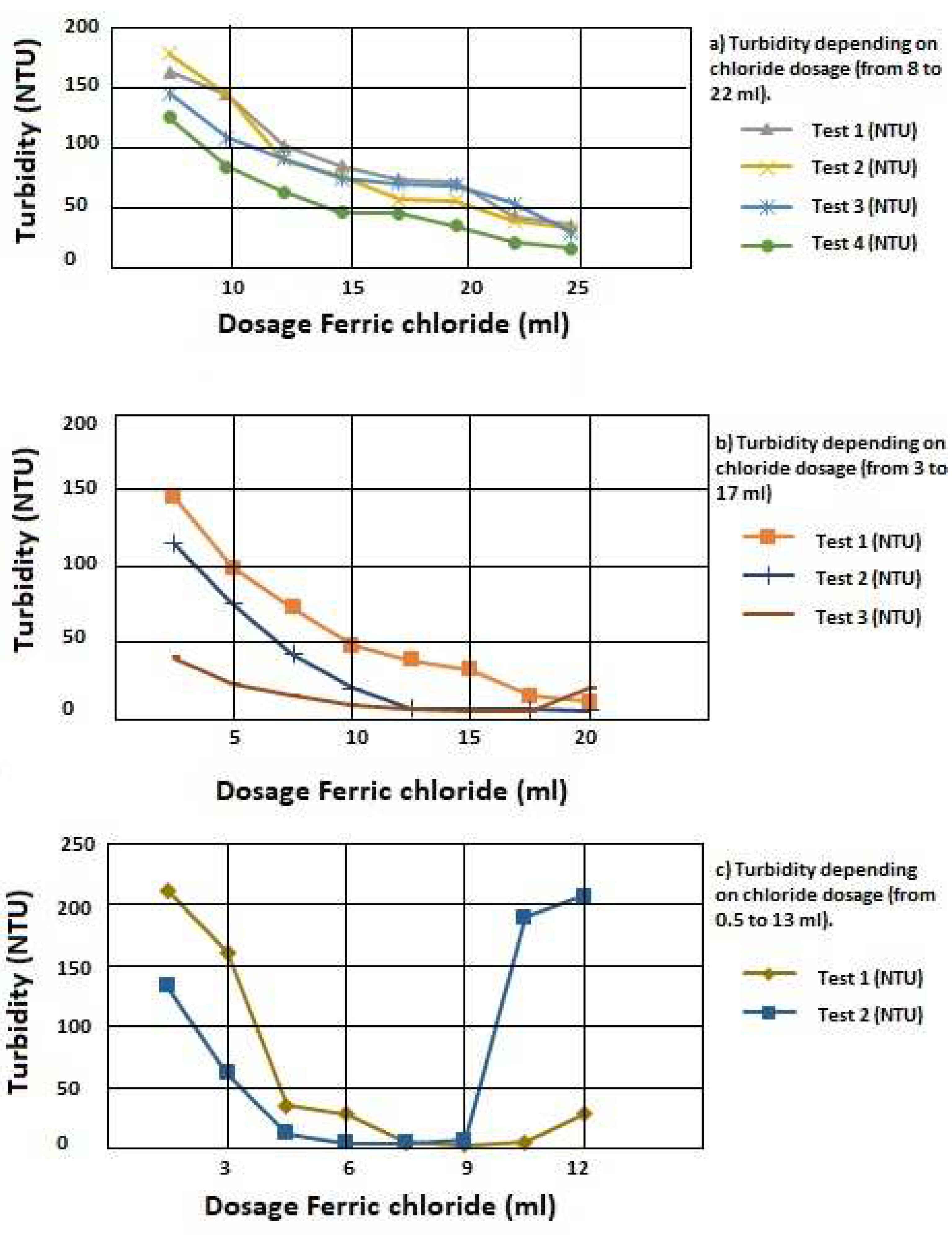

Figure 4 shows the turbidity results for each of the ranges proposed.

In the Jar Test trials carried out about the optimum dose, multiple results were achieved about the chloride dosage and the final turbidity.

Figure 4 shows the results obtained in the experimentation with final turbidity ranging from 5 to 3 NTU. They were being the best experiments and demonstrated that the optimal doses varied in different milliliters for the coagulation to be effective and obtain a good leachate quality.

3.4. Verification of the SVM

To verify that the SVM works and predicts the estimated values, we work with different data between the ranges already obtained in the laboratory tests. These observed data are changed to calculate predicted values, i.e., the chloride dose is estimated as a function of the input variables.

Table 5 shows the input data to the neural network according to the ranges previously obtained. By changing the observed data, we estimate predicted values; this means that the chloride dose is calculated as a function of the input variables.

The dosage of starch, turbidity, solids, pH, and dilution are the input variables taken by the algorithm to estimate the doses of ferric chloride necessary for the treatment; with the input data, the neural network is run again with the algorithm that obtained the best adjustment, which was SVM.

Table 6 shows the estimated chloride data for the different variables.

4. Discussion

Landfill leachate has a characterization depending on the age of the leachate and the parameters that characterize it; this is already an indicator of the type of treatment to which it can be subjected. According to the parameters obtained in the characterization before the experiment, it can be assumed that it is medium-aged leachate [

31]. The parameters of COD, BOD, BOD/CBD ratio, pH, and suspended solids indicate that the leachate may have an age of about 5 to 10 years, according to what Teng [

32] reports.

Although the efficiency of the study is tested by measuring turbidity because it is a quick and inexpensive parameter since several data are needed to validate the algorithm, this parameter indicates a high efficiency in the leachate treatment. In the study conducted by Cheng [

33], an efficiency higher than 58% is achieved in COD removal by applying polyaluminium ferric chloride. In the research developed by Lee [

34], the efficiency in the removal of suspended solids is tested by measuring turbidity, in that investigation, the turbidity value decreased with increasing coagulant dosage. The turbidity value decreased steadily at 5 g/L dosage, and 10 g/L dosage approaches the turbidity value (25 NTU). These results indicate that the optimum dosage required to precipitate the fine soil particles is 10 g/L. In this research, the optimal ferric chloride dose was 0.1 - 22 mL with a concentration of 40 g/L, a relatively higher value. Still, the matter can be justified when working with leachates with high concentrations of solids.

In the study presented by Patel [

30], it tests several coagulants, including ferric chloride for leachate treatment, showing significant decreases of several pollutants such as total organic carbon and COD.

The application of artificial intelligence techniques to optimize leachate treatment processes has been used in recent years. Biglarijoo et al [

35] introduced ferric chloride as a suitable catalyst compared to iron sulfate using the AHP method, applied neural networks together with genetic algorithms to introduce optimal models and conditions. Azadi et al [

36] applied an artificial neural network (ANN) to model the temporal variations of landfill leachate COD in the temporal variations of COD of landfill leachate in the photocatalytic treatment process. Different ANN structures were developed, trained, validated, and tested using data from 150 experiments. The optimal ANN structure was determined based on three performance measures MAPE, NRMSE, and R.

Some authors have applied coagulation-flocculation as a primary treatment and used Machine Learning (ML) algorithms to estimate some efficiencies of the treatment. Beshrati [

16], used Alyssum mucilage and Polyaluminium chloride as coagulants on oily-saline wastewater and applied ANN and Adaptive Neuro Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS), to predict COD removal efficiency based on input parameters (pH, coagulant dose and contact time), obtaining high accuracy in both models for predicting COD removal. Adaobi [

17] used Picralima Nitida Extract (PNE) on landfill leachate and applied Response Surface Methodology (RMS) and ANN using coagulation-flocculation variables like pH, PNE dosage, and time as inputs to estimate the COD reduction process, obtaining superior accuracy on ANN. Also, Igwegbe et al [

17] used Luffa cylindrical as a biocoagulant in the coagulation-flocculation process to treat dye-polluted wastewater and applied RSM and ANN to predict color, total suspended particles, and COD removal based on bio coagulant-dosage, pH and stirring time as input variables in the model, obtaining better results in ANN. The mentioned authors had better results with ANN models, however in our case, SVM gave better results.

Some authors have also predicted turbidity removal efficiencies by applying Machine Learning. Kusuma [

18] tested coagulation-flocculation on synthetic turbid wastewater and predicted turbidity removal efficiency by applying RSM and ANN with input variables like initial turbidity, coagulant dosage, mixing time, and mixing speed, showing that ANN performed better than RSM. Whereas, Adeogun [

20] also used RSM and ANN to predict COD, total dissolved solids, turbidity, and energy consumption based on input variables like pH, time, and current density obtaining better results for ANN. Likewise, Ezemagu [

19], applied RSM and ANN to predict turbidity removal efficiency using dosage time and temperature as input variables. The authors mentioned above showed good efficiency in ANN models to predict turbidity removal efficiency however in our case the best model was SVM.

5. Conclusions

Suspended solids in the leachate were successfully removed using a combination of organic and inorganic coagulants. Through the present work, it was proved that by mixing cassava starch (coadjutant agent) and ferric chloride (coagulating agent), a great potential effect in coagulation-flocculation was achieved, which greatly helps in the treatment of leachates to clarify the liquid in question with the removal of almost 98.31% and thus also reduce its pollutant load.

The effectiveness of the ML will depend a lot on the definition of the input variables that directly influence the prediction of the data, also on the quantity and quality of data that are available for the training and validation set for the respective dose prediction, and on the algorithms to be executed, since these will determine that the results are presented with the lowest error metrics and are more accurately predicted results.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, C.M. and M.Q.; methodology, C.M.; software, D.H.; validation, C.M., D.H.; formal analysis, D.H.; investigation, C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.; writing—review and editing, C.M..All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

Research funds for laboratory development CIITT.

References

- N. Jegan Durai, G. V. T. N. Jegan Durai, G. V. T. Gopalakrishna, V. C. Padmanaban, and N. Selvaraju, “Oxidative removal of stabilized landfill leachate by Fenton’s process: Process modeling, optimization & analysis of degraded products,” RSC Adv., vol. 10, no. 7, pp. 3916–3925, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Simmons, “Pfas Concentrations of Landfill Leachates in Victoria, Australia-Implications for Discharge of Leachate To Sewer,” 17th Int. WASTE Manag. LANDFILL Symp., no. October, 2019.

- S. Mishra, D. S. Mishra, D. Tiwary, and A. Ohri, “Leachate characterisation and evaluation of leachate pollution potential of urban municipal landfill sites,” Int. J. Environ. Waste Manag., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 217–230, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. T. Müller, A. G. T. Müller, A. Giacobbo, E. A. dos Santos Chiaramonte, M. A. S. Rodrigues, A. Meneguzzi, and A. M. Bernardes, “The effect of sanitary landfill leachate aging on the biological treatment and assessment of photoelectrooxidation as a pre-treatment process,” Waste Manag., vol. 36, pp. 177–183, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Wiszniowski, D. J. Wiszniowski, D. Robert, J. Surmacz-Gorska, K. Miksch, and J. V. Weber, “Landfill leachate treatment methods: A review,” Environ. Chem. Lett., vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 51–61, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Kuusik, K. Pachel, A. Kuusik, and E. Loigu, “Landfill runoff water and landfill leachate discharge and treatment,” 9th Int. Conf. Environ. Eng. ICEE 2014, no. 14, 2014. 20 January. [CrossRef]

- M. S. de Oliveira, L. F. M. S. de Oliveira, L. F. da Silva, A. D. Barbosa, L. L. Romualdo, G. Sadoyama, and L. S. Andrade, “Landfill Leachate Treatment by Combining Coagulation and Advanced Electrochemical Oxidation Techniques,” ChemElectroChem, vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 1427–1433, 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. J. F. Chagnon and D. R. F. Harleman, “Chemically Enhanced Primary Treatment of Wastewater,” in Water Encyclopedia, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2005, pp. 659–660.

- J. Q. Jiang, “The role of coagulation in water treatment,” Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng., vol. 8, pp. 36–44, 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. Marañón, L. E. Marañón, L. Castrillón, Y. Fernández-Nava, A. Fernández-Méndez, and A. Fernández-Sánchez, “Coagulation-flocculation as a pretreatment process at a landfill leachate nitrification-denitrification plant,” J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 156, no. 1–3, pp. 538–544, 2008. [CrossRef]

- F. Boumechhour, K. F. Boumechhour, K. Rabah, C. Lamine, and B. M. Said, “Treatment of landfill leachate using Fenton process and coagulation/flocculation,” Water Environ. J., vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 114–119, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Verma and R. Naresh Kumar, “Can coagulation–flocculation be an effective pre-treatment option for landfill leachate and municipal wastewater co-treatment?,” Perspect. Sci., vol. 8, pp. 492–494, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Ahmadi Azqhandi, M. M. H. Ahmadi Azqhandi, M. Ghaedi, F. Yousefi, and M. Jamshidi, “Application of random forest, radial basis function neural networks and central composite design for modeling and/or optimization of the ultrasonic assisted adsorption of brilliant green on ZnS-NP-AC,” J. Colloid Interface Sci., vol. 505, pp. 278–292, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Byliński, A. H. Byliński, A. Sobecki, and J. Gebicki, “The use of artificial neural networks and decision trees to predict the degree of odor nuisance of post-digestion sludge in the sewage treatment plant process,” Sustain., vol. 11, no. 16, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Salem, M. M. Salem, M. EL-Sayed Gabr, M. Mossad, and H. Mahanna, “Random Forest modelling and evaluation of the performance of a full-scale subsurface constructed wetland plant in Egypt,” Ain Shams Eng. J., vol. 13, no. 6, p. 101778, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Fard, D. M. B. Fard, D. Hamidi, K. Yetilmezsoy, J. Alavi, and F. Hosseinpour, “Utilization of Alyssum mucilage as a natural coagulant in oily-saline wastewater treatment,” J. Water Process Eng., vol. 40, no. July, p. 101763, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Igwegbe, O. D. C. A. Igwegbe, O. D. Onukwuli, J. O. Ighalo, and M. C. Menkiti, “Bio-coagulation-flocculation (BCF) of municipal solid waste leachate using Picralima nitida extract: RSM and ANN modelling,” Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem., vol. 4, no. March, p. 100078, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Kusuma et al., “Evaluation of extract of Ipomoea batatas leaves as a green coagulant–flocculant for turbid water treatment: Parametric modelling and optimization using response surface methodology and artificial neural networks,” Environ. Technol. Innov., vol. 24, p. 102005, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. I. Ejimofor, I. G. M. I. Ejimofor, I. G. Ezemagu, and M. C. Menkiti, “RSM and ANN-GA modeling of colloidal particles removal from paint wastewater via coagulation method using modified Aguleri montmorillonite clay,” Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem., vol. 4, no. 20, p. 100164, 2021. 20 September. [CrossRef]

- I. Adeogun, P. B. I. Adeogun, P. B. Bhagawati, and C. B. Shivayogimath, “Pollutants removals and energy consumption in electrochemical cell for pulping processes wastewater treatment: Artificial neural network, response surface methodology and kinetic studies,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 281, no. 20, p. 111897, 2021. 20 August. [CrossRef]

- A. Adesina, A. E. A. Adesina, A. E. Taiwo, O. Akindele, and A. Igbafe, “Process parametric studies for decolouration of dye from local ‘tie and dye’ industrial effluent using Moringa oleifera seed,” South African J. Chem. Eng., vol. 37, no. March, pp. 23–30, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Dai, Y. H. Dai, Y. Tian, B. Dai, S. Skiena, and L. Song, “Syntax-directed variational autoencoder for structured data,” 6th Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. ICLR 2018 - Conf. Track Proc., no. 2016, pp. 1–17, 2018.

- F. J. Montáns, F. F. J. Montáns, F. Chinesta, R. Gómez-Bombarelli, and J. N. Kutz, “Data-driven modeling and learning in science and engineering,” Comptes Rendus - Mec., vol. 347, no. 11, pp. 845–855, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Abunama, F. T. Abunama, F. Othman, M. Ansari, and A. El-Shafie, “Leachate generation rate modeling using artificial intelligence algorithms aided by input optimization method for an MSW landfill,” Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 3368–3381, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Abdallah, M. M. Abdallah, M. Abu Talib, S. Feroz, Q. Nasir, H. Abdalla, and B. Mahfood, “Artificial intelligence applications in solid waste management: A systematic research review,” Waste Manag., vol. 109, pp. 231–246, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Foroughi, A. R. M. Foroughi, A. R. Rahmani, G. Asgari, D. Nematollahi, K. Yetilmezsoy, and M. R. Samarghandi, “Optimization and Modeling of Tetracycline Removal from Wastewater by Three-Dimensional Electrochemical System: Application of Response Surface Methodology and Least Squares Support Vector Machine,” Environ. Model. Assess., vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 327–341, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Dalhat Mu’azu and S. Olusanya Olatunji, “K-nearest neighbor based computational intelligence and RSM predictive models for extraction of Cadmium from contaminated soil,” Ain Shams Eng. J., vol. 14, no. 4, p. 101944, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Cobos Mora and J. L. Solano Peláez, “Sanitary landfill site selection using multi-criteria decision analysis and analytical hierarchy process: A case study in Azuay province, Ecuador,” Waste Manag. Res., vol. 38, no. 10, pp. 1129–1141, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. H. Benson, “Characteristics of Gas and Leachate at an Elevated Temperature Landfill,” in Geotechnical Frontiers 2017, pp. 313–322.

- H. V. Patel, B. H. V. Patel, B. Brazil, H. H. Lou, M. K. Jha, S. Luster-Teasley, and R. Zhao, “Evaluation of the effects of chemically enhanced primary treatment on landfill leachate and sewage co-treatment in publicly owned treatment works,” J. Water Process Eng., vol. 42, no. May, p. 102116, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Miao, G. L. Miao, G. Yang, T. Tao, and Y. Peng, “Recent advances in nitrogen removal from landfill leachate using biological treatments – A review,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 235, no. January, pp. 178–185, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Teng, K. C. Teng, K. Zhou, C. Peng, and W. Chen, “Characterization and treatment of landfill leachate: A review,” Water Res., vol. 203, no. March, p. 117525, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cheng, L. Y. Cheng, L. Xu, and C. Liu, “Red mud-based polyaluminium ferric chloride flocculant: Preparation, characterisation, and flocculation performance,” Environ. Technol. Innov., vol. 27, p. 102509, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. K. Lee et al., “Simultaneous removal of suspended fine soil particles, strontium and cesium from soil washing effluent using inorganic flocculants,” Environ. Technol. Innov., vol. 27, p. 102467, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Biglarijoo, S. A. N. Biglarijoo, S. A. Mirbagheri, M. Bagheri, and M. Ehteshami, “Assessment of effective parameters in landfill leachate treatment and optimization of the process using neural network, genetic algorithm and response surface methodology,” Process Saf. Environ. Prot., vol. 106, pp. 89–103, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Azadi, A. S. Azadi, A. Karimi-Jashni, and S. Javadpour, “Modeling and optimization of photocatalytic treatment of landfill leachate using tungsten-doped TiO2 nano-photocatalysts: Application of artificial neural network and genetic algorithm,” Process Saf. Environ. Prot., vol. 117, pp. 267–277, 2018. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).