Submitted:

27 June 2023

Posted:

27 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

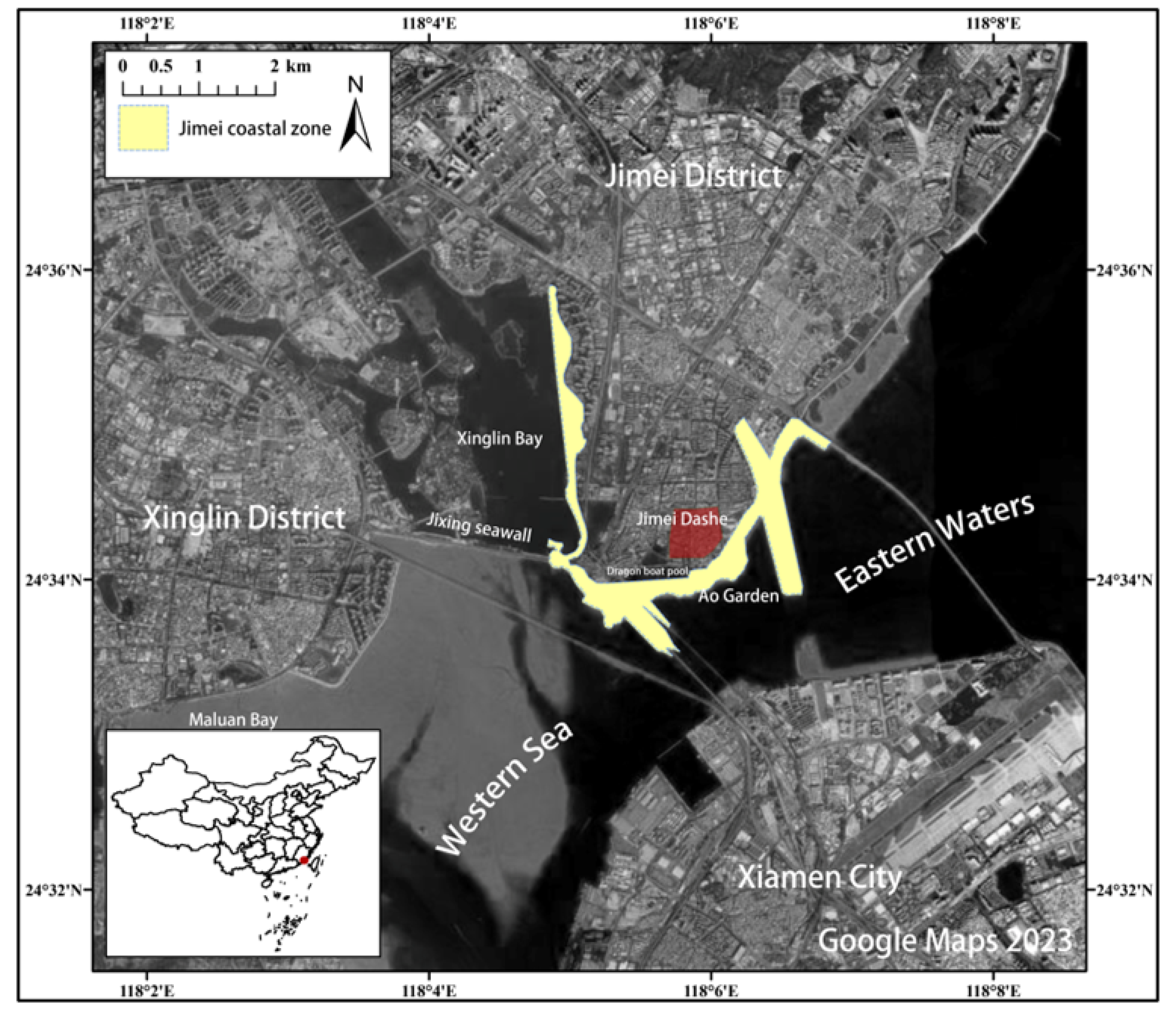

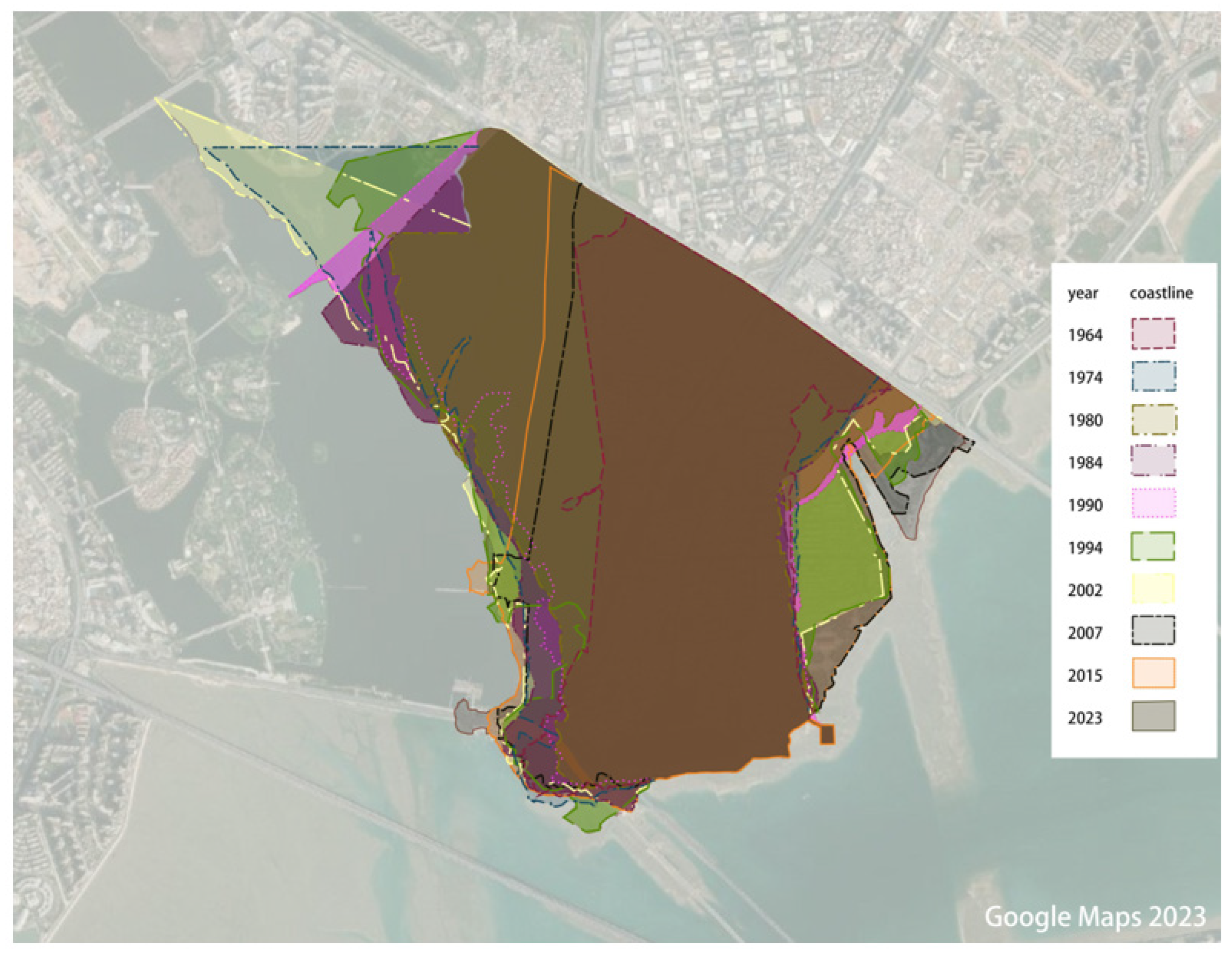

2.1. Study Area

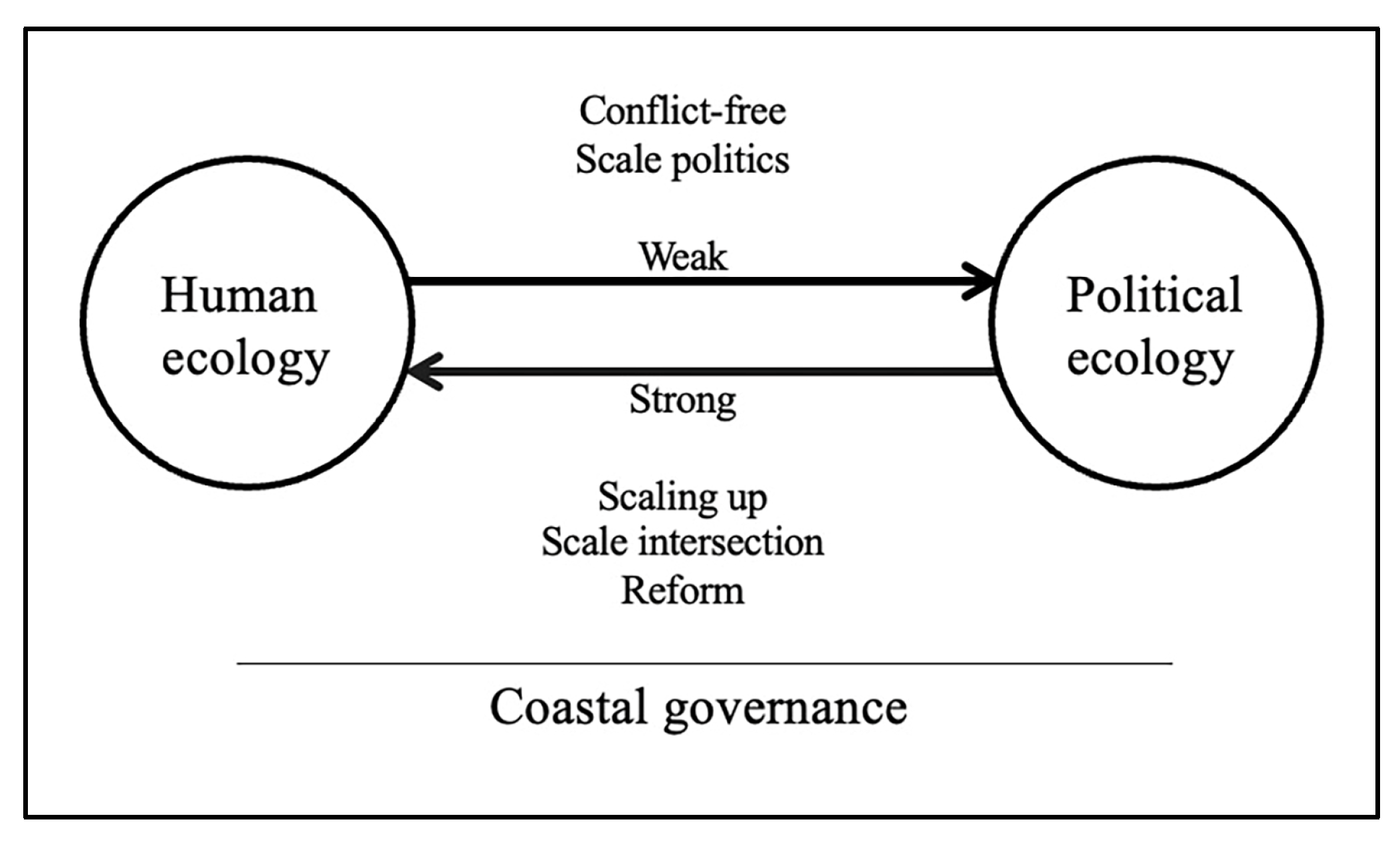

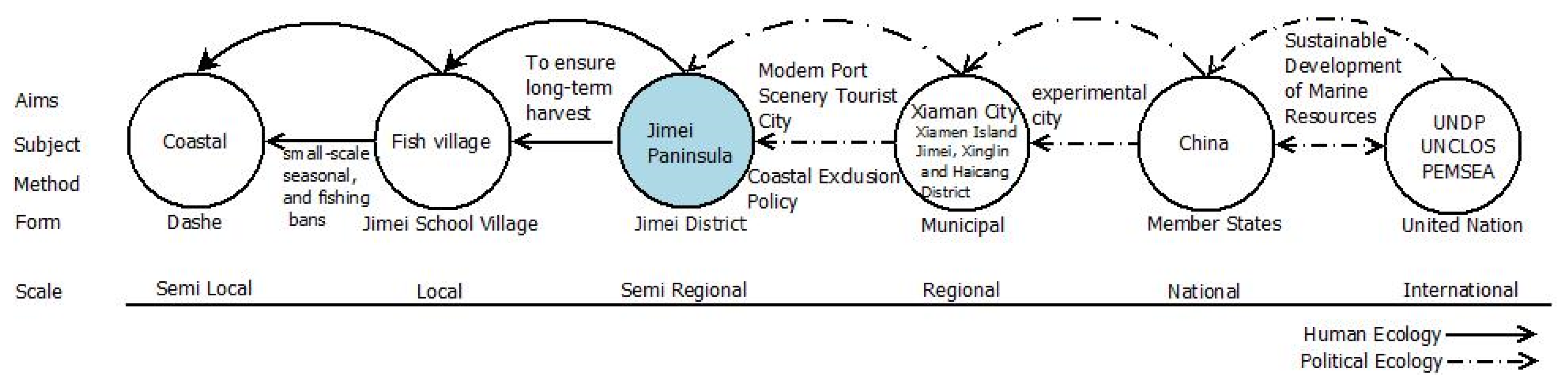

2.2. Study Framework and Method Design

2.3. Research materials

3. Results

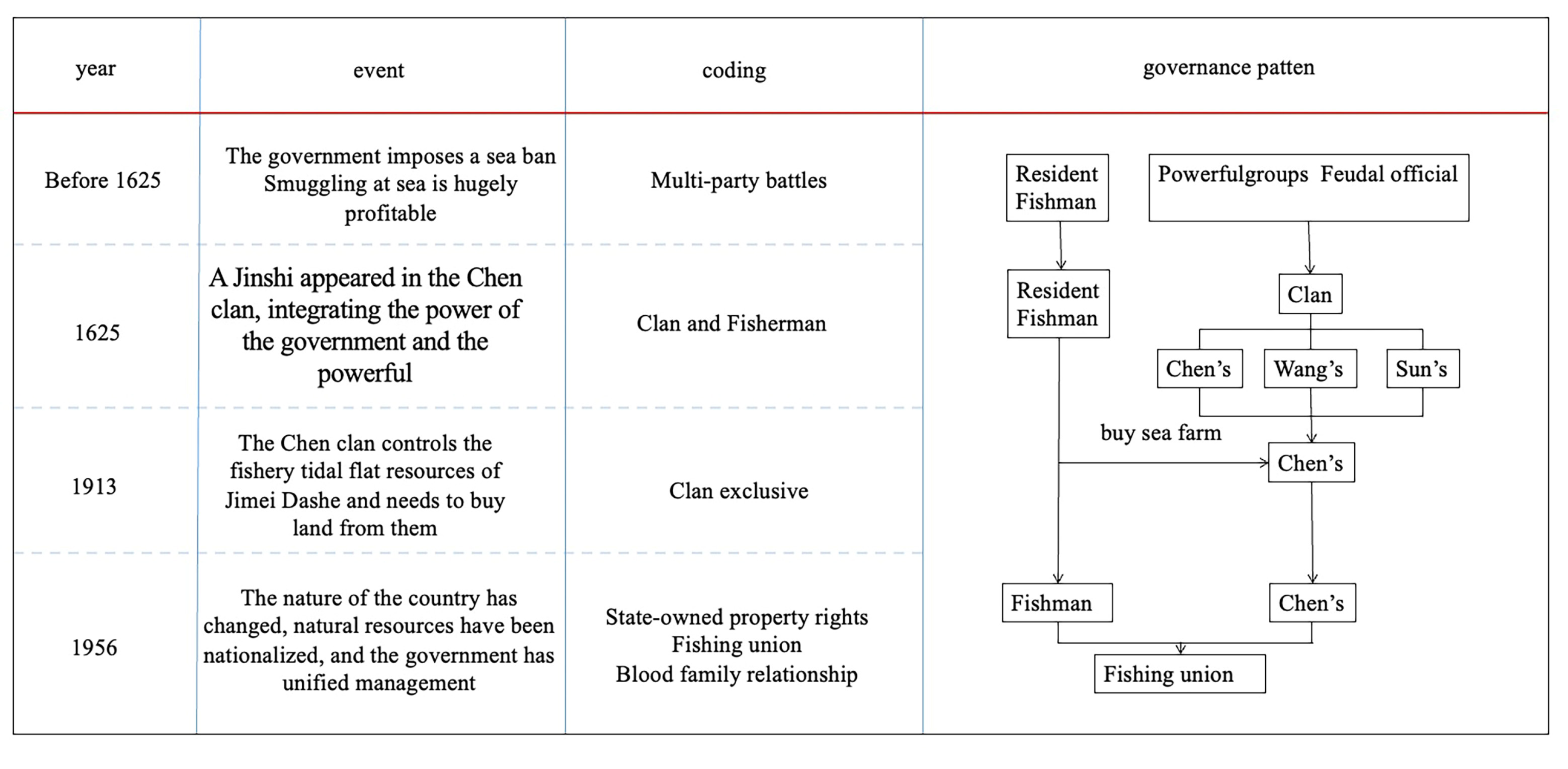

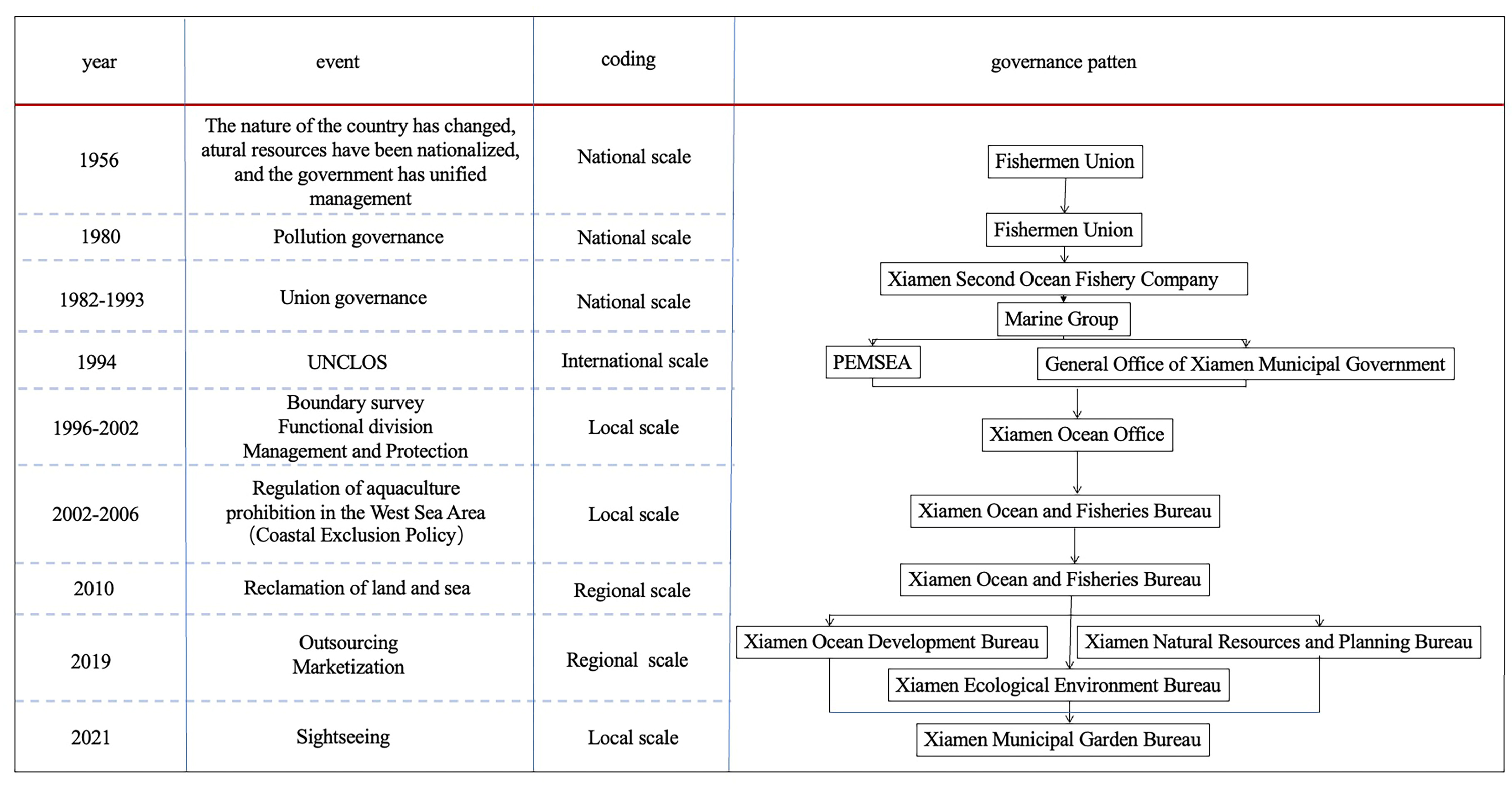

3.1. The changes in the governance of the coastal zone in Jimei Peninsula

3.2. The scale politics and functional shift in coastal zone governance

3.3. The effects of scale politics

4. Discussion

4.1. Economic evolutionBut the Human Ecology Declines.

4.2. Natural ecological degradation: Imbalance in governance

4.3. Marginalization of human ecology: Functional shift

4.4. Transformation of governance patterns

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campbell LM, Gray NJ, Fairbanks L, Silver JJ, Gruby RL, Dubik BA, et al. Global oceans governance: New and emerging issues. Annual review of environment and resources 2016, 41, 517-43. [CrossRef]

- Carothers, C. Fisheries privatization, social transitions, and well-being in Kodiak, Alaska. Marine Policy. 2015, 61, 313–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burggren WW, MB. Biology of the land crabs: an introduction. In: Burggren WW MB, editor. Biology of the Land Crabs Cambridge: Academic Press; 1988.

- Alexander, H. A preliminary assessment of the role of the terrestrial decapod crustaceans in the Aldabran ecosystem. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B,Biological Sciences, 1979; 286, 241–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd DJ, Green† PT, Lake PS. Invasional ‘meltdown’ on an oceanic island. Ecology Letters, 2003; 6, 812-7. [CrossRef]

- Hartnoll, R. Growth and molting. In: Burggren WW MB, editor. Biology of the Land Crabs Cambridge: Academic Press. 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Samaniego-Herrera A, Boudjelas S, Harper GA, Russell JC. Assessing the critical role that land crabs play in tropical island rodent eradications and ecological restoration. In: Veitch MNC, A.R. Martin, J.C. Russell and C.J. West, editor. Island invasives: scaling up to meet the challenge 62. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN; 2019.

- Brook S, Grant A, Bell D. Can land crabs be used as a rapid ecosystem evaluation tool? A test using distribution and abundance of several genera from the Seychelles. Acta Oecologica. 2009, 35(5), 711–9, PubMed PMID:S1146609X09000915.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun C-Z, Cao Q, Zou W. Assessment of marine economy resilience of coastal cities in Bohai Sea Ring Area based on entropy efficiency model. JOURNAL OF NINGBO UNIVERSITY ( NSEE )2020. p. 10-8.

- Huang L-H, Jiang Y, Lin c, Li T-W, Chen F, Wang W-Y. Research on the coupling coordination relationship between Xiamen Port development and coastal eco-nvironment evolution. Environmental Pollution and Prevention2020. p. 890-3,900.

- Bao J, Wu D-T. Space, Scale and System: A Geographical Study of China's Land and Sea Coordinated Development Strategy. Nanjing: Southeast University Press; 2016.

- Yu W-W. Research on Ecological Risk Assessment of Regional Strategic Decision-Making in Coastal Zone. Xiaman: University of Xiaman; 2012.

- Hartnoll RG, CP. A mass recruitment event in the land crab Gecarcinus ruricola (Linnaeus, 1758)(Brachyura: Grapsoidea: Gecarcinidae), and a description of the megalop. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2006, 146, 149–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J H, H R, H Y. Christmas crabs. 2 ed. Christmas Island: Christmas Island Natural History Association Christmas Island; 1990.

- Brown I, Fletcher WJ. The coconut crab: Aspects of the biology and ecology of Birgus latro in the Republic of Vanuatu. Canberra, Australia: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research; 1991.

- Ducrotoy J-P, Furukawa K. Integrated coastal management: Lessons learned to address new challenges. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2016, 102(2), 241-2. [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar MB, Ghani Aziz SABA. Integrated coastal zone management using the ecosystems approach, some perspectives in Malaysia. Ocean & Coastal Management. 2003, 46(5), 407-19. [CrossRef]

- Cooper JAG. Progress in Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) in Northern Ireland. Marine Policy. 2011, 35(6), 794-9. [CrossRef]

- Satoquo Seino, Kojima A, Hinata H, Magome Sn, Isob A. Multi-sectoral research on East China sea beach litter based on oceanographic methodology and local knowledge. Journal of Coastal Research. 2009, (56), 4.

- Wescott, G. Reforming coastal management to improve community participation and integration in Victoria, Australia. Coastal Management. 1998, 26(1), 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahuri R, Dutton IM. Integrated coastal and marine management enters a new era in Indonesia. Integrated Coastal Zone Management. 2000, 1(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Marroni EV, Asmus ML. Historical antecedents and local governance in the process of public policies building for coastal zone of Brazil. Ocean & Coastal Management. 2013, 76, 30-7. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, NJ. In political seas: engaging with political ecology in the ocean and coastal environment. Coastal Management. 2019, 47(1), 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, P. Political ecology : a critical introduction. second edition ed. UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2012.

- Silver, JJ. Weighing in on scale: synthesizing disciplinary approaches to scale in the context of building interdisciplinary resource management. Society and natural resources. 2008, 21(10), 921–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers C, Helgadóttir G, Carothers C. “Little kings”: community, change and conflict in Icelandic fisheries. Marit Stud, 2017; 16, 1, 10. [CrossRef]

- Stonich, SC. Political ecology of tourism. Annals of tourism research. 1998, 25(1), 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibade, I. Can a future city enhance urban resilience and sustainability? A political ecology analysis of Eko Atlantic city, Nigeria. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2017, 26, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 29. Donkersloot R, Menzies C. Place-based fishing livelihoods and the global ocean: the Irish pelagic fleet at home and abroad. Marit Stud, 2015; 14, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, LM. Implementation challenges of climate change adaptation initiatives in coastal lagoon communities in the Gulf of Mexico. Marit Stud. 2017, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, PA. Reconsidering ‘regional’political ecologies: toward a political ecology of the rural American West. Progress in human geography. 2003, 27(1), 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin X-H, Peng X, Li X-J. Research on the characteristics of my country's coastal zone economic development under the new situation. Marine Economy2019. p. 12-9.

- Wang L-B. Investigation of the Social and Cultural Changes of Sea Island Fishing Villages--A Case Study on Dayian Island Fishing Village. The Sixth Postgraduate Symposium of the School of Ethnology and Sociology, Minzu University of China. Beijing: Minzu University of China; 2012. p. 89-96.

- Dai Z-f, Zhang H-b, Zhou Q, Tian Y, Chen T, Tu C, et al. Occurrence of microplastics in the water column and sediment in an inland sea affected by intensive anthropogenic activities. Environmental Pollution. 2018, 242, 1557–65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang T, Hu M-H, Song L-L, Yu J, Liu R-J, Wang S-X, et al. Coastal zone use influences the spatial distribution of microplastics in Hangzhou Bay, China. Environmental Pollution, 2020; 266, 115137. [CrossRef]

- Bureau XOaF. Treading the Waves and Flying Songs: Oral Records of Key Figures in the Twenty Years of Comprehensive Management of the Coastal Zone in Xiamen from 1996 to 2016. Xiamen: Xiamen University Press; 2018.

- Islam, KS. Successful Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) Program Model of a Developing Country (Xiamen, China)-Implementation in Bangladesh Perspective [master]: Xiamen University; 2009.

- Zhong M-D. Research on Population Ecology of Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphin (Sousa Chinensis) in Xiamen Bay [硕士]: The Third Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources; 2021.

- Ma C, Liu Y, Zhuang Z-D, Xu C-y, Shen C-C, Tsai J-D. Analysis on the resource status and change reason of Branchiostoma balcheri in Xiamen Amphioxus Natural Reserve. Journal of Fisheries Research. 2022, 44(01), 44–51. [CrossRef]

- YOU T-F, Chen X-Y, Lin J-X, Ye Q-T. Investigation on nekton resources of spring in the west sea areas of Xiamen. Journal of Fisheries Research. 2016.

- Zimmerer, KS. Cultural ecology (and political ecology) in the ‘environmental borderlands’: exploring the expanded connectivities within geography. Progress in Human Geography. 2007, 31(2), 227–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerer, KS. Cultural ecology: at the interface with political ecology-the new geographies of environmental conservation and globalization. Progress in Human Geography. 2006, 30(1), 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun J-Q. Xiamen Jimei District Chronicle. Beijing, China: Zhonghua Bookstore; 2013.

- Committee CGESE. China Encyclopedia Geography-Xiamen Peninsula 2016. World Book Publishing Company, Nanfang Daily Publishing House 2016.

- Lung K-H. Urban Sociology Theory and Applications. Taipei,Taiwan: San Min Book; 1978. p. 102-15.

- Hawley, AH. Human Ecology-A Theoretical Essay. USA: The University Of Chicago Press; 1986. 8 p.

- Yu-Yan Zhang, Zhe Zou, Shu-Chen Tsai. From Fishing Village to Jimei School Village: Spatial Evolution of Human Ecology. International Journal of Environmental Sustainability and Protection, 2022; 2, 4. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, RP. Making political ecology. New York: Distributed in the United States of America by Oxford University Press; 2005.

- Brown JC, Purcell M. There’s nothing inherent about scale: political ecology, the local trap, and the politics of development in the Brazilian Amazon. Geoforum, 2005; 36, 607–24.

- Smith, N. Uneven development: Nature, capital, and the production of space. Athens, Geogia: University of Georgia Press; 2010.

- Smith, N. Contours of a spatialized politics: Homeless vehicles and the production of geographical scale. SText. 1992, (33), 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang F-l, Liu Y-g. Towards a theoretical framework of 'politics of scale'. Progress in Geography2017. p. 1500-9.

- MA X-G, LI L-Q. A Review Of Overseas Research On Politics Of Scale In Human Geography. Human Geography, 2016; 31, 02, 6-12+160. [CrossRef]

- DANJO, H. The Formation and Background of the Ming Dynasty Concept of Maritime Exclusion: From a Prohibition on Voyages in Foreign Waters to a Prohibition on Voyages for Trading with Foreigners. Oriental History Research. 2004, 63(3), 421–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu C-F. China and East Asia in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In: Mizoguchi Y, Hamashita T, Hiraishi N, Miyajima H, editors. Regional system Thinking from Asia. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press; 1993.

- Hu K-J. Farming the Sea,Herding and Fishing:A Study on the Fishery Activities of Fujian Coastal Residents in Ming and Qing Dynasties [master]: Guangxi Normal University; 2021.

- Chen R-X. Guangxu's "Zhangpu County Chronicles" Volume 8, “Fuyi Xia”, Chinese Local Chronicles Collection: Fujian County Chronicles Series.31. Shanghai Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House; 2000.

- Zhou, K. Chronicle of Xiamen, Fujian Province. Xiamen: Unpublish; 1967. p. 323.

- Zheng, Y. The Maritime Merchants and Pirates in Zhangzhou in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Journal of Maritime History Studies2014. p. 99-115.

- Dang X-H. The Historical Evolution and Contemporary Enlightenment of Marine Civil Organizations from the Ming and Qing Dynasties to the Republic of China——A Study Centered on Marine Fishery Production Mutual Aid Organizations. Agricultural Archaeology2014. p. 268-74.

- Zhuan, M. A Brief History of Jimei. Jimei, China: unpublisd; 2000.

- Yang B-S, Yan G-Z. Biography of Tan Kah Kee: Fujian, China: Fujian People’s Publish; 1981. 1981.

- Tsai Q-Y. Non-governmental Organizations and Famine Relief: A Study of the Huayang Charity Association in the Republic of China. Beijing: COMMERCIAL PRESS; 2005.

- Chen S-G, Pearson S. Managing China‘s Coastal Environment: Using a Legal and Regulatory Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Science and Development, 2015; 6, 3, 225–30. [CrossRef]

- WANG Y, JI X-M. Environmental Characteristics and Changes of Coastal Ocean as Land-ocean Transitional Zone of China. Scientia Geographica Sinica, 2011; 31, 2, 7.

- Sheng-Huan, Y. Xiamen: Vigorously crack down on illegal fishing and seize 27 illegal boats. 2019 11/15.

- Chen W-Q, Liu Y, Hong H-S, Xiao-Feng H. Research on the Value of Tourist-Recreation along the Eastern Coast of Xiamen Island. Journal of Xiamen University(Natural Science)2001. p. 914-21.

- Lin, Z. Transforming Mechanism, Invigorating Operations, Recreating Benefits——Investigation on the Restructuring of Xiamen Ocean Industry (Group) Co., Ltd. Chinese economic issues, 1994; 03, 54-7+26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao-shou, L. Humanities Jimei:Chen Jianhuang, the last handcrafted boat builder in Xunjiang: Jimei Tourism; 2017 [cited 2023 05/13]. Available from: https://www.sohu.com/a/131493416_480173.

- Zhu X-F. The Study of the Coastwise Fishermen in Fujian Province Since the Ming and Ching Dynasties [master]. Fuzou: Fujian Normal University; 2007.

- Wu, D. Visit Jimei Dashe in Xiamen, from a declining urban village to a gathering place for cultural and creative trends. China Business News. 2023 02/01.

- Ying J, Guo Y-F. The "two sessions" in Jimei District closed, and Chen Jianrong was elected as the director of the Standing Committee of the District People's Congress: Xiamen Net; 2015 [updated 2015/01/05; cited 2023 05/16]. Available from: http://xm.fjsen.com/2015-01/30/content_15622759_2.htm.

- Tong C-F, Zhang H. Traditional Fishermen’s Marginalized Poverty in the New Normal Situation. Journal of Ocean University of China(Social Sciences)2016. p. 46-53.

- Chunfen T, Xixi Z, Yi H. Marginalization of Fishermen:An Analytical Framework of Maritime Sociology. Sociological Review of China, 2013; 1, 03, 67–75.

- Fang Q-H. Strategic Environmental Assessment for Ecosystem Management in Coastal Areas [博士]. Xiamen: Xiamen University; 2006.

- Hui Wang, Zhe Zou, Shu-Chen Tsai. Exploring Environmental Restoration and Psychological Healing from Perspective of Resilience: A Case Study of Xinglin Bay Landscape Belt in Xiamen, China. International Journal of Environmental Sustainability and Protection, 2022; 2, 4, 44–54. [CrossRef]

- Television XRa. 3.1km! The Jimei Sea Ecological Landscape Corridor is about to open! Sina. 2023 05/23.

- Statistics FPBo. GDP of Xiamen City Fujian: Fujian Provincial Bureau of Statistics; 2022 [cited 2023 05/01]. Available from: https://gdp.gotohui.com/show-181727.

- Yang S-S, Lin L-M. Xiamen's GDP growth last year ranked first among 15 similar cities. 2023 2023-02-09.

- Rong-Chang, L. Study on the Measurement and Economic Effect of Regional Tourism Industry Agglomeration ——Take Xiamen as An Example [master]. Xiamen: Xiamen University; 2020.

- Stepanova O, Bruckmeier K. The relevance of environmental conflict research for coastal management. A review of concepts, approaches and methods with a focus on Europe. Ocean & coastal management, 2013; 75, 20–32. [CrossRef]

- Guo Y, Jiang J-B, Li S-C. A Sustainable Tourism Policy Research Review. SUSTAINABILITY, 2019; 11, 11, PubMed PMID: WOS:000472632200192. [CrossRef]

- Muldavin, J. The time and place for political ecology: An introduction to the articles honoring the life-work of Piers Blaikie. Geoforum. 2008, 39(2), 687–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroma Cole. A political ecology of tourism and water inequity: a case study from Bali. Annals of Tourism Research, 2012; 39, 2, 1221–41.

- Daily, J. Jimei fishermen go ashore to build "recreational fishing boats". 2012 03/05.

- Hall, CM. Trends in ocean and coastal tourism: the end of the last frontier? OCEAN & COASTAL MANAGEMENT 2001, 44(9-10), 601-18. PubMed PMID: WOS:000173223000004. [CrossRef]

- Xue X-Z, Hong H-S, Charles AT. Cumulative environmental impacts and integrated coastal management: the case of Xiamen, China. Journal of Environmental Management, 2004; 71, 3, 271–83.

- Hong H, Xu L, Zhang L, Chen JC, Wong YS, Wan TSM. Environmental fate and chemistry of organic pollutants in the sediment of Xiamen and Victoria Harbours. MARINE POLLUTION BULLETIN, 1995; 31, 4-12, 229–36, PubMed PMID: WOS:A1995TM84200012. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L-P, Ye X, Feng H, Jing Y-H, Ouyang T, Yu X-T, et al. Heavy metal contamination in western Xiamen Bay sediments and its vicinity, China. MARINE POLLUTION BULLETIN, 2007; 54, 7, 974–82, PubMed PMID:WOS:000248562500027. [CrossRef]

- Maskaoui K, Zhou JL, Hong HS, Zhang ZL. Contamination by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the Jiulong River Estuary and Western Xiamen Sea, China. ENVIRONMENTAL POLLUTION, 2002; 118, 1, 109–22, PubMed PMID: WOS:000174174700011. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Huang ZY, Hu Y, Yang H. Potential risk assessment of heavy metals by consuming shellfish collected from Xiamen, China. ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE AND POLLUTION RESEARCH, 2003; 20, 5, 2937–47, PMID: WOS:000318175400022. [CrossRef]

- Klumpp DW, Hong HS, Humphrey C, Wang XH, Codi S. Toxic contaminants and their biological effects in coastal waters of Xiamen, China. I. Organic pollutants in mussel and fish tissues. MARINE POLLUTION BULLETIN, 2002; 44, 8, 752–60, PubMed PMID: WOS:000177930500016. [CrossRef]

- Klumpp DW, Humphrey C, Hong HS, Feng T. Toxic contaminants and their biological effects in coastal waters of Xiamen, China. II. Biomarkers and embryo malformation rates as indicators of pollution stress in fish. MARINE POLLUTION BULLETIN, 2022; 44, 8, 761–9, PubMed PMID: WOS:000177930500017. [CrossRef]

- Jin X-S, Tang Q-S. Changes in fish species diversity and dominant species composition in the Yellow Sea. Fisheries Research1996. p. 337-52.

- Yeung LWY, So MK, Jiang GB, Taniyasu S, Yamashita N, Song MY, et al. Perfluorooctanesulfonate and related fluorochemicals in human blood samples from China. ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY, 2006; 40, 3, 715–20, PubMed PMID: WOS:000235227600021. [CrossRef]

- Luo X-S, Ding J, Xu B, Wang Y-J, Li H-B, Yu S. Incorporating bioaccessibility into human health risk assessments of heavy metals in urban park soils. SCIENCE OF THE TOTAL ENVIRONMENT. 2012, 424, 88–96, PubMed PMID: WOS:000303956900010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao YG, Wan HT, Law AYS, Wei X, Huang YQ, Giesy JP, et al. Risk assessment for human consumption of perfluorinated compound-contaminated freshwater and marine fish from Hong Kong and Xiamen. Chemosphere, 2011; 85, 2, 277–83, PubMed PMID: WOS:000297612700021. [CrossRef]

- Gamarra NC, Costa ACL, Ferreira MAC, Diele-Viegas LM, Santos APO, Ladle RJ, et al. The contribution of fishing to human well-being in Brazilian coastal communities. Marine Policy, 2023; 150, 105521. [CrossRef]

- Huang L-M, Wang J-Q, Shih Y-J, Li J, Chu T-J. Revealing the Effectiveness of Fisheries Policy: A Biological Observation of Species Johnius belengerii in Xiamen Bay. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2022; 10, 6, 732. [CrossRef]

- Iaccarino, M. Science and culture: Western science could learn a thing or two from the way science is done in other cultures. EMBO reports. 2003, 4(3), 220–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folke C, Colding J, Berkes F. Synthesis: building resilience and adaptive capacity in social-ecological systems. Navigating social-ecological systems: Building resilience for complexity and change, 2003; 9, 1, 352–87.

- Berkes, F. Traditional ecological knowledge and resource management. Philadelphia and London: Taylor and Francis; 1999. [CrossRef]

- Berkes F, Folke C. Back to the future: ecosystem dynamics and local knowledge. In: Gunderson LH, Holling CS, editors. Understanding Transformation in Human and Natural Systems. Washington DC: Island Press; 2002. p. 121-46. 2002.

- MA X-g, LI L-q. A REVIEWOF OVERSEAS RESEARCH ON POLITICS OF SCALE IN HUMAN GEOGRAPHY. HUMAN GEOGRAPHY2016. p. 6-12,160.

| Case | Code | Gender | Age | Background of interviewee and Interview Summary | Time of Interviewed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M-a | Male | About 70 years old (Mr. Chen) |

Reside in Jimei Dashe, belonging to the Chen clan of Dashe. Has been living near the Jiageng Memorial Hall since birth. Engaged in aquaculture in the coastal waters near Jimei Bridge. Prior to the implementation of the coastal Exclusion Policy in 2002, cultivated clams as a sideline. Received compensation when Jimei implemented the Coastal Exclusion Policy in 2006. The interviewee has experienced the entire process of coastal governance in Xiamen. | 2023-04-15 |

| 2 | M-b | Male | About 20 years old (Mr. Chen, student) |

Reside in Jimei Dashe, belonging to the Chen clan of Dashe. Born in 2000 and has been living in Jimei Dashe. During the period of the Coastal Exclusion Policy, the interviewee was still young and lived near the Jiageng Memorial Hall. Used to play on the beaches near Ao Garden when young, thus having a clear understanding of the changes in the coastal environment. | 2023-04-15 |

| 3 | M-c | Male | About 30 years old (Mr. Chen, boss) |

Reside in Xiang'an District, belonging to the local residents and fishermen. Owns a fishing boat and relied on aquaculture and fishing for a living in the village over twenty years ago. Joined the father in going out to sea at a young age and personally experienced the process of coastal governance in Xiamen. Has deep insights into the Coastal Exclusion Policy and other policies. | 2023-04-16 |

| 4 | F-a | Female | About 40 years old (Ms. Chen) |

Reside in Jimei Dashe, belonging to the Dashe residents. Has been operating a vegetable stall in the area for many years and has a clear understanding of the changes in local seafood harvest. | 2023-04-20 |

| 5 | M-d | Male | About 50 years old (Mr. Chen) |

Reside in Jimei Dashe, belonging to the Dashe residents. Has been operating a vegetable stall in the area for many years and is responsible for sourcing vegetables and seafood. Has a good understanding of the changes in Jimei Dashe's aquaculture households and the fishing and aquaculture situation in the surrounding waters. | 2023-04-20 |

| 6 | F-b | Female | About 60 years old (Ms. Chen) |

Reside in Jimei Dashe, belonging to the Dashe residents. Buys oysters from seafood vendors for further processing and selling to oyster pancake businesses. Engaged in this activity on a daily basis and has a clear understanding of the changes in the source of seafood during the coastal governance period in Xiamen. | 2023-04-20 |

| 7 | F-c | Female | About 50 years old (Ms. Lin) |

Reside near Beihai Bay and often take children to dig clams under Jimei Bridge. Has a profound experience of the entire process of coastal governance in Xiamen. Believes that the seawater has been purified, the amount of garbage has reduced, and the scenery has become more beautiful, but the area of intertidal flats has decreased. | 2023-05-29 |

| 8 | M-e | Male | About 50 years old (Mr. Liu) |

Reside near Xinglin Bay, originally from Henan province. Discharged from the military and relocated to Xiamen in the 1980s. Has a deep understanding of the ecological changes in Xinglin Bay, which used to be an aquaculture farm with a poor environment. Considers Xiamen's coastal governance to be quite effective, with improvements in ecological and residential environments. Personally, witnessed the landscape construction of the Xinglin Bay coastline. | 2023-04-09 |

| 9 | M-f | Male | About 30 years old (Mr. Chen) |

Resides in Jimei Dashe, a local resident responsible for enrolling students at Chen's Elementary School. Has frequent contact with local residents and has knowledge about various aspects. Has experienced the transformation of the lifestyle of Dashe residents during the coastal governance in Xiamen over the past twenty years. Previously, family members were engaged in fishing, thus having a good understanding of fishing and aquaculture. Has a detailed understanding of the changes in the coastline and believes that the beaches are now artificially filled, and local people are no longer engaged in marine occupations. Conducted using the focus interview method. | 2023-05-30 |

| 10 | M-g | Male | About 50 years old (Mr. Chen) |

Resides in Jimei Dashe, a local resident who personally experienced the transformation of the local residents' way of life. Used to dig clams with friends on the beach as a child. Familiar with the changes in the coastline and has family members who used to be fishermen or engaged in aquaculture but have now switched to other occupations. | 2023-05-29 |

| 11 | F-d | Female | About 40 years old (Ms. Chen) |

Resides in Jimei Dashe, a local resident and community staff member. Has a good understanding of the lifestyle of Dashe residents and is knowledgeable about the work arrangements for fishermen after coming ashore. Believes that local residents have security after coming ashore, and the scenery and ecological environment in Dashe have improved. Conducted using the focus interview method. | 2023-05-30 |

| 12 | F-e | Female | About 30 years old (Ms. Lin) |

Resides in Jimei Dashe, a non-local resident who joined the community and is responsible for the labor security of Xunjiang community residents. Previously, helped unemployed fishermen find work before 2018, but in recent years, the employment situation of fishermen coming ashore has become more stable. Conducted using the focus interview method. | 2023-05-30 |

| 13 | F-f | Female | About 40 years old (Ms. Chen) |

Resides in Jimei Dashe, a non-local resident who joined the community and is responsible for resolving disputes among Xunjiang community residents. Has knowledge of the work arrangements for fishermen in Dashe and is familiar with the current working methods in the area. Conducted using the focus interview method. | 2023-05-30 |

| 14 | F-g | Female | About 50 years old (Ms. Chen) |

Resides in Jimei District, a long-standing community employee with a clear understanding of the development in Dashe. Experienced the entire process of implementing coastal governance policies in Xiamen and believes that the policies have been effective in improving water quality, managing fishermen, and protecting the ecological environment. However, there have been changes in the lifestyle of fishermen. Conducted using the focus interview method. | 2023-05-30 |

| 15 | M-h | Male | About 50 years old (Mr. Lin) |

Resides in Xiamen Siming District, moved to Jimei Normal School with parents at the age of eight and attended Jimei Elementary School. Grew up and worked in Jimei District. Often went to the beach with friends when young and has a deep understanding of coastal development. Believes that the coastal zone before 1987 was better than it is now. | 2023-05-31 |

| 16 | M-i | Male | About 30 years old (Mr. Chen) |

Resides in Jimei Dashe, a resident of the area and a sailing enthusiast. Grew up by the seaside and has firsthand experience of the changes in the coastline. | 2023-05-31 |

| 17 | M-j | Male | About 60 years old (Mr. Chen) |

Resides in Jimei Dashe, a local resident. Engages in digging clams on a daily basis to supplement household income. Buys clams from friends, processes them, and sells them to nearby businesses. Has a good understanding of the development trends of seafood in Xiamen and has personally experienced the changes in the coastline over the past twenty years of coastal governance. | 2023-06-04 |

| 18 | F-h | Female | About 60 years old (Ms. Chen) |

Resides in Jimei Dashe, a local resident and member of the Chen clan association. Familiar with the lifestyle changes of Dashe residents and has a deep experience of the entire process of coastal governance. | 2023-06-04 |

| 19 | M-k | Male | About 70 years old (Mr. Chen) |

Resides in Jimei Dashe, a local resident. Member of the Chen clan association, knowledgeable about the lifestyle of Dashe residents, familiar with the local living culture, and aware of the changes in the fishing community's culture. | 2023-06-04 |

| 20 | F-i | Female | About 60 years old (Ms. Chen) |

Resides in Jimei Dashe, a local resident. Engages in the sale of fish, familiar with the fishing trends in Jimei, including fishing methods and locations, and has witnessed the changes in fishing practices over the past twenty to thirty years of coastal governance. | 2023-06-04 |

| 21 | M-l | Male | About 70 years old (Mr. Chen) |

Resides in Jimei Dashe, a local resident and retired high school teacher. Concerned about the shift in policy development, has a keen understanding of the changes in the coastline and intertidal flats, and holds a macroscopic view of the impact of policies on the lifestyle of local residents. | 2023-06-04 |

| No. | Law/Regulations | Year | Level | Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | To levy Java, temporarily ban merchants and navigators from Zhejiang, Guangdong, and Fujian. (Yuan Dynasty) | 1292 | National | National |

| 2 | Forbid merchants to go to sea. (Yuan Dynasty) | 1303 | National | National |

| 3 | Banning ships from going to sea. (Yuan Dynasty) | 1311 | National | National |

| 4 | Prohibition of coastal residents from contacting overseas countries privately. (Ming Dynasty) | 1381 | National | National |

| 5 | Sea ban imposed, coastal residents head inland. (Ming Dynasty) | 1387 | National | National |

| 6 | Lift the sea ban, adjust the overseas trade policy, and allow the private sector to sell far and wide. (Ming Dynasty) | 1567 | National | National |

| 7 | Move to Sea Order. (Ching Dynasty) | 1661 | National | National |

| 8 | Strictly ban access to the sea. (Ching Dynasty) | 1662 | National | National |

| 9 | The people migrated to the mainland, and the sea was strictly prohibited, and their traffic was cut off. (Ching Dynasty) | 1678 | National | National |

| 10 | lifting the ban on maritime trade. (Ching Dynasty) | 1683 | National | National |

| 11 | Nanyang Maritime Ban. (Ching Dynasty) | 1717 | National | National |

| 12 | Xiamen fishermen's union was established. | 1956 | Municipal | local |

| 13 | Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone. | 1958 | International | International |

| 14 | Geneva Convention on the High Seas. | 1962 | International | International |

| 15 | Convention on the continental shelf. | 1964 | International | International |

| 16 | Convention on Fishing and Conservation of the Living Resources of the High Seas. | 1966 | International | International |

| 17 | Convention for the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Substances, 1972 (London Convention). | 1972 | International | International |

| 18 | Marine Environment Protection Law. | 1982 | National | National |

| 19 | Maritime Traffic Safety Law. | 1983 | National | National |

| 20 | Regulations on Administration of Environmental Protection in the Exploration and Development of Offshore Petroleum. | 1983 | National | National |

| 21 | The fishermen commune was reorganized as Xiamen second Marine fishery Company. | 1984 | Municipal | local |

| 22 | Regulations on Control of Dumping of Wastes in the Ocean | 1985 | National | National |

| 23 | Fisheries Law. | 1986 | National | National |

| 24 | Mineral Resources Law. | 1986 | National | National |

| 25 | Law on Land Resources Governance. | 1986 | National | National |

| 26 | Regulations Concerning Prevention of Environmental Pollution by Ship-breaking. | 1988 | National | National |

| 27 | Environmental Protection Law. | 1989 | National | National |

| 28 | Law on the Protection of Wildlife. | 1989 | National | National |

| 29 | Regulations Concerning Prevention and Control of Pollution Damages to the Marine Environment by Coastal Construction Projects. | 1990 | National | National |

| 30 | Regulations Concerning Prevention of Pollution Damage to the Marine Environment by Land-based Pollutants. | 1990 | National | National |

| 31 | Law on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone. | 1992 | National | National |

| 32 | Implementation Regulations on Protection of Aquatic Wildlife. | 1993 | National | National |

| 33 | The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). | 1994 | International | International |

| 34 | Regulations of Natural Protected Reserves. | 1994 | National | National |

| 35 | Xiamen Marine Governance Office was established. | 1996 | Municipal | Regional |

| 36 | Marine function zoning of Xiamen City. | 1996 | Municipal | Regional |

| 37 | Xiamen sea area environmental protection provisions. | 1997 | Municipal | Regional |

| 38 | Xiamen shallow sea shoal aquaculture governance provisions. | 1997 | Municipal | Regional |

| 39 | Xiamen Chinese white dolphin protection provisions. | 1997 | Municipal | Regional |

| 40 | Law on Exclusive Economic Zones and Continental Shelves. | 1998 | National | National |

| 41 | Law on the Administration of the Use of Sea Areas. | 2001 | National | National |

| 42 | Xiamen Ocean and Fisheries Bureau was established. | 2002 | Municipal | Regional |

| 43 | Law on Evaluation of Environmental Affects. | 2002 | National | National |

| 44 | Notice of Xiamen Municipal People's Government on the Comprehensive regulation of aquaculture prohibition in the West Sea Area. ("Coastal Exclusion Policy") | 2002 | Municipal | Regional |

| 45 | Port Law. | 2003 | National | National |

| 46 | Provisions of Xiamen City on the Administration of the use of sea areas | 2003 | Municipal | Regional |

| 47 | Notice of Xiamen Municipal People's Government on Strengthening Aquaculture Governance in the East Sea area of Xiamen. | 2003 | Municipal | Regional |

| 48 | The General Office of Xiamen Municipal People's Government forwarded the notice of the Municipal Bureau of Marine Affairs and Fisheries on the second round of Xiamen Comprehensive Coastal Zone Governance (ICM) Strategic Action Plan. | 2005 | Municipal | Regional |

| 49 | Regulations Concerning Prevention and Control of Pollution Damage to the Marine Environment by Marine Construction Projects. | 2006 | National | National |

| 50 | Notice of the General Office of Xiamen Municipal People's Government on carrying out the work of maritime boundary demarcation in the city. | 2008 | Municipal | Regional |

| 51 | Law on the Protection of Offshore Islands. | 2009 | National | National |

| 52 | Regulations on Prevention and Control of Marine Environment Pollution from Ships. | 2009 | National | National |

| 53 | Provisions of Xiamen City on Marine environmental protection. | 2009 | Municipal | Regional |

| 54 | Measures for the Implementation of Xiamen Marine Aquaculture Exit Compensation. | 2009 | Municipal | Regional |

| 55 | Xiamen Marine and Fisheries Bureau is divided into Xiamen Marine Development Bureau, Xiamen Ecological Environment Bureau, and Xiamen Natural Resources and Planning Bureau. | 2018 | Municipal | Regional |

| 56 | Measures of Xiamen for the Administration of Marine ecological compensation. | 2018 | Municipal | Regional |

| 57 | Opinions of Xiamen Municipal People's Government on strengthening governance of sea-related tourism. | 2018 | Municipal | Regional |

| 58 | The coastal landscape construction is in charge of Xiamen Municipal Garden and Forestry Bureau. | 2021 | Municipal | Regional |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).