1. Introduction

Chagas disease (CD) is a medical condition first identified by the Brazilian physician Carlos Chagas in 1909, and it arises from an infection with protozoan

Trypanosoma cruzi. CD continues to be a significant public health concern, particularly in endemic regions of Latin America, where it mainly spreads through contact between humans and the feces or urine of triatomine bugs that feed on blood [

1].

Due to the migration of infected individuals and non-vector transmission pathways such as blood transfusion, organ transplantation, and congenital infection, CD has emerged as a potential menace to non-endemic countries, particularly in the United States, Europe, and the Western Pacific region [

2,

3]. In areas endemic to CD, chronic cardiomyopathy associated with the condition is the leading cause of cardiac-related morbidity [

4,

5].

Although Benznidazole (BZ) and nifurtimox have been utilized to treat CD since the 1960s [

6], there is still no satisfactory treatment available for the chronic stage of the disease. These drugs have both limited efficacy and are often associated with side effects. Additionally, require long periods of administration, making it essential to develop new and effective alternatives to treat CD. Experimental infection of various animals with

T. cruzi has facilitated the study of the natural history of CD. Research using mice, rats, dogs, rabbits, guinea pigs, hamsters, and monkeys has yielded a wealth of information about the immunopathology of CD since its discovery [

7,

8]. However, the major aspects of CD pathogenesis remain poorly understood.

Over the past three decades, experimental investigations have demonstrated that BALB/c mice, when acutely infected with

T. cruzi, produce interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). This immune response leads to the activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and an increase in the production of nitric oxide (NO), which is crucial for macrophage trypanocidal activity [

9,

10,

11]. However, cytokines and NO are also involved in host immunity suppression [

12].

Experimental findings also indicate that NO may play a role in regulating various other processes that are crucial for an effective immune response against the parasite [

13,

14]. The discovery that

T. cruzi infection induces NO production in the myocardium raises new questions, and the consequences of this discovery are far from fully understood [

15,

16,

17].

Nitroxyl (HNO) is a molecule that has been shown to act as a regulator of cardiovascular function and has been investigated as a potential treatment for heart failure, myocardial infarction, and hypertension, among other cardiovascular conditions [

18] including CD [

19] and hyperalgesia [

20]. It has both a role as endothelium relaxing factor and hyperpolarizing factor as well [

21]. However, it is a different entity than the related nitrogen oxides NO and NO

+ [

22,

23]. Our investigation focused on examining the pharmacological properties of Angeli’s salt (AS; Na

2N

2O

3), a known nitroxyl (HNO) donor [

24] in

T. cruzi infection pathogenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

The handling of animals and experimental procedures were carried out in strict adherence to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as recommended by the Brazilian National Council of Animal Experimentation (COBEA). The Internal Scientific Commission and the Ethics in Animal Experimentation Committee of Londrina State University approved the study protocol in compliance with the guidelines of the National Council for the Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA) under the Approval Number: CEUA nº 4628.2016.40/ 002.2021. All necessary measures were taken to reduce the pain and suffering of the animals involved in the experiments.

2.2. Animals and Experimental Design

We obtained male C57BL/6 mice (8-12 weeks old) from the Multidisciplinary Center for Biological Research (CEMIB), University of Campinas (UNICAMP; Campinas, Brazil). The mice were then kept under standard conditions in the animal house of the Department of Immunology, Parasitology and General Pathology, Center for Biological Sciences, State University of Londrina.

The mice were kept in an animal house with a controlled environmental temperature (21-23°C) and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. They were provided with commercial rodent diet (Nuvilab-CR1, Quimtia-Nuvital, Colombo, Paraná, Brazil) and sterilized water ad libitum. For the experiment, mice (n = 5–10 per group), were inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 5 × 10

3 T. cruzi bloodstream trypomastigotes (Y strain of

T. cruzi I lineage) [

25]. Control groups received an injection of the same amount of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2).

To quantity parasitemia, 5 µL of fresh blood were collected from the tail vein of mice. The number of parasites in 50 microscopic fields at 400× magnification was counted using an Olympus CH30LF100 - (Olympus Optical CO., LTD) light microscope. This procedure was performed on days 3, 5, 7, 9, 13, 15, 19, 21,23,25,27,29 and 31 after infection. The data obtained were expressed as number of parasites per mL [

26]. Confirmation of

T. cruzi infection was done through direct microscopic observation of circulating trypomastigotes in the peripheral blood of mice at three days post-infection (dpi). The survival rate was assessed at 31 dpi (

Figure 1). Only mice with positive parasitemia were included in the infected groups. To euthanize the animals, they were anesthetized using ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) before performing cervical dislocation.

2.3. Treatment Schemes

The synthesis and use of AS (sodium trioxodinitrate) followed previously described methods [

20,

27]. Stock solutions were prepared in 10 mM NaOH and stored at −20°C. The stability of solutions was determined from the extinction coefficients at 250 nm (ε of 8000 M

−1 cm

−1 for AS [

28] and prepared at 7 mg/mL of 10 mM NaOH. Mice were treated with PBS-diluted AS (6 µg/kg/animal, 60 µg/kg/animal, and 600 µg/kg/animal), prepared daily 15 min before the beginning of the treatment [

20]. The treatment began 15 min after

T. cruzi inoculation and continued for 12 consecutive days. Control animals, both infected and uninfected, were administered the same volume (100 µL) of PBS as per the schedule for the intraperitoneally infected mice. The experimental design is depicted in

Figure 1.

2.4. Hematological Analysis

Mice were anesthetized and whole blood was collected through intracardiac puncture using syringes and needles containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Standard methods were utilized to count the leukocytes, platelets, and reticulocytes [

29,

30,

31].The plasma was separated and stored at −20°C until use.

The microcentrifugation of capillary tubes filled with blood was performed to obtain the hematocrits, while a manual hemocytometer was used to determine the total number of nucleated cells collected. The normal values obtained from uninfected C57BL/6 mice kept under the same conditions [

32] were considered in all experiments performed to determine the hematological parameters of the animals (12 dpi).

2.5. Cardiac Parasitism

At 12 dpi, the hearts were collected, immersed in 10% buffered formalin, and the fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin, processed for microtomy, and subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The tissue sections were examined under light microscopy, and the number of parasite nests in each section was counted across 50 microscope fields at a magnification of ×400. Three sections were evaluated, and the results were expressed as the average of the three sections. Images were captured with a video camera adapted to a BX43 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The images were analyzed with the ImageJ software, a public domain Java image processing (

http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

2.6. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Capacity in Erythrocytes

Blood samples from the control and experimental groups (12 dpi) were used to determine erythrocyte oxidative stress. After removing the plasma and white blood cells from whole blood, the remaining erythrocytes were washed three times with PBS then resuspended in the same buffer (1:99, v/v). Oxygen uptake and induction time (Tind) (induced by 2 mM tert-butyl hydroperoxide, t-BHP) were measured using a Clark-type oxygen electrode at 37°C [

32,

33]. Tind value is closely associated with the intracellular capacity of protective antioxidants, while oxygen uptake serves as an indirect indicator of the vulnerability of erythrocyte membranes to lipid peroxidation triggered by t-BHT [

32,

34,

35].

2.7. Oxidative Processes Induced by Tert-butyl Hydroperoxide in Erythrocytes

Mouse erythrocytes from control and experimental groups were collected by centrifugation (800 × g, 10 min) at 25°C and then washed thrice with PBS. A 1% erythrocyte suspension in PBS was prepared when needed. To initiate the chemiluminescence (CL) reaction, 20 µL of t-BHT was added to a final concentration of 0.6 mM in 1 mL [

36,

37]. Relative light units (RLU) were used to express the results obtained from measuring CL using a TD20/20 luminometer (Turner Biosystems, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) [

35]. The relative amount of pre-existing lipid hydroperoxide in erythrocyte membranes was determined using the integrated area under the curve.

2.8. Evaluation of Nitric Oxide (NO)

Nitrite levels in the plasma (12 dpi) were determined as an indirect measure of NO. We used the cadmium-copper system followed by the Griess reaction, as described previously [

38] with some modifications proposed by Panis et al. [

17]. Briefly, 60 µL aliquots were deproteinized by adding 50 µL of 75 mM ZnSO

4 solution (Merck, Germany), vortexed, and centrifuged at 11200 × g for 2 min at 25°C. Then, 70 µL of 55 mM NaOH solution (Merck, Germany) was added to each supernatant, which was again vortexed and centrifuged at 11200 × g for 5 min at 25°C. The final supernatants were diluted in glycine buffer solution (45 g/L; pH 9.7) (Merck, Germany) at a buffer-to-supernatant ratio of 5:1.

Cadmium granules stored in a 100 mM H2SO4 solution (Merck, Germany) were rinsed three times in distilled sterile water and added to a 5 mM CuSO4 solution in glycine-NaOH buffer (15 g/L; pH 9.7) (Merck, Germany) for 5 min to obtain copper-coated cadmium granules. Cadmium treatment was used to convert all nitrates into nitrites in the biological samples, providing a more accurate estimation of total NO in the original samples. The glycine-buffered diluted supernatants were treated with activated granules (600-1000 mg, approximately 1-2 granules) and gently stirred for 10 min. Aliquots (200 µL) were transferred to microfuge tubes for nitrite determination. Griess reagent (200 µL) was added to each tube, consisting of Reagent I (50 mg of N-naphthyl ethylenediamine in 250 mL of distilled water) and Reagent II (5 g of sulfanilic acid in 500 mL of 3 M HCl) (Sigma-Aldrich). The tubes were incubated for 10 min at room temperature and centrifuged at 11200 × g for 2 min at 25°C. The resulting supernatants were used for nitrite determination, and 100 µL of each sample was added to triplicate wells of a 96-well microplate. A calibration curve was prepared by diluting NaNO2 (Merck, Germany) in distilled sterile water to obtain concentrations ranging from 125 µM to 0 µM. The absorbance was read at 550 nm using a LabSystems Multiskan EX microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the results were expressed in µM nitrite.

2.9. Cellular Metabolic Assay by Reducing Resazurin in Trypomastigotes

AS was incubated for 24 h with trypomastigotes forms of

T. cruzi (Y strain) and the cell viability was determined by the resazurin assay [

39]. Resazurin sodium salt was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA, and stored at 4°C while protected from light. A solution of resazurin was prepared in DMEM (pH 7.4) and filter-sterilized prior to use. Experiments were carried out in 96-well microplates containing 1 × 10

6 parasites per milliliter. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, testing the different concentrations of AS (3,6,60 and 600 μM). After incubation, the medium was removed. Subsequently, DMEM (200 μL) containing resazurin (20 μM) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for an additional 2 h and the fluorescence intensity was quantified in the Glomax® fluorescence reader (520 nm excitation and 580 nm emission). Viable cells with an active metabolism can reduce resazurin, a blue compound, to form resorufin, a pink molecule with emission at 580 nm. Controls included the incubation of trypomastigotes alone with culture medium (DEMEN and NaOH 10mM, vehicle for AS), and H

2O

2 1mM (positive control). The assays were performed in quadruplicate.

2.10. Inflammatory Peritoneal Macrophages Culture

Groups of C57BL/6 mice (five to ten) received intraperitoneally 2 mL of 5% thioglycollate solution. After four days, the resulting elicited cells from the peritoneal exudates were collected in cold PBS. The mouse peritoneum was washed with 5 mL of ice-cold serum-free RPMI. Peritoneal cells were pooled and left to adhere to the complete medium (RPMI, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 40 µg/mL gentamicin, and 10 mM HEPES) for 24 h in 24-well plates at 2 × 106 cells/well. Each suspension of pooled peritoneal cells was plated in triplicate. The non-adherent cells were removed by washing, and the adherent cells were cultured in a complete medium. Macrophages were seeded onto 13 mm round glass coverslips and washed with warm PBS prior to the interaction assays. Additionally, macrophages were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in 96-well plates.

2.11. Treatment of Macrophages and Invasion Assay

To examine the impact of AS on the host cell’s ability to internalize the parasite, elicited peritoneal macrophages that had been washed beforehand were incubated with AS (15 µM, 30 µM and 60 µM) in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C for 1 hour prior to the experiments. After removing the medium containing AS, macrophages were incubated with trypomastigotes at a ratio of five parasites per cell. The mixture was allowed to react for 2 hours at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cells were washed three times, fixed with Bouin’s fixative, stained with Giemsa stain (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and observed under a light microscope at 1000× magnification. To serve as a positive control for T. cruzi infection, some macrophages were incubated in medium alone.

To calculate the internalization index, we multiplied the percentage of infected cells by the mean number of parasites per infected cell [

40,

41,

42,

43]. The internalization indices of all treated macrophages were normalized to those of untreated macrophages. The experiments were repeated thrice, and six independent experiments were conducted. Infected peritoneal macrophages that were untreated were included in all experiments as controls. Light microscopy was used for quantification, and 500 cells were randomly counted.

2.12. Cytotoxicity Assay

The cells’ viability was determined by using an MTT assay, which measures mitochondrial activity in living cells. The cells were incubated with MTT for 4h at 37°C, and the formazan crystals formed were dissolved using dimethyl sulfoxide. Negative controls were also used. The plates were read using a Bio-Rad Microplate reader at a test wavelength of 570 nm and a reference wavelength of 630 nm.

2.13. Production of Nitric oxide (NO) by Macrophages Treated with AS

The level of NO produced by macrophages after treatment with AS was determined by measuring the accumulated nitrite level in the culture supernatant. After 48 hours of treatment, the culture supernatants were collected and mixed with Griess reagent, and the absorbance was measured at 550 nm. The nitrite concentrations were calculated using a standard curve generated from known concentrations of sodium nitrite.

2.14. Statistical Analysis

The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from three independent experiments, with 5-10 samples per group in each experiment. The Shapiro Wilk test was performed to evaluate normality and after checking non-normality in the data, non-parametric tests were used. The non-parametric Friedman ANOVA paired test was used to evaluate the evolution over the 3rd - 31st days after infection. Parasitemia levels were also estimated by the area under the curve (AUC) during the T. cruzi acute infection. Survival curves were compared using a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. For variables that had a normal distribution, we performed parametric testing as two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey post-test. GraphPad Prism software, version 8 (La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. All analyses were two-tailed, and p values under 5% were considered significant (p ≤ 0.05).

Author Contributions

Vera Lúcia Hideko Tatakihara: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Aparecida Donizette Malvezi: Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation. Rito Santo Pereira: Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation. Lucas Felipe Dos Santos: Methodology, Formal analysis. Bruno Fernando Cruz Lucchetti: Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation. Rubens Cecchini: Conceptualization. Formal analysis. Resources. Lucy Megumi Yamauchi: Resources. Funding acquisition. Sueli Fumie Yamada-Ogatta: Resources. Funding acquisition. Katrina M. Miranda: Conceptualization, Methodology. Resources. Waldiceu A. Verri Jr: Conceptualization, Methodology. Resources. Funding acquisition. Marli Cardoso Martins-Pinge: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Funding acquisition. Phileno Pinge-Filho P: Conceptualization. Supervision, Project administration, Formal analysis. Resources. Writing – original draft. Funding acquisition. All Authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

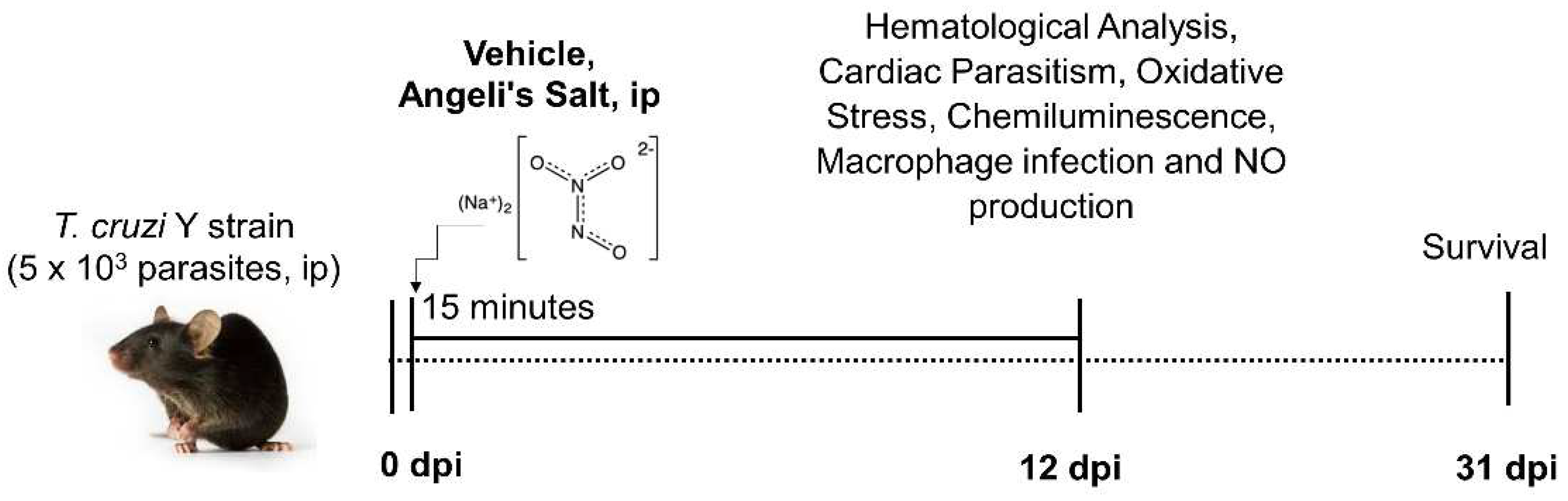

Figure 1.

Experimental design. C57BL/6 mice were treated daily with varying doses of Angeli’s salt (6, 60, and 600 µg/kg/animal) diluted in phosphate buffer (PBS) with pH 7.2 via intraperitoneal route. The treatment was administered 15 minutes post-infection for a duration of 12 days. During the acute phase, parasitemia was monitored by counting blood-borne trypomastigotes, while survival was observed daily until day 31 post-infection. At 12 days post-infection, plasma nitrite level, oxidative stress and macrophage infection were measured. All blood analyses and cell counts were conducted using standard methods.

Figure 1.

Experimental design. C57BL/6 mice were treated daily with varying doses of Angeli’s salt (6, 60, and 600 µg/kg/animal) diluted in phosphate buffer (PBS) with pH 7.2 via intraperitoneal route. The treatment was administered 15 minutes post-infection for a duration of 12 days. During the acute phase, parasitemia was monitored by counting blood-borne trypomastigotes, while survival was observed daily until day 31 post-infection. At 12 days post-infection, plasma nitrite level, oxidative stress and macrophage infection were measured. All blood analyses and cell counts were conducted using standard methods.

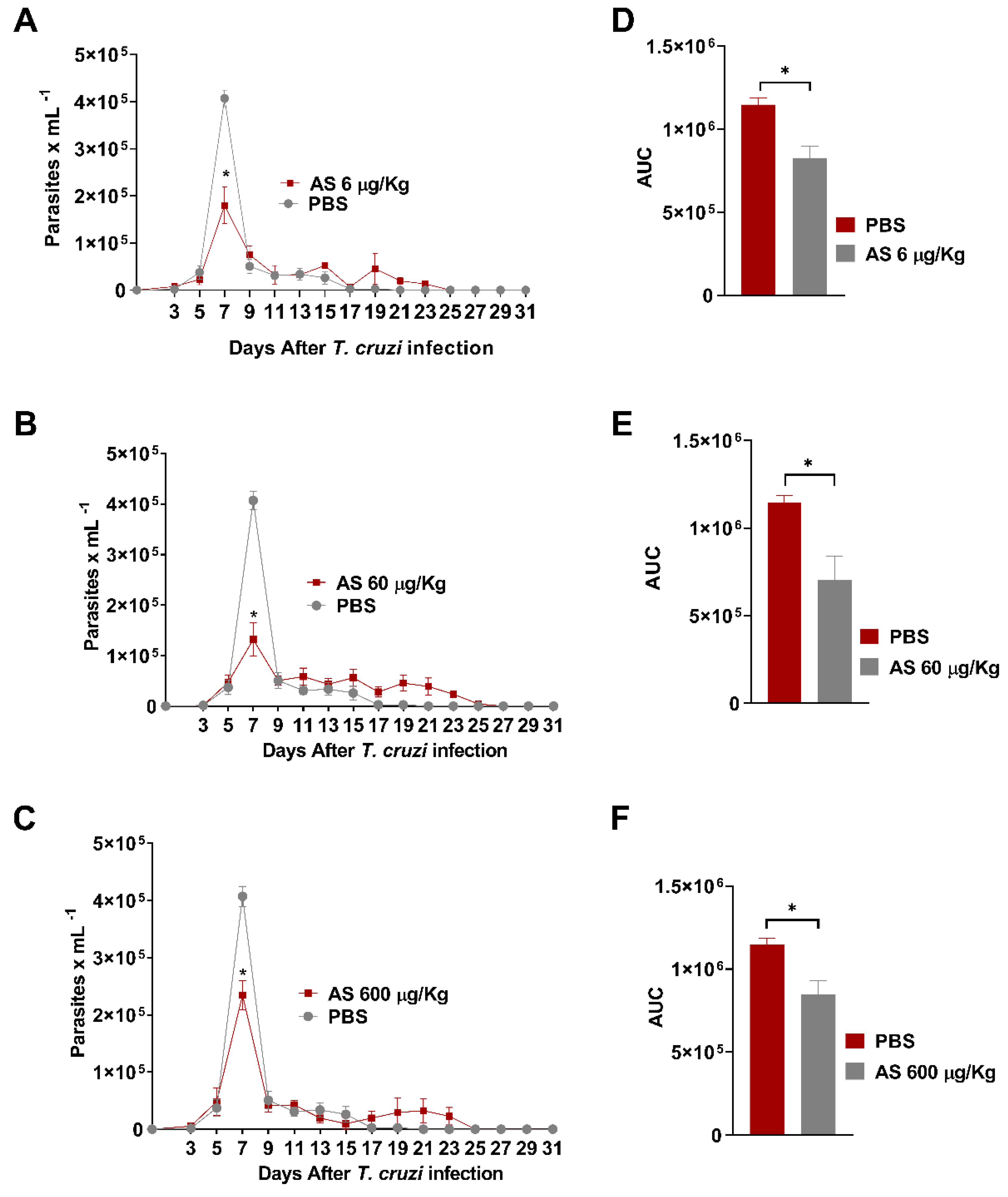

Figure 2.

T. cruzi infection course and response to AS-therapy. C57BL/6 mice were infected with 5 x 103 trypomastigotes of T. cruzi. Daily treatment with AS (6-600 µg/kg/mouse) was initiated 15 minutes after infection and continued for 12 days. Control T. cruzi-infected mice received PBS (n = 5–10). The mean ± SEM values shown are representative of three independent experiments, and significant differences in parasitemia were observed (*p = 0.0067, Friedman test). (A) treatment with AS at doses of 6ug/kg, (B) 60ug/kg, and (C) 600ug/kg. Overall parasitemia was also represented as area under the curve (AUC) analysis. Significance was determined as *p = 0.0025 (D); *p = 0.00190 (E) and *p = 0.0091 (F), applying unpaired t test.

Figure 2.

T. cruzi infection course and response to AS-therapy. C57BL/6 mice were infected with 5 x 103 trypomastigotes of T. cruzi. Daily treatment with AS (6-600 µg/kg/mouse) was initiated 15 minutes after infection and continued for 12 days. Control T. cruzi-infected mice received PBS (n = 5–10). The mean ± SEM values shown are representative of three independent experiments, and significant differences in parasitemia were observed (*p = 0.0067, Friedman test). (A) treatment with AS at doses of 6ug/kg, (B) 60ug/kg, and (C) 600ug/kg. Overall parasitemia was also represented as area under the curve (AUC) analysis. Significance was determined as *p = 0.0025 (D); *p = 0.00190 (E) and *p = 0.0091 (F), applying unpaired t test.

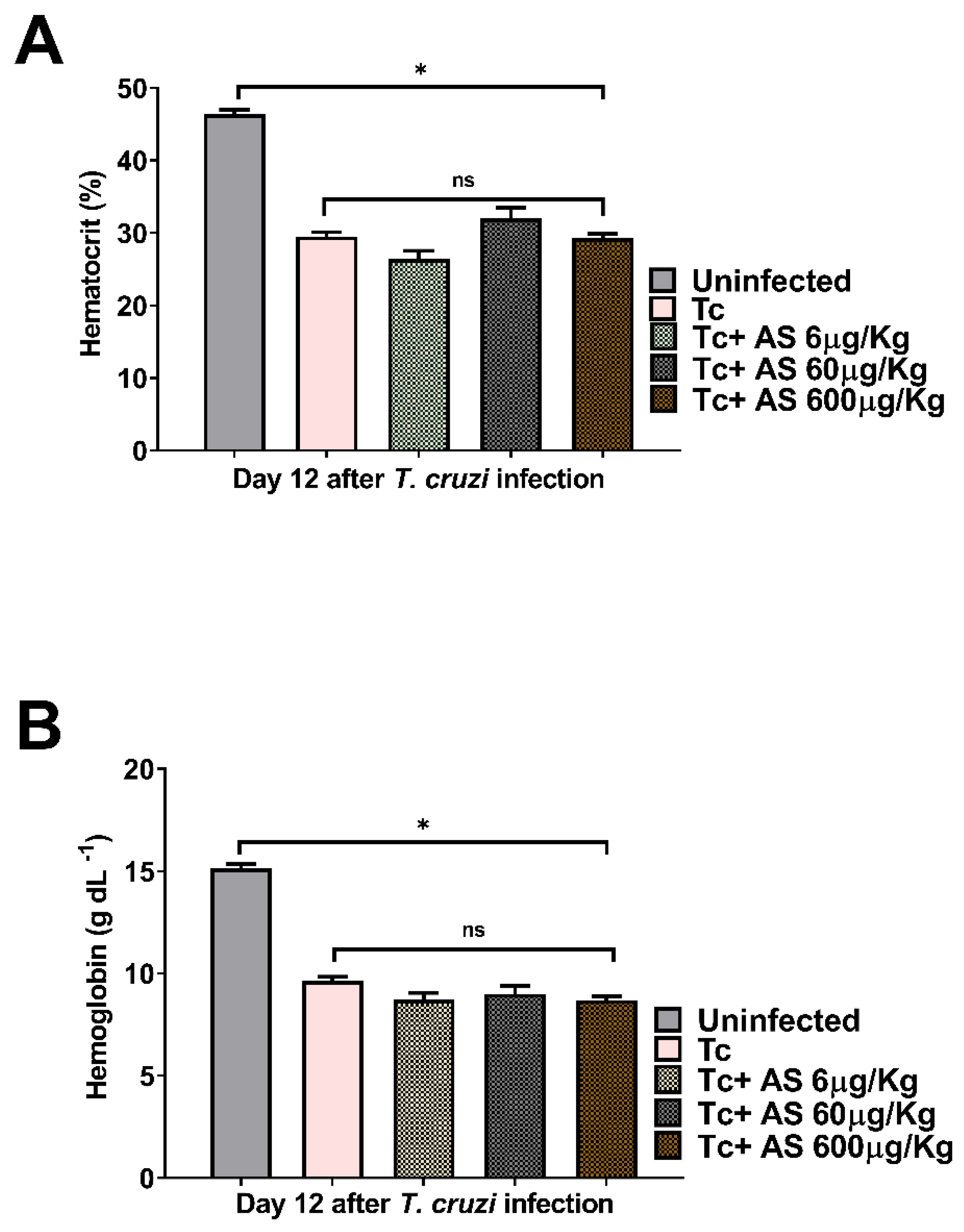

Figure 3.

The effect of AS on anemia in T. cruzi-infected mice. At day 12 post-infection, (A) hematocrit and (B) hemoglobin were evaluated. C57BL/6 mice were divided into groups of five and infected with 5 x 103 T. cruzi, treated or not with AS (6-600 µg/Kg/mouse). Control T. cruzi-infected mice (Tc group) received PBS. The mean ± SEM values shown are representative of three independent experiments, and significant differences were observed between uninfected and infected groups. *p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test, ns = non significance.

Figure 3.

The effect of AS on anemia in T. cruzi-infected mice. At day 12 post-infection, (A) hematocrit and (B) hemoglobin were evaluated. C57BL/6 mice were divided into groups of five and infected with 5 x 103 T. cruzi, treated or not with AS (6-600 µg/Kg/mouse). Control T. cruzi-infected mice (Tc group) received PBS. The mean ± SEM values shown are representative of three independent experiments, and significant differences were observed between uninfected and infected groups. *p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test, ns = non significance.

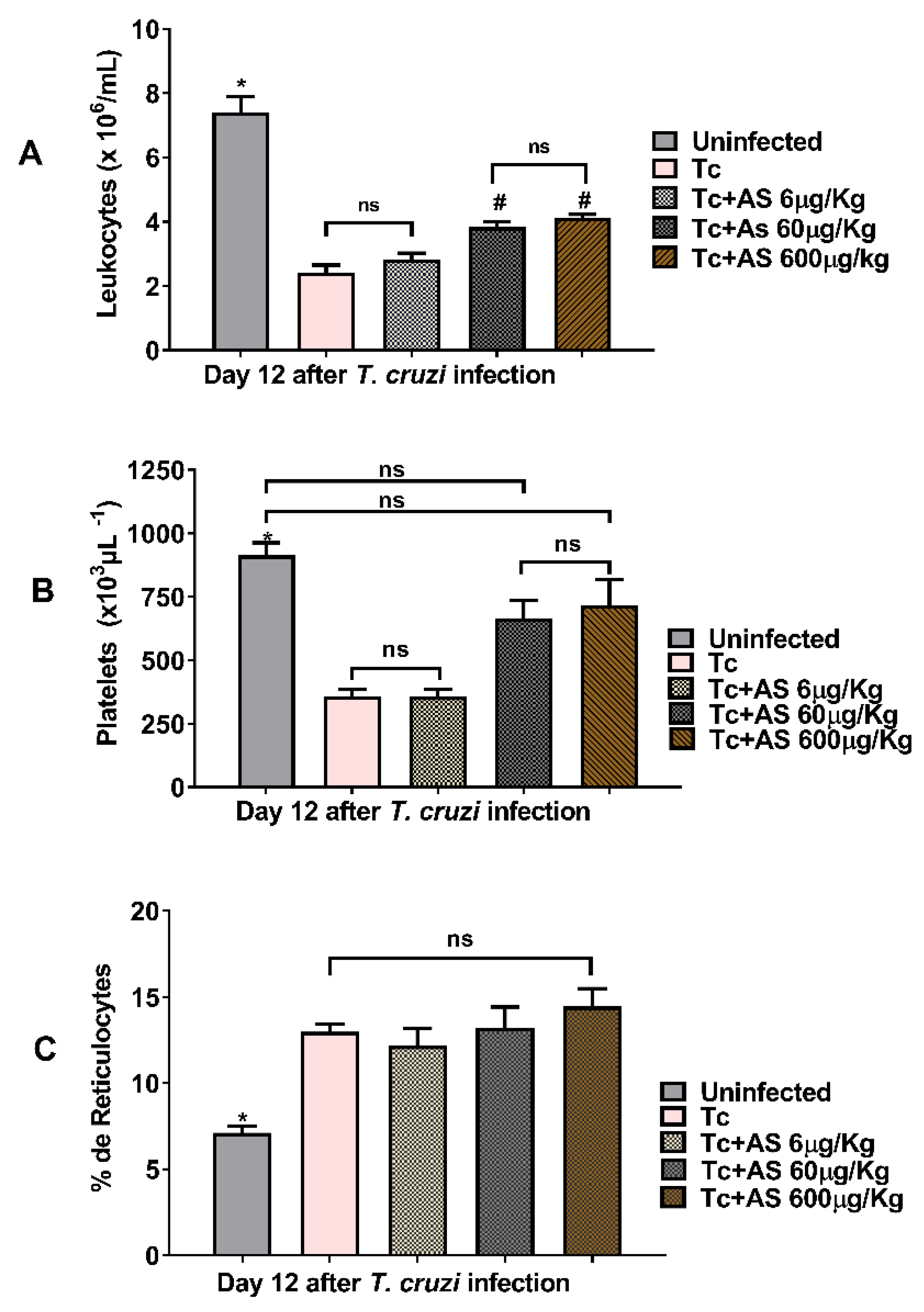

Figure 4.

AS mitigates leukopenia and thrombocytopenia observed during the acute phase of T. cruzi infection (day 12 p.i). C57BL/6 mice were divided into groups of five and infected with 5 x 103 T. cruzi, treated or not with AS (6-600 µg/Kg/mouse). Control T. cruzi-infected mice (Tc group) received PBS. The mean ± SEM values shown are representative of three independent experiments. (A) leukocytes, *p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (*Uninfected vs experimental groups), (# infected groups treated with AS 60 and 600 µg/Kg/mouse group vs uninfected group and vs infected group treated with AS 6 µg/Kg/mouse group). (B) Platelets and (C) reticulocytes, *p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (*Uninfected vs experimental groups), ns = non significance.

Figure 4.

AS mitigates leukopenia and thrombocytopenia observed during the acute phase of T. cruzi infection (day 12 p.i). C57BL/6 mice were divided into groups of five and infected with 5 x 103 T. cruzi, treated or not with AS (6-600 µg/Kg/mouse). Control T. cruzi-infected mice (Tc group) received PBS. The mean ± SEM values shown are representative of three independent experiments. (A) leukocytes, *p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (*Uninfected vs experimental groups), (# infected groups treated with AS 60 and 600 µg/Kg/mouse group vs uninfected group and vs infected group treated with AS 6 µg/Kg/mouse group). (B) Platelets and (C) reticulocytes, *p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (*Uninfected vs experimental groups), ns = non significance.

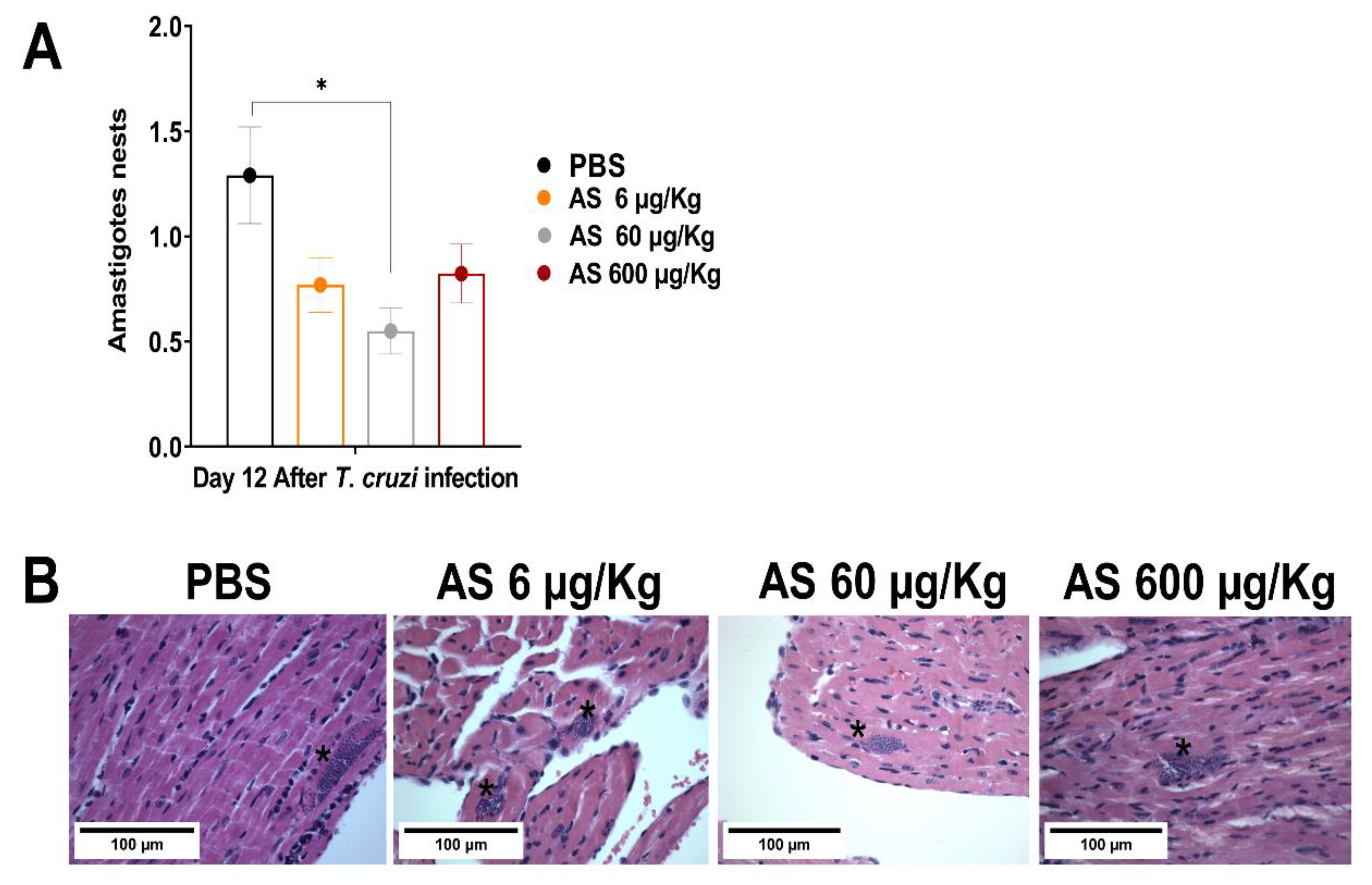

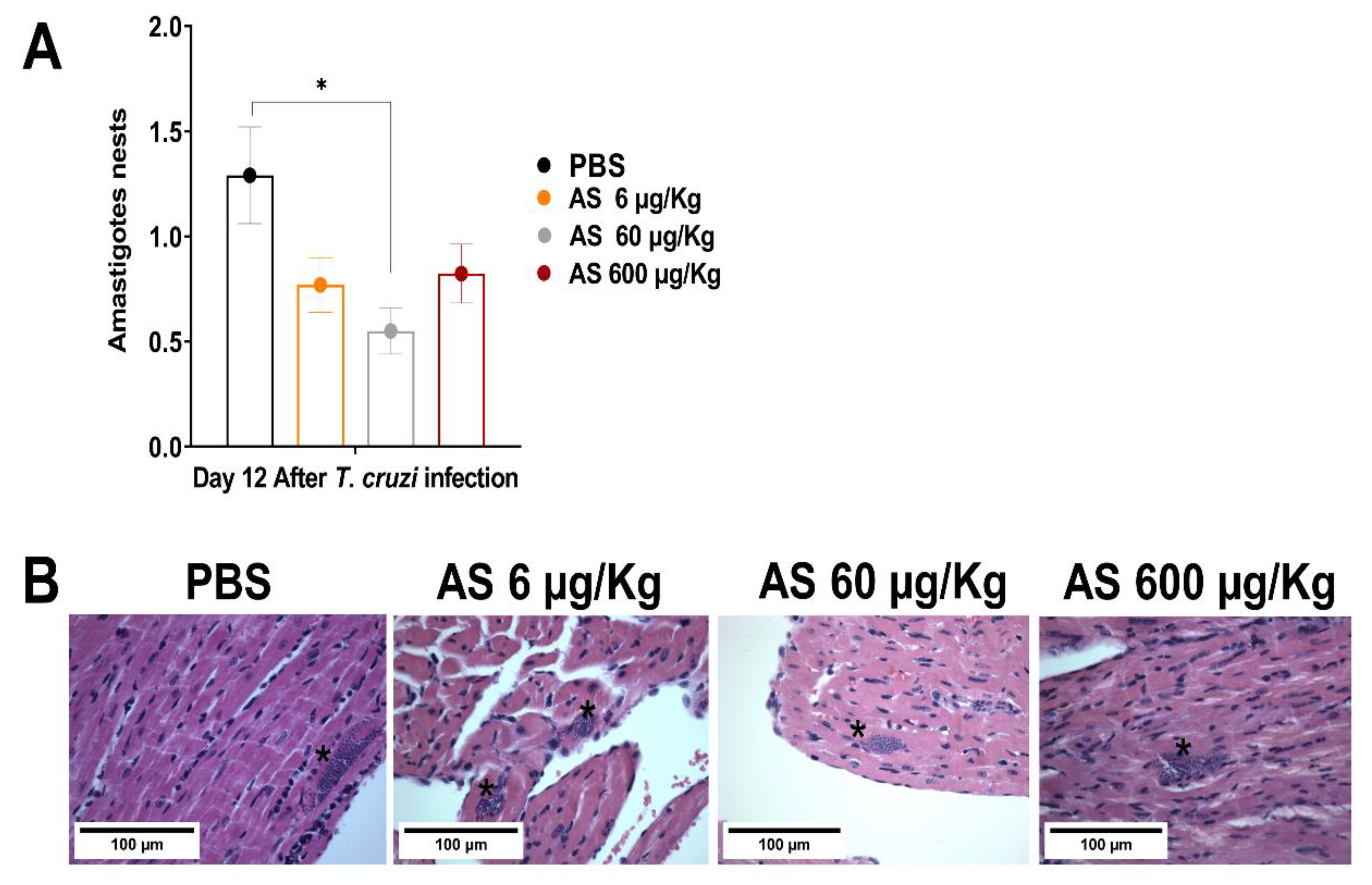

Figure 5.

Effect of AS on heart parasitism. C57BL/6 mice were divided into groups of three to five and infected with 5 x 103 T. cruzi, treated or not with AS (6-600 µg/Kg/mouse). Control T. cruzi-infected mice received PBS. Animals were euthanized 12 days after infection and sections of the heart from each mouse were collected for histopathology analysis. Tissue fragments were fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution, dehydrated, cleared and embedded in paraffin. Frozen tissue was cut into 5-mm-thick sections and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) for the assessment of amastigote nests. (A) Tissue parasitism was scored by counting the total number of amastigote nests in 25 microscope fields (1 × 400 magnification) per histopathological section. The mean ± SEM values shown are representative of two independent experiments, *p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (*Control vs experimental groups). (B) Representative photomicrograph of cardiac tissue from controls and experimental groups.

Figure 5.

Effect of AS on heart parasitism. C57BL/6 mice were divided into groups of three to five and infected with 5 x 103 T. cruzi, treated or not with AS (6-600 µg/Kg/mouse). Control T. cruzi-infected mice received PBS. Animals were euthanized 12 days after infection and sections of the heart from each mouse were collected for histopathology analysis. Tissue fragments were fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution, dehydrated, cleared and embedded in paraffin. Frozen tissue was cut into 5-mm-thick sections and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) for the assessment of amastigote nests. (A) Tissue parasitism was scored by counting the total number of amastigote nests in 25 microscope fields (1 × 400 magnification) per histopathological section. The mean ± SEM values shown are representative of two independent experiments, *p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (*Control vs experimental groups). (B) Representative photomicrograph of cardiac tissue from controls and experimental groups.

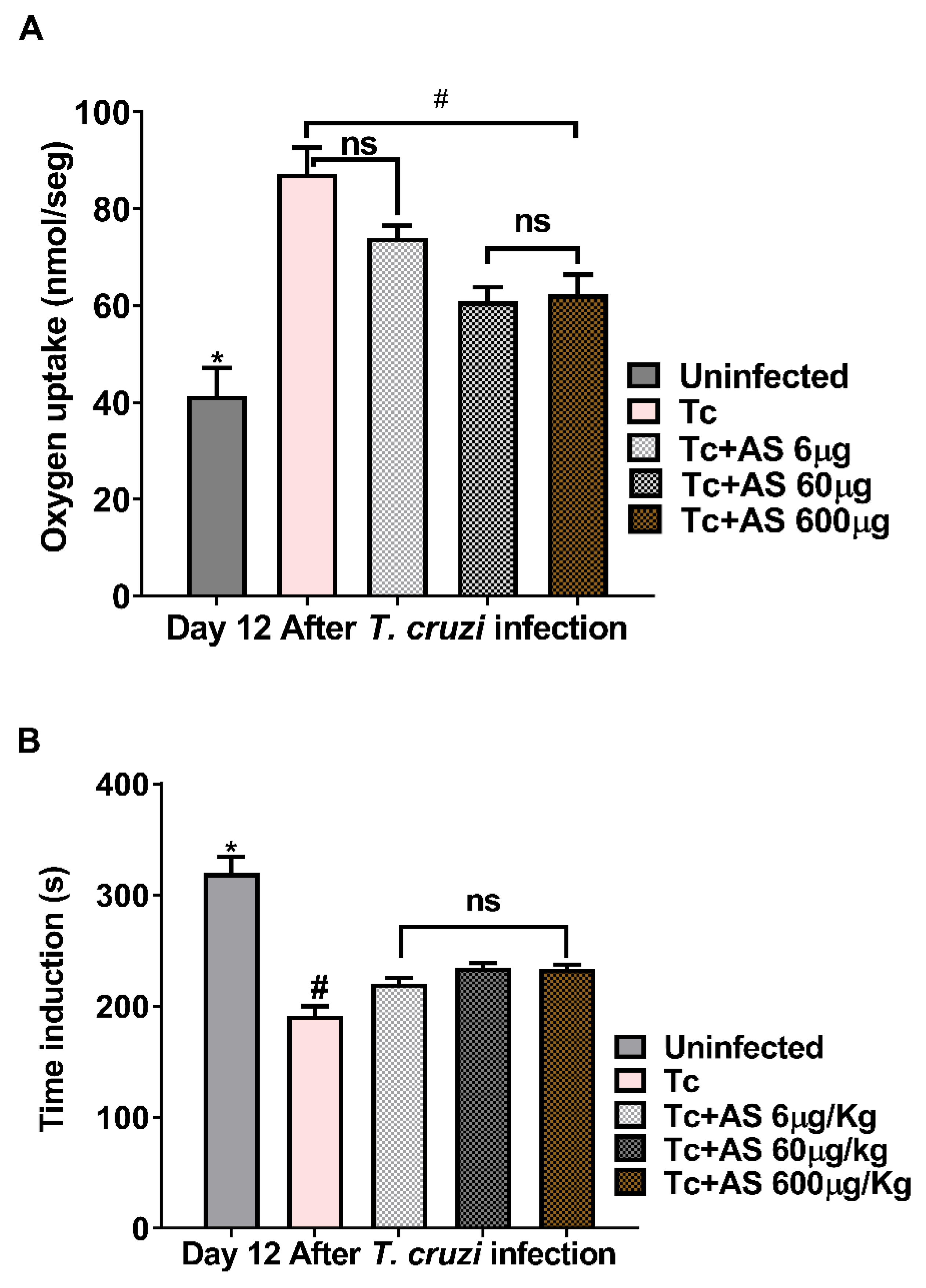

Figure 6.

AS attenuates erythrocyte oxidative stress on day 12 after T. cruzi infection. (A) Oxygen uptake and (B) induction time. Groups of C57BL/6 mice (n = 5/group) were infected with 5 x 103 T. cruzi and treated or not with AS (6-600 µg/Kg/mouse). Control T. cruzi-infected) mice (Tc group) received PBS. Values represent the mean ± SEM and are representative of three independent experiments. The mean ± SEM values shown are representative of two independent experiments, *p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (*Uninfected vs experimental groups), # p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (*Control vs experimental groups). ns = non significance.

Figure 6.

AS attenuates erythrocyte oxidative stress on day 12 after T. cruzi infection. (A) Oxygen uptake and (B) induction time. Groups of C57BL/6 mice (n = 5/group) were infected with 5 x 103 T. cruzi and treated or not with AS (6-600 µg/Kg/mouse). Control T. cruzi-infected) mice (Tc group) received PBS. Values represent the mean ± SEM and are representative of three independent experiments. The mean ± SEM values shown are representative of two independent experiments, *p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (*Uninfected vs experimental groups), # p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (*Control vs experimental groups). ns = non significance.

Figure 7.

Time course curve of t-butyl hydroperoxide-initiated chemiluminescence in erythrocytes. Groups of C57BL/6 mice (n = 5/group) were infected with 5 x 103 T. cruzi and either treated or not treated with AS (6-600 µg/Kg/mouse). Uninfected mice and untreated T. cruzi-infected mice (Tc group) were included as controls. The values presented are the mean ± SEM and are representative of two independent experiments. Significance was determined as *p ≤ 0.05, using Kruskal-Wallis’s test, indicating a significant difference from the values observed in the controls (uninfected/infected-non-treated group or infected/non-treated group/infected treated group).

Figure 7.

Time course curve of t-butyl hydroperoxide-initiated chemiluminescence in erythrocytes. Groups of C57BL/6 mice (n = 5/group) were infected with 5 x 103 T. cruzi and either treated or not treated with AS (6-600 µg/Kg/mouse). Uninfected mice and untreated T. cruzi-infected mice (Tc group) were included as controls. The values presented are the mean ± SEM and are representative of two independent experiments. Significance was determined as *p ≤ 0.05, using Kruskal-Wallis’s test, indicating a significant difference from the values observed in the controls (uninfected/infected-non-treated group or infected/non-treated group/infected treated group).

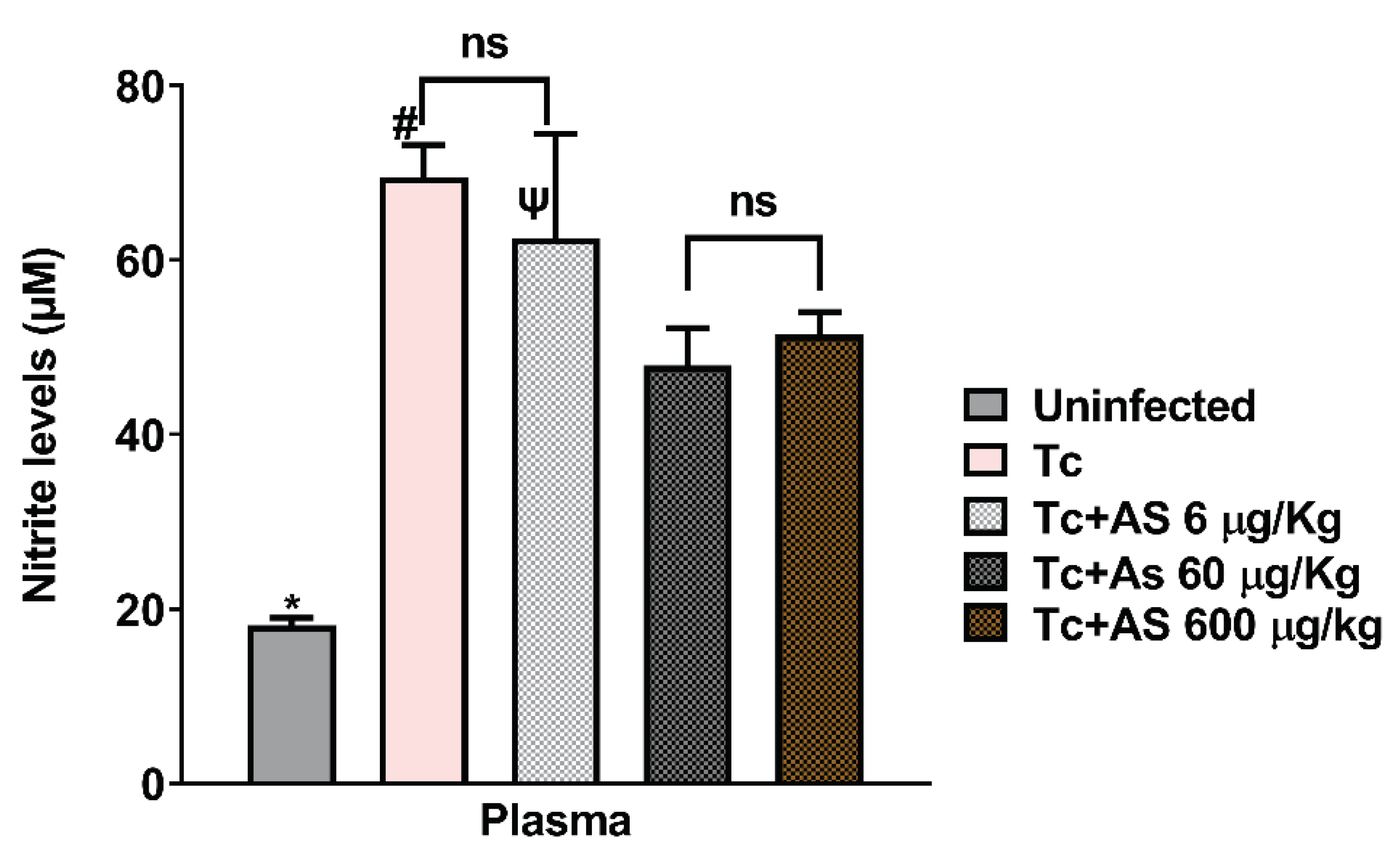

Figure 8.

Effect of AS therapy on nitrite levels in the plasma (day 12 p.i). C57BL/6 mice were divided into groups of five and infected with 5 x 103 T. cruzi, treated or not with AS (6-600 µg/Kg/mouse). T. cruzi-infected mice (Tc group) and uninfected mice received PBS and were used as controls. The mean ± SEM values shown are representative of two independent experiments, *p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (*Uninfected vs experimental groups), # p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (Control vs experimental groups), Ψ p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (Tc + 6 µg/Kg vs Tc 60 µg/Kg and Tc + 6 µg/Kg vs Tc 600 µg/Kg). ns = non significance.

Figure 8.

Effect of AS therapy on nitrite levels in the plasma (day 12 p.i). C57BL/6 mice were divided into groups of five and infected with 5 x 103 T. cruzi, treated or not with AS (6-600 µg/Kg/mouse). T. cruzi-infected mice (Tc group) and uninfected mice received PBS and were used as controls. The mean ± SEM values shown are representative of two independent experiments, *p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (*Uninfected vs experimental groups), # p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (Control vs experimental groups), Ψ p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (Tc + 6 µg/Kg vs Tc 60 µg/Kg and Tc + 6 µg/Kg vs Tc 600 µg/Kg). ns = non significance.

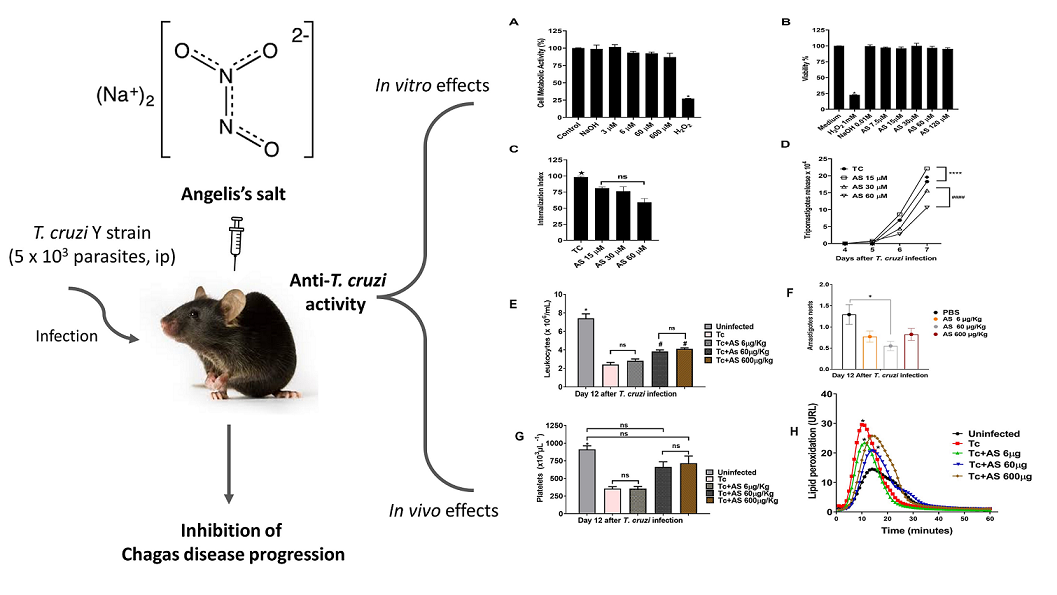

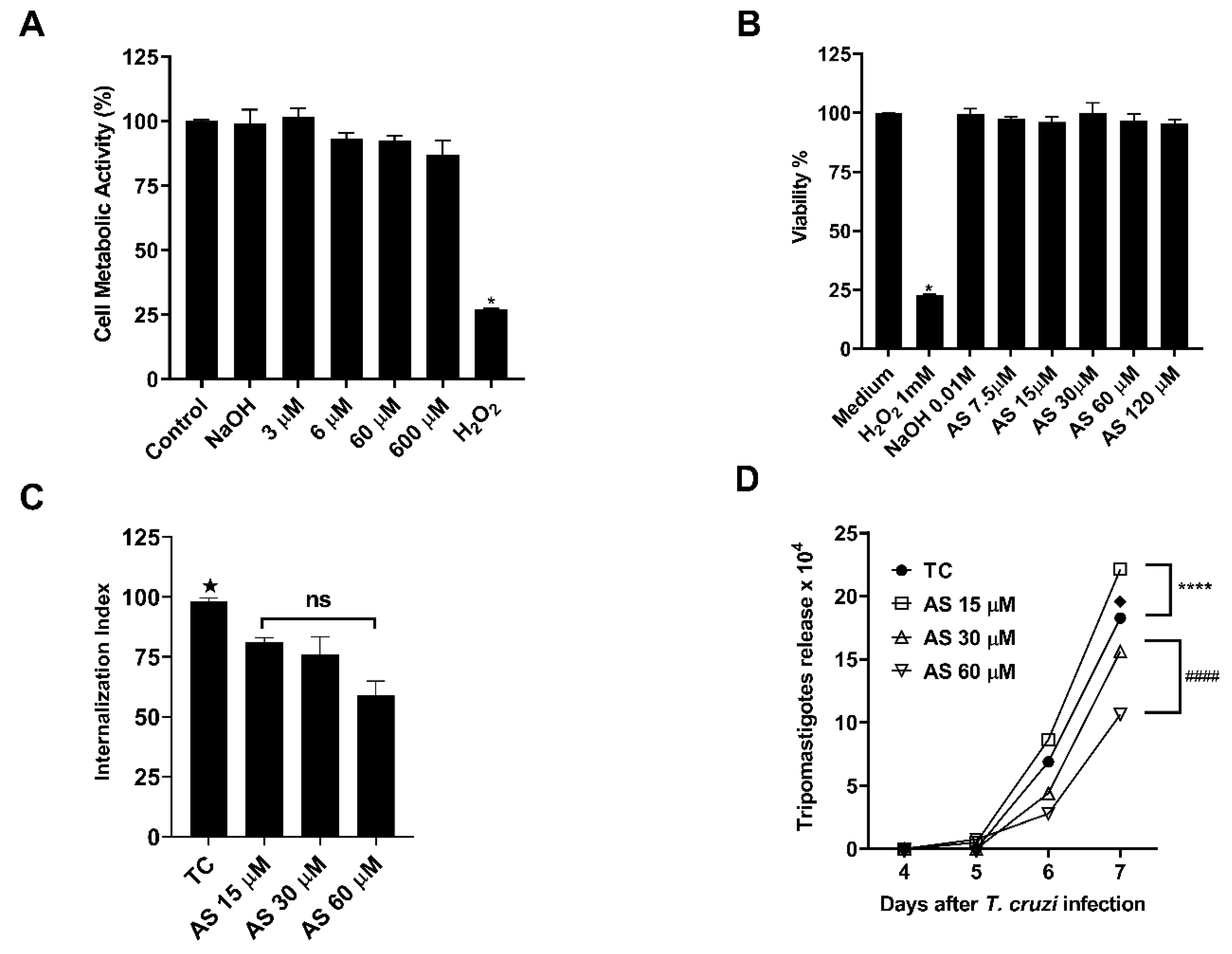

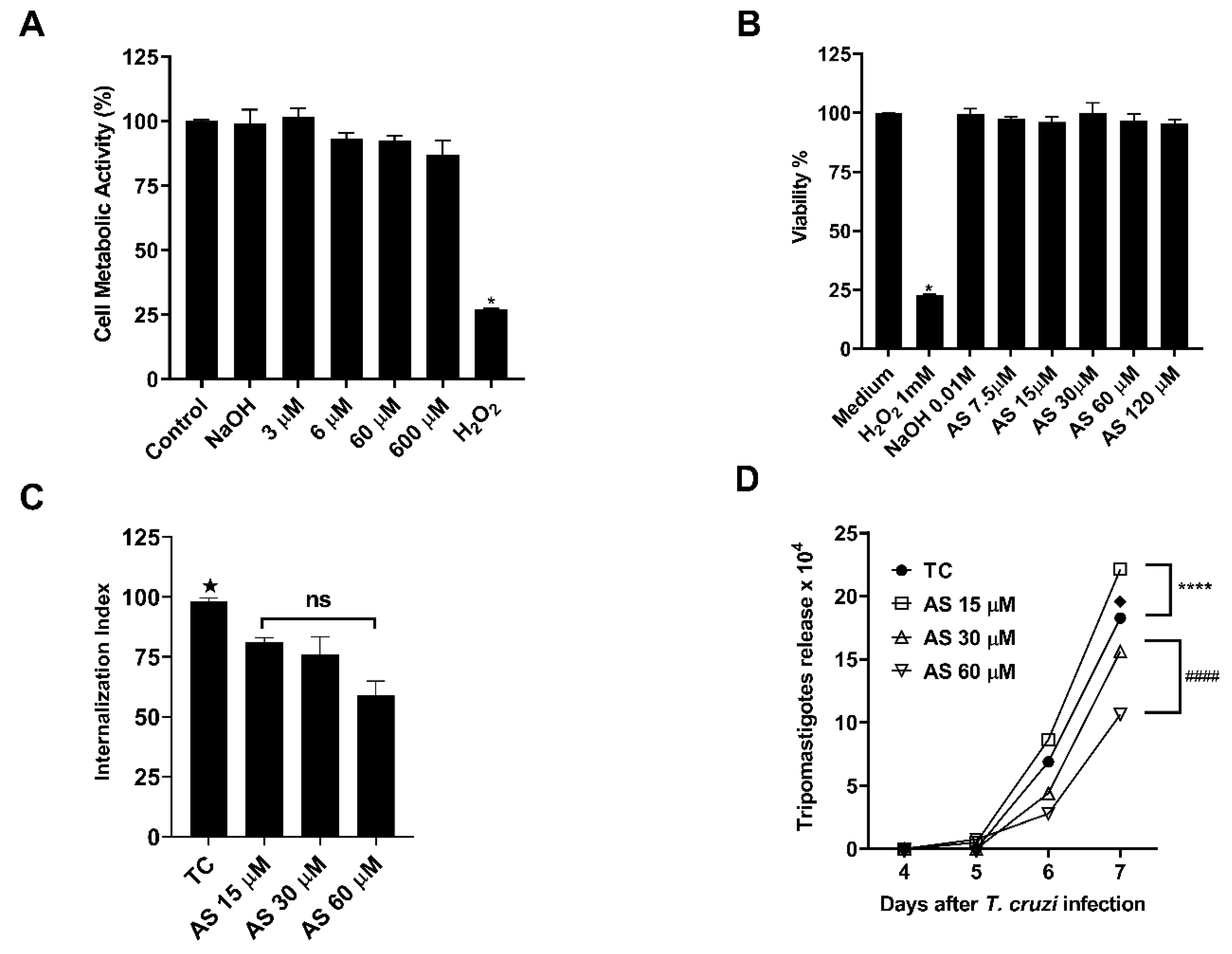

Figure 9.

AS mediates T. cruzi infection in macrophages. (A) Cellular metabolic activity by reducing resazurin in T. cruzi trypomastigotes. (B) Cell viability in macrophages treated with AS (7.5-120 µM) by MTT assay. Controls consisting of H2O2 (1 mM) and NaOH (0.01 mM). (C) Internalization index of the interaction process between macrophages, treated with AS (15-60 µM) for 1 hour and exposed to T. cruzi (5:1). (D) The effect of AS on trypomastigote release in T. cruzi-infected macrophages. Cells were infected with T. cruzi trypomastigotes and treated daily or not with AS. The release of trypomastigotes into the supernatant was detected and measured from day 4 to day 7 after infection. Values represent the mean ± SEM for triplicate determination and are representative of two independent experiments. * p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (H2O2 vs experimental groups), ★ p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (Tc vs experimental groups), ♦ p ≤ 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (Tc vs experimental groups), **** p ≤ 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (Tc vs AS 15µM), #### p ≤ 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (AS 30µM vs AS 60 µM). ns = non significance.

Figure 9.

AS mediates T. cruzi infection in macrophages. (A) Cellular metabolic activity by reducing resazurin in T. cruzi trypomastigotes. (B) Cell viability in macrophages treated with AS (7.5-120 µM) by MTT assay. Controls consisting of H2O2 (1 mM) and NaOH (0.01 mM). (C) Internalization index of the interaction process between macrophages, treated with AS (15-60 µM) for 1 hour and exposed to T. cruzi (5:1). (D) The effect of AS on trypomastigote release in T. cruzi-infected macrophages. Cells were infected with T. cruzi trypomastigotes and treated daily or not with AS. The release of trypomastigotes into the supernatant was detected and measured from day 4 to day 7 after infection. Values represent the mean ± SEM for triplicate determination and are representative of two independent experiments. * p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (H2O2 vs experimental groups), ★ p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (Tc vs experimental groups), ♦ p ≤ 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (Tc vs experimental groups), **** p ≤ 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (Tc vs AS 15µM), #### p ≤ 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (AS 30µM vs AS 60 µM). ns = non significance.

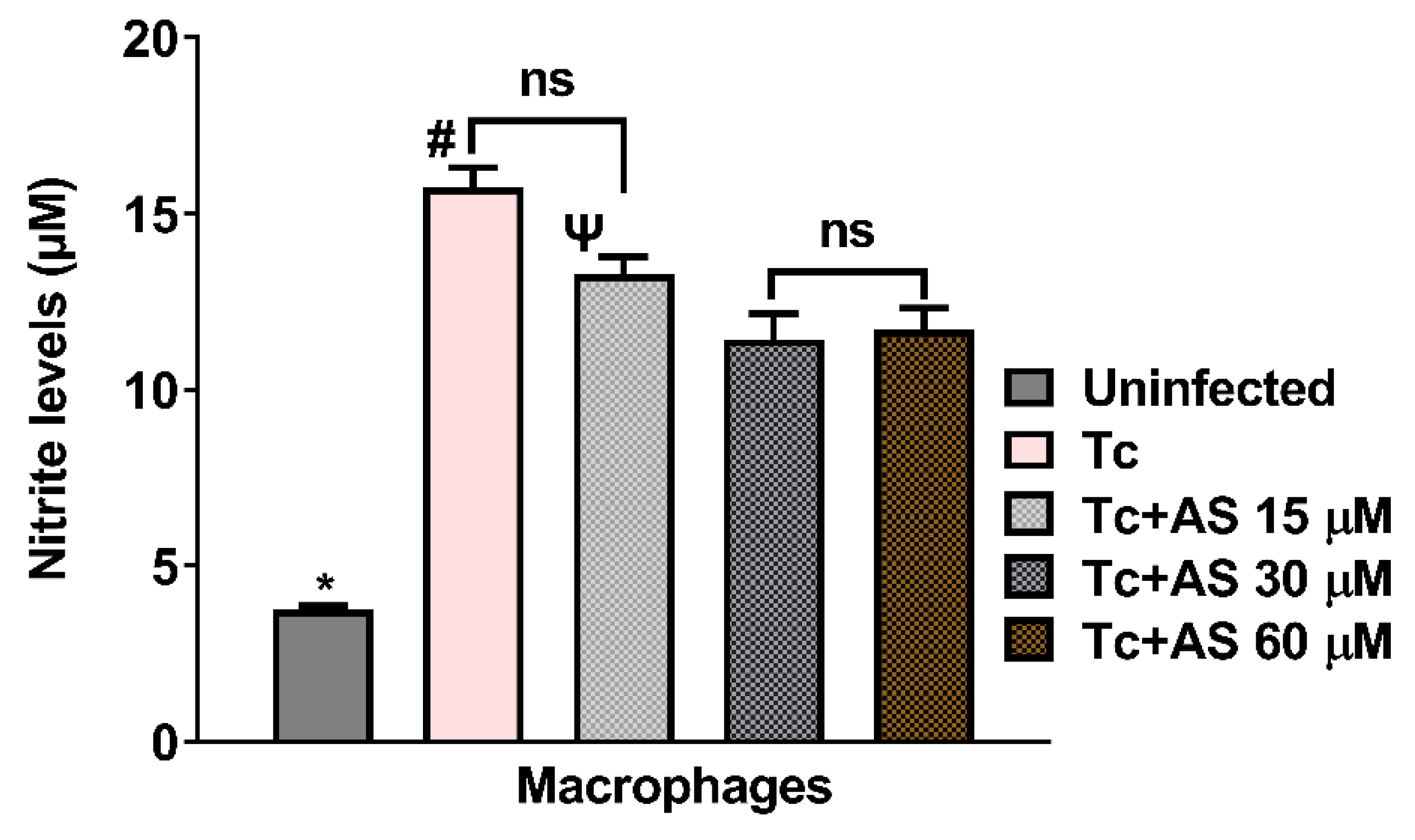

Figure 10.

Effect of AS on nitric oxide (NO) production. Production of NO by macrophages was determined by measuring the level of accumulated nitrite, a metabolite of NO in the culture supernatant using Griess reagent. Values are the mean ± SEM and is representative of two independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (*Uninfected vs experimental groups), # p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (Control vs experimental groups), Ψ p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (Tc + 15µM vs Tc 30 µM and Tc + 15 µM vs Tc 60 µM).

Figure 10.

Effect of AS on nitric oxide (NO) production. Production of NO by macrophages was determined by measuring the level of accumulated nitrite, a metabolite of NO in the culture supernatant using Griess reagent. Values are the mean ± SEM and is representative of two independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (*Uninfected vs experimental groups), # p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (Control vs experimental groups), Ψ p ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (Tc + 15µM vs Tc 30 µM and Tc + 15 µM vs Tc 60 µM).