Submitted:

16 June 2023

Posted:

19 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

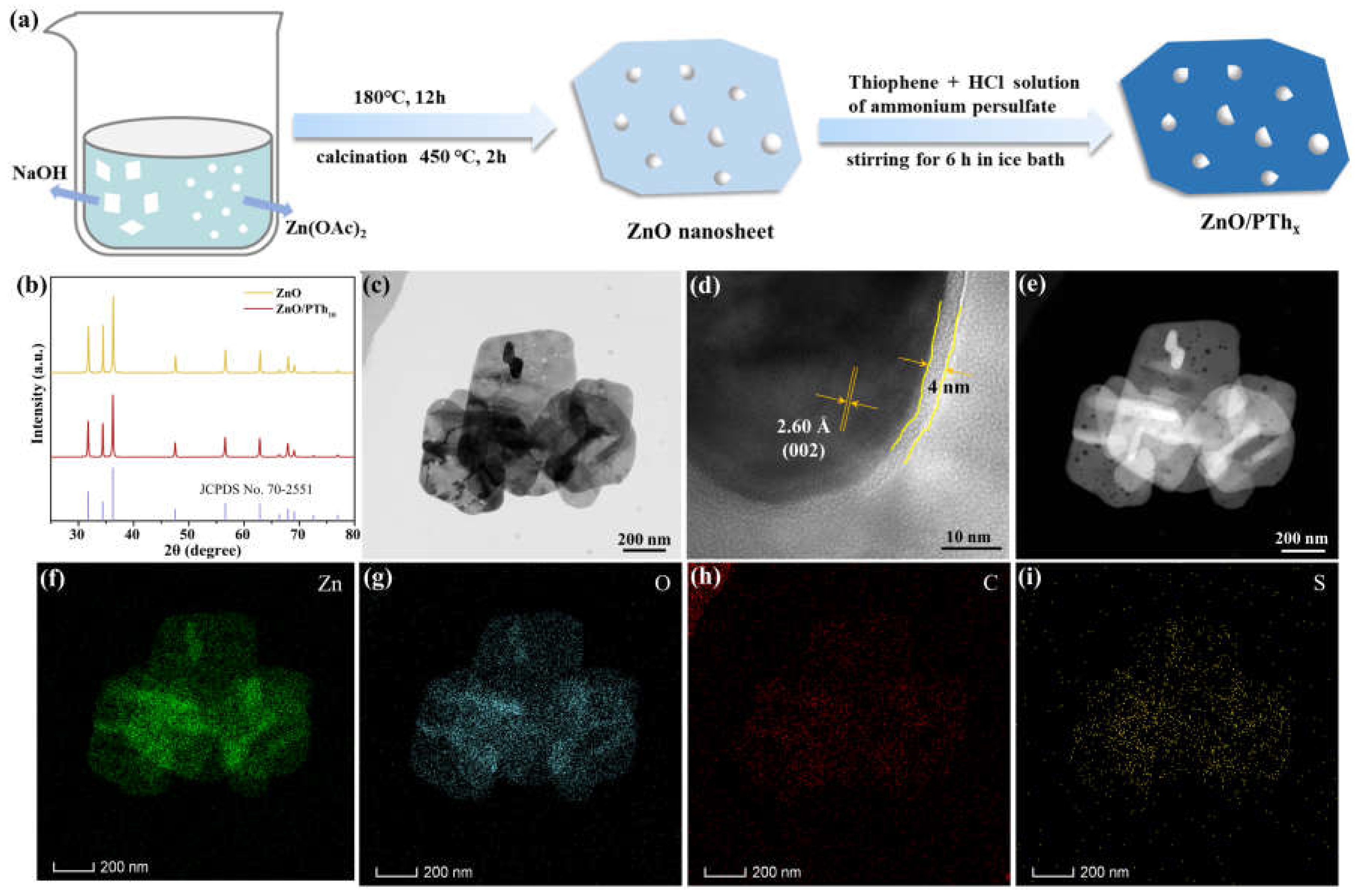

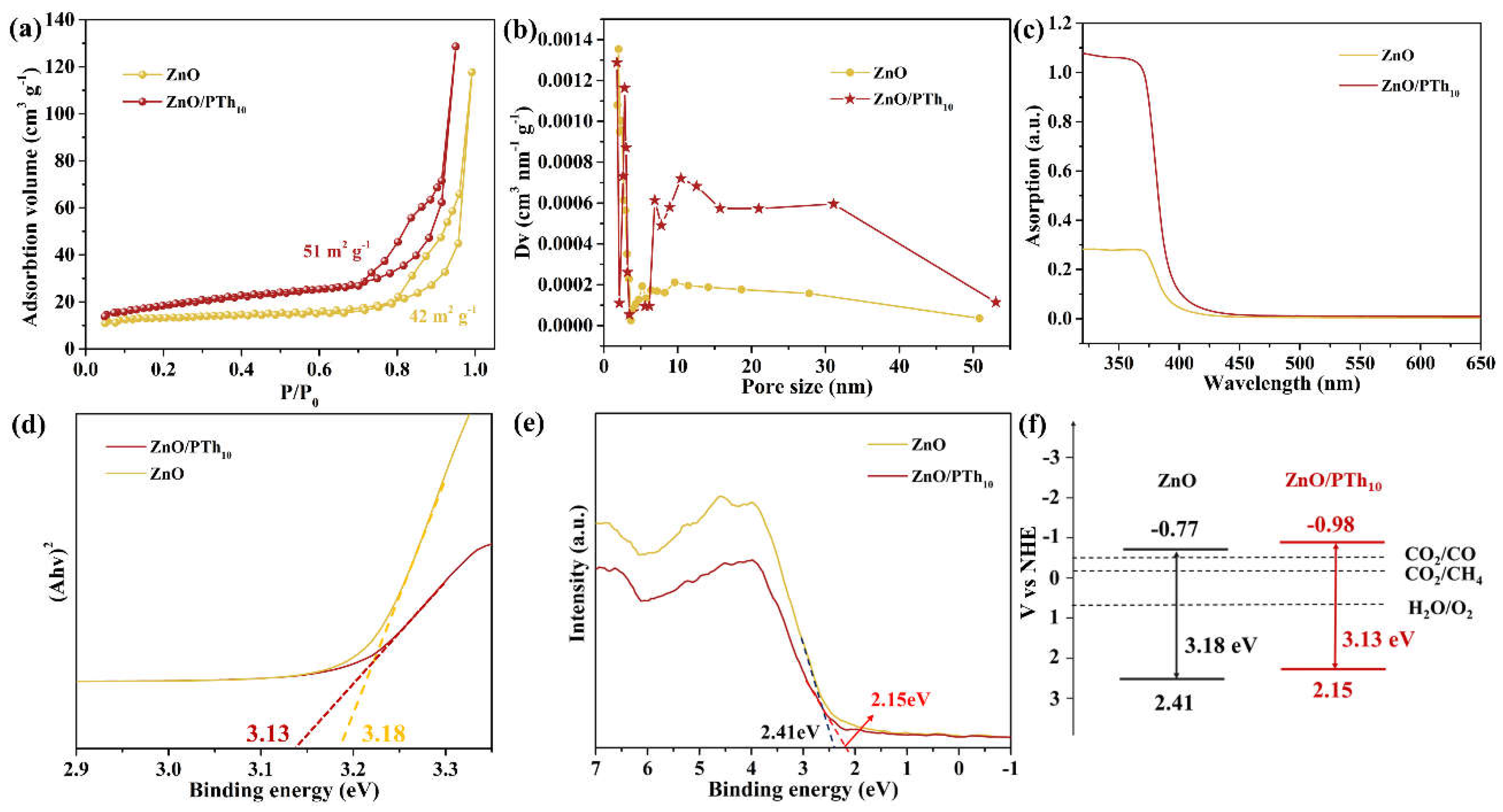

2.1. Photocatalyst Characterization

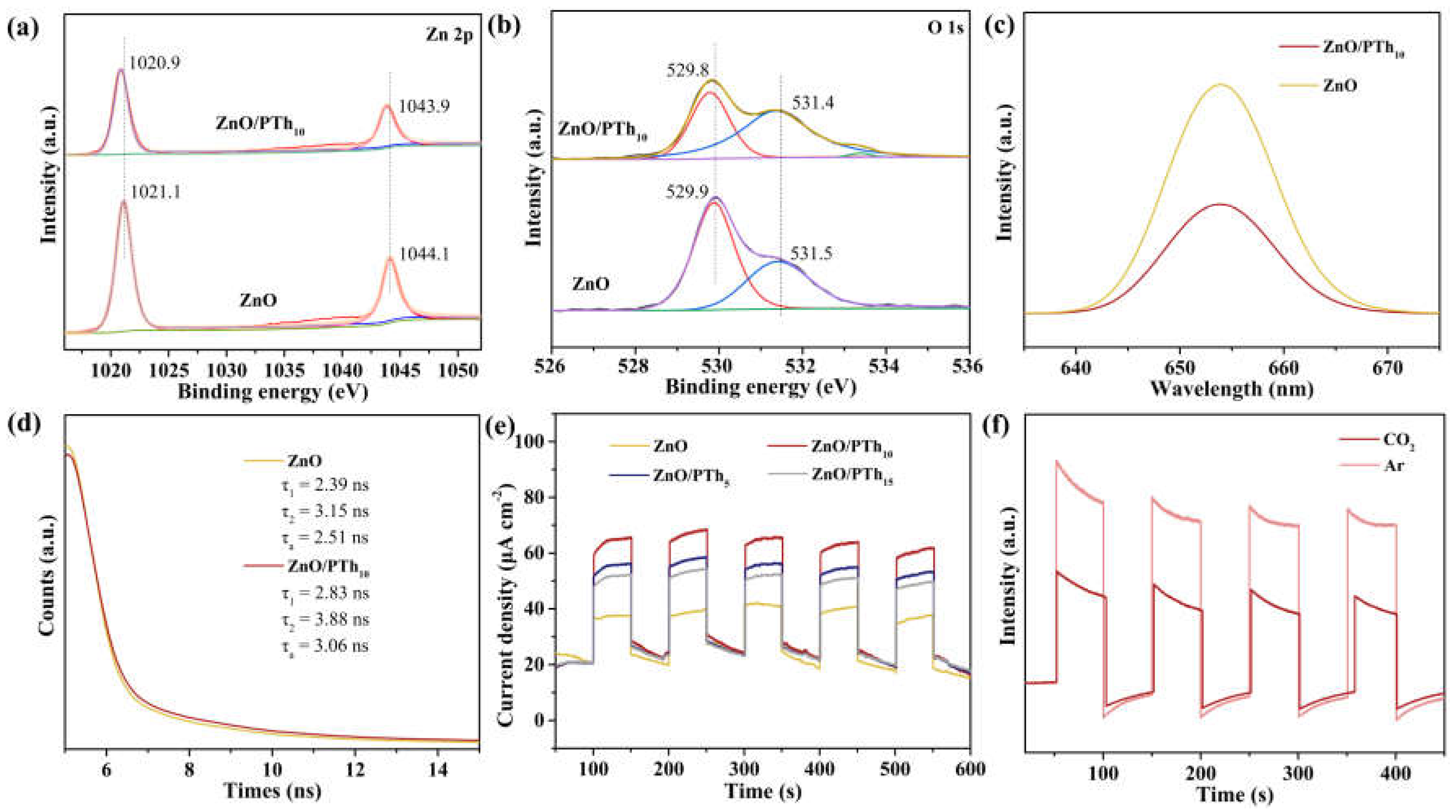

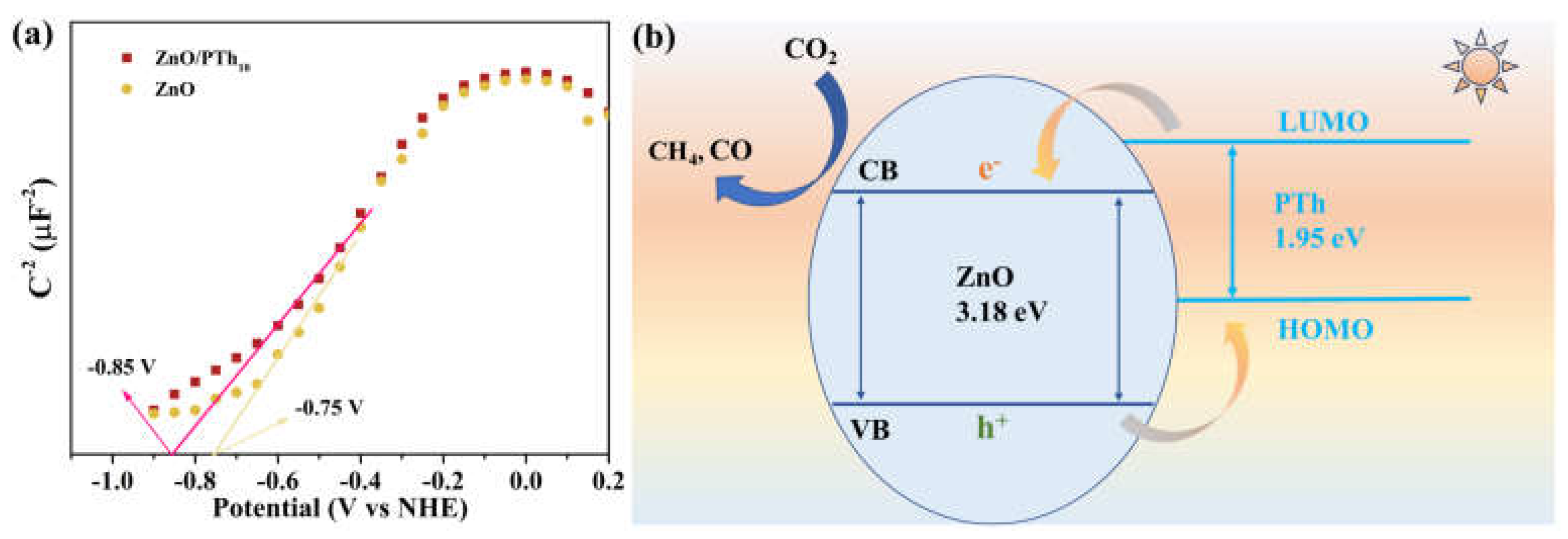

2.2. Efficient Separation of Photogenerated Charges

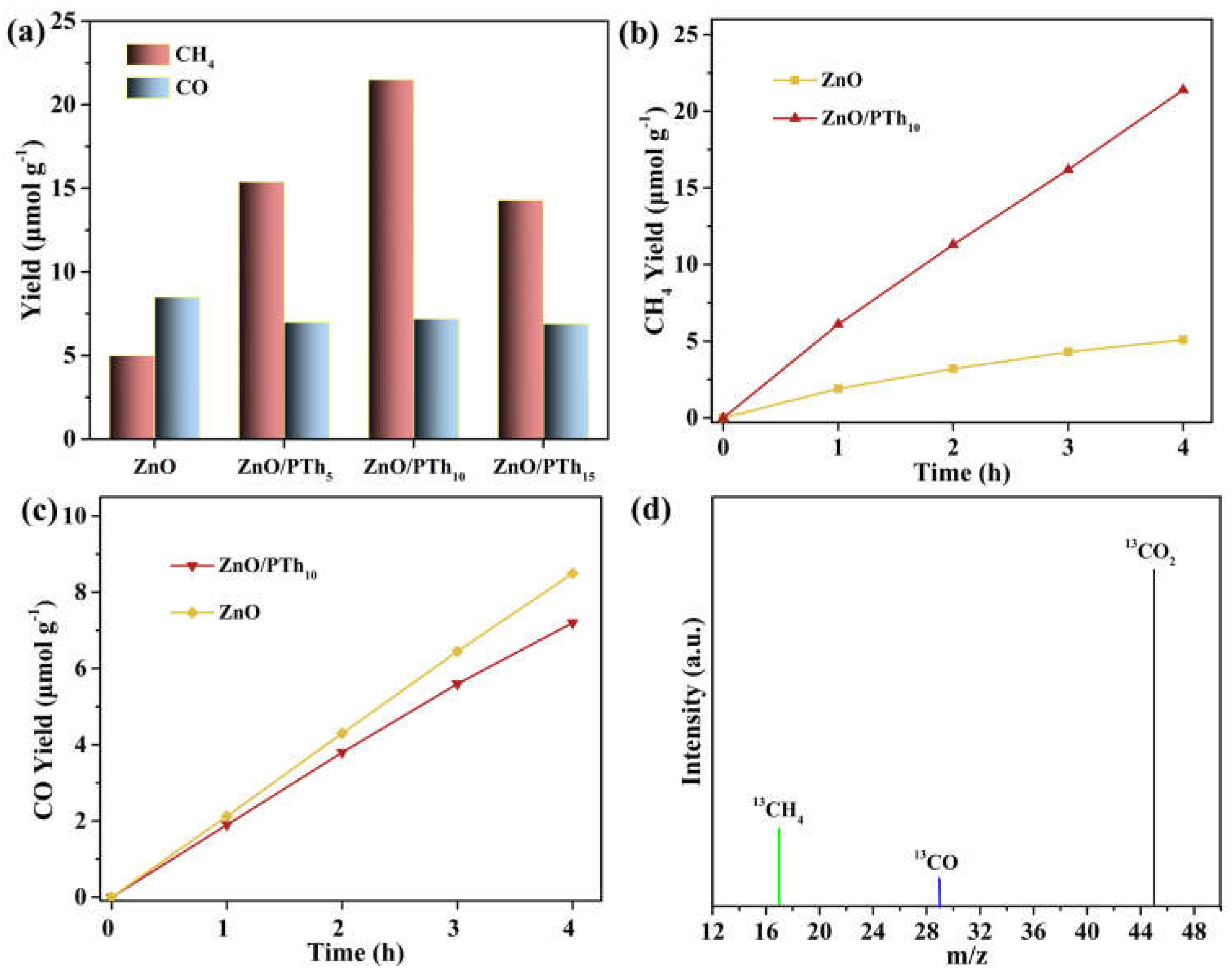

2.3. Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction Activity

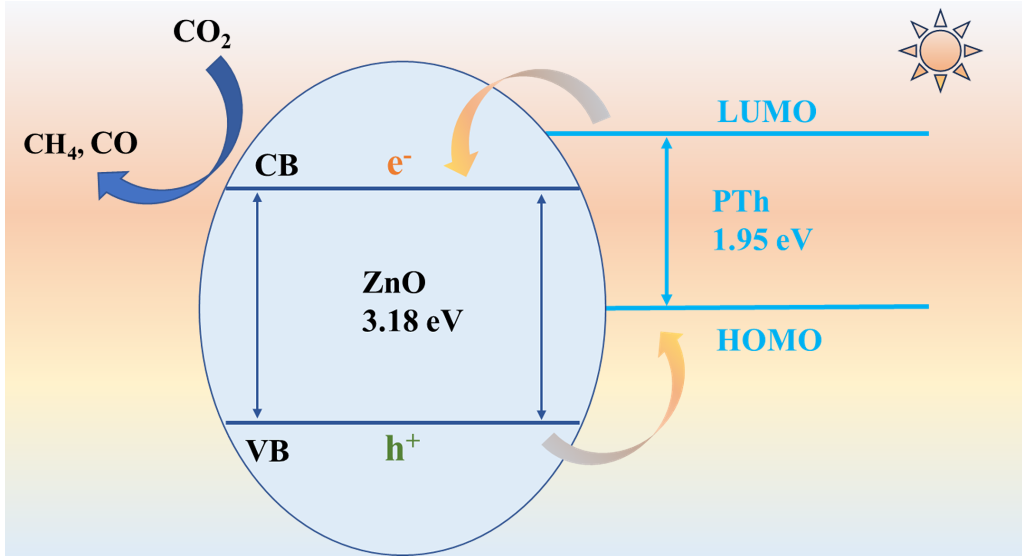

2.4. Photocatalytic Mechanism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials Preparation

3.1.1. Synthesis of ZnO

3.1.2. Preparation of ZnO/PThx

3.2. Characterization

3.3. Photocatalytic Tests

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, R.; Kim, J.; Do, J.Y.; Seo, M.W.; Kang, M. Carbon Dioxide Photoreduction on the Bi2S3/MoS2 Catalyst. Catalysts 2019, 9, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Wang, P.; Long, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, L.; Zou, J.; Luo, X.; Luo, S. Constructing Robust Bi Active Sites In Situ on α-Bi2O3 for Efficient and Selective Photoreduction of CO2 to CH4 via Directional Transfer of Electrons. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 2513–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, S.; Li, L.; Zu, X.; Sun, Y.; Xie, Y. Opportunity of Atomically Thin Two-Dimensional Catalysts for Promoting CO2 Electroreduction. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 2964–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albero, J.; Peng, Y.; García, H. Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction to C2+ Products. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 5734–5749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Long, J.; Tu, L.; Dai, W.; Zou, J.; Luo, X. CoO Engineered Co9S8 Catalyst for CO2 Photoreduction with Accelerated Electron Transfer Endowed by the Built-in Electric Field. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 131849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habisreutinger, S.N.; Schmidt-Mende, L.; Stolarczyk, J.K. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 on TiO2 and other semiconductors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7372–7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, M.T.; Amor, N.; Petru, M. Synthesis and applications of ZnO nanostructures (ZONSs): a review. Crit. Rev. Solid State 2021, 47, 99–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlangu, O.T.; Mamba, G.; Mamba, B.B. A facile synthesis approach for GO-ZnO/PES ultrafiltration mixed matrix photocatalytic membranes for dye removal in water: Leveraging the synergy between photocatalysis and membrane filtration. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosman, N.; Norharyati Wan Salleh, W.; Aqilah Mohd Razali, N.; Nurain Ahmad, S.Z. Ibuprofen removal through photocatalytic filtration using antifouling PVDF- ZnO/Ag2CO3/Ag2O nanocomposite membrane. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 42, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, E.; Amoli-Diva, M. Hybrid adsorption–photocatalysis properties of quaternary magneto-plasmonic ZnO/MWCNTs nanocomposite for applying synergistic photocatalytic removal and membrane filtration in industrial wastewater treatment. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2020, 391, 112359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Lin, S.; Chen, C.; Liang, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, H. A new ZnO/rGO/polyaniline ternary nanocomposite as photocatalyst with improved photocatalytic activity. Mater. Res. Bull. 2016, 83, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakumaran, R.; Boddu, V.; Kumar, M.; Shalaby, M.S.; Abdallah, H.; Chetty, R. Effect of ZnO morphology on GO-ZnO modified polyamide reverse osmosis membranes for desalination. Desalination 2019, 467, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.T.; Vo, T.L.N.; Duong, A.T.; Tran, D.T.; Nguyen, D.L.; Pham, V.V.; Das, R.; Nguyen, H.T. Highly photocatalytic activity of pH-controlled ZnO nanoflakes. Opt. Mater. 2023, 140, 113865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Shi, G. Conducting Polymer-Based Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2868–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.V.; Tran, N.H.T.; Hwang, H.S.; Chang, M. Development strategies of conducting polymer-based electrochemical biosensors for virus biomarkers: Potential for rapid COVID-19 detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 182, 113192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ognibene, G.; Gangemi, C.M.A.; Spitaleri, L.; Gulino, A.; Purrello, R.; Cicala, G.; Fragalà, M.E. Role of the surface composition of the polyethersulfone–TiiP–H2T4 fibers on lead removal: From electrostatic to coordinative binding. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 8023–8033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.Z.; Chen, S.; Quan, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.B. Photonic crystal coupled TiO2/polymer hybrid for efficient photocatalysis under visible light irradiation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3481–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanade, K.G.; Baeg, J.O.K.; Mulik, U.P.; Amalnerkar, D.P. Nano-CdS by polymer-inorganic solid-state reaction: visible light pristine photocatalyst for hydrogen generation. Mater. Res. Bull. 2006, 41, 2219–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Xu, H.; Yu, J.; Hu, X.; Luo, X.; Tu, X.; Yang, L. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 into methanol and ethanol over conducting polymers modified Bi2WO6 microspheres under visible light. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 356, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Goel, N. Photodegradation of dye using Polythiophene/ZnO nanocomposite: A computational approach. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2022, 117, 108285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arul Hency Sheela, J.; Lakshmanan, S.; Manikandan, A.; Arul Antony, S. Structural, Morphological and Optical Properties of ZnO, ZnO:Ni2+ and ZnO:Co2+ Nanostructures by Hydrothermal Process and Their Photocatalytic Activity. J. Inorg. Organomet. P. 2018, 28, 2388–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, X.; Zhu, B.; Wang, J.; Lan, H.; Chen, X. Synthesis of porous ZnS, ZnO and ZnS/ZnO nanosheets and their photocatalytic properties. RCS Adv. 2017, 7, 30956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, S.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F. Improving the photocatalytic performance of conducting polymer polythiophene sensitized TiO2 nanoparticles under sunlight irradiation. Reac. Kinet. Mech. Cat. 2010, 101, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.A. Photoelectrolysis and physical properties of the semiconducting electrode WO3. J. Appl. Phys. 1977, 48, 1914–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Zhang, C.; Shi, T.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Sun, M.; Liu, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gu, X.; Zeng, S. Unraveling the improved CO2 adsorption and COOH* formation over Cu-decorated ZnO nanosheets for CO2 reduction toward CO. Chem Eng J 2023, 452, 139701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byzynski, G.; Melo, G.; Volanti, D.P.; Ferrer, M.M.; Gouveia, A.F.; Ribeiro, C.; Andrés, J.; Longo, E. The interplay between morphology and photocatalytic activity in ZnO and N-doped ZnO crystals. Mater. Design 2017, 120, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.K.; Traeger, F.; Wöll, C.; Idriss, H. Glycine adsorption and photo-reaction over ZnO(000ī) single crystal. Surf. Sci. 2014, 624, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilani, A.; Iqbal, J.; Rafique, S.; Abdel-wahab, M.S.; Jamil, Y.; AlGhamdi, A.A. Morphological, optical and X-ray photoelectron chemical state shift investigations of ZnO thin films. Opt.-Int. J. Light Electron Opt. 2016, 127, 6358–6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jiao, X.; Chen, D.; Li, C.; Zhang, M. Porous Copper/Zinc Bimetallic Oxides Derived from MOFs for Efficient Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 to Methanol. Catalysts 2010, 10, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yang, J.; Yang, K.; Zhu, X.; Zhong, K.; Zhang, M.; Ji. H.; He, M.; Li, H.; Xu, H. Synergistic Effect in Plasmonic CuAu Alloys as Co-Catalyst on SnIn4S8 for Boosted Solar-Driven CO2 Reduction. Catalysts 2020, 12, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu. Y.; Fu, Z.; Cao, S.; Chen, Y.; Fu, W. Highly selective oxidation of sulfides on a CdS/C3N4 catalyst with dioxygen under visible-light irradiation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Wang, T.; Gong, J. CO2 photo-reduction: insights into CO2 activation and reaction on surfaces of photocatalysts. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 2177–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, M.; Augustin, A.; Mohan, S.; Honnappa, B.; Chuaicham, C.; Rajendran, S.; Hoang, T.K.A.; Sasaki, K.; Sekar, K. Conducting polymeric nanocomposites: A review in solar fuel applications. Fuel 2022, 325, 124899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.S.; Olson, D.C.; Kopidakis, N.; Nardes, A.; Ginley, D.S.; Berry, J.J. Control of charge separation by electric field manipulation in polymer-oxide hybrid organic photovoltaic bilayer devices. Phys. Status Solidi A 2010, 207, 1257–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Wang, T.; Gong, J. CO2 photo-reduction: insights into CO2 activation and reaction on surfaces of photocatalysts. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 2177–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).