Submitted:

09 June 2023

Posted:

09 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Calone, R.; Mircea, D.M.; González-Orenga, S.; Boscaiu, M.; Lambertini, C.; Barbanti, L.; Vicente, O. Recovery from Salinity and Drought Stress in the Perennial Sarcocornia fruticosa vs. the Annual Salicornia europaea and S. veneta. Plants. 2022, 11, 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11081058. [CrossRef]

- Davari, M.; Gholami, L.; Nabiollahi, K.; Homaee, M.; Jafari, H.J. Deforestation and cultivation of sparse forest impacts on soil quality (case study: West Iran, Baneh). Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 198, 104504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2019.104504. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zong, M.; Fanm, Z.; Feng, Y.; Li, S.; Duan, C.; Li, H. Determining the impacts of deforestation and corn cultivation on soil quality in tropical acidic red soils using a soil quality index. Ecol. Ind. 2021, 125, 107580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107580. [CrossRef]

- Macedo, M. C. M. Integração lavoura e pecuária: o estado da arte e inovações tecnológicas. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2009, 38, 133-146.

- Zeraatpisheh, M.; Bakhshandeh, E.; Hosseini, M.; Alavi, S. Assessing the effects of deforestation and intensive agriculture on the soil quality through digital soil mapping. Geoderma. 2020, 363, 114139.

- Moreira, F.M.S.; Siqueira, J.O. Microbiologia e bioquímica do solo. UFLA: Lavras, Brasil, 2006.

- Diaz-Gonzalez, F.A.; Vuelvas, J.; Correia, C.A.; Velho, V.E.; Patino, D. Machine learning and remote sensing techniques applied to estimate soil indicators – Review. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 135, 108517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.108517. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.; López-Piñeiro, A.; Ramirez, M. Soil quality attributes of conservation management regimes in a semi-arid region og south western Spain. Soil & Tillage Research: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2007.

- Camargo, F.F. Indicadores físicos, químicos e biológicos da qualidade do solo em sistemas agroflorestais agroecológicos na área de preservação ambiental Serra da Mantiqueira, MG. Doctoral Thesis, Universidade Federal de Lavras, Lavras, 2016.

- Jung, J.; Maeda, M.; Chang, A.; Bhandari, M.; Ashapure, A.; Landivar-Bowles, J. The potential of remote sensing and artificial intelligence as tools to improve the resilience of agri- culture production systems. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2021, 70, 15-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2020.09.003. [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.G. Uso e monitoramento de indicadores microbiológicos para avaliação de qualidade do solo de cerrado sobre diferentes agroecossistemas. Masters Dissertation, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, 2008.

- Souza, K.B.; Pedrotti, A.; Resende, S.C.; Santos, H.M.T.; Menezes, M.M.G.; Santos, L.A.M. Importância de Novas Espécies de Plantas de Cobertura de Solo para os Tabuleiros Costeiros. Rev. Fapese. 2008, 4, 131-140.

- Harasim, E.; Gaweda, D.; Wesolowski, M.; Kwiatkowski, C.; Gocol, M. Cover cropping influences physico-chemical soil properties under direct drilling soybean. Acta Agric. Scand. Sec. B, Soil Plant Sci. 2016, 66, 85-94. https://doi.org/10.1080/09064710.2015.1066420. [CrossRef]

- Cherubin, M.R.; Karlen, D.L.; Cerri, C.E.P.; Franco, A.L.C.; Tormena, C.A.; Davies, C.A.; Cerri, C.C. Soil Quality Indexing Strategies for Evaluating Sugarcane Expansion in Brazil. PLoS ONE. 2016, 11, 0150860. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150860. [CrossRef]

- Rabary, B.; Sall, S.; Letourmy, P.; Husson, O.; Ralambofetra, E.; Moussa, N.; Chotte, J.L. Effects of living mulches or residue amendments on soil microbial properties in direct seeded cropping systems of Madagascar. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2008, 39, 236-243. [CrossRef]

- Parra, J.R.P.; Panizzi, A.R.; Haddad, M.L. Índices nutricionais para medir consumo e utilização de alimento por insetos. In Bioecologia e nutrição de insetos: base para o manejo integrado de pragas, Panizzi, A.R., Parra, J.R.P., Eds.; Embrapa Soja: Brasília, Brasil, 2009; pp. 37-90.

- Sparling, G.P. Soil microbial biomass, activity and nutrient cycling as indicators of soil health. In Biological Indicators of Soil Health, Pankhurst, C.E., Doube, B.M., Gupta, V.V.S.R., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, Inglaterra, 1997; pp. 97-120.

- Ibrahimi, K.; Attia, K.; Amami, R.; Américo-Pinheiro, J.H.P; Sher, F. Assessment of three decades treated wastewater impact on soil quality in semi-arid agroecosystem. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2022, 21, 525-535.

- Araújo, R.; Goedert, W.J.; Lacerda, M.P.C. Qualidade de um solo sob diferentes usos e sob cerrado nativo. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo. 2007, 31, 1099-1108.

- Singh, J.S.; Gupta, S.R. Plant decomposition and soil respiration in terrestrial ecosystems. Bot. Rev. 1977, 43, 449-528. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02860844. [CrossRef]

- Souto, P.C.; Bakke, I.A.; Souto, J.S.; Oliveira, V.M. Cinética da respiração edáfica em dois ambientes distintos no semiárido da Paraíba, Brasil. Rev. Caatinga 2009, 22, 52-58.

- Ramos, M.R.; Favaretto, N.; Dieckow, J.; Dedeck, R.A.; Vezzani, F.M.; Almeida, L.; Sperrin, M. Soil, water and nutrient loss under conventional and organic vegetable production managed in small farms versus forest system. J. Agric. Rural Dev. Trop. Subtrop. 2014, 115, 131–140.

- Damasceno, J.; Souto, J.S. Indicadores biológicos do núcleo de desertificação do seridó ocidental da Paraiba. Rev. Geogr. 2014, 31, 100-132.

- Santos, O.F.; Souza, H.M.; Oliveira, M.P.; Caldas, M.B.; Roque, C.G. Propriedades químicas de um Latossolo sob diferentes sistemas de manejo. Rev. Agric. Neotrop. 2017, 4, 36-42. https://periodicosonline.uems.br/index.php/agrineo/article/view/1185.

- öhlinger, R. Bestimmung der Bodenatmung im Laborversuch. In Bodenbiologische Arbeitsmethoden, Schinner, F., Öhlinger, R., Kandeler, E., Margesin, R., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1993; pp. 86-90.

- Severino, L.S.; Costa, F.X.; Beltrão, N.E.M.; Lucena, A.M.A.; Guimarães, M.M.B. Mineralização da torta de mamona, esterco bovino e bagaço de cana estimada pela respiração microbiana. Rev. Biol. Ciênc. Terra 2005, 5, 54-59.

- Barbosa, M.A.; Ferraz, R.L.S.; Coutinho, E.L.M.; Coutinho Neto, A.M.; Silva, M.S.; Fernandes, C.; Rigobelo, E.C. Multivariate analysis and modeling of soil quality indicators in long-term management systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 457-465. [CrossRef]

- Alves, T.D.S.; Campos, L.L.; Neto, N.E.; Matsuoka, M.; Loureiro, M.F. Biomassa e atividade microbiana de solo sob vegetação nativa e diferentes sistemas de manejos. Acta Sci., Agron. 2011, 33, 341-347. https://doi.org/10.4025/actasciagron.v33i2.4841. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, D.M.G.; Miranda, L.N.; Oliveira, S.A. Acidez do solo e sua correção. In Fertilidade do solo, Novais, R.F., Alvarez V.V.H., Barros, N.F., Fontes, R.L.F., Cantarutti, R.B., Neves, J.C.L., Eds.; Viçosa: Sociedade Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, Brasil, 2007; pp. 205-274.

- Canellas, L.P.; Velloso, A.C.X.; Marciano, C.R.; Ramalho, J.F.G.P.; Rumjanek, V.M.; Rezende, C.E.; Santos, G.A. Propriedades químicas de um cambissolo cultivado com cana-de-açúcar, com preservação do palhiço e adição de vinhaça por longo tempo. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo. 2003, 27, 935-944. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid= S0100-06832003000500018.

- Santos, H.G.; Jacomine, P.K.T.; Anjos, L.H.C.; Oliveira, V.A.; Lumbreras, J.F.; Coelho, M.R.; Almeida, J.A.; Araújo Filho, J.C.; Oliveira, J.B.; Cunha, T.J.F. Sistema Brasileiro de Classificação de Solos. EMBRAPA, 2018; 353.

- Bilibio, W.D.; Correia, G.F.; Borges, E.N. Atributos físicos e químicos de um latossolo, sob diferentes sistemas de cultivo. Rev. Ciênc. Agrotecnológica. 2010, 34, 817-822. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-70542010000400004. [CrossRef]

- Ciotta, M.N.; Bayer, C.; Fontoura, S.M.V.; Ernani, P.R.; Albuquerque, J.A. Matéria orgânica e aumento da capacidade de troca de cátions em solo com argila de atividade baixa sob plantio direto. Ciênc. Rural. 2003, 33, 1161-1164. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782003000600026. [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, J.; Hermosín, M. C. Interaction of Humic Substances and Soil Clays. In Humic substances in terrestrial ecosystems, Piccolo, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1996; pp. 595-624.

- Ernani, P.R.; Gianello, C. Diminuição do alumínio trocável do solo pela incorporação de esterco de bovinos e cama de aviário. Rev. Bras. Ciênci. Solo. 1983, 7, 161-165.

- Souza, E.D.; Costa, S.E.V.G.A.; Anghinoni, I.; Lima, C.V.S.; Carvalho, P.C.F.; Martins, A.P. Biomassa microbiana do solo em sistema de integração lavourapecuária em plantio direto, submetido a intensidades de pastejo. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo. 2010, 34, 79-88. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832010000100008. [CrossRef]

- Hargrove, W.L.; Thomas, G.W. Effect of organic matter on exchangeable aluminum and plant growth in acid soils. In Chemistry in the soil environment, Dowdy, R.H., Ed.; ASA Spec. Publ. 40. ASA and SSSA: Madison, Wisconsin, 1981.

- Sposito, G. The chemistry of soils. Oxford University Press: New York, United States, 1989. pp. 277.

- Kluthcouski, J.; Cobucci, T.; Aidar, H.; Costa, J.L.S.; Portela, C. Cultivo do Feijoeiro em Palhada de Braquiária. Santo Antônio de Goiás. (Documentos 157). Embrapa Arroz e Feijão. 2003.

- Mazurana, M.; Fink, J.R.; Camargo, E.; Schmitt, C.; Andreazza, R.; Camargo, F.A.O. Estoque de carbono e atividade microbiana em sistema de plantio direto consolidado no Sul do Brasil. Rev. Ciênc. Agrár. 2013, 36, 288-296. https://doi.org/10.19084/rca.16311. [CrossRef]

- Gatiboni, L.C.; Kaminski, J.; Rheinheimer, D. Dos S.; Flores, J.P.C. Biodisponibilidade de formas de fósforo acumuladas em solo sob sistema plantio direto. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo. 2007, 31, 691-699.

- Rosolem, C.A.; Calonego, J.C.; Foloni, J.S.S. Lixiviação de potássio da palha de espécies de cobertura de solo de acordo com a quantidade de chuva aplicada. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo. 2003, 27, 355-362.

- Boer, C.A.; Assis, R.L.; Silva, G.P.; Braz, A.J.B.P.; Barroso, A.L.L.; Cargnelutti Filho, A.; Pires, F.R. Ciclagem de nutrientes por plantas de cobertura na entressafra em um solo de Cerrado. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2007, 42, 1269-1276. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-204X2007000900008. [CrossRef]

- Peres, J.G.; Souza, C.F.; Lavorenti, N.A. Avaliação dos efeitos da cobertura de palha de cana de açúcar na umidade e na perda de água no solo. Eng. Agríc. 2010, 30, 875-886. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-69162010000500010. [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.; Silva, C.F.D.; Pereira, M.G.; Brito, R.J.D.; Benites, V.D.M. Avaliação dos compartimentos da matéria orgânica em área de Mata Atlântica. Acta Sci., Agron. 2011, 33, 545-550. https://doi.org/10.4025/actasciagron.v33i3.5169. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Pavinato, P.S.; Withers, P.J.A.; Teles, A.P.B.; Herrera, W.F.B. Legacy phosphorus and no tillage agriculture in tropical oxisols of the Brazilian savanna. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 542, 1050-1061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.08.118. [CrossRef]

- Spera, S.T.; Santos, H.P.; Fontaneli, R.S.; Toom, G.O. Atributos físicos de Hapludox em função de sistemas de produção integração lavoura-pecuária (ILP), sob plantio direto. Rev. Acta Sci., Agron. 2010, 32. https://doi.org/10.4025/actasciagron.v32i1.926. [CrossRef]

- Bonini, C.S.B.; Alves, M.C. Estabilidade de agregados de um Latossolo vermelho degradado em recuperação com adubos verdes, calcário e gesso. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo. 2011, 35, 1263-1270. http://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832011000400019. [CrossRef]

- Dalchiavon, F.C.; Dal Bem, E.A.; Souza M.F.P.; Ribeiro, R.; Alves, M.C.; Colodro, G. Atributos fsicos de um Latossolo Vermelho distrófco degradado em resposta à aplicação de biossólidos. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Agrár. 2013, 8, 205-210. htps://doi.org/10.5039/agraria.v8i2a2370.

- Zaninet, R.A.; Moreira, A.; Moraes, L.A.C. Atributos fsicos, químicos e biológicos de Latossolo Amarelo na conversão de floresta primária para seringais na Amazônia. Pesq. Agropecu. Bras. 2016, 51, 1061-1068. htps://doi.org/10.1590/s0100-204x201600090000.

- Calonego, J.C.; Rosolem, C.A. Soybean root growth and yield in rotaton with cover crops under chiseling and no-tll. Eur. J. Agron. 2010, 33, 242-249. htps://doi. org/10.1016/j.eja.2010.06.002.

| Manual planting together with corn | |

|---|---|

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 |

Brachiaria brizantha cv Piatã Brachiaria brizantha cv Marandú Urochloa mosambicensis – urochloa grass Cenchrus ciliares (L) – buffel grass Brachiaria decumbens Panicum maximum cv Massai |

| Planting between rows along with corn | |

| 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

Brachiaria decumbens Brachiaria Brizantha cv Paiaguás Brachiaria Brizantha cv Piatã Corn + Brachiaria + Stylosanthes Corn + Piatã + Stylosanthes Mombaça by hand |

| Planting between rows 14 days after corn | |

| 13 14 15 |

Brachiaria Brizantha cv Piatã Brachiaria Brizantha cv Paiaguás Brachiaria brizantha cv Marandú |

| Planting 14 days after sorghum grain | |

| 16 17 18 19 20 |

Panicum maximum cv Massai Urochloa mosambicensis Brachiaria Brizantha cv Piatã Brachiaria Brizantha cv Paiaguás Panicum maximum cv Mombaça |

| Planting 14 days after corn by hand | |

| 21 22 23 24 25 |

Panicum maximum cv Massai Urochloa mosambicensis – urochloa grass Brachiaria Brizantha cv Piatã Brachiaria Brizantha cv Paiaguás Panicum maximum cv Mombaça |

| Attributes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | P | K | Na+ | H+Al+3 | Al+3 | Ca+2 | Mg+2 | M.O |

| H2O | mg dm-3 | -------------------------cmolc dm-3--------------------- | g dm-3 | |||||

| 6.2 | 45.5 | 65.1 | 0.0 | 3.22 | 0.05 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 7.05 |

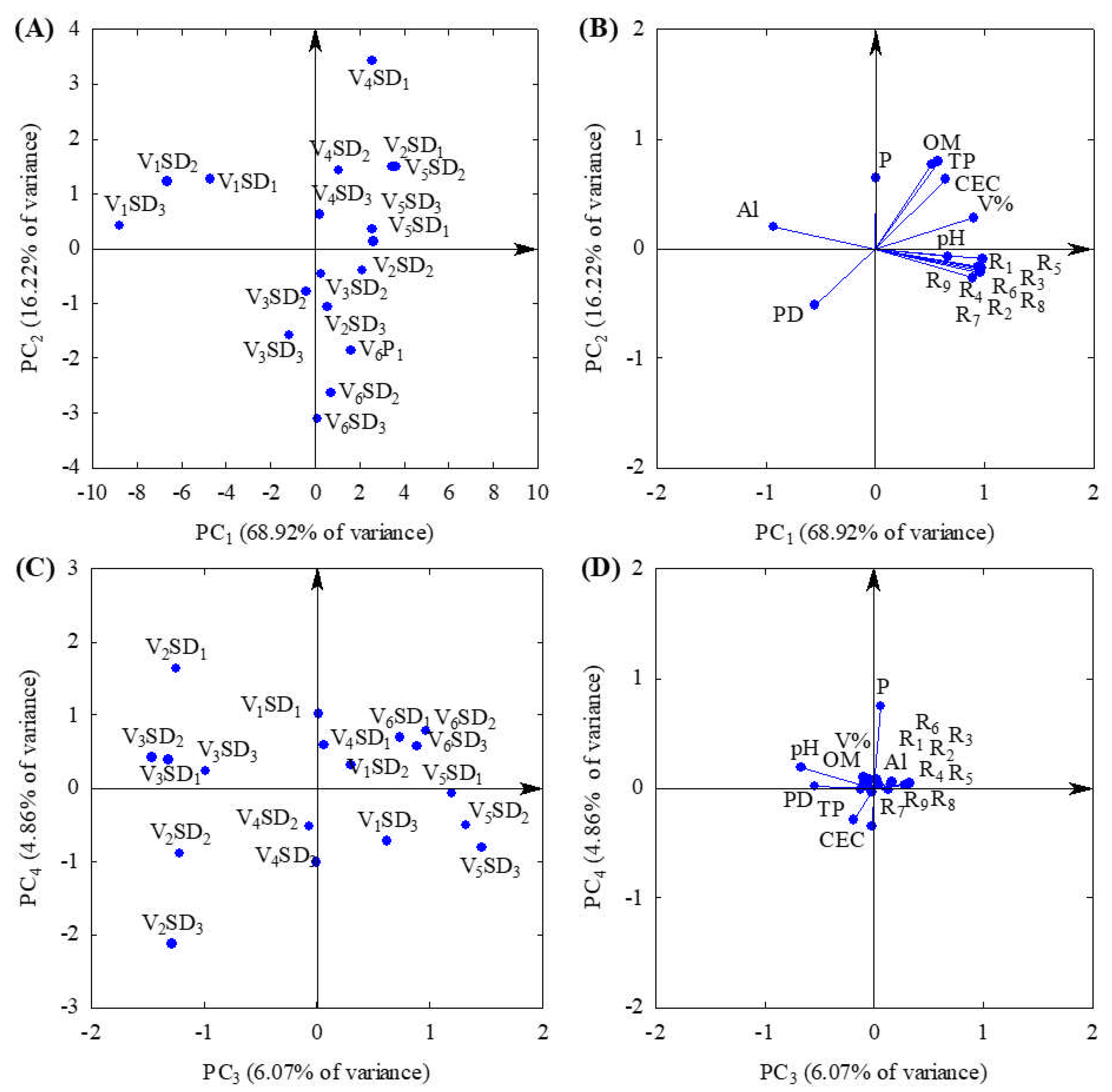

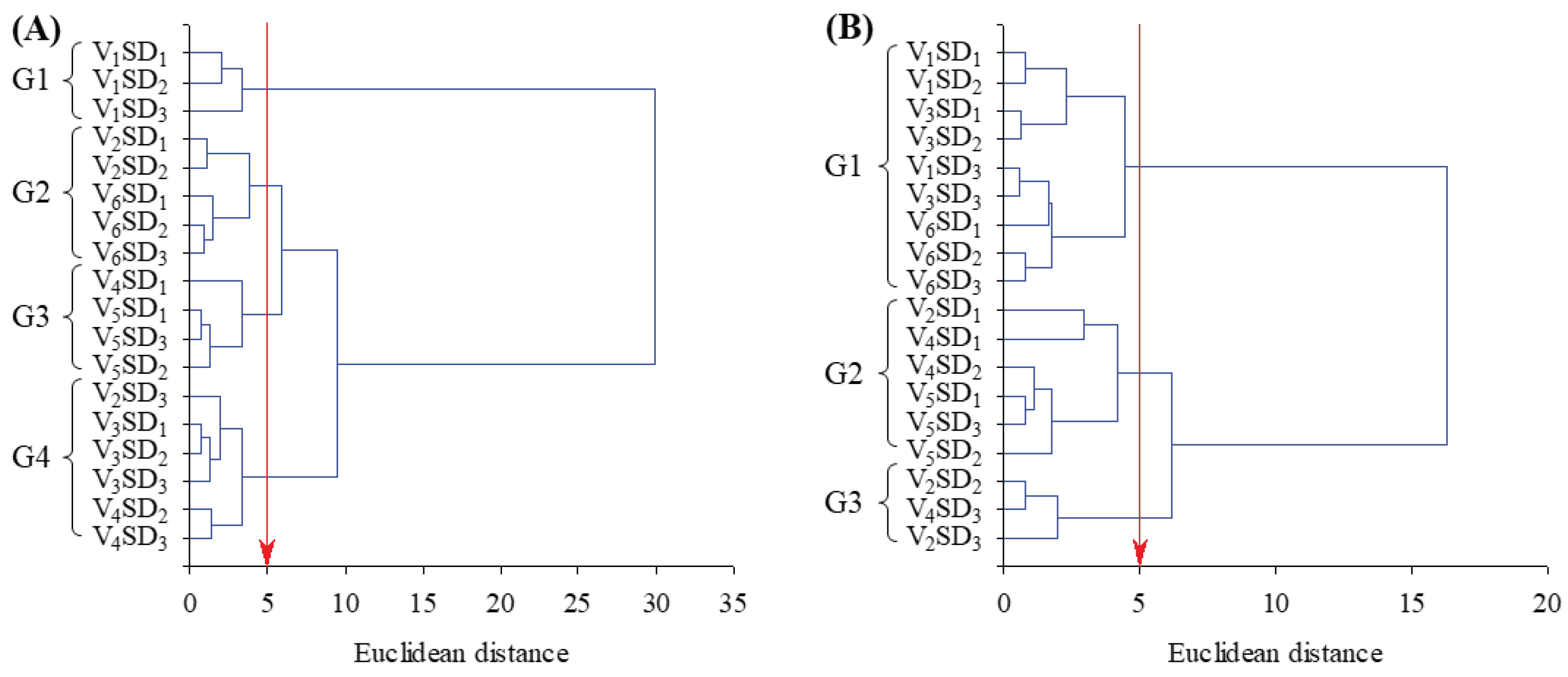

| Indicators | Principal components | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4** | |

| Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) | ||||

| R1 – Microbial respiration at 4 days | 0.98* | -0.09 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

| R2 – Microbial respiration at 8 days | 0.97* | -0.23 | -0.04 | 0.07 |

| R3 – Microbial respiration at 12 days | 0.96* | -0.17 | -0.05 | 0.02 |

| R4 – Microbial respiration at 16 days | 0.96* | -0.18 | -0.10 | 0.03 |

| R5 – Microbial respiration at 20 days | 0.97* | -0.17 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| R6 – Microbial respiration at 24 days | 0.90* | -0.26 | 0.33 | 0.04 |

| R7 – Microbial respiration at 28 days | 0.94* | -0.17 | 0.28 | 0.03 |

| R8 – Microbial respiration at 32 days | 0.97* | -0.20 | 0.13 | -0.01 |

| R9 – Microbial respiration at 36 days | 0.98* | -0.18 | -0.02 | -0.04 |

| pH - Hydrogen Potential | 0.67* | -0.08 | -0.66* | 0.18 |

| P - Phosphorus content in the soil | 0.00 | 0.64* | 0.07 | 0.75* |

| Al - Aluminum content | -0.93* | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.06 |

| OM - Organic matter content | 0.58* | 0.80* | -0.11 | -0.02 |

| CEC - Cation Exchange Capacity | 0.64 | 0.64* | -0.02 | -0.34 |

| V% - Base saturation | 0.91* | 0.28 | -0.09 | 0.09 |

| PD - Particle density | -0.55* | -0.52* | -0.54* | 0.01 |

| TP – Total porosity | 0.52 | 0.77* | -0.19 | -0.29 |

| λ – Eigenvalues | 11.72 | 2.76 | 1.03 | 0.83 |

| σ2 (%) Total explained variance | 68.92 | 16.22 | 6.07 | 4.86 |

| σ2 (%) Total accumulated variance | 68.92 | 85.14 | 91.22 | 96.07 |

| Variation sources | Wilks test (p-value) | F-test (p-value) | ||

| Var – Soil cover varieties | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| SD – Sampling Depth | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| Var x SD - Interaction between factors | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).