1. Introduction

Pregnancy related myocardial infarction is a rare event estimated to occur in 2.8 to 8.1 per 100 000 deliveries but represents a consistent percentage of maternal cardiac deaths (over 20%). [

1] The frequent occurrence of non-atherosclerotic causes complicates medical and interventional decisions. Classical plaque rupture/erosion with intracoronary thrombus accounts for a little number of events. On the other side spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) prevalence is unknown but always more recognized and can be considered as the principal cause. [

2] SCAD both pregnancy and non pregnancy related poses a real challenge to interventionalists and therefore conservative management and clinical observation, where possible, is generally recommended. We hereby present the case of a 36 weeks pregnant woman who came to our attention with anterolateral STEMI complicated by cardiogenic shock.

2. Case Presentation

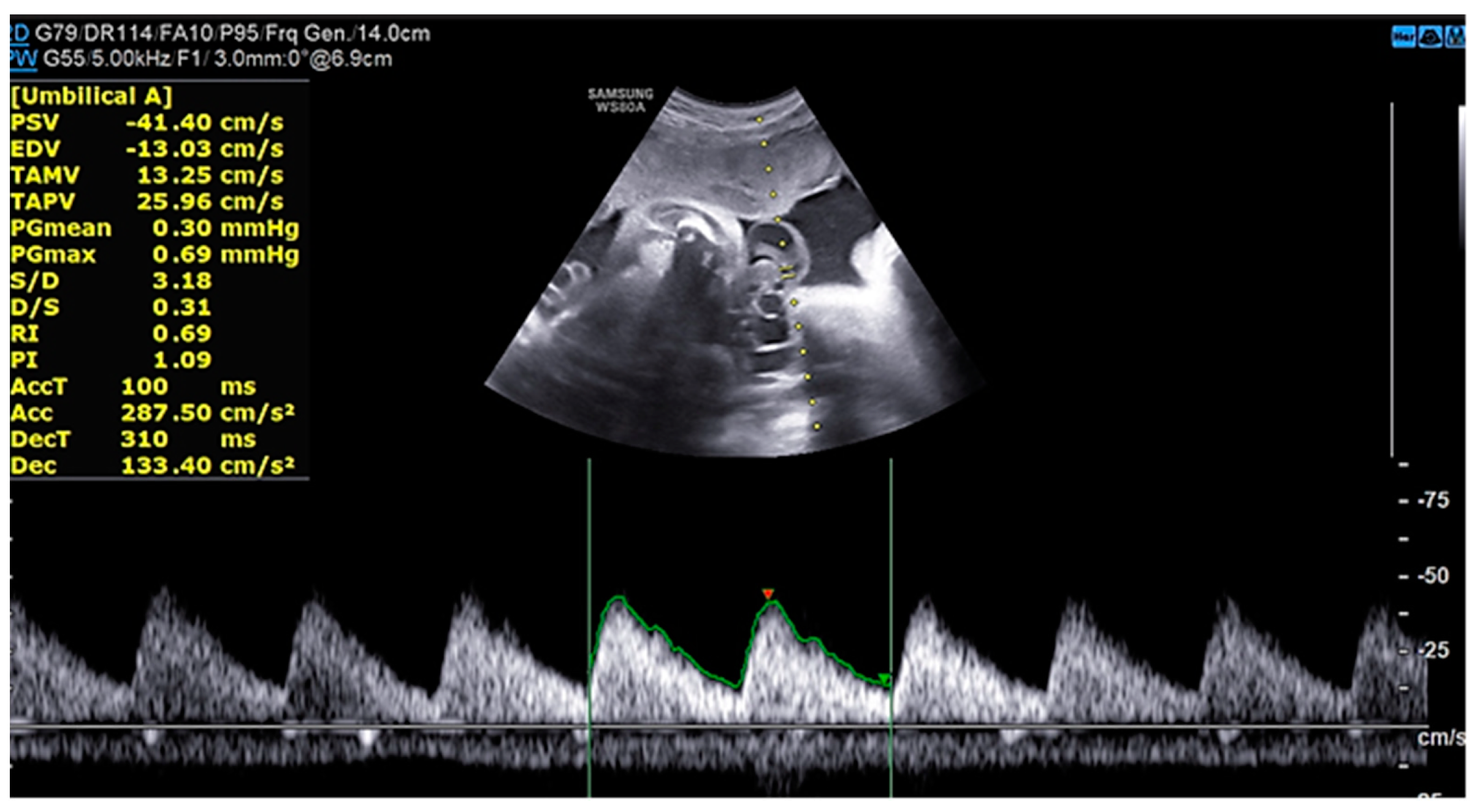

M.G. is a 38 years old woman with two previous pregnancies (G2P2), who was 36 weeks of gestation in her third uneventful pregnancy. All the ultrasound scans (US) performed highlighted a regular fetal growth and normal placental functional markers (umbilical Doppler Pulsatility index),

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. Her only known risk factor is smoking, which she had temporarily quitted.

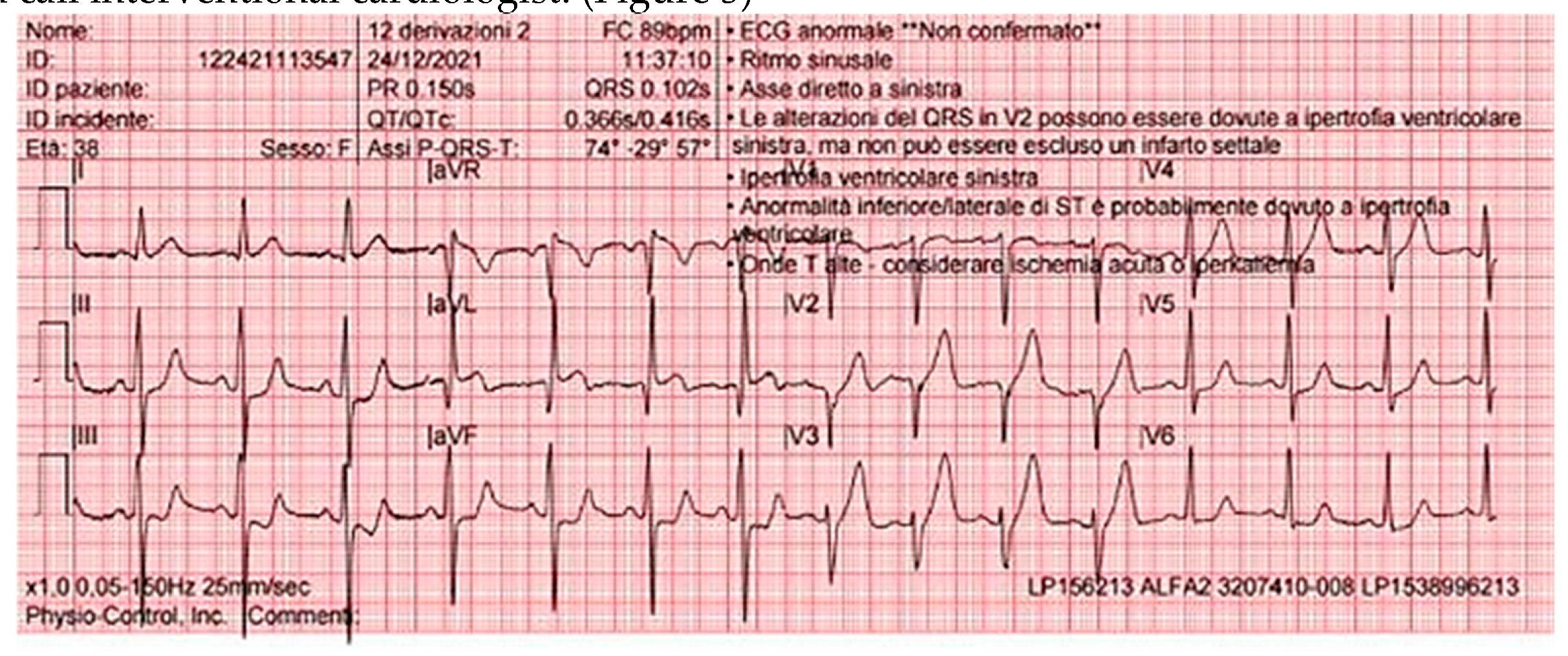

Around 11 am she started experiencing crushing chest pain with profuse sweating, as symptoms continued to increase, she decided to call 911. At the emergency team arrival, the patient was cold and clammy with systolic pressure sitting at around 80 mmHg, a 12 lead electrocardiogram was obtained showing normal sinus rhythm with ST elevation in anterior and lateral leads. The EKG was immediately transmitted to the local CCU which promptly activated the STEMI protocol involving the on call interventional cardiologist. (

Figure 3)

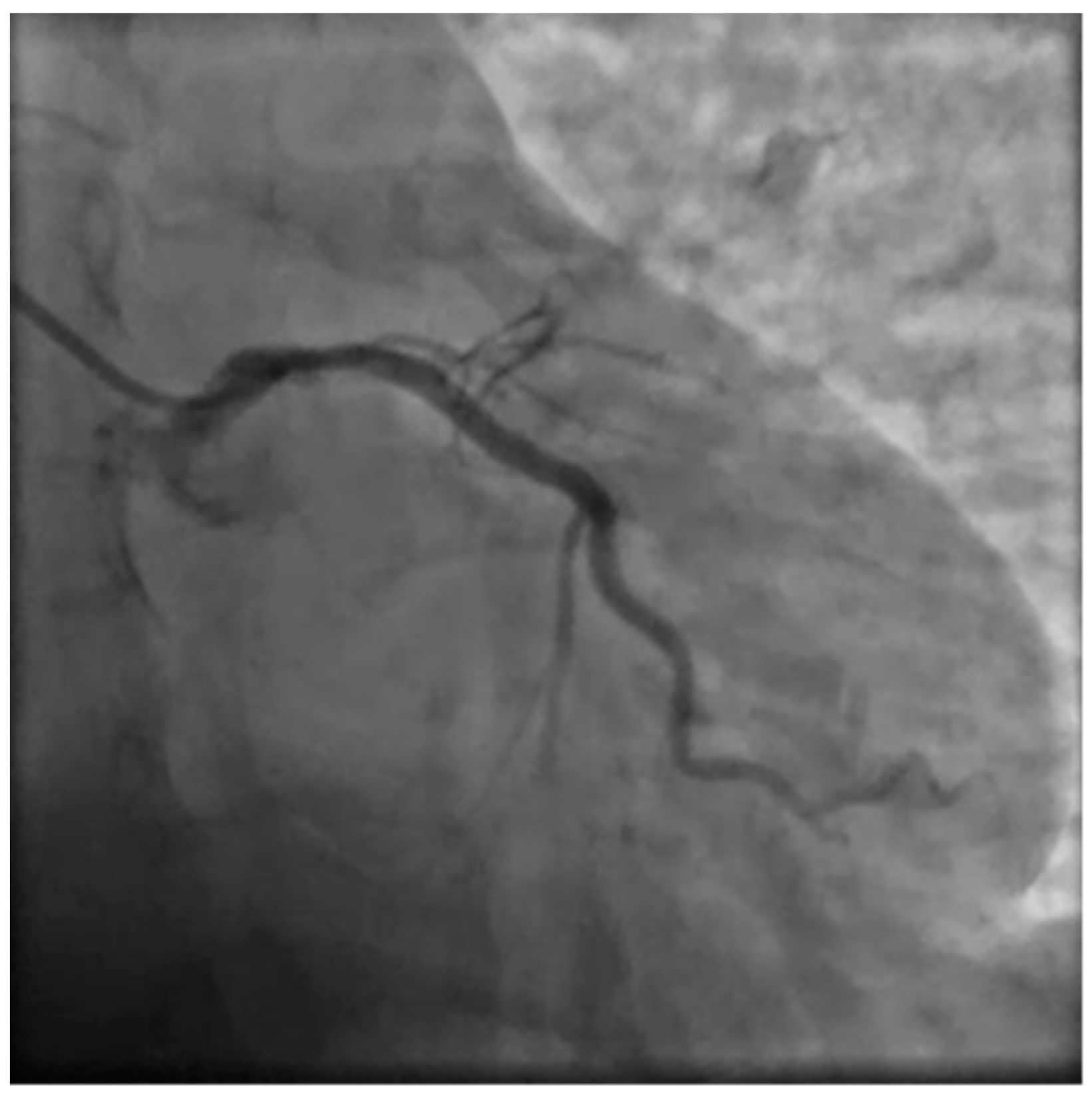

Due to the unusual setting involving a 36 weeks pregnant woman several other specialists were involved in the care process setting up an emergency pregnancy heart team involving cardiologists, gynecologists, anesthesiologists, pediatricians and the radiology specialist. Due to the unstable and acute condition of the woman a decision was quickly made to proceed with an emergency coronary angiography and PCI. A rapid response gynecology team followed the procedure ready to intervene promptly in case of maternal deterioration with unresponsive cardiac arrest. A 6F left radial access was obtained, aiming to be as coaxial as possible, and the left coronary artery angiogram was obtained with a standard 6F JL 3.5 catheter showing LM dissection involving the ostial LAD which showed complete occlusion with TIMI 0 flow.

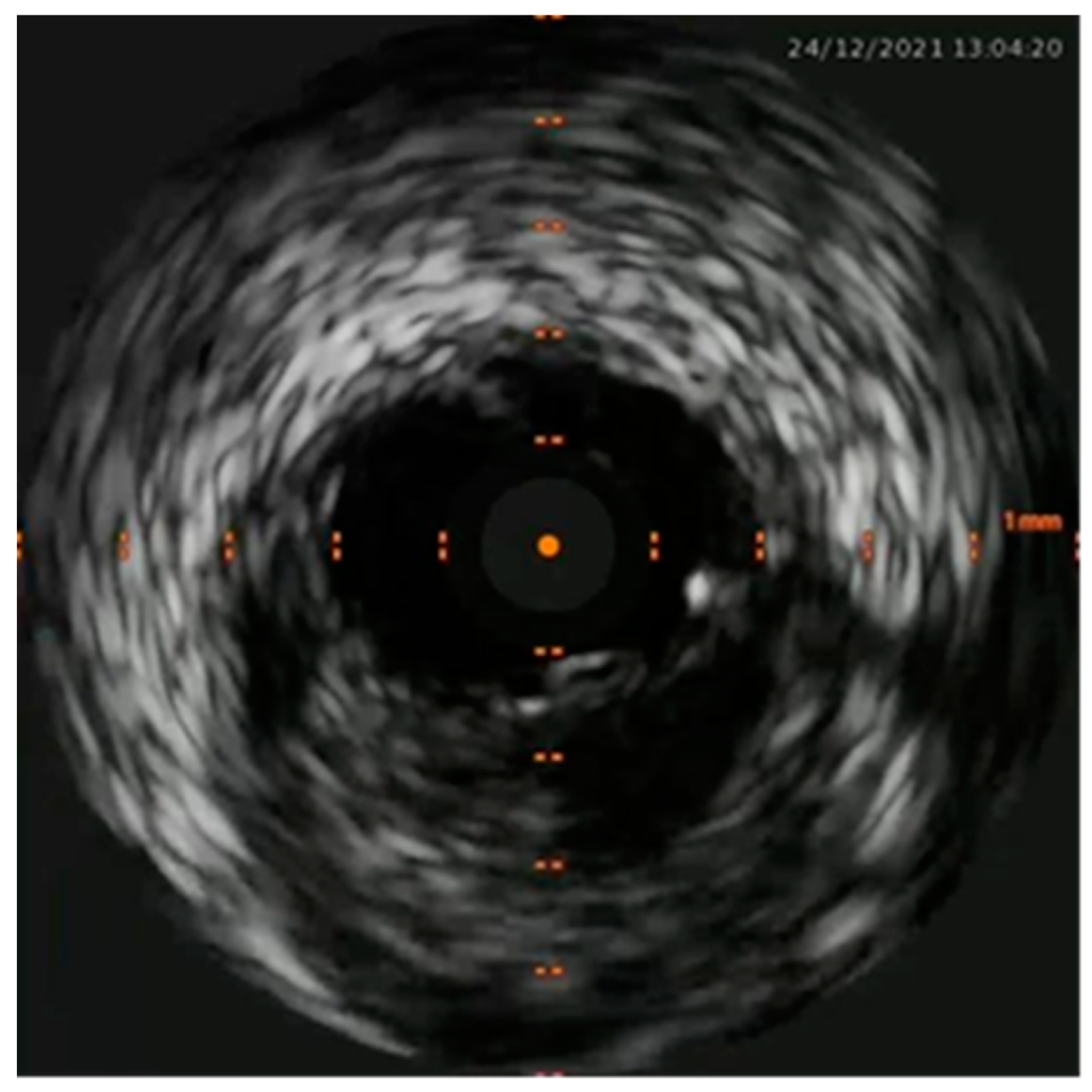

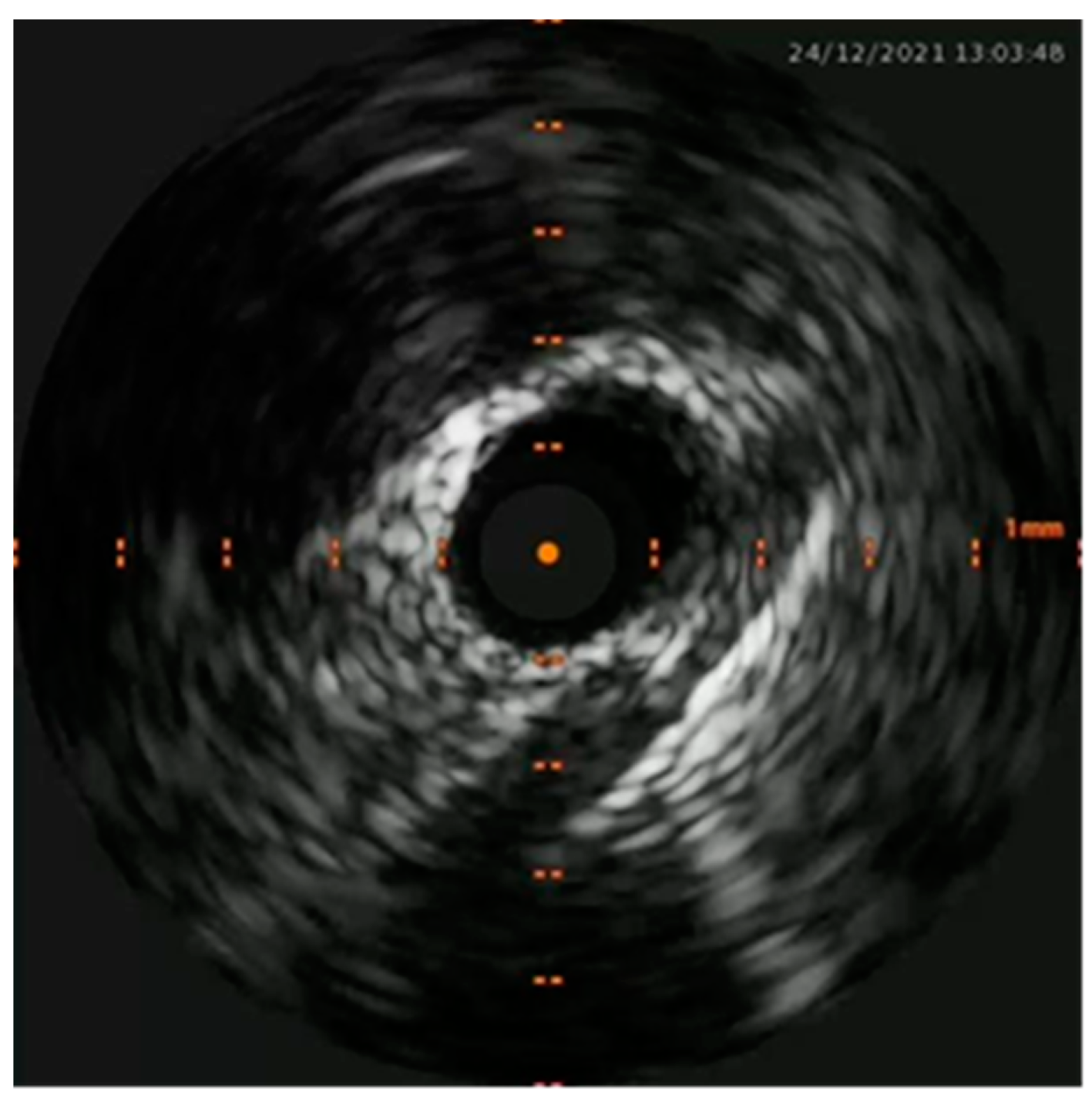

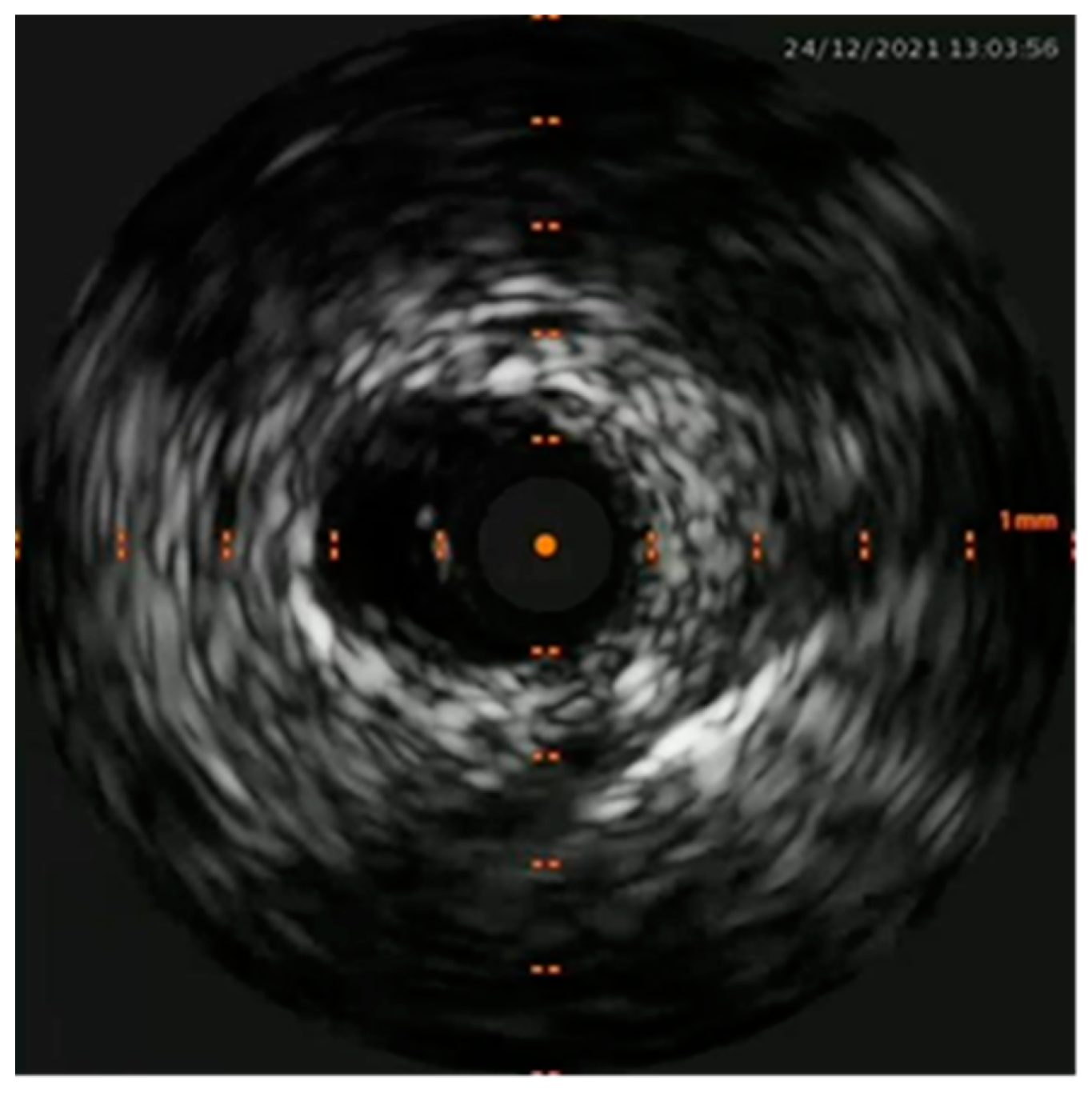

Percutaneous coronary intervention was therefore considered appropriate and a purposely undersized EBU 3.0 6F was selected. A safety wire, Runthrough floppy, was immediately placed on the patent left circumflex artery whilst after failing wiring on the left anterior descending with a Balance Middleweight wire a Sion wire was advanced up to the apical LAD. An IVUS run confirmed distal true lumen wire position showing a short subintimal track without compromise of any major side branch. (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7)

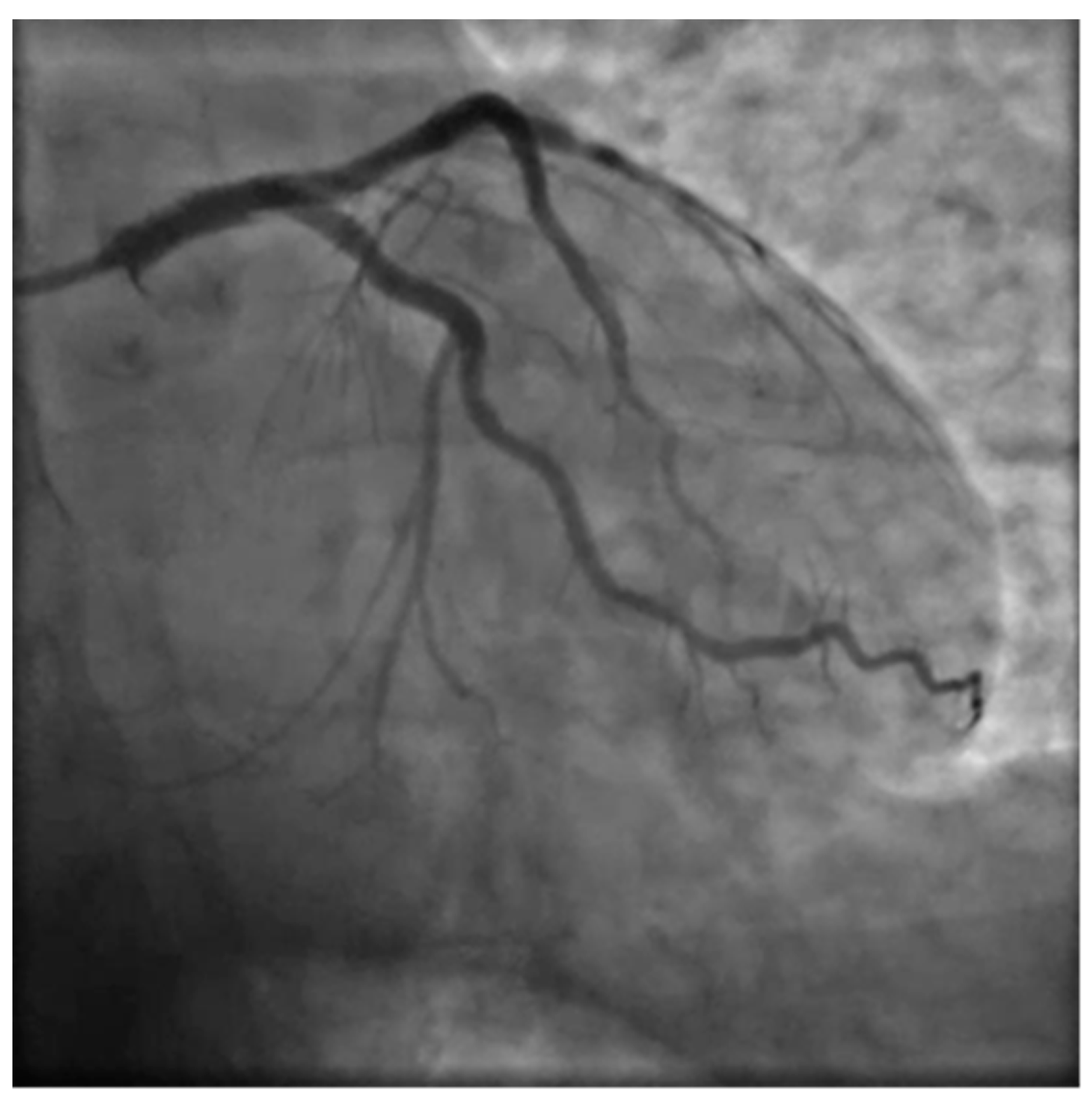

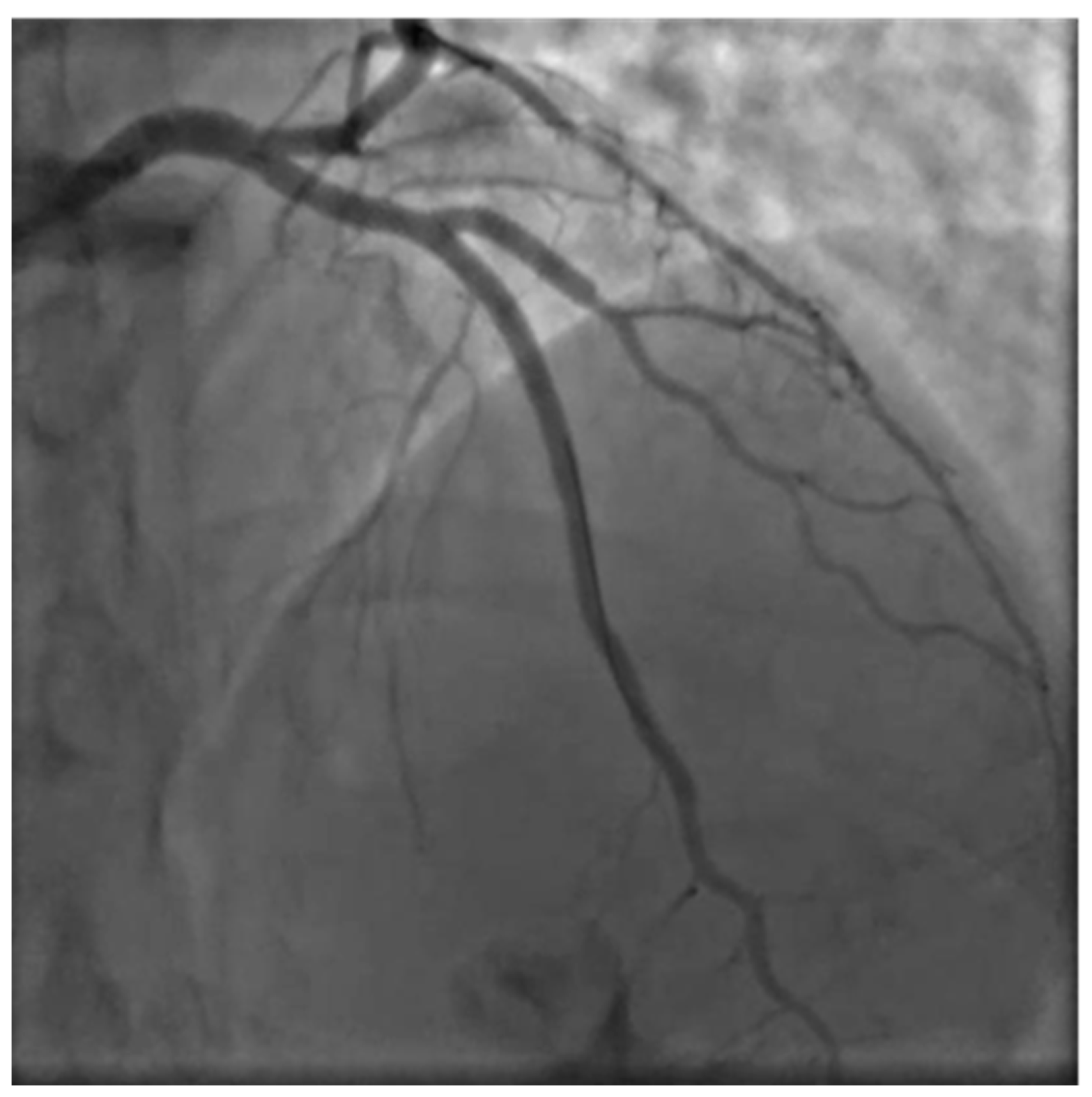

A decision to accept wire position was made and stenting was initiated starting with distal stent placement followed by LM-LAD stenting in order to trap hematoma. Finally stenting of LAD-DG bifurcation was done and LCx ostium was stented too. The final angiographic result was excellent, the ECG showed ST resolution and the patient's hemodynamics rapid improvement. (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9)

At the end of the PCI an ultrasound scan evaluated a normal fetal heart rate, and the patient underwent an emergency cesarean section. A healthy boy (the weight was 3150 g, Apgar 9/10 at the 1st and the 5th minute respectively) was born. Both mother and newborn were in good clinical condition at the hospital discharge.

3. Results

Acute myocardial infarction during pregnancy (pAMI) is a rare event, with an estimated incidence of 1 to 30.000 deliveries. [

1,

2,

3,

4] It represents a real obstetrical emergency with a high rate of fetal and maternal morbidity and mortality. [

5,

6] Obstetricians must focus on gestational age at the time of pAMI and the timing of delivery. Current literature and the American Heart Association recommend an emergency cesarean section within four minutes from maternal heart failure delivering the newborn within one minute. Despite this, there are data regarding successful obstetrical outcomes when the cesarean section was performed fifteen minutes after pAMI. [

7,

8,

9,

10] In our case, the emergency pregnancy heart team discussed about the timing of delivery. Was it reasonable to proceed with an emergency coronary angiography and PCI firstly followed by an emergency cesarean section despite the high risk of maternal death and regardless the operatory block and the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)? [

11,

12] Perinatal asphyxia is characterized by a variable period of global hypoxia-ischemia, followed by reperfusion and reoxygenation, with primary neuronal damage. [

13]. Hypoxemia due to placental insufficiency is characterized by an increase in placental vascular resistance and a secondary fall in umbilical blood flow. The proportion of lesions is inversely related to the functionality of the placenta and can determine a reduction in the transport of oxygen and nutrients to the fetus, as well as an increase in the resistance of the placental blood flow at the level of the maternal and fetal districts.[

14] It has been observed that a reduction in the flow velocity at the end of diastole is evident when at least 30% of the villous vascularization is altered and how the obliteration of more than 50% of the villous vessels is necessary before the detection of alterations in the end-diastolic flow (absent or inverted) of the umbilical artery is evaluated [

14,

15,

16]. These studies highlight fetus’ ability to protect itself from an ischemic insult, through the redistribution of the venous flow towards the vital organs (heart, brain, adrenal glands), also known as brain-sparing effect. Placental blood flow does not change in the initial phase of hypoxia in an uneventful pregnancy, especially after the 34th week of gestation. [

13]. According to this evaluation and international guidelines, the emergency pregnancy heart team decided for maternal hemodynamic stabilization followed by delivery. Both gynecologist and pediatrician were present in the operating theater ready to promptly intervene in case of maternal cardiac arrest.

In this case and as a staple for future clinicians, it should be considered the following positive prognostic factors to guide therapeutic decisions:

- -

a short term interval between maternal acute myocardial infarction and delivery, possibly whit a multidisciplinary team (interventional cardiologist, gynecologist, pediatrician and anesthesiologist) and an intensive care unit to monitor maternal health;

- -

an adequate demonstrated placental function can prevent an acute fetal hypoxia/acidosis.

4. Discussion

Acute myocardial infarction during pregnancy is a rare event with a high risk of fetal-maternal mortality and morbidity. An adverse obstetrical outcome is mainly related to the gap between maternal hemodynamic failure and the emergency cesarean section because of fetal hypoxia and subsequent acidosis. It represents a real clinical and surgical emergency: we recommend, according to literature, to perform an emergency coronary angiography and PCI firstly followed by a cesarean section as soon as possible. Both the mother and the newborn should be monitoring in a high intensive care unit in the first hours after the procedure.

Author Contributions

data curation, M.P., S.T., A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, I.P., I.S., I.L., D.I.C.; writing—review and editing, S.F., C.C., M.A.; supervision, B.C., O.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was obtained.

Conflicts of Interest

All other authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Mohan M. Edupuganti, Vyjayanthi Ganga. Acute myocardial infarction in pregnancy: Current diagnosis and management approaches. Indian Heart Journal 71 (2019) 367e374.

- Marysia S. Tweet ,MD; Jennifer Lewey , MD, MPH; Nathaniel R. Smilowitz, MD et al. Pregnancy-Associated Myocardial Infarction: Prevalence, Causes, and Interventional Management. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:e008687. [CrossRef]

- HE Cohn, E J Sacks, M A Heymann, A M Rudolph. Cardiovascular responses to hypoxemia and acidemia in fetal lambs . Am J Obstet Gynecol . 1974 Nov 15;120(6):817-24.

- Sheldon RE, Peeters LL, Jones MD Jr, Makowski EL, Meschia G. Redistribution of cardiac output and oxygen delivery in the hypoxemic fetal lamb. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979 Dec 15;135(8):1071-8.

- Katz VL, Dotters DJ, Droegemueller W. Perimortem cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 1986; 68: 571-6.

- Lopez-Zeno JA, Carlo WA, O’Grady JP, Fanaroff AA. Infant sur- vival following delayed postmortem cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 1990; 76 (5 Pt 2): 991-2.

- Cardiac Arrest in Pregnancy: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Jeejeebhoy FM, Zelop CM, Lipman S, Carvalho B, Joglar J, Mhyre JM, Katz VL, Lapinsky SE, Einav S, Warnes CA, Page RL, Griffin RE, Jain A, Dainty KN, Arafeh J, Windrim R, Koren G, Callaway CW; American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee, Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation, Council on Cardiovascular Diseases in the Young, and Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2015 Nov 3;132(18):1747-73.

- RCOG, Late Intrauterine fetal death and Stillbirth. Green-top Guideline n° 55, October 2010.

- Boyd R, Teece S. Towards evidence based emergency medicine: best BETs from the Manchester Royal Infirmary. Perimortem caesarean section. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:324 –325.

- MacKenzie IZ, Cooke I. What is a reasonable time from decision-to- delivery by caesarean section? Evidence from 415 deliveries. BJOG. 2002;109:498 –504.

- Strong THJ, Lowe RA. Perimortem cesarean section. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7:489 – 494.

- Boyd R, Teece S. Towards evidence based emergency medicine: best BETs from the Manchester Royal Infirmary. Perimortem caesarean section. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:324 –325.

- Helmy WH, Jolaoso AS, Ifaturoti OO, Afify SA, Jones MH. The decision-to-delivery interval for emergency caesarean section: is 30 minutes a realistic target? BJOG. 2002;109:505–508.

- Hossman KA. Neuronal survival and revival during and after cerebral ischemia. Am J Emerg Med 1983;1:191-7.

- Thompson RS, Trudinger BJ. Doppler waveform pulsatility index and resistance, pressure and flow in the umbilical placental circulation: an investigation using a mathematical model. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1990;16(5):449-58.

- Adamson SL. Arterial pressure, vascular input impedance, and resistance as determinants of pulsatile blood flow in the umbilical artery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999 Jun;84(2):119-25.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).