Submitted:

26 June 2023

Posted:

28 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Study area

2.2. Sample collection, preservation, and analysis

2.3. Ion analysis

2.4. Coliform analysis

2.5. Risk assessment of groundwater

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristic of the Study Area

3.2. Physical parameters of the Groundwater

3.3. Ion chemistry of the groundwater

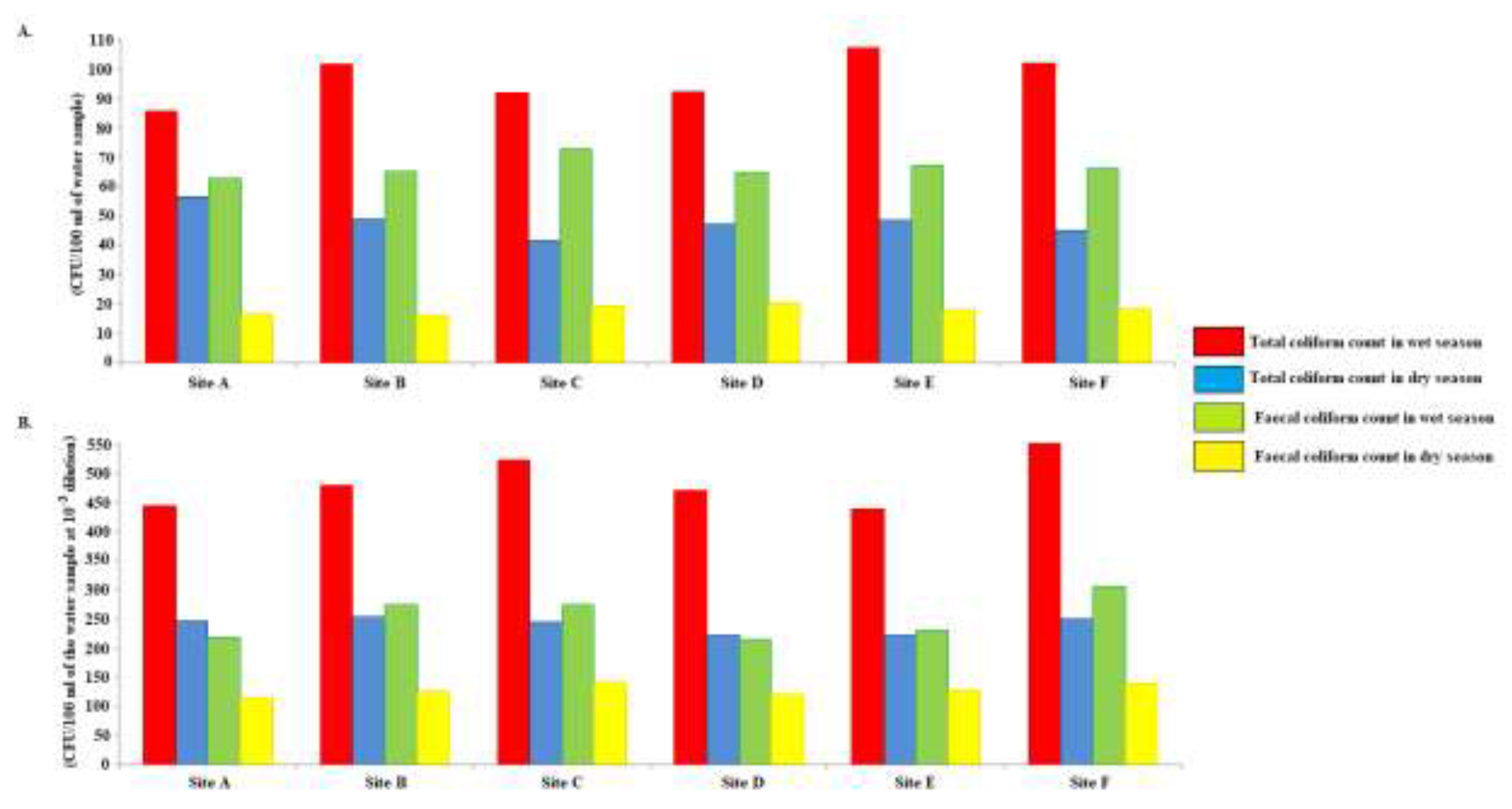

3.4. Microbiological Quality of Groundwater

3.5. Microbiological Quality of Surface water

3.6. Seasonal variation in microbial quality of groundwater and surface water

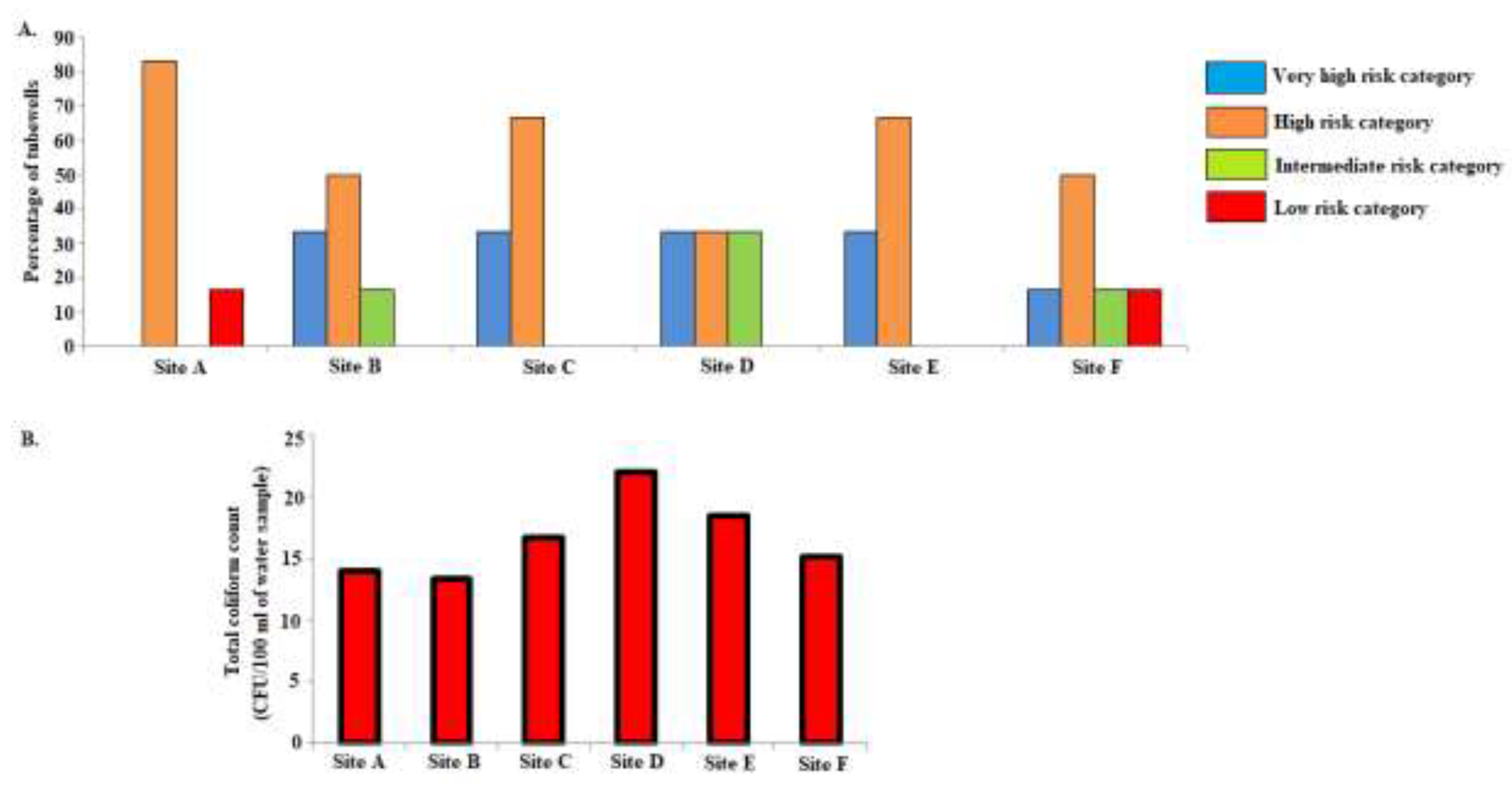

3.7. Risk Assessment of groundwater

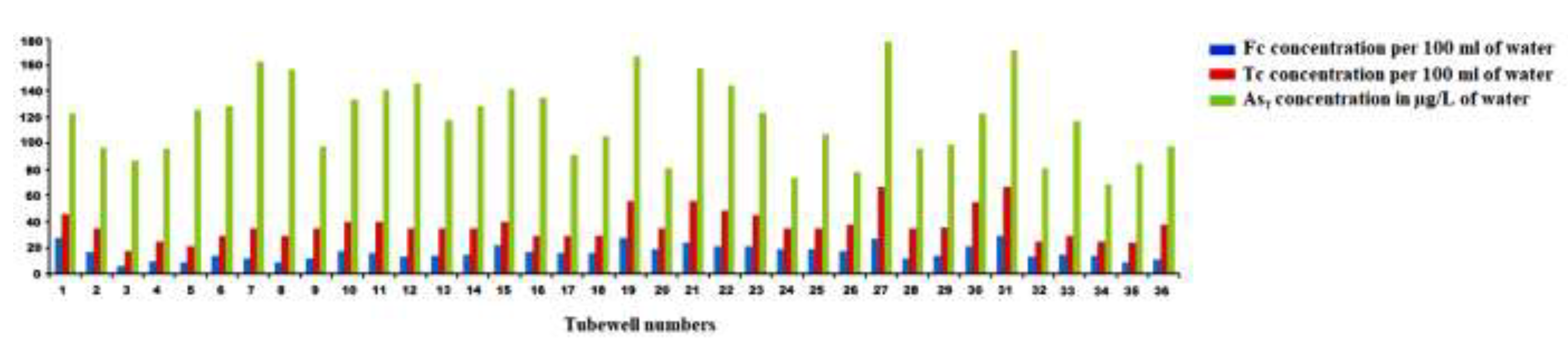

3.8. As heterogeneity and responsible taciturn factor

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Availability of data and materials

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

Ethics approval

Consent to participate

Code availability

Consent for publication

References

- Smith, A.H.; Lingas, E.O.; Rahman, M. Contamination of drinking-water by arsenic in Bangladesh: A public health emergency. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2000, 78, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar]

- Majumder, S.; Nath, B.; Sarkar, S.; Islam, S.M.; Bundschuh, J.; Chatterjee, D.; Hidalgo, M. Application of natural citric acid sources and their role on arsenic removal from drinking water: A green chemistry approach. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2013, 262, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumder, S.; Nath, B.; Sarkar, S.; Chatterjee, D.; Roman-Ross, G.; Hidalgo, M. Size-fractionation of groundwater arsenic in alluvial aquifers of West Bengal, India: The role of organic and inorganic colloids. Science of the Total Environment 2014, 468–469, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; et al. An Insight into the Spatio-vertical Heterogeneity of Dissolved Arsenic in Part of the Bengal Delta Plain Aquifer in West Bengal (India). In Safe and Sustainable Use of Arsenic-Contaminated Aquifers in the Gangetic Plain; Ramanathan, A., Johnston, S., Mukherjee, A., Nath, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Marguí, E.; Roman-Ross, G.; Chatterjee, D.; Hidalgo, M. Hollow fiber liquid phase microextraction combined with total reflection X-ray fluorescence spectrometry for the determination of trace level inorganic arsenic species in waters. Talanta 2020, 217, 121005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedley, P.L.; Kinniburgh, D.G. A review of the source, behaviour and distribution of arsenic in natural waters. Applied Geochemistry 2002, 17, 517–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Chen, C.; Wu, M.; Kuo, T. Cancer potential in liver, lung, bladder and kidney due to ingested inorganic arsenic in drinking water. British Journal of Cancer 1992, 66, 888–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Persson, L.-Å.; Nermell, B.; Arifeen, S.E.; Ekström, E.-C.; Smith, A.H.; Vahter, M. Arsenic exposure and risk of spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, and infant mortality. Epidemiology 2010, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvez, F.; Wasserman, G.A.; Factor-Litvak, P.; Liu, X.; Slavkovich, V.; Siddique, A.B.; Sultana, R.; Sultana, R.; Islam, T.; Levy, D. Arsenic exposure and motor function among children in Bangladesh. Environmental Health Perspectives 2011, 119, 1665–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenscroft, P.; Brammer, H.; Richards, K. Arsenic Pollution: A Global Synthesis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, D.; Halder, D.; Majumder, S.; Biswas, A.; Nath, B.; Bhattacharya, P.; Bhowmick, S.; Mukherjee-Goswami, A.; Saha, D.; Hazra, R.; et al. Assessment of arsenic exposure from groundwater and rice in Bengal Delta region, West Bengal, India. Water Research 2010, 44, 5803–5812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, D.; Roy, R.K.; Basu, B.B. Riddle of arsenic in groundwater of Bengal Delta Plain—Role of non-inland source and redox traps. Environmental Geology 2005, 49, 188–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Jacks, G.; Ahmed, K.M.; Routh, J.; Khan, A.A. Arsenic in Groundwater of the Bengal Delta Plain Aquifers in Bangladesh. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2002, 69, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, R.; Chattarjee, D.; Nath, B.; Jana, J.; Jacks, G.; Vahter, M. High Arsenic Groundwater: Mobilization, Metabolism and Mitigation-An overview in the Bengal Delta Plain. Journal of Molecular and Cellur Bio-Chemistry 2003, 253, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.F. Groundwater arsenic contamination on the Ganges Delta: Biogeochemistry, hydrology, human perturbations, and human suffering on a large scale. C.R. Geosci. 2005, 337, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M.; Polya, D.A.; Boyce, A.J.; Bryant, C.; Ballentine, C.J. Tracing organic matter composition and distribution and its role on arsenic release in shallow Cambodian groundwaters. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2016, 178, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Gault, A.; Boothman, C.; et al. Role of metal-reducing bacteria in arsenic release from Bengal delta sediments. Nature 2004, 430, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barman, S.; Mandal, D.; et al. Identification of microbiogeochemical factors responsible for arsenic release and mobilization, and isolation of heavy metal hyper-tolerant bacterium from irrigation well water: A case study in Rural Bengal. Environ Dev Sustain 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Datta, S.; Nath, B.; Neidhardt, H.; Sarkar, S.; Roman-Ross, G.; Berner, Z.; Hidalgo, M.; Chatterjee, D.; Chatterjee, D. Monsoonal influence on variation of hydrochemistry and isotopic signatures: Implications for associated arsenic release in groundwater. Journal of Hydrology 2016, 535, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oremland, R.S.; Stolz, J.F. The ecology of arsenic. Science 2003, 300, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oremland, R.S.; Stolz, J.F. Arsenic, microbes and contaminated aquifers. Trends Microbiol. 2005, 13, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappler, A.; Benz, M.; Schink, B.; Brune, A. Electron shuttling via humic acids in microbial iron(III) reduction in a freshwater sediment. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 47, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, B.; Berner, Z.; Chatterjee, D.; Mallik, S.B.; Stüben, D. Mobility of arsenic in West Bengal aquifers conducting low and high groundwater arsenic. Part II: Comparative geochemical profile and leaching study. Applied Geochemistry 2008, 23, 996–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Nath, B.; Bhattacharya, P.; Halder, D.; Kundu, A.K.; Mandal, U.; Mukherjee, A.; Chatterjee, D.; Mörth, C.M.; Jacks, G. Hydrogeochemical contrast between brown and grey sand aquifers in shallow depth of Bengal Basin: Consequences for Sustainable drinking water supply. Science of the Total Environment 2012, 431, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CGWB. High incidence of As in groundwater in West Bengal. Central Groundwater Board, India. Ministry of Water Resources, Government of India. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association (APHA). Standard Methods for the Analysis of Water and Wastewater, 17th ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241548151_eng.pdf.

- Howard, A.G. Water Supply Surveillance: A Reference Manual; WEDC, Loughborough University, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Haruna, R.; Ejobi, F.; Kabagambe, E.K. The Quality of water from protected springs in Katwe and Kisenyi parishes, Kampana city, Uganda. African Health Sciences 2005, 5, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality, Volume 3: Surveillance and Control of Community Water Supplies, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, H.A.; Voss, C.I. Estimation of regional-scale groundwater flow properties in the Bengal Basin of India and Bangladesh. Hydrogeol. J. 2009, 17, 1329–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; von Bromssen, M.; Scanlon, B.R.; Bhattacharya, P.; Fryar, A.E.; Hasan, M.A.; Ahmed, K.M.; Chatterjee, D.; Jacks, G.; Sracek, O. Hydrogeochemical comparison and effects of overlapping redox zones on groundwater arsenic near the western (Bhagirathi sub-basin, India) and Eatsren (Meghna sub-basin, Bangladesh) margins of the Bengal Basin. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 2008, 99, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, S.; MCArthur, J.M.; Sarkar, A.; Leng, M.J.; Ravenscroft, P.; Howarth, R.J.; Banerjee, D.M. Do Ponds Cause Arsenic-Pollution of Groundwater in the Bengal Basin? An Answer from West Bengal. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5156–5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.F.; Ashfaque, K.N.; Yu, W.; Badruzzaman, A.B.M.; Ali, M.A.; Oates, P.M.; Michael, H.A.; Neumann, R.B.; Beckie, R.; Islam, S.; et al. Groundwater dynamics and arsenic contamination in Bangladesh. Chem. Geol. 2006, 228, 112–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Siddika, A.; Khan, M.N.H.; Goldar, M.M.; Sadique, M.A.; Kabir, A.N.M.H.; Colwell, R.R. Microbiological analysis of tube-well water in a rural area of Bangladesh. Applied Environmental Microbiology 2001, 67, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geen, A.; Radloff, K.A.; Aziz, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Huq, M.R.; Ahmed, K.M.; Weinman, B.; Goodbred, S.; Jung, H.B.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Comparison of arsenic concentrations in simultaneously-collected groundwater and aquifer particles from Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, and Nepal. Appl. Geochem. 2008, 23, 3244–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, B.; Norra, S.; Chatterjee, D.; Stuben, D. Finger Printing of Land Use Related Chemical patterns in Street Sediment from Kolkata, India. Environmental Forensics 2007, 313–328, Neumann, R.B.; Ashfaque, K.N.; Badruzzaman, A.B.M.; Ali, M.A.; Shoemaker, J.K.; Harvey, C.F. Anthropogenic influence on groundwater arsenic concentration in Bangladesh. Nat Geosci 2010, 3, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendorf, S.; Michael, H.A.; van Geen, A. Spatial and temporal variations of groundwater arsenic in south and southeast Asia. Science 2010, 328, 1123–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, C.; Matschullat, J.; Birke, M.; Salminen, R. Arsenic distribution in the environment: The effects of scale. Applied Geochemistry 2009, 24, 1147–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamed, D. Monitoring arsenic in the environment: A review of science and technologies with the potential for field measurements. Analytica Chimica Acta 2005, 532, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matschullat, J. Arsenic in the geosphere—A review. Sci. Tot. Environ. 2000, 249, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postma, D.; Larsen, F.; Hue, N.T.M.; Duc, M.T.; Viet, P.H.; Nhan, P.Q.; Jessen, S. Arsenic in groundwater of the Red River floodplain, Vietnam: Controlling geochemical processes and reactive transport modeling. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2007, 71, 5054–5071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlet, L.; Chakraborty, S.; Appelo, C.; Roman-Ross, G.; Nath, B.; Ansari, A.; Lanson, M.; Chatterjee, D.; Mallik, S.B. Chemodynamics of an arsenic “hotspot” in a West Bengal aquifer: A field and reactive transport modeling study. Applied geochemistry 2007, 22, 1273–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocar, B.D.; Poliozotto, M.L.; Bebber, S.G.; Ying, S.C.; Ung, M.; Ouch, K.; Samreth, S.; Suy, B.; Phan, K.; Sampson, M.; et al. Integrated biogeochemical and hydrologic processes driving arsenic release from shallow sediments to groundwaters of the Mekong delta. Appl. Geochem. 2008, 23, 3059–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizzotto, M.L.; Kocar, B.D.; Benner, S.G.; Sampson, M.; Fendorf, S. Near-surface wetland sediments as a source of arsenic release to ground water in Asia. Nature 2008, 454, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Neal, A.W.; Mohajerin, T.J.; Ocheltree, T.; Rosenheim, B.E.; White, C.D.; Johannesson, K.H. Perennial ponds are not an important source of water or dissolved organic matter to groundwaters with high arsenic concentrations in West Bengal, India. Geophysical Research Letters 2011, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MCArthur, J.M.; Ravenscroft, P.; Banerjee, D.M.; Milsom, J.; Hudson-Edwards, K.A.; Sengupta, S.; Bristow, C.; Sarkar, A.; Tonkin, S.; Purohit, R. How paleosols influence groundwater flow and arsenic pollution: A model from the Bengal Basin and its worldwide implication. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenscroft, P.; MC arthur, J.M.; Hoque, B.A. Geochemical and palaeohydrological controls on pollution of groundwater by arsenic. In Arsenic Exposure and Health Effects; Chappel, W.R., Abernathy, C.O., Calderon, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2001; pp. 53–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, M.; Polya, D.A.; Boyce, A.J.; Bryant, C.; Mondal, D.; Shantz, A.; Ballentine, C.J. Pond-derived organic carbon driving changes in arsenic hazard found in Asian groundwaters. Environmental Science & Technology 2013, 47, 7085–7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovley, D.R.; Coates, J.D.; Blunt-harris, E.L.; Phillips, E.J.P.; Woodward, J.C. Humic substances as electron acceptors for microbial respiration. Nature 1996, 382, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, S.; Halder, D.; Kundu, A.K.; Saha, D.; Iglesias, M.; Nriagu, J.; Guha Mazumder, D.N.; Roman-Ross, G.; Chatterjee, D. Is saliva a potential biomarker of arsenic exposure? A case-control study in West Bengal, India. Environmental Science & Technology 2013, 47, 3326–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Bhattacharya, P.; Mukherjee, A.; Nath, B.; Alexanderson, H.; Kundu, A.K.; Chatterjee, D.; Jacks, G. Shallow hydrostratigraphy in an arsenic affected region of Bengal Basin: Implication for targeting safe aquifers for drinking water supply. Science of the Total Environment 2014, 485–486, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, T.; Kuramitz, H.; Hata, N.; Taguchi, S.; Murai, K.; Okauchi, K. Visual colorimetry for determination of trace arsenic in groundwater based on improved molybdenum blue spectrophotometry. Analytical Methods 2015, 7, 2794–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, R.E.; Jenne, E.A.; Ball, J.W. Chemical studies of selected trace elements in hot spring drainages of YelIowstone National Park. U.S. Geol. Survey Pro$ Paper Series 1044F. 1980; 20p. [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar, J.; Voegelin, A.; Maurer, F.; Roberts, L.C.; Hug, S.J.; Saha, G.C.; Kretzschmar, R. Arsenic in Soil and Irrigation Water Affects Arsenic Uptake by Rice: Complementary Insights from Field and Pot Studies. Environmental Science & Technology 2010, 44, 8842–8848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Brömssen, M.; Häller Larsson, S.; Bhattacharya, P.; Hasan, M.A.; Ahmed, K.M.; Jakariya, M.; Jacks, G. Geochemical characterisation of shallow aquifer sediments of MatlabUpazila, Southeastern Bangladesh—Implications for targeting low-As aquifers. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 2008, 99, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Chatterjee, D.; Jacks, G. Occurrence of arsenic contaminated groundwater in alluvial aquifers from Delta Plains, Eastern India: Options for safe drinking water supply. International Journal of Water Resources Development 1997, 13, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Excreta and Greywater Use in Agriculture. In Excreta and Greywater; Guidelines for the Safe Use of Wastewater; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Volume 4, https://www.who.int/publications.

- World Health Organization. Safely Managed Drinking Water—Thematic Report on Drinking Water 2. 2017. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/325897 (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Kgopa, P.M.; Mashela, P.W.; Manyevere, A. Microbial quality of treated wastewater and borehole water used for irrigation in a semi-arid area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo, K.K.; Mensah, G.I.; Donkor, B.; Bonsu, C.; Akyeh, M.L. Bacteriological quality of bottled water sold on the Ghanaian market. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development 2009, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, A.H.M.E.; Chakraborty, T.K.; Ghosh, G.C. Bio-Sand Filter (BSF): A Simple Water Treatment Device for Safe Drinking water Supply and to Promote Health in Hazard Prone Hard-to-Reach Coastal Areas of Bangladesh. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Frisnie, S.H.; Ortega, R.; Maynard, D.M.; Sarkar, B. The concentrations of arsenic and other toxic elements in Bangladesh. Environmental Health Perspective 2002, 110, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercumen, A.; Pickering, A.J.; Kwong, L.H.; Arnold, B.F.; Parvez, S.M.; Alam, M.; Sen, D.; Islam, S.; Kullmann, C.; Chase, C.; et al. Animal Feces Contribute to Domestic Fecal Contamination: Evidence from E. coli Measured in Water, Hands, Food, Flies, and Soil in Bangladesh. Environ Sci Technol. 2017, 51, 8725–8734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geen, A.; Ahmed, K.M.; Akita, Y.; Alam, M.J.; Culligan, P.J.; Emch, M.; Yunus, M. Fecal Contamination of Shallow Tube wells in Bangladesh Inversely Related to Arsenic. Environmental Science & Technology 2012, 45, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Nakamura, T.; Malla, R.; Nishida, K. Seasonal variation in the microbial quality of shallow groundwater in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Water Science & Technology: Water Supply 2014, 14, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Nkedi-Kizza, P.; Wu, Q.T.; Shinde, D.; Huang, C.H. Assessment of seasonal variations in surface water quality. Water Res. 2006, 40, 3800–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Physical Parameters | Max | Min | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | 31.2 | 23.4 | 27.3 |

| pH | 8.31 | 7.04 | 7.43 |

| Conductivity (µScm−1) | 876 | 423 | 538.7 |

| Eh (mV) | 459 | -161 | 278 |

| DO (mgL−1) | 0.3 | BDL | BDL |

| TDS (mgL−1) | 561 | 271 | 345 |

| Chemical Parameters | Max | Min | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCO3− (mgL−1) | 388 | 83 | 222 |

| Ca+2 (mgL−1) | 341 | 186 | 274 |

| Mg+2 (mgL−1) | 192 | 56 | 98 |

| Cl− (mgL−1) | 147 | 1 | 21 |

| PO43− (mgL−1) | 3.24 | 0.96 | 2.26 |

| SO42− (mgL−1) | 16.8 | 3.53 | 8.96 |

| NO3 − (mgL−1) | 0.07 | --- | 0.04 |

| NH4+ (mgL−1) | 4.52 | 2.03 | 2.64 |

| DOC (mgL−1) | 3.96 | 0.57 | 2.35 |

| Na+ (mgL−1) | 31.4 | 11.5 | 24.3 |

| K+ (mgL−1) | 12.6 | 5.17 | 8.32 |

| FeT (mgL−1) | 8.94 | 4.78 | 5.87 |

| % Fe (II) | 98.5 | 69.6 | 93.6 |

| AsT (µgL−1) | 178 | 69 | 118.58 |

| % As (III) | 119 | 82.4 | 95.6 |

| Microbial parameters | Groundwater | Surface water (at 10−3 dilution) |

|---|---|---|

| Total coliform count (CFU/100 ml of the water sample) |

Range: 18 to 67 | Range: 229 to 684 |

| Mean: 37.08 ± 11.71 | Mean: 484.03 ± 98.95 | |

| Faecal coliform count (CFU/100 ml of the water sample) |

Range: 6 to 29 | Range: 88 to 378 |

| Mean: 16.61 ± 5.77 | Mean: 252.75 ± 78.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).