Submitted:

20 June 2023

Posted:

21 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Aims

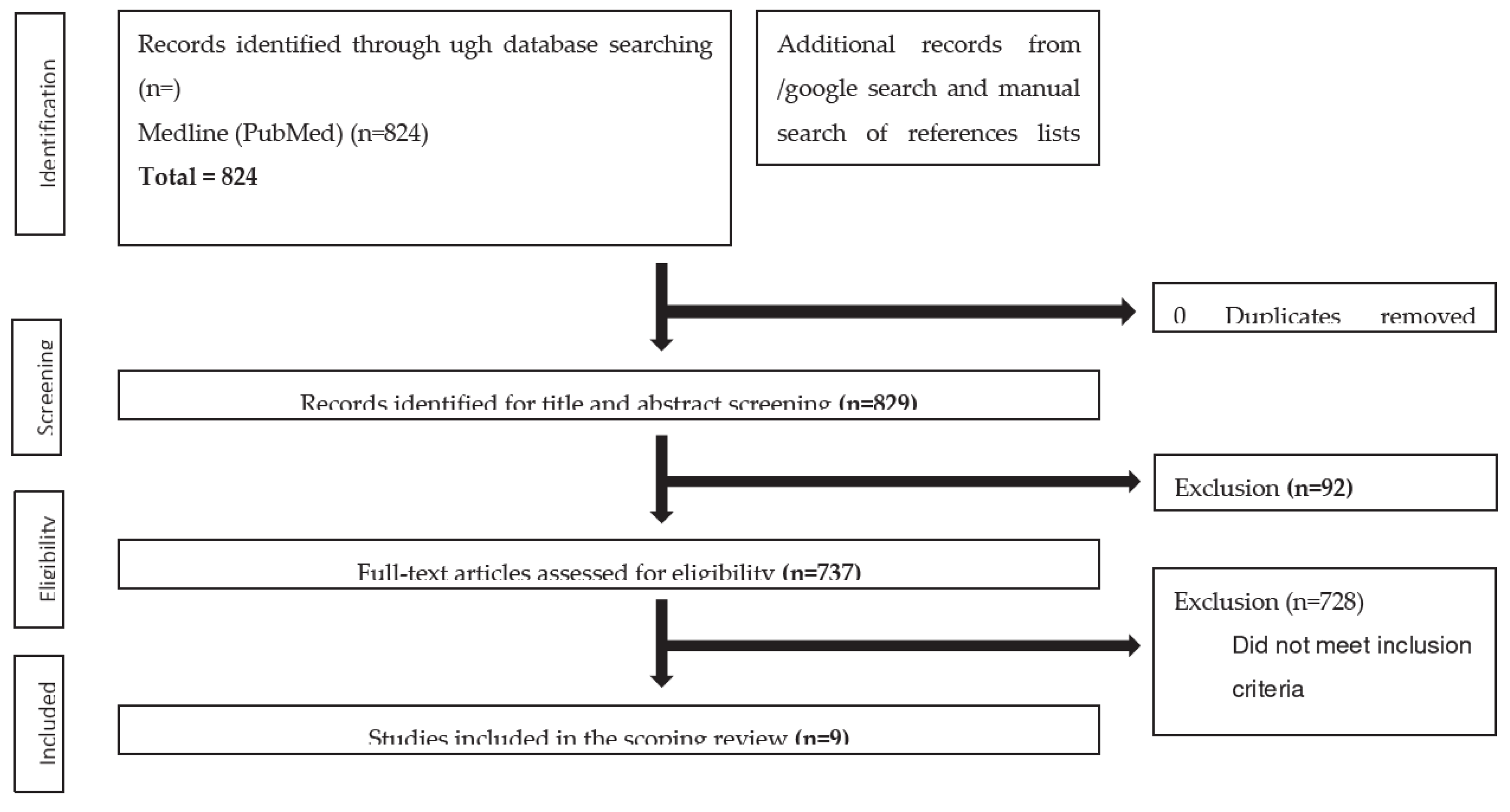

2. Methods

| Reason for exclusion | Number (From 737) |

| Review articles | 130 |

| Case reports | 24 |

| Not related to AAFD | 124 |

| Biomechanical studies | 60 |

| Other studies related to AAFD | 92 |

| All articles relating to surgical outcomes/techniques | 198 |

| Cadaver studies | 17 |

| Imaging/Radiology studies | 83 |

| New Classification Articles | 9 |

- Classifications Systems of AAFD/PCFD

| Classification and Year | Article | Categories | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Johnson and Strom | 1989 | Original stage 1-3 classification |

| 2 | Myerson et al. | 1997 | Myerson modification of stages 1-4 |

| 3 | Weinraub and Heilala | 2002 | Stage 1-3 and grades (A, B, C) |

| 4 | Bluman et al. | 2007 | Stage 1-4 (A, B, C subtypes) |

| 5 | Deland | 2008 | Stages 1-4 (7 subtypes) |

| 6 | Parsons et al. | 2010 | Stage 1-4Stage 2 subtypes (A, B, C) |

| 7 | Raiken et al. | 2012 | RAM classificationThree categories and six subtypes |

| 8 | Pasapula et al. | 2017 | Stage 0-4 |

| 9 | Myerson et al. | 2020 | Stages 1-2 (242 subtypes) |

3. Results

3.1. A critical review of classifications

3.2. Understanding the origin and identifying problems of AAFD classifications

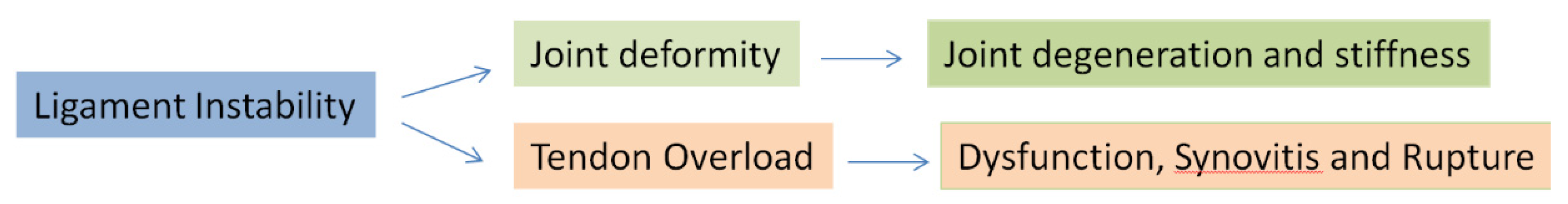

- Deformity in AAFD is a variable expression of pre-existing foot posture and progressive instability arising from progressive ligament incompetence.

- Anteromedial deltoid instability, lateral column instability and significant subtalar instability/subluxation from interosseous ligament failure need representation.

- Overload reactivity of the plantar fascia [11] and the musculotendinous units [14,16] arise as a result of instability and changes to the subtalar axis (see below). Tendon overload and reactivity vary as the deformity progresses (PL and Tendoachilles), as they become offloaded and may not manifest in all AAFD stages.

- Cavus foot types with SL laxity and FRI may have no visible deformity yet have significant instability and tendon [TP and PL] overload pain [16].

- WB [axial gravitational force] stress joints in the axial plane. Many joints act perpendicular to the axial plane and, therefore, may not be expressive of the respective joint instability on weight-bearing radiographs. Joints whose motion acts perpendicular to the axial weight-bearing axis accentuate instability when forces are applied in the direction of their action. (TN joint: lateral plane/ ankle: anteroposterior motion instability and rotational ankle instability at the deltoid).

- Foot abduction stress radiographs exacerbate TN uncoverage, and ankle valgus stress views may accentuate deltoid instability. Both may be significantly underrepresented on weight-bearing radiographs.

| Name of classification | Year | Positive aspects of classification | Negative aspects of classification |

| Johnson and Strom | 1989 | 1. Original classification that classification systems are based upon 2. Linearity of progression demonstrated a basic understanding that more severe deformity with greater stage 3. Strong representation of early stages of AAFD where deformity can present with reactive TP |

1. No proven linearity of progression between stages 2. Fails to consider foot may not start in neutral 3. Focuses on the tibialis posterior as the prime driving force 4. Stage 2 is very under simplified 5. Very little on the validation of the classification system |

| Myerson | 1997 | 1. Modified Johnson and Strom classification to show deltoid instability occurs in stage 4 | 1. Still focussed on tibialis posterior as the prime cause 2. Failure to acknowledge that anteromedial ankle instability occurs prior to deltoid ligament failure 3. Assumed linearity of progression |

| Weinraub and Heilala | 2002 | 1. Understood that multiple factors determined the failure of the flatfoot 2. Recognised that the midtarsal joint played an important role in the stabilisation of flatfoot 3. Delinked deformity and tendon pathology |

1. Still primarily focussed upon the tibialis posterior tendon as the cause. 2. Based classification upon progressive inflammation/degenerative changes of the tendon |

| Bluman | 2007 | 1. Began to subclassify stage 2 and expand the different types 2. Graded level of deformity 3. Bluman classified a myriad of treatment options for all the subtypes |

1. Classification based upon the tibialis posterior in early stages 2. Implies progression of deformity through set stages 3. No discussion of the spring ligament and other ligaments that fail |

| Deland | 2008 | 1. Recognition of the Sl as a cause of potential instability | 2. Still focuses on the TP |

| Parsons | 2010 | 1. Began to subtype stage 2 into subtypes of A, B, C | 1. Still focuses on stage tibialis posterior as the cause of the flatfoot 2. Broadly based upon Johnson and Strom classification |

| Raiken | 2012 | 1. Previous classifications did not take into consideration the involvement of the mid-foot. 2. Classification was based on anatomic location, including the ankle, hindfoot, and mid-foot 3. Subgroups based on characteristic clinical and radiographic findings 4. Treatment algorithms then suggested based on these findings |

1. Several categories make communication more difficult 2. Still focused on tibialis posterior in early stages of the hindfoot |

| Pasapula | 2017 | 1. Introduced the concept of stage 0 2. Recognised that the tibialis posterior may or may not react despite the foot SL weakening and failing. |

Still used the Johnson and Strom classification Focuses on the tibialis posterior in stage 1 Continued to therefore simplify stage 2 |

| Myerson | 2020 | 1. Readdresses the pathology away from the tibialis posterior tendon 2. Several categories allow a more accurate representation of any one foot |

1. Static weight-bearing imaging may miss or underestimate the associated dynamic instabilities. 2. Multiple tendon reactivity may be a significant presentation [14] and can present without deformity, which needs representation. 3. Focussing on deformity detracts from representing feet with ligament instability. 4. 242 subtypes identified makes comparative analysis and communication of different grades and stages difficult. |

3.3. Key aspects to take into consideration in any new classification

3.3.1. The importance of the plantar fascia (PF) in protecting the SL and the effects of tight TA

3.3.2. The role of Musculotendinous units and their overload

3.3.3. Instability

3.3.3.1. What's new about instability?

- Progressive instability is key to symptoms.

- Progressively collapse manifests as soft tissue reactivity and deformity, varying between individuals.

- Feet may not progress through all instability stages, and progression rates vary

- Some feet start with pre-existing laxity that has been physiologically normal for that foot. Increased instability progresses the foot to become symptomatic. Normal laxity for any foot may be gauged by contralateral foot comparison if unaffected, from serial foot assessment, or may never be ascertained if no pre-existing reference point exists.

- Lateral column instability, subtalar instability, and deltoid instability reflect a greater extent of foot ligament failure than the isolated failure of the medial column. Addressing the medial column alone (superficial deltoid/spring and first ray) may not restore all the foot instabilities that have developed completely.

3.3.3.2. Evidence for sequential/progressive instabilities in AAFD

3.3.3.3. First Ray Instability and its classification

3.3.3.4. Lateral Column Instability

3.3.3.5. Deltoid Instability

3.3.3.6. Subtalar Instability

4. Discussion

4.1. Foot Type and potential differential behaviour of cavus feet

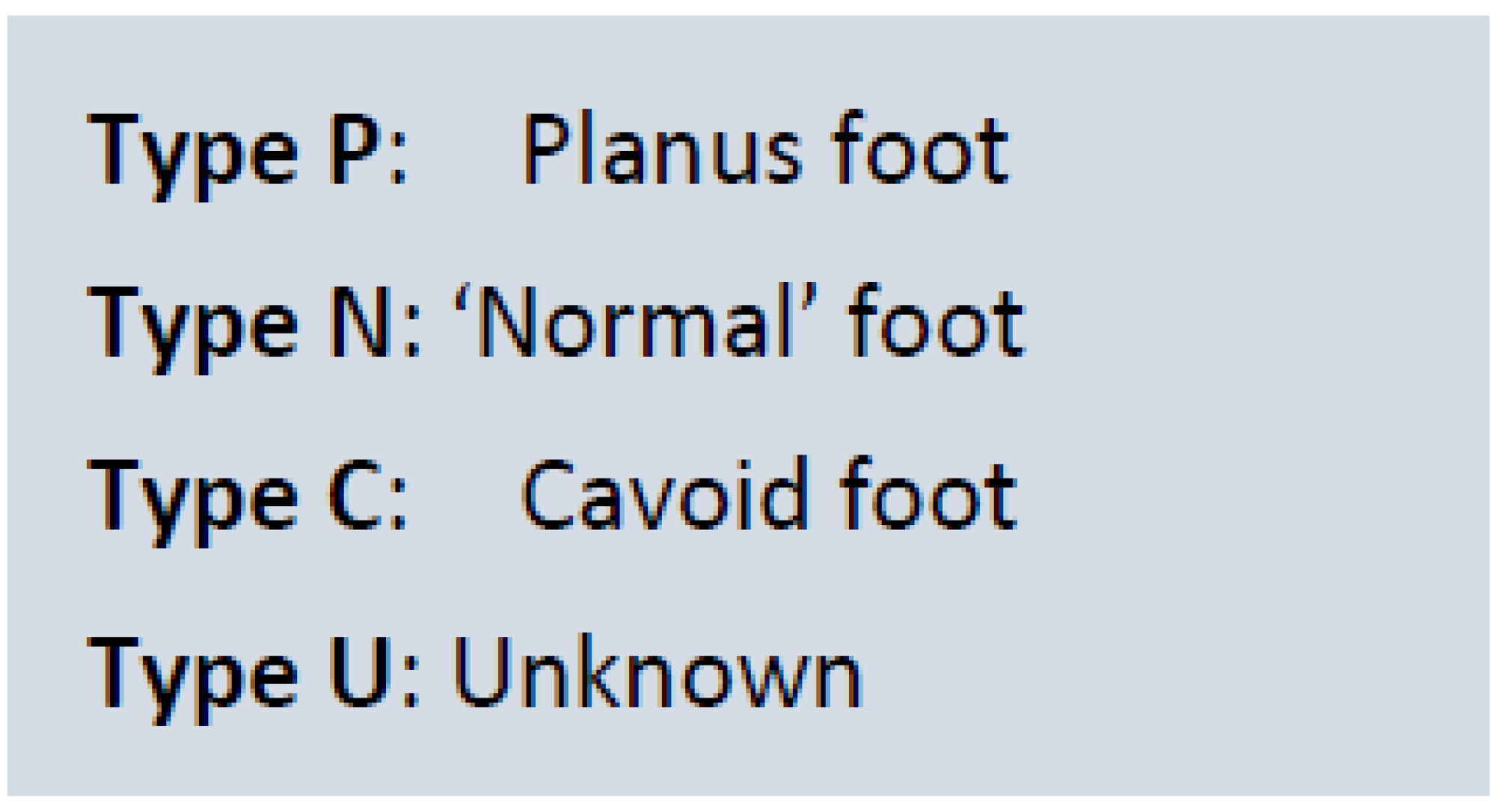

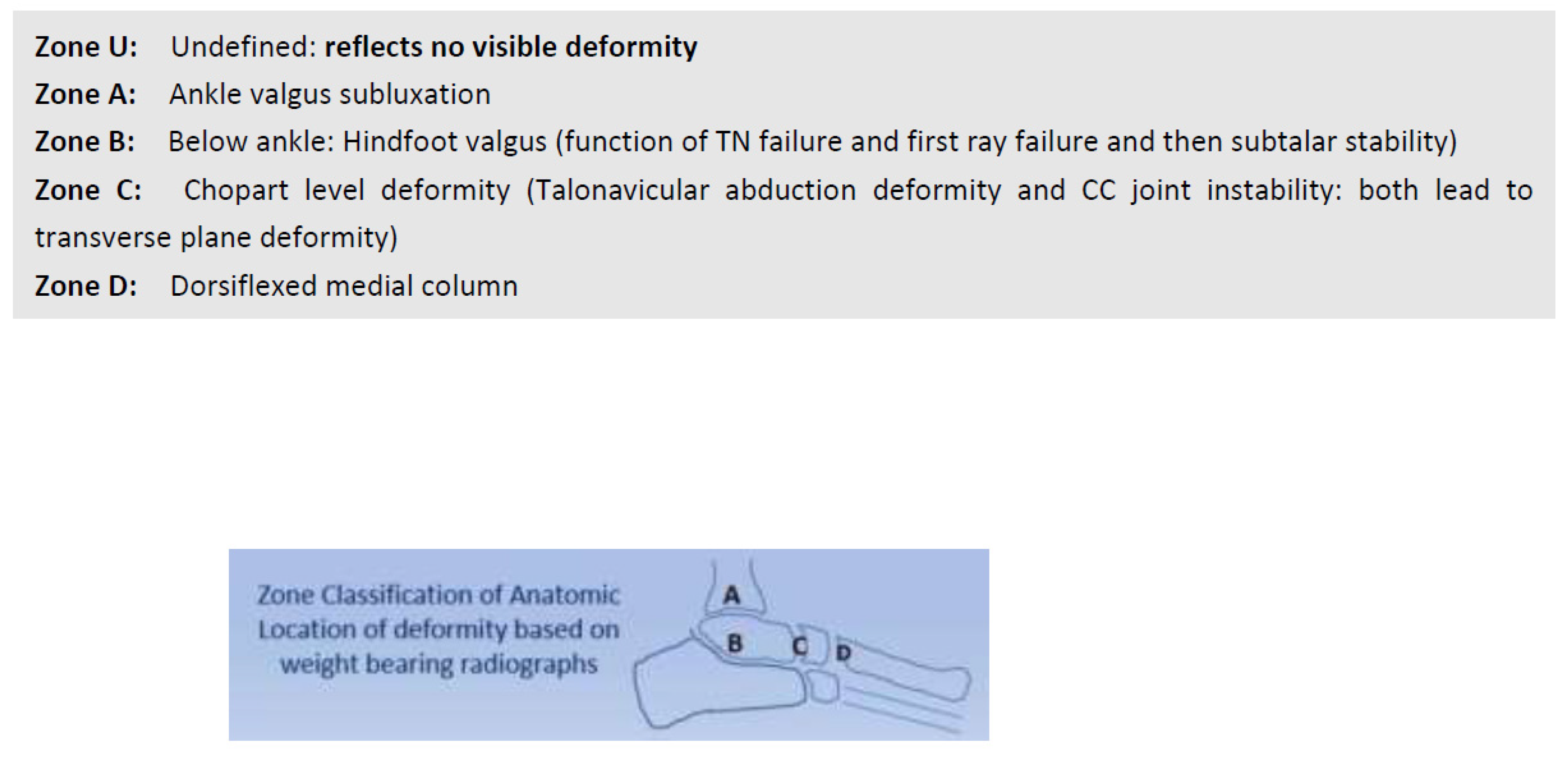

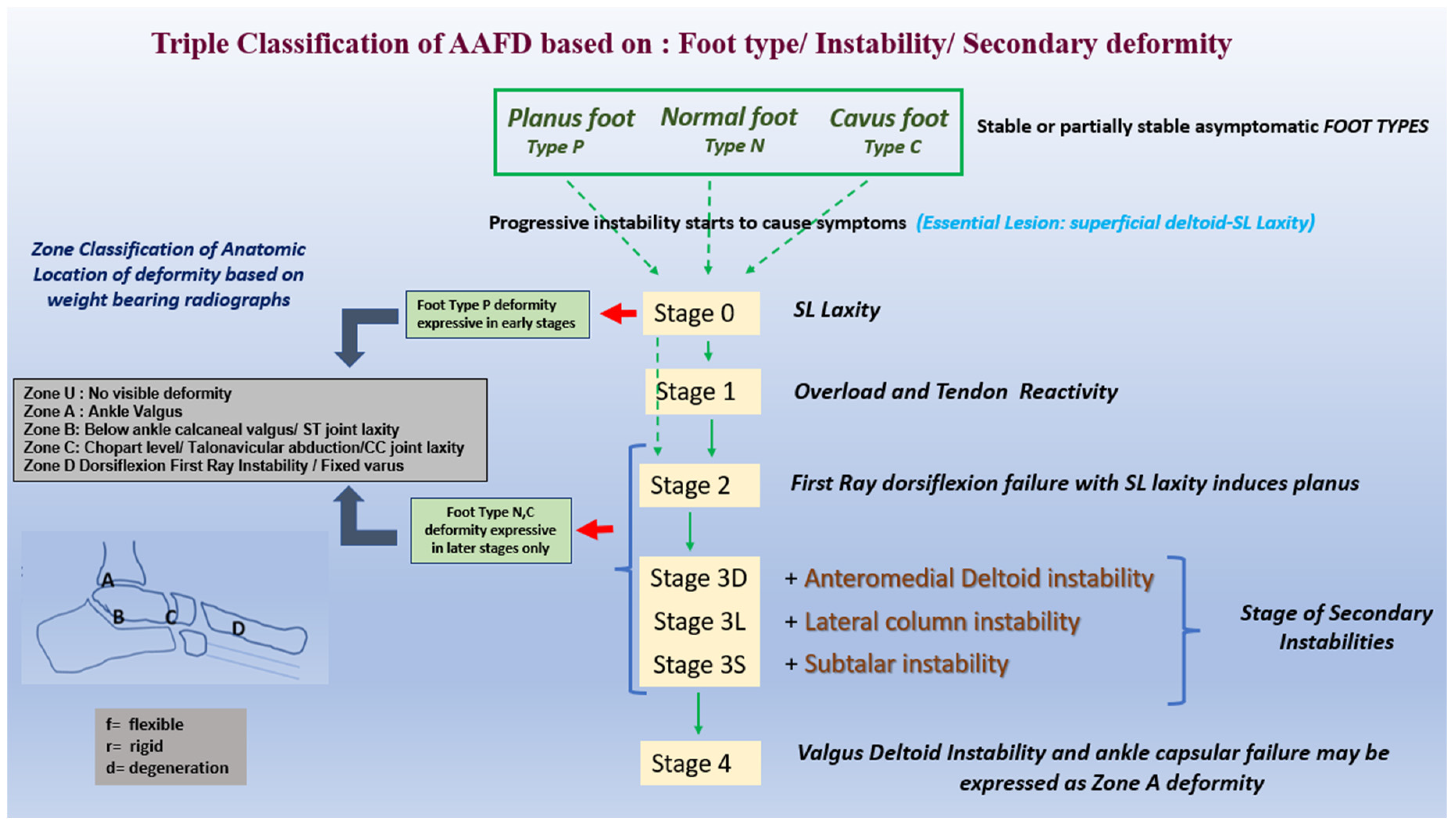

4.2. Triple classification: Foot Type/Stage of Instability / Zone of deformity

4.2.1. TC foot type

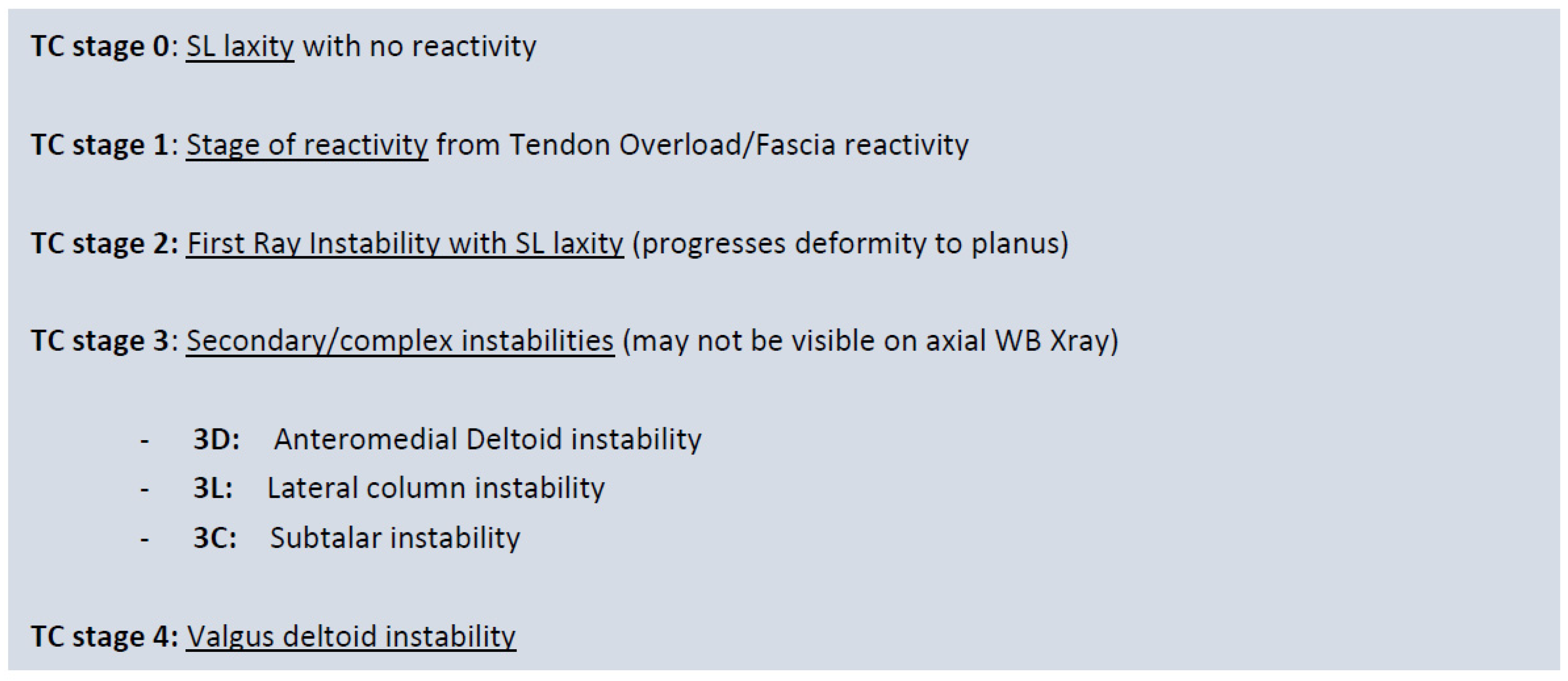

4.2.2. TC stage based on instability

- TC stage 0:

-

Loss of SL integrity leads to TN abduction laxity (see above), allowing the potential for foot progression into planus (and development of secondary instabilities). SL integrity loss may arise primarily due to superficial deltoid or plantar fascia integrity loss. Assessing strain in these two structures may be more difficult to clinically ascertain. First, ray stability resists planus, and thus planus is not present on examination. This is the earliest isolated flatfoot lesion that can be clinically identified.

- -

- Neutral Heel lateral push test (NHLT) positive

- -

- The first ray is stable

- TC stage 1:

-

Reactive phase of the foot. Instability with biomechanical overload causes tendons and fascia to react prior to planus. SL laxity predisposes the foot to progressive collapse, but the stable first ray prevents planus. We believe the PF reactivity may represent an early warning sign. However, this stage of early foot reactivity may not be present in all feet with progressive collapse. Its presence alludes to the presence of instability

- -

- Above with tender reactive TP/PLT and plantar fascia

- TC stage 2:

-

First ray dorsal sagittal failure (TMT commonly and/or NC joints) secondary to SL laxity(type 1 FRI) is the hallmark of stage 2 pathology. Stability in this acts as a secondary stabiliser to planus. FRI with a lax/unlocking of the TN joint (SL laxity) progresses the foot into the planus. (a common stage/clinical scenario seen).

- -

- SL instability: Positive NHLT

- -

- FRI / dorsiflexion (Roots manoeuvre, Morton's test, Double dorsiflexion test)

- TC stage 3:

-

Secondary foot complex foot instabilities are present. Foot instability is no longer isolated to the TN joint and the first ray but begins to demonstrate more widespread instability at the ankle joint, the lateral column and/or the subtalar joint. Anteromedial ankle instability is secondary to superficial and deep deltoid failure, lateral column instability due to LPL strain [4] and subtalar instability from interosseous strain. These instabilities represent a more widespread foot ligament failure/involvement. Instabilities that have arisen beyond the medial column (SL and first ray inability) are explicitly stated, e.g. Stage 3 D (deltoid) or Stage 3DS(deltoid and subtalar).

- -

- [L] Lateral column ballottement compared to the contralateral side

- -

- [D] Anteromedial ankle draw test for deep deltoid

- -

- Heel external rotation test for deep deltoid instability

- -

- [S] Anterior draw for subtalar instability

- TC stage 4:

- Deep deltoid failure with capsular failure. The ankle progresses into the valgus. The assessment of instability is clinical and radiographic. Deformity helps anatomical localisation of ligament deficits.

4.3. Overview diagram of the Triple classification system

5. Conclusions

Funding

References

- Johnson K, Strom D. Tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 1989;239. [CrossRef]

- Jeng C, Myerson M. The use of tendon transfers to correct paralytic deformity of the foot and ankle. Foot and Ankle Clinics 2004;9:319–37. [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-De la Portilla C, Larrainzar-Garijo R, Bayod J. Analysis of the main passive soft tissues associated with adult acquired Flatfoot Deformity Development: A computational modelling approach. Journal of Biomechanics. 2019;84:183–90. [CrossRef]

- Crary JL, Hollis JM, Manoli A. The effect of plantar fascia release on strain in the spring and long plantar ligaments. Foot & Ankle International 2003;24:245–50. [CrossRef]

- Mizel MS, Temple HT, Scranton PE, Gellman RE, Hecht PJ, Horton GA, et al. Role of the Peroneal tendons in producing the deformed foot with posterior tibial tendon deficiency. Foot & Ankle International 1999;20:285–9. [CrossRef]

- Yeap JS, Birch R, Singh D. Long-term results of tibialis posterior tendon transfer for drop-foot. International Orthopaedics 2001;25:114–8. [CrossRef]

- Pecheva M, Devany A, Nourallah B, Cutts S, Pasapula C. Long-term follow-up of patients undergoing tibialis posterior transfer: Is acquired PES Planus a complication? The Foot 2018;34:83–9. [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-De la Portilla C, Pasapula C, Larrainzar-Garijo R, Bayod J. Finite element analysis of secondary effect of midfoot fusions on the spring ligament in the management of adult acquired flatfoot. Clinical Biomechanics 2020;76:105018. [CrossRef]

- Dyal CM, Feder J, Deland JT, Thompson FM. PES planus in patients with posterior tibial tendon insufficiency: Asymptomatic versus symptomatic foot. Foot & Ankle International 1997;18:85–8. [CrossRef]

- Myerson MS, Thordarson DB, Johnson JE, Hintermann B, Sangeorzan BJ, Deland JT, et al. Classification and nomenclature: Progressive collapsing foot deformity. Foot & Ankle International 2020;41:1271–6. [CrossRef]

- Pasapula C, Cutts S. Modern theory of the development of adult acquired Flat Foot and an updated spring ligament classification system. Clinical Research on Foot & Ankle 2017;05. [CrossRef]

- Bluman EM, Title CI, Myerson MS. Posterior tibial tendon rupture: A refined classification system. Foot and Ankle Clinics 2007;12:233–49. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Zhu M, Gu W, Hamati M, Hunt KJ, de Cesar Netto C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the progressive collapsing foot deformity (PCFD) classification. Foot & Ankle International 2022;43:800–9. [CrossRef]

- Chiang CY, Lin KW, Yang WW, Chang YC, Chou LW. Changes in lower extremity biomechanics and muscle activity after six-minute fast-walk in individuals with flatfoot. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 2018;61. [CrossRef]

- Lalevée M, Barbachan Mansur NS, Lee HY, Ehret A, Tazegul T, de Carvalho KA, et al. A comparison between the bluman et al. and the progressive collapsing foot deformity classifications for flatfeet assessment. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-De la Portilla C, Pasapula C, Gutiérrez-Narvarte B, Larrainzar-Garijo R, Bayod J. Peroneus longus overload caused by soft tissue deficiencies associated with early adult acquired Flatfoot: A finite element analysis. Clinical Biomechanics 2021;86:105383. [CrossRef]

- Huang C-K, Kitaoka HB, An K-N, Chao EY. Biomechanical evaluation of Longitudinal Arch Stability. Foot & Ankle 1993;14:353–7. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka K, Kudo S. Functional assessment of the spring ligament using ultrasonography in the Japanese population. The Foot 2020;44:101665. [CrossRef]

- Pasapula C, Kiliyanpilakkil B, Khan DZ, Di Marco Barros R, Kim S, Ali AM, et al. Plantar fasciitis: Talonavicular instability/spring ligament failure as the driving force behind its histological pathogenesis. The Foot 2021;46:101703. [CrossRef]

- Graham ME, Kolodziej L, Kimmel HM. The Frequency of Association between Pathologic Subtalar Joint Alignment in Patients with Recalcitrant Plantar Fasciopathy-A Retrospective Radiographic Evaluation. Clinical Research on Foot & Ankle 2019;7:2. [CrossRef]

- McMillan AM, Landorf KB, Gilheany MF, Bird AR, Morrow AD, Menz HB. Ultrasound guided corticosteroid injection for plantar fasciitis: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2012;344. [CrossRef]

- Wong DW-C, Wang Y, Leung AK-L, Yang M, Zhang M. Finite element simulation on posterior tibial tendinopathy: Load transfer alteration and implications to the onset of PES Planus. Clinical Biomechanics 2018;51:10–6. [CrossRef]

- Robberecht J, Shah DS, Taylan O, Natsakis T, Vandeputte G, Vander Sloten J, et al. The role of medial ligaments and tibialis posterior in stabilising the medial longitudinal foot arch: A cadaveric gait simulator study. Foot and Ankle Surgery 2022;28:906–11. [CrossRef]

- Gatens PF, Saeed MA. Electromyographic findings in the intrinsic muscles of normal feet. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1982;63(7):317-318. [PubMed]

- Ringleb SI, Kavros SJ, Kotajarvi BR, Hansen DK, Kitaoka HB, Kaufman KR. Changes in gait associated with acute stage II posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Gait & Posture 2007;25:555–64. [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-De la Portilla C, Larrainzar-Garijo R, Bayod J. Biomechanical stress analysis of the main soft tissues associated with the development of adult acquired Flatfoot Deformity. Clinical Biomechanics 2019;61:163–71. [CrossRef]

- Amaha K, Nimura A, Yamaguchi R, Kampan N, Tasaki A, Yamaguchi K, et al. Anatomic study of the medial side of the ankle base on the joint capsule: An alternative description of the deltoid and spring ligament. Journal of Experimental Orthopaedics 2019;6. [CrossRef]

- Pasapula C, Devany A, Magan A, Memarzadeh A, Pasters V, Shariff S. Neutral heel lateral push test: The first clinical examination of Spring ligament integrity. The Foot 2015;25:69–74. [CrossRef]

- Jennings MM, Christensen JC. The effects of sectioning the spring ligament on rearfoot stability and posterior tibial tendon efficiency. The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery 2008;47:219–24. [CrossRef]

- Pate M, Hall J, Albright P, Bohay D, Anderson J, Roberts J. Increasing values of the lateral talar-first metatarsal angle preoperatively predict spring ligament attenuation in adult acquired flat foot deformity. Foot & Ankle Orthopaedics 2019;4. [CrossRef]

- Pasapula C, Ali AMS, Kiliyanpilakkil B, Hardcastle A, Koundu M, Gharooni A-A, et al. High incidence of spring ligament laxity in ankle fractures with complete deltoid ruptures and secondary first ray instability. The Foot 2021;46:101720. [CrossRef]

- Baxter JR, LaMothe JM, Walls RJ, Prado MP, Gilbert SL, Deland JT. Reconstruction of the medial talonavicular joint in simulated flatfoot deformity. Foot & Ankle International 2014;36:424–9. [CrossRef]

- Chu I-T, Myerson MS, Nyska M, Parks BG. Experimental flatfoot model: The contribution of dynamic loading. Foot & Ankle International 2001;22:220–5. [CrossRef]

- Wiegerinck JJ, Stufkens SA. Deltoid rupture in ankle fractures. Foot and Ankle Clinics 2021;26:361–71. [CrossRef]

- Chrastek D, Elmousili M, Al-Sukaini A, Austin I, Pasapula C. Quantiative assessment of dorsal sagittal lateral column instability in unilateral adult acquired Flatfoot Deformity (AAFD). British Orthopaedic Association Conference 2021. [CrossRef]

- Michelson JD, Varner KE, Checcone M. Diagnosing deltoid injury in ankle fractures. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 2001;387:178–82. [CrossRef]

- Femino JE, Vaseenon T, Phistkul P, Tochigi Y, Anderson DD, Amendola A. Varus external rotation stress test for radiographic detection of deep deltoid ligament disruption with and without syndesmotic disruption. Foot & Ankle International 2013;34:251–60. [CrossRef]

- De Cesar Netto C, Saito GH, Roney A, Roberts L, Fansa A, Greditzer H, et al. Weightbearing CT and MRI findings of Stage II flatfoot deformity: Can we predict patients at high- risk for foot collapse? Foot & Ankle Orthopaedics 2019;4. [CrossRef]

- Michels F, Clockaerts S, Van Der Bauwhede J, Stockmans F, Matricali G. Does subtalar instability really exist? A systematic review. Foot and Ankle Surgery 2020;26:119–27. [CrossRef]

- Kato, T. The diagnosis and treatment of instability of the subtalar joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(3):400-406. [PubMed]

- Lee HY, Barbachan Mansur NS, Lalevée M, Dibbern KN, Myerson MS, Ellis SJ, et al. Intra- and Interobserver reliability of the new classification system of progressive collapsing foot deformity. Foot & Ankle International 2021;43:582–9. [CrossRef]

- Raikin SM, Winters BS, Daniel JN. The RAM classification: a novel, systematic approach to the adult-acquired flatfoot. Foot and Ankle Clinics 2012;17:169–81. [CrossRef]

- Parsons S, Naim S, Richards PJ, McBride D. Correction and prevention of deformity in type II tibialis posterior dysfunction. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research 2010;468:1025–32. [CrossRef]

- Myerson, MS. Adult acquired flatfoot deformity: treatment of dysfunction of the posterior tibial tendon. Instr Course Lect. 1997;46:393-405.

- Weinraub GM, Saraiya MJ. Adult flatfoot/posterior tibial tendon dysfunction: Classification and treatment. Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery 2002;19:345–70. [CrossRef]

- Boakye LA, Uzosike AC, Bluman EM. Progressive collapsing foot deformity: Should we be staging it differently? Foot and Ankle Clinics 2021;26:417–25. [CrossRef]

- Deland, JT. Adult-acquired Flatfoot Deformity. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2008;16:399–406. [CrossRef]

| Stage of deformity | ||

|---|---|---|

| Stage I (flexible) or Stage II (rigid) | ||

| Type of deformity | ||

| Deformity type/location | Clinical/radiographic findings | |

| Class A | Hindfoot valgus deformity | Hindfoot valgus alignment Increased hindfoot moment arm, hindfoot alignment ankle, foot and ankle offset |

| Class B | Midfoot/forefoot abduction deformity | Decreased talar head coverage Increased talonavicular coverage angle Presence of sinus tarsi impingement |

| Class C | Forefoot varus deformity/medial column instability | Increased talus-first metatarsal angle Plantar gapping first tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint / naviculocuneiform (NC) joints Clinical forefoot varus |

| Class D | Peritalar subluxation/dislocation | Significant subtalar joint subluxation/sub-fibular impingement |

| Class E | Ankle instability | Valgus tilting of the ankle joint |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).