1. Introduction

Photo-thermal catalysis combines photo-chemical and thermochemical contributions of sunlight and has emerged as a rapidly growing and exciting new field of research [

1,

2,

3].

Photo-thermal catalysis with application of semiconductor doped by metallic nanoparticles allows for a more effective harvesting of the solar spectrum, including low-energy visible and infrared photons.

Certain metallic nanoparticles (NPs) such as Au, Ag, Cu and others exhibit unique optical properties related to the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), which can be tunable by varying their size and shape across the entire visible spectrum [

4,

5].

In the LSPR process hot charge carriers are generated, which possess higher energies than those induced by direct photoexcitation. These energetic carriers can be transferred to the adsorbate surface or conductive band of semiconductor or can relax internally and dissipate their energy by local heating of the surroundings, causing a thermal effect on the material. This photo-thermal effect has been extensively applied in a large number of fields, including cancer therapy, degradation of pollutants, CO

2 reduction, hydrogen production by water splitting and other chemical reactions such as ex. catalytic steam reforming or hydrogenation of olefins [

2,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Photo-thermal effect can be also obtained in non-plasmonic structures through direct intraband and/or interband electronic transitions. For instance, Sarina et al. [

14] demonstrated that non-plasmonic metal NPs supported on ZrO

2 could catalyze cross-coupling reactions at low temperatures under visible light. According to the authors, upon irradiation with UV light electrons could shift to high-energy levels through interband transitions, and only those with enough energy could transfer to the LUMO of adsorbed molecules, just like in the case of plasmonic metal NPs. When excited with low-energy visible-IR light, electrons were not energetic enough to be injected into adsorbate states, thus contributing to the enhancement of the reaction rate by means of thermal effects. Altogether, photochemical and thermal effects contribute to the photo-thermal performance in non-plasmonic semiconductors.

The size, shape and quantity of the plasmonic nanoparticles contributing in the photo-thermal effect are important. The temperature increase is proportional to the square of the nanoparticle radius. However, it was theorized, that the temperature increment due to the irradiation of a single nanoparticle became negligible, but the light-induced heating effect could be strongly enhanced in the presence of a large number of NPs owing to the collective effects [

2]. Theoretical calculations have demonstrated that larger plasmonic NPs provide a larger amount of hot carriers, but they display energies close to the Fermi level, since most of the absorbed energy is dissipated either by scattering or by heating. In contrast, smaller NPs exhibit higher energies but they are showing very short lifetimes [

2]. Lower size plasmonic NPs show blue shift absorption edge due to the quantum size effect [

15]. All these parameters are extremely important during design the nanomaterial for the thermo-photocatalytic processes.

The most intensively explored plasmonic NPs used in the photo-thermal processes so far are based on Au, Ag, Pd, Cu and Pt nanoparticles, less are reported on the other metals such as Ni or Co. Thermo-photocatalytic decomposition of acetaldehyde was reported on TiO

2 doped by Pt, Ag, Pd, or Au nanoparticles [

10,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Among all these doped metals to TiO

2, Pt had the highest activity due to the strong thermo-catalytic effect at elevated temperature. The activity of metal or metal oxide doped to TiO

2 depended on the oxidation state of metal and their adsorption abilities towards acetaldehyde species. The other structures, such as metal nanowires coated by TiO

2 were also prepared and tested for the acetaldehyde removal [

20,

21]. There are some reports on application of nickel foam with loaded TiO

2 for different purposes, such as: anode for lithium-ion batteries [

22], hydrogen evolution from water splitting [

23], toluene and acetaldehyde decompositions [

24,

25], nitrogen oxides removal [

26] and others. Nickel foam was also used as a support and catalyst for different materials in the photocatalytic processes [

27,

28,

29]. As a main advantage of application the nickel foam as a composite with other photocatalyst is significant improvement of charge separation in the photocatalytic material.

Although some reports on the application of nickel foam with loaded TiO2 have been already published, in these studies there is proposed the first time mechanism of thermo-photocatalytic decomposition of acetaldehyde under UV light at the presence of TiO2 supported on the nickel foam, and this is compared with others, which occur, when oxidised nickel foam or nanosized Ni particles added to TiO2 are utilised.

2. Materials and Methods

TiO

2 of anatase phase was obtained by two-step process: hydrothermal treatment of amorphous titania (Police Chemical Factory, Poland) in deionized water in 150°C under pressure of 7.4 bar for 1 hour and following annealing in a pipe furnace in 400°C under Ar flow for 2 hours. Our previous work presented the detailed physicochemical characterizations of this material [

30].

Nickel foam (China) with purity of 99.8% had the following parameters: thickness: 1.5mm, porosity: 95%-97%, Surface density: 300 g/m2. Nickel powder (Warchem, Poland) had a purity of 99.8%.

XRD measurements of nickel foams were performed using the diffractometer (PANanalytical, The Netherlands) with a Cu X-ray source, λ = 0.154439 nm. Measurements were conducted in the 2θ range of 10-100° with a step size of 0.013. The applied voltage was 35 kV and the current was 30 mA.

SEM/EDS images were obtained using a field emission scanning electron microscope with high resolution (UHR FE-SEM, Hitachi, Japan).

Oxidation of nickel foams was carried out in a muffle furnace (Czylok SM-2002, Poland) at 500°C for 1 hour.

The chemical composition was determined through X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis. The measurements were conducted using a commercial multipurpose ultra-high vacuum (UHV) surface analysis system (PREVAC, Rogow, Poland). A nonmonochromatic XPS source and a kinetic electron energy analyzer (SES 2002; Scienta) was used. The spectrometer was calibrated using the Ag 3d5/2 transition. The XPS analysis utilized Mg Kα (h=1253.6 eV) radiation as the excitation source.

The size of nickel powdered nanoparticles was determined using an atomic force microscope (AFM; NanoScope V Multimode 8, Bruker, USA) with a silicon nitride probe in ScanAsyst mode. Prior to measurement, the samples were dispersed in isopropyl alcohol and then drop casted onto a silicon wafer. Obtained surface topography images were obtained using NanoScope Analysis software, whereas particle sizes were evaluated via ImageJ software.

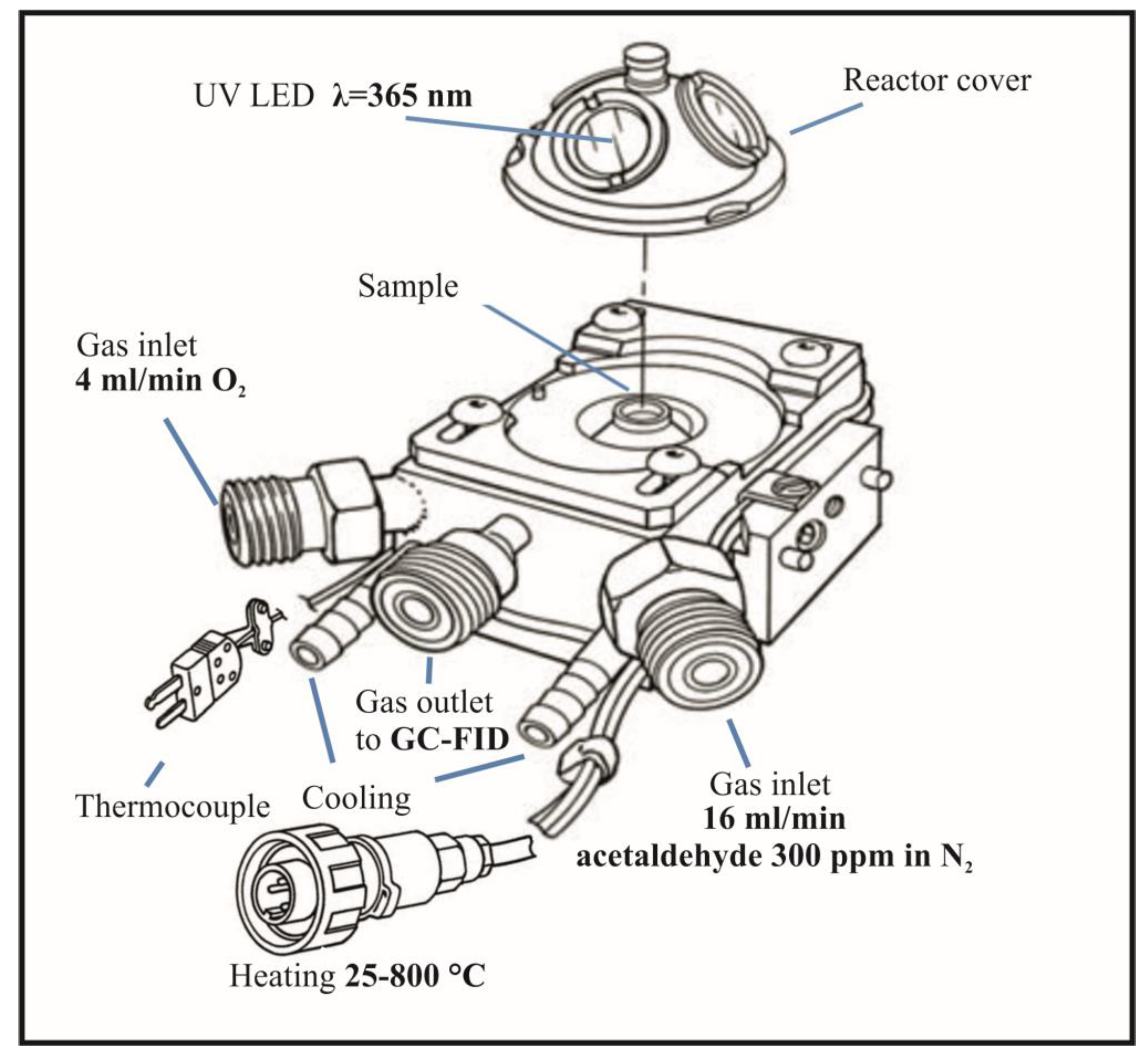

Thermo-photocatalytic decomposition tests of acetaldehyde were conducted using high temperature reaction chamber (Harrick, USA), as shown in

Figure 1. During the test, continuous FTIR measurements were conducted using Thermo Nicolet iS50 FTIR instrument (Thermo, USA).

UV irradiation was conducted through a quartz window, with an illuminator equipped with a fiber optics and a UV-LED, 365 nm diode with an optical power of 415 mW (Poland, LABIS). Gases were supplied from bottles through two inlets using mass flow meters. The first one was acetaldehyde in nitrogen, 300 ppm (Messer), the second one was a synthetic oxygen with purity 5.0 (Messer). Gases have been mixed in proportions to create a synthetic air composition. After the thermo-photocatalytic process the gas stream was directed to the gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with automatically dosing sample loop (GC-FID, SRI, USA). Acetaldehyde concentration was determined from recorded chromatograms in GC. Outlet gas stream from GC was flowing through the CO2 sensor (APFinder CO2, ATUT Company, Poland) in order to monitor the quantity of CO2 formed upon acetaldehyde mineralization.

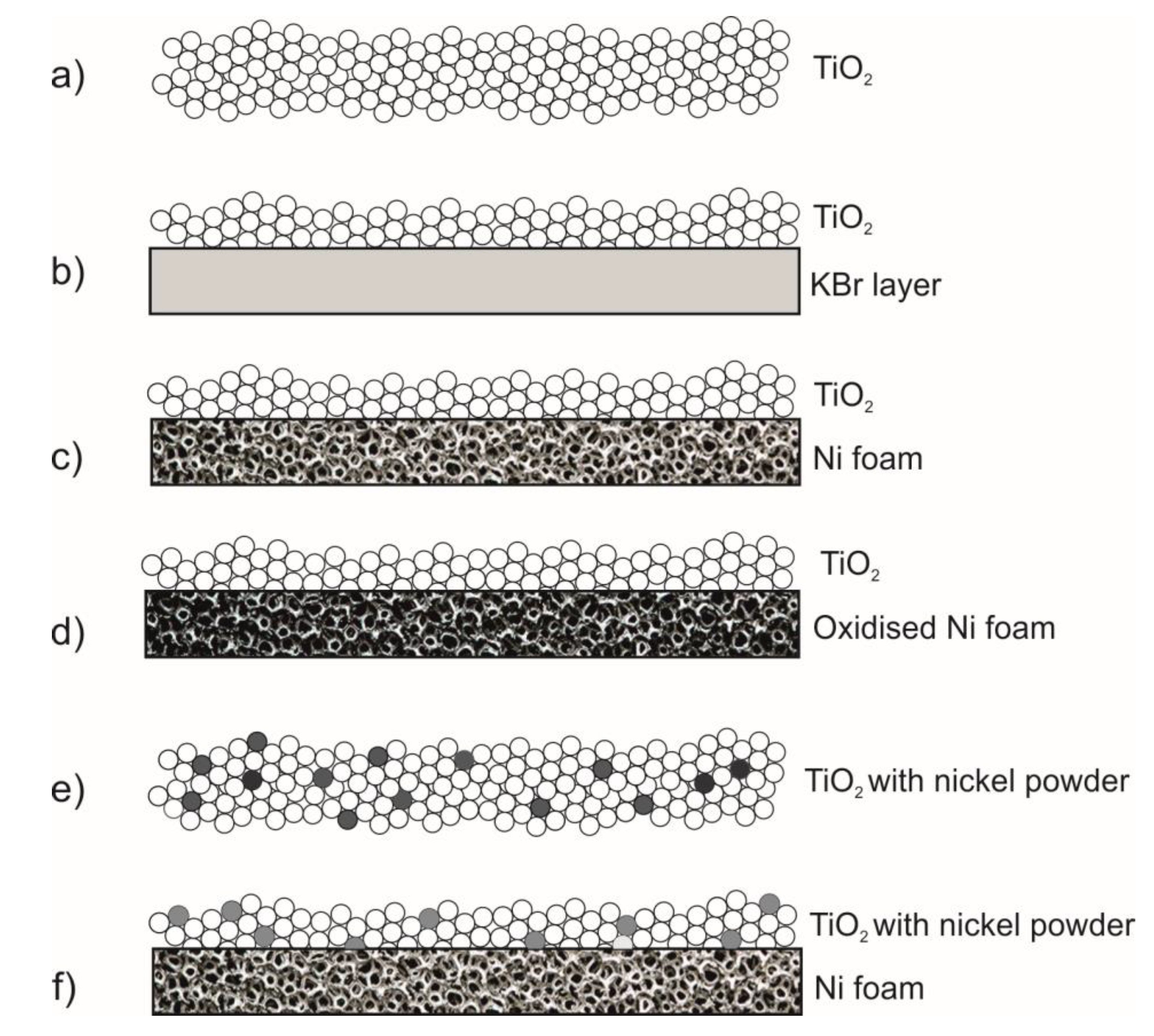

The catalytic systems that have been used in the tests are as follows: a) TiO

2, b) a thin layer (1mm) of TiO

2 supported on KBr which is inert to acetaldehyde, c) a thin layer of TiO

2 supported on Ni foam, d) a thin layer of TiO

2 supported on the oxidised Ni foam, e) TiO

2 blended with the nickel powder in the various amount, 0.5-5 wt. %. In

Figure 2 there is illustrated the scheme of the materials compositions used for the photocatalytic tests of acetaldehyde decomposition.

3. Results

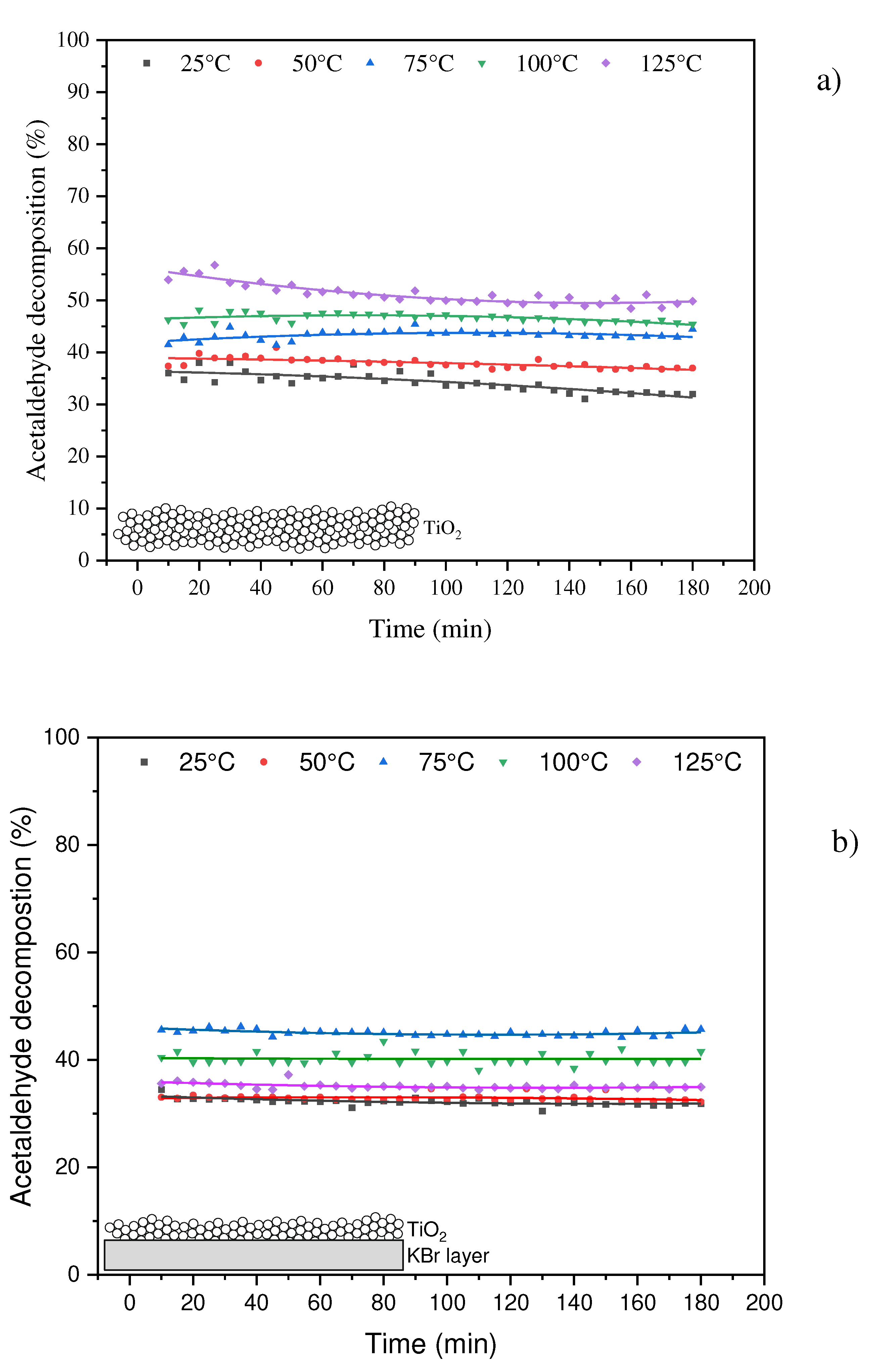

The results from the thermo-photocatalytic decomposition of acetaldehyde over TiO

2 and UV LED irradiation are illustrated in

Figure 3.

Performed measurements indicated, that conversion of acetaldehyde on TiO

2 could be enhanced at elevated temperature, In case of a thick layer of TiO

2 used (without KBr),

Figure 3b, the highest acetaldehyde conversion was observed at 125

oC, however this process was not stable and indicated gradual falling-off in degradation rate, reaching its maximum after 180 min of UV irradiation with conversion of 50%. Contrary to that, application of a thin layer TiO

2 supported on KBr allowed to get stabilization of the process, but the highest conversion of acetaldehyde was lower than in case of using TiO

2 only and reached 47% at 75

oC. In

Table 1 there are presented results from measurements of CO

2 in the outlet stream of reacted gases.

These results indicated, that mineralization of acetaldehyde was higher in case of the photocatalytic system used with a thin layer of TiO2. Acetaldehyde can be oxidized over TiO2 in a dark at the presence of oxygen, however its complete mineralization occurs at the presence of reactive radicals. Most likely TiO2 at the bottom of reactor chamber was not activated by UV light, and formed products of acetaldehyde decomposition at the lower part of TiO2 were scavengers for reactive radicals formed at the surface of TiO2 on the top of reactor. Therefore, for higher quantity of TiO2 used, acetaldehyde conversion was higher, but its mineralization to CO2 dropped down.

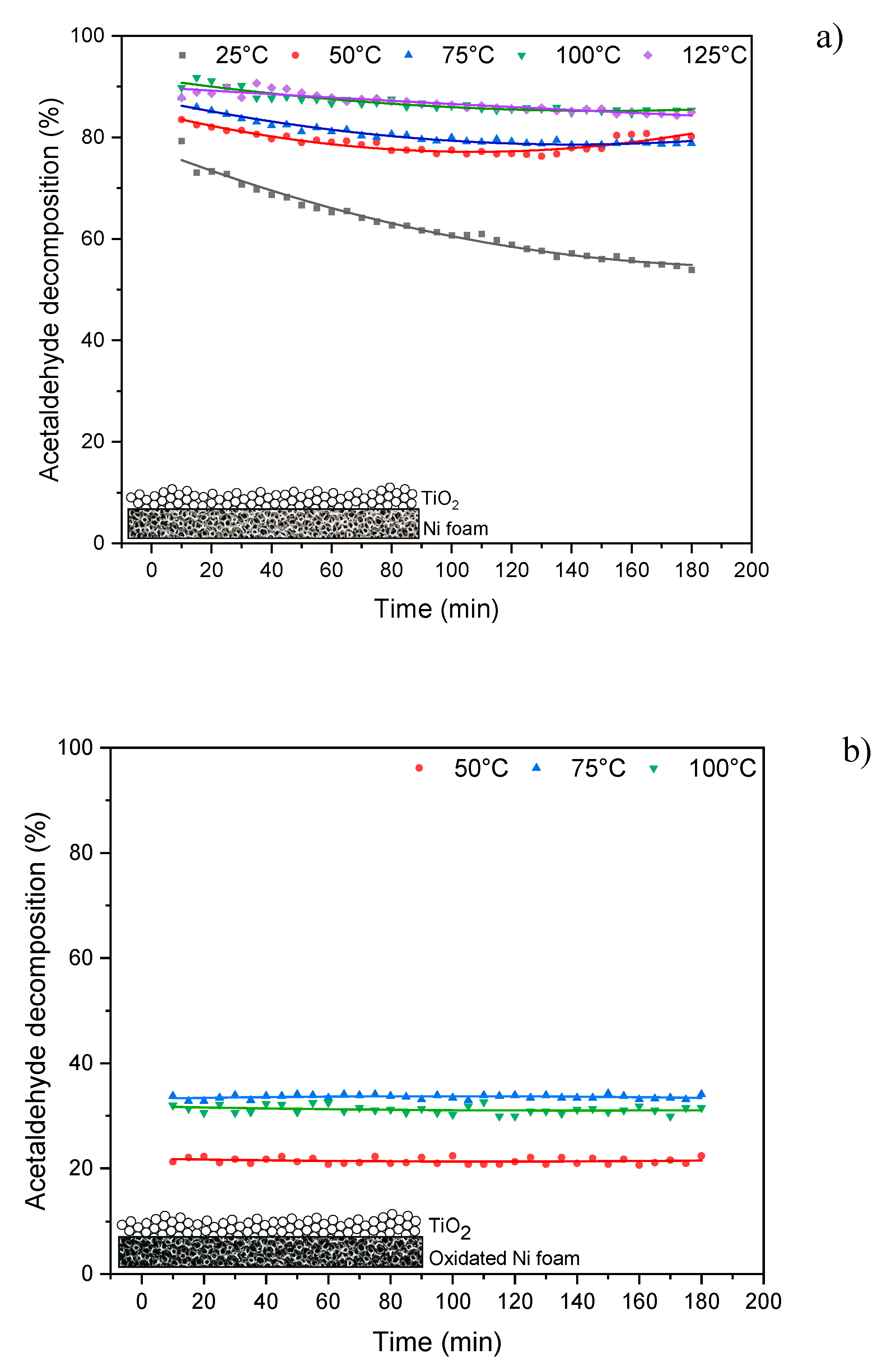

In

Figure 4 there are presented results from the thermo-photocatalytic decomposition of acetaldehyde over TiO

2 supported on the nickel foam.

High decomposition of acetaldehyde (around 85%) was observed at the presence of TiO

2 supported on Ni foam and reaction temperature of 100-125°C. The slight decrease in acetaldehyde decomposition over time is due to by-products blocking the catalyst’s active centers. However the efficiency of this process significantly decreased at the presence of oxidised Ni foam, the decomposition of acetaldehyde dropped down to 33%. It has to be mentioned, that Ni foam as received was much less active than that after photocatalytic process. Therefore all the results presented in

Figure 4a were performed for reused nickel foam.

In

Table 2 there are presented results from measurements of CO

2 after thermo-photocatalytic process of acetaldehyde decomposition conducted for TiO

2 supported on reused Ni foam and that oxidized at 500

oC.

Application of reused Ni foam with TiO2 not only enhanced decomposition rate of acetaldehyde, but also double increased its mineralization degree.

In

Figure 5 there are presented results from the photocatalytic decomposition of acetaldehyde over TiO

2 blended with nanosized Ni powder.

The quantity of doped Ni slightly affected the efficiency of acetaldehyde decomposition, which ranged from 38 to 43%. In temperature of 125oC the process yield was the highest and reached around 50% for 1% of doped Ni to TiO2. Although acetaldehyde decomposition rate on TiO2 doped with Ni was quite comparable with that for TiO2, the mineralization degree was low, the maximum value of formed CO2 was 150 ppm, which was reached for 1% of doped Ni at reaction temperature of 75oC, for the other tests the quantity of formed CO2 was lower.

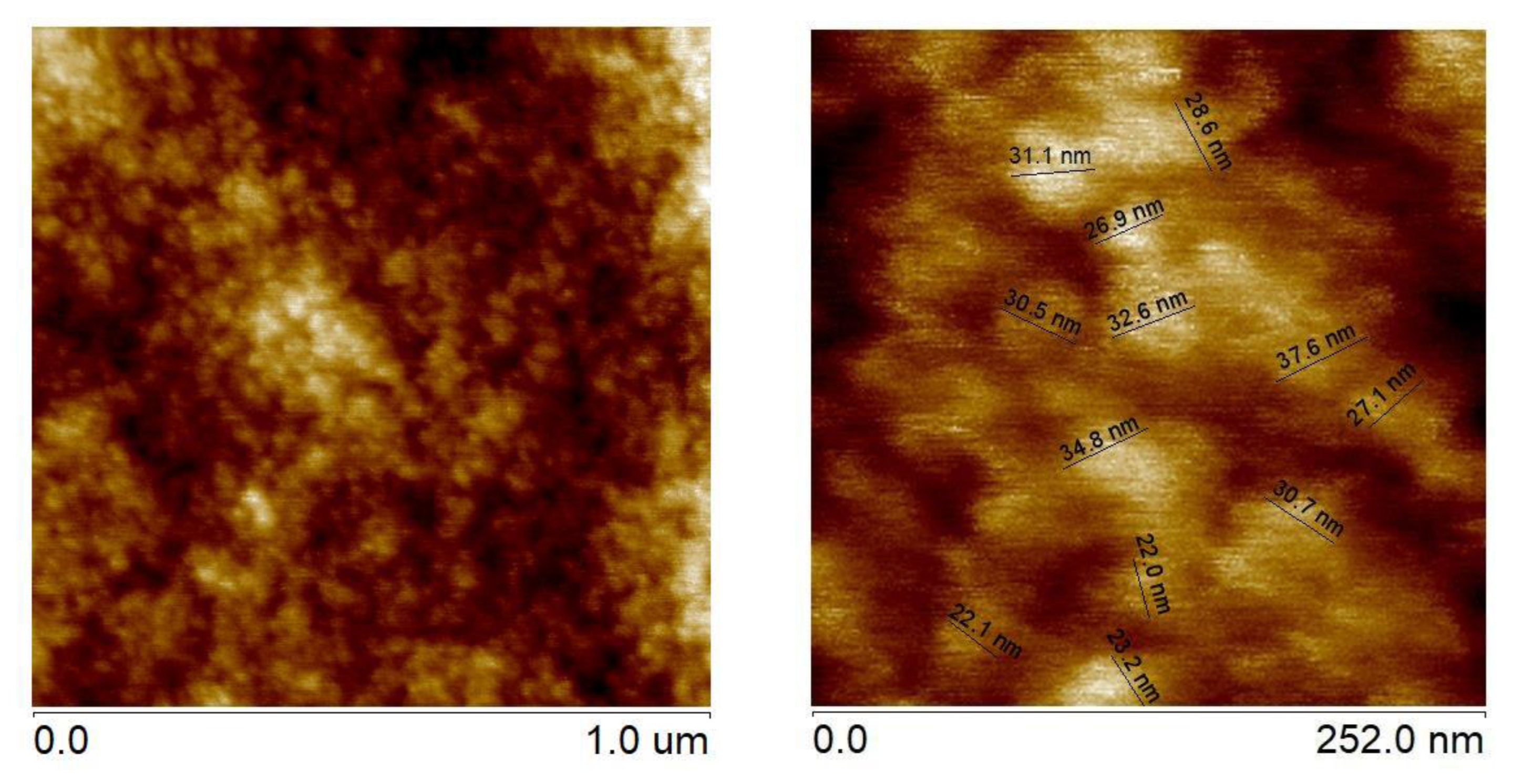

AFM analyses of surface topography with loaded Ni particles indicated, that their mean size was c.a. 30 nm, as shown in

Figure 6.

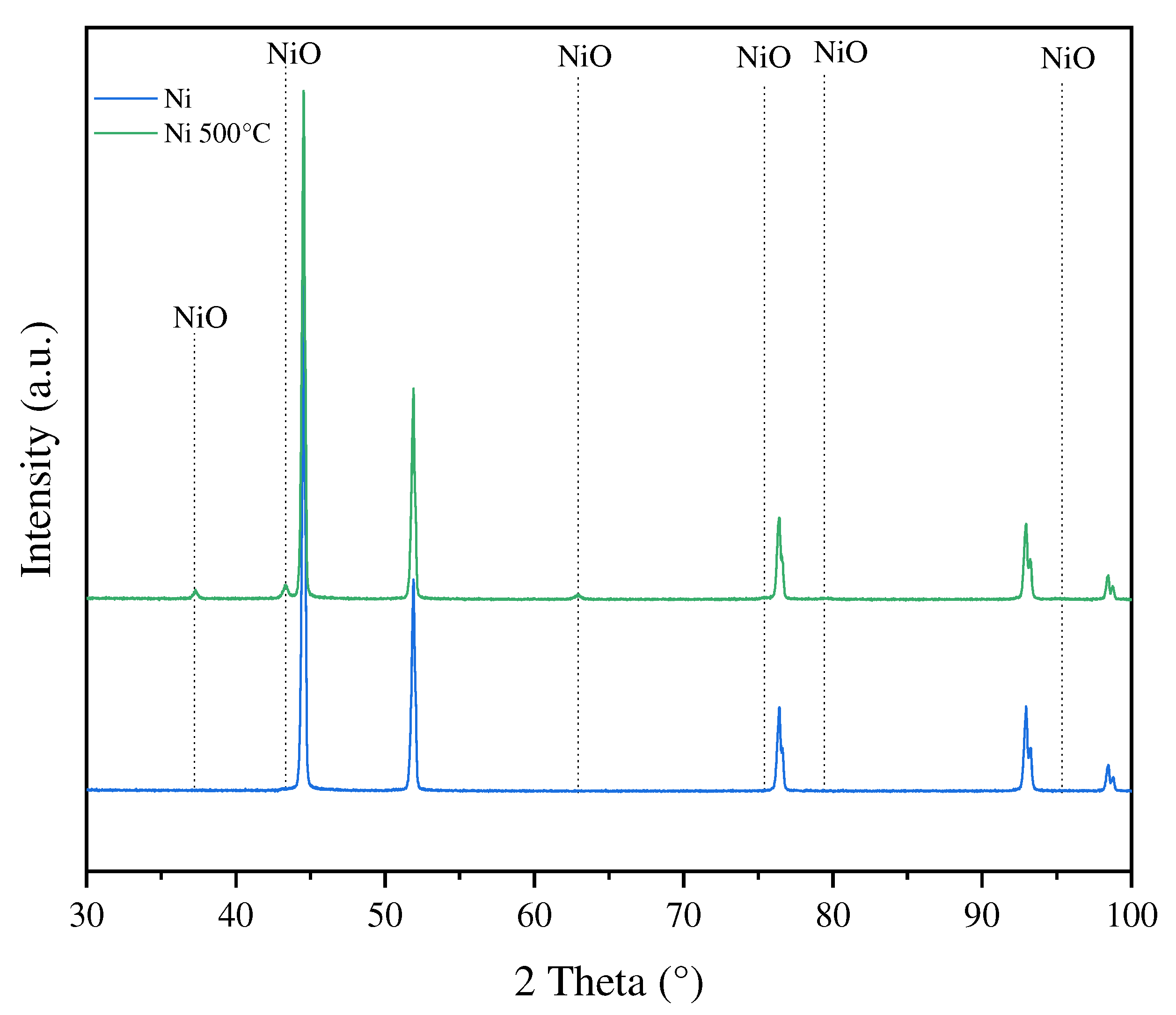

In

Figure 7 XRD patterns of Ni foam as received and after oxidation at 500

oC in air are illustrated.

After oxidation of Ni foam in temperature of 500oC new reflexes emerged, which were ascribed to NiO phase, however their intensities were much lower than those related to Ni.

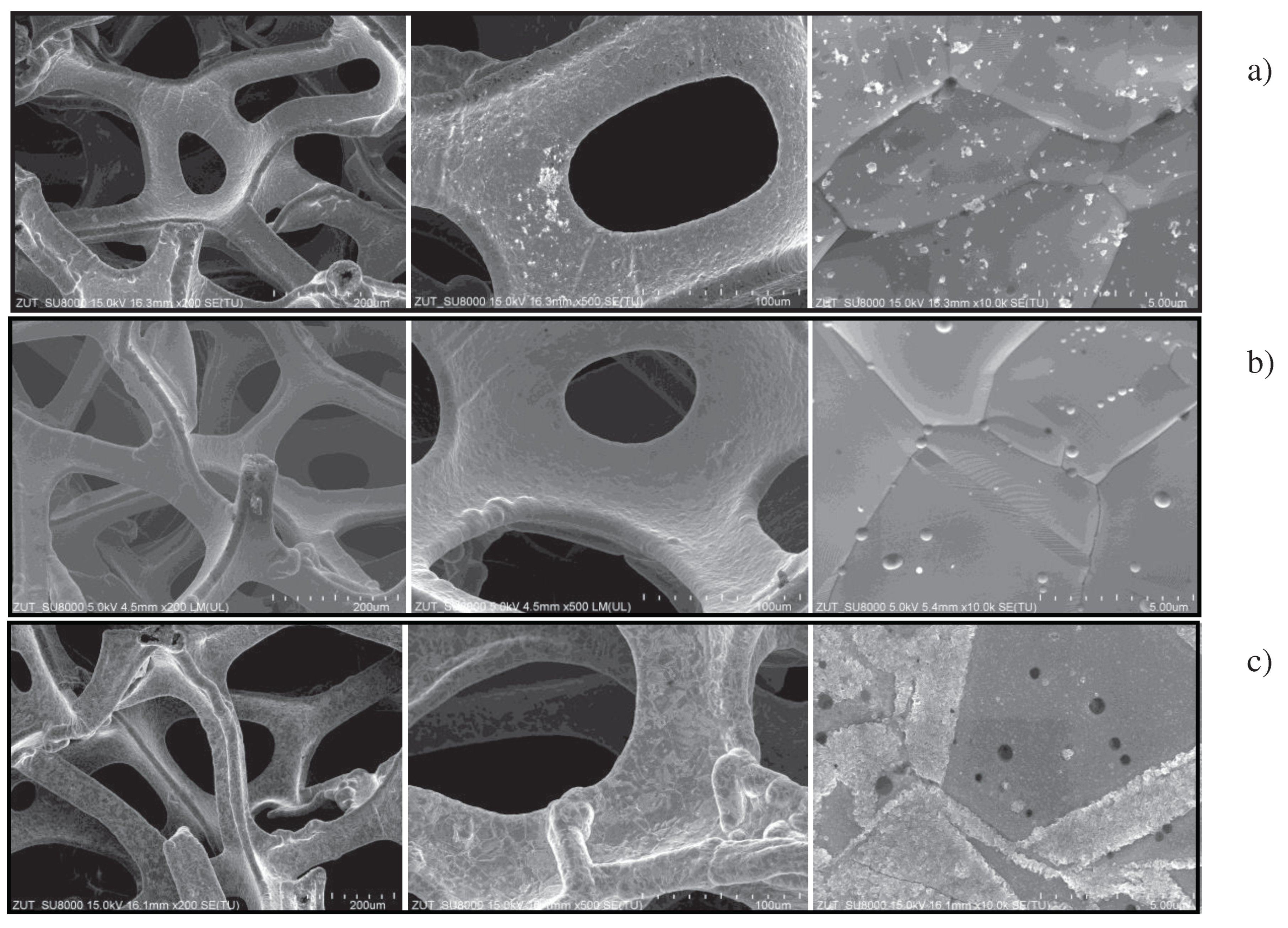

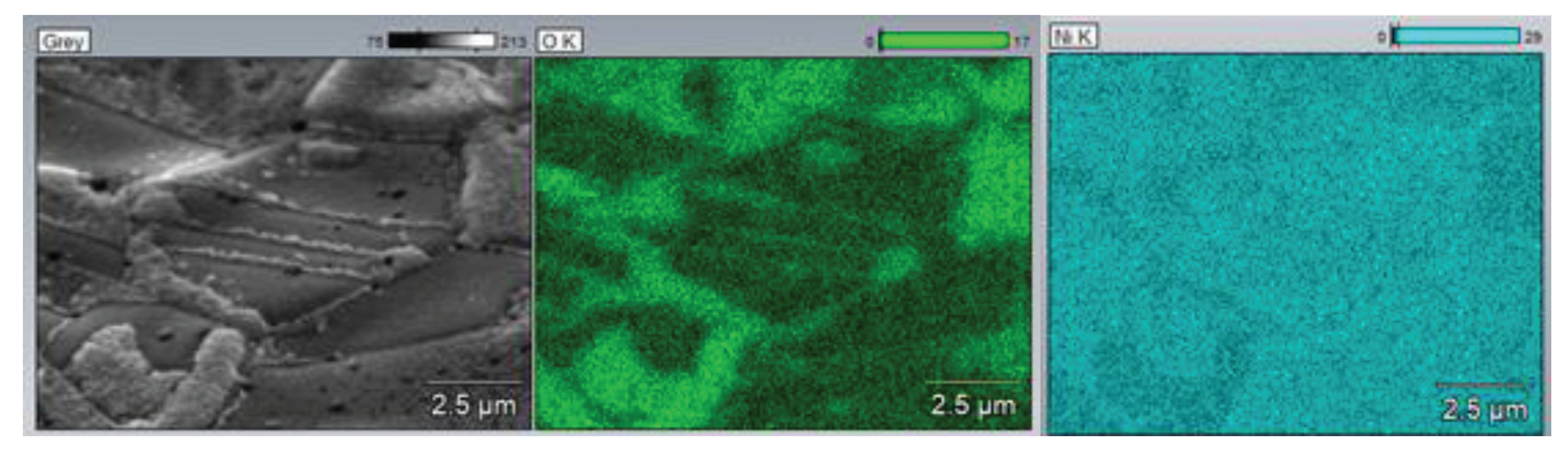

In

Figure 8 the SEM images of nickel foam are showed at different magnifications.

Performed SEM images showed some impurities on the surface of nickel foam, as received from the manufacturer (

Figure 8a). After photocatalytic process these impurities disappeared (

Figure 8b). The oxidized nickel foam showed corrugated surface on the grain fringes, indicating on the proceeding oxidation process.

In

Figure 9 mapping of the oxidized nickel foam was depicted. The green area indicates an oxygen distribution. It is clearly seen, that strongly corrugated surface covers with elemental oxygen.

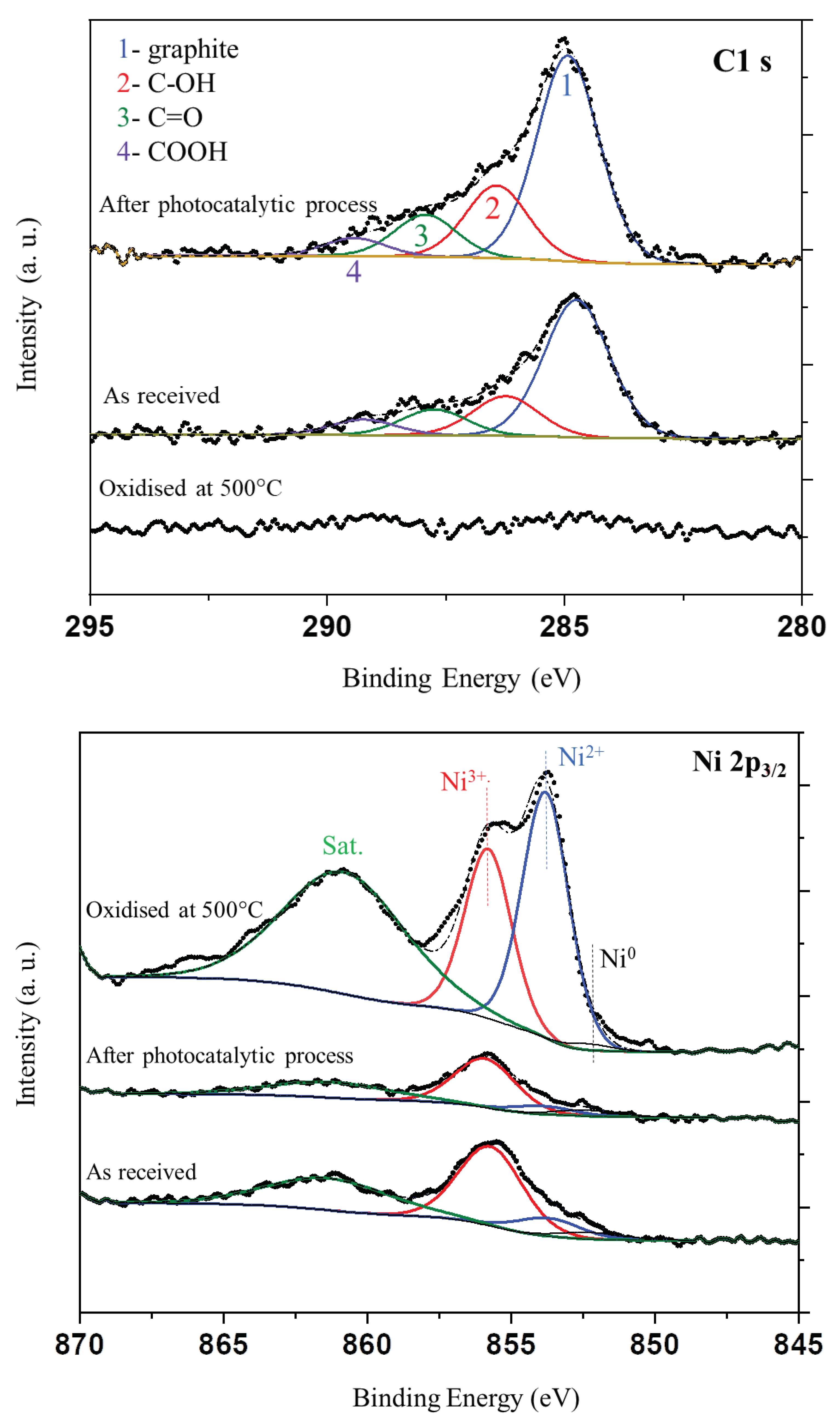

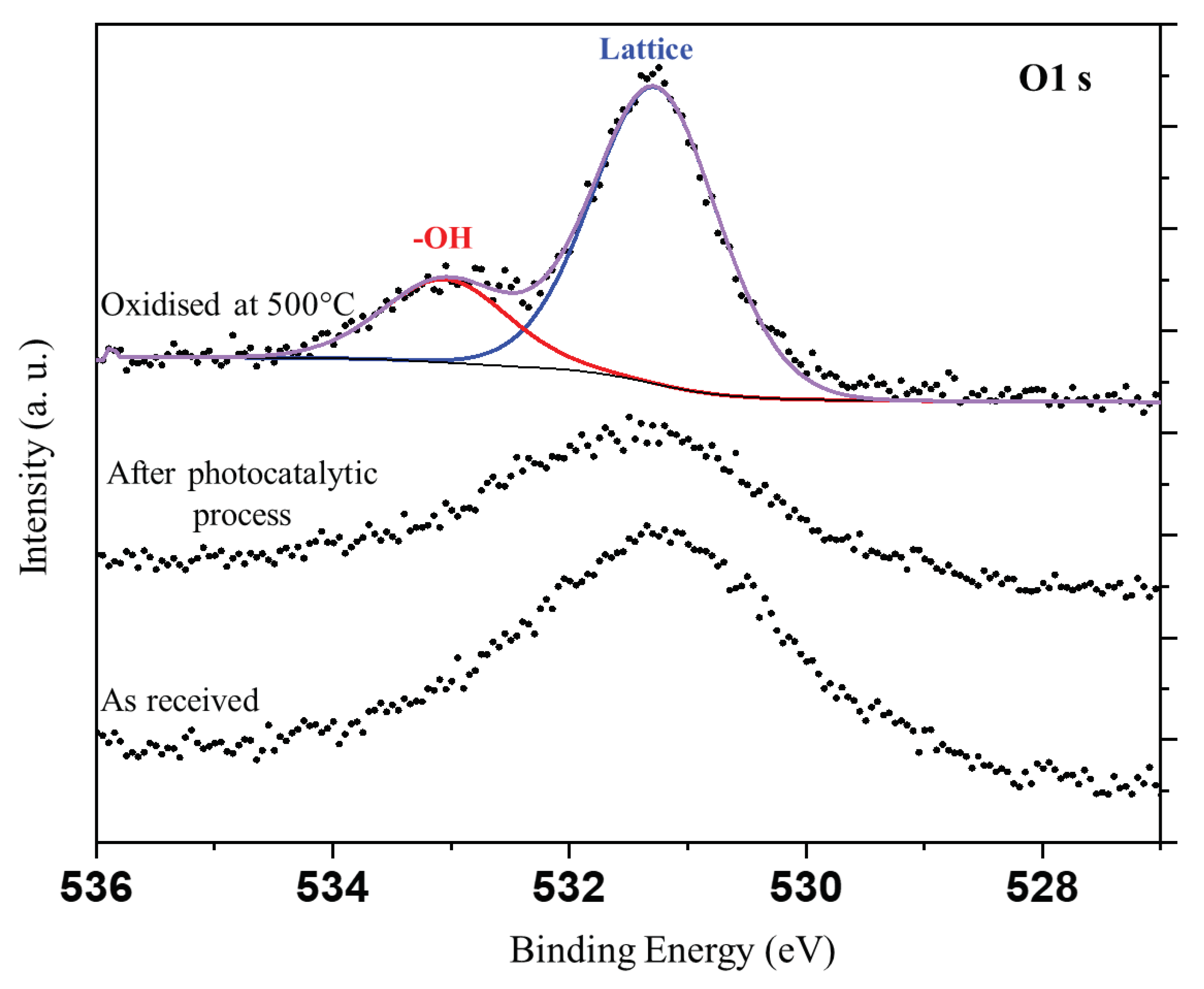

In the next step XPS analyses were performed for nickel foam as received (fresh), after photocatalytic process and that oxidized at 500

oC in air. Recorded XPS spectra for C1s, Ni2p

3/2 and O1s signals are presented in

Figure 10.

The elemental surface content from XPS analyses is presented in

Table 3.

It should be noted, that this is an average content of elements from depth of c.a. 1 nm with an assumption, that the elements are homogeneously distributed, which is not valid. Therefore these values should be taken as an approximation. The nickel foam oxidised at 500oC exhibit no carbon over the surface. The other nickel foams exhibit significant amount of carbon, which attenuates the Ni2p signal. This attenuation explains low values of Ni2p signals.

The deconvolution of C1s signal was performed on the basis of work [

31]. The carbon species were observed on not oxidized nickel foam before and after photocatalytic process. The prominent shoulder on the left-hand side of the signal is related with carbon-oxygen species present over the surface of carbon. The intensity of C1s signal increased after the process i.e. the carbon coverage has increased. However both samples showed similar composition of an oxygen carbon species.

XPS spectra of Ni 2p signals indicated, that the highest intensity of Ni species had sample oxidised at 500

oC. This can be attributed to absence of carbon over the surface of this sample. In case of other nickel foams the intensity of the Ni 2p signal was lower due to the carbon coverage, which attenuates the signal of Ni 2p. This signal can be deconvoluted to Ni

0, Ni

2+, Ni

3+ (852.3, 853.8 and 855.8 eV, respectively [

26]) and satellite signals. The signal of Ni

0 is negligible. The metallic Ni is present in the nickel foam, but the XPS sampling depth is c.a. 1 nm. Therefore the surface covered with oxides and carbon attenuates the signal from beneath. Nickel foam oxidized at 500

oC showed clearly signals related to Ni

2+ and Ni

3+, whereas, the other samples revealed mostly signal of Ni

3+.

The O1s can be unambiguously deconvoluted only for the sample oxidized at 500oC due to the absence of carbon. In case of other samples there are carbon-oxygen species, which contributes to O1s signal. This renders very difficult unambiguous deconvolution of the O1s spectrum. In case of the sample oxidised at 500oC two distinct components can be observed. One can be attributed to bulk nickel oxide and the other to the –OH groups present over the surface of nickel oxide. It is assumed, that a thin layer of Ni(oxy)hydroxide was formed on the surface of oxidized nickel foam.

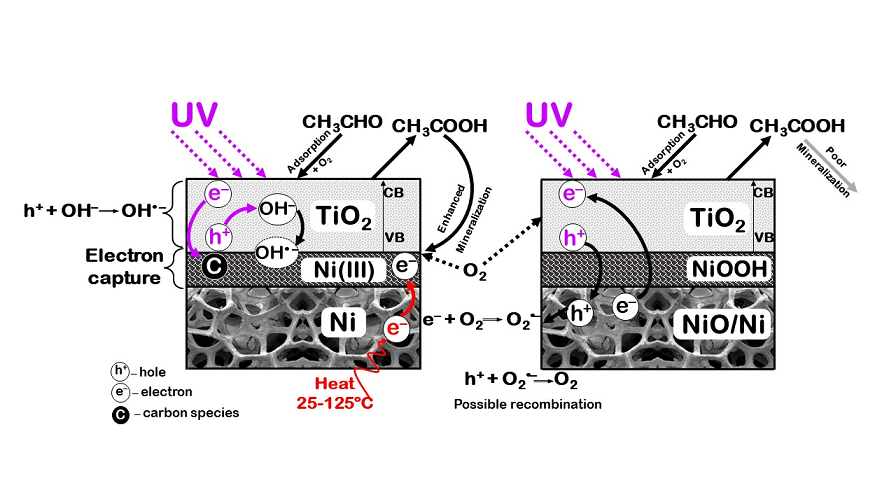

4. Discussion

Nickel foam used as a support for TiO

2 showed spectacular properties for enhancement the photocatalytic decomposition of acetaldehyde under UV light irradiation. However, doping of the nanosized Ni particles to TiO

2 did not bring any advantages in either acetaldehyde decomposition nor mineralisation. Partly oxidized nickel foam also deteriorated the rate of acetaldehyde removal from a gas stream, although some other researchers indicated superiority of the oxidised nickel foam over that not oxidised [

25]. These different properties of nickel materials could be explained by various reaction mechanisms occurred at the presence of TiO

2. Nanosized nickel after excitation can generate electrons, which can be transferred to the conductive band of TiO

2 or to the adsorbed species on its surface. From the other hand, the lifetime of these electrons is very short and they can undergo back transfer with heat generation. In case of oxidised Ni foam, there is also high probability of electron injection from the conductive band of NiO through the electron transfer zone – Ni (oxy)hydroxide to the TiO

2 due to the p-n heterojunction mechanism between these two semiconductors [

32]. In such case, holes from the titania valence band can migrate to the lower energy valence band of NiO, decreasing possibility of hydroxyl radicals formation on TiO

2 surface, which are engaged in the mineralisation of organic compounds. Therefore very low mineralisation degree of acetaldehyde was observed for TiO

2 supported on the oxidised Ni foam. In case of not oxidised nickel foam, there is a low probability of electrons injection to the titania conductive band, due to the its other morphology, than the single Ni particles. There is a synergistic effect of combination TiO

2 with a nickel foam leading to the improved separation of charge carriers. Such phenomenon has been already described in the other research papers [

28,

33]. The other researchers proved an improvement of charge carriers separation through the detection of hydroxyl radicals and superoxide anion radicals under UV irradiation at the presence of nickel foam and Ni-MOF photocatalyst [

28]. XPS measurements showed, that there is a thin layer of Ni (oxy)hydroxide formed on the surface of oxidised Ni foam. This layer can facilitate an interfacial electron transfer [

34]. It is assumed, that the presence of this layer caused acceleration of electrons transfer from NiO to TiO

2. Not oxidised Ni foam exhibited some carbon species on the surface before and after photocatalytic process. Some impurities were observed on the surface of commercial Ni foam, which have disappeared after its use for the acetaldehyde decomposition. However XPS measurements indicated, that more carbonaceous species were present on the used Ni foam, than as receive. Some carbon deposits on Ni foam could be present due to the incomplete acetaldehyde decomposition. It is assumed, that these carbon species could act as an electron trap centres and contributed in the separation of charge carriers in TiO

2. In fact, process of acetaldehyde decomposition on the used Ni foam was much more efficient, than on the fresh one. Increase concentration of electrons on Ni foam facilitated adsorption of molecular oxygen and then superoxide anion radicals could be formed. Collecting of electrons on the surface of nickel foam could enhance mobility of holes in TiO

2 and can contribute in lag of e

-/h

+ pairs recombination. Holes take place in oxidation of acetaldehyde to acetic acid at the presence of air, according to the reaction:

The carbonyl radicals (CH

3CO

•) are capable to react with O

2, which mediates the chain reactions of acetaldehyde oxidation, whereas formed acetic acid can undergo decomposition through the reaction with hydroxyl radicals [

35]:

Hydroxyl radicals can be formed by the reaction of holes with surface adsorbed hydroxyl ions:

or in a double-electron oxygen reduction pathway [

33]:

The other route od hydroxyl radicals formation can be through the single-electron reduction, conducted to formation superoxide anion radicals, which in further steps give yield in H

2O

2 production:

If the stored electrons in a nickel foam are engaged in formation of superoxide anion radicals or hydrogen peroxide species, then mineralisation of acetaldehyde is speeding up. As a consequence, formed on titania surface products of acetaldehyde conversion are faster removed, remaining the active sites free for new acetaldehyde molecules. In that way both, conversion and mineralisation of acetaldehyde are enhanced.

This process can be enhanced at the elevated temperature. It is assumed, that in the increased temperature higher quantity of H2O2 species are formed due to the increased mobility of electrons in the Ni conductive foam. Both, H2O2 species and formed upon its reduction hydroxyl radicals can take part in oxidation acetaldehyde and its conversion products. Therefore at the presence of Ni foam mineralisation degree of acetaldehyde was greatly enhanced.

The other researchers reported increased decomposition of acetaldehyde on TiO

2 doped with 0.5 % of Pt due to the spillover of oxygen from Pt to TiO

2 surface, which could oxidise byproducts of acetaldehyde conversion [

17].

The other situation was noted in case of Au doped TiO

2, where, Au particles served as the active adsorption centres for acetaldehyde [

36]. In that case Au nanoparticles oxidised acetaldehyde to acetic acid and then dissociated ions of acetate were transferred to TiO

2 surface, where underwent photochemical decomposition.

However, these studies showed, that doping of nanosized Ni species to TiO2 did not enhanced its photocatalytic activity, even at elevated temperature. Possible direct transfer of electrons from dopant to TiO2 could be detrimental for this process.

Mechanism of electron transfer between nickel material and TiO2 was important to obtain an increased efficiency of acetaldehyde decomposition. In this case nickel foam with some adsorbed carbon oxygen species on its surface was suitable, because enhanced separation of free carriers and acetaldehyde mineralisation.

5. Conclusions

Performed studies on thermo-photocatalytic decomposition of acetaldehyde showed superior properties of nickel foam used as a support for TiO2. It was evidenced, that nickel foam could improve photocatalytic properties of TiO2 for acetaldehyde conversion at room temperature form 31 to 52% and at 100oC from 40 to 85% with double increase of mineralisation degree. Even at lower temperature, such as 50oC conversion of acetaldehyde on TiO2 supported on nickel foam was high, because reached 80% (for TiO2 itself maximal conversion of acetaldehyde was obtained at 75 oC with value of 46%). These results indicate on the synergistic effect between nickel foam and TiO2, which can be utilised also in the other photocatalytic reactions, because charge separation in TiO2 is a key factor, responsible for its photocatalytic activity. Using nickel foam as a support for TiO2 gives high space for interaction of species between the interface boarder, therefore high enhancement of the photocatalytic yield was observed. Preparation of photocatalytic composites based on the nickel foam creates new direction of materials development.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, grant nr 2020/39/B/ST8/01514.

References

- Czelej, K.; Colmenares, J.C.; Jabłczyńska, K.; Ćwieka, K.; Werner, Ł.; Gradoń, L. Sustainable Hydrogen Production by Plasmonic Thermophotocatalysis. Catalysis Today 2021, 380, 156–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, D.; Cerrillo, J.L.; Durini, S.; Gascon, J. Fundamentals and Applications of Photo-Thermal Catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 2173–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, V.; Muñoz-Batista, M.J.; Fernández-García, M.; Luque, R.; Colmenares, J.C. Thermo-Photocatalysis: Environmental and Energy Applications. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 2098–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; He, S.; Guo, W.; Hu, Y.; Huang, J.; Mulcahy, J.R.; Wei, W.D. Surface-Plasmon-Driven Hot Electron Photochemistry. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 2927–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Choudhary, P.; Kumar, A.; Camargo, P.H.C.; Krishnan, V. Recent Advances in Plasmonic Photocatalysis Based on TiO 2 and Noble Metal Nanoparticles for Energy Conversion, Environmental Remediation, and Organic Synthesis. Small 2022, 18, 2101638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; He, Y.; Xin, J.; Wang, S.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z. Gold Nanoparticle Mediated Phototherapy for Cancer. Journal of Nanomaterials 2016, 2016, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adleman, J.R.; Boyd, D.A.; Goodwin, D.G.; Psaltis, D. Heterogenous Catalysis Mediated by Plasmon Heating. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 4417–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Xu, Q.; Yu, S.-H.; Jiang, H.-L. Pd Nanocubes@ZIF-8: Integration of Plasmon-Driven Photothermal Conversion with a Metal-Organic Framework for Efficient and Selective Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3685–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Huang, Y.; Chai, Z.; Zeng, M.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D. Photothermal-Enhanced Catalysis in Core–Shell Plasmonic Hierarchical Cu7S4 Microsphere@zeolitic Imidazole Framework-8. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 6887–6893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikawa, T.; Naya, S.; Kimura, T.; Tada, H. Rapid Removal and Subsequent Low-Temperature Mineralization of Gaseous Acetaldehyde by the Dual Thermocatalysis of Gold Nanoparticle-Loaded Titanium(IV) Oxide. Journal of Catalysis 2015, 326, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, T.; Ohwaki, T.; Suzuki, K.; Moribe, S.; Tero-Kubota, S. Visible-Light-Induced Photocatalytic Oxidation of Carboxylic Acids and Aldehydes over N-Doped TiO2 Loaded with Fe, Cu or Pt. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2008, 83, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ye, L.; Ma, Z.; Han, C.; Wang, L.; Jia, Z.; Su, F.; Xie, H. Photothermal Effect of Infrared Light to Enhance Solar Catalytic Hydrogen Generation. Catalysis Communications 2017, 102, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Swearer, D.F.; Zhang, C.; Robatjazi, H.; Zhao, H.; Henderson, L.; Dong, L.; Christopher, P.; Carter, E.A.; Nordlander, P.; et al. Quantifying Hot Carrier and Thermal Contributions in Plasmonic Photocatalysis. Science 2018, 362, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarina, S.; Zhu, H.-Y.; Xiao, Q.; Jaatinen, E.; Jia, J.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Wu, H. Viable Photocatalysts under Solar-Spectrum Irradiation: Nonplasmonic Metal Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 2935–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.-J.; Mun, H.-J.; Kim, B.-J.; Kim, Y.-S. Characterization of Nickel Oxide Nanoparticles Synthesized under Low Temperature. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.; Tachikawa, T.; Kim, H.; Lakshminarasimhan, N.; Murugan, P.; Park, H.; Majima, T.; Choi, W. Visible Light Photocatalytic Activities of Nitrogen and Platinum-Doped TiO2: Synergistic Effects of Co-Dopants. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2014, 147, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, J.L.; Magrini-Bair, K.A. Photocatalytic and Thermal Catalytic Oxidation of Acetaldehyde on Pt/TiO2. Journal of Catalysis 1998, 179, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M.; Ochiai, T.; Listiani, P.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Ichikawa, Y. Low-Temperature Synthesis of Cu-Doped Anatase TiO2 Nanostructures via Liquid Phase Deposition Method for Enhanced Photocatalysis. Materials 2023, 16, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sano, T.; Negishi, N.; Uchino, K.; Tanaka, J.; Matsuzawa, S.; Takeuchi, K. Photocatalytic Degradation of Gaseous Acetaldehyde on TiO2 with Photodeposited Metals and Metal Oxides. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2003, 160, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Xie, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, G.; Pui, D.Y.H.; Sun, J. Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance of Ag@TiO2 for the Gaseous Acetaldehyde Photodegradation under Fluorescent Lamp. Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 341, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Xie, X.; Chen, S.-C.; Tong, S.; Lu, G.; Pui, D.Y.H.; Sun, J. Cu-Ni Nanowire-Based TiO2 Hybrid for the Dynamic Photodegradation of Acetaldehyde Gas Pollutant under Visible Light. Applied Surface Science 2017, 408, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, G.; Xu, X.; Chen, X.; Deng, S.; Smirnov, S.; Luo, H.; Zou, G. Direct Growth of Mesoporous Anatase TiO2 on Nickel Foam by Soft Template Method as Binder-Free Anode for Lithium-Ion Batteries. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 48938–48942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, G.; Li, H.; Konkin, A.; Sun, Z.; Sun, S.; Wang, D.; Schaaf, P. Plasma Hydrogenated TiO2 /Nickel Foam as an Efficient Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Overall Water Splitting. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, F.; Chang, X.; He, D. Comparison of Nickel Foam/Ag-Supported ZnO, TiO2, and WO3 for Toluene Photodegradation. Materials and Manufacturing Processes 2014, 29, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Xiao, W.; Yuan, J.; Shi, J.; Chen, M.; Shang Guan, W. Preparations of TiO2 Film Coated on Foam Nickel Substrate by Sol-Gel Processes and Its Photocatalytic Activity for Degradation of Acetaldehyde. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2007, 19, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Chen, J.; Wan, Y.; Ni, J.; Ni, C.; Chen, H. Immobilizing TiO2 on Nickel Foam for an Enhanced Photocatalysis in NO Abatement under Visible Light. J Mater Sci 2022, 57, 15722–15736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Li, D.; Cheng, X.; Wan, J.; Yu, X. Construction of Graphite/TiO2/Nickel Foam Photoelectrode and Its Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. Applied Catalysis A: General 2016, 525, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Wen, M.; Li, G.; An, T.; Zhao, H. In Situ Growth of Well-Aligned Ni-MOF Nanosheets on Nickel Foam for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Typical Volatile Organic Compounds. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 9462–9470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Xiao, W.; Yuan, J.; Shi, J.; He, D.; Shangguan, W. High Photocatalytic Activity and Stability for Decomposition of Gaseous Acetaldehyde on TiO2/Al2O3 Composite Films Coated on Foam Nickel Substrates by Sol-Gel Processes. J Sol-Gel Sci Technol 2008, 45, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryba, B.; Rychtowski, P.; Srenscek-Nazzal, J.; Przepiorski, J. The Inflence of TiO2 Structure on the Complete Decomposition of Acetaldehyde Gas. Materials Research Bulletin 2020, 126, 110816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gęsikiewicz-Puchalska, A.; Zgrzebnicki, M.; Michalkiewicz, B.; Narkiewicz, U.; Morawski, A.W.; Wrobel, R.J. Improvement of CO2 Uptake of Activated Carbons by Treatment with Mineral Acids. Chemical Engineering Journal 2017, 309, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Zhao, H.; Wang, S.; Hu, J.; Chen, Z. NiO-TiO2 p-n Heterojunction for Solar Hydrogen Generation. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Shao, P.; Yuan, Y.; Shi, W.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, B.; Bao, X.; Cui, F. Monolithic Nickel Foam Supported Macro-Catalyst: Manipulation of Charge Transfer for Enhancement of Photo-Activity. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 418, 129456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.; Luo, J.; Zhang, X.; Subramanian, P.; Fransaer, J. In-Situ Formation of Ni (Oxy)Hydroxide on Ni Foam as an Efficient Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Evolution Reaction. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 8490–8496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitchaimuthu, S.; Honda, K.; Suzuki, S.; Naito, A.; Suzuki, N.; Katsumata, K.; Nakata, K.; Ishida, N.; Kitamura, N.; Idemoto, Y.; et al. Solution Plasma Process-Derived Defect-Induced Heterophase Anatase/Brookite TiO2 Nanocrystals for Enhanced Gaseous Photocatalytic Performance. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikawa, T.; Naya, S.; Tada, H. Rapid Removal and Decomposition of Gaseous Acetaldehyde by the Thermo- and Photo-Catalysis of Gold Nanoparticle-Loaded Anatase Titanium(IV) Oxide. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2015, 456, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).