Submitted:

27 June 2023

Posted:

28 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Search Methods

3. A Brief History of Meal Timings

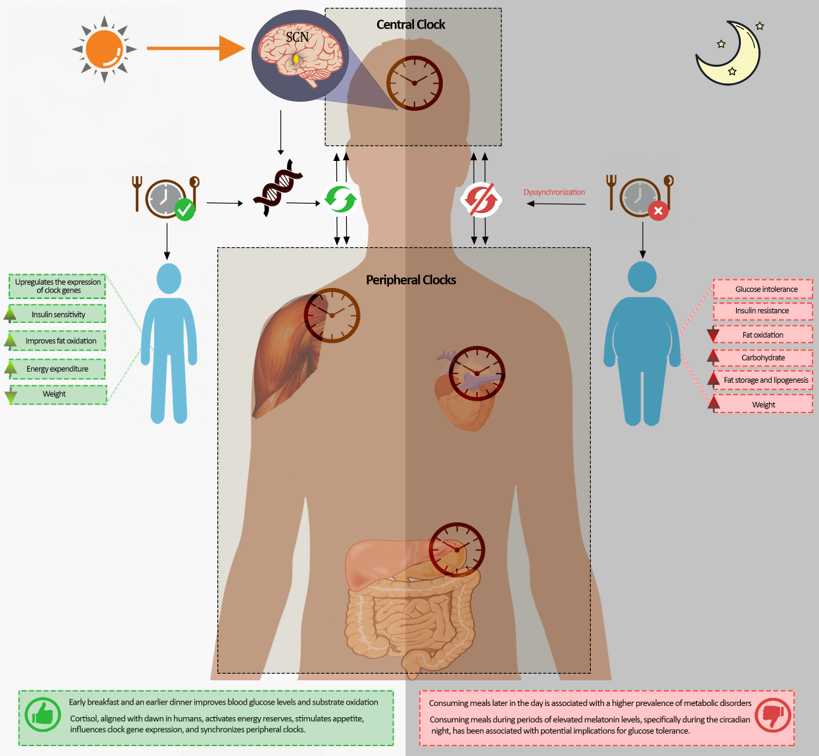

4. Regulation and Control of the Circadian Body Clocks

5. Clock Genes and Circadian Rhythms

6. Mealtime and cardiometabolic risk

7. Dawn and Dusk Feeding Time: The Transition from Fasting to Feeding and Feeding to Fasting

7.1. Time of the Day and Clock Genes

7.2. Early morning meal

7.3. Energy Expenditure and Circadian Rhythm

7.4. Mealtime, Insulin Sensitivity, and Glucose Response

7.5. Early Breakfast or No Early Breakfast

7.6. Skipping Breakfast and Genetics

7.7. Evening and Late Night Meals

8. The Interaction between Mealtime and Circadian Hormones

9. Cortisol

10. Melatonin

11. Meal timing, Circadian Rhythm, and Gut Microbiota

12. Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ndisang, J.F.; Rastogi, S. Cardiometabolic diseases and related complications: Current status and future perspective. Biomed Res Int 2013, 2013, 467682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowicz, D.; Rosenblum, R.C.; Wainstein, J.; Twito, O. Influence of Fasting until Noon (Extended Postabsorptive State) on Clock Gene mRNA Expression and Regulation of Body Weight and Glucose Metabolism. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reppert, S.M.; Weaver, D.R. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature 2002, 418, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinpar, A.; Chaix, A.; Panda, S. Daily Eating Patterns and Their Impact on Health and Disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2016, 27, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.P., Jr.; McHill, A.W.; Birks, B.R.; Griffin, B.R.; Rusterholz, T.; Chinoy, E.D. Entrainment of the human circadian clock to the natural light-dark cycle. Curr Biol 2013, 23, 1554–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Iglesia, H.O.; Fernandez-Duque, E.; Golombek, D.A.; Lanza, N.; Duffy, J.F.; Czeisler, C.A.; et al. Access to Electric Light Is Associated with Shorter Sleep Duration in a Traditionally Hunter-Gatherer Community. J Biol Rhythms 2015, 30, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeneessier, A.S.; Pandi Perumal, S.R.; BaHammam, A.S. Intermittent fasting, insufficient sleep, and circadian rhythm: Interaction and impact on the cardiometabolic system. Current Sleep Medicine Reports 2018, 4, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHill, A.W.; Melanson, E.L.; Higgins, J.; Connick, E.; Moehlman, T.M.; Stothard, E.R.; et al. Impact of circadian misalignment on energy metabolism during simulated nightshift work. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014, 111, 17302–17307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.J.; Yang, J.N.; Garcia, J.I.; Myers, S.; Bozzi, I.; Wang, W.; et al. Endogenous circadian system and circadian misalignment impact glucose tolerance via separate mechanisms in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015, 112, E2225–E2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.J.; Purvis, T.E.; Hu, K.; Scheer, F.A. Circadian misalignment increases cardiovascular disease risk factors in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016, 113, E1402–E1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BaHammam, A.S.; Almeneessier, A.S. Recent Evidence on the Impact of Ramadan Diurnal Intermittent Fasting, Mealtime, and Circadian Rhythm on Cardiometabolic Risk: A Review. Front Nutr 2020, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado-Delgado, R.; Angeles-Castellanos, M.; Saderi, N.; Buijs, R.M.; Escobar, C. Food intake during the normal activity phase prevents obesity and circadian desynchrony in a rat model of night work. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, K.G.; Reid, K.J.; Horn, L.V.; Zee, P.C. Contribution of evening macronutrient intake to total caloric intake and body mass index. Appetite 2013, 60, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHill, A.W.; Phillips, A.J.; Czeisler, C.A.; Keating, L.; Yee, K.; Barger, L.K.; et al. Later circadian timing of food intake is associated with increased body fat. Am J Clin Nutr 2017, 106, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, H.; Ushijima, K.; Shimba, S.; Fujimura, A. Daily Fasting Blood Glucose Rhythm in Male Mice: A Role of the Circadian Clock in the Liver. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oster, H.; Damerow, S.; Kiessling, S.; Jakubcakova, V.; Abraham, D.; Tian, J.; et al. The circadian rhythm of glucocorticoids is regulated by a gating mechanism residing in the adrenal cortical clock. Cell Metab 2006, 4, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paré, G.; Kitsiou, S. Methods for Literature Reviews. In Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach; Lau, F., Kuziemsky, C., Eds.; University of Victoria: Victoria, British Columbia, 2017; pp. 157–179. [Google Scholar]

- Templier, M.; Paré, G. Transparency in literature reviews: An assessment of reporting practices across review types and genres in top IS journals. European Journal of Information Systems 2018, 27, 503–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, H.S.; Scheer, F.; Saxena, R.; Garaulet, M. Timing of Food Intake: Identifying Contributing Factors to Design Effective Interventions. Adv Nutr 2019, 10, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjellström, C. Mealtime and meal patterns from a cultural perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Nutrition 2004, 48, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, E.; Shohet, M. The cultural structuring of mealtime socialization. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev 2006, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinotto, S. Everyone would be around the table: American family mealtimes in historical perspective, 1850–1960. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 2006, 111, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterman, D. Breakfast, lunch and dinner: Have we always eaten them? BBC News Magazine [Internet]. 2012. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-20243692 (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Eating with the Chinese body clock: Queiscence: Acupuncture & Apothecary. 2016. Available online: https://chinesemedicinemelbourne.com.au/eating-with-the-chinese-body-clock/ (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- McMillan, S. What Time is Dinner? History Magazine [Internet]. 2001. Available online: https://www.history-magazine.com/dinner2.html (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- BaHammam, A.S.; Alghannam, A.F.; Aljaloud, K.S.; Aljuraiban, G.S.; AlMarzooqi, M.A.; Dobia, A.M.; et al. Joint consensus statement of the Saudi Public Health Authority on the recommended amount of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep duration for healthy Saudis: Background, methodology, and discussion. Ann Thorac Med 2021, 16, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, A.K.; Graubard, B.I. 40-year trends in meal and snack eating behaviors of American adults. J Acad Nutr Diet 2015, 115, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.; Panda, S. A Smartphone App Reveals Erratic Diurnal Eating Patterns in Humans that Can Be Modulated for Health Benefits. Cell Metab 2015, 22, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumanova, V.S.; Okuliarova, M.; Foppen, E.; Kalsbeek, A.; Zeman, M. Exposure to dim light at night alters daily rhythms of glucose and lipid metabolism in rats. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 973461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laake, L.W.; Luscher, T.F.; Young, M.E. The circadian clock in cardiovascular regulation and disease: Lessons from the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2017. Eur Heart J 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manella, G.; Bolshette, N.; Golik, M.; Asher, G. Input integration by the circadian clock exhibits nonadditivity and fold-change detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2022, 119, e2209933119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripperger, J.A.; Schibler, U. Rhythmic CLOCK-BMAL1 binding to multiple E-box motifs drives circadian Dbp transcription and chromatin transitions. Nat Genet 2006, 38, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patke, A.; Young, M.W.; Axelrod, S. Molecular mechanisms and physiological importance of circadian rhythms. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelinski, E.L.; Deibel, S.H.; McDonald, R.J. The trouble with circadian clock dysfunction: Multiple deleterious effects on the brain and body. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2014, 40, 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Onge, M.P.; Ard, J.; Baskin, M.L.; Chiuve, S.E.; Johnson, H.M.; Kris-Etherton, P.; et al. Meal Timing and Frequency: Implications for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 135, e96–e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birnie, M.T.; Claydon, M.D.B.; Troy, O.; Flynn, B.P.; Yoshimura, M.; Kershaw, Y.M.; et al. Circadian regulation of hippocampal function is disrupted with corticosteroid treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2023, 120, e2211996120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsalobre, A.; Brown, S.; Marcacci, L.; Tronche, F.; Kellendonk, C.; Reichardt, H.; et al. Resetting of circadian time in peripheral tissues by glucocorticoid signaling. Science 2000, 289, 2344–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, K.; Kon, N.; Iizuka, K.; Fukada, Y.; Sakurai, T.; Hirano, A. Singularity response reveals entrainment properties in mammalian circadian clock. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reutrakul, S.; Knutson, K.L. Consequences of circadian disruption on cardiometabolic health. Sleep Med Clin 2015, 10, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saran, A.R.; Dave, S.; Zarrinpar, A. Circadian Rhythms in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1948–1966.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasmari, A.A.; Al-Khalifah, A.S.; BaHammam, A.S.; Alodah, A.S.; Almnaizel, A.T.; Alshiban, N.M.S.; et al. Ramadan Fasting Model Exerts Hepatoprotective, Anti-obesity, and Anti-Hyperlipidemic Effects in an Experimentally-induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver in Rats. Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Lajoie, P.; Aronson, K.J.; Day, A.; Tranmer, J. A cross-sectional study of shift work, sleep quality and cardiometabolic risk in female hospital employees. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, C.; Tamura, T.; Wada, K.; Konishi, K.; Goto, Y.; Nagao, Y.; et al. Sleep duration, nightshift work, and the timing of meals and urinary levels of 8-isoprostane and 6-sulfatoxymelatonin in Japanese women. Chronobiol Int 2017, 34, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; He, Y.; Xie, S.; et al. Meta-analysis on night shift work and risk of metabolic syndrome. Obesity reviews: An official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 2014, 15, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Diaz-Del-Campo, N.; Castelnuovo, G.; Caviglia, G.P.; Armandi, A.; Rosso, C.; Bugianesi, E. Role of Circadian Clock on the Pathogenesis and Lifestyle Management in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arble, D.M.; Bass, J.; Behn, C.D.; Butler, M.P.; Challet, E.; Czeisler, C.; et al. Impact of Sleep and Circadian Disruption on Energy Balance and Diabetes: A Summary of Workshop Discussions. Sleep 2015, 38, 1849–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijo-Ferreira, F.; Takahashi, J.S. Genomics of circadian rhythms in health and disease. Genome Medicine 2019, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konopka, R.J.; Benzer, S. Clock mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1971, 68, 2112–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruben, M.D.; Wu, G.; Smith, D.F.; Schmidt, R.E.; Francey, L.J.; Lee, Y.Y.; et al. A database of tissue-specific rhythmically expressed human genes has potential applications in circadian medicine. Sci Transl Med 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaterna, M.H.; King, D.P.; Chang, A.M.; Kornhauser, J.M.; Lowrey, P.L.; McDonald, J.D.; et al. Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene, Clock, essential for circadian behavior. Science 1994, 264, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.P.; Zhao, Y.; Sangoram, A.M.; Wilsbacher, L.D.; Tanaka, M.; Antoch, M.P.; et al. Positional cloning of the mouse circadian clock gene. Cell 1997, 89, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsius, Y.G.; Zurbriggen, M.D.; Kim, J.K.; Kas, M.J.; Meerlo, P.; Aton, S.J.; et al. The role of clock genes in sleep, stress and memory. Biochem Pharmacol 2021, 191, 114493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, J.S. Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat Rev Genet 2017, 18, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowrey, P.L.; Takahashi, J.S. Genetics of the mammalian circadian system: Photic entrainment, circadian pacemaker mechanisms, and posttranslational regulation. Annu Rev Genet 2000, 34, 533–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marri, D.; Filipovic, D.; Kana, O.; Tischkau, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Prediction of mammalian tissue-specific CLOCK–BMAL1 binding to E-box DNA motifs. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, C.; Silvestre-Roig, C.; Ortega-Gomez, A.; Lemnitzer, P.; Poelman, H.; Schumski, A.; et al. Chrono-pharmacological Targeting of the CCL2-CCR2 Axis Ameliorates Atherosclerosis. Cell Metab 2018, 28, 175–182.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, A.; Gupta, R.; Makwana, K.; Kondratov, R. Circadian clocks, diets and aging. Nutr Healthy Aging 2017, 4, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollmers, C.; Gill, S.; DiTacchio, L.; Pulivarthy, S.R.; Le, H.D.; Panda, S. Time of feeding and the intrinsic circadian clock drive rhythms in hepatic gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009, 106, 21453–21458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahara, Y.; Otsuka, M.; Fuse, Y.; Hirao, A.; Shibata, S. Refeeding after fasting elicits insulin-dependent regulation of Per2 and Rev-erbalpha with shifts in the liver clock. J Biol Rhythms 2011, 26, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiola, F.; Le Minh, N.; Preitner, N.; Kornmann, B.; Fleury-Olela, F.; Schibler, U. Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev 2000, 14, 2950–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokkan, K.A.; Yamazaki, S.; Tei, H.; Sakaki, Y.; Menaker, M. Entrainment of the circadian clock in the liver by feeding. Science 2001, 291, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfumey, L.; Mongeau, R.; Hamon, M. Biological rhythms and melatonin in mood disorders and their treatments. Pharmacol Ther 2013, 138, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderram, J.; Sofou, S.; Kamisoglu, K.; Karantza, V.; Androulakis, I.P. Time-restricted feeding and the realignment of biological rhythms: Translational opportunities and challenges. J Transl Med 2014, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, K.; Pivovarova-Ramich, O. Meal Timing, Aging, and Metabolic Health. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pot, G.K. Chrono-nutrition—An emerging, modifiable risk factor for chronic disease? Nutrition Bulletin 2021, 46, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, K.C.; Goel, N. Timing of eating in adults across the weight spectrum: Metabolic factors and potential circadian mechanisms. Physiology & Behavior 2018, 192, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, H.E. The effect of time of eating on cardiometabolic risk in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2023, e3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knutsson, A.; Karlsson, B.; Ornkloo, K.; Landstrom, U.; Lennernas, M.; Eriksson, K. Postprandial responses of glucose, insulin and triglycerides: Influence of the timing of meal intake during night work. Nutr Health 2002, 16, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A.B.; Coates, A.M.; Davidson, Z.E.; Bonham, M.P. Dietary Patterns under the Influence of Rotational Shift Work Schedules: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv Nutr 2023, 14, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.; Jang, K.A.; Kim, H.R.; Kang, M.S.; Lee, K.W.; Shin, D. Identifying the Associations of Nightly Fasting Duration and Meal Timing with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Using Data from the 2016-2020 Korea National Health and Nutrition Survey. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshed, H.; Beyl, R.A.; Della Manna, D.L.; Yang, E.S.; Ravussin, E.; Peterson, C.M. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves 24-Hour Glucose Levels and Affects Markers of the Circadian Clock, Aging, and Autophagy in Humans. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, E.F.; Beyl, R.; Early, K.S.; Cefalu, W.T.; Ravussin, E.; Peterson, C.M. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even without Weight Loss in Men with Prediabetes. Cell Metab 2018, 27, 1212–1221.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Montes, E.; Rodriguez-Barranco, M.; Ching-Lopez, A.; Artacho, R.; Huerta, J.M.; Amiano, P.; et al. Circadian clock gene variants and their link with chronotype, chrononutrition, sleeping patterns and obesity in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC) study. Clin Nutr 2022, 41, 1977–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.E.; Lane, J.M.; Wood, A.R.; van Hees, V.T.; Tyrrell, J.; Beaumont, R.N.; et al. Genome-wide association analyses of chronotype in 697,828 individuals provides insights into circadian rhythms. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, C.; Espitia-Bautista, E.; Guzmán-Ruiz, M.A.; Guerrero- Vargas, N.N.; Hernández-Navarrete, M.Á.; Ángeles-Castellanos, M.; et al. Chocolate for breakfast prevents circadian desynchrony in experimental models of jet-lag and shift-work. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 6243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Doi, M.; Okamura, H. Effect of Daily Light on c-Fos Expression in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus under Jet Lag Conditions. Acta Histochem Cytochem 2018, 51, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruddick-Collins, L.C.; Morgan, P.J.; Johnstone, A.M. Mealtime: A circadian disruptor and determinant of energy balance? J Neuroendocrinol 2020, 32, e12886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, S.; Beretoulis, S.; Deere, A.; Radenkovic, D. The Window Matters: A Systematic Review of Time Restricted Eating Strategies in Relation to Cortisol and Melatonin Secretion. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daan, S.; Albrecht, U.; van der Horst, G.T.; Illnerova, H.; Roenneberg, T.; Wehr, T.A.; et al. Assembling a clock for all seasons: Are there M and E oscillators in the genes? J Biol Rhythms 2001, 16, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, A.B.A.; da Cunha, L.S.; Machado, C.B.; de Pinho Pessoa, F.M.C.; Silva, A.; Ribeiro, R.M.; et al. Circadian Rhythm Dysregulation and Leukemia Development: The Role of Clock Genes as Promising Biomarkers. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 8212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinturel, F.; Gos, P.; Petrenko, V.; Hagedorn, C.; Kreppel, F.; Storch, K.F.; et al. Circadian hepatocyte clocks keep synchrony in the absence of a master pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus or other extrahepatic clocks. Genes Dev 2021, 35, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, M.; Leiva, M.; Sabio, G. Circadian Clock and Liver Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, K.H.; Takahashi, J.S. Circadian clock genes and the transcriptional architecture of the clock mechanism. J Mol Endocrinol 2019, 63, R93–R102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschoff, J.; von Goetz, C.; Wildgruber, C.; Wever, R.A. Meal timing in humans during isolation without time cues. J Biol Rhythms 1986, 1, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Estrada, D.; Aguilar-Roblero, R.; Alva-Sanchez, C.; Villanueva, I. The homeostatic feeding response to fasting is under chronostatic control. Chronobiol Int 2018, 35, 1680–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosensweig, C.; Green, C.B. Periodicity, repression, and the molecular architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Eur J Neurosci 2020, 51, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hira, T.; Trakooncharoenvit, A.; Taguchi, H.; Hara, H. Improvement of Glucose Tolerance by Food Factors Having Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Releasing Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froy, O.; Garaulet, M. The Circadian Clock in White and Brown Adipose Tissue: Mechanistic, Endocrine, and Clinical Aspects. Endocr Rev 2018, 39, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenvers, D.J.; Jongejan, A.; Atiqi, S.; Vreijling, J.P.; Limonard, E.J.; Endert, E.; et al. Diurnal rhythms in the white adipose tissue transcriptome are disturbed in obese individuals with type 2 diabetes compared with lean control individuals. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistlberger, R.E. Neurobiology of food anticipatory circadian rhythms. Physiology & Behavior 2011, 104, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, H.; Yoshida, H. Beneficial Effects of Adiponectin on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism and Atherosclerotic Progression: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlot, A.; Hutt, F.; Sabatier, E.; Zoll, J. Beneficial Effects of Early Time-Restricted Feeding on Metabolic Diseases: Importance of Aligning Food Habits with the Circadian Clock. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddick-Collins, L.C.; Morgan, P.J.; Fyfe, C.L.; Filipe, J.A.N.; Horgan, G.W.; Westerterp, K.R.; et al. Timing of daily calorie loading affects appetite and hunger responses without changes in energy metabolism in healthy subjects with obesity. Cell Metab 2022, 34, 1472–1485.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancolin, A.D.; Martchenko, A.; Mitova, E.; Gurges, P.; Michalchyshyn, E.; Chalmers, J.A.; et al. The core clock gene, Bmal1, and its downstream target, the SNARE regulatory protein secretagogin, are necessary for circadian secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1. Mol Metab 2020, 31, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, M.E.; Vitiello, M.V.; Abdelrahim, D.N.; Cheikh Ismail, L.; Jahrami, H.A.; Khaleel, S.; et al. Eating habits are associated with subjective sleep quality outcomes among university students: Findings of a cross-sectional study. Sleep Breath 2022, 26, 1365–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Qu, D.; Liang, K.; Bao, R.; Chen, S. Eating habits matter for sleep difficulties in children and adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyar, K.A.; Ciciliot, S.; Wright, L.E.; Bienso, R.S.; Tagliazucchi, G.M.; Patel, V.R.; et al. Muscle insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism are controlled by the intrinsic muscle clock. Mol Metab 2014, 3, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Lozano, M.; Mingomataj, E.L.; Wu, W.K.; Ridout, S.A.; Brubaker, P.L. Circadian secretion of the intestinal hormone GLP-1 by the rodent L cell. Diabetes 2014, 63, 3674–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, J.; Hou, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Su, Z. Identification of insulin as a novel retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor alpha target gene. FEBS Lett 2014, 588, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, A.V.; Bensellam, M.; Wauters, E.; Rees, M.; Giry-Laterriere, M.; Mawson, A.; et al. Pancreas-Specific Sirt1-Deficiency in Mice Compromises Beta-Cell Function without Development of Hyperglycemia. PLoS ONE. 2015, 10, e0128012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.; Dalla Man, C.; Nandy, D.K.; Levine, J.A.; Bharucha, A.E.; Rizza, R.A.; et al. Diurnal pattern to insulin secretion and insulin action in healthy individuals. Diabetes 2012, 61, 2691–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, J.; Imai, S. A clock ticks in pancreatic beta cells. Cell Metab 2010, 12, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrens, S.M.T.; Christou, S.; Isherwood, C.; Middleton, B.; Gibbs, M.A.; Archer, S.N.; et al. Meal Timing Regulates the Human Circadian System. Current Biology: CB 2017, 27, 1768–1775.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandin, C.; Scheer, F.A.; Luque, A.J.; Avila-Gandia, V.; Zamora, S.; Madrid, J.A.; et al. Meal timing affects glucose tolerance, substrate oxidation and circadian-related variables: A randomized, crossover trial. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015, 39, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, S.; Fadda, M.; Castiglione, A.; Ciccone, G.; De Francesco, A.; Fedele, D.; et al. Is the timing of caloric intake associated with variation in diet-induced thermogenesis and in the metabolic pattern? A randomized cross-over study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015, 39, 1689–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, M.C.; Engen, P.A.; Bandin, C.; Cabrera-Rubio, R.; Voigt, R.M.; Green, S.J.; et al. Timing of food intake impacts daily rhythms of human salivary microbiota: A randomized, crossover study. FASEB J 2018, 32, 2060–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoogian, E.N.C.; Zadourian, A.; Lo, H.C.; Gutierrez, N.R.; Shoghi, A.; Rosander, A.; et al. Feasibility of time-restricted eating and impacts on cardiometabolic health in 24-h shift workers: The Healthy Heroes randomized control trial. Cell Metab 2022, 34, 1442–1456.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, C.J.; Purvis, T.E.; Mistretta, J.; Scheer, F.A. Effects of the Internal Circadian System and Circadian Misalignment on Glucose Tolerance in Chronic Shift Workers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016, 101, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Tajiri, E.; Hatamoto, Y.; Ando, T.; Shimoda, S.; Yoshimura, E. Eating Dinner Early Improves 24-h Blood Glucose Levels and Boosts Lipid Metabolism after Breakfast the Next Day: A Randomized Cross-Over Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizinger, T.; Kovtun, K.; RoyChoudhury, A.; Laferrere, B.; Shechter, A.; St-Onge, M.P. Pilot study of sleep and meal timing effects, independent of sleep duration and food intake, on insulin sensitivity in healthy individuals. Sleep Health 2018, 4, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Dalla Man, C.; Morris, C.J.; Cobelli, C.; Scheer, F. Differential effects of the circadian system and circadian misalignment on insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion in humans. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018, 20, 2481–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Laurenti, M.C.; Dalla Man, C.; Varghese, R.T.; Cobelli, C.; Rizza, R.A.; et al. Glucose metabolism during rotational shift-work in healthcare workers. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1483–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Sun, Y.; Ye, Y.; Hu, D.; Zhang, H.; He, Z.; et al. Randomized controlled trial for time-restricted eating in healthy volunteers without obesity. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, A.T.; Regmi, P.; Manoogian, E.N.C.; Fleischer, J.G.; Wittert, G.A.; Panda, S.; et al. Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Glucose Tolerance in Men at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2019, 27, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Pabla, P.; Mallinson, J.; Nixon, A.; Taylor, T.; Bennett, A.; et al. Two weeks of early time-restricted feeding (eTRF) improves skeletal muscle insulin and anabolic sensitivity in healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr 2020, 112, 1015–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitting, K.M.; Vujovic, N.; Yuan, R.K.; Isherwood, C.M.; Medina, J.E.; Wang, W.; et al. Human Resting Energy Expenditure Varies with Circadian Phase. Curr Biol 2018, 28, 3685–3690.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.J.; Garcia, J.I.; Myers, S.; Yang, J.N.; Trienekens, N.; Scheer, F.A. The Human Circadian System Has a Dominating Role in Causing the Morning/Evening Difference in Diet-Induced Thermogenesis. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015, 23, 2053–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bideyan, L.; Nagari, R.; Tontonoz, P. Hepatic transcriptional responses to fasting and feeding. Genes Dev 2021, 35, 635–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romon, M.; Edme, J.L.; Boulenguez, C.; Lescroart, J.L.; Frimat, P. Circadian variation of diet-induced thermogenesis. Am J Clin Nutr 1993, 57, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosjean, E.; Simonneaux, V.; Challet, E. Reciprocal Interactions between Circadian Clocks, Food Intake, and Energy Metabolism. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, T.; Raff, H.; Findling, J.W. Late-night salivary cortisol measurement in the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2008, 4, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelund, U.; Hansen, T.K.; Hojlund, K.; Beck-Nielsen, H.; Clausen, J.T.; Hansen, B.S.; et al. Fasting unmasks a strong inverse association between ghrelin and cortisol in serum: Studies in obese and normal-weight subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005, 90, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrila, A.; Peng, C.K.; Chan, J.L.; Mietus, J.E.; Goldberger, A.L.; Mantzoros, C.S. Diurnal and ultradian dynamics of serum adiponectin in healthy men: Comparison with leptin, circulating soluble leptin receptor, and cortisol patterns. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003, 88, 2838–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, M.; Rahmani-Nia, F.; Mohebbi, H. Cortisol Responses and Energy Expenditure atDifferent Times of Day in Obese Vs. Lean Men. World Journal of Sport Sciences 2012, 6, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillon, D.J.; Zheng, B.; Campbell, R.G.; Matthews, D.E. Effect of cortisol on energy expenditure and amino acid metabolism in humans. Am J Physiol. 1995, 268 (3 Pt 1), E501–E513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujovic, N.; Piron, M.J.; Qian, J.; Chellappa, S.L.; Nedeltcheva, A.; Barr, D.; et al. Late isocaloric eating increases hunger, decreases energy expenditure, and modifies metabolic pathways in adults with overweight and obesity. Cell Metab 2022, 34, 1486–1498.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowicz, D.; Barnea, M.; Wainstein, J.; Froy, O. Effects of caloric intake timing on insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism in lean women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013, 125, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowicz, D.; Landau, Z.; Tsameret, S.; Wainstein, J.; Raz, I.; Ahren, B.; et al. Reduction in Glycated Hemoglobin and Daily Insulin Dose Alongside Circadian Clock Upregulation in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Consuming a Three-Meal Diet: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 2171–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Minguez, J.; Gomez-Abellan, P.; Garaulet, M. Timing of Breakfast, Lunch, and Dinner. Effects on Obesity and Metabolic Risk. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoogian, E.N.C.; Chow, L.S.; Taub, P.R.; Laferrere, B.; Panda, S. Time-restricted Eating for the Prevention and Management of Metabolic Diseases. Endocr Rev. 2022, 43, 405–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Hutchison, A.T.; Heilbronn, L.K. Carbohydrate intake and circadian synchronicity in the regulation of glucose homeostasis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2021, 24, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, D.J.; Mode, W.J.A.; Slater, T. Optimising intermittent fasting: Evaluating the behavioural and metabolic effects of extended morning and evening fasting. Nutr Bull 2020, 45, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.P.; Ellacott, K.L.J.; Chen, H.; McGuinness, O.P.; Johnson, C.H. Time-optimized feeding is beneficial without enforced fasting. Open Biol 2021, 11, 210183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowicz, D.; Wainstein, J.; Landau, Z.; Raz, I.; Ahren, B.; Chapnik, N.; et al. Influences of Breakfast on Clock Gene Expression and Postprandial Glycemia in Healthy Individuals and Individuals With Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 1573–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timlin, M.T.; Pereira, M.A. Breakfast frequency and quality in the etiology of adult obesity and chronic diseases. Nutr Rev 2007, 65 (6 Pt 1), 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievert, K.; Hussain, S.M.; Page, M.J.; Wang, Y.; Hughes, H.J.; Malek, M.; et al. Effect of breakfast on weight and energy intake: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2019, 364, l42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilberter, T.; Zilberter, E.Y. Breakfast: To skip or not to skip? Front Public Health 2014, 2, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, C.J.; Kaur, B.; Quek, R.Y.C. Chrononutrition in the management of diabetes. Nutr Diabetes 2020, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicherski, J.; Schlesinger, S.; Fischer, F. Association between Breakfast Skipping and Body Weight-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Longitudinal Studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, H.A.; Zibellini, J.; Harris, R.A.; Seimon, R.V.; Sainsbury, A. Effect of Ramadan Fasting on Weight and Body Composition in Healthy Non-Athlete Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabuena, T.J.; Boege, H.L.; Bhatti, M.Z.; Whyte, K.J.; Cheng, B.; St-Onge, M.P. Delaying mealtimes reduces fat oxidation: A randomized, crossover, controlled feeding study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2022, 30, 2386–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, K.C.; Hopkins, C.M.; Ruggieri, M.; Spaeth, A.M.; Ahima, R.S.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Prolonged, Controlled Daytime versus Delayed Eating Impacts Weight and Metabolism. Curr Biol 2021, 31, 650–657.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, H.S.; Merino, J.; Lane, J.M.; Song, Y.; Smith, C.E.; Tanaka, T.; et al. Genome-wide association study of breakfast skipping links clock regulation with food timing. Am J Clin Nutr 2019, 110, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEWONTINRC. The analysis of variance and the analysis of causes. International Journal of Epidemiology 2006, 35, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, K.; Suwa, K. Association of hyperglycemia in a general Japanese population with late-night-dinner eating alone, but not breakfast skipping alone. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2015, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, M.; Nakamura, K.; Ogata, H.; Miyashita, A.; Nagasaka, S.; Omi, N.; et al. Acute effect of late evening meal on diurnal variation of blood glucose and energy metabolism. Obesity research & clinical practice 2011, 5, e169–e266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, R.; Hashimoto, Y.; Ushigome, E.; Miki, A.; Okamura, T.; Matsugasumi, M.; et al. Late-night-dinner is associated with poor glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes: The KAMOGAWA-DM cohort study. Endocr J 2018, 65, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, G.K.W.; Huggins, C.E.; Ware, R.S.; Bonham, M.P. Time of day difference in postprandial glucose and insulin responses: Systematic review and meta-analysis of acute postprandial studies. Chronobiol Int 2020, 37, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, K.; Song, Y. Associations of Meal Timing and Frequency with Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome among Korean Adults. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajiyama, S.; Imai, S.; Hashimoto, Y.; Yamane, C.; Miyawaki, T.; Matsumoto, S.; et al. Divided consumption of late-night-dinner improves glucose excursions in young healthy women: A randomized cross-over clinical trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018, 136, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Brereton, N.; Schweitzer, A.; Cotter, M.; Duan, D.; Borsheim, E.; et al. Metabolic Effects of Late Dinner in Healthy Volunteers-A Randomized Crossover Clinical Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020, 105, 2789–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, M.D.; Zhao, L.; Turner-McGrievy, G.M.; Ortaglia, A. Associations between Fasting Duration, Timing of First and Last Meal, and Cardiometabolic Endpoints in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittendrigh, C.S.; Daan, S. A functional analysis of circadian pacemakers in nocturnal rodents. Journal of comparative physiology 1976, 106, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illnerová, H.; Vaněček, J. Two-oscillator structure of the pacemaker controlling the circadian rhythm of N-acetyltransferase in the rat pineal gland. Journal of Comparative Physiology 1982, 145, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehr, T.A.; Aeschbach, D.; Duncan, W.C., Jr. Evidence for a biological dawn and dusk in the human circadian timing system. J Physiol 2001, 535 Pt 3, 937–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buijs, R.M.; Wortel, J.; Van Heerikhuize, J.J.; Feenstra, M.G.; Ter Horst, G.J.; Romijn, H.J.; et al. Anatomical and functional demonstration of a multisynaptic suprachiasmatic nucleus adrenal (cortex) pathway. Eur J Neurosci 1999, 11, 1535–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnocchi, D.; Bruscalupi, G. Circadian Rhythms and Hormonal Homeostasis: Pathophysiological Implications. Biology (Basel) 2017, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, H.C.; Wood, S.A.; Kershaw, Y.M.; Bate, E.; Lightman, S.L. Diurnal variation in the responsiveness of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis of the male rat to noise stress. J Neuroendocrinol 2006, 18, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quabbe, H.J.; Gregor, M.; Bumke-Vogt, C.; Hardel, C. Pattern of plasma cortisol during the 24-hour sleep/wake cycle in the rhesus monkey. Endocrinology 1982, 110, 1641–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyanagi, S.; Okazawa, S.; Kuramoto, Y.; Ushijima, K.; Shimeno, H.; Soeda, S.; et al. Chronic treatment with prednisolone represses the circadian oscillation of clock gene expression in mouse peripheral tissues. Mol Endocrinol 2006, 20, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezuk, P.; Mohawk, J.A.; Wang, L.A.; Menaker, M. Glucocorticoids as entraining signals for peripheral circadian oscillators. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 4775–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Minh, N.; Damiola, F.; Tronche, F.; Schutz, G.; Schibler, U. Glucocorticoid hormones inhibit food-induced phase-shifting of peripheral circadian oscillators. EMBO J 2001, 20, 7128–7136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, A.; Bouchareb, B.; Touitou, Y. Ramadan fasting alters endocrine and neuroendocrine circadian patterns. Meal-time as a synchronizer in humans? Life Sci 2001, 68, 1607–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, A.; von Hagen, J. Circadian Oscillations in Skin and Their Interconnection with the Cycle of Life. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino-Segura, M.; Hidalgo, A. Circadian immune circuits. J Exp Med 2021, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, A.M.; Bellet, M.M.; Sassone-Corsi, P.; O’Neill, L.A. Circadian clock proteins and immunity. Immunity. 2014, 40, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolbe, I.; Dumbell, R.; Oster, H. Circadian Clocks and the Interaction between Stress Axis and Adipose Function. Int J Endocrinol 2015, 2015, 693204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nader, N.; Chrousos, G.P.; Kino, T. Interactions of the circadian CLOCK system and the HPA axis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2010, 21, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratman, D.; Vanden Berghe, W.; Dejager, L.; Libert, C.; Tavernier, J.; Beck, I.M.; et al. How glucocorticoid receptors modulate the activity of other transcription factors: A scope beyond tethering. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2013, 380, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segall, L.A.; Milet, A.; Tronche, F.; Amir, S. Brain glucocorticoid receptors are necessary for the rhythmic expression of the clock protein, PERIOD2, in the central extended amygdala in mice. Neurosci Lett 2009, 457, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Nakahata, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Yoshida, M.; Soma, H.; Shinohara, K.; et al. Acute physical stress elevates mouse period1 mRNA expression in mouse peripheral tissues via a glucocorticoid-responsive element. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 42036–42043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Abellan, P.; Diez-Noguera, A.; Madrid, J.A.; Lujan, J.A.; Ordovas, J.M.; Garaulet, M. Glucocorticoids affect 24 h clock genes expression in human adipose tissue explant cultures. PLoS ONE. 2012, 7, e50435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stimson, R.H.; Mohd-Shukri, N.A.; Bolton, J.L.; Andrew, R.; Reynolds, R.M.; Walker, B.R. The postprandial rise in plasma cortisol in men is mediated by macronutrient-specific stimulation of adrenal and extra-adrenal cortisol production. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014, 99, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindikoglu, A.L.; Park, J.; Opekun, A.R.; Abdulsada, M.M.; Wilhelm, Z.R.; Jalal, P.K.; et al. Dawn-to-dusk dry fasting induces anti-atherosclerotic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumorigenic proteome in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Metabol Open 2022, 16, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordjman, S.; Chokron, S.; Delorme, R.; Charrier, A.; Bellissant, E.; Jaafari, N.; et al. Melatonin: Pharmacology, Functions and Therapeutic Benefits. Curr Neuropharmacol 2017, 15, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; BaHammam, A.S.; Ojike, N.I.; Akinseye, O.A.; Kendzerska, T.; Buttoo, K.; et al. Melatonin and Human Cardiovascular Disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2017, 22, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; BaHammam, A.S.; Brown, G.M.; Spence, D.W.; Bharti, V.K.; Kaur, C.; et al. Melatonin antioxidative defense: Therapeutical implications for aging and neurodegenerative processes. Neurotox Res 2013, 23, 267–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Kimpinski, K. Role of melatonin in blood pressure regulation: An adjunct anti-hypertensive agent. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2018, 45, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imenshahidi, M.; Karimi, G.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Effects of melatonin on cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic syndrome: A comprehensive review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2020, 393, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipolla-Neto, J.; Amaral, F.G.; Afeche, S.C.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin, energy metabolism, and obesity: A review. J Pineal Res 2014, 56, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Sastre, P.; Scheer, F.A.; Gomez-Abellan, P.; Madrid, J.A.; Garaulet, M. Acute melatonin administration in humans impairs glucose tolerance in both the morning and evening. Sleep 2014, 37, 1715–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Minguez, J.; Saxena, R.; Bandin, C.; Scheer, F.A.; Garaulet, M. Late dinner impairs glucose tolerance in MTNR1B risk allele carriers: A randomized, cross-over study. Clin Nutr 2018, 37, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, V.; Reichert, C.F.; Maire, M.; Schmidt, C.; Schlangen, L.J.M.; Kolodyazhniy, V.; et al. Differential impact in young and older individuals of blue-enriched white light on circadian physiology and alertness during sustained wakefulness. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 7620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaulet, M.; Lopez-Minguez, J.; Dashti, H.S.; Vetter, C.; Hernandez-Martinez, A.M.; Perez-Ayala, M.; et al. Interplay of Dinner Timing and MTNR1B Type 2 Diabetes Risk Variant on Glucose Tolerance and Insulin Secretion: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.M.; Olm, M.R.; Merrill, B.D.; Dahan, D.; Tripathi, S.; Spencer, S.P.; et al. Ultra-deep sequencing of Hadza hunter-gatherers recovers vanishing gut microbes. Cell 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotti, S.; Dinu, M.; Colombini, B.; Amedei, A.; Sofi, F. Circadian rhythms, gut microbiota, and diet: Possible implications for health. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deaver, J.A.; Eum, S.Y.; Toborek, M. Circadian Disruption Changes Gut Microbiome Taxa and Functional Gene Composition. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Bushman, F.D.; FitzGerald, G.A. Rhythmicity of the intestinal microbiota is regulated by gender and the host circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015, 112, 10479–10484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Effects of Diet and Exercise on Circadian Rhythm: Role of Gut Microbiota in Immune and Metabolic Systems. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaiss, C.A.; Zeevi, D.; Levy, M.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Suez, J.; Tengeler, A.C.; et al. Transkingdom control of microbiota diurnal oscillations promotes metabolic homeostasis. Cell 2014, 159, 514–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinpar, A.; Chaix, A.; Yooseph, S.; Panda, S. Diet and feeding pattern affect the diurnal dynamics of the gut microbiome. Cell Metab 2014, 20, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellappa, S.L.; Engen, P.A.; Naqib, A.; Qian, J.; Vujovic, N.; Rahman, N.; et al. Proof-of-principle demonstration of endogenous circadian system and circadian misalignment effects on human oral microbiota. FASEB J 2022, 36, e22043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, F.; Osaili, T.; Obaid, R.S.; Naja, F.; Radwan, H.; Cheikh Ismail, L.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Time-Restricted Feeding/Eating: A Targeted Biomarker and Approach in Precision Nutrition. Nutrients 2023, 15, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonken, L.K.; Workman, J.L.; Walton, J.C.; Weil, Z.M.; Morris, J.S.; Haim, A.; et al. Light at night increases body mass by shifting the time of food intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010, 107, 18664–18669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, J.L.; Thompson, S.V.; Holscher, H.D. Complex interactions of circadian rhythms, eating behaviors, and the gastrointestinal microbiota and their potential impact on health. Nutr Rev 2017, 75, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.; Wu, L.; Jiang, J.; Yang, T.; Wang, Z.; Ma, L.; et al. Late-Night Eating-Induced Physiological Dysregulation and Circadian Misalignment Are Accompanied by Microbial Dysbiosis. Mol Nutr Food Res 2019, 63, e1900867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellikci-Koyu, E.; Sarer-Yurekli, B.P.; Akyon, Y.; Ozgen, A.G.; Brinkmann, A.; Nitsche, A.; et al. Associations of sleep quality and night eating behaviour with gut microbiome composition in adults with metabolic syndrome. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2021, 80, E58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carasso, S.; Fishman, B.; Lask, L.S.; Shochat, T.; Geva-Zatorsky, N.; Tauber, E. Metagenomic analysis reveals the signature of gut microbiota associated with human chronotypes. FASEB J 2021, 35, e22011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, Z.; Bishehsari, F.; Masoudi, S.; Hekmatdoost, A.; Stewart, D.A.; Eghtesad, S.; et al. Association between Sleeping Patterns and Mealtime with Gut Microbiome: A Pilot Study. Arch Iran Med 2022, 25, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansu Baidoo, V.; Knutson, K.L. Associations between circadian disruption and cardiometabolic disease risk: A review. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2023, 31, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravussin, E.; Beyl, R.A.; Poggiogalle, E.; Hsia, D.S.; Peterson, C.M. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Reduces Appetite and Increases Fat Oxidation But Does Not Affect Energy Expenditure in Humans. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2019, 27, 1244–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.J.; Manoogian, E.N.C.; Zadourian, A.; Lo, H.; Fakhouri, S.; Shoghi, A.; et al. Ten-Hour Time-Restricted Eating Reduces Weight, Blood Pressure, and Atherogenic Lipids in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome. Cell Metab 2020, 31, 92–104.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, S.G.; Boyd, P.; Bailey, C.P.; Shams-White, M.M.; Agurs-Collins, T.; Hall, K.; et al. Perspective: Time-Restricted Eating Compared with Caloric Restriction: Potential Facilitators and Barriers of Long-Term Weight Loss Maintenance. Adv Nutr. 2021, 12, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welton, S.; Minty, R.; O’Driscoll, T.; Willms, H.; Poirier, D.; Madden, S.; et al. Intermittent fasting and weight loss: Systematic review. Can Fam Physician 2020, 66, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, D.A.; Wu, N.; Rohdin-Bibby, L.; Moore, A.H.; Kelly, N.; En Liu, Y.; et al. Effects of Time-Restricted Eating on Weight Loss and Other Metabolic Parameters in Women and Men With Overweight and Obesity:The TREAT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020, 180, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors (year) | Study design | Main results | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nakamura K. et al. (2021) [109] | A Randomized Cross-Over Trial: To assess the effect of the early evening meal on 24-h blood glucose levels and postprandial lipid metabolism in healthy adults. Twelve participants (2 males and 10 females) participated in a 3-day randomized cross-over study: eating a late dinner (at 21:00) or an early dinner (at 18:00), monitoring blood glucose levels by continuous blood glucose measuring device, metabolic measurements by indirect calorimetry method on the morning of day 3. | Significant differences between the two groups were observed in mean 24-h blood glucose levels on day 2 (p = 0.03). There was a significant decrease in the postprandial respiratory quotient 30 min and 60 min after breakfast on day 3 in the early dinner group compared with the late dinner group (p < 0.05). | Even a small difference 3 h, eating dinner early (at 18:00) has a positive effect on blood glucose level fluctuation and substrate oxidation compared with eating dinner late (at 21:00). No of the subjects is very small studied acute effects. |

| Xie Z. et al. (2022) [113] | Randomized controlled trial: To compare the effects of the two TRF regimens (early and midday) in healthy individuals without obesity. Ninety participants were randomized to eTRF (n=30), mTRF (n=30), or control groups (n=30). Eighty-two participants completed the entire five-week trial and were analyzed (28 in eTRF, 26 in mTRF, 28 in control groups). The primary outcome was the change in insulin resistance. | eTRF was more effective than mTRF at improving insulin sensitivity; eTRF, but not mTRF, improved fasting glucose, reduced total body mass and adiposity, ameliorated inflammation, and increased gut microbial diversity. |

Demonstrates a positive effect of meal timings (from early to midday) on metabolism during TRF regimen, although the study had multiple level biases (participant selection meal plan etc.). |

| Bo S. et al. (2015) [105] | A randomized cross-over study: To assess food-induced thermogenesis in the morning and evening. Twenty subjects were enrolled and randomly received the same standard meal in the morning and, 7 days after, in the evening, or vice versa. A 30-min basal, a further 60-min and 120-min calorimetry was performed after the beginning of the meal. Blood samples were drawn every 30-min for 180-min. General linear models, adjusted for period and carry-over, were used to evaluate the ‘morning effect’, that is, the difference of morning delta (after-meal minus fasting values) minus evening delta (after-meal minus fasting values) of the variables. | Fasting resting metabolic rate (RMR) did not change from morning to evening; after-meal RMR values were significantly higher after the morning meal (1916; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1792, 2041 vs. 1756; 1648, 1863 kcal; P<0.001). RMR was significantly increased after the morning meal (90.5; 95% CI = 40.4, 140.6 kcal; P<0.001), whereas differences in areas-under-the curve for glucose (−1800; − 2564, − 1036 mg /dlx h, P<0.001), log-insulin (−0.19; − 0.30, − 0.07 μUml /h; P = 0.001) and fatty free acid concentrations (−16.1; − 30.0, − 2.09 mmol/ l xh; P = 0.024) were significantly lower. Delayed and larger increases in glucose and insulin concentrations were found after the evening meals. | The same meal consumed in the evening determined a lower RMR, and increased glycemic/insulinemic responses, suggesting circadian variations in the energy expenditure and metabolic pattern of healthy individuals. Conditions were experimental in terms of food selection and interval. |

| Bandin C. et al. (2015 [104] | A randomized, cross-over trial: Thirty-two women completed two randomized, cross-over protocols: one protocol (P1) includes an assessment of resting energy expenditure (indirect-calorimetry) and glucose tolerance (mixed-meal test) (n = 10), and the other (P2) includes circadian-related measurements based on profiles in salivary cortisol and Wrist temp. (T wrist) (n = 22). In each protocol, participants were provided with standardized meals during the two meal intervention weeks and were studied under two lunch-eating conditions: Early Eating (EE; lunch at 01:00 pm) and Late Eating (LE; lunch at 04:30 pm). | LE, as compared with EE, resulted in decreased pre-meal resting-energy expenditure (P = 0.048), a lower pre-meal protein-corrected respiratory quotient (CRQ) and a changed post-meal profile of CRQ (P = 0.019). These changes reflected a significantly lower pre-meal utilization of carbohydrates in LE versus EE (P = 0.006). LE also increased glucose area under the curve above baseline by 46%, demonstrating decreased glucose tolerance (P = 0.002). Changes in the daily profile of cortisol and T wrist were also found with LE blunting the cortisol profile, with lower morning and afternoon values, and suppressing the postprandial. T wrist peak (P<0.05). |

Eating late is associated with decreased resting-energy expenditure, decreased fasting carbohydrate oxidation, decreased glucose tolerance, blunted daily profile in free cortisol concentrations, and decreased thermal effect of food on T wrist. These results may be implicated in the differential effects of meal timing on metabolic health. |

| Manoogian ENC. et al. (2022) [107] | A randomized control trial: It included 137 firefighters who work 24-h shifts (23-59 years old, 9% female), 12 weeks of 10-h time-restricted eating (TRE) was feasible, with TRE participants decreasing their eating window (baseline, mean 02:13 pm, 95% CI 13.78-14.47 h; intervention, 11:13 am, 95% CI 10:73-11:54 h, p = 3.29E-17) | Compared to the standard of care (SOC) arm, TRE significantly decreased VLDL particle size. In participants with elevated cardiometabolic risks at baseline, there were significant reductions in TRE compared to SOC in glycated hemoglobin A1C and diastolic blood pressure | 10-h time-restricted eating is feasible for shift workers on a 24-h schedule. TRE improved very low-density lipoprotein size and quality of life measures. TRE decreased HbA1c and blood pressure for participants with cardiometabolic risk. A consistent 10-h eating window (TRE) had no adverse effects. However, it had a skewed gender ratio and heterogenous baseline health factors. |

| Qian J. et al. (2018) [111] | Randomized, cross-over design trial: To determine the separate and relative impacts of the circadian system, behavioural/environmental cycles, and their interaction (i.e., circadian misalignment) on insulin sensitivity and β-cell function, the minimal oral model was used to quantitatively assess the major determinants of glucose control in 14 healthy adults using a randomized, cross-over design with two 8-day laboratory protocols. Both protocols involved 3 baseline inpatient days with habitual sleep/wake cycles, followed by 4 inpatient days with the same nocturnal bedtime (circadian alignment) or with 12-hour inverted behavioral/environmental cycles (circadian misalignment) | Data showed that the circadian phase and circadian misalignment affect glucose tolerance through different mechanisms. While the circadian system reduces glucose tolerance in the biological evening compared to the biological morning mainly by decreasing both dynamic and static β-cell responsivity, circadian misalignment reduced glucose tolerance mainly by lowering insulin sensitivity, not by affecting β-cell function. | Results revealed that the endogenous circadian system and circadian misalignment, after controlling for behavioral cycle influences, have independent and differential impacts on insulin sensitivity and β-cell function in healthy adults. |

| Collado MC. et al. (2018) [106] | A randomized, cross-over study: It recruited 10 healthy normal-weight young women to test the effect of the timing of food intake on the human microbiota in the saliva and fecal samples to determine whether eating late alters the daily rhythms of human salivary microbiota; the researchers interrogated salivary microbiota in samples obtained at 4 specific time points over 24 h, to achieve a better understanding of the relationship between food timing and metabolic alterations in humans | A significant diurnal rhythm in salivary diversity and relative bacterial abundance (i.e., TM7 and Fusobacteria) across both early and late eating conditions. Meal timing affected diurnal rhythms in a diversity of salivary microbiota toward an inverted rhythm between the eating conditions, and eating late increased the number of putative pro-inflammatory taxa, showing a diurnal rhythm in the saliva | The impact of the timing of food intake on human salivary microbiota. Eating the main meal late inverts the daily rhythm of salivary microbiota diversity, which may have a deleterious effect on the metabolism of the host. |

| Pizinger T. et al. (2018) [110] | Randomized control trial: It aimed to test the independent and interactive effects of sleep and mealtimes on insulin sensitivity (Si) in overweight adults, Six participants were enrolled (4 men, 2 women; (1 did not complete). Participants underwent a 4-phase randomized cross-over inpatient study differing in sleep times: normal (Ns: mid-night-08:00 am) or late (Ls: 03:30 am -11:30 am); and in meal times: normal (Nm: 1, 5, 11, and 12.5 hours after awakening) or late (Lm: 4.5, 8.5, 14.5, and 16 hours after awakening). An insulin-modified frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test at scheduled breakfast time, and a meal tolerance test, at scheduled lunch time, were performed to assess Si after 3 days in each condition. | Meal time influenced concentrations of glucose (P = 0.012) and insulin (P = 0.069) during the overnight hours Average cortisol concentrations between 2200 and 0700 h tended to be affected by mealtime. Melatonin concentrations from the overnight sampling period showed no effect on mealtime. |

Mealtimes may be relevant for health. |

| Morris C.J et al. (2016) [108] | A randomized cross-over study: The study aimed to test the hypothesis that the endogenous circadian system and circadian misalignment separately affect glucose tolerance in shift workers, both independently from behavioral cycle effects; 9 healthy. The intervention included simulated night work comprised of 12-hour inverted behavioral and environmental cycles (circadian misalignment) or simulated day work (circadian alignment). Postprandial glucose and insulin responses to identical meals given at 8:00 am and 8:00 pm in both protocols | Circadian misalignment increased postprandial glucose by 5.6%, independent of behavioral and circadian effects (P =.0042). | Internal circadian time affects glucose tolerance in shift workers. Separately, circadian misalignment reduces glucose tolerance in shift workers, providing a mechanism to help explain the increased diabetes risk in shift workers. |

| Sharma A. et al. (2017) [112] | Randomized control trial: It aimed to determine the effect of rotational shift work on glucose metabolism. 12 healthy nurses performing rotational shift work using a randomized cross-over study design, underwent an isotope-labeled mixed meal test during a simulated day shift and a simulated night shift, enabling simultaneous measurement of glucose flux and beta cell function using the oral minimal model. | The postprandial glycaemic excursion was higher during the night shift (381±33 vs. 580±48 mmol/l per 5 h, p<0.01). The time to peak insulin, C-peptide, and nadir glucagon suppression in response to meal ingestion was also delayed during the night shift. While insulin action did not differ between study days, the beta cell responsivity to glucose (59±5 vs. 44±4 × 10-9 min-1; p<0.001) and disposition index were decreased during the night shift. | Impaired beta cell function during the night shift may result from normal circadian variation, the effect of rotational shift-work or a combination of both. As a consequence, higher postprandial glucose concentrations are observed during the night shift. |

| Vujovic N. et al. (2022) [126] | A randomized, controlled, cross-over trial with 18 subjects to determine the effects of late versus early eating while rigorously controlling for nutrient intake, physical activity, sleep, and light exposure. The parameters measured were subjective (hunger) and objective (hormones related to metabolism) | Late eating increased hunger (p < 0.0001) and altered appetite-regulating hormones, increasing waketime and 24-h ghrelin leptin ratio (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.006, respectively). Furthermore, late eating decreased waketime energy expenditure (p = 0.002) and 24-h core body temperature (p = 0.019) | These findings show converging mechanisms by which late eating may result in positive energy balance and increased obesity risk. |

| Jamshed H et al. (2019) [71] | This study employed a 4-day randomized crossover design to investigate the impact of time-restricted feeding (TRF) on gene expression, circulating hormones, and diurnal patterns in cardiometabolic risk factors. Eleven overweight adults participated in the study, following two different eating schedules: early TRF (eTRF) from 8 am to 2 pm and a control schedule from 8 am to 8 pm. Continuous glucose monitoring was conducted, and blood samples were collected to assess various factors. | Compared to the control schedule, eTRF led to a significant decrease in mean 24-hour glucose levels by 4 ± 1 mg/dl (p = 0.0003) and glycemic excursions by 12 ± 3 mg/dl (p = 0.001). In the morning, before breakfast, eTRF increased ketones, cholesterol, and the expression of the stress response and aging gene SIRT1, as well as the autophagy gene LC3A (all p < 0.04). In the evening, eTRF showed a tendency to increase brain-derived neurotropic factor (BNDF; p = 0.10) and significantly increased the expression of MTOR (p = 0.007), a key protein involved in nutrient sensing and cell growth. Moreover, eTRF resulted in altered diurnal patterns in cortisol levels and the expression of several circadian clock genes (p < 0.05). | The findings of this study indicate that eTRF improves 24-hour glucose levels, modifies lipid metabolism and circadian clock gene expression, and may enhance autophagy while potentially exerting anti-aging effects in humans. |

| Lowe DA. et a. (2020) [205] | This 12-week randomized clinical trial aimed to investigate the impact of 16:8-hour time-restricted eating (TRE) on weight loss and metabolic risk markers. Participants (n=116) were divided into two groups: the consistent meal timing (CMT) group, instructed to consume three structured meals per day, and the TRE group, instructed to eat ad libitum from 12:00 pm until 8:00 pm and observe a complete caloric intake abstention from 8:00 pm until 12:00 pm the following day. The study was conducted using a custom mobile study application, with in-person testing for a subset of 50 participants located near San Francisco, California. | The TRE group showed a significant decrease in weight (-0.94 kg; 95% CI, -1.68 to -0.20; P = 0.01). However, there was no significant change in the CMT group (-0.68 kg; 95% CI, -1.41 to 0.05, P = 0.07) or between the two groups (-0.26 kg; 95% CI, -1.30 to 0.78; P = 0.63). In the in-person cohort (n = 25 TRE, n = 25 CMT), the TRE group exhibited a significant within-group decrease in weight (-1.70 kg; 95% CI, -2.56 to -0.83; P < 0.001). Additionally, the two groups had a significant difference in the appendicular lean mass index (-0.16 kg/m2; 95% CI, -0.27 to -0.05; P = 0.005). However, no significant changes were observed in any of the other secondary outcomes within or between the groups. Estimated energy intake did not differ significantly between the groups. | These findings suggest that the effectiveness of time-restricted feeding for weight loss may depend on factors such as meal timing. Specifically, skipping the early morning meal may not lead to weight loss benefits. |

| Hutchison AT, et a. (2019) [114] | This study employed a randomized controlled trial design to assess the impact of 9-hour time-restricted feeding (TRF) on glucose tolerance in men at risk for type 2 diabetes. Fifteen male participants with an average age of 55 ± 3 years and a BMI of 33.9 ± 0.8 kg/m2 were enrolled in the study. The participants wore a continuous glucose monitor for 7 days during the baseline assessment and two 7-day TRF conditions. They were randomly assigned to either early TRF (TRFe) from 8 am to 5 pm or delayed TRF (TRFd) from 12 pm to 9 pm, with a 2-week washout phase between the two conditions. Glucose, insulin, triglycerides, nonesterified fatty acids, and gastrointestinal hormone levels were measured and analyzed based on incremental areas under the curve following a standard meal at specific time points. | The results demonstrated that both TRFe and TRFd improved glucose tolerance, as evidenced by a reduction in glucose incremental area under the curve (P = 0.001) and fasting triglycerides (P = 0.003) on day 7 compared to day 0. However, no significant interactions between mealtime and TRF existed for any of the variables examined. TRF did not significantly affect fasting and postprandial insulin, nonesterified fatty acids, or gastrointestinal hormone levels. As measured by continuous glucose monitoring, mean fasting glucose was lower in TRFe (P = 0.02) but not in TRFd (P = 0.17) compared to baseline, with no significant difference observed between the two TRF conditions. | This study’s findings suggest that early and delayed time-restricted feeding (TRFe and TRFd) improve glycemic responses to a test meal in men at risk for type 2 diabetes. Although only TRFe resulted in a lower mean fasting glucose level, reflecting better results with early feeding time. |

| Jones R, et al. (2020) [115] | This study employed a randomized controlled trial to investigate the chronic effects of early time-restricted feeding (eTRF) compared to an energy-matched control on insulin and anabolic sensitivity in healthy males. Sixteen participants with an average age of 23 ± 1 years and a BMI of 24.0 ± 0.6 kg·m-2 were assigned to two groups: eTRF (n = 8) and control/caloric restriction (CON:CR; n = 8). The eTRF group followed the eTRF diet for 2 weeks, while the CON:CR group underwent a calorie-matched control diet after the eTRF intervention. During eTRF, daily energy intake was restricted to the period between 08:00 and 16:00, which extended the overnight fasting period by approximately 5 hours. Metabolic responses were assessed before and after the interventions, following a 12-hour overnight fast, using a carbohydrate/protein drink. | The results showed that eTRF improved whole-body insulin sensitivity compared to CON:CR, with a between-group difference of 1.89 (95% CI: 0.18, 3.60; P = 0.03; η2p = 0.29). eTRF also enhanced skeletal muscle uptake of glucose (between-group difference: 4266 μmol·min-1·kg-1·180 min; 95% CI: 261, 8270; P = 0.04; η2p = 0.31) and branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) (between-group difference: 266 nmol·min-1·kg-1·180 min; 95% CI: 77, 455; P = 0.01; η2p = 0.44). The eTRF group experienced a reduction in energy intake (approximately 400 kcal·d-1) and weight loss (-1.04 ± 0.25 kg; P = 0.01), which was comparable to the weight loss observed in the CON:CR group (-1.24 ± 0.35 kg; P = 0.01). | Under free-living conditions, eTRF demonstrated improvements in whole-body insulin sensitivity and increased skeletal muscle glucose and BCAA uptake. These metabolic benefits were observed independent of weight loss and reflect chronic adaptations rather than the immediate effects of the last overnight fast, suggesting that eTRF can have positive effects on metabolic health. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).