Submitted:

19 June 2023

Posted:

19 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Plecenik, T.; Moško, M.; Haidry, A.A.; Ďurina, P.; Truchlý, M.; Grančič, B.; Gregor, M.; Roch, T.; Satrapinskyy, L.; Mošková, A.; et al. Fast highly-sensitive room-temperature semiconductor gas sensor based on the nanoscale Pt–TiO2–Pt sandwich. Sens. Actuators B 2015, 207, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wu, M.; Huang, Y.; Song, J.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Chen, F.; Zhao, J.; Chen, W. Influences of impurity gases in air on room-temperature hydrogen-sensitive Pt–SnO2 composite nanoceramics: a case study of H2S. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Kadir, R.; Li, Z.; Sadek, A.Z.; Abdul Rani, R.; Zoolfakar, A.S.; Field, M.R.; Ou, J.Z.; Chrimes, A.F.; Kalantar-zadeh, K. Electrospun granular hollow SnO2 nanofibers hydrogen gas sensors operating at low temperatures. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 3129–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, W.T.; Cho, H.J.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Shin, H.; Penner, R.M.; Kim, I.D. Chemiresistive hydrogen sensors: fundamentals, recent advances, and challenges. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 14284–14322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matushko, I.P.; Oleksenko, L.P.; Maksymovych, N.P.; Lutsenko, L.V.; Fedorenko, G.V. Nanosized Pt-SnO2 gas sensitive materials for creation of semiconductor sensors to hydrogen. Mol. Cryst. Liquid Cryst. 2021, 719, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, L.X.; Liu, M.Y.; Zhu, L.Y.; Zhang, D.W.; Lu, H.L. Recent progress on flexible room-temperature gas sensors based on metal oxide semiconductor. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, Y. Recent advances in SnO2 nanostructure based gas sensors. Sens. Actuators B 2022, 364, 131876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Neri, G.; Pinna, N. Nanostructured materials for room-temperature gas sensors. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 795–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Bi, M.; Xiao, Q.; Gao, W. Ultrasensitive gas sensor based on Pd/SnS2/SnO2 nanocomposites for rapid detection of H2. Sens. Actuators B 2022, 359, 131612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Jiang, T.; Xu, X.; Wang, C. Ultrasensitive hydrogen sensor based on Pd0-loaded SnO2 electrospun nanofibers at room temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 2013–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hu, K.; Yang, P.; Fu, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, S.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Y.; Gu, H. Hydrogen sensors based on Pt-decorated SnO2 nanorods with fast and sensitive room-temperature sensing performance. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 811, 152086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Meng, F.; Chen, K.; Wang, T.; Sun, P.; Liu, F.; Yan, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, F.; Shimanoe, K.; et al. High-performance acetone gas sensor based on Ru-doped SnO2 nanofibers. Sens. Actuators B 2020, 320, 128292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Li, P.; Wu, G.; Li, Z.; Wu, P.; Hu, Y.; Gu, H.; Chen, W. Extraordinary room-temperature hydrogen sensing capabilities with high humidity tolerance of Pt SnO2 composite nanoceramics prepared using SnO2 agglomerate powder. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2018, 43, 21177–21185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.J.; Guo, X.M. Tuning the oxygen defects and Fermi levels via In3+ doping in SnO2-In2O3 nanocomposite for efficient CO detection. Sens. Actuators B 2022, 357, 131412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.Q.; Zheng, X.K.; Shen, Q.; Wang, W.J.; Dong, W.Q. Hydrothermal synthesis and their ethanol gas sensing performance of 3-dimensional hierarchical nano Pt/SnO2. J. Alloy. Compd. 2022, 909, 164693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, J. A gas sensor based on Ag-modified ZnO flower-like microspheres: Temperature-modulated dual selectivity to CO and CH4. Surf. Interfaces 2021, 24, 101110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wu, G.; Fei, L.; Zhang, S.; Hu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gu, H.; Chen, W. Mechanism study on extraordinary room-temperature CO sensing capabilities of Pd-SnO2 composite nanoceramics. Sens. Actuators B 2019, 285, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhao, T.Y.; Lian, G.; Yu, Q.Q.; Luan, C.H.; Wang, Q.L.; Cui, D.L. Room temperature CO sensor fabricated from Pt-loaded SnO2 porous nanosolid. Sens. Actuators B 2013, 184, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.T.; Zhou, W.D.; Li, J.; Lv, P.; Wang, Q.; Wang, D.; Wu, F.y.; Dastan, D.; Garmestani, H.; Shi, Z.; et al. Tin dioxide nanoparticles with high sensitivity and selectivity for gas sensors at sub-ppm level of hydrogen gas detection. J. Mater. Sci.-Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 14687–14694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocemba, I.; Rynkowski, J. The influence of catalytic activity on the response of Pt/SnO2 gas sensors to carbon monoxide and hydrogen. Sens. Actuators B 2011, 155, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Suematsu, K.; Yuasa, M.; Kida, T.; Shimanoe, K. Effect of water vapor on Pd-loaded SnO2 nanoparticles gas sensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 5863–5869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matushko, I.P.; Fedorenko, G.V.; Oleksenko, L.P.; Maksymovych, N.P. Platinum containing semiconductor nanomaterials based on SnO2 with Pt-additives to analyze concentration of CH4 in air. Mol. Cryst. Liquid Cryst 2023, 752, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Z.; Shao, Z.P.; Xu, N.P. Partial oxidation of dimethyl ether to H2/syngas over supported Pt catalyst. J. Nat. Gas Chem. 2008, 17, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, H.; Mortazavi, Y.; Khodadadi, A.A.; Saberi, M.H.; Alirezaei, S. Enormous enhancement of Pt/SnO2 sensors response and selectivity by their reduction, to CO in automotive exhaust gas pollutants including CO, NOx and C3H8. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 546, 149120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.J.; Guo, X.M. Co/Au bimetal synergistically modified SnO2-In2O3 nanocomposite for efficient CO sensing. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 15979–15989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaduman, I.; Er, E.; Celikkan, H.; Erk, N.; Acar, S. Room-temperature ammonia gas sensor based on reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites decorated by Ag, Au and Pt nanoparticles. J. Alloy. Compd. 2017, 722, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Huang, L.; Wang, T.; Hao, X.; Wang, B.; Lu, Q.; Liang, X.; Liu, F.; Liu, F.; Wang, C.; et al. Based Nafion gas sensor utilizing Pt-MOx (MOx = SnO2, In2O3, CuO) sensing electrode for CH3OH detection at room temperature in FCVs. Sens. Actuators B 2021, 346, 130543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Park, J.E.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, E.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, W. Ultra-sensitive hydrogen gas sensors based on Pd-decorated tin dioxide nanostructures: room temperature operating sensors. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 12568–12573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.Z.; Jia, F.C.; Lv, B.J.; Qin, Z.L.; Liu, P.D.; Chen, Y.L. Facile synthesis and remarkable hydrogen sensing performance of Pt-loaded SnO2 hollow microspheres. Mater. Res. Bull. 2018, 106, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.N.; Bi, M.S.; Gao, W. Rapid response hydrogen sensor based on Pd@Pt/SnO2 hybrids at near-ambient temperature. Sens. Actuators B 2022, 370, 132406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

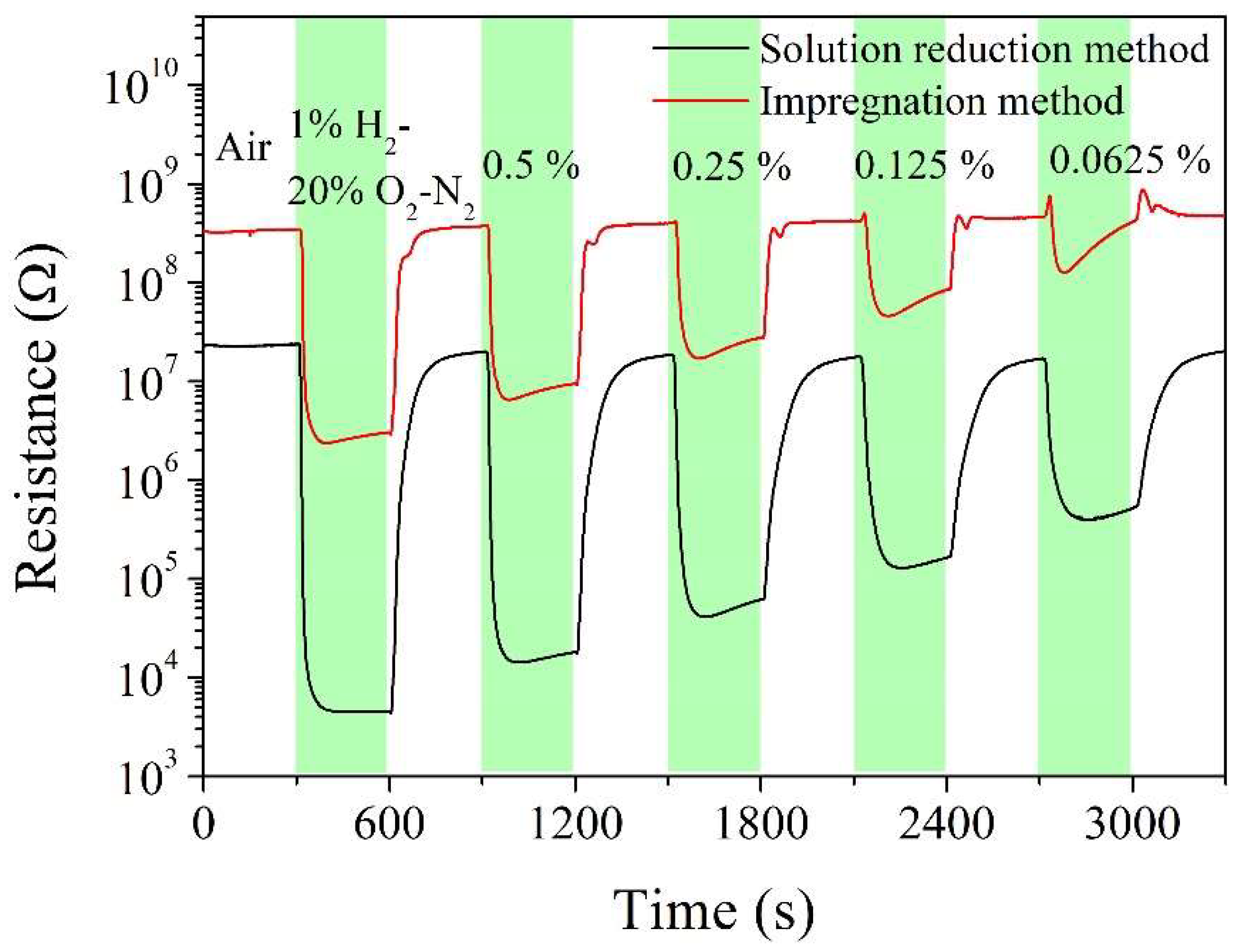

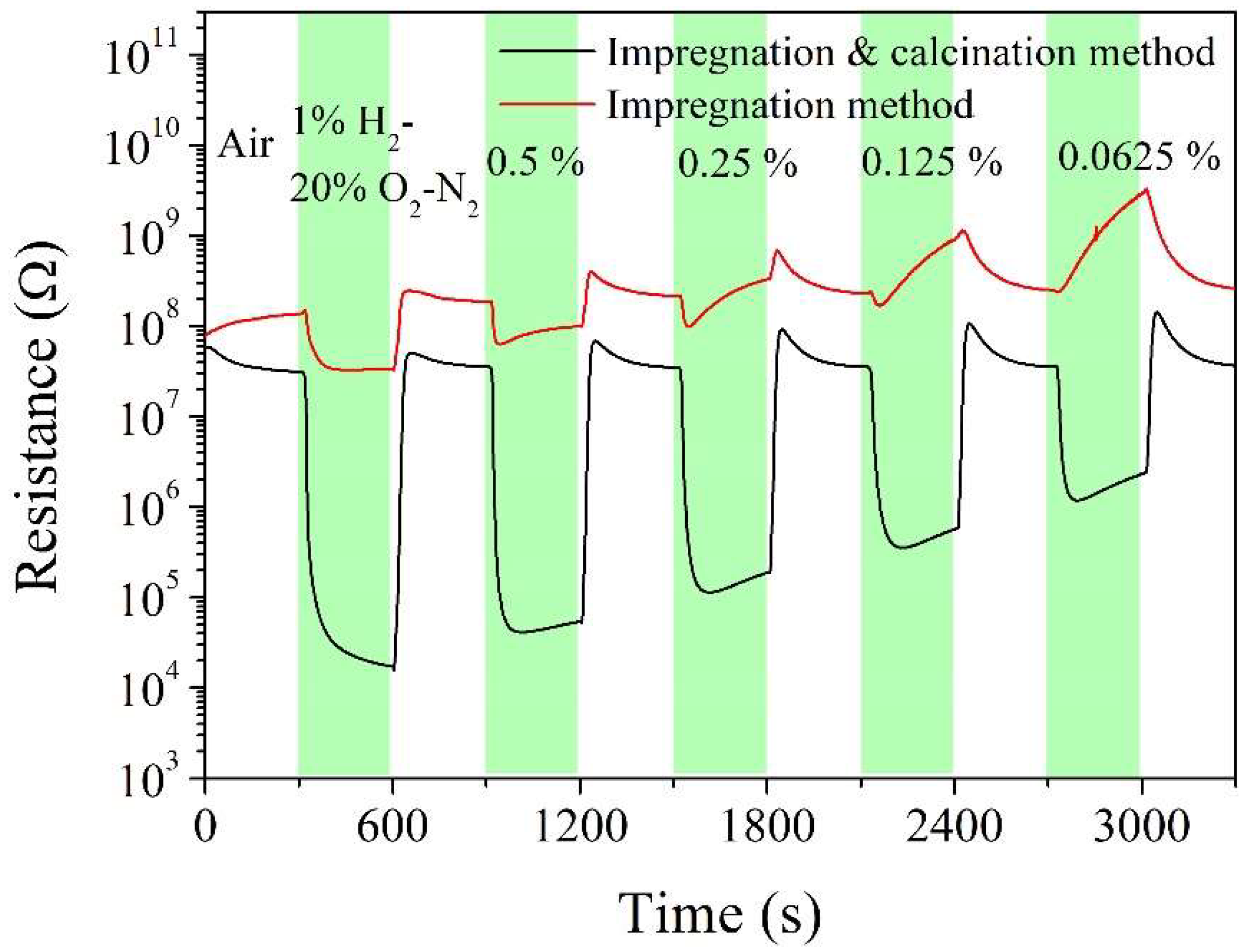

- Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Li, P.; Cheng, L.; Hu, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Guo, S.; Gu, H.; Chen, W. Transforming Pt-SnO2 nanoparticles into Pt-SnO2 composite nanoceramics for room-temperature hydrogen-sensing applications. Materials 2021, 14, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Cui, P.; Guo, S.; Chen, W.; Tang, Z.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, Z. Contrasting room-temperature hydrogen sensing capabilities of Pt-SnO2 and Pt-TiO2 composite nanoceramics. Nano Res. 2016, 9, 3528–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, P.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Hu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Chen, W. Room-temperature hydrogen-sensing capabilities of Pt-SnO2 and Pt-ZnO composite nanoceramics occur via two different mechanisms. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, F.; Meng, L.; Hu, Y.; Chen, W. Aging and activation of room temperature hydrogen sensitive Pt–SnO2 composite nanoceramics. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 15267–15275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.-S.; Wu, C.-H.; Wu, R.-J. Application of Pt@SnO2 nanoparticles for hydrogen gas sensing. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2018, 65, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.L.; Wang, Z.B.; Wu, Z.Y.; Zhang, P.; Hu, S.X.; Jin, X.S.; Li, M.; Lee, J.H. Characterization and modeling of a Pt-In2O3 resistive sensor for hydrogen detection at room temperature. Sensors 2022, 22, 7306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadhim, I.H.; Abu Hassan, H.; Abdullah, Q.N. Hydrogen gas sensor based on nanocrystalline SnO2 thin film grown on bare Si substrates. Nano-Micro Lett. 2016, 8, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Yang, S.; Lu, X.Y.; Wang, T.Q.; Zhang, X.M.; Fu, Y.; Qi, W. Controllable fabrication of PdO-PdAu ternary hollow shells: synergistic acceleration of H2-sensing speed via morphology regulation and electronic structure modulation. Small 2022, 18, 2106874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.M.; Wang, T.Q.; Li, X.F.; Li, Q.; Zhang, X.M.; Cao, T.L.; Li, Y.N.; Zhang, L.Y.; Guo, L.; Fu, Y. Pd-decorated PdO hollow shells: a H2-sensing system in which catalyst nanoparticle and semiconductor support are interconvertible. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 42971–42981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Li, X.S.; Zhu, B.; Zhu, X.B.; Lian, H.Y.; Zhu, A.M. A facile approach to direct preparation of Pt nanocatalysts from oxidative dechloridation of supported H2PtCl6 by oxygen plasma. J. Catal. 2022, 414, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Hu, Z.; Zheng, M.; Lu, H.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, J.; Ji, G.; Cao, J. Formation of Pt nanoparticles in mesoporous silica channels via direct low-temperature decomposition of H2PtCl6·6H2O. Mater. Lett. 2013, 106, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, K.; Routsis, K.; Bett, J. The thermal decomposition of platinum (II) and (IV) complexes. Thermochim. Acta 1974, 10, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Shangguan, W.; Isaacs, M.A.; Durndell, L.J.; Parlett, C.M.A.; Lee, A.F. Photodeposition as a facile route to tunable Pt photocatalysts for hydrogen production: on the role of methanol. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degler, D.; Pereira de Carvalho, H.W.; Kvashnina, K.; Grunwaldt, J.D.; Weimar, U.; Barsan, N. Structure and chemistry of surface-doped Pt:SnO2 gas sensing materials. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 28149–28155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Yuasa, M.; Kida, T.; Yamazoe, N.; Shimanoe, K. High sensitive gas sensor based on Pd-loaded WO3 nanolamellae. Thin Solid Films 2013, 548, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Sun, Y.e.; Jiang, C.; Yao, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. Room-temperature highly sensitive CO gas sensor based on Ag-loaded zinc oxide/molybdenum disulfide ternary nanocomposite and its sensing properties. Sens. Actuators B 2017, 253, 1120–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wu, X.; Han, N.; Chen, Y. Synthesis of Pd-loaded mesoporous SnO2 hollow spheres for highly sensitive and stable methane gas sensors. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 24268–24275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; Mitchell, S.; Mondelli, C.; Jaydev, S.; Perez-Ramirez, J. Unifying views on catalyst deactivation. Nat. Catal. 2022, 5, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, L.; Xue, Y.; Xing, C.; Liu, Y.; Du, Y.; Fang, Y.; Yu, H.; Huang, B.; Li, Y. Highly loaded independent Pt0 atoms on graphdiyne for pH-general methanol oxidation reaction. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2104991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, S.; Siahrostami, S. Noble metal supported hexagonal boron nitride for the oxygen reduction reaction: a DFT study. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sintering temperature, °C | Pt loading method | Chlorine, wt% |

|---|---|---|

| 600 | Solution reduction | 0.167 |

| Impregnation | 0.495 | |

| 825 | Solution reduction | 0.14 |

| Impregnation | 0.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).