1. Introduction

The phytochemical compound, thymoquinone, found in the oil of the Nigella sativa seeds, commonly known as black seed, has shown promise in the realm of medicinal therapeutics. Originating from southwestern Asia, the Mediterranean, and Africa, the black seed plant has been traditionally hailed for its medicinal properties across various cultures. The potent volatile oil from its seeds, rich in thymoquinone, exhibits a wide array of pharmacological effects. These span from antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity to anticancer properties, positioning thymoquinone as a potential agent in preventing and treating a multitude of health conditions [

1,

2].

Thymoquinone’s remarkable antioxidant property is associated with its ability to neutralize free radicals and reactive oxygen species, key players in the pathogenesis of numerous diseases. Consequently, it is suggested to have protective potential against conditions related to oxidative stress, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer. Additionally, its potent anti-inflammatory effects inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory mediators, indicating a possible therapeutic benefit in inflammation-associated conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease [

3]. Beyond these, thymoquinone also displays antihistaminic, hypoglycemic, hypolipidemic, and antimicrobial effects, further broadening its interest in a range of health conditions [

4]. Its anticancer activity, demonstrated in various preclinical trials, is particularly noteworthy. Thymoquinone has shown an ability to inhibit the proliferation of different cancer cell lines and induce apoptosis - programmed cell death that is critical in preventing cancer proliferation [

5]. Moreover, its antitumor effects are multifaceted, modulating various molecular pathways involved in cell proliferation, apoptosis, and metastasis, including p53, p38, and STAT3. Research indicates its potential against various types of cancer, such as breast, colorectal, pancreatic, lung, and prostate, where it inhibits tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis [

6,

7]. Despite the promising preclinical findings, clinical trials in humans are imperative to validate these results and determine the safety, efficacy, and optimal dosage of thymoquinone.

A study focusing specifically on acute myeloid leukemia revealed that thymoquinone could induce the re-expression of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) that had been silenced by epigenetic mechanisms, notably DNA methylation. In the study, the acute myeloid leukemia cells treated with thymoquinone showed a significant inhibition of growth and increased apoptosis in a dose- and time-dependent manner. This was attributed to thymoquinone’s ability to bind the active pocket of JAK2, STAT3, and STAT5, inhibiting their enzymatic activity. Furthermore, it was observed that thymoquinone significantly enhanced the re-expression of SHP-1 and SOCS-3, two of the TSGs, via demethylation. Such mechanisms suggest thymoquinone's potential as a therapeutic agent in the treatment of AML patients [

8].

Telomerase is a specialized ribonucleoprotein enzyme, which plays a vital role in maintaining the ends of chromosomes by appending telomeric repeats to these termini. This process is carried out using its own template RNA component, while the human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) catalytic subunit lends the enzymatic activity necessary for the function. In nearly 90% of tumor cells, including leukemic cells, telomerase activity is observed, whereas it is typically absent in adjacent normal cells [

9]. This overexpression seems paradoxical, considering the association between telomerase deficiency and the incidence of leukemia. Nevertheless, telomere attrition or the gradual loss of telomeric DNA, has been proposed as a molecular mechanism that fosters genomic instability and predisposes cells to tumor development. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that for a tumor cell to sustain stable and continuous proliferation, it must reactivate telomerase. This makes telomerase a promising target for cancer therapy [

10,

11].

In light of these findings, our research hypothesis is to inhibit the telomerase enzyme using thymoquinone encapsulated in sulfobutylether-β-cyclodextrin. We propose that the successful pharmacological inhibition of the telomerase enzyme will prevent the growth and proliferation of leukemic cancer cells. This approach provides a promising new avenue for leukemia therapy and warrants further investigation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of the Inclusion Complex

We applied a lyophilization technique to formulate the inclusion complex of thymoquinone with Sulfobutylether-β-cyclodextrin (SBE-β-CD), replicating the process detailed in our prior research [

12,

13] . We mixed a balanced 1:1 molar combination of TQ and SBE-β-CD, dissolving it in 20 mL of ultrapure water. This solution was subsequently agitated in a rotary shaker at ambient temperature for an extended period of 72 hours before being strained through a 0.45 μm filter. The resultant translucent solution was flash-frozen at an extremely low temperature of -80 °C, after which it underwent a lyophilization process at -55 °C lasting a full day.

2.2. Cytotoxicity

Leukaemia cells (K-562, ATCC, USA, Cat. CCL-243) cells were grow in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM) (ATCC, USA Cat. 30-2005) that supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% of penicillin 10,000 I.U./mL & 10,000 (μg/mL) streptomycin solution (ATCC, USA, Cat. 30-2300). 10,000 K-562 cells were plated in each well of tissue culture microplate with a clear bottom. Then were treated with a 2-fold serial range of concentrations of Sulfobutylether-β-Cyclodextrin (SBE-β-CDs; 5.72 - 0.04 mg/ml), TQ (TQ; 100–0.78 μg/ml), or TQ / SBE-β-CDs complex (100–0.78 μg/ml). The negative control was without any treatment. After incubating for 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours in a 37 ºC, 5% CO

2 incubator, the Cell Counting Kit 8 (WST-8/CCK8) solution was added directly to the test and incubated cells for two hours. Lastly the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using VersaMax reader (Molecular Devices, LLC, USA). Cell toxicity percentage was calculated using equation No.1 [

14].

2.3. Caspase-Glo® 3/7, 8 and 9 Assays

Caspase-Glo® 3/7, 8 and 9 enzymes assay were measured in 96-Well Plate using Caspase-Glo® 3/7 Assay, Caspase-Glo® 8 Assay and Caspase-Glo® 9 Assay kites (Promega, USA, Cat. G8091, Cat. G8201, and Cat. G8211 respectively), accursing to the manufacturer instructions. Briefly, after 96 hrs of the incubating the K-562 cells with SBE-β-CDs (0.36, 0.72 and 1.43 mg/ml), TQ (6.25, 12.5 and 25 µg/ml) or TQ /SBE-β-CDs complex (6.25, 12.5 and 25 µg/ml). The negative control was vehicle-treated cells in a medium. Each caspase had a separate well set, 100 µl of Caspase-Glo Reagent was added to each well of a white-walled plate containing 100 µl of negative control cells or treated cells in a culture medium. Then contents of the wells were gently mixed using a plate shaker at 300–500rpm for 30 seconds and incubated at room temperature for one hour. The luminescence of each sample was measured in a plate-reading luminometer.

2.4. Annexin-V/PI Flow-Cytometry Protocol

K-562 cells (1 × 106 cells) were seeded in a T25 culture flask (in triplicate) and three T25 culture flasks for control (unstained, annexin stained only, and propidium iodide (PI) stained only). After 96 hrs incubation with different treatments (i.e., SBE-β-CDs (0.72 mg/ml), TQ (12.5 µg/ml) or TQ /SBE-β-CDs complex (12.5 µg/ml), the cells were collected from each T25 flask. The cells were washed in 2 mL 1 x PBS (no calcium, no magnesium). Then, cells were resuspended in 1 mL 1 x Annexin V binding buffer. After, centrifuging and decanting the supernatant, the cells were resuspended in 100 μL 1 x Annexin V binding buffer with 5 μL (or 1ug/ml) Annexin V Alexa Fluor 488. After 15 minutes of incubation, 100 μL 1 x Annexin V binding buffer with 4 μL of PI (100 µg/ml) and incubated in the dark for 15 minutes at room temperature. Lastly, the cells were analysed using a flow cytometer (BD FACSCanto II) with 10,000 events.

2.5. Telomerase Activity Quantification qPCR Assay (TAQ)

Telomerase Activity Quantification qPCR Assay (TAQ) kit (ScienCell Research Laboratories, USA, Catalog #8928) was used accursing to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 2-5 million cells were harvested and washed with PBS. The cell pellets, cell lysates and reagents were maintained on the ice during the experiment. For every millilitre of cell lysis buffer, 1μL of 0.1M PMSF and 0.3 μL of 14.3M β-mercaptoethanol was added before use. After lysing, the samples were spined at 12,000x g for 20 minutes at 4 °C. Then 15 μL of supernatant was transferred to a new pre-chilled tube. Telomerase reaction was prepared by mixing 0.5 μL cell lysate sample or cell lysis buffer (as negative control), 4 μl Telomerase reaction buffer and 15.5 μl nuclease-free H

2O. The reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 3 hours then stopped by heating the samples at 85 °C for 10 minutes. Finally, qPCR reactions were prepared by mixing 1 μl of post-telomerase reaction sample, 2 μl of primer, 10 μl of GoldNStart TaqGreen qPCR Mastermix, and 7 μl nuclease-free H

2O. A qPCR program was set up according to manufacturer instructions. Finally, qPCR was done to analyse the telomer production by telomerase. Quantification cycle (ΔCq) was calculated by the following equation (2), the relative telomerase reduction activity, compared to the untreated cells, was calculated using the equation (3).

2.6. Molecular Docking

The molecular docking studies were performed using AutoDock VINA (V. 1.1.2) [

15] to elucidate the potential interactions of two complexes: SBE-ß-CDs with TQ and telomerase with TQ. The 3D structures of the SBE-ß-CDs and TQ were retrieved from the PubChem and the telomerase from Protein Data Bank (PDB) (ID: 2BCK). Hydrogens were added to the structures, non-polar hydrogens were merged, and Gasteiger charges were computed using AutoDockTools. The grid box for docking was defined around the binding site of the respective proteins with a suitable spacing to cover the entire protein. Each docking experiment was carried out with an exhaustiveness of 100 to ensure a thorough search of the conformational space. Following docking, the resultant complexes were ranked based on their binding affinities, and the top-ranked conformation was selected for further analysis. Post-docking analyses were performed using Discovery Studio Visualizer to inspect the interaction profiles, including hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, between the proteins and TQ.

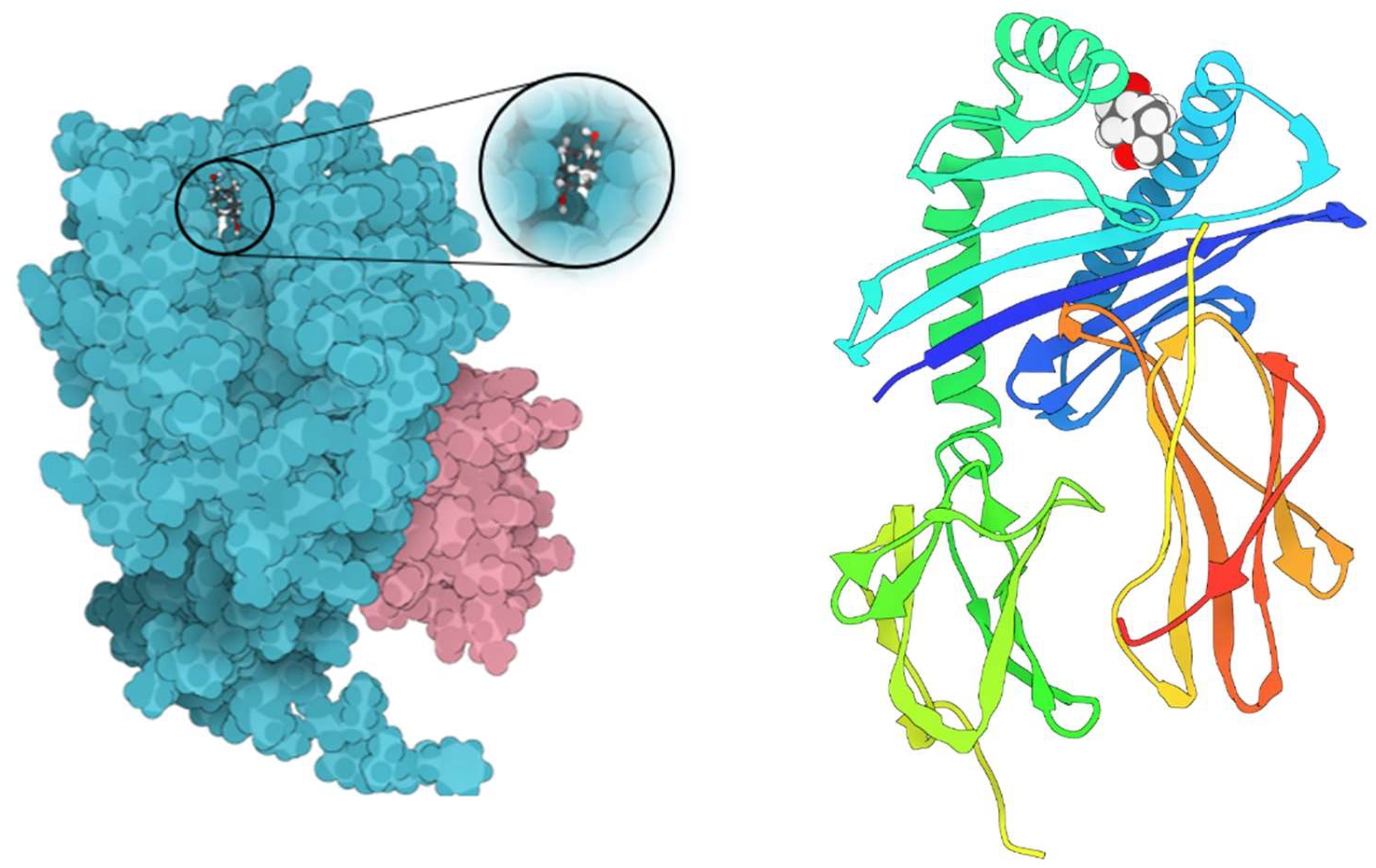

2.7. Molecular Dynamic Simulation

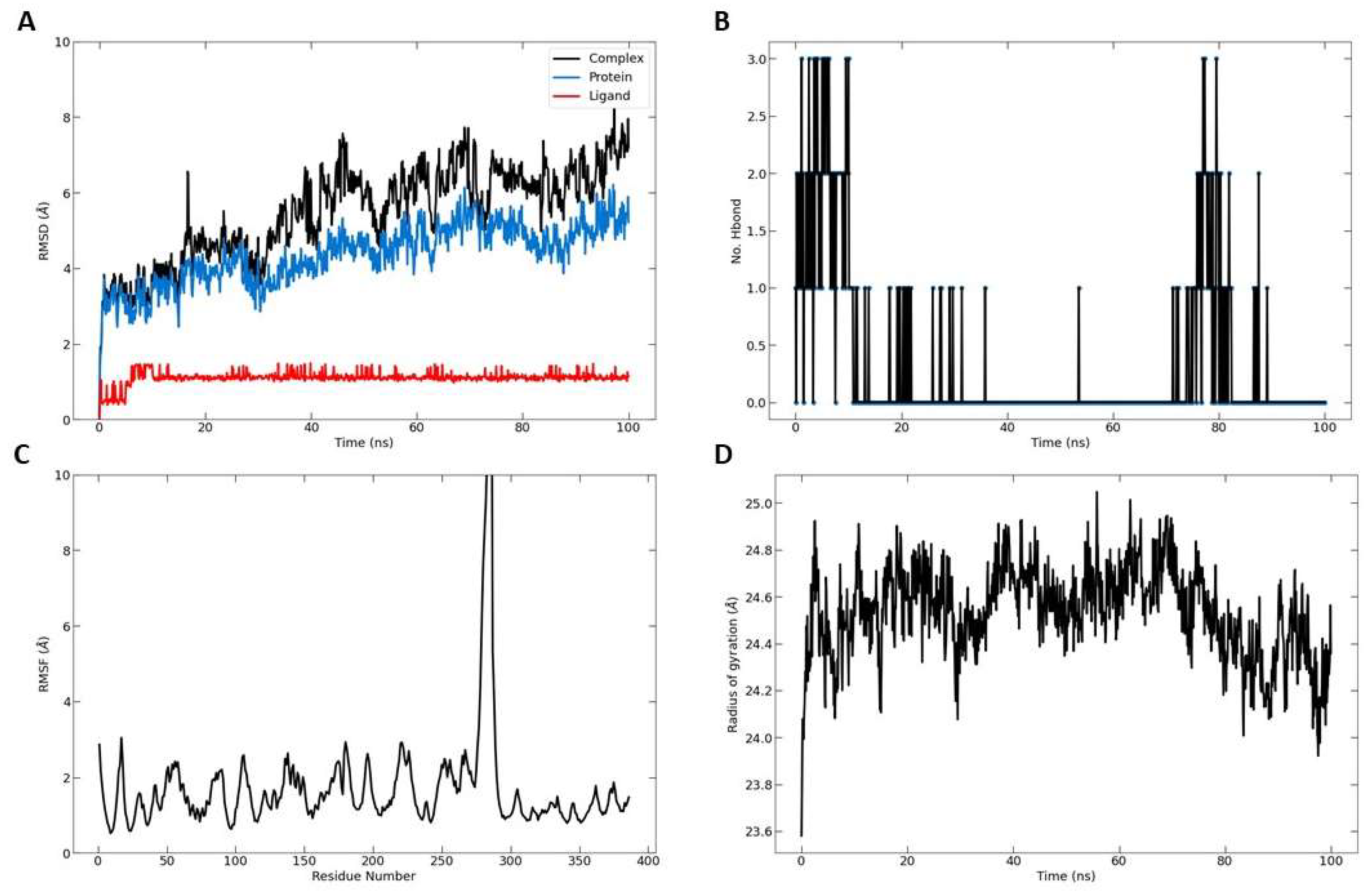

The molecular dynamics simulation was carried out using the Nanoscale Molecular Dynamics (NAMD) software to investigate the interaction of the telomerase-TQ complex. The 3D structure of the complex was sourced from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and any missing residues or atoms were added using the Swiss PDB viewer, ensuring the protonation states of the ionizable residues were assigned at physiological pH. The CHARMM (Chemistry at HARvard Macromolecular Mechanics) force field was employed to define the potential energy function for the simulation, while parameters for TQ were generated using the SwissParam tool. Subsequently, the complex was solvated in a cubic box of TIP3P water molecules that extended 20 Å beyond the complex in every direction. Counter ions were then introduced to neutralize the system, with physiological salt concentration attained by incorporating NaCl. To alleviate steric clashes and relax the system, an energy minimization was performed using the conjugate gradient method. Following this, the system was gradually heated to 37 C over a period of 100 ps and then equilibrated under constant temperature and pressure (NPT ensemble) for 1 ns. Upon equilibration, the production run was initiated and lasted for 100 ns with the trajectories saved every 10 ps for subsequent analysis. The stability of the system was tracked by monitoring the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone atoms, while the binding interactions were scrutinized using the LIGPLOT program and visualized with VMD (Visual Molecular Dynamics). This approach provides a comprehensive understanding of the dynamic behaviour of the telomerase-TQ complex, offering valuable insights into their interaction at the molecular level.

4. Discussion

We propose that utilizing SBE-β-CD to enhance the solubility and stability characteristics of TQ holds great potential as a treatment strategy for leukemia, a condition characterized by the abnormal proliferation of blood cells. SBE-β-CD is an attractive choice due to its low hemolytic activity compared to other cyclodextrin derivatives [

16]. This makes it a safe option for encapsulating TQ by SBE-β-CD as anti-leukemic therapy. Additionally, SBE-β-CD has been successfully investigated for controlled drug release and antibacterial efficacy using nanofibers and nanoparticles techniques [

17]. Previously, we investigated the formation of inclusion complexes between TQ and SBE-β-CD to improve the solubility and delivery of TQ, the results demonstrate that the inclusion complexes significantly enhance TQ's solubility and exhibit improved anticancer effects, suggesting the potential of SBE-β-CD as a drug delivery system for TQ, though further research is needed [

13]. Anticancer therapy focuses on targeting telomeres and telomerase, as they play crucial roles in cancer development. Telomerase, an enzyme responsible for regulating telomere length, is activated in nearly all cancer cells, allowing for uncontrolled cell growth. Consequently, telomerase has become a prominent target in cancer treatment research. Natural products that deactivate telomerase and destabilize telomeres present promising opportunities for the development of new targets in cancer therapy [

18]. According to one study, TQ promoted telomerase attrition by preventing the telomerase enzyme from functioning in human glioblastoma cancer cells [

19]. However, there is a limitation using TQ in drug development as TQ is poorly water soluble bioactive compound, which shows poor bioavailability [

20]. Therefore, in this study we encapsulated TQ with a type of cyclodextrin (CDs) known as SBE-ß-CDs to enhance the bioavailability of TQ [

21]. CDs are employed as drug carriers in the pharmaceutical industry to improve the solubility, stability, and bioavailability of bioactive substances. CDs are friendly to humans because of their high level of compatibility and FDA (food and drug administration) approved [

22].

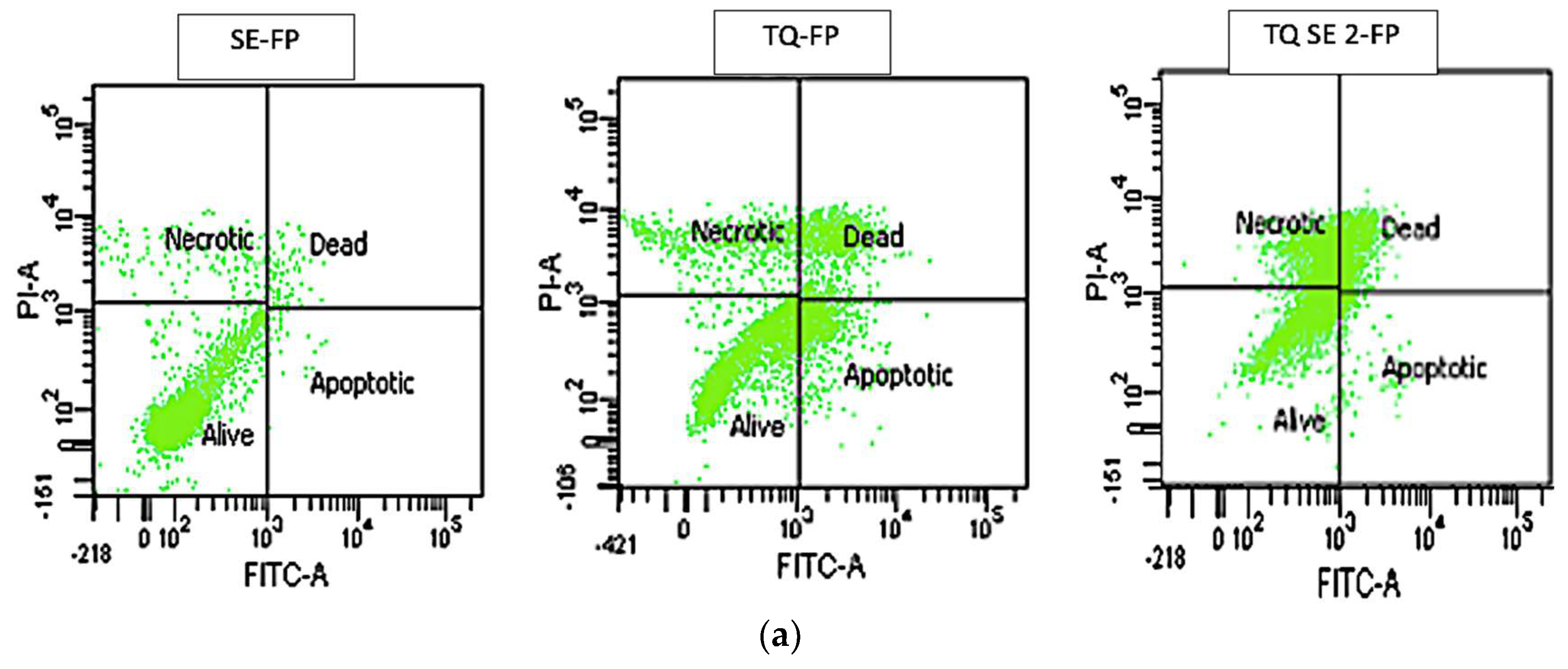

The aim of this study was to assess the effect of telomerase downregulation on suppressing the growth of leukemia cells by conducting an Annexin V-FITC test. This test was performed to investigate whether the reduced telomerase activity in leukemia cells resulted in apoptosis, a process in which phosphatidylserine (PS) translocates to the outer plasma membrane. By studying PS translocation, apoptosis could be examined as a potential mechanism.

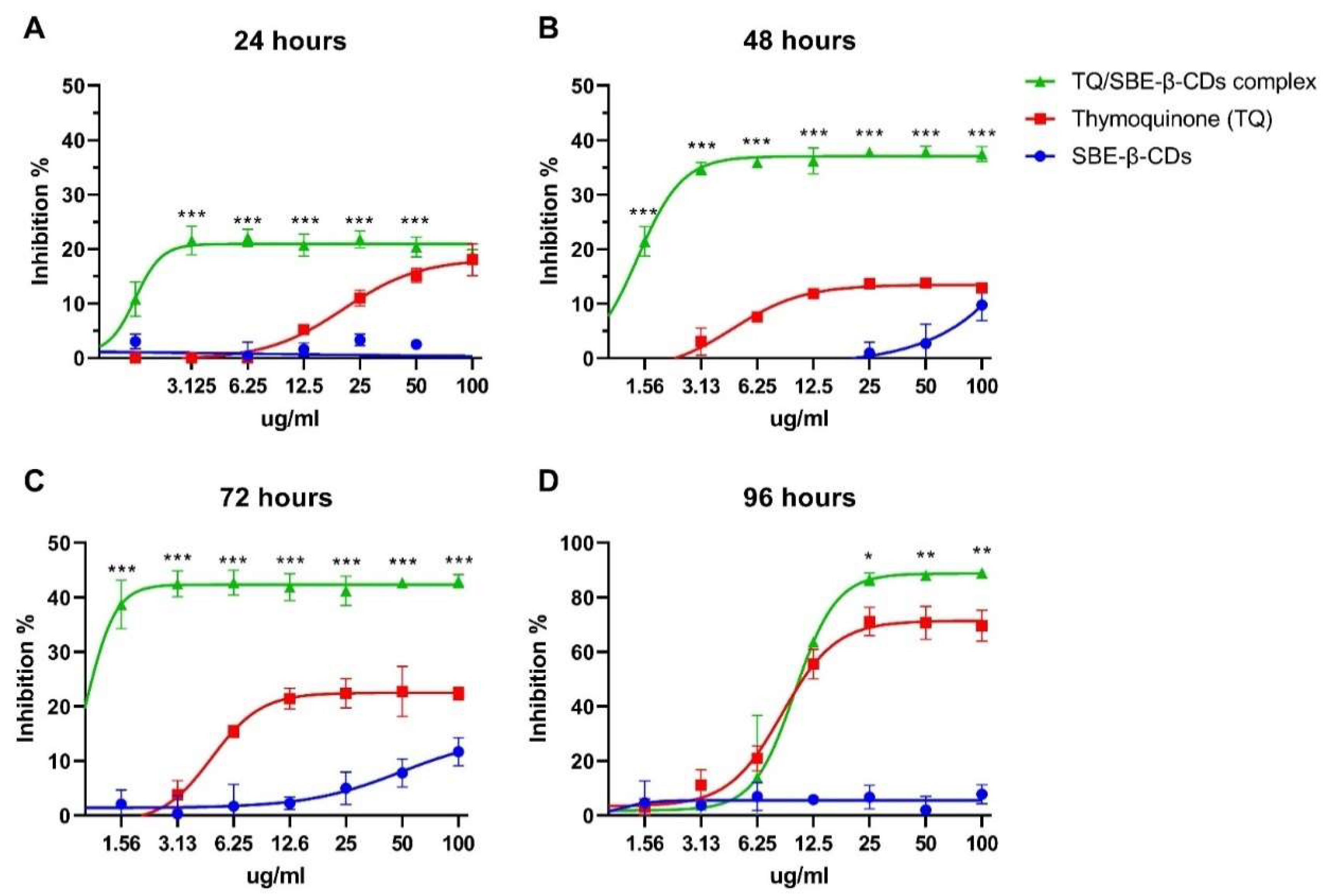

The cytotoxic effect of TQ and TQ/SBE-ß-CDs were tested on K-562 cells. Even though the cytotoxic results showed that the TQ and TQ/SBE-ß-CDs have a low toxic effect at incubation time less than 72h, the complex of TQ/SBE-ß-CDs showed better toxicity effects at lower concentrations than TQ alone, which could be the enhanced solubility properties of the complex. It was noticed as will that at times less than 72h, the cytotoxicity effects reach the plateau effect, even at low concentrations, this indicating that TQ and TQ/SBE-ß-CDs represent an inhibition effect and prevent the cells from division, or they interfered with the metabolism process, as CCK8 assay is affected by the enzymatic activity of the cells. However, plateau effect did not show at low concertation after 96h of the treatment, and at same time the cytotoxicity effects increased over 50%, indicating the TQ and TQ/SBE-ß-CDs cytotoxicity is time dependent, not concentration dependent. However, the shift in activity that happened after 96h could be results of the activity capacity of TQ and TQ/SBE-ß-CDs, as the number of cells increased and all the available substrate has already been interact with target enzymes, which justify the losing the toxic activity especially at low concentrations and increase in the activity at high concentrations. However, our results could be specific to the nature of K-562 cells and the structure and purity of TQ that has been isolated from black seed. A previous study explored the cytotoxicity effects of TQ on primary hepatocytes, showed a significate necrosis effect of TQ at concertation of 3.28 μg/ml, and concentrations higher than 3.28 μg/ml caused acute cytotoxicity within hours after treatment [

23]. The anticancer properties of TQ have been extensively investigated in various cancer types, and certain effects seem to be linked to the regulation of key genes involved in cancer biology. In the case of breast cancer, for example, TQ has been observed to increase the expression of p53, a vital tumor suppressor gene, in a time-dependent manner. This upregulation of p53 promotes apoptosis and inhibits the proliferation of cancer cells [

24]. In acute myeloid leukemia cells, TQ has shown to re-express tumor suppressor genes through de-methylation, inhibit the enzymatic activity of JAK/STAT signaling, and induce apoptosis [

8]. Furthermore, our previous study found that TQ/SBE-β-CD was more effective than TQ alone in inhibiting the growth of breast and colon cancer cell lines. The inhibitory effect of TQ/SBE-β-CD was the strongest on SkBr3 and HT29 cell lines, which are estrogen- and progesterone-independent and have distinct genetic and molecular features. TQ exerts its effects by modulating oncogenic pathways, suppressing inflammation and oxidative stress, preventing angiogenesis and metastasis, and inducing apoptosis. However, the limited clinical access to TQ is due to its low solubility and absorption. Using a nanoformulation approach such as SBE-β-CD has been shown to increase the effectiveness of TQ. Therefore, TQ/SBE-β-CD has the potential to be a promising strategy for cancer treatment [

13].

Annexin V is a calcium-dependent phospholipid-binding protein with a high affinity for PS, and it is frequently used in conjunction with PI (fluorescent dye) to identify apoptotic and necrotic cells [

25]. To further quantify the apoptotic leukaemia cells following the treatment with TQ and its encapsulated version with SBE-ß-CDs, cells were exposed to Annexin V/PI staining and subjected to flow cytometry. As a result, the highest percentage of live cells in the SBE-ß-CDs-treated cells (95.8%) with insignificant percentage of apoptotic, dead, and necrotic cells (

Figure 1) confirmed the safety of the encapsulation used in this study. The outcome revealed that the complex of TQ/SBE-ß-CDs enhanced the percentage of late apoptosis by 6% compared to TQ treatment. The percentage of necrotic cells was also enhanced in TQ/SBE-ß-CDs treated cells by 15.7%. Downregulation of telomerase may be a reason for the enhancement of apoptosis. This effect may be accompanied by DNA fragmentation, and induction of apoptotic genes [

26] which requires further investigation in the future. This finding would imply that TQ/SBE-ß-CDs can cause necrosis, a type of cell suicide that leads to more inflammation and may not be the preferred approach for cancer therapy. Necrosis is a type of cell death that occurs in addition to apoptosis. Here, we recommend additional research to improve the apoptotic effect of TQ/SBE-ß-CDs while minimizing necrosis induction.

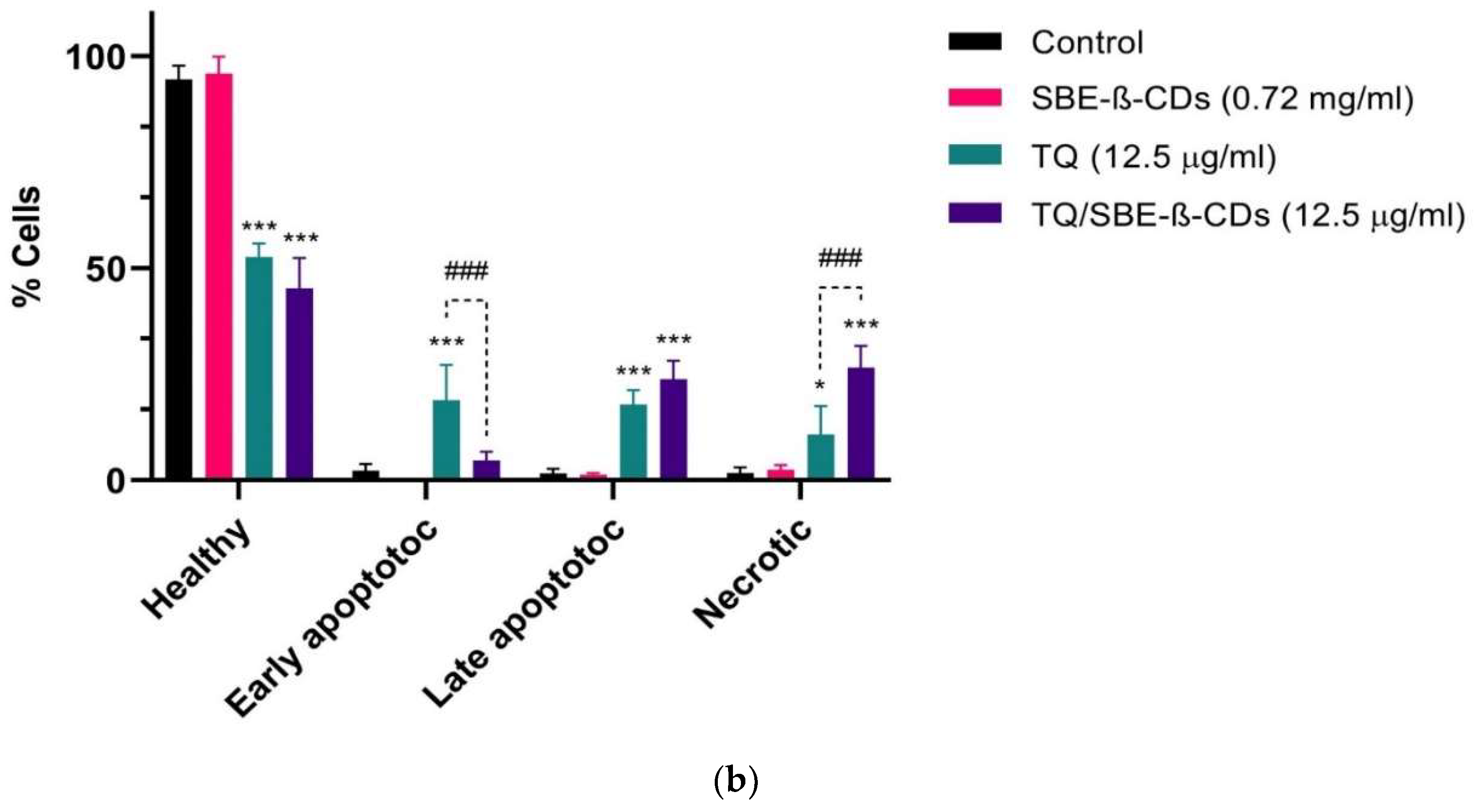

In the next step, in order to understand the activation of caspase cascade during SBE-ß-CDs, TQ and TQ/SBE-ß-CDs induced apoptosis in leukaemia cells, we investigated caspases 3/7, 8 and 9 activities after the cells were treated with different concentrations of each treatment for 96h. As shown in Figure the complex treatment activated caspase 9 and with activation of caspase 8 in a concentration dependent manner (≥12.5 µg/mL). This may suggest involvement of both extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways in cancer cell inhibition via TQ/SBE-ß-CDs treatment. Another study tested the effect of thymoquinone on human glioblastoma and normal cells and found that glioblastoma cells were more sensitive to thymoquinone-induced antiproliferative effects. Thymoquinone induced DNA damage, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis in the glioblastoma cells. Additionally, thymoquinone facilitated telomere attrition by inhibiting the activity of telomerase. The researchers also investigated the role of DNA-PKcs on thymoquinone mediated changes in telomere length and found that telomeres in glioblastoma cells with DNA-PKcs were more sensitive to thymoquinone mediated effects as compared to those cells deficient in DNA-PKcs [

19]. Thus, this study suggests that this complex treatment may induce apoptosis through different apoptosis pathways.

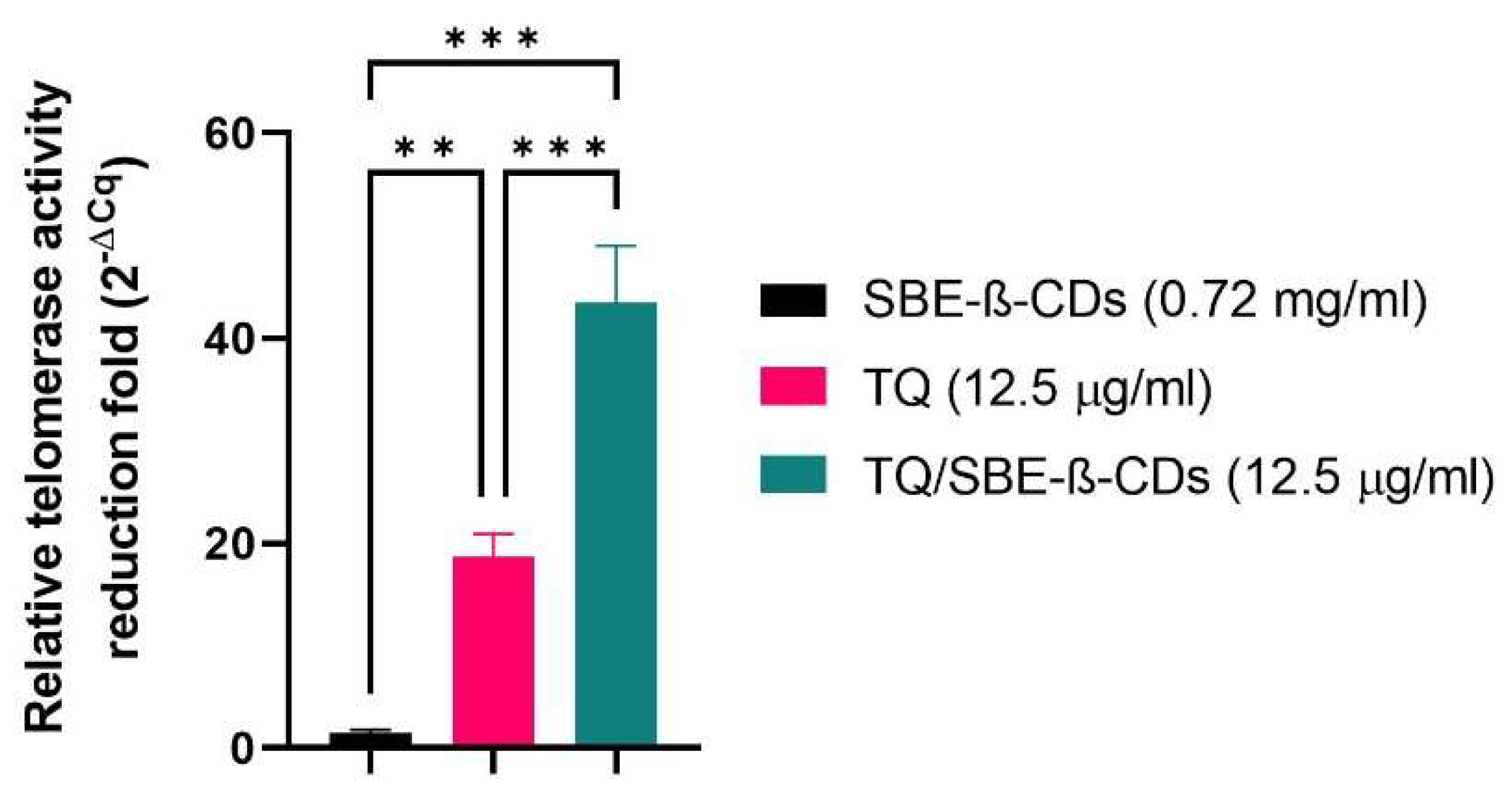

Telomerase is a significant enzyme involved in the preservation of chromosome ends, thereby playing a crucial role in cell division and aging. It becomes particularly relevant in the context of cancer research, as cancer cells often exhibit high telomerase activity, which contributes to their unchecked growth and division [

27]. Our findings revealed that the telomerase activity demonstrated a quantitative reduction in its folds among the cells treated with SBE-ß-CDs, TQ, and TQ/SBE-ß-CDs as compared to the negative control (untreated cells). On closer examination, it was found that the effects exhibited by SBE-ß-CDs were almost similar to those of the negative control, signifying that the impact of SBE-ß-CDs on telomerase activity is minimal. On the other hand, the complex of TQ/SBE-ß-CDs showed a significantly higher impact, effectively reducing the telomerase activity by more than double when compared to TQ alone. This suggests that the TQ/SBE-ß-CDs complex could potentially have stronger anti-telomerase properties than TQ in isolation, which believed related to the increase solubility of TQ when combined with SBE-ß-CDs. It's worth noting that previous studies have already established that exposure of thymoquinone to telomerase-positive human foreskin fibroblast cells (hTERT-BJ1) results in a significant reduction in telomerase activity and causes notable telomere attrition, which reinforces the anti-telomerase potential of TQ [

19].

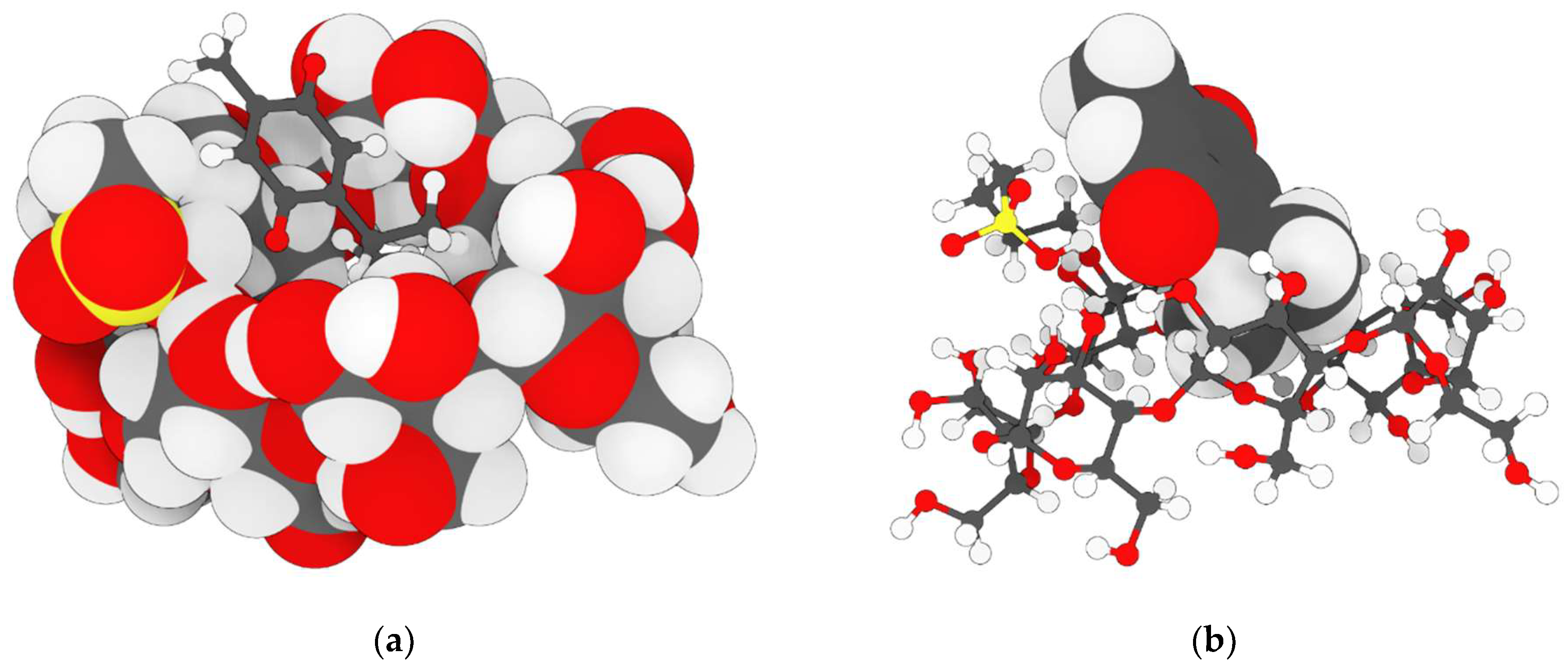

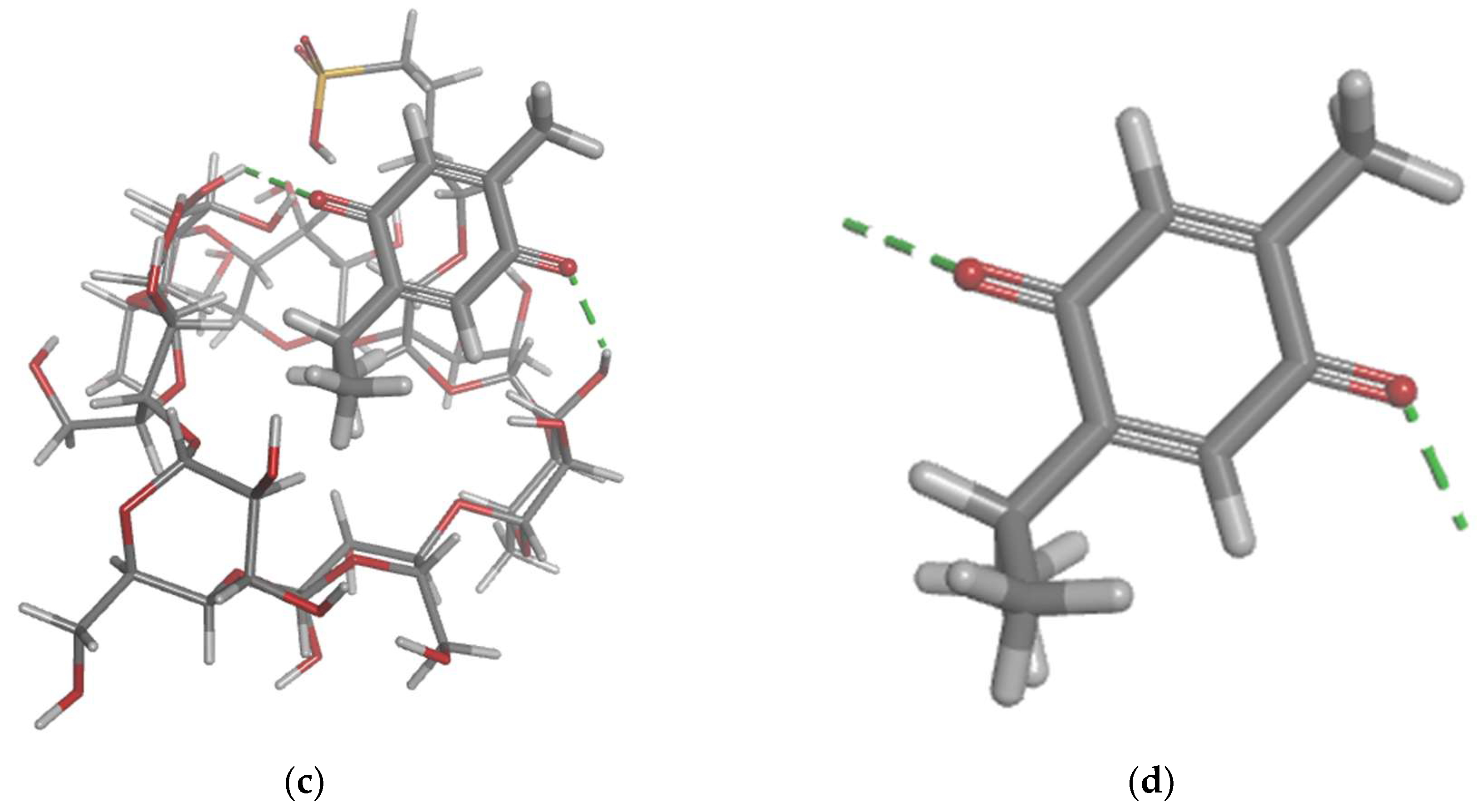

Molecular docking is a key tool in computational molecular biology. It is used to predict the interaction of a small molecule (ligand) with a protein (receptor) at the molecular level, which can provide important insights into the behaviour of biomolecules. The interaction between the SBE-ß-CDs and thymoquinone complex was explored using molecular docking approach that showed two hydrogen bonds that play a crucial role in the stability of the SBE-ß-CDs and thymoquinone complex, suggesting that these specific residues might be important for the potential for SBE-ß-CDs to bind with thymoquinone. Furthermore, the results of the study showed that TQ interacts with chain A of the telomerase. The top-scoring pose (mode 1) had a binding affinity of -6.65 kcal/mol, corresponding to a Ki of 13.45 μmol. This suggests a strong binding affinity between telomerase and thymoquinone. The binding affinity is a measure of the strength of the interaction between the ligand and the receptor. A lower value (more negative) indicates a stronger interaction. The second and third highest scoring poses had low lower bound of the RMSD (1.97 and 1.55 Å, respectively) and upper bound of the RMSD (3.08 and 3.81 Å, respectively) from the ligand's best mode (mode 1), indicating a relative stability of the interaction. The RMSD (root-mean-square deviation) is a measure of the average distance between the atoms of the ligand in the different poses. A lower RMSD indicates a higher similarity between the poses, suggesting that the interaction is relatively stable. Thymoquinone in our study forms H-Bond with two amino acid Chain A, THR 143 and TYR 116, and hydrophobic interaction with several amino acids of the chain a including ALA 81, LEU 95, ALA 81, TYR 84, TYR 118, TYR 123, and TRP 147, which is from a different binding site from the one that targeted by 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives containing 1,4-benzodioxan moiety as potential telomerase inhibitors, by binding to the telomerase by forming H-bond with two amino acids LYS 372, LYS 406 [

28]. 1-isoquinoline-2-styryl-5-nitroimidazole derivatives was proposed as telomerase inhibitor by forming H-bonds with two amino acids LYS 189 and ALA 255 [

29].

Author Contributions

conceptualization and experimental design, E.E.M.E., A.A.A. and M.A.A.; methodology, investigation, and analysis, E.E.M.E., S.A.A., W.A., S.K. and. V.S.L.; software, E.E.M.E., S.A.A., V.S.L. and resources, E.E.M.E., A.A.A. and M.A.A.; data curation, E.E.M.E., S.A.A., S.K. and F.O.S.; manuscript draft preparation, E.E.M.E., S.A.A. and project administration, E.E.M.E. and M.A.A.; funding acquisition, E.E.M.E. All authors have reviewed the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Cytotoxicity results of leukaemia cells (K-562) after 24, 48, 72, and 96 hrs of the treatment. The Control group was untreated cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 indicate significant difference between TQ and TQ/SBE-ß-CDs for the same concentration level.

Figure 1.

Cytotoxicity results of leukaemia cells (K-562) after 24, 48, 72, and 96 hrs of the treatment. The Control group was untreated cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001 indicate significant difference between TQ and TQ/SBE-ß-CDs for the same concentration level.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry graphs and results quantification in leukaemia cells after 96h of treatment. The Control group remained untreated. Data are presented as mean ± SD, *p< 0.05, ***p< 0.001 indicate significant difference compared to control, ###p<0.001 indicates significant difference between TQ and TQ/SBE-ß-CDs treated groups.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry graphs and results quantification in leukaemia cells after 96h of treatment. The Control group remained untreated. Data are presented as mean ± SD, *p< 0.05, ***p< 0.001 indicate significant difference compared to control, ###p<0.001 indicates significant difference between TQ and TQ/SBE-ß-CDs treated groups.

Figure 3.

Caspase 3/7, 8 and 9 activities induced by TQ, SBE-ß-CDs, and TQ/SBE-ß-CDs therapy in leukaemia cells. Estimation was measured using luminescence analysis at 96h treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ***p<0.01 indicates a significant difference compared to the control cells (untreated).

Figure 3.

Caspase 3/7, 8 and 9 activities induced by TQ, SBE-ß-CDs, and TQ/SBE-ß-CDs therapy in leukaemia cells. Estimation was measured using luminescence analysis at 96h treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ***p<0.01 indicates a significant difference compared to the control cells (untreated).

Figure 4.

Quantitative PCR Results of Telomerase Activity. Numbers represent the average fold reduction compared to the untreated cells.

Figure 4.

Quantitative PCR Results of Telomerase Activity. Numbers represent the average fold reduction compared to the untreated cells.

Figure 5.

Molecular docking modelling of thymoquinone with SBE-ß-CDs with.

Figure 5.

Molecular docking modelling of thymoquinone with SBE-ß-CDs with.

Figure 6.

Molecular docking modelling of thymoquinone with telomerase.

Figure 6.

Molecular docking modelling of thymoquinone with telomerase.

Figure 7.

Molecular dynamic simulation results. A, Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) values for α-carbon atoms (blue curves) of Telomerase and TQ (red curves), B, H-bond number formed over the simulation time. C, the root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) results. D, radius of gyration, plotted with respect to 100 ns MD simulation time.

Figure 7.

Molecular dynamic simulation results. A, Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) values for α-carbon atoms (blue curves) of Telomerase and TQ (red curves), B, H-bond number formed over the simulation time. C, the root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) results. D, radius of gyration, plotted with respect to 100 ns MD simulation time.

Table 1.

the binding interactions atoms and type between SBE-ß-CDs and thymoquinone.

Table 1.

the binding interactions atoms and type between SBE-ß-CDs and thymoquinone.

Category

|

Types

|

Distance

|

From

|

To

|

| Hydrogen Bond |

Conventional Hydrogen Bond |

2.86 |

SBE-ß-CDs: H35 (H-Donor) |

TQ: O (H-Acceptor) |

| Hydrogen Bond |

Conventional Hydrogen Bond |

2.21 |

SBE-ß-CDs: H77 (H-Donor) |

TQ: O (H-Acceptor) |

Table 2.

The binding interactions residue and type between telomerase and thymoquinone.

Table 2.

The binding interactions residue and type between telomerase and thymoquinone.

| Category |

Types |

Distance |

`From |

To |

| Hydrogen Bond |

Carbon Hydrogen Bond |

2.75 |

TQ: H (H-Donor) |

Chain A: THR143:OG1 (H-Acceptor) |

| Hydrogen Bond |

Pi-Donor Hydrogen Bond |

2.95 |

TQ: H (H-Donor) |

Chain A:TYR116 (Pi-Orbitals) |

| Hydrophobic |

Alkyl |

3.72 |

TQ: C10 (Alkyl) |

Chain A: ALA81 (Alkyl) |

| Hydrophobic |

Alkyl |

4.67 |

TQ: C10 (Alkyl) |

Chain A: LEU95 (Alkyl) |

| Hydrophobic |

Alkyl |

3.38 |

TQ: C9 (Alkyl) |

Chain A: ALA81 (Alkyl) |

| Hydrophobic |

Pi-Alkyl |

4.79 |

Chain A: TYR84 (Pi-Orbitals) |

TQ: C9 (Alkyl) |

| Hydrophobic |

Pi-Alkyl |

4.38 |

Chain A: TYR118 (Pi-Orbitals) |

TQ: C10 (Alkyl) |

| Hydrophobic |

Pi-Alkyl |

4.02 |

Chain A: TYR123 (Pi-Orbitals) |

TQ: C10 (Alkyl) |

| Hydrophobic |

Pi-Alkyl |

3.98 |

Chain A: TYR123 (Pi-Orbitals) |

TQ: C9 (Alkyl) |

| Hydrophobic |

Pi-Alkyl |

4.82 |

Chain A: TRP147 (Pi-Orbitals) |

TQ: C7 (Alkyl) |

| Hydrophobic |

Pi-Alkyl |

4.97 |

Chain A: TRP147 (Pi-Orbitals) |

TQ: C7 (Alkyl) |