1. Introduction

Cryoglobulinaemia is defined by immunoglobulins which precipitate at temperatures below 37°C and redissolve on warming. The first description originated in 1933 in a patient with myeloma, previously diagnosed as Raynaud’s disease (1). By 1974, Brouet and colleagues identified three distinct immunological types based on a series of 86 patients and this classification remains in use today (2). Type I cryoglobulinaemia consists of monoclonal immunoglobulins only. Type II consists of a monoclonal immunoglobulin component possessing avidity for the polyclonal component of a different isotype. Type III is defined by mixed polyclonal immunoglobulins of any isotype which mostly form complexes. In the original series, type III was the most common (50%), with similar proportions of type I and type II. As a polyclonal disorder, type III cryoglobulins are most commonly found in viral infections (mainly hepatitis) and autoimmune disorders.

Monoclonal IgM associated disorders can be associated with type I and II cryoglobulins. In type II cryoglobulinaemia this is most frequently an IgM immunoglobulin with the ability to bind polyclonal IgG. This is defined as rheumatoid factor activity, the ability to bind to the Fc portion of IgG. Rheumatoid factor (RF) detected in type II cryoglobulinaemia is a monoclonal IgM-kappa in over 85% of cases) (3). In this review we discuss the clinical characteristics, laboratory considerations and suggest a management approach of monoclonal IgM associated cryoglobulinaemia.

2. Clonal IgM disorders

IgM monoclonal (M) protein is observed in premalignant and malignant clonal disorders. IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is defined by asymptomatic circulating IgM M-protein below 30 g/L with a lymphoplasmacytic bone marrow infiltration of less than 10% (4). IgM MGUS may progress to non-Hodgkin lymphomas, mainly Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM), chronic lymphocytic lymphoma or rarely, to plasma cell neoplasms, including IgM myeloma. Type I and II cryoglobulinaemia may be associated with any of these disorders. The term IgM monoclonal gammopathy of clinical significance (MGCS) have been used to describe disorders with typically low marrow infiltrate (<10% marrow infiltration) but with clinically significant organ manifestations of the IgM (5). Type I and II cryoglobulinaemia are included in IgM MGCS alongside cold agglutinin disease, IgM-associated neuropathies, AL amyloidosis, Schnitzler syndrome and others. Most recently IgM cryoglobulins have been included in a subset of monoclonal gammopathies of thrombotic significance due to their potential thrombotic manifestations (6). Type II cryoglobulins are most commonly associated with chronic hepatitis C infection and autoimmune conditions such as Sjögren’s syndrome. This is a risk factor (as well as low C3, C4, CD4/CD8 T-cell ratio) in developing lymphoproliferative disorders including marginal zone lymphoma (7-9).

3. Clinical characteristics

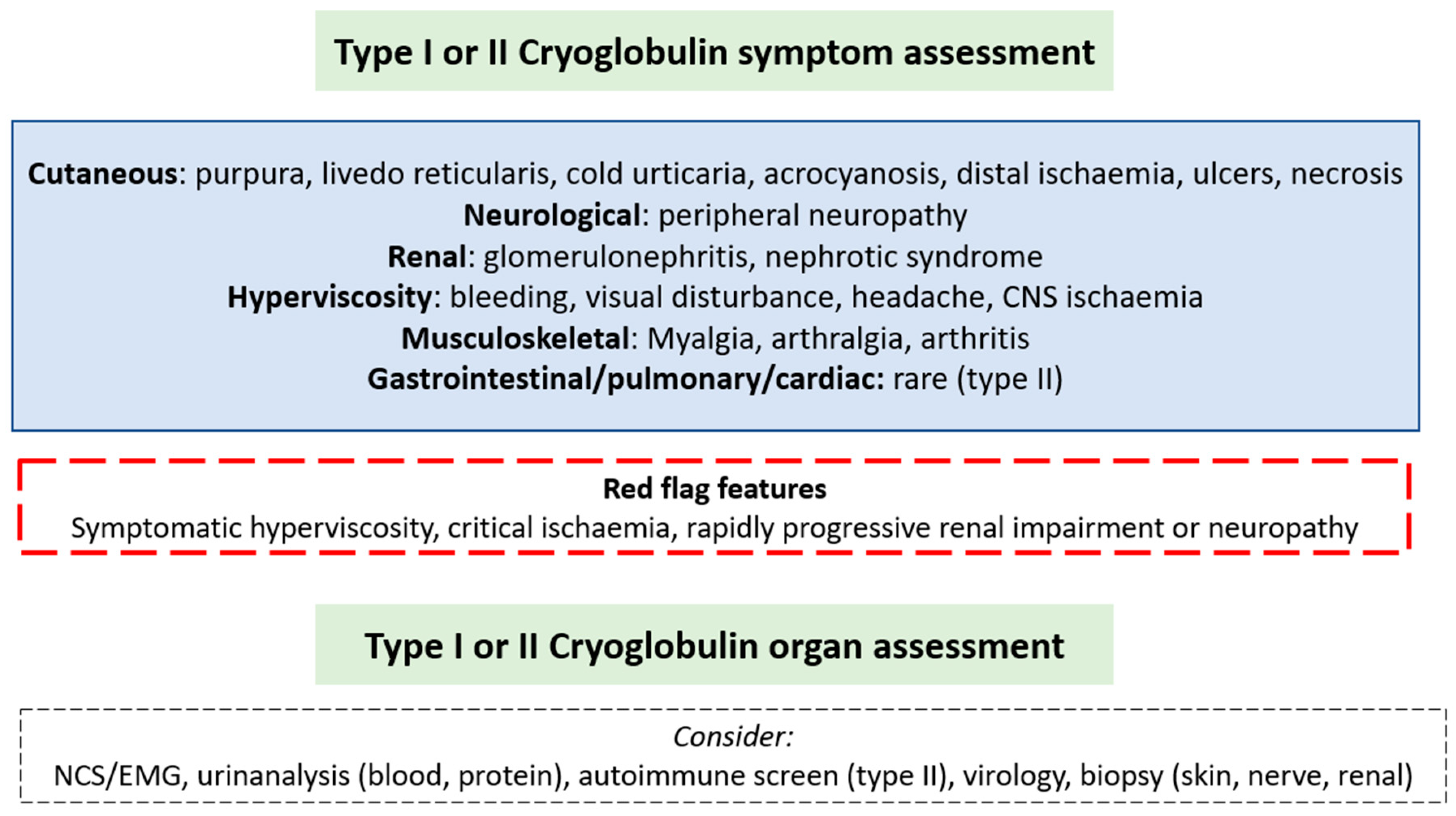

A wide spectrum of symptoms may be present dependent on the pattern of organ involvement and severity may range from asymptomatic to symptomatic disease (

Figure 1). Symptoms in type I disease are due to vascular occlusion from monoclonal immunoglobulin. Type II symptoms are typically due to small and medium-sized vessel vasculitis from immune-complexes of IgG antigens and IgM antibodies. Cutaneous involvement is the most frequently described manifestation triggered by the cold and most common in the extremities. Symptoms may include purpura, livedo reticularis, cold intolerance, digital ischaemic ulcers and necrosis. Other symptoms are outlined in

Figure 1. In a single centre report of 45 patients with type I cryoglobulinaemia, 26 patients had IgM isotype and 19 IgG. Of those with IgM associated cryoglobulinaemia, 46% had skin involvement, less than 10% peripheral neuropathy (8%), arthralgia (8%) or renal involvement (4%) (10). In this cohort, around a third of IgM patients had underlying WM, a third MGUS and a third other NHL, compared with those with IgG being two-thirds MGUS. Peripheral neuropathy was seen in 42% of IgG cases and only 8% of IgM, with similar proportions of other symptoms reported. Elsewhere peripheral neuropathy has been noted in around 50% of IgM cases, mainly sensory neuropathy (70%) however sensorimotor polyneuropathy and mononeuritis multiplex were also seen (11). Central nervous system involvement is rare unless due to hyperviscosity (12). No studies report specific presenting features of type II cryoglobulinaemia in those with circulating monoclonal IgM. In a mixed cohort of 203 type II patients with an underlying haematological disorder in 23%, skin manifestations predominated (85%). Compared to type I cryoglobulinaemia there was a greater proportion of peripheral neuropathy (56%), joint (41%), renal (38%), gastrointestinal (6%) and pulmonary (2%) involvement. Hyperviscosity is almost never seen in type II (13), unlike type I due to vascular occlusion. The commonest description of peripheral neuropathy in patients with mixed cryoglobulinaemia is of a small fibre sensory neuropathy (14).

4. Diagnostic evaluation

4.1. Cryoglobulin detection

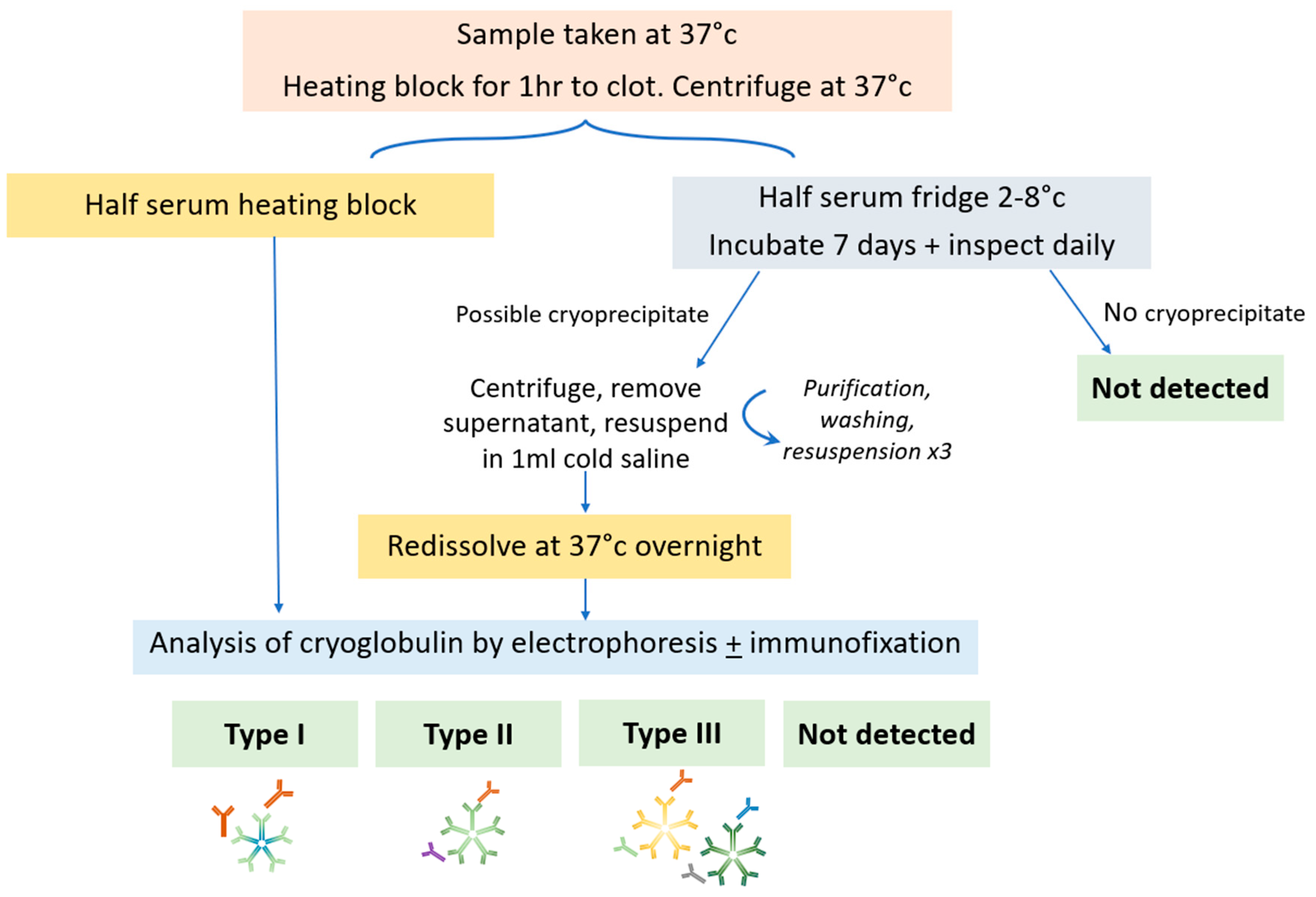

A schema of sample testing is shown in

Figure 2. Samples should be taken in prewarmed tubes and transported at 37°C, separated by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 2500 rpm and sample split into two aliquots (one at 4°C and one at 37°C). Half of the serum should be incubated at 37°C and analysed by electrophoresis to identify the presence of a M-protein. Half of the serum is incubated for 7 days at 4°C and inspected daily for the formation of a cryoprecipitate. If a precipitate is observed which is not present in the 37oC sample, it is washed three times in saline at 4oC, resuspended in saline and warmed to 37°C to redissolve it. Analysis of the cryoprecipitate is then performed by electrophoresis and immunofixation. The cryoglobulin may be quantified as a cryocrit (%) by the relative volume of precipitate as a proportion of the total serum volume, performed visually, so accuracy and reliability is poor particularly at low concentrations. Alternatively it may be monitored by the size of the M-protein. Typically those with type I have higher cryocrit than type II due to intravascular occlusion (15).

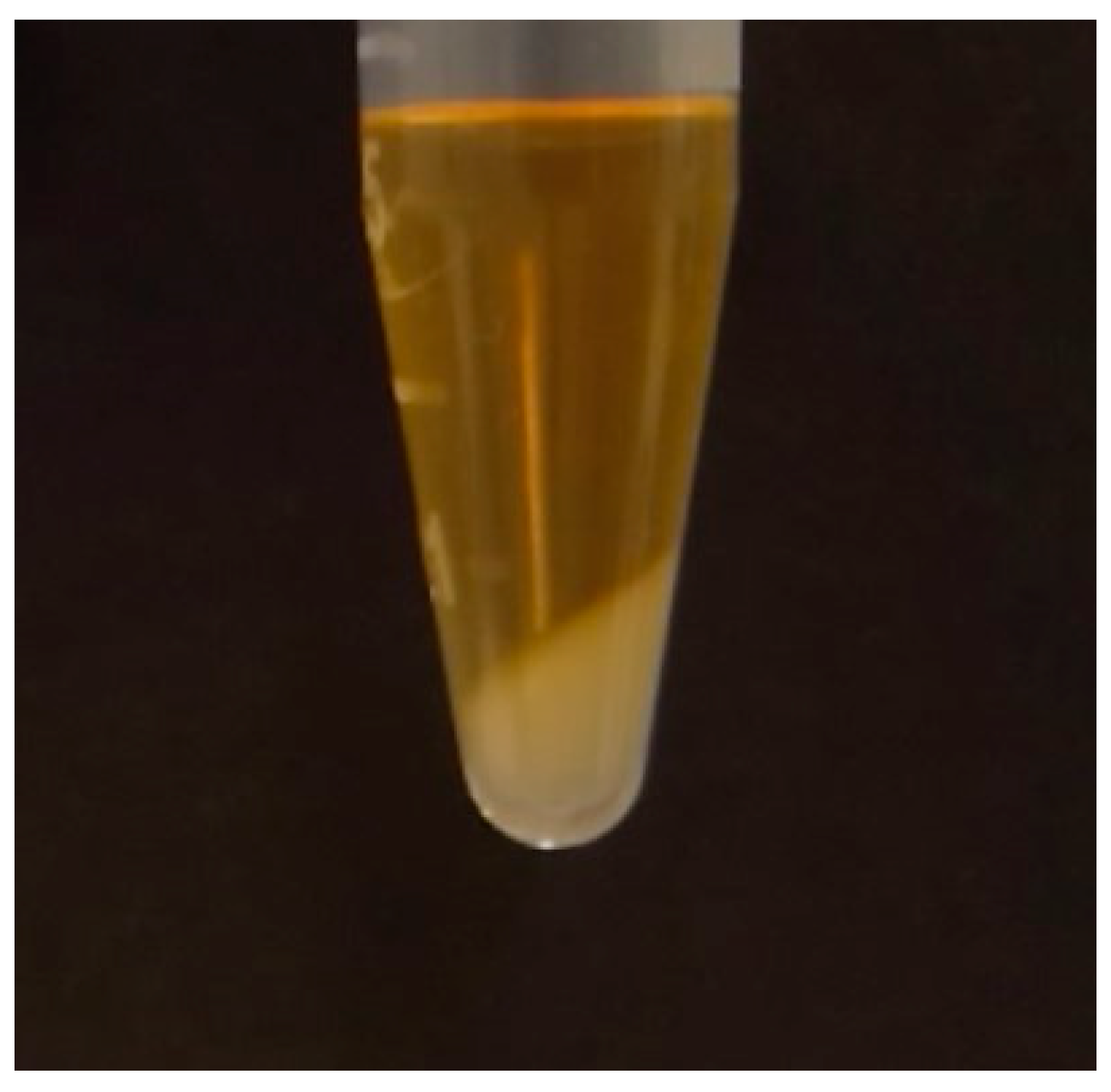

Figure 3 shows the appearances of a cryoprecipitate in the laboratory.

Detection of cryoglobulins may be challenging due to a number of potential pre-analytical errors such as samples being collected at too low a temperature and incompletely filled tubes. Ideally 10mL of sample should be provided. Accurate detection of cryoglobulins requires samples to be taken into pre-warmed tubes which must not be allowed to cool below 37˚C until the serum is separated as the cryoglobulin may precipitate and not be detected. This can be challenging particularly in the setting of laboratory testing which is some distance from where samples have been taken, as the temperature may fall by the time the sample reaches the laboratory. Additionally, a false-negative or underestimation of M-protein may result from the same process.

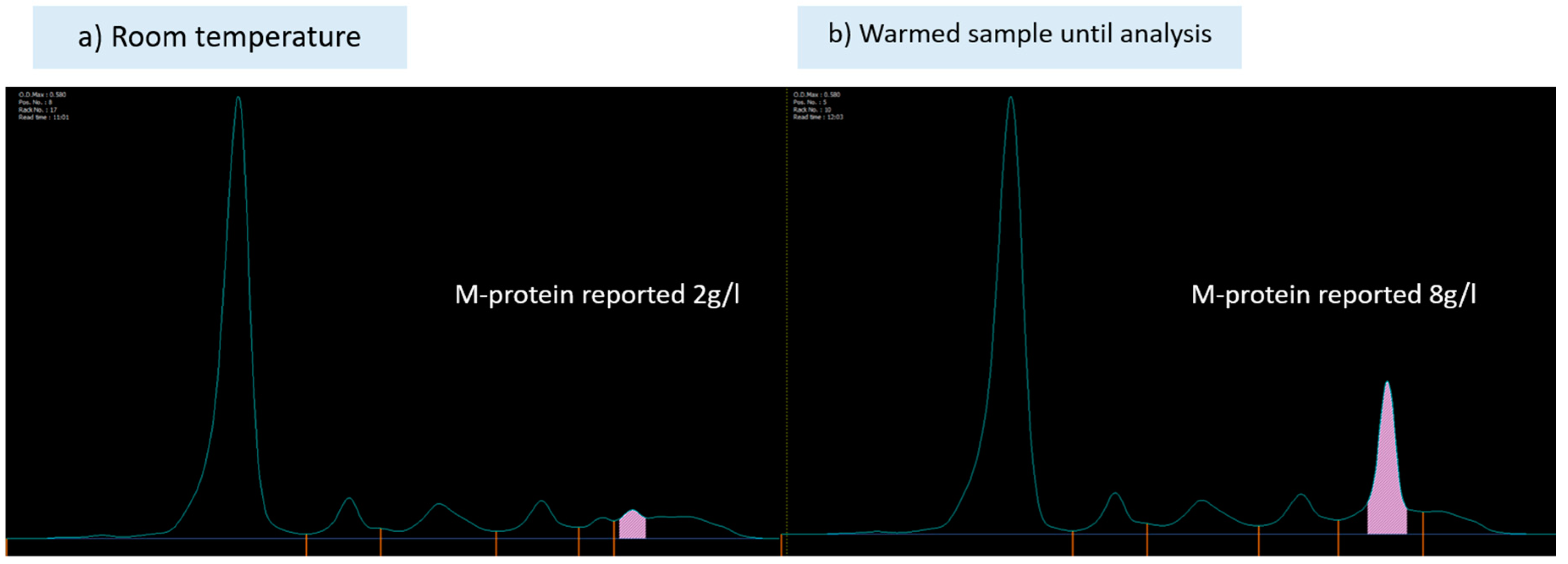

Figure 4 shows an example of this from samples taken from the same patient. Similarly, a raised plasma viscosity in the absence of a raised IgM M-protein may trigger clinicians to assess for cryoglobulins (16). In a large French study, 9% of cases with negative cryoglobulin detection were positive on a follow-up test (3). Care must be taken with preanalytical variables and repeat testing of M-protein and cryoglobulins is indicated if clinical suspicion is present.

Laboratory testing is critical as even a minimal amount of measurable cryoglobulin may result in symptoms. In one study where two-thirds of the cohort were symptomatic, 58% of those with IgM type I cryoglobulinaemia demonstrated a cryocrit of <1%, which was a significantly greater proportion than those with IgG cryoglobulins (10). Cryoglobulin concentration did not differ in MGUS compared to other lymphoproliferative associated type I cryoglobulins in a mixed cohort of 64 patients with IgG and IgM M-protein (17). Symptoms do not directly correlate with cryocrit and may depend instead on the temperature at which precipitation occurs (12). It should be noted that cryofibrinogens (cryoproteins that precipitate in plasma only, and not serum), may be associated with clinical vascultiic symptoms and testing therefore requested, however these are rarely due to an underlying IgM gammopathy (6) so are not discussed further here.

4.2. Organ involvement

Symptoms of disease should be corroborated by laboratory tests and investigations which include assessment of organ involvement and the underlying clonal disorder. Investigations including urinalysis for screening of renal involvement (proteinuria, haematuria, renal insufficiency) (18), nerve conduction studies, autoimmune screen and virology (HIV, hepatitis B and C serology) are useful. In those presenting with peripheral neuropathy, close collaboration with a neurologist with expertise in peripheral nerves is recommended as there is a wide differential of IgM-associated neuropathies (including anti-MAG peripheral neuropathy, non-MAG neuropathy, CANOMAD [Chronic Ataxic Neuropathy Ophthalmoplegia M-protein Agglutination Disialosyl antibodies syndrome], AL amyloidosis, Bing Neel syndrome or neurolymphomatosis, therapy related neuropathy). In those with rapidly progressing axonal and demyelinating peripheral neuropathy cryoglobulinaemia should be considered after AL amyloidosis is excluded (19). As such, screening tests for neuropathy including renal and liver function, HbA1c, serum B12 and folate, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin should be undertaken. Rheumatoid factor, complement factors and viral studies are essential particularly where type II cryoglobulins are detected, as immune complex deposition may cause activation of proinflammatory complement proteins and subsequent consumption of complement factors. Rheumatoid factor is associated with decreased C4 and CH50 (screening assay for the activation of the classical complement pathway) (3). Virology screening is necessary as most cases of type II cryoglobulins are associated with hepatitis. A biopsy may be required, particularly in establishing renal or nerve involvement to distinguish from other causes, however there are no standardised diagnostic criteria. Intravascular precipitation of IgM triggered by cold exposure results in thrombotic obstruction and ischaemia in small vessels as evidenced on biopsy in type I cryoglobulinaemia. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis, a small vessel vasculitis characterised by immune complex-mediated vasculitis of the dermal capillaries and venules, may be evident in type II. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis is characteristic and nephrotic range proteinuria, intraluminal thrombi and extracapillary proliferation have been associated with end stage renal disease in mixed cryoglobulinaemia (18). Nerve biopsy may demonstrate large fibre axonal degeneration without regeneration, accompanied by vasculitis (20). Intravascular cryoglobulin deposition without vasculitis may be present in the vasa nervorum or myelin sheaths and electron microscopy may identify monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition (21, 22).

Prior to any treatment, clonal assessment should be undertaken in all patients to assess the burden of the underlying haematological disease. Standard staging includes bone marrow biopsy and aspirate (immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, FISH, and Congo red staining – to exclude amyloidosis), molecular testing for MYD88, CXCR4 mutations and CT imaging of chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

5. Management

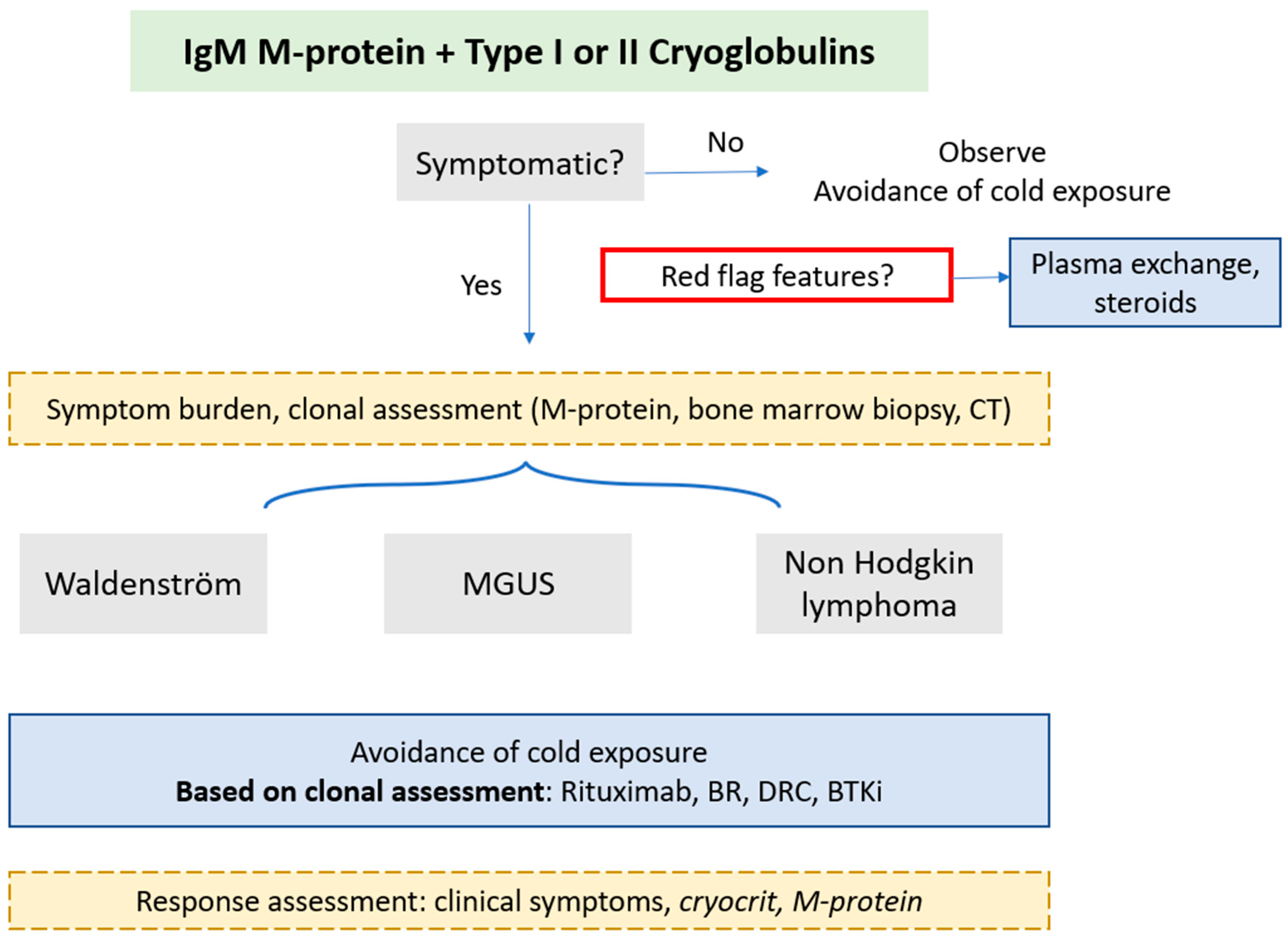

There is a paucity of data to guide optimal management. A suggested management approach is outlined in

Figure 5. Symptomatic cryoglobulinaemia is an indication for treatment and treatment choice should be guided by severity of symptoms. Mild symptoms may be abated with cold prevention alone and asymptomatic finding of cryoglobulins may need observation alone. However, rapidly progressive nephropathy and neuropathy have been reported at various stages of disease course, so careful monitoring is recommended (11). Treatment for cryoglobulin symptoms is reported in up to 80% of cohorts comprising of patients with symptomatic cryoglobulinaemia (23). Response assessment is not standardised and most focus on symptomatic improvement (10). Clinical symptom resolution is a priority, but disease activity markers (cryocrit for type I; complement and rheumatoid factor activity in type II) have been suggested (24). Cryocrit at treatment initiation, change in cryocrit and time to nadir were predictive of symptom improvement in a mixed cohort of IgG and IgM type I cases. The underlying diagnosis of MGUS or lymphoma did not affect symptom improvement in one series (23). Treatment regimens are heterogenous with small sample sizes.

5.1. Red flag symptoms

In those with red flag features or life-threatening manifestations (as outlined in

Figure 1), plasma exchange may ameliorate critical symptoms and is utilised in up to a third of all cryoglobulinaemia in mixed cohorts; warming procedures should be in place with all priming fluids and circuit apparatus pre-warmed and the replacement products run through a warmer (13, 17, 23). Steroids are used in up to 90% of all cases (1mg/kg), normally together with immunosuppression (13, 17). Plasma exchange should be also be considered first-line in those with severe refractory symptoms who fail to respond to (or who are ineligible for) other treatments (25).

5.2. Symptomatic disease

In the absence of robust evidence, definitive treatment should be directed at the underlying clone: in the majority of cases this will be WM and rarely other NHL (chronic lymphocytic leukaemia or marginal zone lymphoma) (26). Colchicine has been described as efficacious in patients with limited cutaneous manifestations (purpura) and mixed cryoglobulinaemia, however these cohorts did not include patients with underlying haematological disorders so are unlikely to be solely effective (27). Rituximab combinations or bortezomib based treatment are most commonly employed (10) with symptom response rate of approximately 80% (10, 12, 17). Disappearance of cryoglobulin may be seen in a half of patients (23). No studies have explored therapy exclusively for mixed cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis in the context of IgM disorders. However, a randomised controlled trial compared rituximab monotherapy with azathioprine or cyclophosphamide for the treatment of severe cryoglobulinemic vasculitis in 59 patients (skin ulcers, active glomerulonephritis, peripheral neuropathy) with or without hepatitis C. Survival at 12 months was higher in the rituximab treated group (64.3 vs. 3.5 %, p < 0.0001) with improved reduction in vasculitis scores was well tolerated (28).

As standard, we consider delaying rituximab if IgM M-protein is significantly raised (>40g/l) to prevent IgM flare and hyperviscosity. Transient disease exacerbation due to the IgM flare has been described following the use of rituximab in patients with type I cryoglobulins and low burden of disease (<10% infiltrate) (29) and in type II cryoglobulinaemia (30). A study examining plasma exchange prior to rituximab to prevent IgM flare is ongoing (NCT04692363). Historically there has been concern of treatment-emergent neurotoxicity with the use of bortezomib which may be a particular concern in those with cryoglobulinaemic peripheral neuropathy, however weekly, subcutaneous administration and close monitoring may ameliorate the risk and has been shown to be efficacious in WM (31). Effective depletion of the clonal disease by bortezomib is likely to supersede its potential neurotoxicty. Autologous stem cell transplantation has been employed in cryoglobulinaemia associated with underlying myeloma but not exclusively for those with WM, MGUS or NHL. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors are a mainstay treatment in WM but their use in IgM cryoglobulinaemia has not been reported; the speed and depth of clonal depletion could be key to the effectiveness of this class of treatment.

6. Conclusion

Type I and II cryoglobulins may be present in patients with IgM associated disorders and are a part of a distinctive entity of IgM MGCS. Presentations range from asymptomatic disease to multisystem involvement so careful evaluation of the features and thorough interrogation of organ systems and the underlying clone is critical. Patients may present with WM, IgM MGUS or NHL. Treatment approaches, formal assessment of severity and response criteria in cryoglobulinaemia are not standardised. Immediate management is required for clinical red flag features. Due to their rarity, data to inform treatment decisions are scant and collaborative research is imperative to aid defining optimal treatment strategies.

Author Contributions

JK wrote the manuscript. SJS, SDS reviewed the manuscript and all authors read and agreed the final version.

Funding

No external funding was received.

Informed consent statement

Not applicable.

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wintrobe N, Buell M. Hypreproteinemia associated with multiple myeloma With report of case in which extraordinary hyperproteinemia was associated with thrombosis of retinal veins and symptom suggesting Raynauds disease.: Bull Johns Hopkins hospital; 1933.

- Brouet JC, Clauvel JP, Danon F, Klein M, Seligmann M. Biologic and clinical significance of cryoglobulins. A report of 86 cases. Am J Med. 1974;57(5):775-88. [CrossRef]

- Kolopp-Sarda MN, Nombel A, Miossec P. Cryoglobulins Today: Detection and Immunologic Characteristics of 1,675 Positive Samples From 13,439 Patients Obtained Over Six Years. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(11):1904-12. [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375-90. [CrossRef]

- Khwaja J, D'Sa S, Minnema MC, Kersten MJ, Wechalekar A, Vos JM. IgM monoclonal gammopathies of clinical significance: diagnosis and management. Haematologica. 2022;107(9):2037-50. [CrossRef]

- Gkalea V, Fotiou D, Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E. Monoclonal Gammopathy of Thrombotic Significance. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(2). [CrossRef]

- Tzioufas AG, Boumba DS, Skopouli FN, Moutsopoulos HM. Mixed monoclonal cryoglobulinemia and monoclonal rheumatoid factor cross-reactive idiotypes as predictive factors for the development of lymphoma in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(5):767-72.

- Theander E, Henriksson G, Ljungberg O, Mandl T, Manthorpe R, Jacobsson LT. Lymphoma and other malignancies in primary Sjögren's syndrome: a cohort study on cancer incidence and lymphoma predictors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(6):796-803.

- Monti G, Pioltelli P, Saccardo F, Campanini M, Candela M, Cavallero G, et al. Incidence and characteristics of non-Hodgkin lymphomas in a multicenter case file of patients with hepatitis C virus-related symptomatic mixed cryoglobulinemias. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(1):101-5. [CrossRef]

- Zhang LL, Cao XX, Shen KN, Han HX, Zhang CL, Qiu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcome of type I cryoglobulinemia in Chinese patients: a single-center study of 45 patients. Ann Hematol. 2020;99(8):1735-40.

- Néel A, Perrin F, Decaux O, Dejoie T, Tessoulin B, Halliez M, et al. Long-term outcome of monoclonal (type 1) cryoglobulinemia. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(2):156-61. [CrossRef]

- Harel S, Mohr M, Jahn I, Aucouturier F, Galicier L, Asli B, et al. Clinico-biological characteristics and treatment of type I monoclonal cryoglobulinaemia: a study of 64 cases. Br J Haematol. 2015;168(5):671-8. [CrossRef]

- Terrier B, Krastinova E, Marie I, Launay D, Lacraz A, Belenotti P, et al. Management of noninfectious mixed cryoglobulinemia vasculitis: data from 242 cases included in the CryoVas survey. Blood. 2012;119(25):5996-6004. [CrossRef]

- Gemignani F, Brindani F, Alfieri S, Giuberti T, Allegri I, Ferrari C, et al. Clinical spectrum of cryoglobulinaemic neuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(10):1410-4. [CrossRef]

- Monti G, Galli M, Invernizzi F, Pioltelli P, Saccardo F, Monteverde A, et al. Cryoglobulinaemias: a multi-centre study of the early clinical and laboratory manifestations of primary and secondary disease. GISC. Italian Group for the Study of Cryoglobulinaemias. Qjm. 1995;88(2):115-26.

- Hira-Kazal R, Sayar Z, Kothari J, Ayrton P, Berney S, Maher J. Cryoglobulinaemia identified by repeated analytical failure of laboratory tests. Lancet. 2014;383(9914):382. [CrossRef]

- Terrier B, Karras A, Kahn JE, Le Guenno G, Marie I, Benarous L, et al. The spectrum of type I cryoglobulinemia vasculitis: new insights based on 64 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2013;92(2):61-8.

- Zaidan M, Terrier B, Pozdzik A, Frouget T, Rioux-Leclercq N, Combe C, et al. Spectrum and Prognosis of Noninfectious Renal Mixed Cryoglobulinemic GN. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(4):1213-24. [CrossRef]

- D'Sa S, Kersten MJ, Castillo JJ, Dimopoulos M, Kastritis E, Laane E, et al. Investigation and management of IgM and Waldenström-associated peripheral neuropathies: recommendations from the IWWM-8 consensus panel. Br J Haematol. 2017;176(5):728-42. [CrossRef]

- Nemni R, Corbo M, Fazio R, Quattrini A, Comi G, Canal N. Cryoglobulinaemic neuropathy. A clinical, morphological and immunocytochemical study of 8 cases. Brain. 1988;111 ( Pt 3):541-52.

- Vallat JM, Desproges-Gotteron R, Leboutet MJ, Loubet A, Gualde N, Treves R. Cryoglobulinemic neuropathy: a pathological study. Ann Neurol. 1980;8(2):179-85. [CrossRef]

- Ciompi ML, Marini D, Siciliano G, Melchiorre D, Bazzichi L, Sartucci F, et al. Cryoglobulinemic peripheral neuropathy: neurophysiologic evaluation in twenty-two patients. Biomed Pharmacother. 1996;50(8):329-36. [CrossRef]

- Sidana S, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Gertz MA, Buadi FK, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of patients with type 1 monoclonal cryoglobulinemia. Am J Hematol. 2017;92(7):668-73. [CrossRef]

- Motyckova G, Murali M. Laboratory testing for cryoglobulins. Am J Hematol. 2011;86(6):500-2. [CrossRef]

- Pratt G, El-Sharkawi D, Kothari J, D'Sa S, Auer R, McCarthy H, et al. Diagnosis and management of Waldenström macroglobulinaemia-A British Society for Haematology guideline. Br J Haematol. 2022;197(2):171-87.

- Khwaja J, Salter S, Patel AS, Baker R, Gupta R, Rismani A, et al. Type 1 Cryoglobulinaemia Associated with Waldenström Macroglobulinemia, IgM MGUS or Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Blood. 2022;140(Supplement 1):3653-4.

- Invernizzi F, Monti G. Colchicine and mixed cryoglobulinemia. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(5):722-3. [CrossRef]

- De Vita S, Quartuccio L, Isola M, Mazzaro C, Scaini P, Lenzi M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of rituximab for the treatment of severe cryoglobulinemic vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(3):843-53. [CrossRef]

- Nehme-Schuster H, Korganow AS, Pasquali JL, Martin T. Rituximab inefficiency during type I cryoglobulinaemia. Rheumatology (Oxford). 44. England2005. p. 410-1. [CrossRef]

- Sène D, Ghillani-Dalbin P, Amoura Z, Musset L, Cacoub P. Rituximab may form a complex with IgMkappa mixed cryoglobulin and induce severe systemic reactions in patients with hepatitis C virus-induced vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(12):3848-55.

- Khwaja J, Uppal E, Baker R, Trivedi K, Rismani A, Gupta R, et al. Bortezomib-based therapy is effective and well tolerated in frontline and multiply pre-treated Waldenström macroglobulinaemia including BTKi failures: A real-world analysis. EJHaem. 2022;3(4):1330-4. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).