Submitted:

15 June 2023

Posted:

16 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

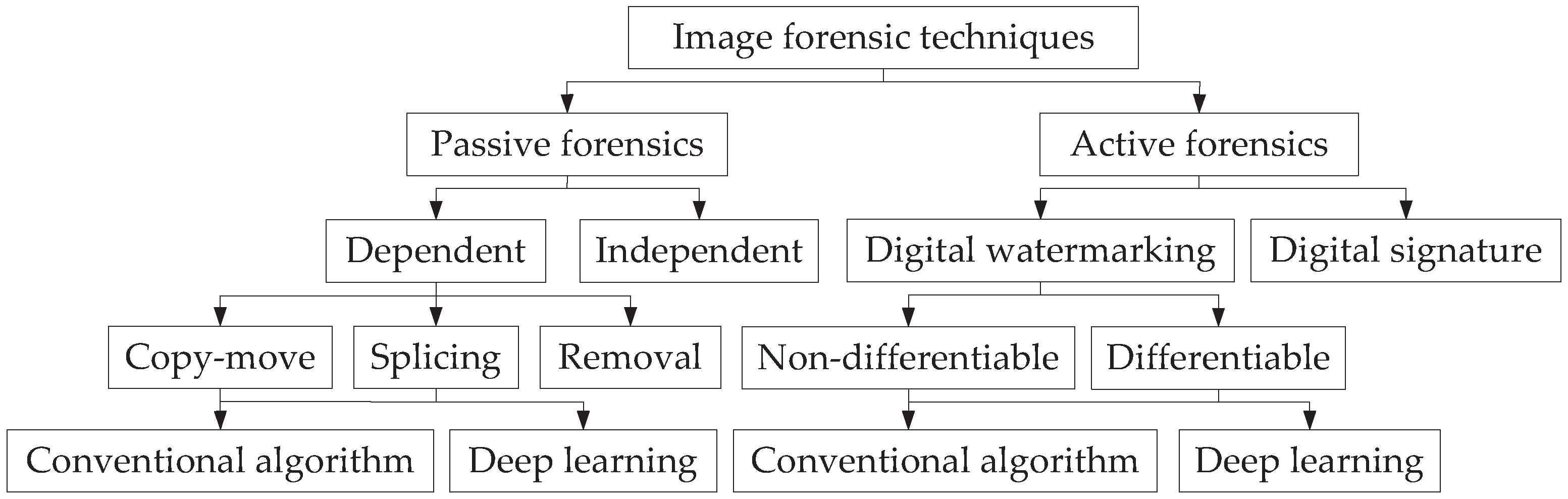

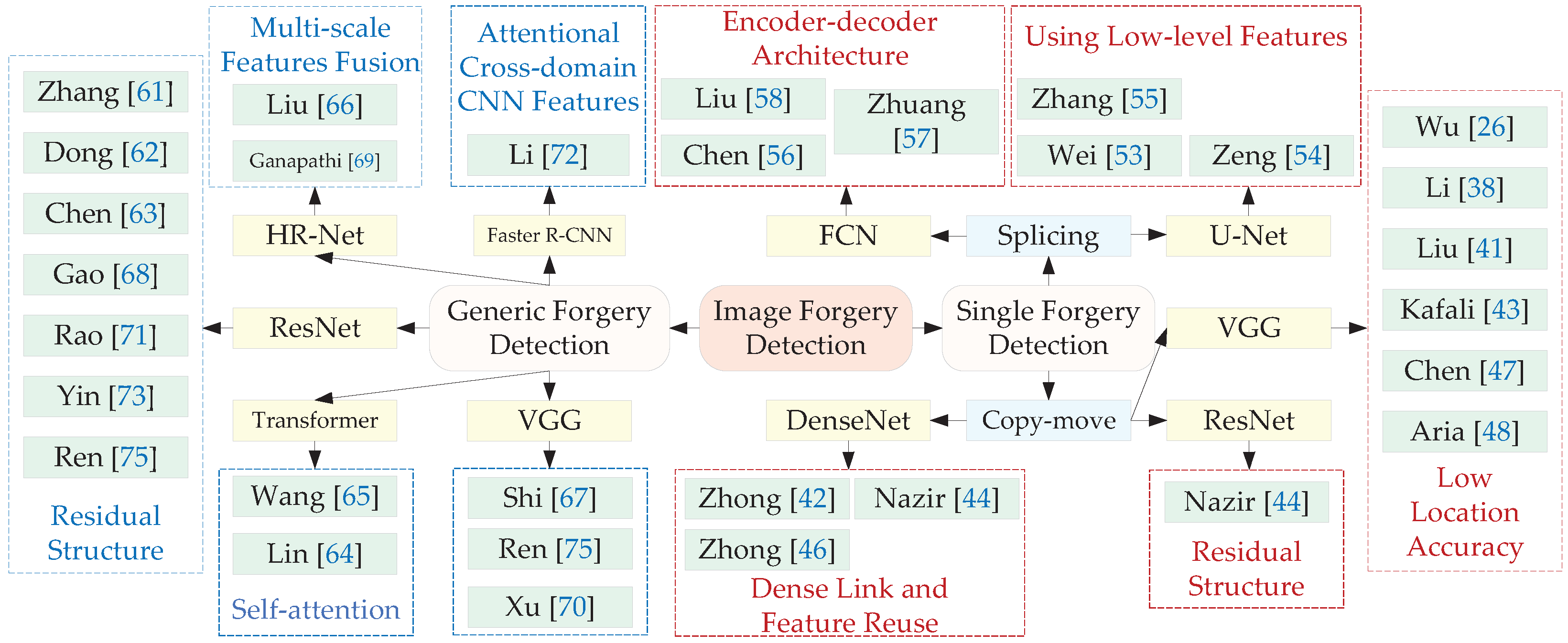

2. Image Forensic Techniques

2.1. Passive Forensics

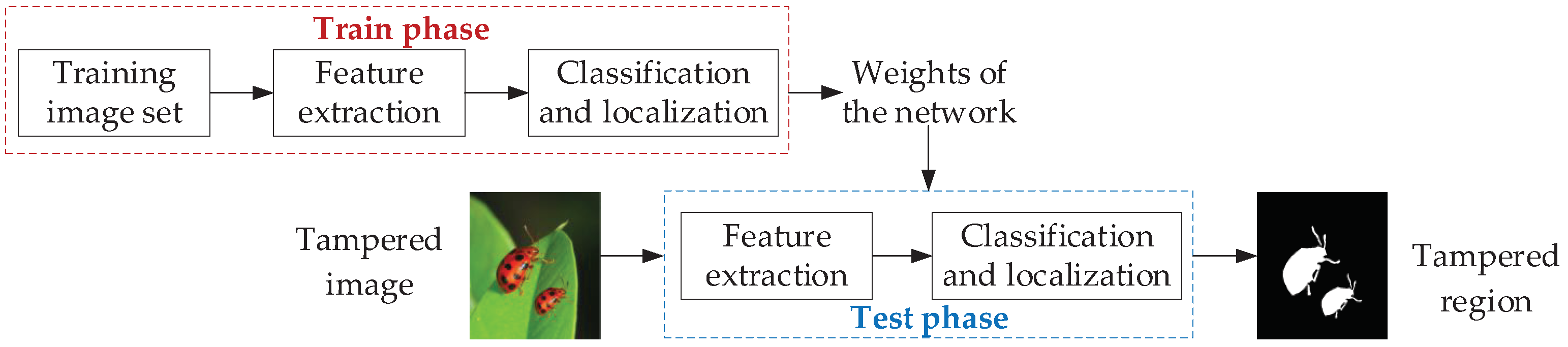

2.1.1. Basic Framework of Image Forgery Detection

2.1.2. Performance Evalution Metrics

2.1.3. Datasets for Image Forgery Detection

2.2. Active Forensics

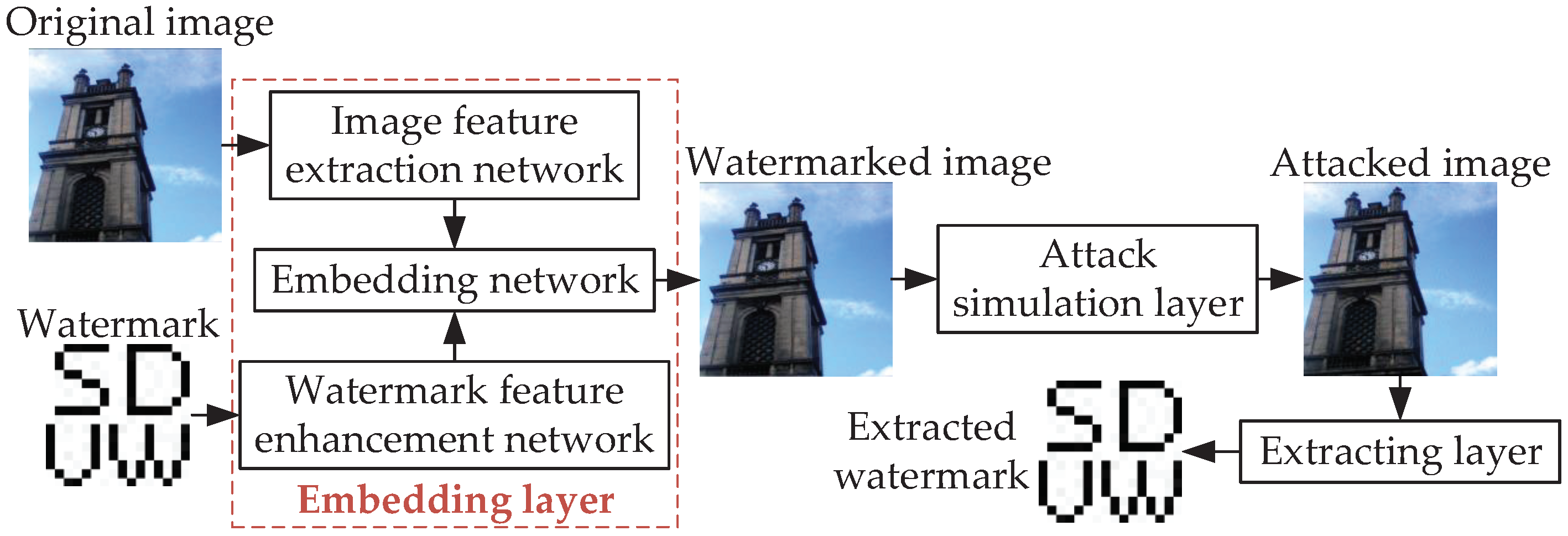

2.2.1. Basic Framework of Robust Image Watermarking Algorithm

2.2.2. Performance Evaluation Metrics

2.2.3. Attacks of Robust Watermarking

3. Image Forgery Detection Based on Deep Learning

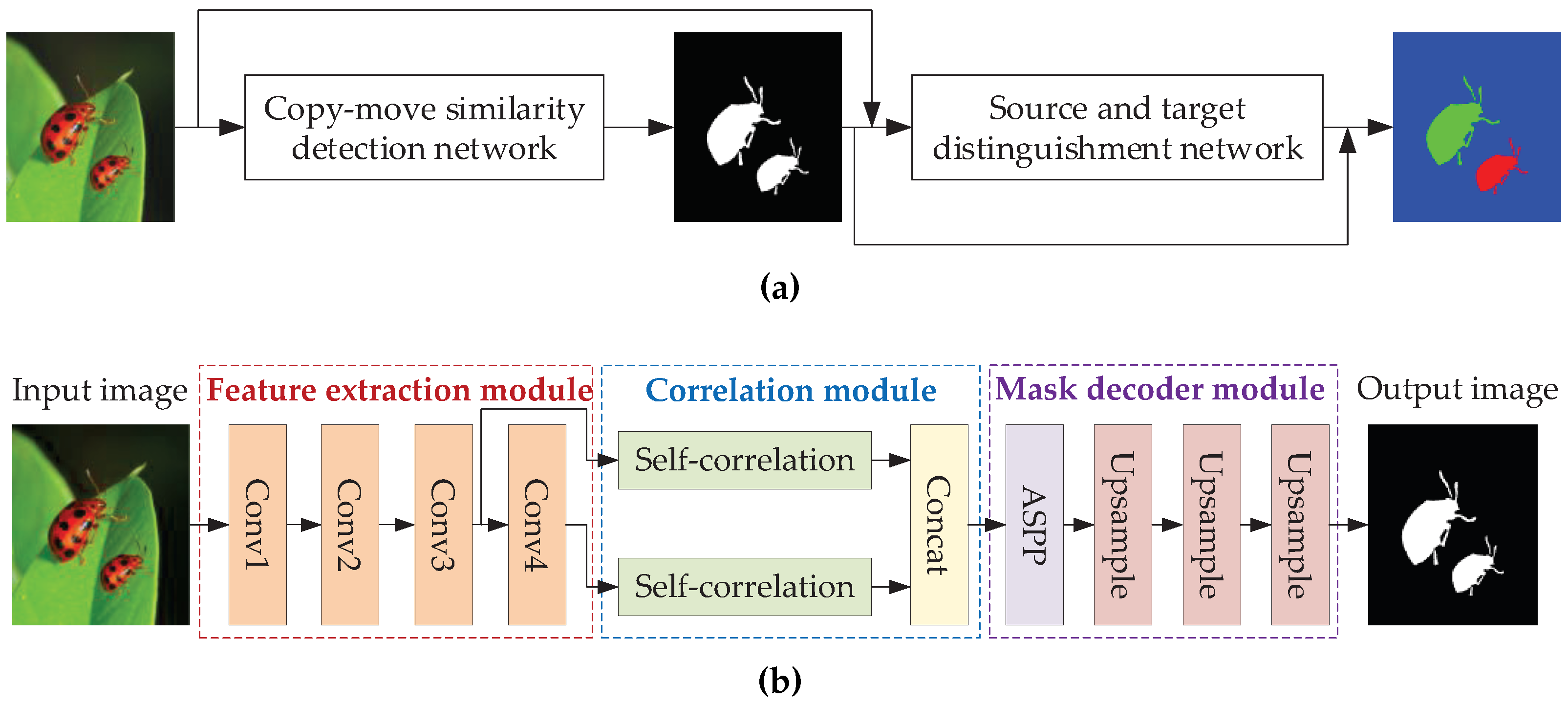

3.1. Image Copy-Move Forgery Detection

3.2. Image Splicing Forgery Detection

3.3. Image Generic Forgery Detection

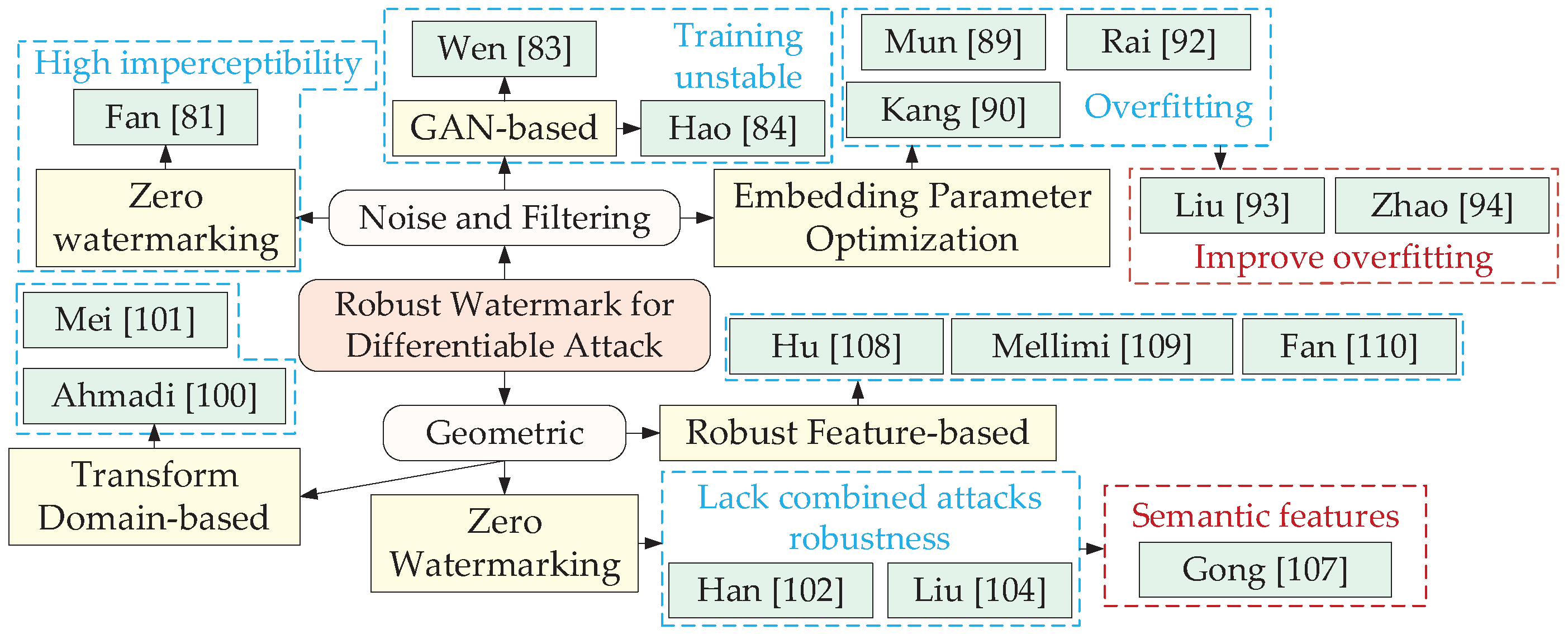

4. Robust Image Watermarking Based on Deep Learning

4.1. Robust Image Watermark against Differentiable Attack

4.1.1. Robust Image Watermark against Noise and Filtering Attack

4.1.2. Robust Image Watermark against Geometric Attacks

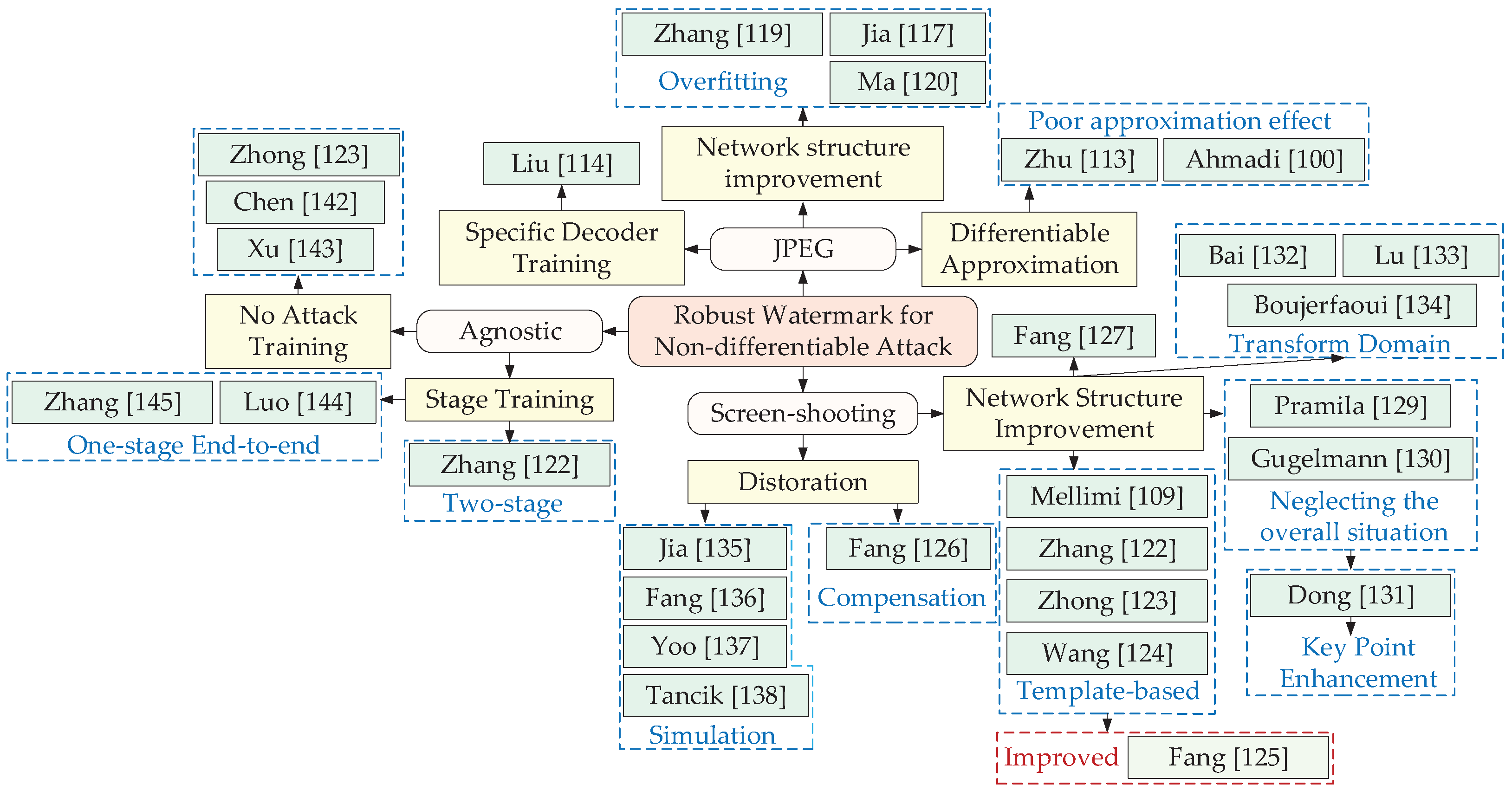

4.2. Robust Image Watermark against Non-differentiable Attack

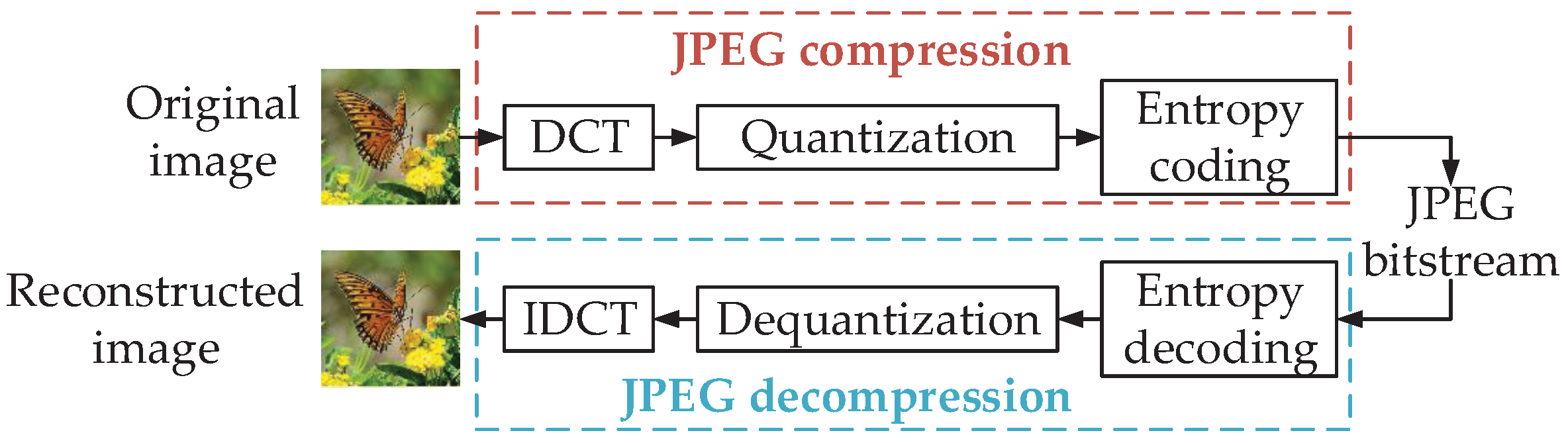

4.2.1. Robust Image Watermark against JPEG Attack

4.2.2. Robust Image Watermark against Screen-shooting Attack

4.2.3. Robust Image Watermark against Agnostic Attack

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaur, G.; Singh, N.; Kumar, M. Image forgery techniques: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 1577–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhou, X. A survey on passive image copy-move forgery detection. Journal of Information Processing Systems 2018, 14, 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardelli, M.; Guerrini, F.; Leonardi, R.; Adami, N. Image forgery detection: A survey of recent deep-learning approaches. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 17521–17566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, S.T.; Kumar, M.; Singh, P.; Aggarwal, N.; Kumar, K. A comprehensive survey of image and video forgery techniques: Variants, challenges, and future directions. Multimedia Syst. 2022, 28, 939–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhmawati, L.; Wirawan, W.; Suwadi, S. A recent survey of self-embedding fragile watermarking scheme for image authentication with recovery capability. EURASIP J. Image Video Process. 2019, 2019, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, P. A recent survey on image watermarking techniques and its application in e-governance. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2018, 77, 3597–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez-Ortiz, A.; Feregrino-Uribe, C.; Hasimoto-Beltran, R.; Garcia-Hernandez, J.J. A survey on reversible watermarking for multimedia content: A robustness overview. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 132662–132681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, P.K. Survey of robust and imperceptible watermarking. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 8603–8633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrit, P.; Singh, A.K. Survey on watermarking methods in the artificial intelligence domain and beyond. Comput. Commun. 2022, 188, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, H.; Sun, J. A comprehensive survey on robust image watermarking. Neurocomputing 2022, 488, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evsutin, O.; Dzhanashia, K. Watermarking schemes for digital images: Robustness overview. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2022, 100, 116523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.; Mehmood, Z.; Shah, M.; Saba, T. A robust technique for copy-move forgery detection and localization in digital images via stationary wavelet and discrete cosine transform. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2018, 53, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiprakash, S.P.; Desai, M.B.; Prakash, C.S.; Mistry, V.H.; Radadiya, K.L. Low dimensional DCT and DWT feature based model for detection of image splicing and copy-move forgery. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 29977–30005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wo, Y.; Yang, K.; Han, G.; Chen, H.; Wu, W. Copy-move forgery detection based on multi-radius PCET. IET Image Process. 2017, 11, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Kang, T.A.; Moon, Y.H.; Eom, I.K. Copy-move forgery detection using scale invariant feature and reduced local binary pattern histogram. Symmetry-Basel. 2020, 12, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, A.; Jain, A.; Kumar, M. Identification of copy-move and splicing based forgeries using advanced SURF and revised template matching. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 23877–23898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Singh, K. Digital image forensic approach based on the second-order statistical analysis of CFA artifacts. Forens. Sci. Int. Digit. Investig. 2020, 32, 200899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Peng, A.; Lin, X. Exposing image splicing with inconsistent sensor noise levels. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 26139–26154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.F.; Chang, S.F. Detecting image splicing using geometry invariants and camera characteristics consistency. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo. IEEE: Toronto, ON, Canada; 2006; pp. 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerini, I.; Ballan, L.; Caldelli, R.; Del Bimbo, A.; Serra, G. A SIFT-based forensic method for copy-move attack detection and transformation recovery. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensic Secur. 2011, 6, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wang, W.; Tan, T. Casia image tampering detection evaluation database. In Proceedings of the IEEE China Summit and International Conference on Signal and Information Processing. IEEE: Beijing, China; 2013; pp. 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, T.J.; Riess, C.; Angelopoulou, E.; Pedrini, H.; de Rezende Rocha, A. Exposing digital image forgeries by illumination color classification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensic Secur. 2013, 8, 1182–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tralic, D.; Zupancic, I.; Grgic, S.; Grgic, M. CoMoFoD–New database for copy-move forgery detection. In Proceedings of the International Symposium Electronics in Marine. IEEE: Zadar, Croatia; 2013; pp. 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, B.; Zhu, Y.; Subramanian, R.; Ng, T.T.; Shen, X.; Winkler, S. COVERAGE–A novel database for copy-move forgery detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing. IEEE: Phoenix, AZ, USA; 2016; pp. 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korus, P. Digital image integrity–A survey of protection and verification techniques. Digit. Signal Process. 2017, 71, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Abd-Almageed, W.; Natarajan, P. Busternet: Detecting copy-move image forgery with source/target localization. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Munich, Berlin; 2018; pp. 168–184. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, H.; Kozak, M.; Robertson, E.; Lee, Y.; Yates, A.N.; Delgado, A.; Zhou, D.; Kheyrkhah, T.; Smith, J.; Fiscus, J. MFC datasets: Large-scale benchmark datasets for media forensic challenge evaluation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Winter Applications of Computer Vision Workshops. IEEE: Waikoloa, HI, USA; 2019; pp. 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfoudi, G.; Tajini, B.; Retraint, F.; Morain-Nicolier, F.; Dugelay, J.L.; Marc, P. DEFACTO: Image and face manipulation dataset. In Proceedings of the 27th European Signal Processing Conference. IEEE: A Coruna, Spain; 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novozamsky, A.; Mahdian, B.; Saic, S. IMD2020: A large-scale annotated dataset tailored for detecting manipulated images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision Workshops. IEEE: Snowmass, CO, USA; 2020; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schyndel, R.G.; Tirkel, A.Z.; Osborne, C.F. A digital watermark. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Image Processing; IEEE: Austin, TX, USA, 1994; Vol. 2, pp. 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, S.; Wu, X.; Wang, Z. Detection of LSB steganography via sample pair analysis. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2003, 51, 1995–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Georganas, N.D. Digital image watermarking for joint ownership verification without a trusted dealer. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Multimedia and Expo; IEEE: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2003; Vol. 2, pp. 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parah, S.A.; Sheikh, J.A.; Loan, N.A.; Bhat, G.M. Robust and blind watermarking technique in DCT domain using inter-block coefficient differencing. Digit. Signal Process. 2016, 53, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad, S.; Amirmazlaghani, M. A new multiplicative watermark detector in the contourlet domain using t location-scale distribution. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 77, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad, E.; Samavi, S.; Reza Soroushmehr, S.; Karimi, N.; Etemad, M.; Shirani, S.; Najarian, K. Robust image watermarking scheme using bit-plane of Hadamard coefficients. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2018, 77, 2033–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Ni, J. A deep learning approach to detection of splicing and copy-move forgeries in images. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Workshop on Information Forensics and Security. IEEE: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Gupta, S.K. A robust copy move forgery classification using end to end convolution neural network. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization. IEEE: Noida, India; 2020; pp. 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhou, X.; Qin, Z. Image copy-move forgery detection and localization based on super-BPD segmentation and DCNN. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 14987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Liu, Y.; Wei, D.; Bai, X.; Xu, Y. Super-BPD: Super boundary-to-pixel direction for fast image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE: Seattle, WA, USA; 2020; pp. 9253–9262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Deeplab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xia, C.; Zhu, X.; Xu, S. Two-stage copy-move forgery detection with self deep matching and proposal superglue. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 31, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.L.; Pun, C.M. An end-to-end dense-inceptionnet for image copy-move forgery detection. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensic Secur. 2019, 15, 2134–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafali, E.; Vretos, N.; Semertzidis, T.; Daras, P. RobusterNet: Improving copy-move forgery detection with Volterra-based convolutions. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition. IEEE: Milan, Italy; 2020; pp. 1160–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, T.; Nawaz, M.; Masood, M.; Javed, A. Copy move forgery detection and segmentation using improved mask region-based convolution network (RCNN). Appl. Soft. Comput. 2022, 131, 109778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. IEEE: Venice, Italy; 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.L.; Yang, J.X.; Gan, Y.F.; Huang, L.; Zeng, H. Coarse-to-fine spatial-channel-boundary attention network for image copy-move forgery detection. Soft Comput. 2022, 26, 11461–11478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Tan, W.; Coatrieux, G.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, Y.Q. A serial image copy-move forgery localization scheme with source/target distinguishment. IEEE Trans. Multimedia. 2020, 23, 3506–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Hashemzadeh, M.; Farajzadeh, N. QDL-CMFD: A quality-independent and deep learning-based copy-move image forgery detection method. Neurocomputing 2022, 511, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, M.; Phan, Q.T.; Tondi, B. Copy move source-target disambiguation through multi-branch CNNs. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensic Secur. 2020, 16, 1825–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyishaka, P.; Bhagvati, C. Image splicing detection technique based on illumination-reflectance model and LBP. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 2161–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Shi, Z.; Chen, H. Splicing image forgery detection using textural features based on the grey level co-occurrence matrices. IET Image Process. 2017, 11, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Ghanekar, U. Spliced image classification and tampered region localization using local directional pattern. International Journal of Image, Graphics and Signal Processing 2019, 11, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, B.; Liu, X.; Yan, Z.; Ma, J. Controlling neural learning network with multiple scales for image splicing forgery detection. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2020, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Tong, L.; Liang, Y.; Zhou, N.; Wu, J. Multitask image splicing tampering detection based on attention mechanism. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Wu, L.; Kwong, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y. Multi-task SE-network for image splicing localization. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 32, 4828–4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Qi, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, G.; Zheng, Y.; Xiao, B. Image splicing localization using residual image and residual-based fully convolutional network. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2020, 73, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, P.; Li, H.; Tan, S.; Li, B.; Huang, J. Image tampering localization using a dense fully convolutional network. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensic Secur. 2021, 16, 2986–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, H.; Liu, Z. Image forgery localization based on fully convolutional network with noise feature. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 17919–17935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.; Niu, S.; Jin, J.; Zhang, J.; Ren, H.; Zhao, X. Multi-scale attention context-aware network for detection and localization of image splicing. Appl. Intell. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ni, R.; Zhao, Y. ET: Edge-enhanced transformer for image splicing detection. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2022, 29, 1232–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, J. Noise and edge based dual branch image manipulation detection. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2207.00724. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, C.; Chen, X.; Hu, R.; Cao, J.; Li, X. MVSS-Net: Multi-view multi-scale supervised networks for image manipulation detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 3539–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liao, X.; Wang, W.; Qian, Z.; Qin, Z.; Wang, Y. SNIS: A signal noise separation-based network for post-processed image forgery detection. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 935–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wang, S.; Deng, J.; Fu, Y.; Bai, X.; Chen, X.; Qu, X.; Tang, W. Image manipulation detection by multiple tampering traces and edge artifact enhancement. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 133, 109026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Chen, J.; Han, X.; Shrivastava, A.; Lim, S.N.; Jiang, Y.G. Objectformer for image manipulation detection and localization. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE: New Orleans, LA, USA; 2022; pp. 2364–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, X. PSCC-Net: Progressive spatio-channel correlation network for image manipulation detection and localization. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 7505–7517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Chang, C.; Chen, H.; Du, X.; Zhang, H. PR-Net: Progressively-refined neural network for image manipulation localization. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 3166–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Sun, C.; Cheng, Z.; Guan, W.; Liu, A.; Wang, M. TBNet: A two-stream boundary-aware network for generic image manipulation localization. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathi, I.I.; Javed, S.; Ali, S.S.; Mahmood, A.; Vu, N.S.; Werghi, N. Learning to localize image forgery using end-to-end attention network. Neurocomputing 2022, 512, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Shen, X.; Lyu, Y.; Du, X.; Feng, F. MC-Net: Learning mutually-complementary features for image manipulation localization. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 3072–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Ni, J.; Xie, H. Multi-semantic CRF-based attention model for image forgery detection and localization. Signal Process. 2021, 183, 108051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xu, S.; Ma, W.; Zong, Q. Image manipulation localization using attentional cross-domain CNN features. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Wang, J.; Lu, W.; Luo, X. Contrastive learning based multi-task network for image manipulation detection. Signal Process. 2022, 201, 108709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, L.; Tan, S.; Li, B.; Huang, J. Self-adversarial training incorporating forgery attention for image forgery localization. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensic Secur. 2022, 17, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.; Niu, S.; Ren, H.; Zhang, S.; Han, T.; Tong, X. ESRNet: Efficient search and recognition network for image manipulation detection. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2022, 18, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.; Carvalho, T.; Ferreira, A.; Rocha, A. Going deeper into copy-move forgery detection: Exploring image telltales via multi-scale analysis and voting processes. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2015, 29, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, D.; Poggi, G.; Verdoliva, L. Copy-move forgery detection based on patchmatch. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing. IEEE: Paris, France; 2014; pp. 5312–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.T.; Chang, S.F.; Sun, Q. A data set of authentic and spliced image blocks. Columbia University, ADVENT Technical Report 2004, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z.; Shen, X.; Chen, H.; Lyu, Y. Global semantic consistency network for image manipulation detection. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2020, 27, 1755–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Communications of the ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Li, J.; Bhatti, U.A.; Shao, C.; Gong, C.; Cheng, J.; Chen, Y. A multi-watermarking algorithm for medical images using Inception V3 and DCT. CMC-Comput. Mat. Contin. 2023, 74, 1279–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE: Las Vegas, NV, USA; 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Aydore, S. Romark: A robust watermarking system using adversarial training. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1910.01221. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, K.; Feng, G.; Zhang, X. Robust image watermarking based on generative adversarial network. China Commun. 2020, 17, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wu, Y.; Chen, B. Embedding guided end-to-end framework for robust image watermarking. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2022, 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, G.; Chen, S.; Wang, C.; Li, J. Single exposure optical image watermarking using a cGAN network. IEEE Photonics J. 2021, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.; Osindero, S. Conditional generative adversarial nets. arXiv preprint 2014, arXiv:1411.1784. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C. Attention based data hiding with generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. AAAI: New York, NY, USA; 2020; Vol. 34, pp. 1120–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, S.M.; Nam, S.H.; Jang, H.U.; Kim, D.; Lee, H.K. A robust blind watermarking using convolutional neural network. arXiv preprint 2017, arXiv:1704.03248. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, F.; Lin, G. Multi-dimensional particle swarm optimization for robust blind image watermarking using intertwining logistic map and hybrid domain. Soft Comput. 2020, 24, 10561–10584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks; IEEE: Perth, WA, Australia, 1995; Vol. 4, pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, M.; Goyal, S. A hybrid digital image watermarking technique based on fuzzy-BPNN and shark smell optimization. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 39471–39489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhong, D.; Shao, H. Data protection in palmprint recognition via dynamic random invisible watermark embedding. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 6927–6940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhou, X.; Qin, Z. DARI-Mark: Deep learning and attention network for robust image watermarking. Mathematics 2022, 11, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In Proceedings of the 13th European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer: Zurich, Switzerland; 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latecki, L. Shape data for the MPEG-7 core experiment ce-shape-1. Web Page: http://www.cis.temple.edu/latecki/TestData/mpeg7shapeB. tar. gz 2002, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, A.G. The USC-SIPI image database: Version 5. http://sipi.usc.edu/database/ 2006.

- Bas, P.; Filler, T.; Pevnỳ, T. Break our steganographic system: The ins and outs of organizing BOSS. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Information Hiding, Prague, Czech Republic; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Nair, V.; Hinton, G. Cifar-10 and cifar-100 datasets. URl: https://www.cs.toronto.edu/kriz/cifar.html 2009, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, M.; Norouzi, A.; Karimi, N.; Samavi, S.; Emami, A. ReDMark: Framework for residual diffusion watermarking based on deep networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 146, 113157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Wu, G.; Yu, X.; Liu, B. A robust blind watermarking scheme based on attention mechanism and neural joint source-channel coding. In Proceedings of the IEEE 24th International Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing. IEEE: Shanghai, China; 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Du, J.; Jia, Y.; Zhu, H. Zero-watermarking algorithm for medical image based on VGG19 deep convolution neural network. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021, 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Xiang, R.; Liu, J.; Pan, R.; Zhang, Z. An invisible and robust watermarking scheme using convolutional neural networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 210, 118529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatys, L.A.; Ecker, A.S.; Bethge, M. Image style transfer using convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE: Las Vegas, NV, USA; 2016; pp. 2414–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Dong, W.; Tian, Y. A novel generalized Arnold transform-based zero-watermarking scheme. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 2015, 4, 2023–2035. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, C.; Liu, J.; Gong, M.; Li, J.; Bhatti, U.A.; Ma, J. Robust medical zero-watermarking algorithm based on residual-DenseNet. IET Biom. 2022, 11, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Xiang, S. Cover-lossless robust image watermarking against geometric deformations. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 30, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellimi, S.; Rajput, V.; Ansari, I.A.; Ahn, C.W. A fast and efficient image watermarking scheme based on deep neural network. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2021, 151, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Li, Z.; Gao, J. DwiMark: A multiscale robust deep watermarking framework for diffusion-weighted imaging images. Multimedia Syst. 2022, 28, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everingham, M.; Eslami, S.A.; Van Gool, L.; Williams, C.K.; Winn, J.; Zisserman, A. The pascal visual object classes challenge: A retrospective. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 111, 98–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Duanmu, Z.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yong, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, L. Waterloo exploration database: New challenges for image quality assessment models. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2016, 26, 1004–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Kaplan, R.; Johnson, J.; Fei-Fei, L. Hidden: Hiding data with deep networks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer: Munich, Germany; 2018; pp. 657–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xie, X. A novel two-stage separable deep learning framework for practical blind watermarking. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia. ACM: New York, NY, USA; 2019; pp. 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wu, Y.; Coatrieux, G.; Chen, X.; Zheng, Y. JSNet: A simulation network of JPEG lossy compression and restoration for robust image watermarking against JPEG attack. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2020, 197, 103015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE: Miami, FL, USA; 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Z.; Fang, H.; Zhang, W. MBRS: Enhancing robustness of DNN-based watermarking by mini-batch of real and simulated JPEG compression. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia. ACM: New York, NY, USA; 2021; pp. 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Karjauv, A.; Benz, P.; Kweon, I.S. Towards robust data hiding against (JPEG) compression: A pseudo-differentiable deep learning approach. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2101.00973. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, R.; Guo, M.; Hou, Y.; Yang, F.; Li, Y.; Jia, H.; Xie, X. Towards blind watermarking: Combining invertible and non-invertible mechanisms. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia. ACM: New York, NY, USA; 2022; pp. 1532–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.H.; Chuang, Y.Y. Target-driven moire pattern synthesis by phase modulation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. IEEE: Sydney, NSW, Australia; 2013; pp. 1912–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, W.; Ye, H. A blind watermarking system based on deep learning model. In Proceedings of the IEEE 20th International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications. IEEE: Shenyang, China; 2021; pp. 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Huang, P.C.; Mastorakis, S.; Shih, F.Y. An automated and robust image watermarking scheme based on deep neural networks. IEEE Trans. Multimedia 2020, 23, 1951–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lin, C.; Zhao, Q.; Zhu, F. Watermark faker: Towards forgery of digital image watermarking. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo. IEEE: Shenyang, China; 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Chen, D.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yu, N. Deep template-based watermarking. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2020, 31, 1436–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Zhang, W.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, H.; Sun, S.; Cui, H.; Yu, N. A camera shooting resilient watermarking scheme for underpainting documents. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2019, 30, 4075–4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Chen, D.; Wang, F.; Ma, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, W.; Yu, N. Tera: Screen-to-camera image code with transparency, efficiency, robustness and adaptability. IEEE Trans. Multimedia 2021, 24, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, R.C.; Ray-Chaudhuri, D.K. On a class of error correcting binary group codes. Information and Control 1960, 3, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramila, A.; Keskinarkaus, A.; Seppänen, T. Toward an interactive poster using digital watermarking and a mobile phone camera. Signal, Image and Video Processing 2012, 6, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugelmann, D.; Sommer, D.; Lenders, V.; Happe, M.; Vanbever, L. Screen watermarking for data theft investigation and attribution. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Cyber Conflict; IEEE: Tallinn, Estonia, 2018; pp. 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Chen, J.; Peng, C.; Li, Y.; Sun, W. Watermark-preserving keypoint enhancement for screen-shooting resilient watermarking. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo. IEEE: Taipei, Taiwan; 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Lu, J.; Chang, C.C. SSDeN: Framework for screen-shooting resilient watermarking via deep networks in the frequency domain. Appl. Sci.-Basel. 2022, 12, 9780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ni, J.; Su, W.; Xie, H. Wavelet-based CNN for robust and high-capacity image watermarking. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo. IEEE: Taipei, Taiwan; 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boujerfaoui, S.; Douzi, H.; Harba, R.; Gourrame, K. Robust Fourier watermarking for print-cam process using convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Signal and Image Processing. IEEE: Suzhou, China; 2022; pp. 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Gao, Z.; Chen, K.; Hu, M.; Min, X.; Zhai, G.; Yang, X. RIHOOP: Robust invisible hyperlinks in offline and online photographs. IEEE T. Cybern. 2020, 52, 7094–7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Jia, Z.; Ma, Z.; Chang, E.C.; Zhang, W. PIMoG: An effective screen-shooting noise-layer simulation for deep-learning-based watermarking network. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia. ACM: New York, NY, USA; 2022; pp. 2267–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, I.; Chang, H.; Luo, X.; Stava, O.; Liu, C.; Milanfar, P.; Yang, F. Deep 3D-to-2D watermarking: Embedding messages in 3D meshes and extracting them from 2D renderings. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE: New Orleans, LA, USA; 2022; pp. 10031–10040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tancik, M.; Mildenhall, B.; Ng, R. Stegastamp: Invisible hyperlinks in physical photographs. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE: Seattle, WA, USA; 2020; pp. 2117–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 18th International Coference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer: Munich, Germany; 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huiskes, M.J.; Lew, M.S. The mir flickr retrieval evaluation. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM International Conference on Multimedia Information Retrieval. ACM: New York, NY, USA; 2008; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Song, S.; Khosla, A.; Yu, F.; Zhang, L.; Tang, X.; Xiao, J. 3D shapenets: A deep representation for volumetric shapes. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE: Boston, MA, USA; 2015; pp. 1912–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.P.; Fan, T.Y.; Chao, H.C. Wmnet: A lossless watermarking technique using deep learning for medical image authentication. Electronics 2021, 10, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhu, C.; Ren, N. A zero-watermark algorithm for copyright protection of remote sensing image based on blockchain. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Blockchain Technology and Information Security. IEEE: Huaihua City, China; 2022; pp. 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhan, R.; Chang, H.; Yang, F.; Milanfar, P. Distortion agnostic deep watermarking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE: Seattle, WA, USA; 2020; pp. 13548–13557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Karjauv, A.; Benz, P.; Kweon, I.S. Towards robust deep hiding under non-differentiable distortions for practical blind watermarking. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 5158–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Dong, Q.; Fu, A. WMDefense: Using watermark to defense byzantine attacks in federated learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops. IEEE: New York, NY, USA; 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Meng, C.; Ermon, S. Denoising diffusion implicit models. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2010.02502. [Google Scholar]

- Dhariwal, P.; Nichol, A. Diffusion models beat GANs on image synthesis. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 8780–8794. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Year | Type of Forgery | Number of Forged Images/ Authentic Images | Image Format | Image Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columbia color [19] | 2006 | Splicing | 183/180 | BMP, TIF | 757 × 568 – 1152 × 768 |

| MICC-F220 [20] | 2011 | Copy-move | 110/1100 | JPG | 480 × 722 – 1070 × 800 |

| MICC-F600 [20] | 2011 | Copy-move | 160/440 | JPG, PNG | 722 × 480 – 800 × 600 |

| MICC-F2000 [20] | 2011 | Copy-move | 700/1300 | JPG | 2048 × 1536 |

| CASIA V1 [21] | 2013 | Copy-move, Splicing | 921/800 | JPG | 284 × 256 |

| CASIA V2 [21] | 2013 | Copy-move, Splicing | 5123/7200 | JPG, BMP, TIF | 320 × 240 – 800 × 600 |

| Carvalho [22] | 2013 | Splicing | 100/100 | PNG | 2048 × 1536 |

| CoMoFoD [23] | 2013 | Copy-move | 4800/4800 | PNG, JPG | 512 × 512 – 3000 × 2500 |

| COVERAGE [24] | 2016 | Copy-move | 100/100 | TIF | 2048 × 1536 |

| Korus [25] | 2017 | Copy-move, Splicing | 220/220 | TIF | 1920 × 1080 |

| USCISI [26] | 2018 | Copy-move | 100000/- | PNG | 320 × 240 – 640 × 575 |

| MFC 18 [27] | 2019 | Multiple manipulation | 3265/14156 | RAW, PNG, BMP, JPG, TIF | 128 × 104 – 7952 × 5304 |

| DEFACTO [28] | 2019 | Multiple manipulation | 229000/- | TIF | 240 × 320 – 640 × 6405 |

| IMD 2020 [29] | 2020 | Multiple manipulation | 37010/37010 | PNG, JPG | 193 × 260 – 4437 × 2958 |

| Ref. | Year | Type of Detection | Backbone | Robustness Performance | Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. [38] | 2022 | Copy-move forgery | VGG 16, Atrous convolution | Brightness change, Image blurring, JPEG compression, Color reduction, Contrast adjustments, Noise adding | USCISI, CoMoFoD, CASIA V2 |

| Liu et al. [41] | 2022 | Copy-move forgery | VGG 16, SuperGlue | Rotation, Scaling, Noise adding, JPEG compression | Self-datasets |

| Zhong et al. [42] | 2020 | Copy-move forgery | DenseNet | Rotation, Scaling, Noise adding, JPEG compression | FAU, CoMoFoD, CASIA V2 |

| Kafali et al. [43] | 2021 | Copy-move forgery | VGG 16, Volterra convolution | Brightness change, Image blurring, JPEG compression, Color reduction, Contrast adjustments, Noise adding | USCISI, CoMoFoD, CASIA |

| Nazir et al. [44] | 2022 | Copy-move forgery | DenseNet, RCNN | Brightness change, Image blurring, JPEG compression, Color reduction, Contrast adjustments, Noise adding | CoMoFoD, MICC-F2000, CASIA V2 |

| Zhong et al. [46] | 2022 | Copy-move forgery | DenseNet | Brightness change, Image blurring, JPEG compression, Color reduction, Contrast adjustments, Noise adding | IMD, CoMoFoD, CMHD [76] |

| Wu et al. [26] | 2018 | Copy-move forgery | VGG 16 | Brightness change, Image blurring, JPEG compression, Color reduction, Contrast adjustments, Noise adding | USCISI, CoMoFoD, CASIA V2 |

| Chen et al. [47] | 2021 | Copy-move forgery | VGG 16, Attention module | Brightness change, Image blurring, JPEG compression, Color reduction, Contrast adjustments, Noise adding | USCISI, CoMoFoD, CASIA V2, COVERAGE |

| Aria et al. [48] | 2022 | Copy-move forgery | VGG 16 | Brightness change, Image blurring, JPEG compression, Color reduction, Contrast adjustments, Noise adding | USCISI, CoMoFoD, CASIA V2 |

| Barni et al. [49] | 2021 | Copy-move forgery | ResNet 50 | JPEG compression, Noise, Scaling | SYN-Ts, USCISI, CASIA, Grip [77] |

| Wei et al. [53] | 2021 | Splicing forgery | U-Net, Ringed residual structure | JPEG compression, Gaussian noise, Combined attack, Scaling, Rotation | CASIA, Columbia |

| Zeng et al. [54] | 2022 | Splicing forgery | U-Net, ASPP | JPEG compression, Gaussian blurring | CASIA |

| Zhang et al. [55] | 2021 | Splicing forgery | U-Net, SEAM | JPEG compression, Scaling, Gaussian filtering, Image sharpening | Columbia, CASIA, Carvalho |

| Chen et al. [56] | 2020 | Splicing forgery | FCN | JPEG compression, Gaussian blur, Gaussian noise | DVMM [78], CASIA, NC17, MFC18 |

| Zhuang et al. [57] | 2021 | Splicing forgery | FCN | JPEG compression, Scaling | PS-scripted dataset, NIST16 [27] |

| Liu et al. [58] | 2022 | Splicing forgery | FCN, SRM | Gaussian noise, JPEG compression, Gaussian blurring | CASIA, Columbia |

| Ren et al. [59] | 2022 | Splicing forgery | ResNet 50 | JPEG compression, Gaussian noise, Scaling | CASIA, IMD2020, DEFACTO, SMI20K |

| Sun et al. [60] | 2022 | Splicing forgery | Transformer | JPEG compression, Media blur, Scaling | CASIA, NC2016 [79] |

| Zhang et al. [61] | 2022 | Multiple types of tampering detection | ResNet 34, Non-local module | JPEG compression, Gaussian blur | CASIA, COVERAGE, Columbia, NIST16 |

| Dong et al. [62] | 2023 | Multiple types of tampering detection | ResNet 50 | JPEG compression, Gaussian blur | CASIA V2,COVERAGE, Columbia, NIST16 |

| Chen et al. [63] | 2023 | Multiple types of tampering detection | ResNet 101 | JPEG compression, Gaussian blur, Median blur | Self-datasets, NIST16, Columbia, CASIA |

| Lin et al. [64] | 2023 | Multiple types of tampering detection | ResNet 50, Swin transformer | JPEG compression, Gaussian blur, Gaussian noise | CASIA, NIST16, Columbia, COVERAGE, CoMoFoD |

| Wang et al. [65] | 2022 | Multiple types of tampering detection | Multimodal transformer | JPEG compression, Gaussian blur, Gaussian noise, Scaling | CASIA, Columbia, Carvalho, NIST16, IMD2020 |

| Liu et al. [66] | 2022 | Multiple types of tampering detection | HR-Net | JPEG compression, Scaling, Gaussian blur, Gaussian noise | Columbia, COVERAGE, CASIA, NIST16, IMD2020 |

| Shi et al. [67] | 2022 | Multiple types of tampering detection | VGG 19, Rotated residual | JPEG compression, Gaussian blur, Gaussian noise | NIST16, COVERAGE, CASIA, In-The-Wild |

| Gao et al. [68] | 2022 | Multiple types of tampering detection | ResNet 101 | JPEG compression, Scaling | CASIA, Carvalho, COVERAGE, NIST16, IMD2020 |

| Ganapathi et al. [69] | 2022 | Multiple types of tampering detection | HR-Net | Flipped horizontally and vertically, Saturation, Brightness | CASIA V2, NIST16, Carvalho, Columbia |

| Xu et al. [70] | 2022 | Multiple types of tampering detection | VGG 16 | JPEG compression, Scaling, Gaussian blur, Gaussian noise | NIST16, COVERAGE, CASIA, IMD2020 |

| Rao et al. [71] | 2022 | Multiple types of tampering detection | Residual unit, CRF-based attention, ASPP | JPEG compression, Scaling | COVERAGE, CASIA, Carvalho, IFC |

| Li et al. [72] | 2022 | Multiple types of tampering detection | ResNet101, Faster R-CNN | Median filtering, Gaussian noise, Gaussian blur, Resampling | CASIA, Columbia, COVERAGE, NIST16 |

| Yin et al. [73] | 2022 | Multiple types of tampering detection | Convolution and Residual block | JPEG compression, Gaussian blur, Gaussian noise, Scaling | NIST16, CASIA, COVERAGE, Columbia |

| Zhou et al. [74] | 2022 | Multiple types of tampering detection | VGG-style block | JPEG compression, Gaussian noise, Gaussian blur, Scaling | DEFACTO, Columbia, CASIA, COVERAGE, NIST16 |

| Ren et al. [75] | 2022 | Multiple types of tampering detection | ResNet 50 | JPEG compression, Gaussian noise, Scaling | NIST16, CASIA, MSM30K |

| Ref. | Watermark Size (Container Size) |

Category | Method (Effect) | Robustness (Attack, Parameter) | Dataset | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BER (%) | NC | |||||

| Hao et al. [84] | 30 (64 × 64) |

GAN-based | GAN (Improving visual quaility) | 0.5 (Gaussian blur, 3 × 3, = 2.0) | – | COCO [95] |

| Mun et al. [89] | 24 (512 × 512) |

Embedding parameter optimization | CNN (Feature extraction) | – | 0.9625 (Gaussian blur, 3 × 3, = 1) | MPEG-7 CE Shape-1 [96] |

| Kang et al. [90] | 1024 (1024 × 1024) |

Embedding parameter optimization | PSO (Selecting best DCT coefficient) | 0 (Gaussian filtering, 3 × 3, = 0.5) | 0.990 (Gaussian filtering, 3 × 3, = 0.5) | USC-SIPI [97] |

| Rai et al. [92] | 32 (96 × 96) |

Embedding parameter optimization | SSO (Gaining ideal embedding parameter) | – | 0.8259 (Gaussian noise, = 0.01) | Self-datasets |

| Zhao et al. [94] | 32 × 32 (512 × 512) |

Embedding parameter optimization | Spatial and channel attention mechanism (Improving robustness) | 0.09 (Gaussian noise, = 0.05) | 0.9988 (Gaussian noise, = 0.05) | BOSS Base [98], CIFAR 10 [99] |

| Ref. | Watermark Size (Container Size) |

Category | Method (Effect) | Robustness (Attack, Parameter) | Dataset | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BER (%) | NC | |||||

| Ahmadi et al. [100] | 1024 (512 × 512) |

Transform domain-based | Circular convolution (Diffusing watermark information), Residual connection (Fusing low-level character) | 5.9 (Scaling, = 0.5) |

– | CIAFAR 10 [99], Pascal VOC [111] |

| Mei et al. [101] | 1024 (512 × 512) |

Transform domain-based | DCT, Attention, Joint source-channel coding (Improving robustness) | 0.96 (Cropping, = 0.75), 0.34 (Cropping, = 0.5) |

– | COCO [95] |

| Han et al. [102] | – | Zero- watermark |

VGG19, DFT (Feature extraction) | – | 0.87509 | |

| ( = 50) | Self-datasets | |||||

| Liu et al. [104] | – | Zero- watermark |

VGG19 (Feature extraction) | – | 0.95 ( = 40), 0.96 (Scaling, = 0.5) |

Waterloo Exploration Database [112] |

| Gong et al. [107] | – | Zero- watermark |

Residual-DenseNet (Feature extraction) | – | 0.89 (Rotation, = 45) |

Self-datasets |

| Hu and Xiang [108] | 128 (512 × 512) |

Robust feature-based | CNN (Feature extraction), GAN (Visual improvement) | 0.6 (Scaling, = 2) |

– | USC-SIPI [97] |

| Mellimi et al. [109] | 1024 (512 × 512) |

Robust feature-based | DNN (Optimal embbeding subband selection) | 1.78 (Scaling, = 0.65), 0.2 (Scaling, = 0.75) |

0.9353 (Scaling, = 0.65), 0.9930 (Scaling, = 0.75) |

USC-SIPI [97] |

| Ref. | Watermark Size (Container Size) |

Method | Structure | Robustness (BER (%, )) |

Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmadi et al. [100] | 1024 (512 × 512) |

Differentiable approximation | CNN, Residual connection, Circular convolution | 1.2 (50), 0 (70), 0 (90) |

CIFAR 10 [99], Pascal VOC [111] |

| Liu et al. [114] | 30 (128 × 128) |

Specific decoder training | CNN, GAN | 23.8 (50) | COCO [95], CIFAR 10 [99] |

| Chen et al. [115] | 1024 (256 × 256) |

Network structure improvement | CNN, JSNet | 0.097 (90), 32.421(80) | ImageNet [116], Boss Base [98] |

| Jia et al. [117] | 64 (128 × 128) |

Network structure improvement | CNN, Residual connection | 4.14 (50) | COCO [95] |

| Zhang et al. [119] | 30 (128 × 128) |

One-stage end-to-end | Backward ASL | 12.64 | – |

| Ma et al. [120] | 30 (128 × 128) |

Network structure improvement | DEM, Non-invertible attention module | 0.76 (50) | COCO [95] |

| Ref. | Watermark Size (Container Size) |

Category | Robustness (BER (%)) | Dataset | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance (cm) | Angle (°) | ||||

| Fang et al. [125] | 128 (512 × 512) |

Templated- based | 1.95 (20), 2.73 (40), 11.72 (60) | 4.3 (Up40), 1.17 (Up20), 7.03 (Down20), 7.03 (Down40), 5.47 (Left40), 3.91 (Left20), 2.73 (Right20), 3.52 (Right40) | ImageNet [116], USC-SIPI [97] |

| Fang et al. [126] | 48 (256 × 256) |

Decoding based on attention mechanism | 5.1 (15), 9.9 (35) | 9.4 (Up45) 8.1 (Up30), 8.9 (Down30), 9.45 (Down45), 9.7 (Left45), 8.9 (Left30) , 9.8 (Right30), 9.3 (Right45) | Self-datasets |

| Fang et al. [127] | 32 (512 × 512) |

Distortion compensation | 2.54 (30), 3.71 (50), 5.27 (70) | 6.25 (Up30), 3.13 (Up15), 12.73 (Down15), 14.12 (Down30), 7.05 (Left15), 14.46 (Left40), 5.27 (Right15), 11.52 (Right30) | COCO [95] |

| Dong et al. [131] | 64 (64 × 64) |

Key point enhancement | 0.43 (45), 0.35 (65) , 0.67 (75) | 2.0 (Left60), 0.66 (Left30), 0.67 (Right30), 2.68 (Right60) | Self-datasets |

| Jia et al. [135] | 100 (400 × 400) |

Distortion simulation | – | 1.0 (Left65), 0.7 (Left30), 0.7 (Right30), 5.3 (Right65) | Pascal VOC [111], USC-SIPI [97] |

| Fang et al. [136] | 30 (128 × 128) |

Tamper detection | 2.08 (40), 1.25 (60), 0.62 (20) | 2.92/1.25 (Left/Up40), 1.25/0.93 (Left/Up20), 1.05/1.04 (Right/Down20), 0.62/0.83 (Right/Down40) | USC-SIPI [97] |

| Ref. | Watermark Size (Container Size) |

Category | Robustness (BER (%)) | Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lu et al. [133] | 400 (400 × 400) |

Transform domain | 11.18 | MIR Flickr [140] |

| Yoo et al. [137] | – | Distortion simulation | 9.72 ( = 30) | ModelNet 40-class [141] |

| Tancik et al. [138] | 100 (400 × 400) |

Distortion simulation | 0.2 | ImageNet [116] |

| Ref. | Watermark Size (Container Size) |

Category | Structure | Robustness (Attack, Parameter) | Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al. [119] | 30 (128 × 128) |

One-stage end-to-end | Backward ASL | BER: 12.64 (JPEG, = 50) | – |

| Zhang et al. [122] | 64 (224 × 224) |

Two-stage separable training | CNN, GAN, Attack classification discriminator, Residual network | BER: 18.54 (JPEG, = 50), 8.47 (Cropping, = 0.7), 11.79 (Rotation, 15), 1.27 (Salt and pepper noise, = 0.01), 1.9 (Gauss filtering, 3 × 3, = 2) | Pascal VOC [111] |

| Zhong et al. [123] | 32 × 32 (128 × 128) |

One-stage end-to-end training | Multi-scale convolution blocks, Invariance layer | BER: 8.16 (JPEG, = 10), 6.61 (Cropping, 0.8), 0.97 (Salt and pepper, = 0.05) | ImageNet [116], CIFAR 10 [99] |

| Chen et al. [142] | 64 × 64 (512 × 512) |

No attack training | WMNet, CNN | Classification accuracy: 0.978 | - |

| Luo et al. [144] | 30 (128 × 128) |

No attack training | Channel coding, CNN, GAN | BER: 10.5 (Gaussian noise, = 0.1), 22.9 (Salt and pepper noise, = 0.15) | COCO [95] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).