1. Introduction

Haemophilus influenzae is one of causative agent of invasive bacterial pathogen that affects both children and adults [

1]

. It was once the main cause of meningitis and other diseases of respiratory systems, but because of extremely efficient conjugate vaccine, the frequency of meningitis brought this bacterium has significantly decreased. It continues to be a significant contributor to childhood sepsis, otitis media, sinusitis, conjunctivitis, and other upper respiratory tract infections. Adults who have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are particularly at risk for pneumonia because of invasive

Haemophilus influenzae diseases [

1,

2].

Haemophilus influenzae is pleomorphic gram-negative coccobacillus and frequently seen in the upper respiratory tract. Known to inhabit the nasopharynx and oropharynx of healthy people, it is a pathogen that only affects humans and can cause severe invasive illness [

3,

4].They are restricted human pathogens that include H. influenzae strains classified encapsulated (a-f) and unencapsulated or non-typeable (NTHi). The genetically varied NTHi strain can invade the nasopharynx and cause local mucosal infections, while encapsulated serotypes can also result in invasive illness [

5,

6].

In contrast, non-type b H. influenzae typically causes opportunistic infections. Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) caused >80% of invasive infections, mostly in healthy children under the age of five. NTHi generates a significant amount of H. influenza infections despite the fact that Hib strains are thought to be the more harmful since it also causes a significant amount of noninvasive infections including otitis media and sinusitis [

4,

5,

7,

8].

Presently, NTHi is the primary cause of invasive H. influenzae disease in the EU/EEA and other parts of the world. The extra growth factors X factor (hemin) and V factor (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) are required for the fastidious Gram-negative coccobacilli Haemophilus species, maybe in combination. Only humans carry H. influenzae, which colonizes their noses, throats, and, to a lesser extent, their conjunctivae and genital tracts [

9].

The World Health Organization lists H. influenzae as one of its top 12 priority pathogens because of its potential to spread serious invasive, fatal diseases. In Ontario and other places with vaccination programs, the prevalence of H. influenzae serotype b (Hib) infection is extremely low. But there is still a lack of knowledge regarding the epidemiology of non-Hib serotypes and nontypeable H. influenzae [

10].

For this review. The most recent studies on the serotype epidemiology, pathobiology, molecular features, and immunology of the invasive H. influenzae disease have been assembled from all around the world. It also covers preventative measures, infection control methods, and risk factors for invasive infections.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

Since there aren't many articles before 2000, we restricted the publication period and examined invasive Haemophilus influenzae illness between 01, March 2000 to 01, March 2023. This systematic review was conducted using English databases, such as PubMed and Google Scholar, in order to fully extract all pertinent articles published worldwide.

The search method used exposure keywords like "Invasive Haemophilus", "Invasive Bacteria", "Haemophilus influenzae molecular character", "Hi genetic character", "Hi virulence factor", and "Hi Epidemiology" and result keywords like "Invasive Haemophilus Influenza", and "Hi pathogenesis".

Due to the numerous studies on these topics, we also included "Hi Immune response", "Hi Serotype OR", and "Hi Invasive strains" to our list of exposure terms. The references that matched the eligibility requirements were also read together with the full text.

2.2. Selection Criteria

We only considered empirical research with full-text available that was published in peer-reviewed journals; we excluded dissertations, conference proceedings, reviews, and commentary papers.

All publications were searched, but case reports, studies evaluating vaccines, non-human studies, and veterinary studies were excluded. The scope of our study was broadened to include the entire world because there hasn't been enough research on the burden of disease in every country. Haemophilus influenzae genetic characteristics, immune response, molecular characteristics and epidemiological studies were all reviewed, and laboratory studies on bacteria used in weak clinical evidence, vaccine trials conducted on specific patient’s immunity, population or genes that were only studied in vitro and without strong scientific support were excluded.

. In order to provide a thorough summary of the research progress, we reviewed all studies of invasive H. influenzae disease, including global epidemiology, immune responses, and pathobiology, molecular and genetic character, which also discuss risk factors for invasive infection, prevention and control measures, and the need for further research or methodological gaps. A careful and relevant assessment of current global epidemiology of invasive H. influenzae infections in several parts of the world is also provided in this paper.

2.3. Study Selection Process

The Endnote version 20 reference management system was used to import and then eliminate duplicate entries for literature that was exclusively acquired from English-language databases.

The initial title screening was followed by an abstract screening to identify all retrieved studies. The whole text was examined for eligibility if the information in titles or abstracts was insufficient to determine whether to include or exclude a study we also looked through each paper's references to see whether there were any other research that our database searches might have overlooked.

Figure 1 depicts the selection process for the study.

3. Global Epidemiology of Invasive H. Influenzae Disease

Before vaccinations were developed, the combined yearly average incidence of invasive Hib disease in children under the age of five was 40% for Asia, 41% for Europe, 60% for Latin America, and 88% for the United States [

11].Due to the sporadic nature of the disease and the absence of global monitoring programmes that are systematic and thorough, the data on the global epidemiology of invasive

Haemophilus Influenzae disease are insufficient.

Haemophilus Influenzae disease infection is present in specific geographic regions and people, according to the examination of published studies on invasive Hia disease and Hia carriage. Currently, locations with a disproportionately high proportion of indigenous peoples, such as the North American Arctic, the Southwest of the United States, and northern and western Canada, have the greatest incidence rates of invasive Hia disease [

8,

12].

A considerable reduction in the prevalence of Hib disease has been observed everywhere the immunization has been used. In children under the age of five, Hib was estimated to have caused around 8.13 million cases of serious illness and 371,000 mortality annually. Between 2000 and 2015, there were 340,000 cases of Hib meningitis, pneumonia, and no pneumonic bacteremia in children under the age of five, with 29,800 deaths globally. Hib deaths decreased by 90% between 2000 and 2015.India was responsible for the majority of Hib-related mortality with 15,600 fatalities.3600 individuals were murdered in Nigeria.3400 people died in China, while 1000 died in South Sudan[

11].

Currently, only a small number of countries where Hib vaccination is either not freely available or is not available at all bear the burden of invasive Hib disease. High immunization rates and efficient surveillance programs for Hib disease are crucial for preventing the spread of invasive Hib disease[

8].However, concerns were raised that other capsulated serotypes of H. influenzae might take over the ecological niche that Hib once occupied and develop into significant sources of invasive disease after the Hib vaccine was introduced. The highest incidence rates of invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease have recently been discovered in various nations, including North America, Canada, and parts of Europe. The epidemiology of invasive

H. influenzae disease due to Hib strain has significantly changed since the Hib conjugate vaccine was launched more than 20 years ago[

13].

Native Americans in North America, Arctic Inuit and Eskimo, and Aboriginal Australians. Studies on population-based surveillance show that there are between 40 and 100 cases of invasive Hib illness per 100,000 children under the age of five in the USA. The annual incidence of H. influenzae meningitis was eight times greater among White Mountain Apache youngsters than in the US population as a whole. In Alaska, Eskimo children had an invasive Hib illness incidence that was 5.5 times greater than that of non-Native children. Although Hib was the predominant H. influenzae serotype that caused invasive disease globally, Hia was responsible for a number of cases in populations including White Mountain Apache Indians, Australian Aboriginals, and Papua New Guineans. More than 70% of instances of invasive H. influenzae illness are currently caused by NTHi [

14,

15].

Although invasive Hib diseases have significantly decreased as a result of the routine use of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) conjugate vaccines, H. influenzae remains a significant cause of invasive disease, primarily sustained by non-vaccine preventable strains[

16].

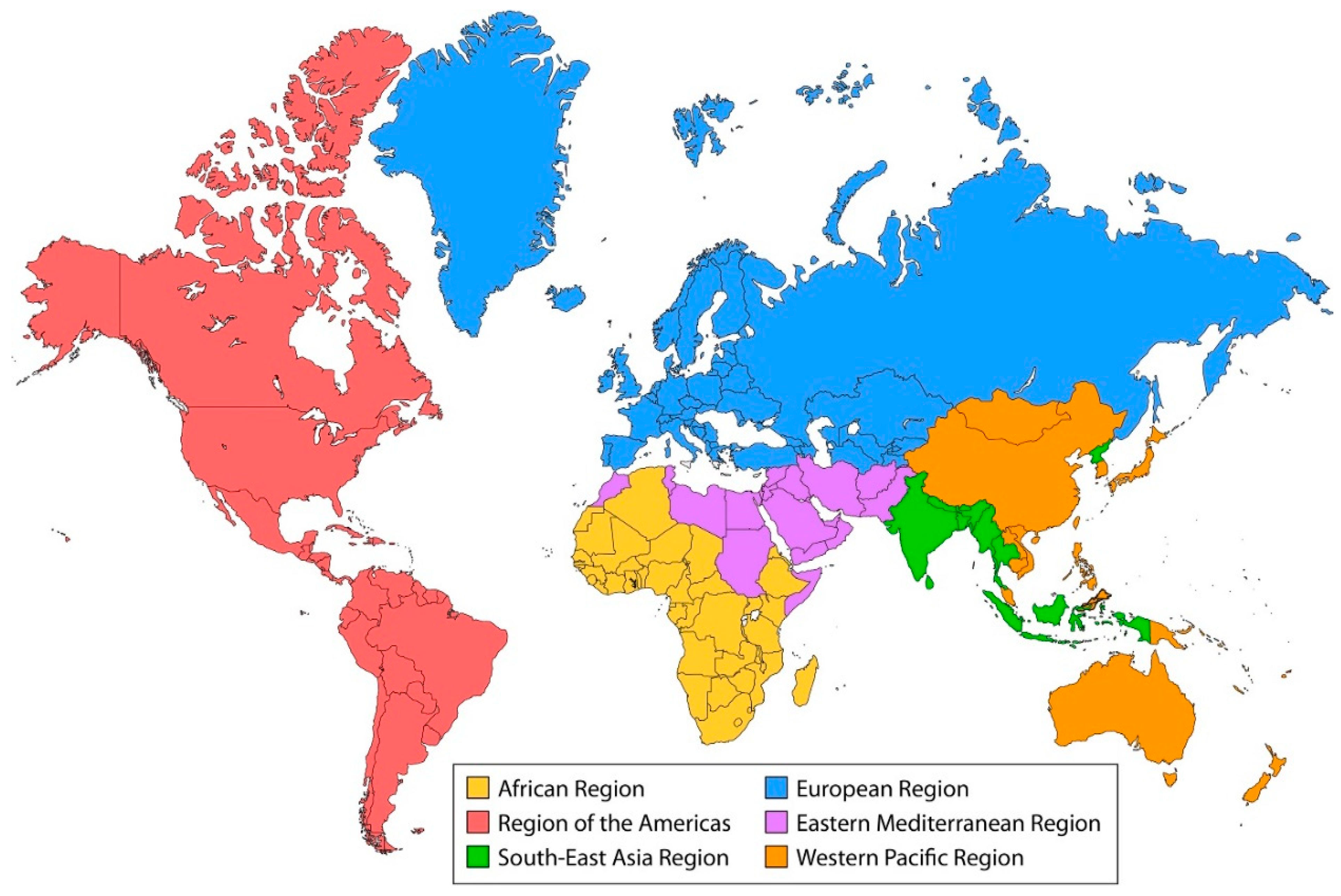

Figure 2.

Hib Vaccination coverage by WHO. Definition of regional groupings 2021 [

16,

17].

Figure 2.

Hib Vaccination coverage by WHO. Definition of regional groupings 2021 [

16,

17].

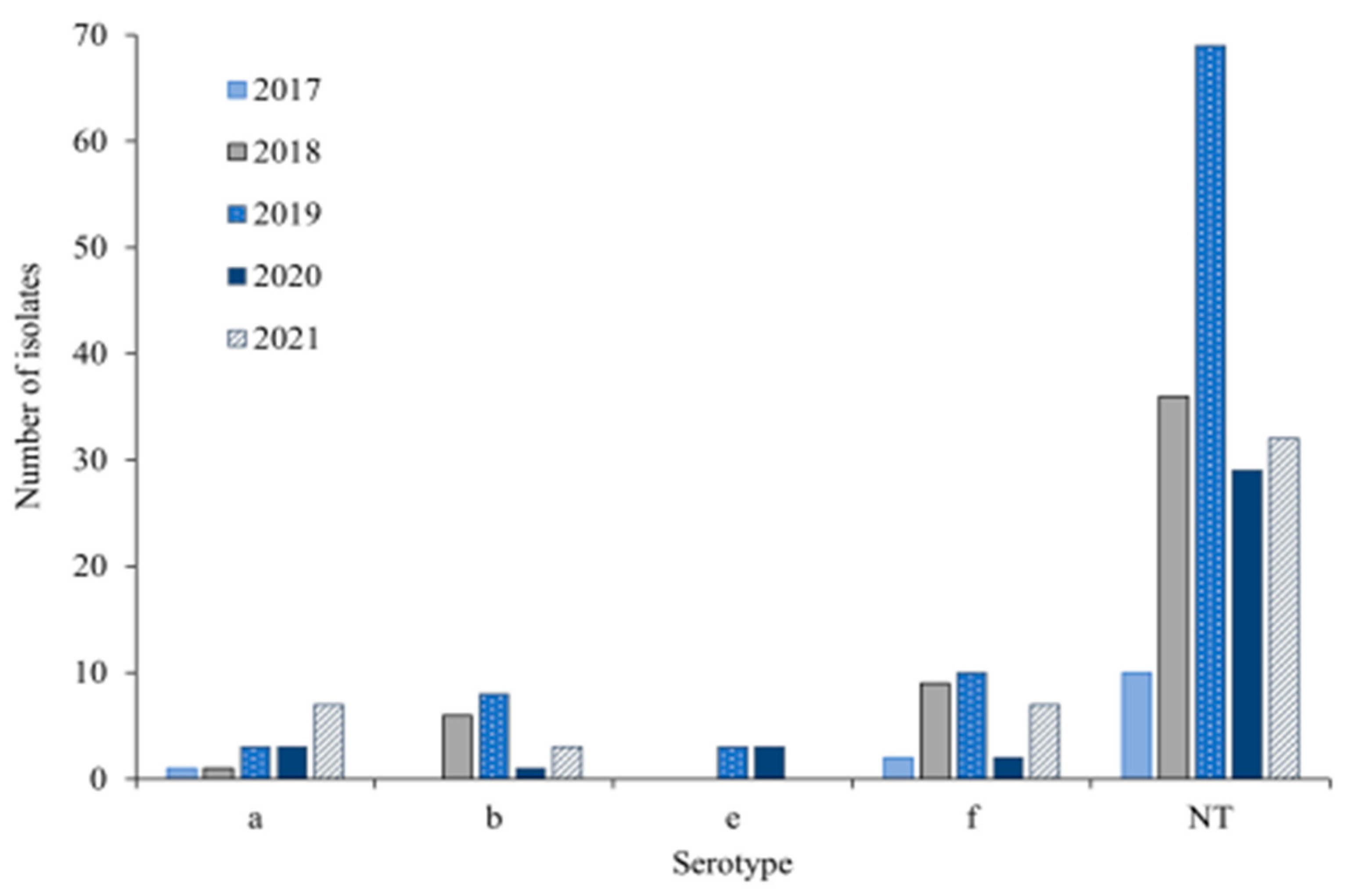

Figure 3.

Number of Hi Serotypes per year in 245 invasive Haemophilus influenzae isolates from Norway from 2017-2021 [

18,

19].

Figure 3.

Number of Hi Serotypes per year in 245 invasive Haemophilus influenzae isolates from Norway from 2017-2021 [

18,

19].

The Hib vaccination has been introduced in all of the nations in the WHO Region of the Americas. In 2020, 85% of people have received the recommended three doses of the Hib vaccine. The recurrence of invasive Hi illness from 14 different countries. Of these isolates, 44% were caused by NTHi, 28% by Hib, and 7.9% by other capsulated serotypes[

11,

20].

Between 2016 and 2018, Finland experienced 231 cases of invasive H. influenzae infection, with an annual frequency of 1.3 to 1.6/100,000 persons. The majority of the cases (79.2%) were NTHi, followed by Hif (12.6%), Hib (3.5%), and Hie (3.0%). Risky adults were those between the ages of 27 and 79. Invasive H. influenzae disease has an annual incidence of 0.28 per 100,000 people in Italy from 2017 to 2018, with a rate of 0.77 per 100,000 for children under the age of 5 (118). NTHi was responsible for the majority of instances (76.1%), whereas Hib and Hif each contributed 11.5% brought on by non-type b strains that have been observed in other parts of Europe, North America, and Australia [

11,

21].

3.1. European Region (Euro)

Nearly every country in the WHO European Region has included the Hib vaccine in their suggested NIPs.Between 2007 and 2014, 12 European nations reported 10, 624 cases of invasive

H. influenzae infection. Information on the serotyping of 83% of the isolates was available. A population of 78% NTHi, 9% Hif, 3% Hie, and 9% Hib was present .Serotype information was available for 9,117 (80.5%) of the isolates, of which 10,081 instances of invasive

H. influenzae infection were reported based on data gathered and 4.6% [

11,

22].

From 2011 to 2018, 260 invasive H. influenzae isolates were characterized in Portugal: NTHi 206 (79.2%); Hib, 35 (13.5%); Hif, 8 (3.1%); Hia, 7 (2.7%); and Hie, 4 (1.5%). The NTHi strains were mostly isolated from adults (78.2%), especially those over 65.whereas 56.3% of H. influenzae infections in children were due to NTHi. Most of the capsulated strains causing infection were from preschool-aged children Hib, 7 Hia, 2 Hif, and 1 Hie [

11].

In France, a nation with a high Hib vaccination rate of 98% over the past ten years, the number of invasive Hib cases nearly doubled in 2018 from the previous year's average of 10 (94). At least 10 vaccine failures occurred, and the majority of instances involved children under the age of five. The most prevalent serotype in France was serotype f, while invasive isolates also contained serotypes b and a. A capsule switching event between serotypes B and C was suggested by WGS analysis. There was significant heterogeneity in non-typeable isolates. According to reports, this area's hib vaccine failed [

11].

There were invasive Hib diseases in both Eastern Europe and Central Asia, but the data on their incidence are scarce.

3.2. African Region (AFR)

In 2018, 327 cases of invasive H. influenzae infection were found by the South African monitoring programme (GERMS), of which 201 produced isolates for typing. 64% were NTHi, while 17% were Hib. Other capsulated serotypes made up 12% of the total. Hib isolates were In contrast to NTHi isolates, Hib isolates were more likely to come from meningitis cases. Children under the age of five had the highest prevalence of invasive H. influenzae infections (of all types), with adults between the ages of 25 and 44 seeing a second peak. The incidence of NTHi peaked in people over 65 years old, with babies experiencing the highest rates [

11].

The monitoring in Eastern Gambia found 57 cases of invasive H. influenzae infection, of which 42% were Hib, 30% NTHi, 18% Hia, 2 were Hic, Hid, Hie, or Hif, 2 failed to grow on cultures, and 2 were unrecoverable. While NTHi mainly manifested as bacteremia pneumonia, 14 of the Hib infections (58% of them) were cases of meningitis. NTHi has become a substantial cause of meningitis in Côte d'Ivoire, according to Boni-Cisse et al., which is interesting. The WHO African Region's 47 member nations have all adopted Hib conjugate vaccines into their national immunization programmes (NIPs), and the average three-dose Hib coverage was 73% on average, with significant regional variation[

19,

23].

Ethiopia introduced the NIP against Haemophilus influenzae and made the Hib conjugate vaccine accessible in 2007. In 2019, Ethiopia has a 68% hib3 coverage rate. The Hib immunization rate in Ethiopia was 50% in 2008.Children's meningitis and pneumonia are most frequently brought on by Hib in Ethiopia. The Ministry of Health (MoH) of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia has been working to provide these immunizations to Ethiopian children with cooperation from the WHO Country Office [

11,

24].

Haemophilus influenzae strain can cause Meningitis which is a major public health problem

All over the world. The highest burden of meningitis disease is seen in a region of sub-Saharan Africa, known as the African Meningitis Belt, especially recognised to be at high risk of epidemics of meningococcal but also pneumococcal meningitis [

25].

In this region, particularly Ethiopia, there is not enough of research associated with other H. influenzae encapsulated non-serotype b and NTHi strains. It is unknown how prevalent Hi disease is in Asia and Africa. Many African nations that have no comprehensive studies of invasive H influenzae illness or serotype data.

3.3. Region of the Americas (AMR)

In this region, the prevalence of invasive H. influenzae is rising. All serotypes and nontypeable H. influenzae should be evaluated for incidence and antibiotic susceptibility. Hib vaccination has been introduced in all countries in the WHO Americas Region. In 2020, three doses of Hib vaccination provided 85% coverage. Invasive Hib disease incidence rates were much higher in Navajo, White Mountain Apache, and Alaska Native children. Among American Indian and Alaska Native youngsters, the prevalence of Hia disease has grown [

11,

26].

Infections with Hia have also been reported in a number of Caribbean and South American nations, including Columbia, Venezuela, Argentina, and Cuba, with the majority of cases coming from Brazil. Salvador, Brazil, reported a rise in cases of Hia meningitis in children under the age of five during the first year of routine Hib immunization, although this does not seem to have persisted over the course of the following years. Following the implementation of the Hib vaccination in Paraguay, invasive Hib infections in children under the age of five decreased, but there was a corresponding rise in invasive NTHi infections in older children and adults. Other H. influenzae serotypes or NTHi have little information available [

11].

Invasive non-Hib illness has become more common over time; NTHi, Hif, and Hia are developing pathogens in this region. H.influenzae type a (Hia) has emerged as a serious source of severe invasive disease in Indigenous communities in North America. [

8].

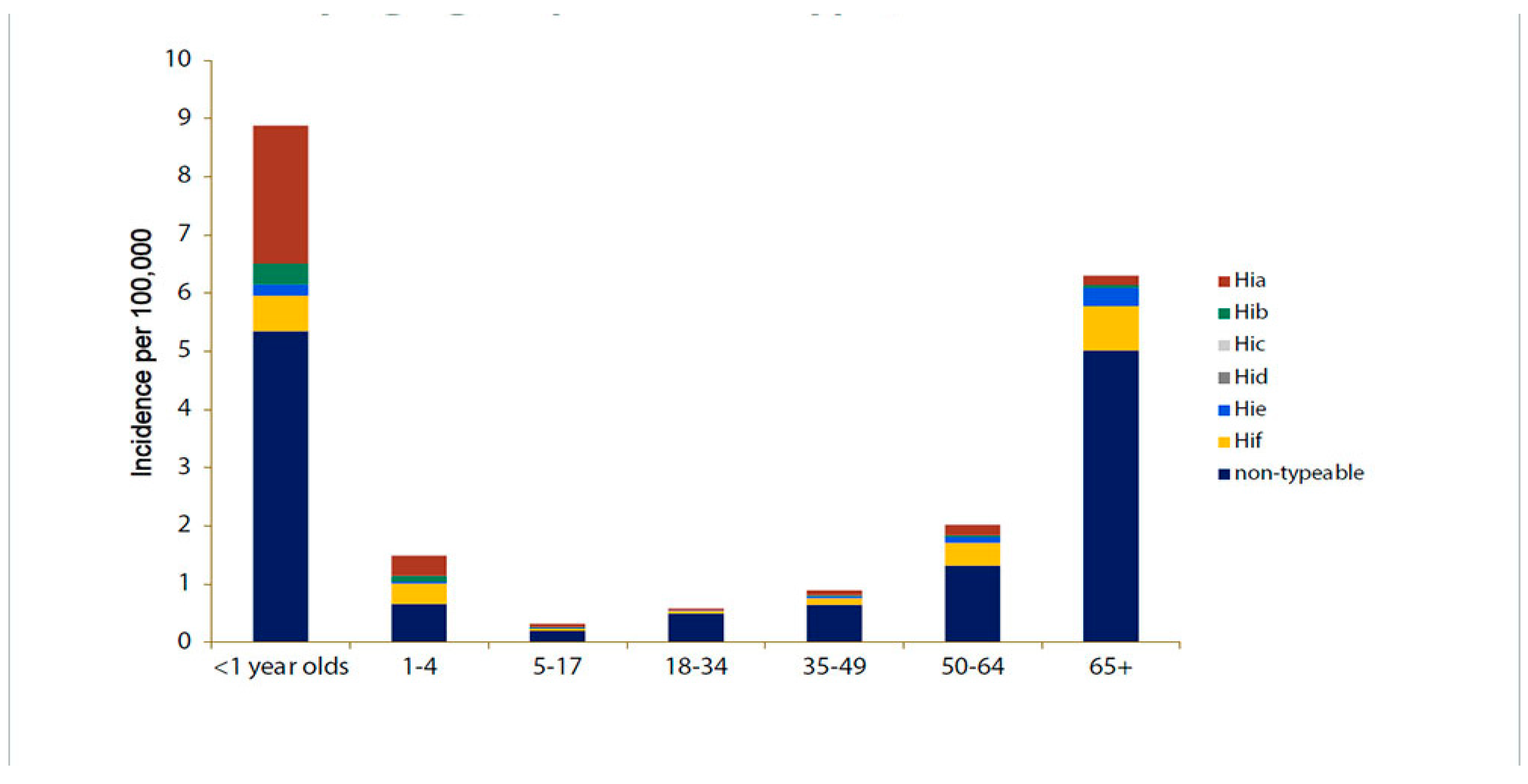

Figure 4.

Depicts the estimated incidence rates (per 100,000 people) of invasive H. influenzae illness by serotype and age in the United States from 2016 to 2020 [

27].

Figure 4.

Depicts the estimated incidence rates (per 100,000 people) of invasive H. influenzae illness by serotype and age in the United States from 2016 to 2020 [

27].

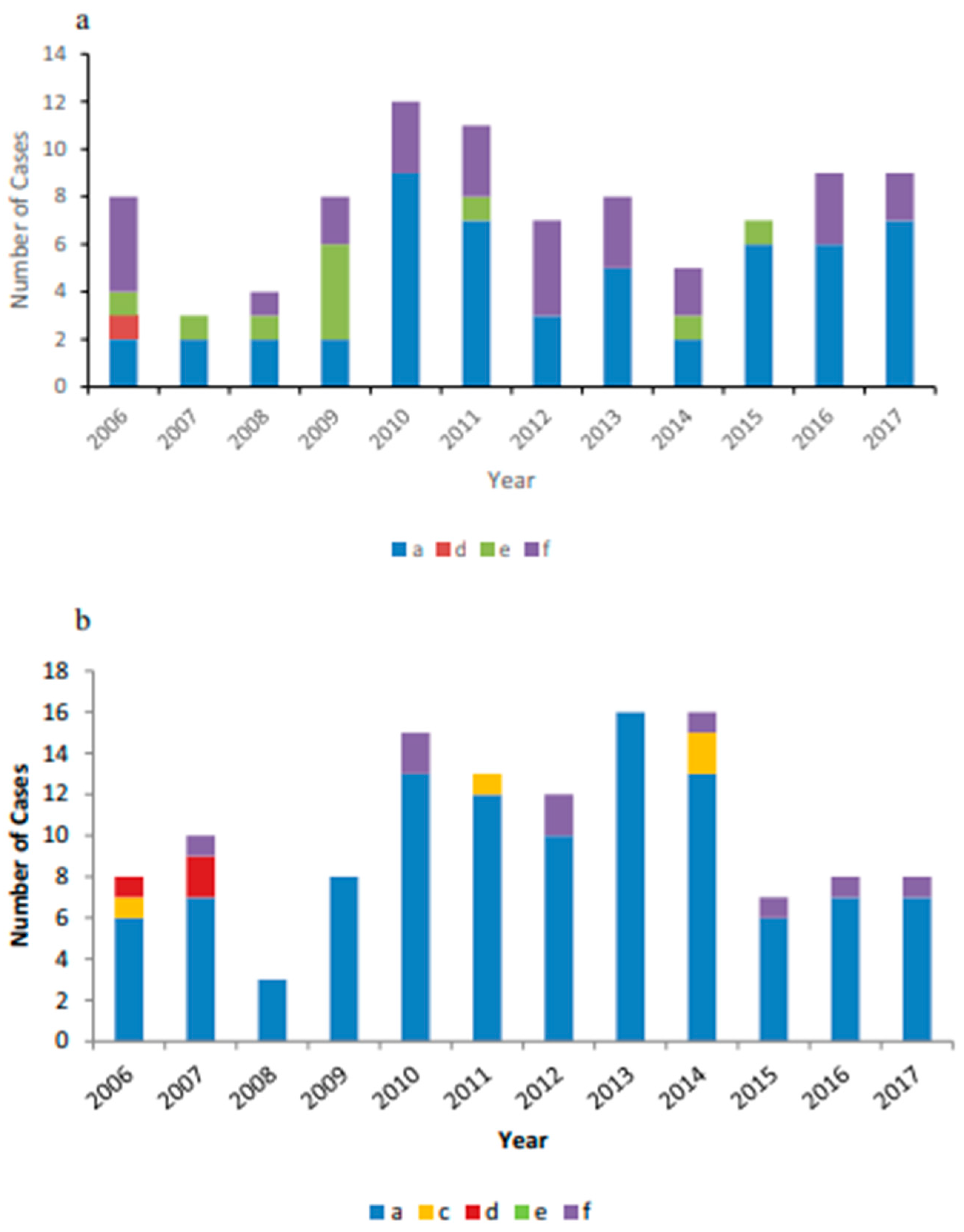

Figure 5.

(a) Invasive non-b encapsulated Hi disease cases reported in Alaska from 2006 to 2017 by serotype. (b) Invasive non-B encapsulated Hi disease cases reported in Northern Canada from 2006 to 2017 by serotype[

3].

Figure 5.

(a) Invasive non-b encapsulated Hi disease cases reported in Alaska from 2006 to 2017 by serotype. (b) Invasive non-B encapsulated Hi disease cases reported in Northern Canada from 2006 to 2017 by serotype[

3].

3.4. South-East Asian Region (SEAR)

After 2009, Hib vaccination was made available throughout the WHO South East Asia Region. Thailand was an exception, as the Hib vaccine was accessible on the private market since the late 1990s despite being included to the NIP in 2019 as a 3-dose primary course without a booster dose. Although rates vary greatly between nations, the South East Asian region had an average coverage of 89% for three doses of the Hib vaccine in 2019 .There aren't many reliable data on the invasive cases pneumonia and bacteremia or sepsis in the region, and there are few on the occurrence of invasive illness. In general, little information is available on the effect of Hib vaccine introduction on invasive H. influenzae disease in the WHO South East Asian Region. Invasive Hia disease has not been studied in Asia or Africa. In the majority of Asian and African nations, there are no systematic studies of invasive

H.influenzae illness or serotype data[

11,

28] .

3.5. Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR)

The Hib vaccine has been made available in every nation in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region. The average coverage of three Hib vaccination doses in 2019 was 82%.According to a recent study, there were Hib complaints from Pakistan (45.7), Saudi Arabia (16.9), Qatar (2.24%), Jordan (27%), Egypt (39%) and Jordan (27%).Data about non-serotype b strains of Hi is limited in this area. The advent of NTHi or non-b serotypes of H. influenzae producing invasive illness in this region is currently poorly documented [

11].

3.6. Western Pacific Region (WPR)

Invasive Hib disease is thought to have caused 370,000 cases and 3,800 fatalities in the Western Pacific Region in 2015. Between 2004 and 2017, a retrospective investigation was conducted in a tertiary hospital in Budapest, Hungary, and 34 adult invasive H. influenzae infections were discovered. The majority of cases (62%) began with pneumonia and were caused by NTHi (79%), followed by Hif (11%), Hia (5%), and Hib (5%). A third of the patients had underlying comorbid conditions such cancer, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease and were under 65 years old [

11].

Table 1.

Global Invasive Haemophilus influenzae trends since introduction of serotype b vaccine*.

Table 1.

Global Invasive Haemophilus influenzae trends since introduction of serotype b vaccine*.

| Hi serotype |

WHO Region |

Country |

Year |

Specimen |

Method used |

Changes in

incidence |

Incidence per 100,000*a |

Vaccine |

Ref |

| Hia |

AFRO |

South Africa |

2017 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

2.9 |

No |

[29] |

|

| Gambia |

2013 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Not known |

10 |

No |

[30] |

|

| AMR |

USA |

2015 |

Blood, CSF |

SA or PCR |

Increased |

8.3 |

No |

[11] |

|

| Canada |

2021 |

Blood, CSF |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

8.9 |

No |

[31] |

|

| Brazil |

2000 |

Blood |

Not reported |

Increased |

0.16 |

No |

[11] |

|

| EURO |

Portugal |

2018 |

Blood, |

PCR |

Increased |

2.7 |

No |

[18] |

|

| England |

2018 |

Blood, |

SA or PCR |

Increased |

0.8 |

No |

[18] |

|

| Germany |

2018 |

Blood |

Not reported |

Decreased |

0.5 |

No |

[18] |

|

| Hungary |

2017 |

Blood |

PCR |

Not known |

5 |

No |

[18] |

|

| Italy |

|

Blood |

SA or PCR |

Increased |

0.02 |

No |

[11] |

|

| Ireland |

2009 |

Blood |

SA or PCR |

Increased |

1 |

No |

[11] |

|

| WPR |

Australia |

2015 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

6.4 |

No |

[17] |

|

| Hib |

AFR |

South Africa |

2018 |

Blood |

PCR |

Increased |

17 |

Yes |

[29] |

|

| Gambia |

2013 |

Blood |

PCR |

Increased |

42 |

Yes |

[30] |

|

| AMR |

USA |

2018 |

Blood |

PCR+SA |

Decreased |

0.02 |

Yes |

[11] |

|

| Canada |

2018 |

Blood, |

SA+PCR |

Decreased

|

2.3 |

Yes |

[18] |

|

| EURO |

Portugal |

2018 |

Blood, |

PCR |

Increased |

13.5 |

Yes |

[18] |

|

| England |

2018 |

Blood, |

SA+PCR |

Decreased |

1.2 |

Yes |

[18] |

|

| Finland |

2018 |

Blood,CSF |

Not reported |

Decreased |

3.5 |

Yes |

[18] |

|

| Germany |

2018 |

Blood |

Not reported |

Decreased |

2.4 |

Yes |

[11] |

|

| Italy |

2018 |

Blood |

PCR |

Increased |

11.5 |

Yes |

[11] |

|

| Taiwan |

2002 |

Blood |

SA |

Increased |

20 |

Yes |

[11] |

|

| Hungary |

2017 |

Blood |

Not reported |

Not known |

5 |

Yes |

[11] |

|

| Ireland |

2018 |

Blood |

SA or PCR |

Decreased |

2 |

Yes |

[32] |

|

| EMR |

Saudi Arabia |

2001 |

Blood |

PCR |

Not reported |

40 |

Yes |

[24] |

|

| UAE |

1999 |

Blood |

PCR |

Not reported |

46 |

Yes |

[24] |

|

| SEA |

South Korea |

2001 |

Blood |

PCR |

Not reported |

6.8 |

Yes |

[24] |

|

| Philippine |

2000 |

Blood |

PCR |

Increased |

95 |

Yes |

[24] |

|

| Japan |

2007 |

Blood |

SA or PCR |

Increased |

4.3 |

Yes |

[24] |

|

| Singapore |

2007 |

Blood |

PCR |

Decreased |

4.4 |

Yes |

[24] |

|

| Taiwan |

2000 |

Blood |

PCR |

Decreased |

3.2 |

Yes |

[24] |

|

| Indonesia |

2005 |

Blood |

PCR |

Increased |

67 |

Yes |

[24] |

|

| WPR |

Australia |

2013 |

Blood, CSF |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

14.9 |

Yes |

[26] |

|

| China |

2015 |

Blood |

SA or PCR |

Increased |

74 |

Yes |

[11] |

|

| Hong Kong |

2015 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

2.7 |

Yes |

[11] |

|

| Mongolia |

2008 |

Blood |

PCR or SA |

Decreased |

2 |

Yes |

[11] |

|

| Hic |

AFR |

South Africa |

2017 |

Blood |

PCR or SA |

Not reported |

1.13 |

No |

[29] |

|

| Gambia |

2013 |

Blood |

PCR or SA |

Not reported |

2 |

No |

[30] |

|

| Hid |

AFR |

South Africa |

2017 |

Blood |

PCR or SA |

Not reported |

0.31 |

No |

[29] |

|

| Gambia |

2017 |

Blood |

PCR or SA |

Not reported |

2 |

No |

[30] |

|

| AMR |

Canada |

2018 |

Blood,CSF |

SA+PCR |

Not reported |

0.1 |

No |

[18] |

|

| Hif |

AFR |

South Africa |

2017 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Not reported |

3.2 |

No |

[29] |

|

| Gambia |

2013 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Not reported |

2 |

No |

[30] |

|

| AMR |

Canada |

2018 |

Blood, |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

10.2 |

No |

[18] |

|

| WPR |

Australia |

2013 |

Blood, CSF |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

10.6 |

No |

[18] |

|

| EURO |

England |

2018 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

8.3 |

No |

[18] |

|

| Germany |

2018 |

Blood |

Not reported |

decreased |

9.8 |

No |

[11] |

|

| Finland |

2018 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

12.6 |

No |

[18] |

|

| Portugal |

2018 |

Blood, |

PCR |

Increased |

3.1 |

No |

[18] |

|

| Italy |

2018 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

4.6 |

No |

[11] |

|

| Ireland |

2018 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

7 |

No |

[32] |

|

| Sweden |

2009 |

Blood,CSF |

PCR |

Increased |

57 |

No |

[74] |

|

| Hie |

AFR |

South Africa |

2017 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increase |

0.31 |

No |

[29] |

|

| Gambia |

2013 |

Blood |

Blood,CSF |

Not known |

2 |

No |

[30] |

|

| WPR |

Australia |

2013 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

14.9 |

No |

[18] |

|

| EURO |

Germany |

2018 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Not reported |

2.4 |

No |

[11] |

|

| Portugal |

2018 |

Blood,CSF |

PCR |

Increased |

79.2 |

No |

[18] |

|

| Portugal |

2018 |

Blood,CSF |

PCR |

Increased |

1.5 |

No |

[18] |

|

| |

Ireland |

2018 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

6 |

No |

[32] |

|

| NTHi |

AFR |

Gambia |

2013 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Not known |

30 |

No |

[30] |

|

| South Africa |

2017 |

Blood |

Not reported |

Increased |

64 |

No |

[29] |

|

| AMR |

Canada |

2018 |

Blood, |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

74.2 |

No |

[18] |

|

| USA |

2023 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

92 |

No |

[33] |

|

| SEA |

Taiwan |

2002 |

Blood |

SA |

Not Known |

80 |

No |

[27] |

|

| EURO |

Italy |

2018 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

76.1 |

No |

[18] |

|

| Germany |

2018 |

Blood |

Not reported |

Increased |

84.5 |

No |

[18] |

|

| Hungary |

2018 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

79 |

No |

[11] |

|

| Portugal |

2018 |

Blood |

PCR |

Increased |

79.2 |

No |

[18] |

|

| Finland |

2018 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

79 |

No |

[18] |

|

| Ireland |

2018 |

Blood |

SA+PCR |

Increased |

83 |

No |

[32] |

|

| Sweden |

2009 |

Blood |

PCR |

Increased |

71 |

No |

[11] |

|

Spain

|

2013 |

Blood |

SA |

Increased |

85 |

No |

[27] |

|

| Slovenia |

2008 |

Blood |

PCR |

Increased |

85 |

No

|

[27] |

|

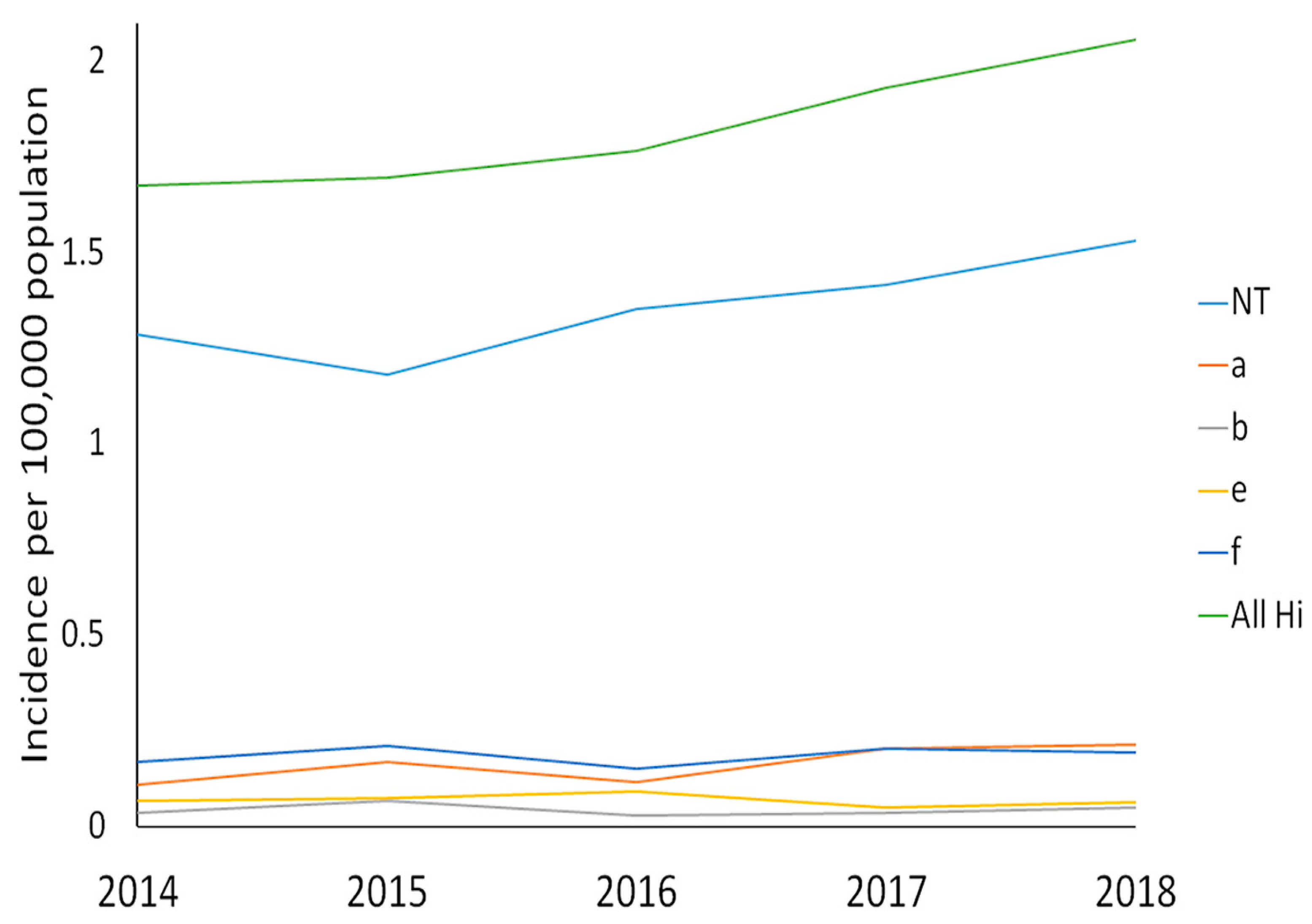

Figure 6.

Incidence of invasive H. influenzae disease, showing single infection episodes by serotype in Ontario, 2014 to 2018 [

18].* (N = 1,338).

Figure 6.

Incidence of invasive H. influenzae disease, showing single infection episodes by serotype in Ontario, 2014 to 2018 [

18].* (N = 1,338).

Figure 6.

: Number of cases of invasive Haemophilus influenzae infection, by serotype, reported to National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD), South Africa, 2006 to 2018[

34] .

Figure 6.

: Number of cases of invasive Haemophilus influenzae infection, by serotype, reported to National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD), South Africa, 2006 to 2018[

34] .

4. Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis of

H. influenzae involves its antiphagocytic capsule and endotoxin; no exotoxin is produced. Most infections occur in children between the ages of 6 months and 6 years, with a peak in the age group from 6 months to 1 year. H. influenzae adheres to the host cells and manifests its pathogenicity using a number of different methods. Proteins like protein H and Haemophilus surface fibrils are used by encapsulated H. influenzae; however, NTHi subtypes lack these characteristics. Without an anti-capsular antibody, bacteria proliferate more because the capsule gives them antiphagocytic characteristics [

1,

14].

As a result, research into the mechanisms of host-pathogen interaction in NTHi patients is still underway. Through a variety of host proteins, including invasion of specific serum factors and direct attachment to surface epithelial cells that allows access to the extracellular matrix layer, NTHi exerts its final effect. These binding mechanisms support NTHi's ability to mediate colonization, maintain a strong adhesion, and facilitate simple entry into the host cells. They avoid and alter host complement and immune system responses through comparable interactions, and they also assist in the emergence of a colony that resembles a biofilm .The 42kDa surface lipoprotein Protein D (PD), which is highly conserved, is present in all Haemophilus influenzae, including nontypeable (NT) H. influenzae. It has been demonstrated that PD affects ciliary function in a human nasopharyngeal tissue culture model and increases the ability to generate otitis media in rats as part of the pathophysiology of respiratory tract infections [

14,

35].

Due to its glycerol-phosphodiesterase activity, which causes host epithelial cells to produce phosphorylcholine, PD is likely a virulence factor. A promising vaccination candidate against an experimental NT H. influenzae infection has been found to be PD. After middle ear and lung bacterial challenges, rats given the PD vaccine cleared the NT H. influenzae more effectively, and chinchillas given the PD vaccine displayed notable NT H. influenzae resistance [35-37].There are several mechanisms through which H. influenzae adhere to the host cells and exhibit virulence. Encapsulated H. influenzae uses proteins such as protein H and Haemophilus surface fibrils (Hsf), but these features are not present in NTHi subtypes. The capsule confers antiphagocytic properties to the bacteria, and the lack of anti-capsular antibody causes increased bacterial proliferation. NTHi has been widely causing infections after the advent of specific vaccines for capsular H.influenzae [

20,

35].

There is ongoing research to investigate the mechanisms of host-pathogen interaction in cases of NTHi. NTHi exerts its final effect through an array of host proteins, both via direct attachment to the surface epithelial cells and accessing the underlying extracellular matrix layer, and also through invading certain serum factors. These binding mechanisms allow NTHi to maintain strong adhesion, mediate colonization, and favors easy entry into the host cells. Through similar interactions, they evade and modify the host complement and immune system responses, and also help in developing a biofilm-like colony [

20].

Otitis media with acute influenzae. In a child-focused clinical experiment, PD was utilized as an antigenically active carrier protein in an 11-valent pneumococcal conjugate investigational vaccine, and substantial protection was attained against both pneumococcal and NT H. influenzae-induced acute otitis media. Given that PD is the first NT H. influenzae antigen to trigger protective responses in humans, this may have significant clinical consequences [

35,

37].

5. Genomic and molecular Characteristics

The genomic study found that a variety of multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and core genome-single nucleotide polymorphisms (core-SNP)-based studies, carried out on various H. influenza strain sets encompassing capsulated and non-typeable species, commonly share that capsulated strains concentrate into a small number of serotype-specific clusters or clonal populations while NTHi strains display great genomic diversity [

16].

In the capsule locus, Regions I (containing the bexABCD operon) and III (containing the hcsA and hcsB genes), which are involved in exporting the capsule polysaccharide, are shared by all six capsular serotypes, whereas Region II genes, which are necessary for polysaccharide synthesis, are specific to each serotype. The creation of bioinformatics tools for rapid in silico detection of H. influenzae serotypes using WGS data during the transition to whole genome sequencing (WGS)-based monitoring is particularly significant [

23].

Additionally, the genetic similarity of invasive H. influenzae type f (Hif) and type a (Hia) isolates from capsuled strains has been demonstrated. The presence of the sap2 operon, aef3 fimbriae, and genes for kanamycin nucleotidyl transferase, iron-utilization, and putative YadA-like trimeric autotransporters and the absence of an operon for de novo histidine biosynthesis, a hmg locus for lipooligosaccharide (LOS) biosynthesis and biofilm formation may increase the virulence of Hif [

23].

Genomic study showed that NTHi had more genetic diversity than typeable Hi. The WGS serotyping method can be used as an alternative to Hi serotyping because it successfully predicted the type of Hi capsule. Six serotypes of Typeable Hi (a through f) are present, each of which expresses a different capsular polysaccharide. One of typeable Hi's main virulence factors is the capsule, which is encoded by the genes in the capsule locus. Non-typeable (NTHi) is associated to both invasive and non-invasive illnesses and does not express capsule [

38].

The unstoppable -omics technologies have advanced significantly since the genome of the H. influenzae RdKW20 strain was sequenced. Being a pathogen that has adapted to humans, integrative systems biology approaches to the interactions between H. influenzae and the human airways are essential in identifying specific bacterial recognition, host signal transduction, or immune tolerance, along with multi-omics approaches to elucidate the genetic, immunologic, (post)transcriptional, (post)translational, and metabolic mechanisms underlying the outcome of such interactions[

19].

The majority of immune cells in the MEF were neutrophils, and flow cytometry analysis revealed that NTHi infection greatly boosted their proportion while decreasing the proportions of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. In the blood and spleen after NTHi infection, neutrophil and macrophage counts rose. By using techniques for bacterial single-cell resolution, such as microfluidics, single-cell sorting, microscopy, and genome/RNA sequencing, those methods will be greatly enhanced, allowing them to ignore the remarkable bacterial phenotypic heterogeneity and shed light on complex phenotypes like antibiotic persistence or metabolic specialization [

19,

39].

7. Immune response to H. influenzae

Recent research on the lipooligosaccharide of

H. influenzae has focused on the implications of its structural and compositional features for bacterial virulence; nevertheless, the function of LOS in the activation of innate and adaptive immunity is still poorly known. Since the capsule inhibits complement-mediated bacteriolysis in the absence of an opsonizing antibody, encapsulated strains have a greater capacity to produce invasive illness. The age distribution is among factors that attributed to a decline in maternal IgG in the child coupled with the inability of the child to generate sufficient antibody against the polysaccharide capsular antigen until the age of approximately 2 years[

1,

46,

47], .

Efficacious Hib vaccines have been designed by covalently linking the PRP capsule to a carrier protein that recruits T-cell help for the polysaccharide immune response and induces anti-PRP antibody production even in the first6 months of life

. H.influenzae is a common bacterium that can be discovered in a number of respiratory illnesses. To measure the respiratory immune/inflammatory response to this bacterium, a range of different assays/techniques may be applied. Fluorescence-based technologies like flow cytometry and confocal microscopy enable thorough assessment of biological reactions. It is possible to use a variety of Hi antigens, including live bacteria, cell wall components, and killed or inactivated preparations [

48].

As a result of the immune system activation and high inflammatory reaction caused by NTHi, the lung's ability to remove the bacteria is frequently compromised. Due to this, chronic inflammation and recurrent/persistent infection lead to lung pathology. The lower airways are protected and recurrent infections are avoided by effective mechanisms like mucociliary clearance, coughing, and humoral and cellular immune processes, which are present in about half of the adult population who aspirate some oropharyngeal secretions while lying down in the sleep position. Because of this, silent aspiration is a problem in older people and plays a big role in cases of community-acquired pneumonia [

36].

The alveolar macrophages and conducting airway epithelia are both implicated in sensing and regulating the first response, and TLR4 plays a crucial role in the early host immune response to H. influenzae in the lung. The small variations in cytokine/chemokine expression in the alveolar macrophage between wild-type and mutant mice highlight the involvement of the airway epithelium in regulating the early host response to H. influenzae infection [

49,

50].

Because they do not have functionally active anti-Hib antibodies, adult patients with chronic renal failure who get haemodialysis are more likely to develop invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) illness. For at least a year, these patients are protected against invasive Hib infection by the paediatric Hib polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccination due to its high immunogenicity .The experimental study of the cellular immune response to NTHi infection in the middle ear fluid (MEF) of Junbo mice, a characterized NTHi infection model, showed that NTHi infection increased total cell number and significantly decreased the proportion of live cells at day 1, and that this further decreased gradually on each day up to day 7 [

39,

51].

In uninoculated MEF, T-helper (Th) cells dominated the T-cell population, and on day 2 of NTHi infection, the effector Th (CD44+) cell population increased along with an increase in IL-12p40 levels. T-regulatory (T-reg) cell population increased while effector cell population decreased under sustained NTHi infection for up to 3 days[

39].IgA proteases come in two varieties; type 1 is produced by serotypes a, b, d, and f, while type 2 is produced by serotypes c and e. previously described IgA proteases have been linked to specific serotypes. In addition, H. influenzae has genes that are important for adhesion, iron uptake, immunological evasion, and endotoxins .Neutrophils are the first immune cells to respond to an NTHi infection in the preinflamed ME environment of the Junbo mouse, followed by T-reg immune suppressive cells. These findings suggest that persistent NTHi infection in the ME triggers an immune suppressive response by increasing the population of T-reg cells and decreasing immune cell infiltration, which prolongs infection [

39,

50].

The first Hib vaccine was a PRP simple polysaccharide vaccine. A major field trial in Finland that included 100,000 kids aged 3 months to 5 years showed that responses to PRP varied by age but that transmission was not interrupted since there was no impact on nasopharyngeal carriage. The PRP vaccine was 90% effective in children under the age of 18 months but did not produce protective levels of anti-PRP antibodies. With little isotopes flipping to IgG antibody in babies under the age of 18 months, polysaccharides are T-cell independent antigens that largely elicit IgM responses. When administered repeatedly, simple polysaccharide vaccinations do not trigger immunologic memory or a booster response [

11].

Virulence & Risk factors of invasive Haemophilus influenzae

For some populations, ethnicity is a risk factor. The risk of invasive Hib infections is higher in American Indians, Inuits, black Africans, Melanesians, and African Americans. Whether this is due to truly biological differences or other factors is not clear[

11].

Both

host variables and

exposure factors can increase your risk of getting

Hib illness. Family size, child care utilization, low socioeconomic position, parents with low levels of education, and siblings who are still in school are all exposure factors. Age (young and old ages with elevated risk), race/ethnicity (Native Americans with an elevated risk, possibly complicated by socioeconomic factors associated with both race/ethnicity and Hib disease), and chronic disease (including functional and anatomic asplenia, immunodeficiency virus infection, immunoglobulin deficiency, complement deficiency, and receiving chemotherapy or stem cell transplant) are all host factors. Breastfeeding and passively acquired maternal antibodies (for infants younger than 6 months) are protective factors [

33].

inadequacies in the immune system, including a lack of mannose-binding lectins, infectious flaws in the vaccine or in the way it was administered or stored, maturational delays in immunological responses, and specific, tiny flaws in how the body responded to PRP [

52]. Recently, it was shown that receiving a cochlear implant operation could increase your risk of developing invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease. Age and, more importantly, a lack of vaccination against Hib for non-Hib strains were in some cases risk factors for the development of invasive Hib disease. Household contacts of an invasive Hib case are more likely to contract the illness[

11].

Due to the severe nature of invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease, it is crucial to investigate specific host factors, such as population genetics, patterns of natural immunity against this pathogen, and prevalence in populations with this disease, that may predispose some populations to infection. This type of data will be necessary for the creation of infection preventive and control methods Its capsule, the adhesion proteins, pili, the outer membrane proteins, the IgA1 protease and, last but not least, the lipooligosaccharide, increase the virulence of H. influenzae by participating actively in the host invasion the host by the microrganism. Some of these factors are used in vaccine preparations[

11,

53].

Figure 9.

Multifactorial factors behind emerging invasive H.influenzae Recently.

Figure 9.

Multifactorial factors behind emerging invasive H.influenzae Recently.

9. Conclusion and future directions

Invasive Non-typeable (NTHi) and non-b strains of the Haemophilus influenzae are currently the main causes of the sickness, with small children and the elderly being the most common populations to contract it. Since the illness burden is still greatest in resource-poor countries, immediate action must be taken to guarantee that children living in locations where this vaccine cannot be used owing to financial and logistical restrictions benefit from its benefits [

42,

45].Due to the severe nature of invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease, it is crucial to investigate specific host factors, such as patterns of natural immunity against this pathogen, population genetics, and prevalence in populations with this disease that may predispose some populations to infection[

11].

Due to the sporadic nature of the disease and the absence of global monitoring programmes that are systematic and thorough, the data on the global epidemiology of invasive Haemophilus Influenzae disease are insufficient [

12].

Non-type b strains have been seen causing invasive Hi disease in different regions of Europe, North America, and Australia [

38]. Regarding invasive

Haemophilus influenzae bacterial infections, this review includes the following information’s and knowledge gaps:

Globally, Haemophilus influenzae continues to be a common invasive Bacterial pathogen that dramatically raises morbidity and mortality. However, still little is known about the global presence of this pathogen and its emerging pathogenic strains.

For some populations, ethnicity is a risk factor. The risk of invasive Hib infections is higher in American Indians, Inuits, black Africans, Melanesians, and African Americans. Whether this is due to truly biological differences or other factors is not clear and needs further studies on these populations.

NTHi, Hia, Hif, and Hie cause an increasing number of invasive illnesses, especially in children and elderly people. However, the immune response to non-type b Hi infection is poorly studied.

Even though there is still no vaccine available for strains other than type b (Hib).Immunization is necessary to guard against contracting invasive diseases brought on by nontypeable and other encapsulated strains of H. influenzae.

H. influenzae can infect a person several times and a prior Hib infection could not protect you from a later infection. It is recommended to take the Hib vaccine even if one has already had Hib disease.

The reasons for an increased susceptibility to NTHi, Hia, and Hif and Hie infection among some specific populations groups are still unknown and needs further research.

Since Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae's pathogenicity is significantly rising, international scientific organizations need to raise awareness of the emergence of invasive Hi pathogenicity and characterize the pathobiology of this microorganism.

It is essential to understand the host-pathogen interactions in Hi patients in order to curb the spread of invasive NTHi and other Hi strains. Through a variety of host proteins, including the invasion of certain serum factors and direct adhesion to surface epithelial cells, which disintegrates the extracellular matrix layer.

Finally, this review suggests that an extensive surveillance system that collects information on serotype, genotype, immunological characterization, and vaccination status is required to follow the trends described in this Review and eradicate Haemophilus influenzae illnesses and their global impacts.