1. Introduction

The occlusion of visual items in 2D data visualization techniques is an old problem that can be observed in many studies present in the literature [

1,

2,

3]. The occlusion issue is generally exacerbated due to the visual space available to present the data and the amount of data to be displayed. According to the level of occlusion increases, the user´s perception of visual data can be affected, causing data misinterpretation or even a loss of relevant information [

4].

From most previous studies, it is possible to highlight that they mainly focused on the issue of reducing the occlusion effect for visual items on data visualization techniques [

5,

6,

7]. Some solutions found are Random Jitter [

8]; Transparency Technique [

9]; Layout Reconfiguration [

10]; Focus+Context Techniques [

11]; Multiple Views [

12]; etc.

Studies within psychology indicate that humans have mechanisms for recognizing partially occluded objects even in reduced sizes and low resolution [

13]. However, [

14] demonstrated that the recognition capacity of human beings decreases at higher levels of occlusion. Some research outside psychology has also suggested limits for occlusion levels tolerable for the human brain in detecting and identifying efficiently partially overlapped visual elements [

2]. In general, clues about the efficiency and effectiveness of partially occluded visual variables in information visualization are split across multiple articles, making it difficult to compare and use the correct visual variable for a given data visualization scenario.

Thus, this research aims to present a comparative study on the perception of partially occluded visual variables in data visualization techniques, indicating how much the visual variable can be occluded and how many values it can encode in this condition. The results can be used as a set of good practices to apply visual variables in scenarios where occlusion is unavoidable, increase the visual items in data visualization technique, or even be used as an indicator to compose quality criteria to evaluate data visualization techniques concerning the perception of their visual items. It should be noted that this study is an extension of research presented in [

15] which describes in detail the preliminary tests and initial results presented in the previous analysis.

The comparative study proposal between visual variables partially occluded is based on the location tasks for a visual target [

16], focuses on categorical data representations, considering Hue, Lightness, Saturation, Shape, Text, Orientation, and Texture visual variables. To support the comparative study, a computational application was developed to generate random grid layout scenarios with 160 positions (10 x16), where each grid element presents one encoded value (from 3 to 5 values) of one visual variable, also including a gray square in the center of the grid element representing the level of partial overlap that should be applied to the visual item (0% (control), 50%, 60%, and 70%), and is generated one visual target as the task aim. The test involved 48 participants organized into four groups of 12 participants, with 126 tasks per participant, and the application captured the response and time for each task performed.

The result analysis indicates that the Hue, Lightness, and Shape visual variables maintain good accuracy and time performance for location tasks, even with 70% partial overlapping and five values encoded. For the Text and Texture visual variables, the results showed good accuracy for partial overlap until 60% and until four values encoded, and the time performance of the Text visual variable was a little bit better compared to the Texture variable. Only the 50% partial overlapping and three values encoded scenario for the Saturation variable showed good accuracy and time performance. At last, the Orientation variable got the worse accuracy and performance results for all partial overlap percentages and the number of values encoded. However, the control group showed similar problems, which suggests reviewing the visual encodes used.

This article is organized as follows: Theoretical Foundation presents the concepts related to the development of this study; Related Works lists previous studies that address the perception of visual variables and analyses from partial overlapping of elements; Methodology presents the methodological decisions and protocols used in the configuration and execution of the tests in this research; Results presents the results obtained and describes the collected data; Discussion summarizes the main extracted results and highlights the recurring comments made by the participants; Final Remarks and Future Works provides the final considerations regarding this research and lists some possibilities for future works.

3. Related Works

For the development of this research, studies with the following characteristics were analyzed: tests of visual variable perception, object recognition with partial overlap, and applications or techniques that utilize partially overlapping visual objects. The studies that aimed to mitigate the impact of partial overlap were not selected.

Groop and Cole [

28] evaluated two overlapping approaches based on the circle size. In the first approach, the overlapping circles were cut to fit together (sectioned), and in the second one, the transparency technique was applied to the overlapping circles. As a result, it was observed that the transparency proposal performed better.

Cleveland [

29] conducted perception tests in its research with ten visual variables (Common Scale Position, Position Unaligned Scale, Length, Direction, Angle, Area, Volume, Curvature, Shading, and Saturation) to determine which visual variables best represent a set of quantitative data.

The authors in [

21] presented another classification based on visual perception evaluations using 12 visual variables (Position, Length, Angle, Slope, Area, Volume, Density, Saturation, Hue, Texture, Connection, Containment, and Shape). The classification was organized using three categories of data: quantitative, ordinal, and categorical. For the study proposal in this paper, we focus only on visual variables mapped categorical data.

Graham [

30] in his study describes the challenges of visualizing structural changes in hierarchical techniques. The author suggested combining Hue and Shape visual variables to represent the leaf nodes in a tree diagram.

In the research presented by [

23], an analysis was conducted based on visual perception tests involving visual variables when applied for tasks of selection, association, ordering, etc. Bertin [

17] was the source for the visual variables used. Focusing on the research presented in this article, a high level of visual perception was observed for the Hue, Texture, and Orientation visual variables when used in selection tasks.

Carpendale [

23] conducted a visual perception tests involving visual variables to tasks of selection, association, ordering, etc. Bertin [

17] was the source for the visual variables used. As a result, it was highlighted a high level of visual perception for the Hue, Texture, and Orientation visual variables when used in selection tasks.

Theron [

31] proposed multidimensional glyphs to depict information about cinematographic dataset, where each component of the glyph represents a function performed by a member of a film’s cast. The author created glyphs that are composed by vary elements (shapes) overlapping, and each inserted element encode a dataset attribute.

In the study presented by [

22] conducted visual perception tests involving the Text, Area, Rectangles, Lightness, and Angle visual variables were administered. This study highlighted a good performance of the Text visual variable on the tests.

Brath [

32] applied multidimensional glyphs in Venn and Euler diagrams. The author analyzed how combined Hue and Texture visual variables affected the user’s visual perception. The obtained results indicate that the use of multidimensional glyphs for visual mapping of multiple attributes of a dataset can be effective.

In research conducted by [

33], the Hue, Shape, and Size visual variables were combined and evaluated in similarity and comparison tasks. The results indicated good performance for Hue and Shape visual variables used together.

Soares proposed in his study [

34] a multidimensional layer glyph concept, in which one visual variable overlays on another in some percentage, such that the visual variable in the top layer partially hides the visual variable in the lower layer. The author conducted visual perception tests for the glyph components, and the data collected was analyzed by a decision tree algorithm, which generated good rules to build the multidimensional layer glyph, including the level of partial overlap and visual variables for each layer. The author’s suggested glyphs were utilized in conjunction with the Treemap technique.

Korpi says in his study [

2] that, despite evidence that humans can extract information from partially overlapping objects, no research indicated which level of partial overlap a visual variable could have and still communicate information. Our study shares quite the same motivation as this one.

The visual perception tests have used three visual variables (Color, Shape, and Pictograms) with equal dimensions for four partial overlap levels ( 0%, 25%, 50%, and 75%) in cartography scenarios (maps) [

2]. The results indicated that the Hue visual variable with 75% partial overlapping maintains good communication, and the Shape visual variable with 50% partial overlap had similar performance compared to the Pictogram visual variable without overlapping. Additionally, the author suggests that Pictograms could be combined with a Hue visual variable to improve their visual perception.

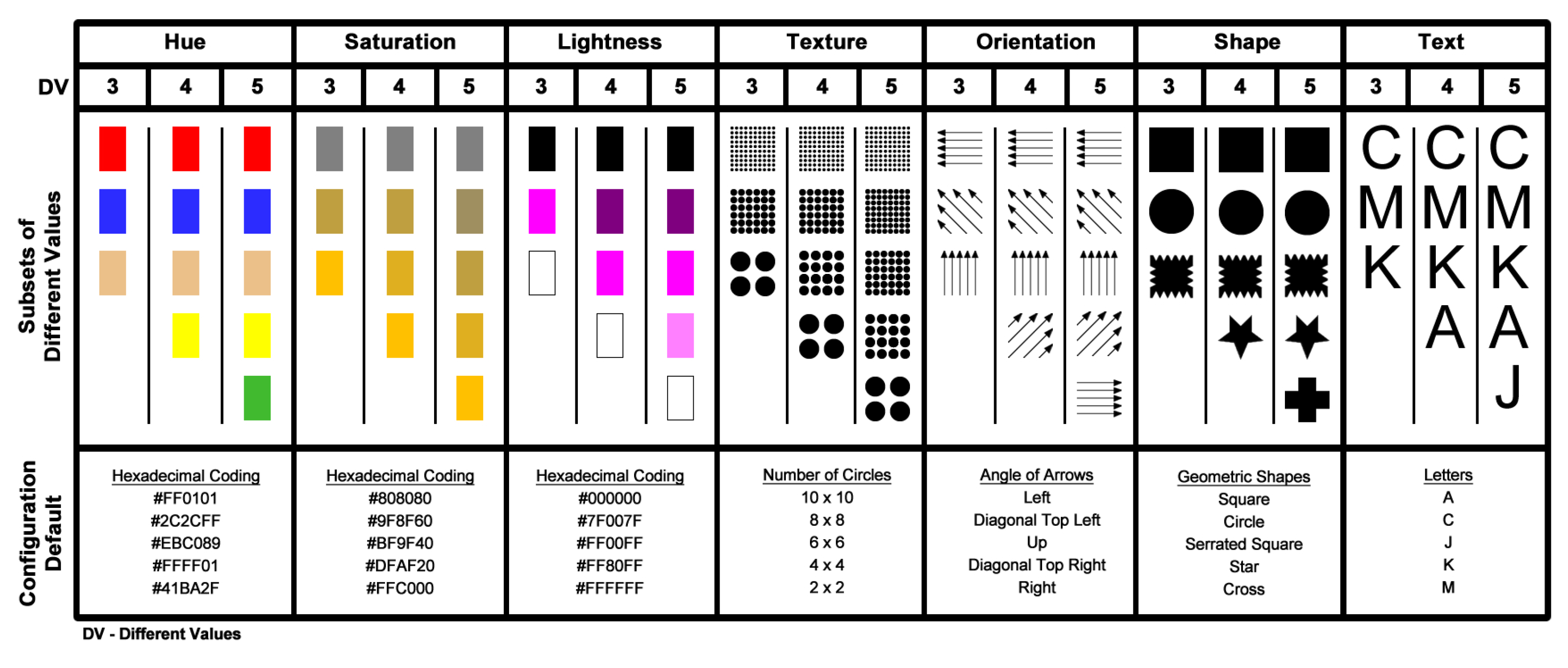

This study evaluates the robustness of visual variables to different visual encoding values (3, 4, and 5 different values) and different levels of partial overlap (0% (control group), 50%, 60%, and 70%).

Seven visual variables were selected from the literature: Hue, Lightness, Saturation, Shape, Text, Orientation, and Texture. These visual variables were chosen due to their widespread use, evaluation, and application within the field of information visualization [

2,

17,

21,

30,

33] . The numbers of different visual encoding values were defined based on the research presented by [

23], in which the author indicates that these quantities can be effectively interpreted in scenarios without partial overlap.

The levels of partial overlap were defined based on Korpi [

2] and Soares [

34]. The first demonstrated that a visual variable could efficiently communicate information with 50% partial overlap. The second one presented results showing that visual variable recognition decreases significantly with 80% partial overlap.

4. Methodology

In this section, all protocols followed for conducting the evaluation tests in this study will be described, such as the developed visualization scenarios, the computational environment used, the participants’ profiles, and the applied evaluation scenarios.

4.1. Evaluation Procedure

The evaluation was conducted in a closed, climatized room with artificial lighting, where the participant was accompanied only by an evaluation facilitator. In addition, the distance between the monitor and the participants’ eyes was approximately 70 cm, and the chair used by the participants had armrests and a backrest.

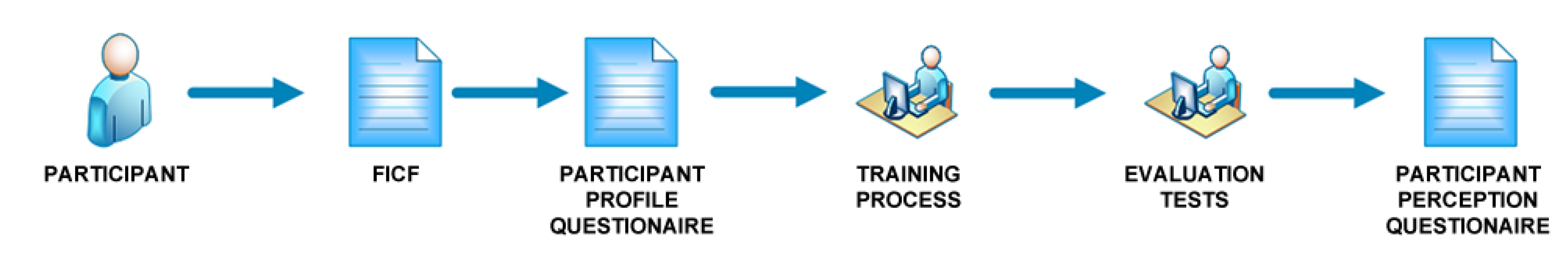

Before starting the test, the participant was invited to sign the FICF (Free and Informed Consent Form), where they were informed about the test goal, the data collected during the tests would be used anonymously, that they could withdraw from the tests at any time, regardless of the reason, and to fill out a screening questionnaire with information about their age, gender, educational level, and restriction to identify colors. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of 18-UFPA—Institute of Health Sciences of the Federal University of Pará (15522319.2.0000.0018 and 03/10/2019).

Since three of the analyzed visual variables refer to color (Hue, Lightness, and Saturation), if the participant claimed to have difficulty identifying colors, the participant could not participate in the test.

After participants responded to the digital questionnaire, a training stage was provided to inform the research objective and provide instructions on how the test would be applied. In the training stage, the participants were introduced to the application used in the test. At this point, six visualizations scenarios were presented to demonstrate to the participant how to answer the tasks during the test. After the training, the test began.

After completing the tasks proposal, a questionnaire containing questions about the participants’ perception of visual variables and their different visual encoding values was applied to collect data for analysis. The same sequence of stages was followed when conducting the initial tests [

15] and when conducting the tests for this research. The flow of the general procedure adopted for the evaluation carried out in this study can be seen in

Figure 1.

4.2. Participants Profile

The tests conducted in this study involved 48 participants, all of them from the academic community from the Federal University of Pará, aged between 18 and 42 years old, with education levels ranging from incomplete undergraduate to Ph.D., and belonging to various fields of knowledge, such as administration, biomedicine, natural sciences, computer science, etc. No participants declared to have any difficulty related to color identification. No specific knowledge was required to participate in the study, such as the concept of visual variables or information visualization techniques.

4.3. Computing Environment

A computer with 8GB of RAM, 1TB HD, and an Intel Core i7 processor was used to perform the tests. A 21" monitor with a 1920 x 1080 pixels resolution was also used in landscape orientation.

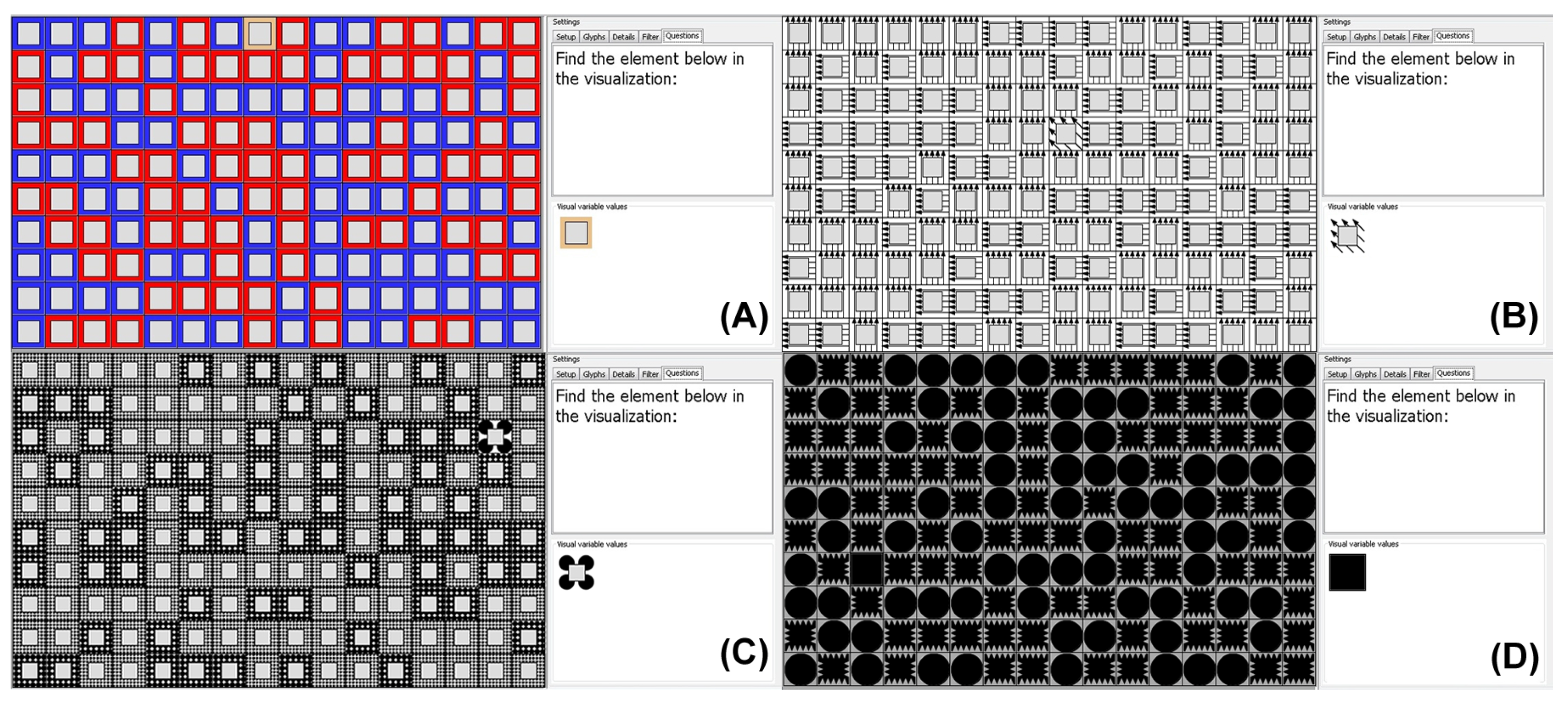

The application developed for this study presents the visual variables in a 10 x 16 grid layout. The visual elements that compose each visualization are randomly generated, varying the type of visual variable, the percentage of partial occlusion, and the number of distinct encoded values. Examples of visualization scenarios used to perform the evaluation tests can be seen in

Figure 2.

Each evaluation task had a total of 160 elements containing only one distinct visual element (target iem), varying the percentage of partial overlap level, the type of visual variable, and the number of different visual encoding values, as can be seen in

Figure 2.

The visualizations scenarios generated for the tests have a grid area size of 480x768 pixels. The size of each grid element was based on results presented by [

34], where a decision tree algorithm applied on visual variables perception dataset considering different area sizes pointed out that the minimum area to perceive clearly visual variables would be 48 x 48 pixels.

Figure 3 shows the visual variables and their respective visual values used in this study.

4.4. Test Procedure

As general rules for conducting the tests, it was defined that participants should know the visual characteristics of the target element and be unaware of its location. For this, a visual element model should be presented for searching in all locate tasks performed by the participant.

This configuration was defined based on the taxonomy defined in [

16], where different types of search tasks are defined. For this study, the type of search task defined was Locate, which consists having prior knowledge about visual characteristics of the target element but without knowing any information about its location.

Based on pilot tests, it was possible to define some specifications regarding the composition of visual variables and the time to complete each task, as described below:

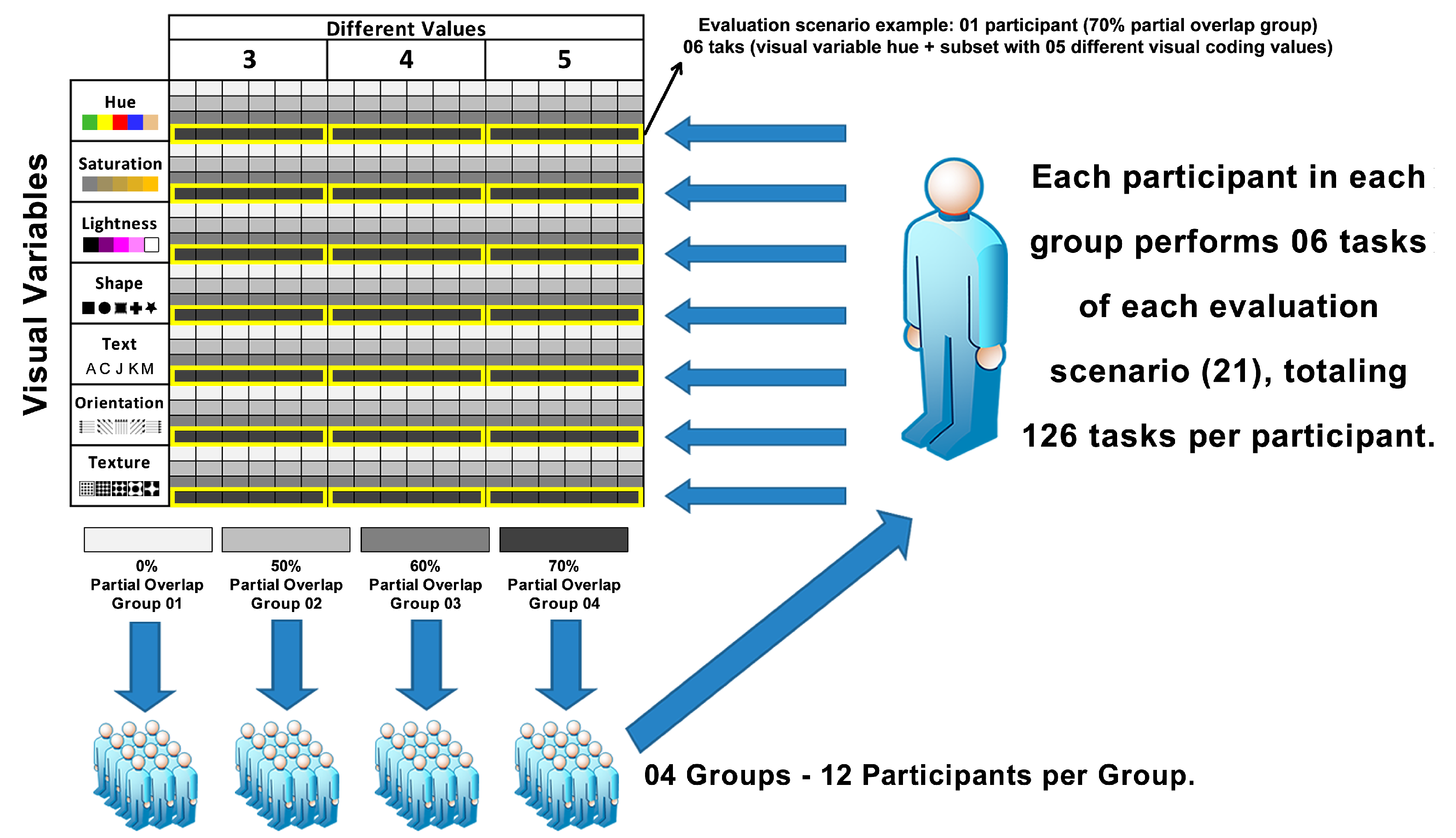

The test was designed as a mixed-design study [

25] with 3 independent variables:

Visual variables: Hue, Lightness, Saturation, Texture, Orientation, Shape, and Text;

Partial overlap levels: 0%, 50%, 60% and 70%;

Number of different visual encoding values: 3, 4 and 5.

The participants were divided into four groups of 12 individuals, as suggested in [

25] for a Between-Subjects design. The independent variables (visual variables and the number of distinct values) were permuted in 21 evaluations scenarios (visual variable x number of different visual encoding values x partial overlap level) and organized in a Within-Subject design [

25]. For each evaluation scenario (21), the participant performed six (6) tasks, resulting in 126 tasks per participant.

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of the independent variables over the tasks.

The following data were captured automatically for each test scenario:

The level of partial overlap applied;

The number of different visual encoding values per visual variable;

The visual variable type;

The target visual element and its characteristics;

The participant answer: click on the correct item, click on the erroneous item, or no answer (time out);

Task resolution time, which is quantified in seconds.

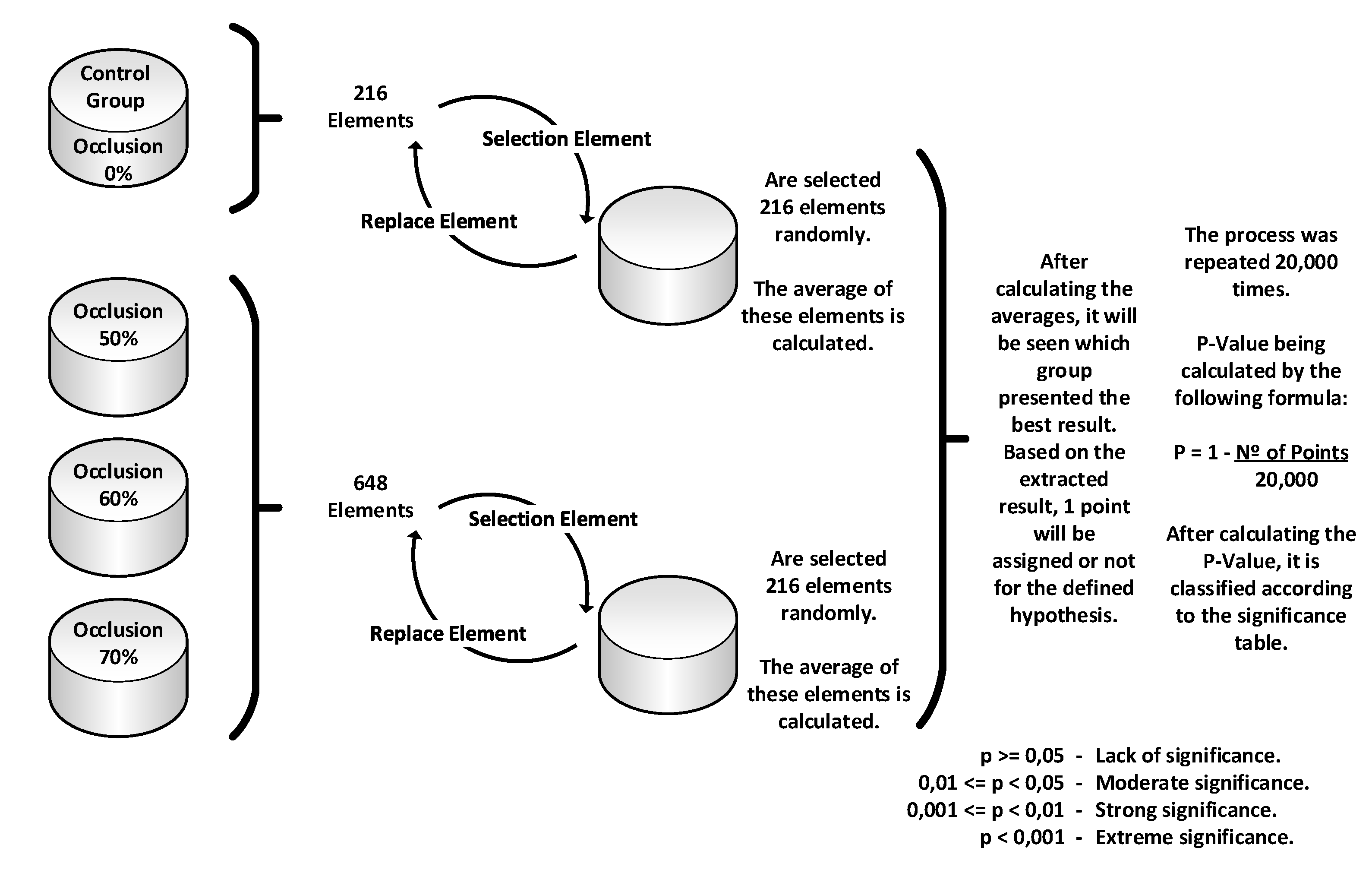

4.5. Statistical Analysis

The sampling with replacement bootstrap method was applied to the data collected from the tests. The bootstrap method was chosen because of its simplicity, the possibility to use the method for complex distribution with many strata (visual variables, different visual encoding values, and different partial overlap levels), and provide accurate confidence intervals [

35].

As from the proposed test scenarios, two hypotheses are considered:

Alternative Hypothesis () - the performance analyzed from the overlap level (highest accuracy) and the resolution time (quickest resolution time) for the control group (0% occlusion) must return the best results;

Null Hypothesis () - that the application of occlusion would not affect accuracy and resolution time.

The procedures followed by the sampling with replacement bootstrap algorithm, developed in the R programming language, are shown in

Figure 5:

The control group (0% occlusion) with 216 elements per visual variable was separated from the other groups (50%, 60%, and 70% occlusion) with 648 elements in total;

The algorithm then drew 216 elements at random from each of the groups, always replacing the previously drawn element;

After the simulation’s final drawing round of 216 elements (for each group), the algorithm calculates the average of each group;

If the control group value obtained were greater than that of the other occlusion levels group, then the alternative hypothesis would receive one point;

According to [

25], this procedure was repeated 20,000 times for each analyzed variable;

P-Value calculation: P = (1 - number of points) / 20.000;

P-Value classifying: lack of significance (p >= 0,05), moderate significance (0,01 <= p < 0,05), strong significance (0,001 <= p < 0,01), and extreme significance (p < 0,001).

4.6. Evaluation Scenarios

The tasks’ precision and resolution time scenarios are considered for result analysis based on automatic logs. Moreover, a qualitative evaluation of participant’s perception of the visual variables partially overlapped was conduct

For the accuracy analysis, three situations were considered: TRUE, when the element selected by the participants corresponded to the correct answer; ERROR, when the visual element chosen by the participant is an incorrect response; and TIMEOUT, when the 30-second timeout occurred. In addition, each type of answer was analyzed separately concerning the combinations of visual variables, partial overlap levels, and different visual encoding values.

Considering the partial overlap, a questionnaire was applied to collect participants’ opinions about the perception concerning visual variables and their visual encodes. The participants could classify the following items: the recognition facility of visual variables, the difficulty category of visual variables (good, medium, or poor), and point out which visual encodes presented poor perception.

The following scale was utilized to classify the performance of the visual variables qualitatively by participants:

GOOD - All variables with an mean accuracy greater than 95%;

MEDIUM - Visual variables with mean accuracy values between 90% and 95%;

POOR - Visual variables with mean accuracy values of less than 90%.

In summary, the proposed analysis scenarios were:

Accuracy per resolution time;

Visual variables error rates;

Classification of difficulty in identifying visual variables;

Visual variables ranking based on participant perceptions;

Analysis of visual encode values performance.

6. Discussion

This section presents a summary of the study’s findings for each of the visual variables analyzed.

6.1. Hue

For all proposed analysis scenarios involving partially overlapping levels and subsets of different visual encoding values, the Hue visual variable proved to be robust. The visual variable with the lowest number of identification errors (testing tool) and participant observations (questionnaires) regarding identification difficulty.

After the analyses conducted in this study, the Hue visual variable was ranked as the most robust visual variable considering a gradual increase in partial overlap level and the number of different visual encoding values. Its mean accuracy was between 99.6% and 100% (GOOD).

6.2. Lightness

The Lightness visual variable got a high robustness level, close to the Hue visual variable accuracy result. Its mean accuracy reached 99% (GOOD), not showing increased identification problems in any evaluation scenario proposed. A total number of seven errors were recorded during the evaluation tests, which means two percent of all global data collection errors. Regarding overall performance, lightness ranked second among the studied visual variables.

The difference between the results extracted from the data collected via the test tool and applied questionnaires is emphasized. More records (57 records) from participants were observed than the data collected via the test tool (seven errors). Even though participants reported a small degree of difficulty in identifying the visual coding values, the Lightness visual variable presented a high level of accuracy for mapping categorical data in all evaluation scenarios proposed in this study.

6.3. Shape

The Shape visual variable presents a high level of robustness for all percentage levels of partial overlap, with a minor increase in resolution time compared to the scenario without partial overlap (control group). However, most errors with the Shape visual variable occurred in scenarios where the Cross visual value represented the visual target, which was also reflected in the analysis of the participant’s opinions.

Eleven participants registered difficulty in locating the Cross visual coding value when it was adjacent to elements encoding the Square value. Nevertheless, the Shape visual variable exhibited 12 errors during the evaluation tests, representing just three percent of global errors. Finally, the Shape visual variable ranked third among the visual variables analyzed, with a mean accuracy ranging from 98% and 99% (GOOD).

6.4. Text

When analyzing the scenario without partial overlap, the Text visual variable had the highest accuracy (100%) among the visual variables studied. It obtained good results, with a slightly negative effect on mean accuracy and resolution time as the level of partial overlap increased, and its mean accuracy varied between 90% and 100% (varying between MEDIUM and GOOD). In terms of performance, it ranked fourth among the studied visual variables.

Most participants in groups with overlapping levels could not easily locate the "K" visual item. This identification difficulty can be explained by the fact that the letter "K" has a rectangular shape similar to the overlapping element used in this study (gray square). Participants noted that the visible portions of the "K" visual item were more challenging to locate than those of the other letters.

This analysis may suggest that the Text visual variable overlapped with a polygon approximating the shape of the encoded value may impair the participant’s visual perception; however, additional research with different overlap shapes is required to reach more conclusive results.

It is worth highlighting that the Text visual variable was the one that most diverged from the results found in the consulted literature [

22], as its performance in scenarios with partial overlap levels performed better than expected.

6.5. Texture

The accuracy and resolution time results of the Texture visual variable ranged from POOR to MEDIUM (88% to 91%), placing it fifth in performance among the visual variables studied.

From the questionnaires, it can be seen that the Texture visual variable with the most divergent opinions. The participants identified the visual items 6x6, 8x8, and 10x10 circles as having a more difficult identification level. It is also important to observe that there were no comments regarding coding 2x2 circles.

It was found that the 2x2 and 4x4 circle encodings were the easiest to identify. These results suggest that fewer Texture encodings are simpler to distinguish, which is supported by the low error rate when the visual variable maps only three distinct values (See Figure 31).

Even so, good performance can be obtained for the subset in which four different visual encoding values were used for the Texture visual variable (2x2, 4x4, 6x6, and 10x10 circles), as the number of test-related errors is reduced.

Lastly, the results suggest that the Texture variable for those encoded values is not a robust visual variable when considering the gradual increase in the number of different visual encoding values and percentage of partial overlaps.

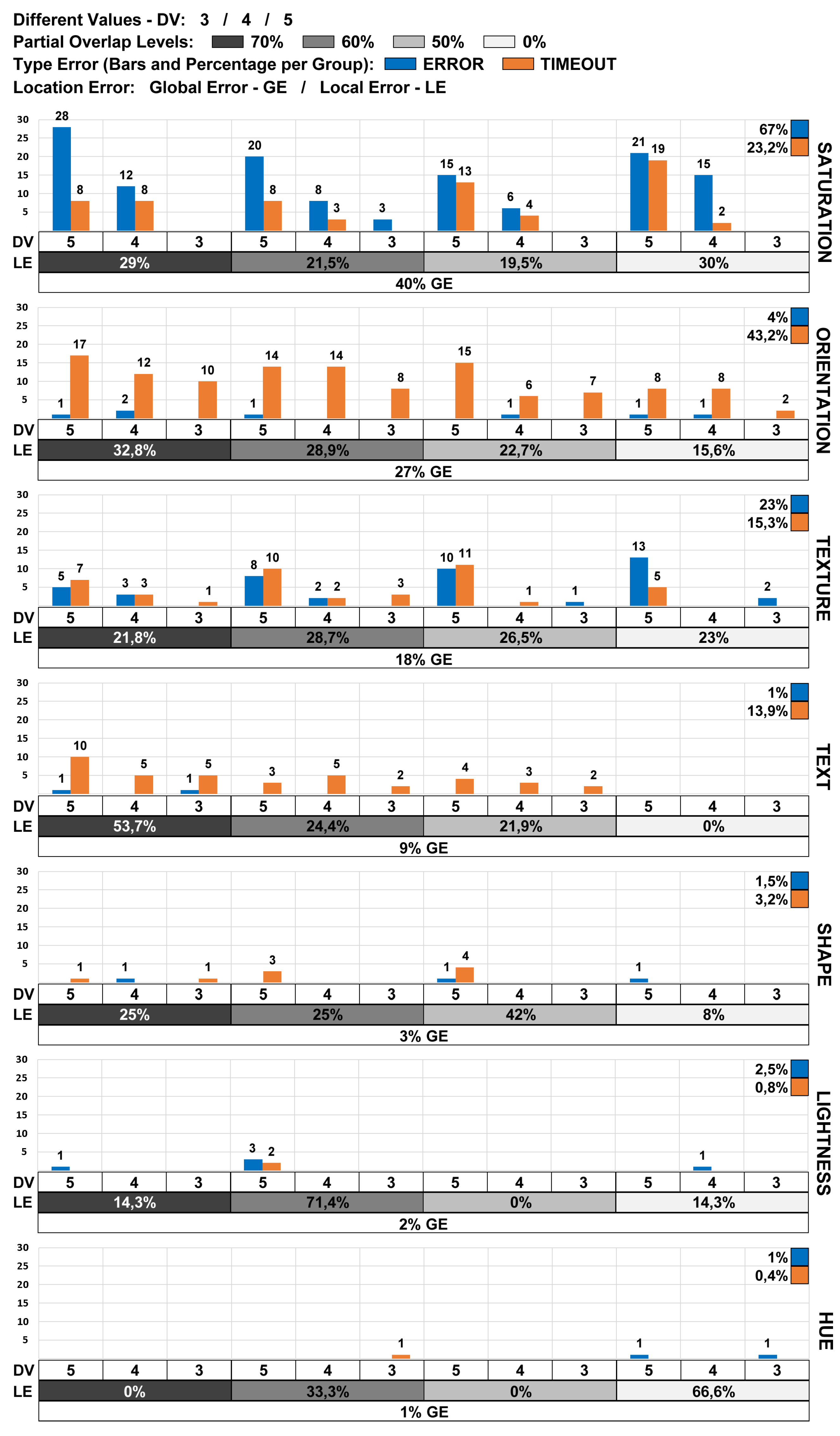

6.6. Orientation

Based on the participants’ comments, the Orientation visual variable presented a high difficulty in identifying visual targets. From the results obtained, the accuracy of the Orientation visual variable got the following values: 81% for 70% partial overlap (POOR classification), 83% for 60% partial overlap, 87% for 50% partial overlap (POOR classification), and 91% without any occlusion (MEDIUM classification).

The Orientation visual variable also received several negative comments and had significant errors (128 errors using the test tool) for all visual coding values. At the end of the analyses, this variable ranked sixth among the studied variables.

The mean time for solving tasks involving this visual variable was considered high, above 10 seconds. All visual values received many negative comments, suggesting that the variable has general identification problems for scenarios with partial overlap.

Finally, it should be noted that the values based on the angles of 45o and 135o showed the lowest number of errors and negative comments from the participants.

6.7. Saturation

Even though the Saturation visual variable demonstrated good robustness in scenarios of three distinct values, it presented heightened levels of difficulty in scenarios for four or five different visual encoding values.

The accuracy of the Saturation visual variable ranged between 74% and 82% (POOR), placing it in seventh and last place in the performance classification of the visual variables studied. It is worth highlighting that the problem with this visual variable occurred at all percentages of partial overlap and resulted in many identification errors (test tool - 193 in total). The Saturation visual variable received many negative comments from the participants (questionnaire - 137 in total).

When considering the gradual increase in the number of different visual encoding values, the Saturation visual variable also demonstrated accuracy issues; this can be seen through the analysis of the results obtained from the control group (without partial overlap), in which the accuracy obtained was only 44% when five different values were mapped; this percentage is considered low for analysis in a scenario without partial overlap.

Figure 1.

The participant followed a sequence of steps in order to complete the evaluation tests.

Figure 1.

The participant followed a sequence of steps in order to complete the evaluation tests.

Figure 2.

Examples of evaluation scenarios used in the tests: (A) Hue visual variable with 70% partial overlap, (B) Orientation visual variable with 60% partial overlap, (C) Texture visual variable with 50% partial overlap, and (D) Shape visual variable with 0% partial overlap.

Figure 2.

Examples of evaluation scenarios used in the tests: (A) Hue visual variable with 70% partial overlap, (B) Orientation visual variable with 60% partial overlap, (C) Texture visual variable with 50% partial overlap, and (D) Shape visual variable with 0% partial overlap.

Figure 3.

The visual variables analyzed in this study are represented by their respective subsets of visual coding values (3, 4, and 5 values).

Figure 3.

The visual variables analyzed in this study are represented by their respective subsets of visual coding values (3, 4, and 5 values).

Figure 4.

Organization of tasks by a group of participants, considering visual variables, the number of distinct visual encodes, and partial overlap level.

Figure 4.

Organization of tasks by a group of participants, considering visual variables, the number of distinct visual encodes, and partial overlap level.

Figure 5.

The hypothesis test procedure for estimating the effect of partial overlap level on the visual perception of each visual variable.

Figure 5.

The hypothesis test procedure for estimating the effect of partial overlap level on the visual perception of each visual variable.

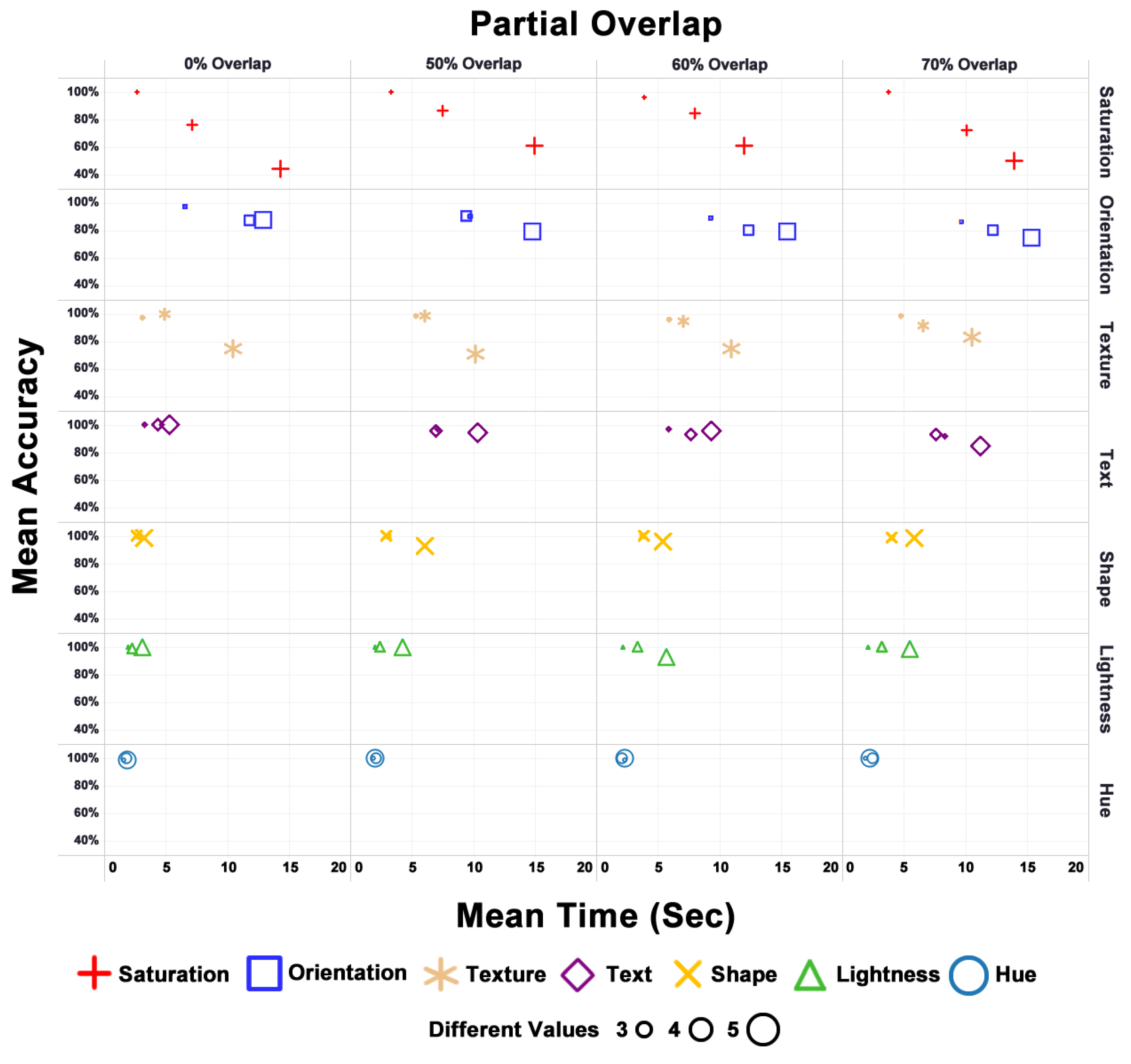

Figure 6.

Resolution time, mean accuracy, and partial overlap for each proposed scenario of visual variables studied, partial overlap levels, and the number of different visual coding values.

Figure 6.

Resolution time, mean accuracy, and partial overlap for each proposed scenario of visual variables studied, partial overlap levels, and the number of different visual coding values.

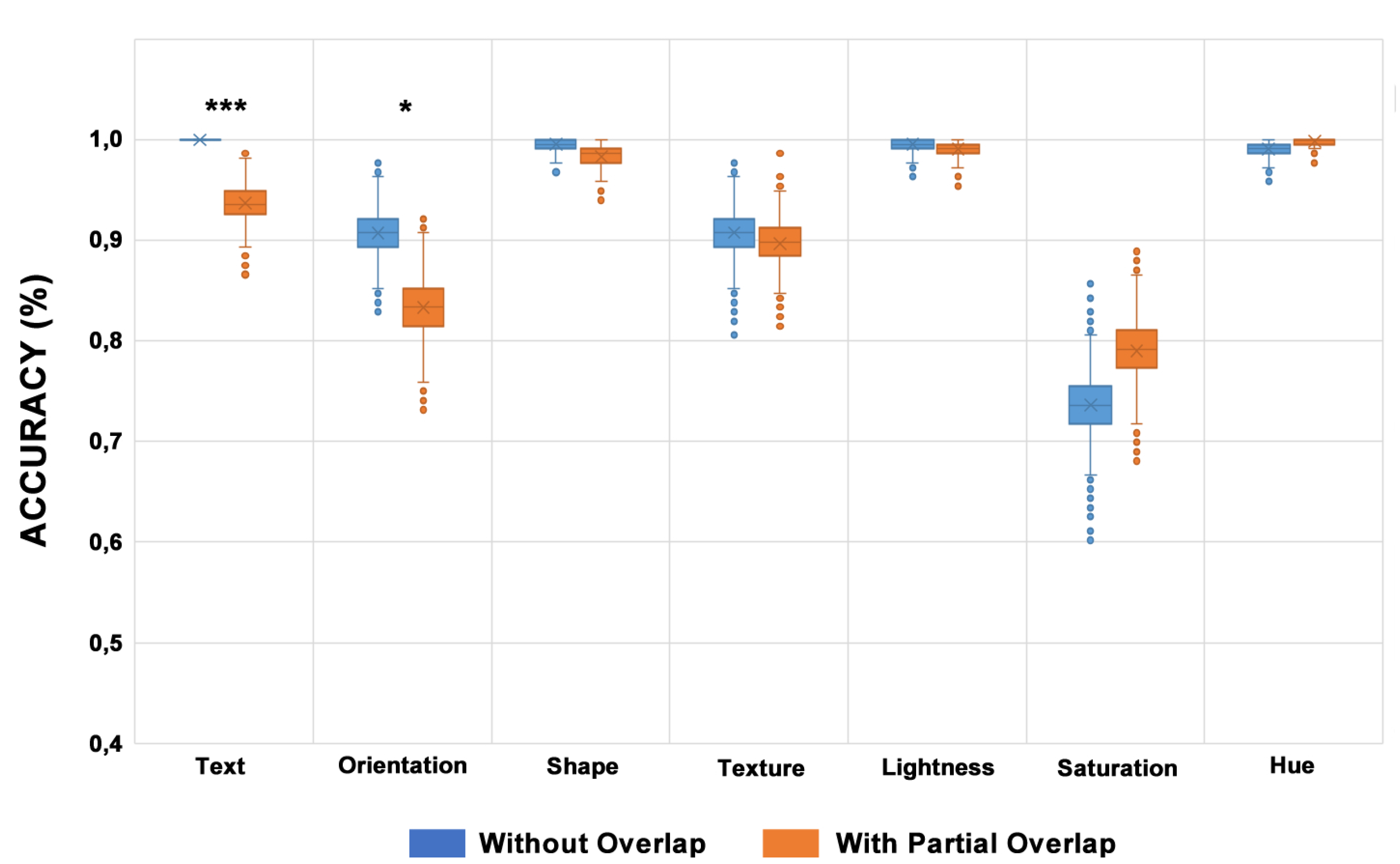

Figure 7.

Bootstrap results with and without partial overlap (n = 216). Text (p < 0.001 ***) and Orientation (p < 0.05 *) visual variables showed a difference in significance at alpha = 0.05 due to partial overlap.

Figure 7.

Bootstrap results with and without partial overlap (n = 216). Text (p < 0.001 ***) and Orientation (p < 0.05 *) visual variables showed a difference in significance at alpha = 0.05 due to partial overlap.

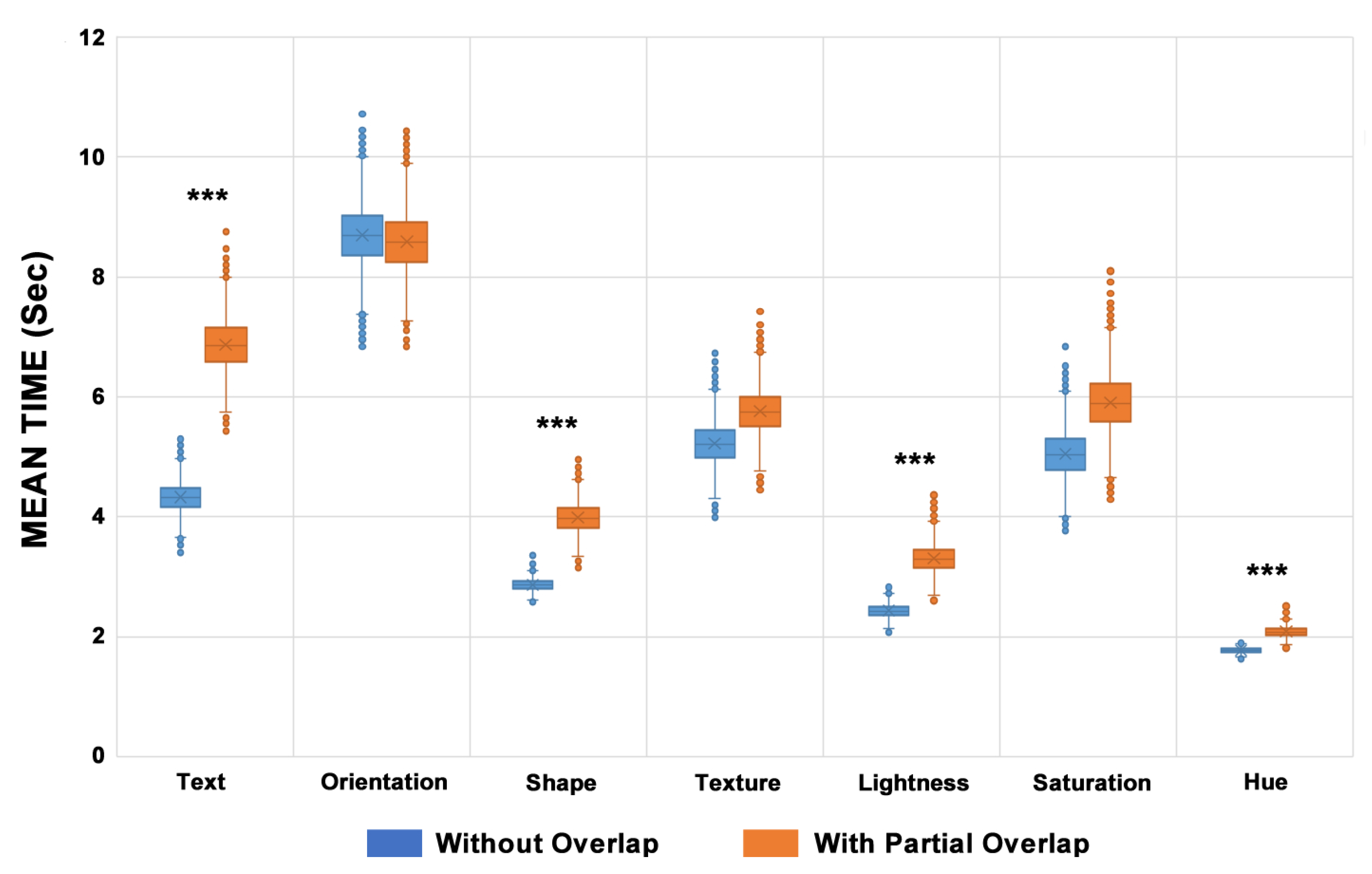

Figure 8.

The mean time of bootstrap results with and without partial overlap (n = 216). Text, Shape, Lightness, and Hue visual variables showed a statistically significant difference because of the use of partial overlap (p < 0.001 ***), alpha = 0.05

Figure 8.

The mean time of bootstrap results with and without partial overlap (n = 216). Text, Shape, Lightness, and Hue visual variables showed a statistically significant difference because of the use of partial overlap (p < 0.001 ***), alpha = 0.05

Figure 9.

Analysis based on the number of ERRORS and TIMEOUTS for each visual variable. The Saturation visual variable showed 40% of all errors registered considering all proposed scenarios.

Figure 9.

Analysis based on the number of ERRORS and TIMEOUTS for each visual variable. The Saturation visual variable showed 40% of all errors registered considering all proposed scenarios.

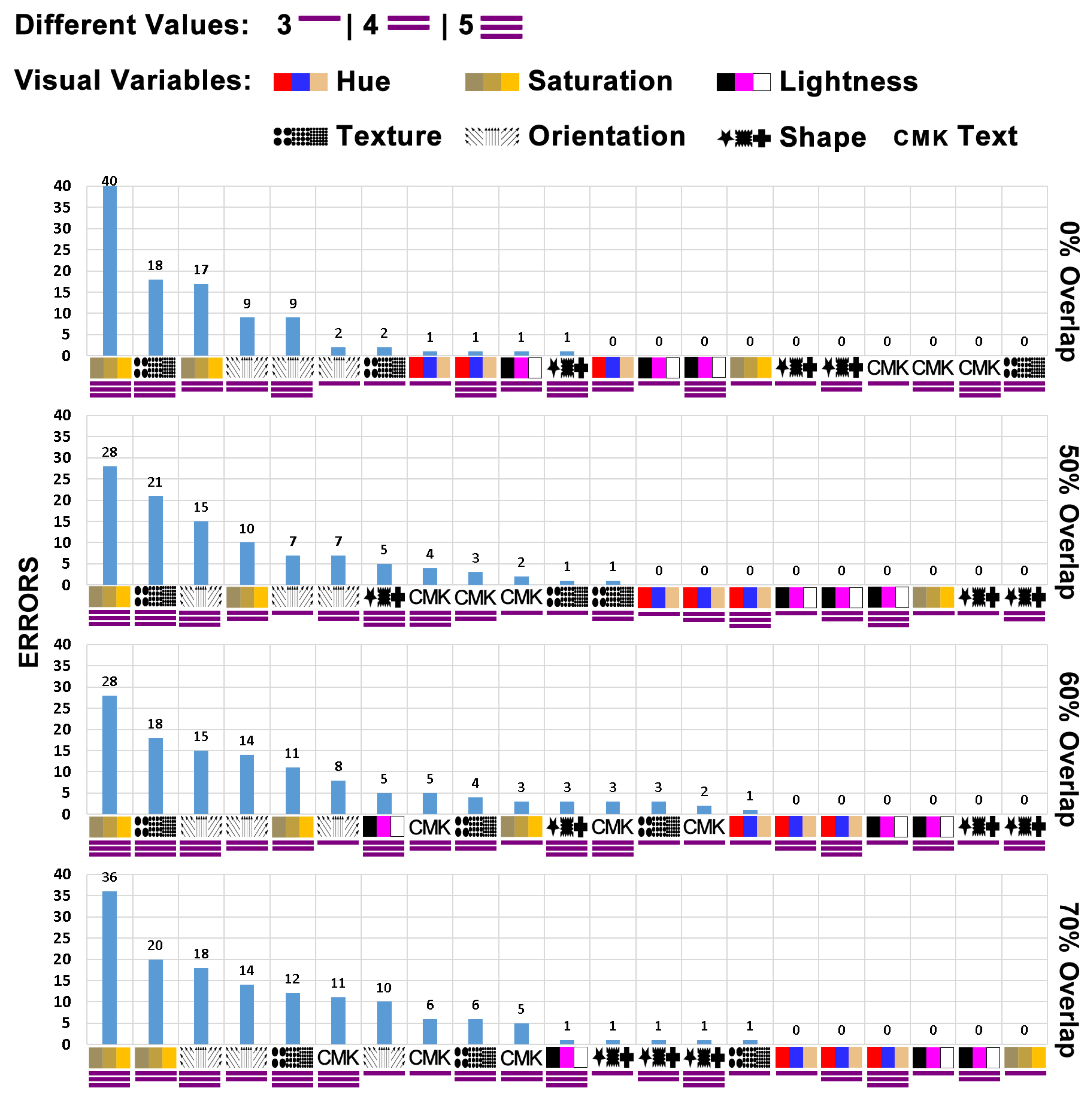

Figure 10.

Total number of errors (ERRORS+TIMEOUT) for each evaluation scenario (Visual Variable + Overlapping Level + Subset of Different Visual Coding Values).

Figure 10.

Total number of errors (ERRORS+TIMEOUT) for each evaluation scenario (Visual Variable + Overlapping Level + Subset of Different Visual Coding Values).

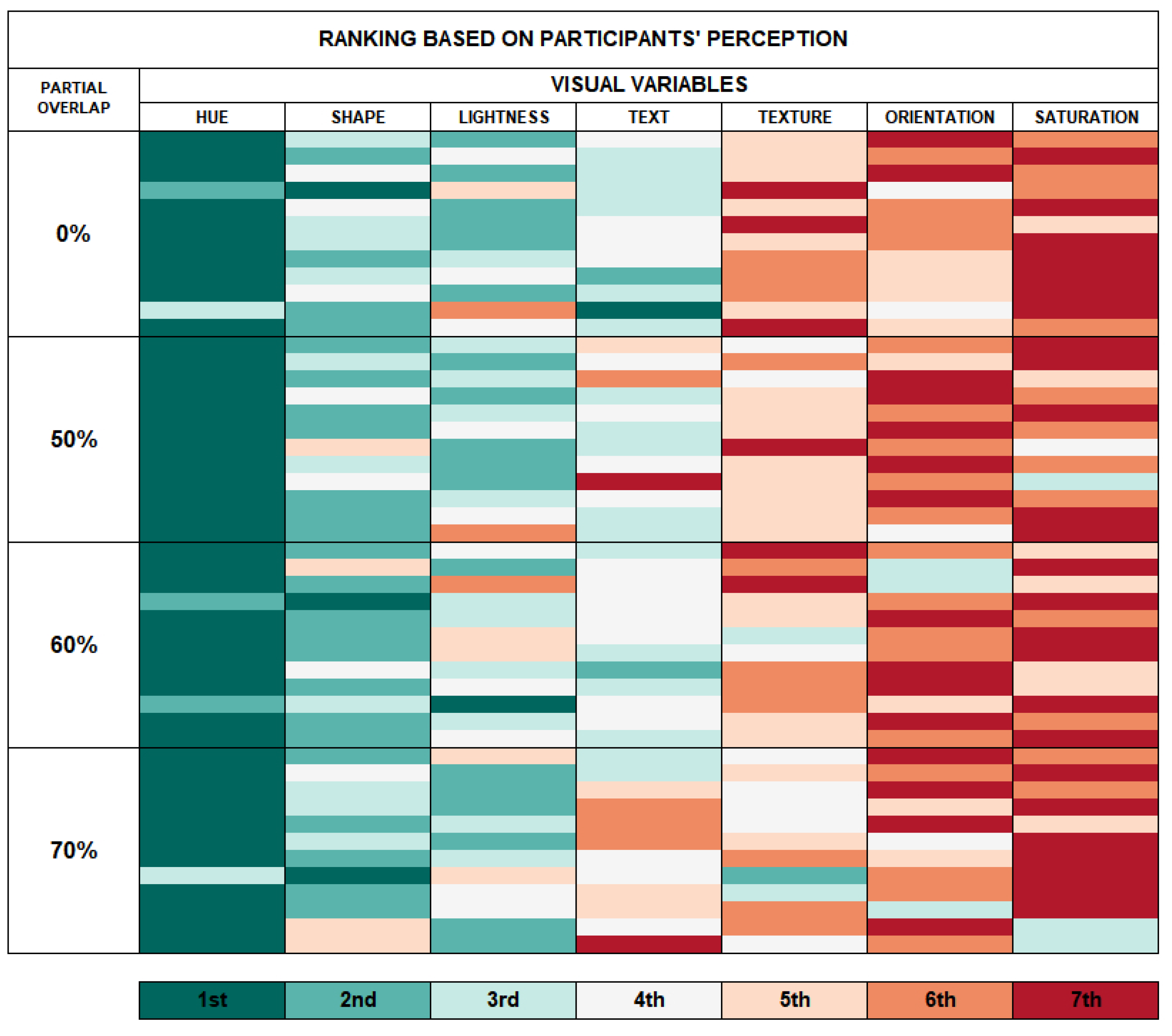

Figure 11.

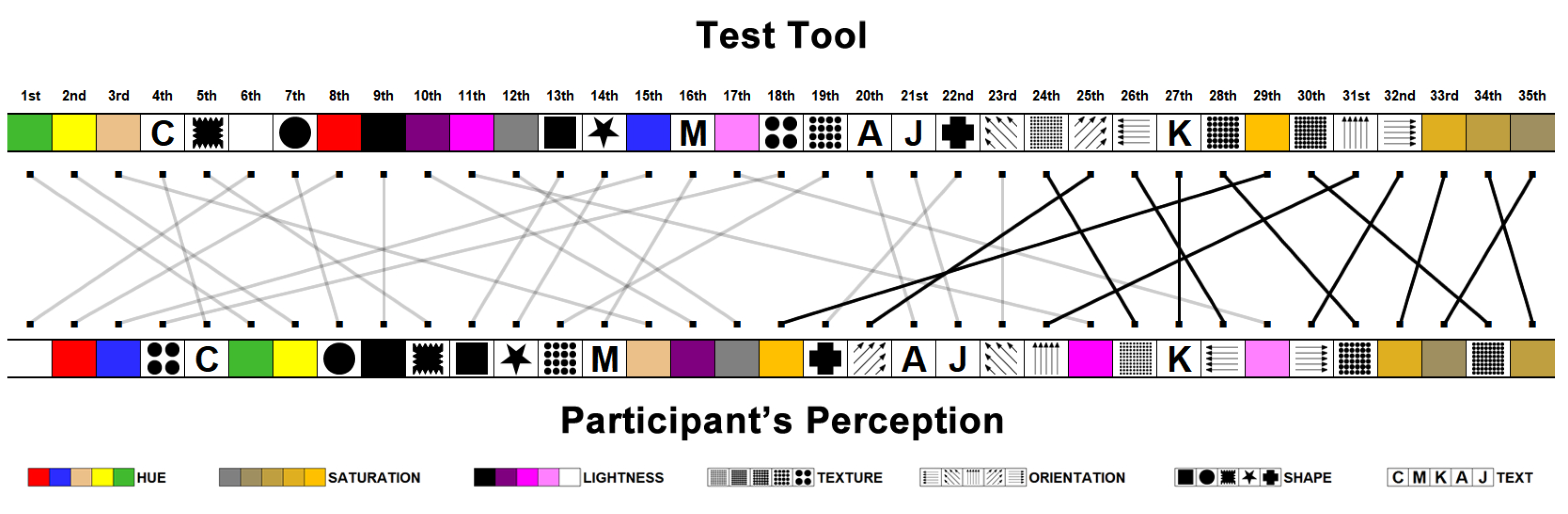

The ranking of visual variables to identify the target item more ease.

Figure 11.

The ranking of visual variables to identify the target item more ease.

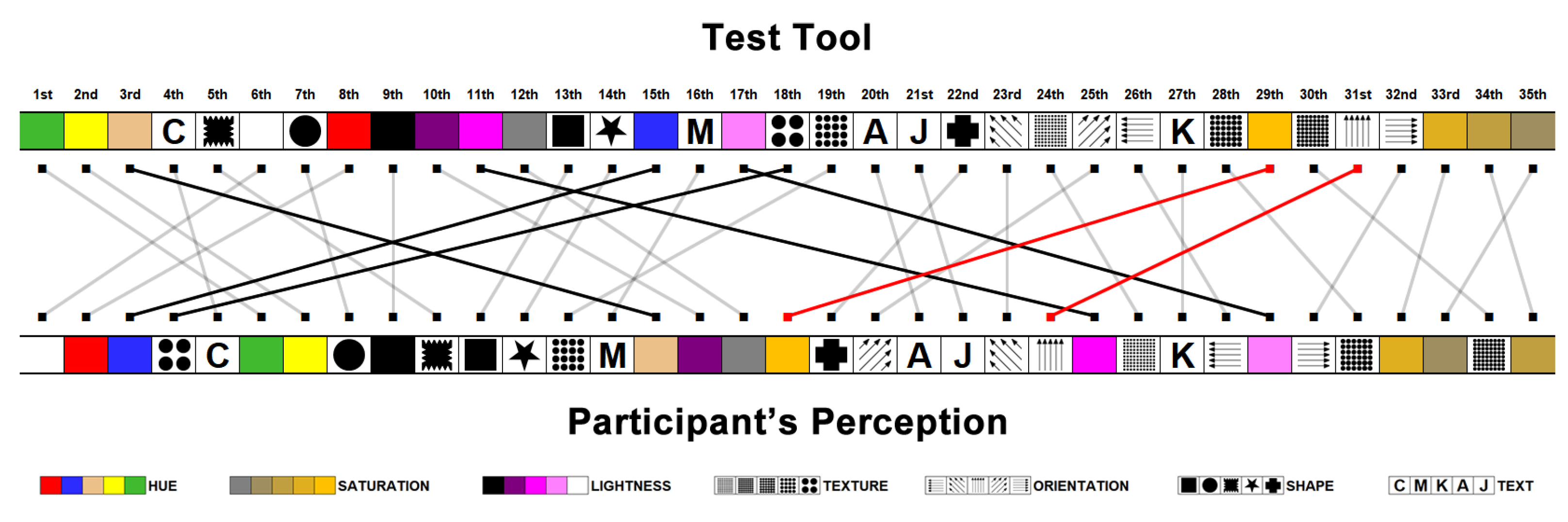

Figure 12.

Visual encoded items with the most significant position difference in both rankings. Highlight the elements in the 29th (Saturation) and 31st (Orientation) positions.

Figure 12.

Visual encoded items with the most significant position difference in both rankings. Highlight the elements in the 29th (Saturation) and 31st (Orientation) positions.

Figure 13.

The visual coding values with the highest number of errors got by the test tool compared with the number of identification difficulty perceptions registered by the participants.

Figure 13.

The visual coding values with the highest number of errors got by the test tool compared with the number of identification difficulty perceptions registered by the participants.

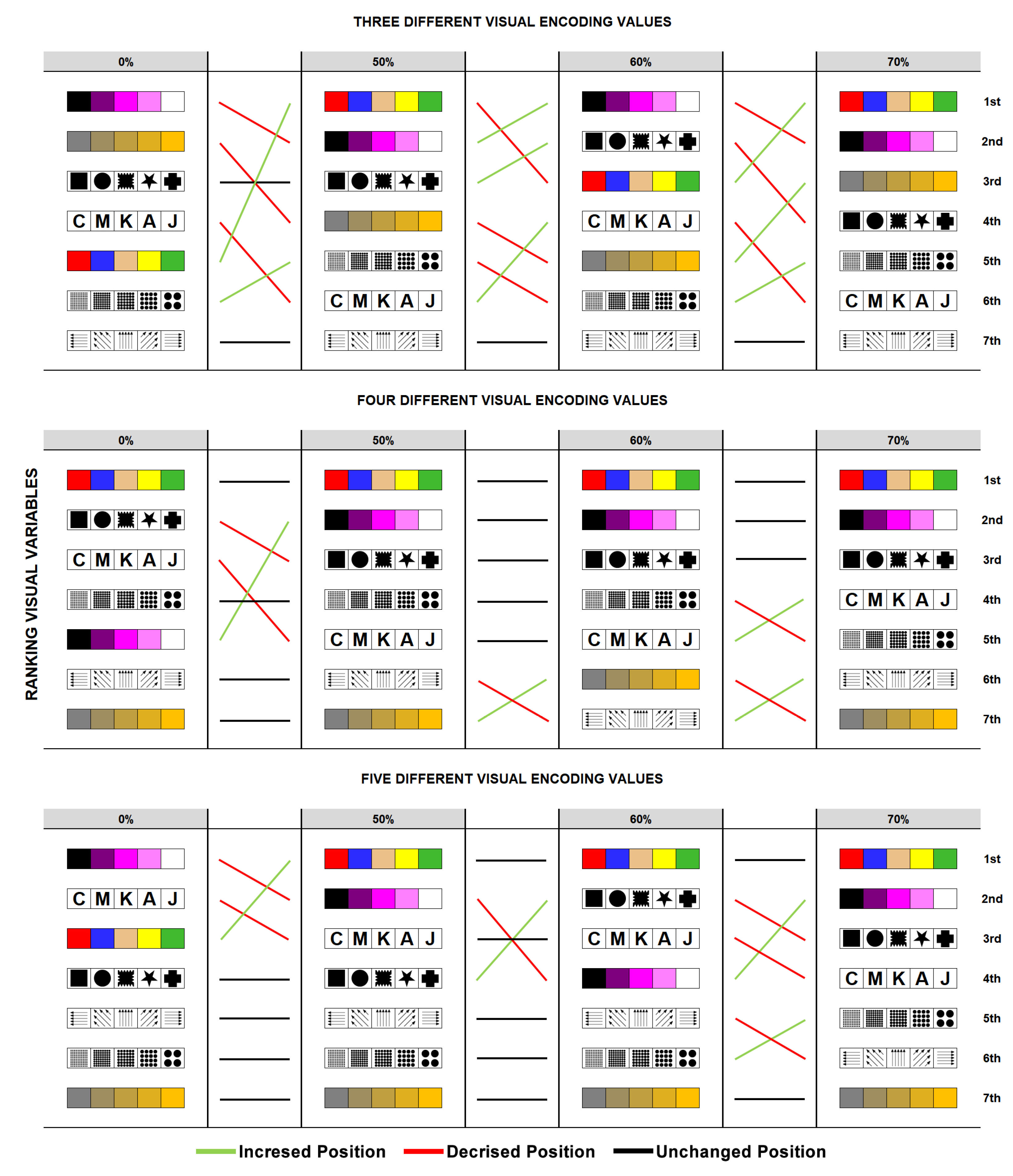

Figure 14.

Ranking of the visual variables for different percentages of partial overlap and different quantities of visual coding values.

Figure 14.

Ranking of the visual variables for different percentages of partial overlap and different quantities of visual coding values.