Submitted:

21 June 2023

Posted:

21 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Generative Adversarial Networks

2.2. On Meteorological Fields

2.3. Training Datasets

Seasonal Temperature Forecasts (ECMWF): Coarse-resolution Images

ERA5-Land Reanalysis Temperature Data: High-resolution Images

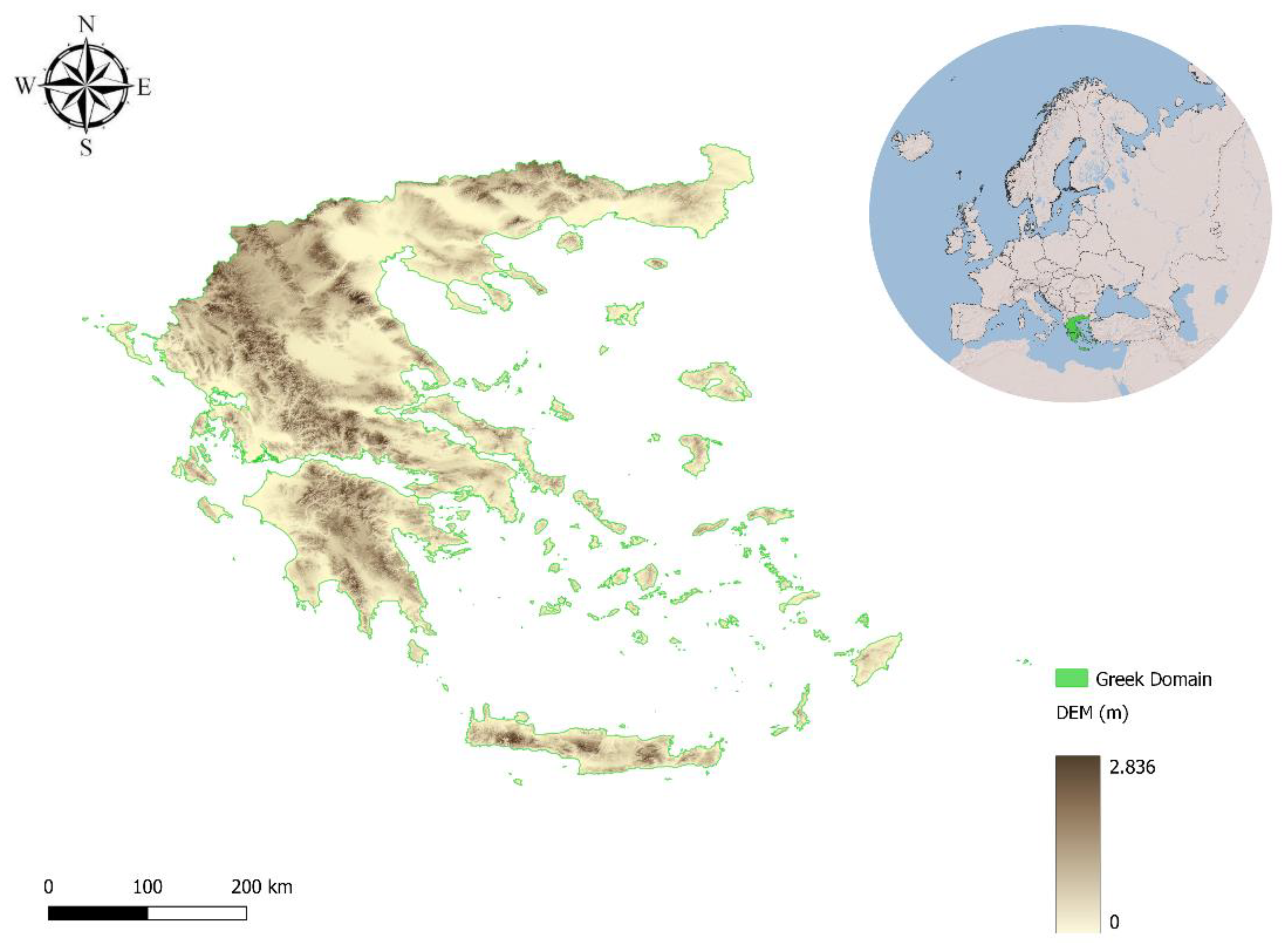

Digital Elevation Model (EU-DEM): Predictor

CORINE Land Cover: Predictor

SOILGRIDS Soil Type: Predictor

2.4. Network

2.4.1. Data Pre-processing and Training

| Dimensions | |

|---|---|

| Target resolution | time: 5124, lon: 112, lat: 112 |

| Coarse resolution | time: 5124, lon: 56, lat: 56 |

2.4.2. Model Architecture—Metrics

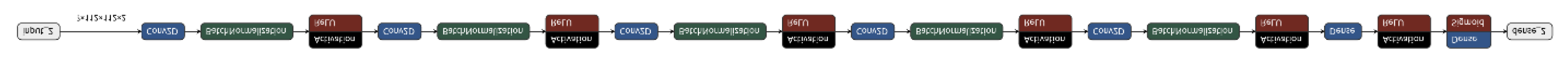

- The generator consists of downsampling and upsampling layers to produce high resolution images from low resolution images. It starts with a Dense layer that takes the low resolution image as input, then downsamples it by using two Conv2D layers, then upsamples it by using Conv2DTranspose layers until the desired image dimensions are reached. LeakyRelu was used as an activation function for all layers except for the last output layer which uses tanh.

- The discriminator consists of 5 Conv2D layers and one Dense layer. In each layer Relu is used as the activation function. Additional dropout layers were inserted after each Conv2D layer for preventing overfitting. The output layer uses sigmoid for the activation.

3. Results

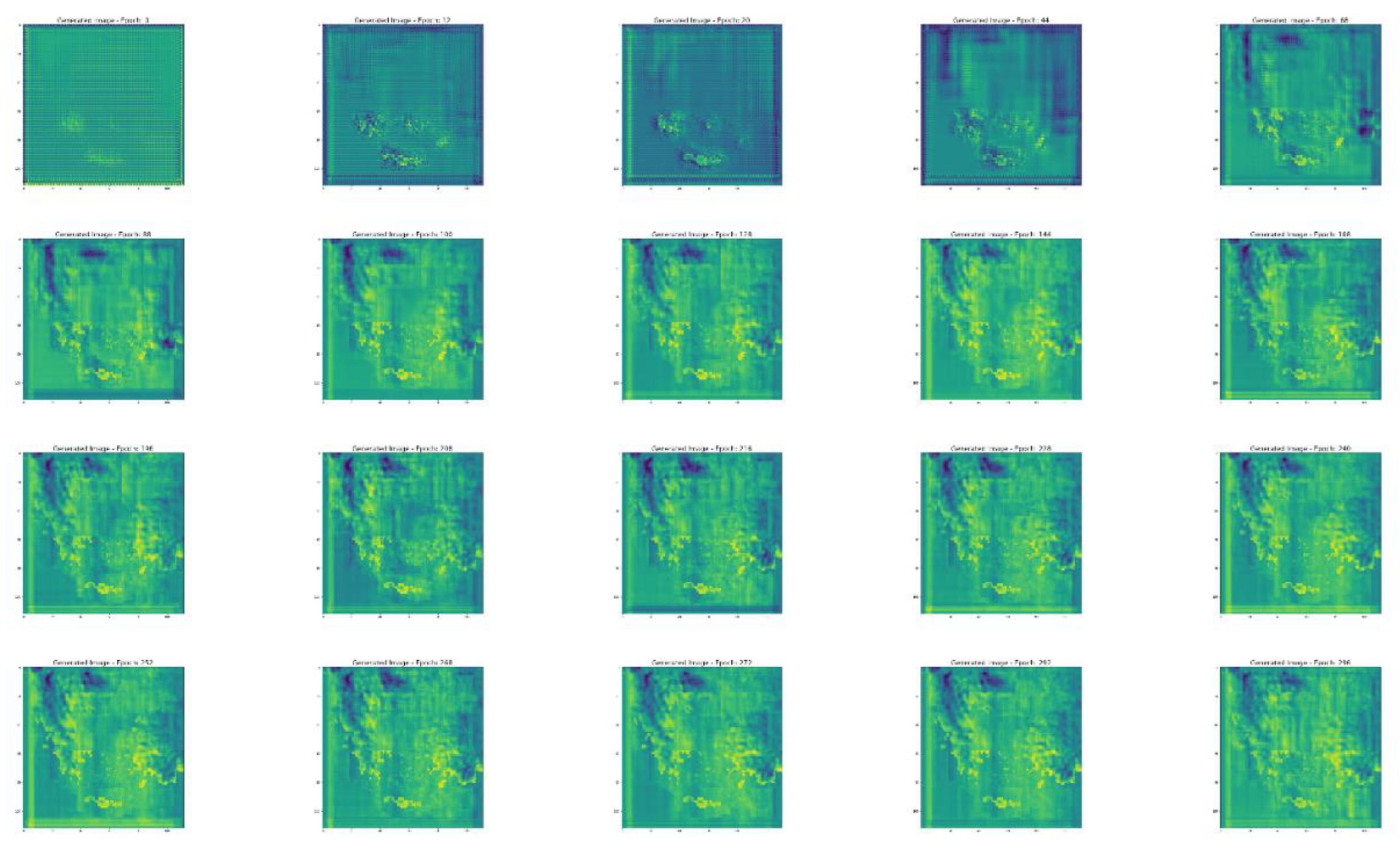

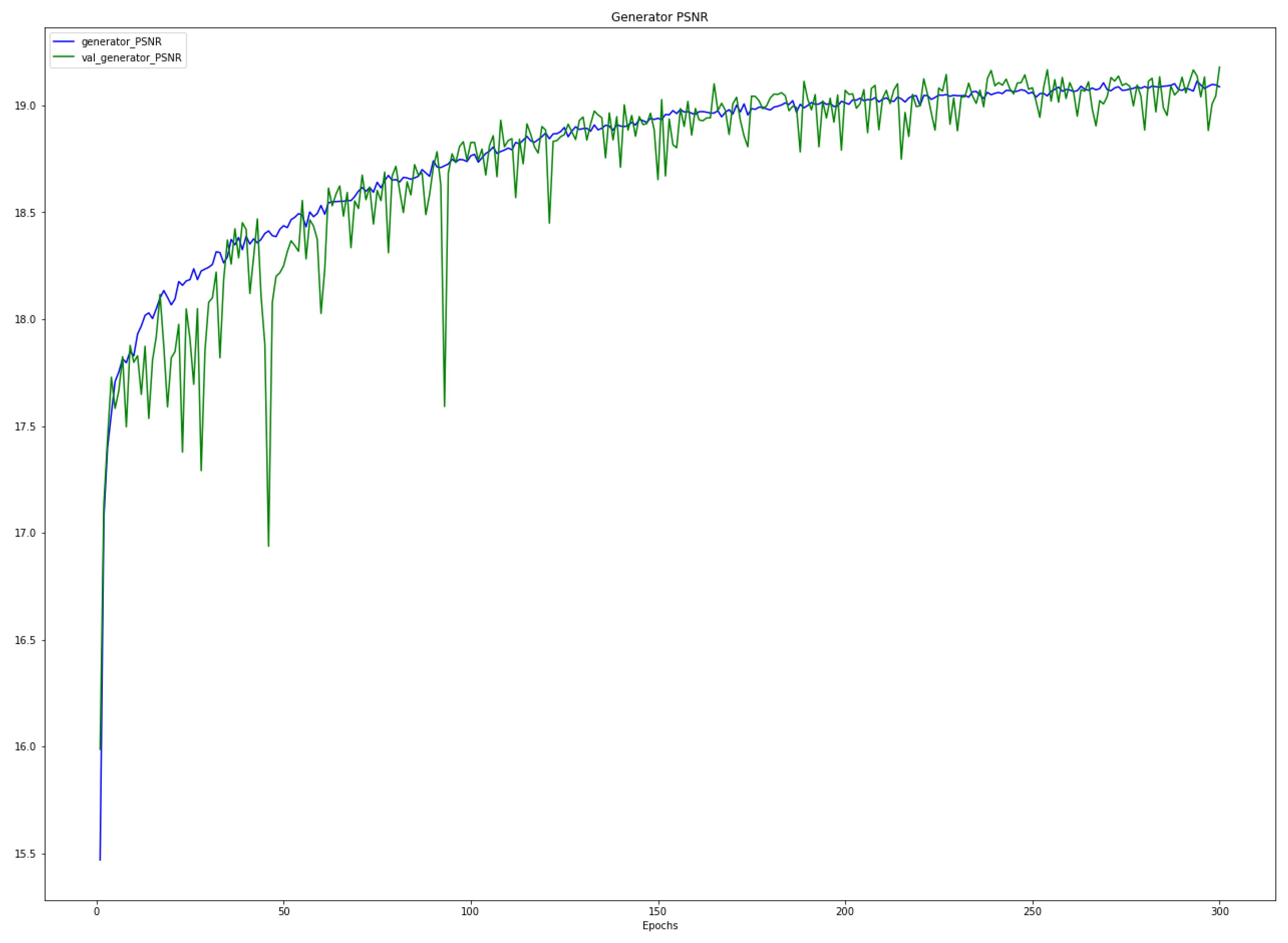

3.1. Training

3.2. Model Predictions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vitart, F., Robertson, A. W., Spring, A., Pinault, F., Roškar, R., Cao, W., ... & Zhou, S. Outcomes of the WMO Prize Challenge to Improve Subseasonal to Seasonal Predictions Using Artificial Intelligence. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2022, 103(12), E2878–E2886.

- Robertson, A. W. , Vitart, F., & Camargo, S. J. (2020). Subseasonal to seasonal prediction of weather to climate with application to tropical cyclones. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 125(6), e2018JD029375.

- Mariotti, A. Mariotti, A., Baggett, C., Barnes, E. A., Becker, E., Butler, A., Collins, D. C., ... & Albers, J. Windows of opportunity for skillful forecasts subseasonal to seasonal and beyond. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2020, 101(5), E608–E625. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y. , Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Li, L. (2019). Geographically weighted machine learning and downscaling for high-resolution spatiotemporal estimations of wind speed. Remote Sensing, 11(11), 1378.

- Höhlein, K., Kern, M., Hewson, T., & Westermann, R. A comparative study of convolutional neural network models for wind field downscaling. Meteorological Applications 2020, 27(6), e1961.

- Sekiyama, T. T. (2020). Statistical downscaling of temperature distributions from the synoptic scale to the mesoscale using deep convolutional neural networks. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2007.10839.

- Leinonen, J. , Nerini, D., & Berne, A. (2020). Stochastic super-resolution for downscaling time-evolving atmospheric fields with a generative adversarial network. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 59(9), 7211-7223.

- Singh, A. , White, B., Albert, A., & Kashinath, K. (2020, January). Downscaling numerical weather models with GANs. In 100th American Meteorological Society Annual Meeting. AMS.

- Harris, L., McRae, A. T., Chantry, M., Dueben, P. D., & Palmer, T. N. A generative deep learning approach to stochastic downscaling of precipitation forecasts. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 2022, 14(10), e2022MS003120.

- Scheiter, M., Valentine, A., & Sambridge, M. Upscaling and downscaling Monte Carlo ensembles with generative models. Geophysical Journal International 2022, 230(2), 916–931.

- Goodfellow, I. , Pouget-Abadie, J., Mirza, M., Xu, B., Warde-Farley, D., Ozair, S., Courville, A. & Bengio, Y., 2014. Generative adversarial nets, in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 27, Curran Associates, Inc.

- Radford, A. , Metz, L. & Chintala, S., 2015. Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks, preprint (arXiv:1511.06434).

- Arjovsky, M., Chintala, S. & Bottou, L., 2017. Wasserstein generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning; PMLR; 70, pp. 214–223.

- Miralles, O., Steinfield, D., Martius, O., & Davison, A. C. (2022). Downscaling of Historical Wind Fields over Switzerland using Generative Adversarial Networks. Artificial Intelligence for the Earth Systems, 1-44.

- Winstral, A., T. Jonas, and N. Helbig, 2017: Statistical downscaling of gridded wind speed data using local topography. Journal of Hydrometeorology, 18 (2), 335–348.

- Nerini, D. , 2020: Probabilistic deep learning for postprocessing wind forecasts in complex terrain.

- Goodfellow, I., Y. Bengio, and A. Courville, 2016: Deep learning. MIT press.

- Vandal, T., E. Kodra, S. Ganguly, A. Michaelis, R. Nemani, and A. R. Ganguly, 2018: Generating high resolution climate change projections through single image super-resolution: An abridged version. Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 5389–5393. 5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M., G. Camps-Valls, B. Stevens, M. Jung, J. Denzler, N. Carvalhais, and Prabhat, 2019: Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature, 566 (7743), 195–204. 7743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baño Medina, J., R. Manzanas, and J. M. Gutiérrez, 2020: Configuration and intercomparison of deep learning neural models for statistical downscaling. Geoscientific Model Development, 13 (4), 2109–2124. 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y., D. J. G. Ii, G. West, and R. Stull, 2020: Deep-Learning-Based Gridded Downscaling of Surface Meteorological Variables in Complex Terrain. Part I: Daily Maximum and Minimum 2-m Temperature. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 59 (12), 2057–2073. [CrossRef]

- Höhlein, K., M. Kern, T. Hewson, and R. Westermann, 2020: A comparative study of convolutional neural network models for wind field downscaling. Meteorological Applications, 27 (6), e1961.

- Seasonal Forecasts Data Page on Climate Data Store. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/seasonal-original-single-levels?tab=overview (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Schulzweida, Uwe. (2022). CDO User Guide (2.1.0). Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- ERA5-Land Data Page on Climate Data Store. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-land?tab=overview (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- EU-DEM Data Page. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/imagery-in-situ/eu-dem/eu-dem-v1.1 (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- CORINE Land Cover Data Page. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/pan-european/corine-land-cover (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Poggio, L. , de Sousa, L. M., Batjes, N. H., Heuvelink, G. B. M., Kempen, B., Ribeiro, E., and Rossiter, D.: SoilGrids 2.0: producing soil information for the globe with quantified spatial uncertainty, SOIL, 7, 217–240, 2021. https://soil.copernicus.org/articles/7/217/2021/.

- Saha, A. , & Ravela, S. (2022). Downscaling Extreme Rainfall Using Physical-Statistical Generative Adversarial Learning. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2212.01446.

- Price, I. , & Rasp, S. (2022, May). Increasing the accuracy and resolution of precipitation forecasts using deep generative models. In International conference on artificial intelligence and statistics (pp. 10555-10571). PMLR.

- Annau, N. J. , Cannon, A. J., & Monahan, A. H. (2023). Algorithmic Hallucinations of Near-Surface Winds: Statistical Downscaling with Generative Adversarial Networks to Convection-Permitting Scales. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2302.08720.

- Accarino, G., Chiarelli, M., Immorlano, F., Aloisi, V., Gatto, A., & Aloisio, G. (2021). MSG-GAN-SD: A Multi-Scale Gradients GAN for Statistical Downscaling of 2-Meter Temperature over the EURO-CORDEX Domain. AI 2021, 2, 600–620.

- Gong, B. , Ji, Y., Langguth, M., and Schultz, M. Statistical downscaling of precipitation with deep neural networks, EGU General Assembly 2023, Vienna, Austria, 24–28 Apr 2023, EGU23-10488. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).