1. Introduction

Analytic hyperbolic geometry is the hyperbolic geometry of Lobachevsky and Bolyai, studied analytically since 1988 [

1] in full analogy with the study of Euclidean geometry analytically [

2,

3,

4,

5]. In the analytic study of hyperbolic geometry, Einstein addition and Möbius addition capture analogies with vector addition as follows:

- (1)

Vector addition admits scalar multiplication, giving rise to vector spaces which, in turn, form the algebraic setting for analytic Euclidean geometry. In full analogy,

- (2)

Einstein addition (of relativistically admissible velocities) admits scalar multiplication, giving rise to Einstein gyrovector spaces which, in turn, form the algebraic setting for the Klein ball model of analytic hyperbolic geometry [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Accordingly, the Klein model of hyperbolic geometry is also known as the relativistic model of hyperbolic geometry [

8,

9]. Furthermore, in full analogy,

- (3)

Möbius addition [

10] admits scalar multiplication, giving rise to Möbius gyrovector spaces which, in turn, form the algebraic setting for the Poincaré ball model of analytic hyperbolic geometry [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

In the same way that the Euclidean vector plane admits trigonometry, each of Einstein gyrovector plane and Möbius gyrovector plane admits hyperbolic trigonometry, called gyrotrigonometry.

Ptolemy’s Theorem in Euclidean plane geometry, named after the Greek astronomer and mathematician Claudius Ptolemy, is well known.

- (1)

In [

8] we presented the well-known proof of Ptolemy’s Theorem in terms of the standard trigonometry of analytic Euclidean plane geometry. In particular, the associated

law of cosines was employed.

- (2)

In full analogy, in [

8] we discovered the hyperbolic Ptolemy’s Theorem in the Klein (relativistic) model of analytic hyperbolic plane geometry. The proof of the resulting hyperbolic Ptolemy’s Theorem is obtained by means of the gyrotrigonometry that the Klein model of analytic hyperbolic geometry admits. In particular, the associated

law of gyrocosines was employed.

- (3)

In full analogy, in this article we discover the hyperbolic Ptolemy’s Theorem in the Poincaré ball model of analytic hyperbolic plane geometry. The proof of the resulting hyperbolic Ptolemy’s Theorem is obtained by means of the gyrotrigonometry that the Poincaré model of analytic hyperbolic geometry admits. In particular, the associated law of gyrocosines is employed.

As a prerequisite for a fruitful reading of this article it is recommended familiarity with Ref. [

8], where important background about gyrogroups, gyrovector spaces and gyrotrigonometry is reviewed. In particular, the duality of trigonometry and gyrotrigonometry is reviewed and illustrated.

2. Möbius Addition and Scalar Multiplication

Let

be any positive constant and let

be the Euclidean

n-space,

, endowed with the common vector addition, +, and inner product, ·, and let

be the

s-ball given by

Möbius addition is a binary operation, ⊕, in the

s-ball

given by

where · and

are the inner product and the norm that the ball

inherits from its ambient space

[

10].

Note that in the Euclidean limit, , the s-ball expands to the whole of its ambient space , and Möbius addition tends to the common vector addition, , in .

Möbius addition in

,

, is neither commutative nor associative. Hence, the pair

does not form a group. However, it forms a

gyrocommutative gyrogroup as shown, for instance, in [

3,

4]. A gyrogroup is a group-like structure, a prominent concrete example of which is given by Einstein addition of relativistically admissible velocities studied, for instance, in [

3,

4,

8]. The elegant road from Möbius to gyrogroups is revealed in [

10].

The definition of gyrogroups, some of which are gyrocommutative, is presented, for instance, in [

3,

4,

7,

8].

Möbius addition, ⊕, admits scalar multiplication, ⊗, turning Möbius gyrogroups into Möbius gyrovector spaces

. Möbius scalar multiplication is given by ([

3] Sect. 8.12), ([

4], Sect. 6.14)

where

,

,

; and

.

Gyrovector spaces are generalized vector spaces, the definition of which is presented, for instance, in [

4,

8]. The resulting (i) Möbius gyrovector spaces form the algebraic setting for the Cartesian Poincaré ball model of analytic hyperbolic geometry, just as (ii) Einstein gyrovector spaces form the algebraic setting for the Cartesian Klein ball model of analytic hyperbolic geometry; and, just as (iii) vector spaces form the algebraic setting for the standard Cartesian model of analytic Euclidean geometry [

2].

Gyrovector planes admit hyperbolic trigonometry, called

gyrotrigonometry, just as vector planes admit the common trigonometry. The law of gyrocosines in the gyrotrigonometry of the Klein model of hyperbolic geometry is employed in [

8] for the proof of Ptolemy’s Theorem in the Klein model. Similarly, the law of gyrocosines in the gyrotrigonometry of the Poincaré ball model of hyperbolic geometry is employed in this article for the proof of Ptolemy’s Theorem in the Poincaré model.

3. Gyrotrigonometry in Möbius Gyrovector Planes and its

Law of Gyrocosines

Möbius addition and scalar multiplication enable Möbius

gyrolines to be expressed analytically in a way fully analogous to lines in analytic Euclidean geometry. The unique Euclidean line that passes through two distinct points

is given analytically by

. In full analogy, the unique Möbius gyroline that passes through two distinct points

in a Möbius gyrovector space

is given analytically by

, where

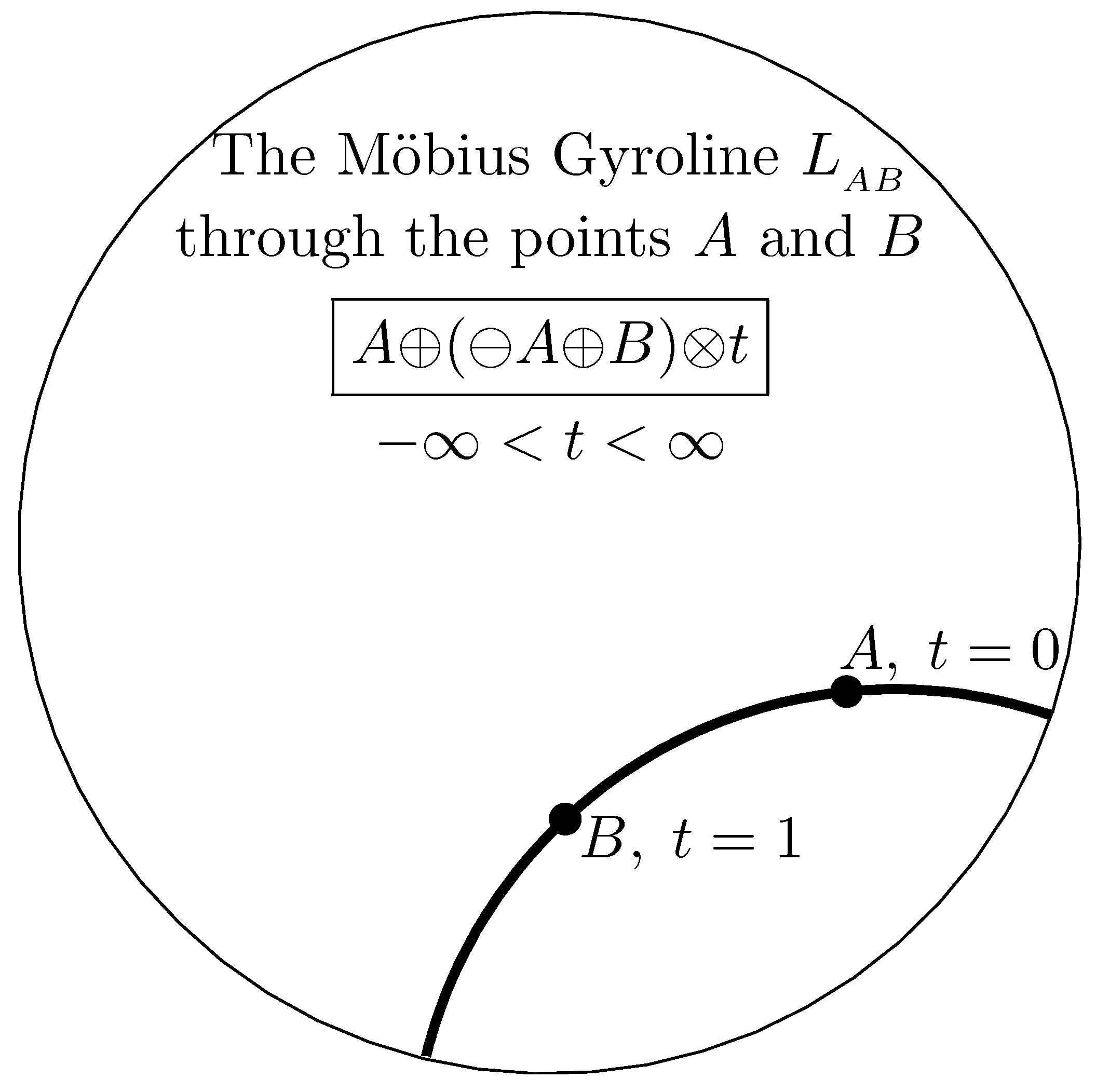

, depicted in

Figure 1 for

.

A Möbius gyroline (

5) is a circular arc that approaches the boundary of the

s-ball

orthogonally. It passes at the point

A when

, and at the point

B when

, and it forms a geodesic in the Poincaré ball model of hyperbolic geometry [

6].

The

gyrosegment that links the two distinct points

is given by (

5) with

. The

gyrolength of a gyrosegment

is

, just as the length of a segment

is

.

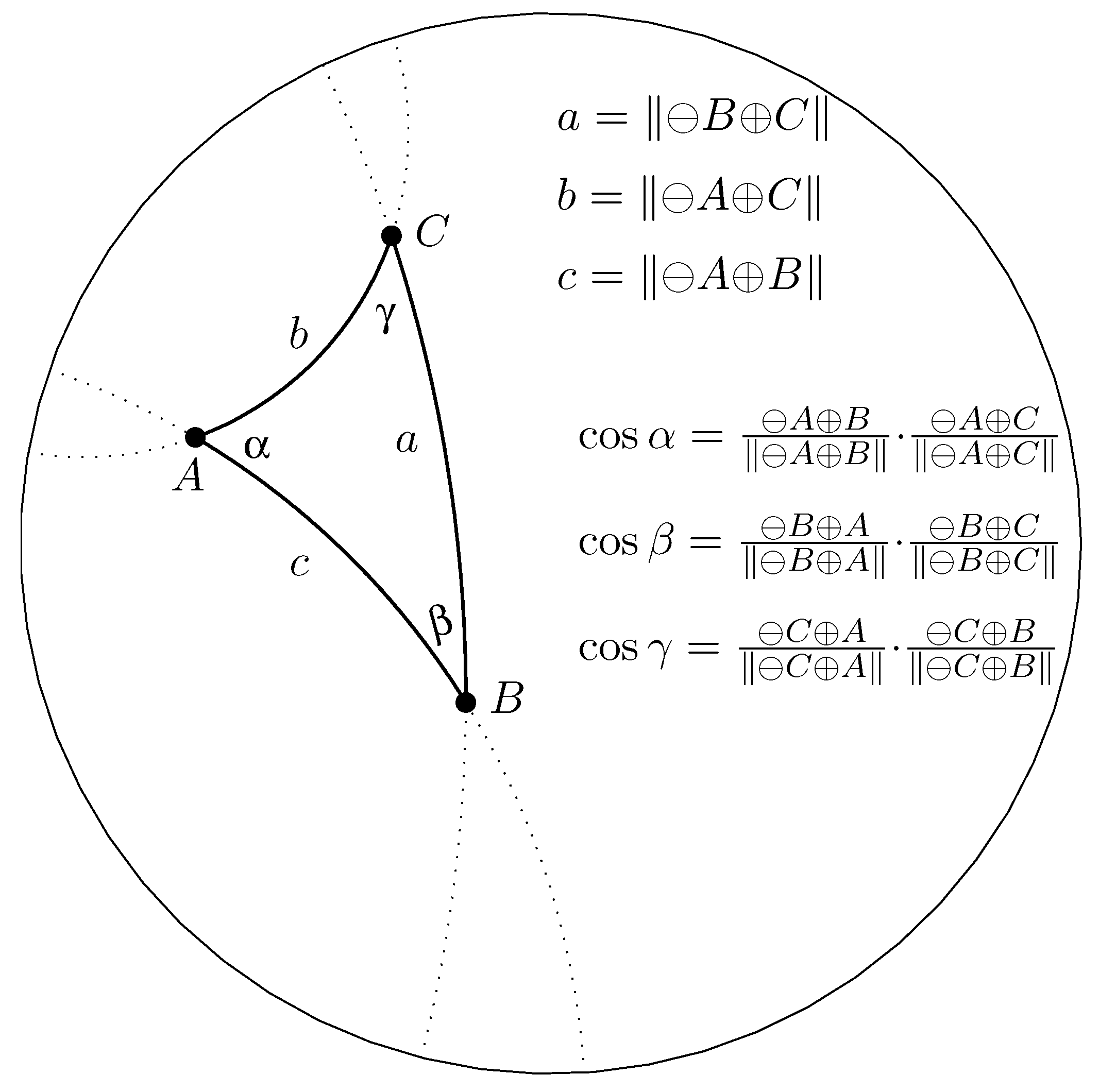

A gyrotriangle

whose gyrosides are the gyrosegments

,

and

in

, along with its gyroangles, is depicted in

Figure 2. The gyrolengths of the gyrosides of gyrotriangle

are

as shown in

Figure 2.

Gyrotrigonometry in Möbius gyrovector spaces is studied, for instance, in ([

4] Sect. 8.5). In gyrotrigonometry the gyrocosine of a gyroangle

, shown in

Figure 2, is given by

just as in trigonometry the cosine of an angle

, in the Euclidean counterpart of

Figure 2, is given by

Accordingly, viewing

trigonometrically yields (

10), while viewing

gyrotrigonometrically yields (

9). The resulting

trigonometry and gyrotrigonometry duality is illustrated in ([

8] Sect. 11). The usefulness of the analogies that (

5) and (

4) share suggests that the analogies that (

9) and (

10) share will prove useful as well. We will see in this article that this is, indeed, the case.

An important trigonometric identity that we will view gyrotrigonometrically as well is

for any

, where

. Identity (

11) can be realized not only trigonometrically (i) in the Euclidean plane, but also gyrotrigonometrically (ii) in the Einstein gyrovector plane, and (iii) in the Möbius gyrovector plane. These three distinct realizations of (

11) are consistent owing to the duality of trigonometry and gyrotrigonometry, as explained in [

8].

Indeed, (i) realizing (

11) in trigonometry gives rise to Ptolemy’s Theorem in Euclidean geometry, as shown in [

8]; (ii) realizing (

11) in Einstein gyrotrigonometry gives rise to Ptolemy’s Theorem in the Klein ball (relativistic) model of hyperbolic geometry, as shown in [

8]; and (iii) realizing (

11) in Möbius gyrotrigonometry gives rise to Ptolemy’s Theorem in the Poincaré ball model of hyperbolic geometry, as we will see in

Section 4.

Having the gyrotriangle notation in

Figure 2, we are now in the position to state the

law of gyrocosines in a Nöbius gyrovector plane, verified in ([

3] Sect. 8.4) and ([

4] Sect. 8.5).

Theorem 1.

(Law of gyrocosines in Möbius gyrovector spaces).Let be a gyrotriangle in a Möbius gyrovector plane with vertices , side gyrolengths , and gyroangles , as shown in Figure 2. Then, the gyrosides and gyroangles of the gyrotriangle satisfy the law of gyrocosines

and, equivalently,

where , , , with similar relations involving the other gyrosides and gyroangles of the gyrotriangle.

Note that in the Euclidean limit,

, the law of gyrocosines (

12) descends to the law of cosines,

as expected. Also, note that in the context of Euclidean geometry,

in (

14) is viewed trigonometrically, as in (

10), while in the context of hyperbolic geometry,

in (

12)-(

13) is viewed gyrotrigonometrically, as in (

9) and as shown in

Figure 2.

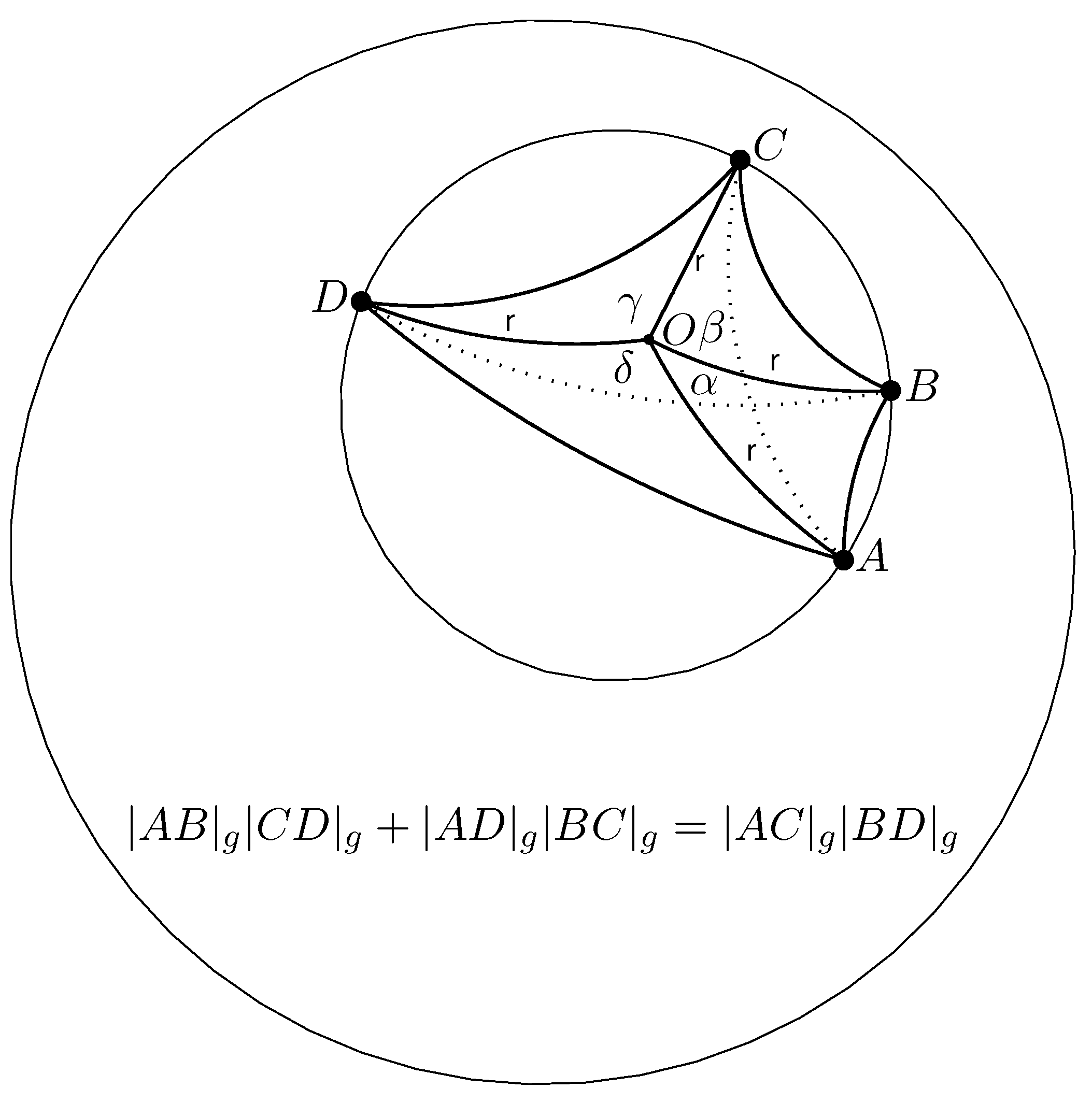

4. Ptolemy’s Theorem in the Poincaré Ball Model of Hyperbolic Geometry

Applying the law of gyrocosines (

13) to the

O-gyrovertex gyroangle

of gyrotriangle

, shown in

Figure 3, yields

noting that

and

in (

13) are, respectively, realized in (

15) by

and

.

We now employ the trigonometric and, hence, gyrotrigonometric identity

, obtaining from (

15) the equation

so that, finally,

where

, and where

is the Lorentz gamma factor of

, given by

Repeating the result in (

17) for the six

O-gyrovertex gyrotriangle gyroangles

,

,

,

,

, and

in

Figure 3 yields the following six equations

where

and so forth. We call

the g-modified gyrolength of gyroside

, and so forth.

Substituting (

19) into the gyrotrigonometric identity (

11) yields the result (

21) of Ptolemy’s Theorem in the Poincaré ball model of hyperbolic geometry.

Theorem 2.

(Ptolemy’s Theorem in the Poincaré Ball Model of Hyperbolic Geometry).Let be a gyrocyclic gyroquadrilateral, shown in Figure 3. Then, the product of the g-modified gyrodiagonals equals the sum of the products of the g-modified opposite gyrosides, that is

Clearly, in the Euclidean limit,

, the hyperbolic Ptolemy’s Theorem (

21) descends to its Euclidean counterpart, studied in [

8].

5. Gyrodiametric Gyrotriangles

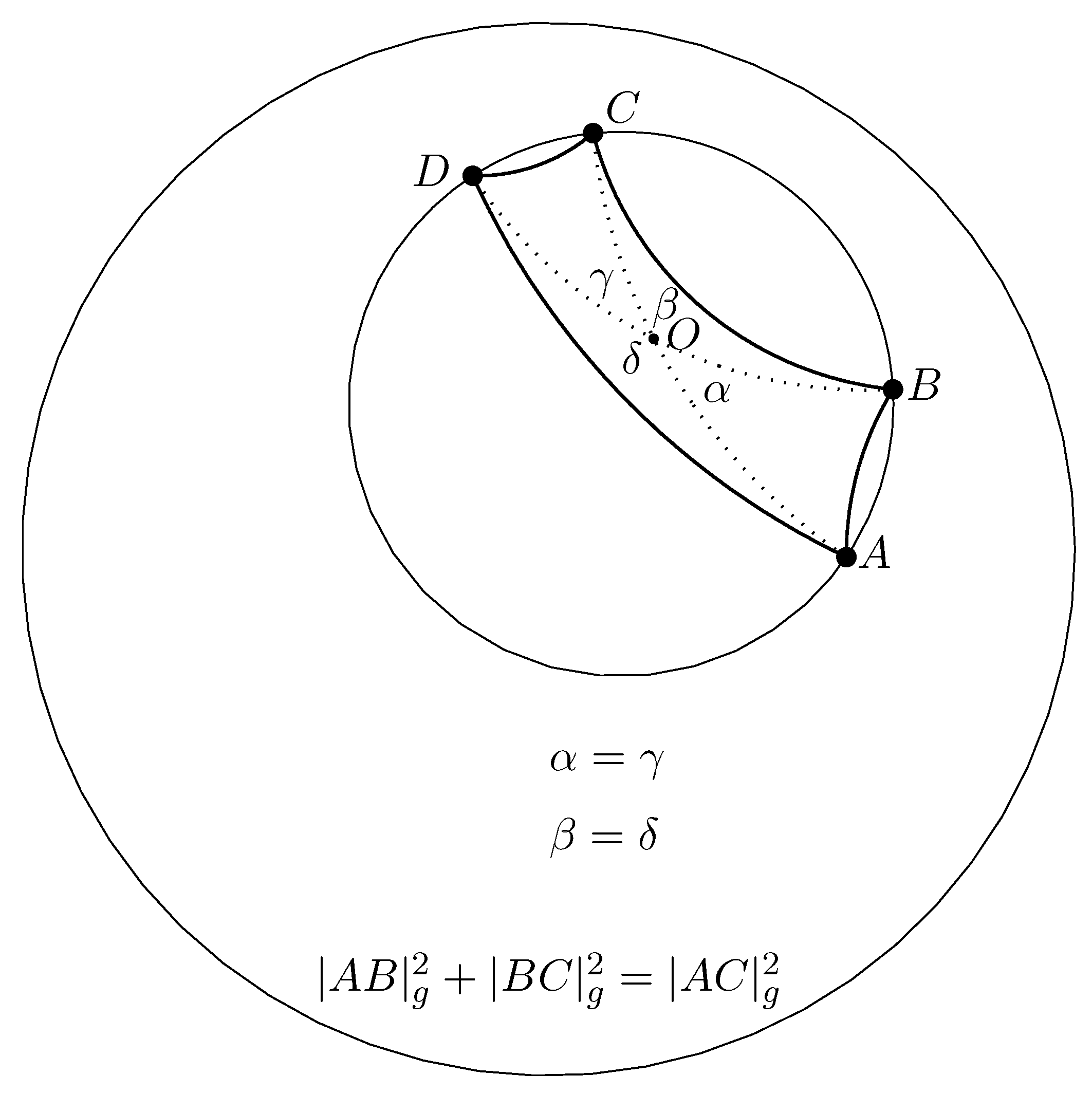

Definition 1. A gyrotriangle is gyrodiametric if one of its gyrosides coincides with a gyrodiameter of its circumgyrocircle.

In Euclidean geometry, a diametric triangle is right angled, the angle opposite to the diametric side being . In contrast, non-Euclidean gyrodiametric gyrotriangles are not right gyroangled. But, they obey a Pythagorean-like identity, as theorem 3 asserts.

Definition 2. A gyrocyclic gyroquadrilateral is gyrodiametric if its gyrodiagonals intersect at its circumgyrocenter, as shown in Figure 4.

A gyrodiametric gyroquadrilateral

, shown in

Figure 4, gives rise to the two gyrodiametric gyrotriangles

and

. In the notation shown in

Figure 4 we clearly have

Hence, by (

19), the equations in (

22) yield, respectively, the equations

Hence, it follows from (

21) that

where

,

and

are the g-modified gyrolengths of the gyrosides of the gyrodiametric gyrotriangle

, as shown in

Figure 4.

Formalizing the result in (

24), we have proved the following theorem, where we use the notation in

Figure 4.

Theorem 3.

(Gyrodiametric Gyrotriangle Pythagorean-like Equation).Let be a gyrodiametric gyrotriangle in a Möbius gyrovector space , where is the gyrodiametric gyroside. Then, the gyrotriangle gyrosides obey the Pythagorean-like equation

where

References

- Ungar, A.A. Thomas rotation and the parametrization of the Lorentz transformation group. Found. Phys. Lett. 1988, 1, 57–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, A.A. A gyrovector space approach to hyperbolic geometry; Morgan & Claypool Pub.: San Rafael, California, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, A.A. Analytic hyperbolic geometry: Mathematical foundations and applications; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.: Hackensack, NJ, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, A.A. Analytic hyperbolic geometry and Albert Einstein’s special theory of relativity; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.: Hackensack, NJ, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, A.A. Analytic hyperbolic geometry and Albert Einstein’s special theory of relativity, 2nd ed.; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.: Hackensack, NJ, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, A.A. Gyrovector spaces and their differential geometry. Nonlinear Funct. Anal. Appl. 2005, 10, 791–834. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, A.A. Hyperbolic triangle centers: The special relativistic approach; Springer-Verlag: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, A.A. Ptolemy’s theorem in the relativistic model of analytic hyperbolic geometry. Symmetry 2023, 15, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, A.A. Hyperbolic trigonometry in the Einstein relativistic velocity model of hyperbolic geometry. Comput. Math. Appl. 2000, 40, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, A.A. From Möbius to gyrogroups. Amer. Math. Monthly 2008, 115, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).