1. Introduction

Cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) deficiency, also known as classical homocystinuria, is an autosomal recessively inherited metabolic disorder that results in accumulation of homocysteine (Hcy) and methionine (Met) but in contrary depletion of cystathionine and cysteine due to mutations in the

CBS gene. The clinical phenotype can vary widely, ranging from severe multisystemic disease in early childhood to asymptomatic patients diagnosed in adulthood. Major clinical findings include neuropsychiatric signs such as autism, mental retardation and psychosis, skeletal system malformations including osteoporosis, predisposition to thromboembolism and ocular lens dislocation [

1,

2,

3].

Defective enzymatic deficiency of CBS results in alteration of both transsulfuration and enhanced remethylation, so that the main biochemical features are increased plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) and Met concentrations. Measurement of increased tHcy and Met concentrations and decreased enzyme activity in fibroblasts and plasma can be supportive, and a definite diagnosis can be made by detecting biallelic pathogenic variants in the

CBS gene [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Early treatment can lead to a favorable metabolic outcome, and inclusion of CBS deficiency in neonatal screening programs is strongly recommended for a good clinical prognosis [

8,

9]. In case of diagnostic delay and inadequate metabolic control, morbidity and mortality may occur due to multisystemic involvement of the central nervous system, vascular system, and connective tissue [

4].

Homocysteine-induced oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress with apoptosis of endothelial cells, induction of unfolded protein response, and chronic inflammation are the potential underlying mechanisms responsible for clinical symptoms [

10,

11]. Therefore, the main goal of treatment is to lower or normalize plasma homocysteine concentrations, and treatment should be continued throughout life. Cystathionine-β-synthase deficiency is divided into subgroups depending on the response of patients to pyridoxine. In patients who do not respond to pyridoxine, the main therapeutic strategy is protein-restricted medical nutrition therapy used alone or in combination with betaine [

4]. Inborn errors of metabolism (IEM) centers use different protocols for medical nutrition therapy. As there is not a uniform consensus, both low-Met and low-natural protein diets have been used in conjunction with a methionine-free L-amino acid mixture (MFAAM) in patients with CBS deficiency. However, dietary adherence is often poor and can be difficult, especially in late-diagnosed patients with mental involvement [

12,

13]. Betaine is preferred as an add-on therapy in patients whose plasma tHcy levels cannot be maintained within the targeted ranges with medical nutrition therapy. However, it has been reported that betaine intake is associated with various side effects in some patients due to high plasma Met levels [

14]. In conclusion, individualized precision medicine according to patients' clinical and biochemical parameters is recommended instead of a standardized therapeutic regimen to achieve a good metabolic outcome.

In the medical literature, liberalization of the diet according to the phenylalanine content of various foods and unrestricted consumption of fruits and vegetables has been described as a successful treatment option for metabolic control in patients with phenylketonuria (PKU) [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Inspired by the positive results of PKU studies, in this study we aimed to investigate the effects of Met portioning-based medical nutrition therapy with freer consumption of fruits and vegetables compared with strict protein change diets over the metabolic outcome and quality of life.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This prospective clinical trial was conducted between May 2020 and April 2021 at Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty, Department of Pediatric Nutrition and Metabolic Diseases, with pyridoxine non-responsive CBS deficiency patients. The diagnosis of CBS deficiency was defined as a pathogenic biallelic mutation in the CBS gene in patients with positive clinical and biochemical findings consistent with the disease.

Patients were defined as nonresponsive if tHcy fell less than 20%, partially responsive if it fell more than 20% but remained above 50 μmol/L, and fully responsive if tHcy fell below 50 μmol/L [

4].

Patients diagnosed with pyridoxine nonresponsive CBS deficiency were included if; they were receiving protein-restricted medical nutrition therapy based on a gram-protein calculation, monitored regularly, and plasma tHcy samples were collected at the recommended frequency. Patients who did not have molecular confirmation of the diagnosis, who were diagnosed with pyridoxine-responsive or partially responsive CBS deficiency, and who did not receive regular clinical and laboratory monitoring were excluded from the study.

All procedures used were in accordance with the ethical standards of the local ethics committee of Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty (07/04/2021-69864) and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. All parents of patients included in this study gave informed consent.

2.2. Details of Dietary Interventions and Switching Process to Methionine Portioning

The study period was divided into two periods. In period 1 (May 2020-October 2020), medical nutrition therapy consisted of MFAAM and natural protein arranged according to a "gram protein exchange list." All foods were weighed. In period 2 (November 2020-April 2021), patients continued to receive MFAAM, but natural protein exchange lists were switched according to a "Met portioning exchange list" in which 25 mg of methionine was considered as one portion. Foods that contained less than 0.005 g of methionine per 100 g of the food were accepted as exchange-free foods and were allowed to be consumed liberally without calculating the Met content. The other foods were weighed by the patients according to the Met portioning list. The methionine and protein exchange lists were calculated using the United State Department of Agriculture (USDA) database [

20]. A comparison of the amounts of some fruits and vegetables according to the Met portioning list and gram protein exchange list is shown in

Table 1.

Table 2 provides a list of the exchange free foods and a comparison of their amounts according to the Met Portioning List and the Gram Protein Exchange List.

At the time of switching to period 2, patients and their caregivers were called to the hospital and nutrition education was provided. For those individuals who were unable to attend the face- to-face meetings, online education was provided via WhatsApp or Zoom. After the patient's education was completed, medical nutrition therapy based on gram protein calculation was switched to medical nutrition therapy based on methionine portioning.

In both periods, patients' medical nutrition therapy was arranged according to the plasma tHcy levels, patients' age, body weight, and food records. The principles of follow-up, including the target plasma tHcy levels and the recommended frequency of sampling, were not changed during the two periods.

In this study, the clinical and biochemical data of the patients were reviewed and the following items were recorded for both periods: current age, age at diagnosis, sex, phenotypic characteristics, CBS gene molecular analysis, anthropometric characteristics (height, body weight, and body mass index), medical and nutritional treatments they received. The energy, total protein, and methionine amounts of the dietary therapy in both periods, dietary compliance and adherence, total energy, protein, and methionine intakes of the 3-day food consumption records were recorded and analyzed using the Nutrition Information System (BeBIS 8.0). Plasma tHcy levels, dose of betaine treatment, and percentage of achievement of good metabolic control according to the target ranges for tHcy in the CBS deficiency guideline (4) were compared between the two periods.

2.3. Assessment of Dietary Compliance

At the end of the study period, a questionnaire was conducted on the effects of the new dietary approach. A total of six questions (multiple-choice or short-answer) were asked:

Did the new Met exchange system provide ease of application according to the diet you applied before?

Did it provide you convenience in terms of food variety?

Has the frequency of consumption of prohibited foods decreased?

Did the new exchange system cause more fruit and vegetable consumption?

How did the new exchange system change your dietary compliance at school/work?

Would you like to continue with the new exchange system?

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 26.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables are presented as median (minimum or maximum) or mean ±standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as numbers or percentages. Normal distribution of the data was evaluated with a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The analysis of normally distributed continuous variables in two dependent pairs was performed with the paired samples t-test, while the Mc-Nemar test was used for the analysis of categorical variables used for comparison of groups where appropriate. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Ten patients were included in the study. Five patients (50%) were female and five (50%) were male. The mean age of the patients was 15.8 ± 9.29 years, and the mean follow-up time after the diagnosis of CBS deficiency was 9.25 ± 7.33 years. Nine patients (90%) exhibited a clinical feature relevant to CBS deficiency. The only asymptomatic patient was diagnosed by newborn screening after the diagnosis of CBS deficiency in the first sibling of the family. Patient demographics and characteristics are shown in

Table 3.

3.1. Comparison of anthropometric measurements and components of medical nutrition therapy

Switching to the Met portion exchange list did not result in a statistically significant difference in patients' height z-score, body weight z-score, and body mass index (p=0.085, p=0.522, and p=0.242, respectively). In period 1, all patients received a low-protein diet in combination with MFAAM. MFAAM amount and natural protein intake were not statistically different in period 2 (p=0.873 and p=0.284, respectively). Data on anthropometric measurements and medical nutrition therapy components are shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

3.2. Assessment of metabolic outcome after switching to the Met portioning exchange list

In period 1, plasma tHcy levels below 100 μmol/L were measured in all patients on betaine and medical nutrition therapy. Since switching to the Met portion exchange list did not result in a statistically significant difference in patients' plasma tHcy levels (p=0.250), dietary relaxation in period 2 was not considered to have a negative effect on metabolic outcome. Moreover, the daily betaine dose of patients was significantly reduced in the second period (p=0.017). Betaine treatment was discontinued in four patients (40%) because metabolic control could be achieved by diet alone. Data comparing plasma tHcy levels and betaine doses in both periods are shown in

Table 5.

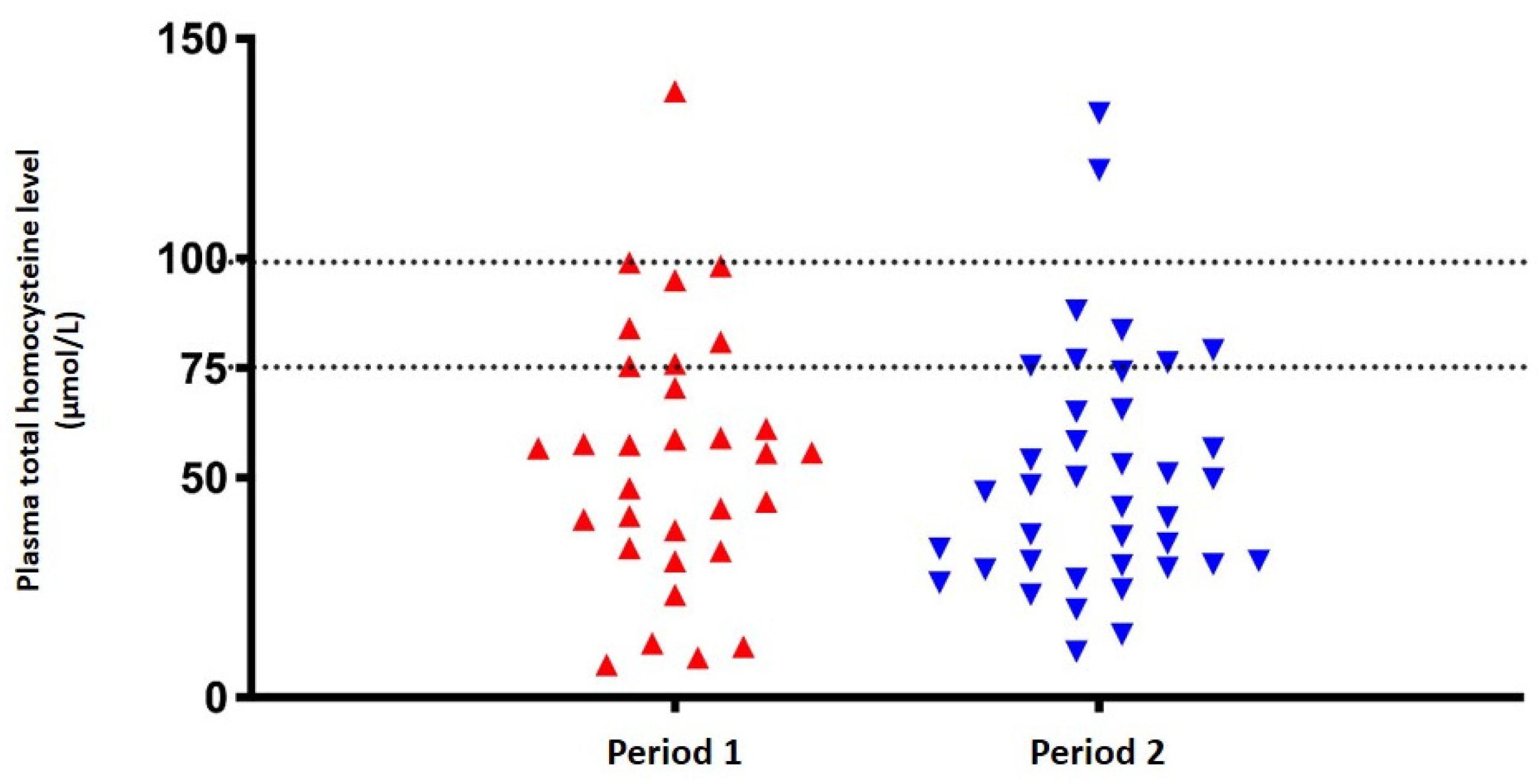

Considering the cutoff value of the target tHcy level as below 75 μmol/L, six patients (60%) were found to be metabolically stable in period 1. After switching to the Met portion exchange list, nine patients (90%) were determined to have plasma tHcy levels below 75 μmol/L, but no statistically significant difference was found (p=0.375). The distribution of patients' plasma tHcy levels according to two different tHcy cut-off values (< 75 and < 100 μmol/L) in both two periods is shown in

Figure 1.

3.3. Efficacy of Met portioning exchange list on dietary compliance

Nine patients participated in the survey, which assessed the impact of switching to a new dietary approach based on the Met portion exchange list on dietary compliance. According to the results of the survey, all patients indicated that this new dietary approach was easier to implement, increased the variety of foods, and helped prevent the consumption of prohibited foods. Six patients (66.7%) reported consumption of more fruits and vegetables, and seven patients (77.7%) reported better adherence to the diet in the second period at school or work. All nine patients planned to continue with the new dietary approach. Statistical differences were found in all survey questions; data are shown in

Table 6.

4. Discussion

In the literature, liberalization of the diet according to the phenylalanine content of various foods and unrestricted consumption of fruits and vegetables has been described as a successful treatment option for metabolic control in PKU patients. Inspired by the positive results of PKU studies, we aimed to use a similar model based on methionine portioning in this study. A simplified and feasible diet, mainly rearranged according to Met portioning exchange lists and allowing unrestricted intake of fruits and vegetables containing less than 5 mg/100 g of Met, was used to treat pyridoxine nonresponsive CBS deficiency patients who were previously receiving low-protein diet based on gram-protein exchange lists in which all foods were weighed. We demonstrated that Met portioning-based medical nutrition therapy and nonweighted inclusion of all fruits and vegetables in the exchange-free food list had no adverse effects on the control of plasma tHcy levels with respect to metabolic outcome. Switching to Met portioning resulted in a significant reduction in patients' daily betaine dose, and 40% of patients discontinued betaine because metabolic control could be achieved with dietary therapy alone. The results of the questionnaires at the end of the study indicated that this new nutritional approach significantly increased patients' adherence to therapy, and all patients preferred to continue with this modality. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to show that diet liberalization by unrestricted consumption of fruits and vegetables with a Met content of no more than 5 mg/100 g and, in particular, this simplified dietary model did not affect long-term control of blood Hcy levels.

The main goal of treatment is to normalize or reduce plasma tHcy levels in patients with CBS deficiency; in individuals who do not respond to pyridoxine, treatment consists mainly of medical nutrition therapy and betaine [

4]. To date, dietary approaches to CBS deficiency have been studied in the medical literature. A large sample-size study involving 29 IEM centers and 181 patients with CBS deficiency compared current dietary practices. Fifteen of the 29 centers prescribed a diet based primarily on Met analysis of foods. However, almost all of these centers used a combination of Met and natural protein analysis, including grams of protein exchanges or calculated the protein content of all foods consumed. There was no free food list and metabolic outcome data were not available [

12]. Compared with our study, the results of our study suggest that metabolic control can be achieved by using a Met portioning list as a natural protein source. In addition, liberalization of the diet by a free food list appeared to be safe and had no negative effects on metabolic control.

Another point of controversy in treatment is the use of betaine in CBS deficiency. Most IEM centers use betaine as an add-on treatment to lower plasma tHcy levels to the target range, as recent studies have shown betaine to have a safe spectrum. A study of 130 individuals found that betaine use was associated with diarrhea and visual disturbances, but these resolved without sequelae. Plasma Met levels exceeded 1000 μmol/L in only one patient, but he had no signs of cerebral edema [

21]. In another study, 277 adverse effects were reported by patients with different etiologies leading to homocystinuria. Only three adverse effects were associated with betaine. Two of them suffered from bad taste and headache, and one from interstitial lung disease. However, the patient who developed interstitial lung disease also had cobalamin C deficiency, and these respiratory problems may also have been due to the underlying disease [

22]. Despite these studies supporting the safety of betaine, several patients have been reported to develop hypermethioninemia greater than 1000 μmol/L and clinical findings consistent with increased intracranial pressure and cerebral edema on magnetic resonance imaging after the fourth week of betaine administration have been reported [

23,

24,

25]. In addition to safety concerns, murine studies have shown that medical nutrition therapy is superior to betaine in terms of metabolic control, and the efficacy of betaine in lowering plasma tHcy levels has been shown to decrease over time with long-term betaine use [

26,

27]. According to the results of our study, metabolic control can be achieved in 4 patients by dietary treatment alone, and betaine treatment was discontinued by switching to Met portioning. Continuation of treatment as monotherapy was evaluated in favor of patients in terms of both convenience and safety.

Cystathionine-β-synthase deficiency has been reported to be challenging for patients and caregivers in terms of dietary adherence and quality of life. Because CBS deficiency is not covered by an expanded newborn screening program in most countries, patients are usually diagnosed late, and patients who did not have dietary restriction until diagnosis have difficulty adhering to treatment with Met and natural low-protein diet, leading to quality of life problems [

28,

29]. Irregular or incomplete intake of MFAAM, the complexity of dietary regimens, the need to weigh all foods before consumption, and socioeconomic factors, including family characteristics, family educational level, and patient ownership, have been described as complicating dietary adherence in patients with CBS deficiency [

13,

30]. In a study that addressed dietary adherence problems in patients with CBS deficiency, consumption of MFAAM was considered a problem in 74% of patients. It was found that 81% of patients had difficulty adapting a low-protein diet as well. In addition, 73% of patients reported that they had difficulty weighing foods [

13]. In our study, the increase in the variety of foods that patients could consume without weighing led to a simplification of their diet in terms of its impact on their school, work, and social lives. This resulted in 77.7% of patients better adhering to their diet, and all patients preferred to continue with this new diet.

Our study had some limitations. It was conducted with a small sample size, and data were reported from a relatively short follow-up period.

5. Conclusions

Our data suggest that methionine portioning based medical nutrition therapy with relaxed fruit and vegetable consumption seems to be a good and safe option to maintain good metabolic outcome and dietary compliance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.U.; C.A.-Z.; E.K.; T.Z.; methodology, E.U.; M.A.; C.A.-Z.; E.K.; M.S.C.; T.Z.; formal analysis, M.S.C.; investigation, E.U.; M.A.; M.S.C.; T.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, E.U.; writing—review and editing, T.Z.; supervision, C.A.-Z.; T.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty (protocol code 69864;07.04.2021) of approval

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the parents of the patients and patients when available to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [T.Z.], upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Sacharow, S.J.; Picker, J.D.; Levy, H.L. Homocystinuria Caused by Cystathionine Beta-Synthase Deficiency. In GeneReviews® [Internet]. Adam, M.P.; Mirzaa, G.M.; Pagon, R.A.; Wallace, S.E.; Bean, L.J.H.; Gripp, K.W.; Amemiya, A., Eds.; Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2023. 2004 Jan 15 [updated 2017 May 18].

- Karaca, M.; Hismi, B.; Ozgul, R.K.; Karaca, S.; Yilmaz, D.Y.; Coskun, T.; Sivri, H.S.; Tokatli, A.; Dursun, A. High prevalence of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) as presentation of cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency in childhood: molecular and clinical findings of Turkish probands. Gene 2014, 534, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovby, F.; Gaustadnes, M.; Mudd, S.H. A revisit to the natural history of homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab 2010, 99, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.A.; Kožich, V.; Santra, S.; Andria, G.; Ben-Omran, T.I.; Chakrapani, A.B.; Crushell, E.; Henderson, M.J.; Hochuli, M.; Huemer, M.; Janssen, M.C.; Maillot, F.; Mayne, P.D.; McNulty, J.; Morrison, T.M.; Ogier, H.; O'Sullivan, S.; Pavlíková, M.; de Almeida, I.T.; Terry, A.; Yap, S.; Blom, H.J.; Chapman, K.A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis 2017, 40, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaide, P.; Krijt, J.; Ruiz-Sala, P.; Ješina, P.; Ugarte, M.; Kožich, V.; Merinero, B. Enzymatic diagnosis of homocystinuria by determination of cystathionine-ß-synthase activity in plasma using LC-MS/MS. Clin Chim Acta 2015, 438, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bártl, J.; Chrastina, P.; Krijt, J.; Hodík, J.; Pešková, K.; Kožich, V. Simultaneous determination of cystathionine, total homocysteine, and methionine in dried blood spots by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry and its utility for the management of patients with homocystinuria. Clin Chim Acta 2014, 437, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Mistretta, B.; Elsea, S.; Sun, Q. Simultaneous determination of plasma total homocysteine and methionine by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chim Acta 2017, 464, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huemer, M.; Kožich, V.; Rinaldo, P.; Baumgartner, M.R.; Merinero, B.; Pasquini, E.; Ribes, A.; Blom, H.J. Newborn screening for homocystinurias and methylation disorders: systematic review and proposed guidelines. J Inherit Metab Dis 2015, 38, 1007–10019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, R.; Chrastina, P.; Pavlíková, M.; Gouveia, S.; Ribes, A.; Kölker, S.; Blom, H.J.; Baumgartner, M.R.; Bártl, J.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Gleich, F.; Morris, A.A.; Kožich, V.; Huemer, M.; individual contributors of the European Network and Registry for Homocystinurias and Methylation Defects (E-HOD); Barić, I.; Ben-Omran, T.; Blasco-Alonso, J.; Bueno Delgado, M.A.; Carducci, C.; Cassanello, M.; Cerone, R.; Couce, M.L.; Crushell, E.; Delgado Pecellin, C.; Dulin, E.; Espada, M.; Ferino, G.; Fingerhut, R.; Garcia Jimenez, I.; Gonzalez Gallego, I.; González-Irazabal, Y.; Gramer, G.; Juan Fita, M.J.; Karg, E.; Klein, J.; Konstantopoulou, V.; la Marca, G.; Leão Teles, E.; Leuzzi, V.; Lilliu, F.; Lopez, R.M.; Lund, A.M.; Mayne, P.; Meavilla, S.; Moat, S.J.; Okun, J.G.; Pasquini, E.; Pedron-Giner, C.C.; Racz, G.Z.; Ruiz Gomez, M.A.; Vilarinho, L.; Yahyaoui, R.; Zerjav Tansek, M.; Zetterström, R.H.; Zeyda, M. Newborn screening for homocystinurias: Recent recommendations versus current practice. J Inherit Metab Dis 2019, 42, 128–139.

- Lai, W.K.; Kan, M.Y. Homocysteine-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction. Ann Nutr Metab 2015, 67, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perła-Kaján, J.; Twardowski, T.; Jakubowski, H. Mechanisms of homocysteine toxicity in humans. Amino Acids 2007, 32, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, S.; Almeida, M.F.; Carbasius Weber, E.; Champion, H.; Chan, H.; Daly, A.; Dixon, M.; Dokoupil, K.; Egli, D.; Evans, S.; Eyskens, F.; Faria, A.; Ferguson, C.; Hallam, P.; Heddrich-Ellerbrok, M.; Jacobs, J.; Jankowski, C.; Lachmann, R.; Lilje, R.; Link, R.; Lowry, S.; Luyten, K.; MacDonald, A.; Maritz, C.; Martins, E.; Meyer, U.; Müller, E.; Murphy, E.; Robertson, L.V.; Rocha, J.C.; Saruggia, I.; Schick, P.; Stafford, J.; Stoelen, L.; Terry, A.; Thom, R.; van den Hurk, T.; van Rijn, M.; van Teefelen-Heithoff, A.; Webster, D.; White, F.J.; Wildgoose, J.; Zweers, H. Dietary practices in pyridoxine non-responsive homocystinuria: a European survey. Mol Genet Metab 2013, 110, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, T.; Bösch, F.; Landolt, M.A.; Kožich, V.; Huemer, M.; Morris, A.A.M. Homocystinuria patient and caregiver survey: experiences of diagnosis and patient satisfaction. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2021, 16, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T.; Sharma, G.S.; Singh, L.R. Homocystinuria: Therapeutic approach. Clin Chim Acta 2016, 458, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.; Jacobs, P.; Fingerhut, R.; Torresani, T.; Thöny, B.; Blau, N.; Baumgartner, M.R.; Rohrbach, M. Positive effect of a simplified diet on blood phenylalanine control in different phenylketonuria variants, characterized by newborn BH4 loading test and PAH analysis. Mol Genet Metab 2012, 106, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, M.I.; Adam, S.; Adams, S.; Allen, H.; Ashmore, C.; Bailey, S.; Cochrane, B.; Dale, C.; Daly, A.; De Sousa, G.; Donald, S.; Dunlop, C.; Ellerton, C.; Evans, S.; Firman, S.; Ford, S.; Freedman, F.; French, M.; Gaff, L.; Gribben, J.; Grimsley, A.; Herlihy, I.; Hill, M.; Khan, F.; McStravick, N.; Millington, C.; Moran, N.; Newby, C.; Nguyen, P.; Purves, J.; Pinto, A.; Rocha, J.C.; Skeath, R.; Skelton, A.; Tapley, S.; Woodall, A.; Young, C.; MacDonald, A. Suitability and Allocation of Protein-Containing Foods According to Protein Tolerance in PKU: A 2022 UK National Consensus. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, C.; Mütze, U.; Schulz, S.; Thiele, A.G.; Ceglarek, U.; Thiery, J.; Mueller, A.S.; Kiess, W.; Beblo, S. Unrestricted fruits and vegetables in the PKU diet: a 1-year follow-up. Eur J Clin Nutr 2014, 68, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, C.; Mütze, U.; Weigel, J.F.; Ceglarek, U.; Thiery, J.; Kiess, W.; Beblo, S. Unrestricted consumption of fruits and vegetables in phenylketonuria: no major impact on metabolic control. Eur J Clin Nutr 2012, 66, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, A.; Rylance, G.; Davies, P.; Asplin, D.; Hall, S.K.; Booth, I.W. Free use of fruits and vegetables in phenylketonuria. J Inherit Metab Dis 2003, 26, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA Food Data Central. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/index.html(2022).

- Mütze, U.; Gleich, F.; Garbade, S.F.; Plisson, C.; Aldámiz-Echevarría, L.; Arrieta, F.; Ballhausen, D.; Zielonka, M.; Petković Ramadža, D.; Baumgartner, M.R.; Cano, A.; García Jiménez, M.C.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Ješina, P.; Blom, H.J.; Couce, M.L.; Meavilla Olivas, S.; Mention, K.; Mochel, F.; Morris, A.A.M.; Mundy, H.; Redonnet-Vernhet, I.; Santra, S.; Schiff, M.; Servais, A.; Vitoria, I.; Huemer, M.; Kožich, V.; Kölker, S. Postauthorization safety study of betaine anhydrous. J Inherit Metab Dis 2022, 45, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valayannopoulos, V.; Schiff, M.; Guffon, N.; Nadjar, Y.; García-Cazorla, A.; Martinez-Pardo Casanova, M.; Cano, A.; Couce, M.L.; Dalmau, J.; Peña-Quintana, L.; Rigalleau, V.; Touati, G.; Aldamiz-Echevarria, L.; Cathebras, P.; Eyer, D.; Brunet, D.; Damaj, L.; Dobbelaere, D.; Gay, C.; Hiéronimus, S.; Levrat, V.; Maillot, F. Betaine anhydrous in homocystinuria: results from the RoCH registry. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2019, 14, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, A.M.; Hajipour, L.; Gholkar, A.; Fernandes, H.; Ramesh, V.; Morris, A.A. Cerebral edema associated with betaine treatment in classical homocystinuria. J Pediatr 2004, 144, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghmai, R.; Kashani, A.H.; Geraghty, M.T.; Okoh, J.; Pomper, M.; Tangerman, A.; Wagner, C.; Stabler, S.P.; Allen, R.H.; Mudd, S.H.; Braverman, N. Progressive cerebral edema associated with high methionine levels and betaine therapy in a patient with cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) deficiency. Am J Med Genet 2002, 108, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truitt, C.; Hoff, W.D.; Deole, R. Health Functionalities of Betaine in Patients With Homocystinuria. Front Nutr 2021, 8, 690359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Wang, L.; Kruger, W.D. Betaine supplementation is less effective than methionine restriction in correcting phenotypes of CBS deficient mice. J Inherit Metab Dis 2016, 39, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclean, K.N.; Jiang, H.; Greiner, L.S.; Allen, R.H.; Stabler, S.P. Long-term betaine therapy in a murine model of cystathionine beta-synthase deficient homocystinuria: decreased efficacy over time reveals a significant threshold effect between elevated homocysteine and thrombotic risk. Mol Genet Metab 2012, 105, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kožich, V.; Sokolová, J.; Morris, A.A.M.; Pavlíková, M.; Gleich, F.; Kölker, S.; Krijt, J.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Baumgartner, M.R.; Blom, H.J.; Huemer, M.; E-HOD, consortium. Cystathionine β-synthase deficiency in the E-HOD registry-part I: pyridoxine responsiveness as a determinant of biochemical and clinical phenotype at diagnosis. J Inherit Metab Dis 2021, 44, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrard, A.; Dawson, C. Homocystinuria diagnosis and management: it is not all classical. J Clin Pathol 2022,jclinpath-2021-208029. Epub ahead of print.

- MaCdonald, A.; van Rijn, M.; Feillet, F.; Lund, A.M.; Bernstein, L.; Bosch, A.M.; Gizewska, M.; van Spronsen, F.J. Adherence issues in inherited metabolic disorders treated by low natural protein diets. Ann Nutr Metab 2012, 61, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).