Submitted:

08 June 2023

Posted:

12 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Cerebrospinal fluid and neurodegenerative pathology

3. Neural targets, intrathecal access

4. ‘Orthobiologic’ activity in AD/PD

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moutinho, S. The long road to a cure for Alzheimer's disease is paved with failures. Nat Med 2022;28(11):2228-31. [CrossRef]

- Mari Z, Mestre TA. The disease modification conundrum in Parkinson's disease: Failures and hopes. Front Aging Neurosci 2022;14:810860. [CrossRef]

- Dorsey ER, Sherer T, Okun MS, Bloem BR. The emerging evidence of the Parkinson pandemic. J Parkinsons Dis 2018;8:S3–S8. [CrossRef]

- Triaca V, Imbimbo BP, Nisticò R. Editorial: Neurotrophins biodelivery to CNS: Innovative approaches for disease-modifying therapy. Front Neurosci 2022;16:916563. [CrossRef]

- Cummings JL, Goldman DP, Simmons-Stern NR, Ponton E. The costs of developing treatments for Alzheimer's disease: A retrospective exploration. Alzheimers Dement 2022;18(3):469-77. [CrossRef]

- Swift MJ, Greene JA, Welch ZR. Concentration of neurotransmitter and neurotrophic factors in platelet-rich plasma. Blood 2006;108(11):3914. [CrossRef]

- Shen YX, Fan ZH, Zhao JG, Zhang P. The application of platelet-rich plasma may be a novel treatment for central nervous system diseases. Med Hypotheses 2009;73(6):1038-40. [CrossRef]

- Farid MF, Abouelela YS, Yasin NAE, Mousa MR, Ibrahim MA, Prince A, et al. A novel cell-free intrathecal approach with PRP for the treatment of spinal cord multiple sclerosis in cats. Inflamm Regen 2022;42(1):45. [CrossRef]

- U.S. National Library of Medicine/NIH. Clinical trial registry (clinicaltrials.gov) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Neurodegenerative+Diseases&term=intrathecal%3B+platelet-rich+plasma&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=&Search=Search [site accessed 1 June 2023].

- Domínguez-Fernández C, Egiguren-Ortiz J, Razquin J, Gómez-Galán M, De Las Heras-García L, Paredes-Rodríguez E, et al. Review of technological challenges in personalised medicine and early diagnosis of neurodegenerative disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24(4):3321. [CrossRef]

- Lancini E, Haag L, Bartl F, Rühling M, Ashton NJ, Zetterberg H, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and positron-emission tomography biomarkers for noradrenergic dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Commun 2023;5(3):fcad085. [CrossRef]

- Mawuenyega KG, Sigurdson W, Ovod V, Munsell L, Kasten T, Morris JC, et al. Decreased clearance of CNS beta-amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Science 2010;330(6012):1774. [CrossRef]

- Jessen NA, Munk AS, Lundgaard I, Nedergaard M. The glymphatic system: A beginner's guide. Neurochem Res 2015;40(12):2583-99. [CrossRef]

- Tadayon E, Pascual-Leone A, Press D, Santarnecchi E; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Choroid plexus volume is associated with levels of CSF proteins: Relevance for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2020;89:108-17. [CrossRef]

- Sochocka M, Diniz BS, Leszek J. Inflammatory response in the CNS: Friend or foe? Mol Neurobiol 2017;54:8071e8089. [CrossRef]

- Taipa R, das Neves SP, Sousa AL, Fernandes J, Pinto C, Correia AP, et al. Proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the CSF of patients with Alzheimer's disease and their correlation with cognitive decline. Neurobiol Aging 2019;76:125-32. [CrossRef]

- Bulling A, Brucker C, Berg U, Gratzl M, Mayerhofer A. Identification of voltage-activated Na+ and K+ channels in human steroid-secreting ovarian cells. Ann NY Acad Sci 1999;868:77-9. [CrossRef]

- Sassoli C, Garella R, Chellini F, Tani A, Pavan P, Bambi F, et al. Platelet-rich plasma affects gap junctional features in myofibroblasts in vitro via vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A/VEGF receptor. Exp Physiol 2022;107(2):106-21. [CrossRef]

- Ozawa Y, Toda E, Kawashima H, Homma K, Osada H, Nagai N, et al. Aquaporin-4 suppresses neural hyperactivity and synaptic fatigue and finetunes neurotransmission to regulate visual function in the mouse retina. Mol Neurobiol 2019;56(12):8124-35. [CrossRef]

- Haj-Yasein NN, Jensen V, Østby I, Omholt SW, Voipio J, Kaila K, et al. Aquaporin-4 regulates extracellular space volume dynamics during high-frequency synaptic stimulation: A gene deletion study in mouse hippocampus. Glia 2012;60(6):867-74. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Wang X, Liu W, Lu W. Thrombin-activated platelet-rich plasma enhances osteogenic differentiation of human periodontal ligament stem cells by activating SIRT1-mediated autophagy. Eur J Med Res 2021;26(1):105. [CrossRef]

- Sills ES, Rickers NS, Li X, Palermo GD. First data on in vitro fertilization and blastocyst formation after intraovarian injection of calcium gluconate-activated autologous platelet rich plasma. Gynecol Endocrinol 2018;34(9):756-60. [CrossRef]

- Kang JH, Irwin DJ, Chen-Plotkin AS, Siderowf A, Caspell C, Coffey CS, et al. Association of cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid 1-42, T-tau, P-tau181, and α-synuclein levels with clinical features of drug-naive patients with early Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol 2013;70(10):1277-87. [CrossRef]

- Mollenhauer B, Locascio JJ, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Sixel-Döring F, Trenkwalder C, Schlossmacher MG. α-Synuclein and tau concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid of patients presenting with parkinsonism: A cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2011;10(3):230-40. [CrossRef]

- Hall S, Surova Y, Öhrfelt A, Zetterberg H, Lindqvist D, Hansson O. CSF biomarkers and clinical progression of Parkinson disease. Neurology 2015;84(1):57-63. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti S, Bisaglia M. Oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease: The role of dopamine oxidation products. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023;12(4):955. [CrossRef]

- Huang P, Zhang LY, Tan YY, Chen SD. Links between COVID-19 and Parkinson's disease/Alzheimer's disease: Reciprocal impacts, medical care strategies and underlying mechanisms. Transl Neurodegener 2023;12(1):5. [CrossRef]

- Yi X, Manickam DS, Brynskikh A, Kabanov AV. Agile delivery of protein therapeutics to CNS. J Control Release 2014;190:637-63. [CrossRef]

- Xie H, Chung JK, Mascelli MA, McCauley TG. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of a therapeutic enzyme (idursulfase) in cynomolgus monkeys after intrathecal and intravenous administration. PLoS One 2015;10(4):e0122453. [CrossRef]

- Lehrer S, Rheinstein PH. Transspinal delivery of drugs by transdermal patch back-of-neck for Alzheimer's disease: a new route of administration. Discov Med 2019;27(146):37-43. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30721650/.

- Lehrer, S. Nasal NSAIDs for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2014;29(5):401-3. [CrossRef]

- Slavc I, Cohen-Pfeffer JL, Gururangan S, Krauser J, Lim DA, Maldaun M, et al. Best practices for use of intracerebroventricular drug delivery devices. Mol Genet Metab 2018;124(3):184-8. [CrossRef]

- Muschol N, Koehn A, von Cossel K, Okur I, Ezgu F, Harmatz P, et al. A phase I/II study on intracerebroventricular tralesinidase-alfa in patients with Sanfilippo syndrome type B. J Clin Invest 2023;133(2):e165076. [CrossRef]

- Manuel MG, Tamba BI, Leclere M, Mabrouk M, Schreiner TG, Ciobanu R, et al. Intrathecal pseudodelivery of drugs in the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases: Rationale, basis and potential applications. Pharmaceutics 2023;15(3):768. [CrossRef]

- Prineas JW, Parratt JD, Kirwan PD. Fibrosis of the choroid plexus filtration membrane. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2016;75(9):855-67. [CrossRef]

- Hsu SJ, Zhang C, Jeong J, Lee SI, McConnell M, Utsumi T, et al. Enhanced meningeal lymphatic drainage ameliorates neuroinflammation and hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic rats. Gastroenterology 2021;160(4):1315-29.e13. [CrossRef]

- Buccellato FR, D'Anca M, Serpente M, Arighi A, Galimberti D. The role of glymphatic system in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's Disease pathogenesis. Biomedicines 2022;10(9):2261. [CrossRef]

- Nedergaard, M. Neuroscience. Garbage truck of the brain. Science 2013;340(6140):1529-30. [CrossRef]

- Sepehrinezhad A, Stolze Larsen F, Ashayeri Ahmadabad R, Shahbazi A, et al. The glymphatic system may play a vital role in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy: A narrative review. Cells 2023;12(7):979. [CrossRef]

- Seehusen DA, Reeves MM, Fomin DA. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam Physician 2003;68(6):1103-9. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2003/0915/p1103.html.

- Hrishi AP, Sethuraman M. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis and interpretation in neurocritical care for acute neurological conditions. Indian J Crit Care Med 2019;23(Suppl 2):S115-9. [CrossRef]

- Astara K, Pournara C, de Natale ER, Wilson H, Vavougios GD, Lappas AS, et al. A novel conceptual framework for the functionality of the glymphatic system. J Neurophysiol 2023;129(5):1228-36. [CrossRef]

- Epstein NE, Agulnick MA. Perspective: Early direct repair of recurrent postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leaks: No good evidence epidural blood patches work. Surg Neurol Int 2023;14:120. [CrossRef]

- Beckman SP, Proctor C, Toms JB. Management of recurrent post-myelography lumbar pseudomeningocele with epidural blood patch. Cureus 2023;15(2):e35600. [CrossRef]

- Peng W, Achariyar TM, Li B, Liao Y, Mestre H, Hitomi E, et al. Suppression of glymphatic fluid transport in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis 2016;93:215-25. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen MK, Mestre H, Nedergaard M. The glymphatic pathway in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol 2018;17(11):1016-24. [CrossRef]

- Jiang H, Wei H, Zhou Y, Xiao X, Zhou C, Ji X. Overview of the meningeal lymphatic vessels in aging and central nervous system disorders. Cell Biosci 2022;12(1):202. [CrossRef]

- Butler T, Zhou L, Ozsahin I, Wang XH, Garetti J, Zetterberg H, et al. Glymphatic clearance estimated using diffusion tensor imaging along perivascular spaces is reduced after traumatic brain injury and correlates with plasma neurofilament light, a biomarker of injury severity. Brain Commun 2023;5(3):fcad134. [CrossRef]

- Benveniste H, Liu X, Koundal S, Sanggaard S, Lee H, Wardlaw J. The glymphatic system and waste clearance with brain aging: A review. Gerontology 2019;65(2):106-19. [CrossRef]

- Mummery CJ, Börjesson-Hanson A, Blackburn DJ, Vijverberg EGB, De Deyn PP, Ducharme S, et al. Tau-targeting antisense oligonucleotide MAPTRx in mild Alzheimer's disease: A phase 1b, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Nat Med 2023 Apr 24. [CrossRef]

- BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. NIH registered clinical trial NCT02754076—A treatment study of Mucopolysaccharidosis Type IIIB: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02754076 [site accessed 1 June 2023].

- Bonda DJ, Castellani RJ, Zhu X, Nunomura A, Lee HG, Perry G, et al. A novel perspective on tau in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2011;8(6):639-42. [CrossRef]

- Lee HG, Perry G, Moreira PI, Garrett MR, Liu Q, Zhu X, et al. Tau phosphorylation in Alzheimer's disease: pathogen or protector? Trends Mol Med 2005;11(4):164-9. [CrossRef]

- Scherlinger M, Richez C, Tsokos GC, Boilard E, Blanco P. The role of platelets in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2023:1-16. [CrossRef]

- Abdul Ameer LA, Raheem ZJ, Abdulrazaq SS, Ali BG, Nasser MM, Khairi AWA. The anti-inflammatory effect of the platelet-rich plasma in the periodontal pocket. Eur J Dent 2018;12(4):528-31. [CrossRef]

- Kumar V, Talwar J, Rustagi A, Krishna LG, Sharma VK. Comparison of clinical and functional outcomes after platelet-rich plasma injection and corticosteroid injection for the treatment of de Quervain's tenosynovitis. J Wrist Surg 2022;12(2):135-42. [CrossRef]

- Rodeo, SA. Orthobiologics: Current status in 2023 and future outlook. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2023;31(12):604-13. [CrossRef]

- Wongjarupong A, Pairuchvej S, Laohapornsvan P, Kotheeranurak V, Jitpakdee K, Yeekian C, et al. Platelet-rich plasma epidural injection an emerging strategy in lumbar disc herniation: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2023;24(1):335. [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski E, Andreasen N, Tarkowski A, Blennow K. Intrathecal inflammation precedes development of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74(9):1200-5. [CrossRef]

- Opal SM, DePalo VA. Anti-inflammatory cytokines. Chest 2000;117(4):1162-72. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Middleton KK, Fu FH, Im HJ, Wang JH. HGF mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of PRP on injured tendons. PLoS One 2013;8(6):e67303. [CrossRef]

- Southworth TM, Naveen NB, Tauro TM, Leong NL, Cole BJ. The use of platelet-rich plasma in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. J Knee Surg 2019;32(1):37-45. [CrossRef]

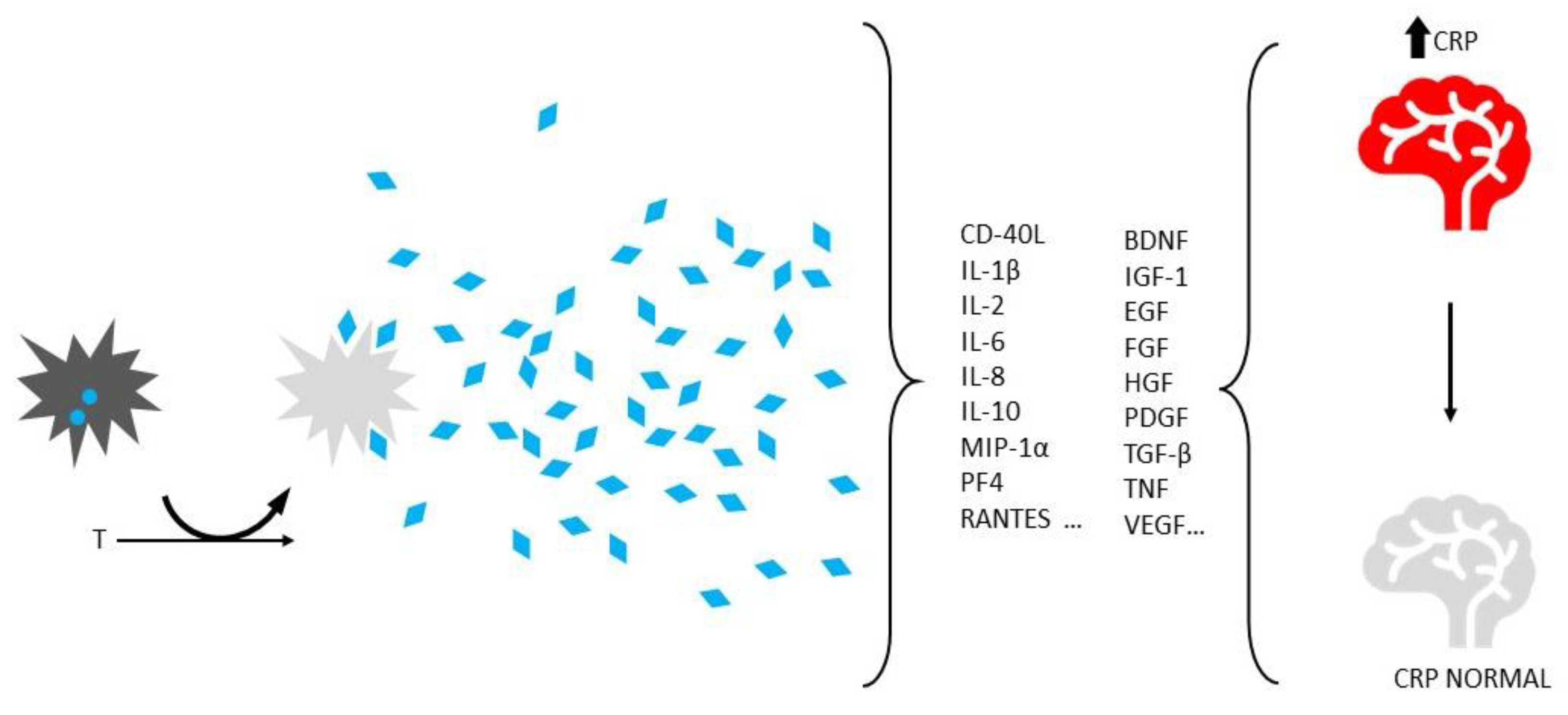

- Ziegler CG, Van Sloun R, Gonzalez S, Whitney KE, DePhillipo NN, Kennedy MI, et al. Characterization of growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines in bone marrow concentrate and platelet-rich plasma: A prospective analysis. Am J Sports Med 2019;47(9):2174-87. [CrossRef]

- Boukhatem I, Fleury S, Welman M, Le Blanc J, Thys C, Freson K, et al. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor prompts platelet aggregation and secretion. Blood Adv 2021;5(18):3568-80. [CrossRef]

- Mitsiadis TA, Pagella P. Expression of nerve growth factor (NGF), TrkA, and p75(NTR) in developing human fetal teeth. Front Physiol 2016;7:338. [CrossRef]

- Burk, K. The endocytosis, trafficking, sorting and signaling of neurotrophic receptors. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2023;196:141-65. [CrossRef]

- Park H, Poo MM. Neurotrophin regulation of neural circuit development and function. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013;14:7-23. [CrossRef]

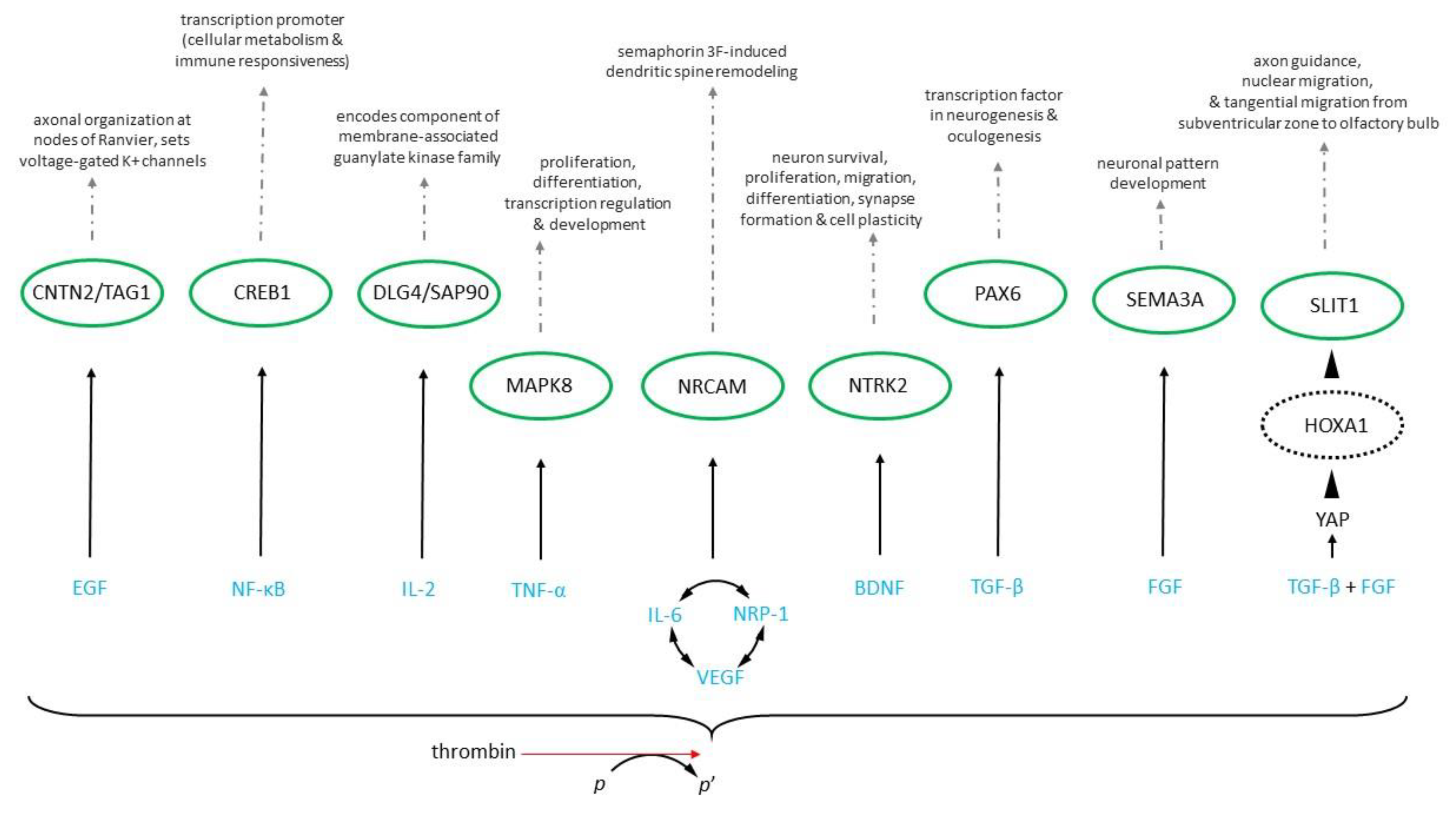

- Su LN, Song XQ, Wei HP, Yin HF. Identification of neuron-related genes for cell therapy of neurological disorders by network analysis. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2017;18(2):172-82. [CrossRef]

- Chen NF, Sung CS, Wen ZH, Chen CH, Feng CW, Hung HC, et al. Therapeutic effect of platelet-rich plasma in rat spinal cord injuries. Front Neurosci 2018;12:252. [CrossRef]

- Fu L, Liu L, Zhang J, Xu B, Fan Y, Tian J. Brain network alterations in Alzheimer's disease identified by early-phase PIB-PET. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2018;2018:6830105. [CrossRef]

- Azodi S, Nair G, Enose-Akahata Y, Charlip E, Vellucci A, Cortese I, et al. Imaging spinal cord atrophy in progressive myelopathies: HTLV-I-associated neurological disease (HAM/TSP) and multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2017;82(5):719-28. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi RM, Palesi F, Castellazzi G, Vitali P, Anzalone N, Bernini S, et al. Unsuspected Involvement of Spinal Cord in Alzheimer Disease. Front Cell Neurosci 2020;14:6. [CrossRef]

- Borhani-Haghighi M, Mohamadi Y. The therapeutic effect of platelet-rich plasma on the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. J Neuroimmunol 2019;333:476958. [CrossRef]

- D'Souza SD, Antel JP, Freedman MS. Cytokine induction of heat shock protein expression in human oligodendrocytes: An interleukin-1-mediated mechanism. J Neuroimmunol 1994;50(1):17-24. [CrossRef]

- Hasan RJ, Ameredes BT, Calhoun WJ. Cytokine mediated regulation of heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) and steroid receptor function. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;121(2 Suppl 1):S120. [CrossRef]

- Tao SC, Yuan T, Rui BY, Zhu ZZ, Guo SC, Zhang CQ. Exosomes derived from human platelet-rich plasma prevent apoptosis induced by glucocorticoid-associated endoplasmic reticulum stress in rat osteonecrosis of the femoral head via the Akt/Bad/Bcl-2 signal pathway. Theranostics 2017;7(3):733-50. [CrossRef]

- Terrab L, Wipf P. Hsp70 and the unfolded protein response as a challenging drug target and an Inspiration for probe molecule development. ACS Med Chem Lett 2020;11(3):232-6. [CrossRef]

- Wei X, Jin XH, Meng XW, Hua J, Ji FH, Wang LN, et al. Platelet-rich plasma improves chronic inflammatory pain by inhibiting PKM2-mediated aerobic glycolysis in astrocytes. Ann Transl Med 2020;8(21):1456. [CrossRef]

- Filardo G, Kon E. PRP: More words than facts. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012;20(9):1655-6. [CrossRef]

- Hamid MS, Yusof A, Mohamed Ali MR. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for acute muscle injury: A systematic review. PLoS One 2014;9(2):e90538. [CrossRef]

- Sills ES, Wood SH. Epigenetics, ovarian cell plasticity, and platelet-rich plasma: Mechanistic theories. Reprod Fertil 2022;3(4):C44-C51. [CrossRef]

- Andia I, Maffulli N. A contemporary view of platelet-rich plasma therapies: Moving toward refined clinical protocols and precise indications. Regen Med 2018;13(6):717-28. [CrossRef]

- Rickers NS, Sills ES. Is autologous platelet activation the key step in ovarian therapy for fertility recovery and menopause reversal? Biomedicine (Taipei) 2022;12(4):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Padilla S, Orive G, Anitua E. Shedding light on biosafety of platelet rich plasma. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2017;17(8):1047-8. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez M, Anitua E, Delgado D, Sanchez P, Prado R, Orive G, et al. Platelet-rich plasma, a source of autologous growth factors and biomimetic scaffold for peripheral nerve regeneration. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2017;17(2):197-212. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Solé O, Rodó J, García-Aparicio L, Blanch J, Cusí V, Albert A. Effects of platelet-rich plasma on a model of renal ischemia-reperfusion in rats. PLoS One 2016;11(8):e0160703. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).