3. Case Report

A 33 years old female patient, without significant conditions nor diseases throughout her life (bronchitis in childhood, Helicobacter Pillory infection treated with medication) referred to the Oro-Maxillo-Facial Surgery Clinic of the Emergency City Hospital Timisoara, Romania accusing a slight discomfort in the act of mastication and the occurrence and persistence of a diastema between the upper central incisors, due to the presence of a tumoral mass located in the anterior hard palate, with the involvement of the incisive papilla and extended between the upper central incisors. Anamnestic, the patient establishes the occurrence of the lesion approximately 8 years prior, with a continuous, slow, progressive growth.

The tumor had a shape of a droplet, well delimited, with a dimension of approximately 1,5 cm (sagittal plane) / 1 cm (transverse plane), with a nodular lower pole located at the median palatal fibromucosa, extended between the bilateral palatal rugae. It had a pink tint, smooth surface, soft, resilient, depressible consistency. The upper pole of the tumoral apex was located interdentally between the superior central incisors (1.1/8-2.1/9). On the buccal side of the alveolar crest, the lesion was in contact with the crestal insertion of a hypertrophic upper labial frenulum, having a reddish color and a slightly firmer consistency, apparently fixed to the underlying bone (

Figure 1).

The clinical examination also revealed a dento-alveolar incongruence with the presence of a maxillary interincisal diastema of 2mm and a slight distal tipping of the right upper central incisor, with delicate coverage, that might be associated with the presence of the mentioned tumor. Furthermore, a median buccal gingivo-mucosal scar is present between the two upper central incisors 1.1/8 -2.1/9, the patient affirming a previous surgical intervention for a frenoplasty of the upper labial frenulum.

The cone beam computed tomography image (CBCT) does not reveal any changes of the subjacent bone structure in the anterior hard palate, suggesting the sole involvement of the soft tissue (

Figure 2).

Under local anesthesia, a classical incision was performed that circumscribed the tumoral lesion at the level of the palatal mucosa, as well as the interincisive alveolar ridge. The tumor was detached from the underlying bone and removed. Hemostasis was achieved by monopolar electrocautery. The postoperative defect was closed by marginal-marginal suture at the posterior palatal level by placing non-absorbable suture threads 4.0 separately and a vertical mattress.The residual gingival defect was protected by a periodontal dressing, for the purpose of “per secundam” healing.

On microscopic examination of Hematoxylin–Eosin (HE) stained slides, there were observed fascicles of spindle-shaped cells arranged in unequal bundles, with large eosinophilic cytoplasm and vesicular, monotonous, blunt-ended nuclei, with finely granular chromatin (

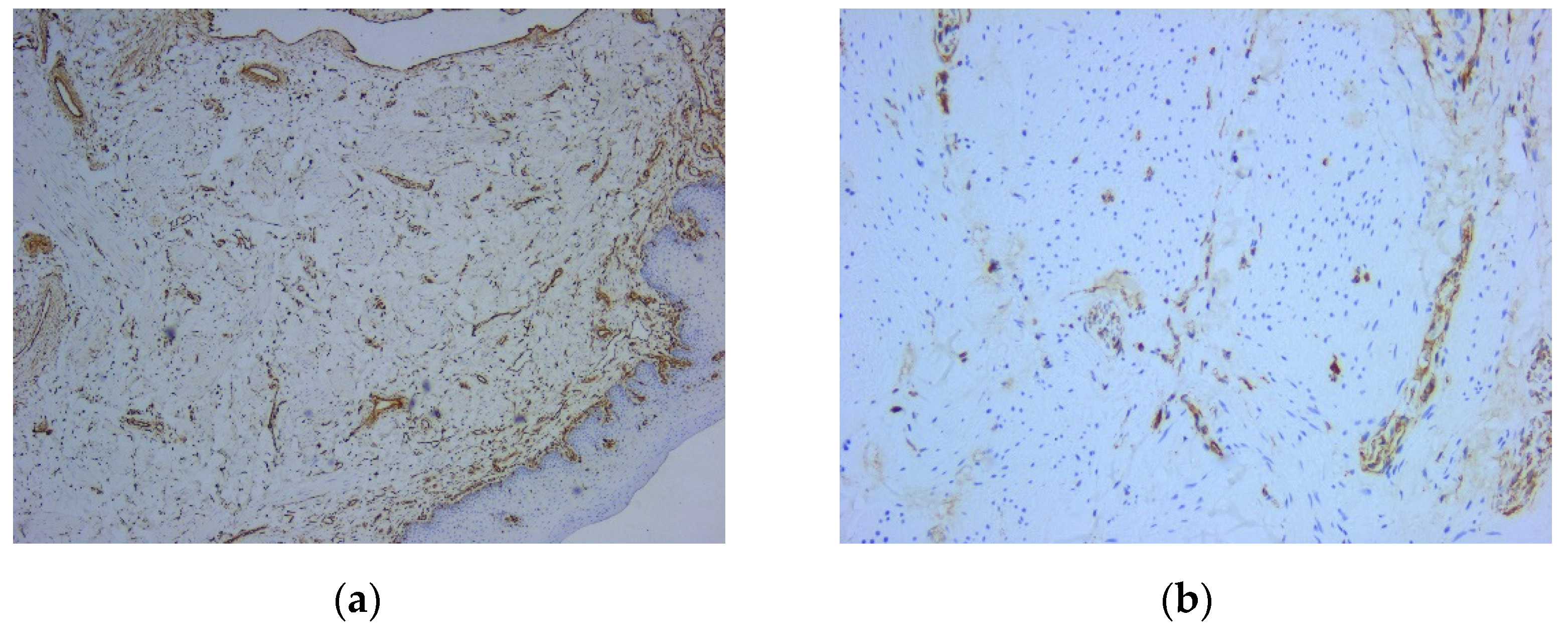

Figure 3). Immunohistochemically (IHC) intense and diffuse positive reactions were found for desmin (

Figure 4), as well as for smooth muscle actin (SMA) (

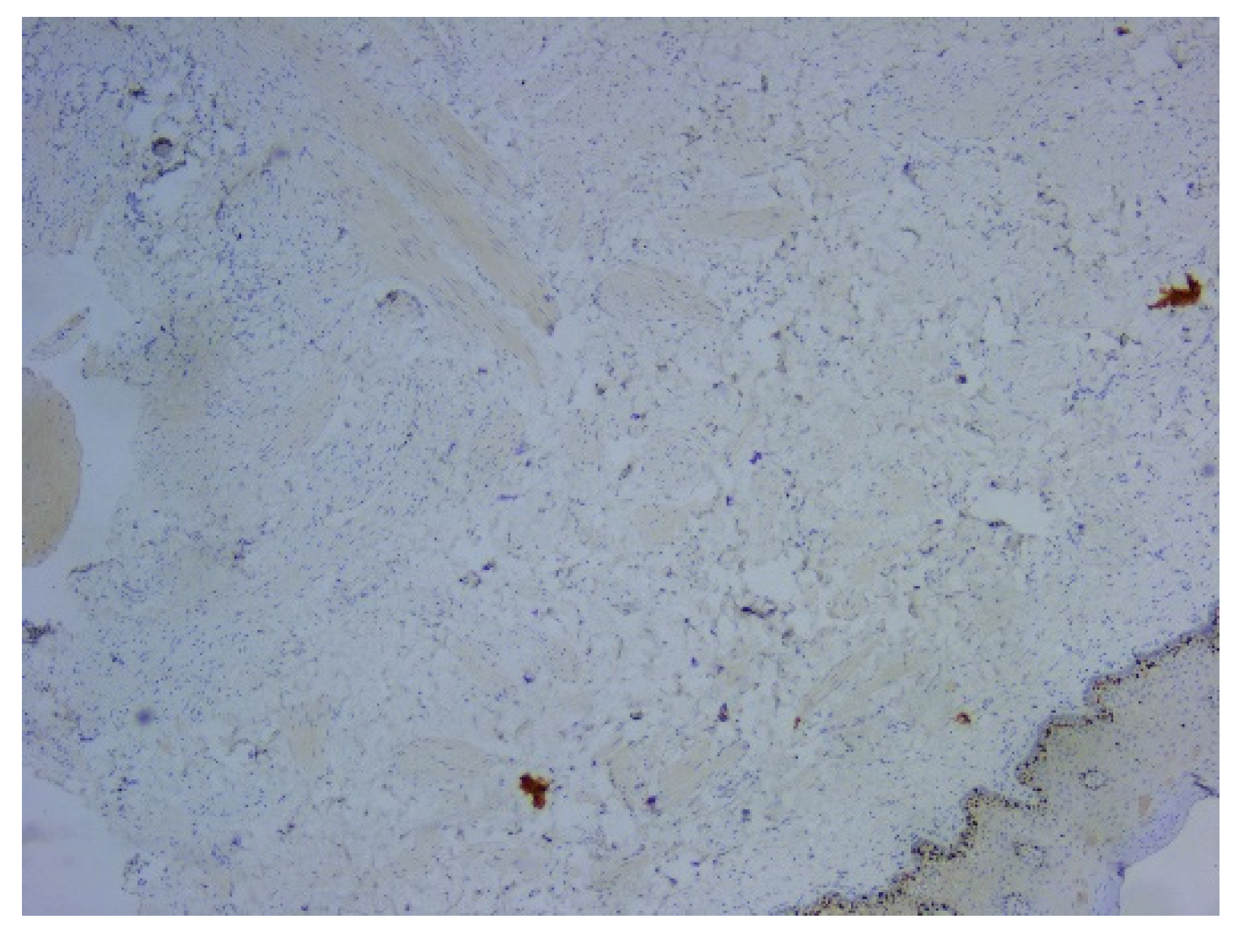

Figure 5). On the other hand, there were immunohistochemically negative tumor cells for vimentin staining, with positive internal control at the level of the vascular component (

Figure 6). Ki67 cell proliferation index was 3% (

Figure 7). The final diagnosis was of leiomyoma.

4. Discussion

Leiomyoma is a benign smooth muscle tumor, that can develop in any site [

1,

3,

9]. The most frequent area is represented by the female genital tract (95%), followed by skin (3%) and gastrointestinal tract (1,5%). Even if it is a relatively common tumor, in the oral cavity, leiomyoma is encountered not that often [

2,

3,

5,

6,

7,

10]. Less than 1% out of the total number of leiomyomas arise in the head and neck region, while only 0,065% occur in the oral cavity [

1,

4,

9,

11].Meanwhile, leiomyoma represents less than 1% of all tumors of the oral cavity [

2].

Benign tumors of the smooth muscle are rarely present in the oral cavity and are usually non-aggressive [

2,

6]. “

The earliest report of an oral leiomyoma was by Blanc in 1884 [

10]. The sporadic presence in oral cavity, indistinguishable clinical appearance and nonetheless, variable histopathological images can often lead to misdiagnosis, with numerous differential diagnosis [

1,

2,

10]. Da Silva et al. demonstrated that this benign tumor accounted for only 0,9% of 790 oral soft tissue neoplasms [

12].

Due to the scarcity of smooth muscle in the structures of the oral cavity [

1,

10], the origin of leiomyoma in this area is limited to these possible areas: tunica media of the blood vessels, ductus lingualis, circumvallate papilla [

3,

10] or heterotopic embryonaltissue [

5,

10].

Oral cavity leiomyoma may debut at any age, but most of the authors reported that this pathology is usually present in adults, with the greatest incidence in 4

th and 5

th decade of life [

1,

3,

5,

6,

10].

Regarding gender distribution of oral leiomyoma, there isn’t a common opinion shared by the authors. Some of them claimed that there is a male predominance of oral leiomyoma [

3,

5,

10,

11,

14], others argued that in female patients are more frequent [

1,

6], while other authors stated similar distribution in both sexes [

2,

9,

10].

We report a case of 33 years old female patient in the moment of diagnosis, affirming the presence of the lesion for 8 years.

The most common sites of occurrence of leiomyoma in the oral cavity are: lingual, labial, hard or soft palate and jugal mucosa [

2,

8]; cases were outlined also in other less frequent locations, such as the retro molar trigon, floor of the mouth, gingiva or submandibular region [

3,

5]. Additionally, cases with intraosseous localization of leiomyoma with the involvement of the jaws, mainly in the mandible bone, were also reported in literature [

2,

6,

13].

In our female patient, the site of the leiomyoma is uncommon: the midline fibromucosa of the anterior hard palate, involving the incisive papilla, extended on the alveolar ridge between the upper central incisors.

There is a general agreement between the authors regarding the most common clinical characteristics of the leiomyoma, affecting oral cavity structures, especially the ones involving the hard palate: small (<3cm), solitary, slow growing nodular mass, firm to the touch [

1,

2,

3,

5,

6,

9,

10,

12]. For the majority of the reported cases of oral cavity leiomyoma, the color of the lesion had a pinkish, reddish, bluish, grayish or purplish tint [

2,

8,

9,

14], depending on their depth and vascularity [

5], with the surface that resembles the texture of the normal neighboring mucosa [

6,

10].

In our case, the aspect of the tumor was a solitary, droplet-shaped with dimensions of 1,5/1 cm, localized in the anterior palatal fibromucosa, involving the incisive papilla, with a smooth surface and a pink tint, of soft, resilient, depressible consistency.

Generally, leiomyoma of the oral cavity is characterized as an asymptomatic lesion [

1,

3,

5,

6,

7] but in some cases, as the tumor evolves, some symptoms may occur, such as: pain, teeth mobility, toothache or even difficulty in chewing or deglutition [

1,

3,

5,

6,

8,

10].

In our case, the patient did not present any symptoms other than a slight discomfort in the act of mastication and the occurrence and persistence of a diastema between the upper central incisors, where the anterior apex of tumoral lesion in discussion here, was inserted interdentally. For this dento-alveolar incongruence, the patient sought dental treatment prior and a frenoplasty procedure was performed. The persistence of the diastema was the main reason for which the patient was referred for surgical treatment, regarding an “enlarged incisive papilla inserted on the alveolar crest”. The misdiagnosis, followed by repeated medical procedures that attempted to treat the complication, not the cause, were the reason for the 8 years delay between the occurrence of the lesion and the time of surgical excision, with a definitive histopathological diagnosis of the tumor. This outcome, in our opinion, might be explained up to a point, by the lack of pain or other important symptoms, the slow-growing characteristic of the leiomyoma, the quasinormal aspect of the tumoral surface, characteristics that can lead to difficulties in the clinical diagnosis, postponed radical treatment and final histopathological diagnosis.

While the clinical appearance of oral leiomyioma is unspecific [

1,

2,

3,

5], the final diagnosis is established by histopathological examination, with specific immunohistochemical staining for smooth muscle origin [

1,

2,

3,

5].

From the clinical point of view, the differential diagnosis of oral leiomyoma is very difficult and should include other benign tumors (fibroma, neurofibroma, lipoma, etc.), salivary gland tumors (mucocele, pleomorphic adenoma), vascular tumors (lymphangioma, hemangioma) even tumors of the periodontium, but the upmost importance is to differentiate leiomyoma from the malignant counterpart, leiomyosarcoma [

1,

4,

5,

10].

The histopatological diagnosis can sometimes encounter difficulties in differentiating leiomyoma from other tumors, for example: schwannoma (neurilemmoa), neurofibroma ,myofibroma, myopericytoma/haemangiopericytoma, solitary fibrous tumors, benign fibrous histiocytoma, spindle cell pleomorphic adenoma or well differentiate/low-grade leiomyosarcoma [

2,

4,

10]. Leiomyosarcoma is composed of interlacing spindle-shaped cells fascicles with blunt-ended nuclei and mild or severe atypia [

2]. The well differentiated leiomyosarcoma is a very similar lesion to leiomyoma, except the nuclei are more hyperchromatic and the mitotic activity is prominent. The high Ki67 proliferation index (>10% nuclear staining) is necessary for separating benign from malignant tumors. The final diagnosis can be established only by immunohistochemical staining that identify smooth muscle components [

10].

There is a general consensus concerning the treatment of the oral cavity leiomyoma, that the surgical excision with clear margins and periodical monitorization for observing eventual recurrences, is the most successful therapeutical attitude [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. In case of complete resection of the tumor, the recurrences rates are very low, followed by a favorable postoperative prognostic [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

7,

8,

9].

For our patient, the complete resection of the tumor was performed, using classical incision with a cold scalpel, with a good postoperative outcome, without any relapse at the 12-monthsfollow-up.

Figure 1.

Intraorally aspect: (a) Aspect of the tumoral lesion at the level of the incisive papilla and anterior palatal fibomucosa; (b) Aspect of the tumoral lesion (buccal view), interincisal diastema and the gingivo-mucosal scar.

Figure 1.

Intraorally aspect: (a) Aspect of the tumoral lesion at the level of the incisive papilla and anterior palatal fibomucosa; (b) Aspect of the tumoral lesion (buccal view), interincisal diastema and the gingivo-mucosal scar.

Figure 2.

Cone Beam Computed Tomography shows no underlying bone structure alteration.

Figure 2.

Cone Beam Computed Tomography shows no underlying bone structure alteration.

Figure 3.

Microscopic image using Hematoxylin–Eosin (HE) staining: (a) Tumor proliferation of the mucosa with spindle-shaped cells arranged in unequal bundles, HE staining, ob. 5x; (b) Fusiform tumor cells in a fasciculate pattern, with large, eosinophilic cytoplasm and elongated monotonous blunt-ended nuclei, HE staining, ob. 20x; (c) Fascicles of tumor cells arranged among acinar structures in the lamina propria of the mucosa, HE staining, ob. 5x.

Figure 3.

Microscopic image using Hematoxylin–Eosin (HE) staining: (a) Tumor proliferation of the mucosa with spindle-shaped cells arranged in unequal bundles, HE staining, ob. 5x; (b) Fusiform tumor cells in a fasciculate pattern, with large, eosinophilic cytoplasm and elongated monotonous blunt-ended nuclei, HE staining, ob. 20x; (c) Fascicles of tumor cells arranged among acinar structures in the lamina propria of the mucosa, HE staining, ob. 5x.

Figure 4.

Microscopic image using immunohistochemical reactions for desmin: (a) Tumor cells with diffuse and intense reaction IHC positive for desmin, Anti-Desmin Antibody, ob. 5x; (b) Intense and diffuse positive reaction for desmin, immunolabelling of the cytoplasm, Anti-Desmin Antibody, ob. 20x.

Figure 4.

Microscopic image using immunohistochemical reactions for desmin: (a) Tumor cells with diffuse and intense reaction IHC positive for desmin, Anti-Desmin Antibody, ob. 5x; (b) Intense and diffuse positive reaction for desmin, immunolabelling of the cytoplasm, Anti-Desmin Antibody, ob. 20x.

Figure 5.

Microscopic image using immunohistochemical reactions for smooth muscle actin: (a) Positive intense and diffuse reaction for smooth muscle actin, Anti-SMA Antibody, ob. 5x; (b) Positive intense and diffuse reaction for smooth muscle actin, immunolabelling of the cytoplasm, Anti-SMA Antibody, ob. 20x.

Figure 5.

Microscopic image using immunohistochemical reactions for smooth muscle actin: (a) Positive intense and diffuse reaction for smooth muscle actin, Anti-SMA Antibody, ob. 5x; (b) Positive intense and diffuse reaction for smooth muscle actin, immunolabelling of the cytoplasm, Anti-SMA Antibody, ob. 20x.

Figure 6.

Microscopic image using immunohistochemical reactions for vimentin: (a) Negative IHC reaction for vimentin, with positive control, Anti-Vimentin Antibody, ob. 5x; (b) Immunohistochemically negative tumor cells for vimentin, positive internal control at the level of the vascular component, Anti-Vimentin Antibody, ob. 20x.

Figure 6.

Microscopic image using immunohistochemical reactions for vimentin: (a) Negative IHC reaction for vimentin, with positive control, Anti-Vimentin Antibody, ob. 5x; (b) Immunohistochemically negative tumor cells for vimentin, positive internal control at the level of the vascular component, Anti-Vimentin Antibody, ob. 20x.

Figure 7.

Microscopic image using immunohistochemical reactions for Ki67: IHC reaction for Ki67 (positive internal control at the level of the basal layer of the covering epithelium), Anti-Ki-67 Antibody, ob. 5x.

Figure 7.

Microscopic image using immunohistochemical reactions for Ki67: IHC reaction for Ki67 (positive internal control at the level of the basal layer of the covering epithelium), Anti-Ki-67 Antibody, ob. 5x.

Table 1.

Data related to the antibodies used for immunohistochemical reactions.

Table 1.

Data related to the antibodies used for immunohistochemical reactions.

| Antibody |

Substrate |

Dilution |

Clone |

| Smooth Muscle Actin (SMA) |

Monoclonal Mouse |

Ready-To-Use |

asm-1 |

| Desmin |

Monoclonal Mouse |

1:200 for 30 minutes at 25°C |

DE-R-11 |

| Vimentin |

Monoclonal Mouse |

1:800 for 30 minutes at 25°C |

V9 |

| Ki67 |

Monoclonal Mouse |

Ready-To-Use |

MM1 |