Submitted:

13 June 2023

Posted:

14 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

2.1. About the Strategy of Synthesis

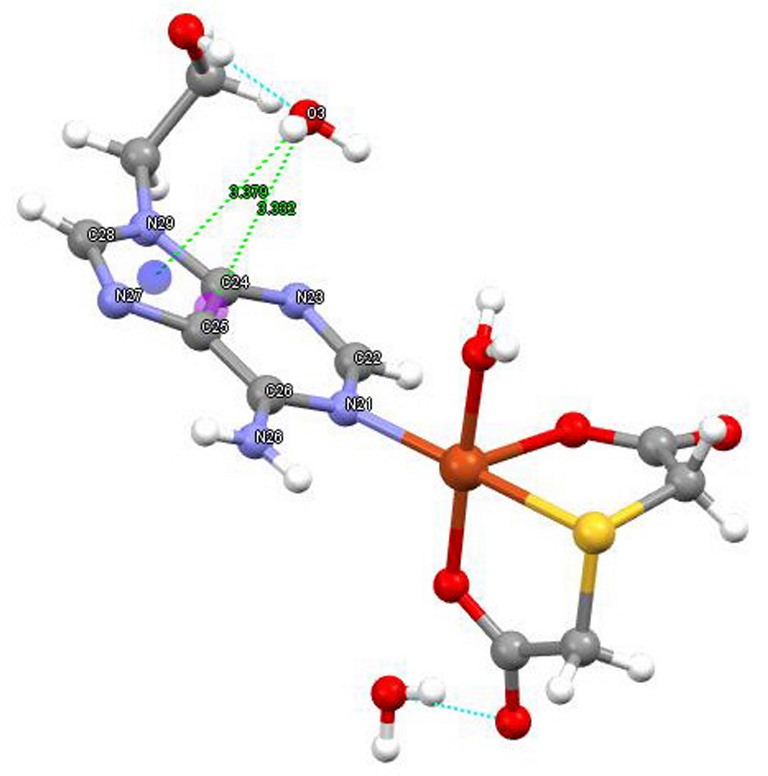

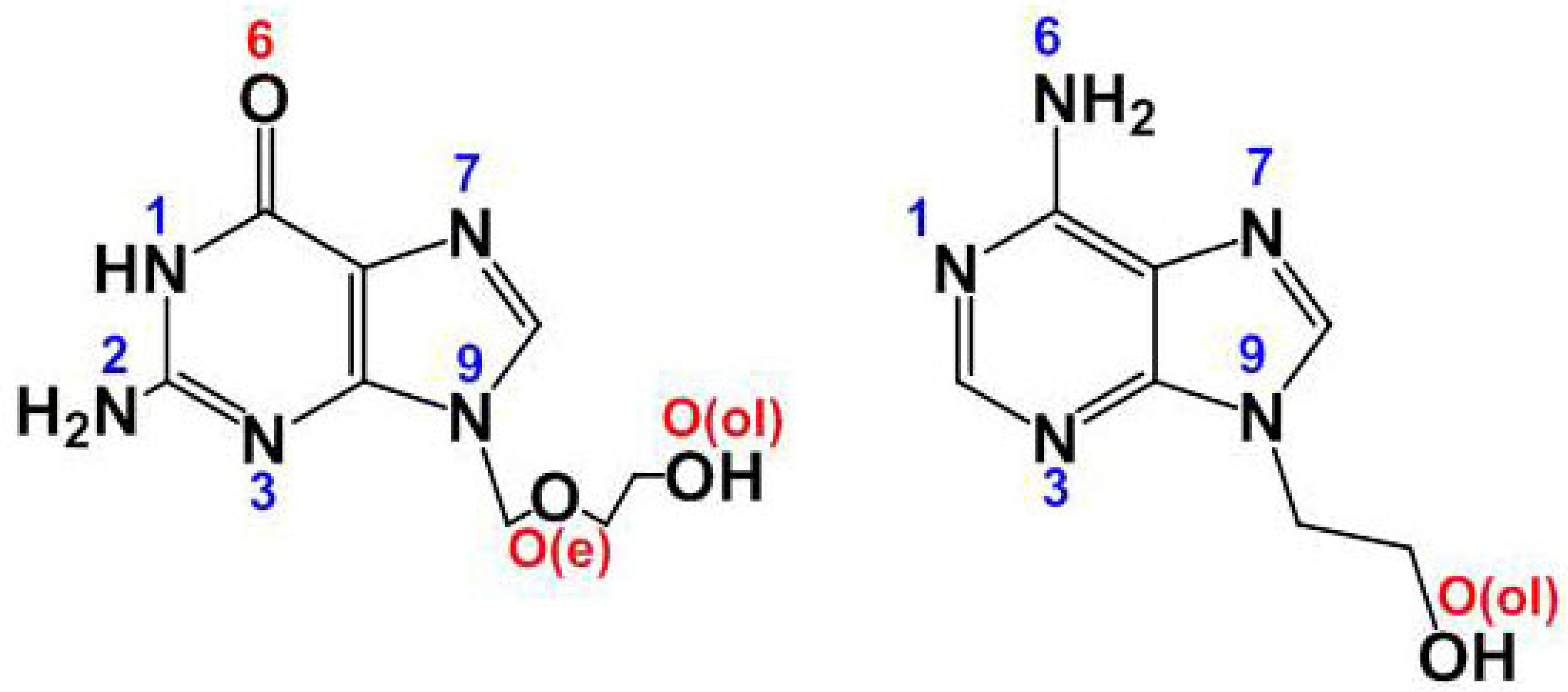

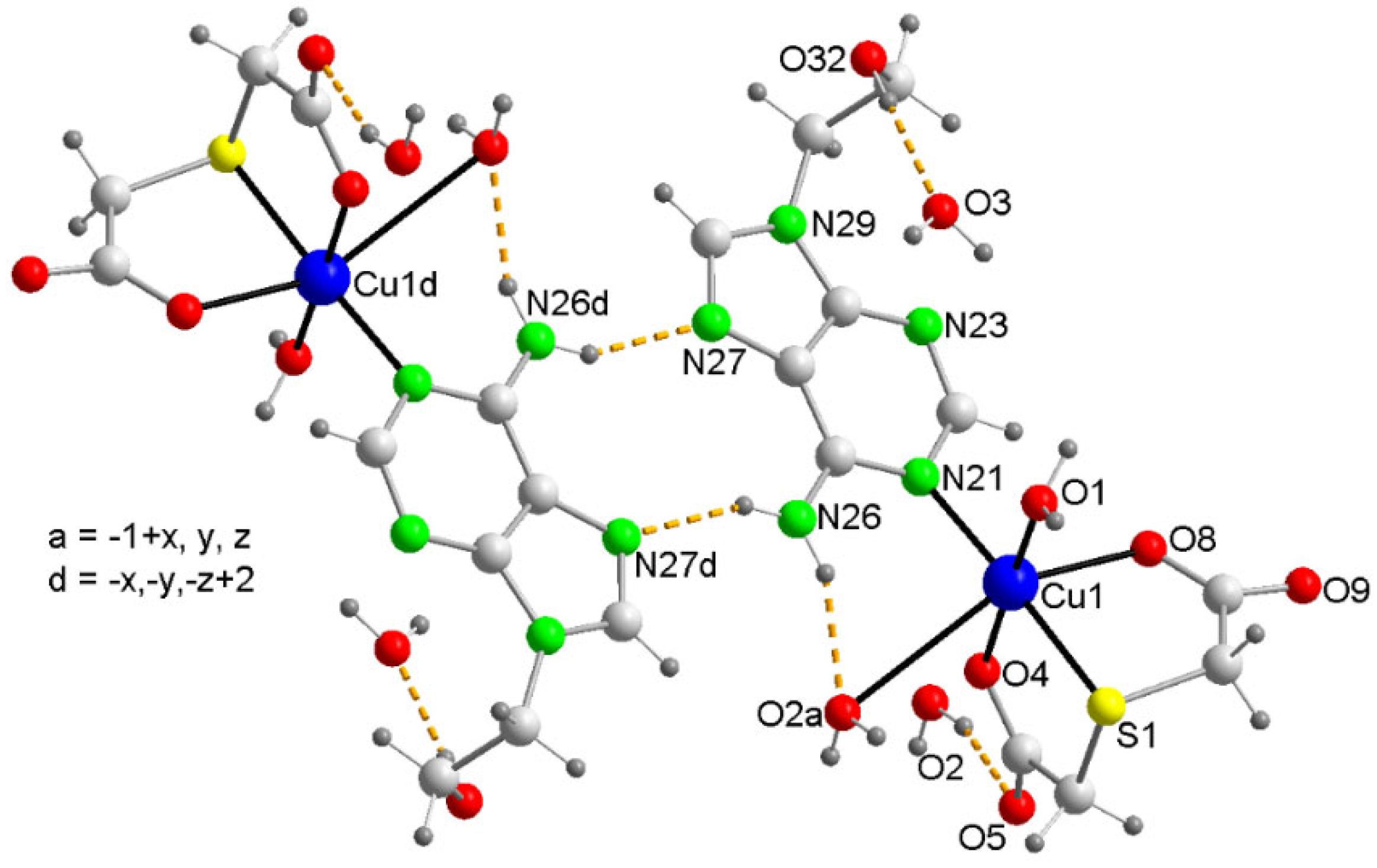

2.2. Molecular and Crystal Structure of Compound 1 and Their Relevant Significance for Molecular and Supra-Molecular Recognition

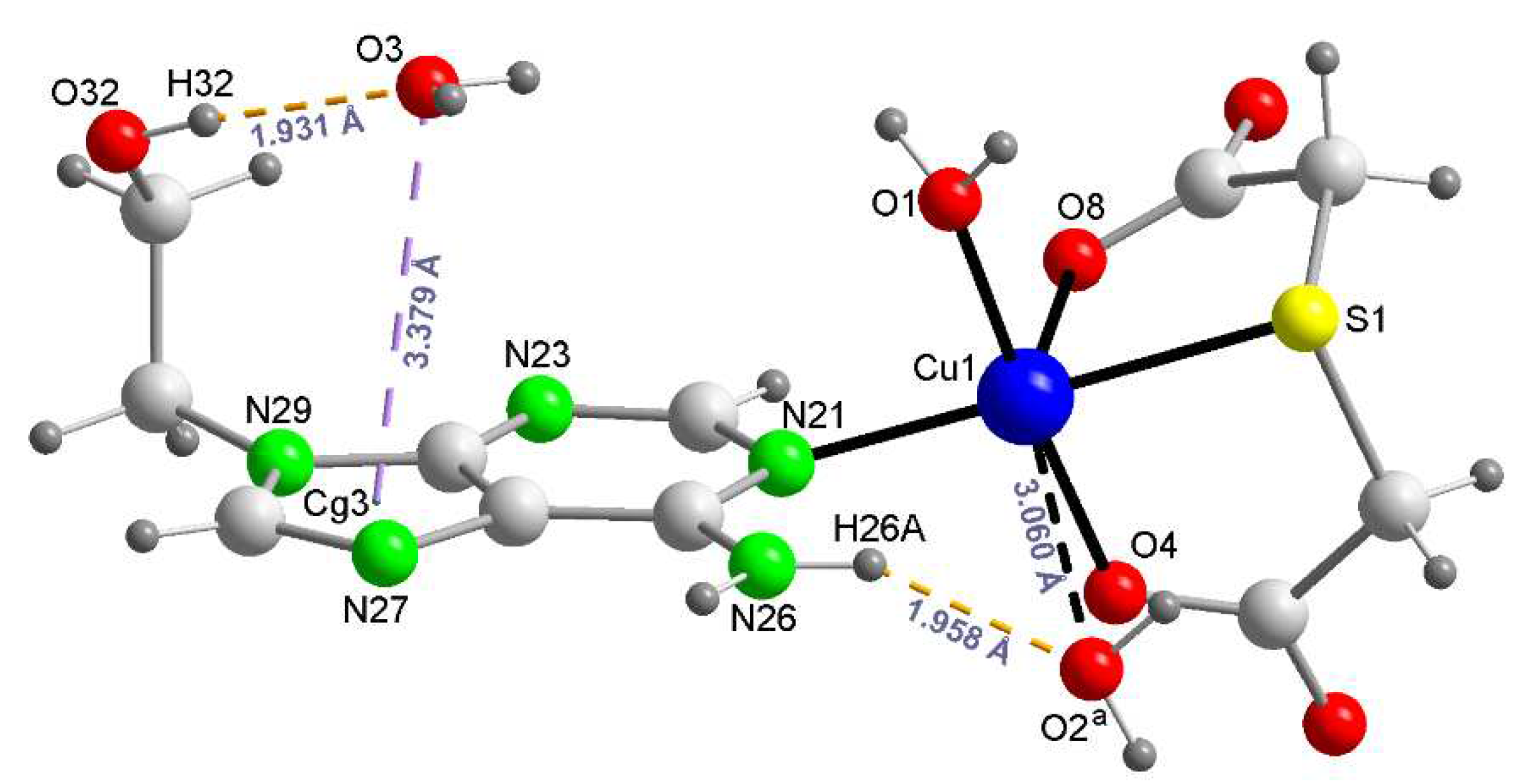

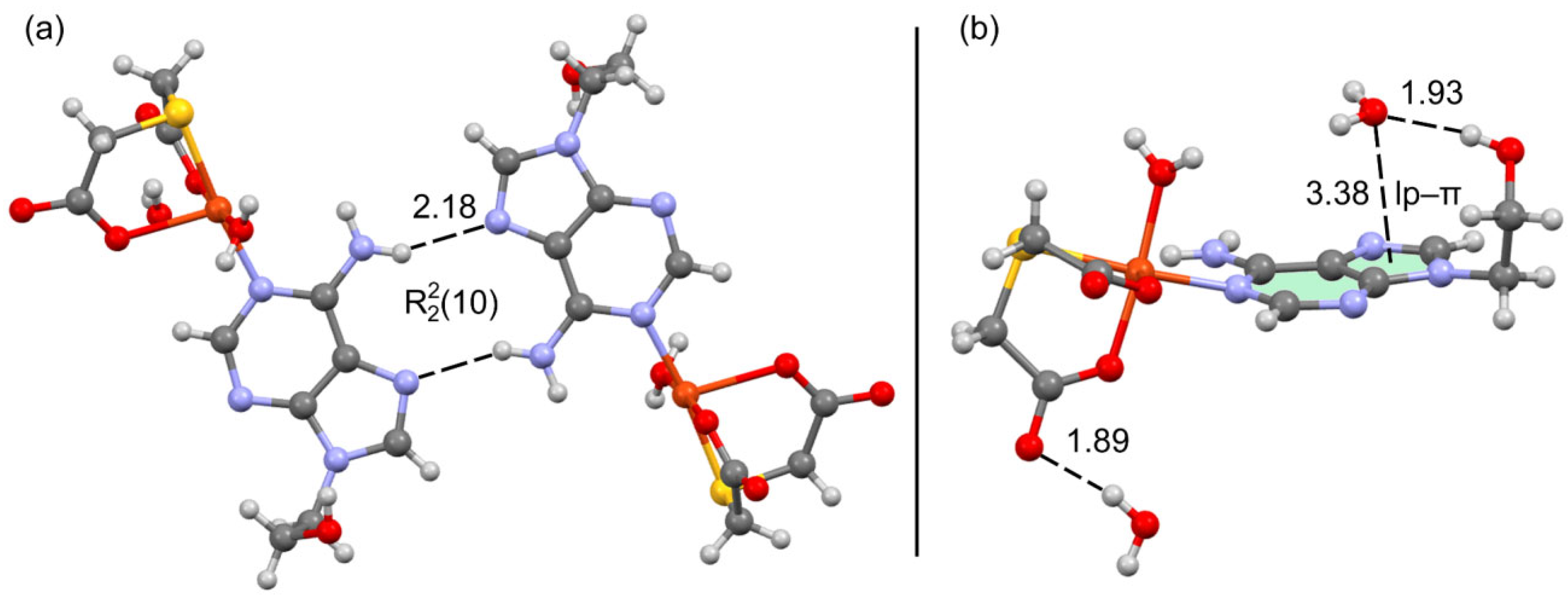

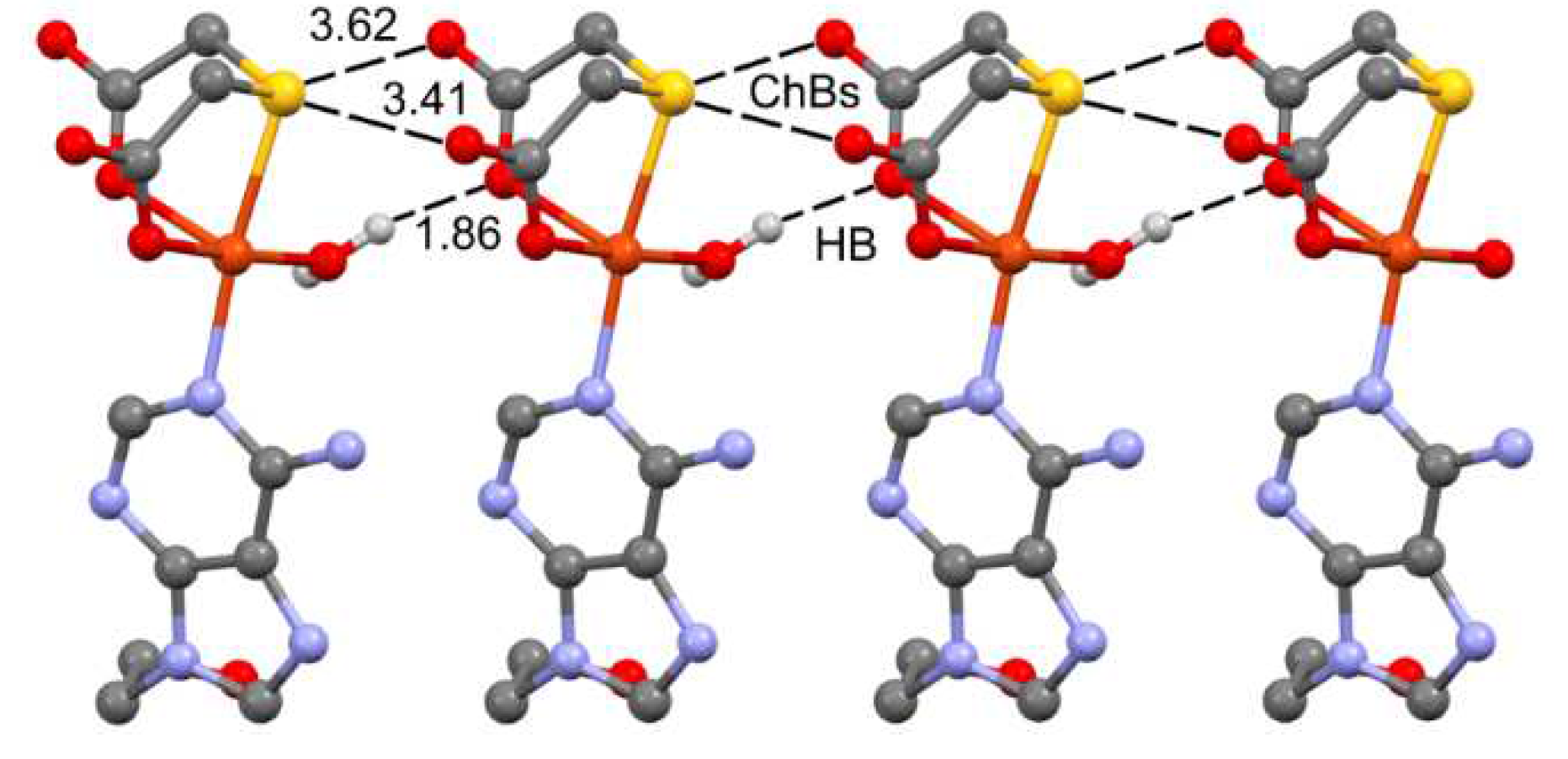

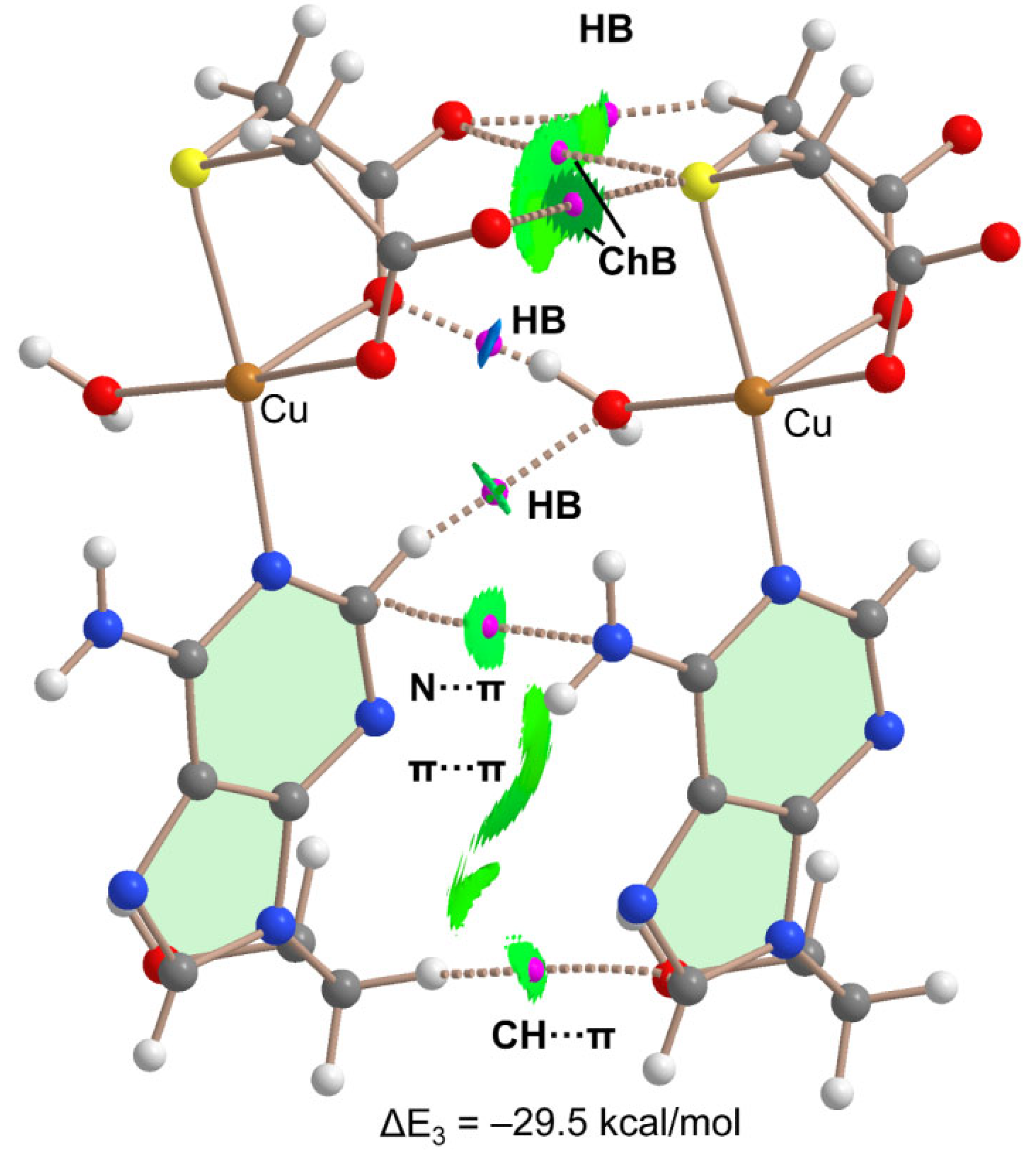

2.3. Molecular and Crystal Structures of Compound [Cu(tda)(9heade)(H2O)]·2H2O (1)

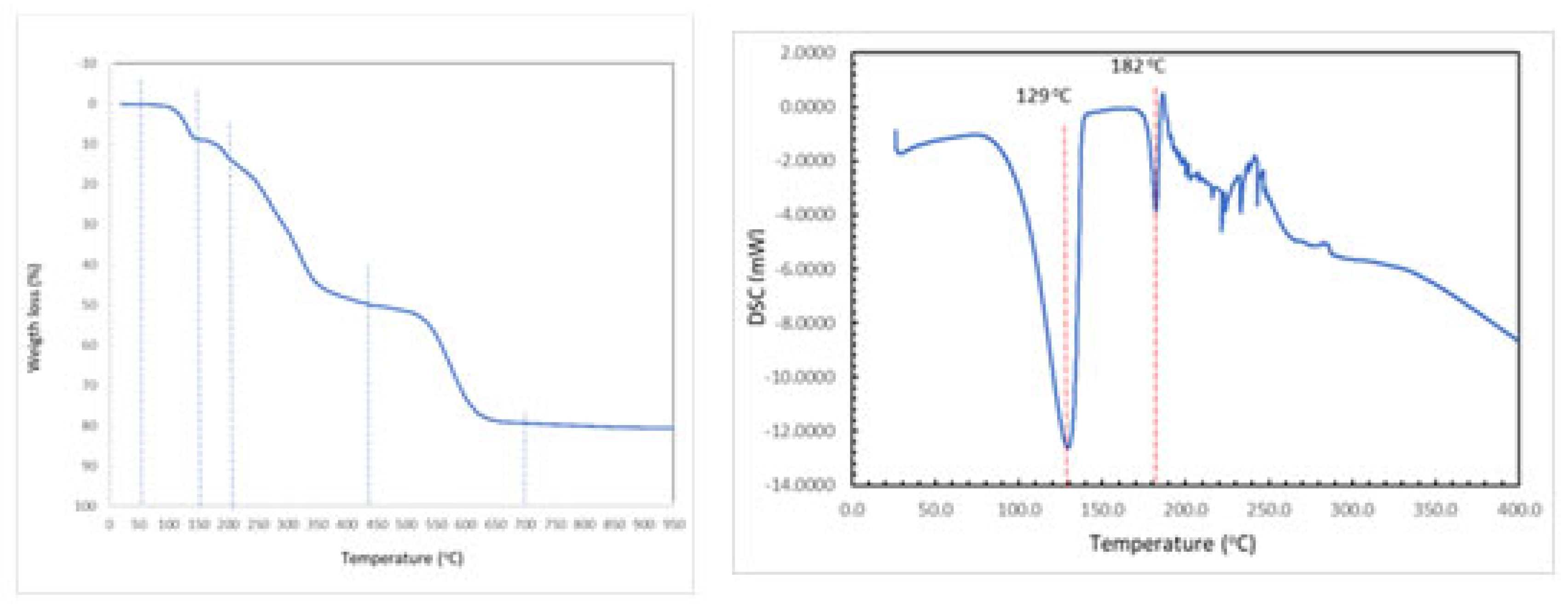

2.4. Physical Properties

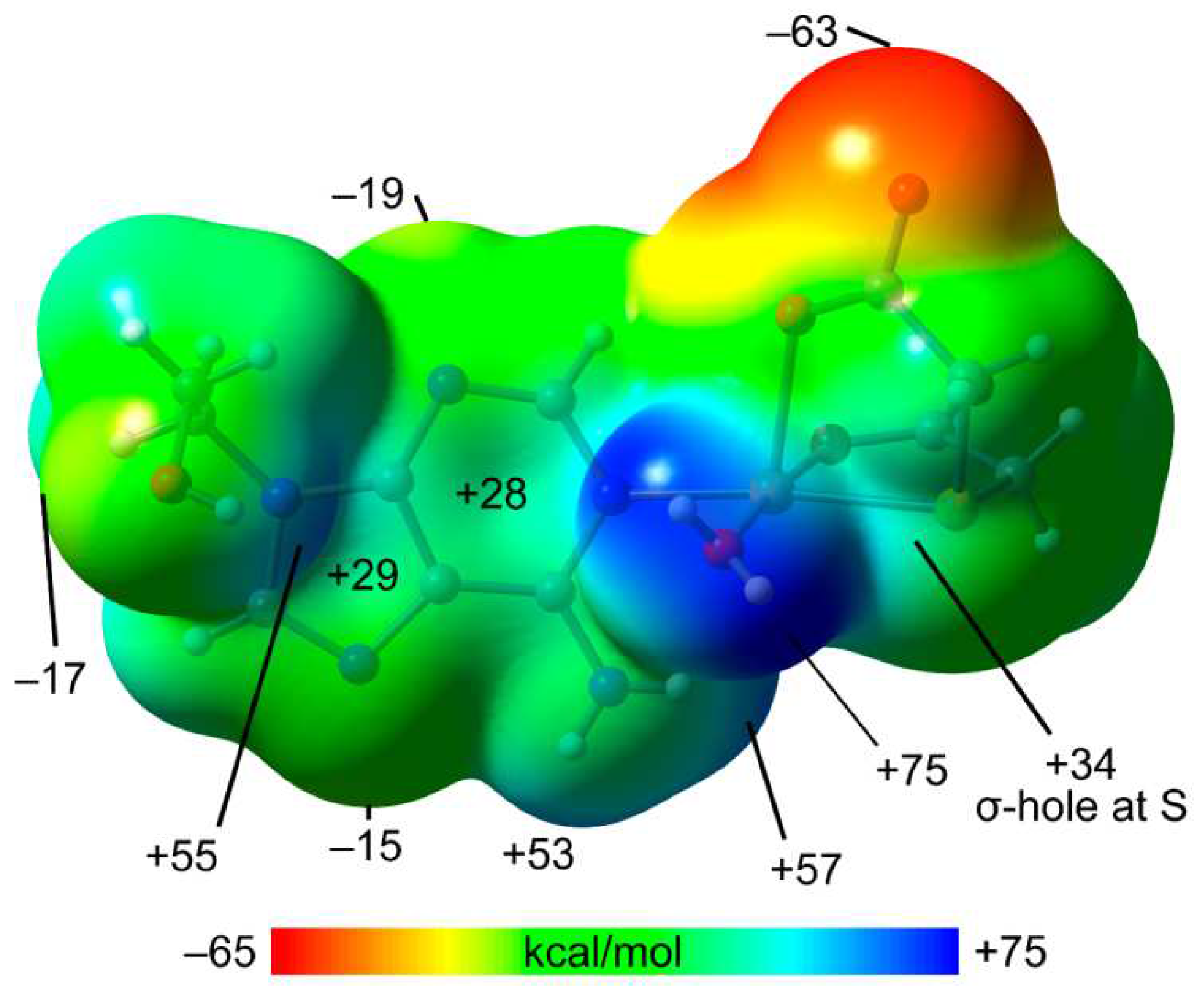

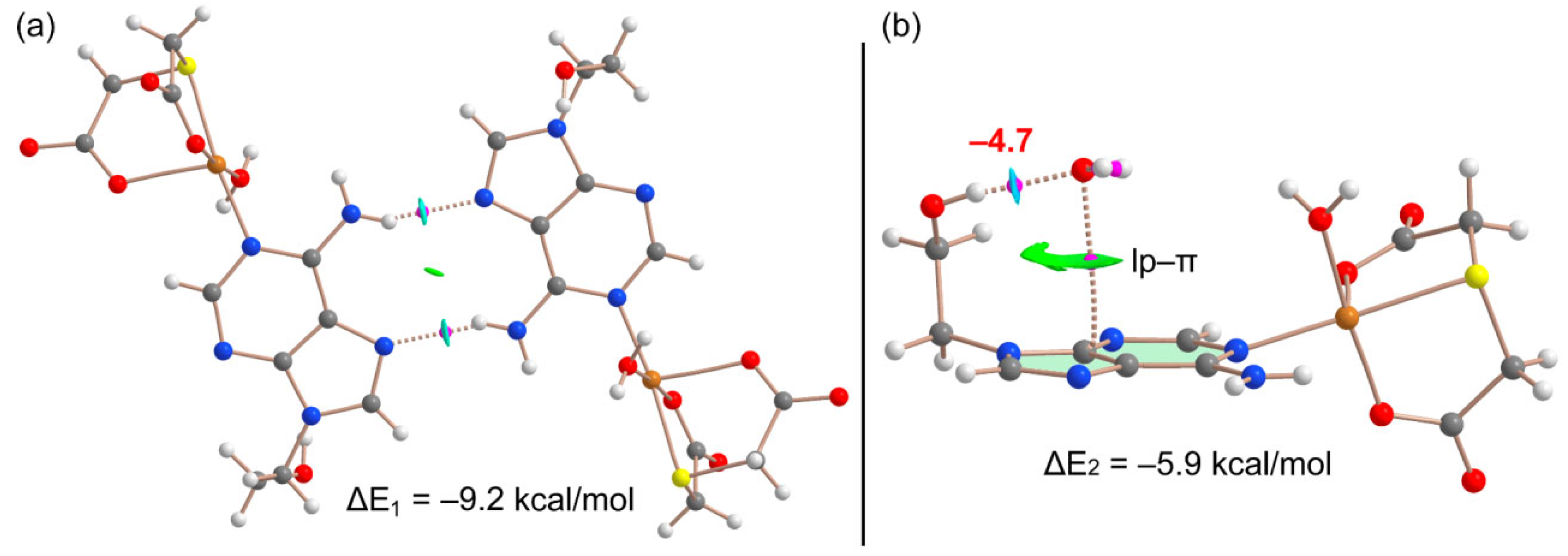

2.5. DFT Calculations

3. Concluding Remarks

4. Materials and Methods

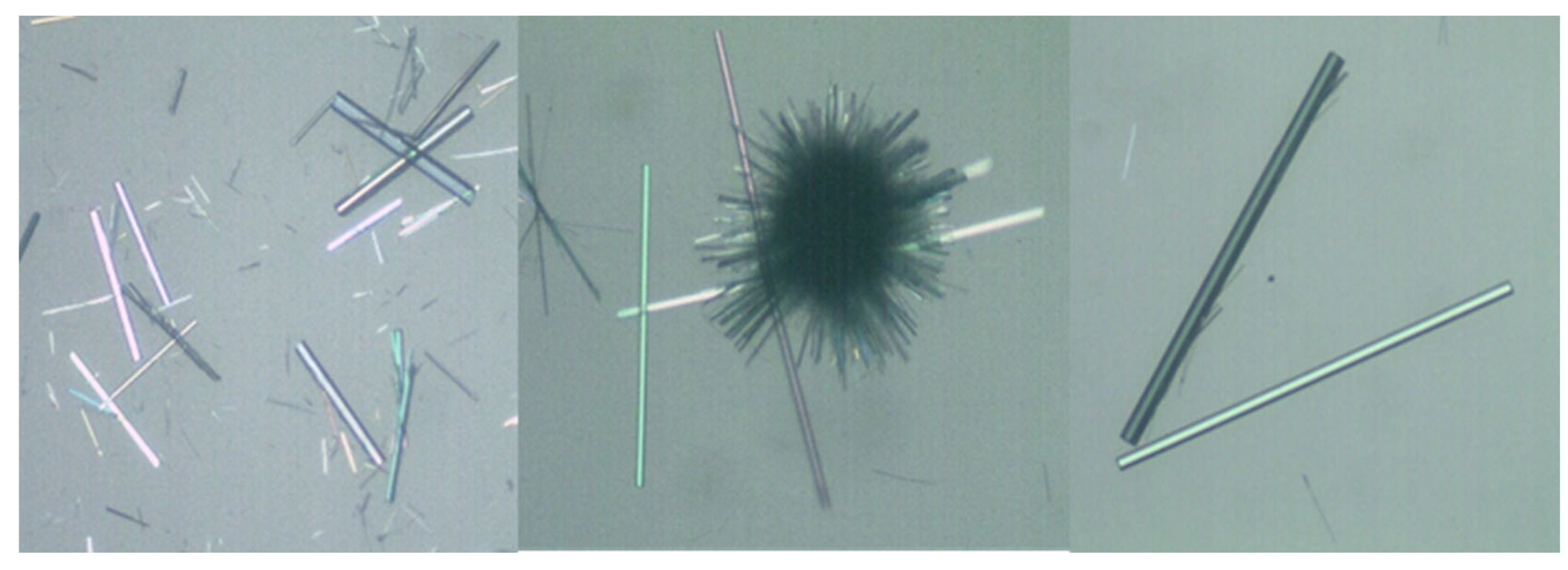

4.1. Reagents and Synthesis of Compound 1

4.2. Physical Measurements

4.3. Crystallography

4.4. Computational Details

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lehn, J.M. Perspectives in Supramolecular Chemistry-From Molecular Recognition towards Molecular Information Processing and Self-Organization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1990, 29, 1304–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persch, E.; Dumele, O.; Diederich, F. Molecular Recognition in Chemical and Biological Systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 3290–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebek, J. Molecular Recognition with Model Systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1990, 29, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmont-Sánchez, J.C.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D.; Navarrete-Casas, R.; Frontera, A.; Castiñeiras, A.; Niclós-Gutiérrez, J.; Matilla-Hernández, A. A tetranuclear Ni(II)-cubane cluster molecule build by four µ3-O-methanolate (MeO) ligands, externally cohesive by four unprecedented bridging µ2-N7,O6-acyclovirate (acv-H) anions. Crystals 2023, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Martín, A.; Brandi-Blanco, M.P.; Matilla-Hernández, A.; El Bakkali, H.; Nurchi, V.M.; González-Párez, J.M.; Castiñeiras, A.; Niclós-Gutiérrez, J. Unravelling the versatile metal binding modes of adenine: Looking at the molecular recognition patterns of deaza- and aza-adenines in mixed ligand metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 2814–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amo-Ochoa, P.; Zamora, F. Coordination polymers with nucleobases: From structural aspects to potential applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 276, 34–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi-Blanco, M.P.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D. , Domínguez-Martín, A.; Matilla-Hernández, A.; González-Pérez, J.M.; Castiñeiras, A.; Niclós-Gutiérrez, J. Molecular recognition modes between adenine or adeniniun(1+) ion and binary MII(pdc) chelates (M = Co-Zn; pdc = pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylate(2-) ion). J. Inorg. Biochem. 2013, 127, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaled Hassanein, K.; Castillo, O.; Gómez-García, C.J.; Zamora, F.; Amo-Ochoa, P. Asymmetric and symmetric dicopper(II) paddle-wheel units with modified nucleobases. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 5485–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Toro, I.; Domínguez-Martín, A.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D.; González-Pérez, J.M.; Castiñeiras, A.; Niclós-Gutiérrez, J. Highest reported denticity of a synthetic nucleoside in the unprecedented tetradentate mode of acyclovir. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 4282–4286. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 4282–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammud, H.H.; Travis Holman, K.; Al-Noaimi, M.; Sadiq Sheikh, N.; Ghannoum, A.M.; Bouhadir, K.H.; Masoud, M.S.; Karnati, R.K. Structures of selected transition metal complexes with 9-(2-hydroxyethyl)adenine: Potentiometric complexation and DFT studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1205, 127548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-González, N.; García-Rubiño, M.E.; Domínguez-Martín, A.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D.; Franconetti, A.; Frontera, A.; Castiñeiras, A.; González-Pérez, J.M.; Niclós-Gutiérrez, J. Molecular and supra-molecular recognition patterns in ternary copper(II) or zinc(II) complexes with selected rigid-planar chelators and a synthetic adenine-nucleoside. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 203, 110920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rubiño, M.E.; Matilla-Hernández, A.; Frontera, A.; Lezama, L.; Niclós-Gutiérrez, J.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D. Dicopper(II)-EDTA Chelate as a bicephalic receptor model for a synthetic adenine nucleoside. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belmont-Sánchez, J.C.; García-Rubiño, M.E.; Frontera, A.; Matilla-Hernández, A.; Castiñeiras, A.; Niclós-Gutiérrez, J. Novel Cd(II) coordination polymers afforded with EDTA or trans-1,2-CDTA chelators and imidazole, adenine, or 9-(2-hydroxyethyl)adenine coligands. Crystals 2020, 10, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushrutha, S.R.; Hota, R.; Natarajan, S. Adenine-Based Coordination Polymers: Synthesis, Structure, and Properties. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2962–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, G.C.; McClellan, A.L. The Hydrogen Bond; W.H. Freeman & Co.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Desiraju, G.R.; Steiner, T. The Weak Hydrogen Bond. In Structural Chemistry and Biology; International Union of Crystallography, Oxford Science Publications: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gilli, G.; Gilli, P. The Nature of the Hydrogen Bond: Outline of a Comprehensive Hydrogen Bond Theory; International Union of Crystallography, Oxford Science Publications: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bauzá, A.; Mooibroek, T.J.; Frontera, A. The bright future of unconventional σ/π-hole interactions. ChemPhysChem 2015, 16, 2496–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aakeröy, C.B.; Bryce, D.L.; Desiraju, G.R.; Frontera, A.; C. Legon, A.; Nicotra, F.; Rissanen, K.; Scheiner, S.; Terraneo, G.; Metrangolo, P.; et al. Definition of the chalcogen bond (IUPAC Recommendations 2019). Pure Appl. Chem., 2019, 91, 1889–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S.; Clark, T.; Resnati, G. The σ-hole revisited. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 32166–32178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, D.J.; Ling, K.B.; Cockroft, S.L. The origin of chalcogen-bonding interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15160–15167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbanov, A.V.; Kuznetsov, M.L.; Mahmudov, K.T.; Pombeiro, A.J.L.; Resnati, G. Resonance assisted chalcogen bonding as a new synthon in the design of dyes. Chem.-Eur. J. 2020, 26, 14833–14837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priimagi, A.; Cavallo, G.; Metrangolo, P.; Resnati, G. The halogen bond in the design of functional supramolecular materials: Recent advances. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2686–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, K.E.; Murray, J.S.; Fanfrlík, J.; Řezáč, J.; Solá, R.J.; Concha, M.C.; Ramos, F.M.; Politzer, P. Halogen bond tunability I: The effects of aromatic fluorine substitution on the strengths of halogen-bonding interactions involving chlorine, bromine, and iodine. J. Mol. Model. 2011, 17, 3309–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomila, R.M.; Bauzá, A.; Frontera, A. Enhancing chalcogen bonding by metal coordination. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 5977–5982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontera, A.; Bauzá, A. Metal coordination enhances chalcogen bonds: CSD survey and theoretical calculations. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2022, 23, 4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopel, P.; Travnicek, Z.; Marek, J.; Korabik, M.; Mrozinski, J. Polyhedron 2003, 22, 411–418. 22. [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.K.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D.; Domínguez-Martín, A.; Brandi-Blanco, M.P.; González-Pérez, J.M.; Castiñeiras, a.; Niclós-Gutiérrez, J. Inorg Chem. 2011, 50, 10549–10551. [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh, A.; Safari, N.; Amani, V.; Notash, B.; Raei, F.; Eftekhar, F. ; Eftekhar, F. Iran J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2014, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, R.; Garland, M.T.; Manzur, J.; Peña, O.; Perec, M.; Spodine, E.; Vega, A. A dinuclear copper(II) complex involving monoatomic O-carboxylate bridging and Cu–S(thioether) bonds: [Cu(tda)(phen)]2·H2tda (tda-thiodiacetate, phen-phenanthroline). Inorg. Chim. Acta 1999, 286, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahwaz Ahmad, M.; Khalid, M.; Shahnawaz Khan, M.; Shahid, M.; Ahmad, M.; Monika; Ansaric, A. ; Ashafaq, M. Exploring catecholase activity in dinuclear Mn(II) and Cu(II) complexes: An experimental and theoretical approach. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 7998–8009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomo, R.P.; Rizzarelli, E.; Bresciani-Pahor, N.; Nardin, G. Properties and X-ray crystal structures of copper(II) mixed complexes with thiodiacetate and 2,2'-bipyridyl or 2,2':6'.2''-terpyridyl. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1982, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-Payer, C.; Pivetta, T.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D.; González-Pérez, J.M.; Crisponi, G.; Castiñeiras, A.; Niclós-Gutiérrez, J. Thiodiacetato-copper(II) chelates with or without N-heterocyclic donor ligands: Molecular and/or crystal structures of [Cu(tda)]n, [Cu(tda)(Him)2(H2O)] and [Cu(tda)(5Mphen)]·2H2O (Him = imidazole, 5Mphen = 5-methyl-1,10-phenanthroline). Inorg. Chim. Acta 2005, 358, 1918–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y. HUMPEN. Private communication in CSD, 2015.

- Khullar, S.; Mandal, S.K. Effect of spacer atoms in the dicarboxylate linkers on the formation of coordination architecture. Molecular rectangles vs 1D coordination polymers: Synthesis, crystal structures, vapor/gas adsorption studies, and magnetic properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 6433–6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J. Interpretation of infrared spectra, A practical approach. In Encyclopedia of analytical chemistry; Meyers, R.A. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, 2000; pp. 10815–10837. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, J.P. The interpretation of infrared spectra: Published reference sources. Appied Spectroscopy Reviews, 2006, 31, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, B.J.; Billing, D.E. The Electronic Properties and Stereochemistry of Mono-Nuclear Complexes of the Copper(II) Ion. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1970, 5, 143–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker, APEX3 Software, Bruker AXS Inc. v2018.7-2, Madison, Wisconsin, USA. 2019.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SADABS. Program for Empirical Absorption Correction of Area Detector Data. University of Goettingen, Germany, 1997.

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. 2008, A64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.J.C. International Tables for Crystallography. Vol. C, Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995.

- A. L. Spek. Structure validation in chemical crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. 2009, D65, 148–155. [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016.

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu . J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigend, F. Accurate coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boys, S.F.; Bernardi, F. The calculation of small molecular interactions by the differences of separate total energies. Some procedures with reduced errors. Mol. Phys., 1970, 19, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F.W. J. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 7314–7323. [CrossRef]

- Keith, T.A. AIMAll (Version 13.05.06), TK Gristmill Software, Overland Park, KS, 2013.

- Contreras-García, J.; Johnson, E.R.; Keinan, S.; Chaudret, R.; Piquemal, J.-P.; Beratan, D.N.; Yang, W. NCIPLOT: A program for plotting noncovalent interaction regions, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 2011, 7, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.R.; Keinan, S.; Mori-Sánchez, P.; Contreras-García, J.; Cohen, A.J.; Yang, W. Revealing Noncovalent Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6498–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emamian, S.; Lu, T.; Kruse, H.; Emamian, H. Exploring nature and predicting strength of hydrogen bonds: A correlation analysis between atoms-in-molecules descriptors, binding energies, and energy components of symmetry-adapted perturbation theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2019, 40, 2868–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Empirical formula | C11H19CuN5O8S |

| Formula weight | 444.91 |

| Temperature | 298(2) K |

| Wavelength | 1.54178 Å |

| Crystal system, space group | Triclinic, |

| Unit cell dimensions | a = 5.3908(3) Å |

| b = 12.9325(7) Å | |

| c = 13.4804(7) Å | |

| α = 62.939(3)° | |

| = 86.260(3)° | |

| γ = 81.195(4)° | |

| Volume | 827.05(8) Å3 |

| Z, Calculated density | 2, 1.787 Mg/m3 |

| Reflections collected / unique | 10657 / 2881 |

| Data / parameters | 2881 / 238 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.132 |

| Final R indices [I>2σ(I)] |

R1 = 0.0415, wR2 = 0.1173 |

| R indices (all data) |

R1 = 0.0447, wR2 = 0.1198 |

| Largest diff. peak and hole | 0.323 and −0.452 e.Å−3 |

| CCDC number | 2267019 |

| Cu(1)-O(4) | 1.933(2) |

| Cu(1)-O(1) | 1.962(2) |

| Cu(1)-N(21) | 2.025(2) |

| Cu(1)-O(8) | 2.262(2) |

| Cu(1)-S(1) | 2.3625(8) |

| Cu(1)-O2a | 3.060(4) |

| O(4)-Cu(1)-O(1) | 175.04(10) |

| N(21)-Cu(1)-S(1) | 173.58(7) |

| Step or R | Temp. (°C) | Time (min) | Weight (%)Exp. Cal. | Evolved gases or residue (R) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ~50-155 | 2-13 | 8.911 | 8.098 | 2 H2O*, CO2 (t*) |

| 2 | 155-220 | 13-20 | 6.387 | 4.049 | 1 H2O, CO2 |

| 3 | 220-440 | 20-43 | 34.784 | - | CO2, H2O, SCNH(t), N2O (t*), |

| 4 | 440-700 | 43-42 | 14.307 | - | CO2, H2O, CO, SCNH,N2O, NO, NO2 |

| 5 | 700-950 | 42-67 | 29.077 | - | CO2, H2O, CO, N2O, NO, NO2 |

| R | 950 | 95 | 19.532 | 17.879 | CuO |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).