Submitted:

20 June 2023

Posted:

21 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

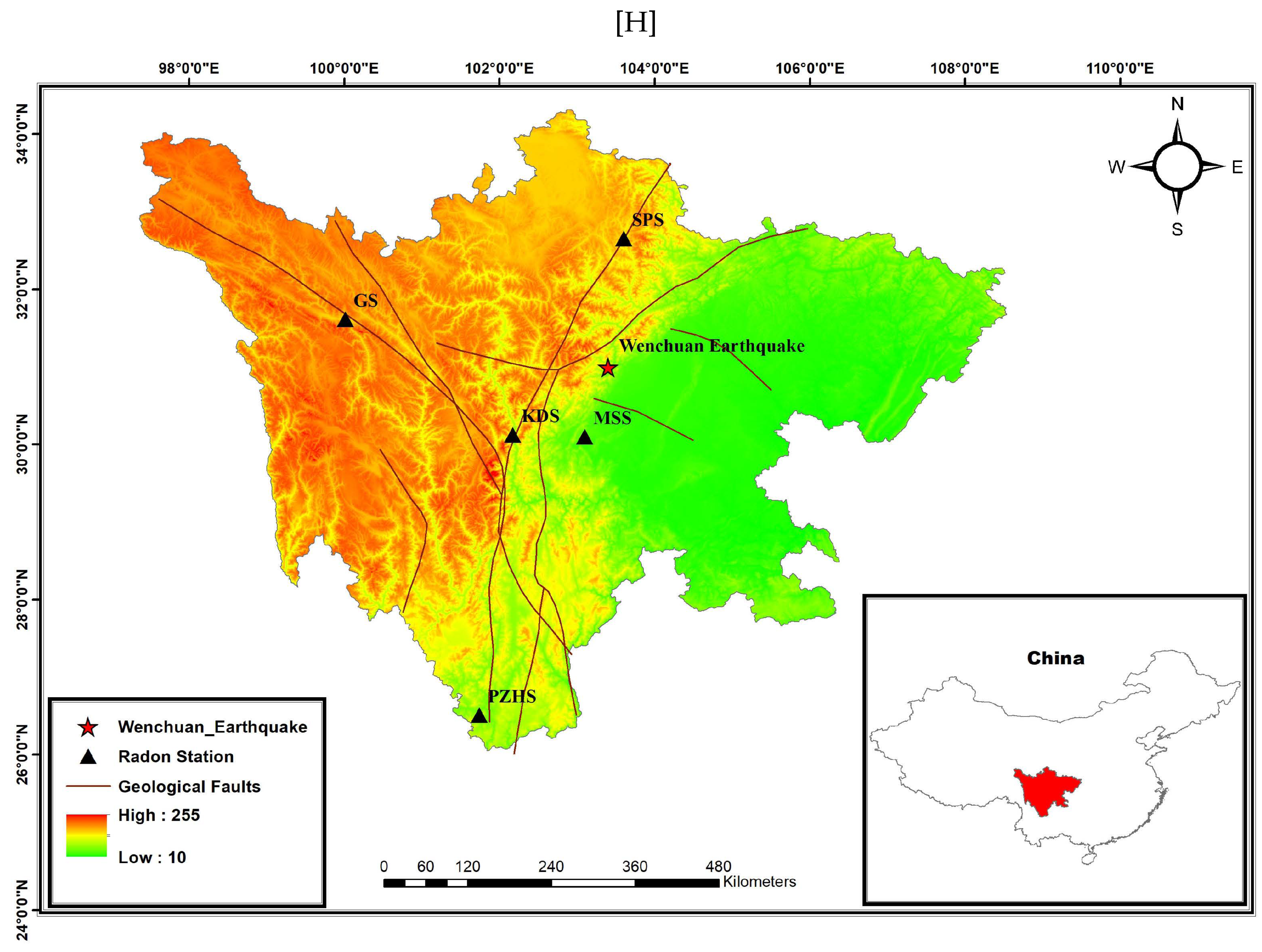

2.1. Experimental aspects

2.1.1. Earthquake activity

2.2. Measurement setup

3. Mathematical Aspects

3.1. Fractal and long-memory

3.2. Hurst exponent

- (i)

- If , the series has a positive long-range autocorrelation. A series’ high value is followed by a series’ high value, and vice versa. High Hurst exponents suggest persistent interactions that are predicted to occur in the series’ far future;

- (ii)

- If , low values follow high values in the time series, and vice versa. There is an ongoing exchange between low and high values for low H values in the time series’ future (this is known as anti-persistency);

- (iii)

- If associated processes are random and the time series are totally uncorrelated..

3.3. Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (DFA)

3.3.1. Application of DFA

- (i)

-

The time series is, first, integrated:The entire average value of the time series is denoted in Equation (1) by the symbols the symbol <...> and k stands for the various time scales.

- (ii)

- The integrated time series, , is then separated into equal, non-overlapping bins of length, n.

- (iii)

- The function that represents the trend in the box is then fitted. Simple linear trends or polynomials of order 2 or higher order may be used. Here, the linear function was used. This linear function’s y coordinate is denoted by the notation in each box n.

- (iv)

- The local linear trend, , is then subtracted from the integrated time series , which is detrended in each box of length n. The detrended time series, , is determined in this manner and for each bin as follows:

- (v)

- The integrated and detrended time series’ fluctuations’ root-mean-square (rms) is then computed for each bin of size n aswhere, are the rms fluctuations of the detrended time series .

- (vi)

-

For various sizes of the scale boxes, the method steps (i)–(v) are repeated. This reveals the specific sort of connection between and n. If there are long-term relationships in the time series, then and n have an exponential relationship.The scaling exponent (DFA exponent) in Equation (4) assesses the strength of the time series’ long-term relationships.

- (vii)

- The linear relationship between and , whose slope equals , is found by applying a logarithmic transformation to Equation (4). A strong linear connection suggests that the accompanying variations are long-lasting and, consequently, have a long memory. The square of the Spearman’s () is used in this paper to measure the accuracy of the linear fit. Good linear fits were defined as having 0.95 or above [1,15,29,47,76].

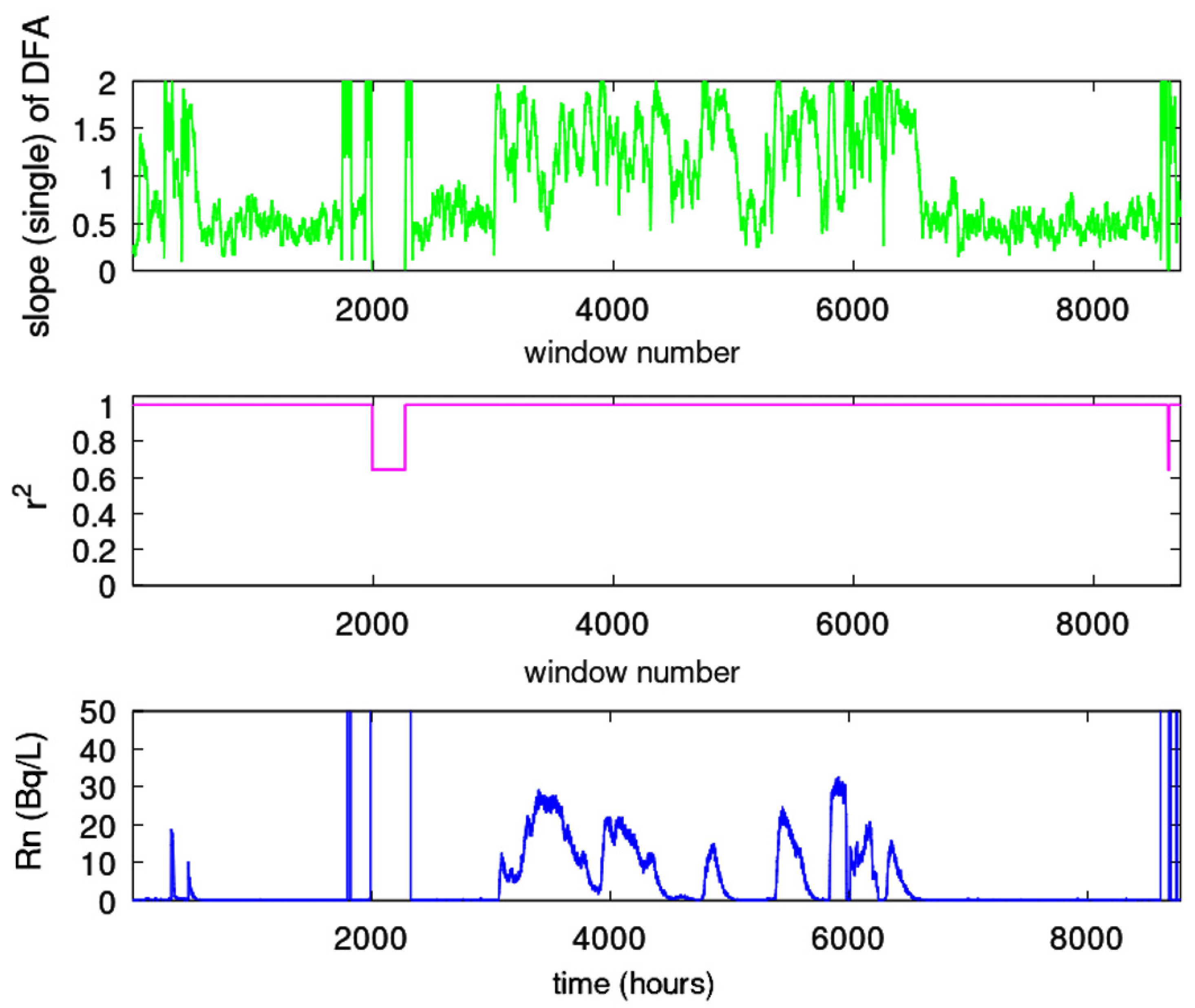

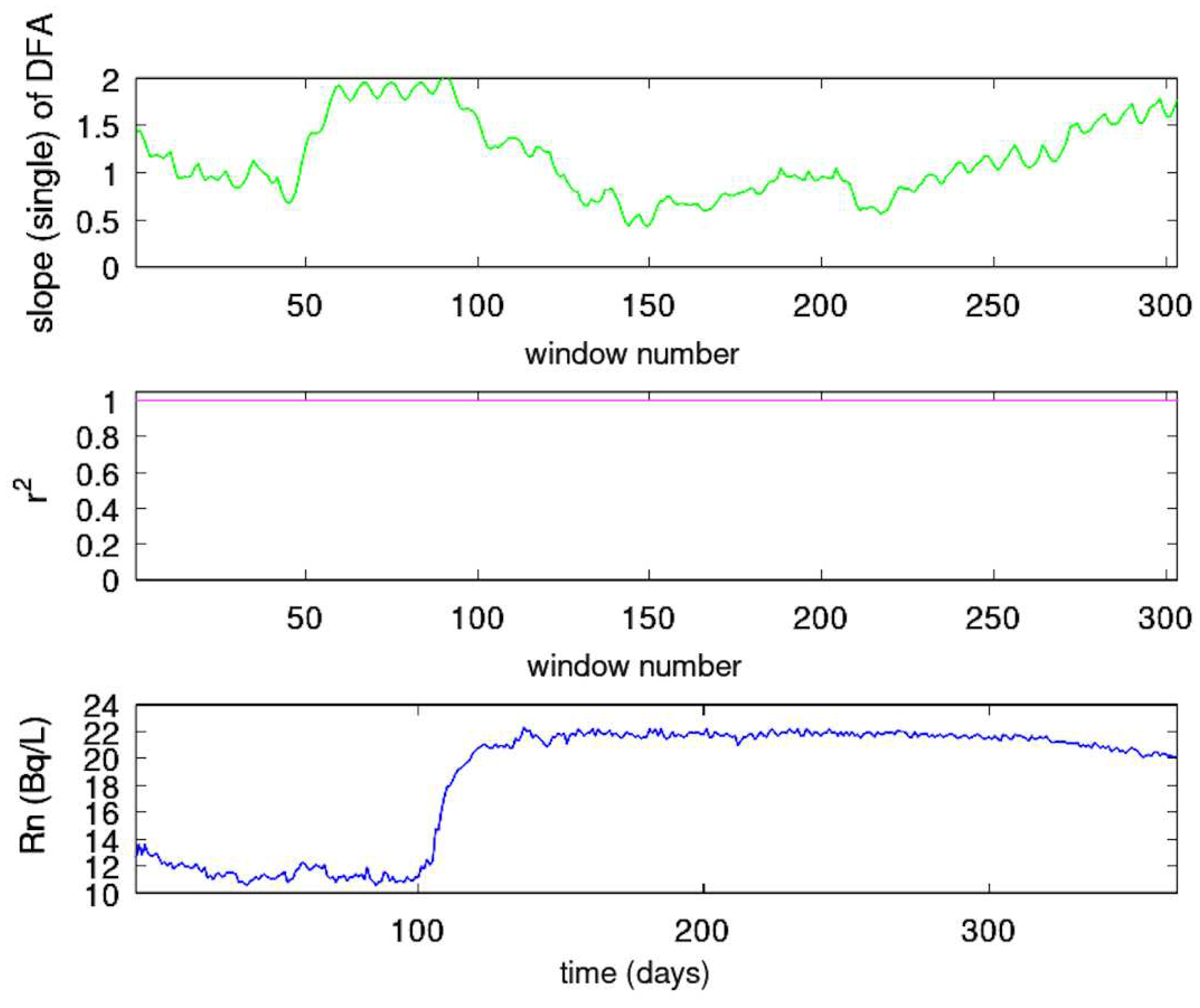

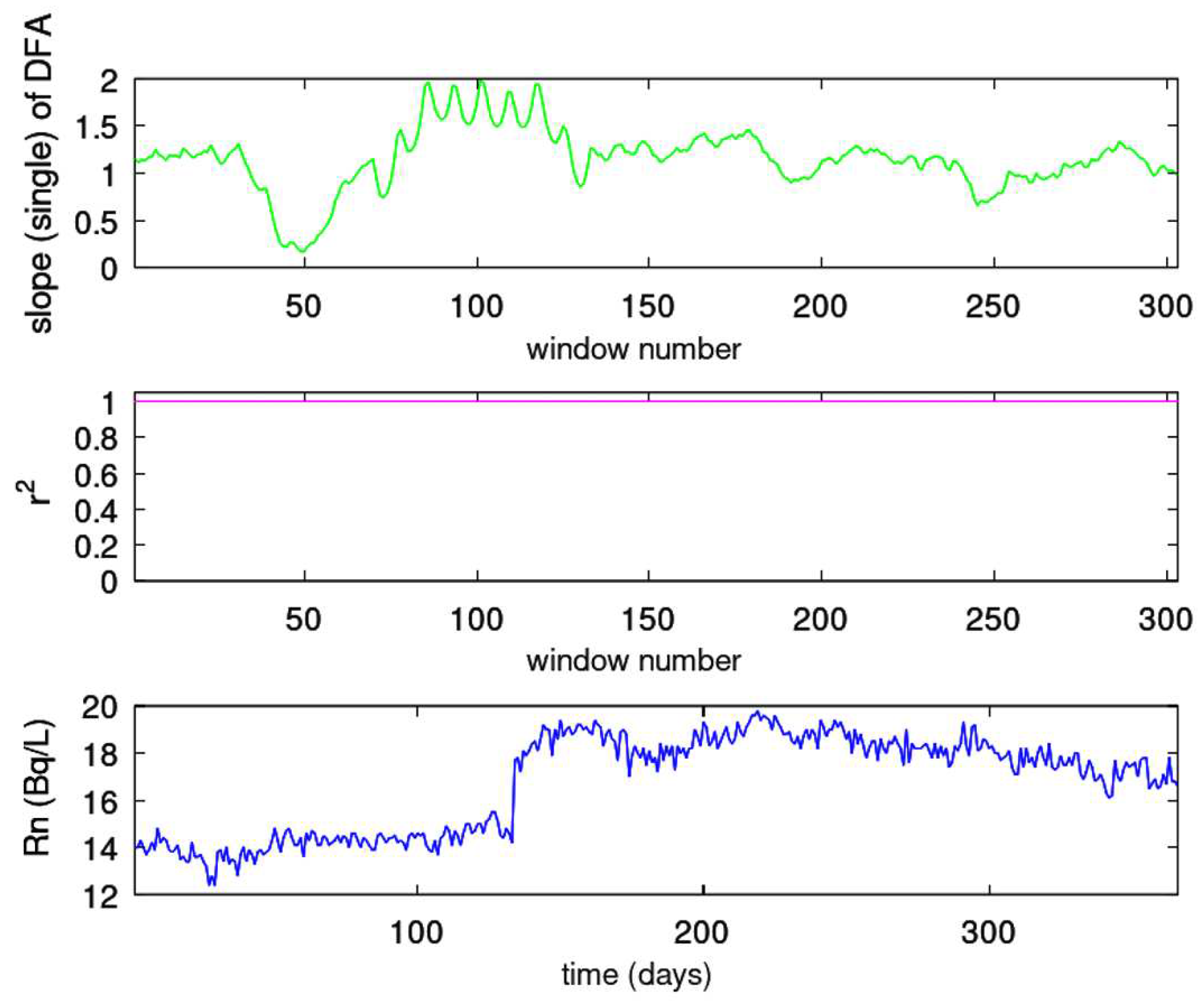

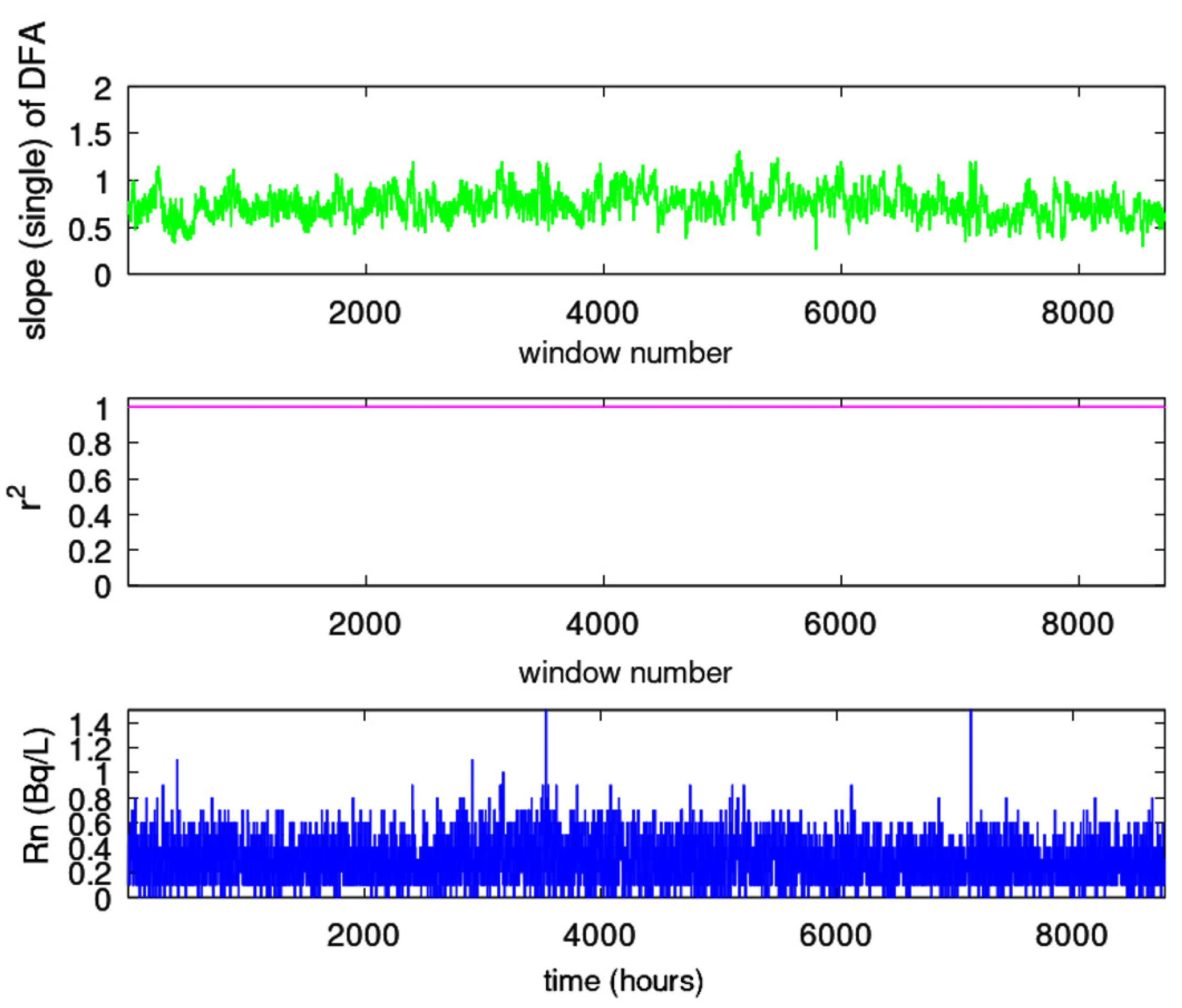

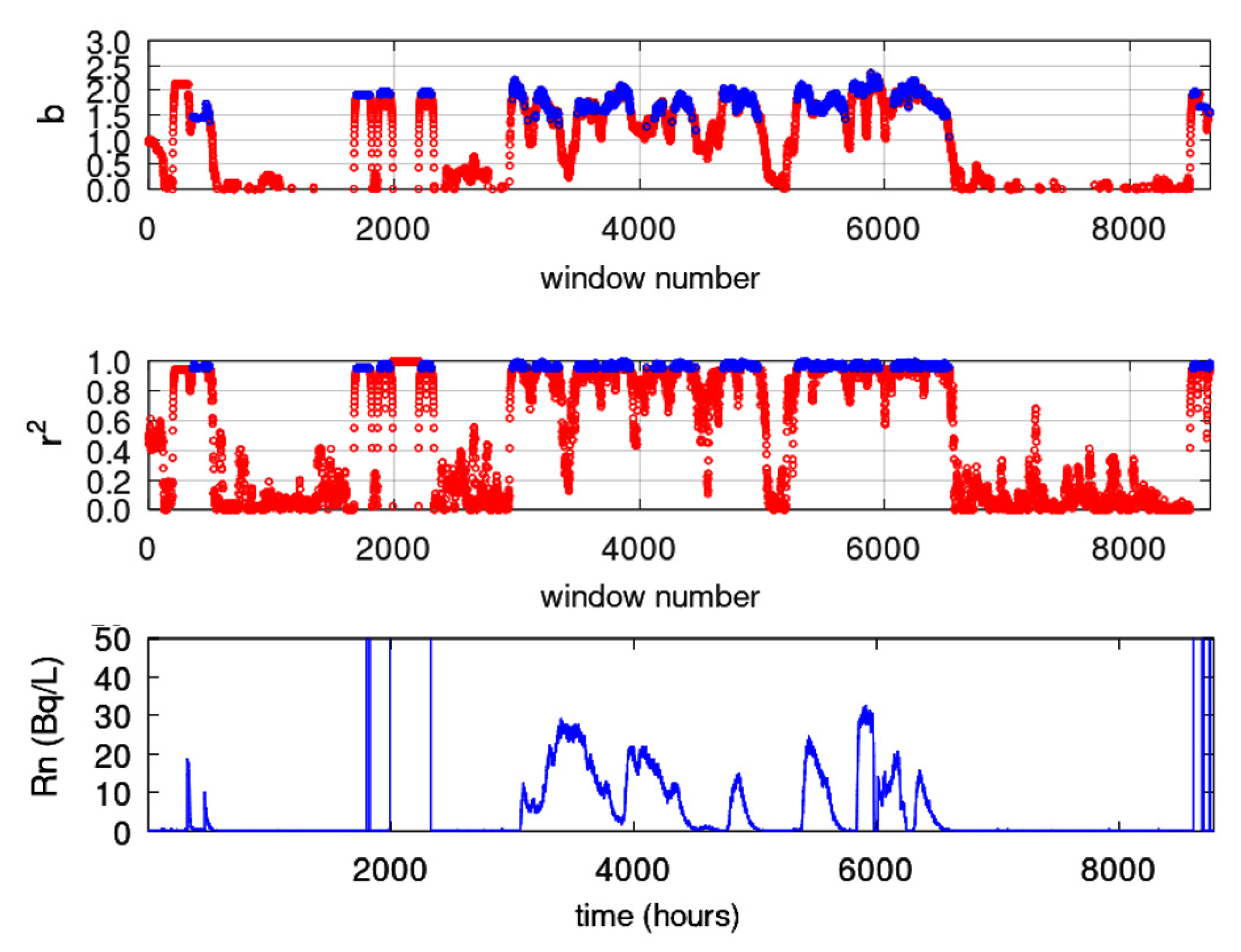

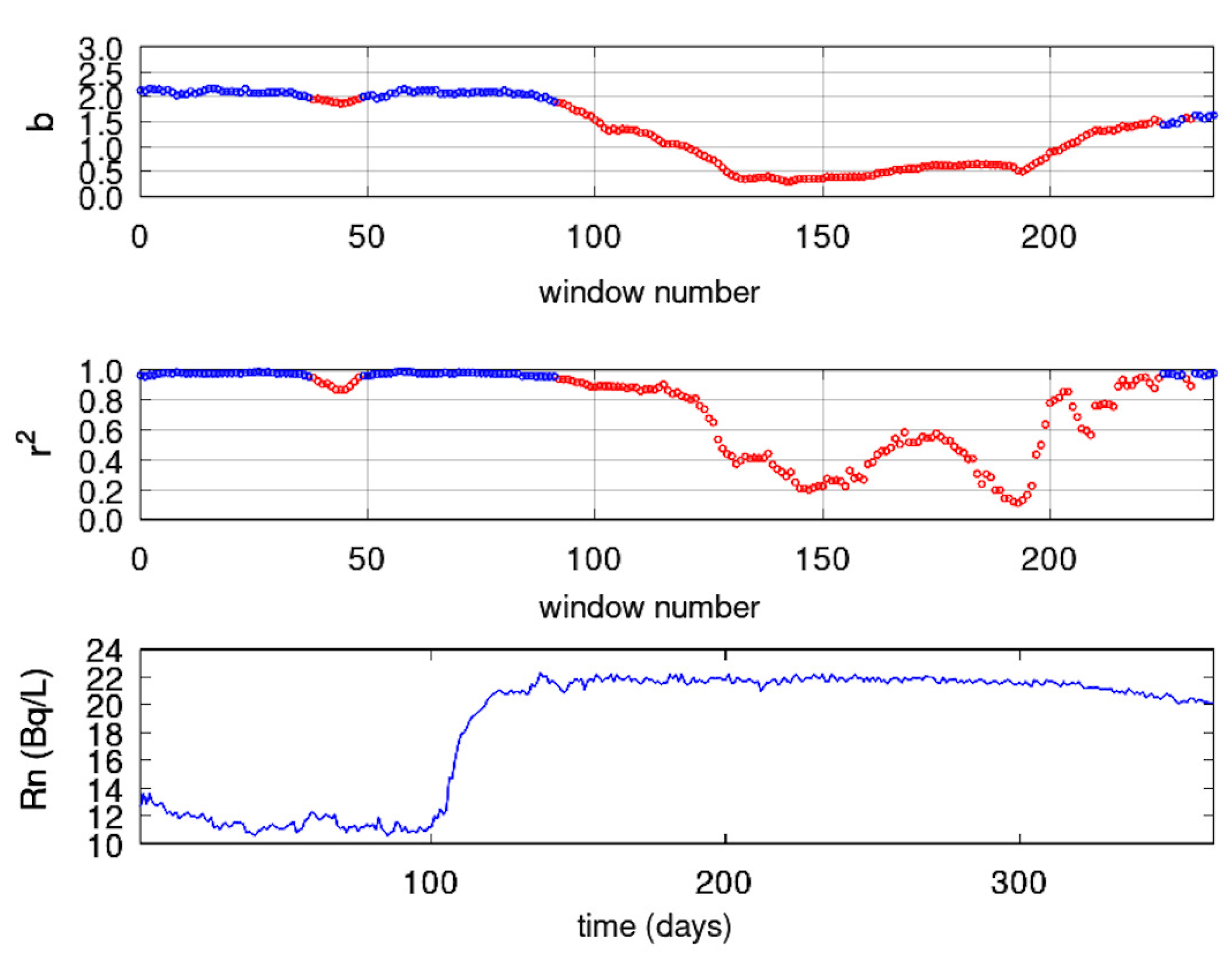

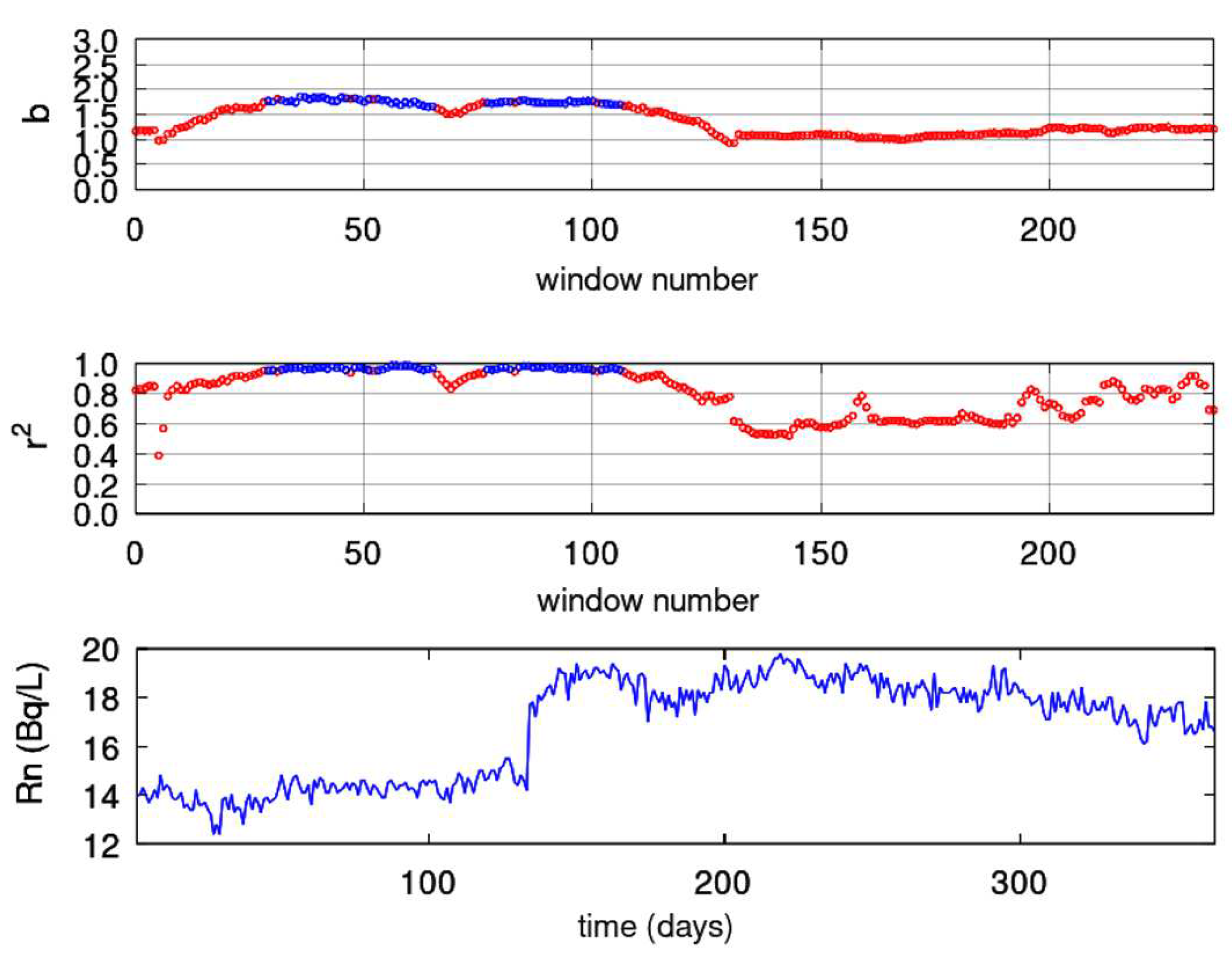

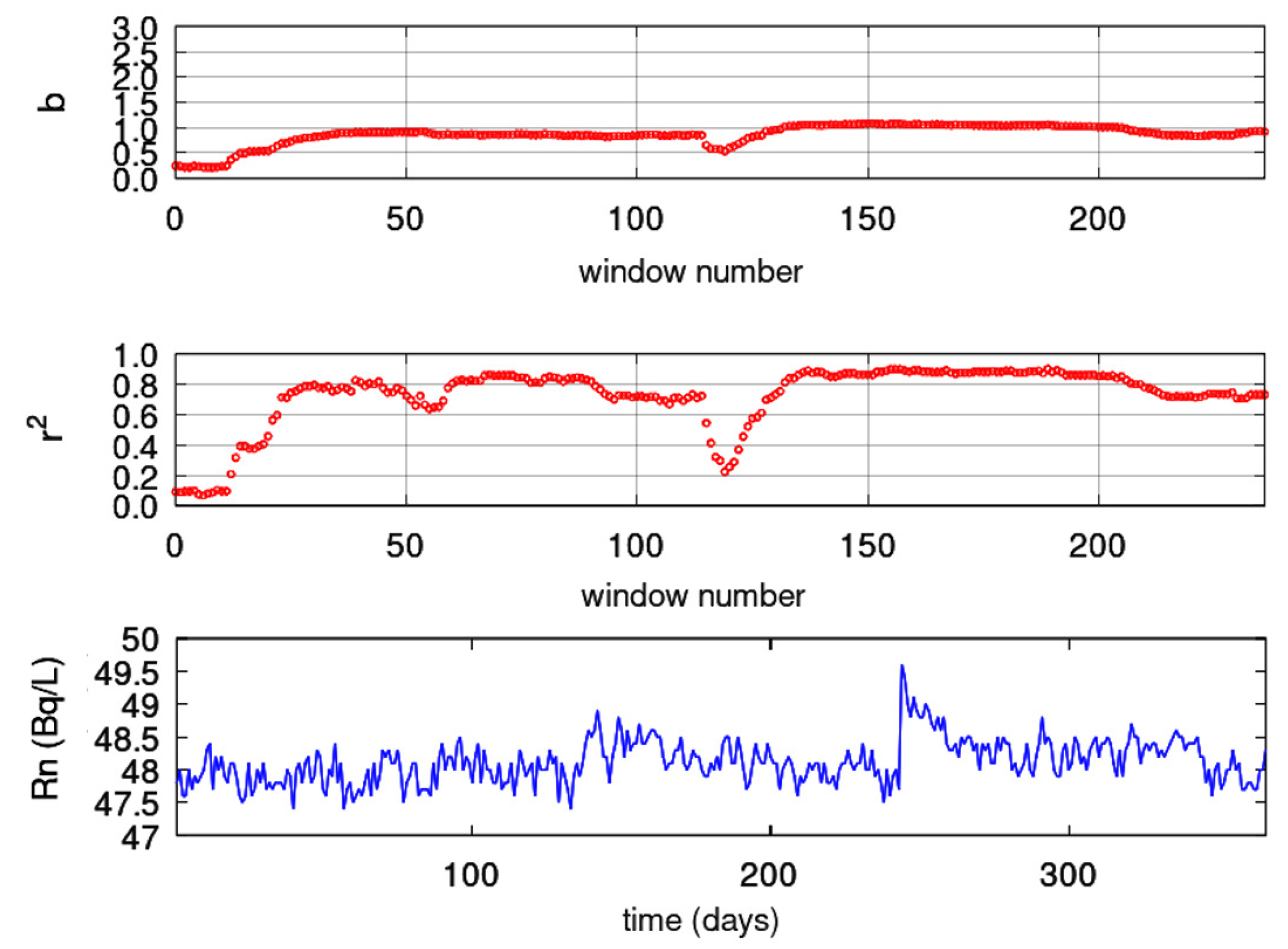

3.3.2. Sliding window DFA

- (a)

- The time series was segmented in windows of 64 samples. This segmentation yields to approximately a two-month series’ part for the PZHS, SPS, GS, MSS LSR stations, which record one measurement per day. The 64 sample window was also employed for the fractal analysis of the data from three monitoring stations of urban air pollution with precisely the same measurement recording rate, namely, 1 measurement per day [29]. In a recent paper for the PZHS station, a 256 segmentation DFA was employed [65], whereas in radon in soil measurements an approach of 128-sample window was utilised [77]. Nevertheless, since the windows are shifted 1 sample forwards (sliding window technique), the whole signal is analysed, except from a 64 sample window, which was the final one. One the other hand, the 64-sample windowing yields to to a 64-hour window for the HSR station of KDS, i.e., an analysis of about 2.5-days. Despite this differentiation it is noteworthy that for a radon station in Pakistan, with the same recording rate as the one of KDS, a 64-window analysis was also utilised [16]. DFA from the data of KDS was analysed with 64 sample windows for consistency.

- (b)

- Every window was fitted using a least squares fit of vs in accordance with Equation (4). The data were fitted to a straight line without seeking cross-overs, as in related literature [1,29,65], with the restriction that the slope of the fit display a square of Spearman’s correlation coefficient above or equal to 0.95.

- (c)

- The window was advanced by one sample, and the steps (A) and (B) were repeated until the signal’s end.

- (d)

- DFA slopes were plotted against time, and the associated plot data were exported to ASCII output files for further use.

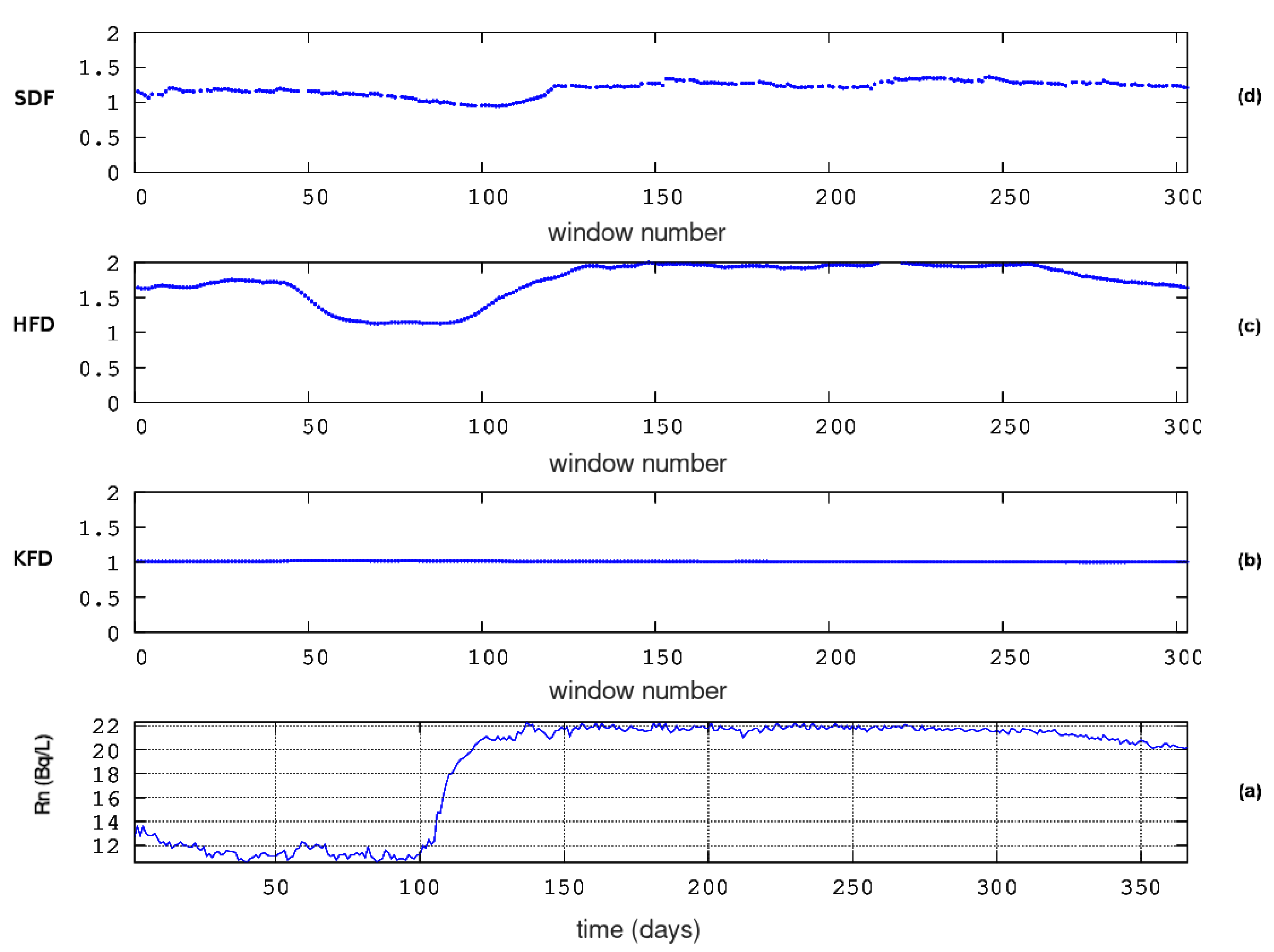

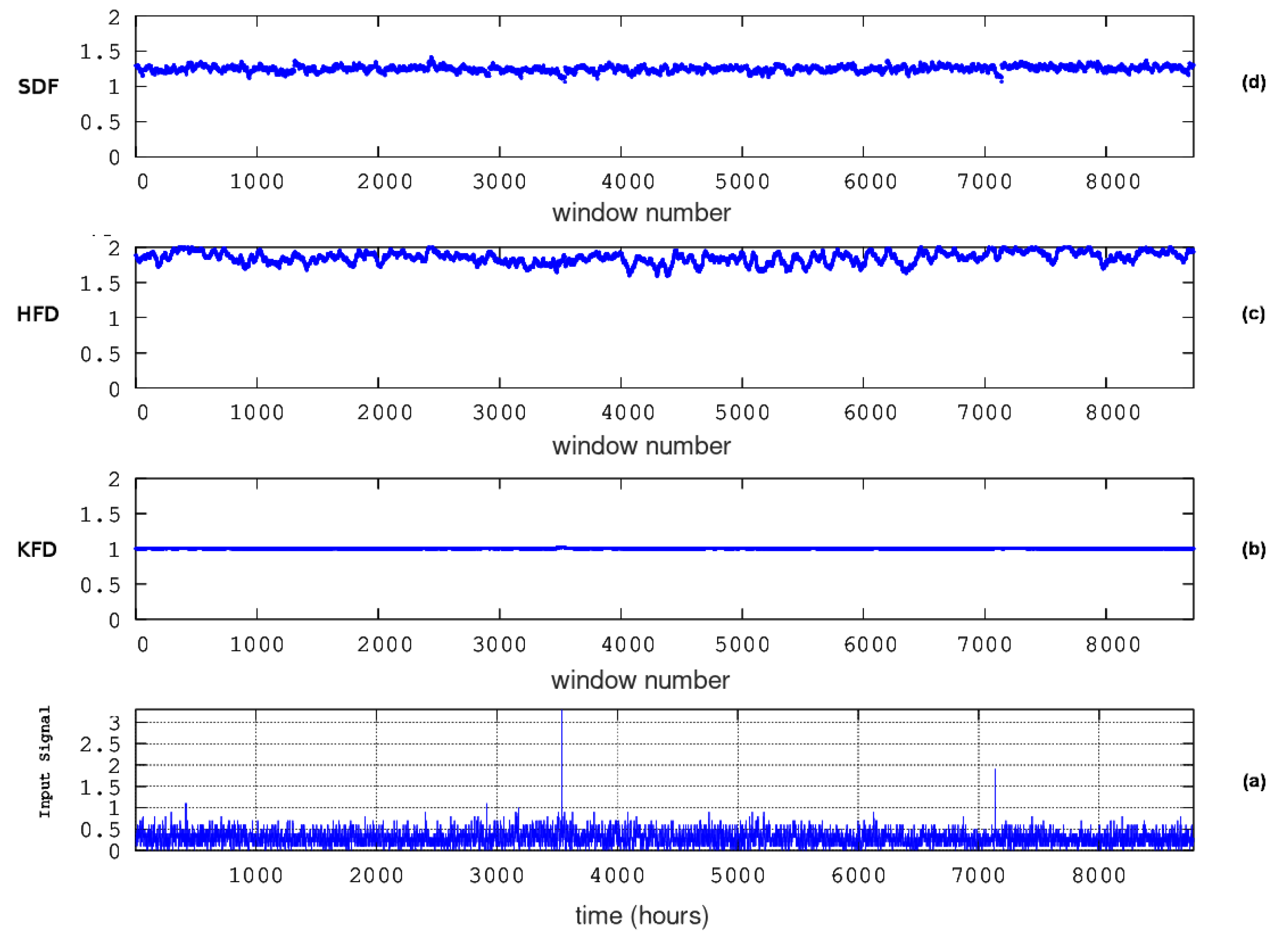

3.4. Fractal Dimension Analysis

3.4.1. Katz’s method

3.4.2. Higuchi’s method

3.4.3. Sevcik’s method

3.4.4. Computational methodology of Fractal Dimension

- (i)

- As in Section 3.3.2, the time series was segmented in windows of 64 samples. As mentioned, this segmentation corresponds for the LSR stations (PZHS, SPS, GS, MSS), approximately to a two-month signal. 64 sample windowing was employed as well in the fractal dimension calculation (with the same methods) from the data of the three LSR urban pollution stations with identical rate of measurements, i.e., 1 measurement per day [29]. As also mentioned in Section 3.3.2, for the HSR station KDS, the 64-sample segmentation, corresponds to approximately, 2.5-days. In a previous fractal dimension analysis (with the same methods) for the PZHS station was implemented with a 256 window [65], however, in a very recent fractal dimension analysis with identical methodology for a HSR radon station in Pakistan of the same rate of measurements as the one of KDS (one measurement per hour), the 64-window approach was utilised [16]. Finally, as in Section 3.3.2 and for consistency with the windowing of the other stations, the 64-sample window was chosen here as well for the KDS station.

- (ii)

-

The fractal dimensions of each method were calculated as follows:

- For the Katz’s method : Fractal dimension is D of Equation (8) for n=64 and =1 collected sample per measurement interval (1 day fo PZHS, SPS, GS and MSS- stations and 1 hour for the KDS station) since corresponds the distance between the points of the series which constitute the parameter L[1,16,29] .

- Higuchi’s method : Equal to the slope D of the first order least-square fit of the logarithmic transformation of Equation (13), namely the relation of versus , for . In the aforementioned analysis for the urban air pollution stations [29], whereas in the analysis of radon in Pakistan [16] and of the electromagnetic disturbances of the Ileia station, Greece, the approach was used. Based on the two latter papers, the was also selected here.

- Sevcik’s method : Equal to the Hausdorff dimension of Equation (16) () for N=64, namely equal to the number of samples in each window which constitutes parameter L.

- (iii)

- Each window was forwarded one sample (sliding window technique) and the procedure (i)-(ii) was iterated until the end of the time series.

- (iv)

- Time evolution plots of the fractal dimensions in accordance to the Katz’s, Higuchi’s and Sevcik’s methods were generated and the partial data were extracted to ASCII files for further use.

3.5. Power-law analysis

3.5.1. Computational methodology of power-law analysis

- (a)

- The time series was separated into 128-sample windows. This is the double window size in comparison to the other two methods. This is done because the power-law analysis does not work well with small sized windows and for this reason the 64-sample window yielded to false runs. For the LSR stations (PZHS, SPS, GS, MSS) this segmentation corresponds to a four-month signal and to a roughly 5 day signal for the KDS station. In previous publications, 128-sample window was employed in parameter estimations [77] for recordings of similar recording rate, while in others, a 512 sample window [91], however, with a recording rate of one measurement per 10 minutes.

- (b)

- The power spectrum, , based on the Morlet wavelet, as well as, the central Morlet frequency, f, were calculated in each segment.

- (c)

- Parameters and were fitted via least-squares. Exponents and power amplification , were computed for every window by each fit , under the constraint, Spearman’s .

- (d)

- The steps (A) through (C) were iterated to the end of the time series. At each iteration, the the window was shifted on sample forwards. As with the other techniques, the whole time series was covered but the last window.

- (e)

- The , data were tabulated and saved in ASCII format for further use.

3.6. Further issues for chaos analysis

3.6.1. Segmentation to Chaos analysis classes

- (a)

-

Class I: This class includes windows that, on the one hand, showed DFA least square log-log fits with Spearman’s coefficient of and, on the other hand, had a scaling exponent for the DFA that was in the range of , i.e., they could be modelled by the fBm class [76]. The Class I segments:

- (b)

-

Class II: This class includes time series windows with DFA textquotesingle’s (i.e., they do not adhere to the prominent fBm class) or (i.e., they adhere to the fractional Gaussian noise (fGn) class). It is important that the Class II segments:

- are the complement of the Class I ones.

3.7. Comparisons of the fractal results

- (1)

- From DFA’ -exponent as:

- (2)

-

From fractal dimension (D) as:(Berry’s equation)

- (3)

- From power-law as:

3.8. Meta-Analysis

- (a)

- (Step-1): According to user-defined thresholds, each ASCII output results file, is computationally scanned for out-of-threshold values. The ASCII files carrying the fractal dimension values are searched for under threshold values, whilst the ASCII files containing the DFA’s exponents and the power law -values are looked for over threshold values. New ASCII step-1 files are generated that contain the out-of-threshold values.

- (b)

-

(Step 2): Under the restriction that each segment’s first sample date is arbitrarily considered as the date of the whole segment, the step-1 ASCII files of are computationally filtered to find areas with common dates. The above computational process, results in the full coverage of all dates except the one of the last window. The whole procedure is iterated in the results of all possible combinations of:

- DFA versus fractal analysis or versus at least two fractal dimension calculation techniques (6 combinations);

- Fractal analysis versus at least two fractal dimension calculation techniques (4 combinations);

- One fractal dimension calculation technique versus the other two (3 combinations);

4. Results and discussion

-

If , then the associated time series is a temporal fractal and follows the Class-I category;

- If , the time series follows anti-persistent paths;

- If , the time series follows persistent paths;

-

If , the time series is of low predictability and follows the Class-II category; Moreover:

- If , the fluctuations of the related processes are not growing and, hence, a stationary system describes the series;

- If , the underlying dynamics are random and the related system has no memory;

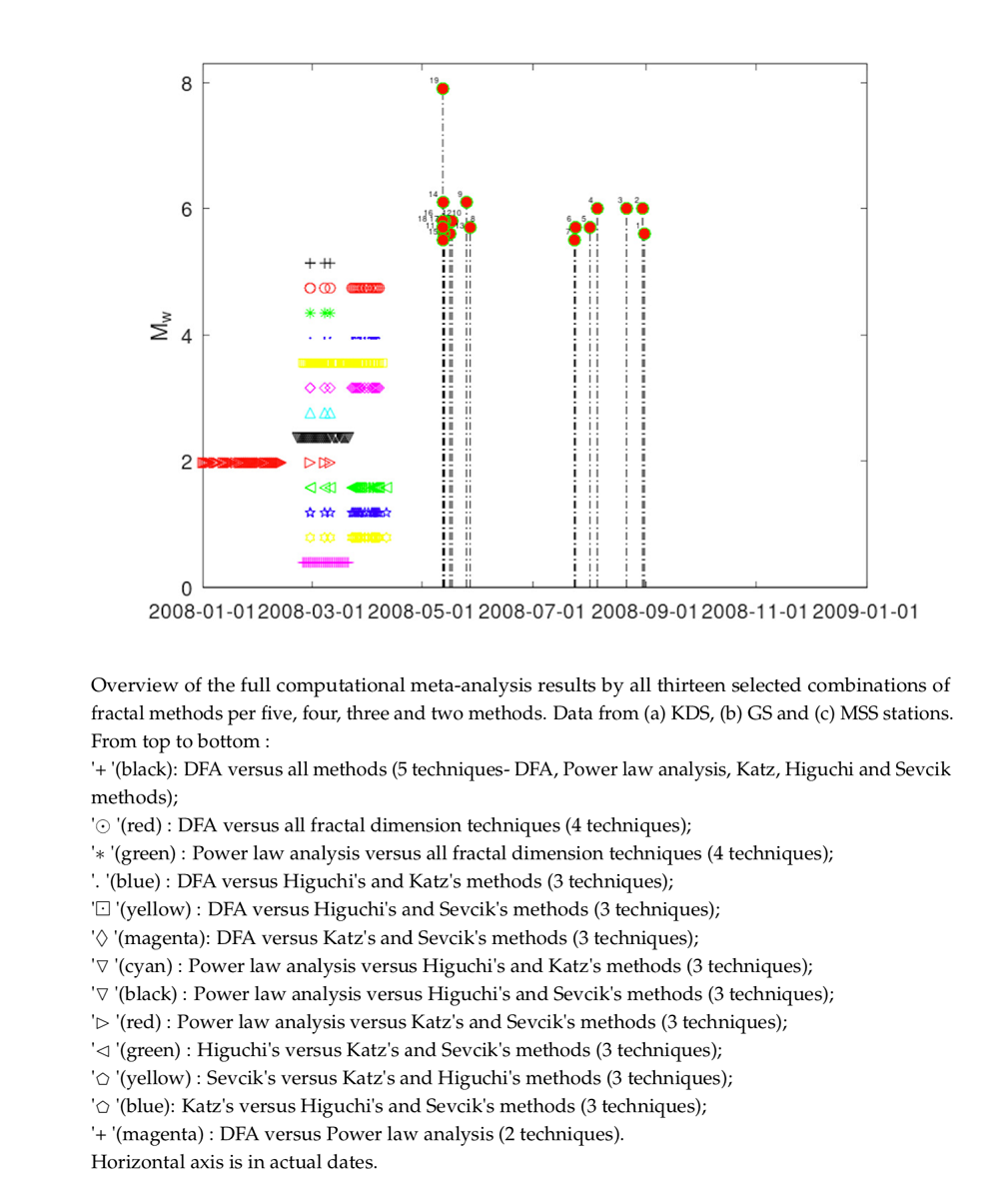

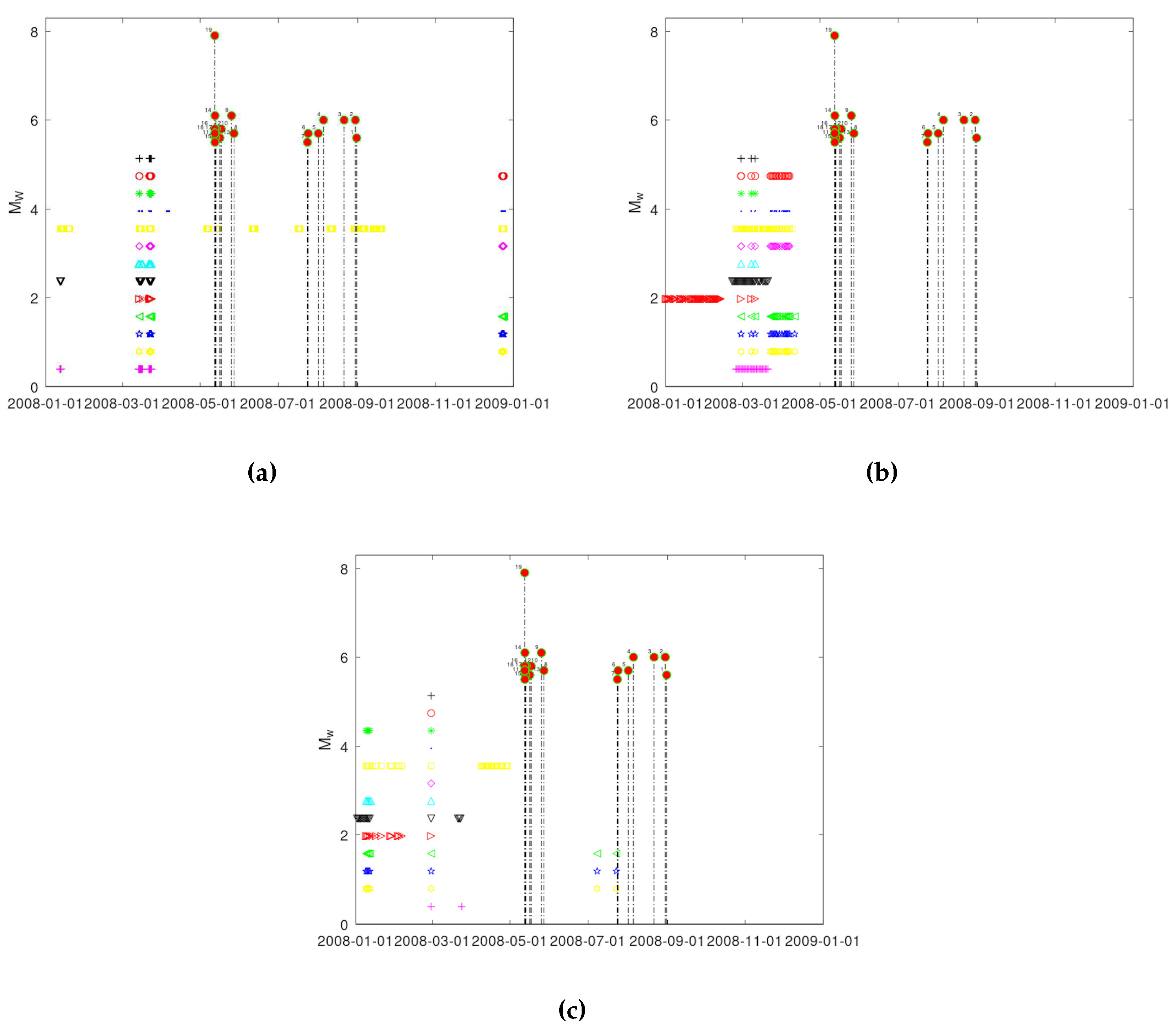

- (a)

-

All over- or under-threshold results of all fractal methods (step 1, meta-analysis) for the KDS, MSS and GS stations. The threshold results of each station are combined per two, three, four and five methods (step 2, meta-analysis) (total 13 combinations) versus all 19 earthquakes of Table 2 and Figure 17.As mentioned in the previous paragraph, it is not only to identify footprints by one or more techniques (done already here as well) but more important is to link different techniques focusing on similar aspects of the problem in hand. To achieve this:

- (1)

- The exact over or under threshold dates were located computationally from the fractal outputs of each station (step-1, meta analysis). These dates are Year, Month, Day, Hour for the HSR station KDS and Year, Month, Day for MSS and GS stations. This is done through a serial search.

- (2)

- The common threshold dates from all different techniques were found through an incremental computational search. The outputs used are from all methods and with up to 13 different combination of these. All outputs were generated through special software and are stored in computer for use.

- (3)

- The earthquake data from USGS [109] were transformed to an adequate ASCII file for the generation of the final plot.

- (b)

- Wherever the symbols of different methods coincide in time, this means that the signs of seismicity is provided by more than one method. If all 13 methods coincide this means that the evidence is maximised. More techniques pointing to similar findings, more rigid the evidence is. The reader should stress that the coincidence is done on the step 1 results, that is on the fractal outputs.

Conclusions

Author Contributions

References

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Petraki, E.; Yannakopoulos, P.H.; Priniotakis, G.; Voyiatzis, I.; Cantzos, D. Long-lasting patterns in 3 kHz electromagnetic time series after the ML= 6.6 earthquake of 2018-10-25 near Zakynthos, Greece. Geosciences 2020, 10, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicerone, R.; Ebel, J.; Britton, J. A systematic compilation of earthquake precursors. Tectonophysics 2009, 476, 371–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HOUGH, S. The Great Quake Debate: The Crusader, the Skeptic, and the Rise of Modern Seismology; University of Washington Press, 2020.

- Hayakawa, M.; Hobara, Y. Current status of seismo-electromagnetics for short-term earthquake prediction. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk 2010, 1, 115–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molchanov, O.A.; Hayakawa, M. Seismo-Electromagnetics and Related Phenomena: History and Latest Results; Number A8, TERRAPUB: Tokyo, 2008; p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzounov, D.; Pulinets, S.; Hattori, K.; Taylor, P. Pre-Earthquake Processes: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Earthquake Prediction Studies Posters; Wiley. John Wiley and Sons., 2018; p. 384.

- Petraki, E.; Nikolopoulos, D.; Nomicos, C.; Stonham, J.; Cantzos, D.; et al. Electromagnetic Pre-earthquake Precursors: Mechanisms, Data and Models-A Review. J. Earth Sci. Clim. Change 2015, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Petraki, E.; Nikolopoulos, D.; Panagiotaras, D.; Cantzos, D.; Yannakopoulos, P.; et al. Radon-222: A Potential Short-Term Earthquake Precursor. J Earth Sci Clim Change 2015, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Uyeda, S.; Nagao, T.; Kamogawa, M. Short-term earthquake prediction: Current status of seismo-electromagnetics. Tectonophysics 2009, 470, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, L.; Picozza, P.; Sotgiu, A. A Critical Review of Ground Based Observations of Earthquake Precursors. Frontiers in Earth Science 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Deb, A.; Sengupta, R. Anomalous radon emission as precursor of earthquake. J. Appl. Geophys. 2009, 187, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Dong, P.; Zhu, B.; Shi, Y. Stress Shadow on the Southwest Portion of the Longmen Shan Fault Impacted the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake Rupture. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2018, 123, 9963–9981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, F.; Sun, P. Landslide hazards triggered by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, Sichuan, China. Landslides 2009, 6, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Koper, K.D.; Sufri, O.; Zhu, L.; Hutko, A.R. Rupture imaging of the Mw 7.9 12 May 2008 Wenchuan earthquake from back projection of teleseismic P waves. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2009, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Matsoukas, C.; Yannakopoulos, P.H.; Petraki, E.; Cantzos, D.; Nomicos, C. Long-Memory and Fractal Trends in Variations of Environmental Radon in Soil: Results from Measurements in Lesvos Island in Greece, J Earth Sci. J. Earth Sci. Clim. Change 2018, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rafique, M.; Iqbal, J.; Shah, S.A.A.; Alam, A.; Lone, K.J.; Barkat, A.; Shah, M.A.; Qureshi, S.A.; Nikolopoulos, D. On fractal dimensions of soil radon gas time series. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 2022, 227, 105775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Wang, G.; Wang, C.y.; Manga, M.; Liu, C. Comparison of hydrological responses to the Wenchuan and Lushan earthquakes. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2014, 391, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, D. A preliminary study of post-seismic effects of radon following the Ms 8.0 Wenchuan earthquake. Radiation Measurements 2012, 47, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Ness, J.W.V. Fractional Brownian motions, fractional noises and applications. J. Soc. Ind. Appl. Math 1968, 10, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, I.O.; Landa, O.; Fossion, R.; Frank, A. Scale invariance, self-similarity and critical behaviour in classical and quantum system. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2012, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, M.; Ibrahim, K. Existence of long memory in ozone time series. Sains Malaysiana 2012, 41, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar]

- Vadrevu, K.P. Fractal analysis revealed persistent correlations in long-term vegetation fire data in most South and Southeast Asian countries. Environmental Research Communications 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, R.M. Simple mathematical models with very complicated dynamics. Nature 1976, 261, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugihara, G.; May, R. Nonlinear forecasting as a way of distinguishing chaos from measurement error in time series. Nature 1990, 344, 734–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liang, J.; Li, Y.; Shi, K. Fractal analysis of impact of PM2.5 on surface O3 sensitivity regime based on field observations. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 858, 160136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastén, D.; Pavez-Orrego, C. Multifractal time evolution for intraplate earthquakes recorded in southern Norway during 1980–2021. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2023, 167, 113000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Moustris, K.; Petraki, E.; Cantzos, D. Long-memory traces in PM _ 10 time series in Athens, Greece: investigation through DFA and R/S analysis. Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics 2021, 133, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelidze, T.; Matcharashvili, T.; Mepharidze, E.; Dovgal, N. Complexity in Geophysical Time Series of Strain/Fracture at Laboratory and Large Dam Scales: Review. Entropy 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Moustris, K.; Petraki, E.; D., K.; Cantzos, D. Fractal and long-memory traces in PM10 time series in Athens, Greece. Environmnets 2019, 6, 1–19.

- Hurst, H. Long term storage capacity of reservoirs. Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1951, 116, 770–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, H.; Black, R.; Simaiki, Y. Long-term Storage: An Experimental Study; Constable: London, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, T.; Martınez-Gonzalez, C.; Manjarrez, J.; Plascencia, N.; Balankin, A. Fractal Analysis of EEG Signals in the Brain of Epileptic Rats, with and without Biocompatible Implanted Neuroreservoirs. AMM 2009, 15, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftaxias, K.; Balasis, G.; Contoyiannis, Y.; Papadimitriou, C.; Kalimeri, M. Unfolding the procedure of characterizing recorded ultra low frequency, kHZ and MHz electromagnetic anomalies prior to the L’Aquila earthquake as pre-seismic ones - Part 2. NHESS 2010, 10, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilcik, A.; Anderson, C.; Rozelot, J.; Ye, H.; Sugihara, G.; Ozguc, A. Nonlinear Prediction of Solar Cycle 24. Astrophysics J. 2009, 693, 1173–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Khondekar, M. An investigation of the relationship between the CME and the Geomagnetic Storm. Astronomy and Computing 2023, 43, 100695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero, M.S.; Segovia, J.T.; Perez, J.G. Some comments on Hurst exponent and the long memory processes on capital Markets. Physica A 2008, 387, 5543–5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaev, A.; Makshanov, A.; Grigoriev, D. The Genesis of Uncertainty: Structural Analysis of Stochastic Chaos in Finance Markets. Complexity 2023, 2023, 1302220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sienes, L.; Grande, M.; Losada, J.C.; Borondo, J. The Hurst Exponent as an Indicator to Anticipate Agricultural Commodity Prices. Entropy 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogl, M. Hurst exponent dynamics of S&P 500 returns: Implications for market efficiency, long memory, multifractality and financial crises predictability by application of a nonlinear dynamics analysis framework. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2023, 166, 112884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattatreya, G. Hurst Parameter Estimation from Noisy Observations of Data Traffic Traces. 4th WSEAS international conference on electronics, control and signal processing, 2005; 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Wang, H.; Zhou, X.; Fu, R. A Driving Fatigue Feature Detection Method Based on Multifractal Theory. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 19046–19059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Chang, F. The long-memory temporal dependence of traffic crash fatality for different types of road users. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2022, 607, 128210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Polygiannakis, J.; Kapiris, P.; Peratzakis, A.; Eftaxias, K.; Yao, X. Fractal spectral analysis of pre-epileptic seizures in terms of criticality. J. Neural Eng. 2005, 2, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Ipuz, F.; Torres, A.; García-Jiménez, M.; Basar, C.; Cascón, J.; Mateo, J. Prediction of patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy from healthy controls using machine learning from scalp EEG recordings. Brain Research 2023, 1798, 148131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayanto, I.; Humairani, A.; Hadiyoso, S.; Rizal, A.; Prasanna, D.L.; Tripathi, S.L. Epileptic seizure detection on a compressed EEG signal using energy measurement. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 85, 104872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Siddiqi, A. Wavelet based Hurst exponent and fractal dimensional analysis of Saudi climatic dynamics. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2009, 39, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petraki, E. Electromagnetic Radiation and Radon-222 Gas Emissions as Precursors of Seismic Activity. PhD thesis, Department of Electronic and Computer Engineering, Brunel University London, UK, 2016.

- Fujinawa, Y.; Takahashi, K. Electromagnetic radiations associated with major earthquakes. Phys. Earth Planet Inter 1998, 105, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Ida, Y.; Gotoh, K. Multifractal analysis for the ULF geomagnetic data during the Guam earthquake. In Electromagnetic Compatibility and Electromagnetic Ecology. In Proceedings of the IEEE 6th International Symposium on June 2005. 239-243; 2005; pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa, M. VLF/LF radio sounding of ionospheric perturbations associated with earthquakes. Sensors 2007, 7, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Alam, A.; Petraki, E.; Papoutsidakis, M.; Yannakopoulos, P.; Moustris, K.P. Stochastic and self-organisation patterns in a 17-year PM10 time series in Athens, Greece. Entropy 2021, 23, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skordas, E.S. On the increase of the "non-uniform" scaling of the magnetic field variations before the M(w)9.0 earthquake in Japan in 2011. Chaos 2014, 24, 023131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, H.E. Powerlaws and universality. Nature 1995, 378, 597–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlis, N.; Skordas, E.; Varotsos, P.; Nagao, T.; M. Kamogawa, M.; Tanaka, H.; Uyeda, S. Minimum of the order parameter fluctuations of seismicity before major earthquakes in Japan. In Proceedings of the Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2013, Vol. 110, 34, pp. 13734–13738.

- Becker, M.; Karpytchev, M.; Hu, A. Increased exposure of coastal cities to sea-level rise due to internal climate variability. Nature Climate Change, 2023; 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, K.; Ausloos, M. Application of the detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA) method for describing cloud breaking. Physica A 1999, 274, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koscielny-Bunde, E.; Bunde, A.; Havlin, S.; Roman, H.E.; Goldreich, Y.; Schellnhuberet, H. Indication of a Universal Persistence Law Governing Atmospheric Variability. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 729–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, F.; Fattahi, M.H. Climate change-induced influences on the nonlinear dynamic patterns of precipitation and temperatures (case study: Central England). Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 2023; 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhares, R.R. Fractional poisson process: Long-range dependence in DNA sequences. Model Assisted Statistics and Applications 2023, 18, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Mietus, J.; Havlin, S.; Stanley, H.; Goldberger, A. Long-range anti-correlations and non-Gaussian behavior of the heartbeat. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 70, 1343–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buldyrev, S.V.; Goldberger, A.L.; Havlin, S.; Mantegna, R.N.; Matsa, M.E.; Peng, C.K.; Simons, M.; Stanley, H.E. Long-range correlation properties of coding and noncoding DNA sequences: GenBank analysis. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Topics 1995, 51, 5084–5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, P.C.; Rosenblum, M.G.; Peng, C.K.; Mietus, J.E.; Havlin, S.; Stanley, H.E.; Goldberger, A.L. Multifractality in human heartbeat dynamics. Nature 1999, 399, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo-March, M.; Moya-Ramón, M.; Javaloyes, A.; Sánchez-Muñoz, C.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Validity of detrended fluctuation analysis of heart rate variability to determine intensity thresholds in elite cyclists. European Journal of Sport Science 2023, 23, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, B.; Schaffarczyk, M.; Gronwald, T. Improved Estimation of Exercise Intensity Thresholds by Combining Dual Non-Invasive Biomarker Concepts: Correlation Properties of Heart Rate Variability and Respiratory Frequency. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, A.; Wang, N.; Zhao, G.; Mehmood, T.; Nikolopoulos, D. Long-lasting patterns of radon in groundwater at Panzhihua, China: Results from DFA, fractal dimensions and residual radon concentration. GEOCHEMICAL JOURNAL 2019, 53, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Wang, N.; Zhao, G.; Barkat, A. Implication of radon monitoring for earthquake surveillance using statistical techniques: a case study of Wenchuan earthquake. Geofluids 2020, 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftaxias, K.; Balasis, G.; Contoyiannis, Y.; Papadimitriou, C.; Kalimeri, M.; Athanasopoulou, L.; Nikolopoulos, S.; Kopanas, J.; Antonopoulos, G.; Nomicos, C. Unfolding the procedure of characterizing recorded ultra low frequency, kHZ and MHz electromagnetic anomalies prior to the L’Aquila earthquake as pre-seismic ones-Part 1. Nat. Hazard Earth Sys. 2009, 9, 1953–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, K.; Hayakawa, M.; Smirnova, N.; Hattori, K. Fractal analysis of seismogenic ULF emissions. Phys. Chem. Earth 2004, 29, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Ida, Y.; Gotoh, K. Fractal (mono- and multi-) analysis for the ULF data during the 1993 Guam earthquake for the study of prefracture criticality. Current Development in Theory and Applications of Wavelets 2008, 2, 159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Varotsos, P.; Sarlis, N.; Skordas, E. Natural Time Analysis: The new view of time. Precursory Seismic Electric Signals, Earthquakes and other Complex Time- Series; Springer-Verlag: Berlin Heidelberg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Varotsos, P.A.; Sarlis, N.V.; Skordas, E.S. Order Parameter and Entropy of Seismicity in Natural Time before Major Earthquakes: Recent Results. Geosciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Ivanov, P.; Chen, Z.; Carpena, P.; Stanley, H. Effect of trends on Detrended Fluctuation Analysis. Phys Rev E 2001, 64, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Buldyrev, S.; Simons, M.; Havlin, S.; Stanley, H.; Goldberger, A. On the mosaic organization of DNA sequences. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 49, 1685–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Havlin, S.; Stanley, H.; Goldberger, A. Quantification of scaling exponents and crossover phenomena in nonstationary heartbeat time series. Chaos 1995, 5, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Hausdor, J.; Havlin, S.; Mietus, J.; Stanley, H.; Goldberger, A. Multiple-time scales analysis of physiological time series under neural control. Physica A 1998, 249, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Yannakopoulos, P.H.; Petraki, E.; Cantzos, D.; Nomicos, C. Long-Memory and Fractal Traces in kHz-MHz Electromagnetic Time Series Prior to the ML=6.1, 12/6/2007 Lesvos, Greece Earthquake: Investigation through DFA and Time-Evolving Spectral Fractals. J. Earth Sci. Clim. Change 2018, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Petraki, E.; Nomicos, C.; Koulouras, G.; Kottou, S.; Yannakopoulos, P.H. Long-Memory Trends in Disturbances of Radon in Soil Prior ML=5.1 Earthquakes of 17 November 2014 Greece. J. Earth Sci. Clim. Change 2015, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, M. Fractals and the analysis of waveforms. Comput. Biol. Med. 1988, 18, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavendra, B.; Dutt, D.N. Computing Fractal Dimension of Signals using Multiresolution Box-counting Method. International Journal of Electrical, Computer, Energetic, Electronic and Communication Engineering 2010, 4, 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, T. Approach to an irregular time series on basis of the fractal theory. Physica D 1988, 31, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, F.C.; Ramirez-Rojas, A.; Pavia-Miller, C.; Angulo-Brown, F.; E, E.Y.; Peralta, J. A comparison between spectral and fractal methods in electrotelluric time series. Revista Mexicana de Fisica 1999, 45, 298–302. [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre, F.C.; Gonzaalez-Trejo, J.; Real-Ramírez, C.; Hoyos-Reyes, L. Fractal dimension algorithms and their application to time series associated with natural phenomena. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2013, 475, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevcik, C. On fractal dimension of waveforms. Chaos Solit. Fract. 2006, 27, 579–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantzos, D.; Nikolopoulos, D.; Petraki, E.; Yannakopoulos, P.H.; Nomicos, C. Earthquake precursory signatures in electromagnetic radiation measurements in terms of day-to-day fractal spectral exponent variation: analysis of the eastern Aegean 13/04/2017–20/07/2017 seismic activity. J. Seismol. 2018, 22, 1499–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ida, Y., H.; M. . Fractal analysis for the ULF data during the 1993 Guam earthquake to study prefracture criticality. Nonlin. Processes Geophys. 2012, 13, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ida, Y., Y.; Li, D.; Q. , S.; H., H.; M.. Fractal analysis of ULF electromagnetic emissions in possible association with earthquakes in China. Nonlin. Processes Geophys. 2012, 19, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, N.; Hayakawa, M. Fractal characteristics of the ground-observed ULF emissions in relation to geomagnetic and seismic activities. J. Atmos. Sol. Ter. Phy. 2007, 69, 1833–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonaiguchi, N.; Ida, Y.; Hayakawa, M.; Masuda, S. Fractal analysis for VHF electromagnetic noises and the identification of preseismic signature of an earthquake. J. Atmos. Sol. Ter. Phy. 2007, 69, 1825–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftaxias, K. Footprints of non-extensive Tsallis statistics, self-affinity and universality in the preparation of the L’Aquila earthquake hidden in a pre-seismic EM emission. Physica A 2010, 389, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapiris, P.; Peratzakis, J.P.A.; Nomikos, K.; K. Eftaxias. VHF-electromagnetic evidence of the underlying pre-seismic critical stage. Earth Planets Space 2002, 54, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Petraki, E.; Marousaki, A.; Potirakis, S.; Koulouras, G.; Nomicos, C.; Panagiotaras, D.; Stonhamb, J.; Louizi, A. Environmental monitoring of radon in soil during a very seismically active period occurred in South West Greece. J. Environ. Monit. 2012, 14, 564–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Wang, N.; Petraki, E.; Barkat, A.; Huang, F.; Shah, M.A.; Cantzos, D.; Priniotakis, G.; Yannakopoulos, P.H.; Papoutsidakis, M.; et al. Fluctuation Dynamics of Radon in Groundwater Prior to the Gansu Earthquake, China (22 July 2013: M s= 6.6): Investigation with DFA and MFDFA Methods. Pure and Applied Geophysics 2021, 178, 3375–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telesca, L.; Lasaponara, R. Vegetational patterns in burned and unburned areas investigated by using the detrended fluctuation analysis. Physica A 2006, 368, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftaxias, K.; Contoyiannis, Y.; Balasis, G.; Karamanos, K.; Kopanas, J.; Antonopoulos, G.; Koulouras, G.; Nomicos, C. Evidence of fractional-Brownian-motion-type asperity model for earthquake generation in candidate pre-seismic electromagnetic emissions. Nat. Hazard Earth Sys. 2008, 8, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotsos, P.; Alexopoulos, K. Physical properties of the variations of the electric field of the earth preceding earthquakes, I. Tectonophysics 1984, 110, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotsos, P.; Alexopoulos, K. Physical properties of the variations of the electric field of the earth preceding earthquakes, II. Tectonophysics 1984, 110, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotsos, P.; Sarlis, N.; Lazaridou, M.B.N. Statistical evaluation of earthquake prediction results. Comments on the success rate and alarm rate, Acta Geophys. Pol 1996, 44, 329–347. [Google Scholar]

- Varotsos, P.; Sarlis, N.; Skordas, E. Magnetic field variations associated with SES. The instrumentation used for investigating their detectability. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B 2001, 77, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petraki, E.; Nikolopoulos, D.; Chaldeos, Y.; Koulouras, G.; Nomicos, C.; Yannakopoulos, P.H.; Kottou, S.; Stonham, J. Fractal evolution of MHz electromagnetic signals prior to earthquakes: results collected in Greece during 2009. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk 2016, 7, 550–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinault, J.; Baubron, J. Signal processing of soil gas radon, atmospheric pressure, moisture, and soil temperature data: A new approach for radon concentration modeling. J. Geoph. Res. Sol. EA 1996, 101, 3157–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftaxias, K.; Panin, V.; Deryugin, Y. Evolution-EM signals before earthquakes in terms of mesomechanics and complexity. Phys. Chem. Earth 2007, 29, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Eftaxias, V. Sgrigna, T.C. Mechanical and electromagnetic phenomena accompanying preseismic deformation: From laboratory to geophysical scale. Tectonophysics 2007, 341, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh, K.; Hayakawa, M.; Smirnova, N. Fractal analysis of the ULF geomagnetic data obtained at Izu Peninsula, Japan in relation to the nearby earthquake swarm of June-August 2000. Nat. Haz. Earth Sys. 2003, 3, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Kawate, R.; Molchanov, O.; Yumoto, K. Results of ultra-low-frequency magnetic field measurements during the Guam earthquake of 8 August 1993. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1996, 23, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Itoh, T.; Hattori, K.; Yumoto, K. ULF electromagnetic precursors for an earthquake at Biak, Indonesia on February 17, 1996. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2000, 27, 1531–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapiris, P.; Eftaxias, K.; Nomikos, K.; Polygiannakis, J.; Dologlou, E.; Balasis, G.; Bogris, N.; Peratzakis, A.; Hadjicontis, V. Evolving towards a critical point: A possible electromagnetic way in which the critical regime is reached as the rupture approaches. Nonlinear Proc. Geoph. 2003, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, N.; Hayakawa, M.; Gotoh, K. Precursory behavior of fractal characteristics of the ULF electromagnetic fields in seismic active zones before strong earthquakes. Phys. Chem. Earth 2004, 29, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, N.A.; Kiyashchenko, D.A.T.; N. , V.; Hayakawa, M. Multifractal Approach to Study the Earthquake Precursory Signatures Using the Ground-Based Observations. Review of Applied Physics 2013, 2, 3. [Google Scholar]

- USGS. Available online: https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/map/?extent=22.41103,91.51611&extent=35.56798,113.57666&range=search&baseLayer=terrain&timeZone=utc&search=%7B%22name%22:%22Search%20Results%22,%22params%22:%7B%22starttime%22:%222008-01-01%2000:00:00%22,%22endtime%22:%222009-01-01%2000:00:00%22,%22maxlatitude%22:36.844,%22minlatitude%22:22.999,%22maxlongitude%22:116.323,%22minlongitude%22:96.504,%22minmagnitude%22:5.5,%22orderby%22:%22time%22%7D%7D (accessed on 26 May 2023).

| Station Code | Station Name | Latitude | Longitude | Distance (Km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KDS | Kangding station | 30.12 | 102.17 | 152.2 |

| GS | Ganzi station | 31.61 | 100.01 | 325.5 |

| MSS | Mingshan station | 30.1 | 103.1 | 105.6 |

| PZHS | Panzhihua station | 26.51 | 101.74 | 526.0 |

| SPS | Sonpan station | 32.65 | 103.6 | 182.5 |

| i/i | Year | Month | Day | Hour | Minute | Second | Latitude | Longitude | Depth (m) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2008 | 8 | 31 | 8 | 31 | 10 | 5.6 | 26.232 | 101.97 | 10 |

| 2 | 2008 | 8 | 30 | 8 | 30 | 53 | 6.0 | 26.241 | 101.889 | 11 |

| 3 | 2008 | 8 | 21 | 12 | 24 | 30 | 6.0 | 25.039 | 97.697 | 10 |

| 4 | 2008 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 49 | 17 | 6.0 | 32.756 | 105.494 | 6 |

| 5 | 2008 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 32 | 43 | 5.7 | 32.033 | 104.722 | 11 |

| 6 | 2008 | 7 | 24 | 9 | 30 | 9 | 5.7 | 32.747 | 105.542 | 10 |

| 7 | 2008 | 7 | 23 | 19 | 54 | 44 | 5.5 | 32.752 | 105.498 | 4 |

| 8 | 2008 | 5 | 27 | 8 | 37 | 51 | 5.7 | 32.71 | 105.54 | 10 |

| 9 | 2008 | 5 | 25 | 8 | 21 | 49 | 6.1 | 32.56 | 105.423 | 18 |

| 10 | 2008 | 5 | 17 | 8 | 25 | 48 | 5.8 | 32.24 | 104.982 | 9 |

| 11 | 2008 | 5 | 16 | 5 | 25 | 47 | 5.6 | 31.355 | 103.351 | 3 |

| 12 | 2008 | 5 | 13 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 5.8 | 30.89 | 103.194 | 9 |

| 13 | 2008 | 5 | 12 | 20 | 8 | 50 | 5.6 | 31.413 | 103.889 | 21.7 |

| 14 | 2008 | 5 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 2 | 6.1 | 31.214 | 103.618 | 10 |

| 15 | 2008 | 5 | 12 | 9 | 42 | 24 | 5.5 | 31.527 | 104.092 | 10 |

| 16 | 2008 | 5 | 12 | 6 | 43 | 14 | 5.8 | 31.211 | 103.715 | 10 |

| 17 | 2008 | 5 | 12 | 6 | 42 | 8 | 5.7 | 31.342 | 104.682 | 10 |

| 18 | 2008 | 5 | 12 | 6 | 61 | 56 | 5.7 | 31.586 | 104.032 | 10 |

| 19 | 2008 | 5 | 12 | 6 | 28 | 1 | 7.9 | 31.002 | 103.322 | 19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).