Submitted:

14 June 2023

Posted:

14 June 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

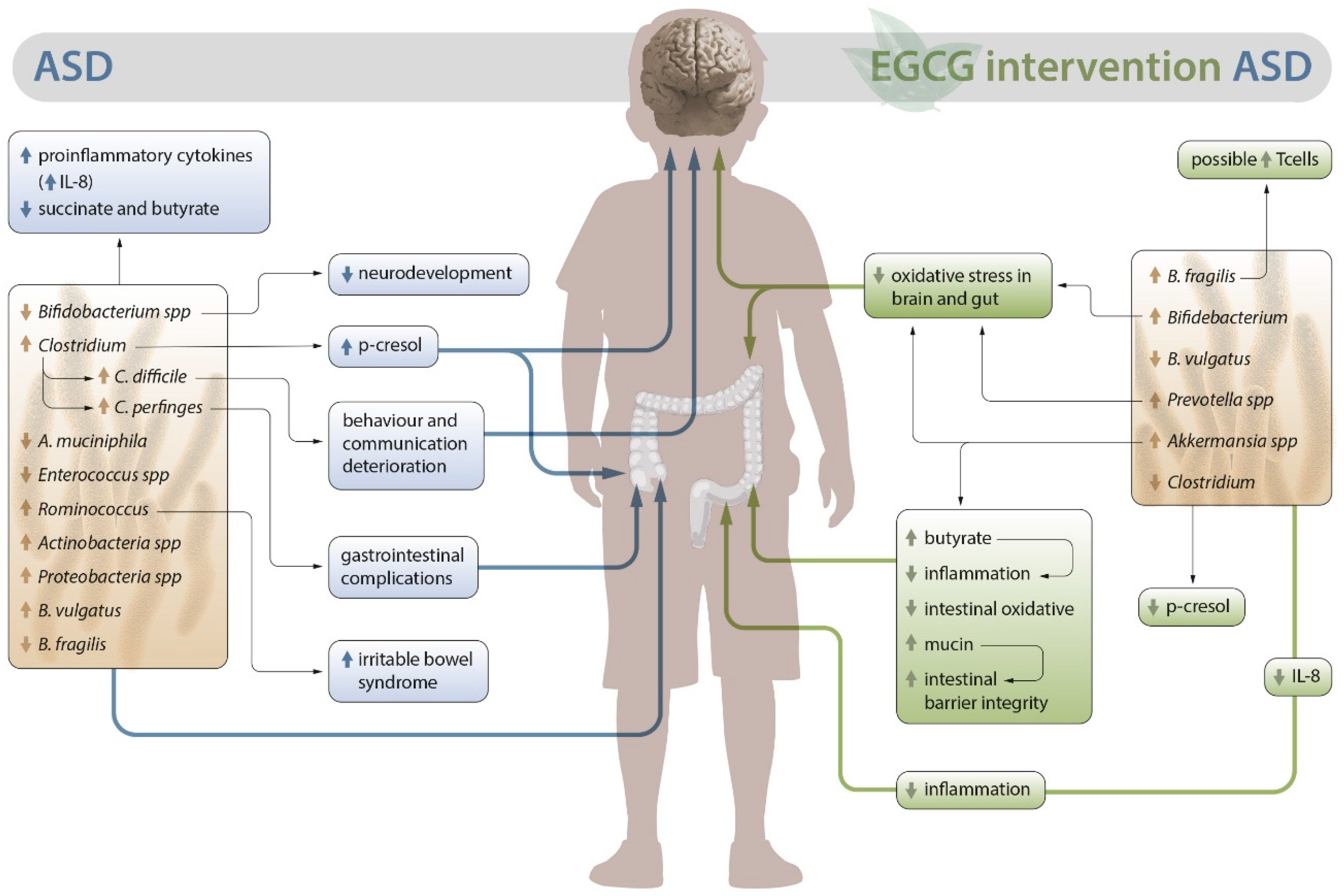

2. Alterations in the intestinal microbiota in ASD

3. EGCG as an alternative for ASD

3.1. Possible role of EGCG in the intestinal microbiota of patients with ASD

3.2. Outlook on the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity of EGCG in autism. Neuroprotective role

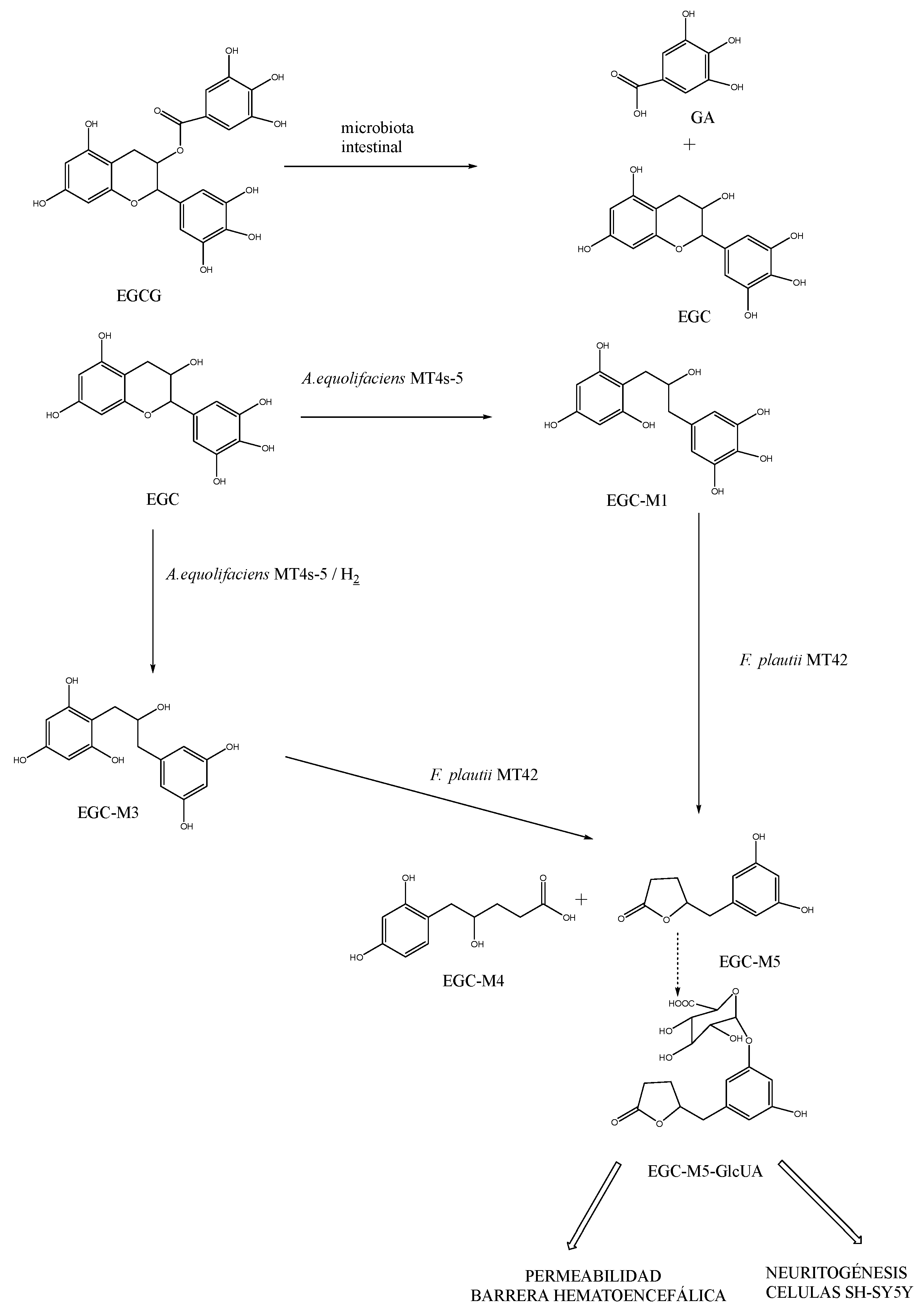

3.3. Role of EGCG in the metabolic activity associated with dysbiosis in ASD

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taylor, M. J.; Rosenqvist, M. A.; Larsson, H.; Gillberg, C.; D’Onofrio, B. M.; Lichtenstein, P.; Lundström, S. Etiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders and Autistic Traits Over Time. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77 (9), 936–943. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAPSYCHIATRY.2020.0680. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. 2013.

- Hughes, H. K.; Rose, D.; Ashwood, P. The Gut Microbiota and Dysbiosis in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Reports 2018 1811 2018, 18 (11), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11910-018-0887-6. [CrossRef]

- Baio, J.; Wiggins, L.; Christensen, D. L.; Maenner, M. J.; Daniels, J.; Warren, Z.; Kurzius-Spencer, M.; Zahorodny, W.; Rosenberg, C. R.; White, T.; Durkin, M. S.; Imm, P.; Nikolaou, L.; Yeargin-Allsopp, M.; Lee, L. C.; Harrington, R.; Lopez, M.; Fitzgerald, R. T.; Hewitt, A.; Pettygrove, S.; Constantino, J. N.; Vehorn, A.; Shenouda, J.; Hall-Lande, J.; Naarden Braun, K. Van; Dowling, N. F. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder among Children Aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2018, 67 (6), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.15585/MMWR.SS6706A1. [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, R.; Gibson, G. R.; Vulevic, J.; Giallourou, N.; Castro-Mejía, J. L.; Hansen, L. H.; Leigh Gibson, E.; Nielsen, D. S.; Costabile, A. A Prebiotic Intervention Study in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs). Microbiome 2018, 6 (1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/S40168-018-0523-3/TABLES/2. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Autism. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/autism-spectrum-disorders (accessed 2023-02-26).

- Li, Q.; Zhou, J. M. The Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis and Its Potential Therapeutic Role in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuroscience 2016, 324, 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUROSCIENCE.2016.03.013. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Fu, X.; Liao, X.; Li, Y. Effects of Gut Microbial-Based Treatments on Gut Microbiota, Behavioral Symptoms, and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2020.113471. [CrossRef]

- de Theije, C. G. M.; Wopereis, H.; Ramadan, M.; van Eijndthoven, T.; Lambert, J.; Knol, J.; Garssen, J.; Kraneveld, A. D.; Oozeer, R. Altered Gut Microbiota and Activity in a Murine Model of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2014, 37, 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBI.2013.12.005. [CrossRef]

- Strati, F.; Cavalieri, D.; Albanese, D.; De Felice, C.; Donati, C.; Hayek, J.; Jousson, O.; Leoncini, S.; Renzi, D.; Calabrò, A.; De Filippo, C. New Evidences on the Altered Gut Microbiota in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Microbiome 2017, 5 (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/S40168-017-0242-1/FIGURES/5. [CrossRef]

- Huttenhower, C.; Gevers, D.; Knight, R.; Abubucker, S.; Badger, J. H.; Chinwalla, A. T.; Creasy, H. H.; Earl, A. M.; Fitzgerald, M. G.; Fulton, R. S.; Giglio, M. G.; Hallsworth-Pepin, K.; Lobos, E. A.; Madupu, R.; Magrini, V.; Martin, J. C.; Mitreva, M.; Muzny, D. M.; Sodergren, E. J.; Versalovic, J.; Wollam, A. M.; Worley, K. C.; Wortman, J. R.; Young, S. K.; Zeng, Q.; Aagaard, K. M.; Abolude, O. O.; Allen-Vercoe, E.; Alm, E. J.; Alvarado, L.; Andersen, G. L.; Anderson, S.; Appelbaum, E.; Arachchi, H. M.; Armitage, G.; Arze, C. A.; Ayvaz, T.; Baker, C. C.; Begg, L.; Belachew, T.; Bhonagiri, V.; Bihan, M.; Blaser, M. J.; Bloom, T.; Bonazzi, V.; Paul Brooks, J.; Buck, G. A.; Buhay, C. J.; Busam, D. A.; Campbell, J. L.; Canon, S. R.; Cantarel, B. L.; Chain, P. S. G.; Chen, I. M. A.; Chen, L.; Chhibba, S.; Chu, K.; Ciulla, D. M.; Clemente, J. C.; Clifton, S. W.; Conlan, S.; Crabtree, J.; Cutting, M. A.; Davidovics, N. J.; Davis, C. C.; Desantis, T. Z.; Deal, C.; Delehaunty, K. D.; Dewhirst, F. E.; Deych, E.; Ding, Y.; Dooling, D. J.; Dugan, S. P.; Michael Dunne, W.; Scott Durkin, A.; Edgar, R. C.; Erlich, R. L.; Farmer, C. N.; Farrell, R. M.; Faust, K.; Feldgarden, M.; Felix, V. M.; Fisher, S.; Fodor, A. A.; Forney, L. J.; Foster, L.; Di Francesco, V.; Friedman, J.; Friedrich, D. C.; Fronick, C. C.; Fulton, L. L.; Gao, H.; Garcia, N.; Giannoukos, G.; Giblin, C.; Giovanni, M. Y.; Goldberg, J. M.; Goll, J.; Gonzalez, A.; Griggs, A.; Gujja, S.; Kinder Haake, S.; Haas, B. J.; Hamilton, H. A.; Harris, E. L.; Hepburn, T. A.; Herter, B.; Hoffmann, D. E.; Holder, M. E.; Howarth, C.; Huang, K. H.; Huse, S. M.; Izard, J.; Jansson, J. K.; Jiang, H.; Jordan, C.; Joshi, V.; Katancik, J. A.; Keitel, W. A.; Kelley, S. T.; Kells, C.; King, N. B.; Knights, D.; Kong, H. H.; Koren, O.; Koren, S.; Kota, K. C.; Kovar, C. L.; Kyrpides, N. C.; La Rosa, P. S.; Lee, S. L.; Lemon, K. P.; Lennon, N.; Lewis, C. M.; Lewis, L.; Ley, R. E.; Li, K.; Liolios, K.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Lo, C. C.; Lozupone, C. A.; Dwayne Lunsford, R.; Madden, T.; Mahurkar, A. A.; Mannon, P. J.; Mardis, E. R.; Markowitz, V. M.; Mavromatis, K.; McCorrison, J. M.; McDonald, D.; McEwen, J.; McGuire, A. L.; McInnes, P.; Mehta, T.; Mihindukulasuriya, K. A.; Miller, J. R.; Minx, P. J.; Newsham, I.; Nusbaum, C.; Oglaughlin, M.; Orvis, J.; Pagani, I.; Palaniappan, K.; Patel, S. M.; Pearson, M.; Peterson, J.; Podar, M.; Pohl, C.; Pollard, K. S.; Pop, M.; Priest, M. E.; Proctor, L. M.; Qin, X.; Raes, J.; Ravel, J.; Reid, J. G.; Rho, M.; Rhodes, R.; Riehle, K. P.; Rivera, M. C.; Rodriguez-Mueller, B.; Rogers, Y. H.; Ross, M. C.; Russ, C.; Sanka, R. K.; Sankar, P.; Fah Sathirapongsasuti, J.; Schloss, J. A.; Schloss, P. D.; Schmidt, T. M.; Scholz, M.; Schriml, L.; Schubert, A. M.; Segata, N.; Segre, J. A.; Shannon, W. D.; Sharp, R. R.; Sharpton, T. J.; Shenoy, N.; Sheth, N. U.; Simone, G. A.; Singh, I.; Smillie, C. S.; Sobel, J. D.; Sommer, D. D.; Spicer, P.; Sutton, G. G.; Sykes, S. M.; Tabbaa, D. G.; Thiagarajan, M.; Tomlinson, C. M.; Torralba, M.; Treangen, T. J.; Truty, R. M.; Vishnivetskaya, T. A.; Walker, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Ward, D. V.; Warren, W.; Watson, M. A.; Wellington, C.; Wetterstrand, K. A.; White, J. R.; Wilczek-Boney, K.; Wu, Y.; Wylie, K. M.; Wylie, T.; Yandava, C.; Ye, L.; Ye, Y.; Yooseph, S.; Youmans, B. P.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zoloth, L.; Zucker, J. D.; Birren, B. W.; Gibbs, R. A.; Highlander, S. K.; Methé, B. A.; Nelson, K. E.; Petrosino, J. F.; Weinstock, G. M.; Wilson, R. K.; White, O. Structure, Function and Diversity of the Healthy Human Microbiome. Nature 2012, 486 (7402), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1038/NATURE11234. [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G. A. D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M. C. What Is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7 (1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/MICROORGANISMS7010014. [CrossRef]

- Iovene, M. R.; Bombace, F.; Maresca, R.; Sapone, A.; Iardino, P.; Picardi, A.; Marotta, R.; Schiraldi, C.; Siniscalco, D.; Serra, N.; de Magistris, L.; Bravaccio, C. Intestinal Dysbiosis and Yeast Isolation in Stool of Subjects with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Mycopathologia 2017, 182 (3–4), 349–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11046-016-0068-6/METRICS. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Kapoor, A.; Verma, A.; Ambatipudi, K. Functional Significance of Different Milk Constituents in Modulating the Gut Microbiome and Infant Health. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70 (13), 3929–3947. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.JAFC.2C00335/ASSET/IMAGES/MEDIUM/JF2C00335_0006.GIF. [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Yi, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Mou, W. W. Imbalance in the Gut Microbiota of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 496. https://doi.org/10.3389/FCIMB.2021.572752/BIBTEX. [CrossRef]

- Heijtz, R. D.; Wang, S.; Anuar, F.; Qian, Y.; Björkholm, B.; Samuelsson, A.; Hibberd, M. L.; Forssberg, H.; Pettersson, S. Normal Gut Microbiota Modulates Brain Development and Behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108 (7), 3047–3052. https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.1010529108. [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L. V.; Littman, D. R.; Macpherson, A. J. Interactions between the Microbiota and the Immune System. Science (80-. ). 2012, 336 (6086), 1268–1273. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.1223490. [CrossRef]

- Frye, R. E.; Melnyk, S.; Macfabe, D. F. Unique Acyl-Carnitine Profiles Are Potential Biomarkers for Acquired Mitochondrial Disease in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2013, 3. https://doi.org/10.1038/TP.2012.143. [CrossRef]

- Slattery, J.; Macfabe, D. F.; Frye, R. E. The Significance of the Enteric Microbiome on the Development of Childhood Disease: A Review of Prebiotic and Probiotic Therapies in Disorders of Childhood. Clin. Med. Insights Pediatr. 2016, 10, CMPed.S38338. https://doi.org/10.4137/CMPED.S38338. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Li, B.; Duan, G.; Zhu, C. The Role of Probiotics in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Study Protocol for a Randomised Controlled Trial. PLoS One 2022, 17 (2). https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0263109. [CrossRef]

- Grenham, S.; Clarke, G.; Cryan, J. F.; Dinan, T. G. Brain-Gut-Microbe Communication in Health and Disease. Front. Physiol. 2011, 2 DEC. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPHYS.2011.00094. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Li, G.; Huang, P.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, B. The Gut Microbiota and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 58 (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-161141. [CrossRef]

- Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M. A.; Severi, C. The Gut-Brain Axis: Interactions between Enteric Microbiota, Central and Enteric Nervous Systems. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28 (2), 203–209.

- Barrett, E.; Ross, R. P.; O’Toole, P. W.; Fitzgerald, G. F.; Stanton, C. γ-Aminobutyric Acid Production by Culturable Bacteria from the Human Intestine. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113 (2), 411–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1365-2672.2012.05344.X. [CrossRef]

- Serra, D.; Almeida, L. M.; Dinis, T. C. P. Polyphenols in the Management of Brain Disorders: Modulation of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 91, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/BS.AFNR.2019.08.001. [CrossRef]

- Powell, N.; Walker, M. M.; Talley, N. J. The Mucosal Immune System: Master Regulator of Bidirectional Gut–Brain Communications. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017 143 2017, 14 (3), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2016.191. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Weng, P. The Interaction between Tea Polyphenols and Host Intestinal Microorganisms: An Effective Way to Prevent Psychiatric Disorders. Food Funct. 2021, 12 (3), 952–962. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0FO02791J. [CrossRef]

- Argou-Cardozo, I.; Zeidán-Chuliá, F. Clostridium Bacteria and Autism Spectrum Conditions: A Systematic Review and Hypothetical Contribution of Environmental Glyphosate Levels. Med. Sci. 2018, 6 (2), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/MEDSCI6020029. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Xu, X.; Li, J.; Li, F. Association between Gut Microbiota and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10 (JULY). https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYT.2019.00473. [CrossRef]

- Zou, R.; Xu, F.; Wang, Y.; Duan, M.; Guo, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, H. Changes in the Gut Microbiota of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Res. 2020, 13 (9), 1614–1625. https://doi.org/10.1002/AUR.2358. [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.; Piccolo, M.; Vannini, L.; Siragusa, S.; De Giacomo, A.; Serrazzanetti, D. I.; Cristofori, F.; Guerzoni, M. E.; Gobbetti, M.; Francavilla, R. Fecal Microbiota and Metabolome of Children with Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified. PLoS One 2013, 8 (10). https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0076993. [CrossRef]

- Andreo-Martínez, P.; García-Martínez, N.; Sánchez-Samper, E. P.; Martínez-González, A. E. An Approach to Gut Microbiota Profile in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2020, 12 (2), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-2229.12810. [CrossRef]

- Tomova, A.; Husarova, V.; Lakatosova, S.; Bakos, J.; Vlkova, B.; Babinska, K.; Ostatnikova, D. Gastrointestinal Microbiota in Children with Autism in Slovakia. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 138, 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2014.10.033. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Li, L.; Wu, X.; Hou, F.; Chen, Y.; Shi, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, K.; Jiang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Xiao, P.; Zhang, J.; Gong, J.; Song, R. Alteration of the Fecal Microbiota in Chinese Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Res. 2022, 15 (6), 996–1007. https://doi.org/10.1002/AUR.2718. [CrossRef]

- Ho, L. K. H.; Tong, V. J. W.; Syn, N.; Nagarajan, N.; Tham, E. H.; Tay, S. K.; Shorey, S.; Tambyah, P. A.; Law, E. C. N. Gut Microbiota Changes in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Gut Pathog. 2020, 12 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13099-020-0346-1/TABLES/5. [CrossRef]

- De Filippo, C.; Cavalieri, D.; Di Paola, M.; Ramazzotti, M.; Poullet, J. B.; Massart, S.; Collini, S.; Pieraccini, G.; Lionetti, P. Impact of Diet in Shaping Gut Microbiota Revealed by a Comparative Study in Children from Europe and Rural Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107 (33), 14691–14696. https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.1005963107. [CrossRef]

- Nogay, N. H.; Nahikian-Nelms, M. Can We Reduce Autism-Related Gastrointestinal and Behavior Problems by Gut Microbiota Based Dietary Modulation? A Review. Nutr. Neurosci. 2021, 24 (5), 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2019.1630894. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.; Rho, J. M.; Masino, S. A. Metabolic Dysfunction Underlying Autism Spectrum Disorder and Potential Treatment Approaches. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 34. https://doi.org/10.3389/FNMOL.2017.00034/BIBTEX. [CrossRef]

- Serra, D.; Almeida, L. M.; Dinis, T. C. P. Polyphenols as Food Bioactive Compounds in the Context of Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Critical Mini-Review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 102, 290–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.05.010. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Burillo, S.; Navajas-Porras, B.; López-Maldonado, A.; Hinojosa-Nogueira, D.; Pastoriza, S.; Rufián-Henares, J. Á. Green Tea and Its Relation to Human Gut Microbiome. Molecules 2021, 26 (13). https://doi.org/10.3390/MOLECULES26133907. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Bruins, M. E.; Ni, L.; Vincken, J. P. Green and Black Tea Phenolics: Bioavailability, Transformation by Colonic Microbiota, and Modulation of Colonic Microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66 (32), 8469–8477. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02233. [CrossRef]

- Francisco A .; Tomás-Barberán; González-Sarrías, A.; García-Villalba, R. Dietary Polyphenols: Metabolism and Health Effects; Wiley-Blackwell: Murcia, 2020.

- Peterson, J.; Dwyer, J.; Bhagwat, S.; Haytowitz, D.; Holden, J.; Eldridge, A. L.; Beecher, G.; Aladesanmi, J. Major Flavonoids in Dry Tea. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2005, 18 (6), 487–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFCA.2004.05.006. [CrossRef]

- Ankolekar, C.; Johnson, D.; Pinto, M. D. S.; Johnson, K.; Labbe, R.; Shetty, K. Inhibitory Potential of Tea Polyphenolics and Influence of Extraction Time against Helicobacter Pylori and Lack of Inhibition of Beneficial Lactic Acid Bacteria. J. Med. Food 2011, 14 (11), 1321–1329. https://doi.org/10.1089/JMF.2010.0237. [CrossRef]

- Shin, J. S.; Chung, H. S. Antibacterial Activities of Phenolic Components from Camellia Sinensis L. on Pathogenic Microorganisms. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2007, 12 (3), 135–140. https://doi.org/10.3746/JFN.2007.12.3.135. [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, M.; Shigemune, N.; Tsugukuni, T.; Jun, H.; Matsushita, T.; Mekada, Y.; Kurahachi, M.; Miyamoto, T. Mechanism of the Combined Anti-Bacterial Effect of Green Tea Extract and NaCl against Staphylococcus Aureus and Escherichia Coli O157:H7. Food Control 2012, 25 (1), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODCONT.2011.10.021. [CrossRef]

- Kohda, C.; Yanagawa, Y.; Shimamura, T. Epigallocatechin Gallate Inhibits Intracellular Survival of Listeria Monocytogenes in Macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 365 (2), 310–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBRC.2007.10.190. [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Gong, J.; Tsao, R.; Kalab, M.; Yang, R.; Yin, Y. Bioassay-Guided Purification and Identification of Antimicrobial Components in Chinese Green Tea Extract. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1125 (2), 204–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHROMA.2006.05.061. [CrossRef]

- Bancirova, M. Comparison of the Antioxidant Capacity and the Antimicrobial Activity of Black and Green Tea. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43 (5), 1379–1382. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODRES.2010.04.020. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lu, H.; Zhao, Q.; He, Y.; Niu, J.; Debnath, A. K.; Wu, S.; Jiang, S. Theaflavin Derivatives in Black Tea and Catechin Derivatives in Green Tea Inhibit HIV-1 Entry by Targeting Gp41. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1723 (1–3), 270–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBAGEN.2005.02.012. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. L.; Tsai, H. L.; Peng, C. W. EGCG Debilitates the Persistence of EBV Latency by Reducing the DNA Binding Potency of Nuclear Antigen 1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 417 (3), 1093–1099. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBRC.2011.12.104. [CrossRef]

- Duda-Chodak, A.; Tarko, T.; Satora, P.; Sroka, P. Interaction of Dietary Compounds, Especially Polyphenols, with the Intestinal Microbiota: A Review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54 (3), 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00394-015-0852-Y. [CrossRef]

- Nagle, D. G.; Ferreira, D.; Zhou, Y. D. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG): Chemical and Biomedical Perspectives. Phytochemistry 2006, 67 (17), 1849–1855. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYTOCHEM.2006.06.020. [CrossRef]

- Scholey, A.; Downey, L. A.; Ciorciari, J.; Pipingas, A.; Nolidin, K.; Finn, M.; Wines, M.; Catchlove, S.; Terrens, A.; Barlow, E.; Gordon, L.; Stough, C. Acute Neurocognitive Effects of Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG). Appetite 2012, 58 (2), 767–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APPET.2011.11.016. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. C.; Jenner, A. M.; Low, C. S.; Lee, Y. K. Effect of Tea Phenolics and Their Aromatic Fecal Bacterial Metabolites on Intestinal Microbiota. Res. Microbiol. 2006, 157 (9), 876–884. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESMIC.2006.07.004. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; De Bruijn, W. J. C.; Bruins, M. E.; Vincken, J. P. Reciprocal Interactions between Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) and Human Gut Microbiota in Vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68 (36), 9804–9815. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.JAFC.0C03587/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/JF0C03587_0011.JPEG. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xie, M.; Xue, J.; Xiang, L.; Li, Y.; Xiao, J.; Xiao, G.; Wang, H. L. EGCG Ameliorates Neuronal and Behavioral Defects by Remodeling Gut Microbiota and TotM Expression in Drosophila Models of Parkinson’s Disease. FASEB J. 2020, 34 (4), 5931–5950. https://doi.org/10.1096/FJ.201903125RR. [CrossRef]

- Ushiroda, C.; Naito, Y.; Takagi, T.; Uchiyama, K.; Mizushima, K.; Higashimura, Y.; Yasukawa, Z.; Okubo, T.; Inoue, R.; Honda, A.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Itoh, Y. Green Tea Polyphenol (Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate) Improves Gut Dysbiosis and Serum Bile Acids Dysregulation in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2019, 65 (1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.3164/JCBN.18-116. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Cheng, W.; Wang, D.; Zeng, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Sun, L.; Ai, J. Amelioration of Cognitive Impairment Using Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate in Ovariectomized Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet Involves Remodeling with Prevotella and Bifidobacteriales. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPHAR.2022.1079313. [CrossRef]

- Mastromarino, P.; Capobianco, D.; Campagna, G.; Laforgia, N.; Drimaco, P.; Dileone, A.; Baldassarre, M. E. Correlation between Lactoferrin and Beneficial Microbiota in Breast Milk and Infant’s Feces. Biometals 2014, 27 (5), 1077–1086. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10534-014-9762-3. [CrossRef]

- Savignac, H. M.; Kiely, B.; Dinan, T. G.; Cryan, J. F. Bifidobacteria Exert Strain-Specific Effects on Stress-Related Behavior and Physiology in BALB/c Mice. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014, 26 (11), 1615–1627. https://doi.org/10.1111/NMO.12427. [CrossRef]

- Andreo-Martínez, P.; Martínez-Gonzlez, A. E. Una Propuesta de Probiótico Basada En El Bifidobacterium Para Autismo. Rev. Española Nutr. Humana y Dietética 2022, 26 (Supl. 1). https://doi.org/10.14306/renhyd.26.S1.1429. [CrossRef]

- Unno, T.; Sakuma, M.; Mitsuhashi, S. Effect of Dietary Supplementation of (-)-Epigallocatechin Gallate on Gut Microbiota and Biomarkers of Colonic Fermentation in Rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo). 2014, 60 (3), 213–219. https://doi.org/10.3177/JNSV.60.213. [CrossRef]

- Tarek El-Banna; El-Aziz, A. A.; EL-Mahdy, N.; Samy, Y. Sherris Medical Microbiology, 4th Editio.; McGraw-Hill, 2004.

- Pérez de Rozas Ruiz de Gauna, A. M.; Badiola Sáiz, I.; Castellà Gómez, G.; Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Departament de Sanitat i d’Anatomia Animals.; Centre de Recerca de Sanitat Animal.; Institut de Recerca i Tecnologia Agroalimentàries. Utilización de Cepas de Bacteroides Spp. Como Probiótico En Conejos. TDX (Tesis Dr. en Xarxa) 2014.

- Jiang, C. C.; Lin, L. S.; Long, S.; Ke, X. Y.; Fukunaga, K.; Lu, Y. M.; Han, F. Signalling Pathways in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/S41392-022-01081-0. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. J.; Lang, J. D.; Yang, J.; Long, B.; Liu, X. D.; Zeng, X. F.; Tian, G.; You, X. Differences of Gut Microbiota and Behavioral Symptoms between Two Subgroups of Autistic Children Based on ΓδT Cells-Derived IFN-γ Levels: A Preliminary Study. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1100816. https://doi.org/10.3389/FIMMU.2023.1100816/FULL. [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, S.; Noda, S.; Aiba, Y.; Takagi, A.; Sakamoto, M.; Benno, Y.; Koga, Y. Bacteroides Ovatus as the Predominant Commensal Intestinal Microbe Causing a Systemic Antibody Response in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2002, 9 (1), 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1128/CDLI.9.1.54-59.2002/ASSET/31DDD9DA-5B8D-48DB-B7EC-B7A51912F2F0/ASSETS/GRAPHIC/CD0120142004.JPEG. [CrossRef]

- Srikantha, P.; Hasan Mohajeri, M. The Possible Role of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain-Axis in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20 (9). https://doi.org/10.3390/IJMS20092115. [CrossRef]

- Tett, A.; Huang, K. D.; Asnicar, F.; Fehlner-Peach, H.; Pasolli, E.; Karcher, N.; Armanini, F.; Manghi, P.; Bonham, K.; Zolfo, M.; De Filippis, F.; Magnabosco, C.; Bonneau, R.; Lusingu, J.; Amuasi, J.; Reinhard, K.; Rattei, T.; Boulund, F.; Engstrand, L.; Zink, A.; Collado, M. C.; Littman, D. R.; Eibach, D.; Ercolini, D.; Rota-Stabelli, O.; Huttenhower, C.; Maixner, F.; Segata, N. The Prevotella Copri Complex Comprises Four Distinct Clades Underrepresented in Westernized Populations. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26 (5), 666-679.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHOM.2019.08.018/ATTACHMENT/EA844E49-40CE-4DF3-B25D-3B09A250022A/MMC6.XLSX. [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, J.; O’Connor, E. M.; Shanahan, F. Review Article: Dietary Fibre in the Era of Microbiome Science. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 49 (5), 506–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/APT.15129. [CrossRef]

- Matusheski, N. V.; Caffrey, A.; Christensen, L.; Mezgec, S.; Surendran, S.; Hjorth, M. F.; McNulty, H.; Pentieva, K.; Roager, H. M.; Seljak, B. K.; Vimaleswaran, K. S.; Remmers, M.; Péter, S. Diets, Nutrients, Genes and the Microbiome: Recent Advances in Personalised Nutrition. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 126 (10), 1489–1497. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114521000374. [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Santos, C. P.; Whisner, C. M. The Key to Successful Weight Loss on a High-Fiber Diet May Be in Gut Microbiome Prevotella Abundance. J. Nutr. 2019, 149 (12), 2083–2084. https://doi.org/10.1093/JN/NXZ248. [CrossRef]

- Dandachi, I.; Anani, H.; Hadjadj, L.; Brahimi, S.; Lagier, J. C.; Daoud, Z.; Rolain, J. M. Genome Analysis of Lachnoclostridium Phocaeense Isolated from a Patient after Kidney Transplantation in Marseille. New Microbes New Infect. 2021, 41, 100863. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NMNI.2021.100863. [CrossRef]

- McNabney, S. M.; Henagan, T. M. Short Chain Fatty Acids in the Colon and Peripheral Tissues: A Focus on Butyrate, Colon Cancer, Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Nutrients 2017, 9 (12). https://doi.org/10.3390/NU9121348. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, S.; Li, T.; Li, N.; Han, D.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Z. Z.; Zhang, S.; Pang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J. Gut Microbiota from Green Tea Polyphenol-Dosed Mice Improves Intestinal Epithelial Homeostasis and Ameliorates Experimental Colitis. Microbiome 2021, 9 (1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/S40168-021-01115-9/FIGURES/11. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, S.; Li, T.; Li, N.; Han, D.; Zhang, S.; Pang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J. Oral, but Not Rectal Delivery of Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Alleviates Colitis by Regulating the Gut Microbiota, Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Barrier Integrity. Res. Sq. 2020. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-52274/v1. [CrossRef]

- Amaral Montesino, C.; Abrego Sánchez, A.; Díaz Granados, M. A.; González Ponce, R.; Salinas Flores, A.; Rojas García, O. C.; Amaral Montesino, C.; Abrego Sánchez, A.; Díaz Granados, M. A.; González Ponce, R.; Salinas Flores, A.; Rojas García, O. C. Akkermansia Muciniphila, Una Ventana de Investigación Para La Regulación Del Metabolismo y Enfermedades Relacionadas. Nutr. Hosp. 2021, 38 (3), 675–676. https://doi.org/10.20960/NH.03598. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, N.; Mu, H.; Zhang, H.; Duan, J. Improved Viability of Akkermansia Muciniphila by Encapsulation in Spray Dried Succinate-Grafted Alginate Doped with Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 159, 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJBIOMAC.2020.05.055. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Jena, P. K.; Hui-Xin, L.; Hu, Y.; Nagar, N.; Bronner, D. N.; Settles, M. L.; Bäumler, A. J.; Wan, Y. J. Y. Obesity Treatment by Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate−regulated Bile Acid Signaling and Its Enriched Akkermansia Muciniphila. FASEB J. 2018, 32 (12), 6371–6384. https://doi.org/10.1096/FJ.201800370R. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, K.; Jing, N.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, X. EGCG Regulates Fatty Acid Metabolism of High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice in Association with Enrichment of Gut Akkermansia Muciniphila. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 75, 104261. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFF.2020.104261. [CrossRef]

- Manrique, D.; Elie, V. Ácidos Grasos de Cadena Corta (Ácido Butírico) y Patologías Intestinales. Nutr. Hosp. 2017, 34, 58–61. https://doi.org/10.20960/nh.1573. [CrossRef]

- Rivière, A.; Selak, M.; Lantin, D.; Leroy, F.; De Vuyst, L. Bifidobacteria and Butyrate-Producing Colon Bacteria: Importance and Strategies for Their Stimulation in the Human Gut. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7 (JUN), 979. https://doi.org/10.3389/FMICB.2016.00979/BIBTEX. [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, M. K.; AlKhulaifi, M. M.; Al Farraj, D. A.; Somily, A. M.; Albarrag, A. M. Incidence of Clostridium Perfringens and Its Toxin Genes in the Gut of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Anaerobe 2020, 61, 102114. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ANAEROBE.2019.102114. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, T.; Gao, J.; Cai, Y.; Fan, X. Alteration of Gut Microbiota: New Strategy for Treating Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 192. https://doi.org/10.3389/FCELL.2022.792490/BIBTEX. [CrossRef]

- Sandler, R. H.; Finegold, S. M.; Bolte, E. R.; Buchanan, C. P.; Maxwell, A. P.; Väisänen, M. L.; Nelson, M. N.; Wexler, H. M. Short-Term Benefit From Oral Vancomycin Treatment of Regressive-Onset Autism. https://doi.org/10.1177/088307380001500701 2000, 15 (7), 429–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/088307380001500701. [CrossRef]

- Enterobacterias - EcuRed. https://www.ecured.cu/Enterobacterias (accessed 2022-10-11).

- Mohammad, F. K.; Palukuri, M. V.; Shivakumar, S.; Rengaswamy, R.; Sahoo, S. A Computational Framework for Studying Gut-Brain Axis in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPHYS.2022.760753. [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, D. A.; Frye, R. E. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2012, 17 (3), 290–314. https://doi.org/10.1038/MP.2010.136. [CrossRef]

- Matelski, L.; Van de Water, J. Risk Factors in Autism: Thinking Outside the Brain. J. Autoimmun. 2016, 67, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAUT.2015.11.003. [CrossRef]

- McAllister, A. K. Immune Contributions to Cause and Effect in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 81 (5), 380–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOPSYCH.2016.12.024. [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, A.; Van De Water, J. The Role of the Immune System in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42 (1), 284–298. https://doi.org/10.1038/NPP.2016.158. [CrossRef]

- Bielekova, B.; Komori, M.; Xu, Q.; Reich, D. S.; Wu, T. Cerebrospinal Fluid IL-12p40, CXCL13 and IL-8 as a Combinatorial Biomarker of Active Intrathecal Inflammation. PLoS One 2012, 7 (11), e48370. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0048370. [CrossRef]

- Gumusoglu, S. B.; Fine, R. S.; Murray, S. J.; Bittle, J. L.; Stevens, H. E. The Role of IL-6 in Neurodevelopment after Prenatal Stress. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2017, 65, 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBI.2017.05.015. [CrossRef]

- Leviton, A.; Joseph, R. M.; Allred, E. N.; Fichorova, R. N.; O’Shea, T. M.; Kuban, K. K. C.; Dammann, O. The Risk of Neurodevelopmental Disorders at Age 10 Years Associated with Blood Concentrations of Interleukins 4 and 10 during the First Postnatal Month of Children Born Extremely Preterm. Cytokine 2018, 110, 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CYTO.2018.05.004. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, Y.; Shi, L.; Liu, M.; Wu, R.; Xia, K.; Zhang, F.; Ou, J.; Zhao, J. Autism Spectrum Disorder and Severe Social Impairment Associated with Elevated Plasma Interleukin-8. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 89 (3), 591–597. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41390-020-0910-X. [CrossRef]

- Jyonouchi, H.; Geng, L.; Davidow, A. L. Cytokine Profiles by Peripheral Blood Monocytes Are Associated with Changes in Behavioral Symptoms Following Immune Insults in a Subset of ASD Subjects: An Inflammatory Subtype? J. Neuroinflammation 2014, 11 (1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12974-014-0187-2/FIGURES/5. [CrossRef]

- Jyonouchi, H.; Geng, L.; Streck, D. L.; Dermody, J. J.; Toruner, G. A. MicroRNA Expression Changes in Association with Changes in Interleukin-1ß/Interleukin10 Ratios Produced by Monocytes in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Their Association with Neuropsychiatric Symptoms and Comorbid Conditions (Observational Study). J. Neuroinflammation 2017, 14 (1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12974-017-1003-6/TABLES/8. [CrossRef]

- Masi, A.; Quintana, D. S.; Glozier, N.; Lloyd, A. R.; Hickie, I. B.; Guastella, A. J. Cytokine Aberrations in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2015, 20 (4), 440–446. https://doi.org/10.1038/MP.2014.59. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Lin, S.; Zheng, B.; Cheung, P. C. K. Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Control of Energy Metabolism. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58 (8), 1243–1249. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2016.1245650. [CrossRef]

- Codina-Solà, M.; Rodríguez-Santiago, B.; Homs, A.; Santoyo, J.; Rigau, M.; Aznar-Laín, G.; Del Campo, M.; Gener, B.; Gabau, E.; Botella, M. P.; Gutiérrez-Arumí, A.; Antiñolo, G.; Pérez-Jurado, L. A.; Cuscó, I. Integrated Analysis of Whole-Exome Sequencing and Transcriptome Profiling in Males with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Mol. Autism 2015, 6 (1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13229-015-0017-0/FIGURES/3. [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund, G.; Meguid, N. A.; El-Bana, M. A.; Tinkov, A. A.; Saad, K.; Dadar, M.; Hemimi, M.; Skalny, A. V.; Hosnedlová, B.; Kizek, R.; Osredkar, J.; Urbina, M. A.; Fabjan, T.; El-Houfey, A. A.; Kałużna-Czaplińska, J.; Gątarek, P.; Chirumbolo, S. Oxidative Stress in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57 (5), 2314–2332. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12035-019-01742-2. [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, A.; Ahmad, S. F.; Attia, S. M.; AL-Ayadhi, L. Y.; Al-Harbi, N. O.; Bakheet, S. A. Dysregulated Enzymatic Antioxidant Network in Peripheral Neutrophils and Monocytes in Children with Autism. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 88, 352–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PNPBP.2018.08.020. [CrossRef]

- Messina, A.; Monda, V.; Sessa, F.; Valenzano, A.; Salerno, M.; Bitetti, I.; Precenzano, F.; Marotta, R.; Lavano, F.; Lavano, S. M.; Salerno, M.; Maltese, A.; Roccella, M.; Parisi, L.; Ferrentino, R. I.; Tripi, G.; Gallai, B.; Cibelli, G.; Monda, M.; Messina, G.; Carotenuto, M. Sympathetic, Metabolic Adaptations, and Oxidative Stress in Autism Spectrum Disorders: How Far from Physiology? Front. Physiol. 2018, 9 (MAR), 261. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPHYS.2018.00261/BIBTEX. [CrossRef]

- Fransen, M.; Nordgren, M.; Wang, B.; Apanasets, O. Role of Peroxisomes in ROS/RNS-Metabolism: Implications for Human Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1822 (9), 1363–1373. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBADIS.2011.12.001. [CrossRef]

- Cipolla, C. M.; Lodhi, I. J. Peroxisomal Dysfunction in Age-Related Diseases. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 28 (4), 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TEM.2016.12.003. [CrossRef]

- James, S. J.; Melnyk, S.; Jernigan, S.; Cleves, M. A.; Halsted, C. H.; Wong, D. H.; Cutler, P.; Bock, K.; Boris, M.; Bradstreet, J. J.; Baker, S. M.; Gaylor, D. W. Metabolic Endophenotype and Related Genotypes Are Associated with Oxidative Stress in Children with Autism. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2006, 141B (8), 947–956. https://doi.org/10.1002/AJMG.B.30366. [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; Bennuri, S. C.; Wynne, R.; Melnyk, S.; James, S. J.; Frye, R. E. Mitochondrial and Redox Abnormalities in Autism Lymphoblastoid Cells: A Sibling Control Study. FASEB J. 2017, 31 (3), 904–909. https://doi.org/10.1096/FJ.201601004R. [CrossRef]

- Ray, B.; Long, J. M.; Sokol, D. K.; Lahiri, D. K. Increased Secreted Amyloid Precursor Protein-α (SAPPα) in Severe Autism: Proposal of a Specific, Anabolic Pathway and Putative Biomarker. PLoS One 2011, 6 (6). https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0020405. [CrossRef]

- Sokol, D. K.; Maloney, B.; Long, J. M.; Ray, B.; Lahiri, D. K. Autism, Alzheimer Disease, and Fragile X: APP, FMRP, and MGluR5 Are Molecular Links. Neurology 2011, 76 (15), 1344–1352. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0B013E3182166DC7. [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, D. K.; Sokol, D. K.; Erickson, C.; Ray, B.; Ho, C. Y.; Maloney, B. Autism as Early Neurodevelopmental Disorder: Evidence for an SAPPα-Mediated Anabolic Pathway. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 94. https://doi.org/10.3389/FNCEL.2013.00094. [CrossRef]

- Sunand, K.; Mohan, G. K.; Bakshi, V. Synergetic Potential of Combination Probiotic Complex with Phytopharmaceuticals in Valproic Acid Induced Autism: Prenatal Model. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2021, 6 (03), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.21477/IJAPSR.6.3.02. [CrossRef]

- Avramovich-Tirosh, Y.; Reznichenko, L.; Amit, T.; Zheng, H.; Fridkin, M.; Weinreb, O.; Mandel, S.; Youdim, M. Neurorescue Activity, APP Regulation and Amyloid-Beta Peptide Reduction by Novel Multi-Functional Brain Permeable Iron- Chelating- Antioxidants, M-30 and Green Tea Polyphenol, EGCG. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2007, 4 (4), 403–411. https://doi.org/10.2174/156720507781788927. [CrossRef]

- Pogačnik, L.; Pirc, K.; Palmela, I.; Skrt, M.; Kwang, K. S.; Brites, D.; Brito, M. A.; Ulrih, N. P.; Silva, R. F. M. Potential for Brain Accessibility and Analysis of Stability of Selected Flavonoids in Relation to Neuroprotection in Vitro. Brain Res. 2016, 1651, 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BRAINRES.2016.09.020. [CrossRef]

- Porath, D.; Riegger, C.; Drewe, J.; Schwager, J. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Impairs Chemokine Production in Human Colon Epithelial Cell Lines. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 315 (3), 1172–1180. https://doi.org/10.1124/JPET.105.090167. [CrossRef]

- Frye, R. E.; Rossignol, D. A. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Can Connect the Diverse Medical Symptoms Associated with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Pediatr. Res. 2011, 69 (5 Pt 2). https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0B013E318212F16B. [CrossRef]

- Ming, X.; Stein, T. P.; Barnes, V.; Rhodes, N.; Guo, L. Metabolic Perturbance in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Metabolomics Study. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11 (12), 5856–5862. https://doi.org/10.1021/PR300910N. [CrossRef]

- Frye, R. E.; Rose, S.; Slattery, J.; MacFabe, D. F. Gastrointestinal Dysfunction in Autism Spectrum Disorder: The Role of the Mitochondria and the Enteric Microbiome. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2015, 26 (0). https://doi.org/10.3402/MEHD.V26.27458. [CrossRef]

- Sergent, T.; Piront, N.; Meurice, J.; Toussaint, O.; Schneider, Y. J. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Dietary Phenolic Compounds in an in Vitro Model of Inflamed Human Intestinal Epithelium. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010, 188 (3), 659–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CBI.2010.08.007. [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, S.; Naik, B.; Ramachandra, N. B. Mucosa-Associated Specific Bacterial Species Disrupt the Intestinal Epithelial Barrier in the Autism Phenome. Brain, Behav. Immun. - Heal. 2021, 15, 100269. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBIH.2021.100269. [CrossRef]

- DeSantis, T. Z.; Hugenholtz, P.; Larsen, N.; Rojas, M.; Brodie, E. L.; Keller, K.; Huber, T.; Dalevi, D.; Hu, P.; Andersen, G. L. Greengenes, a Chimera-Checked 16S RRNA Gene Database and Workbench Compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72 (7), 5069–5072. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, E.; Sun, Z.; Fu, D.; Duan, G.; Jiang, M.; Yu, Y.; Mei, L.; Yang, P.; Tang, Y.; Zheng, P. Altered Gut Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acids in Chinese Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Sci. Reports 2019 91 2019, 9 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36430-z. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ma, W.; Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Wang, J. Analysis of Gut Microbiota Profiles and Microbe-Disease Associations in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in China. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-018-32219-2. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. T.; Davis-Richardson, A. G.; Giongo, A.; Gano, K. A.; Crabb, D. B.; Mukherjee, N.; Casella, G.; Drew, J. C.; Ilonen, J.; Knip, M.; Hyöty, H.; Veijola, R.; Simell, T.; Simell, O.; Neu, J.; Wasserfall, C. H.; Schatz, D.; Atkinson, M. A.; Triplett, E. W. Gut Microbiome Metagenomics Analysis Suggests a Functional Model for the Development of Autoimmunity for Type 1 Diabetes. PLoS One 2011, 6 (10). https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0025792. [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; Bennuri, S. C.; Murray, K. F.; Buie, T.; Winter, H.; Frye, R. E. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Gastrointestinal Mucosa of Children with Autism: A Blinded Case-Control Study. PLoS One 2017, 12 (10). https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0186377. [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; Bennuri, S. C.; Davis, J. E.; Wynne, R.; Slattery, J. C.; Tippett, M.; Delhey, L.; Melnyk, S.; Kahler, S. G.; MacFabe, D. F.; Frye, R. E. Butyrate Enhances Mitochondrial Function during Oxidative Stress in Cell Lines from Boys with Autism. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/S41398-017-0089-Z. [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, C.; Hoxha, E.; Lippiello, P.; Balbo, I.; Russo, R.; Tempia, F.; Miniaci, M. C. Maternal Treatment with Sodium Butyrate Reduces the Development of Autism-like Traits in Mice Offspring. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113870. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOPHA.2022.113870. [CrossRef]

- Kang, D. W.; Ilhan, Z. E.; Isern, N. G.; Hoyt, D. W.; Howsmon, D. P.; Shaffer, M.; Lozupone, C. A.; Hahn, J.; Adams, J. B.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R. Differences in Fecal Microbial Metabolites and Microbiota of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Anaerobe 2018, 49, 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ANAEROBE.2017.12.007. [CrossRef]

- Andriamihaja, M.; Lan, A.; Beaumont, M.; Audebert, M.; Wong, X.; Yamada, K.; Yin, Y.; Tomé, D.; Carrasco-Pozo, C.; Gotteland, M.; Kong, X.; Blachier, F. The Deleterious Metabolic and Genotoxic Effects of the Bacterial Metabolite P-Cresol on Colonic Epithelial Cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 85, 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FREERADBIOMED.2015.04.004. [CrossRef]

- Unno, T.; Ichitani, M. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Decreases Plasma and Urinary Levels of p-Cresol by Modulating Gut Microbiota in Mice. ACS Omega 2022, 7 (44), 40034–40041. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACSOMEGA.2C04731/SUPPL_FILE/AO2C04731_SI_001.PDF. [CrossRef]

- Unno, K.; Pervin, M.; Nakagawa, A.; Iguchi, K.; Hara, A.; Takagaki, A.; Nanjo, F.; Minami, A.; Nakamura, Y. Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability of Green Tea Catechin Metabolites and Their Neuritogenic Activity in Human Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61 (12), 1700294. https://doi.org/10.1002/MNFR.201700294. [CrossRef]

- Kohri, T.; Matsumoto, N.; Yamakawa, M.; Suzuki, M.; Nanjo, F.; Hara, Y.; Oku, N. Metabolic Fate of (−)-[4-3H]Epigallocatechin Gallate in Rats after Oral Administration. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 49, 4102–4112. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf001491+. [CrossRef]

- Pervin, M.; Unno, K.; Takagaki, A.; Isemura, M.; Nakamura, Y. Function of Green Tea Catechins in the Brain: Epigallocatechin Gallate and Its Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20 (15). https://doi.org/10.3390/IJMS20153630. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J. D.; Rice, J. E.; Hong, J.; Hou, Z.; Yang, C. S. Synthesis and Biological Activity of the Tea Catechin Metabolites, M4 and M6 and Their Methoxy-Derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15 (4), 873–876. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BMCL.2004.12.070. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. H.; Won, Y. S.; Yang, X.; Kumazoe, M.; Yamashita, S.; Hara, A.; Takagaki, A.; Goto, K.; Nanjo, F.; Tachibana, H. Green Tea Catechin Metabolites Exert Immunoregulatory Effects on CD4(+) T Cell and Natural Killer Cell Activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64 (18), 3591–3597. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.JAFC.6B01115. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lee, M.-J.; Li, H.; Yang, C. S. Absorption, Distribution, and Elimination of Tea Polyphenols in Rats. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1997, 25 (9).

- Kim, S.; Lee, M. J.; Hong, J.; Li, C.; Smith, T. J.; Yang, G. Y.; Seril, D. N.; Yang, C. S. Plasma and Tissue Levels of Tea Catechins in Rats and Mice during Chronic Consumption of Green Tea Polyphenols. Nutr. Cancer 2000, 37 (1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327914NC3701_5. [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.; Ettcheto, M.; Chang, J. H.; Barroso, E.; Espina, M.; Kühne, B. A.; Barenys, M.; Auladell, C.; Folch, J.; Souto, E. B.; Camins, A.; Turowski, P.; García, M. L. Dual-Drug Loaded Nanoparticles of Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG)/Ascorbic Acid Enhance Therapeutic Efficacy of EGCG in a APPswe/PS1dE9 Alzheimer’s Disease Mice Model. J. Control. Release 2019, 301, 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCONREL.2019.03.010. [CrossRef]

- Abbasalipour, H.; Hajizadeh Moghaddam, A.; Ranjbar, M. Sumac and Gallic Acid-Loaded Nanophytosomes Ameliorate Hippocampal Oxidative Stress via Regulation of Nrf2/Keap1 Pathway in Autistic Rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2022, 36 (6). https://doi.org/10.1002/JBT.23035. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).