Submitted:

29 June 2023

Posted:

30 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Airway secretion of bicarbonate (HCO3-) by CFTR and additional apical transporter

SLC26A9 is expressed in the apical membrane of airways from CFTR-knockout piglets, but not in airways expressing CFTR-F508del

CFTR causes constitutive basal Cl- secretion in the airways

Relationship between CFTR and anoctamins

Crosstalk between CFTR and ANO1

Reduced plasma membrane expression of CFTR in the absence of ANO1

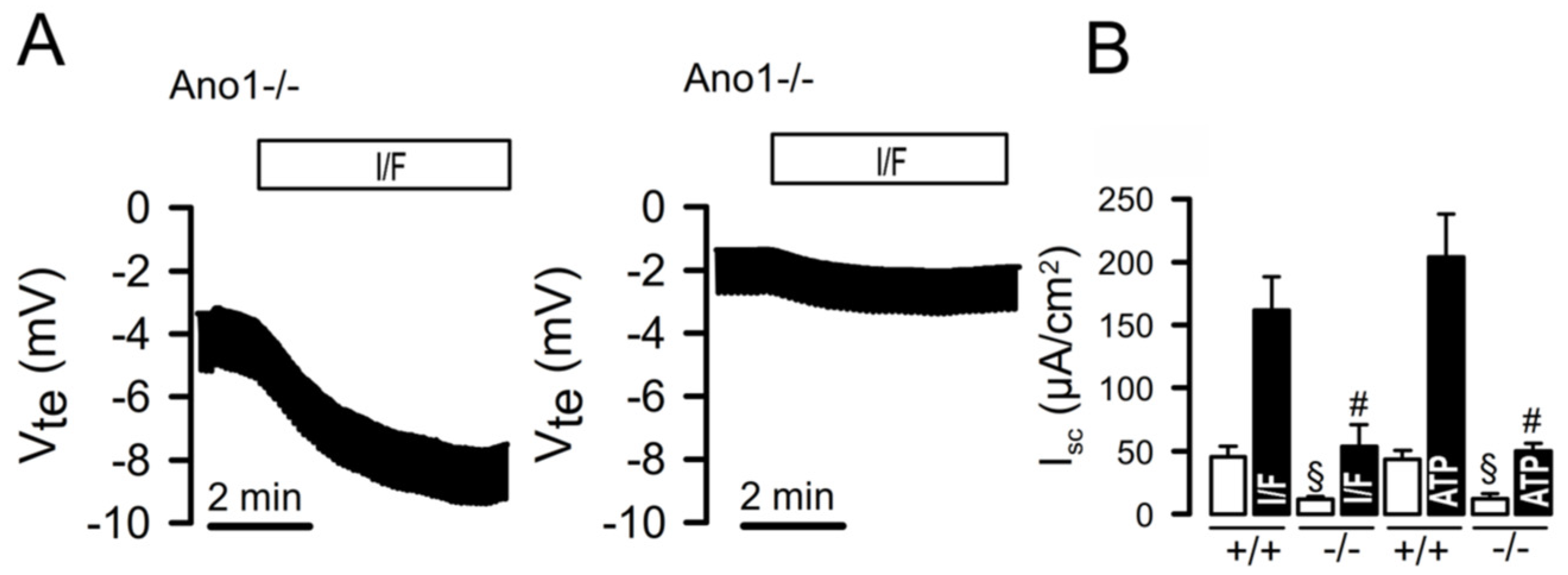

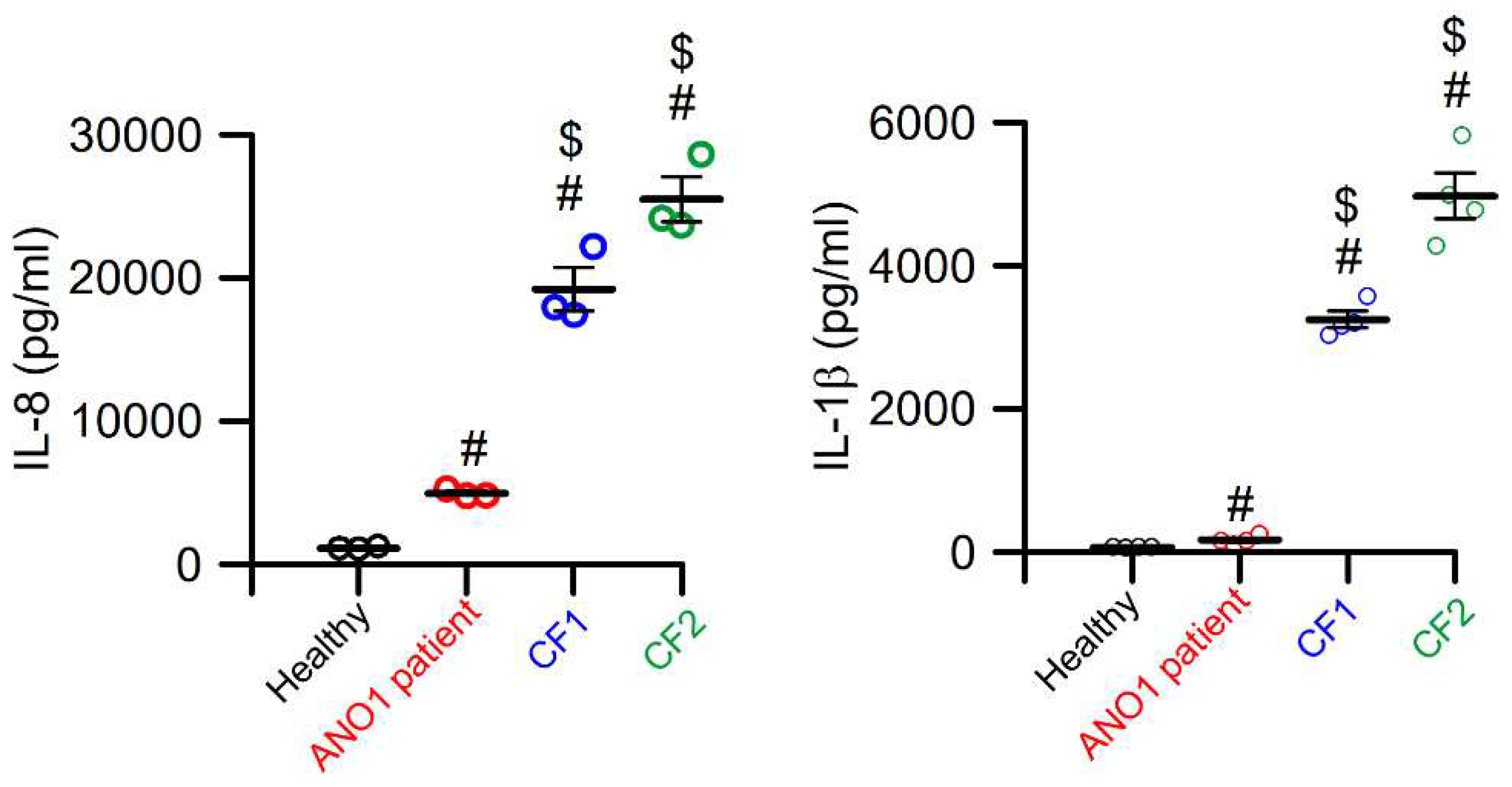

Patients carrying a loss of function mutation in ANO1 lack of CFTR currents

CFTR and ANO1/ANO6 in cell death

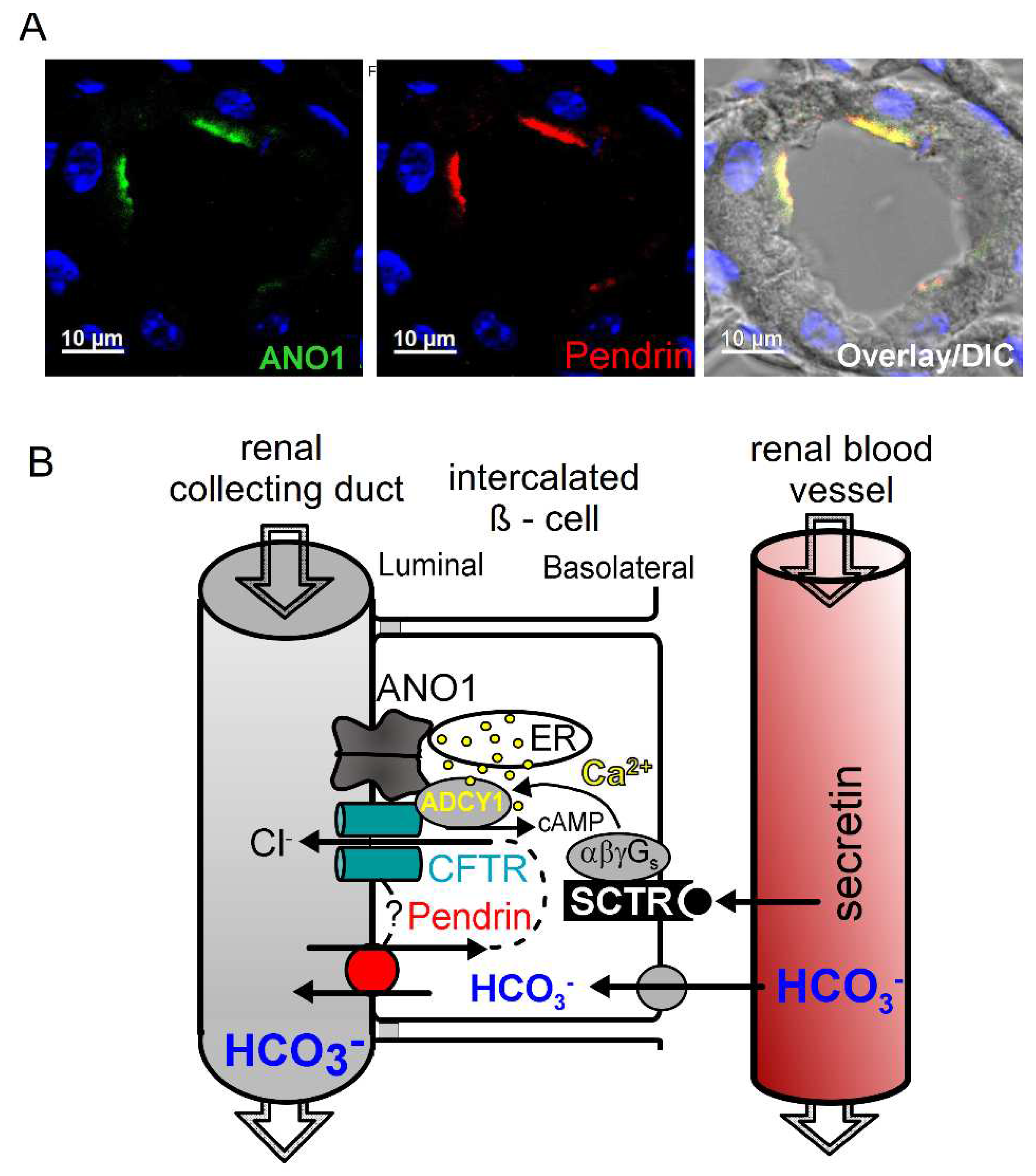

Bicarbonate is secreted in renal collecting ducts, which requires CFTR, Pendrin and possibly ANO1

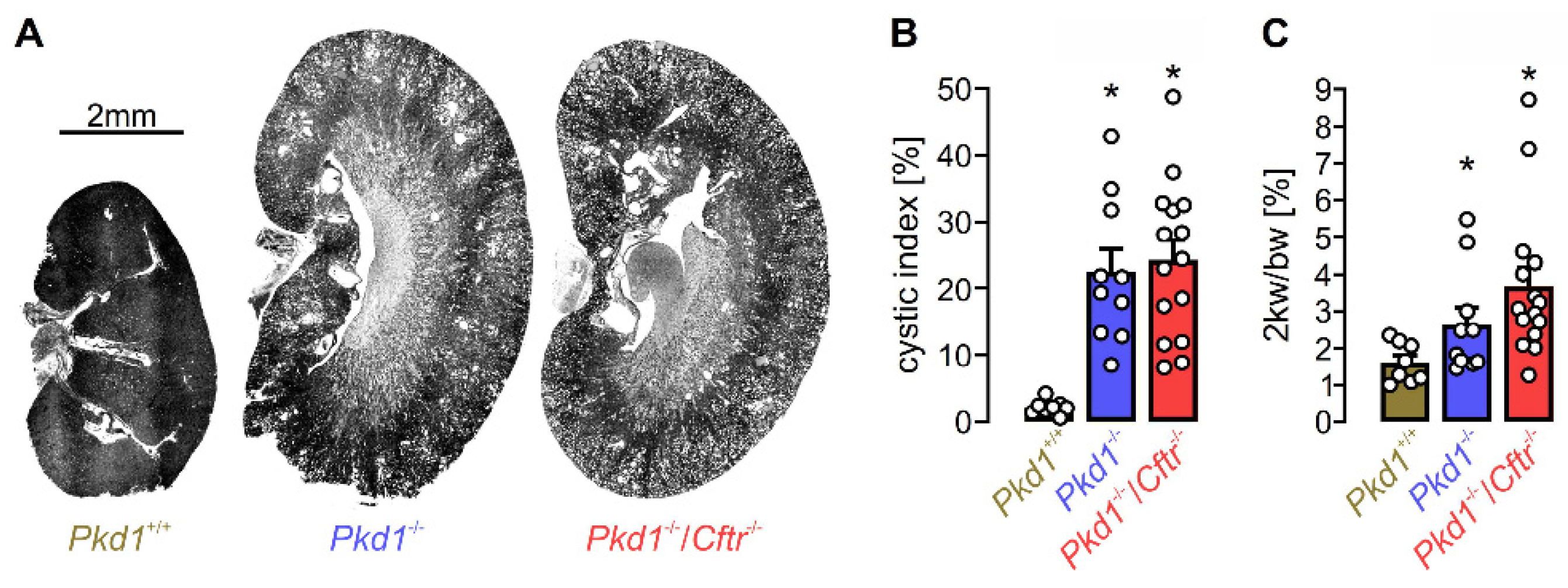

CFTR and ANO1 in polycystic kidney disease: which one counts?

Targeting ANO1 or CFTR in ADPKD?

Inhibitors of ANO1

Conclusion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kunzelmann, K. CFTR: Interacting with everything? News Physiol Sciences 2001, 17, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Venable, J.; LaPointe, P.; Hutt, D.M.; Koulov, A.V.; Coppinger, J.; Gurkan, C.; Kellner, W.; Matteson, J.; Plutner, H. , et al. Hsp90 cochaperone Aha1 downregulation rescues misfolding of CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Cell 2006, 127, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pankow, S.; Bamberger, C.; Calzolari, D.; Martínez-Bartolomé, S.; Lavallée-Adam, M.; Balch, W.E.; Yates, J.R. , 3rd. ∆F508 CFTR interactome remodelling promotes rescue of cystic fibrosis. Nature 2015, 528, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.H.; Snider, J.; Birimberg-Schwartz, L.; Ip, W.; Serralha, J.C.; Botelho, H.M.; Lopes-Pacheco, M.; Pinto, M.C.; Moutaoufik, M.T.; Zilocchi, M. , et al. CFTR interactome mapping using the mammalian membrane two-hybrid high-throughput screening system. Molecular systems biology 2022, 18, e10629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.C.; Botelho, H.M.; Silva, I.A.L.; Railean, V.; Neumann, B.; Pepperkok, R.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K.; Amaral, M.D. Systems Approaches to Unravel Molecular Function: High-content siRNA Screen Identifies TMEM16A Traffic Regulators as Potential Drug Targets for Cystic Fibrosis. J Mol Biol 2022, 167436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Mazein, A.; Farinha, C.M.; Gray, M.A.; Kunzelmann, K.; Ostaszewski, M.; Balaur, I.; Amaral, M.D.; Falcao, A.O. CyFi-MAP: an interactive pathway-based resource for cystic fibrosis. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 22223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzelmann, K.; Mehta, A. CFTR: a hub for kinases and cross-talk of cAMP and Ca. FEBS J 2013, 280, 4417–4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliff, R.; Evans, M.J.; Cuthbert, A.W.; MacVinish, L.J.; Foster, D.; Anderson, J.R.; Colledge, W.H. Production of a severe cystic fibrosis mutation in mice by gene targeting. Nat. Genet 1993, 4, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, M.; Buijs-Offerman, R.M.; Aarbiou, J.; Colledge, W.H.; Sheppard, D.N.; Touqui, L.; Bot, A.; Jorna, H.; De Jonge, H.R.; Scholte, B.J. Mouse models of cystic fibrosis: phenotypic analysis and research applications. J Cyst. Fibros 2011, 10 Suppl 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Stoltz, D.A.; Karp, P.H.; Ernst, S.E.; Pezzulo, A.A.; Moninger, T.O.; Rector, M.V.; Reznikov, L.R.; Launspach, J.L.; Chaloner, K. , et al. Loss of anion transport without increased sodium absorption characterizes newborn porcine cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. Cell 2010, 143, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostedgaard, L.S.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Chen, J.H.; Pezzulo, A.A.; Karp, P.H.; Rokhlina, T.; Ernst, S.E.; Hanfland, R.A.; Reznikov, L.R.; Ludwig, P.S. , et al. The {Delta}F508 Mutation Causes CFTR Misprocessing and Cystic Fibrosis-Like Disease in Pigs. Sci. Transl. Med 2011, 3, 74ra24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, K.A.; Schroder, R.L.; Skaaning-Jensen, B.; Strobaek, D.; Olesen, S.P.; Christophersen, P. Activation of the human intermediate-conductance Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channel by 1-ethyl-2-benzimidazolinone is strongly Ca(2+)-dependent. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1420, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltz, D.A.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Pezzulo, A.A.; Ramachandran, S.; Rogan, M.P.; Davis, G.J.; Hanfland, R.A.; Wohlford-Lenane, C.; Dohrn, C.L.; Bartlett, J.A. , et al. Cystic fibrosis pigs develop lung disease and exhibit defective bacterial eradication at birth. Sci. Transl. Med 2010, 2, 29ra31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezzulo, A.A.; Tang, X.X.; Hoegger, M.J.; Alaiwa, M.H.; Ramachandran, S.; Moninger, T.O.; Karp, P.H.; Wohlford-Lenane, C.L.; Haagsman, H.P.; van Eijk, M. , et al. Reduced airway surface pH impairs bacterial killing in the porcine cystic fibrosis lung. Nature 2012, 487, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoegger, M.J.; Fischer, A.J.; McMenimen, J.D.; Ostedgaard, L.S.; Tucker, A.J.; Awadalla, M.A.; Moninger, T.O.; Michalski, A.S.; Hoffman, E.A.; Zabner, J. , et al. Impaired mucus detachment disrupts mucociliary transport in a piglet model of cystic fibrosis. Science 2014, 345, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, V.S.; Ernst, S.; Tang, X.X.; Karp, P.H.; Parker, C.P.; Ostedgaard, L.S.; Welsh, M.J. Relationships among CFTR expression, HCO3- secretion, and host defense may inform gene- and cell-based cystic fibrosis therapies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2016, 113, 5382–5387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzelmann, K.; Schreiber, R.; Hadorn, H.B. Bicarbonate in cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2017, 16, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, R.; Centeio, R.; Ousingsawat, J.; Schreiber, R.; Janda, M.; Kunzelmann, K. Transport properties in CFTR-/- knockout piglets suggest normal airway surface liquid pH and enhanced amiloride-sensitive Na(+) absorption. Pflugers Arch 2020, 472, 1507–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klymiuk, N.; Mundhenk, L.; Kraehe, K.; Wuensch, A.; Plog, S.; Emrich, D.; Langenmayer, M.C.; Stehr, M.; Holzinger, A.; Kroner, C. , et al. Sequential targeting of CFTR by BAC vectors generates a novel pig model of cystic fibrosis. Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany) 2012, 90, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esther, C.R., Jr.; Muhlebach, M.S.; Ehre, C.; Hill, D.B.; Wolfgang, M.C.; Kesimer, M.; Ramsey, K.A.; Markovetz, M.R.; Garbarine, I.C.; Forest, M.G. , et al. Mucus accumulation in the lungs precedes structural changes and infection in children with cystic fibrosis. Science translational medicine 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, A.; Puvvadi, R.; Borisov, S.M.; Shaw, N.C.; Klimant, I.; Berry, L.J.; Montgomery, S.T.; Nguyen, T.; Kreda, S.M.; Kicic, A. , et al. Airway surface liquid pH is not acidic in children with cystic fibrosis. Nature communications 2017, 8, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ousingsawat, J.; Centeio, R.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. Expression of SLC26A9 in Airways and Its Potential Role in Asthma. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, C.A.; Mitra, S.; Mishra, S.K.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Pilewski, J.M.; Madden, D.R.; Frizzell, R.A. The CFTR trafficking mutation F508del inhibits the constitutive activity of SLC26A9. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2017, 312, L912–l925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Needham, P.G.; Goeckeler-Fried, J.L.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Z.; Wetzel, A.R.; Bertrand, C.A.; Brodsky, J.L. SLC26A9 is selected for endoplasmic reticulum associated degradation (ERAD) via Hsp70-dependent targeting of the soluble STAS domain. Biochem J 2021, 478, 4203–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousingsawat, J.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. Differential contribution of SLC26A9 to Cl(-) conductance in polarized and non-polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol 2011, 227, 2323–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.H.; Plata, C.; Zandi-Nejad, K.; Sindic, A.; Sussman, C.R.; Mercado, A.; Broumand, V.; Raghuram, V.; Mount, D.B.; Romero, M.F. Slc26a9-Anion Exchanger, Channel and Na(+) Transporter. J Membr. Biol 2009, 228, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Henriksnäs, J.; Barone, S.; Witte, D.; Shull, G.E.; Forte, J.G.; Holm, L.; Soleimani, M. SLC26A9 is expressed in gastric surface epithelial cells, mediates Cl-/HCO3- exchange, and is inhibited by NH4+. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2005, 289, C493–C505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demitrack, E.S.; Soleimani, M.; Montrose, M.H. Damage to the gastric epithelium activates cellular bicarbonate secretion via SLC26A9 Cl(-)/HCO(3)(-). American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology 2010, 299, G255–G264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, C.A.; Zhang, R.; Pilewski, J.M.; Frizzell, R.A. SLC26A9 is a constitutively active, CFTR-regulated anion conductance in human bronchial epithelia. J Gen. Physiol 2009, 133, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorwart, M.R.; Shcheynikov, N.; Wang, Y.; Stippec, S.; Muallem, S. SLC26A9 is a Cl(-) channel regulated by the WNK kinases. J Physiol 2007, 584, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loriol, C.; Dulong, S.; Avella, M.; Gabillat, N.; Boulukos, K.; Borgese, F.; Ehrenfeld, J. Characterization of SLC26A9, facilitation of Cl(-) transport by bicarbonate. Cell Physiol Biochem 2008, 22, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, J.D.; Sawicka, M.; Dutzler, R. Cryo-EM structures and functional characterization of murine Slc26a9 reveal mechanism of uncoupled chloride transport. Elife 2019, 8, e46986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, S.; Centeio, R.; Park, J.; Ousingsawat, J.; Jeon, D.K.; Talbi, K.; Schreiber, R.; Ryu, K.; Kahlenberg, K.; Somoza, V. , et al. The SLC26A9 inhibitor S9-A13 provides no evidence for a role of SLC26A9 in airway chloride secretion but suggests a contribution to regulation of ASL pH and gastric proton secretion. Faseb j 2022, 36, e22534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, S.B.; Shcheynikov, N.; Choi, J.Y.; Luo, X.; Ishibashi, K.; Thomas, P.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, M.G.; Naruse, S. , et al. A molecular mechanism for aberrant CFTR-dependent HCO(3)(-) transport in cystic fibrosis. EMBO J 2002 Nov. 1. ;21. (21. ):5662. -72 2002, 21, 5662–5672. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, S.B.; Zeng, W.; Dorwart, M.R.; Luo, X.; Kim, K.H.; Millen, L.; Goto, H.; Naruse, S.; Soyombo, A.; Thomas, P.J. , et al. Gating of CFTR by the STAS domain of SLC26 transporters. Nat. Cell Biol 2004, 6, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakonczay, Z., Jr.; Hegyi, P.; Hasegawa, M.; Inoue, M.; You, J.; Iida, A.; Ignáth, I.; Alton, E.W.; Griesenbach, U.; Ovári, G. , et al. CFTR gene transfer to human cystic fibrosis pancreatic duct cells using a Sendai virus vector. J Cell Physiol 2008, 214, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, B.; Dirami, T.; Bakouh, N.; Rizk-Rabin, M.; Norez, C.; Lhuillier, P.; Lorès, P.; Jollivet, M.; Melin, P.; Zvetkova, I. , et al. The testis anion transporter TAT1 (SLC26A8) physically and functionally interacts with the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator channel: a potential role during sperm capacitation. Hum Mol Genet 2012, 21, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khouri, E.; Toure, A. Functional interaction of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator with members of the SLC26 family of anion transporters (SLC26A8 and SLC26A9): physiological and pathophysiological relevance. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2014, 52, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Huang, J.; Billet, A.; Abu-Arish, A.; Goepp, J.; Matthes, E.; Tewfik, M.A.; Frenkiel, S.; Hanrahan, J.W. Pendrin Mediates Bicarbonate Secretion and Enhances Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Function in Airway Surface Epithelia. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 2019, 60, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzelmann, K.; Centeio, R.; Ousingsawat, J.; Talbi, K.; Seidler, U.; Schreiber, R. SLC26A9 in airways and intestine: secretion or absorption? Channels (Austin) 2023, 17, 2186434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, K.; Okamura, K.; Yamazaki, J. Involvement of apical P2Y2 receptor-regulated CFTR activity in muscarinic stimulation of Cl(-) reabsorption in rat submandibular gland. Am J Physiol Regul. Integr. Comp Physiol 2008, 294, R1729–R1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lytle, C.; Quinton, P.M. Predominant constitutive CFTR conductance in small airways. Respir. Res 2005, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Salinas, D.; Nielson, D.W.; Verkman, A.S. Hyperacidity of secreted fluid from submucosal glands in early cystic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2006, 290, C741–C749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, J.J.; Spahn, S.; Wang, X.; Fullekrug, J.; Bertrand, C.A.; Mall, M.A. Generation and functional characterization of epithelial cells with stable expression of SLC26A9 Cl- channels. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2016, 310, L593–L602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.B.; Choi, J.J.; Wang, X.; Myerburg, M.M.; Frizzell, R.A.; Bertrand, C.A. Separating the contributions of SLC26A9 and CFTR to anion secretion in primary human bronchial epithelia (HBE). Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2021, 321, L1147–L1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Gettings, S.M.; Talbi, K.; Schreiber, R.; Taggart, M.J.; Preller, M.; Kunzelmann, K.; Althaus, M.; Gray, M.A. Pharmacological inhibitors of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator exert off-target effects on epithelial cation channels. Pflugers Arch 2023, 475, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Thomas, D.Y.; Hanrahan, J.W. The anion transporter SLC26A9 localizes to tight junctions and is degraded by the proteasome when co-expressed with F508del-CFTR. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 18269–18284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.C.; Quaresma, M.C.; Silva, I.A.L.; Railean, V.; Ramalho, S.S.; Amaral, M.D. Synergy in Cystic Fibrosis Therapies: Targeting SLC26A9. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 13064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avella, M.; Loriol, C.; Boulukos, K.; Borgese, F.; Ehrenfeld, J. SLC26A9 stimulates CFTR expression and function in human bronchial cell lines. J Cell Physiol 2011, 226, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.L.; Lee, S.Y.; Carlson, D.; Fahrenkrug, S.; O'Grady, S.M. Stable knockdown of CFTR establishes a role for the channel in P2Y receptor-stimulated anion secretion. J Cell Physiol 2006, 206, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappe, V.; Hinkson, D.A.; Howell, L.D.; Evagelidis, A.; Liao, J.; Chang, X.B.; Riordan, J.R.; Hanrahan, J.W. Stimulatory and inhibitory protein kinase C consensus sequences regulate the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2004, 101, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Mathews, C.J.; Hanrahan, J.W. Phosphorylation by protein kinase C is required for acute activation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by protein kinase A. J. Biol. Chem 1997, 272, 4978–4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winpenny, J.P.; McAlroy, H.L.; Gray, M.A.; Argent, B.E. Protein kinase C regulates the magnitude and stability of CFTR currents in pancreatic duct cells. Am. J. Physiol 1995, 268, C823–C828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.P.; Welsh, M.J. Calcium and cAMP activate different chloride channels in the apical membrane of normal and cystic fibrosis epithelia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 6003–6007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunzelmann, K.; Kubitz, R.; Grolik, M.; Warth, R.; Greger, R. Small conductance Cl- channels in HT29 cells: activation by Ca2+, hypotonic cell swelling and 8-Br-cGMP. Pflügers Arch 1992, 421, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedetto, R.; Ousingsawat, J.; Wanitchakool, P.; Zhang, Y.; Holtzman, M.J.; Amaral, M.; Rock, J.R.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. Epithelial Chloride Transport by CFTR Requires TMEM16A. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 12397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerias, J.; Pinto, M.; Benedetto, R.; Schreiber, R.; Amaral, M.; Aureli, M.; Kunzelmann, K. Compartmentalized crosstalk of CFTR and TMEM16A (ANO1) through EPAC1 and ADCY1. Cell Signal 2018, 44, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzelmann, K.; Mall, M.; Briel, M.; Hipper, A.; Nitschke, R.; Ricken, S.; Greger, R. The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator attenuates the endogenous Ca2+ activated Cl- conductance in Xenopus ooyctes. Pflügers Arch 1997, 434, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Vankeerberghen, A.; Cuppens, H.; Eggermont, J.; Cassiman, J.J.; Droogmans, G.; Nilius, B. Interaction between calcium-activated chloride channels and the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Pflugers Arch 1999, 438, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Vankeerberghen, A.; Cuppens, H.; Cassiman, J.J.; Droogmans, G.; Nilius, B. The C-terminal part of the R-domain, but not the PDZ binding motif, of CFTR is involved in interaction with Ca2+ -activated Cl- channels. Pflügers Arch 2001, 442, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Cornejo, P.; Arreola, J. Regulation of Ca(2+)-activated chloride channels by cAMP and CFTR in parotid acinar cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2004, 316, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousingsawat, J.; Kongsuphol, P.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. CFTR and TMEM16A are Separate but Functionally Related Cl Channels. Cell Physiol Biochem 2011, 28, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunzelmann, K.; Tian, Y.; Martins, J.R.; Faria, D.; Kongsuphol, P.; Ousingsawat, J.; Wolf, L.; Schreiber, R. Cells in focus: Airway epithelial cells-Functional links between CFTR and anoctamin dependent Cl(-) secretion. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 2012, 44, 1897–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namkung, W.; Finkbeiner, W.E.; Verkman, A.S. CFTR-Adenylyl Cyclase I Association Is Responsible for UTP Activation of CFTR in Well-Differentiated Primary Human Bronchial Cell Cultures. Mol. Biol. Cell 2010, 21, 2639–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billet, A.; Hanrahan, J.W. The secret life of CFTR as a calcium-activated chloride channel. J Physiol 2013, 591, 5273–5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, S.C.; Jia, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, H. Molecular basis of PIP2-dependent regulation of the Ca(2+)-activated chloride channel TMEM16A. Nature communications 2019, 10, 3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.; Jung, S.R.; Kim, K.W.; Yeon, J.H.; Park, C.G.; Nam, J.H.; Hille, B.; Suh, B.C. Allosteric modulation of alternatively spliced Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-) channels TMEM16A by PI(4,5)P(2) and CaMKII. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, R.; Ousingsawat, J.; Wanitchakool, P.; Sirianant, L.; Benedetto, R.; Reiss, K.; Kunzelmann, K. Regulation of TMEM16A/ANO1 and TMEM16F/ANO6 ion currents and phospholipid scrambling by Ca2+ and plasma membrane lipid. J Physiology (London) 2018, 596, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbi, K.; Ousingsawat, J.; Centeio, R.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. Calmodulin-Dependent Regulation of Overexpressed but Not Endogenous TMEM16A Expressed in Airway Epithelial Cells. Membranes 2021, 11, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mall, M.; Gonska, T.; Thomas, J.; Schreiber, R.; Seydewitz, H.H.; Kuehr, J.; Brandis, M.; Kunzelmann, K. Modulation of Ca2+ activated Cl- secretion by basolateral K+ channels in human normal and cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. Pediatric Research 2003, 53, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mall, M.; Bleich, M.; Greger, R.; Schürlein, M.; Kühr, J.; Seydewitz, H.H.; Brandis, M.; Kunzelmann, K. Cholinergic ion secretion in human colon requires co-activation by cAMP. Am J Physiol 1998, 275, G1274–G1281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Faria, D.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. CFTR is activated through stimulation of purinergic P2Y2 receptors. Pflügers Arch 2009, 457, 1373–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, R.; Faria, D.; Skryabin, B.V.; Rock, J.R.; Kunzelmann, K. Anoctamins support calcium-dependent chloride secretion by facilitating calcium signaling in adult mouse intestine. Pflügers Arch 2015, 467, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tembo, M.; Wozniak, K.L.; Bainbridge, R.E.; Carlson, A.E. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) and Ca(2+) are both required to open the Cl(-) channel TMEM16A. J Biol Chem 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danahay, H.L.; Lilley, S.; Fox, R.; Charlton, H.; Sabater, J.; Button, B.; McCarthy, C.; Collingwood, S.P.; Gosling, M. TMEM16A Potentiation: A Novel Therapeutic Approach for the Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeio, R.; Ousingsawat, J.; Cabrita, I.; Schreiber, R.; Talbi, K.; Benedetto, R.; Doušová, T.; Verbeken, E.K.; De Boeck, K.; Cohen, I. , et al. Mucus Release and Airway Constriction by TMEM16A May Worsen Pathology in Inflammatory Lung Disease. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, R.; Cabrita, I.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. TMEM16A is indispensable for basal mucus secretion in airways and intestine. FASEB J 2019, 33, 4502–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzelmann, K.; Ousingsawat, J.; Cabrita, I.; Doušová, T.; Bähr, A.; Janda, M.; Schreiber, R.; Benedetto, R. TMEM16A in Cystic Fibrosis: Activating or Inhibiting? Frontiers in pharmacology 2019, 29, 10:13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Liu, M.; Xiao, Q. The diverse roles of TMEM16A Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-) channels in inflammation. Journal of advanced research 2021, 33, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Linley, J.E.; Du, X.; Zhang, X.; Ooi, L.; Zhang, H.; Gamper, N. The acute nociceptive signals induced by bradykinin in rat sensory neurons are mediated by inhibition of M-type K+ channels and activation of Ca2+-activated Cl- channels. J. Clin. Invest 2010, 120, 1240–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Cho, H.; Jung, J.; Yang, Y.D.; Yang, D.J.; Oh, U. Anoctamin 1 contributes to inflammatory and nerve-injury induced hypersensitivity. Mol. Pain 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miner, K.; Labitzke, K.; Liu, B.; Elliot, R.; Wang, P.; Henckels, K.; Gaida, K.; Elliot, R.; Chen, J.J.; Liu, L. , et al. Drug Repurposing: The Anthelmintics Niclosamide and Nitazoxanide Are Potent TMEM16A Antagonists That Fully Bronchodilate Airways. Frontiers in pharmacology 2019, 14, 10:51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffin, M.; Voland, M.; Marie, S.; Bonora, M.; Blanchard, E.; Blouquit-Laye, S.; Naline, E.; Puyo, P.; Le Rouzic, P.; Guillot, L. , et al. Anoctamin 1 Dysregulation Alters Bronchial Epithelial Repair in Cystic Fibrosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1832, 2340–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, M.J.; Amaral, M.D.; Zaccolo, M.; Farinha, C.M. EPAC1 activation by cAMP stabilizes CFTR at the membrane by promoting its interaction with NHERF1. J Cell Sci 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Halm, S.T.; Zhang, J.; Halm, D.R. Activation of the basolateral membrane Cl conductance essential for electrogenic K secretion suppresses electrogenic Cl secretion. Exp. Physiol 2011, 96, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, I.; Benedetto, R.; Fonseca, A.; Wanitchakool, P.; Sirianant, L.; Skryabin, B.V.; Schenk, L.K.; Pavenstadt, H.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. Differential effects of anoctamins on intracellular calcium signals. Faseb j 2017, 31, 2123–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzelmann, K.; Cabrita, I.; Wanitchakool, P.; Ousingsawat, J.; Sirianant, L.; Benedetto, R.; Schreiber, R. Modulating Ca2+signals: a common theme for TMEM16, Ist2, and TMC. Pflügers Arch 2016, 468, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Shah, S.; Du, X.; Zhang, H.; Gamper, N. Activation of Ca2+-activated Cl- channel ANO1 by localized Ca2+ signals. J Physiol 2016, 594, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerias, J.R.; Pinto, M.C.; Botelho, H.M.; Awatade, N.T.; Quaresma, M.C.; Silva, I.A.L.; Wanitchakool, P.; Schreiber, R.; Pepperkok, R.; Kunzelmann, K. , et al. A novel microscopy-based assay identifies extended synaptotagmin-1 (ESYT1) as a positive regulator of anoctamin 1 traffic. Biochim Biophys Acta 2018, 1865, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, R.; Ousingsawat, J.; Cabrita, I.; Pinto, M.; Lerias, J.; Wanitchakool, P.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. Plasma membrane localized TMEM16 Proteins are Indispensable for expression of CFTR. J Mol Med 2019, 97, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, I.; Benedetto, R.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. Niclosamide repurposed for the treatment of inflammatory airway disease. JCI insight 2019, 8, 128414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yimnual, C.; Satitsri, S.; Ningsih, B.N.S.; Rukachaisirikul, V.; Muanprasat, C. A fungus-derived purpactin A as an inhibitor of TMEM16A chloride channels and mucin secretion in airway epithelial cells. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie 2021, 139, 111583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeio, R.; Ousingsawat, J.; schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. CLCA1 Regulates Airway Mucus Production and Ion Secretion Through TMEM16A International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 5133. 22. [CrossRef]

- Chappe, V.; Hinkson, D.A.; Zhu, T.; Chang, X.B.; Riordan, J.R.; Hanrahan, J.W. Phosphorylation of protein kinase C sites in NBD1 and the R domain control CFTR channel activation by PKA. J Physiol 2003, 548, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, R.; Cabrita, I.; Kunzelmann, K. Paneth cell secretion in vivo requires expression of Tmem16a and Tmem16f. Gastro Hep Advances 2022, 1, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Ousingsawat, J.; Cabrita, I.; Bettels, R.E.; Große-Onnebrink, J.; Schmalstieg, C.; Biskup, S.; Reunert, J.; Rust, S.; Schreiber, R. , et al. TMEM16A deficiency: a potentially fatal neonatal disease resulting from impaired chloride currents. J Med Genet 2020, 58, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagel, S.D.; Chmiel, J.F.; Konstan, M.W. Sputum biomarkers of inflammation in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 2007, 4, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzelmann, K.; Ousingsawat, J.; Benedetto, R.; Cabrita, I.; Schreiber, R. Contribution of Anoctamins to Cell Survival and Cell Death. Cancers 2019, 19, E382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantin, A.M.; North, S.L.; Hubbard, R.C.; Crystal, R.G. Normal alveolar epithelial lining fluid contains high levels of glutathione. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985) 1987, 63, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; MacNee, W. Oxidative stress and regulation of glutathione in lung inflammation. The European respiratory journal 2000, 16, 534–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, I.; Ramjeesingh, M.; Li, C.; Kidd, J.F.; Wang, Y.; Leslie, E.M.; Cole, S.P.; Bear, C.E. CFTR directly mediates nucleotide-regulated glutathione flux. EMBO J 2003, 22, 1981–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Kim, K.J.; Yankaskas, J.R.; Forman, H.J. Abnormal glutathione transport in cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. Am J Physiol 1999, 277, L113–L118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoes, F.; Ousingsawat, J.; Wanitchakool, P.; Fonseca, A.; Cabrita, I.; Benedetto, R.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. CFTR supports cell death through ROS-dependent activation of TMEM16F (anoctamin 6). Pflugers Arch 2018, 470, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousingsawat, J.; Wanitchakool, P.; Kmit, A.; Romao, A.M.; Jantarajit, W.; Schreiber, S.; Kunzelmann, K. Anoctamin 6 mediates effects essential for innate immunity downstream of P2X7-receptors in macrophages. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousingsawat, J.; Schreiber, R.; Gulbins, E.; Kamler, M.; Kunzelmann, K. P. aeruginosa Induced Lipid Peroxidation Causes Ferroptotic Cell Death in Airways. Cell Physiol Biochem 2021, 55, 590–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousingsawat, J.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. TMEM16F/Anoctamin 6 in Ferroptotic Cell Death. Cancers 2019, 11, pii–E625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegyi, P.; Seidler, U.; Kunzelmann, K. CFTR-beyond the airways: Recent findings on the role of the CFTR channel in the pancreas, the intestine and the kidneys. Journal of cystic fibrosis : official journal of the European Cystic Fibrosis Society 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bretscher, D.; Schneider, A.; Hagmann, R.; Hadorn, B.; Howald, B.; Lüthy, C.; Oetliker, O. Response of renal handling of sodium and bicarbonate to secretin in normals and in patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatric Research 1974, 8, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windstetter, D.; Schaefer, F.; Scharer, K.; Reiter, K.; Eife, R.; Harms, H.K.; Bertele-Harms, R.; Fiedler, F.; Tsui, L.C.; Reitmeir, P. , et al. Renal function and renotropic effects of secretin in cystic fibrosis. Eur. J Med. Res 1997, 2, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berg, P.; Svendsen, S.L.; Sorensen, M.V.; Larsen, C.K.; Andersen, J.F.; Jensen-Fangel, S.; Jeppesen, M.; Schreiber, R.; Cabrita, I.; Kunzelmann, K. , et al. Impaired Renal HCO(3) (-) Excretion in Cystic Fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020, 31, 1711–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, P.; Svendsen, S.L.; Sorensen, M.V.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K.; Leipziger, J. The molecular mechanism of CFTR- and secretin-dependent renal bicarbonate excretion. J Physiol. 2021, 599, 3003–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, V.E.; Harris, P.C.; Pirson, Y. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet 2007, 369, 1287–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senum, S.R.; Li, Y.S.M.; Benson, K.A.; Joli, G.; Olinger, E.; Lavu, S.; Madsen, C.D.; Gregory, A.V.; Neatu, R.; Kline, T.L. , et al. Monoallelic IFT140 pathogenic variants are an important cause of the autosomal dominant polycystic kidney-spectrum phenotype. Am J Hum Genet 2022, 109, 136–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raphael, K.L.; Strait, K.A.; Stricklett, P.K.; Miller, R.L.; Nelson, R.D.; Piontek, K.B.; Germino, G.G.; Kohan, D.E. Inactivation of Pkd1 in principal cells causes a more severe cystic kidney disease than in intercalated cells. Kidney Int 2009, 75, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, B.; Teschemacher, B.; Schley, G.; Schillers, H.; Eckardt, K.U. Formation of cysts by principal-like MDCK cells depends on the synergy of cAMP- and ATP-mediated fluid secretion. J Mol. Med 2011, 89, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grantham, J.J.; Mulamalla, S.; Swenson-Fields, K.I. Why kidneys fail in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nature reviews. Nephrology 2011, 7, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terryn, S.; Ho, A.; Beauwens, R.; Devuyst, O. Fluid transport and cystogenesis in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidow, C.J.; Maser, R.L.; Rome, L.A.; Calvet, J.P.; Grantham, J.J. The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator mediates transepithelial fluid secretion by human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease epithelium in vitro. Kidney Int 1996, 50, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magenheimer, B.S.; St John, P.L.; Isom, K.S.; Abrahamson, D.R.; De Lisle, R.C.; Wallace, D.P.; Maser, R.L.; Grantham, J.J.; Calvet, J.P. Early embryonic renal tubules of wild-type and polycystic kidney disease kidneys respond to cAMP stimulation with cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator/Na(+),K(+),2Cl(-) Co-transporter-dependent cystic dilation. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006, 17, 3424–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Sonawane, N.D.; Zhao, D.; Somlo, S.; Verkman, A.S. Small-Molecule CFTR Inhibitors Slow Cyst Growth in Polycystic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc. Nephrol 2008, 19, 1300–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, I.; Kraus, A.; Scholz, J.K.; Skoczynski, K.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K.; Buchholz, B. Cyst growth in ADPKD is prevented by pharmacological and genetic inhibition of TMEM16A in vivo. Nature communications 2020, 11, 4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, I.; Buchholz, B.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. TMEM16A drives renal cyst growth by augmenting Ca(2+) signaling in M1 cells. Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany) 2020, 98, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrita, I.; Talbi, K.; Kunzelmann, K.; Schreiber, R. Loss of PKD1 and PKD2 share common effects on intracellular Ca2+ signaling. Cell Calcium 2021, 97, 102413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabow, P.A.; Johnson, A.M.; Kaehny, W.D.; Kimberling, W.J.; Lezotte, D.C.; Duley, I.T.; Jones, R.H. Factors affecting the progression of renal disease in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int 1992, 41, 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.H. End-stage renal failure appears earlier in men than in women with polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 1994, 24, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbi, K.; Cabrita, I.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K. Gender-Dependent Phenotype in Polycystic Kidney Disease Is Determined by Differential Intracellular Ca2+ Signals. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, K.; Sweeney, W.E., Jr.; Macrae, D.K.; Cotton, C.U.; Avner, E.D. Role of CFTR in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001, 12, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, V.; Rudym, D.; Chandra, P.; Miskulin, D.; Perrone, R.; Sarnak, M. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance in polycystic kidney disease. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN 2011, 6, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, R.; Buchholz, B.; Kraus, A.; Schley, G.; Scholz, J.; Ousingsawat, J.; Kunzelmann, K. Lipid peroxidation drives renal cyst growth in vitro through activation of TMEM16A. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019, 30, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaoka, K.; Devuyst, O.; Schwiebert, E.M.; Wilson, P.D.; Guggino, W.B. A role for CFTR in human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Physiol 1996, 270, C389–C399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Sullivan, D.A.; Torres, V.E.; Gabow, P.A.; Thibodeau, S.N.; King, B.F.; Bergstralh, E.J. Cystic fibrosis and the phenotypic expression of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 1998, 32, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Glockner, J.F.; Rossetti, S.; Babovich-Vuksanovic, D.; Harris, P.C.; Torres, V.E. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease coexisting with cystic fibrosis. J Nephrol 2006, 19, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Persu, A.; Devuyst, O.; Lannoy, N.; Materne, R.; Brosnahan, G.; Gabow, P.A.; Pirson, Y.; Verellen-Dumoulin, C. CF gene and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator expression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000, 11, 2285–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brill, S.R.; Ross, K.E.; Davidow, C.J.; Ye, M.; Grantham, J.J.; Caplan, M.J. Immunolocalization of ion transport proteins in human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1996, 93, 10206–10211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, B.; Faria, D.; Schley, G.; Schreiber, R.; Eckardt, K.U.; Kunzelmann, K. Anoctamin 1 induces calcium-activated chloride secretion and tissue proliferation in polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2014, 85, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, B.; Schley, G.; Faria, D.; Kroening, S.; Willam, C.; Schreiber, R.; Klanke, B.; Burzlaff, N.; Kunzelmann, K.; Eckardt, K.U. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1a Causes Renal Cyst Expansion through Calcium-Activated Chloride Secretion. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014, 25, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwiebert, E.M.; Wallace, D.P.; Braunstein, G.M.; King, S.R.; Peti-Peterdi, J.; Hanaoka, K.; Guggino, W.B.; Guay-Woodford, L.M.; Bell, P.D.; Sullivan, L.P. , et al. Autocrine extracellular purinergic signaling in epithelial cells derived from polycystic kidneys. Am. J Physiol Renal Physiol 2002, 282, F763–F775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, A.; Grampp, S.; Goppelt-Struebe, M.; Schreiber, R.; Kunzelmann, K.; Peters, D.J.; Leipziger, J.; Schley, G.; Schodel, J.; Eckardt, K.U. , et al. P2Y2R is a direct target of HIF-1alpha and mediates secretion-dependent cyst growth of renal cyst-forming epithelial cells. Purinergic signalling 2016, 12, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbi, K.; Cabrita, I.; Kraus, A.; Hofmann, S.; Skoczynski, K.; Kunzelmann, K.; Buchholz, B.; Schreiber, R. The chloride channel CFTR is not required for cyst growth in an ADPKD mouse model. Faseb j 2021, 35, e21897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilbault, C.; Saeed, Z.; Downey, G.P.; Radzioch, D. Cystic fibrosis mouse models. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 2007, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanda, M.K.; Cha, B.; Cebotaru, C.V.; Cebotaru, L. Pharmacological reversal of renal cysts from secretion to absorption suggests a potential therapeutic strategy for managing autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 17090–17104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanda, M.K.; Cebotaru, L. VX-809 mitigates disease in a mouse model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease bearing the R3277C human mutation. Faseb j 2021, 35, e21987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Koningsbruggen-Rietschel, S.; Conrath, K.; Fischer, R.; Sutharsan, S.; Kempa, A.; Gleiber, W.; Schwarz, C.; Hector, A.; Van Osselaer, N.; Pano, A. , et al. GLPG2737 in lumacaftor/ivacaftor-treated CF subjects homozygous for the F508del mutation: A randomized phase 2A trial (PELICAN). Journal of cystic fibrosis : official journal of the European Cystic Fibrosis Society 2020, 19, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Mook, R.A., Jr.; Premont, R.T.; Wang, J. Niclosamide: Beyond an antihelminthic drug. Cell Signal 2018, 41, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.H.; Graham, G.G.; Williams, K.M.; Day, R.O. A benefit-risk assessment of benzbromarone in the treatment of gout. Was its withdrawal from the market in the best interest of patients? Drug safety 2008, 31, 643–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).