Submitted:

22 June 2023

Posted:

23 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of the Study and Participants

- -

- age >18 years old

- -

- TBI diagnosis

- -

- Admission to ICU

- -

- age <18 years

- -

- history of allergy to Cerebrolysin

- -

- acute renal failure

- -

- pregnancy

- -

- multi organ trauma

- -

- death within 48 hours after admission.

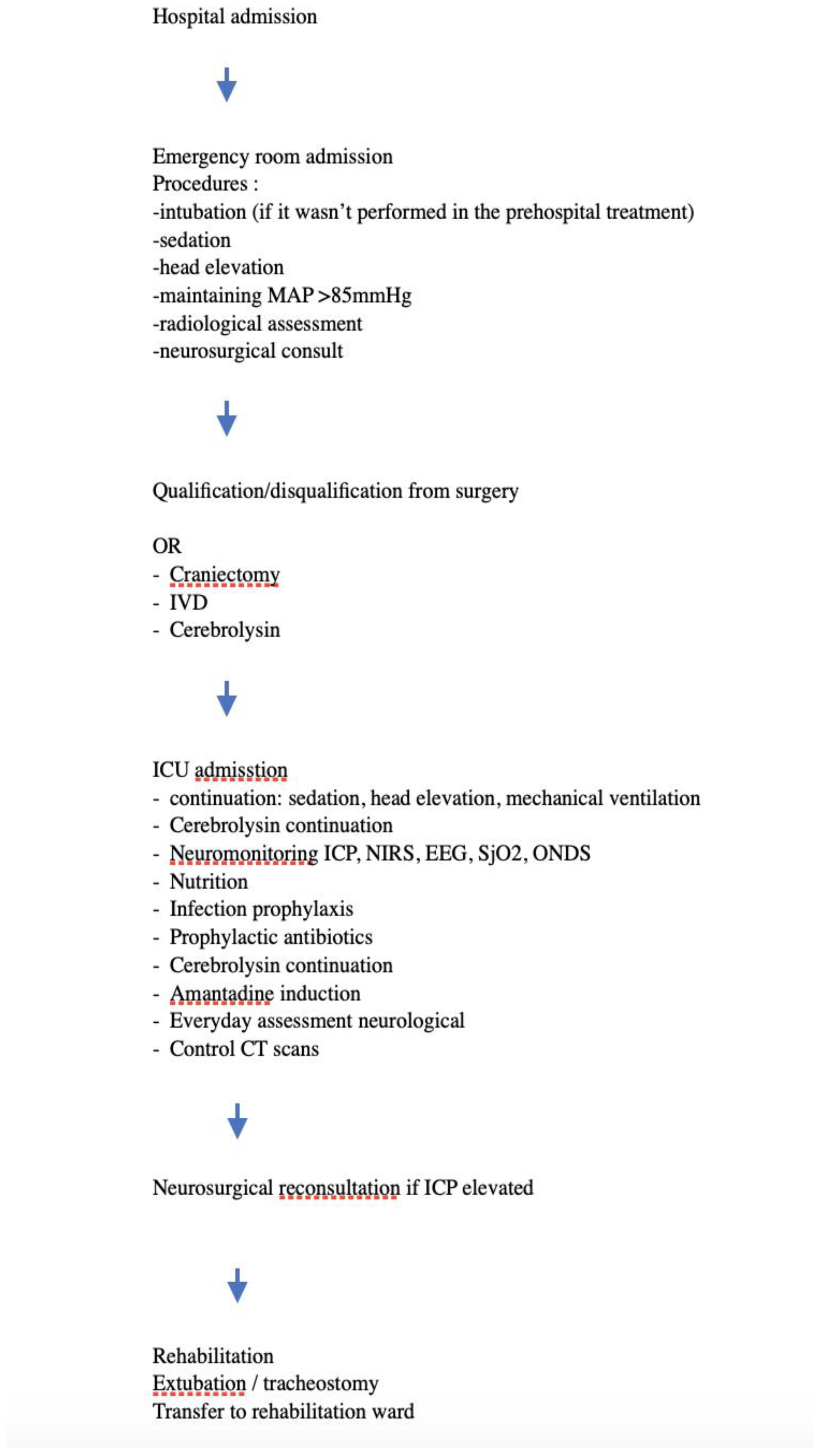

2.2. Clinical Management

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical statement:

2.6. Clinical trials registry number: NCT05807503

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics:

| GCS | GCS | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | 6 | 10,90% |

| Moderate | 8 | 14,50% |

| Severe | 42 | 74,50% |

| GCS | Severe/ not severe | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| <8 | Severe | 41 | 74,5 |

| >8 | Not severe | 14 | 25,5 |

3.2. Patients treatment efficacy.

| Amantadine | |||

| GCS_qualitatively | NO | YES | p |

| not severe | 11 | 3 | 0.55 |

| severe | 35 | 6 | |

| Cerebrolysin | |||

| GCS_qualitatively | NO | YES | p |

| not severe | 9 | 5 | 0.49 |

| severe | 22 | 19 | |

| Cerebrolysin | |||

| GCS_qualitatively | NO | YES | p |

| not severe | 0 | 14 | 0.40 |

| severe | 2 | 39 | |

| Monitoring | |||

| GCS_qualitatively | NO | YES | p |

| not severe | 10 | 4 | 0.82 |

| severe | 28 | 13 | |

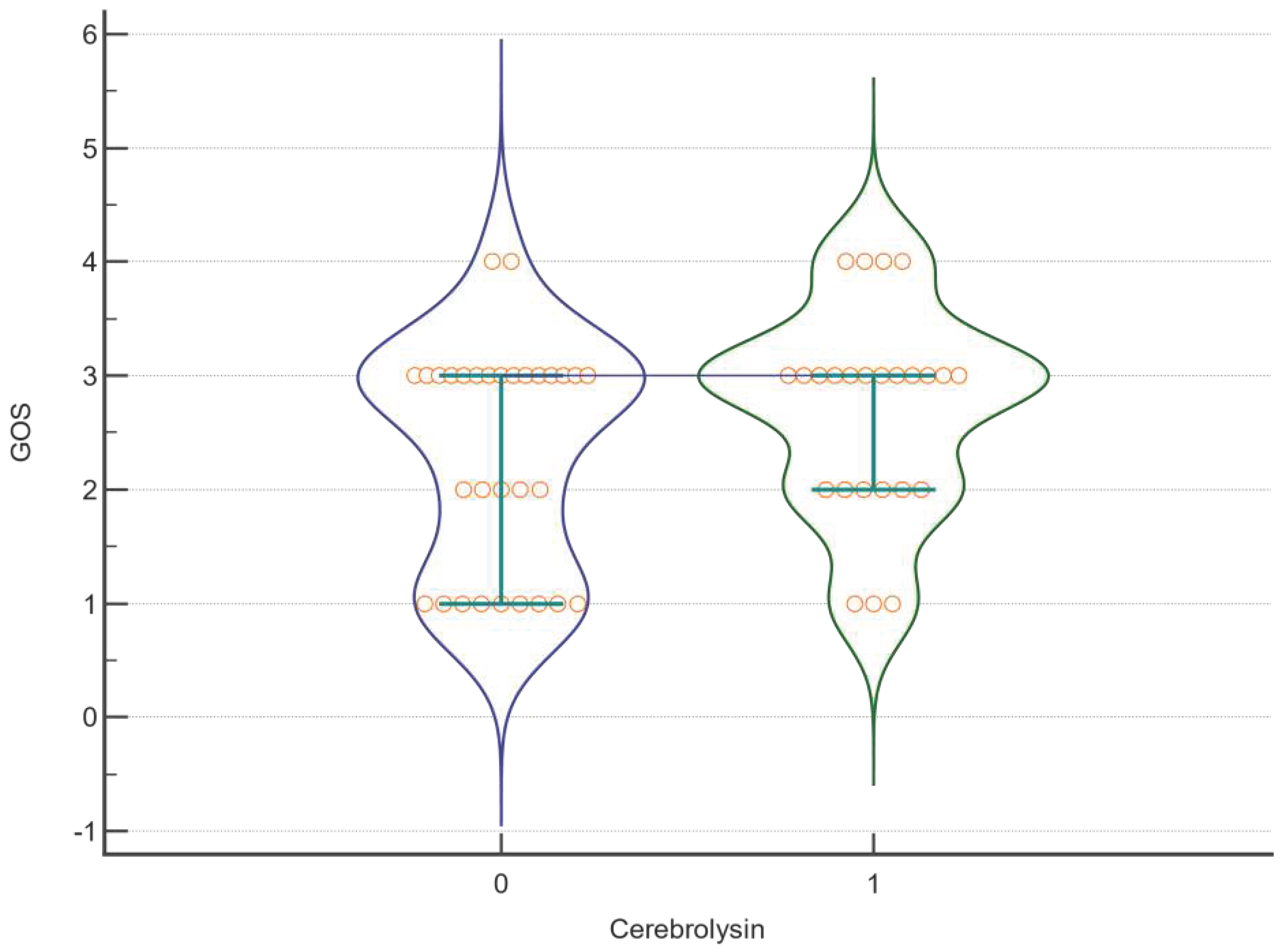

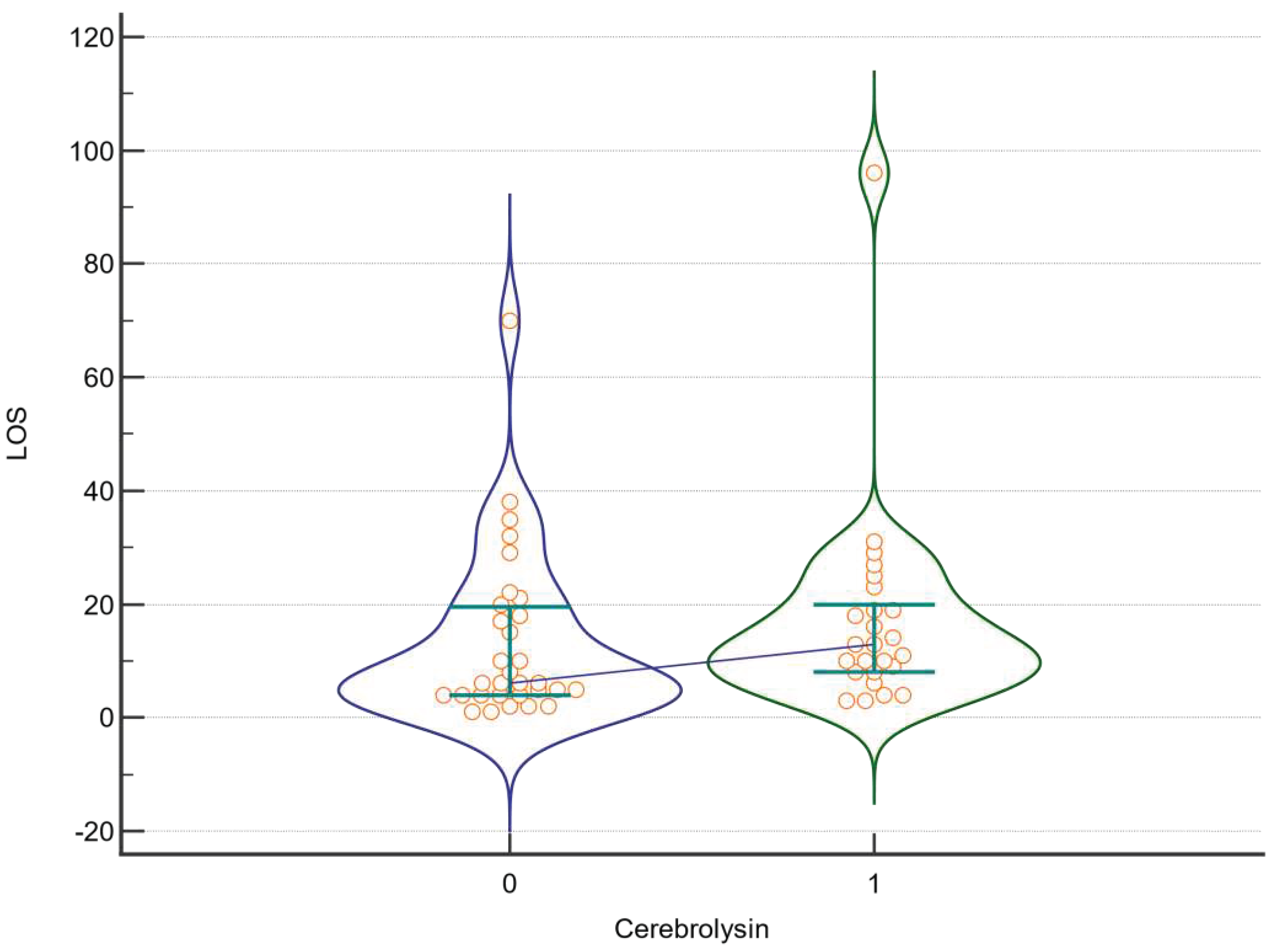

3.3. Data analysis

| Factor | DF | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| GOS | |||

| Cerebrolysin | 1 | 0,795 | <0,001 |

| Amantadine | 1 | 0,000945 | <0,001 |

| Cerebrolysin *Amantadine | 1 | 0,341 | <0,001 |

| Cerebrolysin | 1 | 0,0391 | <0,001 |

| Craniectomy | 1 | 0,722 | <0,001 |

| Cerebrolysin *Craniectomy | 1 | 0,0391 | <0,001 |

| Cerebrolysin | 1 | 0,745 | <0,001 |

| Monitoring | 1 | 0,3 | <0,001 |

| Cerebrolysin *Monitoring | 1 | 2,048 | <0,001 |

| LOS | |||

| Cerebrolysin | 1 | 0,657 | 0,421 |

| Amantadine | 1 | 0,074 | 0,787 |

| Cerebrolysin *Amantadine | 1 | 0,105 | 0,748 |

| Cerebrolysin | 1 | 0,00753 | 0,931 |

| Craniectomy | 1 | 0,176 | 0,677 |

| Cerebrolysin *Craniectomy | 1 | 0,555 | 0,46 |

| Cerebrolysin | 1 | 0,0523 | 0,82 |

| Monitoring | 1 | 0,147 | 0,703 |

| Cerebrolysin *Monitoring | 1 | 0,345 | 0,56 |

| Factor | DF | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| GOS | |||

| Cerebrolysin | Not estimable | ||

| Amantadine | |||

| Cerebrolysin *Amantadine | |||

| Cerebrolysin | |||

| Craniectomy | |||

| Cerebrolysin *Craniectomy | |||

| Cerebrolysin | 1 | 5,908 | 0,035 |

| Monitoring | 1 | 4,73 | 0,055 |

| Cerebrolysin *Monitoring | 1 | 0,0164 | 0,901 |

| LOS | |||

| Cerebrolysin | Not estimable | ||

| Amantadine | |||

| Cerebrolysin *Amantadine | |||

| Cerebrolysin | |||

| Craniectomy | |||

| Cerebrolysin *Craniectomy | |||

| Cerebrolysin | 1 | 2,793 | 0,126 |

| Monitoring | 1 | 2,65 | 0,135 |

| Cerebrolysin *Monitoring | 1 | 0,0796 | 0,784 |

| Variable | Whole group | Severe | Not severe | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebrolysin | NO | YES | p | NO | YES | p | NO | YES | p |

| ALIVE | 22 | 22 | 0.12 | 16 | 16 | 0.38 | 6 | 5 | 0.16 |

| DEAD | 9 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0 | |||

| Amantadine | NO | YES | p | NO | YES | p | NO | YES | p |

| ALIVE | 35 | 9 | 0.33 | 27 | 5 | 0.73 | 8 | 3 | 0.32 |

| DEAD | 11 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 0 | |||

| Craniectomy | NO | YES | p | NO | YES | p | NO | YES | p |

| ALIVE | 3 | 41 | 0.36 | 2 | 30 | 0.44 | 0 | 11 | n.e. |

| DEAD | 0 | 12 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 3 | |||

| Neuromonitoring | NO | YES | p | NO | YES | p | NO | YES | p |

| ALIVE | 29 | 15 | 0.55 | 21 | 11 | 0.49 | 8 | 3 | 0.84 |

| DEAD | 9 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Badhiwala, J.H.; Wilson, J.R.; Fehlings, M.G. Global burden of traumatic brain and spinal cord injury. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 1, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.Y.’ Lee, A.Y.W. Traumatic Brain Injuries: Pathophysiology and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 528. [CrossRef]

- Carney, N.; Totten, A.M.; O’Reilly, C.; Ullman, J.S.; Hawryluk, G.W.; Bell, M.J.; Bratton, S.L.; Chesnut, R.; Harris, O.A.; Kissoon, N.; Rubiano, A.M.; Shutter, L.; Tasker, R.C.; Vavilala, M.S.; Wilberger, J.; Wright, D.W.; Ghajar, J. Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury, Fourth Edition. Neurosurg. 2017, 1, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, L. M.; Chiu, Y.; , et al. Marked reduction in mortality in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg 2013, 119, 1583–1590. [CrossRef]

- Hawryluk, G.W.J.; Aguilera, S.; et al. A management algorithm for patients with intracranial pressure monitoring: the Seattle International Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Consensus Conference (SIBICC). Intensive Care Med 2019, 45, 1783–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazinova, A.; Rehorcikova, V.; et al. Epidemiology of Traumatic Brain Injury in Europe: A Living Systematic Review. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 1411–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, S.K.; Fook-Chong, S.; Teo, Q.Q. Demographics of traumatic brain injury and outcomes of continuous chain of early rehabilitation in Singapore. Proc. Singapore Healthc. 2020, 29, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, J.; Waltzman, D.; Sarmiento, K.; Xu, L. Traumatic Brain Injury-Related Deaths by Race/Ethnicity, Sex, Intent, and Mechanism of Injury - United States. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019, 22, 1050–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; van Veen, E.; et al. Comparison of care system and treatment approaches for patients with traumatic brain injury in China versus Europe: a CENTER-TBI survey study. Journal of neurotrauma 2020, 37, 1806–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiani, B.; Covarrubias, C.; Wong, A.; et al. Cerebrolysin for stroke, neurodegeneration, and traumatic brain injury: review of the literature and outcomes. Neurol Sci 2021, 42, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.S.; Chopp, M.; Zheng, G.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lu, M.; Zhang, T.M.S.; Winter, S.; Doppler, E.; Brandstaetter, H.; Mahmood, A.; Xiong, Y. Cerebrolysin Reduces Astrogliosis and Axonal Injury and Enhances Neurogenesis in Rats After Closed Head Injury. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair 2019, 33, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, D.; Li, X.; Luo, J.; Liao, X. Cerebrolysin alleviates early brain injury after traumatic brain injury by inhibiting neuroinflammation and apoptosis via TLR signaling pathway. Acta Cir. Bras. 2022, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, M.; Chopp, M.; Zhang, Z.G.; Melcher-Mourgas, M.; Fleckenstein, B. Therapeutic effect of Cerebrolysin on reducing impaired cerebral endothelial cell permeability. Neuroreport. 2021, 32, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascol, O.; Fabbri, M.; Poewe, W. Amantadine in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders. Lancet Neurol 2021, 20, 1048–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczyk, A.; Czajkowska-Malinowska, M.; Farnik, M.; Barczyk, M.; Boda, Ł.; Cofta, S.; Dulawa, J.; Dyrbus, M.; Harat, R.; Huk, M.; Kotecka, S.; Nahorecki, A.; Nasiłowski, J.; Naumnik, W.; Przybylski, G.; Słabon-Willand, M.; Skoczynski, S.; Wita, K.; Zioło, G.; Kuna, P. Efficacy of oral amantadine among patients hospitalised with COVID-19: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Respir Med. 2023, 212, 107198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodnar, W.; Aranda-Abreu, G.; Slabon-Willand, M.; Kotecka, S.; Farnik, M.; Bodnar, J. The ecacy of amantadine hydrochloride in the treatment of COVID-19 - a single-center observation study. Research Square 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Mona. Salah.; El Sayed, I.; Zaki, A.; Abdelmonem, S. Assessment of the effect of amantadine in patients with traumatic brain injury: A meta-analysis. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg 2022, 92, 605–614. [CrossRef]

- Andrea, Loggini.; Ruth, Tangonan.; Faten, E.l.A.; Ali, Mansour.; Fernando, D.; Goldenberg, C.L.; Kramer, C.L. The role of amantadine in cognitive recovery early after traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020, 194.

- Ruhatiya, R.S.; Adukia, S.A.; Manjunath, R.B.; Maheshwarappa, H.M. ; Current Status and Recommendations in Multimodal Neuromonitoring. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020, 24, 353–360. [Google Scholar]

- Roldán, M.; Kyriacou, P.A. Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) in Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). Sensors 2021, 21, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plomgaard, A. M., van Oeveren, W., Petersen, T. H., Alderliesten, T., Austin, T., van Bel, F., Benders, M., Claris, O., Dempsey, E., Franz, A., Fumagalli, M., Gluud, C., Hagmann, C., Hyttel-Sorensen, S., Lemmers, P., Pellicer, A., Pichler, G., Winkel, P., & Greisen, G. The SafeBoosC II randomized trial: treatment guided by near-infrared spectroscopy reduces cerebral hypoxia without changing early biomarkers of brain injury. Pediatric research 2016, 79, 528–535.

- Du, J.; Deng, Y.; Li, H.; Qiao, S.; Yu, M.; Xu, Q.; Wang, C. Ratio of Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter to Eyeball Transverse Diameter by Ultrasound Can Predict Intracranial Hypertension in Traumatic Brain Injury Patients: A Prospective Study. Neurocritical care 2020, 32, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munawar, K.; Khan, M. T.; Hussain, S. W.; Qadeer, A.; Shad, Z. S.; Bano, S.; Abdullah, A. Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter Correlation with Elevated Intracranial Pressure Determined via Ultrasound. Cureus 2019, 11, 4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volovici, V.; Huijben, J. A.; Ercole, A.; Stocchetti, N.; Dirven, C. M. F.; van der Jagt, M.; Steyerberg, E. W.; Lingsma, H. F.; Menon, D. K.; Maas, A. I. R.; Haitsma, I. K. Ventricular Drainage Catheters versus Intracranial Parenchymal Catheters for Intracranial Pressure Monitoring-Based Management of Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of neurotrauma. 2019, 36, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, G.; Jennet, B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. Lancet 1974, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, T.; Wilson, L.; Ponsford, J.; et al. The Glasgow Outcome Scale — 40 years of application and refinement. Nat Rev Neurol 2016, 12, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, P.; Rocha, E.E.M. Nutrition Therapy, Glucose Control, and Brain Metabolism in Traumatic Brain Injury: A Multimodal Monitoring Approach. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2020, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresanu, D.F.; Florian, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of cerebrolysin in neurorecovery after moderate-severe traumatic brain injury: results from the CAPTAIN II trial. Neurol Sci 2020, 41, 1171–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vester, J.C.; Buzoianu, A.D.; et al. Cerebrolysin after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: prospective meta-analysis of the CAPTAIN trial series. Neurol Sci 2021, 42, 4531–4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghi, E.; Binder, H.; Birle, C.; Bornstein, N.; Diserens, K.; Groppa, S.; Homberg, V.; Lisnic, V.; Pugliatti, M.; Randall, G.; Saltuari, L.; Strilciuc, S.; Vester, J.; Muresanu, D. European Academy of Neurology and European Federation of Neurorehabilitation Societies guideline on pharmacological support in early motor rehabilitation after acute ischaemic stroke. European journal of neurology. 2021, 28, 2831–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S,; Harnett, A,; Welch-West, P,; Ferri, C.; Janzen, S.; Togher, L.; Teasell, R.; Attention, Concentration and Information Processing Post Acquired Brain Injury. In Teasell R, Cullen N, Marshall S, Bayley M, Harnett A editors. Evidence-Based Review of Moderate to Severe Acquired Brain Injury. 2021, Version 14.0: p1-64. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Haeng, L. H.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J. Additive effect of cerebrolysin and amantadine on disorders of consciousness secondary to acquired brain injury: A retrospective case-control study. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2020, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, X. A.; Sampedro, C.; et al. Positive effects of Cerebrolysin on electroencephalogram slowing, cognition and clinical outcome in patients with postacute traumatic brain injury: an exploratory study. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2003, 18, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacino, J.T.; Whyte, J.; Bagiella, E.; Kalmar, K.; Childs, N.; Khademi, A.; Eifert, B.; Long, D.; Katz, D.I.; Cho, S.; Yablon, S.A.; Luther, M.; Hammond, F.M.; Nordenbo, A.; Novak, P.; Mercer, W.; Maurer-Karattup, P.; Sherer, M.; et al. Placebo-Controlled Trial of Amantadine for Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. N Engl J Med 2012, 366, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, C.; Raj, R.; Zeiler, F.A. Current state of high-fidelity multimodal monitoring in traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochir 2020, 164, 3091–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J. Protecting the brain from long term damage in Critical Care London. 2015, 13, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. Multimodality Neuromonitoring in Adult Traumatic Brain Injury: A Narrative Review. Anesthesiology 2018, 128, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).