Submitted:

16 June 2023

Posted:

16 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

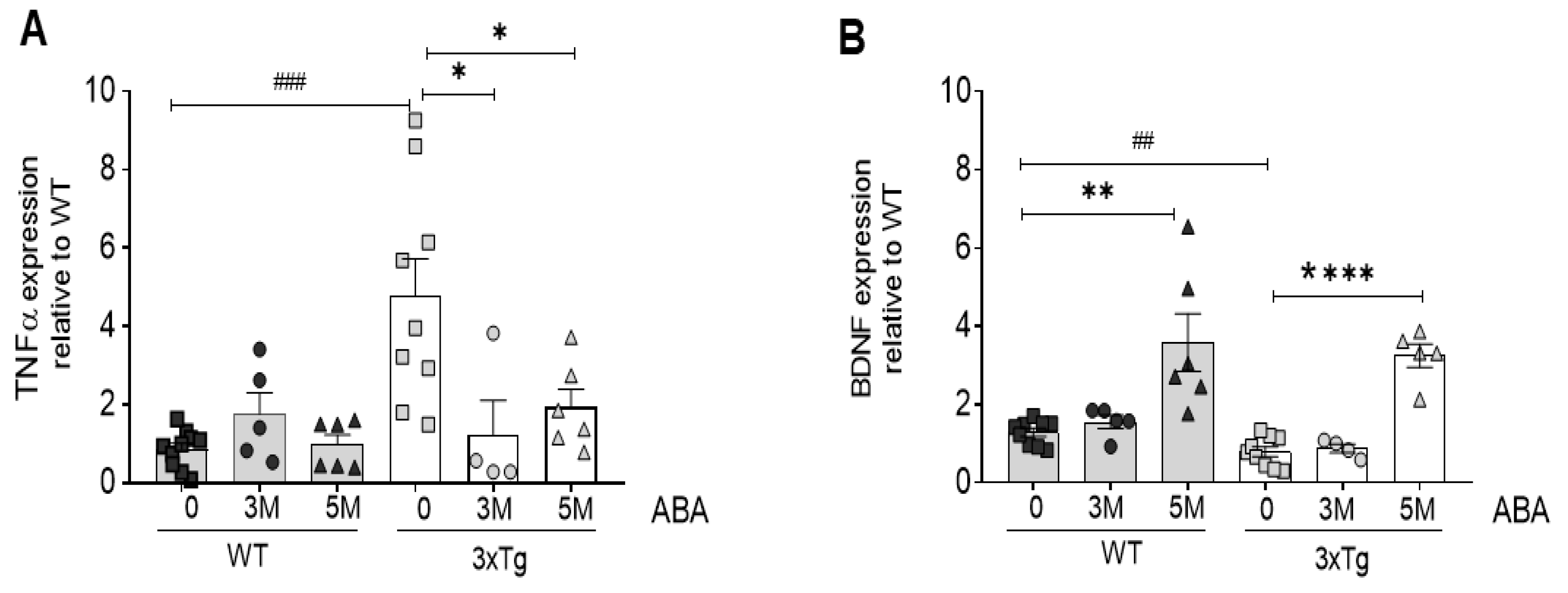

2.1. ABA Treatment Reduces Inflammatory Cytokine TNFα While Increasing BDNF mRNA Expression in Hippocampi of Triple-Transgenic Mice

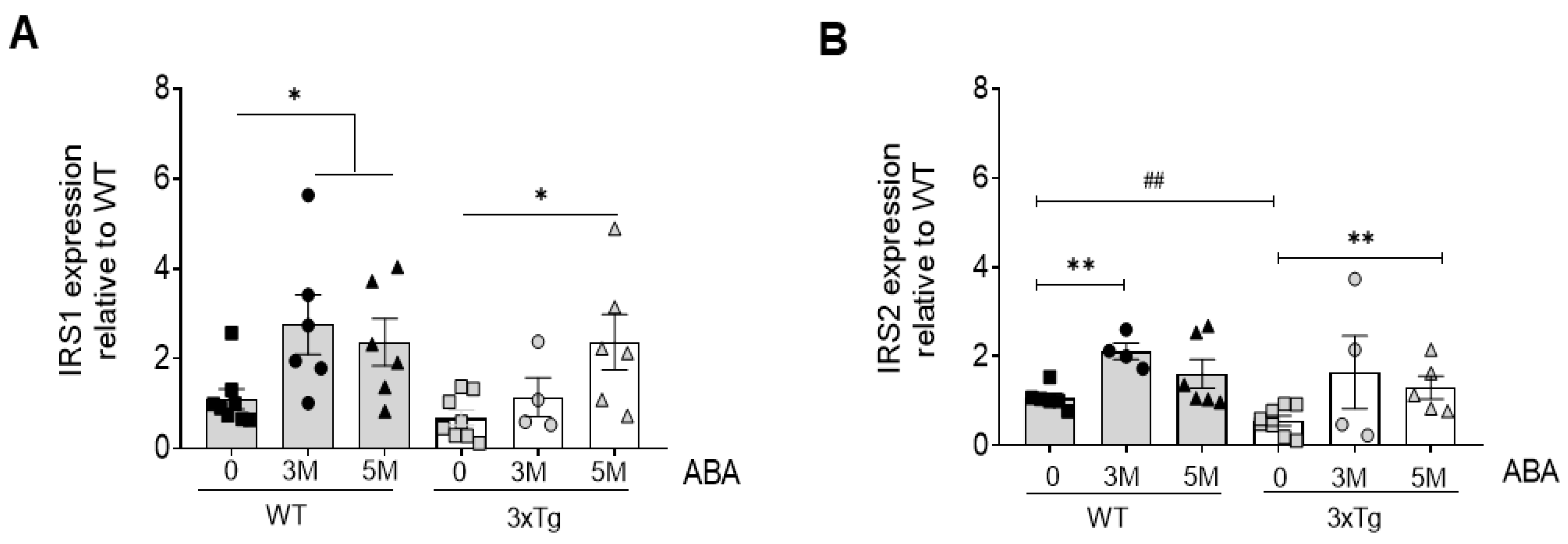

2.2. ABA Treatment Increases mRNA Levels of Insulin Substrate Receptors 1 and 2 (IRS1/2)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mice and Treatment

4.2. RNA Extraction and Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

4.3. Statistics

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beason-Held, L.L.; Goh, J.O.; An, Y.; Kraut, M.A.; O’Brien, R.J.; Ferrucci, L.; Resnick, S.M. Changes in Brain Function Occur Years before the Onset of Cognitive Impairment. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 18008–18014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinuesa, A.; Pomilio, C.; Gregosa, A.; Bentivegna, M.; Presa, J.; Bellotto, M.; Saravia, F.; Beauquis, J. Inflammation and Insulin Resistance as Risk Factors and Potential Therapeutic Targets for Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 653651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlanga-Acosta, J.; Guillén-Nieto, G.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, N.; Bringas-Vega, M.L.; García-del-Barco-Herrera, D.; Berlanga-Saez, J.O.; García-Ojalvo, A.; Valdés-Sosa, M.J.; Valdés-Sosa, P.A. Insulin Resistance at the Crossroad of Alzheimer Disease Pathology: A Review. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 560375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Li, F.; Jia, L.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wei, Y.; Li, Y.; Jin, H.; Jia, J. Phosphorylated Tau 181 Serum Levels Predict Alzheimer’s Disease in the Preclinical Stage. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 900773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sarasúa, S.; Moustafa, S.; García-Avilés, Á.; López-Climent, M.F.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Olucha-Bordonau, F.E.; Sánchez-Pérez, A.M. The Effect of Abscisic Acid Chronic Treatment on Neuroinflammatory Markers and Memory in a Rat Model of High-Fat Diet Induced Neuroinflammation. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, A.M.; Griffin, R.J.; Timmons, S.; O’Connor, R.; Ravid, R.; O’Neill, C. Defects in IGF-1 Receptor, Insulin Receptor and IRS-1/2 in Alzheimer’s Disease Indicate Possible Resistance to IGF-1 and Insulin Signalling. Neurobiol. Aging 2010, 31, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, E.; Terry, B.M.; Rivera, E.J.; Cannon, J.L.; Neely, T.R.; Tavares, R.; Xu, X.J.; Wands, J.R.; De La Monte, S.M. Impaired Insulin and Insulin-like Growth Factor Expression and Signaling Mechanisms in Alzheimer’s Disease—Is This Type 3 Diabetes? J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2005, 7, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.K.; Chakrabarti, S.K.; Zulkipli, I.N.; Hamid, M.R.W.A. Curcumin Ameliorates the Impaired Insulin Signaling Involved in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease in Rats. J. Alzheimers. Dis. Rep. 2019, 3, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelmann, E.; Leßmann, V.; Brigadski, T. Pre- and Postsynaptic Twists in BDNF Secretion and Action in Synaptic Plasticity. Neuropharmacology 2014, 76 (Pt. C), 610–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosaie, F.; Mohammadi, S.; Saghazadeh, A.; Dehghani, F.; Id, N.R. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Diabetes Mellitus : A Systematic Review and Meta- Analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0268816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G.A.; O’Connor, J.C. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Inflammation in Depression: Pathogenic Partners in Crime? World J. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Sterling, K.; Song, W. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Alzheimer’s Disease and Its Pharmaceutical Potential. Transl. Neurodegener. 2022, 11, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Fernández, V.; Mañas-Ojeda, A.; Pacheco-Herrero, M.; Castro-Salazar, E.; Ros-Bernal, F.; Sánchez-Pérez, A.M. Early Intervention with ABA Prevents Neuroinflammation and Memory Impairment in a Triple Transgenic Mice Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 374, 112106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Bylykbashi, E.; Chatila, Z.K.; Lee, S.W.; Pulli, B.; Clemenson, G.D.; Kim, E.; Rompala, A.; Oram, M.K.; Aronson, J.; et al. Exercise on Cognition in an Alzheimer’s Mouse Model. Science 2018, 361, eaan8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Q.; Zhu, X.; Si, J. Angelica Polysaccharide Ameliorates Memory Impairment in Alzheimer’s Disease Rat through Activating BDNF/TrkB/CREB Pathway. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 245, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooshki, R.; Anaeigoudari, A.; Abbasnejad, M.; Askari-Zahabi, K.; Esmaeili-Mahani, S. Abscisic Acid Interplays with PPARγ Receptors and Ameliorates Diabetes-Induced Cognitive Deficits in Rats. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2021, 11, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guri, A.J.; Evans, N.P.; Hontecillas, R.; Bassaganya-Riera, J. T Cell PPAR γ Is Required for the Anti-Inflammatory Efficacy of Abscisic Acid against Experimental IBD. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2011, 22, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maixner, D.W.; Christy, D.; Kong, L.; Viatchenko-Karpinski, V.; Horner, K.A.; Hooks, S.B.; Weng, H.R. Phytohormone Abscisic Acid Ameliorates Neuropathic Pain via Regulating LANCL2 Protein Abundance and Glial Activation at the Spinal Cord. Mol. Pain 2022, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassaganya-Riera, J.; Guri, A.J.; Lu, P.; Climent, M.; Carbo, A.; Sobral, B.W.; Horne, W.T.; Lewis, S.N.; Bevan, D.R.; Hontecillas, R. Abscisic Acid Regulates Inflammation via Ligand-Binding Domain-Independent Activation of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 2504–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariharan, T.; Nanayakkara, G.; Parameshwaran, K.; Bagasrawala, I.; Ahuja, M.; Abdel-Rahman, E.; Amin, A.T.; Dhanasekaran, M.; Suppiramaniam, V.; Amin, R.H. Central Activation of PPAR-Gamma Ameliorates Diabetes Induced Cognitive Dysfunction and Improves BDNF Expression. Neurobiol. Aging 2015, 36, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, S.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Han, H.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. Treatment with 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Delays Choroid Plexus Infiltration and BCSFB Injury in MRL/Lpr Mice Coinciding with Activation of the PPARγ/NF-ΚB/TNF-α Pathway and Suppression of TGF-β/Smad Signaling. Inflammation 2022, 46, 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beheshti, F.; Hosseini, M.; Hashemzehi, M.; Soukhtanloo, M.; Khazaei, M.; Naser Shafei, M. The Effects of PPAR-γ Agonist Pioglitazone on Hippocampal Cytokines, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor, Memory Impairment, and Oxidative Stress Status in Lipopolysaccharidetreated Rats. Iran J. Basic Med. Sci. 2019, 22, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribes-Navarro, A.; Atef, M.; Sánchez-Sarasúa, S.; Beltrán-Bretones, M.T.; Olucha-Bordonau, F.; Sánchez-Pérez, A.M. Abscisic Acid Supplementation Rescues High Fat Diet-Induced Alterations in Hippocampal Inflammation and IRSs Expression. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, M.J. IRS2 Takes Center Stage in the Development of Type 2 Diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 114, 886–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasaki, A.; Melanis, K.; Tsantzali, I.; Stefanou, M.I.; Ntymenou, S.; Paraskevas, S.G.; Kalamatianos, T.; Boutati, E.; Lambadiari, V.; Voumvourakis, K.I.; et al. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus as a Risk Factor for Alzheimer’s Disease: Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, M.; Chávez-Castillo, M.; Bautista, J.; Ortega, Á.; Nava, M.; Salazar, J.; Díaz-Camargo, E.; Medina, O.; Rojas-Quintero, J.; Bermúdez, V. Alzheimer’s Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Pathophysiologic and Pharmacotherapeutics Links. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 745–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Sarasúa, S.; Meseguer-Beltrán, M.; García-Díaz, C.; Beltrán-Bretones, M.T.; ElMlili, N.; Sánchez-Pérez, A.M. IRS1 Expression in Hippocampus Is Age-Dependent and Is Required for Mature Spine Maintenance and Neuritogenesis. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 118, 103693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killick, R.; Scales, G.; Leroy, K.; Causevic, M.; Hooper, C.; Irvine, E.E.; Choudhury, A.I.; Drinkwater, L.; Kerr, F.; Al-Qassab, H.; et al. Deletion of Irs2 Reduces Amyloid Deposition and Rescues Behavioural Deficits in APP Transgenic Mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 386, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanokashira, D.; Fukuokaya, W.; Taguchi, A. Involvement of Insulin Receptor Substrates in Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freude, S.; Hettich, M.M.; Schumann, C.; Stöhr, O.; Koch, L.; Köhler, C.; Udelhoven, M.; Leeser, U.; Müller, M.; Kubota, N.; et al. Neuronal IGF-1 Resistance Reduces Aβ Accumulation and Protects against Premature Death in a Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 3315–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanokashira, D.; Wang, W.; Maruyama, M.; Kuroiwa, C.; White, M.F.; Taguchi, A. Irs2 Deficiency Alters Hippocampus-Associated Behaviors during Young Adulthood. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 559, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, D.A.; Claret, M.; Al-Qassab, H.; Plattner, F.; Irvine, E.E.; Choudhury, A.I.; Giese, K.P.; Withers, D.J.; Pedarzani, P. Brain Deletion of Insulin Receptor Substrate 2 Disrupts Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity and Metaplasticity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bomfim, T.R.; Forny-germano, L.; Sathler, L.B.; Brito-moreira, J.; Houzel, J.; Decker, H.; Silverman, M.A.; Kazi, H.; Melo, H.M.; Mcclean, P.L.; et al. An Anti-Diabetes Agent Protects the Mouse Brain from Defective Insulin Signaling Caused by Alzheimer’s Disease– Associated Aβ Oligomers. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 1339–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, U.; Gogg, S.; Johansson, A.; Olausson, T.; Rotter, V.; Svalstedt, B. Thiazolidinediones (PPARγ Agonists) but Not PPAR α Agonists Increase IRS-2 Gene Expression in 3T3-L1 and Human Adipocytes 1. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammarstedt, A.; Smith, U. Thiazolidinediones (PPARγ Ligands) Increase IRS-1, UCP-2 and C/EBPα Expression, but Not Transdifferentiation, in L6 Muscle Cells. Diabetologia 2003, 46, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Battu, A.; Mohareer, K.; Hasnain, S.E.; Ehtesham, N.Z. Transcription of Human Resistin Gene Involves an Interaction of Sp1 with Peroxisome Proliferator- Activating Receptor Gamma (PPARγ). PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panno, M.L.; Mauro, L.; Marsico, S.; Bellizzi, D.; Rizza, P.; Morelli, C.; Salerno, M.; Giordano, F.; Ando, S. Evidence That the Mouse Insulin Receptor Substrate-1 Belongs to the Gene Family on Which the Promoter Is Activated by Estrogen Receptor α through Its Interaction with Sp1. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 36, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Forward Primer (5′-3′) | Reverse Primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| IRS1 | CCTGACATTGGAGGTGGGTC | TGGGGATCTTCTGGGCCATA |

| IRS2 | GCAGCCAGGAGACAAGAACT | AGCGCTTCACTCTTTCACGA |

| BDNF | TACCTGGATGCCGCAAACAT | AGTTGGCCTTTGGATACCGG |

| TNFα | GACCCTCACACTCAGATCA | TGCTACGACGTGGGCTACG |

| GAPDH | TGCCCCCATGTTTGTGATG | TGGTGGTGCAGGATGCATT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).