1. Introduction

COVID-19, a highly contagious disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, is associated with clinical manifestations ranging from asymptomatic to severely diseased states such as pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and acute lung injury (ALI), multi-organ failure and even death. COVID-19 has infected over 600 million people during the pandemic resulting in more than 6 million deaths.

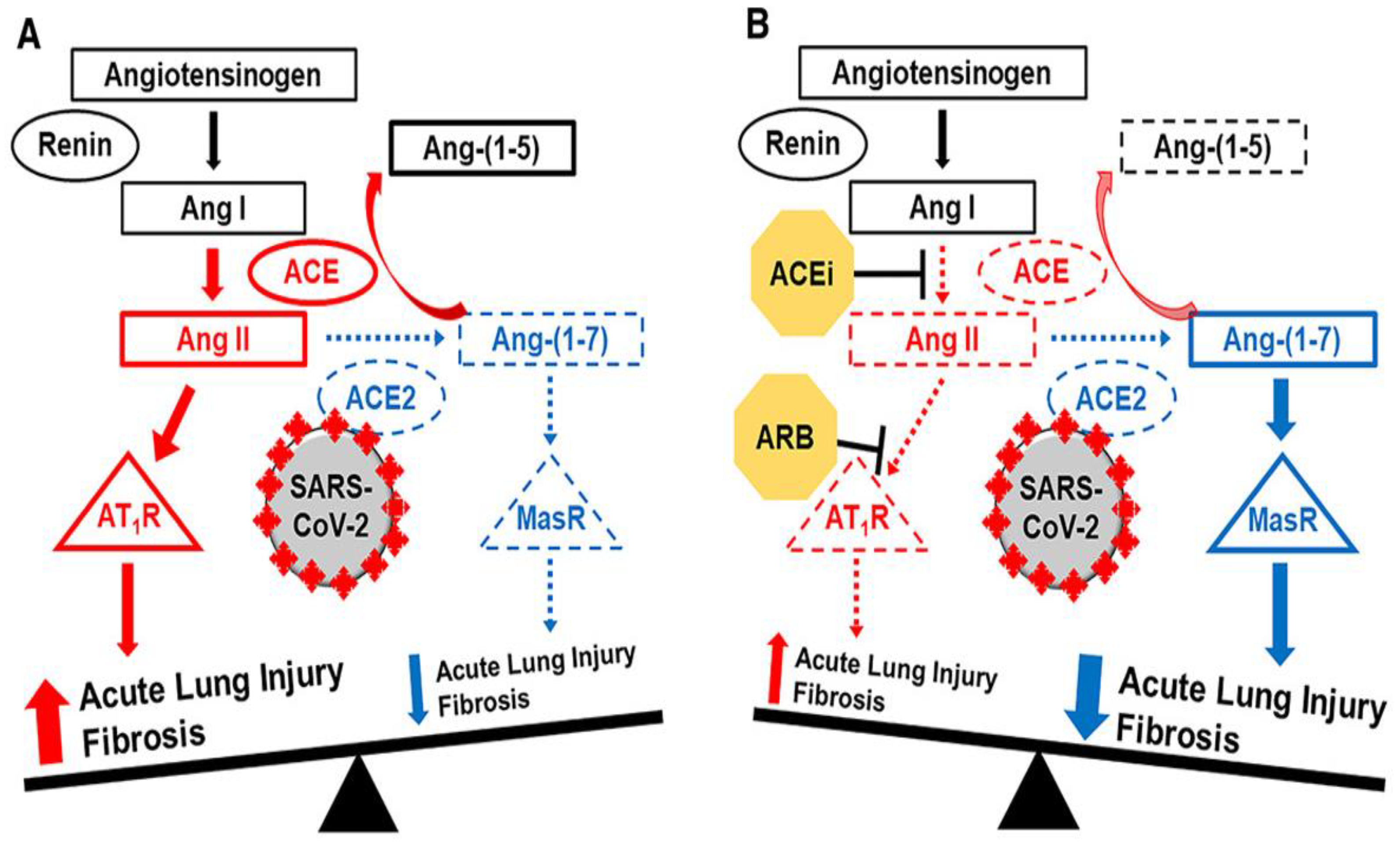

The virus enters the cell by binding viral spike protein (S1) to the epithelial cells’ angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), one of the main components of the Renin-Angiotensin System (RAS) [

1]. ACE2 converts the pro-inflammatory peptide Angiotensin II (Ang II) to the anti-inflammatory peptide Angiotensin 1-7 (Ang 1-7) [

2]. Ang II, initially produced by the enzymatic action of ACE on Ang I, plays a pivotal role in regulating blood pressure, electrolyte and fluid balance and inflammatory pathogenesis. The balance between ACE and ACE2 controls the ratio of Ang II/Ang1-7. The binding of the virus to ACE2 leads to its internalization, causing an imbalance between ACE/ACE2 and consequently resulting in an unopposed Ang II (

Figure 1). This results in the accumulation of Ang II, which activates the angiotensin 1 receptor (AT1R), initiating an inflammatory process that leads to a so-called cytokine storm [

3]. Treatment with ACE inhibitors (ACEi) and Ang II receptor blockers (ARB) may have the potential to prevent and treat ALI and ARDS resulting from COVID-19 infection [

4].

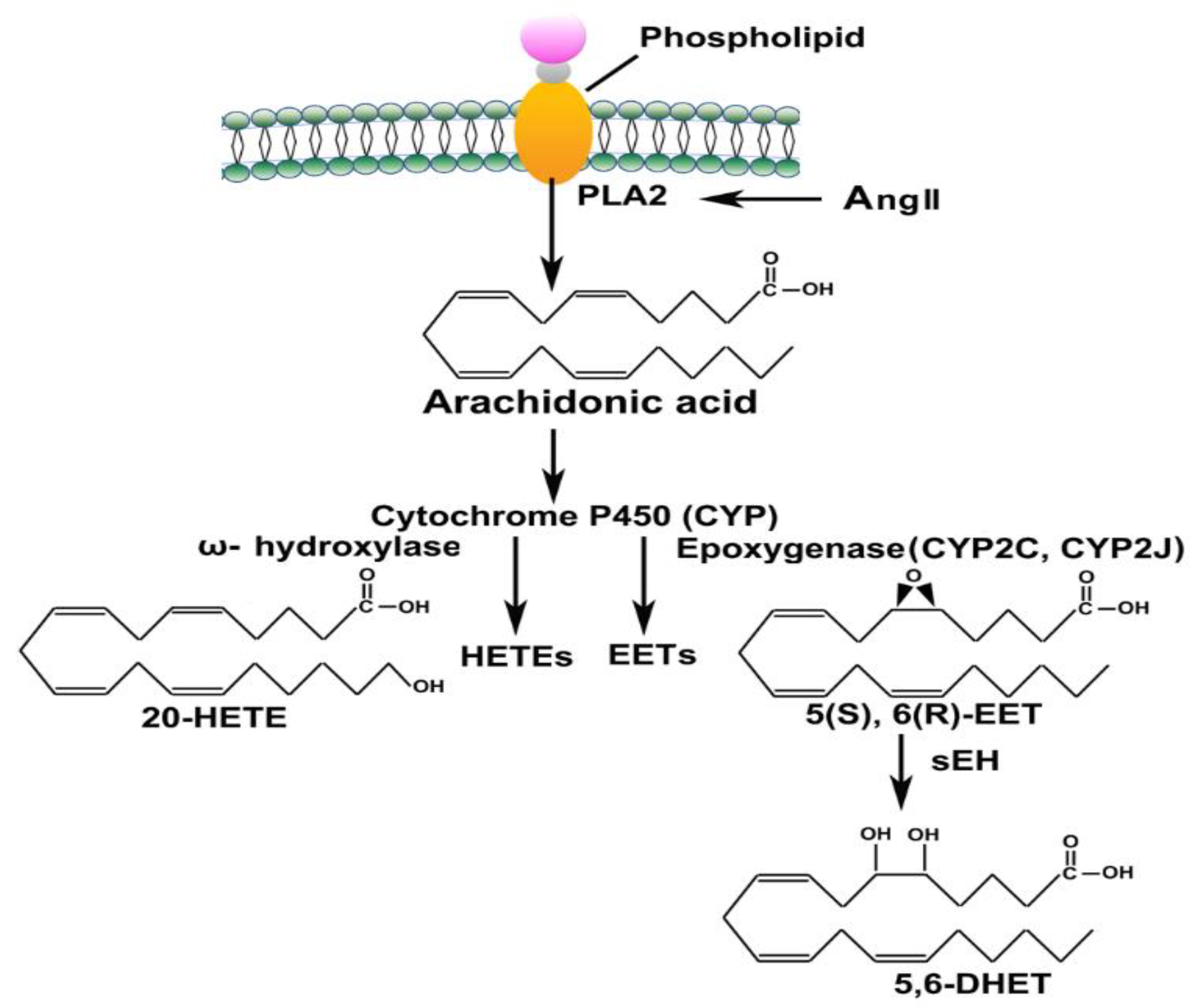

Arachidonic Acid (ArA) is released during an inflammatory response by action of phospholipase 2 (PLA2) and then metabolized by different CYP450 enzymes (ω-hydroxylase and Epoxygenase) to convert into eicosanoids such as hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), respectively (

Figure 2). These eicosanoids function in diverse physiological systems associated with inflammation processes [

5,

6,

7]. For instance, 20-HETE, a potent vasoconstrictor, regulates vascular tone, blood flow to specific organs, and sodium and fluid transport to the kidneys [

8]. EETs act as an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor and present with potent vasodilatory and anti-inflammatory effects [

9].

Like ACE/ACE2 and Ang II/Ang1-7 ratios, the balance between 20-HETE/EETs is critical for the body’s physiological homeostasis. Results from adjuvant arthritis animal studies demonstrate that the RAS and ArA pathways are affected, and the balance between their pro and anti-inflammatory axes is disturbed [

10,

11]. The two pathways are interrelated and directly correlated, demonstrating their significance in the inflammatory response process. Ang II up-regulates phospholipase A, causing ArA release from the cell membrane, propagating the inflammatory cascade furthermore through the ArA pathway [

12]. An imbalance between the vasoconstrictor and vasodilator ArA metabolites occurs due to inflammation impacting the RAS and increasing Ang II levels [

13]. COVID-19’s inflammatory response affects the RAS and ArA pathways [

14]. Given the systemic and local RAS and ArA pathways play essential roles in the homeostasis of vital organs such as lungs, heart, liver, and kidneys, we expect that the understanding and knowledge of the RAS and ArA pathways biomarkers’ status and their association with patient demographic variables (such as gender, age, body mass index (BMI) and underlying co-morbidities) could help physicians to predict future complications in these organs and plan for better intervention.

Gender disparity is one of the unique traits seen in COVID-19 infections. Recent studies have shown that males are more affected by the disease than females, with higher mortality and hospitalization rate [

15,

16]. Although the mechanism for this discrepancy has not been elucidated, recent communication reports attributed it to an infectivity mechanism of COVID-19 involving the ACE2 receptor, Type II transmembrane Serine Protease (TMPRSS 2) and androgen receptor [

17]. TMPRSS 2 is vital in activating viral spike protein, a crucial step in viral entry. The androgen receptor is a known promoter of TMPRSS2 gene expression [

18]. The upregulation of this gene by the androgenic stimulation could explain the higher infectivity in males [

19]. In addition, lesser infectivity in children could be explained by the lower expression of the androgen receptors due to underdeveloped sex organs. The phenomenon has been reported for sex hormones’ influence on ACE2 expression and activity in the mouse adipose tissue, kidneys, and myocardium [

20,

21,

22]. While speculation, it seems reasonable that if the sex hormone modulator 17β-Oestradiol affects the expression and activity of the ACE2 receptor and increases Ang1-7 levels; thus, hormone therapy offers a potential supportive treatment for female COVID-19 patients [

23].

Based on the data provided by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), hospitalization and death increase with age. Compared to the age group of 18-29 years, the hospitalization rate was 5x higher in the 65-74 and 9.1x more in the 75-84 age groups. Similarly, the mortality rate increased by 25x in the 50-64, 65x in the 65-74 and 140x in the 75-84 age groups [

24]. COVID-19 hospitalizations rate could also be correlated with obesity and BMI. A study from Johns Hopkins showed that the hospitalization rate increased in adults with obesity and underweight relative to the normal weight [

25]. Obesity is also linked to impaired immune function and reduction in lung capacity, thereby increasing the risk of infection and impairing ventilation. As reported by CDC, increased BMI could be related to an increased risk of ICU admission, invasive mechanical ventilation and death [

26].

This study aims to analyze the effector RAS peptides (Ang II and Ang 1-7) and relate them with the metabolites of the CYP450-mediated ArA pathway. Additionally, we correlated these metabolites with the demographic variables known to worsen the prognosis of COVID-19 to understand how these variables play a role at the molecular level in the infection. The results of this study help explain how variability in biomarkers combined with individuals’ demographics and co-morbidities correlate with COVID-19 disease intensity. Such knowledge could allow healthcare providers to predict future complications and plan for better interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Ang 1-7 (Anaspec, AS-61039) and Ang II (Anaspec, AS-20633) were purchased from Anaspec Inc. (Fremont, CA, USA). (Asn1, Val5)-Ang II (IS) (Sigma-Aldrich A6402-1MG) was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Waters C18 SPE cartridges (SepPak WAT020805) were purchased from Waters (Milford, MA, USA). The Ara metabolites reference standards were purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI): 19-(R)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (19-HETE) (P/N,10007767), 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) (P/N,90030), (±)-5,6-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (5,6-EET)(P/N,50211), (±)8,9-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (8,9-EET) (P/N,50351), (±)11,12-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (11,12-EET)(P/N,50511), (±)14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid (14,15-EET) (P/N,50651), (±)-5,6-dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid (5,6-DHET) (P/N, 51211), (±)8,9-dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid (8,9-DiHT)(P/N,51351), (±)11,12-dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid (11,12-DHET) (P/N,51511), and (±)14,15-dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid (14,15-DHET) (P/N,51651). Additionally, the following deuterated internal standards (IS) were also obtained from Cayman: 8,9-EET-d11(deuterium atoms at the 16,16,17,17,18,18,19,19,20,20, and 20 positions; isotopic purity of ≥ 99%). LC-MS grade water, acetonitrile, and formic acid were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA).

2.2. LC-MS/MS system

LC-MS/MS system comprised of liquid chromatography (Shimadzu, MD, USA) with a binary pump (LC-30AD), an autosampler (SIL-30AC), a controller (CBM-20A), a degasser (DGU-20A5R), a column oven (CTO-20A) and an ABSciex QTRAP 5500 mass spectrometer (SCIEX, Foster City, CA, USA) with electron spray ionization (ESI) source. The chromatograms were monitored using Analyst 1.7 software, and the data were analyzed in MultiQuant 3.0 software (SCIEX, Foster City, CA, USA). The analytes were separated using Synergi™ Fusion-RP column (2.5 µm, 100 x 2 mm) obtained from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA, USA). All the analyses were done in positive ion mode.

2.3. Human subject

The Institutional Review Board approved this study through the IRB-FY2020-273 protocol to analyze de-identified COVID-19 patients’ plasma samples that he will receive from Dr. Elizabeth Middleton, University of Utah, under a signed Material Transfer Agreement. The University of Utah IRB also reviewed and approved all study recruitment materials, educational information, participant instructions for self-collection of specimens, surveys, and the informed consent documents (IRB-00102638) and (IRB-00093575).

The University of Utah research group inclusion criteria for healthy volunteers were: consenting male and female subjects of any self-identified race/ethnicity without acute or chronic illnesses aged 18 and older, and exclusion criteria were the use of any prescription medication, pregnancy, suffering from any acute or chronic medical condition or disease, been hospitalized or had surgery within the preceding 6 weeks or have any prior history of stroke. The inclusion criteria for COVID patients were; ICU admission with confirmed infection and organ dysfunction as defined by a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) ≥ 2 above baseline (if baseline data is unavailable, baseline SOFA is assumed to be 0). All patients have been enrolled in the study within 72 hours of ICU admission. Additionally, individuals diagnosed with COVID and hospitalized with acute COVID infection were enrolled in the study. The exclusion criteria were; admission to the ICU for longer than 72 hours, hemoglobin level < 7gm/dl or clinically significant bleeding.

After the patient has met inclusion criteria and no exclusion criteria are indicated, subjects provide consent using approved IRB protocols. Once subjects have consented, a whole blood sample is drawn within 48 (± 24) hours (study day 0) of a COVID-19 diagnosis. Antiquated blood samples were mixed with a protease inhibitor cocktail solution containing 1.0 mM p-hydroxy mercury benzoate, 30 mM 1,10-phenanthroline, 1.0 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 1.0 mM Pepstatin A and 7.5% EDTA (all from Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and treated with 1% Triton X (to inactivate the virus). Plasma was harvested after centrifugation for 10 min at 2500×g and 4 °C and stored at − 80 °C until assayed.

2.4. Sample preparation procedures

2.4.1. Solid-phase extraction (SPE)

Angiotensin peptides (Ang 1-7 and Ang II) were extracted from the plasma samples using solid phase extraction (SPE). SPE was carried out based on a previously established method by Cui et al. with minor changes in the process [

27]. Briefly, 200 μL of plasma samples were mixed with 100 μL of the internal standard (50 ng/mL). Then, 1.5 μL of formic Acid was added to make the final concentration of 0.5%. The samples were mixed and loaded onto the Waters C18 SPE cartridges previously preconditioned with 3 ml ethanol and 3 ml deionized water. Samples were then loaded onto the cartridge and allowed to interact with the column by application of a positive nitrogen flow from a positive pressure manifold (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). It was then washed with 3 mL of deionized water and eluted with 3 mL of methanol containing 5% formic acid. The eluted solutions were collected and dried using a Savant 200 SpeedVac system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The dried samples were reconstituted in 100 µL of acidified water containing 0.1% formic acid, and 10 µL of samples were injected into the LC-MS/MS to quantify the Ang peptides concentrations.

2.4.2. Liquid-liquid extraction (LLE)

A liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) method using ethyl acetate was utilized to extract the ArA metabolites from the plasma samples. This method was previously validated in our lab [

28]. Briefly, 300 µL of plasma sample was mixed with 100 µL of 10,11-EET d11 (IS, 100 ng/mL), and 2 µL of FA was added. The samples were vortexed, and 500 µL of ethyl acetate was added. The resulting biphasic solutions were mixed thoroughly by vortexing for 1 minute and centrifuged at 15,000×g, 4°C, for 15 mins. After centrifugation, 400 µL of the supernatant layer was taken, and for a second extraction step, 500 µL of the ethyl acetate was added again. The organic supernatant phase was mixed with the previous step extract, dried under nitrogen gas, and reconstituted in methanol for LC-MS/MS analysis. 30 µL of the sample was injected into the LC-MS/MS.

2.4.3. LC-MS/MS method for Ang peptides

The patients’ plasma samples were analyzed for Ang 1-7 and Ang II levels by the published LC-MS/MS method [

28]. The method was applied for plasma sample analysis after minor modification and validation. Ang peptides were separated by Synergi RP (2 X 100 mm) column with a 2.5 μm particle size (Phenomenex, CA, USA) at ambient temperature. The mobile phase comprised 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and ACN (B).

The gradient time program started from 5% ACN to 30% ACN over 4 min, and the composition was kept constant for 4 to 8 min, lowered to 5% ACN for 9 min, and ran for 10 min. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min, and the injection volume was 30 μL. Electrospray ionization was used, and analytes were detected using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) in the positive mode. The optimized source/gas parameters were as follows: curtain gas, 30; collision gas, medium; ion spray voltage, 5500 V; temperature, 300 °C; ion source gas 1 (nebulizer gas), 20 psi; and ion source gas 2 (turbo gas), 25 psi. LC-MS analysis was performed with the single ion recording (SIR) mode, in which the m/z 300.5, 349.6, and 516.6 were used for Ang 1-7, Ang II, and IS, respectively. LC-MS/MS was performed with MRM transitions of m/z 300.6→136 (Ang 1-7), m/z 349.6→136 (Ang II), and m/z 516→769.4 (IS).

2.4.4. LC-MS/MS method for ArA metabolites

The experimental protocol and assay condition were followed with slight optimization to analyze ArA metabolites as previously described [

28]. Briefly, eicosanoids were separated using a Synergi RP (2 x 100 mm) column with a 2.5 μm particle size (Phenomenex, CA, USA) at ambient temperature. The mobile phase comprised 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and CAN (B). The mobile phase gradient time program started from 5% ACN to 20% ACN over 2 min, then increased to 55% ACN, kept constant for 2.5 to 6 min, increased to 100% ACN to 8 min, and ran until 9 min. Then, it was subsequently reduced to 5% of ACN over a 10.5 min total run. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min, and the injection volume was 10 μL. The mass spectrometric condition consists of a triple quadrupole that monitors the

m/z transitions by Analyst software. The electrospray ionization technique was used, and analytes’ ion fragments were detected using MRM in the negative mode. The optimized source/gas parameters were as follows: curtain gas, 20 psi; collision gas, medium; ion spray voltage, ~4500 V; temperature, 400 °C; ion source gas 1 (nebulizer gas), 20 psi; and the ion source gas 2 (turbo gas), 25 psi.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Patients’ demographic data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The biomarkers data are expressed as mean ± standard error of means (SEM) and analyzed by a standard computer program, GraphPad Prism Software PC software, version 9.3.1, and Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The plasma concentrations of some of the ArA metabolites in some patients were lower than the detection limit; therefore, those patients were excluded in the statistical comparison case by case. Data were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and homogeneity of variance using Levene’s test before proceeding with the non-parametric statistical tests. Group comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney U test, and the correlation for the continuous variables was analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The confidence interval was set at 95%, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

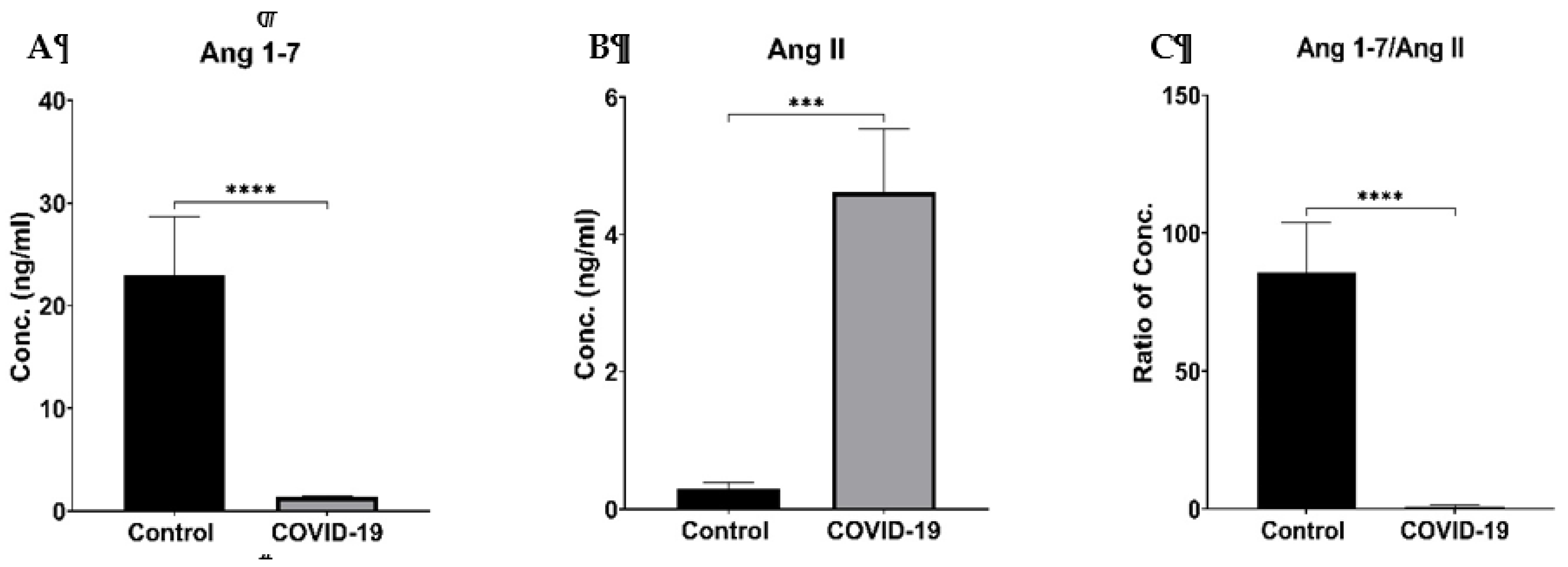

In this study, we evaluated and compared the RAS components (Ang1-7, Ang II plasma levels, Ang1-7/Ang II ratio) and ArA metabolites (HETEs, EETs and DHETs) between healthy controls and COVID-19 patients to determine whether the RAS axes were unbalanced in COVID-19 patients and impacted on the ArA pathway and its metabolites profiles.

Our results indicate that Ang1-7 levels were significantly lower, whereas Ang II levels were prominently higher in the COVID-19 patients than in the healthy control individuals (

Figure 3 and

Table 2). The ratio of Ang1-7/Ang II as an indicator of the balance between the RAS classical and protective arms was dramatically lower in COVID-19 patients. Such imbalance is attributed to the deactivation of the ACE2 enzyme by the SARS-CoV-2 virus and corresponded with measured higher Ang II plasma levels in these patients. It is worth mentioning the observed results indicate that both arms of the RAS are affected by this viral infection. The binding of the virus to ACE2 leads to its down-regulation, causing an imbalance between ACE/ACE2 and consequently resulting in a lower Ang1-7/Ang II ratio and a surge of an unopposed Ang II and cytokine storm to impose tissue injury depicted in

Figure 1, signifying the lung as a typically impacted primary tissue by the virus. The RAS is closely linked to cardiovascular function, and its dysregulation in COVID-19 can have cardiovascular implications. Ang II can promote vasoconstriction, oxidative stress, and prothrombotic effects, increasing the risk of cardiovascular complications reported in infected individuals. The inflammatory response triggered by the dysregulated RAS can damage endothelial cells, disrupt the integrity of blood vessels, and contribute to cardiovascular dysfunction. Such phenomenon has been supported by an animal model of arthritis, where an imbalance of the cardiac and renal RAS components explains the cardio-renal toxicity [

10]. Treatment with ACE inhibitors (ACEi) and Ang II receptor blockers (ARB), which are commonly used to manage hypertension, could be beneficial in COVID-19 by potentially mitigating the harmful effects of an imbalanced RAS [

29]. However, more research is needed to fully understand the complex interactions between RAS and COVID-19 and determine the optimal therapeutic approaches.

We also observed that in COVID-19 patients, there was no significant increase in inflammatory 19-HETE and 20-HETE—however, there was a remarkable change in anti-inflammatory EETs and DHETs profiles (

Table 2). The level of EETs was dramatically increased in COVID-19 patients, whereas the DHETs concentration was repressed. ArA metabolism is a complex process involving several enzymes, including CYP450 enzymes, which play a role in converting ArA into various bioactive metabolites, such as HETEs, EETs and DHETs. Research on the specific impacts of COVID-19 on ArA metabolites through CYP enzymes is limited; however, it is known that COVID-19 can lead to a dysregulated immune response and excessive inflammation in some individuals. Inflammatory processes, including the production of ArA metabolites, are tightly regulated by various factors, such as cytokines and other inflammatory mediators. It is plausible that COVID-19-induced inflammation could indirectly impact the ArA pathway by altering the expression or activity of enzymes involved in its metabolism, including CYP enzymes. It has been reported that CYP enzyme expression was affected by the excessive inflammatory response due to COVID-19 viral infection [

30]. For example, CYP4A1 and CYP4A2 enzymes convert ArA to HETEs and promote the expression of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules [

31].

Furthermore, the CYP epoxygenase enzyme families of CYP2C and CYP2J generate EETs from ArA, resulting in anti-inflammation, vasodilation, and proangiogenic effects [

32]. Multiple studies demonstrated that both EETs and HETEs play a role in lung and kidney injury [

33,

34,

35]. These reports suggested that the dysregulation of these enzymes may contribute to the inflammatory response observed in COVID-19 patients. In the current study, the observed increase in EETs and decrease in DHETs levels could be attributed to the body’s defense mechanism in resolving the inflammation by up-regulation of CYP epoxygenase enzymes and down-regulation of the sEH. It is possible that other enzymatic mechanisms could also be responsible for this phenomenon, and the proposed claim needs further investigation to be confirmed.

Evidence elucidates that the cross-talk between the RAS and CYP-mediated ArA pathway can significantly affect inflammatory disease manifestations [

11] and explain vascular complications observed in COVID-19 patients. A possible link between ArA metabolites level and ACE enzyme induction has been reported [

36]. Consequently, the elevated 20-HETE level and low EETs plasma concentrations in patients associated with renal and vascular complications were correlated with plasma renin activity [

37]. Additionally, investigation of the association between 20-HETE and the RAS components in the rat has shown similar patterns on increased blood pressure and over-expression of CYP4A2 cDNA, which was normalized by the administration of lisinopril, losartan, or a 20-HETE antagonist [

38]. The different results on the ArA metabolites observed in this study could be explained by the activation of AT2R by the high concentration of Ang II in COVID-19 patients. It has been reported that AT2R activation favors EETs production, inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokine intracellular signaling [

39], and probably helps patients to recover from this viral infection. The anti-inflammatory effects of direct AT2R stimulation have been reported using selective peptide [

40] and nonpeptide [

41] AT2R agonists. These anti-inflammatory effects do not counteract Ang II-induced, AT1R-mediated pro-inflammatory actions. AT2R- stimulation antagonizes the effects of TNF-α or other non-RAS stimuli, such as growth factors and has been reported previously [

42,

43,

44]. The Ang II signaling through AT2R activation seems to interfere with other non-RAS signaling cascades coupled with harmful stimuli, and ARBs seem unable to block cytokine-induced IL-6 expression [

45]. AT2R stimulation reduces TNF-α–induced IL-6 expression by activating protein phosphatases, increasing EETs synthesis and inhibiting NF-κB activity [

39]. The observed higher concentration of Ang II in COVID-19 patients due to internalization and inactivation of the ACE 2 could explain the elevated EETs levels and their positive correlation with Ang II levels (

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6). Previous reports on the protective effects of AT2R in other inflammatory conditions support this finding [

46,

47].

Additionally, it has been reported that in an

in vitro study, Ang 1-7, through activation of the Mas receptor, increased the release of ArA, which the Mas antagonist abolished. Neither AT1R nor AT2R antagonists could block this effect [

48]. The current studies observed a negative trend of correlations between EETs and Ang1-7 or Ang1-7/Ang II in COVID-19 patients are in concert with that report (

Table 3 and

Table 5).

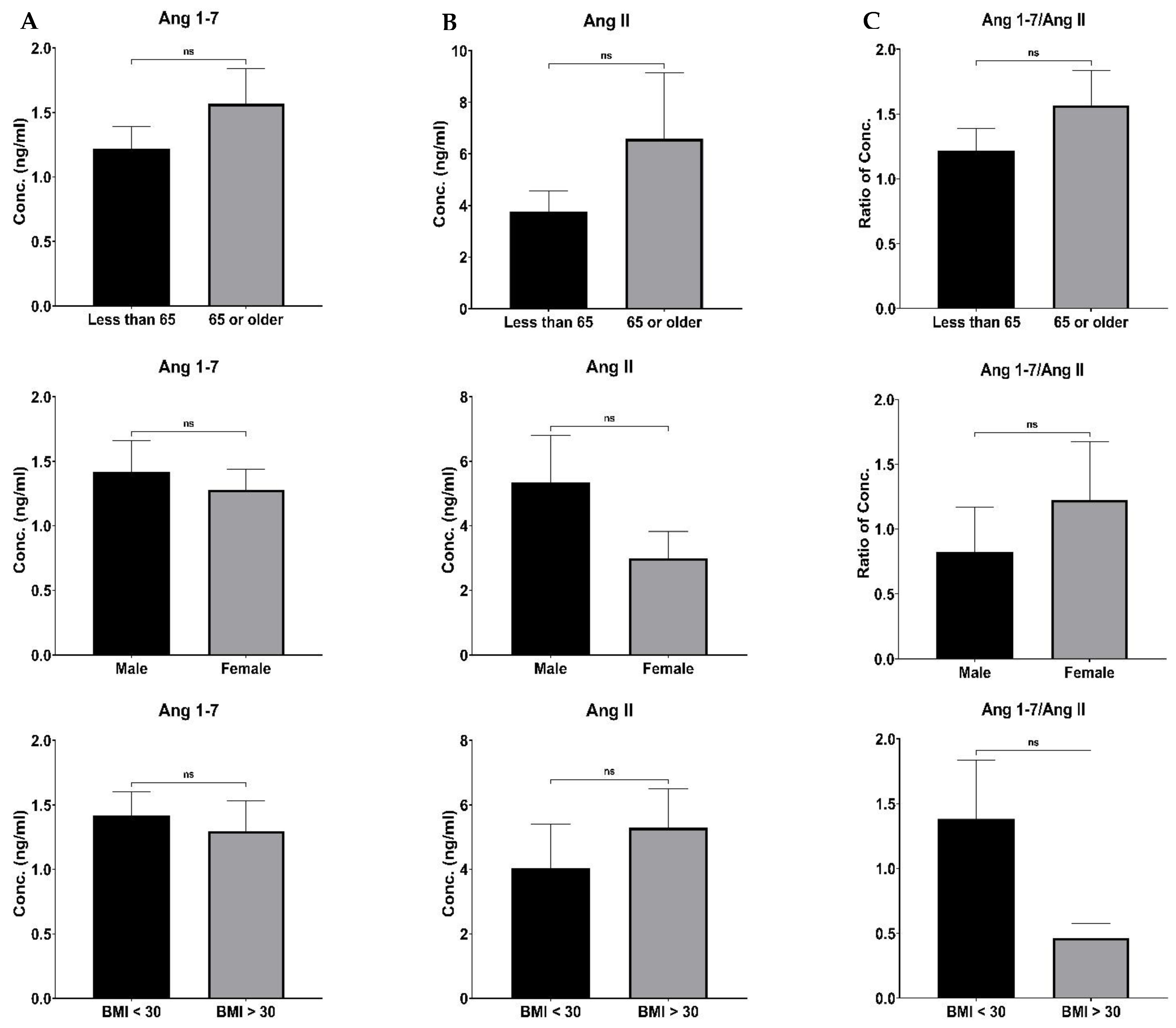

Although there were differences in the RAS component and ArA metabolites levels based on age, sex, BMI and co-morbidities, such distinctions did not reach a significant level (Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The lack of detection of such differences could be related to our study’s limitation on enrolling a small number of patients. It is most likely that such a distinction could be made in more extensive studies.

It has been reported that the SOFA score can be used as a tool in combination with other disease severity scores in predicting mortality in COVID-19 patients [

49]. Our observed association can explain the potential and positive correlation of the SOFA score with Ang II, 19- and total HETE and DHET, indicating that these RAS components and ArA metabolites directly or indirectly impact COVID-19 patients’ organ function.

Limitations

One significant limitation of this study was the small number of patients, limiting its potential for generalizability. This study’s findings and conclusions may not apply to a larger population or diverse demographics, as the sample size may not adequately represent the variations and complexities present in the broader population. However, increasing the study’s statistical power by enrolling a larger population could enhance the ability to detect significant correlations accurately, as some trends have already been seen.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.-H. and MN; methodology, A.A.-H. and BG; validation, A.A.-H. and BG; formal analysis, A.A.-H., BG, and SK..P; investigation, A.A.-H., and BG; resources, A.A.-H., EM and RAC; data curation, A.A.-H. and BG; writing—original draft preparation, BG and A.A.-H.; writing—review and editing, A.A.-H. and BG; visualization, A.A.-H. and BG; supervision, A.A.-H.; project administration, A.A.-H.; funding acquisition, A.A.-H. and MN All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.