1. Introduction

In India, livestock segment acts as a beacon of hope for large proportion of small and In India, the livestock segment acts as a beacon of hope for a large proportion of small and marginal farmers. Sheep and goat rearing activities are important livelihood options, especially in areas where crop and dairy farming face challenges. The total sheep population in India is 74.26 million as per the 2019 livestock census, and it increased by 14.1% over the previous census of 2012. The rearing of small ruminants is limited in terms of constraints associated with health, feed resources, and marketing. In particular, livestock, including sheep, suffers from a 36% shortage of green fodder, and estimates suggest that the deficit of green fodder and dry fodder in 2025 likely to be 65% and 25% respectively (1-4). This situation drives the sheep farmers to look for alternative feed resources. The usage of unconventional feed resources has increased in livestock farming over the years due to lack of grazing lands and poor rainfall, which resulted in an acute shortage of feed and fodder. On account of feed costs and the food and feed crisis, by-products offer advantages to farmers. The by-products are generally cheaper than conventional feedstuffs. Therefore, farmers can include by-products in animal diets if the by-products support acceptable animal performance (5, 6). As a result, farmers save money by using a less expensive by-product. The residues from crops and by-products are being used in livestock feeding on account of their availability and cost on comparing to their nutritional characters such as, high lignin and poor carbohydrates and protein (7, 8).

One of the emerging industrial by-products is CGT (Cotton Gin Trash) from cotton yarn spinning industries. Across the globe, cotton cultivated area accounts for 32.10 million hectares and production accounts for 258 million bales (one bale is 170 kg) in the years 2020–21 (9). In the case of India, the area under cotton cultivation was 121 lakh hectares with a productivity of 445 lintin kg/hectare and the overall production of cotton was 362 lakh bales during 2020–21 (10). Out of this production, 288 lakh bales of cotton were used by textile mills in India during 2020-21.

During the process of separating cotton fibers from cotton seed and spinning, one such by-product is the CGT. Thus it is a by-product in cotton value chain industries particularly at ginning and spinning process along with cottonseed, cottonseed meal, and cottonseed hulls. The majority of the cotton gin waste was disposed of by spreading it on the ground, composting it, feeding it to animals, placing it in landfills, burning it, turning it into energy, creating pellets for stove fuel, utilising it as building materials, and using it as insulation (12). Because of its origin from plants and its source of protein, fat, and fibre, the CGT has the potential to be included in livestock diets as an alternative feed (13), and it is being utilised to meet the energy and protein requirements of sheep as it is used in many parts of the world (14). CGT is a complex mixture of woody fragments of cotton bolls, stalks, knotted cotton fibre residues, mulched leaves, soil, and dust particles (15). Although CGT is low in protein and energy content, it is a source of physically effective fiber and has the potential to be a more economical option for sheep farmers than traditional roughage (16). However, the nutrient composition of cotton gin trash also varied widely (17). CGT's nutritive value is almost comparable with that of other used roughage sources. The availability of CGT in selective parts of Tamil Nadu state of India, drives the farmers to take advantage and use it as feed material in Mecheri sheep breeding tracts in Tamil Nadu. Cotton consumption by textile factories in India is highest in Tamil Nadu; hence, waste output is also significant. Tamil Nadu generates cotton gin waste in the range of 250 to 995 lakh kg per year (18). Farmers rearing the Mehceri breed of sheep in Karur and Tirupur districts are using CGT as a roughage supplement feed for their sheep, mainly during forage shortages in the summer months. Since there is abundant availability of CGT due to the greater number of spinning and ginning industries that are predominantly located in Karur and Tirupur districts (18, 19), Previously, as a waste product, the CGT was often of no cost to purchase other than the costs associated with transportation and hauling. But now it is being sold at a rate of INR (Indian National Rupees) 8.00 to 20.00 per kg (one USD = INR 82) since the demand is increasing among the sheep farmers day by day. Only a few reports are available in India on utilising these cotton gins as a feed source for sheep. Further, the inclusion level varies with the farmers in and around the Mecheri sheep breeding tract. Field observation suggested wide variation in dependence on gin as roughage sources across sheep farming households. There have been limited information on its use as feed in small ruminant production, limiting its full potential as a feed resource. To provide base data on farmers using CGT, their feeding practice and factors driving the farmers to choose CGT as primary source of roughage needs to identify for future planning on usage of CGT in sheep feeding. This will be helpful to understand the status quo of CGT feeding and may also have potential application in selection of target population to promote CGT or similar non-conventional feed resources in animal feeding.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of study area

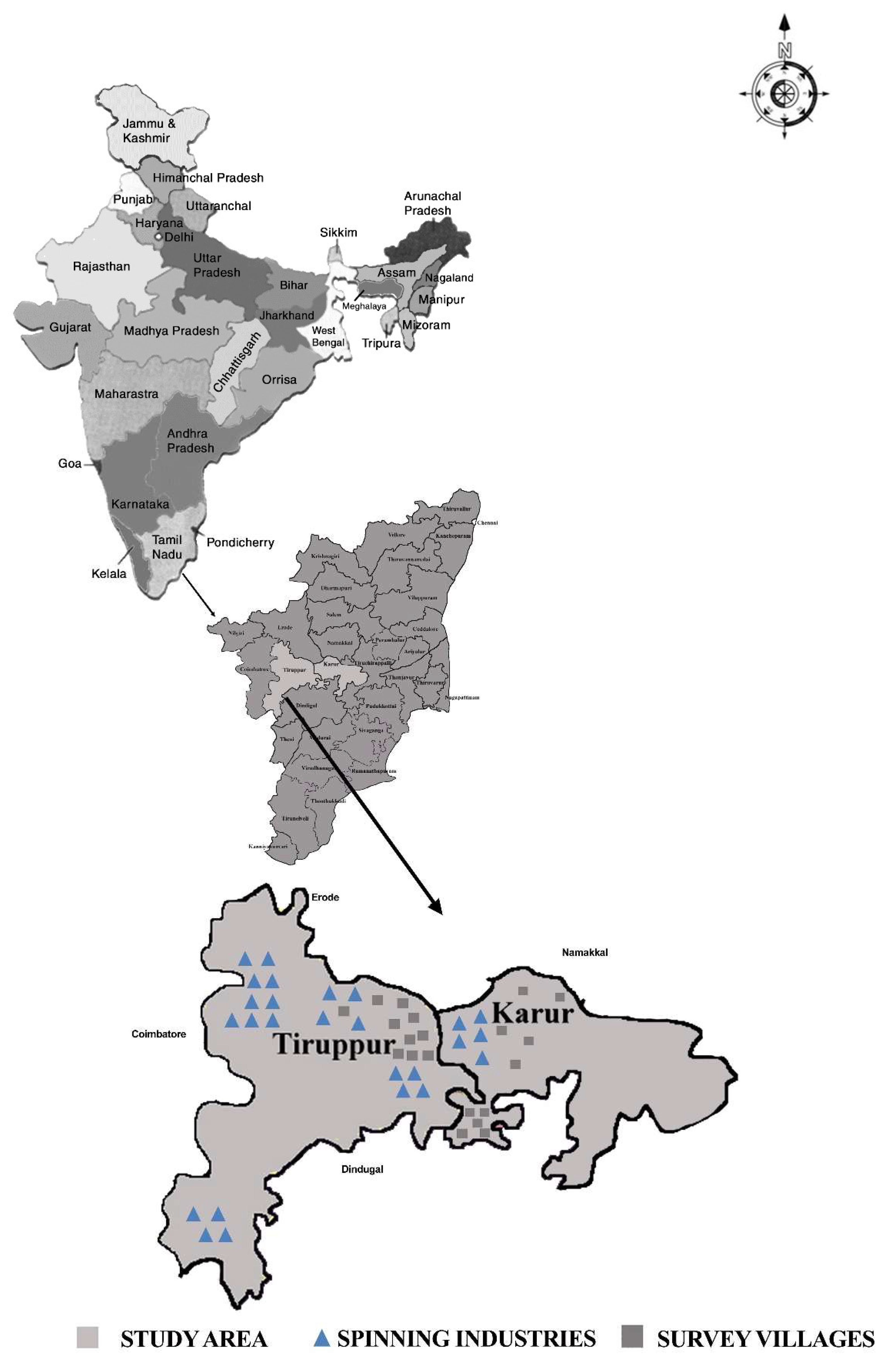

To address the above research question(s), the researchers purposefully selected Tiruppur and Karur districts, which are one of the primary hubs of textile industries (ginning, yarn spinning, weaving, processing, and textile manufacturing) within Tamil Nadu as well as in India. In these two districts, around 90 ginning and spinning mills operate and produce cotton gin trash as a by-product of the industry. The authors were unable to collate information on overall cotton processing since there was a scarcity of information on the capacities of these industries. Ginning one bale (170 kg) of cotton produces between 27 and 110 kg of cotton gin waste (18).

In these two districts, feeding of cotton gin waste for sheep is reported from 2016 onwards, while feeding of cattle started around the late 2000s. Till then, this trash’s utility potential as compost for agricultural crops and raw materials for building materials has been explored and utilised to an extent. Currently, these districts have 45 suppliers of cotton gin trash in addition to the local retailer(s) who are trading gin with sheep farmers in the study area. These suppliers handle around 75 to 100 tonnes per year (mostly during the summer period from mid-March to mid-August). These cotton gin trash bags are sold as 50 kg bag or as a bale of 170 kg to the farmers. The choice of cotton gin as an alternative feed resource during the summer has been well established within the farming community through their own learning, and these two districts are net importers of cotton gin trash from other spinning clusters in Rajapalayam and Dindigul, of Tamil Nadu.

2.2. Selection of sample

To understand the farmers' nature and factors driving the inclusion, a sample of 80 sheep farmers, who are using CGT in sheep feeding, were identified through snowfall sampling techniques. The surveyed farmers were distributed in Karur (20 farmers in each block of K. Paramathi and Aravakurichi) and Tiruppur districts (20 farmers in each block of Vellakoil and Kangayam) of Tamil Nadu India (

Figure 1).

2.3. Data collection

The selected farmers were interviewed on the usage pattern of cotton gins; their socio-personal and farming factors were recorded through a pre-tested interview schedule. In specific, the level of dependence on cotton gin (as a primary/secondary source of roughage), their socio-personal characters such as age, gender, education, occupation, experience, etc., farming contexts such as land holding and flock size, and sheep farming practices such as grazing, feeding, etc were collected. For the purpose of cross-checking the collected information and for better understanding, ‘focus group’ discussions were carried out with stakeholders.

2.4. Statistical analysis

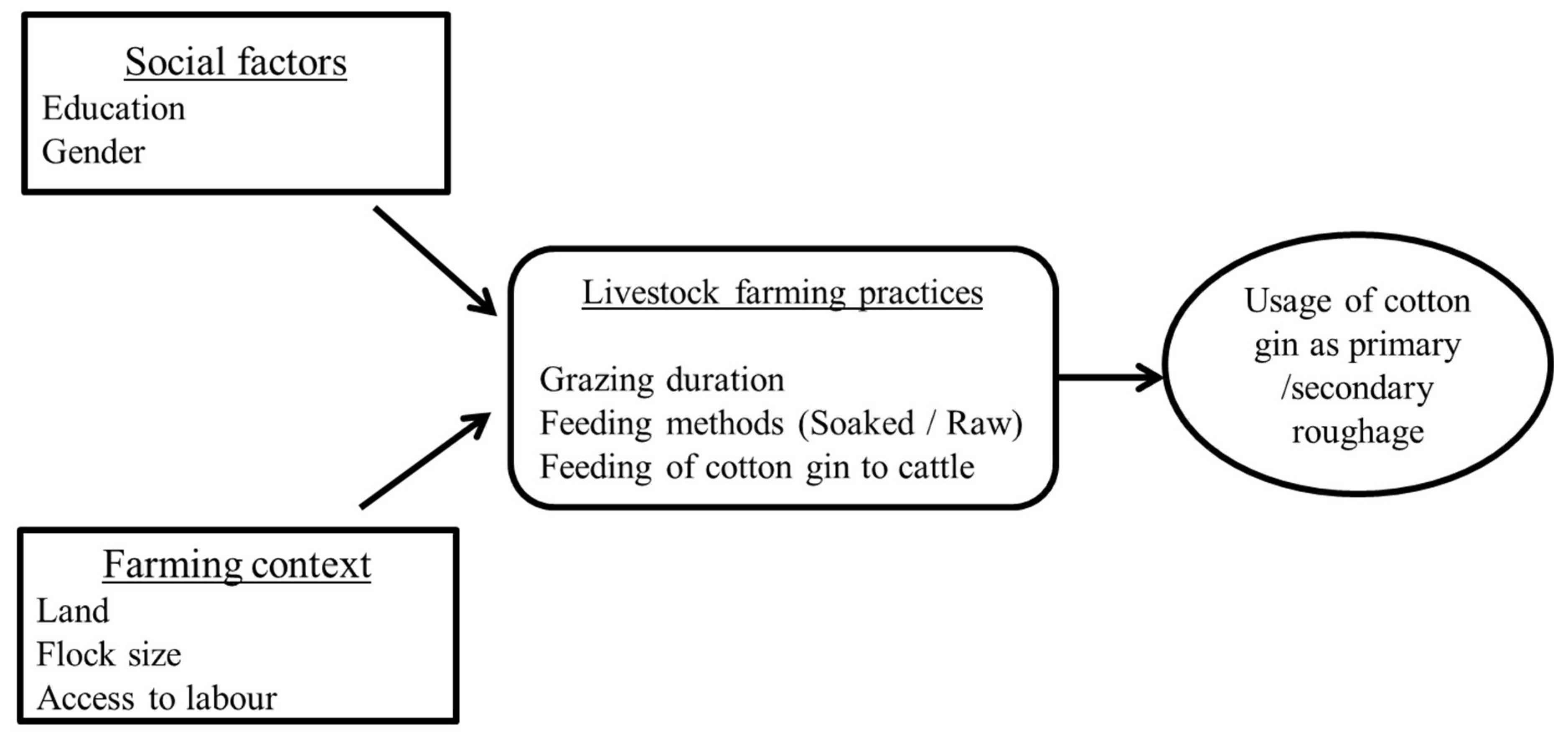

The collected data was analysed using descriptive statistics. Further eight variables, namely, gender, education, land holding, flock size, grazing duration, method of feeding gin and practice of feeding to other livestock, and availability of labour, were modelled in this study as detailed in

Figure 2 to understand the elements influencing the choice of cotton gin trash as roughage.

Added, binary logistic regression was used to understand the causal factors that influence the usage cotton gin as primary/secondary source of roughage. In logistic regression, if a farmer used CGT as primary source of roughage (>50% of conventional roughage replaced with CGT), the farmer was coded as 1 and farmers using as secondary source of roughage (< 50% of conventional roughage replaced with CGT) as 0. The logit model was as follows:

Cotton gin usage status = β0 + β1 x1 + β2 x2 + […] + βn xn where: x1, x2, x3 […] xn represent independent variables as depicted in model; β0 = constant; β1 , β2 are logistic variables; regression coefficients (estimates) Secondary source of roughage= 0, (≤0) Primary source of roughage = 1, (>0)

For the above purpose of regression analysis and descriptive statistics, researchers used Statistical package for social sciences (SPSS 16 version).

Socio-economic status of the sheep farmers

Socio-economic characteristics of farmers feeding CGT in the study area are presented in

Table 1 and

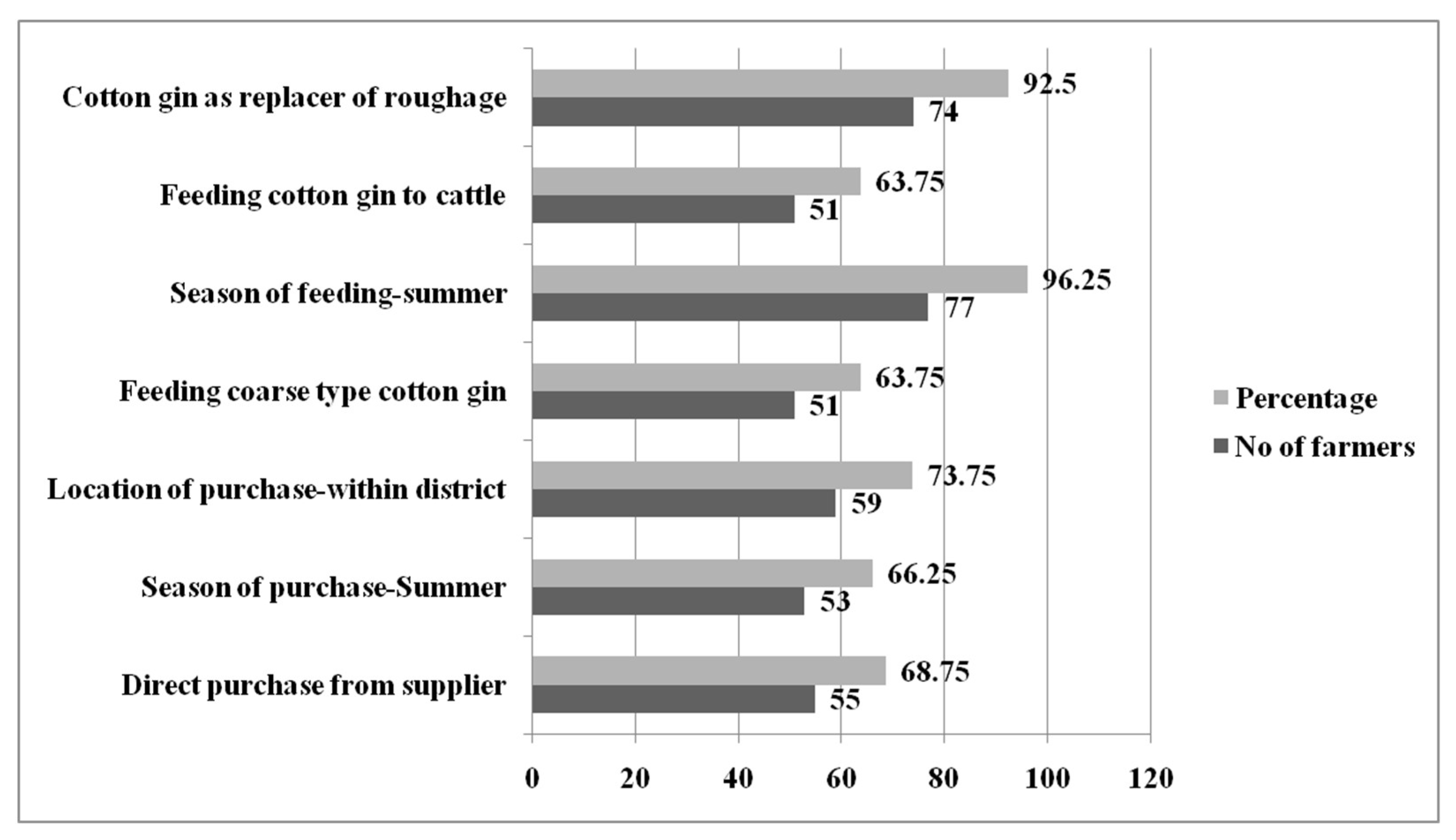

Figure 3. The results indicated that 96% of the sheep farmers were male and had an average age of 50 years in sheep farming in the study area. These farmers had 10 years of formal education and 24 years of sheep farming experience.

These farmers, on average, owned 16 acres of land, which is mostly rain-fed and has poor quality soil. Further, they had an average sheep population of 66 animals. Nearly 84% of sheep farmers had agriculture as their primary occupation, and six percent had sheep farming as their primary occupation. The remaining sheep farmers had the non-farm sector as their primary occupation. The farmers allowed their animals to graze on their own land for an average duration of 9 hours during the day. The sheep population in the study area is a non-migratory sheep population of Tamil Nadu. About 18% of farmers reported challenges in mobilising the necessary labour force for grazing and other sheep farming related activities. Their main occupation was agriculture along with sheep farming, and they earned an annual income of INR 153,000 per year from sheep farming. All the farmers have provided shelter to their sheep during the night, with the majority of sheds having an earthen floor, fence, and roof.

All the farmers were using CGT as a roughage source during fodder scarcity, particularly in the summer. Further, it indicated that the sheep farmers are utilising CGT as a feeding resource since the number of ginning factories and textile factories is higher in their area. Nearly 64% of sheep farmers preferred the coarse type of CGT, and the remaining used the fine type of CGT (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) due to quality perception and price variances. The majority (63.75 %) of the farmers were feeding CGT to their cows in addition to their sheep. About 88% of farmers were highly satisfied and 11% with CGT as a feeding material and the remaining were not satisfied. All the surveyed farmers had a practice of feeding either commercial concentrate or homemade concentrate feed in addition to CGT.

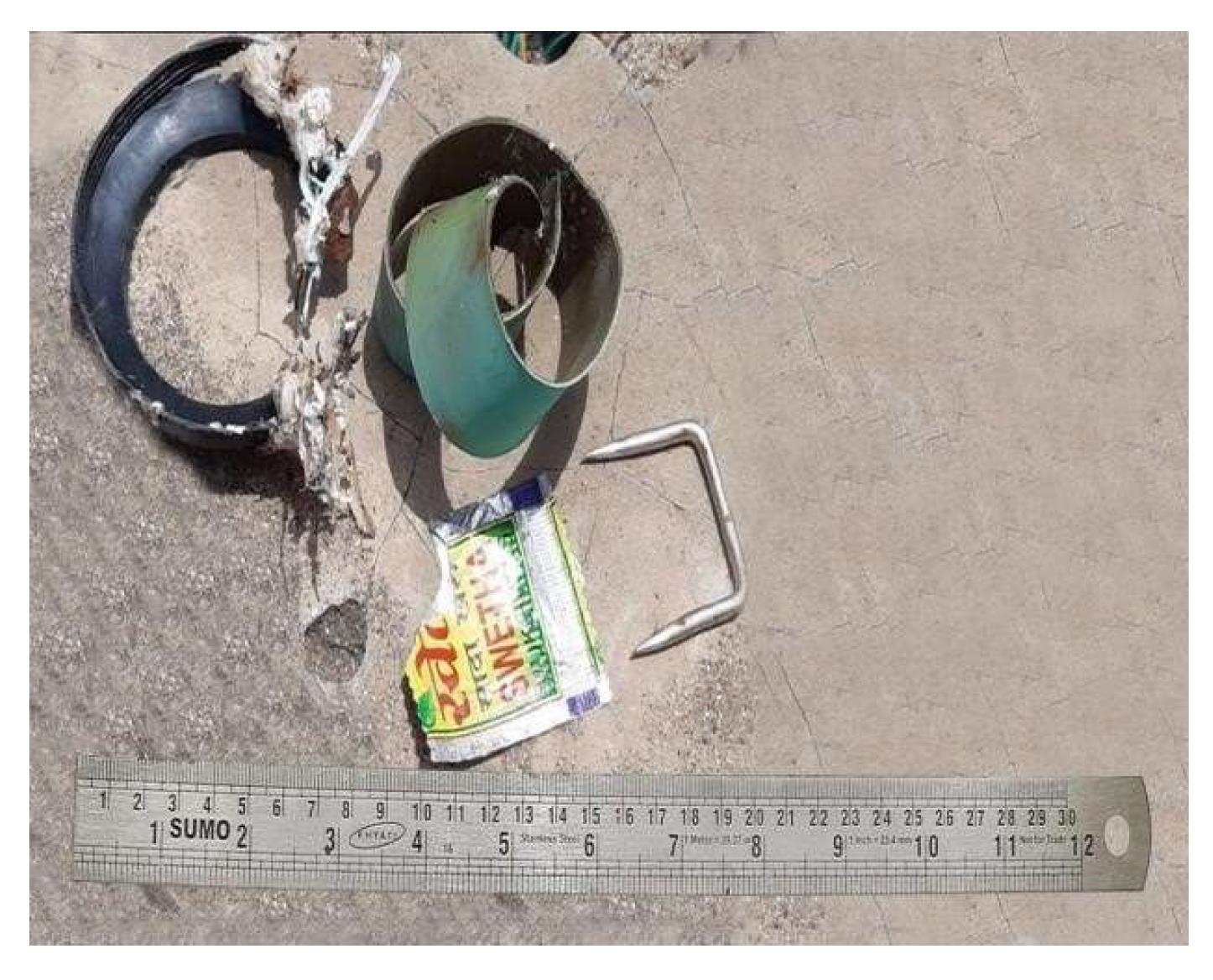

The inclusion of CGT as a replacement for conventional roughage (sorghum sorghum and groundnut haulms) varied among farmers. More than one-fifth (21%) of farmers replaced >50% of conventional roughage with CGT, and the remaining had less than 50%. The average replacement of roughage was 51% on a dry matter basis. The study also found that CGT has foreign particles of both metallic and non-metallic nature (

Figure 6), and the sheep farmers were manually removing the foreign particles or using magnets to remove the foreign particles (

Figure 7).

Furthermore, about 79% of farmers practiced feeding CGT after soaking it for 2 to 3 hours in water. These sheep farmers have an average experience of 2.5 years (ranging from 4 months to 6 years) in feeding CGT. Thus, feeding CGT is relatively new among sheep farmers. The farmers paid an average price of INR 14/per kg (price range: INR 8 to 22). All the farmers were highly satisfied with using CGT and had not noticed any health issues related to feeding CGT to their sheep.

In order to understand the factors influencing the choice of CGT as a primary or secondary source of roughage, researchers have included eight explanatory variables in the regression model due to limitations in the sample size (

Table 2). The bi-nominal logit regression model, which tested the significance of the predictor variables, found that the model is significant (at a one percent level of probability with a Chi-square value of 28.65). This estimated model correctly classified 78 percent of the farmers using CGT as primary rough-age. The conceptualised variables, namely gender, education, land, flock size, grazing hours, feeding of gin to cattle, feeding method, and labour availability, explained about 46.7% (Pseudo R2 = 0.467) of the variance in usage of CGT (as a primary or secondary roughage source) among the farmers. The remaining variance (53.4%) may be due to other attributes that have not been identified by this research work. Even though many variables explained variance, land size (P<0.01) and access to labour force (P<0.01) positively influenced the odds of using CGT as a primary source of roughage.

For one unit change in land holdings and access to labour force, the estimated odds of us-ing CGT as a primary source of roughage (Odds ratio) are multiplied by 1.23 and 9.42, respectively. While flock size (P<0.01) and the practice of feeding CGT to cattle (P<0.05) negatively influence the odds of inclusion as a primary source of roughage (

Table 2). Estimated coefficients of logistic regression for factors influencing the usage of CGT as a primary source of roughage.

Discussion

The socio-personal and economic characteristics of farmers and landholdings of sheep farmers in cotton gin trash feeding areas were in line with the observations of other researchers (21 and 22) except land holdings. The land holdings of sheep farmers were 16 acres, compared to the landholding size of around 2.5 acres for livestock farmers (23, 24). Even though farmers' landholdings were large, the land in the study area has limited underground water resources and is located in poor monsoon and drought prone districts of Tamil Nadu (20, 25). Thus, economic returns from cropping were limited, and farmers needed to rely on subsidiary activities such as sheep rearing in the study area.

The flock size at the study area ranged from 32 to 120, similar to other parts of India (26) where non-migratory sheep farming activities are carried out. These sheep owners grazed their animals over nine hours in their own grazing land referred to as Korangadu (a traditional unique pasture land system in rain-fed areas), where they grazed their sheep (27). The Korangadu is a rich source of Cenchrus Ciliaris as fodder, which animals rely on as a feed source. The duration of grazing on these grazing lands is more than 9 hours, which is almost similar to other parts of India where non-migratory sheep farmers have similar practices (4).

In addition to grazing, there is practice of supplementing roughages and concentrates at the shelter. Thus, sheep rearing in the study area was more of a semi-intensive nature. Furthermore, the housing practices of farmers in the study area, with a prime purpose of providing shelter in the night hours, reflect the pattern in other parts of India. In specific, this study’s findings is line with the observations of researchers in India (27–29). Thus, over all, the socio-personal characteristics, farm characteristics, and managemental practices of sheep farmers in cotton gin feeding areas are similar to those of other areas of India.

Use of CGT is used as a roughage source during times of fodder scarcity, particularly in the summer, may be attributed to its nutrimental characteristics as one of the sources for protein and energy (30, 31) and the use of non-conventional feed resources in periods of feed scarcity for animal feeding. Tapping of non-conventional feed resource CGT in the study area during scarcity in animal feeding is in concurrence with past studies in various parts of India where similar cope up mechanisms have been adopted during monsoon failures/feed scarcity (32–34). Coarse type of CGT was the choice against fine type CGT on account of perceived nutritional qualities. The farmers perceived that the presence of seed residues in coarse improves the nutritional quality, and usage of the same has increased average daily weight gain (ADG).

The farmers' observations on animal performance and communication of the same during farmer-to-farmer interactions have resulted in coarse being the popular choice among farmers. Further, nutritional analysis of two types of CGT revealed that coarse CGT was richer in crude protein (Fine gin cotton trash – 10 to 12 % versus coarse cotton gin trash- 12 to 15%). Added to that, in the study area, widespread usage of CGT for cows has also been noticed in addition to sheep, which may be due to the viable nature of CGT if supplemented with the required concentrate and fodder (35, 36). In the study area, the farmers initially experimented with cotton gin as cattle feed and then scaled up to the practice of feeding cotton gin to sheep. At the same time, the majority of farmers reported that the CGT has foreign and dusty materials that need to be handled with precaution. Researchers reported that the presence of foreign materials in cotton gin trash is very common (13), but farmers perceived that there were no health risks associated with CGT feeding, which is in concurrence with past experimental evidence (37–41). This may be due to the farmer’s practice of segregating foreign bodies either using magnets or through a manual process using hands. At the same time, there was wide variation in replacing the conventional roughages in sheep feeding. This variation may be due to differences among by-products, transport costs, storage, moisture content, nutrient composition, availability, and possible contaminants (13, 42, 43).

In addition to the role of nutritional factors, contaminants and transport costs influence inclusion. Further, this study observed that farming contexts such as landholding and farm labour shortages positively influenced the level of inclusion. While flock size and feeding to other livestock negatively influenced the level of inclusion. A similar observation also reported that resources such as land have a positive influence on the adoption of feeding practice in dairy farming (24).This study, too, found that the inclusion level was positively determined by land. This may be due to the affordability of farmers with higher land resources to spend on their enterprises compared to farmers with poor landholdings. Furthermore, farmers with land holdings may be primarily focused on crop related activities and may have limitations in the allocation of land and labour force for grazing. These may be reasons for more dependence on CGT among large landholding farmers. At the same time, this study found that flock size and feeding CGT to cattle negatively influenced the inclusion level. This may be due to the fact that large-flock size farmers may be hesitating to make recurring expenditures on feed and may rely on grazing resources to meet the requirement. Furthermore, in the case of small flocks, farmers had better judgement to meet their feeding requirements compared to larger flocks. These may be the reasons for restricting the use of CGT in feeding among large flock owners. Added to that, farmers with cattle may prioritise feed resource utilisation based on the nature /scale of returns from the activity. The cattle provide daily income through the sale of milk and higher returns, while in the case of sheep, farmers need to wait for 8 to 10 months to fetch returns through the sale of animals for meat. Thus, there is a tradeoff in the usage of CGT between dairy animals and sheep in the study area. This factor limits the feeding of CGT to sheep. Thus, farms that practice of feeding CGT to cattle and have large sheep flocks are less likely to use cotton gin as primary roughage. Overall, the elements included in the regression model explained about 47% of the variance on inclusion level (extent of use as a primary or secondary source of roughage), and the remaining variance may be due to perceived nutritional quality over the existing resources, access to CGT, contaminants, farmer’s knowledge, psychological behaviour, etc (44–47), which was not studied on account of the nature of the collected data, which limits further statistical exploration. This needs to be explored in future research.

Conclusion

To sum up, the study makes an attempt to understand the utilisation pattern of CGT and the factors influencing the farmers to choose CGT as the primary source of roughage in the industrial cluster of cotton processing industries using survey technique. Analysis of the data collected during the survey revealed that CGT is used as feeding material during the summer as a replacement for conventional roughage. The coarse type of CGT was the choice of farmers on account of its perceived nutritional quality and its ability to promote weight gain. The sheep farmers are very satisfied with the usage of CGT, as an alternative feed during scarcity. Further farmers reported the presence of forgiven materials and removed them using magnets /manually. Overall, farmers perceived there were not many health issues with feeding CGT. But the replacement level of roughage varied widely among the farmers. Farming contexts of households and livestock farming practices has influenced the choice of CGT as the primary source of roughage. The choice of CGT as feed, the perception of farmers on quality, level of inclusion, and methods to segregate foreign and dust particles need to be scientifically validated and standardized in the future, as they are being utilised largely by sheep farmers.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript and their contribution are: conceptualization, NSB, SR, JM, PV, AKT and KS; methodology, NSB, PV and DTK; software, NSB, DTK, AKT; validation, NSB, AKT, VS and VK; formal analysis, NSB, DTK; investigation, NSB; resources, SR, KS and JM; data curation, NSB and DTK; original draft preparation, NSB, DTK, VS, VK; review and editing, AKT, VS, VK; visualization, NSB and DTK; supervision, SR, KS, JM, PV and AKT; project administration, SR, KS and JM; funding acquisition, SR, KS and JM.

Funding

The financial support for the project has been provided by Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study has been conducted as per the reference Lr. No. 7236/Edu.Cell/C1/2019 dated 17.08.2019 of the by Institutional Biosafety Ethical Committee (IBSC) of the institute.

Informed Consent Statement

The nature of the study was explained in detail to farmers and voluntary participation was promoted. Signed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be available to the needy scientist as per the MDPI transparent policy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University for its administrative and financial assistance in carrying out the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors say they have no competing interests.

References

- Porwal, K.; Karim, S. A.; Sisodia; Singh, V. K. Socio-Economic Survey of Sheep Farmers in Western Rajasthan. Indian Journal of Small Ruminant Reseach 2006, 14, 74–81.

- Kumaravelu, N. Analysis of Sheep Production System in Southern and Northern Zones of Tamil Nadu, 2007.

- Suresh, A.; Gupta, D. C.; Mann, J. C. Constraints in Adoption of Improved Management Practices of Sheep Farming in Semi-Arid Region of Rajasthan. Indian Journal of Small Ruminant Reseach 2008, 14, 93–98.

- Singh, A. K. Non-Conventional Feed Resources for Small Ruminants. 2018, 2 (2).

- Meglas, M. D.; Martinez, T. A.; Gailego, J. A.; Sanchez, M. Silage of Byproducts of Artichoke. Evaluation and Modification of the Quality of Fermentation. Options Mediterraneennes, Ser A 1991, 16, 141–143.

- Ghaffari, M. H.; Tahmasbi, A. M.; Khorvash, M.; Naserian, A. A.; Vakili, A. R. Effects of Pistachio By-Products in Replacement of Alfalfa Hay on Ruminal Fermentation, Blood Metabolites, and Milk Fatty Acid Composition in Saanen Dairy Goats Fed a Diet Containing Fish Oil. Journal of Applied Animal Research 2014, 42 (2), 186–193. [CrossRef]

- Sarnklong, C.; Cone, J. W.; Pellikaan, W.; Hendriks, W. H. Utilization of Rice Straw and Different Treatments to Improve Its Feed Value for Ruminants: A Review. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci 2010, 23 (5), 680–692. [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, G.; Ganai, A.; Sheikh, F.; Bhat, S. A.; Masood, D.; Mir, S.; Ahmad, I.; Bhat, M. A. Effect of Feeding Urea Molasses Treated Rice Straw along with Fibrolytic Enzymes on the Performance of Corriedale Sheep. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies.

- ANGRAU. ANGRAU Crop Outlook Reports of Andhra Pradesh COTTON– January to December, 2021., 2022. https://angrau.ac.in/downloads/AMIC/OutlookReports/2021/4-COTTON_January%20to%20December,%202021.pdf. (accessed 2023-10-06).

- GoI, Ministry of Textiles. Cotton Sector. Annexure VII (361555/2022/Cotton)., 2022. https://texmin.nic.in/sites/default/files/Cotton%20Sector.pdf.

- Lakwete, A. Inventing the Cotton Gin-Machine and Myth in Antebellum America, 2003.

- Cohen, T. M. ; Lansford, R. R.Technical Report on Survey of Cotton Gin and Oil Seed Trash Disposal Practices and Preferences in the Western U.S., 1992.

- Rogers, G. M.; Poore, M. H.; Paschal, J. C. Feeding Cotton Products to Cattle. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 2002, 18 (2), 267–294. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J. B.; Rankins, D. L. Comparison of Cotton Gin Trash and Peanut Hulls as Low-Cost Roughage Sources for Growing Beef Cattle. The Professional Animal Scientist 2008, 24 (1), 40–46. [CrossRef]

- Crossan, A. N.; Kennedy, I. R. Calculation of Pesticide Degradation in Decaying Cotton Gin Trash. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 2008, 81 (4), 355–359. [CrossRef]

- Warner, A. L.; Beck, P. A.; Foote, A. P.; Pierce, K. N.; Robison, C. A.; Hubbell, D. S.; Wilson, B. K. Effects of Utilizing Cotton Byproducts in a Finishing Diet on Beef Cattle Performance, Carcass Traits, Fecal Characteristics, and Plasma Metabolites. Journal of Animal Science 2020, 98 (2), skaa038. [CrossRef]

- Myer, R. O. Cotton Gin Trash: Alternative Roughage Feed for Beef Cattle, 2011.

- Cotton Corporation, India. Annual Report, 2011.

- Fairlabor. Understanding the Characteristics of the Sumangali Scheme in Tamil Nadu Textile & Garment Industry and Supply Chain Linkages, 2012. https://www.solidaridadnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/migrated-files/publications/Understanding_Sumangali_Scheme_in_Tamil_Nadu.pdf.

- Vengateswari, M.; Geethalakshmi, V.; Bhuvaneswari, K.; Jagannathan, R.; Panneerselvam, S. District Level Drought Assessment over Tamil Nadu. Madras. MAJ 2019.

- Rao, S. T. V.; Thammi Raju, D.; Ravindra Reddy, Y. Adoption of Sheep Husbandry Practices in Andhra Pradesh, India. Livestock Research for Rural Development 2008, 20 (7).

- Thilakar, P.; Krishnaraj, R. Profile Characteristics of Sheep Farmers: A Survey in Kancheepuram District of Tamil Nadu. 2014, 5 (3), 35–36.

- Jothilakshmi, M.; Thirunavukkarasu, D.; Sudeepkumar, N. K. Exit of Youths and Feminization of Smallholder Livestock Production–a Field Study in India. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2014, 29 (2), 146–150. [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukkarasu, D.; Narmatha, N.; Alagudurai, S. What Drives the Adoption of Fodder Innovation(s) in a Smallholder Dairy Production System? Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study of Dairy Farmers in India. Trop. grassl.-Forrajes trop. 2021, 9 (3), 371–375. [CrossRef]

- NABARD. Accelerating the Pace of Capital Formation in Agriculture and Allied Sector” Is the Main Theme of This Potential Linked Credit Plan for 2016-17.PLP 2016-17, 2016.

- Shivakumara, C.; Reddy, B. S.; Patil, S. S. Socio-Economic Characteristics and Composition of Sheep and Goat Farming under Extensive System of Rearing. ASD 2020, 40 (01). [CrossRef]

- Akila, N. Management and Marketing Pattern of Mecheri Sheep in Tamil Nadu; An Exploratory Analysis of Karur District. Indian J. Small Rum. 2014, 20, 161-164.

- Senthilmuthukumaran, S. Impact of Mega Sheep Seed Project on Mecheri Sheep Performance and Farmers Livelihood, 2017.

- Singh, B.; Meena, K. C.; Indoria, D.; Meena, G. S. Adoption of Improved Sheep Rearing Practices in the Eastern Part of Rajasthan, India. Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci 2020, 9 (5), 271–277. [CrossRef]

- Lalor, W. F. ; Jones, J. K. ; Slater, G. A. Cotton Gin Trash as a Ruminant Feed, 1975.

- Myer, R. O. ; Hersom, M. Alternative Feeds for Beef Cattle. 2003.

- Singh, B.; Meena, G. S.; Meena, K. C.; Singh, N. Feeding and Healthcare Management Practices Adopted by Sheep Farmers in Karauli District of Eastern Rajasthan, India. Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci 2018, 7 (2), 309–316. [CrossRef]

- Jothilkashmi, M.; Akila, N. Experiences in Promoting Ensiling of Onion Crop Residue among Smallholder Dairy Farmers in Namakkal District of Tamil Nadu. irjee 2022, 22 (4), 27–31. [CrossRef]

- Moanarol; Ngullie, E.; Walling, I.; Krose, M.; Bhate, B. P. Traditional Animal Husbandry Practices in Tribal States of Eastern Himalaya, India: A Case Study. 2011.

- Hill, G. M.; Rivera, J. D.; Franklin, A. N.; Stone, G. W.; Tillman, D. R.; Mullinix, B. G. Evaluation of Cotton-Gin Trash Blocks Fed to Beef Cattle11Manuscript No. 12206, Approved by the Mississippi Agriculture and Forestry Experiment Station, Starkville. The Professional Animal Scientist 2013, 29 (3), 260–270. [CrossRef]

- Bathini, H.; Valli, C.; Balakrishnan, V. Supplemental Strategy to Improve Nutritive Value of Cotton Gin Waste - a Potential Cattle Feed. Indian Veterinary Journal 2019, 96 (8), 9–11.

- Mertens, D. R. Creating a System for Meeting the Fiber Requirements of Dairy Cows. Journal of Dairy Science 1997, 80 (7), 1463–1481. [CrossRef]

- Khalafalla, M. Effect of Dietary Level of Cotton Gin Trash on Nutrients Utilization and Performance of Sudan Desert Lambs, 1988.

- Parish, J. A. Fiber in Beef Cattle Diets, 2008.

- Galyean, M. L.; Hubbert, M. E. REVIEW: Traditional and Alternative Sources of Fiber—Roughage Values, Effectiveness, and Levels in Starting and Finishing Diets11Substantial Portions of This Paper Were Presented at the 2012 Plains Nutrition Council Spring Conference and Published in the Conference Proceedings (AREC 2012-26, Texas AgriLife Research and Extension Center, Amarillo). The Professional Animal Scientist 2014, 30 (6), 571–584. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A. P.; De Figueiredo, M. P.; De Quadros, D. G.; Ferreira, J. Q.; Whitney, T. R.; Luz, Y. S.; Santos, H. R. O.; Souza, M. N. S. Chemical and Biological Treatment of Cotton Gin Trash for Fattening Santa Ines Lambs. Livestock Science 2020, 240, 104146. [CrossRef]

- Rankins, D. L. The Importance of By-Products to the US Beef Industry. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 2002, 18 (2), 207–211. [CrossRef]

- Kunkle, W.; Stewart, R.; Brown, W. Using Byproduct Feeds in Supplementation Programs. Undated.

- Rogers, E. M. Diffusion of Innovations; 2003.

- Castaño, R.; Sujan, M.; Kacker, M.; Sujan, H. Managing Consumer Uncertainty in the Adoption of New Products: Temporal Distance and Mental Simulation. Journal of Marketing Research 2008, 45 (3), 320–336. [CrossRef]

- Arts, J. W. C.; Frambach, R. T.; Bijmolt, T. H. A. Generalizations on Consumer Innovation Adoption: A Meta-Analysis on Drivers of Intention and Behavior. International Journal of Research in Marketing 2011, 28 (2), 134–144. [CrossRef]

- Dessart, F. J.; Barreiro-Hurlé, J.; Van Bavel, R. Behavioural Factors Affecting the Adoption of Sustainable Farming Practices: A Policy-Oriented Review. European Review of Agricultural Economics 2019, 46 (3), 417–471. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).